| Revision as of 01:32, 2 August 2009 view sourceSaroshp (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,115 edits This box should reflect the territorial changes that resulting from this conflict anything that happened in the future is out of scope of the 1947 War - look up wiki rules← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:30, 12 December 2024 view source Kautilya3 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers86,407 edits Reverted 1 edit by VirtualVagabond (talk): Unsourced editTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| (999 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1947–1948 war between India and Pakistan}} | |||

| {{fixbunching|beg}} | |||

| {{pp-extended|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Warbox | |||

| {{Use British English|date=March 2013}} | |||

| |conflict=Indo-Pakistani War of 1948 | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2022}} | |||

| |partof=the ] | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |campaign= | |||

| | conflict = Indo-Pakistani war of 1947–1948 | |||

| |colour_scheme=background:#91ACDB | |||

| | partof = the ], ], and the ] | |||

| |image= | |||

| | campaign = | |||

| |caption= | |||

| | colour_scheme = background:#91ACDA | |||

| |casus=Pakistan-backed ] tribals and later Army regulars invade the princely state of ]. | |||

| | image = ] | |||

| |date=], ] - ], ] | |||

| | caption = ] soldiers during the 1947–1948 war | |||

| |place=] | |||

| | notes = Conflict began when ] tribesmen and Tanoli from Pakistan invaded the ] of ], prompting the armies of India and Pakistan to get involved shortly afterwards. | |||

| |result=Ceasefire arranged by ] pending plebiscite. Princely state of ] dissolved. Pakistan takes control of roughly a third of Kashmir- the north-western scrublands, whereas India takes control of the Kashmir valley and most of Jammu. | |||

| | date = October 1947 – 1 January 1949 <br>(1 year and 10 weeks) | |||

| |territory=] divides erstwhile princely state of Kashmir and Jammu between the India state of ] (roughly 101,387 km²) and the Pakistan regions which subsequently became ] (13,297 km²) and the ] (72,496 km²). | |||

| | place = ] | |||

| |combatant1=<center>{{flagicon|India|size=65px}}<br>] | |||

| | result = See ] section | |||

| |combatant2=<center>{{flagicon|Pakistan|size=65px}}<br>] | |||

| | territory = One-third of ] controlled by Pakistan. Indian control over remainder.<ref>{{cite book | last1=Ciment | first1=J. | last2=Hill | first2=K. | title=Encyclopedia of Conflicts since World War II | publisher=Taylor & Francis | issue=v. 1 | year=2012 | isbn=978-1-136-59614-8 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uox4CAAAQBAJ | quote=Indian forces won control of most of Kashmir | page=721}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/in_depth/south_asia/2002/india_pakistan/timeline/1947_48.stm |title=BBC on the 1947–48 war |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150130232421/http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/in_depth/south_asia/2002/india_pakistan/timeline/1947_48.stm |archive-date=30 January 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |commander1={{flagicon|India}} Field Marshal ] <br/>{{flagicon|India}} Lt Gen ] <br/>{{flagicon|India}} Maj Gen ] <br/>{{flagicon|India}} Maj Gen ] | |||

| | |

| combatant1 = {{nowrap|{{flagicon|India}} ]}} | ||

| * {{army|India}} | |||

| |strength1= | |||

| * {{air force|India}}<ref name = iaf1>{{Cite book|last=Kumar|first=Bharat|url=https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/10682697|title=An incredible war: Indian Air Force in Kashmir War 1947–1948|date=2014|publisher=KW Publishers in association with Centre for Air Power Studies|isbn=978-93-81904-52-7|edition=2nd|location=New Delhi|archive-date=6 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230206113306/https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/10682697|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Massey|2005|p=97}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Barua|2005|p=192}}</ref> | |||

| |strength2= | |||

| * ] ] | |||

| |casualties1=1,104 killed<ref name=lsqh>. It is believed that this figure only gives the Indian Army casualties and not the State Forces.</ref>(Indian army) | |||

