| Revision as of 01:49, 2 February 2009 editImbris (talk | contribs)3,915 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:59, 6 November 2024 edit undoJoy (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators143,976 editsm link term (WP:BUILDTHEWEB) | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Breed of toy dog}} | |||

| {{Infobox Dogbreed | |||

| {{Other uses|Maltese (disambiguation){{!}}Maltese}} | |||

| | akcgroup = Toy group | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=February 2023}} | |||

| | akcstd = http://www.akc.org/breeds/maltese/index.cfm | |||

| {{Infobox dog breed | |||

| | altname = Bichon Maltaise,</br>Ye Ancient Dogge of Malta,</br>{{Lang-hr|Mljetski psić}} <ref> '''''by Gino Pugnetti''''' ''and translated by Elizabeth Meriwether Schuler, published by Simon and Schuster, 1980,'' ISBN 0671255274, ISBN 9780671255275, '''Yugoslavian issue in 1983''' edited by Ratimir Orban M.Sci.Dr.vet.med.</ref> | |||

| | name = Maltese | |||

| | ankcgroup = Group 1 (Toys) | |||

| | image = Maltese 600.jpg | |||

| | ankcstd = http://www.ankc.org.au/home/breeds_details.asp?bid=19 | |||

| | image_caption = Maltese groomed with overcoat | |||

| | ckcgroup = Group 5 - Toys | |||

| | country = Italy{{sfn|AISBL|2015}} | |||

| | ckcstd = http://www.ckc.ca/Default.aspx?tabid=73&Breed_Code=MLE | |||

| | weight = {{right|{{convert|3|–|4|kg|abbr=on|0}}{{sfn|AISBL|2015}}}} | |||

| | country = Central Mediterranean Area <ref name="FCI"> translated by Peggy Davis, owned by Yvonne Soomers-Marell (scroll to the bottom)</ref> | |||

| | maleweight = | |||

| | patronage = {{flagicon|ITA}} ] <ref name="FCI"></ref> | |||

| | femaleweight = | |||

| |dogbreedinfo.com fcigroup = 9 | |||

| | maleheight = {{right|{{convert|21|–|25|cm|abbr=on|0}}{{sfn|AISBL|2015}}}} | |||

| | fcinum = 65 | |||

| | femaleheight = {{right|{{convert|20|–|23|cm|abbr=on|0}}{{sfn|AISBL|2015}}}} | |||

| | fcisection = 1 | |||

| | coat = white | |||

| | fcistd = http://www.google.com/search?q=cache:www.fci.be/uploaded_files/065gb98_en.doc | |||

| | litter_size = 1 to 3 | |||

| | image = Maltese.jpg | |||

| | life_span = | |||

| | image_caption = A Maltese with a "Puppy Cut" | |||

| | kc_name = ] | |||

| | kcukgroup = Toy | |||

| | |

| kc_std = https://www.enci.it/media/2337/065.pdf | ||

| | fcistd = http://www.fci.be/Nomenclature/Standards/065g09-en.pdf | |||

| | name = Maltese | |||

| | nzkcgroup = Toy | |||

| | nzkcstd = http://www.nzkc.org.nz/br140.html | |||

| | ukcgroup = Companion Breeds | |||

| | ukcstd = http://mail.ukcdogs.com/UKCweb.nsf/80de88211ee3f2dc8525703f004ccb1e/747a9b18eb9ea6738525704400502284?OpenDocument | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| <!-- End Infobox Dogbreed info. Article Begins Here --> | |||

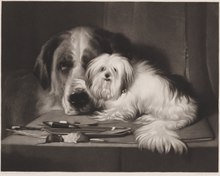

| ], 1844, from ] painting ''The Lion Dog of Malta'']] | |||

| A '''Maltese''' is a small ] of ] in the toy group. The Maltese does not shed and is covered with long, silky white fur. The Maltese breed of today is descended from dogs associated by name with the ] island of ] along the coast of ], the ] town of Melita, and the ] island of ].<ref name="FCI"></ref> It is one of the oldest dog breeds. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ==Description== | |||

| ===Appearance=== | |||

| Characteristics include slightly rounded skulls, with a one-finger-wide dome and a black nose that is two finger widths long. The body is compact with the length equaling the height. The drop ears with long hair and very dark eyes, surrounded by darker skin pigmentation (called a "halo"), gives Maltese their expressive look. Their noses can fade and become pink or light brown in color without exposure to sun light. This is often referred to as a "winter nose"<ref></ref> and many times will become black again with increased exposure to the sun. | |||

| '''Maltese dog''' refers both to an ancient variety of dwarf, white-coated dog breed from ]{{sfn|AISBL|2015}} and generally associated also with the island of ], and to a modern ] of similar dogs in the ], genetically related to the ], ], and ] breeds.{{sfn|Gorman|2021}} The precise link, if any, between the modern and ancient breeds is not known. Nicholas Cutillo suggested that Maltese dogs might descend from ], and that the ancient variety probably was similar to the latter ] with their short snout, pricked ears, and bulbous heads.{{sfn|Cutillo|1986|pp=190,199}}{{sfn|MacKinnon|Belanger|2006|p=43}} These two varieties, according to ], were perhaps the first dogs employed as human companions.{{sfn|Coren|2006|p=167}} | |||

| ==== Coat and color ==== | |||

| The ] is long and silky and lacks an ]. The color is pure white and although cream or light lemon ears are permissible, they are not desirable. | |||

| The modern variety traditionally has a silky, pure-white coat, hanging ears and a tail that curves over its back, and weighs up to {{convert|3|–|4|kg|lb|abbr=on|0}}.{{sfn|AISBL|2015}} The Maltese does not shed.{{sfn|Alderton|2010|p=59}} The Maltese is kept for ], ornament, or ]. | |||

| ====Size==== | |||

| ] | |||

| Adult Maltese range from roughly 3 to 7 lb (1.4 to 3.0 kg), though breed standards, as a whole, call for weights between 4 and 7 lb (1.8 to 3. kg). There are variations depending on which standard is being used; many, like the American Kennel Club, call for a weight that is ideally less than 7 lb with between 4 and 6 lb preferred. | |||

| == Maltese dogs in antiquity == | |||

| ===Temperament=== | |||

| The old variety of Maltese appears to have been the most common or favourite pet, or certainly household dog, in antiquity.{{efn|"small dogs were also kept as household pets. The commonest of these seems to be an animal resembling the Maltese, an animal with small upright ears and long hair." {{harv|Trantalidou|2006|p=107}}}}{{efn|"the favourite pet dog of antiquity seems to have been the Maltese." {{harv|Gosling|1935|p=100}}}}{{efn|"The commonest pet was the small white long-coated Maltese dog represented on 5th-cent. BC Attic vases and gravestones." {{harv|White|Hornblower|2012|p=1118}}}} Dogs of various sizes and shapes are depicted on vases and ]e.{{sfn|Moore|2008|p=16}} On one Attic amphora from about 500 BC, excavated at ] in the nineteenth century and now lost, an illustration of a small dog with a pointed muzzle is accompanied by the word μελιταῖε, ''melitaie''.{{sfn|Johnson|1919|p=211}} | |||

| ]<!-- the term "leaf litter" is a technical term used by terrestrial ecologists and biogeochemists. It is more specific and appropriate than "detritus". It is also easier to understand as "detritus" is merely technical jargon. Leaf litter = "dead, fallen leaves" Nothing to do with garbage/trash/rubbish. Note 2008-10-14: "A pile of leaves" is clearer and this is a dog article, not ecology. --> | |||

| Numerous references to these dogs are found in Ancient Greek and Roman literature.{{sfn|Busuttil|1969|pp=205–208}} Ancient writers variously attribute its origin either to the island of ] in the Mediterranean, called {{lang|la|Melita}} in Latin, – a name which derives from the Carthaginian city of that name on the island, ] – or to the ] island of ], near ] and off the ]n coast of modern ], also called Melita in Latin. The uncertainty continues, but recent scholarship generally supports the identification with Malta.{{sfn|Ogden|2007|p=197}} | |||

| For all their diminutive size, Maltese seem to be without fear. In fact, many Maltese seem indifferent to creatures and objects larger than themselves but can also be quite aggressive for their small size, which makes them very easy to socialize with other dogs, and even cats. They love time with owners. This is because they were bred to be companion dogs and thrive on love and attention. They are extremely lively and playful, and even as a Maltese ages, his or her energy level and playful demeanor remains fairly constant and does not diminish much. | |||

