| Revision as of 01:24, 5 November 2008 editThingg (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users71,378 editsm Reverted edits by 218.214.18.108 to last version by Thingg (HG)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:30, 15 October 2024 edit undoMrOllie (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers236,663 editsm Reverted 1 edit by Bluegreydonkey (talk) to last revision by BelburyTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| (521 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Distance food is transported from production to consumption}} | |||

| '''Food miles''' is a term which refers to the distance ] is ]ed from the time of its production until it reaches the consumer. It is one dimension used in assessing the ] impact of food. The concept of food miles originated in 1990 in the United Kingdom. It was conceived by Andrea Paxton, who wrote a research paper that discussed the fact that food miles are the distance that food travels from the farm it is produced on to the kitchen in which it is being consumed (Iles, 2005, p.163). Engelhaupt (2008) states, that “food miles is the distance food travels from farm to plate, are a simple way to gauge food’s impact on climate change” (p. 3482). Food travels between 1, 500 to 2,500 miles every time that it is delivered to the consumer. The travel of products from the farms to the consumers is 25 percent farther now than it was in 1980 (“Counting our food miles,” 2007). Some scholars believe that the pollution is created due to the globalization of trade overseas; the focus of food supply bases into fewer, larger supplies; the drastic change in the delivery pattern; increase in processing and packaging foods; and making fewer trips to the supermarket. Others state that the GHG (Greenhouse Gas) emissions are created by the production phases which create 83 percent, 8.1 tons of CO2 foot printing or food miles. (Engelhaupt, E., 2008). The goal of the Environmental Protection Agencies is to make people aware of the environment impacts of food miles and show the pollution percentage and the energy used to transport food over long distances, at this time there are researches that are working to provide the public with more information. | |||

| {{Use American English|date=May 2017}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=March 2017}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Green economics sidebar}} | |||

| '''Food miles''' is the distance ] is ]ed from the time of its making until it reaches the ]. Food miles are one factor used when testing the ] impact of food, such as the ] of the food.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Engelhaupt | first1 = E | year = 2008 | title = Do food miles matter? | journal = Environmental Science & Technology | volume = 42 | issue = 10| page = 3482 | doi=10.1021/es087190e| pmid = 18546672 | bibcode = 2008EnST...42.3482E | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| The concept of food miles is part of a broader issue of ] which deals with a large range of environmental issues, including ]. The term was coined by Tim Lang (now Professor of Food Policy, ]) who says: "The point was to highlight the hidden ecological, social and economic consequences of food production to consumers in a simple way, one which had objective reality but also connotations." <ref> Tim Lang (2006). ‘locale / global (food miles)’, Slow Food (Bra, Cuneo Italy), 19, May 2006, p.94-97 </ref> | |||

| The concept of food miles originated in the early 1990s in the United Kingdom. It was conceived by Professor ]<ref>http://www.city.ac.uk/communityandhealth/phpcfp/foodpolicy/index.html. He explains its history in this article Tim Lang (2006). 'locale / global (food miles)', Slow Food (Bra, Cuneo Italy), 19, May 2006, pp. 94–97</ref> at the Sustainable Agriculture Food and Environment (SAFE) Alliance<ref>The SAFE Alliance merged with the National Food Alliance in 1999 to become Sustain: the alliance for better food and farming http://www.sustainweb.org/. Professor Tim Lang chaired Sustain from 1999 to 2005.</ref> and first appeared in print in a report, "The Food Miles Report: The Dangers of Long-Distance Food Transport", researched and written by ].<ref name="Paxton">Paxton, A (1994). "The Food Miles Report: The Dangers of Long-Distance Food Transport". SAFE Alliance, London, UK. https://www.sustainweb.org/publications/the_food_miles_report/</ref><ref>Iles, A. (2005). "Learning in sustainable agriculture: Food miles and missing objects". Environmental Values, 14, 163–83</ref> | |||

| A ] report in 2005 undertaken by researchers at ] Environment, entitled ''The Validity of Food Miles as an Indicator of Sustainable Development'', included findings that "the direct environmental, social and economic costs of food transport are over £9 billion each year, and are dominated by congestion." | |||

| Some scholars believe that an increase in the distance food travels is due to the ] of trade; the focus of food supply bases into fewer, larger districts; drastic changes in delivery patterns; the increase in processed and packaged foods; and making fewer trips to the supermarket. These make a small part of the ] created by food; 83% of overall emissions of CO<sub>2</sub> are in production phases.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Weber | first1 = C. | last2 = Matthews | first2 = H. | year = 2008 | title = Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States | journal = Environmental Science & Technology | volume = 42 | issue = 10| pages = 3508–3513 | doi=10.1021/es702969f| pmid = 18546681 | bibcode = 2008EnST...42.3508W | doi-access = }}</ref> | |||

| Recent findings indicate that it is not only how far the food has traveled but the method of travel that is important to consider. The positive environmental effects of specialist ] may be offset by increased ]ation, unless it is produced by local ]s. But even then the logistics and effects on other local traffic may play a big role.{{fact|date=May 2008}} Also, many trips by personal cars to shopping centers would have a negative environmental impact compared to a few truck loads to neighborhood stores that can be easily accessed by ] or ]. | |||

| Several studies compare emissions over the ], including production, consumption, and transport.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.worldwatch.org/ww/localfood|title=Sources and Resources for 'Local Food: The Economics' |publisher=Worldwatch Institute |access-date=April 28, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190404015748/http://www.worldwatch.org/ww/localfood|archive-date=April 4, 2019}}</ref> These include estimates of food-related emissions of ] 'up to the farm gate' versus 'beyond the farm gate'. In the UK, for example, agricultural-related emissions may account for approximately 40% of the overall ] (including retail, packaging, fertilizer manufacture, and other factors), whereas greenhouse gases emitted in transport account for around 12% of overall food-chain emissions.<ref>Garnett 2011, Food Policy</ref> | |||

| A 2022 study suggests global food miles {{CO2}} emissions are 3.5–7.5 times ], with transport accounting for about 19% of total food-system emissions,<ref>{{cite news |title=Climate impact of food miles three times greater than previously believed, study finds |url=https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jun/21/climate-impact-of-food-miles-three-times-greater-than-previously-believed-study-finds |access-date=13 July 2022 |work=The Guardian |date=20 June 2022 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Li |first1=Mengyu |last2=Jia |first2=Nanfei |last3=Lenzen |first3=Manfred |last4=Malik |first4=Arunima |last5=Wei |first5=Liyuan |last6=Jin |first6=Yutong |last7=Raubenheimer |first7=David |title=Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions |journal=Nature Food |date=June 2022 |volume=3 |issue=6 |pages=445–453 |doi=10.1038/s43016-022-00531-w |pmid=37118044 |s2cid=249916086 |language=en |issn=2662-1355}}</ref> albeit shifting towards plant-based diets remains substantially more important.<ref>{{cite news |title=How much do food miles matter and should you buy local produce? |url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/2325164-how-much-do-food-miles-matter-and-should-you-buy-local-produce/ |access-date=13 July 2022 |work=New Scientist}}</ref> | |||