| | combatant2 = {{flagicon|Pakistan|1947}} ] | |||

| 684 killed (State Forces)<ref name=iajak></ref> | |||

| * {{army|Pakistan}} | |||

| <ref name=iajkm></ref> | |||

| * {{air force|Pakistan}} (Supply support only) | |||

| <br>3,152 wounded <ref name=lsqh /> | |||

| * {{flagicon image|Flag of the Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee.svg}} Pakistani paramilitaries | |||

| |casualties2=1,500 killed<ref name=loc.gov></ref> (Pakistan army) <br/> | |||

| ** ]<ref name=Bangash>{{harvnb|Bangash, Three Forgotten Accessions|2010}}</ref><ref name=Khanna>{{cite book |last=Khanna |first=K. K. |title=Art of Generalship |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAmqCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA158 |date=2015 |publisher=Vij Books India Pvt Ltd |isbn=978-93-82652-93-9 |page=158 }}</ref> | |||

| 2,633 killed, 4,668 wounded<ref name=pakdef48></ref> | |||

| ** ]{{sfn|Jamal, Shadow War|2009|p=57}} | |||

| ** ]{{sfn|Jamal, Shadow War|2009|p=57}} | |||

| ** ]<ref name="(Editor)">{{cite book |editor1=Nicholas Burns |editor2=Jonathon Price |title=American Interests in South Asia: Building a Grand Strategy in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India |year=2011 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ENyfHXi9wz0C&pg=PT155 |publisher=Aspen Institute |isbn=978-1-61792-400-2 |pages=155– }}</ref> | |||

| * {{flagicon|Azad Kashmir}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon image|1931 Flag of India.svg}} ]<ref>{{cite book | last=Lamb | first=A. | title=Incomplete Partition: The Genesis of the Kashmir Dispute, 1947-1948 | publisher=Oxford University Press | year=2002| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Vi9WAAAAYAAJ| page=141| isbn=978-0-19-579770-1 }}</ref> | |||

| * {{flagicon image|Flag of Muslim League.svg}} ]{{sfn|Jamal, Shadow War|2009|p=49}} | |||

| * ] ]{{sfn|Jamal, Shadow War|2009|p=57}} | |||

| * ] ]<ref name="Simon Ross Valentine">{{cite book |title=Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at: History, Belief, Practice |publisher=Hurst Publishers |isbn=978-1-85065-916-7 |page=204 |first=Simon Ross |last=Valentine |date=2008 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MdRth02Q6nAC&q=furqan+force&pg=PA204 }}</ref><ref name="Furqan Force">{{cite web |title=Furqan Force |url=https://www.thepersecution.org/50years/kashmir.html#2a |publisher=Persecution.org |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120602121459/http://www.thepersecution.org/50years/kashmir.html#2a |archive-date=2 June 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | commander1 = {{nowrap|{{flagicon image|Flag of the Governor-General of India (1947–1950).svg}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|India}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|British India|army}} ]<ref name=Dasgupta>{{harvnb|Dasgupta, War and Diplomacy in Kashmir|2014}}</ref><br /> {{flagicon|British India|army}} ]<ref name=Dasgupta /><br /> {{flagicon|India|army}} ]<ref name=Dasgupta /><br /> ] ]<br /> ] ]<br /> ] ]}} | |||

| | commander2 = {{nowrap|{{flagicon image|Flag of the Governor-General of Pakistan (1947-1953).svg}} ]<br /> {{flagicon image|Flag of the Prime Minister of Pakistan.svg}} ]<br />{{flagicon|British India|army}} ]<ref name=Dasgupta /><br /> {{flagicon|British India|army}} ]<ref name=Dasgupta /><br /> {{flagicon|Pakistan|army}} ] ]<ref name="Nawaz">{{harvnb|Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited|2008}}</ref><br /> {{flagicon|Pakistan}} ]{{sfn|Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited|2008|p=120}}<br /> {{flagicon|Pakistan}} ]{{sfn|Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited|2008|p=120}}<br /> {{flagicon|Pakistan}} ]<ref name=Bangash />}} | |||

