| Revision as of 18:36, 30 May 2009 edit77.29.217.208 (talk) →Participation← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:59, 13 January 2025 edit undoSjones23 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers102,349 edits →Rules: Minor ce for duplication issues.Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Annual international song competition}} | |||

| {{redirect|Eurovision}}{{for|this year's Contest|Eurovision Song Contest 2009}}{{for|next year's Contest|Eurovision Song Contest 2010}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Eurovision|the most recent contest|Eurovision Song Contest 2024|the upcoming contest|Eurovision Song Contest 2025|other uses}} | |||

| ] was introduced for the ] to create a consistent visual identity. The host country's flag appears in the heart.]] | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| The '''Eurovision Song Contest''' ({{lang fr|Concours Eurovision de la chanson}})<ref>{{cite web|publisher=EBU.ch|url=http://www.ebu.ch/departments/television/pdf/Winners-Palmares_56-02.pdf|title=Winners of the Eurovision Song Contest |format=PDF|accessdate=2007-12-26}}</ref> is an annual music competition held among active member countries of the ] (EBU). | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox television | |||

| | name = {{noitalic|Eurovision Song Contest}} | |||

| | image = Eurovision Song Contest.svg | |||

| | image_size = 250 | |||

| | image_alt = The current Eurovision Song Contest logo, in use since 2015 | |||

| | caption = Logo since 2015 | |||

| | alt_name = {{Unbulleted list|{{noitalic|Eurovision}}|{{noitalic|Eurosong}}|{{noitalic|ESC}}}} | |||

| | genre = ] | |||

| | creator = ] | |||

| | based_on = ] | |||

| | developer = | |||

| | presenter = ] | |||

| | country = ] | |||

| | language = English and French | |||

| | num_episodes = {{Plainlist| | |||

| * 68 contests | |||

| * 104 live shows | |||

| }} | |||

| | producer = | |||

| | location = ] | |||

| | runtime = {{Plainlist| | |||

| * ~2 hours (semi-finals) | |||

| * ~4 hours (finals) | |||

| }} | |||

| | company = ]<br />] | |||

| | first_aired = {{Start date|1956|05|24|df=y}} | |||

| | last_aired = present | |||

| | related = {{Plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * '']'' | |||

| * '']'' | |||

| }} | |||

| | italic_title = no | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Eurovision Song Contest''' ({{Langx|fr|Concours Eurovision de la chanson}}), often known simply as '''Eurovision''', is an international ] organised annually by the ]. Each ] submits an original song to be performed live and transmitted to national broadcasters via the ], with competing countries then casting votes for the other countries' songs to determine a winner. | |||

| Each member country submits a ] to be performed on ] and then casts votes for the other countries' songs to determine the most popular song in the competition. Each country participates via one of their national EBU-member ]s, whose task it is to select a ] and a song to represent their country in the international competition. | |||

| The Contest has been broadcast every year since its inauguration in 1956 and is one of the longest-running ]s in the world. It is also one of the most-watched non-sporting events in the world,<ref>{{cite web |publisher= eurovision.tv |url= http://web.archive.org/web/20060525094524/http://www.eurovision.tv/english/2513.htm |title= Live Webcast| accessdate=2006-05-25}}</ref> with audience figures having been quoted in recent years as anything between 100 million and 600 million internationally.<ref>{{cite web |publisher= Aljazeera.net|date= 21 May 2006|url= http://english.aljazeera.net/English/archive/archive?ArchiveId=22908 |title= Finland wins Eurovision contest|accessdate=2007-05-08}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Matthew Murray| url= http://www.museum.tv/archives/etv/E/htmlE/eurovisionso/eurovisionso.htm |title= Eurovision Song Contest - International Music Program |publisher = museum.tv | accessdate=2006-07-15}}</ref> Eurovision has also been broadcast outside Europe to such places as ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and the ], despite the fact that these countries cannot compete.<ref>{{cite web|publisher= ]|year=2002|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2002/05_may/16/eurovision_trivia.pdf |title= Eurovision Trivia|accessdate=2006-07-18 |format= PDF}}</ref> Since the year 2000, the Contest has also been broadcast over the ],<ref>{{cite web|author= Philip Laven |month= July | year= 2002 |url= http://www.ebu.ch/en/technical/trev/trev_291-editorial.html |publisher = European Broadcasting Union | title= Webcasting and the Eurovision Song Contest|accessdate=2006-08-21}}</ref> with more than 74,000 people in almost 140 countries having watched the 2006 edition online.<ref>{{cite web |publisher=Octoshape |date=8 June 2006 |url= http://www.streamingmedia.com/press/view.asp?id=4907 |title= Eurovision song contest 2006 - live streaming |accessdate=2006-08-21}}</ref> The contest has a ] channel, with over 2.5 million channel views and 12,000 subscribers. | |||

| The contest was inspired by and based on Italy's national ], held in the ] since 1951. Eurovision has been held annually since 1956 (except for {{Escyr|2020}} due to the ]), making it the longest-running international music competition on television and one of the world's longest-running television programmes. Active members of the EBU and invited associate members are eligible to compete; {{as of|2024|lc=y|post=,}} ] have participated at least once. Each participating broadcaster sends an original song of three minutes duration or less to be performed live by a singer or group of up to six people aged 16 or older. Each country awards 1–8, 10 and 12 points to their ten favourite songs, based on the views of an assembled group of music professionals and the country's viewing public, with the song receiving the most points declared the winner. Other performances feature alongside the competition, including a specially-commissioned opening and interval act and guest performances by musicians and other personalities, with past acts including ], ], ], ], ] and the first performance of '']''. Originally consisting of a single evening event, the contest has expanded as new countries joined (including countries outside of Europe, such as {{Esccnty|Israel}} and {{Esccnty|Australia}}), leading to the introduction of relegation procedures in the 1990s, before the creation of semi-finals in the 2000s. {{As of|2024|post=,}} {{Esccnty|Germany}} has competed more times than any other country, having participated in all but ] edition, while {{Esccnty|Ireland}} and {{Esccnty|Sweden}} both hold the record for the most victories, with seven wins each in total. | |||

| == Origins == | |||

| Traditionally held in the country that won the preceding year's event, the contest provides an opportunity to promote the host country and city as a tourist destination. Thousands of spectators attend each year, along with journalists who cover all aspects of the contest, including rehearsals in venue, press conferences with the competing acts, in addition to other related events and performances in the host city. Alongside the generic Eurovision logo, a unique theme is typically developed for each event. The contest has aired in countries across all continents; it has been ] via the official Eurovision website since 2001. Eurovision ranks among the world's most watched non-sporting events every year, with hundreds of millions of viewers globally. Performing at the contest has often provided artists with a local career boost and in some cases long-lasting international success. Several of the ] in the world have competed in past editions, including ], ], ], ] and ]; some of the world's ] have received their first international performance on the Eurovision stage. | |||

| {{further|]}} | |||

| While having gained popularity with the viewing public in both participating and non-participating countries, the contest has also been the subject of criticism for its artistic quality as well as a perceived political aspect to the event. Concerns have been raised regarding political friendships and rivalries between countries potentially having an impact on the results. Controversial moments have included participating countries withdrawing at a late stage, censorship of broadcast segments by broadcasters, as well as political events impacting participation. Likewise, the contest has also been criticised for an over-abundance of elaborate stage shows at the cost of artistic merit. Eurovision has, however, gained popularity for its ] appeal, its musical span of ] and international styles, as well as emergence as part of ], resulting in a large, active fanbase and an influence on popular culture. The popularity of the contest has led to the creation of several similar events, either organised by the EBU or created by external organisations; several special events have been organised by the EBU to celebrate select anniversaries or as a replacement due to cancellation. | |||

