| Revision as of 22:35, 21 January 2009 editNoclador (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users66,379 editsm →Annexation by Italy← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:50, 23 December 2024 edit undoMai-Sachme (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,499 editsNo edit summary | ||

| (294 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|None}} | |||

| {{POV|date=July 2008}} | |||

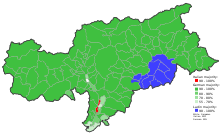

| [[File:Tirol-Südtirol-Trentino with extraprovincial comuni.png|thumb|250px|The former Tyrol today | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=January 2009}} | |||

| [[Image:Tirol-Suedtirol-Trentino.png|thumb|250px|The former Tyrol today (excluding Cortina and Livinallongo) | |||

| ---- | ---- | ||

| {{ |

{{Legend|#fe7f7f|] (]) }} | ||

| {{ |

{{Legend|#f7b77b|] (]) }} | ||

| {{ |

{{Legend|#7b7bf7|] (Italy) }} | ||

| {{legend|#73e673|Parts of the former county now within other Italian provinces}} | |||

| ]] | |||

| Modern-day ''']''', an autonomous Italian province created in 1948, was part of the ] ] until 1918 (then known as ''Deutschsüdtirol'' and occasionally ''Mitteltirol''<ref name="Ref_a">{{Cite web |url=http://www.europaregion.info/it/19.asp |title=Euregio Tirolo-Alto Adige-Trentino {{!}} Finalità |access-date=2009-02-12 |archive-date=2008-07-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080705111255/http://www.europaregion.info/it/19.asp |url-status=dead }}</ref>). It was annexed by ] following the defeat of the ] in ]. It has been part of a cross-border joint entity, the ] ], since 2001.<ref name="Ref_b">{{Cite web |url=http://www.europaregion.info/en/19.asp |title=Euregio Tyrol-South Tyrol-Trentino {{!}} Objectives |access-date=2009-02-12 |archive-date=2008-05-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080509141326/http://www.europaregion.info/en/19.asp |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Present day '''Alto Adige-South Tyrol''' coincides with the ], a ] created in 1927. Until 1918 its area was part of the ] ] and it was ceded to ] after ]. The area is part of the Tyrol-South Tyrol/Alto Adige-Trentino ] since 1998. | |||

| == |

==Before the 19th century== | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|History of Tyrol}} | ||

| Historically the region was home to a series of autochthonous cultures occupying roughly the area of the later county of Tyrol. The most prominent are the late ] ] and ] ] cultures. | |||

| ===Antiquity=== | |||

| In 15 BCE the region was conquered by the Romans and its northern and eastern part were incorporated into the ] as the provinces of ] and ] respectively, while the part south of and including the area around the modern day cities of ] and ] became part of ] ''Regio X''. | |||

| In 15 BC the region, inhabited by the Alpine population of the ], was conquered by the ] commanders ] and ], and its northern and eastern parts were incorporated into the provinces of ] and ] respectively,<ref name="Woelk / Palermo / Marko">{{Cite book | last1 = Woelk | first1 = Jens |last2 = Palermo | first2 = Franceso |last3 = Marko | first3 = Joseph |title = Tolerance Through Law: Self Governance and Group Rights In South Tyrol | publisher = Transaction Publishers | year = 2008 | isbn = 978-90-47-43177-0 }}</ref> while the southern part including the lower ] and ] valleys around the modern-day city of ] up to present-day ] and ] (''Sublavio'') became part of ] (''Italia''), ]. The mountainous area then mainly was a transit country along ] crossing the ] like the ], settled by Romanised ] and ] tribes which had adopted the ] (]) language.<ref>Peter W. Haider (1985). ''Von der Antike ins frühe Mittelalter.'' In Josef Fontana, Peter W. Haider (eds). ''Geschichte des Landes Tirol.'' Tyrolia-Athesia, Innsbruck-Bozen, pp. 125–264.</ref> | |||

| ===Middle Ages=== | |||

| After the conquest of Italy by the ] Tyrol became part of the ] from the 5th to the 6th century. After the fall of the Ostrogothic Kingdom in 553 the Germanic tribe of the ] invaded Italy and founded the Langobard ], which no longer included all of Tyrol, but only its southern part. The northern part of Tyrol came under the influence of the ], while the east probably was part of ]. | |||

| After the conquest of Italy by the ] in 493, Tyrol became part of the ] of Italy in the 5th and the 6th centuries. Already in 534 the western ] region fell to the ] ('']''), while after the final collapse of the Ostrogothic Kingdom in 553 West Germanic ] entered the region from the north. When the ] invaded Italy in 568 and founded the ], it also included the ] with the southernmost part of Tyrol. The border with the German ] of ] ran southwest of present-day Bolzano along the Adige River, with ] and the right bank (including ], ] and the area up to ] on the ] River) belonging to the Lombard kingdom. While the boundary remained unchanged for centuries, Bavarian settlers further migrated southwards down to Salorno (''Salurn''). The population was ] by the Bishops of ] and ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| In the years 1007 and 1027 the Emperors of the ] granted the counties of ], ] and ] to the ], in 1027 the county of ] was granted to the ], followed 1091 by the county of ]. | |||

| In 1027 Emperor ] established the ] in order to secure the route up to the ]. He ceded the counties of ], Bolzano and Vinschgau to the Trent bishops and finally separated the territory on the east bank of the Adige River down to ] (''Deutschmetz'') from the Imperial ]. The '']'' of ''Norital'', including the ], the ] and the ], was granted to the newly established ], followed in 1091 by the ]. Over the centuries, the episcopal reeves ('']'') residing at ] near ] extended their territory over much of the region and came to surpass the power of the bishops who were nominally their ] lords. The later ] reached independence from the ] during the deposition of Duke ] in 1180. Also in this period, from the late twelfth to the thirteenth centuries, have been established along the Brenner axis almost all of up-today's existing urban settlements, which can be categorized as marked-formed, not very densely populated ''small-towns'', such as ], ], ] or ].<ref>Hannes Obermair (2007). . ''Concilium medii aevi'', '''10''', pp. 53-76</ref> | |||

| Over the centuries, the ]s residing in ], near ], extended their territory over much of the region and came to surpass the power of the bishops, who were nominally their ] lords. Later counts came to hold much of their territory directly from the ]. | |||

| ===Modern Age=== | |||

| Following defeat by ] in 1805, ] was forced to cede Tyrol to the ] in the ]. Tyrol as a part of Bavaria became a member of the ] in 1806. Tyrol remained under Bavaria and the ] until it was returned to ] following the decisions at the ] in 1814. Integrated into the ], from 1867 onwards it was a ''Kronland'' of ], the western half of ]. | |||

| From the 13th century they held much of their territory ] from the ] and were elevated to ] in 1504. | |||

| Following defeat by ] in 1805, the ] was forced to cede the northern part of Tyrol to the ] in the ]. It became a member of the ] in 1806. Tyrol remained split between Bavaria and the ] until it was returned to Austria by the ] in 1814. Integrated into the Austrian Empire, from 1867 it was a ''Kronland'' (Crown Land) of ], the western half of ]. | |||

| ==Time of nationalism== | |||

| {{see|Italian irredentism}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Age of nationalism== | |||

| After ] the ]s started in all Europe. | |||

| {{Further|Italian irredentism}} | |||

| Even in Italy, several groups began to push the idea of a unified national state (see ]). At the time, the struggle for Italian unification was perceived to be waged primarily against the ], which was the ] power in Italy and the single most powerful force against unification. The ] vigorously repressed nationalist sentiments growing in Italy, most of all during ] and in the following years. | |||

| Italy finally reached its ] in ]; ] was annexed in 1866 and ] with ], in ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| The process of unification of the Italian people in a ] was seen as incomplete, because several Italians communities remained under foreign rule. This situation created the so-called Italian ] (see '']''). | |||

| After the ], ] emerged as the dominant ideology in Europe. In Italy several intellectuals and groups began to push the idea of a unified nation-state (see ]). At the time, the struggle for ] was largely waged against the Austrian Empire, which was the ] power in Italy and the single most powerful adversary to unification. The Austrian Empire vigorously repressed the growing nationalist sentiment among Italian elites, most of all during ] and the following years. Italy finally attained ] in 1861, annexed ] in 1866, and ], including ], in 1870. | |||

| In ] Italy signed a defensive Alliance with Austria-Hungary and ] (see ]). However, Italian public opinion remained unenthusiastic about their country's alignment with Austria-Hungary, still perceiving it as the historical enemy of Italy. In the years before ], many distinguished military analysts predicted that Italy would change sides. | |||

| However, for many nationalist intellectuals and political leaders, the process of unification of the Italian peninsula under a single ] was not complete. This was because several areas inhabited by Italian-speaking communities remained under what was seen as foreign rule. This situation gave rise to the idea that parts of Italy were still ''unredeemed'', hence Italian ] became an important ideological component of the political life of the ]: see '']''. | |||