| | strength1 = | |||

| | strength2 = | |||

| | casualties1 = 1,103 army deaths<ref name="Prasad">{{cite book |last1=Prasad |first1=Sri Nandan |last2=Pal |first2=Dharm |title=Operations in Jammu & Kashmir, 1947–48 |url=https://ia801505.us.archive.org/34/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.116302/2015.116302.Operations-In-Jammu-Amp-Kashmir-1947-48.pdf |year=1987 |publisher=History Division, Ministry of Defence, Government of India |page=379 |quotation=During the long campaign, the Indian Army lost 76 officers, 31 JCOs and 996 Other Ranks killed, making a total of 1103. The wounded totalled 3152, including 81 officers and 107 JCOs. Apart from these casualties, it appears that the J & K State Forces lost no less than 1990 officers and men killed, died of wounds, or missing presumed killed. The small RIAF lost a total of 32 officers and men who laid down their lives for the nation during these operations. In this roll of honour, there were no less than 9 officers.}}</ref><ref name="Kargil from Surprise to Victory">{{Cite book |title=Kargil from Surprise to Victory |last=Malik |first=V. P. |publisher=HarperCollins Publishers India |year=2010 |isbn=9789350293133 |edition=paperback |page=343}}</ref><ref>"An incredible war: Indian Air Force in Kashmir war, 1947–48", by Bharat Kumar, Centre for Air Power Studies (New Delhi, India)</ref><ref name="Roy">{{cite book | last=Roy | first=Kaushik | title=The Oxford Companion to Modern Warfare in India: From the Eighteenth Century to Present Times | publisher=Oxford University Press | year=2009 | isbn=978-0-19-569888-6 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ioUpAQAAIAAJ | access-date=2022-05-18 | page=215 | archive-date=18 May 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220518163641/https://books.google.com/books?id=ioUpAQAAIAAJ | url-status=live }}</ref><br/>1,990 J&K forces killed or missing presumed killed<ref name="Prasad"/><br/> 32 RIAF members<ref name="Prasad"/> <br />3,154 wounded<ref name="Kargil from Surprise to Victory" /><ref name="Honor and Glory">{{cite book |last=Singh |first=Maj Gen Jagjit |title=With Honour & Glory: Wars fought by India 1947–1999 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bljFNwAACAAJ |year=2000 |publisher=Lancer Publishers |isbn=978-81-7062-109-6 |pages=18– }}</ref> <br /><br />'''Total military casualties:'''<br />6,279 | |||

| | casualties2 = 6,000 killed<ref name="Honor and Glory" /><ref>{{cite web |author=Sabir Sha |title=Indian military hysteria since 1947 |newspaper=The News International |url=https://www.thenews.com.pk/Todays-News-13-33393-Indian-military-hysteria-since-1947 |date=10 October 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151117023543/http://www.thenews.com.pk/Todays-News-13-33393-Indian-military-hysteria-since-1947 |archive-date=17 November 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Krishna1998">{{cite book |last=Krishna |first=Ashok |title=India's Armed Forces: Fifty Years of War and Peace |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wGIkXCsgT2UC&pg=PA160 |year=1998 |publisher=Lancer Publishers |isbn=978-1-897829-47-9 |pages=160– }}</ref><br />~14,000 wounded<ref name="Honor and Glory" /><ref>By B. Chakravorty, "Stories of Heroism, Volume 1", p. 5</ref><br /><br />'''Total military casualties:'''<br />20,000 | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Indo-Pakistani Wars}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{fixbunching|mid}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Indo-Pakistani Wars}} | |||

| {{fixbunching|end}} | |||

| The '''Indo-Pakistani War of 1947''', sometimes known as the '''First Kashmir War''', was fought between ] and ] over the region of ] from ] to ]. It was the first of ] fought between the two ]. The result of the war still affects the geopolitics of both the countries. | |||