| The concept of "food miles" has been criticised, and food miles are not always correlated with the actual environmental impact of food production. In comparison, the percentage of total energy used in home food preparation is 26% and in food processing is 29%, far greater than transportation.<ref>John Hendrickson, "Energy use in the U.S. Food System: A summary of existing research and analysis." Sustainable Farming (Ste. Anne de Bellevue, Quebec), vol. 7, no. 4. Fall 1997.</ref> | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| The concept of food miles is part of the broader issue of ] which deals with a large range of environmental, social and economic issues, including ]. The term was coined by Tim Lang (now Professor of Food Policy, ]) who says: "The point was to highlight the hidden ecological, social and economic consequences of food production to consumers in a simple way, one which had objective reality but also connotations."<ref>Tim Lang (2006). 'locale / global (food miles)', Slow Food (Bra, Cuneo Italy), 19, May 2006, p.94-97</ref> The increased distance traveled by food in developed countries was caused by the globilization of food trade, which increased by four times since 1961.<ref>Erik Millstone and Tim Lang, The Atlas of Food, Earthscan, London, 1963, p. 60.</ref> Food that is transported by road produces more carbon emissions than any other form of transported food. Road transport produces 60% of the world's food transport carbon emissions. Air transport produces 20% of the world's food transport carbon emissions. Rail and sea transport produce 10% each of the world's food transport carbon emissions. | |||

| Although it was never intended as a complete measure of environmental impact, it has come under attack as an ineffective means of finding the true environmental impact. For example, a ] report in 2005 undertaken by researchers at ] Environment, entitled ''The Validity of Food Miles as an Indicator of Sustainable Development'', included findings that "the direct environmental, social and economic costs of food transport are over £9 billion each year, and are dominated by congestion."<ref>Smith, A. et al. (2005) The Validity of Food Miles as an Indicator of Sustainable Development: Final report. DEFRA, London. See https://statistics.defra.gov.uk/esg/reports/foodmiles/default.asp {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080527094731/http://statistics.defra.gov.uk/esg/reports/foodmiles/default.asp |date=May 27, 2008 }}</ref> The report also indicates that it is not only how far the food has travelled but the method of travel in all parts of the food chain that is important to consider. Many trips by personal cars to shopping centres would have a negative environmental impact compared to transporting a few truckloads to neighbourhood stores that can be easily reached by walking or cycling. More emissions are created by the drive to the supermarket to buy air freighted food than was created by the air freighting in the first place.<ref name="motu.org.nz">{{Cite web |url=http://www.motu.org.nz/files/docs/agdpresentations/AgD23_Saunders_-_Carbon_footprinting_and_other_trade_factors.pdf |title=Archived copy |access-date=March 3, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130207005907/http://motu.org.nz/files/docs/agdpresentations/AgD23_Saunders_-_Carbon_footprinting_and_other_trade_factors.pdf |archive-date=February 7, 2013 }}</ref> Also, the positive environmental effects of ] may be compromised by increased ]ation, unless it is produced by local ]s. The ] notes that to understand the carbon emissions from food production, all the carbon-emitting processes that occur as a result of getting food from the field to our plates need to be considered, including production, origin, seasonality and home care.<ref>, '']'', 15 March 2012. Retrieved on 20 January 2015.</ref> | |||

| ==Food miles in business== | ==Food miles in business== | ||

| A recent study led by Professor Miguel Gomez (Applied Economics and Management), at ] and supported by the ] found that in many instances, the supermarket supply chain did much better in terms of food miles and fuel consumption for each pound compared to farmers markets. It suggests that selling local foods through supermarkets may be more economically viable and sustainable than through farmers markets.<ref>{{cite news|last=Prevor|first=Jim|title=Jim Prevor's Perishable Pundit|url=http://www.perishablepundit.com/index.php?date=10/01/10&pundit=1|access-date=20 July 2011|date=1 October 2010}}</ref> | |||

| Business leaders have adopted food miles as a model for understanding inefficiency in a ] chain. ], famously focused on efficiency, was an early adopter of food miles as a profit-maximizing strategy. More recently, Wal-Mart has embraced the environmental benefits of ] efficiency as well. In 2006, Wal-Mart, ], ] said, "The benefits of the strategy are undeniable, whether you look through the lens of ] reduction or the lens of cost savings. What has become so obvious is that 'a green strategy' provides better value for our customers".<ref name ="Al Gore"></ref> Wal-Mart has since made a series of environmental commitments that suggest the company is looking more holistically at supply chain sustainability, such as restricting ] suppliers to ] independently certified as sustainable, a practice that may increase food miles.<ref name ="Al Gore" /> Still it is undeniable that Wal-Mart's strategy of using supply chains from as far away as ] exorbitantly increases greenhouse emissions. They are often criticized for "]" and only adopting large-scale green tactics, which make them appear earth-friendly but actually have little positive environmental impact.{{fact|date=May 2008}} | |||

| ==Calculating food miles== | |||

| Some other alternatives for reducing food miles are to create Co-op grocery stores. A Co-op is a small business strictly owned and managed by its members. The way that this works is that people come together, they create equity and then they purchase their products. They grow organic food and their food miles are drastically reduced. “Choosing to buy organic has value, the hidden costs of shopping increase substantially when road miles are factored in”(Holt and Watson, 2008, p. 321). The first co-op was created in 1844 in England with twenty-eight people. They started out by selling just sugar, flour, butter and oatmeal. Today there are over 47,000 coop corporations in the United States alone. Not only are Co-op markets reducing the food miles, but they are also providing the consumers with healthy food, organic food. The facts and figures for 2005 state that organic foods contains higher levels of vitamin C, calcium, magnesium, iron, phosphorous and chromium; and 15 percent lower levels of nitrates (Siner, 1996). | |||

| With processed foods that are made of many different ingredients, it is very complicated, though not impossible, to calculate the {{CO2}} emissions from transport by multiplying the distance travelled of each ingredient, by the carbon intensity of the mode of transport (air, road or rail). However, as both Tim Lang and the original Food Miles report noted, the resulting number, although interesting, cannot give the whole picture of how sustainable – or not – a food product is.<ref name="Paxton"/> | |||

| ==Food mile calculation problems== | |||

| {{Unreferencedsection|date=January 2008}} | |||

| The calculation of food miles ignores questions of scale. Consider the following simplistic example: a small family farm produces 10 tons of produce, but has a small truck with capacity for only 1 ton. If the farm is located {{convert|100|mi|km}} away from market, each piece of produce only travels 100 "food miles"; however, 10 trips are required to bring that produce to market. Now consider a farm located {{convert|1000|mi|km}} away but with a 10-ton truck. That farm's produce would travel 1000 "food miles" while consuming a slightly higher amount of ] (as a bigger truck needs less fuel per unit of mass transported).{{fact|date=May 2008}}. | |||

| Wal-Mart publicized a press releasing that stated food travelled {{convert|1,500|miles|km}} before it reaches customers. The statistics aroused public concern about food miles. According to Jane Black, a food writer who covers food politics, the number was derived from a small database. The 22 terminal markets from which the data was collected handled 30% of the United States produce.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Black |first1=Jane |title=How the press got the idea that food travels 1500 miles from farm to plate. |url=https://slate.com/human-interest/2008/09/how-the-press-got-the-idea-that-food-travels-1500-miles-from-farm-to-plate.html |website=Slate Magazine |access-date=October 26, 2021 |date=September 17, 2008}}</ref> | |||