| The Kingdom of Italy had declared its neutrality at the beginning of the ], because the ] was a defensive one, requiring its members to come under attack first. Many Italians were still hostile to Austrian historical and continuing occupations of ethnically Italian areas. Austria-Hungary requested Italian neutrality, while the ] (Great Britain, France and Russia) its intervention. A large opinion movement in Italy, asked to join the conflict declaring war to Austria, with the aim to gain the "]" territories. | |||

| In 1882 Italy signed a defensive alliance with Austria-Hungary and ] (see ]). However, Italian public opinion remained unenthusiastic about the alignment with Austria-Hungary, still perceiving it as the historical enemy of Italy. In the years before ], many distinguished military analysts predicted that Italy would change sides. | |||

| With the ], signed in April 1915, Italy agreed to declare war against the ], in exchange (among other things) of territorial gains in the Austrian crown-lands of ], ] and ], homeland of large Italian minorities. The war against the Austro-Hungarian Empire was declared in May, 24, 1915. | |||

| Italy declared its neutrality at the beginning of ], because the Triple Alliance was a defensive one, requiring its members to come under attack to come into effect. Many Italians were still hostile to Austrian historical and continuing occupation of ethnically Italian areas. Austria-Hungary requested Italian neutrality, while the ] (Great Britain, France and Russia) demanded its intervention. Many people in Italy wanted the country to join the conflict on the side of the Triple Entente, with the aim of gaining the "]" territories. | |||

| In October 1917, the Italian army was defeated in the ], and was forced to put a new defensive line along the ] river. On June 1918, an Austro-Hungarian offensive against the Piave line was repulsed (see ]). On October, 24, 1918 Italy launched its final offensive against the ], which consequently collapsed <ref></ref> (see ]). The subsequent ] was signed on November, 3. It was agreed to set it into force at 3.00 PM of November 4. In the following days the Italian Army completed the occupation of all Tirol (including ]), according to the armistice terms. | |||

| Under the secret ], signed in April 1915, Italy agreed to declare war against the ] in exchange for (among other things) territorial gains in the Austrian crown lands of ], ] and ], homeland of large Italian minorities. War against the Austro-Hungarian Empire was declared on May 24, 1915. | |||

| == Annexation by Italy == | |||

| ] | |||

| Under the ] Italy ''"shall obtain the Trentino, Cisalpine Tyrol with its geographical and natural frontier (the Brenner frontier)"''<ref>Treaty of London; Article 4</ref> and after the ceasefire of ] (Nocember 3rd, 1918) Italian Troops occupied uncontested the territory and as stipulated in the ceasefire agreement marched further into ] and occupied ] and the ].<ref name="ZIS"> {{citation|url=http://zis.uibk.ac.at/stirol_doku/welcome_chronik.phtml | |||

| |first=Institute of contemporary history; University of Innsbruck|title=South Tyrol Documentation}} {{de}} </ref> | |||

| In October 1917, the Italian army was defeated in the ], and was forced back to a defensive line along the ] river. In June 1918, an Austro-Hungarian offensive against the Piave line was repulsed (see ]). On October 24, 1918, Italy launched its final offensive against the ], which consequently collapsed<ref name="Ref_c"></ref> (see ]). The ] was signed on November 3. It came into force at 3.00 pm on November 4. In the following days the Italian Army completed the occupation of all Tirol (including ]), according to the armistice terms. | |||

| At first the territory was governed by military regime under General ], directly subordinated to the ]. One of the first orders was to hermetically seal the border between South Tyrol and all foreign nations. People were not allowed to cross the new frontier, postal service was interrupted, as was the flow of goods; censorship was introduced and officials, not born in the area were dismissed. On November 11th, 1919 General Pecori-Giraldi proclaimed in the name of King ] in Italian and German: ''"... Italy is willing, as sole united nation with full freedom of thought and expression, to allow nationals of other language the preservation of their own schools, private institutions and associations."'' On December 1st, 1919 the King promised in a speech: ''"a careful maintenance of local institutions and self-administration"''<ref name="ZIS"/><ref name="Province of Bolzano/Bozen"> {{citation||first=Parliament of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano/Bozen|title=A brief contemporary history of Alto Adige/Südtirol (1918-2002)}} {{en}} </ref> | |||

| ==Annexation by Italy== | |||

| During the negotiations between ] and the victorious ] powers in ] a petition signed unanimously by all mayors of South Tyrol was given to US-President ] and asked for help. <ref name="Steininger">{{cite book | last = Steininger | first = Rolf | title = South Tyrol, A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century | publisher = Transaction Publishers | date = 2003 | isbn = 0-7658-0800-5 }} </ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Wilson had announced his ] to a joint session of Congress January 8th, 1918 and the mayors reminded him of point 9: ''"A readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality."''"<ref name="President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points">{{cite web|last=Wilson|first=Woodrow|date=1918-01-08|url=http://www.lib.byu.edu/~rdh/wwi/1918/14points.html|title=President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points|format=HTML|accessdate=2005-06-20}}</ref><ref name="The Conditions of Peace">{{cite web|last=Wilson|first=Woodrow|date=1918-01-08|url=http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17427/17427-h/17427-h.htm#THE_CONDITIONS_OF_PEACE|title=The Conditions of Peace|format=HTML|accessdate=2005-06-20}}</ref><ref name="Sterling J. Kernek">Sterling J. Kernek, "Woodrow Wilson and National Self-Determination along Italy's Frontier: A Study of the Manipulation of Principles in the Pursuit of Political Interests", ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'', Vol. 126, No. 4. (Aug., 1982), pp. 243-300 (246)</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Under the secret ], Italy ''"shall obtain the Trentino, Cisalpine Tyrol with its geographical and natural frontier (the Brenner frontier)"''<ref name="Ref_d">Treaty of London; Article 4</ref> and after the ceasefire of ] (November 3, 1918) Italian troops occupied uncontested the territory and as stipulated in the ceasefire agreement marched into ] and occupied ] and the ] valley.<ref name="ZIS">{{Cite web | url = http://zis.uibk.ac.at/stirol_doku/welcome_chronik.phtml | last = Institute of contemporary history; University of Innsbruck | title = South Tyrol Documentation | language = de | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090822041210/http://zis.uibk.ac.at/stirol_doku/welcome_chronik.phtml | archive-date = 2009-08-22 }}</ref> | |||

| But when the ] was signed on September 10th, 1919 Italy was nonetheless given by Article 27, section 2 the ethnic German territories South of the Alpine watershed: | |||

| During the negotiations between ] and the victorious ] powers in ] a petition for help, signed by all the mayors of South Tyrol, was presented to US President ].<ref name="Steininger">{{Cite book | last = Steininger | first = Rolf | title = South Tyrol, A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century | publisher = Transaction Publishers | year = 2003 | isbn = 0-7658-0800-5 }}</ref> Wilson had announced his ] to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918, and the mayors reminded him of point 9: | |||

| <center> | |||

| {| class="prettytable" | align="center" | | |||

| <blockquote>"A readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality."<ref name="President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points">{{Cite web | last = Wilson | first = Woodrow | date = 1918-01-08 | url = http://www.lib.byu.edu/~rdh/wwi/1918/14points.html | title = President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points | access-date = 2005-06-20}}</ref><ref name="The Conditions of Peace">{{Cite web | last = Wilson | first = Woodrow | date = 1918-01-08 | url = http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17427/17427-h/17427-h.htm#THE_CONDITIONS_OF_PEACE | title = The Conditions of Peace | access-date = 2005-06-20}}</ref><ref name="Sterling J. Kernek">Sterling J. Kernek, "Woodrow Wilson and National Self-Determination along Italy's Frontier: A Study of the Manipulation of Principles in the Pursuit of Political Interests", ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'', Vol. '''126''', No. ''4''. (Aug., 1982), pp. 243-300 (246)</ref></blockquote> | |||

| !'''Article 27''' | |||

| |- | |||

| But when the ] was signed on September 10, 1919, Italy was given by Article 27, section 2 the ethnic German territories south of the Alpine watershed. | |||

| |<center>The frontiers of Austria shall be fixed as follows (see annexed Map):</center>2. With Italy:<br /> From the point 2645 (Gruben Joch) eastwards to point 2915 (Klopaier Spitz), a line to be fixed on the ground passing through point 1483 on the Reschen-Nauders road; thence eastwards to the summit of Dreiherrn Spitz (point 3505), the watershed between the basins of the Inn to the north and the Adige, to the south; thence generally south-south eastwards to Point 2545 (Marchkinkele), the watershed between the basins of the Drave to the east and the Adige to the west; thence south-eastwards to point 2483 (Helm Spitz), a line to be fixed on the ground crossing the Drave between Winnbach and Arnbach; thence east-south-eastwards to point 2050 (Osternig) about 9 kilometres north-west of Tarvis, the watershed between the basins of the Drave on the north and successively the basins of the Sextenbach, the Piave and the Tagliamento on the south; thence east-south-eastwards to point 1492 (about 2 kilometres west of Thörl), the watershed between the Gail and the Gailitz; thence eastwards to point 1509 (Pec), a line to be fixed on the ground cutting the Gailitz south of the town and station of Thörl and passing through point 1270 (Cabin Berg). | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| </center> | |||