| The '''Indo-Pakistani war of 1947–1948''', also known as the '''first Kashmir war''',<ref>{{citation |first=Shuja |last=Nawaz |title=The First Kashmir War Revisited |journal=India Review |volume=7 |number=2 |pages=115–154 |doi=10.1080/14736480802055455 |date=May 2008 |s2cid=155030407 |issn = 1473-6489 }}</ref> was a war fought between ] and ] over the ] of ] from 1947 to 1948. It was the first of four ] between the two ]. Pakistan precipitated the war a few weeks after its independence by launching tribal '']'' (militias) from ],<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.princeton.edu/~jns/publications/Understanding%20Support%20for%20Islamist%20Militancy.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140912114721/http://www.princeton.edu/~jns/publications/Understanding%20Support%20for%20Islamist%20Militancy.pdf |url-status=dead |title=Pakistan Covert Operations |archive-date=12 September 2014}}</ref> in an effort to capture ] and to preempt the possibility of its ruler joining India.{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|pp=31, 34–35, 105}} | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| Prior to 1815 the area now known as "Kashmir" was referred to as the "Panjab Hill States" and comprised 22 small independent states. These small states were ruled by ] who had sworn allegiance to the Mughal empire. In fact the Rajput of the Punjab Hill States were a major strength of the ] and had fought many battles in support of the Mughals especially against the Sikhs. Following the rise of the ] and the subsequent decline of the Mughal empire, the power of the Panjab Hill States also began to decline. They therefore became easy targets for the Sikh leader ] who proceeded to conquer these small states one by one. Eventually all the Panjab Hill States were conquered by Ranjit Singh and merged into one state to be called the State of Jammu. | |||

| ], the ] of Jammu and Kashmir, was facing an ] in ], and lost control in portions of the western districts. On 22 October 1947, Pakistan's ] crossed the border of the state. These local tribal militias and irregular Pakistani forces moved to take the capital city of ], but upon reaching ], they took to plunder and stalled. Maharaja Hari Singh made a plea to India for assistance, and help was offered, but it was subject to his signing of an ] to India. | |||

| History of Panjab castes by J. Hutchinson and J.P.Vogel lists a total of 22 states 16 Hindu and 6 Muhammadan that formed the State of Jammu following the conquest of Raja Ranjit Singh in 1820. Of these 6 Muhammadan States two (Kotli and Punch) were ruled by Mangrals, two (Bhimber and Khari-Khariyala) by Chibs one (Rajouri) by the Jarrals and one (Khashtwar) by the Khashtwaria. <ref></ref> | |||

| The war was initially fought by the ]{{sfn |Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict|2003|p=80}}<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vLwOck15eboC&pg=PA80 |title=Conflict Between India and Pakistan: An Encyclopedia |last=Lyon |first=Peter |date=1 January 2008 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-57607-712-2 |pages=80 |language=en}}</ref> and by militias from the ] adjoining the ].<ref name=britannica> {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150430073828/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/312908/Kashmir/214223/The-Kashmir-problem#ref673547 |date=30 April 2015 }} in '']'' (2011), online edition</ref> Following the ] on 26 October 1947, Indian troops were airlifted to ], the state capital. British commanding officers initially refused the entry of Pakistani troops into the conflict, citing the accession of the state to India. However, later in 1948, they relented and Pakistan's armies entered the war shortly afterwards.<ref name=britannica /> The fronts solidified gradually along what later came to be known as the ]. A formal ceasefire was declared effective 1 January 1949.{{sfn|Prasad & Pal, Operations in Jammu & Kashmir |1987|p=371}} Numerous analysts state that the war ended in a stalemate, with neither side obtaining a clear victory. Others, however, state that India emerged victorious as it successfully gained the majority of the contested territory. | |||

| The ] was fought between the ], which asserted ] over Kashmir, and the East India Company between 1845 and 1846. In the ] in 1846, the Sikhs were made to surrender the valuable region (the Jullundur Doab) between the ] and ] and required to pay an indemnity of 1.2 million rupees. | |||

| == Background == | |||

| Because they could not readily raise this sum, the East India Company allowed the ] ruler ] to acquire ] from the Sikh kingdom in exchange for making a payment of 750,000 rupees to the East India Company. ] became the first ] of the newly formed ] of ],<ref> www.collectbritain.co.uk.</ref> founding a ], ], that was to rule the state, the second-largest principality during the ], until India gained its independence in 1947. | |||

