| Revision as of 10:39, 14 November 2005 editMillosh (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,339 edits →Notes: link to the permission← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:51, 5 December 2024 edit undoInternetArchiveBot (talk | contribs)Bots, Pending changes reviewers5,388,154 edits Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead.) #IABot (v2.0.9.5) (Pancho507 - 22008 | ||

| (575 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Albanian poet and writer}} | |||

| {{cleanup}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2014}} | |||

| {{Infobox writer | |||

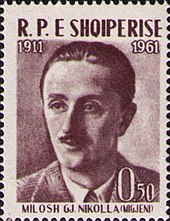

| | name = Migjeni | |||

| | pseudonym = Migjeni | |||

| | image = Migjeni (portrait).jpg | |||

| | image_size = | |||

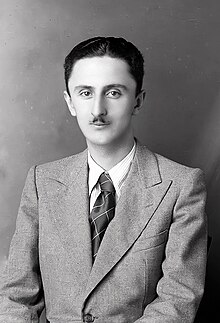

| | caption = Portrait of Migjeni, photographed by ] | |||

| | birth_name = Millosh Gjergj Nikolla | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1911|10|13|df=y}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] (modern ]) | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1938|08|26|1911|10|13|df=y}} | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | occupation = {{hlist|Poet|translator|writer}} | |||

| | alma_mater = | |||

| | language = {{hlist|]|]|]|]|]|]}}{{sfn|Pipa|1978|p=134}} | |||

| | genre = {{hlist|]}} | |||

| | movement = | |||

| | spouse = | |||

| | children = | |||

| | relations = | |||

| | awards = ] People's Teacher | |||

| | signature = Migjeni (nënshkrim).svg | |||

| | signature_alt = Signature of Migjeni | |||

| | signature_size = 115px | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Millosh Gjergj Nikolla''' ({{IPA-sq|miˈɫoʃ ɟɛˈrɟ niˈkoɫa}}; 13 October 1911{{snds}}26 August 1938), commonly known by the ] ] '''Migjeni''', was an ] poet and writer, considered one of the most important of the 20th century. After his death, he was recognized as one of the main influential writers of interwar ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Millosh Gjergj Nikolla''' (or ''Miloš Đoka Nikolić''; ], ] - ], ]) was born in ], ] to a ] family originally from ]. He would become one of the leading figures in Albanian literature. | |||

| Migjeni is considered to have shifted from ] ] to ] during his lifetime. He wrote about the poverty of the years he lived in, with writings such as "Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread", "The Killing Beauty", "Forbidden Apple", "The Corn Legend", "Would You Like Some Charcoal?" etc., severely conveyed the indifference of the wealthy classes to the suffering of the people. | |||

| Migjeni attended elementary school in Shkodër at the ] school there and later at St. John's ] Seminary in ] (Bitolj/Manastir), then Kingdom of ] (now ]). There he studied ], ] ] and ] and read literature written in those languages. On his return to Albania, he gave up his intended career as a priest to become a school teacher in ], a Serbian village a few miles from Shkodër. He began writing verse and prose sketches in ], under pen name Migjeni, an acronym of Millosh Gjergj Nikolla. | |||

| The proliferation of his creativity gained a special momentum after ], when the ] took over the full publication of works, which in the 1930s had been partially unpublished. | |||

| Having contracted tuberculosis, which was then endemic in Albania, he went for treatment to ] in northern ] where his sister ] was studying mathematics. After some time in a sanatorium there, he was transferred to the ] in ] where he died at the age of twenty-six. | |||

| == Biography == | |||

| During the ], the position of the ] deteriorated as ] schools were closed down by ]. Thus, the author had to Albanize his name and chose the nom-de-plume Mi-Gje-Ni in order to preserve his heritage. The ] was formed by the first two letters each of his first name, patronymic and last name. The ] equivalent 'đ' ('']''ђ') of Albanian 'gj' is one letter. | |||

| Migjeni was born on 13 October 1911 in the town of ] at the southeastern coast of ].{{sfn|Elsie|2005|p=138}}{{sfn|Pipa|1978|p=134}} | |||

| ] | |||

| His slender volume of verse (thirty-five poems) entitled ] (Free Verse) was printed by ] in ] in ], but was banned by the authorities. The second edition, published in ], was missing two old poems ''Parathanja e parathanjeve'' (Preface of prefaces) and ''Blasfemi'' (Blasphemy) that were deemed offensive, but it did include eight new ones. The main theme of Migjeni was misery and suffering, a reflection of the life he saw and lived. | |||

| His surname derived from his grandfather Nikolla, who hailed from the region of ] from where he moved to Shkodër in the late 19th century where he practiced the trade of a bricklayer and later married Stake Milani from ], Montenegro, with whom he had two sons: Gjergj (Migjeni's father) and Kristo.{{sfn|Demo|2011}}{{sfn|Luarasi|Luarasi|2003|p=?}} His grandfather was one of the signatories of the congress ] of the ] in 1922. His mother Sofia Kokoshi{{sfn|Polet|2002|p=710}} (d. 1916), a native of ],<ref name="tre shoke">{{cite web |title=Tre "shokë": Migjeni, Pano e Dritëroi |url=http://www.mapo.al/2014/10/tre-shoke-migjeni-pano-e-dritero/ |website=mapo |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150104024547/http://www.mapo.al/2014/10/tre-shoke-migjeni-pano-e-dritero/ |archive-date=4 January 2015 |date=4 January 2015}}</ref> was educated at the ], run by Italian nuns.{{sfn|Luarasi|Luarasi|2003|p=?}} His maternal uncle Jovan Kokoshi taught at the Orthodox seminary in Bitola.<ref name="tre shoke" /> Milosh had a brother that died in infancy, and four sisters: Lenka, Jovanka, Cvetka and Olga.{{sfn|Demo|2011}} | |||

| With Migjeni, contemporary Albanian poetry begins its course. Migjeni, pen name of Millosh Gjergj Nikolla, was born in Shkodra. His father, Gjergj Nikolla (1872-1924), came from an Orthodox family of Dibran origin and owned a bar there. As a boy, he attended a Serbian Orthodox elementary school in Shkodra and from 1923 to 1925 a secondary school in Bar (Tivar) on the Montenegrin coast, where his eldest sister, Lenka, had moved. In the autumn of 1925, when he was fourteen, he obtained a scholarship to attend a secondary school in Monastir (Bitola) in southern Macedonia. This ethnically diverse town, not far from the Greek border, must have held a certain fascination for the young lad from distant Shkodra, since he came into contact there not only with Albanians from different parts of the Balkans, but also with Macedonian, Serb, Aromunian, Turkish and Greek students. Being of Slavic origin himself, he was not confined by narrow-minded nationalist perspectives and was to become one of the very few Albanian authors to bridge the cultural chasm separating the Albanians and Serbs. In Monastir he studied Old Church Slavonic, Russian, Greek, Latin and French. Graduating from school in 1927, he entered the Orthodox Seminary of St. John the Theologian, also in Monastir, where, despite incipient health problems, he continued his training and studies until June 1932. He read as many books as he could get his hands on: Russian, Serbian and French literature in particular, which were more to his tastes than theology. His years in Monastir confronted him with the dichotomy of East and West, with the Slavic soul of Holy Mother Russia and of the southern Slavs, which he encountered in the works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky , Ivan Turgenev , Lev Tolstoy , Nikolay Gogol and Maksim Gorky , and with socially critical authors of the West from Jean-Jacques Rousseau , Friedrich Schiller , Stendhal and Emile Zola to Upton Sinclair , Jack London and Ben Traven . | |||

