| Revision as of 16:20, 1 June 2009 editDbachmann (talk | contribs)227,714 edits rm unreferenced h2← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:40, 9 December 2024 edit undoUtherSRG (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators177,633 editsm Reverted edit by 2A02:AA7:4049:EEB8:E1C6:7CC2:37F8:4FDC (talk) to last version by Citation botTag: Rollback | ||

| (277 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Bony ridge located above the eye sockets of all primates}} | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| {{Infobox bone | |||

| | Name = Brow ridge | |||

| | Latin = | |||

| | Image = Gray134.png | |||

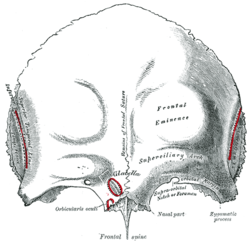

| | Caption = ]. Outer surface. Brow ridge labelled as "superciliary arch" at center right). | |||

| | Image2 = | |||

| | Caption2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | The '''brow ridge''', or '''supraorbital ridge''' known as '''superciliary arch''' in medicine, is a bony ridge located above the eye sockets of all ]s and some other animals. In ]s, the ] are located on their lower margin. | ||

| ==Structure== | |||

| ⚫ | The ''' |

||

| The brow ridge is a nodule or crest of bone situated on the ] of the ]. It forms the separation between the forehead portion itself (the ]) and the roof of the eye sockets (the ]). Normally, in humans, the ridges arch over each eye, offering mechanical protection. In other primates, the ridge is usually continuous and often straight rather than arched. The ridges are separated from the ] by a shallow groove. The ridges are most prominent medially, and are joined to one another by a smooth elevation named the ]. | |||

| Typically, the arches are more prominent in men than in women,<ref name="Patton">{{Cite book|last1=Patton|first1=Kevin T.|last2=Thibodeau|first2=Gary A.|title=Anthony's Textbook of Anatomy & Physiology - E-Book|date=2018|publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences|isbn=9780323709309|page=276|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_n1_DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA276}}</ref> and vary between different human populations. Behind the ridges, deeper in the bone, are the ]. | |||

| Other terms in use are: | |||

| * ''supraorbital arch'' | |||

| * ''supraorbital torus'' | |||

| * ''superciliary ridge'' | |||

| * ''arcus superciliaris'' (Latin, meaning "superciliary arch") | |||

| * ''supraorbital margin'' and ''the margin of the orbit'' | |||

| ===Terminology=== | |||

| ==Anthropological concept== | |||

| The brow ridges, being a prominent part of the face in some human populations and a trait linked to ], have a number of names in different disciplines. In vernacular English, the terms '''eyebrow bone''' or '''eyebrow ridge''' are common. The more technical terms '''frontal''' or '''supraorbital arch''', '''ridge''' or '''torus''' (or '''tori''' to refer to the plural, as the ridge is usually seen as a pair) are often found in anthropological or archaeological studies. In medicine, the term '''''arcus superciliaris''''' (]) or the English translation '''superciliary arch'''. This feature is different from the '''supraorbital margin''' and '''the margin of the orbit'''. | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | The size of these ridges varies also between different species of primates, either living or fossil. The closest living relatives of |

||

| Some ] distinguish between ''torus'' and ''ridge |

Some ] distinguish between '''frontal torus''' and '''supraorbital ridge'''.<ref>]. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071214135841/http://www.bartleby.com/61/92/S0909200.html# |date=2007-12-14 }}</ref> In anatomy, a '']'' is a projecting shelf of bone that unlike a ridge is rectilinear, unbroken and goes through ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071215060631/http://www.bartleby.com/61/35/T0283500.html# |date=2007-12-15 }}</ref> Some fossil ]s, in this use of the word, have the ''frontal torus'',<ref name=sollas/> but almost all modern humans only have the ridge.<ref>{{Cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4doajFJmvSsC&q=frontal+torus&pg=PA29 |title = The Origin of Humankind: Conference Proceedings of the International Symposium, Venice, 14-15 May 1998|isbn = 9781586030308|last1 = Aloisi|first1 = Massimiliano|year = 2000| publisher=IOS Press }}</ref> | ||

