| Revision as of 09:11, 17 November 2005 editSchutz (talk | contribs)Administrators8,575 edits →References: book ref -- in French, best I can do for now← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:03, 14 December 2024 edit undoSilverleaf81 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,208 edits Rescuing 0 sources and tagging 1 as dead.) #IABot (v2.0.9.5Tag: IABotManagementConsole [1.3] | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|State-owned intercity high-speed rail service of France}} | |||

| :''This article is about the French high-speed railway system. For the heart condition known as '''Transposition of the Great Vessels''', see ].'' | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2021}} | |||

| {{Infobox rail | |||

| | railroad_name = TGV | |||

| | logo_filename = TGV logo (2012).svg | |||

| | logo_size = | |||

| | system_map = | |||

| | map_caption = | |||

| | map_size = | |||

| | image = SNCF TGV Duplex 2N2 4718 (8464339495).jpg | |||

| | image_size = 300px | |||

| | image_caption = ] at ] in Paris, 2013 | |||

| | locale = {{bulleted list|], with services extending to ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and the ]|Technology exported for ] in ]|Derivative versions operated by ] and national companies in ], ] and the ]}} | |||

| | start_year = {{start date and age|1981}} | |||

| | end_year = present | |||

| | predecessor_line = | |||

| | successor_line = | |||

| | gauge = {{RailGauge|sg}} (]) | |||

| | length = | |||

| | hq_city = | |||

| | website = {{URL|https://www.groupe-sncf.com/en}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox rail | |||

| | railroad_name = LGV network | |||

| | map_size = 300px | |||

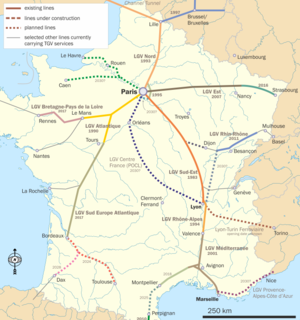

| | system_map = File:France TGV.png | |||

| | map_caption = High-speed lines in France | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''TGV''' ({{IPA|fr|teʒeve|lang|LL-Q150 (fra)-Poslovitch-TGV.wav}}; {{lang|fr|'''Train à Grande Vitesse'''}}, {{IPA|fr|tʁɛ̃ a ɡʁɑ̃d vitɛs|audio=LL-Q150 (fra)-WikiLucas00-train à grande vitesse.wav|}}, "high-speed train"; formerly {{lang|fr|TurboTrain à Grande Vitesse}}) is France's intercity ] service. With commercial operating speeds of up to {{convert|320|km/h|abbr=on}} on the newer lines,<ref>{{Cite news |title=Le TGV roulera bientôt à 360 km/h |language=fr |url=https://www.lefigaro.fr/societes-francaises/2007/12/17/04010-20071217ARTFIG00331-le-tgv-roulera-bientot-a-kmh-.php |first=Fabrice |last=Amedeo |newspaper=Le Figaro |date=17 December 2007 |access-date=6 July 2023}}</ref> the TGV was conceived at the same period as other technological projects such as the ] rocket and ] supersonic airliner; sponsored by the ], those funding programmes were known as {{lang|fr|champion national}} ("]") policies. In 2023 the TGV network in France carried 122 million passengers.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.europe1.fr/societe/sncf-tgv-ter-les-chiffres-dune-annee-record-4226071|title=SNCF : TGV, TER… les chiffres d’une année 2023 record|date=19 January 2024|publisher=]|access-date=|lang=fr}}</ref> | |||

| The state-owned ] started working on a high-speed rail network in 1966. It presented the project to President ] in 1974 who approved it. Originally designed as ]s to be ]s, TGV prototypes evolved into electric trains with the ]. In 1976 the SNCF ordered 87 high-speed trains from ]. Following the inaugural service between ] and ] in 1981 on the ], the network, centred on Paris, has expanded to connect major cities across France, including ], ], ], ], ] and ], as well as in neighbouring countries on a combination of high-speed and conventional lines. The success of the first high-speed service led to a rapid development of ''Lignes à Grande Vitesse'' (LGVs, "high-speed lines") to the south (], ], ]), west (], ], ]), north (], ]) and east (], ]). Since it was launched, the TGV has not recorded a single passenger fatality in an accident on normal, high-speed service. | |||

| ] in ] to western and south-western destinations.]] | |||

| A specially modified TGV high-speed train known as ], weighing only 265 tonnes, set the world record for the fastest wheeled train, reaching {{convert|574.8|km/h|abbr=on}} during a test run on 3 April 2007.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.foxnews.com/story/french-train-hits-357-mph-breaking-world-speed-record|title=French Train Hits 357 mph Breaking World Speed Record|date=4 April 2007|publisher=]|access-date=11 February 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110504144012/http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,263542,00.html|archive-date=4 May 2011|url-status=live}}</ref> In 2007, the world's fastest scheduled rail journey was a start-to-stop average speed of {{convert|279.4|km/h|mph|abbr=on}} between the ] and ] on the ],<ref name="worldspeedsurvey2007">{{Cite web |last=Taylor |first=Dr Colin|title=World Speed Survey 2007: New lines boost rail's high speed performance|url=https://www.railwaygazette.com/news/world-speed-survey-2007-new-lines-boost-rails-high-speed-performance/32295.article|date=4 September 2007|access-date=6 July 2023|website=Railway Gazette International|url-access=subscription|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110809030715/http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/world-speed-survey-new-lines-boost-rails-high-speed-performance.html|archive-date=9 August 2011}}</ref><ref name="worldspeedsurvey2007pdf" /> not surpassed until the 2013 reported average of {{convert|283.7|km/h|mph|abbr=on}} express service on the ] to ] segment of China's ].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/high-speed/single-view/view/world-speed-survey-2013-china-sprints-out-in-front.html|access-date=2 July 2013|title=World Speed Survey 2013: China sprints out in front|work=]|archive-date=26 June 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180626030658/http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/high-speed/single-view/view/world-speed-survey-2013-china-sprints-out-in-front.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> During the engineering phase, the ] (TVM) cab-signalling technology was developed, as drivers would not be able to see signals along the track-side when trains reach full speed. It allows for a train engaging in an emergency braking to request within seconds all following trains to reduce their speed; if a driver does not react within {{Cvt|1.5|km}}, the system overrides the controls and reduces the train's speed automatically. The TVM safety mechanism enables TGVs using the same line to depart every three minutes.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.infotransport.pl/admin/viewArticle.php?article_id=111&sesClientID=0|title=Sympozjum CS Transport w CNTK|language=pl|access-date=2009-05-18|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180626082807/http://www.infotransport.pl/admin/viewArticle.php?article_id=111&sesClientID=0|archive-date=26 June 2018|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="modular">{{cite web|title=TVM 400-a modular and flexible ATC system|last=Gruere|first=Y|year=1989| url=https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/51899}}</ref> | |||

| The '''TGV''' is ]'s '''''t'''rain à '''g'''rande '''v'''itesse''; literally "]". Developed by ] (now Alstom) and ], and operated primarily by SNCF, the French national ] company, it connects cities in France, especially ], and in some other neighbouring countries, such as ] and ]. TGVs under other brand names connect France with ] and the ] (]) and the ] (]). Trains derived from TGV design also operate in ] (]), ] (]) and the ] (]). | |||

| The TGV system itself extends to neighbouring countries, either directly (Italy, Spain, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany) or through TGV-derivative networks linking France to Switzerland (]), to Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands (former ]), as well as to the United Kingdom (]). Several future lines are under construction or planned, including extensions within France and to surrounding countries. The ], part of the ] that is currently under construction, is set to become the longest rail tunnel in the world. Cities such as ] and ] have become part of a "TGV ] belt" around Paris; the TGV also serves ] and ]. A visitor attraction in itself, it stops at ] and in southern tourist cities such as ] and ] as well. ], ], ], ] and ] are reachable by TGVs running on a mix of LGVs and modernised lines. In 2007, the SNCF generated profits of €1.1 billion (approximately US$1.75 billion, £875 million) driven largely by higher margins on the TGV network.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/jul/09/rail.sncf.montblancexpress|title=Europe's rail renaissance on track|first=David|last=Gow|work=guardian.co.uk|date=9 July 2008|access-date=9 February 2010 | location=London}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.streetsblog.org/2008/07/15/french-high-speed-trains-turn-175b-profit-leave-american-rail-in-the-dust/|title=French Trains Turn $1.75B Profit, Leave American Rail in the Dust|first=Ben|last=Fried|work=Streetsblog New York City|publisher=streetsblog.org|date=15 July 2008|access-date=9 February 2010|archive-date=22 March 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100322235150/http://www.streetsblog.org/2008/07/15/french-high-speed-trains-turn-175b-profit-leave-american-rail-in-the-dust/|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| TGV trains travel at up to 320 ] (200 ]). This is made possible by the use of tracks specifically designed for the purpose, without any sharp curves. Trains are built with features which make them suitable for high speed running, including high-powered ]s, articulated carriages and ], which removes the need for drivers to see lineside ]s at high speed. TGV trains are manufactured primarily by ], now often with the involvement of ]. | |||