| In the 1950s, as a ] rebuilt itself, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU)—based in ]—came up with the idea of an international ] song contest, to be transmitted simultaneously to all countries of the union. This was conceived during a meeting in ] in 1955 by ], a Swiss working for the EBU.<ref name="GoldenJubilee">{{cite web| author= Patrick Jaquin |date= 1 December 2004|url= http://www.ebu.ch/en/union/diffusion_on_line/television/tcm_6-8971.php |title= Eurovision's Golden Jubilee | publisher = European Broadcasting Union | accessdate= 2006-07-15}}</ref> The competition was based upon the existing ] held in ],<ref>{{cite web |publisher= bbc.co.uk |year= 2003 |url= http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio2/eurovision/2003/history |title= History of Eurovision |accessdate= 2006-07-20}}</ref> and was also seen as a technological experiment in ]: in those days, it was a very ambitious project to join many countries together in a wide-area international network. ] did not exist, and the so-called ] comprised a terrestrial ].<ref>{{cite web|author= George T. Waters |date= Winter 1994 |url= http://www.ebu.ch/en/technical/trev/trev_262-editorial.html |title= Eurovision: 40 years of network development, four decades of service to broadcasters |publisher = European Broadcasting Union | accessdate=2006-07-15}}</ref> The name "Eurovision" was first used in relation to the EBU's network by ] journalist George Campey in the '']'' in 1951.<ref>{{cite web |author= David Fisher |date= 28 January 2006|url= http://www.terramedia.co.uk/Chronomedia/years/1951.htm |title= Media Statistics: 1951 |publisher = Terra Media | accessdate= 2006-07-15}}</ref> | |||

| == Origins and history == | |||

| The first Contest was held in the town of ], Switzerland, on 24 May 1956. Seven countries participated—each submitting two songs, for a total of 14. This was the only Contest in which more than one song per country was performed: since 1957 all Contests have allowed one entry per country.<ref name="milestones">{{cite web |publisher= eurovision.tv |year= 2005 |url= http://web.archive.org/web/20060526065558/http://www.eurovision.tv/english/611.htm |title= Historical Milestones |accessdate=2006-05-26}}</ref> The ] was won by the host nation, Switzerland. | |||

| {{Further|History of the Eurovision Song Contest}} | |||

| ], the winner of the first Eurovision Song Contest in {{Escyr|1956}}, performing at the {{Escyr|1958|3=1958 contest}}]] | |||

| The Eurovision Song Contest was developed by the ] (EBU) as an experiment in ] broadcasting and a way to produce cheaper programming for national broadcasting organisations.<ref>{{Cite web |date=27 May 2019 |title=The Origins of Eurovision |url=https://eurovision.tv/history/origins-of-eurovision |access-date=15 April 2023 |website=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Vuletic |first=Dean |title=Postwar Europe and the Eurovision Song Contest |date=2018 |publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=9781474276276 <!-- |access-date=15 April 2023-->}}</ref> The word "Eurovision" was first used by British journalist George Campey in the '']'' in 1951, when he referred to a ] programme being relayed by Dutch television.{{sfn|Roxburgh|2012|pp=93–96}}<ref name="GoldenJubilee">{{Cite web |last=Jaquin |first=Patrick |date=1 December 2004 |title=Eurovision's Golden Jubilee |url=http://www.ebu.ch/en/union/diffusion_on_line/television/tcm_6-8971.php |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040811033906/http://www.ebu.ch/en/union/diffusion_on_line/television/tcm_6-8971.php |archive-date=11 August 2004 |access-date=18 July 2009 |publisher=]}}</ref> Following several events broadcast internationally via the ] in the early 1950s, including the ] in 1953, an EBU committee, headed by ], was formed in January 1955 to investigate new initiatives for cooperation between broadcasters, which approved for further study a European song competition from an idea initially proposed by ] manager ].<ref name="GoldenJubilee" /><ref name="Eurovision network">{{Cite web |title=Eurovision: About us – who we are |url=https://www.eurovision.net/about/whoweare |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Sommerlad |first=Joe |date=18 May 2019 |title=Eurovision 2019: What exactly is the point of the annual song contest and how did it begin? |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/tv/news/eurovision-2019-song-contest-what-is-the-point-purpose-pop-history-a8916801.html |access-date=27 June 2020 |website=]}}</ref> The EBU's general assembly agreed to the organising of the song contest in October 1955, under the initial title of the ''European Grand Prix'', and accepted a proposal by the Swiss delegation to host the event in ] in the spring of 1956.{{sfn|Roxburgh|2012|pp=93–96}}<ref name="GoldenJubilee" />{{sfn|O'Connor|2010|pp=8–9}} The Italian ], held since 1951, was used as a basis for the initial planning of the contest, with several amendments and additions given its international nature.{{sfn|Roxburgh|2012|pp=93–96}} | |||

| Seven countries participated in the {{Escyr|1956||first contest}}, with each country represented by two songs; the only time in which multiple entries per country were permitted.<ref name="Nutshell">{{Cite web |date=31 March 2017 |title=Eurovision Song Contest: In a Nutshell |url=https://eurovision.tv/history/in-a-nutshell |access-date=27 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref name="Facts & Figures">{{Cite web |date=12 January 2017 |title=Eurovision Song Contest: Facts & Figures |url=https://eurovision.tv/about/facts-and-figures |access-date=27 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> The winning song was "]", representing the host country Switzerland and performed by ].<ref name="Winners">{{Cite web |title=Eurovision Song Contest: Winners |url=https://eurovision.tv/winners |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180512231240/https://eurovision.tv/winners |archive-date=12 May 2018 |access-date=23 May 2021 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Voting during the first contest was held behind closed doors, with only the winner being announced on stage; the use of a scoreboard and public announcement of the voting, inspired by the BBC's '']'', has been used since 1957.{{sfn|Roxburgh|2012|p=152}} The tradition of the winning country hosting the following year's contest, which has since become a standard feature of the event, began in 1958.{{sfn|O'Connor|2010|pp=12–13}}{{sfn|Roxburgh|2012|p=160}} Technological developments have transformed the contest: ] began in {{Escyr|1968}}; ] in {{Escyr|1985}}; and ] in {{Escyr|2000}}.<ref name="Eurovision network" /><ref name="London 68">{{Cite web |title=Eurovision Song Contest: London 1968 |url=https://eurovision.tv/event/london-1968 |access-date=5 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref name="Webcasting">{{Cite web |last=Laven |first=Philip |date=July 2002 |title=Webcasting and the Eurovision Song Contest |url=http://www.ebu.ch/en/technical/trev/trev_291-editorial.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080528091401/http://www.ebu.ch/en/technical/trev/trev_291-editorial.html |archive-date=28 May 2008 |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref> Broadcasts in ] began in 2005 and in ] since 2007, with ] tested for the first time in 2022.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Polishchuk |first=Tetiana |date=17 May 2005 |title=Eurovision to Be Broadcast in Widescreen, With New Hosts |url=https://day.kyiv.ua/en/article/culture/eurovision-be-broadcast-widescreen-new-hosts |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201122170009/https://day.kyiv.ua/en/article/culture/eurovision-be-broadcast-widescreen-new-hosts |archive-date=22 November 2020 |access-date=23 February 2021 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref name="Helsinki 07" /><ref name=":9">{{Cite web |last=Cafarelli |first=Donato |date=23 April 2022 |title=Eurovision Song Contest 2022: la Rai trasmetterà l'evento per la prima volta in 4K |trans-title=Eurovision Song Contest 2022: Rai will broadcast the event for the first time in 4K |url=https://www.eurofestivalnews.com/2022/04/23/eurovision-song-contest-2022-rai-4k/ |access-date=23 April 2022 |website=Eurofestival News |language=it-IT}}</ref> | |||

| The programme was first known as the "Eurovision Grand Prix". This "Grand Prix" name was adopted by the ] countries, where the Contest became known as "''Le Grand-Prix Eurovision de la Chanson Européenne''".<ref>{{cite web |author= Franck Thomas & Laurent Balmer |year= 1999 |url= http://web.archive.org/web/20060502192602/http://www.eurovision-fr.net/histoire/histoire5659.php |title= Histoire 1956 à 1959 | publisher = eurovision-fr.net | accessdate= 2006-07-17}} {{fr icon}}</ref> The "Grand Prix" has since been dropped and replaced with "''Concours''" (contest) in these countries. The Eurovision Network is used to carry many news and sports programmes internationally, among other specialised events organised by the EBU.<ref>{{cite web |publisher= European Broadcasting Union |date= 14 June 2005|url= http://www.ebu.ch/departments/operations/ops.php |title= The EBU Operations Department |accessdate= 2006-07-20}}</ref> However, the Song Contest has by far the highest profile of these programmes, and has long since become synonymous with the name "Eurovision". | |||