| == |

===Development=== | ||

| The brow ridge is a thick piece of bone on top of the eyes. Its purpose is to reinforce the weaker bones of the face in much the same way that the chin of modern humans was developed to reinforce their comparatively thin mandibles. This was necessary in pongids and early hominids because of the tremendous strain put on the cranium by their tremendous chewing apparatuses, which is best demonstrated by any of the members of the genus ]. The brow ridge was one of the last traits to be lost in the path to modern humans, and only disappeared with the development of the modern pronounced frontal lobe. This is one of the most salient differences between ''Homo sapiens'' and '']''. The name for this theory is the ]. | |||

| ]) shows "Caucasoid types". Caucasoids have the second largest brow ridge under Australoids.<!--pg 84-->.<ref name=Wilkenson />]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ====Spatial model==== | |||

| ⚫ | {{ |

||

| The Spatial model proposes that supraorbital torus development can be best explained in terms of the disparity between the anterior position of the orbital component relative to the neurocranium. | |||

| Much of the groundwork for the spatial model was laid down by Schultz (1940). He was the first to document that at later ] (after age 4) the growth of the orbit would outpace that of the eye. Consequently, he proposed that facial size is the most influential factor in orbital development, with orbital growth being only secondarily affected by size and ocular position. | |||

| ⚫ | == |

||

| Forensic anthropologist Caroline Wilkenson says that Australoids have the largest brow ridges "''with moderate to large supraorbital arches''"<!--pg87-->.<ref name=Wilkenson /> Caucasoids have the second largest brow ridges with "''moderate supraorbital ridges''"<!--pg 84-->.<ref name=Wilkenson /> Negroids have the third largest brow ridges with an "''undulating supraorbital ridge''".<ref name=Wilkenson /> Mongoloids are "''absent browridges''"<!--pg86-->, so they have the smallest brow ridges.<ref name=Wilkenson>Wilkenson, Caroline. Forensic Facial Reconstruction. Cambridge University Press. 2004. ISBN 0521820030</ref> | |||

| Weindenreich (1941) and Biegert (1957, 1963) argued that the supraorbital region can best be understood as a product of the orientation of its two components, the face and the neurocranium. | |||

| ⚫ | ==Bio-mechanical model== | ||

| Research done on this model has largely been based on earlier work of Endo (1965, 1966, 1970, and 1973). By applying pressure similar to the type associated with ], he carried out an analysis of the structural function of the supraorbital region on dry human and gorilla ]s. His findings indicated that the face acts as a pillar that carries and disperses tension caused by the forces produced during mastication. Russell (1982, 1985) and Oyen et al. (1979a) elaborated on this idea, suggesting that amplified facial projection necessitates the application of enhanced force to the anterior dentition in order to generate the same bite power that individuals with a dorsal deflection of the facial skull exert. In more prognathic individuals, this increased pressure triggers bone deposition to reinforce the brow ridges, until equilibrium is reached. | |||

| The most composed articulation of the spatial model was presented by Moss and Young (1960), who stated that "the presence… of supraorbital ridges is only the reflection of the spatial relationship between two functionally unrelated cephalic components, the orbit and the brain" (Moss and Young, 1960, p282). They proposed (as first articulated by Biegert in 1957) that during infancy the neurocranium extensively overlaps the orbit, a condition that prohibits ]. As the splanchnocranium grows, however, the orbits begin to advance, thus causing the anterior displacement of the face relative to the brain. Brow ridges then form as a result of this separation. | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | ====Bio-mechanical model==== | ||