| The TGV is a passenger train, except for a small series of TGVs used for postal freight between ] and ], ]. | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| The idea of the TGV was first proposed in the 1960s, after Japan had begun construction of the ] in 1959. At the time the Government of France favoured new technology, exploring the production of ] and the ] air-cushion vehicle. Simultaneously, the SNCF began researching high-speed trains on conventional tracks. In 1976, the administration agreed to fund the first line. By the mid-1990s, the trains were so popular that SNCF president ] declared that the TGV was "the train that saved French railways".<ref>{{cite journal |date=August 2010 |author=Fender, Keith |title=''TGV: High Speed Hero''|journal=] |publisher=] |volume=70 |issue=8}}</ref> | |||

| The idea of the TGV was first proposed in the ]. Originally, it was planned that the TGV, then standing for ''très grande vitesse'' (very high speed), would be powered by electricity from ]s developed for use in ]s. These were selected for their small size and good ], capable of delivering a high power output for a long period of time. The first prototype, TGV 001, was the only TGV built with this type of engine. The ] caused a sharp increase in the price of oil, after which it was deemed impractical to use oil to power the TGV. | |||

| ===Development=== | |||

| TGV 001 was not, however, a wasted prototype. The type of traction was only one part of a large experiment researching various technologies required for high-speed rail travel. High speed brakes were tested, capable of dissipating the large amount of energy of a train at high speed, and other aspects of research included aerodynamics and signalling. The train was articulated, meaning that two carriages share a bogie between them. On test, it reached 318 km/h (198 mph), which remains the world speed record for a non-electric train. The styling of TGV 001, both inside and out, was the work of the British-born designer Jack Cooper, and it was he who created the basis of all subsequent TGV design, including the distinctive shape of the nose of TGV power cars. | |||

| {{Main|Development of the TGV}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (left), the first equipment used on the service; and ] (right), the newest equipment used on the service, at ], 2019]] | |||

| It was originally planned that the TGV, then standing for ''{{lang|fr|très grande vitesse}}'' ("very high speed") or ''{{lang|fr|turbine grande vitesse}}'' ("high-speed turbine"), would be propelled by ], selected for their small size, good ] and ability to deliver high power over an extended period. The first prototype, ], was the only gas-turbine TGV: following the increase in the price of ] during the ], gas turbines were deemed uneconomic and the project turned to electricity from ], generated by ]s. | |||

| TGV 001 was not a wasted prototype:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.trainweb.org/tgvpages/history.html|title=Early TGV history|work=TGVWeb|access-date=18 April 2008}}</ref> its gas turbine was only one of its many new technologies for high-speed rail travel. It also tested high-speed brakes, needed to dissipate the large amount of ] of a train at high speed, high-speed aerodynamics, and signalling. It was articulated, comprising two adjacent carriages sharing a ], allowing free yet controlled motion with respect to one another. It reached {{convert|318|km/h|abbr=on}}, which remains the world speed record for a non-electric train. Its interior and exterior were styled by French designer Jacques Cooper, whose work formed the basis of early TGV designs, including the distinctive nose shape of the first power cars. | |||

| ] | |||

| Changing the specification of the TGV to electric traction required a large overhaul in the design of the train. The first fully electric prototype, nicknamed Zébulon, was completed in ], testing features such as innovative body-mounting of motors, ]s, suspension and braking. Body mounting of motors allowed over 3 tonnes (3.3 tons) to be dropped from the weight of the power cars. The prototype travelled almost 1,000,000 km (621,000 miles) during testing. | |||

| Changing the TGV to electric traction required a significant design overhaul. The first electric prototype, nicknamed Zébulon, was completed in 1974, testing features such as innovative body mounting of motors, ]s, ] and ]. Body mounting of motors allowed over 3 tonnes to be eliminated from the power cars and greatly reduced the ]. The prototype travelled almost {{convert|1000000|km|4=0|abbr=on}} during testing. | |||

| In 1976 the ] gave full funding to the TGV project, and construction of the LGV Sud-Est, the first high-speed line, began shortly afterwards. The line was given the designation LN1, ''Ligne Nouvelle 1'' (New Line 1). | |||

| In 1976, the French administration funded the TGV project, and construction of the ], the first high-speed line ({{langx|fr|link=no|ligne à grande vitesse}}), began shortly afterwards. The line was given the designation LN1, ''{{lang|fr|Ligne Nouvelle 1}}'' ("New Line 1"). After two pre-production trainsets (nicknamed ''Patrick'' and ''Sophie'') had been tested and substantially modified, the first production version was delivered on 25 April 1980. | |||

| After two pre-production trainsets had been rigorously tested and substantially modified, the first production version was delivered on ] ] and the service opened to the public between ] and ] on ] ]. The initial target customers were businesspeople travelling between those two cities; the TGV was for them a faster solution than normal trains, cars, or airplanes. The client base soon expanded across the population, which welcomed a practical and fast way to travel between cities. | |||

| ===Service=== | |||

| Since then, further LGVs have opened in France: the LGV Atlantique (LN2) to ]/] (construction began 1985, operation began 1989); the LGV Nord Europe (LN3) to ] and the Belgian border (construction began 1989, operation began 1993); the LGV Rhône-Alpes (LN4), extending the LGV Sud-Est to ] (construction began 1990, operation began 1992); and the LGV Méditerrannée (LN5) to ] (construction began 1996, operations began 2001). A line from ] to ], the LGV Est, is under construction. High speed lines have also been built in ], ] and ]. | |||

| {{Main|List of TGV services}} | |||

| ], seen on the ] in ], ]. This service between Strasbourg and Montpellier runs on both high-speed and classic lines.]] | |||

| ]. The service towards the north runs on the classic line until Marseille, when it joins the ]. The proposed ] allows for extending the high-speed service to Nice.]] | |||

| ] in the ] is popular in the winter season.]] | |||

| The TGV opened to the public between ] and ] on 27 September 1981. Contrary to its earlier fast services, SNCF intended TGV service for all types of passengers, with the same initial ticket price as trains on the parallel conventional line. To counteract the popular misconception that the TGV would be a premium service for business travellers, SNCF started a major publicity campaign focusing on the speed, frequency, reservation policy, normal price, and broad accessibility of the service.<ref name="onthefasttrack1">{{cite book |title=On The Fast Track: French Railway Modernisation and the Origins of the TGV, 1944–1983 |first=Jacob |last=Meunier |pages=209–210|isbn= 978-0275973773|location=New York|publisher=Praeger|year=2001}}</ref> This commitment to a democratised TGV service was enhanced in the ] era with the promotional slogan "Progress means nothing unless it is shared by all".<ref name="onthefasttrack2">{{cite book |title=On The Fast Track: French Railway Modernisation and the Origins of the TGV, 1944–1983 |first=Jacob |last=Meunier |pages=7|isbn= 978-0275973773|location=New York|publisher=Praeger|year=2001}}</ref> The TGV was considerably faster (in terms of door to door travel time) than normal trains, ], or ]. The trains became widely popular, the public welcoming fast and practical travel. | |||

| The ] service began operation in 1994, connecting ] to ] via the ] and the LGV Nord-Europe with a version of the TGV designed for use in the tunnel and the United Kingdom. The first phase of the British ] line was completed in 2003, the second phase in November 2007. The fastest trains take 2 hours 15 minutes London–Paris and 1 hour 51 minutes London–Brussels. The first twice-daily London-Amsterdam service ran 3 April 2018, and took 3 hours 47 minutes.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.standard.co.uk/news/transport/jubilant-passengers-hop-on-board-first-ever-direct-train-from-london-to-amsterdam-a3805256.html|title=Eurostar's first ever train from London to Amsterdam arrives in style|website=standard.co.uk|date=5 April 2018}}</ref> | |||

| The ] service (operation began in 1994), which connects Europe to London via the ], used high speed ligns in France from the outset but the lines in the ] are being improved to the SNCF standard with the ] project. The project is due for completion in 2007, by which time London-Brussels will take only 2 hours and London-Paris only 2h15. The trains are not strictly TGVs but as a collaboration they bear many hallmarks of one. | |||

| ===Milestones=== | |||

| The TGV was hardly the world's first commercial high-speed service; the Japanese '']'' connected ] and ] from ] ], nearly 17 years before the first TGVs, but it ''is'' one of the fastest in the world. The TGV, but it is also the fastest conventional train in the world under test conditions: in ] it reached speeds of 515.3 km/h (320.2 mph) with a shortened train (two power cars and three passenger cars). | |||

| ] | |||

| The TGV (1981) was the world's second commercial and the fastest ] high-speed train service,<ref>{{cite web |title=General definitions of highspeed |url=http://www.uic.asso.fr/gv/article.php3?id_article=14 |publisher=] |date=28 November 2006 |access-date=2007-01-03 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20061210125239/http://www.uic.asso.fr/gv/article.php3?id_article=14 <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archive-date = 10 December 2006}}</ref> after Japan's ], which ] Tokyo and ] from 1 October 1964. It was a commercial success. | |||