| By the 1960s, between 16 and 18 countries were regularly competing each year.<ref name="ESC History">{{Cite web |title=Eurovision Song Contest: History by events |url=https://eurovision.tv/events |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170825083217/https://eurovision.tv/events |archive-date=25 August 2017 |access-date=27 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Countries from outside the traditional ] began entering the contest, and countries in Western Asia and North Africa started competing in the 1970s and 1980s. Apart from Yugoslavia (a member of the ] and not seen as part of the Eastern Bloc at the time) no socialist or communist country ever participated. However, the ] which held four editions in the 1970s and 1980s (and a one-off revival in 2008) saw the participation of ] and ] members – including some from outside Europe like Canada – in addition to the Eastern Bloc countries of ] that had set up the contest. Only after the ] did other countries from ] participate for the first time – some of those countries having gained or regained their independence in the course of the breakup of Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and the Soviet Union. As a consequence, more countries were now applying than could feasibly participate in a one-night-event of reasonable length. Numerous solutions to this problem were tried out over the years. The {{Escyr|1993||1993 contest}} included a contest called ] which was a pre-qualifying round for seven of these new countries, and from {{Escyr|1994}}, ] were introduced to manage the number of competing entries, with the poorest performing countries barred from entering the following year's contest.<ref name="ESC History" /><ref>{{Cite web |title=Eurovision Song Contest 1993 |url=https://eurovision.tv/event/millstreet-1993 |access-date=27 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> From 2004, the contest expanded to become a multi-programme event, with a semi-final at the {{Escyr|2004||49th contest}} allowing all interested countries to compete each year; a second semi-final was added to each edition from 2008.<ref name="Facts & Figures" /><ref name="ESC History" /> | |||

| == Format == | |||

| The format of the Contest has changed over the years, though the basic tenets have always been thus: participant countries submit songs, which are performed live in a television programme transmitted across the Eurovision Network by the EBU simultaneously to all countries. A "country" as a participant is represented by one television broadcaster from that country: typically, but not always, that country's national ]. The programme is hosted by one of the participant countries, and the transmission is sent from the ] in the host city. During this programme, after all the songs have been performed, the countries then proceed to cast votes for the other countries' songs: nations are not allowed to vote for their own song. At the end of the programme, the winner is declared as the song with the most points. The winner receives, simply, the prestige of having won—although it is usual for a ] to be awarded to the winning songwriters, and the winning country is invited to host the event the following year.<ref name="milestones"/> | |||

| There have been 68 contests {{as of|2024|lc=y|post=,}} making Eurovision the longest-running annual international televised music competition as determined by '']''.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Lynch |first=Kevin |date=23 May 2015 |title=Eurovision recognised by Guinness World Records as the longest-running annual TV music competition (international) |url=https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/news/2015/5/eurovision-recognised-by-guinness-world-records-as-the-longest-running-annual-tv-379520 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200122030337/https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/news/2015/5/eurovision-recognised-by-guinness-world-records-as-the-longest-running-annual-tv-379520 |archive-date=22 January 2020 |access-date=26 June 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Escudero |first=Victor M. |date=23 May 2015 |title=Eurovision Song Contest awarded Guinness world record |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/eurovision-song-contest-awarded-guinness-world-record |access-date=9 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> The contest has been listed as one of the longest-running television programmes in the world and among the world's most watched non-sporting events.<ref>{{Cite web |date=26 June 2015 |title=Culture & Entertainment {{!}} Eurovision |url=http://www.brandeu.eu/eu-powerhouse/culture-and-entertainment/eurovision/ |access-date=19 March 2021 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=3 June 2015 |title=Press Release: 60th Eurovision Song Contest Seen by Nearly 200 Million Viewers |url=https://www.ebu.ch/news/2015/06/press-release-60th-eurovision-so |access-date=19 March 2021 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Ritman |first=Alex |date=3 June 2015 |title=Eurovision Song Contest Draws Almost 200 Million Viewers |url=https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/6583366/eurovision-song-contest-draws-almost-200-million-viewers |magazine=] |access-date=20 March 2021}}</ref> A total of ] have taken part in at least one edition, with a record 43 countries participating in a single contest, first in {{Escyr|2008}} and subsequently in {{Escyr|2011}} and {{Escyr|2018}}.<ref name="Facts & Figures" /><ref name="ESC History" /> Australia became the first non-EBU member country to compete following an invitation by the EBU ahead of the contest's {{Escyr|2015||60th edition}} in 2015;<ref name="Australia">{{Cite web |date=10 February 2015 |title=Australia to compete in the 2015 Eurovision Song Contest |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/australia-to-compete-in-the-2015-eurovision-song-contest |access-date=27 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last1=Kemp |first1=Stuart |last2=Plunkett |first2=John |date=10 February 2015 |title=Eurovision Song Contest invites Australia to join 'world's biggest party' |url=https://www.theguardian.com/media/2015/feb/10/eurovision-song-contest-invites-australia-to-join-worlds-biggest-party |access-date=27 June 2020 |website=]}}</ref> initially announced as a "one-off" for the anniversary edition, the country was invited back the following year and has subsequently participated every year since.<ref>{{Cite web |date=17 November 2015 |title=Australia to return to the Eurovision Song Contest! |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/australia-to-return-to-the-eurovision-song-contest |access-date=27 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref name="Australia 2023">{{Cite web |date=12 February 2019 |title=Australia secures spot in Eurovision for the next five years |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/australia-secures-spot-in-eurovision-until-2023 |access-date=27 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref name="Participants">{{cite web |date=5 December 2023 |title=Eurovision 2024: 37 broadcasters head to Malmö |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/eurovision-2024-37-broadcasters-head-malmo |access-date=5 December 2023 |website= |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> | |||

| The programme is invariably opened by one or more ]s, welcoming viewers to the show. Most host countries choose to capitalise on the opportunity afforded them by hosting a programme with such a wide-ranging international audience, and it is common to see the presentation interspersed with video footage of scenes from the host nation, as if advertising for ]. Between the songs and the announcement of the voting an interval act is performed, which can be any form of entertainment imaginable. Interval entertainment has included such acts as ] ({{escyr|1974}})<ref name="Brighton">{{cite web |publisher= eurovision.tv |url= http://web.archive.org/web/20051024015015/http://www.eurovision.tv/english/history_1974_brighton.htm |title= 1974: Brighton, United Kingdom |accessdate=2005-10-24}}</ref> and the first international presentation of ] ({{escyr|1994}}).<ref>{{cite web |author=Clive Barnes |url= http://www.riverdance.com/htm/theshow/thejourney |title= Riverdance Ten Years on |publisher = RiverDance.com | accessdate=2006-07-27}}</ref> | |||

| Eurovision had been held every year until 2020, when {{Escyr|2020||that year's contest}} was cancelled in response to the ].<ref name="Facts & Figures" /><ref name="2020 cancellation">{{Cite web |date=6 April 2020 |title=Official EBU statement & FAQ on Eurovision 2020 cancellation |url=https://eurovision.tv/official-ebu-statement-and-faq-eurovision-song-contest-2020-cancellation |access-date=27 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> No competitive event was able to take place due to uncertainty caused by the ] and the various restrictions imposed by the governments of the participating countries. In its place a special broadcast, '']'', was produced by the organisers, which honoured the songs and artists that would have competed in 2020 in a non-competitive format.<ref name="2020 cancellation" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=9 April 2020 |title=Eurovision: Europe Shine A Light |url=https://eurovision.tv/eurovision-europe-shine-a-light |access-date=27 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=17 May 2020 |title=Eurovision still shines despite cancelled final |work=] |agency=] |url=https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2020/may/17/eurovision-still-shines-despite-cancelled-final |access-date=27 June 2020}}</ref> | |||

| The theme music played before and after the broadcasts of the Eurovision Song Contest (and other Eurovision broadcasts) is the prelude to ]'s ].<ref name="GoldenJubilee"/> | |||