| ⚫ | In a later series of papers, Russell |

||

| ⚫ | The bio-mechanical model predicts that morphological variation in torus size is the direct product of differential tension caused by mastication, as indicated by an increase in load/lever ratio and broad craniofacial angle.<ref>Oyen and Russell, 1984, p. 368-369</ref> | ||

| Research done on this model has largely been based on earlier work of Endo. By applying pressure similar to the type associated with ], he carried out an analysis of the structural function of the supraorbital region on dry human and gorilla ]s. His findings indicated that the face acts as a pillar that carries and disperses tension caused by the forces produced during mastication.<ref name=Endo1965>{{cite journal|author=Endo, B|year=1965|title= Distribution of Stress and Strain Produced in the Human Facial Skeleton by the Masticatory Force|journal= The Journal of Anthropological Society of Nippon|volume=73|issue=4|pages=123–136|doi=10.1537/ase1911.73.123|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name = Endo1970>{{cite journal|author=Endo, B|year=1970|title= Analysis of Stresses around the Orbit Due to Masseter and Temporalis Muscles Respectively|journal= The Journal of Anthropological Society of Nippon|volume=78|issue=4|pages=251–266|doi=10.1537/ase1911.78.251|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name=Endo1973>{{cite journal|author=Endo, B|year=1973|title=Stress analysis of the gorilla face.|journal=Primates|volume=14|pages=37–45|doi=10.1007/bf01730514|s2cid=23751360}}</ref><ref name= Endo1966>{{cite journal |author=Endo B |s2cid=16122254 |title=A biomechanical study of the human facial skeleton by means of strain-sensitive lacquer |journal=Okajimas Folia Anatomica Japonica |volume=42 |issue=4 |pages=205–17 |date=July 1966 |pmid=6013426 |doi=10.2535/ofaj1936.42.4_205|doi-access=free }}</ref> Russell and Oyen ''et al''. elaborated on this idea, suggesting that amplified facial projection necessitates the application of enhanced force to the anterior dentition in order to generate the same bite power that individuals with a dorsal deflection of the facial skull exert. In more ] individuals, this increased pressure triggers bone deposition to reinforce the brow ridges, until equilibrium is reached.<ref name=Russell1985>{{cite journal|author=Russell, MD|year=1985|title=The supraorbital torus: "A most remarkable peculiarity."|journal=Current Anthropology|doi=10.1086/203279|volume=26|pages=337|s2cid=146857927}}</ref><ref name=Russell1982>{{cite journal|journal=Am J Phys Anthropol|date=May 1982|volume=58|issue=1|pages=59–65|title=Tooth eruption and browridge formation|author=Russell MD|doi=10.1002/ajpa.1330580107|pmid=7124915|hdl=2027.42/37614|url=https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/37614/1/1330580107_ftp.pdf|hdl-access=free}}</ref><ref name=Oyen1970a>{{cite journal|author = Oyen, OJ, Rice, RW, and Cannon, MS|year=1979|title=Brow ridge structure and function in extant primates and Neanderthals|journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology|volume=51|pages=88–96|doi=10.1002/ajpa.1330510111 }}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | Oyen et al. conducted a cross-section study of '']'' in order to ascertain the relationship between palate length, incisor load and Masseter lever efficiency, relative to torus enlargement. Indications found of osteoblastic deposition in the ] were used as evidence for supraorbital enlargement. Oyen et al.’s data suggested that more prognathic individuals experienced a decrease in load/lever efficiency. This transmits tension via the frontal process of the maxilla to the supraorbital region, resulting in a contemporary reinforcement of this structure. This was also correlated to periods of tooth eruption.<ref name=Oyen1979a>{{cite journal |vauthors=Oyen OJ, Walker AC, Rice RW |title=Craniofacial growth in olive baboons (Papio cynocephalus anubis): browridge formation |journal=Growth |volume=43 |issue=3 |pages=174–87 |date=September 1979 |pmid=116911}}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | In a later series of papers, Russell developed aspects of this mode further. Employing an adult Australian sample, she tested the association between brow ridge formation and anterior dental loading, via the craniofacial angle (prosthion-nasion-metopion), ] breadth, and discontinuities in food preparation such as those observed between different age groups. Finding strong support for the first two criteria, she concluded that the supraorbital complex is formed as a result of increased tension due to the widening of the maxilla, thought to be positively correlated with the size of the ], as well as with the improper orientation of bone in the superior orbital region.<ref name=Russell1985 /><ref name=Shea>{{cite journal |jstor=2742880 |title=On skull form and the supraorbital torus in primates|journal=Current Anthropology|volume=27|issue=3|date=July 1986|doi=10.1086/203427|pages=257–260|last1=Shea|first1=Brian T.|last2=Russell|first2=Mary D.|s2cid=145273372}}</ref><!--- Russell 1986a and 1986b missing ---> | ||