| Furthermore, the mode of transportation is not included. Ships are much more effective than trucks, cars or planes. However there is still a debate on whether it is more environmentally friendly to use trucks or planes for long distance shipping. Some experts believe that when sending food from California to New York, the best way to ship that food is via airplanes(Waye, 2008, p.281). Others believe that trucks give off only 30% of the carbon emissions that planes do(Edward-Jones, 2008, p.267). Therefore there is a need when reporting food miles to standardize by some quantity measure. Frozen and fresh food use much more energy to transport. Red meat has an average total distance of 20, 400 km, which includes the grain used to feed the cows, with a shipping distance of around 1,800 km, which is only about 9% of the total distance. Beverages are the product with the least average shipping distance with around 330 km, but including all production there is around 1,200 km of shipments to make the beverage. Of the total distance for fruits and vegetables, 50% of the distance is shipping(Weber, 2008, p.3511). Packaging and preparation can also add/remove weight to the food transported, so the same quantity of food can require different quantities of energy depending on where the packaging and preparation done. For example, orange juice is often transported in concentrated form, and only diluted and put in bottles near the customers. A more relevant indicator would be the "average number of food miles per ton" or per other unit of measure for a certain shipment. A better all round indicator, which would address some of the problems below, also, would be a measure of total embodied energy per ton. | |||

| Some iOS and Android apps allow consumers to get information about food products, including nutritional information, product origin, and the distance the product travelled from its production location to the consumer. Such apps include OpenLabel, Glow, and ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.smh.com.au/technology/mobile-barcode-scanning-apps-empower-consumers-to-shop-with-confidence-20150319-1m2mjz.html|title=Mobile barcode scanning apps empower consumers to shop with confidence|first=Esther|last=Han|date=March 20, 2015|website=The Sydney Morning Herald}}</ref> These apps may rely on ] scanning.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.foodbev.com/news/interview-origintrail-the-app-that-tells-you-where-your-food-is-from/|title=Interview: OriginTrail, an app that tells you where your food is from|date=March 9, 2016}}</ref> Also, smartphones can scan a product's ], after which the browser opens up showing the production location of the product (i.e. Farm to Fork project, ...).<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/consumers-track-products-smartphone|title=How consumers can track products at the touch of a smartphone button|first=Mira|last=Trebar|date=April 15, 2014|website=the Guardian}}</ref> | |||

| One way to be able to track food miles would be by the creation of food labels. Countries such as Sweden, the U.K. and Canada are creating their own labels that are making people more aware of food miles. Sweden’s labels are called “climate friendly” and with the use of these labels “Sweden will be able to choose food according to the impact its production and transportation methods have on the climate (“Counting our food miles,” 2007, p. 33). The United Kingdom uses “carbon labels” created by Tesco. In Canada they are not only creating food labels, but also developing a system in which they can track farmers and processors and then link them to the purchasers. They tasted their carbon labels on products such as Walkers crisp and Cadburys chocolates. What they did was create labels that had small C’s with a downward arrow that showed the grams of carbon dioxide created for the production (McKei, 2008). McKie (2008) results showed that “packets of Walker's Ready Salted and Salt and Vinegar crisps each generate 75g of carbon, while the cheese and onion variety produced only 74g” (para. 19). As one can see, it is easier to calculate the carbon dioxide for a product with fewer toppings, then one such as a pizza or spaghetti. Due to the large numbers the scientists are trying to reduce food miles. | |||

| ==Criticism== | |||

| ==A non-holistic approach== | |||

| Critics of food miles point out that transport is only one component of the total environmental impact of food production and consumption. In fact, any environmental assessment of food that consumers buy needs to take into account how the food has been produced and what energy is used in its production. A recent DEFRA case study indicated that ]es grown in ] and transported to the ] may have a lower carbon footprint in terms of ] than tomatoes grown in heated ]s the United Kingdom.<Ref> </ref> | |||

| === Fair trade === | |||

| A 2006 research report from ] counters claims about food miles by comparing total energy used in ] in ] and ], taking into account energy used to ship the food to Europe for consumers.<ref> </ref><ref> </ref> The report states, "New Zealand has greater production efficiency in many food commodities compared to the UK. For example New Zealand ] tends to apply fewer ]s (which require large amounts of energy to produce and cause significant ]) and animals are able to ] year round outside eating grass instead of large quantities of brought-in ] such as ]s. In the case of ] and sheep meat production NZ is by far more ], even including the transport cost, than the UK, twice as efficient in the case of dairy, and four times as efficient in case of ]. In the case of ] NZ is more energy efficient even though the energy embodied in capital items and other inputs data was not available for the UK." | |||

| According to Oxfam researchers, there are many other aspects of the agricultural processing and the food ] that also contribute to ] which are not taken into account by simple "food miles" measurements.<ref name="ChiMacGregorKing">Chi, Kelly Rae, James MacGregor and Richard King (2009). . ]/].</ref><ref>Chi, 2009, p. 9.</ref> There are benefits to be gained by improving livelihoods in poor countries through agricultural development. ] farmers in poor countries can often improve their income and standard of living if they can sell to distant export markets for higher value horticultural produce, moving away from the subsistence agriculture of producing staple crops for their own consumption or local markets.<ref>MacGregor, J.; Vorley, B (2006) Fair Miles? Weighing environmental and social impacts of fresh produce exports from Sub-Saharan Africa to the UK. Fresh Insights no.9. International Institute for Environment and Development/ Natural Resources Institute, London, UK, 18 pp. http://www.dfid.gov.uk/r4d/SearchResearchDatabase.asp?OutPutId=173492</ref> | |||

| Further study on the total ] of food is required, of which transport may or may not make a large contribution. However, "Food Miles" signals more than just carbon footprint - which came into being several years later, and also includes transport of ], life cycle assessments, land use and the inefficiencies of moving similar foods backwards and forwards over the same ground. | |||

| However, exports from poor countries do not always benefit poor people. Unless the product has a ] label, or a label from another robust and independent scheme, food exports might make a bad situation worse. Only a very small percentage of what importers pay will end up in the hands of plantation workers.<ref>C. Dolan, J. Humphrey, and C. Harris-Pascal, "Value Chains and Upgrading: The Impact of U.K. Retailers on the Fresh Fruit and Vegetables Industry in Africa," Institute of Development Studies Working Paper 96, University of Sussex, 1988.</ref> Wages are often very low and working conditions bad and sometimes dangerous. Sometimes the food grown for export takes up land that had been used to grow food for local consumption, so local people can go hungry.<ref>Action Aid is one of many organisations drawing attention to this problem and campaigning to improve this situation - http://www.actionaid.org.uk</ref> | |||

| A commonly ignored element is the local loop. The act of driving further to a more "right-on" food source increases the total carbon footprint. A shopper may buy say 5 kg of meat and use about a gallon to get it. That piece of meat could have gone over {{convert|60000|mi|km}} by road (40tonner at 8mpg) to require the same carbon in transportation. However, this is an extreme scenario, in which a consumer burns a gallon of gasoline (30 or {{convert|40|mi|km}} of travel) to buy a single food item, 5 kg of meat. While extreme consumer behaviors can certainly cancel any environmental benefit arising from any food-buying choice, it is a different question whether consumer behaviors do so ''in practice''. | |||

| === Energy used in production as well as transport === | |||

| After analyzing food miles the scholars have concluded that food miles are negative in general. People should strive to reduce the production of food miles by ether buying products locally such as buying products in Coop markets or eating less red meat, chicken and dietary products. There is no simple answer for that question of “How to stop Greenhouse gasses?” The scholar’s state that “in the U.S. and Europe policy-makers and activist have recognized that environmental education may change the behavior of people as consumers, politically active citizens and producers” (Iles, 2005, p. 164). The only thing that one can do is share their knowledge about food miles and to educate people. So the next time when one goes to the supermarket and buys their groceries they should think about how many miles there food has traveled. | |||