| === Naming === | |||

| The Eurovision Song Contest final is traditionally held on a spring Saturday evening, at 19:00 ] (20:00 ], or 21:00 ]). Usually one Saturday in May is chosen, although the Contest has been held on a Thursday (in 1956) and as early as March. Since 2004, due to the increasing number of eligible countries which have wished to participate, qualifying rounds—known as Semi Finals—have been held 2–4 days before the final. | |||

| Over the years the name used to describe the contest, and used on the official logo for each edition, has evolved. The first contests were produced under the name of {{lang|fr|Grand Prix Eurovision de la Chanson Européenne}} in French and as the ''Eurovision Song Contest Grand Prix'' in English, with similar variations used in the languages of each of the broadcasting countries. From 1968, the English name dropped the 'Grand Prix' from the name, with the French name being aligned as the {{lang|fr|Concours Eurovision de la Chanson}}, first used in 1973.<ref name="ESC History" /><ref>{{Cite web |year=2002 |title=Palmarès du Concours Eurovision de la Chanson |url=http://www.ebu.ch/departments/television/pdf/Winners-Palmares_56-02.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080528174029/http://www.ebu.ch/departments/television/pdf/Winners-Palmares_56-02.pdf |archive-date=28 May 2008 |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Concours Eurovision de la Chanson 2019 |url=https://www.france.tv/france-4/concours-eurovision-de-la-chanson-2019/ |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref> The contest's official brand guidance specifies that translations of the name may be used depending on national tradition and brand recognition in the competing countries, but that the official name ''Eurovision Song Contest'' is always preferred; the contest is commonly referred to in English by the abbreviation "Eurovision", and in internal documents by the acronym "ESC".<ref name="Brand" /> | |||

| On only four occasions has the name used for the official logo of the contest not been in English or French: the Italian names {{lang|it|Gran Premio Eurovisione della Canzone}} and {{lang|it|Concorso Eurovisione della Canzone}} were used when Italy hosted the {{Escyr|1965}} and {{Escyr|1991}} contests respectively; and the ] name {{lang|nl|Eurovisiesongfestival}} was used when the Netherlands hosted in {{Escyr|1976}} and {{Escyr|1980}}.<ref name="ESC History" /> | |||

| == Participation == | |||

| {{further|]}} | |||

| Eligible participants include Active Members (as opposed to Associate Members) of the European Broadcasting Union. Active members are those whose states fall within the ], or otherwise those who are members of the ].<ref name="EBUmembership">{{cite web |publisher= European Broadcasting Union |date= 22 February 2006|url= http://www.ebu.ch/departments/legal/activities/leg_membership.php |title= Membership conditions|accessdate=2006-07-18}}</ref> | |||

| == Format == | |||

| The European Broadcasting Area is defined by the ]:<ref>{{cite web |publisher= International Telecommunication Union |year= 1994 |url= http://www.ebu.ch/CMSimages/en/leg_ref_itu_radio_regulations_tcm6-4307.pdf |title= Extracts From The Radio Regulations |accessdate= 2006-07-18 |format= PDF}}</ref> | |||

| Original songs representing participating countries are performed in a live television programme broadcast via the ] simultaneously to all countries. A "country" as a participant is represented by one television broadcaster from that country, a member of the European Broadcasting Union, and is typically that country's national ] organisation.<ref name="How it works">{{Cite web |date=15 January 2017 |title=How it works – Eurovision Song Contest |url=https://eurovision.tv/about/how-it-works |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> The programme is staged by one of the participant countries and is broadcast from an ] in the selected host city.<ref>{{Cite web |last=LaFleur |first=Louise |date=30 August 2019 |title=Rotterdam to host Eurovision 2020! |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/rotterdam-to-host-eurovision-2020 |access-date=9 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Since 2008, each contest is typically formed of three live television shows held over one week: two semi-finals are held on the Tuesday and Thursday, followed by a final on the Saturday. All participating countries compete in one of the two semi-finals, except for the host country of that year's contest and the contest's biggest financial contributors known as the "Big Five"—{{Esccnty|France}}, {{Esccnty|Germany}}, {{Esccnty|Italy}}, {{Esccnty|Spain}} and the {{Esccnty|United Kingdom}}.<ref name="How it works" /><ref name="BBC lessons learned" /> The remaining countries are split between the two semi-finals, and the 10 highest-scoring entries in each qualify to produce 26 countries competing in the final.<ref name="How it works" /> Since the introduction of the semi-final round in 2004, {{Esccnty|Luxembourg}} and {{Esccnty|Ukraine}} are the only countries outside of the "Big Five" to have qualified for the final of every contest they have competed in. | |||

| Each participating broadcaster has sole discretion over the process it may employ to select its entry for the contest. Typical methods in which participants are selected include a televised national final using a jury and/or public vote; an internal selection by a committee appointed by the broadcaster; and a mixed format where some decisions are made internally and the public are engaged in others.<ref name="National selections">{{Cite web |date=21 March 2017 |title=Eurovision Song Contest: National Selections |url=https://eurovision.tv/about/in-depth/national-selections/ |access-date=7 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Among the most successful televised selection shows is Sweden's {{Lang|sv|]|italic=no}}, first established in 1959 and now one of Sweden's most watched television shows each year.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Rosney |first=Daniel |date=7 March 2020 |title=Sweden's Melfest: Why a national Eurovision show won global fans |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-51749312 |access-date=7 July 2020 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| :''The "European Broadcasting Area" is bounded on the west by the western boundary of Region 1, on the east by the meridian 40° East of Greenwich and on the south by the parallel 30° North so as to include the western part of the USSR, the northern part of Saudi Arabia and that part of those countries bordering the Mediterranean within these limits. In addition, Iraq, Jordan and that part of the territory of Turkey lying outside the above limits are included in the European Broadcasting Area.'' | |||

| ], Germany]] | |||

| The western boundary of ] is a line drawn west of Iceland down the centre of the ].<ref>{{cite web |publisher= International Telecommunication Union |date= 8 September 2005|url= http://life.itu.int/radioclub/rr/art05.htm#Reg |title= Radio Regulations |accessdate= 2006-07-18}}</ref> | |||

| Each show typically begins with an opening act consisting of music and/or dance performances by invited artists, which contributes to a unique theme and identity created for that year's event; since 2013, the opening of the contest's final has included a "Flag Parade", with competing artists entering the stage behind their country's flag in a similar manner to the ] at the ].<ref name="Grand Final story">{{Cite web |date=16 May 2020 |title=Looking back: the Grand Final |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/grand-final-story |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210401132202/https://eurovision.tv/story/grand-final-story |archive-date=1 April 2021 |access-date=1 April 2021 |publisher=European Broadcasting Union}}</ref><ref name="Iconic intervals">{{Cite web |date=16 August 2019 |title=The Most Iconic Opening & Interval Acts of the Eurovision Song Contest |url=https://eurovision.tv/video/the-most-iconic-opening-interval-acts-of-the-eurovision-song-contest |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Viewers are welcomed by ] who provide key updates during the show, conduct interviews with competing acts from the ], and guide the voting procedure in English and French.<ref>{{Cite web |date=31 March 2017 |title=Presenters – Eurovision Song Contest |url=https://eurovision.tv/presenters |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Jordan |first=Paul |date=1 March 2017 |title=Behind the scenes with the hosts of the 2017 Eurovision Song Contest |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/behind-the-scenes-with-the-hosts |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200928064139/https://eurovision.tv/story/behind-the-scenes-with-the-hosts |archive-date=28 September 2020 |access-date=1 April 2021 |publisher=European Broadcasting Union}}</ref><ref name="Rules" /> Competing acts perform sequentially, and after all songs have been performed, viewers are invited to vote for their favourite performances—except for the performance of their own country—via ], SMS and the official Eurovision app.<ref name="How it works" /> The public vote comprises 50% of the final result alongside the views of a jury of music industry professionals from each country.<ref name="How it works" /><ref name="Rules" /> An ] is invariably featured during this voting period, which on several occasions has included a well-known personality from the host country or an internationally recognised figure.<ref name="Grand Final story" /><ref name="Iconic intervals" /> The results of the voting are subsequently announced; in the semi-finals, the 10 highest-ranked countries are announced in a random order, with the full results undisclosed until after the final. In the final, the presenters call upon a representative spokesperson for each country in turn who announces their jury's points, while the results of the public vote are subsequently announced by the presenters.<ref name="How it works" /><ref name="Voting" /> In recent years, it has been tradition that the first country to announce its jury points is the previous host, whereas the last country is the current host (with the exception of {{Escyr|2023}}, when the United Kingdom hosted the contest on behalf of Ukraine, which went first).<ref>{{Cite web |last=Tarbuck |first=Sean |date=12 May 2023 |title=Jury voting order revealed for Eurovision 2023 |url=https://www.escunited.com/jury-voting-order-revealed-for-eurovision-2023/ |access-date=12 May 2023 |website=ESCUnited |language=en-US}}</ref> The qualifying acts in the semi-finals, and the winning delegation in the final are invited back on stage; in the final, a ] is awarded to the winning performers and songwriters by the previous year's winner, followed by a reprise of the winning song.<ref name="How it works" /><ref name="Trophy">{{Cite web |date=14 January 2017 |title=Eurovision Song Contest: Trophy |url=https://eurovision.tv/about/trophy/ |access-date=30 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> The full results of the competition, including detailed results of the jury and public vote, are released online shortly after the final, and the participating broadcaster of the winning entry is traditionally given the honour of organising the following year's event.<ref name="How it works" /><ref name="Voting" /> | |||