| ===Function=== | |||

| ⚫ | {{See also|Human skeletal changes due to bipedalism}} | ||

| Some researchers have suggested that brow ridges function to protect the eyes and orbital bones during hand-to-hand combat, given that they are an incredibly dimorphic trait.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Carrier|first1=David|last2=Morgan|first2=Michael H.|date=2015|title=Protective buttressing of the hominin face|url=https://carrier.biology.utah.edu/Dave%27s%20PDF/Protective%20buttressing%20of%20the%20face.pdf|journal=Biological Reviews|volume=90|issue=1 |pages=330–346|doi=10.1111/brv.12112 |pmid=24909544 |s2cid=14777701 }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ===Paleolithic humans=== | ||

| Pronounced brow ridges were a common feature among paleolithic humans. Early modern people such as those from the finds from ] and ] had thick, large brow ridges, but they differ from those of ] like ] by having a ] or notch, forming a groove through the ridge above each eye, although there were exceptions, such as Skhul 2 in which the ridge was unbroken, unlike other members of her tribe.<ref name="Homo">{{cite web |url=http://archaeologyinfo.com/homo-sapiens/ |title=''Homo sapiens'' - ''H. sapiens'' (Anatomically Modern Humans - AMH) are the species we belong to. |access-date=2019-01-29 |archive-date=2011-09-08 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110908071119/http://archaeologyinfo.com/homo-sapiens/ |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Bhupendra|first=P.|title=Forehead Anatomy|url=http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/834862-overview|work=Medscape references|publisher=]|access-date=11 December 2013}}</ref> This splits the ridge into central parts and distal parts. In current humans, almost always only the central sections of the ridge are preserved (if preserved at all). This contrasts with many archaic and early modern humans, where the brow ridge is pronounced and unbroken.<ref>{{cite web|title=How to ID a modern human?|url=http://www.nhm.ac.uk/about-us/news/2012/may/how-to-id-a-modern-human109960.html|work=News, 2012|publisher=]|access-date=11 December 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ==Other animals== | |||

| ⚫ | ] with a frontal torus]] | ||

| ⚫ | The size of these ridges varies also between different species of primates, either living or fossil. The closest living relatives of ]s, the ] and especially ]s or ]s, have a very pronounced supraorbital ridge, which has also been called a ''frontal torus,''<ref name= sollas>{{Cite journal |author-link=William Johnson Sollas |last1=Sollas |first1=W.J. |title= The Taungs Skull |journal= Nature |volume=115 |issue=2902 |pages=908–9 |doi=10.1038/115908a0 |bibcode=1925Natur.115..908S|year=1925 |s2cid=4125405 }}</ref> while in modern humans and ]s, it is relatively reduced. The fossil record indicates that the supraorbital ridge in early hominins was reduced as the cranial vault grew; ] became positioned above rather than behind the eyes, giving a more vertical forehead. | ||