| A TGV test train holds the ] for conventional trains. On 3 April 2007 a ] train reached {{convert|574.8|km/h|abbr=on}} ] on the ] between Paris and Strasbourg. The line voltage was boosted to 31 kV, and extra ballast was tamped onto the permanent way. The train beat the 1990 ] of {{convert|515.3|km/h|abbr=on}}, set by a similarly TGV, along with unofficial records set during weeks preceding the official record run. The test was part of an extensive research programme by Alstom.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.transport.alstom.com/home/news/Hot_news/27681.EN.php?languageId=EN&dir=/home/news/Hot_news/ |title=Alstom commits itself to the French very high speed rail programme |publisher=Alstom |date=18 December 2006 |access-date=2007-02-04 }}{{dead link|date=May 2017|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.monstersandcritics.com/business/news/article_1263596.php/French_high-speed_TGV_breaks_world_conventional_rail-speed_record |title=French high-speed TGV breaks world conventional rail-speed record |publisher=Deutsche Presse-Agentur (reprinted by Monsters and Critics) |date=14 February 2007 |access-date=2007-02-14 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070218084148/http://news.monstersandcritics.com/business/news/article_1263596.php/French_high-speed_TGV_breaks_world_conventional_rail-speed_record |archive-date=18 February 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| On ] ] the TGV carried its one billionth passenger since operations began in 1981. The two billion mark is expected to be reached in 2010. | |||

| In 2007, the TGV was the ]: one journey's average start-to-stop speed from Champagne-Ardenne Station to Lorraine Station is {{convert|279.3|km/h|mph|abbr=on}}.<ref name="worldspeedsurvey2007"/><ref name="worldspeedsurvey2007pdf"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090731062056/http://www.railwaygazette.com/fileadmin/user_upload/railwaygazette.com/PDF/RailwayGazetteWorldSpeedSurvey2007.pdf |date=31 July 2009 }} ] (September 2007)</ref><!-- Note: Sources conflict between 279.3 and 279.4 km/h --> | |||

| ==Tracks== | |||

| This record was surpassed on 26 December 2009 by the new ]<ref>{{Cite web |title=Wuhan–Guangzhou line opens at 380 km/h |url=https://www.railwaygazette.com/news/wuhan-guangzhou-line-opens-at-380-km/h/34651.article|date=4 January 2010 |access-date=6 July 2023 |website=Railway Gazette International}}</ref> in ] where the fastest scheduled train covered {{convert|922|km|mi|abbr=on}} at an average speed of {{convert|312.54|km/h|mph|abbr=on}}.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/world-speed-survey-2015-china-remains-the-pacesetter.html|title=World Speed Survey 2015: China remains the pacesetter|last=Ltd|first=DVV Media International|work=Railway Gazette International|access-date=2018-12-03|language=en|archive-date=9 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201109052010/https://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/world-speed-survey-2015-china-remains-the-pacesetter.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| The TGV runs on dedicated tracks known as LGV (''ligne à grande vitesse'', "high-speed line"), allowing speeds of up to 320 ] (200 ]) in normal operation on the newest lines. Originally defined as a line permitting speeds greater than 200 km/h (125 mph), this has now been increased to 250 km/h (155 mph). TGV trains can also run on conventional tracks (''lignes classiques''), albeit at the normal maximum line speed for those lines, up to a maximum of 220 km/h (137 mph). This is an advantage that the TGV has over, for example, ]s, as it means that TGVs can serve far more destinations and can use city-centre stations (for example in ], ], and ]). They now serve around 200 destinations in France and abroad. | |||

| A ] broke the record for the longest non-stop high-speed international journey on 17 May 2006 carrying the cast and filmmakers of '']'' from London to ] for the ]. The {{convert|1421|km|mi|adj=on}} journey took 7 hours 25 minutes on an average speed of {{convert|191.6|km/h|mph|abbr=on}}.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.eurostar.com/UK/uk/leisure/about_eurostar/press_release/press_archive_2006/17_05_2006_world_record.jsp| title=Eurostar sets new Guinness World Record with cast and filmmakers of Columbia Pictures' The Da Vinci Code| publisher=]| date=17 May 2006| access-date=2007-02-15| url-status=dead| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070514152951/http://www.eurostar.com/UK/uk/leisure/about_eurostar/press_release/press_archive_2006/17_05_2006_world_record.jsp| archive-date=14 May 2007}}</ref> | |||

| The LGVs are similar to normal railway lines, but there are key differences. The radii of curves are larger so that the trains can travel at higher speeds around them without increasing the ] felt by passengers. This radius is usually greater than 4 ] (2.5 ]s), but new lines have minimum radii of 7 km (4 mi) to allow for future increases in speed. | |||

| The fastest single long-distance run on the TGV was done by a ] train from Calais-Frethun to Marseille ({{convert|1067.2|km|||abbr=on}}i) in 3 hours 29 minutes at a speed of {{convert|306|km/h|mph|0|abbr=on}} for the inauguration of the ] on 26 May 2001.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/1354047.stm| title=French train breaks speed record| work=]| date=27 May 2001| access-date=2007-08-26}}</ref> | |||

| If used only for high-speed traffic, lines can incorporate steeper gradients. This facilitates the planning of LGV routes and reduces the cost of construction. The momentum of TGV trains at high speed means that they can climb steep slopes without greatly increasing their energy consumption, and they can coast on downward slopes. On the Paris-Sud-Est LGV there are gradients of 35‰ and on the German high-speed line between ] and ] they reach 40‰. | |||

| ===Passenger usage=== | |||

| Track alignment is more precise. ] is built into a stronger profile. There are more sleepers per kilometre and all are made of concrete (either mono- or biblocs, the latter being when the sleeper consists of two separate blocks of concrete joined by a steel bar). Heavy rail (UIC 60) is used, and the rails themselves are more upright (1/40° as opposed to 1/20° on normal lines). Continuous welded rails in place of shorter, jointed rails means that the ride is comfortable at high speeds, without the usual 'clickety-clack' vibrations induced by rail joints. | |||

| On 28 November 2003, the TGV network carried its one billionth passenger, a distant second only to the Shinkansen's five billionth passenger in 2000. | |||

| Excluding international traffic, the TGV system carried 98 million passengers during 2008, an increase of 8 million (9.1%) on the previous year.<ref name="SNCFfigures2008">{{cite web|url=http://www.sncf.com/resources/fr_FR/press/kits/PR0002_20090212.pdf |title=Bilan de l'année 2008 : Perspectives 2009 |date=12 February 2009 |language=fr |publisher=] |access-date=2009-03-07 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090319045214/http://www.sncf.com/resources/fr_FR/press/kits/PR0002_20090212.pdf |archive-date=19 March 2009 }}</ref> | |||

| Track must be at least ], 1,435 ] (4 ] 8½]), or ] to allow speeds greater than 200 km/h (125 mph). ]ese and ]ese LGV networks are therefore separated from the original ] networks. On the ], however, which uses wide gauge track on normal lines, standard gauge is used on LGVs so that they remain compatible with the rest of Europe. If tunnels are required, their diameter must be greater than that required by the gauge of the trains travelling through them, especially at the entrances. This is to limit the effects of air pressure changes. | |||

| {{Div flex row|align-items=center|div o=yes}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- style="background: #cccccc; | |||

| |+TGV passengers in millions from 1981 to 2010<ref>Pepy, G.: 25 Years of the TGV. Modern Railways 10/2006, pp. 67–74</ref><ref group="t">from 1994 including Eurostar</ref><ref group="t">from 1997 including Thalys</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 1980 !! 1981 !! 1982 !! 1983 !! 1984 !! 1985 !! 1986 !! 1987 !! 1988 !! 1989 | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{center|–}} || 1.26 || 6.08 || 9.20 || 13.77 || 15.38 || 15.57 || 16.97 || 18.10 || 19.16 | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 1990 !! 1991 !! 1992 !! 1993 !! 1994 !! 1995 !! 1996 !! 1997 !! 1998 !! 1999 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 29.93 || 37.00 || 39.30 || 40.12 || 43.91 || 46.59 || 55.73 || 62.60 || 71.00 || 74.00 | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 2000 !! 2001 !! 2002 !! 2003 !! 2004 !! 2005 !! 2006 !! 2007 !! 2008 !! 2009 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 79.70 || 83.50 || 87.90 || 86.70 || 90.80 || 94.00 || 97.00 || 106.00 || 114.00 || 122.00 | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 2010 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 114.45 | |||

| |} | |||

| {{Reflist|group=t}} | |||

| {{Div CO}} | |||

| {{Graph:Chart | type=rect |width = 450 |yGrid= | |||

| | y =1.26, 6.08, 9.20, 13.77, 15.38, 15.57, 16.97, 18.10, 19.16, 29.93, 37.00, 39.30, 40.12, 43.91, 46.59, 55.73, 62.60, 71.00, 74.00, 79.70, 83.50, 87.90, 86.70, 90.80, 94.00, 97.00, 106.00, 114.00, 122.00, 114.45 | |||