| == Participation == | |||

| Active members include broadcasting organisations whose transmissions are made available to (virtually) all of the ] of the country in which they are based.<ref name="EBUmembership"/> | |||

| {{Further|List of countries in the Eurovision Song Contest}} | |||

| ] | |||

| If an EBU Active Member wishes to participate, they must fulfil conditions as laid down by the rules of the Contest (of which a separate copy is drafted annually). As of {{CURRENTYEAR}}, this includes the necessity to have broadcast the previous year's programme within their country, and paid the EBU a participation fee in advance of the ] specified in the rules of the Contest for the year in which they wish to participate. | |||

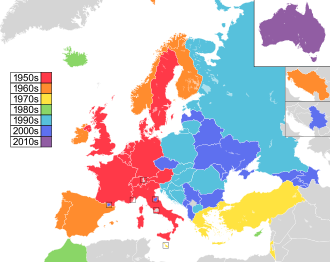

| ]}}]] | |||

| ]Active members (as opposed to associate members) of the European Broadcasting Union are eligible to participate; active members are those who are located in states that fall within the ], or are ].<ref name="EBUmembership">{{Cite web |date=27 April 2018 |title=EBU – Admission |url=https://www.ebu.ch/about/members/admission |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190913022313/https://www.ebu.ch/about/members/admission |archive-date=13 September 2019 |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref> Active members include media organisations whose broadcasts are often made available to at least 98% of households in their own country which are equipped to receive such transmissions.<ref>{{Cite web |date=June 2013 |title=Regulation on Detailed Membership Criteria under Article 3.6 of the EBU Statutes |url=https://www.ebu.ch/files/live/sites/ebu/files/About/Governance/Regulation%202013_EN.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190516221310/https://www.ebu.ch/files/live/sites/ebu/files/About/Governance/Regulation%202013_EN.pdf |archive-date=16 May 2019 |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref> Associate member broadcasters may be eligible to compete, dependent on approval by the contest's reference group.<ref name="Who can take part">{{Cite web |title=Which countries can take part? |url=https://eurovision.tv/page/about/which-countries-can-take-part#Which%20countries? |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170317083448/https://eurovision.tv/page/about/which-countries-can-take-part#Which%20countries? |archive-date=17 March 2017 |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> | |||

| The European Broadcasting Area is defined by the ] as encompassing the geographical area between the boundary of ] in the west, the ] of ] in the east, and ] in the south. Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and the parts of Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Turkey and Ukraine lying outside these limits are also included in the European Broadcasting Area.<ref name="ITU-R Radio Regulation 2012">{{Cite web |year=2012 |title=ITU-R Radio Regulations 2012–15 |url=http://www.sma.gov.jm/sites/default/files/publication_files/ITU-R_Radio_Regulations_2012_%202015_%20Article_5_Table%20of%20Frequencies.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130816092114/http://sma.gov.jm/sites/default/files/publication_files/ITU-R_Radio_Regulations_2012_%202015_%20Article_5_Table%20of%20Frequencies.pdf |archive-date=16 August 2013 |access-date=28 June 2019 |publisher=], available from the Spectrum Management Authority of Jamaica}}</ref><ref name="ITU-R Radio Regulation 2004">{{Cite web |year=2004 |title=ITU-R Radio Regulations – Articles edition of 2004 (valid in 2004–07) |url=http://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-s/oth/02/02/S020200001A4501PDFE.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171010235726/https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-s/oth/02/02/S020200001A4501PDFE.pdf |archive-date=10 October 2017 |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| Eligibility to participate is not determined by ] inclusion within the continent of ], despite the "Euro" in "Eurovision" — nor does it have a direct connection with the ]. Several countries geographically outside the boundaries of Europe have competed: ], ] and ], in ], since ], ] and ] respectively; and ], in ], in the ] alone. In addition, several ] with only part of their territory in Europe have competed: ], since ]; ], since ]; ], since ]; and ], since ]. Two of the countries that have also previously sought to enter the competition, ] and ], in Western Asia and North Africa respectively, are also outside of Europe. The ] state of ], in Western Asia, announced in 2009 its interest in joining the Contest in time for the 2011 edition.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.esctoday.com/news/read/14007|title=Gulf nation wants to join Eurovision|last=Repo|first=Juha|date=2009-05-12|publisher=''ESCToday''|accessdate=2009-05-12}}</ref> | |||

| Eligibility to participate in the contest is therefore not limited to countries in Europe, as several states geographically outside the boundaries of the continent or which span ] are included in the Broadcasting Area.<ref name="Who can take part" /> Countries from these groups have taken part in past editions, including countries in Western Asia such as Israel and ], countries which span Europe and Asia like Russia and Turkey, and North African countries such as ].<ref name="ESC History" /> Australia became the first country to participate from outside the European Broadcasting Area in 2015, following an invitation by the contest's reference group.<ref name="Australia" /> | |||

| In addition, ], ], ] and the ] control territories under their ] outside of Europe. The ], of which ] is the hegemonial part, includes ] in ]. | |||

| EBU members who wish to participate must fulfil conditions as laid down in the rules of the contest, a separate copy of which is drafted annually. A maximum of 44 countries can take part in any one contest.<ref name="Rules">{{Cite web |date=12 January 2017 |title=Eurovision Song Contest: Rules |url=https://eurovision.tv/about/rules/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220826013327/https://eurovision.tv/about/rules |archive-date=26 August 2022 |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref> Broadcasters must have paid the EBU a participation fee in advance of the deadline specified in the rules for the year in which they wish to participate; this fee is different for each country based on its size and viewership.<ref name="FAQ">{{Cite web |date=12 January 2017 |title=FAQ – Eurovision Song Contest |url=https://eurovision.tv/about/faq/ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200623153206/https://eurovision.tv/about/faq/ |archive-date=23 June 2020 |access-date=28 June 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> | |||

| Fifty-one countries have participated at least once. These are listed here alongside the year in which they made their debut: | |||

| Fifty-two countries have participated at least once.<ref name="ESC History" /> These are listed here alongside the year in which they made their debut: | |||

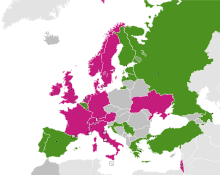

| [[Image:EurovisionParticipants.png|thumb|300px|right|Participation since 1956: {{legend|#22b14c|Entered at least once}} {{legend|#ffc20e|Never entered, although eligible to do so}} {{legend|#ff00ff|Entry intended, but later withdrew}} | |||

| ]] | |||

| {| | |||

| |- style="vertical-align:top" | |||

| | | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="font-size:94%" | {| class="wikitable" style="font-size:94%" | ||

| ! scope="col" width=10% | Year | |||

| ! Country making its debut entry | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope=" |