| In Greece in ] a variety of diminutive dog (νανούδιον/''nanoúdion'' -"dwarf dog"){{sfn|Busuttil|1969|p=205}} was called a Μελιταῖον κυνίδιον (''Melitaion kunídion'', "small dog from Melita"). In its unusual smallness it was variously likened to ]s (ἴκτις/''iktis'') or ]s.{{efn|] in his treatise on animals (''De Natura Animalium'', 16:6) drew the latter comparison {{harv|Busuttil|1969|p=205}}.}} The word "Melita" in this adjectival form, attested in ],{{efn|], ] 6,612<sup>b</sup>10}} refers to the island of Malta, according to Busuttil.{{sfn|Busuttil|1969|p=205}}{{efn|This lexical argument – that Μελιταῖος/''Melitaîos''is the proper adjective for Melite/Malta, whereas the adjective for Melite/Mljet must have been Μελιτήνος/''Melitēnos'' has been challenged by the Maltese scholar Horatio Vella, who cites the adjectival form ''Melitēíos'' as an attested dialect form of ''Melitaîos'' defining a mountain in the Adriatic area near Corcyra ({{lang|grc|αἱ δ᾽ὄρεος κορυφὰς Μελιτηίου ἀμφενέμοντο}}: "others dwelt about the peaks of the Meliteian mountain") from the ] (4.1150) of ].{{sfn|Vella|1995|p=12}}}} The ] ], Aristotle's contemporary, according to the testimony of ], referred to himself as a "Maltese dog" (κύων.. Μελιταῖος/''kúōn Melitaios'').{{sfn|Ogden|2007|p=200}} A traditional story in ] contrasts the spoiling of a Maltese by his owner, compared to life of the toilsome neglect suffered by the master's ]. Envious of the spoiling attentions lavished on the pup, the ass tries to frolic and be winsome also, in order to enter his master's graces and be treated kindly, only to be beaten off and tethered to its manger.{{sfn|Busuttil|1969|p=205}}{{efn|Ὄνος καὶ κυνίδιον 275:Ἔχων τις κύνα Μελιταῖον καὶ ὄνον διετέλει ἀεὶ τῷ κυνὶ προσπαίζων· καὶ δή, εἴ ποτε ἔξω ἐδείπνει, διεκόμιζέ τι αὐτῷ, καὶ προσιόντι καὶ σαίνοντι παρέβαλλεν. Ὁ δὲ ὄνος φθονήσας προσέδραμε καὶ σκιρτῶν ἐλάκτιζεν αὐτόν. Καὶ ὃς ἀγανακτήσας ἐκέλευσε παίοντας αὐτὸν ἀπαγαγεῖν καὶ τῇ φάτνῃ προσδῆσαι {{harv|Aesop|1980|pp=304–305}}.}} | |||

| Maltese are very good with children and infants. Maltese do not require much physical exercise, although they should be walked daily to reduce problem behavior. They enjoy running and are more inclined to play games of chase, rather than play with toys. Some Maltese can occasionally be snappy with smaller children and should be supervised when playing, although socializing them at a young age will reduce this habit. The Maltese is very active within a house, and, preferring enclosed spaces, does very well with small yards. For this reason the breed also does well with apartments and townhouses, and is a prized pet of urban dwellers. | |||

| Around 280 BCE,{{sfn|Jebb|1909|p=67,n.36}} the learned ] ], according to ] writing in the Ist century CE, identified '']'' – the home of this ancient dog variety – as the Adriatic island, rather than Malta.{{efn|{{lang|la|"inter quam et Illyricum Melite, unde catulos Melitaeos appellari Callimachus auctor est"}}: "(between Corcyra Melaena) and Illyricum is Meleda, from which according to Callimachus Maltese terriers get their name".{{sfn|Pliny|1942|p=114}}{{sfn|Pfeiffer|1949|p=404}}}} Conversely, the poem ''Alexandra'' ascribed to his equally erudite contemporary ], which is now thought to have been composed around 190 BCE, also alludes to the island of Melite, but identified it as Malta.{{efn|"The identity of this island called Melite has been much discussed, but the evident proximity to Cape Pachynos, the southern promontory of Sicily, clearly indicates Malta." {{harv|Hornblower|2015|p=375}}}}{{efn|<poem>{{lang|grc|ἄλλοι δὲ Μελίτην νῆσον Ὀθρωνοῦ πέλας | |||

| == History == | |||

| πλαγκτοὶ κατοικήσουσιν, ἣν πέριξ κλύδων | |||

| ] | |||

| ἔμπλην Παχύνου Σικανὸς προσμάσσεται, | |||

| As an aristocrat of the canine world, this ancient breed has been known by a variety of names throughout the centuries. Originally called the "Melitaie Dog" he has also been known as "Ye Ancient Dogge of Malta", the "Roman Ladies' Dog," the "Majestic Creature", the "Comforter Dog," the "Spaniel Gentle," the "Bichon," the "Shock Dog," the "Maltese Lion Dog" and the "Maltese Terrier." Sometime within the past century, he has come to simply be known as the "Maltese." The breed's history can be traced back many centuries. Some have placed its origin at two or three thousand years ago and ] placed the origin of the breed at 6000 BC.<ref>Cutillo, Nicholas. 'The Complete Maltese'. Howell Book House, 1986. ISBN 0-87605-209-X</ref> | |||

| 1030τοῦ Σισυφείου παιδὸς ὀχθηρὰν ἄκραν | |||

| ἐπώνυμόν ποθ᾽ ὑστέρῳ χρόνῳ γράφων | |||

| κλεινόν θ᾽ ἵδρυμα παρθένου Λογγάτιδος, | |||

| Ἕλωρος ἔνθα ψυχρὸν ἐκβάλλει ποτόν,}}</poem> "Other wanderers shall dwell in the isle of Melita near Othronus, round which the Sicanian wave laps beside Pachynus, grazing the steep promontory that in after time shall bear the name of the son of Sisyphus, and the famous shrine of the maiden Longatis, where Helorus empties his chilly stream." {{harv|Lycophron|1921|pp=406–407}}.}}{{efn|This confusion between Malta and Mljet also recurs in ancient references to the site of the shipwreck of ] recounted in the ].}} ], writing in the early first century AD, attributed its origin to the island of Malta.{{efn|{{lang|grc|πρόκειται δὲ τοῦ Παχύνου Μελίτη, ὅθεν τὰ κυνίδια ἃ καλοῦσι Μελιταῖα καὶ Γαῦδος, ὀγδοήκοντα καὶ ὀκτὼ μίλια τῆς ἄκρας ἀμφότεραι διέχουσαι}}: "Off ] lies Melita, whence come the little dogs called Melitaean, and Gaudos, both eighty-eight miles distant from the Cape."{{sfn|Strabo|1924|pp=102–103}}}} | |||

| Aristotle's successor ] (371 – c. 287 BC), in his sketch of moral types, ''Characters'', has a chapter on a ] who exercises a petty pride in pursuing a showy ambition to be particularly fastidious in his taste (Μικροφιλοτιμία/''mikrophilotimía''). One feature he identifies with this character type is that if his pet dog dies he will erect a memorial slab commemorating his "scion of Melita."{{efn|{{lang|grc|καὶ κυναρίου δὲ Μελιταίου τελευτήσαντος αὐτῷ μνῆμα ποιῆσαι καὶ στηλίδιον ποιήσας ἐπιγράψαι ΚΛΑΔΟΣ ΜΕΛΙΤΑΙΟΣ}}: "Or if his little Melitean dog has died, he will put up a little memorial slab, with the inscription, a scion of Melita." ], or his posthumous editor, ], argued that the reference was to the Illyrian Melita, rather than Malta.{{sfn|Jebb|1909|pp=66–67,n.36}}}} ], in his voluminous early 3rd century CE ] (12:518–519), states that it was a characteristic of the Sicilian ], notorious for the extreme punctiliousness of their refined tastes, to delight in the company of owl-faced jester-dwarfs and Melite lap-dogs (rather than in their fellow human beings), with the latter accompanying them even when they went to exercise in the gymnasia.{{efn|{{lang|grc|καὶ κυνάρια Μελιταῖα, ἅπερ αὐτοῖς καὶ ἕπεσθαι εἰς τὰ γυμνάσια; οἱ Συβαρῖται ἔχαιρον τοῖς Μελιταίοις κυνιδίοις καὶ ἀνθρώποις οὐκ ἀνθρώποις}}: "also Melitê lap-dogs. Which accompany them even to the gymnasia..The Sybarites, on the contrary, took delight in Melitê puppies and human beings who were less than human."{{sfn|Athenaeus|1980|pp=334–335, 336–337}}}} | |||

| Italians sometimes called them ''botoli'', because, though small, they were ferocious and bad-tempered, ''botolo'' being an old Italian word meaning a quarrelsome little cur, or a worthless, degenerate little dog.<ref name="Briggs"> '''by Lee Rawdon Briggs''', '''''published by H. Cox in London, 1894''''' ''from the Internet Archive - www.archive.org - by Marcus Lucero'', '''pp 312-322'''</ref> | |||

| The Romans called them {{lang|la|catuli melitaei}}. During the first century, the Roman poet ] wrote descriptive verses to a ] named "Issa" owned by his friend Publius.{{sfn|Serpell|1996|p=47}}{{sfn|Franco|2019|pp=100–101}}{{efn|{{harv|Gosling|1935|pp=110–111}}:<poem>Issa's more full of sport and wanton play | |||

| The Maltese is thought to have been descended from a ] type dog found among the Swiss Lake dwellers and bred down to obtain its small size. Although there is also some evidence that the breed originated in ] and is related to the ], the exact origin is unknown <ref>Leitch, Virginia T., 1953; Carno, Dennis, 1970. ''The Maltese Dog - A History of the Breed, 2nd Ed.''. International Institute of Veterinary Science</ref>. | |||