| Some scholars think that Migjeni had ] origin<ref>{{cite book|last1=Vickers|first1=Miranda|last2=Pettifer|first2=James|year=1997|title=Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity|publisher=C. Hurst & Co.|location=London, England|isbn=978-1-85065-290-8|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mnTCPH_ZGW4C}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Bahun|first=Sanja|editor1-last=Wollaeger|editor1-first=Mark|editor2-last=Eatough|editor2-first=Matt|year=2013|title=The Oxford Handbook of Global Modernisms|chapter=The Balkans Uncovered: Toward Historie Croisée of Modernism|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford, England|isbn=978-0-19932-470-5|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hBg1DQAAQBAJ}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hBg1DQAAQBAJ&dq=migjeni+serb&pg=PA32|isbn=978-0-19-932470-5|title=The Oxford Handbook of Global Modernisms|date=October 2013|publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> further speculating that his first language was ].<ref>{{cite book|editor1-last=Ersoy|editor1-first=Ahmet|editor2-last=Górny|editor2-first=Maciej|editor3-last=Kechriotis|editor3-first=Vangelis|year=2010|title=Modernism – Representations of National Culture|volume=3|issue=2|chapter=Millosh Gjergj Nikolla: We, the Sons of the New Age; The Highlander Recital|publisher=Central European University Press|location=Budapest, Hungary|isbn=978-9-63732-664-6|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OAWTxcwvsLwC}}</ref> Migjeni's cousin Angjelina Ceka Luarasi stated in her book ''Migjeni–Vepra'' that Migjeni was of Albanian and not of any Slavic origin and Migjeni spoke only Albanian as his mother tongue and later learned to speak a Slavic language while growing up.<ref name="CekaLuarasi2003" /> She states that the family is descended from the Nikolla family from ] in the Upper Reka region and the Kokoshi family.<ref name="CekaLuarasi2003" /> Angjelina maintained that the family used many Slavic names because of their Orthodox faith.<ref name="CekaLuarasi2003">{{cite book|author1=Angjelina Ceka Luarasi|author2=Skender Luarasi|title=Migjeni–Vepra|publisher=Cetis Tirana|year=2003|pages=7–8|quote= Është shkruar se nuk ishte shqiptar dhe se familja e tij kishte origjinë sllave, duke injoruar kështu faktet e paraqitura në biografinë e Skënder Luarasit, që dëshmojnë gjakun shqiptar të poetit nga familja dibrane e Nikollave dhe ajo Shkodrane e Kokoshëve.......gjyshi i tij vinte nga Nikollat e Dibrës......emrat me tingëllim sllav, duke përfshirë edhe atë të pagëzimit të Migjenit dhe të motrave të tij, nuk dëshmojnë më shumë se sa përkatësinë në komunitetin ortodoks të Shkodrës...... të ndikuar në atë kohë nga kisha fqinje malazeze.}}</ref> | |||

| On his return to Shkodra in 1932, after failing to win a scholarship to study in the ‘wonderful West,’ he decided to take up a teaching career rather than join the priesthood for which he had been trained. On 23 April 1933, he was appointed teacher of Albanian at a school in the Serb village of Vraka, seven kilometres from Shkodra. It was during this period that he also began writing prose sketches and verse which reflect the life and anguish of an intellectual in what certainly was and has remained the most backward region of Europe. In May 1934 his first short prose piece, Sokrat i vuejtun a po derr i kënaqun (Suffering Socrates or the satisfied pig), was published in the periodical Illyria, under his new pen name Migjeni, an acronym of Millosh Gjergj Nikolla. Soon though, in the summer of 1935, the twenty-three-year-old Migjeni fell seriously ill with tuberculosis, which he had contracted earlier. He journeyed to Athens in July of that year in hope of obtaining treatment for the disease which was endemic on the marshy coastal plains of Albania at the time, but returned to Shkodra a month later with no improvement in his condition. In the autumn of 1935, he transferred for a year to a school in Shkodra itself and, again in the periodical Illyria, began publishing his first epoch-making poems. | |||

| He attended an Orthodox elementary school in Scutari.{{sfn|Elsie|2012|p=308}} From 1923 to 1925, he attended a secondary school in ] (in former ]), where his sister Lenka had moved.{{sfn|Elsie|2012|p=308}} At 14 years of age, in autumn 1925, he received a scholarship to attend secondary school in ] (also in former Yugoslavia),{{sfn|Elsie|2012|p=308}} from where he graduated in 1927,{{sfn|Elsie|2005}} then entered the Orthodox seminary of St. John the Theologian. He studied ], Russian, Greek, Latin and French. He continued his training and studies until June 1932. | |||

| In a letter of 12 January 1936 written to translator Skënder Luarasi (1900-1982) in Tirana, Migjeni announced, "I am about to send my songs to press. Since, while you were here, you promised that you would take charge of speaking to some publisher, ‘Gutemberg’ for instance, I would now like to remind you of this promise, informing you that I am ready." Two days later, Migjeni received the transfer he had earlier requested to the mountain village of Puka and on 18 April 1936 began his activities as the headmaster of the run-down school there. | |||

| His name was written ''Milosh Nikoliç'' in the passport dated 17 June 1932, then changed into ''Millosh Nikolla'' in the decree of appointment as teacher signed by Minister of Education Mirash Ivanaj dated 18 May 1933.{{sfn|Demo|2011}}{{sfn|Demo|2011}} In the revised birth certificate dated to 26 January 1937, his name is spelt ''Millosh Nikolla''.{{sfn|Demo|2011}} | |||

| The clear mountain air did him some good, but the poverty and misery of the mountain tribes in and around Puka were even more overwhelming than that which he had experienced among the inhabitants of the coastal plain. Many of the children came to school barefoot and hungry, and teaching was interrupted for long periods of time because of outbreaks of contagious diseases, such as measles and mumps. After eighteen hard months in the mountains, the consumptive poet was obliged to put an end to his career as a teacher and as a writer, and to seek medical treatment in Turin in northern Italy where his sister Ollga was studying mathematics. He set out from Shkodra on 20 December 1937 and arrived in Turin before Christmas day. There he had hoped, after recovery, to register and study at the Faculty of Arts. The breakthrough in the treatment of tuberculosis, however, was to come a decade too late for Migjeni. After five months at San Luigi sanatorium near Turin, Migjeni was transferred to the Waldensian hospital in Torre Pellice where he died on 26 August 1938. His demise at the age of twenty-six was a tragic loss for modern Albanian letters. | |||

