| Revision as of 11:56, 23 July 2009 editBeno1000 (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers3,659 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:41, 17 November 2024 edit undoTobby72 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users37,784 edits add image | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Set of ethnic groups in Southeast Asia and Andaman islands}} | |||

| ] woman]] | |||

| {{About|the ethnic groups|the shrub|Citharexylum berlandieri|the municipality|El Negrito|the bird genus|Lessonia (bird)}} | |||

| {{History of the Philippines}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|Pygmy peoples}} | |||

| ]'s map of racial categories from ''On the Geographical Distribution of the Chief Modifications of Mankind'' (]). {{legend|#a14308|1: ]}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2020}} | |||

| {{legend|#682b05|2: ]}} | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| {{legend|#060606|3: ]es}} | |||

| | group = Negrito | |||

| {{legend|#ffcccc|4: ]}} | |||

| | image = A LUZON NEGRITO WITH SPEAR.jpg | |||

| {{legend|#328a85|5: ]s}} | |||

| | caption = A Luzon Negrito with spear | |||

| {{legend|#ff0000|6: ]}} | |||

| | population = | |||

| {{legend|#efc417|7: ]}} | |||

| | regions = Isolated geographic regions in ] and ] | |||

| {{legend|#c6520a|8: ]}} | |||

| | languages = ], ], ] | |||

| {{legend|#cb780a|8: ]}} | |||

| | religions = ], ], '']'', ], ], ], ] | |||

| {{legend|#cb970a|8: ]}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{legend|#f9b90d|9: ]}} | |||

| Huxley states: 'It is to the Xanthochroi and Melanochroi, taken together, that the absurd denomination of "Caucasian" is usually applied'.<ref>] "" (1870) ''Journal of the Ethnological Society of London''</ref>]] | |||

| The term '''''Negrito''''' ({{IPAc-en|n|ɪ|ˈ|ɡ|r|iː|t|oʊ}}; {{lit|little ]}}) refers to several diverse ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of ] and the ]. Populations often described as Negrito include: the ] (including the ], the ], the ], and the ]) of the Andaman Islands, the ] peoples (among them, the ]) of ], the ] of ], as well as the ] of ], the ] and ] of ], the ] of ], and about 30 other officially recognized ]. | |||

| {{See also|Timeline of Philippine history}} | |||

| The term '''Negrito''' refers to several ethnic groups in isolated parts of ].<ref>Snow, Philip. ''The Star Raft: China's Encounter With Africa.'' Cornell Univ. Press, 1989 (ISBN 0801495830)</ref> | |||

| Their current populations include the ], Agta, Ayta, ], ] and at least 25 other tribes of the ], the ] of the ], the ] of ] and 12 ] tribes of the ] of the Indian Ocean. | |||

| Negritos share some common physical features with African ] populations, including short stature, ] texture, and dark skin; however, their origin and the route of their migration to Asia is still a matter of great speculation. They are genetically distant from Africans at most loci studied thus far (except for MCR1, which codes for dark skin). | |||

| They have also been shown to have separated early from Asians, suggesting that they are either surviving descendants of settlers from an early migration out of Africa, or that they are descendants of one of the founder populations of modern humans.<ref name=Kashyap>Kashyap VK, Sitalaximi T, Sarkar BN, Trivedi R 2003. . ''The International Journal of Human Genetics'', 3: 5-11.</ref> | |||

| On July 8, the AP reported that ], the foreign minister to caretaker leader ] who took over as the president of ] after President Manuel Zelaya was ousted in a coup, used the term "negrito," to describe ] on several occasions <ref name=AP_obama_honduras>Enrique Ortez Colindres calls Obama negrito[http://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20090708/pl_afp/honduraspoliticsmilitarycoupus_20090708145552 ''US envoy blasts Honduran minister for racist comments''.</ref>. | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| The word ''Negrito,'' the Spanish ] of '']'', is used to mean "little black person." This usage was coined by 16th-century Spanish ] operating in the Philippines, and was borrowed by other European travellers and colonialists across Austronesia to label various peoples perceived as sharing relatively small physical stature and dark skin.<ref name=Manickham-2009>{{cite book|last=Manickham|first=Sandra Khor|editor=Hägerdal, Hans|title=Responding to the West: Essays on Colonial Domination and Asian Agency|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Onr3-thtL2MC&pg=PA69|year=2009|publisher=Amsterdam University Press|isbn=978-90-8964-093-2|pages=69–79|chapter=Africans in Asia: The Discourse of 'Negritos' in Early Nineteenth-century Southeast Asia}}</ref> Contemporary usage of an alternative Spanish epithet, ''Negrillos'', also tended to bundle these peoples with the ] of ] on the basis of perceived similarities in stature and complexion.<ref name=Manickham-2009/> (Historically, the label ''Negrito'' has also been used to refer to African pygmies.)<ref>See, for example: ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' Eleventh Edition, 1910–1911: "Second are the large Negrito family, represented in Africa by the dwarf-races of the equatorial forests, the ], ]s, ]s and others..." (p. 851)</ref> The appropriateness of bundling peoples of different ] by similarities in stature and complexion has been called into question.<ref name=Manickham-2009/> | |||

| The term "Negrito" is the ] diminutive of ], i.e. "little black person", referring to their small stature, and was coined by early European explorers who assumed that the Negritos were recent arrivals from Africa. | |||