| Than that pet sparrow by Catullus sung; | |||

| Issa's more pure and cleanly in her way | |||

| Than kisses from the amorous turtle's tongue, | |||

| Issa more winsome is than any girl | |||

| That ever yet entranced a lover's sight; | |||

| Issa's more precious than the Indian pearl | |||

| Issa's my Publius' favourite and delight. | |||

| Her plaintive voice falls sad as one that weeps; | |||

| Her master's cares and woes alike she shares; | |||

| Softly reclined upon his neck she sleeps, | |||

| And scarce to sigh or draw her breath she dares. | |||

| Her, lest the day of fate should nothing leave, | |||

| In pictured form my Publius has portrayed | |||

| Where you so lifelike Issa might perceive. | |||

| That not herself a better likeness made, | |||

| Issa together with her portrait lay, | |||

| Both real or both depicted you would say. | |||

| </poem>}} It has been claimed that Issa was a Maltese dog, and that various sources link this Publius with the ],{{sfn|Blarney|Inglee|1949|p=622}} but nothing is known of this Publius, other than that he was an unidentified friend of Paulus, a member of Martial's literary circle.{{sfn|Vioque|2017|p=410}} | |||

| ==The Maltese in modern times== | |||

| The oldest record of existence of this dog breed was found on one ] amphorae found in Vulci in ]. Archaeological explorations determined that it is a work by the artists from the Athenian school from 500 b. C. For Kinology the most important fact is that above the drawing there is a title Mealtaie, which were latter called Melitae and after that Meledae.<ref name="Kromerova"> section under the title ''Hypothesis about the origin of the name Maltese | |||

| Dog ] state that despite the rich history of the ancient breed, the modern Maltese, like many other breeds, cannot be linked by pedigree to that ancient genealogy, but, rather, emerged in the Victorian era by regulating the crossing of existing varieties of dog to produce a type that could be registered as a distinct breed. The Maltese and similar breeds such as the Havanese, Bichon and Bolognese, are indeed related, perhaps through a common ancestor resulting from a severe ] when a handful of petite canine varieties began to be selected for mating around two centuries ago.{{sfn|Gorman|2021}} | |||

| ''</ref> | |||

| In his work {{lang|la|Insulae Melitae Descriptio}}, the first history of its kind,{{sfn|Delgado|2020|pp=16–17}} ] ], Secretary to the ] of the ] ], wrote in 1536 that, while classical authors wrote of Maltese dogs, which perhaps might formerly have been born there, the local Maltese people of his time were no longer familiar with the species.{{efn|{{lang|la|"Huic insulae Strabo nobiles illos, adagio, non minus quam medicinis, canes adscribit, inde Melitaeos dictos, Plinio, & nunc etiam incolis ignotos, tunc forte nascebantur."}}{{sfn|Quintin|1536|p=24}}}} | |||

| First written document on the existance of this breed of dog was given by the Greek author ]. He described the Canis melitaeus 230 b. C. as the small dog originated from the Isle Melitaeus and placed that island in front of the Adriatic coast. It is without doubt and most clear that the author indicated the island in the ]<ref name="Kromerova"></ref><ref name="Briggs"></ref> and not in the Mediterranean Sea, therefore it cannot be a mix-up but a very clear description of the association of the dog with the Island of ] in ]. <!-- called Mljet for the last 1200 years by Croats who came to this part of the world in and around year 600. Pietri's position of denial of the necessity of adding a relation of Mljet to Croatia is his obvious bias toward the issue. --> | |||

| ], physician to ], writing of women's chamber pets, {{lang|la|canes delicati}} such as the ''Comforter'' or ''Spanish Gentle,'' stated that they were known as "Melitei" hailing from Malta,{{sfn|Lytton|1911|pp=25–27}} though the species he describes were actually ]s,{{sfn|Drury|1903|p=577}}{{sfn|Leighton|1910|p=274}} perhaps of the recently imported ] type. A variation of the latter was the ] toy dog, bred by the ], with its distinctive white and chestnut mantle.{{sfn|Welsh|1882|p=238}} Red and white mantled varieties of these toy pets, the King Charles or ] Blenheim breeds, were all the fashion in the 17th.century, down through the early decades of the 19th.century.{{sfn|Welsh|1882|p=238}} | |||

| ] confirms the description gave by Callimachus in his famous '']''.<ref> translated by Philemon Holland, (1601), ''from uchicago.edu'' a page maintained by James Eason</ref><ref> contains the article ''An Answer to a late Book written against the Learned and Reverend Dr. Bentley, relating to some Manuscript Notes on Callimachus. Together with an Examination of Mr. Bennet's Appendix to the said Book. Concluded.'' (pp 370-380) written by an unknown author in London and first printed in the year 1699, '''p. 373'''</ref> | |||

| In 1837 ] painted ''The Lion Dog from Malta: The Last of his Tribe'', a portrait of a dog named Quiz, a petite flossy white creature poised next to a huge ], commissioned by ] as a birthday present for her mother, the ], whose dog it was.{{sfn|Lee|1899|p=345}}{{sfn|Stephens|1874|p=105}} According to ], shortly after Landseer's canvases, the London ''fancy'' of toy dog enthusiasts took to importing exemplars of the Chinese spaniel, with their short faces and snub noses, and crossbred these with ]s and ]s to select for puppies with a longer "feather" or fleecing on their ears and limbs.{{sfn|Welsh|1882|p=239}} Some time later, the London market began to deal in what were called "Maltese" dogs. These had no known connection to that island, and one of the breeders, T. V. H. Lukey, associated with the ], stated that his own Maltese strain was imported from ] in 1841.{{sfn|Welsh|1882|p=241}} | |||

| ], in his "Hierozoicon," also quotes Callimachus to be correct. ] quotes pretty freely from the other writers, especially as to the origin of this little dog, ] ascribing it to Spain and ] to Lyons.<ref name="Briggs"></ref> | |||

| A strain of this type was accepted as a distinct class at the ] in ] in 1862, when a breeder, R. Mandeville, took first prize and continued to do so in subsequent years.{{sfn|Welsh|1882|pp=241–242}} From 1869 to 1879, Mandeville swept the board of most shows in ], Islington, the ], and ], and his kennels were considered to have furnished the finest strain for subsequent Maltese breeding.{{sfn|Various|2010}} From the 19th. century onwards, the requirement emerged for the Maltese to have an exclusively white coat.{{sfn|Raymond-Mallock|1907|p=63}} Despite the unknown provenance, by the close of the century, the dog-expert William Drury noted that nearly all English writers of that period associated the breed with Malta, without adducing any evidence for the claim.{{sfn|Drury|1903|p=577}} | |||

| Maltese are generally associated with the island of ] in the ]. The dogs probably made their way to ] through the ] with the migration of nomadic tribes. Some writers believe these proto-Maltese were used for rodent control and pig herding. | |||

| <ref></ref><ref></ref> before the appearance of the breed gained paramount importance. The Isle of Malta (or Melitae as it was then known) was a geographic center of early trade, and explorers undoubtedly found ancestors of the tiny, white dogs left there as barter for necessities and supplies. The dogs were favored by the wealthy and royalty alike and were bred over time to specifically be a companion animal. In fact, the Maltese were so favored by the Roman emperors, they chose to breed them to be pure white - something they considered a 'sacred color'. Before then, there were other light colors that Maltese come in - still seen again at the puppy stage, normally. | |||

| A white dog was shown as a "Maltese Lion Dog" at the first ] in ] in 1877.{{sfn|Brearley|1984|p=29}} From that time they were occasionally crossed with poodles, and a stud book, based on the issue of two females, was established in 1901. By the 1950s, this registry counted roughly 50 dogs in its pedigree table.{{sfn|Gorman|2021}} The Maltese was recognised as a breed by the ] in 1888.{{sfn|AKC|2022}} It was definitively accepted by the ] under the ] of Italy in 1955.{{sfn|AISBL|2015}} | |||

| During the first century, ], the Roman governor of Malta, had a Maltese named Issa of which he was very fond. | |||

| == |

== Characteristics == | ||

| underneath eyes and around the muzzle.]] | ] | ||

| The ] is dense, glossy, silky and shiny, falling heavily along the body without curls or an ].{{sfn|AISBL|2015}} The colour is pure white, however a pale ivory tinge or light brown spotting is permitted.{{sfn|AISBL|2015}} Adult weight is usually {{convert|3|–|4|kg|lb|abbr=on|0}}.{{sfn|AISBL|2015}} Females are about {{convert|20|–|23|cm|abbr=on|0}} tall, males slightly more.{{sfn|AISBL|2015}} They behave in a lively, calm, and affectionate manner.{{sfn|AISBL|2015}} | |||

| Maltese have no undercoat, and have little to no shedding if cared for properly. Like their relatives ]s and ], they are considered to be largely ] and many people who are allergic to ]s may not be allergic to the Maltese (See list of ]). They make very good friends with different breeds especially the ]. Daily cleaning is required to prevent the risk of tear-staining. | |||

| The Maltese does not shed.{{sfn|Alderton|2010|p=59}} Like other white dogs, they may show tear-stains.{{sfn|Leighton|1910|p=297}}{{sfn|Fielheller}} | |||