| Supraorbital ridges are also present in some other animals, such as ],<ref>{{cite journal | url =https://zslpublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb04830.x|title=The supraorbital ridge as an indicator of age in wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus)|author=H. H. Kolb|journal=Journal of Zoology|doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb04830.x| date=June 1992|volume=227 |issue=2 |pages=334–338 | accessdate =16 February 2023}}</ref> ]<ref>{{cite web | url =https://www.nationaleaglecenter.org/eagle-glossary/|title=Learn About Eagles from A to Z|publisher=]|accessdate =16 February 2023}}</ref> and certain species of sharks.<ref>{{cite journal | url =https://journals.australian.museum/ogilby-1893-rec-aust-mus-25-6263/|title=Description of a new shark from the Tasmanian coast|journal=Records of the Australian Museum|author=J. Douglas Ogilby | date=1893|volume=2 |issue=5 |pages=62–63 |doi=10.3853/j.0067-1975.2.1893.1194 | accessdate =16 February 2023}}</ref> The presence of a supraorbital ridge in the ] has been used to distinguish it among related species.<ref>{{cite journal | url =https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287854137 |title=First Report of the Herb Field Mouse, Apodemus uralensis (Pallas, 1811) from Mongolia|journal=Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences|page=36|issn=2225-4994| date=| accessdate =16 February 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{Portal|Anatomy}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{Gray's}} | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=September 2008}} | |||

| {{ |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| *Endo, B (1965) Distribution of stress and strain produced in the human face by masticatory forces. Journal of the Anthropological Society of Nippon. 73:123-136. | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| *Endo, B (1970) Analysis of the stress around the orbit due to masseter and temporalis muscles. Journal of the Anthropological Society of Nippon. 78:251-266. | |||

| *{{Cite journal|last1=Endo |first1=B |year=1965 |title= Distribution of Stress and Strain Produced in the Human Facial Skeleton by the Masticatory Force|journal= The Journal of Anthropological Society of Nippon|volume=73 |pages=123–36|doi=10.1537/ase1911.73.123|issue=4|url=https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ase1911/73/4/73_4_123/_pdf |doi-access=free}} | |||

| *Endo, B (1973) Stress analysis of the gotrilla face. Primates 14:37-45 | |||

| *{{Cite journal|last1=Endo |first1=B |year=1970 |title= Analysis of Stresses around the Orbit Due to Masseter and Temporalis Muscles Respectively|journal= The Journal of Anthropological Society of Nippon|volume=78 |pages=251–66|doi=10.1537/ase1911.78.251|issue=4|doi-access=free}} | |||

| *Russell, MD (1985) The supraorbital torus: “A most remarkable peculiarity.” Current Anthropology. 58:59-65. | |||

| *{{Cite journal|last1=Endo |first1=B |year=1973 |title=Stress analysis of the gorilla face |journal=Primates |volume=14 |pages=37–45 |doi=10.1007/bf01730514|s2cid=23751360 }} | |||

| *Oyen, OJ, Rice, RW, and Cannon, MS (1970a) Browridge structure and functionin extant primates and Neanderthals. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 51:88-96. | |||

| *{{Cite journal|first1=Mary Doria |last1=Russell |date=June 1985 |title=The Supraorbital Torus: 'A Most Remarkable Peculiarity' |journal=Current Anthropology |volume=26 |issue=3 |pages=337–360 |doi=10.1086/203279|s2cid=146857927 }} | |||

| *{{Cite journal|last1=Oyen |first1=Ordean J. |last2=Rice |first2=Robert W. |last3=Cannon |first3=M. Samuel |date=July 1970 |title=Browridge structure and function in extant primates and Neanderthals |journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology |volume=51 |issue=1 |pages=83–95 |doi=10.1002/ajpa.1330510111}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|Superciliary arch}} | |||

| *, California State University at Chico site. | *, California State University at Chico site. | ||

| *, Webster's Online Dictionary. | |||

| {{Skull}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:40, 9 December 2024