! scope="col"| Year | ||

| ! scope="col"| Country making its debut entry | |||

| | {{Esc|Belgium}}, {{Esc|France}}, {{Esc|Germany}}<sup>a</sup>, {{Esc|Italy}},<br />{{Esc|Luxembourg}}, {{Esc|Netherlands}}, {{Esc|Switzerland}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="7"| {{ESCYr|1956}} | ||

| | {{esc|Belgium}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Austria}}, {{Esc|Denmark}}, {{Esc|United Kingdom}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|France}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1958}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Sweden}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|Germany}}{{efn|group=Participation|Represented ] until 1990; ] never competed. Presented on all occasions as 'Germany', except in 1967 as 'Federal Republic of Germany', in 1970 and 1976 as 'West Germany', and in 1990 as 'F.R. Germany'.}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1959}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Monaco}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|Italy}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1960}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Norway}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|Luxembourg}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1961}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Finland}}, {{Esc|Spain}}, {{Esc|Yugoslavia}}<sup>b</sup> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|Netherlands}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1964}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Portugal}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|Switzerland}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1965}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Ireland}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="3"| {{ESCYr|1957}} | ||

| | {{ |

| {{esc|Austria}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|Denmark}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1973}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Israel}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|United Kingdom}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1974}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Greece}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1958}} | ||

| | {{ |

| {{esc|Sweden}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1959}} | ||

| | {{ |

| {{esc|Monaco}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1960}} | ||

| | {{ |

| {{esc|Norway}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="3"| {{ESCYr|1961}} | ||

| | {{ |

| {{esc|Finland}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|Spain}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1993}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Bosnia and Herzegovina}}, {{Esc|Croatia}}, {{Esc|Slovenia}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | {{esc|Yugoslavia}}{{efn|group=Participation|Represented the ] until 1991, and the ] in 1992.}} | |||

| ! scope="row" valign="top" | {{escyr|1994}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Estonia}}, {{Esc|Hungary}}, {{Esc|Lithuania}}, {{Esc|Poland}},<br /> {{Esc|Romania}}, {{Esc|Russia}}, {{Esc|Slovakia}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1964}} | ||

| | {{ |

| {{esc|Portugal}} | ||

| <!--RE F.Y.R. MACEDONIA: THIS IS THE OFFICIAL WAY THAT THE COUNTRY'S NAME IS WRITTEN BY THE EBU. PLEASE DO NOT CHANGE IT, EITHER TO "REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA" OR TO "FYROM". WE RECOGNISE THAT THERE IS AN ONGOING NAMING DISPUTE BETWEEN MACEDONIANS AND GREEKS, BUT REALLY PEOPLE - PLEASE GROW UP. JUST LEAVE IT AS WRITTEN IN THE ACTUAL CONTEST BY THE EBU. IF YOU WANT THAT TO CHANGE THEN PETITION THE EBU ABOUT IT. DON'T KEEP EDIT WARRING HERE, OR YOU WILL BE BLOCKED FROM EDITING.----Great point, I'm from Macedonia, and I was about to change it, but really - growing up is a good idea, especially the Greek guys who did this - http://en.wikipedia.org/search/?title=Eurovision_Song_Contest&oldid=290475739 --> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1965}} | ||

| | {{ |

| {{esc|Ireland}} | ||

| |} | |||

| | | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="font-size:94%" | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope=" |

! scope="col"| Year | ||

| ! scope="col"| Country making its debut entry | |||

| | {{Esc|Ukraine}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1971}} | ||

| | {{esc|Malta}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Albania}}, {{Esc|Andorra}}, {{Esc|Belarus}}, {{Esc|Serbia and Montenegro}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1973}} | ||

| | {{esc|Israel}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Bulgaria}}, {{Esc|Moldova}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1974}} | ||

| | {{ |

| {{esc|Greece}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1975}} | ||

| | {{esc|Turkey}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Czech Republic}}, {{Esc|Georgia}}, {{Esc|Montenegro}}, {{Esc|Serbia}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="row" |

! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1980}} | ||

| | {{esc|Morocco}} | |||

| | {{Esc|Azerbaijan}}, {{Esc|San Marino}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1981}} | |||

| | {{esc|Cyprus}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1986}} | |||

| | {{esc|Iceland}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="3"| {{ESCYr|1993}} | |||

| | {{esc|Bosnia and Herzegovina}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Croatia}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Slovenia}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="7"| {{ESCYr|1994}} | |||

| | {{esc|Estonia}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Hungary}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Lithuania}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Poland}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Romania}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Russia}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Slovakia}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|1998}} | |||

| | {{esc|North Macedonia}}{{efn|group=Participation|Presented as the ']' before 2019.}} | |||

| |} | |||

| | | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="font-size:94%" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="col"| Year | |||

| ! scope="col"| Country making its debut entry | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|2000}} | |||

| | {{esc|Latvia}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|2003}} | |||

| | {{esc|Ukraine}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="4"| {{ESCYr|2004}} | |||

| | {{esc|Albania}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Andorra}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Belarus}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Serbia and Montenegro}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="2"| {{ESCYr|2005}} | |||

| | {{esc|Bulgaria}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Moldova}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|2006}} | |||

| | {{esc|Armenia}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="4"| {{ESCYr|2007}} | |||

| | {{esc|Czech Republic}}{{efn|group=Participation|Presented as ']' from 2023.}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Georgia}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Montenegro}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|Serbia}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="2"| {{ESCYr|2008}} | |||

| | {{esc|Azerbaijan}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{esc|San Marino}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" style="vertical-align:top center;" rowspan="1"| {{ESCYr|2015}} | |||

| | {{esc|Australia}}{{efn|group=Participation|Associate member broadcaster; initially announced as a one-off participant to commemorate the contest's 60th anniversary, has subsequently participated every year since.<ref name="Australia 2023" /><ref name="Participants" />}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| {{notelist|group=Participation}} | |||

| :<small>a) Before ] in ] occasionally presented as ], representing the ]. ], officially the German Democratic Republic, did not compete.</small> | |||

| :<small>b) The entries presented as being from "]" represented the ], except for the 1992 entry, which represented the ] (consisting of a small portion of the ''previous'' Yugoslavia).</small> | |||

| == |

== Hosting == | ||

| {{Further|List of Eurovision Song Contest host cities}} | |||

| Each country must submit one song to represent them in any given year they participate. The only exception to this was when each country submitted two songs in the inaugural Contest. There is a rule which forbids any song being entered which has been previously commercially released or broadcast in public before a certain date relative to the Contest in question.<ref name="2005rules">{{cite web|publisher=eurovision.tv|year=2005|url=http://web.archive.org/web/20060210010517/http://www.eurovision.tv/searchfiles_english/574.htm|title=Rules of the 2005 Eurovision Song Contest|accessdate=2006-02-10}}</ref> The purpose of this rule is to ensure that only new songs are entered into the Contest, and not existing successful songs of years gone by, which might give a country an unfair advantage due to the fact that the song is already known and popular. | |||