| The breed may be prone to health problems such as liver and heart issues, and ]. They should be checked for conditions like "Patent Ductus Arteriosus".{{efn|'Maltese can develop luxating patellas, an inherited condition where one or both of the kneecaps pop in and out of place. Although patellar luxation is not generally considered a painful condition, it may cause the dog to favor one leg and can predispose them to other knee injuries (such as a cranial cruciate ligament tear) and arthritis. Depending on the severity of the luxating patella, surgery may be recommended to prevent further injury and improve your Maltese’s quality of life. Responsible Maltese breeders will screen their puppies for heart abnormalities such as patent ductus arteriosus. PDA is an inherited condition where the ductus arteriosus, the normal opening between the two major blood vessels in the heart that closes shortly after birth, does not close. This condition causes blood to flow improperly and forces the left side of the heart to work harder. This leads to eventual failure of that chamber. Depending on the size of the opening, dogs may show minimal symptoms to severe signs of heart failure.' {{sfn|Kho-Pelfrey|2022}}}} | |||

| Regular grooming is also required, to prevent the coats of non-shedding dogs from matting. Many owners will keep their Maltese clipped in a "puppy cut," a 1 - 2" all over trim that makes the dog resemble a puppy. Some owners, especially those who show Maltese in the sport of ], prefer to wrap the long fur to keep it from matting and breaking off, and then to show the dog with the hair unwrapped combed out to its full length. | |||

| Of note, the breed is also highly recommended for those with dog allergies, as the breed is considered hypoallergenic. Hence, some people with dog allergies may be able to tolerate living with a Maltese as they shed less fur.{{sfn|Johnstone|2023}} | |||

| Dark staining in the hair around the eyes ("") can be a problem in this breed, and is mostly a function of how much the individual dog's eyes water and the size of the tear ducts. Tear stain can be readily removed if a fine-toothed metal comb, moistened with lukewarm water, is carefully drawn through the snout hair just below the eyes. This maintenance activity must be performed every two or three days, as a layer of sticky goo is quick to redevelop. If the face is kept dry and cleaned daily, the staining can be minimized. Many veterinarians recommend avoiding foods treated with food coloring and serving distilled water to reduce tear staining. Also, giving the dog bottled water may help. | |||

| == |

== Use == | ||

| The Maltese is kept for ], for ornament, or for ].{{sfn|MSAKC|2022}} It is ranked 59th of 79 breeds assessed for intelligence by ].{{sfn|Coren|2006|p=124}} | |||

| Many toy breeds and small dogs are known to yap, scream or bite ankles. While Maltese dogs are not given to excessive barking, they will generally sound the alarm at noises in the night. In fact, legend has it that the ancient Romans would use the Maltese as alarm dogs{{Fact|date=August 2007}}, and raised them with ]s, or a proto-Rottweiler breed. Intruders would first be confronted with the diminutive Maltese, only to be later confronted with their more formidable companions. | |||

| ==Health== | |||

| An isolated study in the Australian state of ] found owners there likely to dump their Maltese terriers,<ref name="burkesbackyard">http://www.burkesbackyard.com.au/factsheets/Others/Dog-Dumpage/2960</ref> citing their tendency to bark constantly.<ref name="burkesbackyard"></ref> Such actions are condemned by animal protection agencies. | |||

| A 2024 UK study found a life expectancy of 13.1 years for the breed compared to an average of 12.7 for purebreeds and 12 for ].<ref>{{cite journal | last=McMillan | first=Kirsten M. | last2=Bielby | first2=Jon | last3=Williams | first3=Carys L. | last4=Upjohn | first4=Melissa M. | last5=Casey | first5=Rachel A. | last6=Christley | first6=Robert M. | title=Longevity of companion dog breeds: those at risk from early death | journal=Scientific Reports | publisher=Springer Science and Business Media LLC | volume=14 | issue=1 | date=2024-02-01 | issn=2045-2322 | doi=10.1038/s41598-023-50458-w | page=| pmc=10834484 }}</ref> A 2024 Italian study found a life expectancy of 11 years for the breed compared to 10 years overall.<ref>{{cite journal | last=Roccaro | first=Mariana | last2=Salini | first2=Romolo | last3=Pietra | first3=Marco | last4=Sgorbini | first4=Micaela | last5=Gori | first5=Eleonora | last6=Dondi | first6=Maurizio | last7=Crisi | first7=Paolo E. | last8=Conte | first8=Annamaria | last9=Dalla Villa | first9=Paolo | last10=Podaliri | first10=Michele | last11=Ciaramella | first11=Paolo | last12=Di Palma | first12=Cristina | last13=Passantino | first13=Annamaria | last14=Porciello | first14=Francesco | last15=Gianella | first15=Paola | last16=Guglielmini | first16=Carlo | last17=Alborali | first17=Giovanni L. | last18=Rota Nodari | first18=Sara | last19=Sabatelli | first19=Sonia | last20=Peli | first20=Angelo | title=Factors related to longevity and mortality of dogs in Italy | journal=Preventive Veterinary Medicine | volume=225 | date=2024 | doi=10.1016/j.prevetmed.2024.106155 | page=106155| doi-access=free | hdl=11585/961937 | hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ==Crossbred Maltese dogs== | |||

| ] | |||

| A ] is a dog with two purebred parents of different breeds. Dogs traditionally were crossed in this manner in hopes of creating a puppy with desirable qualities from each parent. For pet dogs, crosses may be done to enhance the marketability of puppies, and are often given cute ] names. Maltese are often deliberately crossed with ]s and ]s to produce small, fluffy lap dogs. Maltese-Poodle crosses are called ]s. Maltese crossed with ]s are also seeing an increase in popularity. Maltese with ]s are called ''Mal-Shihs'', ''Shihtese'', or ''Mitzus''. This results in a dog which is a small, friendly and intelligent animal with a unique low (or no) shedding coat. | |||

| Maltese crosses, like other crossbred dogs, are not eligible for registration by kennel clubs as they are not a ''breed'' of dog. Each kennel club has specific requirements for the registration of new breeds of dog, usually requiring careful record keeping for many generations, and the development of a breed club. At times, a crossbred dog will result in a new breed, as in the case in the 1950s when a Maltese and ] were accidentally bred. Descendants of that breeding are now a purebred breed of dog, the ]. | |||

| ==Maltese mixed-breed dogs== | |||

| Mixed breed dogs are those of generally unknown ancestry, or complex ancestry. In the popular 1974 film '']'', the part of the dog Benji's heroic love interest, Tiffany, was played by a mixed breed female of primarily Maltese ancestry. She also appeared, with her mixed-breed puppies, in the film's 1977 sequel, ''For the Love of Benji''. | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == |

==Notes== | ||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| <references /> | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| {{Reflist|20em}} | |||

| ==Sources== | |||

| {{refbegin|30em}} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Esopo Favole | |||

| | last = Aesop | year = 1980 | |||

| | author-link = Aesop | |||

| | orig-year = First published 1951 | |||

| | editor1-last = Manganelli | editor1-first = Giorgio | editor1-link = Giorgio Manganelli | |||

| | editor2-last = Valla | editor2-first = Elena Ceva | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://el.wikisource.org/%CE%A3%CE%B5%CE%BB%CE%AF%CE%B4%CE%B1:%C3%89sope_-_Fables_-_%C3%89mile_Chambry.djvu/295εἰσιν. | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The Dog Selector: How to Choose the Right Dog for You | |||

| | last = Alderton | first = David | year = 2010 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=NWDzQwAACAAJ | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-764-16365-4 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Argonautiques | |||

| | last = ((Apollonius de Rhodes)) | year = 1981 | |||

| | author-link = Apollonius of Rhodes | |||

| | editor-last = Vian | editor-first = Francis | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | volume = 3 | |||

| | isbn = 2-251-10353-8 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Deipnosophistae | |||

| | last = Athenaeus | year = 1980 | |||

| | author-link = Athenaeus | |||

| | editor-last = Gulick | editor-first = Charles Burton | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | volume = 5 | |||

| | url = http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2013.01.0001%3Abook%3D12 | |||

| | isbn = 0-434-99274-7 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The Complete Dog Book. The care, handling, and feeding of dogs; and Pure bred dogs; the recognized breeds and standards | |||

| | editor1-last = Blarney | editor1-first = Edwin Reginald | |||

| | editor2-last = Inglee | editor2-first = Charles Topping | |||

| | year = 1949 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=TDy4AAAAIAAJ&q=publius+governor+issa+martial | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The Book of the Maltese | |||

| | last = Brearley | first = Joan McDonald | year = 1984 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-876-66563-3 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Breeds by Year Recognized | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://www.akc.org/press-center/articles-resources/facts-and-stats/breeds-year-recognized/ | |||

| | date = 3 May 2022 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|AKC|2022}} | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | title = The Maltese Dog | |||

| | last = Busuttil | first = J. | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | year = 1969 | volume = 16 | issue = 2 | pages = 205–208 | |||

| | doi = 10.1017/S0017383500017058 | jstor = 642850 | s2cid = 163799376 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The Intelligence of Dogs | |||

| | last = Coren | first = Stanley | year = 2006 | |||

| | author-link = Stanley Coren | |||

| | publisher = ] | location = London | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-416-50287-6 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The Complete Maltese | |||