| == Population == | |||

| Occasionally, some Negritos are referred to as ], bundling them with peoples of similar physical stature in Central Africa, and likewise, the term Negrito was previously occasionally used to refer to African Pygmies.<ref>''Encyclopædia Britannica'' Eleventh Edition, 1910–1911: "Second are the large Negrito family, represented in Africa by the dwarf-races of the equatorial forests, the ], ]s, ]s and others..." (pg. 851)</ref> | |||

| There are over 100,000 Negritos in the Philippines. In 2010, there were 50,236 Aeta people in the Philippines.<ref name="pop">{{cite web |url=https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/PHIILIPPINES_FINAL%20PDF.pdf |title=2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) - Philippines |publisher=Philippine Statistics Authority |access-date=May 19, 2020 |archive-date=June 7, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200607120654/https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/PHIILIPPINES_FINAL%20PDF.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The Ati people 55,473 (2020 census)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/attachments/ird/pressrelease/Ethnicity_Statistical%20Table.xlsx|title=Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)|publisher=Philippine Statistics Authority|access-date=6 July 2023}}</ref> Officially, Malaysia had approximately 4,800 Negrito (Semangs).<ref name="Endicott">{{cite book|author=Kirk Endicott|title=Malaysia's Original People: Past, Present and Future of the Orang Asli. Introduction|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286937916|publisher=NUS Press, National University of Singapore Press. 2016, pp. 1-38|isbn=978-9971-69-861-4|access-date=2019-01-12|date=27 November 2015}} {{in lang|en}}</ref> This number increases if we include some of the populations or individual groups among ] who have either assimilated Negrito population or have admixed origins. According to the 2006 census, the number of Orang Asli was 141,230 <ref>{{cite web|author=|title=JAKOA Program|url=http://www.jakoa.gov.my/en/orang-asli/program-jakoa/|publisher=Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli (JAKOA)|access-date=2021-03-28|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170923134202/http://www.jakoa.gov.my/en/orang-asli/program-jakoa/|archive-date=2017-09-23|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Andamanese of India with just c. over 500. Thailand Negrito Maniq is estimated 300, divided into several clans.<ref name="TheMani">{{cite web|last1=Thonghom|last2=Weber|first2=George|title=36. The Negrito of Thailand; The Mani|url=http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/chapter36/text36.htm|website=Andaman.org|accessdate=23 December 2017|url-status=bot: unknown|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130520173144/http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/chapter36/text36.htm|archive-date=20 May 2013}}</ref><ref name=":0">''Primal Survivor: Season 5, episode 1''</ref> Other puts it at 382<ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2644750/calls-for-maniq-tribe-to-get-their-own-patch | title=Calls for Maniq tribe to get their own patch | newspaper=Bangkok Post }}</ref> or less than 500.<ref> 2016 https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/special-reports/1139777/no-common-ground</ref> | |||

| == Culture == | |||

| Sometimes the term "]" will be used when referring to these groups, especially to their superficial physical features, such as their hair texture and skin color. | |||

| ] | |||

| Most groups designated as "Negrito" lived as ]s, while some also used ], such as plant harvesting. Today most live assimilated to the majority population of their respective homeland. Discrimination and ] are often problems, caused either by their lower social position and/or their hunter-gatherer lifestyles.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.rutufoundation.org/hunting-gathering-in-the-tropical-rainforest-something-for-children/|title=The {{sic|succ|esful|nolink=y}} revival of Negrito culture in the Philippines|date=2015-05-06|website=Rutu Foundation|language=en-US|access-date=2019-07-19}}</ref> | |||

| According to James J.Y. Liu, a professor of comparative literature, the Chinese term '']'' ({{Zh-t|崑崙}}) means Negrito.<ref name=liu>Liu, James J.Y. ''The Chinese Knight Errant''. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1967 (ISBN 0-2264-8688-5)</ref> | |||