Bony ridge located above the eye sockets of all primates| Brow ridge | |

|---|---|

Frontal bone. Outer surface. Brow ridge labelled as "superciliary arch" at center right). Frontal bone. Outer surface. Brow ridge labelled as "superciliary arch" at center right). | |

| Identifiers | |

| TA98 | A02.1.03.005 |

| TA2 | 524 |

| FMA | 52850 |

| Anatomical terms of bone[edit on Wikidata] | |

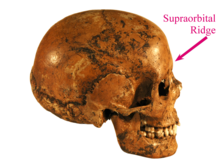

The brow ridge, or supraorbital ridge known as superciliary arch in medicine, is a bony ridge located above the eye sockets of all primates and some other animals. In humans, the eyebrows are located on their lower margin.

Structure

The brow ridge is a nodule or crest of bone situated on the frontal bone of the skull. It forms the separation between the forehead portion itself (the squama frontalis) and the roof of the eye sockets (the pars orbitalis). Normally, in humans, the ridges arch over each eye, offering mechanical protection. In other primates, the ridge is usually continuous and often straight rather than arched. The ridges are separated from the frontal eminences by a shallow groove. The ridges are most prominent medially, and are joined to one another by a smooth elevation named the glabella.

Typically, the arches are more prominent in men than in women, and vary between different human populations. Behind the ridges, deeper in the bone, are the frontal sinuses.

Terminology

The brow ridges, being a prominent part of the face in some human populations and a trait linked to sexual dimorphism, have a number of names in different disciplines. In vernacular English, the terms eyebrow bone or eyebrow ridge are common. The more technical terms frontal or supraorbital arch, ridge or torus (or tori to refer to the plural, as the ridge is usually seen as a pair) are often found in anthropological or archaeological studies. In medicine, the term arcus superciliaris (Latin) or the English translation superciliary arch. This feature is different from the supraorbital margin and the margin of the orbit.

Some paleoanthropologists distinguish between frontal torus and supraorbital ridge. In anatomy, a torus is a projecting shelf of bone that unlike a ridge is rectilinear, unbroken and goes through glabella. Some fossil hominins, in this use of the word, have the frontal torus, but almost all modern humans only have the ridge.

Development

Spatial model

The Spatial model proposes that supraorbital torus development can be best explained in terms of the disparity between the anterior position of the orbital component relative to the neurocranium.

Much of the groundwork for the spatial model was laid down by Schultz (1940). He was the first to document that at later stages of development (after age 4) the growth of the orbit would outpace that of the eye. Consequently, he proposed that facial size is the most influential factor in orbital development, with orbital growth being only secondarily affected by size and ocular position.

Weindenreich (1941) and Biegert (1957, 1963) argued that the supraorbital region can best be understood as a product of the orientation of its two components, the face and the neurocranium.

The most composed articulation of the spatial model was presented by Moss and Young (1960), who stated that "the presence… of supraorbital ridges is only the reflection of the spatial relationship between two functionally unrelated cephalic components, the orbit and the brain" (Moss and Young, 1960, p282). They proposed (as first articulated by Biegert in 1957) that during infancy the neurocranium extensively overlaps the orbit, a condition that prohibits brow ridge development. As the splanchnocranium grows, however, the orbits begin to advance, thus causing the anterior displacement of the face relative to the brain. Brow ridges then form as a result of this separation.

Bio-mechanical model

The bio-mechanical model predicts that morphological variation in torus size is the direct product of differential tension caused by mastication, as indicated by an increase in load/lever ratio and broad craniofacial angle.

Research done on this model has largely been based on earlier work of Endo. By applying pressure similar to the type associated with chewing, he carried out an analysis of the structural function of the supraorbital region on dry human and gorilla skulls. His findings indicated that the face acts as a pillar that carries and disperses tension caused by the forces produced during mastication. Russell and Oyen et al. elaborated on this idea, suggesting that amplified facial projection necessitates the application of enhanced force to the anterior dentition in order to generate the same bite power that individuals with a dorsal deflection of the facial skull exert. In more prognathic individuals, this increased pressure triggers bone deposition to reinforce the brow ridges, until equilibrium is reached.