| | last = Cutillo | first = Nicholas | year = 1986 | |||

| | publisher = Howell | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-876-05209-9 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite news| title = The Maltese dog: a toy for ancient royalty | |||

| | last = Delgado | first = Albert | |||

| | newspaper = ] | |||

| | url = https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/the-maltese-dog-a-toy-for-ancient-royalty.778457 | |||

| | date = 16 March 2020 | access-date = 7 June 2022 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite news| title = Dog Breed Directory: Maltese | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = http://animal.discovery.com/breedselector/dogprofile.do?id=2220 | url-status = dead | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110613032437/http://animal.discovery.com/breedselector/dogprofile.do?id=2220 | |||

| | access-date = 29 August 2009 | archive-date = 13 June 2011 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|AP}} | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = British Dogs: Their Points, Selection, and Show Preparation | |||

| | last = Drury | first = William D. | year = 1903 | |||

| | publisher = L. Upcott Gill, ] | |||

| | url = https://ia800401.us.archive.org/10/items/britishdogsthei00drurgoog/britishdogsthei00drurgoog.pdf | |||

| | pages = 575–581 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite news| title = Tear Staining | |||

| | last = Fielheller | first = Vicki | |||

| | publisher = American Maltese Association | |||

| | url = https://www.americanmaltese.org/ama-health-information/tear-staining | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| chapter = Dogs and Humans in Ancient Greece and Rome: Towards a Definition of Extended Appropriate Interaction | |||

| | last = Franco | first = Cristiana | year = 2019 | |||

| | title = Dog's Best Friend?: Rethinking Canid-Human Relations | |||

| | editor1-last = Sorenson | editor1-first = John | |||

| | editor2-last = Matsuoka | editor2-first = Atsuko | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | chapter-url = https://www.academia.edu/41266371 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-773-55906-6 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite news| title = How Old Is the Maltese, Really? | |||

| | last = Gorman | first = James | |||

| | newspaper = ] | |||

| | url = https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/04/science/dogs-DNA-breeds-maltese.html | |||

| | date = 4 October 2021 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | title = Pets in Classical Times | |||

| | last = Gosling | first = W. F. | |||

| | journal = Greece & Rome | |||

| | date = February 1935 | volume = 4 | issue = 11 | pages = 109–113 | |||

| | doi = 10.1017/S0017383500003144 | jstor = 640982 | s2cid = 162223203 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Lycophron Alexandra | |||

| | last = Hornblower | first = Simon | year = 2015 | |||

| | author-link = Simon Hornblower | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-199-57670-8 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The Characters of Theophrastus | |||

| | last = Jebb | first = R. C. | year = 1909 | |||

| | author-link = Richard Claverhouse Jebb | |||

| | orig-year = First published 1870 | |||

| | editor-last = Sandys | editor-first = J. E. | editor-link = John Edwin Sandys | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://ia902902.us.archive.org/21/items/theoprastouchara00theouoft/theoprastouchara00theouoft.pdf | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | title = The Portrayal of the Dog on Greek Vases | |||

| | last = Johnson | first = Helen M. | |||

| | journal = The Classical Weekly | |||

| | date = 19 May 1919 | volume = 12 | issue = 27 | pages = 209–213 | |||

| | doi = 10.2307/4387846 | jstor = 4387846 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite web| title = Does a Completely Hypoallergenic Dog Exist? | |||

| | last = Johnstone | first = Gemma | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/dog-breeds/do-hypoallergenic-dog-exist/ | |||

| | date = 7 December 2023 | access-date = 30 December 2023 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite web| title = Maltese | |||

| | last = Kho-Pelfrey | first = Teresa | |||

| | website = Pet MD | |||

| | url = https://www.petmd.com/dog/breeds/maltese | |||

| | date = 17 October 2022 | access-date = 30 December 2023 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Modern Dogs (Non-Sporting Division), including Toy, Pet, Fancy, and Ladies' Dogs | edition = 3rd | |||

| | last = Lee | first = Rawden B. | year = 1899 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/download/historydescripti00leeriala/historydescripti00leeriala.pdf | |||

| | via = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Dogs and all about them | |||

| | last = Leighton | first = Robert | year = 1910 | |||

| | author-link = Robert Leighton (author) | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://ia600300.us.archive.org/13/items/dogsallaboutthem00leig/dogsallaboutthem00leig.pdf | |||

| | pages = 296–300 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Callimachus, Lycophron, Aratus | |||

| | last = Lycophron | year = 1921 | |||

| | author-link = Lycophron | |||

| | editor-last = Mair | editor-first = A.W. | editor-link = Alexander William Mair | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2008.01.0484 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Toy Dogs and Their Ancestors | |||

| | last = Lytton | first = Mrs Neville | year = 1911 | |||

| | author-link = Judith Blunt-Lytton, 16th Baroness Wentworth | |||

| | publisher = ] | location = New York | |||

| | url = https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/94215#page/77/mode/1up | via = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite book| chapter = Sickness and in Health: Care for an Arthritic Maltese Dog from the Roman Cemetery of Yasmina, Carthage, Tunisia | |||

| | last1 = MacKinnon | first1 = Michael | |||

| | last2 = Belanger | first2 = Kyle | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | title = Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction: Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology, Durham, August 2002 | |||

| | editor1-last = Snyder | editor1-first = Lynn M. | |||

| | editor2-last = Moore | editor2-first = Elizabeth A. | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=8u4mDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA43 | |||

| | pages = 38–43 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-785-70399-7 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite news| title = Maltese | |||

| | publisher = ] | location = Thuin, Belgium | |||

| | url = http://www.fci.be/Nomenclature/Standards/065g09-en.pdf | |||

| | date = 17 December 2015 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|AISBL|2015}} | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal | title = The Hegesiboulos Cup | |||

| | last = Moore | first = Mary B. | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | year = 2008 | volume = 43 | pages = 11–37 | |||

| | doi = 10.1086/met.43.25699084 | jstor = 25699084 | s2cid = 192949602 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = In Search of the Sorcerer's Apprentice: The traditional tales of Lucian's Lover of Lies | |||

| | last = Ogden | first = Daniel | year = 2007 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=tRctEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA201 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-914-53510-9 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite news| title = Pet Information: The Maltese | |||

| | newspaper = ]/] | |||

| | url = https://manilastandard.net/pets/314212152/pet-information-the-maltese.html | |||

| | date = 5 March 2022 | |||

| | ref = {{harvid|MSAKC|2022}} | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Callimachus | |||

| | last = Pfeiffer | first = Rudolf | year = 1949 | |||

| | author-link = Rudolf Pfeiffer | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | volume = 1 | |||

| | isbn = 0-19-814115-7 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Natural History | |||

| | last = Pliny | year = 1942 | |||

| | author-link = Pliny the Elder | |||

| | editor-last = Rackham | editor-first = Harris | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | volume = 2 | |||

| | isbn = 0-674-99388-8 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Insulae Melitae descriptio ex commentariis rerum quotidianarum | |||

| | last = Quintin | first = Jean | year = 1536 | |||

| | author-link = Jean Quintin | |||

| | publisher = ] | location = Lyon | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Sxe7O-l716UC | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The Up-to-date Toy Dog: The History, Points and Standards of English Toy Spaniels, Japanese Spaniels, Pomeranians, Toy Terriers, Pugs, Pekinese, Griffon Bruxellois, Maltese and Italian Greyhounds | |||

| | last = Raymond-Mallock | first = Lilian C. | year = 1907 | |||

| | publisher = The Dogdom Publishing Company | location = Battle Creek, Michigan | |||

| | url = https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn25kh&view=1up&seq=67 | via = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = In the company of animals: a study of human-animal relationships | |||

| | last = Serpell | first = James | year = 1996 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=v9gKhfo0MDgC&q=publius+dog+issa&pg=PA47 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-521-57779-3 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Memoirs of Sir Edwin Landseer: A Sketch of the Life of the Artist, Illustrated with Reproductions of Twenty-four of His Most Popular Works | |||

| | last = Stephens | first = Frederic George | year = 1874 | |||

| | author-link = Frederic George Stephens | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Byk-AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA101 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The Geography of Strabo | |||

| | last = Strabo | year = 1924 | |||

| | author-link = Strabo | |||

| | editor-last = Jones | editor-first = Horace Leonard | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0198%3Abook%3D6%3Achapter%3D2%3Asection%3D11 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-674-99201-6 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{Cite book| chapter = Companions from the Oldest Times: Dogs in Ancient Greek Literature, Iconography and Osteological Testimony | |||

| | last = Trantalidou | first = Katerina | year = 2006 | |||

| | title = Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction: Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology, Durham, August 2002 | |||

| | editor1-last = Snyder | editor1-first = Lynn M. | |||

| | editor2-last = Moore | editor2-first = Elizabeth A. | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | chapter-url = https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281289733 | |||

| | via = ] | |||

| | pages = 96–120 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-785-70399-7 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The Maltese Dog-A Complete Anthology of the Dog 1860-1940 | |||

| | last = Various | year = 2010 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=FcHEAQAAQBAJ | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-445-52750-5 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite journal | title = The island of Gozo in classical texts | |||