| It has been claimed that Wilson later complained about the annexation: | It has been claimed that Wilson later complained about the annexation: | ||

| <blockquote>"Already the president had, unfortunately, promised the Brenner Pass boundary to ], which gave to Italy some 150,000 Tyrolese Germans-an action which he subsequently regarded as a big mistake and deeply regretted. It had been before he had made a careful study of the subject...."<ref name="Ref_e">Ray Stannard Baker, Woodrow Wilson and World Settlement, New York, 1992, Vol. II, p. 146.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| "Already the president had, unfortunately, promised the Brenner-Pass boundary to ], which gave to Italy some 150,000 Tyrolese Germans-an action which he subsequently regarded as a big mistake and deeply regretted. It had been before he had made a careful study of the subject..."<ref>Ray Stannard Baker, Woodrow Wilson and World Settlement, New York, 1992, Vol. II, p. 146.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| As Italy had not yet adopted the ] by ], all the names of locations in the treaty |

As Italy had not yet adopted the ] created by ], all the names of locations in the treaty, except the Adige river, were in German (the same monolingual German approach to local names as in the Treaty of London). | ||

| {{Wikisource|Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye/Part II}} | |||

| On January 21st, 1921 the "Governatorato" was renamed ''Provincia di Trento''. On May 15th, 1921 the people of the area participated for the first and until April 18th, 1948 only free and democratic elections (South Tyroleans were not allowed to participate in the ]). The result was a resounding victory for the ''Deutscher Verband'' (German Association), which won close 90% in the purportedly Italian province and thus sent 4 deputies to Rome: ], ], ] and ].<ref name="Province of Bolzano/Bozen"/> | |||

| At first, the territory was governed by a military regime under General ], directly subordinated to the '']''. One of the first orders was to seal the border between South Tyrol and Austria. People were not allowed to cross, and the postal service and the flow of goods were interrupted; censorship was introduced and officials not born in the area were dismissed. On November 11, 1919, General Pecori-Giraldi proclaimed in the name of King ] in Italian and German: "... Italy is willing, as sole united nation with full freedom of thought and expression, to allow nationals of other language the preservation of their own schools, private institutions and associations." On December 1, 1919 the King promised in a speech: "a careful maintenance of local institutions and self-administration"<ref name="ZIS"/><ref name="Province of Bolzano/Bozen"> {{Cite journal | author = Parliament of the Autonomous Province of Bolzano/Bozen | title = A brief contemporary history of Alto Adige/Südtirol (1918-2002)}}</ref> | |||

| 1921 also saw a brutal attack by ] on a traditional local procession. On Sunday April 24th, 1921 the population of Bozen had organized a ''Trachtenumzug'' (] procession) to celebrate the opening of the spring trade fair. Although the General Civil Commissioner of the province Luigi Credaro was warned in advance by his colleagues from ], ], ] and ] about the intentions of the fascists there to go to Bozen to disturb the procession no precautions were taken by Credaro. After arriving by train in Bozen the approximately 280 out-of-province fascists were joined by about 120 from Bozen and proceed to attack the procession with clubs, pistols and hand grenades. The artisan Franz Innerhofer from Marling was shot dead and around 50 people injured in the attack. After the attack the military intervened and escorted the fascists back to the train station. Although Credaro under orders from the Italian Prime Minister ] had arrested two suspects in Innerhofers murder nobody was ever brought to justice for the attack as ] had threatened to come to Bozen with 2,000 fascists to free the two suspects by force, if not set free immediately. On this occasion Mussolini made also clear his policies regarding the people of South Tyrol:<ref name="ZIS"/><ref name="Steininger"/><ref name="Province of Bolzano/Bozen"/> | |||

| Italy formally annexed the territories on October 10, 1920. The administration passed from the military to the new ''Governatorato della Venezia Tridentina'' (Governorate of Venezia Tridentina) under ]. The term ''Venezia Tridentina'' had been proposed in 1863 by the Jewish ] ] from ], who sought to include all of the territories of the ] claimed by Italy into a wider region called ''Venezia'' (the ] was accordingly named ''Venezia Giulia''). The ''Governatorato'' included the present-day region of ] and the three ] communes of ], ] and ], today in the ]. The northern part of Tyrol, comprising ] and ], became what is today one of the nine ] of Austria.<ref name="ZIS"/><ref name="Steininger"/> | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| "If the Germans on both sides of the Brennero don't toe the line, then the fascists will teach them a thing or two about obedience. Alto Adige is Italian and bilingual, and no one would even dream of trying forcibly to Italianize these German immigrants. But neither may Germans imagine that they might push Italy back to Salorno and from there to the Lago di Garda. Perhaps the Germans believe that all Italians are like Credaro. If they do, they’re sorely mistaken. In Italy, there are hundreds of thousands of Fascists who would rather lay waste to Alto Adige than to permit the tricolore that flies above the Vetta d’Italia to be lowered. If the Germans have to be beaten and stomped to bring them to reason, then so be it, we’re ready. A lot of Italians have been trained in this business."<ref name="Steininger"/><ref>Archivio per l'Alto Adige, Ettore Tolomei, Annata XVI, Gleno (Alto Adige), 1921</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| On January 21, 1921, the ''Governatorato'', while retaining military and police control, ceded administrative control to the new provincial council of the ''Provincia di Venezia Tridentina'' in ]. On May 15, 1921, the people of the area participated for the first (and until April 18, 1948, the only) free and democratic elections (the people of Venezia Tridentina and Venezia Giulia did not participate in the ]). The result was a resounding victory for the ''Deutscher Verband'' (German Association), which won close to 90% of the votes and thus sent four deputies to Rome.<ref name="Province of Bolzano/Bozen"/> | |||

| === Language constellation === | |||

| At the time of its annexation, the territory of South Tyrol was inhabited by ]s. According to the ] of ], which listed four groups according to their spoken language, the area was inhabited by 89% ], 3.8% ], 2.9% ], and 4.3% speakers of other languages of the Austrian empire, altogether 251,000 people.<ref name="Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol">Oscar Benvenuto (ed.): ", Bozen/Bolzano 2007, p. 19, Table 11</ref> According to some sources, the census did not include some 9000 immigrants from Italy.<ref> Italians non included in 1910 census</ref> However, from the official provincial statistics of the ''Autonomous Province of South Tyrol'' it appears that Italian citizens were indeed registered in the census, although not necessarily as Italian-speakers.<ref name="Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol"/> | |||

| ==Rise of fascism== | |||

| == Italianization period== | |||

| Up to this time, the German-speaking population had not been subjected to violence and nor had the Italian authorities interfered with its cultural activities, traditions and schooling. This was about to change with the rise of fascism. The first hint of what was to come was experienced by the German population on Sunday April 24, 1921. The population of Bolzano-Bozen had organized a ] (a procession in traditional local costume) to celebrate the opening of the spring trade fair. The General Civil Commissioner of the province, Luigi Credaro, had been warned in advance by his colleagues from ], ], ] and ] of the intention of the fascists there to go to Bolzano-Bozen to disrupt the procession, but did not take any precautions. After arriving by train in Bolzano-Bozen the approximately 280 out-of-province fascists were joined by about 120 from Bolzano-Bozen, and proceeded to attack the procession with clubs, pistols and hand grenades. The teacher Franz Innerhofer from Marling was shot dead and around 50 people injured in the attack. After the attack the military intervened and escorted the fascists back to the station. Although Credaro, under orders from the Italian Prime Minister ], had two suspects in Innerhofer's murder arrested, nobody was brought to justice for the attack, as ] had threatened to come to Bolzano-Bozen with 2,000 fascists to free the two suspects by force if they were not set free immediately. Mussolini made clear his policies regarding the people of South Tyrol:<ref name="ZIS"/><ref name="Steininger"/><ref name="Province of Bolzano/Bozen"/> | |||

| {{see|Italianization|Prontuario dei nomi locali dell'Alto Adige}} | |||

| <blockquote>"If the Germans on both sides of the Brenner don't toe the line, then the fascists will teach them a thing or two about obedience. Alto Adige is Italian and bilingual, and no one would even dream of trying forcibly to Italianize these German immigrants. But neither may Germans imagine that they might push Italy back to Salorno and from there to the Lago di Garda. Perhaps the Germans believe that all Italians are like Credaro. If they do, they’re sorely mistaken. In Italy, there are hundreds of thousands of Fascists who would rather lay waste to Alto Adige than to permit the tricolore that flies above the Vetta d’Italia to be lowered. If the Germans have to be beaten and stomped to bring them to reason, then so be it, we’re ready. A lot of Italians have been trained in this business."<ref name="Steininger"/><ref name="Ref_f">Archivio per l'Alto Adige, Ettore Tolomei, Annata XVI, Gleno (Alto Adige), 1921</ref></blockquote> | |||