| Researchers say a more complete environmental assessment of food that consumers buy needs to take into account how the food has been produced and what ] is used in its production. A recent ] (DEFRA) case study indicated that ]es grown in ] and transported to the ] may have a lower carbon footprint in terms of ] than heated ]s in the United Kingdom.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://randd.defra.gov.uk/Default.aspx?Menu=Menu&Module=More&Location=None&Completed=0&ProjectID=15001|title=Defra, UK - Science Search|first=Food and Rural Affairs (Defra)|last=Department for Environment|website=defra.gov.uk}}</ref> | |||

| According to German researchers, the food miles concept misleads consumers because the size of transportation and production units is not taken into account. Using the methodology of ] in accordance with ], entire supply chains providing German consumers with food were investigated, comparing local food with food of European and global provenance. Large-scale agriculture reduces unit costs associated with food production and transportation, leading to increased efficiency and decreased energy use per kilogram of food by ]. Research from the ] show that small food production operations may cause even more environmental impact than bigger operations in terms of ] per kilogram, even though food miles are lower. Case studies of lamb, beef, wine, apples, fruit juices and pork show that the concept of food miles is too simple to account for all factors of food production.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.uni-giessen.de/fbr09/pt/PT_Ecology_of_Scale.htm |title=PT_Ecology of Scale |website=www.uni-giessen.de |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091206031646/http://www.uni-giessen.de/fbr09/pt/PT_Ecology_of_Scale.htm |archive-date=2009-12-06}} </ref><ref>Schlich E, Fleissner U: The Ecology of Scale. Assessment of Regional Energy Turnover and Comparison with Global Food. Int J LCA 10 (3) 219-223:2005.</ref><ref>Schlich E: Energy Economics and the Ecology of Scale in the Food Business. In: Caldwell PG and Taylor EV (editors): New Research on Energy Economics. ] Hauppauge NY:2008.</ref> | |||

| A 2006 research report from the ] and Economics Research Unit at ] counters claims about food miles by comparing total energy used in ] in ] and ], taking into account energy used to ship the food to Europe for consumers.<ref>Saunders, C; Barber, A; Taylor, G, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100522140026/http://www.lincoln.ac.nz/Documents/2328_RR285_s13389.pdf |date=May 22, 2010 }} (2006). Research Report No. 285. Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit, ], Christchurch, New Zealand.</ref><ref name=McWilliams>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/06/opinion/06mcwilliams.html?_r=1&oref=login&oref=slogin |title=Food that travels well |first=James E. |last=McWilliams |newspaper=] |date=2007-08-06}}</ref> The report states, "New Zealand has greater production efficiency in many food commodities compared to the UK. For example New Zealand ] tends to apply fewer ]s (which require large amounts of energy to produce and cause significant ]) and animals are able to ] year round outside eating grass instead of large quantities of brought-in ] such as ]s. In the case of ] and ] production NZ is by far more ], even including the transport cost, than the UK, twice as efficient in the case of dairy, and four times as efficient in case of sheep meat.<ref name="motu.org.nz"/> In the case of ]s, NZ is more energy-efficient even though the energy embodied in capital items and other inputs data was not available for the UK." | |||

| Other researchers have contested the claims from New Zealand. Professor Gareth Edwards-Jones has said that the arguments "in favour of New Zealand apples shipped to the UK is probably true only or about two months a year, during July and August, when the carbon footprint for locally grown fruit doubles because it comes out of cool stores."<ref>'Food miles' minor element of carbon footprint, http://www.freshplaza.com/news_detail.asp?id=40471. See also a range of publications by Professor Edwards-Jones and a team of researchers at Bangor University, http://www.bangor.ac.uk/senrgy/staff/edwards.php.en {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110903105524/http://www.bangor.ac.uk/senrgy/staff/edwards.php.en |date=September 3, 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| Studies by Dr. Christopher Weber et al. of the total ] of food production in the U.S. have shown transportation to be of minor importance, compared to the carbon emissions resulting from pesticide and fertilizer production, and the fuel required by farm and food processing equipment.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1021/es702969f | volume=42 | issue=10 | title=Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States | year=2008 | journal=Environmental Science | pages=3508–3513 | last1 = Weber | first1 = Christopher L.| pmid=18546681 | bibcode=2008EnST...42.3508W | doi-access= }}</ref> | |||

| === Livestock production as a source of greenhouse gases === | |||

| Farm animals account for between 20% and 30% of global ].<ref>To see details of the United Nations research into meat and the environment, visit: http://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/news/2006/1000448/index.html {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080328062709/http://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/news/2006/1000448/index.html |date=March 28, 2008 }}. See also Steinfeld, H et al. (2006) Livestock's long shadow: Environmental issues and options. ], Rome. {{cite web |url=http://www.virtualcentre.org/en/library/key_pub/longshad/A0701E00.htm |title=全讯网 论坛,粉,紫水晶手链,全讯网 论坛专题内容 |access-date=2011-10-11 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140806144540/http://www.virtualcentre.org/en/library/key_pub/longshad/A0701E00.htm |archive-date=2014-08-06 }}</ref><ref>Garnett, T (2007) Meat and dairy production and consumption. Exploring the livestock sector's contribution to the ] and assessing what less greenhouse gas intensive systems of production | |||

| and consumption might look like Working paper produced a part of the work of the Food Climate Research Network, Centre for Environmental Strategy, ] https://www.fcrn.org.uk/sites/default/files/TGlivestock_env_sci_pol_paper.pdf</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://skepticalscience.com/how-much-meat-contribute-to-gw.html|title=How much does animal agriculture and eating meat contribute to global warming?|website=Skeptical Science}}</ref> That figure includes the clearing of land to feed and graze the animals. Clearing land of trees, and cultivation, are the main drivers of farming emissions. ] eliminates ], accelerating the process of ]. Cultivation, including the use of ]s, releases greenhouse gases such as ]. ] is especially demanding of ], as producing a tonne of it takes 1.5 tonnes of oil.<ref name="ChiMacGregorKing"/> | |||

| Meanwhile, it is increasingly recognised that ] and ] are the largest sources of food-related emissions. The UK's consumption of meat and dairy products (including imports) accounts for about 8% of national greenhouse gas emissions related to consumption.<ref name="ChiMacGregorKing"/> | |||

| According to a study by engineers Christopher Weber and H. Scott Matthews of ], of all the greenhouse gases emitted by the food industry, only 4% comes from transporting the food from producers to retailers. The study also concluded that adopting a ], even if the vegetarian food is transported over very long distances, does far more to reduce greenhouse gas emissions than does eating a locally grown diet.<ref>, Jane Liaw, special to ], June 2, 2008</ref> They also concluded that "Shifting less than one day per week's worth of calories from ] and dairy products to chicken, fish, eggs, or a vegetable-based diet achieves more GHG reduction than buying all locally sourced food." In other words, the amount of red meat consumption is much more important than food miles. | |||