| == Career == | |||

| Migjeni made a promising start as a prose writer. He is the author of about twenty-four short prose sketches which he published in periodicals for the most part between the spring of 1933 and the spring of 1938. Ranging from one to five pages in length, these pieces are too short to constitute tales or short stories. Although he approached new themes with unprecedented cynicism and force, his sketches cannot all be considered great works of art from a literary point of view. | |||

| === Teaching, publishing and deteriorating health === | |||

| ] | |||

| It is thus far more as a poet that Migjeni made his mark on Albanian literature and culture, though he did so posthumously. He possessed all the prerequisites for being a great poet. He had an inquisitive mind, a depressive pessimistic nature and a repressed sexuality. Though his verse production was no more voluminous than his prose, his success in the field of poetry was no less than spectacular in Albania at the time. | |||

| On 23 April 1933, he was appointed teacher at a school in the village of Vrakë or<ref name="Admiralty1920">{{cite book|author=Great Britain. Admiralty|title=A Handbook of Serbia, Montenegro, Albania and Adjacent Parts of Greece|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3KVBAAAAYAAJ|year=1920|publisher=H.M. Stationery Office|page=403}} {{blockquote|The following villages are in whole or part occupied by Orthodox Serbs — Brch, Borich, Basits, Vraka, Sterbets, Kadrum. Farming is the chief occupation.}}</ref> ],<ref name="Elsie2005-132">{{cite book|author=Robert Elsie|title=Albanian Literature: A Short History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ox3Wx1Nl_2MC&pg=PA132|year=2005|publisher=I.B. Tauris|isbn=978-1-84511-031-4|pages=132–}}</ref> seven kilometers from Shkokër, until 1934 when the school closed. It was during this period that he also began writing prose sketches and verses.<ref name="Elsie2005-132"/> | |||

| Migjeni’s only volume of verse, Vargjet e lira, Tirana 1944 (Free verse), was composed over a three-year period from 1933 to 1935. A first edition of this slender and yet revolutionary collection, a total of thirty-five poems, was printed by the Gutemberg Press in Tirana in 1936 but was immediately banned by the authorities and never circulated. The second edition of 1944, undertaken by scholar Kostaç Cipo (1892-1952) and the poet’s sister Ollga, was more successful. It nonetheless omitted two poems, Parathanja e parathanjeve (Preface of prefaces) and Blasfemi (Blasphemy), which the publisher, Ismail Mal’Osmani, felt might offend the Church. The 1944 edition did, however, include eight other poems composed after the first edition had already gone to press. | |||

| In May 1934, his first short prose piece, ''Sokrat i vuejtun apo derr i kënaqun'' (Suffering Socrates or a satisfied pig), was published in the periodical ''Illyria'',<ref>{{cite magazine|magazine=Jeta e re |title=Review |issue=10 |date=1958 |page=469 |language=Albanian |quote=Me botimin e prodhimit të parë letrar, „Sokrat i vuejtun apo derr i kënaqun?“ n'Illyria të 27 majit 1934, fillon ritmi i shpejtë i aktivitetit letrar të Migjenit.}}</ref> under his new pen name ''Migjeni'', an acronym of Millosh Gjergj Nikolla. In the summer of 1935, Migjeni fell seriously ill with tuberculosis, which he had contracted earlier.<ref name="Elsie2010">{{cite book |last1=Elsie |first1=Robert |title=Historical Dictionary of Albania |date=2010 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |isbn=9780810873803 |pages=301–302 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=haFlGXIg8uoC&pg=PA301}}</ref> He journeyed to ], ] in July of that year in hope of obtaining treatment for the disease which was endemic on the marshy coastal plains of Albania at the time but returned to Shkodra a month later with no improvement in his condition. In the autumn of 1935, he transferred for a year to a school in Shkodra itself and, again in the periodical Illyria, began publishing his first epoch-making poems. | |||

| The main theme of ‘Free verse,’ as with Migjeni’s prose, is misery and suffering. It is a poetry of acute social awareness and despair. Previous generations of poets had sung the beauties of the Albanian mountains and the sacred traditions of the nation, whereas Migjeni now opened his eyes to the harsh realities of life, to the appalling level of misery, disease and poverty he discovered all around him. He was a poet of despair who saw no way out, who cherished no hope that anything but death could put an end to suffering. "I suffer with the child whose father cannot buy him a toy. I suffer with the young man who burns with unslaked sexual desire. I suffer with the middle-aged man drowning in the apathy of life. I suffer with the old man who trembles at the prospect of death. I suffer with the peasant struggling with the soil. I suffer with the worker crushed by iron. I suffer with the sick suffering from all the diseases of the world... I suffer with man." Typical of the suffering and of the futility of human endeavour for Migjeni is Rezignata (Resignation), a poem in the longest cycle of the collection, Kangët e mjerimit (Songs of poverty). Here the poet paints a grim portrait of our earthly existence: sombre nights, tears, smoke, thorns and mud. Rarely does a breath of fresh air or a vision of nature seep through the gloom. When nature does occur in the verse of Migjeni, then of course it is autumn. | |||

| In a letter of 12 January 1936 written to translator ] (1900–1982) in ], Migjeni announced, "I am about to send my songs to press. Since, while you were here, you promised that you would take charge of speaking to some publisher, 'Gutemberg' for instance, I would now like to remind you of this promise, informing you that I am ready." Migjeni later received the transfer he had earlier requested to the mountain village of ] and in April 1936 began his activities as the headmaster of the run-down school there.<ref name="Elsie2010" /> | |||

| If there is no hope, there are at least suffocated desires and wishes. Some poems, such as Të birtë e shekullit të ri (The sons of the new age), Zgjimi (Awakening), Kanga e rinis (Song of youth) and Kanga e të burgosunit (The prisoner’s song), are assertively declamatory in a left-wing revolutionary manner. Here we discover Migjeni as a precursor of socialist verse or rather, in fact, as the zenith of genuine socialist verse in Albanian letters, long before the so-called liberation and socialist period from 1944 to 1990. Migjeni was, nonetheless, not a socialist or revolutionary poet in the political sense, despite the indignation and the occasional clenched fist he shows us. For this, he lacked the optimism as well as any sense of political commitment and activity. He was a product of the thirties, an age in which Albanian intellectuals, including Migjeni, were particularly fascinated by the West and in which, in Western Europe itself, the rival ideologies of communism and fascism were colliding for the first time in the Spanish Civil War. Migjeni was not entirely uninfluenced by the nascent philosophy of the right either. In Të lindet njeriu (May the man be born) and particularly, in the Nietzschean dithyramb Trajtat e Mbinjeriut (The shape of the Superman), a strangled, crushed will transforms itself into "ardent desire for a new genius," for the Superman to come. To a Trotskyite friend, André Stefi, who had warned him that the communists would not forgive for such poems, Migjeni replied, "My work has a combative character, but for practical reasons, and taking into account our particular conditions, I must manoeuvre in disguise. I cannot explain these things to the groups, they must understand them for themselves. The publication of my works is dictated by the necessities of the social situation through which we are passing. As for myself, I consider my work to be a contribution to the union of the groups. André, my work will be achieved if I manage to live a little longer." | |||