| | last = Vella | first = Horatio C. R. | |||

| | journal = Occasional Papers on Islands and Small States | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | date = September 1995 | volume = 13 | pages = 1–40 | |||

| | url = https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/bitstream/123456789/41217/1/The_Island_of_Gozo_in_Classical_Texts.pdf | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = Martial, Book VII. A Commentary | |||

| | last = Vioque | first = Guillermo Galán | year = 2017 | |||

| | translator = J. J. Zoltowsky | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=9__0DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA410 | |||

| | isbn = 978-9-004-35097-7 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book| title = The dogs of the British Islands, being a series of articles on the points of their various breeds, and the treatment of the diseases to which they are subject | edition = 4th | |||

| | last = Welsh | first = J. H. | year = 1882 | |||

| | author-link = John Henry Welsh | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://ia802703.us.archive.org/19/items/dogsofbritishisl00walsrich/dogsofbritishisl00walsrich.pdf | |||

| | pages = 238–242 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite dictionary| title = Pets | |||

| | last1 = White | first1 = Sheila | |||

| | last2 = Hornblower | first2 = Simon | |||

| | author2-link = Simon Hornblower | |||

| | year = 2012 | |||

| | dictionary = The Oxford Classical Dictionary | |||

| | editor1-last = Hornblower | editor1-first = Simon | editor1-link = Simon Hornblower | |||

| | editor2-last = Spawforth | editor2-first = Antony | |||

| | editor3-last = Eidinow | editor3-first = Esther | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=bVWcAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA1118 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-199-54556-8 | |||

| }} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|Maltese dog|position=left}} | |||

| * | |||

| * Clubs, Associations, Resources and Societies | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| ** | |||

| <!--===========================({{NoMoreLinks}})=============================== | |||

| | PLEASE BE CAUTIOUS IN ADDING MORE LINKS TO THIS ARTICLE. WIKIPEDIA IS | | |||

| | NOT A COLLECTION OF LINKS. | | |||

| | | | |||

| | Excessive or inappropriate links WILL BE DELETED. | | |||

| | See ] and ] for details. | | |||

| | | | |||

| | If there are already plentiful links, please propose additions or | | |||

| | replacements on this article's discussion page. Or submit your link | | |||

| | to the appropriate category at the Open Directory Project (www.dmoz.org)| | |||

| | and link back to that category using the {{dmoz}} template. | | |||

| ===========================({{NoMoreLinks}})===============================--> | |||

| {{Toy dogs}} | {{Toy dogs}} | ||

| {{Italian dogs}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:59, 6 November 2024

Breed of toy dog For other uses, see Maltese.Dog breed

| Maltese | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Maltese groomed with overcoat Maltese groomed with overcoat | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin | Italy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dog (domestic dog) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Maltese dog refers both to an ancient variety of dwarf, white-coated dog breed from Italy and generally associated also with the island of Malta, and to a modern breed of similar dogs in the toy group, genetically related to the Bichon, Bolognese, and Havanese breeds. The precise link, if any, between the modern and ancient breeds is not known. Nicholas Cutillo suggested that Maltese dogs might descend from spitz-type canines, and that the ancient variety probably was similar to the latter Pomeranian breeds with their short snout, pricked ears, and bulbous heads. These two varieties, according to Stanley Coren, were perhaps the first dogs employed as human companions.

The modern variety traditionally has a silky, pure-white coat, hanging ears and a tail that curves over its back, and weighs up to 3–4 kg (7–9 lb). The Maltese does not shed. The Maltese is kept for companionship, ornament, or competitive exhibition.

Maltese dogs in antiquity

The old variety of Maltese appears to have been the most common or favourite pet, or certainly household dog, in antiquity. Dogs of various sizes and shapes are depicted on vases and amphorae. On one Attic amphora from about 500 BC, excavated at Vulci in the nineteenth century and now lost, an illustration of a small dog with a pointed muzzle is accompanied by the word μελιταῖε, melitaie.

Numerous references to these dogs are found in Ancient Greek and Roman literature. Ancient writers variously attribute its origin either to the island of Malta in the Mediterranean, called Melita in Latin, – a name which derives from the Carthaginian city of that name on the island, Melite – or to the Adriatic island of Mljet, near Corfu and off the Dalmatian coast of modern Croatia, also called Melita in Latin. The uncertainty continues, but recent scholarship generally supports the identification with Malta.

In Greece in the classical period a variety of diminutive dog (νανούδιον/nanoúdion -"dwarf dog") was called a Μελιταῖον κυνίδιον (Melitaion kunídion, "small dog from Melita"). In its unusual smallness it was variously likened to martens (ἴκτις/iktis) or pangolins. The word "Melita" in this adjectival form, attested in Aristotle, refers to the island of Malta, according to Busuttil. The Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope, Aristotle's contemporary, according to the testimony of Diogenes Laertius, referred to himself as a "Maltese dog" (κύων.. Μελιταῖος/kúōn Melitaios). A traditional story in Aesop's Fables contrasts the spoiling of a Maltese by his owner, compared to life of the toilsome neglect suffered by the master's ass. Envious of the spoiling attentions lavished on the pup, the ass tries to frolic and be winsome also, in order to enter his master's graces and be treated kindly, only to be beaten off and tethered to its manger.

Around 280 BCE, the learned Hellenistic poet Callimachus, according to Pliny the Elder writing in the Ist century CE, identified Melite – the home of this ancient dog variety – as the Adriatic island, rather than Malta. Conversely, the poem Alexandra ascribed to his equally erudite contemporary Lycophron, which is now thought to have been composed around 190 BCE, also alludes to the island of Melite, but identified it as Malta. Strabo, writing in the early first century AD, attributed its origin to the island of Malta.

Aristotle's successor Theophrastus (371 – c. 287 BC), in his sketch of moral types, Characters, has a chapter on a type of person who exercises a petty pride in pursuing a showy ambition to be particularly fastidious in his taste (Μικροφιλοτιμία/mikrophilotimía). One feature he identifies with this character type is that if his pet dog dies he will erect a memorial slab commemorating his "scion of Melita." Athenaeus, in his voluminous early 3rd century CE Deipnosophistae (12:518–519), states that it was a characteristic of the Sicilian Sybarites, notorious for the extreme punctiliousness of their refined tastes, to delight in the company of owl-faced jester-dwarfs and Melite lap-dogs (rather than in their fellow human beings), with the latter accompanying them even when they went to exercise in the gymnasia.

The Romans called them catuli melitaei. During the first century, the Roman poet Martial wrote descriptive verses to a lap dog named "Issa" owned by his friend Publius. It has been claimed that Issa was a Maltese dog, and that various sources link this Publius with the Roman Governor Publius of Malta, but nothing is known of this Publius, other than that he was an unidentified friend of Paulus, a member of Martial's literary circle.

The Maltese in modern times

Dog genomic experts state that despite the rich history of the ancient breed, the modern Maltese, like many other breeds, cannot be linked by pedigree to that ancient genealogy, but, rather, emerged in the Victorian era by regulating the crossing of existing varieties of dog to produce a type that could be registered as a distinct breed. The Maltese and similar breeds such as the Havanese, Bichon and Bolognese, are indeed related, perhaps through a common ancestor resulting from a severe bottleneck when a handful of petite canine varieties began to be selected for mating around two centuries ago.

In his work Insulae Melitae Descriptio, the first history of its kind, Abbé Jean Quintin, Secretary to the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta Philippe Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, wrote in 1536 that, while classical authors wrote of Maltese dogs, which perhaps might formerly have been born there, the local Maltese people of his time were no longer familiar with the species.

John Caius, physician to Queen Elizabeth I, writing of women's chamber pets, canes delicati such as the Comforter or Spanish Gentle, stated that they were known as "Melitei" hailing from Malta, though the species he describes were actually Spaniels, perhaps of the recently imported King Charles Spaniel type. A variation of the latter was the Blenheim toy dog, bred by the Marlborough family, with its distinctive white and chestnut mantle. Red and white mantled varieties of these toy pets, the King Charles or Oxfordshire Blenheim breeds, were all the fashion in the 17th.century, down through the early decades of the 19th.century.

In 1837 Edwin Landseer painted The Lion Dog from Malta: The Last of his Tribe, a portrait of a dog named Quiz, a petite flossy white creature poised next to a huge Newfoundland dog, commissioned by Queen Victoria as a birthday present for her mother, the Duchess of Kent, whose dog it was. According to John Henry Welsh, shortly after Landseer's canvases, the London fancy of toy dog enthusiasts took to importing exemplars of the Chinese spaniel, with their short faces and snub noses, and crossbred these with pugs and bulldogs to select for puppies with a longer "feather" or fleecing on their ears and limbs. Some time later, the London market began to deal in what were called "Maltese" dogs. These had no known connection to that island, and one of the breeders, T. V. H. Lukey, associated with the English mastiff, stated that his own Maltese strain was imported from the Manilla Islands in 1841.