| The peace treaty signed in Saint Germain left Italy free of requirements to protect the German minority. The Italian government and the king ], however, assumed precise duties in this direction. | |||

| The King, during the "speech of the Crown" on December, 1, 1919, declared full respect for local autonomies and traditions. | |||

| ===Italianization=== | |||

| The protection proposals were soon fought by the rising influence of Fascism. In April 21, 1921, a group of fascist mobsters killed an elementary school teacher, ], who become later the symbol of the opposition to Fascism. In October 1922, the new Fascist government retired all the special dispositions created to protect linguistic minorities. All the ] were given just in the Italian version, and several family names were translated.{{fact}} | |||

| {{Main|Italianization of South Tyrol}} | |||

| ], ], commemorating the separation of South Tyrol, set up in 1923 in response to the prohibition of the original southern Tyrolean place names]] | |||

| In October 1922, the new Fascist government rescinded all the special dispensations that protected linguistic minorities. | |||

| The Italianization program had been started, and the Fascist regime charged ] and ] (a nationalist from ]) to drive it. | The Italianization program had been started, and the Fascist regime charged ] and ] (a nationalist from ]) to drive it. | ||

| Tolomei's “program in 23 points” was adopted. Among other things it decreed: | |||

| * the exclusive use of Italian language in the public offices | |||

| * the closure of greater part of the German schools | |||

| * incentives for immigrants from other Italian regions. | |||

| Tolomei's "program in 23 points" was adopted. Among other things it decreed: | |||

| The first forms of opposition to the regime appeared in 1925: a priest, ], opened the first "]", clandestine schools where teachers taught in the German language. | |||

| * exclusive use of Italian in the public offices; | |||

| * closure of the majority of the German schools; | |||

| * incentives for immigrants from other Italian regions. | |||

| The first forms of opposition to the regime appeared in 1925: a priest, ], opened the first "]", clandestine schools where teachers taught in German.<ref>{{Cite web | url = http://zis.uibk.ac.at/stirol_doku/stirol.html | last = Institute of contemporary history; University of Innsbruck; Rolf Steininger | title = Die Südtirolfrage| url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100920044318/http://zis.uibk.ac.at/stirol_doku/stirol.html | archive-date = 2010-09-20 }}</ref> | |||

| In 1926 the ancient institution of communal autonomy was abolished. |

In 1926 the ancient institution of communal autonomy was abolished. Throughout Italy the "]", appointed by the government, replaced the mayors and had to report to the "]". | ||

| A large industrial zone in Bolzano opened in 1935. It was followed by the immigration of many workers and their families from other parts of Italy (mainly from Veneto).<ref name="Steininger b">{{Cite book | last = Steininger | first = Rolf | title = Südtirol. Vom Ersten Weltkrieg bis zur Gegenwart | publisher = Studienverlag | year = 2003 | isbn = 3-7065-1348-X }}</ref> | |||

| The advent of ] in Germany gave hope to several people, especially young ones. ] was seen as a possible liberator of the Southern Tyrol. The ], a party close to Nazi ideals, was consequently founded. | |||

| In this period of oppression, National Socialist propaganda became more and more successful among young South Tyroleans,<ref name="Steininger" /> leading in 1934 to the formation of the illegal local Nazi organization of the ''Völkischer Kampfring Südtirols'' (VKS).<ref>{{cite book |author=Hannes Obermair |title="Großdeutschland ruft!" Südtiroler NS-Optionspropaganda und völkische Sozialisation – "La Grande Germania chiamaǃ" La propaganda nazionalsocialista sulle Opzioni in Alto Adige e la socializzazione 'völkisch' |publisher= South Tyrolean Museum of History |location=]|year=2021|pages=14–21|isbn=978-88-95523-36-1 }}</ref> | |||

| A large industrial zone in Bolzano was realized in 1935. It was followed by a strong immigration of workers, with their families, from other Italian lands (mainly from Veneto). | |||

| ===German-Italian option agreement=== | |||

| Nazi Germany annexed Austria in 1938; although Nazis were stationed at the ], ] obtained from Hitler reassurances about the Italian borders. | |||

| {{Main|South Tyrol Option Agreement}} | |||

| ] never claimed any part of the Southern Tyrol for his ], even before the alliance with ];<ref name="Ref_g">Mein Kampf</ref> in fact in '']'' (1924) he claimed that Germans were just a small and irrelevant minority in Southern Tyrol{{Citation needed | reason = Where is this found. | date = May 2012}} (this definition including also Trentino) and he acknowledged the German portion of Southern Tyrol as a permanent possession of Italy. Hitler writes in Book II of '']'', "But I do not hesitate to declare that, now the dice have fallen, I not only regard a reconquest of the South Tyrol by war as impossible, but that I personally would reject it in the conviction that for this question the flame of national enthusiasm of the whole German people could not be achieved to a degree which would offer the premise for victory."<ref name="Adolf Hitler">Adolf Hitler, ''Mein Kampf'', trans. Ralph Manheim (New York: The Houghton Mifflin Company, First Mariner Book edition, 1999), 229, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/mein-kampf-by-adolf-hitler-ralph-manheim-translation/.</ref> | |||

| ==German-Italian option agreement== | |||

| {{main|Alto Adige Option Agreement}} | |||

| ] never claimed any part of the Southern Tyrol for his ], even before the alliance with ]<ref>Mein Kampf</ref>; in fact in "'']''" (1924) he claimed that Germans were just a small and irrelevant minority in Southern Tyrol (this definition including also Trentino) and he definitely acknowledged that the German portion of Southern Tyrol as a permanent belonging of Italy. | |||

| In 1939, both dictators agreed to give the German-speaking population a choice |

In 1939, both dictators in order to solve any further dispute agreed to give the German-speaking population a choice in the ]: they could emigrate to neighbouring ] (including ] Austria) or stay in Italy and accept complete Italianisation. | ||

| South Tyrolean |

The South Tyrolean population was deeply divided. Those who wanted to stay (''Dableiber'') were condemned as traitors; those who left (''Optanten''), the majority, were defamed as ]. There was a plan to relocate the ''Optanten'' in Crimea (annexed to ]), but most were resettled in German-annexed Western Poland, where they were expelled or killed after the war. Because of the outbreak of World War II, this agreement was only partially carried out. | ||

| In |

In 1939 Mussolini decided to build an ], a military fortification to defend Italy's northern land border. | ||

| ==Annexation |

==Annexation by Nazi Germany== | ||

| In 1943, Mussolini was deposed and Italy surrendered to the Allies, who had invaded southern Italy via ]. German troops promptly invaded northern Italy and South Tyrol became part of the ], |

In 1943, Mussolini was deposed and Italy surrendered to the ], who had invaded southern Italy via ]. German troops promptly invaded and occupied northern Italy to help Mussolini's side against the Allies and new Italy, and South Tyrol became part of the ], along with ] ''de facto'' annexed to ]. Many German-speaking South Tyroleans, after years of linguistic oppression and discrimination by Fascist Italy, wanted revenge upon ethnic Italians living in the area (particularly in the larger cities) but were mostly prevented from doing so by the occupying Nazis, who still considered Mussolini head of the ] and wanted to preserve good relations with the Italian Fascists, still supporting Mussolini against the Allies. Although the Nazis were able to recruit South Tyrolean youth and to capture local Jews, they prevented anti-Italian feelings from getting out of hand. Mussolini, who wanted to set up his new pro-German Italian Social Republic in Bolzano, was still a Nazi ally. | ||

| The region largely escaped fighting |

The region largely escaped fighting, and its mountainous remoteness proved useful to the Nazis as a refuge for items looted from across ]. When the ] ] occupied South Tyrol from May 2 to May 8, 1945, and after the total unconditional surrender of Germany on May 8, 1945, it found vast amounts of precious items and ] treasures. Among the items reportedly found were railway wagons filled with gold bars, hundreds of thousands of metres of silk, the Italian crown jewels, King Victor Emmanuel's personal collection of rare coins, and scores of works of art looted from art galleries such as the ] in ]. It was feared that the Germans might use the region, along with other Nazi-owned territories to make a last-ditch stronghold in the Alps to fight to the bitter end, and from there direct ] activities in Allied-controlled territories, but this did not occur due to the suicide of Hitler, the disintegration and chaos of the Nazi apparatus and the rapid Nazi German surrender thereafter.<ref>'']'', London, 25 May 1945</ref> | ||