| | yAxisTitle = Passengers (millions) | |||

| | xAxisTitle = Year | xAxisAngle=-70 | |||

| | x = 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 | |||

| }}{{div flex row end|div c=y}} | |||

| ==Rolling stock== | |||

| LGVs have a minimum speed limit. In other words, trains which are not capable of high speed may not use LGVs, which are limited for the most part to passenger trains. Capacity is sharply reduced when trains of differing speeds are mixed. Passing freight and passenger trains also pose a risk due to the destabilisation of cargo caused by the air currents around TGVs. Nor can slower traffic use LGVs after dark, when TGVs are not running, because the line infrastructure is maintained at night. | |||

| ] station in Paris, 1985]] | |||

| All TGV trains have two ]s, one on each end. Between those power cars are a set of semi-permanently coupled ] un-powered ]. Cars are connected with ]s, a single ] shared between the ends of two coaches. The only exception are the end cars, which have a standalone bogie on the side closest to the power car, which is often motorized. Power cars also have two bogies. | |||

| Trains can be lengthened by coupling two TGVs, using couplers hidden in the noses of the power cars. | |||

| The steep gradients on TGV lines limit the weight of slow freight trains. Slower trains also mean that the maximum track cant (banking on curves) is limited, so for the same maximum speed LGVs would need to be built with curves of even higher radius. A mixed-traffic LGV would therefore be more expensive and difficult to plan to take account of the relief of land and obstacles. The problems have been overcome on certain stretches of less-used track, however, namely on the ] branch of the LGV Atlantique, and on the planned ]/] branch of the LGV Mediterranée. | |||

| The articulated design is advantageous during a derailment, as the passenger carriages are more likely to stay upright and in line with the track. Normal trains could split at ]s and jackknife, as seen in the ]. A disadvantage is that it is difficult to split sets of carriages. While power cars can be removed from trains by standard uncoupling procedures, specialized equipment is needed to split carriages, by lifting up cars off a bogie. Once uncoupled, one of the carriage ends is left without support, so a specialized frame is required. | |||

| LGVs are all ]. Apart from the constraints involved in refuelling and carrying fuel on board trains, diesel traction cannot produce the continuous thrust required for high-speed running. Apart from the Italian high-speed line between ] and ], which is currently electrified at 3 ] ] (the same as the rest of the Italian network, although conversion to the European standard for LGVs is planned), LGVs are electrified at high voltage ]: 15 kV, 16 2/3 ] in Germany and Austria, and 25 kV, 50/60 Hz everywhere else, including future Italian high-speed lines. | |||

| SNCF prefers to use power cars instead of ] because it allows for less electrical equipment.<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr17/pdf/f40_technology.pdf | title=What Drives Electric Multiple Units? | website=www.ejrcf.or.jp | first=Hiroshi | last=Hata}}</ref> | |||

| Catenary wires are kept at a higher tension than normal lines. This is because the ] causes ]s in the wires, and the ] must travel faster than the train to avoid producing ]s which would cause the wires to break. This was a problem when attempting the rail speed record in ] when the tension had to be increased further still to accommodate train speeds of over 500 km/h (310 mph). This also means that while trains are on LGVs, only the rear pantograph is raised, to avoid the rear pantograph amplifying oscillations created by the front pantograph. The front power car is supplied by a cable running along the roof. Eurostar trains are, however, long enough that oscillations are ] sufficiently between the front and rear power cars and both pantographs are raised. On ''lignes classiques'' this is not a problem due to the slower line speed, and both DC pantographs are raised. | |||

| There are six types of TGV equipment in use, all built by ]: | |||

| LGVs are fenced along their entire length to avoid animals on the line. ]s are not permitted and bridges over the tracks are equipped with sensors to detect if anything has fallen onto the line. | |||

| * ] (10 carriages) | |||

| * ] (an upgrade of the Atlantique, 8 carriages) | |||

| * ] (two floors for greater passenger capacity) | |||

| * ] (originally for routes to Germany, now used to Switzerland) | |||

| * ] (also known as the Avelia Euroduplex, an upgrade of the TGV Duplex) | |||

| * ] (also known as the Avelia Horizon, expected to enter service in 2025) | |||

| Retired sets: | |||

| All junctions on LGVs are ], that is to say tracks crossing each other always use ] or ]s in order to avoid the need to cross over in front of trains travelling in the opposite direction. Crossing over in front of other trains requires a large gap in the timetable in the opposite direction to allow the movement, greatly reducing capacity. | |||

| * ] (retired in December 2019) | |||

| **] (retired in June 2015) | |||

| Several TGV types have broken records, including the ] and ]. V150 was a specially modified five-car double-deck trainset that ] under controlled conditions on a test run. It narrowly missed beating the world train speed record of {{convert|581|km/h|abbr=on}}.<ref>{{Cite news|title=French Train Sets New World Speed Record |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/migrationtemp/1547513/French-train-sets-new-world-speed-record.html |location=London |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080507193619/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/migrationtemp/1547513/French-train-sets-new-world-speed-record.html |archive-date=7 May 2008 }}</ref> The record-breaking speed is impractical for commercial trains due to motor overcharging, empty train weight, rail and engine wear issues, elimination of all but three coaches, excessive vibration, noise and lack of ]. TGVs travel at up to {{Convert|320|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}} in commercial use. | |||

| ==LGV Signalling== | |||

| The TVM (or ''Transmission Voie-Machine'') system is used for signalling on LGVs. Information is transmitted to trains via electrical pulses through the rails, giving indications (speed, target speed, stop/go) directly to the train driver through dashboard-mounted visual indicators rather than lineside ] - trains are travelling too fast to be sure of the driver seeing lineside signal aspects. Trains are under the driver's control, though there are safeguards against driver errors that can safely bring the train to a stop. | |||

| All TGVs are at least ''bi-current'', which means that they can operate at {{25 kV 50 Hz}} (used on LGVs) and {{1,500 V DC}} (used on traditional lines). Trains travelling internationally must accommodate other voltages ({{15 kV AC}} or {{3,000 V DC}}), requiring ''tri-current'' and ''quad-current'' TGVs. | |||

| The line is divided into signal blocks, the boundaries of which are marked by blue boards with a yellow triangle.<!-- can we get an image of one of these signs? --> The indicators on the dashboard show the maximum permitted speed for the block where the train is and also a target speed based on the profile of the line. The maximum permitted speed is based on factors such as the location of trains ahead (with steadily decreasing maximum permitted speeds in blocks closer to the rear of the next train), ]s, speed restrictions, the maximum speed of the train and an approaching end of LGV. As trains cannot usually stop in the distance of one signal block (which varies between a few hundred metres and a few kilometres), drivers are alerted when there is a requirement to slow down gradually several blocks in advance. | |||

| Each TGV power car has two pantographs: one for AC use and one for DC. When passing between areas with different electric systems (identified by marker boards), trains enter a phase break zone. Just before this section, train operators must power down the motors (allowing the train to ]), lower the pantograph, adjust a switch to select the appropriate system, and raise the pantograph. Once the train exits the phase break zone and detects the correct electric supply, a dashboard indicator illuminates, and the operator can once again engage the motors. | |||

| Two types of signalling are in use on the LGV: TVM-300, the older system and TVM-430. TVM-430 was first installed on the LGV Nord to the ] and Belgium, and supplies trains with more information than the older system, allowing the on-board system to generate a continuous speed control curve in the event of an emergency brake activation, and force and guide the driver to control the speed without releasing the brake. However, drivers can always anticipate braking as they know the maximum authorized speed in the block in front of them as well as in the block which they are in from the signalling system. | |||

| The signalling system is permissive; the driver of a train is permitted to proceed into an occupied block section without first obtaining authorization. Speed in this situation is limited to 30 km/h (19 mph; proceed with caution) and if the speed exceeds 35 km/h (22 mph), the emergency brake is applied and the train stops. If the board marking the entrance to the block section is accompanied by a sign marked NF, the block section is not permissive, and the driver must obtain authorization from the OCC<!-- What is OCC? --> prior to entering. Once a route is set, or the OCC has provided authorization, a white lamp above the board is lit to inform the driver. The driver then acknowledges the authorization using a button on the control panel. This disables the emergency brake application which would otherwise occur when passing over the ground loop adjacent to the non-permissive board. | |||

| When trains enter or leave LGVs from ''lignes classiques'', they pass over a ground loop which automatically switches the driver's dashboard indicators to the appropriate signalling system. For example, a train leaving the LGV onto a French ''ligne classique'' would have its TVM signalling system deactivated and the KVM system used on the ''lignes classiques'' would be enabled. | |||