| === "Local" food miles === | |||

| A commonly ignored element is the ]. For example, a gallon of gasoline could transport 5 kg of meat over {{convert|60000|mi|km}} by road (40 tonner at 8 mpg) in ], or it could transport a single consumer only 30 or {{convert|40|mi|km}} to buy that meat. Thus foods from a distant farm that are transported in bulk to a nearby store consumer can have a lower footprint than foods a consumer picks up directly from a farm that is within driving distance but farther away than the store. This can mean that doorstep deliveries of food by companies can lead to lower carbon emissions or energy use than normal shopping practices.<ref>Coley, D. A., Howard, M. and Winter, M., 2009. Local food, food miles and carbon emissions: A comparison of farm shop and mass distribution approaches. Food Policy, 34 (2), pp. 150-155.</ref> Relative distances and mode of transportation make this calculation complicated. For example, consumers can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of the last mile by walking, bicycling, or taking public transport. Another impact is that goods being transported by large ships very long distances can have lower associated carbon emissions or energy use than the same goods traveling by truck a much shorter distance.<ref>Coley, D. A., Howard, M. and Winter, M., 2011. Food miles: time for a re-think? British Food Journal, 113 (7), pp. 919-934.</ref> | |||

| === Lifecycle analysis, rather than food miles === | |||

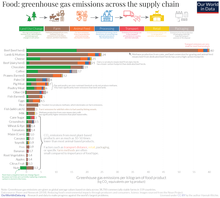

| ] | |||

| ], a technique that meshes together a wide range of different environmental criteria including emissions and waste, is a more holistic way of assessing the real environmental impact of the food we eat. The technique accounts for energy input and output involved in the production, processing, packaging and transport of food. It also factors in ], ] and ] and waste generation/].<ref>Chi, Kelly Rae, James MacGregor and Richard King (2009). Fair Miles: Recharting the food miles map. IIED/Oxfam. http://www.iied.org/pubs/display.php?o=15516IIED – p16</ref> | |||

| A number of organisations are developing ways of calculating the carbon cost or lifecycle impact of food and agriculture.<ref>Examples include http://www.carbontrustcertification.com/ and www.cffcarboncalculator.org.uk and https://carboncloud.com/</ref> Some are more robust than others but, at the moment, there is no easy way to tell which ones are thorough, independent and reliable, and which ones are just ]. | |||

| Even a full lifecycle analysis accounts only for the environmental effects of food production and consumption. However, it is one of the widely agreed three pillars of sustainable development, namely environmental, social and economic.<ref>World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future, (1987). Oxford University Press. Often known as the Brundtland report, after the Chair of the Commission, Gro Harlem Brundtland.</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| <references/> | <references/> | ||

| * Edwards-Jones, G., Milà i Canals, L., Hounsome, N., Truninger, M., Koerber, G., Hounsome, B., et al. (2008). Testing the assertion that ‘local food is best’: the challenges of an evidence-based approach. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 19(5), 265-274. | |||

| * Waye, V. (2008). Carbon Footprints, Food Miles and the Austrailian Wine Industry. Melbourne Journal of International Law, 9, 271-300. | |||

| * Weber, C., & Matthews, H. (2008). Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology, 42(10), 3508-3513. | |||

| * Iles, A. (2005). Learning in sustainable agriculture: Food miles and missing objects. Environmental Values, 14, 163-83. | |||

| * Engelhaupt, E. (2008). Do food miles matter? Environmental Science & Technology, 42, 3482. | |||

| * McKei, R. (2008). How the myth of food miles hurts the planet. Retrieved March 23, 2008, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/mar/23/food.ethicalliving | |||

| * Holt, D., & Watson, A. (2008). Exploring the dilemma of local sourcing versus international development –the case of the Flower Industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 17, 318-329. | |||

| * Pierre Desrochers & Hiroko Shimizu. "Yes We Have No Bananas: A Critique of the Food Mile Perspective." Mercatus Policy Series, Policy Primer No. 8, October 2008. http://mercatus.org/PublicationDetails.aspx?id=24612 | |||

| == |

===Sources=== | ||

| {{cleanup-references|date=March 2024}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * {{cite journal | last1 = Edwards-Jones | first1 = G. | last2 = Milà | last3 = Canals | first3 = L. | last4 = Hounsome | first4 = N. | last5 = Truninger | first5 = M. | last6 = Koerber | first6 = G. | last7 = Hounsome | first7 = B. | display-authors = etal | year = 2008 | title = Testing the assertion that 'local food is best': the challenges of an evidence-based approach | journal = Trends in Food Science & Technology | volume = 19 | issue = 5| pages = 265–274 | doi=10.1016/j.tifs.2008.01.008}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * {{cite journal | last1 = Waye | first1 = V | year = 2008 | title = Carbon Footprints, Food Miles and the Australian Wine Industry | journal = Melbourne Journal of International Law | volume = 9 | pages = 271–300 }} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * {{cite journal | last1 = Weber | first1 = C. | last2 = Matthews | first2 = H. | year = 2008 | title = Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States | journal = Environmental Science & Technology | volume = 42 | issue = 10| pages = 3508–3513 | doi=10.1021/es702969f| pmid = 18546681 | bibcode = 2008EnST...42.3508W | doi-access = }} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * {{cite journal | last1 = Iles | first1 = A | year = 2005 | title = Learning in sustainable agriculture: Food miles and missing objects | journal = Environmental Values | volume = 14 | issue = 2| pages = 163–183 | doi=10.3197/0963271054084894}} | |||

| * {{cite journal | last1 = Engelhaupt | first1 = E | year = 2008 | title = Do food miles matter? | journal = Environmental Science & Technology | volume = 42 | issue = 10| page = 3482 | doi=10.1021/es087190e| pmid = 18546672 | bibcode = 2008EnST...42.3482E | doi-access = free }} | |||

| * McKie, R. (2008). . Retrieved March 23, 2008. | |||

| * {{cite journal | last1 = Holt | first1 = D. | last2 = Watson | first2 = A. | year = 2008 | title = Exploring the dilemma of local sourcing versus international development –the case of the Flower Industry | url = http://repository.essex.ac.uk/11133/1/Flowermiles_opaacv.pdf| journal = Business Strategy and the Environment | volume = 17 | issue = 5| pages = 318–329 | doi=10.1002/bse.623}} | |||

| * Hogan, Lindsay and Sally Thorpe (2009). . ABARE (Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics) | |||

| * Chi, Kelly Rae, James MacGregor and Richard King (2009). . IIED/Oxfam. | |||

| * {{cite journal | last1 = Blanke | first1 = M. | last2 = Burdick | first2 = B. | year = 2005 | title = Food (miles) for thought: energy balance for locally-grown versus imported apple fruit | journal = Environmental Science and Pollution Research | volume = 12 | issue = 3| pages = 125–127 | doi=10.1065/espr2005.05.252| pmid = 15986993 | bibcode = 2005ESPR...12..125B | s2cid = 33467271 }} | |||

| * Borot, A., J. MacGregor and A. Graffham(eds) (2008). Standard Bearers: Horticultural exports and private standards in Africa. IIED, London. | |||

| * DEFRA (2009) . DEFRA, London. | |||

| * ECA (2009) Shaping Climate-Resilient Development: A framework for decision-making. See www.gefweb.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/ECA_Shaping_Climate%20Resilent_Development.pdf. | |||

| * Garnett, T. (2008) Cooking Up a Storm: Food, greenhouse gas emissions and our changing climate. Food Climate Research Network Centre for Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey, UK. | |||

| * Jones, A. (2006) A Life Cycle Analysis of UK Supermarket Imported Green Beans from Kenya. Fresh Insights No. 4. IIED/DFID/NRI, London/Medway, Kent. | |||

| * Magrath, J. and E. Sukali (2009) The Winds of Change: Climate change, poverty and the environment in Malawi. Oxfam International, Oxford. | |||

| * Muuru, J. (2009) Kenya's Flying Vegetables: Small farmers and the 'food miles' debate. Policy Voice Series. ], London. | |||

| * Plassman, K. and G. Edwards-Jones (2009) Where Does the Carbon Footprint Fall? Developing a carbon map of food production. IIED, London. See www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/16023IIED.pdf | |||

| * Smith, A. et al. (2005) . DEFRA, London. | |||

| * The Strategy Unit (2008) Food: An analysis of the issues. Cabinet Office, London. | |||

| * Wangler, Z. (2006) Sub-Saharan African Horticultural Exports to the UK and Climate Change: A literature review. Fresh Insights | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{cite book |title=Food Routes: Growing Bananas in Iceland and Other Tales from the Logistics of Eating |year=2019 |first=Robyn |last=Metcalfe |publisher=The MIT Press |isbn=978-0262039659}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * at | * | ||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * at | |||

| * | |||

| * at | |||

| * at | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Simple living}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Food Miles}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:30, 15 October 2024

Distance food is transported from production to consumption

Food miles is the distance food is transported from the time of its making until it reaches the consumer. Food miles are one factor used when testing the environmental impact of food, such as the carbon footprint of the food.