| ==After World War II== | ==After World War II== | ||

| === First Austrian - Italian agreement === | |||

| After World War II and despite the harsh German occupation of Italy, the Province of Bolzano was untouched by the ] which occurred in all Europe, including former Nazi allies such as Hungary and Romania and western countries such as France and Netherlands. | |||

| ===First Austrian-Italian agreement=== | |||

| No one of remaining ''Optanen'' (the greater part) was forced to leave. On the contrary, Italy allowed several ''Optanten'' to came back. | |||

| ] | |||

| Attempts of the restored Republic of Austria, to regain the German lands of "Venezia Tridentina" came to nothing. | |||

| In 1945 the ] (Südtiroler Volkspartei) was founded, |

In 1945 the ] (''Südtiroler Volkspartei'') was founded, mainly by ''Dableiber'', who had elected to stay in Italy after the agreement between Hitler and Mussolini. | ||

| The support of the ''Dableiber'' proved useful as a means of deflecting ]n claims. | |||

| As the Allies had decided that the province should remain a part of ], Italy and ] negotiated an agreement in 1946, recognizing the rights of the German minority. This led to the creation of the ''Trentino-Alto Adige/Tiroler Etschland'' region, a new name for "Venezia Tridentina". German and Italian were both made official languages, and German-language education was permitted. But as the Italians were the majority in the region, self-government of the German minority was impossible. | |||

| In ], Italy and Austria accepted a compromise solution, the ]-] ], so named after the Austrian minister for foreign affairs and the Italian prime minister. The German-speaking people were granted special rights. | |||

| Together with the arrival of new Italian-speaking migrants, this led to strong dissatisfaction among South Tyroleans, which culminated in terrorist acts perpetrated by the ''Befreiungsausschuss Südtirol'' (BAS–Committee for the liberation of South Tyrol). In a first phase only public buildings and fascist monuments were targeted. One of the most notable attacks was the ], when the ] destroyed a number of electricity pylons. The second phase was bloodier, costing 21 lives (among them four activists and 15 Italian policemen and soldiers), four of them during a BAS ambush at Cima Vallona, province of ], on 25 June 1967.<ref>''The Economist'', Volume '''224''', issues ''6467-6470'', 1967. Economist Newspaper Ltd., p. 485</ref> | |||

| A special "Autonomy Statute" was granted by the new ] to region "Trentino-Alto Adige" (the new name of "Venezia Tridentina"). | |||

| Thus, in this region Italian speakers were in the majority, so a proper self-government for the German speakers was made harder. Not all what was granted was fully and quickly implemented; the total implementation of this "First statutory order" was delayed repeatedly. | |||

| The South Tyrolean question (''Südtirolfrage'') became an international issue. As the implementation of the post-war agreement was not seen as satisfactory by the Austrian government, the matter became the cause of significant friction with Italy and was taken up by the ] in 1960. A fresh round of negotiations took place in 1961 but this proved unsuccessful. | |||

| === The second agreement === | |||

| Eventually, international (especially Austrian) public opinion and domestic consideration led the Italian central government to consider a "Second statutory order" and to negotiate a "package" of reforms that produced the an "Autonomy Statute", that virtually delinked the mostly German speaking province of Bolzano from the Trentino. The new agreement was signed in 1969 by ] for Austria and by ] for Italy. It took further 20 years of reforms to be fully implemented. | |||

| In 1992 Italian government of Rome emanates the last previewed norms to implement the Package. After a debate in Parliament, also Vienna declares sluice the dispute. In June 18, 1992 the releasing receipt signed was signed by Italian and Austria in New York, in front of the U.N.<ref></ref> | |||

| ===The second agreement=== | |||

| ==Today== | |||

| Eventually, international (especially Austrian) public opinion and domestic considerations led the Italian government to consider a "Second statutory order" and to negotiate a package of reforms that produced the "Autonomy Statute", which virtually delinked the mostly German-speaking province of South Tyrol from the Trentino. The new agreement was signed in 1969 by ] for Austria and by ] for Italy. It stipulated that disputes in South Tyrol would be submitted for settlement to the ] in ], that the province would receive greater autonomy within Italy, and that Austria would not interfere in ] internal affairs. The agreement proved broadly satisfactory and the separatist tensions soon eased. | |||

| ] | |||

| Today, Alto Adige/South Tyrol is a peaceful and rich land, which enjoys a high degree of autonomy. | |||

| It has deep relations with ], especially since ]'s 1995 entry into the ], which led to a common currency and a ''de facto'' disappearance of the borders. | |||

| The new autonomous status, granted from 1972 onwards, has resulted in a considerable level of self-government, also due to the large financial resources of the province of Bolzano/Bozen, retaining almost 90% of all levied taxes.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| The whole historic region ] (] (North and East Tyrol) and ]) forms an ], a region of intensified cross-border cooperation within the EU, called "Tirol-Südtirol/Alto Adige-Trentino" which, albeit having only limited competences, led to a joint Tyrolean parliament . | |||

| | title = The South Tyrol Autonomy. A Short Introduction | |||

| | author = Anthony Alcock | |||

| | url = http://www.provincia.bz.it/lpa/autonomy/South-Tyrol%20Autonomy.pdf | |||

| | access-date = 2007-11-14}}{{Dead link | date = October 2010 | bot = H3llBot}}</ref> | |||

| It took a further 20 years for the reforms to be fully implemented, the last in 1992. After a debate in Parliament, Vienna declared the dispute closed. On June 18, 1992 the release was signed by Italy and Austria in New York, in front of the United Nations building.<ref name="Ref_h"></ref> | |||

| Today, South Tyrol is peaceful and the wealthiest Italian province, enjoying a high degree of autonomy. It has strong relations with the Austrian state of Tyrol, especially since Austria's 1995 entry into the ], which has led to a common currency and a de facto disappearance of the borders. | |||

| == Linguistic and demographic history == | |||

| At the time of its annexation, the territory subsequently known as ] was inhabited by a large ]-speaking majority. According to the ] of ], which listed four groups according to their spoken language, the area was inhabited by approximately 89% ], 3.8% ], 2.9% ], and 4.3% speakers of other languages of the Austrian empire, altogether 251,000 people.<ref name="Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol">Oscar Benvenuto (ed.): ", Bozen/Bolzano 2007, p. 19, Table 11</ref> According to some sources, the census did not include some 9000 immigrants from Italy.<ref> Italians non included in 1910 census</ref> However, from the official provincial statistics of the ''Autonomous Province of South Tyrol'' it appears that Italian citizens were indeed registered in the census, although not necessarily as Italian-speakers.<ref name="Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol"/> | |||

| The whole historic region of Tyrol, comprising the Austrian state of Tyrol and the Italian Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, forms a ], a region of intensified cross-border cooperation within the EU, called "Tyrol-South Tyrol-Trentino", and a joint Tyrolean parliament has been established, albeit with limited powers. | |||

| In the following, the resident population is listed by language group, according to the censuses undertaken from 1880 to 2001. In absolute numbers:<ref name="Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol"/> | |||

| ==Linguistic and demographic history== | |||

| {| class="prettytable sortable" | |||

| At the time of its annexation, ] was inhabited by a large ]-speaking majority. According to the census of 1910, which listed four groups according to their spoken language, the area was inhabited by approximately 89% ], 3.8% ], 2.9% ], and 4.3% speakers of other languages of the Austrian Empire, altogether 251,000 people.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | last = Benvenuto | |||

| | first = Oscar | |||

| | title = South Tyrol in Figures 2008 | |||

| | work = Bozen/Bolzano 2007, p. 19, Table 11 | |||

| | publisher = Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol | |||

| | date = June 8, 2006 | |||

| | url = http://www.provinz.bz.it/Astat/downloads/Siz_2008-eng.pdf | |||

| | access-date = 2009-02-21}}</ref> According to some sources, the census did not include some 9000 immigrants from Italy.<ref name="Ref_i"> The Italians were not included</ref> However, from the official provincial statistics of the "Autonomous Province of South Tyrol" it appears that Italian citizens were indeed registered in the census, although not necessarily as Italian speakers.<ref name="Ref_">Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol"</ref> | |||

| In the following, the population is listed by language group, according to the censuses undertaken from 1880 to 2001. In absolute numbers:<ref name="Ref_" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" | |||

| |- class="hintergrundfarbe6" | |- class="hintergrundfarbe6" | ||

| ! Year !! German !! Italian !! Ladin !! Others !! Total !! Country | ! Year !! German !! Italian !! Ladin !! Others !! Total !! Country | ||

| Line 163: | Line 164: | ||

| |{{Sort|006884|{{0|12}}6,884}} | |{{Sort|006884|{{0|12}}6,884}} | ||

| |{{Sort|008822|{{0|12}}8,822}} | |{{Sort|008822|{{0|12}}8,822}} | ||

| |{{Sort|003513|{{0|12}}3,513}} |

|{{Sort|003513|{{0|12}}3,513}}<ref name="Censuses 1880, 1890, 1900">"Locals" with a different commonly spoken language and "non locals"</ref> | ||