| ==Origins== | ==Origins== | ||

| {{Seealso|Genetic history of East Asians|Peopling of Southeast Asia}} | |||

| ] | |||

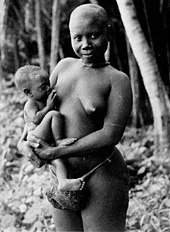

| ] mother with her baby (], ], 1905)]] | |||

| Based on perceived physical similarities, Negritos were once considered a single population of closely related people. However, genetic studies suggest that they consist of several separate groups descended from the same ancient ] meta-population that gave rise to modern ] and ], as well as displaying genetic heterogeneity. The Negritos form the indigenous population of Southeast Asia, but were largely absorbed by ] and ] groups who migrated from southern East Asia into Mainland and Insular Southeast Asia with the ] expansion. The remainders form minority groups in geographically isolated regions.<ref>{{Cite book |author=Sofwan Noerwidi |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CDDFDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA92 |title=New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory |date=2017 |publisher=ANU Press |isbn=978-1-76046-095-2 |editor-last=Piper |editor-first=Philip J. |location=Acton, Australian Capital Territory |page=92 |language=en |chapter=Using Dental Metrical Analysis to Determine the Terminal Pleistocene and Holocene Population History of Java |editor-last2=Matsumura |editor-first2=Hirofumi |editor-last3=Bulbeck |editor-first3=David}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Chaubey |first1=Gyaneshwer |last2=Endicott |first2=Phillip |title=The Andaman Islanders in a Regional Genetic Context: Reexamining the Evidence for an Early Peopling of the Archipelago from South Asia |journal=Human Biology |date=June 2013 |volume=85 |issue=1–3 |pages=153–172 |doi=10.3378/027.085.0307 |pmid=24297224 |s2cid=7774927 |url=https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol85/iss1/7 }}</ref><ref name="Basu 1594–1599">{{Cite journal|last1=Basu|first1=Analabha|last2=Sarkar-Roy|first2=Neeta|last3=Majumder|first3=Partha P.|date=2016|title=Genomic reconstruction of the history of extant populations of India reveals five distinct ancestral components and a complex structure|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|volume=113|issue=6|pages=1594–1599|doi=10.1073/pnas.1513197113|pmc=4760789|pmid=26811443|bibcode=2016PNAS..113.1594B|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Larena">{{Cite journal|last1=Larena|first1=Maximilian|last2=Sanchez-Quinto|first2=Federico|last3=Sjödin|first3=Per|last4=McKenna|first4=James|last5=Ebeo|first5=Carlo|last6=Reyes|first6=Rebecca|last7=Casel|first7=Ophelia|last8=Huang|first8=Jin-Yuan|last9=Hagada|first9=Kim Pullupul|last10=Guilay|first10=Dennis|last11=Reyes|first11=Jennelyn|date=2021|title=Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America|volume=118|issue=13|at=e2026132118|doi=10.1073/pnas.2026132118|pmc=8020671|pmid=33753512|bibcode=2021PNAS..11826132L |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="Carlhoff 543–547">{{Cite journal|last1=Carlhoff|first1=Selina|last2=Duli|first2=Akin|last3=Nägele|first3=Kathrin|last4=Nur|first4=Muhammad|last5=Skov|first5=Laurits|last6=Sumantri|first6=Iwan|last7=Oktaviana|first7=Adhi Agus|last8=Hakim|first8=Budianto|last9=Burhan|first9=Basran|last10=Syahdar|first10=Fardi Ali|last11=McGahan|first11=David P.|date=2021|title=Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea|journal=Nature|language=en|volume=596|issue=7873|pages=543–547|doi=10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6| pmc=8387238 |pmid=34433944|bibcode=2021Natur.596..543C|hdl=10072/407535|hdl-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Tagore|first1=Debashree|last2=Aghakhanian|first2=Farhang|last3=Naidu|first3=Rakesh|last4=Phipps|first4=Maude E.|last5=Basu|first5=Analabha|date=2021|title=Insights into the demographic history of Asia from common ancestry and admixture in the genomic landscape of present-day Austroasiatic speakers|journal=BMC Biology|volume=19|issue=1|page=61|doi=10.1186/s12915-021-00981-x|pmc=8008685|pmid=33781248 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Yang |first1=Melinda A. |title=A genetic history of migration, diversification, and admixture in Asia |journal=Human Population Genetics and Genomics |date=6 January 2022 |pages=1–32 |doi=10.47248/hpgg2202010001 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Yew |first1=Chee-Wei |last2=Lu |first2=Dongsheng |last3=Deng |first3=Lian |last4=Wong |first4=Lai-Ping |last5=Ong |first5=Rick Twee-Hee |last6=Lu |first6=Yan |last7=Wang |first7=Xiaoji |last8=Yunus |first8=Yushimah |last9=Aghakhanian |first9=Farhang |last10=Mokhtar |first10=Siti Shuhada |last11=Hoque |first11=Mohammad Zahirul |last12=Voo |first12=Christopher Lok-Yung |last13=Abdul Rahman |first13=Thuhairah |last14=Bhak |first14=Jong |last15=Phipps |first15=Maude E. |last16=Xu |first16=Shuhua |last17=Teo |first17=Yik-Ying |last18=Kumar |first18=Subbiah Vijay |last19=Hoh |first19=Boon-Peng |title=Genomic structure of the native inhabitants of Peninsular Malaysia and North Borneo suggests complex human population history in Southeast Asia |journal=Human Genetics |date=February 2018 |volume=137 |issue=2 |pages=161–173 |doi=10.1007/s00439-018-1869-0 |pmid=29383489 |s2cid=253969988 |quote=The analysis of time of divergence suggested that ancestors of Negrito were the earliest settlers in the Malay Peninsula, whom first separated from the Papuans ~ 50-33 thousand years ago (kya), followed by East Asian (~ 40-15 kya)...}}</ref> | |||

| Genetic studies provided mixed evidence of modern Negrito populations, with admixtures in different. Studies indicate that Negrito populations are closer to their neighboring non-Negrito communities in their paternal heritage and overall DNA on average.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Aghakhanian |first1=Farhang |last2=Yunus |first2=Yushima |last3=Naidu |first3=Rakesh |last4=Jinam |first4=Timothy |last5=Manica |first5=Andrea |last6=Hoh |first6=Boon Peng |last7=Phipps |first7=Maude E. |display-authors=2 |title=Unravelling the Genetic History of Negritos and Indigenous Populations of Southeast Asia |journal=Genome Biology and Evolution |date=14 April 2015 |volume=7 |issue=5 |pages=1206–1215 |doi=10.1093/gbe/evv065 |pmid=25877615 |pmc=4453060 |issn=1759-6653}}{{Creative Commons text attribution notice|cc=by4|from this source=yes}}</ref><ref>Endicott et al. 2003; Thangaraj et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2011), Y chromosome (Delfin et al. 2011; Scholes et al. 2011), and autosomal (HUGO Pan-Asia SNP Consortium 2009) studies indicate that Negrito populations are closer to their neighboring non-Negrito communities.</ref> | |||

| Being among the least-known of all living human groups, the origins of the Negrito people is a much debated topic. The ] term for them is '']'', or '' original people''. | |||