A strain of this type was accepted as a distinct class at the Agricultural Hall Show in Islington in 1862, when a breeder, R. Mandeville, took first prize and continued to do so in subsequent years. From 1869 to 1879, Mandeville swept the board of most shows in Birmingham, Islington, the Crystal Palace, and Cremorne Gardens, and his kennels were considered to have furnished the finest strain for subsequent Maltese breeding. From the 19th. century onwards, the requirement emerged for the Maltese to have an exclusively white coat. Despite the unknown provenance, by the close of the century, the dog-expert William Drury noted that nearly all English writers of that period associated the breed with Malta, without adducing any evidence for the claim.

A white dog was shown as a "Maltese Lion Dog" at the first Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show in New York City in 1877. From that time they were occasionally crossed with poodles, and a stud book, based on the issue of two females, was established in 1901. By the 1950s, this registry counted roughly 50 dogs in its pedigree table. The Maltese was recognised as a breed by the American Kennel Club in 1888. It was definitively accepted by the Fédération Cynologique Internationale under the patronage of Italy in 1955.

Characteristics

The coat is dense, glossy, silky and shiny, falling heavily along the body without curls or an undercoat. The colour is pure white, however a pale ivory tinge or light brown spotting is permitted. Adult weight is usually 3–4 kg (7–9 lb). Females are about 20–23 cm (8–9 in) tall, males slightly more. They behave in a lively, calm, and affectionate manner. The Maltese does not shed. Like other white dogs, they may show tear-stains.

The breed may be prone to health problems such as liver and heart issues, and Luxating patella. They should be checked for conditions like "Patent Ductus Arteriosus".

Of note, the breed is also highly recommended for those with dog allergies, as the breed is considered hypoallergenic. Hence, some people with dog allergies may be able to tolerate living with a Maltese as they shed less fur.

Use

The Maltese is kept for companionship, for ornament, or for competitive exhibition. It is ranked 59th of 79 breeds assessed for intelligence by Stanley Coren.

Health

A 2024 UK study found a life expectancy of 13.1 years for the breed compared to an average of 12.7 for purebreeds and 12 for crossbreeds. A 2024 Italian study found a life expectancy of 11 years for the breed compared to 10 years overall.

See also

Notes

- "small dogs were also kept as household pets. The commonest of these seems to be an animal resembling the Maltese, an animal with small upright ears and long hair." (Trantalidou 2006, p. 107)

- "the favourite pet dog of antiquity seems to have been the Maltese." (Gosling 1935, p. 100)

- "The commonest pet was the small white long-coated Maltese dog represented on 5th-cent. BC Attic vases and gravestones." (White & Hornblower 2012, p. 1118)

- Aelian in his treatise on animals (De Natura Animalium, 16:6) drew the latter comparison (Busuttil 1969, p. 205).

- Aristotle, Hist Anim.ix 6,61210

- This lexical argument – that Μελιταῖος/Melitaîosis the proper adjective for Melite/Malta, whereas the adjective for Melite/Mljet must have been Μελιτήνος/Melitēnos has been challenged by the Maltese scholar Horatio Vella, who cites the adjectival form Melitēíos as an attested dialect form of Melitaîos defining a mountain in the Adriatic area near Corcyra (αἱ δ᾽ὄρεος κορυφὰς Μελιτηίου ἀμφενέμοντο: "others dwelt about the peaks of the Meliteian mountain") from the Argonautica (4.1150) of Apollonius of Rhodes.

- Ὄνος καὶ κυνίδιον 275:Ἔχων τις κύνα Μελιταῖον καὶ ὄνον διετέλει ἀεὶ τῷ κυνὶ προσπαίζων· καὶ δή, εἴ ποτε ἔξω ἐδείπνει, διεκόμιζέ τι αὐτῷ, καὶ προσιόντι καὶ σαίνοντι παρέβαλλεν. Ὁ δὲ ὄνος φθονήσας προσέδραμε καὶ σκιρτῶν ἐλάκτιζεν αὐτόν. Καὶ ὃς ἀγανακτήσας ἐκέλευσε παίοντας αὐτὸν ἀπαγαγεῖν καὶ τῇ φάτνῃ προσδῆσαι (Aesop 1980, pp. 304–305).

- "inter quam et Illyricum Melite, unde catulos Melitaeos appellari Callimachus auctor est": "(between Corcyra Melaena) and Illyricum is Meleda, from which according to Callimachus Maltese terriers get their name".

- "The identity of this island called Melite has been much discussed, but the evident proximity to Cape Pachynos, the southern promontory of Sicily, clearly indicates Malta." (Hornblower 2015, p. 375)

-

ἄλλοι δὲ Μελίτην νῆσον Ὀθρωνοῦ πέλας

"Other wanderers shall dwell in the isle of Melita near Othronus, round which the Sicanian wave laps beside Pachynus, grazing the steep promontory that in after time shall bear the name of the son of Sisyphus, and the famous shrine of the maiden Longatis, where Helorus empties his chilly stream." (Lycophron 1921, pp. 406–407).

πλαγκτοὶ κατοικήσουσιν, ἣν πέριξ κλύδων

ἔμπλην Παχύνου Σικανὸς προσμάσσεται,

1030τοῦ Σισυφείου παιδὸς ὀχθηρὰν ἄκραν

ἐπώνυμόν ποθ᾽ ὑστέρῳ χρόνῳ γράφων

κλεινόν θ᾽ ἵδρυμα παρθένου Λογγάτιδος,

Ἕλωρος ἔνθα ψυχρὸν ἐκβάλλει ποτόν, - This confusion between Malta and Mljet also recurs in ancient references to the site of the shipwreck of St. Paul recounted in the Acts of the Apostles.

- πρόκειται δὲ τοῦ Παχύνου Μελίτη, ὅθεν τὰ κυνίδια ἃ καλοῦσι Μελιταῖα καὶ Γαῦδος, ὀγδοήκοντα καὶ ὀκτὼ μίλια τῆς ἄκρας ἀμφότεραι διέχουσαι: "Off Pachynus lies Melita, whence come the little dogs called Melitaean, and Gaudos, both eighty-eight miles distant from the Cape."

- καὶ κυναρίου δὲ Μελιταίου τελευτήσαντος αὐτῷ μνῆμα ποιῆσαι καὶ στηλίδιον ποιήσας ἐπιγράψαι ΚΛΑΔΟΣ ΜΕΛΙΤΑΙΟΣ: "Or if his little Melitean dog has died, he will put up a little memorial slab, with the inscription, a scion of Melita." Jebb, or his posthumous editor, Sandys, argued that the reference was to the Illyrian Melita, rather than Malta.

- καὶ κυνάρια Μελιταῖα, ἅπερ αὐτοῖς καὶ ἕπεσθαι εἰς τὰ γυμνάσια; οἱ Συβαρῖται ἔχαιρον τοῖς Μελιταίοις κυνιδίοις καὶ ἀνθρώποις οὐκ ἀνθρώποις: "also Melitê lap-dogs. Which accompany them even to the gymnasia..The Sybarites, on the contrary, took delight in Melitê puppies and human beings who were less than human."

- (Gosling 1935, pp. 110–111):

Issa's more full of sport and wanton play

Than that pet sparrow by Catullus sung;

Issa's more pure and cleanly in her way

Than kisses from the amorous turtle's tongue,

Issa more winsome is than any girl

That ever yet entranced a lover's sight;

Issa's more precious than the Indian pearl

Issa's my Publius' favourite and delight.

Her plaintive voice falls sad as one that weeps;

Her master's cares and woes alike she shares;

Softly reclined upon his neck she sleeps,

And scarce to sigh or draw her breath she dares.

Her, lest the day of fate should nothing leave,

In pictured form my Publius has portrayed

Where you so lifelike Issa might perceive.

That not herself a better likeness made,

Issa together with her portrait lay,

Both real or both depicted you would say. - "Huic insulae Strabo nobiles illos, adagio, non minus quam medicinis, canes adscribit, inde Melitaeos dictos, Plinio, & nunc etiam incolis ignotos, tunc forte nascebantur."

- 'Maltese can develop luxating patellas, an inherited condition where one or both of the kneecaps pop in and out of place. Although patellar luxation is not generally considered a painful condition, it may cause the dog to favor one leg and can predispose them to other knee injuries (such as a cranial cruciate ligament tear) and arthritis. Depending on the severity of the luxating patella, surgery may be recommended to prevent further injury and improve your Maltese’s quality of life. Responsible Maltese breeders will screen their puppies for heart abnormalities such as patent ductus arteriosus. PDA is an inherited condition where the ductus arteriosus, the normal opening between the two major blood vessels in the heart that closes shortly after birth, does not close. This condition causes blood to flow improperly and forces the left side of the heart to work harder. This leads to eventual failure of that chamber. Depending on the size of the opening, dogs may show minimal symptoms to severe signs of heart failure.'

Citations

- ^ AISBL 2015.

- ^ Gorman 2021.

- Cutillo 1986, pp. 190, 199.

- MacKinnon & Belanger 2006, p. 43.

- Coren 2006, p. 167.

- ^ Alderton 2010, p. 59.

- Moore 2008, p. 16.

- Johnson 1919, p. 211.

- Busuttil 1969, pp. 205–208.

- Ogden 2007, p. 197.

- ^ Busuttil 1969, p. 205.

- Vella 1995, p. 12.

- Ogden 2007, p. 200.

- Jebb 1909, p. 67,n.36.

- Pliny 1942, p. 114.