| |205,306 | |205,306 | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1890 | |1890 | ||

| Line 171: | Line 172: | ||

| |{{Sort|009369|{{0|12}}9,369}} | |{{Sort|009369|{{0|12}}9,369}} | ||

| |{{Sort|008954|{{0|12}}8,954}} | |{{Sort|008954|{{0|12}}8,954}} | ||

| |{{Sort|004862|{{0|12}}6,884}} |

|{{Sort|004862|{{0|12}}6,884}}<ref name="Censuses 1880, 1890, 1900"/> | ||

| |210,285 | |210,285 | ||

| |Austria-Hungary | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1900 | |1900 | ||

| Line 179: | Line 180: | ||

| |{{Sort|008916|{{0|12}}8,916}} | |{{Sort|008916|{{0|12}}8,916}} | ||

| |{{Sort|008907|{{0|12}}8,907}} | |{{Sort|008907|{{0|12}}8,907}} | ||

| |{{Sort|007149|{{0|12}}7,149}} |

|{{Sort|007149|{{0|12}}7,149}}<ref name="Censuses 1880, 1890, 1900"/> | ||

| |222,794 | |222,794 | ||

| |Austria-Hungary | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1910 | |1910 | ||

| Line 187: | Line 188: | ||

| |{{Sort|007339|{{0|12}}7,339}} | |{{Sort|007339|{{0|12}}7,339}} | ||

| |{{Sort|009429|{{0|12}}9,429}} | |{{Sort|009429|{{0|12}}9,429}} | ||

| |{{Sort|010770|{{0|1}}10,770}} |

|{{Sort|010770|{{0|1}}10,770}}<ref name="Census 1910">"Italian citizens with a different commonly spoken language and non Italian citizens"</ref> | ||

| |251,451 | |251,451 | ||

| |Austria-Hungary | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1921 | |1921 | ||

| Line 195: | Line 196: | ||

| |{{Sort|027048|{{0|1}}27,048}} | |{{Sort|027048|{{0|1}}27,048}} | ||

| |{{Sort|009910|{{0|12}}9,910}} | |{{Sort|009910|{{0|12}}9,910}} | ||

| |{{Sort|024506|{{0|1}}24,506}} |

|{{Sort|024506|{{0|1}}24,506}}<ref name="Census 1921">"Foreigners"</ref> | ||

| |254,735 | |254,735 | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| Line 203: | Line 204: | ||

| |{{Sort|128271|128,271}} | |{{Sort|128271|128,271}} | ||

| |{{Sort|012594|{{0|2}}12,594}} | |{{Sort|012594|{{0|2}}12,594}} | ||

| |{{Sort|000281|{{0|123,}}281}} |

|{{Sort|000281|{{0|123,}}281}}<ref name="Census 1961">"All residents with a different commonly spoken language"</ref> | ||

| |373,863 | |373,863 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1971 | |1971 | ||

| Line 211: | Line 212: | ||

| |{{Sort|137759|137,759}} | |{{Sort|137759|137,759}} | ||

| |{{Sort|015456|{{0|1}}15,456}} | |{{Sort|015456|{{0|1}}15,456}} | ||

| |{{Sort|000475|{{0|123,}}475}} |

|{{Sort|000475|{{0|123,}}475}}<ref name="Census 1971">"All residents who did not declare which language group they belonged to"</ref> | ||

| |414,041 | |414,041 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1981 | |1981 | ||

| Line 219: | Line 220: | ||

| |{{Sort|123695|123,695}} | |{{Sort|123695|123,695}} | ||

| |{{Sort|017736|{{0|1}}17,736}} | |{{Sort|017736|{{0|1}}17,736}} | ||

| |{{Sort|009593|{{0|12}}9,593}} |

|{{Sort|009593|{{0|12}}9,593}}<ref name="Census 1981">"Resident Italian citizens without any valid language group declaration, and resident foreigners"</ref> | ||

| |430,568 | |430,568 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1991 | |1991 | ||

| Line 227: | Line 228: | ||

| |{{Sort|116914|116,914}} | |{{Sort|116914|116,914}} | ||

| |{{Sort|018434|{{0|1}}18,434}} | |{{Sort|018434|{{0|1}}18,434}} | ||

| |{{Sort|017657|{{0|1}}17,657}} |

|{{Sort|017657|{{0|1}}17,657}}<ref name="Censuses 1991, 2001">"Invalid declarations, people temporarily absent and resident foreigners"</ref> | ||

| |440,508 | |440,508 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |2001 | |2001 | ||

| Line 235: | Line 236: | ||

| |{{Sort|113494|113,494}} | |{{Sort|113494|113,494}} | ||

| |{{Sort|018736|{{0|1}}18,736}} | |{{Sort|018736|{{0|1}}18,736}} | ||

| |{{Sort|034308|{{0|1}}34,308}} |

|{{Sort|034308|{{0|1}}34,308}}<ref name="Censuses 1991, 2001"/> | ||

| |462,999 | |462,999 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |||

| |2011 | |||

| |314,604 | |||

| |{{Sort|118120|118,120}} | |||

| |{{Sort|020548|{{0|1}}20,548}} | |||

| |{{Sort|058478|{{0|1}}58,478}}<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | title = astat info Nr. 38 | |||

| | work = Table 1 — Declarations of which language group belong to/affiliated to — Population Census 2011 | |||

| | url = http://www.provinz.bz.it/astat/de/service/256.asp?news_action=300&news_image_id=562996 | |||

| |format = PDF | |||

| | access-date = 2012-06-12}}</ref> | |||

| |511,750 | |||

| |Italy | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |2024 | |||

| |309,000 | |||

| |{{Sort|121520|121,520}} | |||

| |{{Sort|019853|{{0|1}}19,853}} | |||

| |{{Sort|086560|{{0|1}}86,560}}<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | title = astat Jahrbuch 2024 | |||

| | work = 03 Bevölkerung | |||

| | url = https://astat.provinz.bz.it/downloads/JB2024_K3.pdf | |||

| |format = PDF | |||

| | access-date = 2024-12-23}}</ref> | |||

| |511,750 | |||

| |Italy | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| In percentages:<ref name="Ref_j">Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" | |||

| In percentages:<ref name="Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol"/> | |||

| {| class="prettytable sortable" | |||

| |- class="hintergrundfarbe6" | |- class="hintergrundfarbe6" | ||

| ! Year !! German !! Italian !! Ladin !! Others !! Total !! Country | ! Year !! German !! Italian !! Ladin !! Others !! Total !! Country | ||

| Line 251: | Line 275: | ||

| |{{Sort|034|{{0|1}}3.4}} | |{{Sort|034|{{0|1}}3.4}} | ||

| |4.3 | |4.3 | ||

| |1.7 |

|1.7<ref name="Censuses 1880, 1890, 1900"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| |Austria-Hungary | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1890 | |1890 | ||

| Line 259: | Line 283: | ||

| |{{Sort|045|{{0|1}}4.5}} | |{{Sort|045|{{0|1}}4.5}} | ||

| |4.3 | |4.3 | ||

| |2.3 |

|2.3<ref name="Censuses 1880, 1890, 1900"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| |Austria-Hungary | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1900 | |1900 | ||

| Line 267: | Line 291: | ||

| |{{Sort|040|{{0|1}}4.0}} | |{{Sort|040|{{0|1}}4.0}} | ||

| |4.0 | |4.0 | ||

| |3.2 |

|3.2<ref name="Censuses 1880, 1890, 1900"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| |Austria-Hungary | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1910 | |1910 | ||

| Line 275: | Line 299: | ||

| |{{Sort|029|{{0|1}}2.9}} | |{{Sort|029|{{0|1}}2.9}} | ||

| |3.8 | |3.8 | ||

| |4.3 |

|4.3<ref name="Census 1910"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| |Austria-Hungary | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1921 | |1921 | ||

| Line 283: | Line 307: | ||

| |{{Sort|106|10.6}} | |{{Sort|106|10.6}} | ||

| |3.9 | |3.9 | ||

| |9.6 |

|9.6<ref name="Census 1921"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| Line 291: | Line 315: | ||

| |{{Sort|343|34.3}} | |{{Sort|343|34.3}} | ||

| |3.4 | |3.4 | ||

| |0.1 |

|0.1<ref name="Census 1961"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1971 | |1971 | ||

| Line 299: | Line 323: | ||

| |{{Sort|333|33.3}} | |{{Sort|333|33.3}} | ||

| |3.7 | |3.7 | ||

| |0.1 |

|0.1<ref name="Census 1971"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1981 | |1981 | ||

| Line 307: | Line 331: | ||

| |{{Sort|287|28.7}} | |{{Sort|287|28.7}} | ||

| |4.1 | |4.1 | ||

| |2.2 |

|2.2<ref name="Census 1981"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |1991 | |1991 | ||