| It has been found that the physical and morphological phenotypes of Negritos, such as short stature, a wide and snub nose, curly hair and dark skin, "''are shaped by novel mechanisms for adaptation to tropical rainforests''" through ] and ], rather than a remnant of a shared common ancestor, as suggested previously by some researchers.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Stock |first1=Jay T. |title=The Skeletal Phenotype of 'Negritos' from the Andaman Islands and Philippines Relative to Global Variation among Hunter-Gatherers |journal=Human Biology |date=June 2013 |volume=85 |issue=1–3 |pages=67–94 |doi=10.3378/027.085.0304 |pmid=24297221 |s2cid=32964023 |url=https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol85/iss1/4 |quote=Although general similarities in size and proportions remain between the Andamanese and Aeta, differences in humero-femoral indices and arm length between these groups and the Efé demonstrate that there is not a generic 'pygmy' phenotype. Our interpretations of negrito origins and adaptation must account for this phenotypic variation.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Zhang |first1=Xiaoming |last2=Liu |first2=Qi |last3=Zhang |first3=Hui |last4=Zhao |first4=Shilei |last5=Huang |first5=Jiahui |last6=Sovannary |first6=Tuot |last7=Bunnath |first7=Long |last8=Aun |first8=Hong Seang |last9=Samnom |first9=Ham |last10=Su |first10=Bing |last11=Chen |first11=Hua |title=The distinct morphological phenotypes of Southeast Asian aborigines are shaped by novel mechanisms for adaptation to tropical rainforests |journal=National Science Review |date=31 March 2022 |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=nwab072 |doi=10.1093/nsr/nwab072 |pmid=35371514 |pmc=8970429 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Deng |first1=Lian |last2=Pan |first2=Yuwen |last3=Wang |first3=Yinan |last4=Chen |first4=Hao |last5=Yuan |first5=Kai |last6=Chen |first6=Sihan |last7=Lu |first7=Dongsheng |last8=Lu |first8=Yan |last9=Mokhtar |first9=Siti Shuhada |last10=Rahman |first10=Thuhairah Abdul |last11=Hoh |first11=Boon-Peng |last12=Xu |first12=Shuhua |title=Genetic Connections and Convergent Evolution of Tropical Indigenous Peoples in Asia |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution |date=3 February 2022 |volume=39 |issue=2 |pages=msab361 |doi=10.1093/molbev/msab361 |pmid=34940850 |pmc=8826522 |quote=We hypothesize that phenotypic convergence of the dark pigmentation in TIAs could have resulted from parallel (e.g., DDB1/DAK) or genetic convergence driven by admixture (e.g., MTHFD1 and RAD18), new mutations (e.g., STK11), or notably purifying selection (e.g., MC1R).}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Endicott |first1=Phillip |last2=Gilbert |first2=M. Thomas P. |last3=Stringer |first3=Chris |last4=Lalueza-Fox |first4=Carles |last5=Willerslev |first5=Eske |last6=Hansen |first6=Anders J. |last7=Cooper |first7=Alan |title=The Genetic Origins of the Andaman Islanders |journal=The American Journal of Human Genetics |date=January 2003 |volume=72 |issue=1 |pages=178–184 |doi=10.1086/345487 |pmid=12478481 |pmc=378623 |quote=D-loop and protein-coding data reveal that phenotypic similarities with African pygmoid groups are convergent.}}</ref> | |||

| They are likely descendants of the ] populations of the ] and New Guinea, predating the ] peoples who later entered Southeast Asia.<ref name="WH_Getting_Here"></ref> | |||

| A Negrito-like population was most likely also present in ] before the Neolithic expansion and must have persisted into historical times, as suggested by evidence from morphological features of human skeletal remains dating from around 6,000 years ago resembling Negritos (especially Aetas in northern Luzon), and further corroborated by Chinese reports from the ] (1684 to 1895) and from tales of ] about people with "dark skin, short-and-small body stature, frizzy hair, and occupation in forested mountains or remote caves".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hung |first1=Hsiao-chun |last2=Matsumura |first2=Hirofumi |last3=Nguyen |first3=Lan Cuong |last4=Hanihara |first4=Tsunehiko |last5=Huang |first5=Shih-Chiang |last6=Carson |first6=Mike T. |title=Negritos in Taiwan and the wider prehistory of Southeast Asia: new discovery from the Xiaoma Caves |journal=World Archaeology |date=4 October 2022 |volume=54 |issue=2 |pages=207–228 |doi=10.1080/00438243.2022.2121315 |s2cid=252723056 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Alternatively, some scientists claim they are merely a group of Australo-Melanesians who have undergone ] over thousands of years, reducing their food intake in order to cope with limited resources and adapt to a tropical rainforest environment. Anthropologist ] in his bestselling book, '']'' suggests that the Negritos are possible ancestors of the ] and ] of ]. This assertion is echoed by Windshuttle and Gillin (2002). | |||

| A number of features would seem to suggest a common origin for the Negritos and ], especially in the ] Islanders who have been isolated from incoming waves of Asiatic and Indo-Aryan peoples. No other living human population has experienced such long-lasting isolation from contact with other groups <ref name=Thangaraj2002>{{Citation| first = Kumarasamy | last = Thangaraj| coauthors = et al.| title = Genetic Affinities of the Andaman Islanders, a Vanishing Human Population|url=http://hpgl.stanford.edu/publications/CB_2002_p1-18.pdf| journal =Current Biology | volume = 13, Number 2| pages = 86–93(8)|date=21 January 2003|year=2002}}</ref>. | |||