| ] | |||

| ==TGV Stations== | |||

| One of the main advantages of TGV compared to other technologies such as ] is that it can run on existing tracks and use existing stations, or stations shared with other types of trains. This means that it is easy to serve routes from city centre to city centre (say, Paris-] to Lyon-]) without having to build new tracks or stations inside cities. Building new stations in city centres can be expensive, usually involving either long tunnels or bridges so that the new route can pass through densely populated areas. | |||

| However, there has been a tendency to build new stations serving smaller locations in suburban areas or in the open countryside some miles away from the town, so as to be able to make a stop without incurring too great a time penalty. In some cases, such as the station serving ] and ], the station was built in the middle between the two towns. Another example is the ] station between ] and ]. This latter one was rather controversial, criticized in the press and by local government as too far from either town to be useful, and situated near a trunk road rather than a connecting railway line: it was often nicknamed ''la gare des betteraves,'' or 'beetroot station'. | |||

| A number of major new railway stations were built, some of which have been major architectural achievements in their own right. ] TGV station, opened in ], has won particular praise as one of the most remarkable stations on the network, with a spectacular 340 m (1,115 ft) long glazed roof that has led to the building being compared to a ]. | |||

| ==Rolling stock== | |||

| ], in ].]] | |||

| TGV ] differs from other types in that trains consist of semi-permanently coupled ]s. ]s are located between the carriages, supporting the carriages on either side, so that each carriage shares its bogies with the two adjacent to it. ]s at either end of the trains have their own bogies. | |||

| This design means that in the case of a derailment, the locomotive derails first and can move separately from the passenger carriages, which are more likely to stay upright and in line with the track. This is unlike normal trains which tend to split at the ]s and jacknife. | |||

| The disadvantage of the design is that it is difficult to split sets of carriages. The locomotives can be removed normally by uncoupling them, but to split the carriages requires the use of lifting equipment in maintenance depots which can lift an entire set at once. Once uncoupled, one of the carriage ends is left without a bogie at the split, so a bogie frame is required to hold it up. | |||

| SNCF operates a fleet of about 400 TGV trainsets. Six types of TGV or TGV derivative currently operate on the French network: TGV Sud-Est (passenger and ''La Poste'' varieties), TGV Atlantique, TGV Réseau/Thalys PBA, Eurostar, TGV Duplex and Thalys PBKA. A seventh type, TGV POS (Paris-Ostfrankreich-Suddeutschland, or Paris-Eastern France-Southern Germany), is currently being tested. | |||

| All TGVs are at least bi-current, that is to say they can operate under 25 kV, 50 Hz AC on newer lines, including LGVs and under 1.5 kV DC on older French ''lignes classiques'', especially around Paris. Trains crossing the border into ], ], ], the ] and the ] must accommodate foreign voltages. This has led to the construction of tri-current or even quadri-current TGVs. All TGVs are equipped with two pairs of pantographs, two for AC use and two for DC use. When passing between areas of different supply voltage, marker boards are installed to remind the driver to lower the pantograph(s) and turn off power to the ]s, adjust a switch on the dashboard to the appropriate system, and raise the pantograph(s) again, pantographs and pantograph height control being selected automatically depending on the voltage system selected. Once the train detects the correct supply to its transformers, an indicator lights and the driver can switch on power to the traction motors. The train coasts across the border between voltage sections while traction motor power is off. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| ! Equipment type | ! rowspan="2" | Equipment type | ||

| ! Top speed | ! colspan="2" | Top speed | ||

| ! Seating<br>capacity | ! rowspan="2" | Seating <br />capacity | ||

| ! Overall length | ! colspan="2" | Overall length | ||

| ! Width | ! colspan="2" | Width | ||

| ! Weight | ! rowspan="2" | Weight, <br />empty (t) | ||

| ! rowspan="2" | Weight, <br />full (t) | |||

| ! Power output<br>(under 25 kV) | |||

| ! rowspan="2" | Power, <br />at 25 kV (kW) | |||

| ! rowspan="2" | ] ratio, <br />empty (kW/t) | |||

| ! rowspan="2" | First <br />built | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! km/h !! mph | |||

| | TGV Sud-Est | |||

| ! m !! ft | |||

| | 270 ] (168 ]) as built<br>300 km/h (186 mph) rebuilt | |||

| ! m !! ft | |||

| | 345 | |||

| | 200 ] (656 ]) | |||

| | 2.81 m (9.2 ft) | |||

| | 385 ]s (424 ]s) | |||

| | 6,450 kW | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | TGV Atlantique | | ] | ||

| | 300 |

| {{convert|300|km/h|disp=table}} | ||

| | align="right" | 485, 459 (rebuilt) | |||

| | 485 | |||

| | {{convert|238|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | 237.5 m (780 ft) | |||

| | {{convert|2.90|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | 2.9 m (9.5 ft) | |||

| | align="right" | 444 | |||

| | 444 tonnes (489 tons) | |||

| | align="right" | 484 | |||

| | 8,800 kW | |||

| | align="right" | 8,800 | |||

| | align="right" | 19.82 | |||

| | align="right" | 1988 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | TGV Réseau | | ] | ||

| | {{convert|320|km/h|disp=table}} | |||

| | 300 km/h (186 mph) | |||

| | align="right" | 377, 361 (rebuilt) | |||

| | 377 | |||

| | {{convert|200|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | 200 m (656 ft) | |||

| | {{convert|2.90|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | 2.81 m (9.2 ft) | |||

| | align="right" | 383 | |||

| | 383 tonnes (422 tons) | |||

| | align="right" | 415 | |||

| | 8,800 kW | |||

| | align="right" | 8,800 | |||

| | align="right" | 22.98 | |||

| | align="right" | 1992 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] | |||

| | Eurostar Three Capitals | |||

| | {{convert|320|km/h|disp=table}} | |||

| | 300 km/h (186 mph) | |||

| | align="right" | 508 | |||

| | 794 | |||

| | {{convert|200|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | 394 m (1,293 ft) | |||

| | {{convert|2.90|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | 2.81 m (9.2 ft) | |||

| | align="right" | 380 | |||

| | 752 tonnes (829 tons) | |||

| | align="right" | 424 | |||

| | 12,240 kW | |||

| | align="right" | 8,800 | |||

| | align="right" | 23.16 | |||

| | align="right" | 1994 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] | |||

| | Eurostar North of London | |||

| | {{convert|320|km/h|disp=table}} | |||

| | 300 km/h (186 mph) | |||

| | align="right" | 361 | |||

| | 596 | |||

| | {{convert|200|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | ~315 m (1,033 ft) | |||

| | {{convert|2.90|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | 2.81 m (9.2 ft) | |||

| | align="right" | 383 | |||

| | | |||

| | align="right" | 415 | |||

| | 12,240 kW | |||

| | align="right" | 9,280 | |||

| | align="right" | 24.23 | |||

| | align="right" | 2005 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] | |||

| | TGV Duplex | |||

| | 320 |

| {{convert|320|km/h|disp=table}} | ||

| | align="right" | 509(SNCF), 533(ONCF) | |||

| | 512 | |||

| | {{convert|200|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | 200 m (656 ft) | |||

| | {{convert|2.90|m|ft|disp=table}} | |||

| | | |||

| | align="right" | 380 | |||

| | 386 tonnes (425 tons) | |||

| | align="right" | 424 | |||

| | 8,800 kW | |||

| | align="right" | 9,400 | |||

| |- | |||

| | align="right" | 24.74 | |||

| | Thalys PBKA | |||

| | align="right" | 2011 | |||

| | 300 km/h (186 mph) | |||

| | 377 | |||

| | 200 m (656 ft) | |||

| | | |||

| | 385 tonnes (424 tons) | |||

| | 8,800 kW | |||

| |- | |||

| | TGV POS | |||

| | 320 km/h (199 mph) | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | 423 tonnes (466 tons) | |||

| | 9,600 kW | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ===TGV Sud-Est=== | ===TGV Sud-Est=== | ||

| {{Main|SNCF TGV Sud-Est|SNCF TGV La Poste}} | |||

| The ] fleet was built between ] and ] and operated the first TGV service from Paris to Lyon in 1981. Currently there are 107 passenger sets operating, of which nine are tri-current (including 15 kV, 16 2/3 Hz AC for use in Switzerland) and the rest bi-current. There are also seven bi-current half-sets without seats which carry mail for ] between Paris and Lyon. These are painted in a distinct yellow livery. | |||

| ] set in the original orange livery.]] | |||

| The Sud-Est fleet was built between 1978 and 1988 and operated the first TGV service, from Paris to Lyon in 1981. There were 107 passenger sets, of which nine are tri-current (including {{15 kV AC}} for use in Switzerland) and the rest bi-current. There were seven bi-current half-sets without seats that carried mail for ] between Paris, Lyon and ], in a distinctive yellow livery until they were phased out in 2015. | |||

| Each set were made up of two power cars and eight carriages (capacity 345 seats), including a powered bogie in the carriages adjacent to the power cars. They are {{convert|200|m|ftin|abbr=on}} long and {{convert|2.81|m|ftin|abbr=on}} wide. They weighed {{Convert|385|t|lb}} with a power output of 6,450 kW under 25 kV. | |||