| Line 315: | Line 339: | ||

| |{{Sort|265|26.5}} | |{{Sort|265|26.5}} | ||

| |4.2 | |4.2 | ||

| |4.0 |

|4.0<ref name="Censuses 1991, 2001"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |2001 | |2001 | ||

| Line 323: | Line 347: | ||

| |{{Sort|245|24.5}} | |{{Sort|245|24.5}} | ||

| |4.0 | |4.0 | ||

| |7.4 |

|7.4<ref name="Censuses 1991, 2001"/> | ||

| |100.0 | |100.0 | ||

| | |

|Italy | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| |2011 | |||

| |61.5 | |||

| |{{Sort|231|23.1}} | |||

| |4.0 | |||

| |11.4 | |||

| |100.0 | |||

| |Italy | |||

| |- | |||

| |2024 | |||

| |57.6 | |||

| |{{Sort|226|22.6}} | |||

| |3.7 | |||

| |16.1 | |||

| |100.0 | |||

| |Italy | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ==Secessionist movement== | |||

| {{Main|South Tyrolean secessionist movement}} | |||

| Given the region's historical and cultural association with neighboring Austria, calls for the secession of South Tyrol and its reunification with Austria are notable in the local and national political climate. Polls conducted in 2013 noted that 46% of South Tyrol's population would favor secession from Italy.<ref name=nat>{{Cite web | title = South Tyrol heading to unofficial independence referendum in autumn | url = http://www.nationalia.info/en/news/1508 | work = 7 March 2013 | publisher = Nationalia.info | access-date = 28 March 2014}}</ref> Among the political parties that support South Tyrol's reunification into Austria are ], ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web | title = Website of South Tyrolean Freedom | url = http://www.suedtiroler-freiheit.com | access-date = 28 March 2014}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes and references== | ==Notes and references== | ||

| {{Reflist|2}} | {{Reflist|2}} | ||

| == |

==Bibliography== | ||

| * {{cite book | |||

| * ] | |||

| |author= Paula Sutter Fichtner | |||

| |title=Historical Dictionary of Austria|year=2009 | |||

| |publisher=] |location=USA |isbn=978-0-8108-6310-1 |chapter-url= https://books.google.com/books?id=ilyK1_1f0zYC&pg=PR25 | |||

| |chapter= South Tyrol |pages= 282+ | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |author= Georg Grote, Hannes Obermair | |||

| |title=A Land on the Threshold. South Tyrolean Transformations, 1915–2015 | |||

| |year=2017 | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |location=Oxford, Bern, New York|isbn=978-3-0343-2240-9 | |||

| |url= https://peterlangoxford.wordpress.com/2017/05/12/a-land-on-the-threshold-published/ | |||

| |pages= 417+ | |||

| }} | |||

| * {{cite book | |||

| |author=Giovanni Bernardini, Günther Pallaver | |||

| |title=Dialogue against Violence. The Question of Trentino-South Tyrol in the International Context | |||

| |year=2017 | |||

| |publisher=Il Mulino - Duncker & Humblot | |||

| |location=Bologna, Berlin | |||

| |isbn=978-88-15-27340-6 | |||

| |url=http://www.duncker-humblot.de/index.php/dialogue-against-violence.html?q=bernardini | |||

| |pages=256+ | |||

| }}{{Dead link|date=August 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commons category-inline}} | |||

| * {{Cite web | url = http://www.suedtirol.info/en/Plan-Your-Trip/South-Tyrol--Its-People/History.html | title = South Tyrol/Südtirol—History of Tyrol & the Dolomites | access-date = 2009-02-21 | work = South Tyrol Information | year = 2009 | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120815011644/http://www.suedtirol.info/en/Plan-Your-Trip/South-Tyrol--Its-People/History.html | archive-date = 2012-08-15 }} | |||

| * County Londonderry/Bozen-Bolzano, May 2001. Retrieved on 2009-03-16. | |||

| {{German diaspora}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:50, 23 December 2024

Tyrol (state) (Austria) South Tyrol (Italy) Trentino (Italy) Parts of the former county now within other Italian provinces

Modern-day South Tyrol, an autonomous Italian province created in 1948, was part of the Austro-Hungarian County of Tyrol until 1918 (then known as Deutschsüdtirol and occasionally Mitteltirol). It was annexed by Italy following the defeat of the Central Powers in World War I. It has been part of a cross-border joint entity, the Euroregion Tyrol-South Tyrol-Trentino, since 2001.

Before the 19th century

Main article: History of TyrolAntiquity

In 15 BC the region, inhabited by the Alpine population of the Raeti, was conquered by the Roman commanders Drusus and Tiberius, and its northern and eastern parts were incorporated into the provinces of Raetia and Noricum respectively, while the southern part including the lower Adige and Eisack valleys around the modern-day city of Bolzano up to present-day Merano and Waidbruck (Sublavio) became part of Roman Italy (Italia), Regio X Venetia et Histria. The mountainous area then mainly was a transit country along Roman roads crossing the Eastern Alps like the Via Claudia Augusta, settled by Romanised Illyrian and Raeti tribes which had adopted the Vulgar Latin (Ladin) language.

Middle Ages

After the conquest of Italy by the Goths in 493, Tyrol became part of the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy in the 5th and the 6th centuries. Already in 534 the western Vinschgau region fell to the Kingdom of the Franks (Alamannia), while after the final collapse of the Ostrogothic Kingdom in 553 West Germanic Bavarians entered the region from the north. When the Lombards invaded Italy in 568 and founded the Kingdom of Italy, it also included the Duchy of Tridentum with the southernmost part of Tyrol. The border with the German stem duchy of Bavaria ran southwest of present-day Bolzano along the Adige River, with Salorno and the right bank (including Eppan, Kaltern and the area up to Lana on the Falschauer River) belonging to the Lombard kingdom. While the boundary remained unchanged for centuries, Bavarian settlers further migrated southwards down to Salorno (Salurn). The population was Christianised by the Bishops of Brixen and Trento.

In 1027 Emperor Conrad II established the Prince-bishopric of Trent in order to secure the route up to the Brenner Pass. He ceded the counties of Trento, Bolzano and Vinschgau to the Trent bishops and finally separated the territory on the east bank of the Adige River down to Mezzocorona (Deutschmetz) from the Imperial Kingdom of Italy. The Gau of Norital, including the Wipptal, the Eisacktal and the Val Badia, was granted to the newly established Prince-Bishopric of Brixen, followed in 1091 by the Puster Valley. Over the centuries, the episcopal reeves (Vögte) residing at Tirol Castle near Merano extended their territory over much of the region and came to surpass the power of the bishops who were nominally their feudal lords. The later Counts of Tyrol reached independence from the Duchy of Bavaria during the deposition of Duke Henry the Lion in 1180. Also in this period, from the late twelfth to the thirteenth centuries, have been established along the Brenner axis almost all of up-today's existing urban settlements, which can be categorized as marked-formed, not very densely populated small-towns, such as Bolzano, Merano, Sterzing or Bruneck.

Modern Age

From the 13th century they held much of their territory immediate from the Holy Roman Emperor and were elevated to Princes of the Holy Roman Empire in 1504.

Following defeat by Napoleon in 1805, the Austrian Empire was forced to cede the northern part of Tyrol to the Kingdom of Bavaria in the Peace of Pressburg. It became a member of the Confederation of the Rhine in 1806. Tyrol remained split between Bavaria and the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy until it was returned to Austria by the Congress of Vienna in 1814. Integrated into the Austrian Empire, from 1867 it was a Kronland (Crown Land) of Cisleithania, the western half of Austria-Hungary.

Age of nationalism

Further information: Italian irredentism

After the Napoleonic Era, nationalism emerged as the dominant ideology in Europe. In Italy several intellectuals and groups began to push the idea of a unified nation-state (see Risorgimento). At the time, the struggle for Italian unification was largely waged against the Austrian Empire, which was the hegemonic power in Italy and the single most powerful adversary to unification. The Austrian Empire vigorously repressed the growing nationalist sentiment among Italian elites, most of all during 1848 revolution and the following years. Italy finally attained independence in 1861, annexed Venetia in 1866, and Latium, including Rome, in 1870.

However, for many nationalist intellectuals and political leaders, the process of unification of the Italian peninsula under a single national state was not complete. This was because several areas inhabited by Italian-speaking communities remained under what was seen as foreign rule. This situation gave rise to the idea that parts of Italy were still unredeemed, hence Italian irredentism became an important ideological component of the political life of the Kingdom of Italy: see Italia irredenta.

In 1882 Italy signed a defensive alliance with Austria-Hungary and Germany (see Triple Alliance). However, Italian public opinion remained unenthusiastic about the alignment with Austria-Hungary, still perceiving it as the historical enemy of Italy. In the years before World War I, many distinguished military analysts predicted that Italy would change sides.