- Pfeiffer 1949, p. 404.

- Strabo 1924, pp. 102–103.

- Jebb 1909, pp. 66–67, n.36.

- Athenaeus 1980, pp. 334–335, 336–337.

- Serpell 1996, p. 47.

- Franco 2019, pp. 100–101.

- Blarney & Inglee 1949, p. 622.

- Vioque 2017, p. 410.

- Delgado 2020, pp. 16–17.

- Quintin 1536, p. 24.

- Lytton 1911, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Drury 1903, p. 577.

- Leighton 1910, p. 274.

- ^ Welsh 1882, p. 238.

- Lee 1899, p. 345.

- Stephens 1874, p. 105.

- Welsh 1882, p. 239.

- Welsh 1882, p. 241.

- Welsh 1882, pp. 241–242.

- Various 2010.

- Raymond-Mallock 1907, p. 63.

- Brearley 1984, p. 29.

- AKC 2022.

- Leighton 1910, p. 297.

- Fielheller.

- Kho-Pelfrey 2022.

- Johnstone 2023.

- MSAKC 2022.

- Coren 2006, p. 124.

- McMillan, Kirsten M.; Bielby, Jon; Williams, Carys L.; Upjohn, Melissa M.; Casey, Rachel A.; Christley, Robert M. (1 February 2024). "Longevity of companion dog breeds: those at risk from early death". Scientific Reports. 14 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-50458-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10834484.

- Roccaro, Mariana; Salini, Romolo; Pietra, Marco; Sgorbini, Micaela; Gori, Eleonora; Dondi, Maurizio; Crisi, Paolo E.; Conte, Annamaria; Dalla Villa, Paolo; Podaliri, Michele; Ciaramella, Paolo; Di Palma, Cristina; Passantino, Annamaria; Porciello, Francesco; Gianella, Paola; Guglielmini, Carlo; Alborali, Giovanni L.; Rota Nodari, Sara; Sabatelli, Sonia; Peli, Angelo (2024). "Factors related to longevity and mortality of dogs in Italy". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 225: 106155. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2024.106155. hdl:11585/961937.

Sources

- Aesop (1980) . Manganelli, Giorgio; Valla, Elena Ceva (eds.). Esopo Favole. Rizzoli.

- Alderton, David (2010). The Dog Selector: How to Choose the Right Dog for You. Barron's. ISBN 978-0-764-16365-4.

- Apollonius de Rhodes (1981). Vian, Francis (ed.). Argonautiques. Vol. 3. Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 2-251-10353-8.

- Athenaeus (1980). Gulick, Charles Burton (ed.). Deipnosophistae. Vol. 5. Loeb Classical Library. ISBN 0-434-99274-7.

- Blarney, Edwin Reginald; Inglee, Charles Topping, eds. (1949). The Complete Dog Book. The care, handling, and feeding of dogs; and Pure bred dogs; the recognized breeds and standards. Garden City Publishing Co.

- Brearley, Joan McDonald (1984). The Book of the Maltese. TFH Publications. ISBN 978-0-876-66563-3.

- Breeds by Year Recognized. American Kennel Club. 3 May 2022.

- Busuttil, J. (1969). "The Maltese Dog". Greece & Rome. 16 (2): 205–208. doi:10.1017/S0017383500017058. JSTOR 642850. S2CID 163799376.

- Coren, Stanley (2006). The Intelligence of Dogs. London: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-1-416-50287-6.

- Cutillo, Nicholas (1986). The Complete Maltese. Howell. ISBN 978-0-876-05209-9.

- Delgado, Albert (16 March 2020). "The Maltese dog: a toy for ancient royalty". Times of Malta. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- "Dog Breed Directory: Maltese". Animal Planet. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- Drury, William D. (1903). British Dogs: Their Points, Selection, and Show Preparation (PDF). L. Upcott Gill, Charles Scribner. pp. 575–581.

- Fielheller, Vicki. "Tear Staining". American Maltese Association.

- Franco, Cristiana (2019). "Dogs and Humans in Ancient Greece and Rome: Towards a Definition of Extended Appropriate Interaction". In Sorenson, John; Matsuoka, Atsuko (eds.). Dog's Best Friend?: Rethinking Canid-Human Relations. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-773-55906-6.

- Gorman, James (4 October 2021). "How Old Is the Maltese, Really?". The New York Times.

- Gosling, W. F. (February 1935). "Pets in Classical Times". Greece & Rome. 4 (11): 109–113. doi:10.1017/S0017383500003144. JSTOR 640982. S2CID 162223203.

- Hornblower, Simon (2015). Lycophron Alexandra. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-57670-8.

- Jebb, R. C. (1909) . Sandys, J. E. (ed.). The Characters of Theophrastus (PDF). Macmillan.

- Johnson, Helen M. (19 May 1919). "The Portrayal of the Dog on Greek Vases". The Classical Weekly. 12 (27): 209–213. doi:10.2307/4387846. JSTOR 4387846.

- Johnstone, Gemma (7 December 2023). "Does a Completely Hypoallergenic Dog Exist?". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- Kho-Pelfrey, Teresa (17 October 2022). "Maltese". Pet MD. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- Lee, Rawden B. (1899). Modern Dogs (Non-Sporting Division), including Toy, Pet, Fancy, and Ladies' Dogs (PDF) (3rd ed.). H. Cox – via Internet Archive.

- Leighton, Robert (1910). Dogs and all about them (PDF). Cassell and Company. pp. 296–300.

- Lycophron (1921). Mair, A.W. (ed.). Callimachus, Lycophron, Aratus. Loeb Classical Library.

- Lytton, Mrs Neville (1911). Toy Dogs and Their Ancestors. New York: D. Appleton & Company – via BHL.

- MacKinnon, Michael; Belanger, Kyle (2006). "Sickness and in Health: Care for an Arthritic Maltese Dog from the Roman Cemetery of Yasmina, Carthage, Tunisia". In Snyder, Lynn M.; Moore, Elizabeth A. (eds.). Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction: Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology, Durham, August 2002. Oxbow Books. pp. 38–43. ISBN 978-1-785-70399-7.

- "Maltese" (PDF). Thuin, Belgium: Fédération Cynologique Internationale (AISBL). 17 December 2015.

- Moore, Mary B. (2008). "The Hegesiboulos Cup". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 43: 11–37. doi:10.1086/met.43.25699084. JSTOR 25699084. S2CID 192949602.

- Ogden, Daniel (2007). In Search of the Sorcerer's Apprentice: The traditional tales of Lucian's Lover of Lies. ISD LLC. ISBN 978-1-914-53510-9.

- "Pet Information: The Maltese". Manila Standard/American Kennel Club. 5 March 2022.

- Pfeiffer, Rudolf (1949). Callimachus. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814115-7.

- Pliny (1942). Rackham, Harris (ed.). Natural History. Vol. 2. Loeb Classical Library. ISBN 0-674-99388-8.

- Quintin, Jean (1536). Insulae Melitae descriptio ex commentariis rerum quotidianarum. Lyon: Sebastian Gryphius.

- Raymond-Mallock, Lilian C. (1907). The Up-to-date Toy Dog: The History, Points and Standards of English Toy Spaniels, Japanese Spaniels, Pomeranians, Toy Terriers, Pugs, Pekinese, Griffon Bruxellois, Maltese and Italian Greyhounds. Battle Creek, Michigan: The Dogdom Publishing Company – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- Serpell, James (1996). In the company of animals: a study of human-animal relationships. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57779-3.

- Stephens, Frederic George (1874). Memoirs of Sir Edwin Landseer: A Sketch of the Life of the Artist, Illustrated with Reproductions of Twenty-four of His Most Popular Works. George Bell.

- Strabo (1924). Jones, Horace Leonard (ed.). The Geography of Strabo. Loeb Classical Library. ISBN 978-0-674-99201-6.

- Trantalidou, Katerina (2006). "Companions from the Oldest Times: Dogs in Ancient Greek Literature, Iconography and Osteological Testimony". In Snyder, Lynn M.; Moore, Elizabeth A. (eds.). Dogs and People in Social, Working, Economic or Symbolic Interaction: Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology, Durham, August 2002. Oxbow Books. pp. 96–120. ISBN 978-1-785-70399-7 – via ResearchGate.

- Various (2010). The Maltese Dog-A Complete Anthology of the Dog 1860-1940. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1-445-52750-5.

- Vella, Horatio C. R. (September 1995). "The island of Gozo in classical texts" (PDF). Occasional Papers on Islands and Small States. 13. Islands and Small States Institute, Malta: 1–40.

- Vioque, Guillermo Galán (2017). Martial, Book VII. A Commentary. Translated by J. J. Zoltowsky. BRILL. ISBN 978-9-004-35097-7.

- Welsh, J. H. (1882). The dogs of the British Islands, being a series of articles on the points of their various breeds, and the treatment of the diseases to which they are subject (PDF) (4th ed.). H. Cox. pp. 238–242.

- White, Sheila; Hornblower, Simon (2012). "Pets". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-54556-8.

External links

| Dog breeds of Italy | |

|---|---|

| Hounds | |

| Gundogs | |

| Pastoral dogs | |

| Mastiffs | |

| Miscellaneous | |