| The sets were originally built to run at {{convert|270|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}} but most were upgraded to {{convert|300|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}} during mid-life refurbishment in preparation for the opening of the LGV Méditerranée. The few sets that kept a maximum speed of {{convert|270|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}} operated on routes that include a comparatively short distance on LGV, such as to Switzerland via Dijon; SNCF did not consider it financially worthwhile to upgrade their speed for a marginal reduction in journey time. | |||

| Each set is made up of two power cars and eight carriages (capacity 345 seats), including a powered bogie in each of the carriages adjacent to the power cars. They are 200 m (656 ft) long and 2.81 m (9.2 ft) wide. They weigh 385 ]s (424 ]s) with a power output of 6,450 kW under 25 kV. | |||

| In December 2019, the trains were phased out from service. In late 2019 and early 2020, TGV 01 (Nicknamed Patrick), the very first TGV train, did a farewell service that included all three liveries that were worn during their service.<ref>{{Cite web|title= Farewell tour for Patrick, the first TGV train|url=https://engnews24h.com/sncf-farewell-tour-for-patrick-the-first-tgv-train/|date=2020-02-07|website=Eng News 24h|language=en-US|access-date=2020-05-18|archive-date=15 February 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200215154227/http://engnews24h.com/sncf-farewell-tour-for-patrick-the-first-tgv-train/|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Originally the sets were built to run at 270 km/h (168 mph) but most were upgraded to 300 km/h (186 mph) during their mid-life refurbishment in preparation for the opening of the LGV Méditerranée. The few sets which still have a maximum speed of 270 km/h operate on routes which have a comparatively short distance on the ''lignes à grande vitesse'', such as those to Switzerland via Dijon. SNCF did not consider it financially worthwhile to upgrade their speed for a marginal reduction in journey time. | |||

| ===TGV Atlantique=== | ===TGV Atlantique=== | ||

| {{Main|SNCF TGV Atlantique}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] fleet was built between ] and ]. 105 bi-current sets were built for the opening of the LGV Atlantique and entry into service began in ]. They are 237.5 m (780 ft) long and 2.9 m (9.5 ft) wide. They weigh 444 tonnes (489 tons), and are made up of two power cars and ten carriages with a capacity of 485 seats. They were built from the outset with a maximum speed of 300 km/h (186 mph) with 8,800 kW total power under 25 kV. | |||

| The 105 train Atlantique fleet was built between 1988 and 1992 for the opening of the ] and entry into service began in 1989. They are all bi-current, {{convert|237.5|m|ftin|abbr=on}} long and {{convert|2.9|m|ftin|abbr=on}} wide. They weigh {{Convert|444|t|lb}} and are made up of two power cars and ten carriages with a capacity of 485 seats. They were built with a maximum speed of {{convert|300|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}} and 8,800 kW of power under 25 kV. The efficiency of the Atlantique with all seats filled has been calculated at 767 ], though with a typical occupancy of 60% it is about 460 PMPG (a Toyota Prius with three passengers is 144 PMPG).<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://strickland.ca/efficiency.html|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090301160114/http://strickland.ca/efficiency.html|url-status=dead|title=Energy Efficiency of different modes of transportation, accessed March 21, 2009|archivedate=1 March 2009}}</ref> | |||

| Modified unit 325 ] in 1990 on the LGV Atlantique before its opening. Modifications such as improved ], larger wheels and improved braking were made to enable speeds of over {{convert|500|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}}. The set was reduced to two power cars and three carriages to improve the power-to-weight ratio, weighing 250 tonnes. Three carriages, including the bar carriage in the centre, is the minimum possible configuration because of the ]s. | |||

| ===TGV Réseau=== | ===TGV Réseau=== | ||

| {{Main|SNCF TGV Réseau}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The first ] sets entered service in ]. 50 bi-current sets were ordered initially in ], supplemented by an order for 40 tri-current sets in ]/]. Ten of the tri-current sets carry the ] livery and are known as Thalys PBA (Paris-Brussels-Amsterdam) sets. The tri-current sets, as well as the standard French voltages, can operate under the ]' and ] 3kV DC supplies. | |||

| The first Réseau (Network) sets entered service in 1993. Fifty bi-current sets were ordered in 1990, supplemented by 40 tri-current sets in 1992/1993 (adding {{3,000 V DC}} system used on traditional lines in Belgum). Ten tri-current sets carry the ] (ex-]) livery and are known as the PBA (Paris-Brussels-Amsterdam) sets. | |||

| They are formed of two power cars (8,800 kW under 25 kV |

They are formed of two power cars (8,800 kW under 25 kV – as TGV Atlantique) and eight carriages, giving a capacity of 377 seats. They have a top speed of {{convert|320|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}}. They are {{convert|200|m|ftin|abbr=on}} long and are {{convert|2.90|m|ftin|abbr=on}} wide. The bi-current sets weigh 383 tonnes: owing to axle-load restrictions in Belgium the tri-current sets have a series of modifications, such as the replacement of steel with aluminum and hollow axles, to reduce the weight to under 17 t per axle. | ||

| Owing to early complaints of uncomfortable pressure changes when entering tunnels at high speed on the LGV Atlantique, the Réseau sets are now pressure-sealed. They can be coupled to a Duplex set. | |||

| === |

===TGV Duplex=== | ||

| {{Main|TGV Duplex}} | |||

| ] trains connect ] with ] and ] through the ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] train is essentially a long TGV, modified for use in the United Kingdom and in the ]. In the UK, it is known under the ] classification system as a Class 373 Electric Multiple Unit. In the planning stages, it was also known as the TransManche Super Train (Cross-channel Super Train). The trains were built by GEC-Alsthom (now ]) at its sites in La Rochelle (France), Belfort (France) and Washwood Heath (England), entering service in ]. | |||

| The Duplex was built to increase TGV capacity without increasing train length or the number of trains. Each carriage has two levels, with access doors at the lower level taking advantage of low French ]. A staircase gives access to the upper level, where the gangway between carriages is located. There are 512 seats per set. On busy routes such as Paris-Marseille they are operated in pairs, providing 1,024 seats in two Duplex sets or 800 in a Duplex set plus a Reseau set. Each set has a wheelchair accessible compartment. | |||

| After a lengthy development process starting in 1988 (during which they were known as the TGV-2N) the original batch of 30 was built between 1995 and 1998. Further deliveries started in 2000 with the Duplex fleet now totaling 160 units, making it the backbone of the SNCF TGV-fleet. They weigh 380 tonnes and are {{convert|200|m|ftin|abbr=on}} long, made up of two power cars and eight carriages. Extensive use of aluminum means that they weigh not much more than the TGV Réseau sets they supplement. The bi-current power cars provide 8,800 kW, and they have a slightly increased speed of {{convert|320|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}}. | |||

| Two types were built: the Three Capitals sets consist of two power cars and eighteen carriages, including two powered bogies; the North of London sets consist of two power cars and only fourteen carriages, again with two powered bogies. Full sets of both types consist of two identical half-sets which are not articulated in the middle, so that in case of emergency in the Channel Tunnel, one half can be uncoupled and leave the tunnel. Each half-set is numbered separately. | |||

| Duplex TGVs run on all of French high-speed lines.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://electric-rly-society.org.uk/the-history-of-the-french-high-speed-rail-network-and-tgv/|author=The Electric Railway Society|title=The History of the French High Speed Rail Network and TGV|date=March 2015|access-date=2016-10-19|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| 38 full sets, plus one spare power car, were ordered by the railway companies involved: 16 by SNCF, 4 by ], and 18 by ], of which seven were North of London sets. Upon privatisation of ] by the UK Government, the sets were bought by ] who named the subsidiary ], now managed by a consortium of companies made up of the ] (40%), SNCF (35%), SNCB (15%) and ] (10%). | |||

| ===TGV POS=== | |||

| The Three Capitals sets operate at a maximum speed of 300 km/h (186 mph), with the power cars supplying 12,240 kW of power. They are 394 m (1,293 ft) long and have a capacity of 766 seats, weighing a total of 752 tonnes (829 tons). The North of London sets have a capacity of 558 seats. All of the trains are at least tri-current and are able to operate on 25 kV, 50 Hz AC (on LGVs, including the ], and on UK overhead electrified lines), 3 kV DC (on ''lignes classiques'' in Belgium) and 750 V DC on the UK Southern Region ] network. The third rail system will become superfluous in 2007 when the second phase of the ] is completed between London and the Channel Tunnel, as it uses 25 kV, 50 Hz AC exclusively. Five of the Three Capitals sets owned by SNCF are quadri-current and are also able to operate on French ''lignes classiques'' at 1500 V DC. | |||

| {{Main|TGV POS}} | |||

| ] | |||

| TGV POS (Paris-Ostfrankreich-Süddeutschland or Paris-Eastern France-Southern Germany) are used on the LGV Est. | |||