| ] in ].]] | |||

| Part of the ‘establishment’ which he felt was oblivious to and indeed responsible for the sufferings of humanity was the Church. Migjeni’s religious education and his training for the Orthodox priesthood seem to have been entirely counterproductive, for he cherished neither an attachment to religion nor any particularly fond sentiments for the organized Church. God for Migjeni was a giant with granite fists crushing the will of man. Evidence of the repulsion he felt towards god and the Church are to be found in the two poems missing from the 1944 edition, Parathania e parathanieve (Preface of prefaces) with its cry of desperation "God! Where are you?", and Blasfemi (Blasphemy). | |||

| The clear mountain air did him some good, but the poverty and misery of the ] in and around Puka were even more overwhelming than that which he had experienced among the inhabitants of the coastal plain. Many of the children came to school barefoot and hungry, and teaching was interrupted for long periods because of outbreaks of contagious diseases, such as ] and ]. After eighteen difficult months in the mountains, he was obliged to put an end to his career in order to seek medical treatment in ] in Northern Italy where his sister Ollga was studying mathematics.<ref name="Elsie2010" /> He arrived in Turin before Christmas Day where he hoped, after recovery, to register and study at the Faculty of Arts. The breakthrough in the treatment of tuberculosis, however, would come a decade later. After five months at San Luigi Sanatorium near Turin, Migjeni was transferred to the Waldensian hospital in ] where he died on 26 August 1938. ] writes that "his demise at the age of twenty-six was a tragic loss for the modern Albanian letters".<ref name="Elsie2010" /> | |||

| In Kanga skandaloze (Scandalous song), Migjeni expresses a morbid attraction to a pale nun and at the same time his defiance and rejection of her world. This poem is one which helps throw some light not only on Migjeni’s attitude to religion but also on one of the more fascinating and least studied aspects in the life of the poet, his repressed heterosexuality. | |||

| The author had chosen the nom-de-plume Mi-Gje-Ni, an acronym formed by the first two letters each of his first name, patronymic and last name. | |||

| Eroticism has certainly never been a prominent feature of Albanian literature at any period and one would be hard pressed to name any Albanian author who has expressed his intimate impulses and desires in verse or prose. Migjeni comes closest, though in an unwitting manner. It is generally assumed that the poet remained a virgin until his untimely death at the age of twenty-six. His verse and his prose abound with the figures of women, many of them unhappy prostitutes, for whom Migjeni betrays both pity and an open sexual interest. It is the tearful eyes and the red lips which catch his attention; the rest of the body is rarely described. For Migjeni, sex too means suffering. Passion and rapturous desire are ubiquitous in his verse, but equally present is the spectre of physical intimacy portrayed in terms of disgust and sorrow. It is but one of the many bestial faces of misery described in the 105-line Poema e mjerimit (Poem of poverty). | |||

| === Poetry === | |||

| Though he did not publish a single book during his lifetime, Migjeni’s works, which circulated privately and in the press of the period, were an immediate success. Migjeni paved the way for a modern literature in Albania. This literature was, however, soon to be nipped in the bud. Indeed the very year of the publication of ‘Free Verse’ saw the victory of Stalinism in Albania and the proclamation of the People’s Republic. | |||

| Migjeni made his debut as a ] writer, authoring about twenty-four short prose ] which he published in periodicals mainly between 1933 and 1938.<ref name="Elsie2010" /> It was Migjeni's poetry however that left a mark in Albanian culture and literature.<ref name="Elsie2010" /> His slender volume of verse (thirty-five poems) entitled ''Vargjet e Lira'' ("Free Verse") was printed by ''Gutenberg Press'' Publisher in ] in 1936, but was banned by government censorship.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pynsent |first1=Robert B. |last2=Kanikova |first2=Sonia I. |title=Reader's Encyclopedia of Eastern European Literature |date=1993 |publisher=HarperCollins |isbn=9780062700070 |page=262 |quote=His volume of poetry, Vargjet e lira (Free verse), went to press in 1936, but was immediately confiscated by the authorities; a second printing of it did appear in 1944.}}</ref> The second edition, published in 1944, was missing two old poems ''Parathanja e parathanjeve'' ("Preface of prefaces") and ''Blasfemi'' ("Blasphemy") that were deemed offensive,<ref>{{cite journal |title=Migjeni dhe epoka e tij |journal=Studime Filologjike |date=1988 |volume=42 |issue=3–4 |page=7 |language=Albanian |quote=Migjeni tregoi pasojat rrënimtare të papunësisë për familjet ... “ Parathanja e parathanjeve“ dhe « Blasfemi » u hoqën prej botimit të “ Vargjeve të lira “ të vitit 1944 dhe « Blasfemi » u hoqën prej botimit të “ Vargjeve të lira “ të vitit 1944}}</ref> but it did include eight new ones. The main theme of Migjeni was misery and suffering, a reflection of the life he saw and lived which was evident in ''Free verse''.<ref name="Elsie2010" /> | |||

| Many have speculated as to what contribution Migjeni might have made to Albanian letters had he managed to live longer. The question remains highly hypothetical, for this individualist voice of genuine social protest would no doubt have suffered the same fate as most Albanian writers of talent in the late forties, i.e. internment, imprisonment or execution. His early demise has at least preserved the writer for us undefiled. | |||

| {{Quote box|width=410px|quoted=true |bgcolor=#FFFFF0|salign=right|quote= | |||

| The fact that Migjeni did perish so young makes it difficult to provide a critical assessment of his work. Though generally admired, Migjeni is not without critics. Some have been disappointed by his prose, nor is the range of his verse sufficient to allow us to acclaim him as a universal poet. Albanian-American scholar Arshi Pipa (1920-1997) has questioned his very mastery of the Albanian language, asserting: "Born Albanian to a family of Slavic origin, then educated in a Slavic cultural milieu, he made contact again with Albania and the Albanian language and culture as an adult. The language he spoke at home was Serbo-Croatian, and at the seminary he learned Russian. He did not know Albanian well. His texts swarm with spelling mistakes, even elementary ones, and his syntax is far from being typically Albanian. What is true of Italo Svevo’s Italian is even truer of Migjeni’s Albanian." | |||