| ] | |||

| The winning country traditionally hosts the following year's event, with ] since {{Escyr|1958}}.<ref name="Historical Milestones">{{Cite web |title=Historical Milestones |url=http://www.eurovision.tv/english/611.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060526065558/http://www.eurovision.tv/english/611.htm |archive-date=26 May 2006 |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref name="ESC History" /> Hosting the contest can be seen as a unique opportunity for promoting the host country as a tourist destination and can provide benefits to the local economy and tourism sectors of the host city.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Boyle |first=Stephen |date=13 May 2016 |title=The cost of winning the Eurovision Song Contest |url=https://www.rbs.com/rbs/news/2016/05/the-cost-of-winning-the-eurovision-song-contest.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220821193101/https://www.rbs.com/rbs/news/2016/05/the-cost-of-winning-the-eurovision-song-contest.html |archive-date=21 August 2022 |access-date=20 March 2021 |publisher=]}}</ref> However, there is a perception reflected in popular culture that some countries wish to avoid the costly burden of hosting{{spnd}}sometimes resulting in them sending deliberately subpar entries with no chance of winning. This belief is mentioned in '']'' (2020) and a plot point in the '']'' episode "]" (1996).<ref>{{Cite web |last=O'Sullivan |first=Domhnall |date=2024-07-19 |title=Swiss direct democracy is Eurovision's latest challenge |url=https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/democracy/swiss-direct-democracy-is-eurovisions-latest-challenge/84198908 |access-date=2024-08-18 |website=] |language=en-GB}}</ref> Preparations for each year's contest typically begin at the conclusion of the previous year's contest, with the winning country's head of delegation receiving a welcome package of information related to hosting the contest at the winner's press conference.<ref name="How it works" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=14 May 2017 |title=Winner's Press Conference with Portugal's Salvador Sobral |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/2017-winners-press-conference |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=19 May 2019 |title=Winner's Press Conference with the Netherlands' Duncan Laurence |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/winners-press-conference-with-netherlands-duncan-laurence |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Eurovision is a non-profit event, and financing is typically achieved through a fee from each participating broadcaster, contributions from the host broadcaster and the host city, and commercial revenues from sponsorships, ticket sales, televoting and merchandise.<ref name="FAQ" /> | |||

| The host broadcaster will subsequently select a host city, typically a national or regional capital city, which must meet certain criteria set out in the contest's rules. The host venue must be able to accommodate at least 10,000 spectators, a press centre for 1,500 journalists, should be within easy reach of an ] and with hotel accommodation available for at least 2,000 delegates, journalists and spectators.<ref name="Host city criteria">{{Cite web |date=30 July 2007 |title=What does it take to become a Eurovision host city? |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/what-does-it-take-to-become-a-eurovision-host-city |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> A variety of different venues have been used for past editions, from small theatres and television studios to large arenas and stadiums.<ref name="ESC History" /> The largest host venue is ] in Copenhagen, which was attended by almost 38,000 spectators in {{Escyr|2001}}.<ref name="Facts & Figures" /><ref name="Copenhagen 01" /> With a population of 1,500 at the time of the {{Escyr|1993||1993 contest}}, ], Ireland remains the smallest hosting settlement, although its ] is capable of hosting up to 8,000 spectators.<ref name="Millstreet 93" /><ref>{{Cite web |title=Millstreet Town: Green Glens Arena |url=http://www.millstreet.ie/green%20glens/greenglens.htm |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190401191842/http://www.millstreet.ie/green%20glens/greenglens.htm |archive-date=1 April 2019 |access-date=3 July 2020 |website=millstreet.ie}}</ref> | |||

| Countries may select their songs by any means they wish: whether it be an internal decision made by the participating broadcaster, or a public contest which allows the country's public to ] between several songs. The EBU encourages broadcasters to use the public competition format, as this generates more ] for the Contest. These public selections are known as ''national finals''. | |||

| Unlike the ] or ], whose host venues are announced several years in advance, there is usually no purpose-built infrastructure whose construction is justified with the needs of hosting the Eurovision Song Contest. However, the {{Escyr|2012|3=2012 edition}}, hosted in ], Azerbaijan, was held at ], a venue that had not existed when Azerbaijan won the previous year.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2014-08-13 |title=From Eurovision to the European Games - the Baku Crystal Hall |url=https://www.insidethegames.biz/articles/1021853/from-eurovision-to-the-european-games-the-baku-crystal-hall |access-date=2024-05-12 |website=insidethegames.biz}}</ref> Most other editions have been held in pre-existing venues, but renovations or modifications have sometimes been undertaken in the year prior to the contest which are justified with the needs of Eurovision.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Ghazi |first=Saarah |date=2024-05-08 |title=Eurovision: Does the winner take it all? |url=https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/resource/eurovision-does-the-winner-take-it-all/ |access-date=2024-08-18 |website=Oxford Economics |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| Some countries' national finals are as big as—if not bigger than—the international Eurovision Song Contest itself, involving many songs being submitted to national ''semi''-finals. The Swedish national final, '']'' (literally, "The Melody Festival") includes 32 songs being performed over four semi-finals, played to huge audiences in arenas around the country, before the final show in ]. This has become the highest-rated programme of the year in Sweden by TV audience figures.<ref>{{cite web |author= Stella Floras |date=3 January 2007|url= http://www.esctoday.com/news/read/7135 |title= Top TV ratings for Melodifestivalen | publisher = esctoday.com | accessdate= 2007-05-08}}</ref> In Spain, the ] '']'' was inaugurated in 2002; the winners of the first three seasons proceeded to represent the country at Eurovision.<ref>{{cite web |publisher= Terra Networks España |url= http://www.portalmix.com/operaciontriunfo1/eurovision |title= Operación Triunfo: Un intenso camino hacia el festival de eurovision |accessdate= 2006-07-22}} {{es icon}} </ref> | |||

| === Eurovision logo and theme === | |||

| Whichever method is used to select the entry, the song's details must be finalised and submitted to the EBU by a deadline some weeks before the international Contest. | |||

| ] | |||

| Until 2004, each edition of the contest used its own logo and visual identity as determined by the respective host broadcaster. To create a consistent visual identity, a generic logo was introduced ahead of the {{Escyr|2004||2004 contest}}. This is typically accompanied by a unique theme artwork designed for each individual contest by the host broadcaster, with the flag of the host country placed prominently in the centre of the Eurovision heart.<ref name="Brand">{{Cite web |title=Eurovision Song Contest: Brand |date=12 January 2017 |url=https://eurovision.tv/about/brand |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210201075740/https://eurovision.tv/about/brand |archive-date=1 February 2021 |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> The original logo was designed by the London-based agency JM International, and received a revamp in 2014 by the Amsterdam-based Cityzen Agency for the contest's {{Escyr|2015||60th edition}}.<ref>{{Cite web |date=31 July 2014 |title=Eurovision Song Contest logo evolves |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/eurovision-song-contest-logo-evolves |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref name="Logos & Artwork">{{Cite web |date=12 January 2017 |title=Eurovision Song Contest: Logos and Artwork |url=https://eurovision.tv/mediacentre/logos-and-artwork |access-date=17 March 2021 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> | |||

| == Hosting == | |||

| {{seealso|List of host cities of the Eurovision Song Contest}} | |||

| Most of the expense of the Contest is covered by event ] and contributions from the other participating nations. <!-- Comment out unreferenced statement. If someone can find a reference, please include it: The 2004 Contest was allocated a budget of some €15 million and was the most expensive edition to date.{{Fact|date=October 2008}}--> The Contest is considered a unique showcase for promoting the host country as a tourist destination. In the Summer of 2005, Ukraine abolished its normal visa requirements for tourists to coincide with its hosting of the Contest.<ref>{{cite web |author= Helen Fawkes | publisher = BBC News |date= 19 May 2005|url= http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/music/4561275.stm |title= Ukrainian hosts' high hopes for Eurovision |accessdate= 2006-07-15}}</ref> | |||

| An individual theme is utilised by contest producers when constructing the visual identity of each edition of the contest, including the stage design, the opening and interval acts, and the "postcards".<ref>{{Cite web |last=Groot |first=Evert |date=28 October 2018 |title=Tel Aviv 2019: Dare to Dream |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/slogan-tel-aviv-2019-dare-to-dream |access-date=7 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=LaFleur |first=Louise |date=25 October 2019 |title=The making of 'Open Up' |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/the-making-of-open-up |access-date=7 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=9 December 2019 |title=2020 postcard concept revealed as Dutch people can join in on the fun |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/eurovision-2020-postcards-concept-revealed |access-date=7 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Gleave |first=Amy |date=2023-05-02 |title=Eurovision branding over the years |url=https://www.dawncreative.co.uk/insight/eurovision-branding/ |access-date=2023-09-02 |website=Dawn Creative |language=en}}</ref> The short video postcards are interspersed between the entries and were first introduced in 1970, initially as an attempt to "bulk up" the contest after a number of countries decided not to compete, but has since become a regular part of the show and usually highlight the host country and introduce the competing acts.<ref name="Amsterdam 50th anniv">{{Cite web |date=29 April 2020 |title=Happy 50th Anniversary, Eurovision 1970! |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/happy-50th-anniversary-1970-eurovision |access-date=7 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref>{{sfn|O'Connor|2010|pp=40–43}} A ] for each edition, first introduced in {{escyr|2002}}, was also an integral part of each contest's visual identity, which was replaced by a permanent slogan from {{escyr|2024}} onwards. The permanent slogan, "United by Music", had previously served as the slogan for the {{escyr|2023||2023 contest}} before being retained for all future editions as part of the contest's global brand strategy.<ref name="Slogan2">{{Cite web |date=2023-11-14 |title='United By Music' chosen as permanent Eurovision slogan |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/united-by-music-permanent-slogan |access-date=2023-11-14 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest|lang=en-gb}}</ref> | |||