Oyen et al. conducted a cross-section study of Papio anubis in order to ascertain the relationship between palate length, incisor load and Masseter lever efficiency, relative to torus enlargement. Indications found of osteoblastic deposition in the glabella were used as evidence for supraorbital enlargement. Oyen et al.’s data suggested that more prognathic individuals experienced a decrease in load/lever efficiency. This transmits tension via the frontal process of the maxilla to the supraorbital region, resulting in a contemporary reinforcement of this structure. This was also correlated to periods of tooth eruption.

In a later series of papers, Russell developed aspects of this mode further. Employing an adult Australian sample, she tested the association between brow ridge formation and anterior dental loading, via the craniofacial angle (prosthion-nasion-metopion), maxilla breadth, and discontinuities in food preparation such as those observed between different age groups. Finding strong support for the first two criteria, she concluded that the supraorbital complex is formed as a result of increased tension due to the widening of the maxilla, thought to be positively correlated with the size of the masseter muscle, as well as with the improper orientation of bone in the superior orbital region.

Function

See also: Human skeletal changes due to bipedalismSome researchers have suggested that brow ridges function to protect the eyes and orbital bones during hand-to-hand combat, given that they are an incredibly dimorphic trait.

Paleolithic humans

Pronounced brow ridges were a common feature among paleolithic humans. Early modern people such as those from the finds from Jebel Irhoud and Skhul and Qafzeh had thick, large brow ridges, but they differ from those of archaic humans like Neanderthals by having a supraorbital foramen or notch, forming a groove through the ridge above each eye, although there were exceptions, such as Skhul 2 in which the ridge was unbroken, unlike other members of her tribe. This splits the ridge into central parts and distal parts. In current humans, almost always only the central sections of the ridge are preserved (if preserved at all). This contrasts with many archaic and early modern humans, where the brow ridge is pronounced and unbroken.

Other animals

The size of these ridges varies also between different species of primates, either living or fossil. The closest living relatives of humans, the great apes and especially gorillas or chimpanzees, have a very pronounced supraorbital ridge, which has also been called a frontal torus, while in modern humans and orangutans, it is relatively reduced. The fossil record indicates that the supraorbital ridge in early hominins was reduced as the cranial vault grew; the frontal portion of the brain became positioned above rather than behind the eyes, giving a more vertical forehead.

Supraorbital ridges are also present in some other animals, such as wild rabbits, eagles and certain species of sharks. The presence of a supraorbital ridge in the Korean field mouse has been used to distinguish it among related species.

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 135 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 135 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Patton, Kevin T.; Thibodeau, Gary A. (2018). Anthony's Textbook of Anatomy & Physiology - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 276. ISBN 9780323709309.

- American Heritage Dictionary. supraorbital Archived 2007-12-14 at the Wayback Machine

- torus Archived 2007-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sollas, W.J. (1925). "The Taungs Skull". Nature. 115 (2902): 908–9. Bibcode:1925Natur.115..908S. doi:10.1038/115908a0. S2CID 4125405.

- Aloisi, Massimiliano (2000). The Origin of Humankind: Conference Proceedings of the International Symposium, Venice, 14-15 May 1998. IOS Press. ISBN 9781586030308.

- Oyen and Russell, 1984, p. 368-369

- Endo, B (1965). "Distribution of Stress and Strain Produced in the Human Facial Skeleton by the Masticatory Force". The Journal of Anthropological Society of Nippon. 73 (4): 123–136. doi:10.1537/ase1911.73.123.

- Endo, B (1970). "Analysis of Stresses around the Orbit Due to Masseter and Temporalis Muscles Respectively". The Journal of Anthropological Society of Nippon. 78 (4): 251–266. doi:10.1537/ase1911.78.251.