| {{Further|History of Kashmir|Jammu and Kashmir (princely state)}} | |||

| Prior to 1815, the area now known as "Jammu and Kashmir" comprised 22 small independent states (16 Hindu and six Muslim) carved out of territories controlled by the Amir (King) of ], combined with those of local small rulers. These were collectively referred to as the "Punjab Hill States". These small states, ruled by ], were variously independent, vassals of the ] since the time of ] or sometimes controlled from ] in the Himachal area. Following the decline of the Mughals, turbulence in Kangra and invasions of Gorkhas, the hill states fell successively under the control of the Sikhs under ].<ref name="HutchisonVogel1933">{{cite book|last1=Hutchison|first1=J.|last2=Vogel|first2=Jean Philippe|title=History of the Panjab Hill States|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5uXgQwAACAAJ|year=1933|publisher=Superint., Gov. Print., Punjab}}</ref>{{rp|536}} | |||

| The ] (1845–46) was fought between the ], which asserted sovereignty over ], and the ]. In the ] of 1846, the Sikhs were made to surrender the valuable region (the Jullundur Doab) between the ] and the ] and required to pay an indemnity of 1.2 million rupees. Because they could not readily raise this sum, the East India Company allowed the ] ruler ] to acquire Kashmir from the Sikh kingdom in exchange for making a payment of 750,000 rupees to the company. Gulab Singh became the first ] of the newly formed ] of ], founding a ] that was to rule the state, the second-largest principality during the ], until India gained its independence in 1947.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| === Partition of India === | |||

| {{Seealso|Kashmir conflict}} | |||

| ] October 27 1947 cover depicting the partition of India. The caption says: ''"INDIA: Liberty and death."'']] | |||

| Before and after the withdrawal of the ] from India in ], the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu came under pressure from both India and Pakistan to agree to accede to one of the newly independent countries. According to the instruments of accession relating to the ], the rulers of ]s were to be given the choice of acceding to either India or Pakistan. The ] of Kashmir, ], however, wanted to remain an independent ] and tried to avoid accession to either country. When British forces withdrew the state was invaded by ] tribals from the ] (NWFP). | |||

| == Partition of India == | |||

| Fearing that his forces would be unable to withstand the assault, the Maharaja asked for Indian military assistance. India set a condition that Kashmir must accede to India for it to receive assistance. Whereupon the ] recognized the accession of the erstwhile princely state to India, and was considered the new Indian state of ], Indian troops were sent to the state to defend it against the Pakistani forces. The legitimacy of this accession is still disputed. Due to a lack of demographic data concerning religious affiliations, it is difficult to determine whether public opinion was a factor in Hari Singh's decision. | |||

| ] | |||

| ], Supreme Commander of Indian and Pakistani armed forces]] | |||

| {{Main|Partition of India}} | |||

| The years 1946–1947 saw the rise of ] and ], demanding a separate state for India's Muslims. The demand took a violent turn on the ] (16 August 1946) and inter-communal violence between Hindus and Muslims became endemic. Consequently, a decision was taken on 3 June 1947 to divide ] into two separate states, the ] comprising the Muslim majority areas and the ] comprising the rest. The two provinces ] and ] with large Muslim-majority areas were to be divided between the two dominions. An estimated 11 million people eventually migrated between the two parts of Punjab, and possibly 1 million perished in the inter-communal violence.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} Jammu and Kashmir, being adjacent to the Punjab province, was directly affected by the happenings in Punjab.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| Pakistan was of the view that the Maharaja of Kashmir had no right to call in the Indian Army, because it held that the Maharaja of Kashmir was not a heredity ruler, that he was merely a British appointee. There had been no such position as the "Maharaja of Kashmir" prior to British rule. Hence Pakistan decided to take action, but British-appointed Army Chief of Pakistan ] did not send troops to the Kashmir front and refused to obey the order to do so given by ], ]. Gracey's argument was that Indian forces occupying Kashmir represented the British Crown and hence he could not engage in a military encounter with Indian forces. Pakistan finally did manage to send troops to Kashmir but by then the Indian forces had taken control of approximately two thirds of the former principality. | |||