Italy declared its neutrality at the beginning of World War I, because the Triple Alliance was a defensive one, requiring its members to come under attack to come into effect. Many Italians were still hostile to Austrian historical and continuing occupation of ethnically Italian areas. Austria-Hungary requested Italian neutrality, while the Triple Entente (Great Britain, France and Russia) demanded its intervention. Many people in Italy wanted the country to join the conflict on the side of the Triple Entente, with the aim of gaining the "unredeemed" territories.

Under the secret Treaty of London, signed in April 1915, Italy agreed to declare war against the Central Powers in exchange for (among other things) territorial gains in the Austrian crown lands of Tyrol, Küstenland and Dalmatia, homeland of large Italian minorities. War against the Austro-Hungarian Empire was declared on May 24, 1915.

In October 1917, the Italian army was defeated in the Battle of Caporetto, and was forced back to a defensive line along the Piave river. In June 1918, an Austro-Hungarian offensive against the Piave line was repulsed (see Battle of the Piave River). On October 24, 1918, Italy launched its final offensive against the Austro-Hungarian Army, which consequently collapsed (see Battle of Vittorio Veneto). The armistice of Villa Giusti was signed on November 3. It came into force at 3.00 pm on November 4. In the following days the Italian Army completed the occupation of all Tirol (including Innsbruck), according to the armistice terms.

Annexation by Italy

Under the secret Treaty of London (1915), Italy "shall obtain the Trentino, Cisalpine Tyrol with its geographical and natural frontier (the Brenner frontier)" and after the ceasefire of Villa Giusti (November 3, 1918) Italian troops occupied uncontested the territory and as stipulated in the ceasefire agreement marched into North Tyrol and occupied Innsbruck and the Inn valley.

During the negotiations between Austria and the victorious Entente powers in Saint-Germain a petition for help, signed by all the mayors of South Tyrol, was presented to US President Woodrow Wilson. Wilson had announced his Fourteen Points to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918, and the mayors reminded him of point 9:

"A readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality."

But when the Treaty of Saint-Germain was signed on September 10, 1919, Italy was given by Article 27, section 2 the ethnic German territories south of the Alpine watershed.

It has been claimed that Wilson later complained about the annexation:

"Already the president had, unfortunately, promised the Brenner Pass boundary to Orlando, which gave to Italy some 150,000 Tyrolese Germans-an action which he subsequently regarded as a big mistake and deeply regretted. It had been before he had made a careful study of the subject...."

As Italy had not yet adopted the toponymy created by Ettore Tolomei, all the names of locations in the treaty, except the Adige river, were in German (the same monolingual German approach to local names as in the Treaty of London).

At first, the territory was governed by a military regime under General Guglielmo Pecori-Giraldi, directly subordinated to the Comando Supremo. One of the first orders was to seal the border between South Tyrol and Austria. People were not allowed to cross, and the postal service and the flow of goods were interrupted; censorship was introduced and officials not born in the area were dismissed. On November 11, 1919, General Pecori-Giraldi proclaimed in the name of King Victor Emmanuel III in Italian and German: "... Italy is willing, as sole united nation with full freedom of thought and expression, to allow nationals of other language the preservation of their own schools, private institutions and associations." On December 1, 1919 the King promised in a speech: "a careful maintenance of local institutions and self-administration"

Italy formally annexed the territories on October 10, 1920. The administration passed from the military to the new Governatorato della Venezia Tridentina (Governorate of Venezia Tridentina) under Luigi Credaro. The term Venezia Tridentina had been proposed in 1863 by the Jewish linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli from Gorizia, who sought to include all of the territories of the Austro-Hungarian Empire claimed by Italy into a wider region called Venezia (the Julian March was accordingly named Venezia Giulia). The Governatorato included the present-day region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol and the three Ladin communes of Cortina, Colle Santa Lucia and Livinallongo, today in the Province of Belluno. The northern part of Tyrol, comprising North Tyrol and East Tyrol, became what is today one of the nine federal states of Austria.

On January 21, 1921, the Governatorato, while retaining military and police control, ceded administrative control to the new provincial council of the Provincia di Venezia Tridentina in Trento. On May 15, 1921, the people of the area participated for the first (and until April 18, 1948, the only) free and democratic elections (the people of Venezia Tridentina and Venezia Giulia did not participate in the general election of June 2, 1946). The result was a resounding victory for the Deutscher Verband (German Association), which won close to 90% of the votes and thus sent four deputies to Rome.

Rise of fascism

Up to this time, the German-speaking population had not been subjected to violence and nor had the Italian authorities interfered with its cultural activities, traditions and schooling. This was about to change with the rise of fascism. The first hint of what was to come was experienced by the German population on Sunday April 24, 1921. The population of Bolzano-Bozen had organized a Trachtenumzug (a procession in traditional local costume) to celebrate the opening of the spring trade fair. The General Civil Commissioner of the province, Luigi Credaro, had been warned in advance by his colleagues from Mantua, Brescia, Verona and Vicenza of the intention of the fascists there to go to Bolzano-Bozen to disrupt the procession, but did not take any precautions. After arriving by train in Bolzano-Bozen the approximately 280 out-of-province fascists were joined by about 120 from Bolzano-Bozen, and proceeded to attack the procession with clubs, pistols and hand grenades. The teacher Franz Innerhofer from Marling was shot dead and around 50 people injured in the attack. After the attack the military intervened and escorted the fascists back to the station. Although Credaro, under orders from the Italian Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti, had two suspects in Innerhofer's murder arrested, nobody was brought to justice for the attack, as Benito Mussolini had threatened to come to Bolzano-Bozen with 2,000 fascists to free the two suspects by force if they were not set free immediately. Mussolini made clear his policies regarding the people of South Tyrol:

"If the Germans on both sides of the Brenner don't toe the line, then the fascists will teach them a thing or two about obedience. Alto Adige is Italian and bilingual, and no one would even dream of trying forcibly to Italianize these German immigrants. But neither may Germans imagine that they might push Italy back to Salorno and from there to the Lago di Garda. Perhaps the Germans believe that all Italians are like Credaro. If they do, they’re sorely mistaken. In Italy, there are hundreds of thousands of Fascists who would rather lay waste to Alto Adige than to permit the tricolore that flies above the Vetta d’Italia to be lowered. If the Germans have to be beaten and stomped to bring them to reason, then so be it, we’re ready. A lot of Italians have been trained in this business."

Italianization

Main article: Italianization of South Tyrol

In October 1922, the new Fascist government rescinded all the special dispensations that protected linguistic minorities.

The Italianization program had been started, and the Fascist regime charged Achille Starace and Ettore Tolomei (a nationalist from Rovereto) to drive it.

Tolomei's "program in 23 points" was adopted. Among other things it decreed:

- exclusive use of Italian in the public offices;

- closure of the majority of the German schools;

- incentives for immigrants from other Italian regions.

The first forms of opposition to the regime appeared in 1925: a priest, Michael Gamper, opened the first "Katakombenschulen", clandestine schools where teachers taught in German.

In 1926 the ancient institution of communal autonomy was abolished. Throughout Italy the "podestà", appointed by the government, replaced the mayors and had to report to the "prefetti".

A large industrial zone in Bolzano opened in 1935. It was followed by the immigration of many workers and their families from other parts of Italy (mainly from Veneto).

In this period of oppression, National Socialist propaganda became more and more successful among young South Tyroleans, leading in 1934 to the formation of the illegal local Nazi organization of the Völkischer Kampfring Südtirols (VKS).

German-Italian option agreement

Main article: South Tyrol Option AgreementAdolf Hitler never claimed any part of the Southern Tyrol for his Third Reich, even before the alliance with Benito Mussolini; in fact in Mein Kampf (1924) he claimed that Germans were just a small and irrelevant minority in Southern Tyrol (this definition including also Trentino) and he acknowledged the German portion of Southern Tyrol as a permanent possession of Italy. Hitler writes in Book II of Mein Kampf, "But I do not hesitate to declare that, now the dice have fallen, I not only regard a reconquest of the South Tyrol by war as impossible, but that I personally would reject it in the conviction that for this question the flame of national enthusiasm of the whole German people could not be achieved to a degree which would offer the premise for victory."

In 1939, both dictators in order to solve any further dispute agreed to give the German-speaking population a choice in the South Tyrol Option Agreement: they could emigrate to neighbouring Germany (including annexed Austria) or stay in Italy and accept complete Italianisation.

The South Tyrolean population was deeply divided. Those who wanted to stay (Dableiber) were condemned as traitors; those who left (Optanten), the majority, were defamed as Nazis. There was a plan to relocate the Optanten in Crimea (annexed to Greater Germany), but most were resettled in German-annexed Western Poland, where they were expelled or killed after the war. Because of the outbreak of World War II, this agreement was only partially carried out.

In 1939 Mussolini decided to build an Alpine Wall, a military fortification to defend Italy's northern land border.

Annexation by Nazi Germany