| <poem> | |||

| '''Resignation''' | |||

| We show our consolation only in tears... | |||

| Post-war Stalinist critics in Albania rather superficially proclaimed Migjeni as the precursor of socialist realism though they were unable to deal with many aspects of his life and work, in particular his Schopenhauerian pessimism, his sympathies with the West, his repressed sexuality, and the Nietzschean element in Trajtat e Mbinjeriut (The shape of the Superman), a poem conveniently left out of some post-war editions of his verse. While such critics have delighted in viewing Migjeni as a product of ‘pre-liberation’ Zogist Albania, it has become painfully evident that the poet’s ‘songs unsung,’ after half a century of communist dictatorship in Albania, are now more compelling than ever. | |||

| Our inheritance from all these years | |||

| is misery... because within the womb | |||

| of the Universe our world is a tomb, | |||

| where mankind are condemned to sneak like snakes, | |||

| and their will as if squeezed in the fist of a giant breaks. | |||

| - One eye glittering with distilled drops of the deepest pain | |||

| glimmers from far across the vale of tears, | |||

| and sometimes an instinctive pulse of frustrated thought | |||

| flashes out across the spheres | |||

| seeking an outlet for anger overwrought. | |||

| But the head sags, and the sorrowing eye is hid, | |||

| and a solitary tear squeezes through the lid, | |||

| rolls down and off the face, a single drop of rain; | |||

| and from the tiny raindrop of that tear, a man is born again. | |||

| And each such man must take his fate in his own hands, | |||

| hoping for the smallest victory, and seek out distant lands; | |||

| where all the roads are laid with thorns and on every side walled in | |||

| by gravestones all besmeared with tears and lunatics who, silent, grin. | |||

| </poem>|source = (trans. Wilton)<ref>https://robertwilton.com/ {{Bare URL inline|date=August 2024}}</ref>}} | |||

| According to Elsie, Migjeni's poetry was "of acute social awareness and despair. Previous generations of poets had sung the beauties of the Albanian mountains and the sacred traditions of the nation, whereas Migjeni now opened his eyes to the harsh realities of life, to the appalling level of misery, disease, and poverty he discovered all around him."<ref name="Elsie2010" /> He was a poet of despair who saw no way out, who cherished no hope that anything but death could put an end to suffering. ''"I suffer from the child whose father cannot buy him a toy. I suffer from a young man who burns with unslaked sexual desire. I suffer from the middle-aged man drowning in the apathy of life. I suffer from the old man who trembles at the prospect of death. I suffer from the peasant struggling with the soil. I suffer from the worker crushed by iron. I suffer from the sick suffering from all the diseases of the world... I suffer with man."'' Typical of the suffering and of the futility of human endeavor for Migjeni is ''Rezignata'' ("Resignation"), a poem in the longest cycle of the collection, ''Kangët e mjerimit'' ("Songs of poverty"). In it, he paints a grim portrait of earthly existence: somber nights, tears, smoke, thorns and mud. Rarely does a breath of fresh air or a vision of nature seep through the gloom. When nature does occur in the verse of Migjeni, then, it is autumn.{{citation needed|date=April 2022}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| *From the version this article includes the text from the site with explicite permission () to use it under ]. | |||

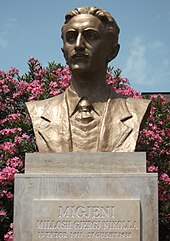

| ] in ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Some poems, such as ''Të birtë e shekullit të ri'' ("The sons of the new age"), ''Zgjimi'' ("Awakening"), ''Kanga e rinis'' ("Song of youth") and ''Kanga e të burgosunit'' ("The prisoner's song"), are assertively declamatory in a left-wing ] manner. In those works, Migjeni gives readers a precursor of socialist verse or rather, in fact, as the zenith of genuine socialist verse in Albanian ], long before the so-called liberation and ] from 1944 to 1990. Migjeni was, nonetheless, not a socialist or revolutionary poet in the political sense, despite the indignation and the occasional clenched fist he shows us. For this, he lacked the ] as well as any sense of political commitment and activity.{{citation needed|date=April 2022}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| He was a product of the 1930s, an age in which Albanian intellectuals, including Migjeni, were particularly fascinated by the West and in which, in Western Europe itself, the rival ideologies of communism and fascism were colliding for the first time in the ]. Migjeni was not entirely uninfluenced by the nascent philosophy of the right either. In ''Të lindet njeriu'' ("May the man be born") and particularly, in the ''Nietzschean dithyramb Trajtat e Mbinjeriut'' ("The shape of the Superman"), a strangled, crushed will transforms itself into "ardent desire for a new genius," for the ] to come. To a ] friend, ], who had warned him that the communists would not forgive for such poems, Migjeni replied, ''"My work has a combative character, but for practical reasons, and taking into account our particular conditions, I must maneuver in disguise. I cannot explain these things to the groups, they must understand them for themselves. The publication of my works is dictated by the necessities of the social situation through which we are passing. As for myself, I consider my work to be a contribution to the union of the groups. André, my work will be achieved if I manage to live a little longer."''{{sfn|Pipa|1978|p=150}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Part of the 'establishment' which he felt was oblivious to the sufferings of humanity was the ]. Migjeni's religious education and his training for the Orthodox priesthood seem to have been entirely counterproductive, for he cherished neither an attachment to religion nor any particularly fond sentiments for the organized Church. God for Migjeni was a giant with granite fists crushing the will of man. Evidence of the repulsion he felt towards God and the Church are to be found in the two poems missing from the 1944 edition, ''Parathania e parathanieve'' ("Preface of prefaces") with its cry of desperation ''"God! Where are you?"'', and ''Blasfemi'' ("Blasphemy").{{citation needed|date=October 2022}} | |||

| In ''Kanga skandaloze'' ("Scandalous song"), Migjeni expresses a ] attraction to a pale nun and at the same time his defiance and rejection of her world. This poem is one which helps throw some light not only on Migjeni's attitude to religion but also on one of the least studied aspects in the life of the poet, his repressed sexuality.{{citation needed|date=October 2022}} | |||

| ] has certainly never been a prominent feature of Albanian literature at any period and one would be hard-pressed to name any Albanian author who has expressed his intimate impulses and desires in verse or prose. Migjenis verse and his prose abound with the figures of women, many of them unhappy prostitutes, for whom Migjeni betrays both pity and open sexual interest. It is the tearful eyes and the red lips which catch his attention; the rest of the body is rarely described. Passion and rapturous desire are ubiquitous in his verse, but equally present is the specter of physical intimacy portrayed in terms of disgust and sorrow. It is but one of the many bestial faces of misery described in the 105-line ''Poema e mjerimit'' ("The poem of the misery").{{citation needed|date=April 2022}} | |||

| == Legacy == | |||

| Regarding his legacy, Elsie writes: "Though Migjeni did not publish a single book during his lifetime, his works, which circulated privately and in the press of the period, were an immediate success. Migjeni paved the way for modern literature in Albania."<ref name="Elsie2010" /> This literature was, however, soon to be nipped in the bud. The very year of the publication of ''Free Verse'' saw the victory of ] in Albania and the proclamation of the People's Republic. | |||