The concept of food miles originated in the early 1990s in the United Kingdom. It was conceived by Professor Tim Lang at the Sustainable Agriculture Food and Environment (SAFE) Alliance and first appeared in print in a report, "The Food Miles Report: The Dangers of Long-Distance Food Transport", researched and written by Angela Paxton.

Some scholars believe that an increase in the distance food travels is due to the globalization of trade; the focus of food supply bases into fewer, larger districts; drastic changes in delivery patterns; the increase in processed and packaged foods; and making fewer trips to the supermarket. These make a small part of the greenhouse gas emissions created by food; 83% of overall emissions of CO2 are in production phases.

Several studies compare emissions over the entire food cycle, including production, consumption, and transport. These include estimates of food-related emissions of greenhouse gas 'up to the farm gate' versus 'beyond the farm gate'. In the UK, for example, agricultural-related emissions may account for approximately 40% of the overall food chain (including retail, packaging, fertilizer manufacture, and other factors), whereas greenhouse gases emitted in transport account for around 12% of overall food-chain emissions.

A 2022 study suggests global food miles CO2 emissions are 3.5–7.5 times higher than previously estimated, with transport accounting for about 19% of total food-system emissions, albeit shifting towards plant-based diets remains substantially more important.

The concept of "food miles" has been criticised, and food miles are not always correlated with the actual environmental impact of food production. In comparison, the percentage of total energy used in home food preparation is 26% and in food processing is 29%, far greater than transportation.

Overview

The concept of food miles is part of the broader issue of sustainability which deals with a large range of environmental, social and economic issues, including local food. The term was coined by Tim Lang (now Professor of Food Policy, City University, London) who says: "The point was to highlight the hidden ecological, social and economic consequences of food production to consumers in a simple way, one which had objective reality but also connotations." The increased distance traveled by food in developed countries was caused by the globilization of food trade, which increased by four times since 1961. Food that is transported by road produces more carbon emissions than any other form of transported food. Road transport produces 60% of the world's food transport carbon emissions. Air transport produces 20% of the world's food transport carbon emissions. Rail and sea transport produce 10% each of the world's food transport carbon emissions.

Although it was never intended as a complete measure of environmental impact, it has come under attack as an ineffective means of finding the true environmental impact. For example, a DEFRA report in 2005 undertaken by researchers at AEA Technology Environment, entitled The Validity of Food Miles as an Indicator of Sustainable Development, included findings that "the direct environmental, social and economic costs of food transport are over £9 billion each year, and are dominated by congestion." The report also indicates that it is not only how far the food has travelled but the method of travel in all parts of the food chain that is important to consider. Many trips by personal cars to shopping centres would have a negative environmental impact compared to transporting a few truckloads to neighbourhood stores that can be easily reached by walking or cycling. More emissions are created by the drive to the supermarket to buy air freighted food than was created by the air freighting in the first place. Also, the positive environmental effects of organic farming may be compromised by increased transportation, unless it is produced by local farms. The Carbon Trust notes that to understand the carbon emissions from food production, all the carbon-emitting processes that occur as a result of getting food from the field to our plates need to be considered, including production, origin, seasonality and home care.

Food miles in business

A recent study led by Professor Miguel Gomez (Applied Economics and Management), at Cornell University and supported by the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future found that in many instances, the supermarket supply chain did much better in terms of food miles and fuel consumption for each pound compared to farmers markets. It suggests that selling local foods through supermarkets may be more economically viable and sustainable than through farmers markets.

Calculating food miles

With processed foods that are made of many different ingredients, it is very complicated, though not impossible, to calculate the CO2 emissions from transport by multiplying the distance travelled of each ingredient, by the carbon intensity of the mode of transport (air, road or rail). However, as both Tim Lang and the original Food Miles report noted, the resulting number, although interesting, cannot give the whole picture of how sustainable – or not – a food product is.

Wal-Mart publicized a press releasing that stated food travelled 1,500 miles (2,400 km) before it reaches customers. The statistics aroused public concern about food miles. According to Jane Black, a food writer who covers food politics, the number was derived from a small database. The 22 terminal markets from which the data was collected handled 30% of the United States produce.

Some iOS and Android apps allow consumers to get information about food products, including nutritional information, product origin, and the distance the product travelled from its production location to the consumer. Such apps include OpenLabel, Glow, and Open Food Facts. These apps may rely on barcode scanning. Also, smartphones can scan a product's QR code, after which the browser opens up showing the production location of the product (i.e. Farm to Fork project, ...).

Criticism

Fair trade

According to Oxfam researchers, there are many other aspects of the agricultural processing and the food supply chain that also contribute to greenhouse gas emissions which are not taken into account by simple "food miles" measurements. There are benefits to be gained by improving livelihoods in poor countries through agricultural development. Smallholder farmers in poor countries can often improve their income and standard of living if they can sell to distant export markets for higher value horticultural produce, moving away from the subsistence agriculture of producing staple crops for their own consumption or local markets.

However, exports from poor countries do not always benefit poor people. Unless the product has a Fairtrade certification label, or a label from another robust and independent scheme, food exports might make a bad situation worse. Only a very small percentage of what importers pay will end up in the hands of plantation workers. Wages are often very low and working conditions bad and sometimes dangerous. Sometimes the food grown for export takes up land that had been used to grow food for local consumption, so local people can go hungry.

Energy used in production as well as transport

Researchers say a more complete environmental assessment of food that consumers buy needs to take into account how the food has been produced and what energy is used in its production. A recent Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) case study indicated that tomatoes grown in Spain and transported to the United Kingdom may have a lower carbon footprint in terms of energy than heated greenhouses in the United Kingdom.

According to German researchers, the food miles concept misleads consumers because the size of transportation and production units is not taken into account. Using the methodology of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) in accordance with ISO 14040, entire supply chains providing German consumers with food were investigated, comparing local food with food of European and global provenance. Large-scale agriculture reduces unit costs associated with food production and transportation, leading to increased efficiency and decreased energy use per kilogram of food by economies of scale. Research from the Justus Liebig University Giessen show that small food production operations may cause even more environmental impact than bigger operations in terms of energy use per kilogram, even though food miles are lower. Case studies of lamb, beef, wine, apples, fruit juices and pork show that the concept of food miles is too simple to account for all factors of food production.