| These features include short stature, very dark skin, woolly hair, scant body hair and occasional ]. The claim that Andamanese pygmoids more closely resemble Africans than Asians in their cranial morphology in a 1973 study added some weight to this theory before genetic studies pointed to a closer relationship with Asians. <ref name=Thangaraj2002 /> | |||

| Other more recent studies have shown closer craniometric affinities to Egyptians and Europeans than to Sub Saharan populations such as that of African Pygmies. Walter Neves' study of the Lagoa Santa people had the incidental correlation of showing Andamanese as classifying closer to Egyptians and Europeans than any Sub Saharan population. <ref>{{Citation |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/102/51/18309/Fig. 2 |title=Fig. 2 Morphological Affinities |publisher=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |format={{dead link|date=May 2009}} }}</ref><ref>{{Citation |url=http://onedroprule.org/forum/127/nevesfinal.jpg |title=Morphological Afinities, averaging graphs A through D |publisher=onedroprule.org }}</ref> | |||

| Multiple studies also show that Negritos from Southeast Asia to New Guinea share a closer cranial affinity with ].<ref name="WH_Getting_Here"/><ref>{{Citation | |||

| |url=http://backintyme.com/admixture/bulbeck01.pdf | |||

| |title=Races of Homo sapiens: if not in the southwest Pacific, then nowhere | |||

| |author=David Bulbeck | |||

| |coauthors= Pathmanathan Raghavan and Daniel Rayner | |||

| |journal=World Archaeology | |||

| |volume=38 | |||

| |issue=1 | |||

| |pages=109–132 | |||

| year=2006 | |||

| |publisher=Taylor & Francis | |||

| |issn=0043-8243 | |||

| |doi=10.1080/00438240600564987 | |||

| |year=2006}}</ref> Further evidence for Asian ancestry is in craniometric markers such as ], shared by Asian and Negrito populations. | |||

| It has been suggested that the craniometric similarities to Asians could merely indicate a level of interbreeding between Negritos and later waves of people arriving from the Asian mainland. This hypothesis is not supported by genetic evidence that has shown the level of isolation populations such as the Andamanese have had. | |||

| However, some studies have suggested that each group should be considered separately, as the genetic evidence refutes the notion of a specific shared ancestry between the "Negrito" groups of the Andaman Islands, Malay Peninsula, and Philippines.<ref>{{Citation | |||

| |url=http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/msl124v1.pdf | |||

| |title=Phylogeography and Ethnogenesis of Aboriginal Southeast Asians | |||

| |author=Catherine Hill1 | |||

| |coauthors=Pedro Soares, Maru Mormina1, Vincent Macaulay, William Meehan, James Blackburn, Douglas Clarke, Joseph Maripa Raja, Patimah Ismail, David Bulbeck, Stephen Oppenheimer, Martin Richards | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| |year=2006 | |||

| |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution}}</ref> | |||

| While earlier studies, such as that of WW Howell, allied Andamanese craniometrically with Africans, they did not have recourse to genetic studies.<ref name="WH_Getting_Here"/> Later genetic and craniometric (mentioned earlier) studies have found more genetic affinities with Asians and Polynesians.<ref name=Thangaraj2002 /> | |||

| A study on ] and proteins in the 1950s suggested that the ] were more closely related to Oceanic peoples than Africans. Genetic studies on Philippine Negritos, based on polymorphic blood enzymes and antigens, showed they were similar to surrounding Asian populations. <ref name=Thangaraj2002 /> | |||

| Genetic testing places all the Onge and all but two of the Great Andamanese in the ] ], found in East Africa, East Asia, and South Asia, suggesting that the Negritos are at least partly descended from a migration originating in eastern Africa as much as 60,000 years ago. This migration is hypothesized to have followed a coastal route through India and into Southeast Asia, which is sometimes referred to as the ]. | |||

| Analysis of mtDNA coding sites indicated that these Andamanese fall into a subgroup of M not previously identified in human populations in Africa and Asia. These findings suggest an early split from the population of African migrants whose descendants would eventually populate the entire habitable world.<ref name=Thangaraj2002 /> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * {{annotated link|Australo-Melanesian}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{annotated link|Mbabaram people}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{annotated link|Melanesians}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| * {{EB1911|wstitle=Negritos}} | |||

| {{1911}} | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| ===References=== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| * Evans, Ivor Hugh Norman. ''The Negritos of Malaya''. Cambridge : University Press, 1937. |

* Evans, Ivor Hugh Norman. ''The Negritos of Malaya''. Cambridge : University Press, 1937. | ||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Benjamin |first1=Geoffrey |title=Why Have the Peninsular 'Negritos' Remained Distinct? |journal=Human Biology |date=June 2013 |volume=85 |issue=1–3 |pages=445–484 |doi=10.3378/027.085.0321 |pmid=24297237 |hdl=10356/106539 |s2cid=9918641 |hdl-access=free }} | |||

| * Garvan, John M., and Hermann Hochegger. ''The Negritos of the Philippines''. Wiener Beitrage zur Kulturgeschichte und Linguistik, Bd. 14. Horn: F. Berger, 1964. | |||

| * Garvan, John M., and Hermann Hochegger. ''The Negritos of the Philippines''. Wiener Beitrage zur Kulturgeschichte und Linguistik, Bd. 14. Horn: F. Berger, 1964. | |||

| * Hurst Gallery. ''Art of the Negritos''. Cambridge, Mass: Hurst Gallery, 1987. | |||

| * Hurst Gallery. ''Art of the Negritos''. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Hurst Gallery, 1987. | |||