| Many have speculated as to what contribution Migjeni might have made to Albanian letters had he managed to live longer. The question remains highly hypothetical, for this individualist voice of genuine social protest would no doubt have suffered the same fate as most Albanian writers of talent in the late 1940s, i.e. internment, imprisonment or execution. His early demise has at least preserved the writer for us undefiled. | |||

| The fact that Migjeni did perish so young makes it difficult to provide a critical assessment of his work. Though generally admired, Migjeni is not without critics. Some have been disappointed by his prose, nor is the range of his verse sufficient to allow us to acclaim him as a universal poet. | |||

| == See also == | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == Sources == | |||

| {{refbegin|2}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Elsie|first=Robert|title=Albanian Literature: A Short History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ox3Wx1Nl_2MC&pg=PA138|year=2005|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=978-1-84511-031-4|pages=138–}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Elsie|first=Robert|title=A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pgf6GWJxuZgC|year=2012|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=978-1-78076-431-3|pages=308–309}} | |||

| * {{cite web|last=Demo|first=Elsa|title=Migjeni në librin e shtëpisë|date=14 October 2011|publisher=Mapo; Arkiva Lajmeve|url=http://www.arkivalajmeve.com/Migjeni-ne-librin-e-shtepise.1047118413/|access-date=10 December 2014|archive-date=18 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210418171951/http://www.arkivalajmeve.com/Migjeni-ne-librin-e-shtepise.1047118413/|url-status=dead}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Pipa|first=Arshi|title=Albanian literature: social perspectives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pECAAAAAIAAJ|year=1978|publisher=R. Trofenik|isbn=978-3-87828-106-1}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Polet|first=Jean-Claude|title=Auteurs européens du premier XXe siècle: 1. De la drôle de paix à la drôle de guerre (1923-1939)|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eZjXABt_x9wC&pg=PA710|year=2002|publisher=De Boeck Supérieur|isbn=978-2-8041-3580-5|pages=710–711}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| == External links == | |||

| *{{cite web|url=http://www.albanianliterature.net/authors/classical/migjeni/index.html|publisher=albanianliterature.com|title=Authors: Migjeni}}, explicit permission for use under ]. | |||

| *, A bilingual edition | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Luarasi|first=Skender |title=Migjeni: Jeta|year=2002|publisher=Cetis|location=Tirana, Albania|language=Albanian}} | |||

| {{Albanian Literature}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{Subject bar | |||

| |book = | |||

| |portal = | |||

| |commons = y | |||

| |wikt = y | |||

| |wikt-search = Migjeni | |||

| |b = y | |||

| |b-search = Millosh Gjergj Nikolla's Works | |||

| |q = y | |||

| |s = y | |||

| |s-search = Author:Millosh Gjergj Nikolla | |||

| }} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Nikolla, Millosh Gjergj}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:51, 5 December 2024

Albanian poet and writer

| Migjeni | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Migjeni, photographed by Geg Marubi Portrait of Migjeni, photographed by Geg Marubi | |

| Born | Millosh Gjergj Nikolla (1911-10-13)13 October 1911 Shkodër, Ottoman Empire (modern Albania) |

| Died | 26 August 1938(1938-08-26) (aged 26) Torre Pellice, Italy |

| Pen name | Migjeni |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | |

| Genre | |

| Notable awards | |

| Signature | |

| |

Millosh Gjergj Nikolla (Albanian pronunciation: [miˈɫoʃ ɟɛˈrɟ niˈkoɫa]; 13 October 1911 – 26 August 1938), commonly known by the acronym pen name Migjeni, was an Albanian poet and writer, considered one of the most important of the 20th century. After his death, he was recognized as one of the main influential writers of interwar Albanian literature.

Migjeni is considered to have shifted from revolutionary romanticism to critical realism during his lifetime. He wrote about the poverty of the years he lived in, with writings such as "Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread", "The Killing Beauty", "Forbidden Apple", "The Corn Legend", "Would You Like Some Charcoal?" etc., severely conveyed the indifference of the wealthy classes to the suffering of the people.

The proliferation of his creativity gained a special momentum after World War II, when the communist regime took over the full publication of works, which in the 1930s had been partially unpublished.

Biography

Migjeni was born on 13 October 1911 in the town of Shkodër at the southeastern coast of Lake of Shkodër.

His surname derived from his grandfather Nikolla, who hailed from the region of Upper Reka from where he moved to Shkodër in the late 19th century where he practiced the trade of a bricklayer and later married Stake Milani from Kuči, Montenegro, with whom he had two sons: Gjergj (Migjeni's father) and Kristo. His grandfather was one of the signatories of the congress for the establishment of the Albanian Orthodox Church in 1922. His mother Sofia Kokoshi (d. 1916), a native of Kavajë, was educated at the Catholic seminary of Scutari, run by Italian nuns. His maternal uncle Jovan Kokoshi taught at the Orthodox seminary in Bitola. Milosh had a brother that died in infancy, and four sisters: Lenka, Jovanka, Cvetka and Olga.

Some scholars think that Migjeni had Serb origin further speculating that his first language was Serbo-Croatian. Migjeni's cousin Angjelina Ceka Luarasi stated in her book Migjeni–Vepra that Migjeni was of Albanian and not of any Slavic origin and Migjeni spoke only Albanian as his mother tongue and later learned to speak a Slavic language while growing up. She states that the family is descended from the Nikolla family from Debar in the Upper Reka region and the Kokoshi family. Angjelina maintained that the family used many Slavic names because of their Orthodox faith.

He attended an Orthodox elementary school in Scutari. From 1923 to 1925, he attended a secondary school in Bar, Montenegro (in former Yugoslavia), where his sister Lenka had moved. At 14 years of age, in autumn 1925, he received a scholarship to attend secondary school in Monastir (Bitola) (also in former Yugoslavia), from where he graduated in 1927, then entered the Orthodox seminary of St. John the Theologian. He studied Old Church Slavonic, Russian, Greek, Latin and French. He continued his training and studies until June 1932.

His name was written Milosh Nikoliç in the passport dated 17 June 1932, then changed into Millosh Nikolla in the decree of appointment as teacher signed by Minister of Education Mirash Ivanaj dated 18 May 1933. In the revised birth certificate dated to 26 January 1937, his name is spelt Millosh Nikolla.

Career

Teaching, publishing and deteriorating health

On 23 April 1933, he was appointed teacher at a school in the village of Vrakë or Vraka, seven kilometers from Shkokër, until 1934 when the school closed. It was during this period that he also began writing prose sketches and verses.