A 2006 research report from the Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit at Lincoln University, New Zealand counters claims about food miles by comparing total energy used in food production in Europe and New Zealand, taking into account energy used to ship the food to Europe for consumers. The report states, "New Zealand has greater production efficiency in many food commodities compared to the UK. For example New Zealand agriculture tends to apply fewer fertilizers (which require large amounts of energy to produce and cause significant CO2 emissions) and animals are able to graze year round outside eating grass instead of large quantities of brought-in feed such as concentrates. In the case of dairy and sheep meat production NZ is by far more energy efficient, even including the transport cost, than the UK, twice as efficient in the case of dairy, and four times as efficient in case of sheep meat. In the case of apples, NZ is more energy-efficient even though the energy embodied in capital items and other inputs data was not available for the UK."

Other researchers have contested the claims from New Zealand. Professor Gareth Edwards-Jones has said that the arguments "in favour of New Zealand apples shipped to the UK is probably true only or about two months a year, during July and August, when the carbon footprint for locally grown fruit doubles because it comes out of cool stores."

Studies by Dr. Christopher Weber et al. of the total carbon footprint of food production in the U.S. have shown transportation to be of minor importance, compared to the carbon emissions resulting from pesticide and fertilizer production, and the fuel required by farm and food processing equipment.

Livestock production as a source of greenhouse gases

Farm animals account for between 20% and 30% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. That figure includes the clearing of land to feed and graze the animals. Clearing land of trees, and cultivation, are the main drivers of farming emissions. Deforestation eliminates carbon sinks, accelerating the process of climate change. Cultivation, including the use of synthetic fertilisers, releases greenhouse gases such as nitrous oxide. Nitrogen fertiliser is especially demanding of fossil fuels, as producing a tonne of it takes 1.5 tonnes of oil.

Meanwhile, it is increasingly recognised that meat and dairy are the largest sources of food-related emissions. The UK's consumption of meat and dairy products (including imports) accounts for about 8% of national greenhouse gas emissions related to consumption.

According to a study by engineers Christopher Weber and H. Scott Matthews of Carnegie Mellon University, of all the greenhouse gases emitted by the food industry, only 4% comes from transporting the food from producers to retailers. The study also concluded that adopting a vegetarian diet, even if the vegetarian food is transported over very long distances, does far more to reduce greenhouse gas emissions than does eating a locally grown diet. They also concluded that "Shifting less than one day per week's worth of calories from red meat and dairy products to chicken, fish, eggs, or a vegetable-based diet achieves more GHG reduction than buying all locally sourced food." In other words, the amount of red meat consumption is much more important than food miles.

"Local" food miles

A commonly ignored element is the last mile. For example, a gallon of gasoline could transport 5 kg of meat over 60,000 miles (97,000 km) by road (40 tonner at 8 mpg) in bulk transport, or it could transport a single consumer only 30 or 40 miles (64 km) to buy that meat. Thus foods from a distant farm that are transported in bulk to a nearby store consumer can have a lower footprint than foods a consumer picks up directly from a farm that is within driving distance but farther away than the store. This can mean that doorstep deliveries of food by companies can lead to lower carbon emissions or energy use than normal shopping practices. Relative distances and mode of transportation make this calculation complicated. For example, consumers can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of the last mile by walking, bicycling, or taking public transport. Another impact is that goods being transported by large ships very long distances can have lower associated carbon emissions or energy use than the same goods traveling by truck a much shorter distance.

Lifecycle analysis, rather than food miles

Lifecycle analysis, a technique that meshes together a wide range of different environmental criteria including emissions and waste, is a more holistic way of assessing the real environmental impact of the food we eat. The technique accounts for energy input and output involved in the production, processing, packaging and transport of food. It also factors in resource depletion, air pollution and water pollution and waste generation/municipal solid waste.

A number of organisations are developing ways of calculating the carbon cost or lifecycle impact of food and agriculture. Some are more robust than others but, at the moment, there is no easy way to tell which ones are thorough, independent and reliable, and which ones are just marketing hype.

Even a full lifecycle analysis accounts only for the environmental effects of food production and consumption. However, it is one of the widely agreed three pillars of sustainable development, namely environmental, social and economic.

See also

References

- Engelhaupt, E (2008). "Do food miles matter?". Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (10): 3482. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.3482E. doi:10.1021/es087190e. PMID 18546672.

- http://www.city.ac.uk/communityandhealth/phpcfp/foodpolicy/index.html. He explains its history in this article Tim Lang (2006). 'locale / global (food miles)', Slow Food (Bra, Cuneo Italy), 19, May 2006, pp. 94–97

- The SAFE Alliance merged with the National Food Alliance in 1999 to become Sustain: the alliance for better food and farming http://www.sustainweb.org/. Professor Tim Lang chaired Sustain from 1999 to 2005.

- ^ Paxton, A (1994). "The Food Miles Report: The Dangers of Long-Distance Food Transport". SAFE Alliance, London, UK. https://www.sustainweb.org/publications/the_food_miles_report/

- Iles, A. (2005). "Learning in sustainable agriculture: Food miles and missing objects". Environmental Values, 14, 163–83

- Weber, C.; Matthews, H. (2008). "Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States". Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (10): 3508–3513. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.3508W. doi:10.1021/es702969f. PMID 18546681.

- "Sources and Resources for 'Local Food: The Economics'". Worldwatch Institute. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2009.

- Garnett 2011, Food Policy

- "Climate impact of food miles three times greater than previously believed, study finds". The Guardian. June 20, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- Li, Mengyu; Jia, Nanfei; Lenzen, Manfred; Malik, Arunima; Wei, Liyuan; Jin, Yutong; Raubenheimer, David (June 2022). "Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions". Nature Food. 3 (6): 445–453. doi:10.1038/s43016-022-00531-w. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37118044. S2CID 249916086.

- "How much do food miles matter and should you buy local produce?". New Scientist. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- John Hendrickson, "Energy use in the U.S. Food System: A summary of existing research and analysis." Sustainable Farming (Ste. Anne de Bellevue, Quebec), vol. 7, no. 4. Fall 1997.

- Tim Lang (2006). 'locale / global (food miles)', Slow Food (Bra, Cuneo Italy), 19, May 2006, p.94-97

- Erik Millstone and Tim Lang, The Atlas of Food, Earthscan, London, 1963, p. 60.

- Smith, A. et al. (2005) The Validity of Food Miles as an Indicator of Sustainable Development: Final report. DEFRA, London. See https://statistics.defra.gov.uk/esg/reports/foodmiles/default.asp Archived May 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Food, the carbon story", The Carbon Trust, 15 March 2012. Retrieved on 20 January 2015.

- Prevor, Jim (October 1, 2010). "Jim Prevor's Perishable Pundit". Retrieved July 20, 2011.

- Black, Jane (September 17, 2008). "How the press got the idea that food travels 1500 miles from farm to plate". Slate Magazine. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- Han, Esther (March 20, 2015). "Mobile barcode scanning apps empower consumers to shop with confidence". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- "Interview: OriginTrail, an app that tells you where your food is from". March 9, 2016.

- Trebar, Mira (April 15, 2014). "How consumers can track products at the touch of a smartphone button". the Guardian.

- ^ Chi, Kelly Rae, James MacGregor and Richard King (2009). Fair Miles: Recharting the food miles map. IIED/Oxfam.

- Chi, 2009, p. 9.