| The original target date for the transfer of power to the new dominions was June 1948. However, fearing the rise of inter-communal violence, the British Viceroy ] advanced the date to 15 August 1947. This gave only six weeks to complete all the arrangements for partition.{{sfn|Hodson, The Great Divide|1969|pp=293, 320}} Mountbatten's original plan was to stay on as the joint ] for both of the new ]s till June 1948. However, this was not accepted by the Pakistani leader ]. In the event, Mountbatten stayed on as the Governor General of India, whereas Pakistan chose Jinnah as its Governor General.{{sfn|Hodson, The Great Divide|1969|pp=293, 329–330}} It was envisaged that the nationalisation of ] could not be completed by 15 August{{efn|At the beginning of 1947, all the posts above the rank of lieutenant colonel in the army were held by British officers.{{sfn|Sarila, The Shadow of the Great Game|2007|p=324}} Pakistan had only four lieutenant colonels,{{sfn|Barua, Gentlemen of the Raj|2003|p=133}} two of whom were involved in the Kashmir conflict: Akbar Khan and Sher Khan.{{sfn|Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited|2008}} At the beginning of the war, India had about 500 British officers and Pakistan over 1000.{{sfn|Ankit, Kashmir, 1945–66|2014|p=43}}}} and hence British officers stayed on after the transfer of power. The service chiefs were appointed by the Dominion governments and were responsible to them. The overall administrative control, but not operational control, was vested with Field Marshal ],{{Efn|Auchinleck was an Indian Army officer since 1903 who had been ] from 1943}} who was titled the 'Supreme Commander', answerable to a newly formed Joint Defence Council of the two dominions. India appointed General ] as its Army chief and Pakistan appointed General ].{{sfn|Hodson, The Great Divide|1969|pp=262–265}} | |||

| ==Summary of war== | |||

| The war was fought within the borders of the former princely state of Kashmir and Jammu by ], ] and the erstwhile princely state forces opposed by ], paramilitary and local militias from the NWFP (the Pakistani forces referred to themselves as the ] forces (''Azad'' in ] means liberated or free)). The princely state forces were unprepared for the initial assault of AZK forces, having been deployed thinly on the borders of the princely state for purposes of maintaining border security and deterring militant activity.{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} The princely state defenses quickly collapsed in the face of the assault, some individuals and units joining the AZK forces. | |||

| The presence of the British commanding officers on both sides made the Indo-Pakistani war of 1947 a strange war. The two commanding officers were in daily telephone contact and adopted mutually defensive positions. The attitude was that "you can hit them so hard but not too hard, otherwise there will be all kinds of repercussions."{{sfn|Ankit, Kashmir, 1945–66|2014|pp=54, 56}} Both Lockhart and Messervy were replaced in the course of war, and their successors ] and ] tried to exercise restraint on their respective governments. Bucher was apparently successful in doing so in India, but Gracey yielded and let British officers be used in operational roles on the side of Pakistan. One British officer even died in action.{{sfn|Ankit, Kashmir, 1945–66|2014|pp=57–58}} | |||

| The initial successes by AZK forces were not vigorously pressed, giving an opportunity for India to airlift its forces into Kashmir after the state had acceded to India..{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} With Indian reinforcements opposing AZK forces, the offensive ran out of steam towards the end of 1947, except in the High Himalayas sector where AZK forces made substantial progress until they were turned back at the outskirts of ] in late June 1948. Throughout 1948 many small-scale battles were fought, but none gave a strategic advantage to either side and the fronts gradually solidified along what would became known as the ]. A formal cease-fire was declared on ] ]. | |||

| == Developments in Jammu and Kashmir (August–October 1947) == | |||

| ==Stages of the war== | |||

| ] of ] in military uniform]] | |||

| This war has been split into ten stages by time.<!-- by who? --> The individual stages are detailed below. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ===Initial invasion (Operation ])=== | |||