In May 1934, his first short prose piece, Sokrat i vuejtun apo derr i kënaqun (Suffering Socrates or a satisfied pig), was published in the periodical Illyria, under his new pen name Migjeni, an acronym of Millosh Gjergj Nikolla. In the summer of 1935, Migjeni fell seriously ill with tuberculosis, which he had contracted earlier. He journeyed to Athens, Greece in July of that year in hope of obtaining treatment for the disease which was endemic on the marshy coastal plains of Albania at the time but returned to Shkodra a month later with no improvement in his condition. In the autumn of 1935, he transferred for a year to a school in Shkodra itself and, again in the periodical Illyria, began publishing his first epoch-making poems.

In a letter of 12 January 1936 written to translator Skënder Luarasi (1900–1982) in Tirana, Migjeni announced, "I am about to send my songs to press. Since, while you were here, you promised that you would take charge of speaking to some publisher, 'Gutemberg' for instance, I would now like to remind you of this promise, informing you that I am ready." Migjeni later received the transfer he had earlier requested to the mountain village of Puka and in April 1936 began his activities as the headmaster of the run-down school there.

The clear mountain air did him some good, but the poverty and misery of the mountain people in and around Puka were even more overwhelming than that which he had experienced among the inhabitants of the coastal plain. Many of the children came to school barefoot and hungry, and teaching was interrupted for long periods because of outbreaks of contagious diseases, such as measles and mumps. After eighteen difficult months in the mountains, he was obliged to put an end to his career in order to seek medical treatment in Turin in Northern Italy where his sister Ollga was studying mathematics. He arrived in Turin before Christmas Day where he hoped, after recovery, to register and study at the Faculty of Arts. The breakthrough in the treatment of tuberculosis, however, would come a decade later. After five months at San Luigi Sanatorium near Turin, Migjeni was transferred to the Waldensian hospital in Torre Pellice where he died on 26 August 1938. Robert Elsie writes that "his demise at the age of twenty-six was a tragic loss for the modern Albanian letters".

The author had chosen the nom-de-plume Mi-Gje-Ni, an acronym formed by the first two letters each of his first name, patronymic and last name.

Poetry

Migjeni made his debut as a prose writer, authoring about twenty-four short prose sketches which he published in periodicals mainly between 1933 and 1938. It was Migjeni's poetry however that left a mark in Albanian culture and literature. His slender volume of verse (thirty-five poems) entitled Vargjet e Lira ("Free Verse") was printed by Gutenberg Press Publisher in Tirana in 1936, but was banned by government censorship. The second edition, published in 1944, was missing two old poems Parathanja e parathanjeve ("Preface of prefaces") and Blasfemi ("Blasphemy") that were deemed offensive, but it did include eight new ones. The main theme of Migjeni was misery and suffering, a reflection of the life he saw and lived which was evident in Free verse.

(trans. Wilton)Resignation

We show our consolation only in tears...

Our inheritance from all these years

is misery... because within the womb

of the Universe our world is a tomb,

where mankind are condemned to sneak like snakes,

and their will as if squeezed in the fist of a giant breaks.

- One eye glittering with distilled drops of the deepest pain

glimmers from far across the vale of tears,

and sometimes an instinctive pulse of frustrated thought

flashes out across the spheres

seeking an outlet for anger overwrought.

But the head sags, and the sorrowing eye is hid,

and a solitary tear squeezes through the lid,

rolls down and off the face, a single drop of rain;

and from the tiny raindrop of that tear, a man is born again.

And each such man must take his fate in his own hands,

hoping for the smallest victory, and seek out distant lands;

where all the roads are laid with thorns and on every side walled in

by gravestones all besmeared with tears and lunatics who, silent, grin.

According to Elsie, Migjeni's poetry was "of acute social awareness and despair. Previous generations of poets had sung the beauties of the Albanian mountains and the sacred traditions of the nation, whereas Migjeni now opened his eyes to the harsh realities of life, to the appalling level of misery, disease, and poverty he discovered all around him." He was a poet of despair who saw no way out, who cherished no hope that anything but death could put an end to suffering. "I suffer from the child whose father cannot buy him a toy. I suffer from a young man who burns with unslaked sexual desire. I suffer from the middle-aged man drowning in the apathy of life. I suffer from the old man who trembles at the prospect of death. I suffer from the peasant struggling with the soil. I suffer from the worker crushed by iron. I suffer from the sick suffering from all the diseases of the world... I suffer with man." Typical of the suffering and of the futility of human endeavor for Migjeni is Rezignata ("Resignation"), a poem in the longest cycle of the collection, Kangët e mjerimit ("Songs of poverty"). In it, he paints a grim portrait of earthly existence: somber nights, tears, smoke, thorns and mud. Rarely does a breath of fresh air or a vision of nature seep through the gloom. When nature does occur in the verse of Migjeni, then, it is autumn.

Some poems, such as Të birtë e shekullit të ri ("The sons of the new age"), Zgjimi ("Awakening"), Kanga e rinis ("Song of youth") and Kanga e të burgosunit ("The prisoner's song"), are assertively declamatory in a left-wing revolutionary manner. In those works, Migjeni gives readers a precursor of socialist verse or rather, in fact, as the zenith of genuine socialist verse in Albanian letters, long before the so-called liberation and socialist period from 1944 to 1990. Migjeni was, nonetheless, not a socialist or revolutionary poet in the political sense, despite the indignation and the occasional clenched fist he shows us. For this, he lacked the optimism as well as any sense of political commitment and activity.

He was a product of the 1930s, an age in which Albanian intellectuals, including Migjeni, were particularly fascinated by the West and in which, in Western Europe itself, the rival ideologies of communism and fascism were colliding for the first time in the Spanish Civil War. Migjeni was not entirely uninfluenced by the nascent philosophy of the right either. In Të lindet njeriu ("May the man be born") and particularly, in the Nietzschean dithyramb Trajtat e Mbinjeriut ("The shape of the Superman"), a strangled, crushed will transforms itself into "ardent desire for a new genius," for the Superman to come. To a Trotskyist friend, André Stefi, who had warned him that the communists would not forgive for such poems, Migjeni replied, "My work has a combative character, but for practical reasons, and taking into account our particular conditions, I must maneuver in disguise. I cannot explain these things to the groups, they must understand them for themselves. The publication of my works is dictated by the necessities of the social situation through which we are passing. As for myself, I consider my work to be a contribution to the union of the groups. André, my work will be achieved if I manage to live a little longer."

Part of the 'establishment' which he felt was oblivious to the sufferings of humanity was the Church. Migjeni's religious education and his training for the Orthodox priesthood seem to have been entirely counterproductive, for he cherished neither an attachment to religion nor any particularly fond sentiments for the organized Church. God for Migjeni was a giant with granite fists crushing the will of man. Evidence of the repulsion he felt towards God and the Church are to be found in the two poems missing from the 1944 edition, Parathania e parathanieve ("Preface of prefaces") with its cry of desperation "God! Where are you?", and Blasfemi ("Blasphemy").

In Kanga skandaloze ("Scandalous song"), Migjeni expresses a morbid attraction to a pale nun and at the same time his defiance and rejection of her world. This poem is one which helps throw some light not only on Migjeni's attitude to religion but also on one of the least studied aspects in the life of the poet, his repressed sexuality.