- MacGregor, J.; Vorley, B (2006) Fair Miles? Weighing environmental and social impacts of fresh produce exports from Sub-Saharan Africa to the UK. Fresh Insights no.9. International Institute for Environment and Development/ Natural Resources Institute, London, UK, 18 pp. http://www.dfid.gov.uk/r4d/SearchResearchDatabase.asp?OutPutId=173492

- C. Dolan, J. Humphrey, and C. Harris-Pascal, "Value Chains and Upgrading: The Impact of U.K. Retailers on the Fresh Fruit and Vegetables Industry in Africa," Institute of Development Studies Working Paper 96, University of Sussex, 1988.

- Action Aid is one of many organisations drawing attention to this problem and campaigning to improve this situation - http://www.actionaid.org.uk

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). "Defra, UK - Science Search". defra.gov.uk.

- "PT_Ecology of Scale". www.uni-giessen.de. Archived from the original on December 6, 2009.

- Schlich E, Fleissner U: The Ecology of Scale. Assessment of Regional Energy Turnover and Comparison with Global Food. Int J LCA 10 (3) 219-223:2005.

- Schlich E: Energy Economics and the Ecology of Scale in the Food Business. In: Caldwell PG and Taylor EV (editors): New Research on Energy Economics. Nova Science Publishers Hauppauge NY:2008.

- Saunders, C; Barber, A; Taylor, G, Food Miles – Comparative Energy/Emissions Performance of New Zealand's Agriculture Industry Archived May 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine (2006). Research Report No. 285. Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit, Lincoln University, Christchurch, New Zealand.

- McWilliams, James E. (August 6, 2007). "Food that travels well". The New York Times.

- 'Food miles' minor element of carbon footprint, http://www.freshplaza.com/news_detail.asp?id=40471. See also a range of publications by Professor Edwards-Jones and a team of researchers at Bangor University, http://www.bangor.ac.uk/senrgy/staff/edwards.php.en Archived September 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Weber, Christopher L. (2008). "Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States". Environmental Science. 42 (10): 3508–3513. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.3508W. doi:10.1021/es702969f. PMID 18546681.

- To see details of the United Nations research into meat and the environment, visit: http://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/news/2006/1000448/index.html Archived March 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. See also Steinfeld, H et al. (2006) Livestock's long shadow: Environmental issues and options. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome. "全讯网 论坛,粉,紫水晶手链,全讯网 论坛专题内容". Archived from the original on August 6, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- Garnett, T (2007) Meat and dairy production and consumption. Exploring the livestock sector's contribution to the UK's greenhouse gas emissions and assessing what less greenhouse gas intensive systems of production and consumption might look like Working paper produced a part of the work of the Food Climate Research Network, Centre for Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey https://www.fcrn.org.uk/sites/default/files/TGlivestock_env_sci_pol_paper.pdf

- "How much does animal agriculture and eating meat contribute to global warming?". Skeptical Science.

- Food miles are less important to environment than food choices, study concludes, Jane Liaw, special to Mongabay, June 2, 2008

- Coley, D. A., Howard, M. and Winter, M., 2009. Local food, food miles and carbon emissions: A comparison of farm shop and mass distribution approaches. Food Policy, 34 (2), pp. 150-155.

- Coley, D. A., Howard, M. and Winter, M., 2011. Food miles: time for a re-think? British Food Journal, 113 (7), pp. 919-934.

- Chi, Kelly Rae, James MacGregor and Richard King (2009). Fair Miles: Recharting the food miles map. IIED/Oxfam. http://www.iied.org/pubs/display.php?o=15516IIED – p16

- Examples include http://www.carbontrustcertification.com/ and www.cffcarboncalculator.org.uk and https://carboncloud.com/

- World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future, (1987). Oxford University Press. Often known as the Brundtland report, after the Chair of the Commission, Gro Harlem Brundtland.

Sources

| This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation and footnoting. (March 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Edwards-Jones, G.; Milà; Canals, L.; Hounsome, N.; Truninger, M.; Koerber, G.; Hounsome, B.; et al. (2008). "Testing the assertion that 'local food is best': the challenges of an evidence-based approach". Trends in Food Science & Technology. 19 (5): 265–274. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2008.01.008.

- Waye, V (2008). "Carbon Footprints, Food Miles and the Australian Wine Industry". Melbourne Journal of International Law. 9: 271–300.

- Weber, C.; Matthews, H. (2008). "Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States". Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (10): 3508–3513. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.3508W. doi:10.1021/es702969f. PMID 18546681.

- Iles, A (2005). "Learning in sustainable agriculture: Food miles and missing objects". Environmental Values. 14 (2): 163–183. doi:10.3197/0963271054084894.

- Engelhaupt, E (2008). "Do food miles matter?". Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (10): 3482. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.3482E. doi:10.1021/es087190e. PMID 18546672.

- McKie, R. (2008). How the myth of food miles hurts the planet. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- Holt, D.; Watson, A. (2008). "Exploring the dilemma of local sourcing versus international development –the case of the Flower Industry" (PDF). Business Strategy and the Environment. 17 (5): 318–329. doi:10.1002/bse.623.

- Hogan, Lindsay and Sally Thorpe (2009). Issues in food miles and carbon labelling. ABARE (Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics)

- Chi, Kelly Rae, James MacGregor and Richard King (2009). Fair Miles: Recharting the food miles map. IIED/Oxfam.

- Blanke, M.; Burdick, B. (2005). "Food (miles) for thought: energy balance for locally-grown versus imported apple fruit". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 12 (3): 125–127. Bibcode:2005ESPR...12..125B. doi:10.1065/espr2005.05.252. PMID 15986993. S2CID 33467271.

- Borot, A., J. MacGregor and A. Graffham(eds) (2008). Standard Bearers: Horticultural exports and private standards in Africa. IIED, London.

- DEFRA (2009) Food Statistics Pocketbook 2009. DEFRA, London.

- ECA (2009) Shaping Climate-Resilient Development: A framework for decision-making. See www.gefweb.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/ECA_Shaping_Climate%20Resilent_Development.pdf.

- Garnett, T. (2008) Cooking Up a Storm: Food, greenhouse gas emissions and our changing climate. Food Climate Research Network Centre for Environmental Strategy, University of Surrey, UK.

- Jones, A. (2006) A Life Cycle Analysis of UK Supermarket Imported Green Beans from Kenya. Fresh Insights No. 4. IIED/DFID/NRI, London/Medway, Kent.

- Magrath, J. and E. Sukali (2009) The Winds of Change: Climate change, poverty and the environment in Malawi. Oxfam International, Oxford.

- Muuru, J. (2009) Kenya's Flying Vegetables: Small farmers and the 'food miles' debate. Policy Voice Series. Africa Research Institute, London.

- Plassman, K. and G. Edwards-Jones (2009) Where Does the Carbon Footprint Fall? Developing a carbon map of food production. IIED, London. See www.iied.org/pubs/pdfs/16023IIED.pdf

- Smith, A. et al. (2005) The Validity of Food Miles as an Indicator of Sustainable Development: Final report. DEFRA, London.

- The Strategy Unit (2008) Food: An analysis of the issues. Cabinet Office, London.

- Wangler, Z. (2006) Sub-Saharan African Horticultural Exports to the UK and Climate Change: A literature review. Fresh Insights

Further reading

- Metcalfe, Robyn (2019). Food Routes: Growing Bananas in Iceland and Other Tales from the Logistics of Eating. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262039659.

External links

- Food Miles Calculator

- Fairtrade Foundation

- Fairtrade Labelling Organisations (international)

- IIED

- Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences

- Food miles at DEFRA

- The Validity of Food Miles as an Indicator of Sustainable Development