| * Khadizan bin Abdullah, and Abdul Razak Yaacob. ''Pasir Lenggi, a Bateq Negrito Resettlement Area in Ulu Kelantan''. Pulau Pinang: Social Anthropology Section, School of Comparative Social Sciences, Universití Sains Malaysia, 1974. | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=bin Abdullah |first1=Khadizan |last2=Yaacob |first2=Abdul Razak |title=Pasir Lenggi, a Bateq Negrito resettlement area in Ulu Kelantan |date=1974 |oclc=2966355 }} | |||

| * Schebesta, P., & Schütze, F. (1970). ''The Negritos of Asia''. Human relations area files, 1-2. New Haven, Conn: Human Relations Area Files. | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Mirante |first1=Edith |title=The Wind in the Bamboo: A Journey in Search of Asia's 'Negrito' Indigenous People |date=2014 |publisher=Orchid Press Publishing Limited |isbn=978-974-524-189-3 }} | |||

| * Schebesta, P., & Schütze, F. (1970). ''The Negritos of Asia''. Human relations area files, 1–2. New Haven, Conn: Human Relations Area Files. | |||

| * ] (1996). ''Egalitarian Rituals. Rites of the Atta hunter-gatherers of Kalinga-Apayao, Philippines'', Social and Human Sciences Faculty, ]. | |||

| * Zell, Reg. ''About the Negritos: A Bibliography''. Edition blurb, 2011. | |||

| * Zell, Reg. ''Negritos of the Philippines''. The People of the Bamboo - Age - A Socio-Ecological Model. Edition blurb, 2011. | |||

| * Zell, Reg, John M. Garvan. ''An Investigation: On the Negritos of Tayabas''. Edition blurb, 2011. | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category|Negrito}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{AmCyc Poster|Negritos}} | |||

| * A detailed book written by an American at the turn of the previous century holistically describing the Negrito culture. Online document processed by | |||

| * —detailed book written by an American at the turn of the previous century holistically describing the Negrito culture | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Negritos}} | {{Negritos}} | ||

| {{Historical definitions of race}} | |||

| {{Culture of Oceania|state=autocollapse}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:41, 17 November 2024

Set of ethnic groups in Southeast Asia and Andaman islands This article is about the ethnic groups. For the shrub, see Citharexylum berlandieri. For the municipality, see El Negrito. For the bird genus, see Lessonia (bird). Not to be confused with Pygmy peoples.Ethnic group

A Luzon Negrito with spear A Luzon Negrito with spear | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Isolated geographic regions in India and Maritime Southeast Asia | |

| Languages | |

| Andamanese languages, Aslian languages, Philippine Negrito languages | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, folk religion, Anito, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism |

The term Negrito (/nɪˈɡriːtoʊ/; lit. 'little black people') refers to several diverse ethnic groups who inhabit isolated parts of Southeast Asia and the Andaman Islands. Populations often described as Negrito include: the Andamanese peoples (including the Great Andamanese, the Onge, the Jarawa, and the Sentinelese) of the Andaman Islands, the Semang peoples (among them, the Batek people) of Peninsular Malaysia, the Maniq people of Southern Thailand, as well as the Aeta of Luzon, the Ati and Tumandok of Panay, the Mamanwa of Mindanao, and about 30 other officially recognized ethnic groups in the Philippines.

Etymology

The word Negrito, the Spanish diminutive of negro, is used to mean "little black person." This usage was coined by 16th-century Spanish missionaries operating in the Philippines, and was borrowed by other European travellers and colonialists across Austronesia to label various peoples perceived as sharing relatively small physical stature and dark skin. Contemporary usage of an alternative Spanish epithet, Negrillos, also tended to bundle these peoples with the pygmy peoples of Central Africa on the basis of perceived similarities in stature and complexion. (Historically, the label Negrito has also been used to refer to African pygmies.) The appropriateness of bundling peoples of different ethnicities by similarities in stature and complexion has been called into question.

Population

There are over 100,000 Negritos in the Philippines. In 2010, there were 50,236 Aeta people in the Philippines. The Ati people 55,473 (2020 census) Officially, Malaysia had approximately 4,800 Negrito (Semangs). This number increases if we include some of the populations or individual groups among Orang Asli who have either assimilated Negrito population or have admixed origins. According to the 2006 census, the number of Orang Asli was 141,230 Andamanese of India with just c. over 500. Thailand Negrito Maniq is estimated 300, divided into several clans. Other puts it at 382 or less than 500.

Culture

Most groups designated as "Negrito" lived as hunter-gatherers, while some also used agriculture, such as plant harvesting. Today most live assimilated to the majority population of their respective homeland. Discrimination and poverty are often problems, caused either by their lower social position and/or their hunter-gatherer lifestyles.

Origins

See also: Genetic history of East Asians and Peopling of Southeast Asia

Based on perceived physical similarities, Negritos were once considered a single population of closely related people. However, genetic studies suggest that they consist of several separate groups descended from the same ancient East Eurasian meta-population that gave rise to modern East Asian peoples and Oceanian peoples, as well as displaying genetic heterogeneity. The Negritos form the indigenous population of Southeast Asia, but were largely absorbed by Austroasiatic- and Austronesian-speaking groups who migrated from southern East Asia into Mainland and Insular Southeast Asia with the Neolithic expansion. The remainders form minority groups in geographically isolated regions.

Genetic studies provided mixed evidence of modern Negrito populations, with admixtures in different. Studies indicate that Negrito populations are closer to their neighboring non-Negrito communities in their paternal heritage and overall DNA on average.