Eroticism has certainly never been a prominent feature of Albanian literature at any period and one would be hard-pressed to name any Albanian author who has expressed his intimate impulses and desires in verse or prose. Migjenis verse and his prose abound with the figures of women, many of them unhappy prostitutes, for whom Migjeni betrays both pity and open sexual interest. It is the tearful eyes and the red lips which catch his attention; the rest of the body is rarely described. Passion and rapturous desire are ubiquitous in his verse, but equally present is the specter of physical intimacy portrayed in terms of disgust and sorrow. It is but one of the many bestial faces of misery described in the 105-line Poema e mjerimit ("The poem of the misery").

Legacy

Regarding his legacy, Elsie writes: "Though Migjeni did not publish a single book during his lifetime, his works, which circulated privately and in the press of the period, were an immediate success. Migjeni paved the way for modern literature in Albania." This literature was, however, soon to be nipped in the bud. The very year of the publication of Free Verse saw the victory of Stalinism in Albania and the proclamation of the People's Republic.

Many have speculated as to what contribution Migjeni might have made to Albanian letters had he managed to live longer. The question remains highly hypothetical, for this individualist voice of genuine social protest would no doubt have suffered the same fate as most Albanian writers of talent in the late 1940s, i.e. internment, imprisonment or execution. His early demise has at least preserved the writer for us undefiled.

The fact that Migjeni did perish so young makes it difficult to provide a critical assessment of his work. Though generally admired, Migjeni is not without critics. Some have been disappointed by his prose, nor is the range of his verse sufficient to allow us to acclaim him as a universal poet.

See also

Sources

- Elsie, Robert (2005). Albanian Literature: A Short History. I.B.Tauris. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4.

- Elsie, Robert (2012). A Biographical Dictionary of Albanian History. I.B.Tauris. pp. 308–309. ISBN 978-1-78076-431-3.

- Demo, Elsa (14 October 2011). "Migjeni në librin e shtëpisë". Mapo; Arkiva Lajmeve. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Pipa, Arshi (1978). Albanian literature: social perspectives. R. Trofenik. ISBN 978-3-87828-106-1.

- Polet, Jean-Claude (2002). Auteurs européens du premier XXe siècle: 1. De la drôle de paix à la drôle de guerre (1923-1939). De Boeck Supérieur. pp. 710–711. ISBN 978-2-8041-3580-5.

References

- ^ Pipa 1978, p. 134.

- Elsie 2005, p. 138.

- ^ Demo 2011.

- ^ Luarasi & Luarasi 2003, p. ?. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLuarasiLuarasi2003 (help)

- Polet 2002, p. 710.

- ^ "Tre "shokë": Migjeni, Pano e Dritëroi". mapo. 4 January 2015. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015.

- Vickers, Miranda; Pettifer, James (1997). Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity. London, England: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-290-8.

- Bahun, Sanja (2013). "The Balkans Uncovered: Toward Historie Croisée of Modernism". In Wollaeger, Mark; Eatough, Matt (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Global Modernisms. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19932-470-5.

- The Oxford Handbook of Global Modernisms. Oxford University Press. October 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-932470-5.

- Ersoy, Ahmet; Górny, Maciej; Kechriotis, Vangelis, eds. (2010). "Millosh Gjergj Nikolla: We, the Sons of the New Age; The Highlander Recital". Modernism – Representations of National Culture. Vol. 3. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-9-63732-664-6.

- ^ Angjelina Ceka Luarasi; Skender Luarasi (2003). Migjeni–Vepra. Cetis Tirana. pp. 7–8.

Është shkruar se nuk ishte shqiptar dhe se familja e tij kishte origjinë sllave, duke injoruar kështu faktet e paraqitura në biografinë e Skënder Luarasit, që dëshmojnë gjakun shqiptar të poetit nga familja dibrane e Nikollave dhe ajo Shkodrane e Kokoshëve.......gjyshi i tij vinte nga Nikollat e Dibrës......emrat me tingëllim sllav, duke përfshirë edhe atë të pagëzimit të Migjenit dhe të motrave të tij, nuk dëshmojnë më shumë se sa përkatësinë në komunitetin ortodoks të Shkodrës...... të ndikuar në atë kohë nga kisha fqinje malazeze.

- ^ Elsie 2012, p. 308.

- Elsie 2005.

- Great Britain. Admiralty (1920). A Handbook of Serbia, Montenegro, Albania and Adjacent Parts of Greece. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 403.

The following villages are in whole or part occupied by Orthodox Serbs — Brch, Borich, Basits, Vraka, Sterbets, Kadrum. Farming is the chief occupation.

- ^ Robert Elsie (2005). Albanian Literature: A Short History. I.B. Tauris. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4.

- "Review". Jeta e re (in Albanian). No. 10. 1958. p. 469.

Me botimin e prodhimit të parë letrar, „Sokrat i vuejtun apo derr i kënaqun?" n'Illyria të 27 majit 1934, fillon ritmi i shpejtë i aktivitetit letrar të Migjenit.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Scarecrow Press. pp. 301–302. ISBN 9780810873803.

- Pynsent, Robert B.; Kanikova, Sonia I. (1993). Reader's Encyclopedia of Eastern European Literature. HarperCollins. p. 262. ISBN 9780062700070.

His volume of poetry, Vargjet e lira (Free verse), went to press in 1936, but was immediately confiscated by the authorities; a second printing of it did appear in 1944.

- "Migjeni dhe epoka e tij". Studime Filologjike (in Albanian). 42 (3–4): 7. 1988.

Migjeni tregoi pasojat rrënimtare të papunësisë për familjet ... " Parathanja e parathanjeve" dhe « Blasfemi » u hoqën prej botimit të " Vargjeve të lira " të vitit 1944 dhe « Blasfemi » u hoqën prej botimit të " Vargjeve të lira " të vitit 1944

- https://robertwilton.com/

- Pipa 1978, p. 150.

External links

- "Authors: Migjeni". albanianliterature.com., explicit permission for use under GNU FDL.

- Migjeni (Millosh Gjergj Nikolla). Free Verse, Dukagjini, Peja 2001, A bilingual edition

- Luarasi, Skender (2002). Migjeni: Jeta (in Albanian). Tirana, Albania: Cetis.

Definitions from Wiktionary

Definitions from Wiktionary Media from Commons

Media from Commons Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote Texts from Wikisource

Texts from Wikisource Textbooks from Wikibooks

Textbooks from Wikibooks

- 1911 births

- 1938 deaths

- Albanian-language poets

- Albanian-language writers

- Albanian male poets

- 20th-century Albanian poets

- 20th-century Albanian writers

- Writers from Shkodër

- People from Scutari vilayet

- People from Shkodër County

- Former Albanian Orthodox Christians

- Albanian atheists

- 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- Tuberculosis deaths in Italy

- 20th-century Albanian male writers