- Endo, B (1973). "Stress analysis of the gorilla face". Primates. 14: 37–45. doi:10.1007/bf01730514. S2CID 23751360.

- Endo B (July 1966). "A biomechanical study of the human facial skeleton by means of strain-sensitive lacquer". Okajimas Folia Anatomica Japonica. 42 (4): 205–17. doi:10.2535/ofaj1936.42.4_205. PMID 6013426. S2CID 16122254.

- ^ Russell, MD (1985). "The supraorbital torus: "A most remarkable peculiarity."". Current Anthropology. 26: 337. doi:10.1086/203279. S2CID 146857927.

- Russell MD (May 1982). "Tooth eruption and browridge formation" (PDF). Am J Phys Anthropol. 58 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330580107. hdl:2027.42/37614. PMID 7124915.

- Oyen, OJ, Rice, RW, and Cannon, MS (1979). "Brow ridge structure and function in extant primates and Neanderthals". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 51: 88–96. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330510111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Oyen OJ, Walker AC, Rice RW (September 1979). "Craniofacial growth in olive baboons (Papio cynocephalus anubis): browridge formation". Growth. 43 (3): 174–87. PMID 116911.

- Shea, Brian T.; Russell, Mary D. (July 1986). "On skull form and the supraorbital torus in primates". Current Anthropology. 27 (3): 257–260. doi:10.1086/203427. JSTOR 2742880. S2CID 145273372.

- Carrier, David; Morgan, Michael H. (2015). "Protective buttressing of the hominin face" (PDF). Biological Reviews. 90 (1): 330–346. doi:10.1111/brv.12112. PMID 24909544. S2CID 14777701.

- "Homo sapiens - H. sapiens (Anatomically Modern Humans - AMH) are the species we belong to". Archived from the original on 2011-09-08. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- Bhupendra, P. "Forehead Anatomy". Medscape references. Medscape. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "How to ID a modern human?". News, 2012. Natural History Museum, London. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- H. H. Kolb (June 1992). "The supraorbital ridge as an indicator of age in wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus)". Journal of Zoology. 227 (2): 334–338. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb04830.x. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- "Learn About Eagles from A to Z". National Eagle Center. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- J. Douglas Ogilby (1893). "Description of a new shark from the Tasmanian coast". Records of the Australian Museum. 2 (5): 62–63. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.2.1893.1194. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- "First Report of the Herb Field Mouse, Apodemus uralensis (Pallas, 1811) from Mongolia". Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences: 36. ISSN 2225-4994. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

Further reading

- Endo, B (1965). "Distribution of Stress and Strain Produced in the Human Facial Skeleton by the Masticatory Force". The Journal of Anthropological Society of Nippon. 73 (4): 123–36. doi:10.1537/ase1911.73.123.

- Endo, B (1970). "Analysis of Stresses around the Orbit Due to Masseter and Temporalis Muscles Respectively". The Journal of Anthropological Society of Nippon. 78 (4): 251–66. doi:10.1537/ase1911.78.251.

- Endo, B (1973). "Stress analysis of the gorilla face". Primates. 14: 37–45. doi:10.1007/bf01730514. S2CID 23751360.

- Russell, Mary Doria (June 1985). "The Supraorbital Torus: 'A Most Remarkable Peculiarity'". Current Anthropology. 26 (3): 337–360. doi:10.1086/203279. S2CID 146857927.

- Oyen, Ordean J.; Rice, Robert W.; Cannon, M. Samuel (July 1970). "Browridge structure and function in extant primates and Neanderthals". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 51 (1): 83–95. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330510111.

External links

- The Frontal Bone, California State University at Chico site.

| Neurocranium of the skull | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occipital |

| ||||||||||

| Parietal | |||||||||||

| Frontal |

| ||||||||||

| Temporal |

| ||||||||||

| Sphenoid |

| ||||||||||

| Ethmoid |

| ||||||||||