It has been found that the physical and morphological phenotypes of Negritos, such as short stature, a wide and snub nose, curly hair and dark skin, "are shaped by novel mechanisms for adaptation to tropical rainforests" through convergent evolution and positive selection, rather than a remnant of a shared common ancestor, as suggested previously by some researchers.

A Negrito-like population was most likely also present in Taiwan before the Neolithic expansion and must have persisted into historical times, as suggested by evidence from morphological features of human skeletal remains dating from around 6,000 years ago resembling Negritos (especially Aetas in northern Luzon), and further corroborated by Chinese reports from the Qing period rule of Taiwan (1684 to 1895) and from tales of Taiwanese indigenous peoples about people with "dark skin, short-and-small body stature, frizzy hair, and occupation in forested mountains or remote caves".

See also

- Australo-Melanesian – Outdated grouping of human beings

- Mbabaram people – Aboriginal Australian people of the Atherton Tableland

- Melanesians – Indigenous inhabitants of Melanesia

Notes

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Negritos". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Negritos". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

References

- ^ Manickham, Sandra Khor (2009). "Africans in Asia: The Discourse of 'Negritos' in Early Nineteenth-century Southeast Asia". In Hägerdal, Hans (ed.). Responding to the West: Essays on Colonial Domination and Asian Agency. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 69–79. ISBN 978-90-8964-093-2.

- See, for example: Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, 1910–1911: "Second are the large Negrito family, represented in Africa by the dwarf-races of the equatorial forests, the Akkas, Batwas, Wochuas and others..." (p. 851)

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) - Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- Kirk Endicott (27 November 2015). Malaysia's Original People: Past, Present and Future of the Orang Asli. Introduction. NUS Press, National University of Singapore Press. 2016, pp. 1-38. ISBN 978-9971-69-861-4. Retrieved 12 January 2019. (in English)

- "JAKOA Program". Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli (JAKOA). Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- Thonghom; Weber, George. "36. The Negrito of Thailand; The Mani". Andaman.org. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Primal Survivor: Season 5, episode 1

- "Calls for Maniq tribe to get their own patch". Bangkok Post.

- 2016 https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/special-reports/1139777/no-common-ground

- "The succesful [sic] revival of Negrito culture in the Philippines". Rutu Foundation. 6 May 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Sofwan Noerwidi (2017). "Using Dental Metrical Analysis to Determine the Terminal Pleistocene and Holocene Population History of Java". In Piper, Philip J.; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Bulbeck, David (eds.). New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory. Acton, Australian Capital Territory: ANU Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-76046-095-2.

- Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Endicott, Phillip (June 2013). "The Andaman Islanders in a Regional Genetic Context: Reexamining the Evidence for an Early Peopling of the Archipelago from South Asia". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 153–172. doi:10.3378/027.085.0307. PMID 24297224. S2CID 7774927.

- Basu, Analabha; Sarkar-Roy, Neeta; Majumder, Partha P. (2016). "Genomic reconstruction of the history of extant populations of India reveals five distinct ancestral components and a complex structure". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (6): 1594–1599. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.1594B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513197113. PMC 4760789. PMID 26811443.

- Larena, Maximilian; Sanchez-Quinto, Federico; Sjödin, Per; McKenna, James; Ebeo, Carlo; Reyes, Rebecca; Casel, Ophelia; Huang, Jin-Yuan; Hagada, Kim Pullupul; Guilay, Dennis; Reyes, Jennelyn (2021). "Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (13). e2026132118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11826132L. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118. PMC 8020671. PMID 33753512.

- Carlhoff, Selina; Duli, Akin; Nägele, Kathrin; Nur, Muhammad; Skov, Laurits; Sumantri, Iwan; Oktaviana, Adhi Agus; Hakim, Budianto; Burhan, Basran; Syahdar, Fardi Ali; McGahan, David P. (2021). "Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea". Nature. 596 (7873): 543–547. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..543C. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6. hdl:10072/407535. PMC 8387238. PMID 34433944.

- Tagore, Debashree; Aghakhanian, Farhang; Naidu, Rakesh; Phipps, Maude E.; Basu, Analabha (2021). "Insights into the demographic history of Asia from common ancestry and admixture in the genomic landscape of present-day Austroasiatic speakers". BMC Biology. 19 (1): 61. doi:10.1186/s12915-021-00981-x. PMC 8008685. PMID 33781248.

- Yang, Melinda A. (6 January 2022). "A genetic history of migration, diversification, and admixture in Asia". Human Population Genetics and Genomics: 1–32. doi:10.47248/hpgg2202010001.

- Yew, Chee-Wei; Lu, Dongsheng; Deng, Lian; Wong, Lai-Ping; Ong, Rick Twee-Hee; Lu, Yan; Wang, Xiaoji; Yunus, Yushimah; Aghakhanian, Farhang; Mokhtar, Siti Shuhada; Hoque, Mohammad Zahirul; Voo, Christopher Lok-Yung; Abdul Rahman, Thuhairah; Bhak, Jong; Phipps, Maude E.; Xu, Shuhua; Teo, Yik-Ying; Kumar, Subbiah Vijay; Hoh, Boon-Peng (February 2018). "Genomic structure of the native inhabitants of Peninsular Malaysia and North Borneo suggests complex human population history in Southeast Asia". Human Genetics. 137 (2): 161–173. doi:10.1007/s00439-018-1869-0. PMID 29383489. S2CID 253969988.