| ] ] – ] ] (Operation Gulmarg)]]<br> | |||

| The objective of the initial invasion was to capture control of the Kashmir valley including its principal city, ], the summer capital of the state (] being the winter capital). The state forces stationed in the border regions around ] and ] were quickly defeated by AZK forces (some state forces mutinied and joined the AZK) and the way to the capital was open. Rather than advancing toward Srinagar before state forces could regroup or be reinforced, the invading forces remained in the captured cities in the border region engaging in looting and other crimes against their inhabitants.<ref> Air Combat Information Group ], ]</ref> In the ], the state forces retreated into towns where they were besieged. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ] ] – ] ]]]<br> | |||

| With the independence of the Dominions, the ] over the princely states came to an end. The rulers of the states were advised to join one of the two dominions by executing an ]. ] of Jammu and Kashmir, along with his prime minister ], decided not to accede to either dominion. The reasons cited were that the Muslim majority population of the state would not be comfortable with joining India, and that the Hindu and Sikh minorities would become vulnerable if the state joined Pakistan.{{sfn|Ankit, Henry Scott|2010|p=45}} | |||

| ===Indian defence of the Kashmir Valley=== | |||

| After the accession, India airlifted troops and equipment to Srinagar, where they reinforced the princely state forces, established a defense perimeter and defeated the AZK forces on the outskirts of the city. The successful defence included an outflanking manoeuvre by Indian ]s. The defeated AZK forces were pursued as far as ] and ] and these towns were recaptured. | |||

| In 1947, the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir had a wide range of ethnic and religious communities. The ] consisting of the ] and the ] had a majority Muslim population (over 90%). The ], consisting of five districts, had roughly equal numbers of Hindus and Muslims in the eastern districts (], ] and ]), and a Muslim majority in the western districts (] and ]). The mountainous ] district (''wazarat'') in the east had a significant Buddhist presence with a Muslim majority in ]. The ] in the north was overwhelmingly Muslim and was directly governed by the British under an agreement with the Maharaja. Shortly before the transfer of power, the British returned the Gilgit Agency to the Maharaja, who appointed a ] governor for the district and a British commander for the local forces.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| In the Punch valley, AZK forces continued to besiege state forces. | |||

| The predominant political movement in the Kashmir Valley, the ] led by ], believed in secular politics. It was allied with the ] and was believed to favour joining India. On the other hand, the Muslims of the Jammu province supported the ], which was allied to the ] and favoured joining Pakistan. The Hindus of the Jammu province favoured an outright merger with India.<ref>{{citation |first=Balraj |last=Puri |author-link=Balraj Puri |title=The Question of Accession |journal=Epilogue |volume=4 |number=11 |pages=4–6 |date=November 2010 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TMxJzb7N_8wC&pg=PA4 |ref={{sfnref|Puri, The Question of Accession|2010}} |archive-date=17 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230117135717/https://books.google.com/books?id=TMxJzb7N_8wC&pg=PA4 }}</ref> In the midst of all the diverging views, the Maharaja's decision to remain independent was apparently a judicious one.{{sfn|Ankit, Henry Scott|2010}} | |||

| In ], the state paramilitary forces (the Gilgit Scouts) joined the invading AZK forces, who thereby obtained control of this northern region of the state. The AZK forces were also joined by troops from ], whose ruler, the Mehtar of Chitral, had acceded to Pakistan. | |||

| {{ |

{{clear left}} | ||

| === Operation Gulmarg plan === | |||

| ] ] – ] ]]]<br> | |||

| {{Location map+ | |||

| ===Attempted link-up at Punch and fall of Mirpur=== | |||

| |Pakistan | |||

| Indian forces ceased pursuit of AZK forces after recapturing Uri and Baramula, and sent a ] southwards, in an attempt to relieve Punch. Although the relief column eventually reached Punch, the siege could not be lifted. A second relief column reached ], but was forced to evacuate its garrison. | |||