| They consist of two Duplex power cars with eight TGV Réseau-type carriages, with a power output of 9,600 kW and a top speed of {{convert|320|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}}. Unlike TGV-A, TGV-R and TGV-D, they have asynchronous motors, and isolation of an individual motor is possible in case of failure. | |||

| Three of the Three Capitals sets owned by SNCF are used for French domestic use and currently carry the silver and blue TGV livery. The North of London Eurostar sets have never seen international use but were originally intended to provide direct services from continental Europe to UK cities north of London, using the ] and the ]. These never came to fruition, however, and a few of the sets were leased to ] for use on its ''White Rose'' service between London and Leeds, with two of them carrying GNER's dark blue livery, although the lease will be ending in December 2005. | |||

| ===TGV |

===Avelia Euroduplex (TGV 2N2)=== | ||

| {{Main|Euroduplex}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The bi-current TGV 2N2 (Avelia Euroduplex) can be regarded as the 3rd generation of Duplex. The series was commissioned from December 2011 for links to Germany and Switzerland (tri-current trains) and to cope with the increased traffic due to the opening of the LGV Rhine-Rhone. | |||

| The ] was built to increase TGV capacity without increasing train length, or number of trains. Each carriage has two levels, with access doors at the lower level taking advantage of low French ]. A staircase provides access to the upper level. This layout provides a capacity of 512 seats per set. On many routes they are operated in pairs, providing 1,024 seats in a single train. | |||

| They are numbered from 800 and are limited to {{convert|320|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}}. ERTMS makes them compatible to allow access to Spain similar to ]. | |||

| After a lengthy development process starting in 1988, they were built in two batches: thirty were built between ] and ], then a further thirty-four between ] and ]. They weigh 386 tonnes (425 tons) and are 200 m (656 ft) long, made up of two power cars and eight ] carriages. Extensive use of aluminium means that they do not weigh much more than the TGV Réseau sets they supplement. The bi-current power cars provide a total power of 8,800 kW, and they have a slightly increased speed over their predecessors of 320 km/h (199 mph). | |||

| ===TGV M Avelia Horizon=== | |||

| {{Main|SNCF TGV M}} | |||

| The design that emerged from the process was named ], and in July 2018 SNCF ordered 100 trainsets with deliveries expected to begin in 2024.<ref>{{cite magazine | url=https://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/sncf-confirms-tgv-of-the-future-order.html | title=SNCF confirms TGV of the Future order | magazine=Railway Gazette International | date=26 July 2018 | access-date=2 August 2018 | archive-date=27 July 2018 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180727000853/http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/sncf-confirms-tgv-of-the-future-order.html | url-status=dead }}</ref> They are expected to cost €25 million per 8-car set. | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| ==TGV technology outside France== | |||

| ===Thalys PBKA=== | |||

| TGV technology has been adopted in a number of other countries:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.francetech.gouv.fr/biblioth/docu/dossiers/sect/pdf/ferrogb.pdf |title=French Railway Industry: The paths of excellence |publisher=DGE/] |access-date=2009-05-01 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081121004813/http://www.francetech.gouv.fr/biblioth/docu/dossiers/sect/pdf/ferrogb.pdf |archive-date=21 November 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| Unlike Thalys PBA sets, the PBKA (Paris-Brussels-Köln (Cologne)-Amsterdam) sets were built exclusively for the Thalys service. They are technologically similar to TGV Duplex sets, but do not feature bi-level carriages. All of the trains are quadri-currrent, operating under 25 kV, 50 Hz AC (LGVs), 15 kV 16 2/3 Hz AC (Germany, Switzerland), 3 kV DC (Belgium) and 1,500 V DC (Low Countries and French ''lignes classiques''). Their top speed in service is 300 km/h (186 mph) under 25 kV, 50 Hz AC, with two power cars supplying 8,800 kW of power. They have eight carriages and are 200 m (656 ft) long, weighing a total of 385 tonnes (424 tons). They have a capacity of 377 seats. | |||

| * ] (''Alta Velocidad Española'') in Spain with the ] based on the ].<ref name="Ryo Takagi">{{cite web|url=http://www.jrtr.net/jrtr40/pdf/f04_tak.pdf|title=High-speed Railways:The last ten years|first=Ryo|last=Takagi|publisher=Japan Railway & Transport Review|access-date=2009-05-01|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090620081824/http://www.jrtr.net/jrtr40/pdf/f04_tak.pdf|archive-date=20 June 2009|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| * ] operates international high-speed services connecting France with Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. Several trainsets use TGV technology (], ], ]). | |||

| * ] (KTX) in South Korea with ] (based on the ]) and ].<ref name="irj-kim">{{cite news|url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BQQ/is_/ai_n25433622 |title=Korea develops high-speed ambitions: a thorough programme of research and development will soon deliver results for Korea's rail industry in the form of the indigenous KTX II high-speed train. Dr Kihwan Kim of the Korea Railroad Research Institute explains the development of the new train |date=May 2008 |publisher=BNET (International Railway Journal) |access-date=2008-12-31 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081216045744/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BQQ/is_/ai_n25433622 |archive-date=16 December 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| * ], a high-speed ] built by Alstom and ] for the ] in the United States. The Acela power cars use several TGV technologies including the motors, electrical/drivetrain system (rectifiers, inverters, regenerative braking technology), and ]. However, they are strengthened to meet U.S. ] crash standards.<ref name="TGVweb Acela Express page">{{cite web|url=http://www.trainweb.org/tgvpages/acela.html |title=TGVweb Acela Express page|date=May 2009|publisher=TGVweb|access-date=2009-05-10}}</ref> The Acela's tilting, non-articulated carriages are derived from the Bombardier's ] train and also meet crash standards.<ref name="TGVweb Acela Express page" /> | |||

| * ], the replacement for the Acela Express in the United States. Expected to enter service in 2023. | |||

| * The ] agreed to a €2 billion contract for ] to build ], an LGV between ] and ] which opened in 2018 using ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.magharebia.com/cocoon/awi/xhtml1/en_GB/features/awi/features/2009/04/15/feature-02 |title=Engineers begin work on Moroccan high-speed rail link|date=May 2008|publisher=BNET (International Railway Journal)|access-date=2009-04-09}}</ref> | |||

| *Italian open-access high-speed operator ] signed up with ] to purchase 25 ] 11-car sets.<ref name="alstomtoannounce">{{cite magazine | url=http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view//alstom-awarded-italian-agv-contract.html | title=Alstom awarded Italian AGV contract | magazine=] | date=17 January 2008 | url-status=dead | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120415003224/http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/alstom-awarded-italian-agv-contract.html | archive-date=15 April 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Future TGVs== | |||

| 17 trains were ordered: nine by SNCB, six by SNCF and two by ]. ] contributed to financing two of the SNCB sets. | |||

| SNCF and Alstom are investigating new technology that could be used for high-speed transport. | |||

| The development of TGV trains is being pursued in the form of the '']'' (AGV) high-speed multiple unit with motors under each carriage.<ref>{{cite magazine | url=http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/10/alstom-unveils-agv-prototype-train.html | title=Alstom unveils AGV prototype train | magazine=] | date=5 February 2008 | access-date=7 September 2009 | archive-date=15 April 2012 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120415003003/http://www.railwaygazette.com/news/single-view/view/alstom-unveils-agv-prototype-train.html | url-status=dead }}</ref> Investigations are being carried out with the aim of producing trains at the same cost as TGVs with the same safety standards. AGVs of the same length as TGVs could have up to 450 seats. The target speed is {{convert|360|km/h|mph|0}}. The prototype AGV was unveiled by Alstom on 5 February 2008.<ref name=bbc20080205>{{cite news | title=France unveils super-fast train | url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7227807.stm | work=] | date=5 February 2008 | access-date=2008-02-05}}</ref> | |||

| Italian operator ] is the first customer for the AGV, and became the first open-access high-speed rail operator in Europe, starting operation in 2011.<ref name="alstomtoannounce"/> | |||

| ===TGV POS=== | |||

| TGV POS, standing for Paris-Ostfrankreich-Suddeutschland (Paris-Eastern France-Southern Germany) are under test for use on the LGV Est, currently under construction. | |||

| The design process of the next generation of TGVs began in 2016 when SNCF and Alstom signed an agreement to jointly develop the trainsets, with goals of reducing purchase and operating costs, as well as improved interior design.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.railjournal.com/index.php/high-speed/next-generation-tgv-to-enter-service-in-2022.html|title=Next-generation TGV to enter service in 2022|first=Keith|last=Barrow|date=7 September 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The trains will consist of two power cars with eight TGV Réseau type carriages, with a total power output of 9,600 kW and a top speed of 320 km/h (199 mph). Unlike TGV-A, TGV-R and TGV-D, it has adopted asynchronous motors and in case of failure, isolation of an individual motor in a powered bogie is possible. They will weigh 423 tonnes (466 tons). | |||

| ==Lines in operation== | |||

| ==Network== | |||

| {{Main|High-speed rail in France#Network}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In June 2021, there were approximately {{convert|2800|km||0|abbr=on}} of ''{{lang|fr|]}}'' (LGV), with four additional line sections under construction. The current lines and those under construction can be grouped into four routes radiating from Paris. | |||