| ], Stockholm: host of Eurovision 2000.]] | |||

| Preparations to host the Contest start a matter of weeks after a country wins, and confirm to the EBU that they intend to—and have the capacity to—host the event. A host city is chosen (usually the capital, but not always), and a suitable concert venue. The largest concert venue was a football stadium in ], '']'', which held an audience of approximately 38,000 people when ] hosted the Contest in 2001.<ref name="milestones"/> The smallest town in which the Contest has ever been held was ] in ], ], which hosted the show in 1993. The village had a population of 1,500<ref>{{cite web |publisher= cork-guide.ie |date= 19 May 2006 |url= http://www.cork-guide.ie/millstreet/town.html |title= Millstreet |accessdate= 2006-07-18}}</ref>—although the '']'' venue held considerably more audience members.<ref>{{cite web |publisher= doteurovision.com |url= http://www.doteurovision.com/1993/green.htm |title= Eurovision 1993 - The Venue |accessdate= 2006-07-18}}</ref> | |||

| === Preparations === | |||

| It is always a consideration, when choosing a host city and venue, what hotel and press facilities there are in the vicinity.<ref>{{cite web |publisher= esctoday.com |date= 31 May 2006|url= http://www.esctoday.com/news/read/6245 |title= Where do we go next year?|accessdate= 2006-07-19}}</ref> In ] 2005, hotel rooms were scarce as the Contest organisers asked the ] to put a block on bookings they did not control themselves through official delegation allocations or tour packages: this led to many people's hotel bookings being cancelled.<ref>{{cite web |author= John Marone | publisher = The Ukrainian Observer |url= http://www.ukraine-observer.com/articles/208/655 |title= Where Do We Put The Foreign Tourists?|accessdate= 2006-07-18}}</ref> The impact that the Contest has on the host city is inversely proportional to its size: in ] 2003, the city centre was virtually taken over by Eurovision delegates as they spent their week in the ]n capital. | |||

| ] | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| Preparations in the host venue typically begin approximately six weeks before the final, to accommodate building works and technical rehearsals before the arrival of the competing artists.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Anforderungsprofil an die Austragungsstätte des Eurovision Song Contest 2015 |trans-title=Requirements to the venue of the Eurovision Song Contest 2015 |url=http://kundendienst.orf.at/aktuelles/anforderungsprofl_austragungsstaette.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140531162001/http://kundendienst.orf.at/aktuelles/anforderungsprofl_austragungsstaette.pdf |archive-date=31 May 2014 |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=] |language=de}}</ref> Delegations will typically arrive in the host city two to three weeks before the live show, and each participating broadcaster nominates a head of delegation, responsible for coordinating the movements of their delegation and being that country's representative to the EBU.<ref name="Rules" /><ref>{{Cite web |title=Rules of the 2005 Eurovision Song Contest |url=http://www.eurovision.tv/searchfiles_english/574.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060210010517/http://www.eurovision.tv/searchfiles_english/574.htm |archive-date=10 February 2006 |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Members of each country's delegation include performers, composers, lyricists, members of the press, and—in the years where a live orchestra was present—a conductor.<ref name="HoDs">{{Cite web |date=14 January 2017 |title=Eurovision Song Contest: Heads of Delegation |url=https://eurovision.tv/about/organisers/heads-of-delegation/ |access-date=5 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Present if desired is a commentator, who provides commentary of the event for their country's radio and/or television feed in their country's own language in dedicated booths situated around the back of the arena behind the audience.<ref>{{Cite web |date=15 May 2011 |title=Commentator's guide to the commentators |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/commentator-s-guide-to-the-commentators |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Escudero |first=Victor M. |date=14 May 2017 |title=Commentators: The national hosts of Eurovision |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/commentators-sweden-mans-zelmerlow-edward-af-sillen |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> | |||

| Each country conducts two individual rehearsals behind closed doors, the first for 30 minutes and the second for 20 minutes.<ref name="2008 rehearsal schedule" /><ref>{{Cite web |last=Granger |first=Anthony |date=10 May 2023 |title=Eurovision 2023: EBU & BBC Discuss Voting, Rehearsals & Qualifiers Announcement |url=https://eurovoix.com/2023/05/10/eurovision-2023-ebu-bbc-conference/ |access-date=11 May 2023 |website=Eurovoix |language=en-GB}}</ref> Individual rehearsals for the semi-finalists commence the week before the live shows, with countries typically rehearsing in the order in which they will perform during the contest; rehearsals for the host country and the "Big Five" automatic finalists are held towards the end of the week.<ref name="2008 rehearsal schedule">{{Cite web |title=Eurovision Song Contest 2008: Rehearsal schedule |url=http://www.eurovision.tv/upload/media/ESC2008_rehearsals.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081221010818/http://www.eurovision.tv/upload/media/ESC2008_rehearsals.pdf |archive-date=21 December 2008 |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref><ref name="2018 rehearsal schedule">{{Cite web |date=27 April 2018 |title=Your ultimate guide to the Eurovision 2018 event weeks |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/guide-to-eurovision-2018-event-weeks-rehearal-schedule |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190518142209/https://eurovision.tv/story/guide-to-eurovision-2018-event-weeks-rehearal-schedule |archive-date=18 May 2019 |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Following rehearsals, delegations meet with the show's production team to review footage of the rehearsal and raise any special requirements or changes. "Meet and greet" sessions with accredited fans and press are held during these rehearsal weeks.<ref name="2008 rehearsal schedule" /><ref name="Event weeks">{{Cite web |date=21 March 2017 |title=Eurovision Song Contest: Event weeks |url=https://eurovision.tv/about/in-depth/event-weeks |access-date=3 July 2020 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> Each live show is preceded by three dress rehearsals, where the whole show is run in the same way as it will be presented on TV.<ref name="Event weeks" /> The second dress rehearsal, alternatively called the "jury show" or "evening preview show"<ref>{{Cite web |date=2019-03-27 |title=Tickets for Eurovision 2024 in Malmö |url=https://eurovision.tv/tickets |access-date=2023-12-03 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest |language=en}}</ref> and held the night before the broadcast, is used as a recorded back-up in case of technological failure, and performances during this show are used by each country's professional jury to determine their votes.<ref name="2018 rehearsal schedule" /><ref name="Event weeks" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=17 May 2013 |title=Time now for the all important Jury Final |url=https://eurovision.tv/story/time-now-for-the-all-important-jury-final |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190902160705/https://eurovision.tv/story/time-now-for-the-all-important-jury-final |archive-date=2 September 2019 |access-date=25 March 2021 |publisher=Eurovision Song Contest}}</ref> The delegations from the qualifying countries in each semi-final attend a qualifiers' press conference after their respective semi-final, and the winning delegation attends a winners' press conference following the final.<ref name="Event weeks" /> | |||

| == Eurovision Week == | |||

| The term "Eurovision Week" is used to refer to the week during which the Contest takes place. As it is a live show, the Eurovision Song Contest requires the performers to have perfected their acts in ]s in order for the big night to run smoothly. In addition to rehearsals in their home countries, every participant is given the opportunity to rehearse on the stage in the Eurovision auditorium. These rehearsals are held during the course of several days before the Saturday show, and consequently the delegations arrive in the host city many days before the event. This means, in turn, journalists and fans are also present during the preceding days, and the events of Eurovision last a lot longer than a few hours of television. A number of officially accredited hotels are selected for the delegations to stay in, and shuttle-bus services are used to transport the performers and accompanying people to and from the Contest venue. | |||