The analysis of time of divergence suggested that ancestors of Negrito were the earliest settlers in the Malay Peninsula, whom first separated from the Papuans ~ 50-33 thousand years ago (kya), followed by East Asian (~ 40-15 kya)...

- Aghakhanian, Farhang; Yunus, Yushima; et al. (14 April 2015). "Unravelling the Genetic History of Negritos and Indigenous Populations of Southeast Asia". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (5): 1206–1215. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv065. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 4453060. PMID 25877615.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- Endicott et al. 2003; Thangaraj et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2011), Y chromosome (Delfin et al. 2011; Scholes et al. 2011), and autosomal (HUGO Pan-Asia SNP Consortium 2009) studies indicate that Negrito populations are closer to their neighboring non-Negrito communities.

- Stock, Jay T. (June 2013). "The Skeletal Phenotype of 'Negritos' from the Andaman Islands and Philippines Relative to Global Variation among Hunter-Gatherers". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 67–94. doi:10.3378/027.085.0304. PMID 24297221. S2CID 32964023.

Although general similarities in size and proportions remain between the Andamanese and Aeta, differences in humero-femoral indices and arm length between these groups and the Efé demonstrate that there is not a generic 'pygmy' phenotype. Our interpretations of negrito origins and adaptation must account for this phenotypic variation.

- Zhang, Xiaoming; Liu, Qi; Zhang, Hui; Zhao, Shilei; Huang, Jiahui; Sovannary, Tuot; Bunnath, Long; Aun, Hong Seang; Samnom, Ham; Su, Bing; Chen, Hua (31 March 2022). "The distinct morphological phenotypes of Southeast Asian aborigines are shaped by novel mechanisms for adaptation to tropical rainforests". National Science Review. 9 (3): nwab072. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwab072. PMC 8970429. PMID 35371514.

- Deng, Lian; Pan, Yuwen; Wang, Yinan; Chen, Hao; Yuan, Kai; Chen, Sihan; Lu, Dongsheng; Lu, Yan; Mokhtar, Siti Shuhada; Rahman, Thuhairah Abdul; Hoh, Boon-Peng; Xu, Shuhua (3 February 2022). "Genetic Connections and Convergent Evolution of Tropical Indigenous Peoples in Asia". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 39 (2): msab361. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab361. PMC 8826522. PMID 34940850.

We hypothesize that phenotypic convergence of the dark pigmentation in TIAs could have resulted from parallel (e.g., DDB1/DAK) or genetic convergence driven by admixture (e.g., MTHFD1 and RAD18), new mutations (e.g., STK11), or notably purifying selection (e.g., MC1R).

- Endicott, Phillip; Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Stringer, Chris; Lalueza-Fox, Carles; Willerslev, Eske; Hansen, Anders J.; Cooper, Alan (January 2003). "The Genetic Origins of the Andaman Islanders". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (1): 178–184. doi:10.1086/345487. PMC 378623. PMID 12478481.

D-loop and protein-coding data reveal that phenotypic similarities with African pygmoid groups are convergent.

- Hung, Hsiao-chun; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Nguyen, Lan Cuong; Hanihara, Tsunehiko; Huang, Shih-Chiang; Carson, Mike T. (4 October 2022). "Negritos in Taiwan and the wider prehistory of Southeast Asia: new discovery from the Xiaoma Caves". World Archaeology. 54 (2): 207–228. doi:10.1080/00438243.2022.2121315. S2CID 252723056.

Further reading

- Evans, Ivor Hugh Norman. The Negritos of Malaya. Cambridge : University Press, 1937.

- Benjamin, Geoffrey (June 2013). "Why Have the Peninsular 'Negritos' Remained Distinct?". Human Biology. 85 (1–3): 445–484. doi:10.3378/027.085.0321. hdl:10356/106539. PMID 24297237. S2CID 9918641.

- Garvan, John M., and Hermann Hochegger. The Negritos of the Philippines. Wiener Beitrage zur Kulturgeschichte und Linguistik, Bd. 14. Horn: F. Berger, 1964.

- Hurst Gallery. Art of the Negritos. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Hurst Gallery, 1987.

- bin Abdullah, Khadizan; Yaacob, Abdul Razak (1974). Pasir Lenggi, a Bateq Negrito resettlement area in Ulu Kelantan. OCLC 2966355.

- Mirante, Edith (2014). The Wind in the Bamboo: A Journey in Search of Asia's 'Negrito' Indigenous People. Orchid Press Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-974-524-189-3.

- Schebesta, P., & Schütze, F. (1970). The Negritos of Asia. Human relations area files, 1–2. New Haven, Conn: Human Relations Area Files.

- Armando Marques Guedes (1996). Egalitarian Rituals. Rites of the Atta hunter-gatherers of Kalinga-Apayao, Philippines, Social and Human Sciences Faculty, Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

- Zell, Reg. About the Negritos: A Bibliography. Edition blurb, 2011.

- Zell, Reg. Negritos of the Philippines. The People of the Bamboo - Age - A Socio-Ecological Model. Edition blurb, 2011.

- Zell, Reg, John M. Garvan. An Investigation: On the Negritos of Tayabas. Edition blurb, 2011.

External links

- Negritos of Zambales—detailed book written by an American at the turn of the previous century holistically describing the Negrito culture

- Andaman.org: The Negrito of Thailand

- The Southeast Asian Negrito

| Negritos | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Andaman Islands |

| ||

| Malaysia | |||

| Philippines | |||

| Thailand | |||

| Italics indicate extinct groups | |||