| France has around 1,200 ] of LGV built over the past 20 years, with four new lines either proposed or under construction. | |||

| ==Accidents== | |||

| ===Existing lines=== | |||

| {{Main|TGV accidents}} | |||

| In over three decades of operation, the TGV has not recorded a single passenger fatality in an accident on normal, high-speed service. There have been several accidents, including four derailments at or above {{convert|270|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}}, but in only one of these—a test run on a new line—did carriages overturn. | |||

| This safety record is credited in part to the stiffness that the articulated design lends to the train. There have been fatal accidents involving TGVs on ''lignes classiques'', where the trains are exposed to the same dangers as normal trains, such as ]s. These include one ] unrelated to the speed at which the train was traveling. | |||

| # ] (] ] to ]-Perrache), the first LGV (opened ]) | |||

| # ] (Paris ] to ] and ]) (opened ]) | |||

| # ] (Paris ] to ] and ] and on towards ], ] and ]) (opened ]) | |||

| # ] (An extension of LGV Sud-Est: Lyon to ] Saint-Charles) (opened ]) | |||

| # LGV Interconnexion (LGV Sud-Est to LGV Nord Europe, east of Paris) | |||

| === |

===On LGVs=== | ||

| * 14 December 1992: TGV 920 from Annecy to Paris, operated by set 56, derailed at {{convert|270|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}} at Mâcon-Loché TGV station (]). A previous emergency stop had caused a wheel flat; the bogie concerned derailed while crossing the ] at the entrance to the station. No one on the train was injured, but 25 passengers waiting on the platform for another TGV were slightly injured by ballast that was thrown up from the trackbed. | |||

| * 21 December 1993: TGV 7150 from Valenciennes to Paris, operated by set 511, derailed at {{convert|300|km/h|4=0|abbr=on}} at the site of Haute Picardie TGV station, before it was built. Rain had caused a hole to open up under the track; the hole dated from the ] but had not been detected during construction. The front power car and four carriages derailed but remained aligned with the track. Of the 200 passengers, one was slightly injured. | |||

| * 5 June 2000: Eurostar 9073 from Paris to London, operated by sets 3101/2 owned by the ], derailed at {{convert|250|km/h|mph|0|abbr=on|sigfig=3}} in the ] region near ].<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.trainweb.org/tgvpages/wrecks.html | title=TGV Accidents | publisher=trainweb.org | date=1 May 2009}}</ref> The transmission assembly on the rear bogie of the front power car failed, with parts falling onto the track. Four bogies out of 24 derailed. Out of 501 passengers, seven were bruised<ref>'''' ] (5 June 2000), Retrieved 24 November 2005</ref> and others treated for shock.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/778669.stm |title=Eurostar train derails in France | work = ] |access-date=2009-05-10 | date=5 June 2000}}</ref> | |||

| * 14 November 2015: TGV 2369 was involved in the ], near Strasbourg, while being tested on the then-unopened second phase of the LGV Est. The derailment resulted in 11 deaths among those aboard, while 11 others aboard the train were seriously injured.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-europe-34825385/at-least-11-killed-in-french-tgv-high-speed-train-crash|title=At least 11 killed in rail crash in France|work=BBC News|access-date=2017-12-20}}</ref> Excessive speed has been cited as the cause.<ref name=dna>{{cite news|url=http://www.dna.fr/actualite/2015/11/14/un-train-se-renverse-et-prend-feu-a-eckwersheim-pres-de-strasbourg|title=Une rame d'essai d'un TGV se renverse et prend feu à Eckwersheim, près de Strasbourg : cinq morts|language=fr|newspaper=Dernieres Nouvelles D'Alsace|date=14 November 2015|last1=Bach|first1=Christian|last2=Poivret|first2=Aurélien}}</ref> | |||

| ===On classic lines=== | |||

| # LGV ''Est'' (Paris Gare de l'Est-]) (under construction, to open ]) | |||

| * 31 December 1983: A bomb allegedly planted by the terrorist organisation of ] exploded on board a TGV from Marseille to Paris; two people were killed. | |||

| # LGV ''Rhin-Rhône'' (Strasbourg-]) | |||

| *28 September 1988: TGV 736, operated by set 70 "Melun", collided with a lorry carrying an electric transformer weighing 100 tonnes that had become stuck on a level crossing in ], Isère. The vehicle had not obtained the required crossing permit from the French ''Direction départementale de l'équipement''. The weight of the lorry caused a very violent collision; the train driver and a passenger died, and 25 passengers were slightly injured. | |||

| # ]-]-], which would connect the TGV to the Spanish ] network | |||

| * 4 January 1991: after a brake failure, TGV 360 ran away from Châtillon depot. The train was directed onto an unoccupied track and collided with the car loading ramp at Paris-Vaugirard station at {{convert|60|km/h|abbr=on}}. No one was injured. The leading power car and the first two carriages were severely damaged, and were rebuilt. | |||

| # ]-]-] (]), which would extend the TGV into ] | |||

| * 25 September 1997: TGV 7119 from Paris to ], operated by set 502, collided at {{convert|130|km/h|abbr=on}} with a 70 tonne asphalt paving machine on a level crossing at Bierne, near Dunkerque. The power car spun round and fell down an embankment. The front two carriages left the track and came to a stop in woods beside the track. Seven people were injured. | |||

| # LGV Sud-Ouest ]-] and LGV Bretagne-Pays de la Loire ]-], extending the LGV Atlantique | |||

| * 31 October 2001: TGV 8515 from Paris to Irun derailed at {{convert|130|km/h|abbr=on}} near ] in southwest France. All ten carriages derailed and the rear power unit fell over. The cause was a broken rail. | |||

| # ]-]-] | |||

| * 30 January 2003: a TGV from Dunkerque to Paris collided at {{convert|106|km/h|abbr=on}} with a heavy goods vehicle stuck on the level crossing at Esquelbecq in northern France. The front power car was severely damaged, but only one bogie derailed. Only the driver was slightly injured. | |||

| # ]-] | |||

| * 19 December 2007: a TGV from Paris to Geneva collided at about {{convert|100|km/h|abbr=on}} with a truck on a level crossing near ] in eastern France, near the Swiss border. The driver of the truck died; on the train, one person was seriously injured and 24 were slightly injured.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://uk.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUKL1955864420071219 |title=French TGV train hits lorry and kills one |publisher=Reuters UK |date=19 December 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081207155431/http://uk.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUKL1955864420071219 |archive-date=7 December 2008}}</ref> | |||

| # ] - ] - ] (LGV ''Étoile du Nord'') | |||

| * 17 July 2014: a ] train ran into the rear of a TGV ]. Forty people were injured. | |||

| Following the number of accidents at level crossings, an effort has been made to remove all level crossings on ''lignes classiques'' used by TGVs. The ''ligne classique'' from ] to ] at the end of the LGV Atlantique has no level crossings as a result. | |||

| Amsterdam and Cologne are already served by ] TGV trains running on ordinary track, though these connections are being upgraded to high-speed rail. London is presently served by ] TGV trains running at high speeds via the partially-completed ] and then at normal speeds along regular tracks through the London suburbs, although Eurostar will use a fully-segregated line once Section 2 of the link is complete. | |||

| == |

==Protests against the TGV== | ||

| The first environmental protests against the building of an LGV occurred in May 1990 during the planning stages of the LGV Méditerranée. Protesters blocked a railway viaduct to protest against the planned route, arguing that it was unnecessary, and that trains could keep using existing lines to reach Marseille from Lyon.<ref>{{Cite magazine |date=2 June 1990 |title= High-Speed Protest |url= https://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=mg12617192.800 |access-date= 15 November 2005 |magazine= New Scientist |archive-date=17 December 2007 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20071217083818/https://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=mg12617192.800 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| The ] (]-]-]), which would connect the TGV network to the Italian ] network, has been the subject of demonstrations in Italy. While most Italian political parties agree on the construction of this line, some inhabitants of the towns where construction would take place oppose it vehemently.{{citation needed|date=November 2012}} The concerns put forward by the protesters centre on storage of dangerous materials mined during tunnel boring, like ] and perhaps ], in the open air.{{Citation needed|date=May 2014}} This health danger could be avoided by using more expensive techniques for handling radioactive materials.{{Citation needed|date=September 2010}} A six-month delay in the start of construction has been decided in order to study solutions. In addition to the concerns of the residents, RFB – a ten-year-old national movement – opposes the development of Italy's ] ] network as a whole.<ref>{{Cite web|date=1 November 2005|title=Environmental Protesters Block French-Italian Railway|url=http://www.planetark.com/dailynewsstory.cfm/newsid/33266/story.htm|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071007155404/http://www.planetark.com/dailynewsstory.cfm/newsid/33266/story.htm|archive-date=2007-10-07|access-date=1 November 2005|website=planetark.com}}</ref> | |||

| TGV technology has been adopted in a number of other countries: | |||