| |float = right | |||

| |width = 250 | |||

| |caption = Operation Gulmarg locations | |||

| |nodiv = 1 | |||

| |mini = 1 | |||

| |places = | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=34.36|N |long=73.47|E |label=Muzaffarabad |position=right |link=Muzaffarabad |mark=Blue pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=70}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=33.76|N |long=74.09|E |label=Poonch |position=right |link=Poonch (town) |mark=Blue pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=70}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=32.98|N |long=74.07|E |label=Bhimber |position=right |link=Bhimber |mark=Blue pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=70}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=34.18|N |long=73.24|E |label=Abbottabad |position=left |link=Abbottabad |mark=Red pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=0}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=34.75|N |long=72.35|E |label=Swat |position=left |link=Swat (princely state) |mark=Green pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=0}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=35.20|N |long=71.88|E |label=Dir |position=left |link=Dir (princely state) |mark=Green pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=0}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=35.85|N |long=71.79|E |label=Chitral |position=left |link=Chitral (princely state) |mark=Green pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=0}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=32.94|N |long=70.61|E |label=Bannu |position=right |link=Bannu |mark=Red pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=0}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=32.29|N |long=69.57|E |label=Wanna |position=right |link=Wanna, Pakistan |mark=Red pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=0}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=33.58|N |long=71.42|E |label=Kohat |position=right |link=Kohat |Red=Red pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=0}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=33.37|N |long=70.55|E |label=Thall |position=right |link=Thall |mark=Red pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=0}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=34.01|N |long=71.98|E |label=Nowshera |position=right |link=Nowshera, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |mark=Red pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=0}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=35.507284|N |long=73.35631334|E |label=Indus river |position=right |link=Indus River |mark=Blue pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=70}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=31.712541|N |long=74.456148|E |label=Ravi river |position=river |link=Ravi River |mark=Blue pog.svg |marksize=4 |label_size=70}} | |||

| }} | |||

| According to Indian military sources, the Pakistani Army prepared a plan called Operation Gulmarg and put it into action as early as 20 August, a few days after Pakistan's independence. The plan was accidentally revealed to an Indian officer, ] serving with the ].{{efn|Major Kalkat was the ] at the ], who opened a Demi-Official letter marked "Personal/Top Secret" on 20 August 1947 signed by General ], the then Commander in Chief of the Pakistan Army. It was addressed to Kalkat's commanding officer Brig. C. P. Murray, who happened to be away at another post. The Pakistani officials suspected Kalkat and placed him under house arrest. He escaped and made his way to New Delhi on 18 October. However, the Indian military authorities and defence minister did not believe his information. He was recalled and debriefed on 24 October after the tribal invasion of Kashmir had started.{{sfn|Prasad & Pal, Operations in Jammu & Kashmir |1987 |p=17}}}} According to the plan, 20 ''lashkars'' (tribal militias), each consisting of 1,000 ], were to be recruited from among various Pashtun tribes, and armed at the brigade headquarters at ], ], ], ], ] and ] by the first week of September. They were expected to reach the launching point of ] on 18 October, and cross into Jammu and Kashmir on 22 October. Ten ''lashkars'' were expected to attack the ] through ] and another ten ''lashkars'' were expected to join the rebels in ], ] and ] with a view to advance to ]. Detailed arrangements for the military leadership and armaments were described in the plan.{{sfn|Prasad & Pal, Operations in Jammu & Kashmir |1987 |pp=17–19}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Kalkat |first=Onkar S. |title=The Far-flung Frontiers |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EWO5AAAAIAAJ |publisher=Allied Publishers |year=1983 |pages=40–42}}</ref> | |||

| Meanwhile, ] was captured by AZK forces on the 25th of November 1947. Then there was a massacre of Hindus and Sikhs and loot, and more later in Alibeg camp.<ref></ref> Around 20 thousand people reported killed, also atrocities on women were reported.<ref> </ref> | |||

| The regimental records show that, by the last week of August, the ] (PAVO Cavalry) regiment was briefed about the invasion plan. Colonel Sher Khan, the Director of Military Intelligence, was in charge of the briefing, along with Colonels Akbar Khan and Khanzadah. The Cavalry regiment was tasked with procuring arms and ammunition for the 'freedom fighters' and establishing three wings of the insurgent forces: the South Wing commanded by General ], a Central Wing based at Rawalpindi and a North Wing based at Abbottabad. By 1 October, the Cavalry regiment completed the task of arming the insurgent forces. "Throughout the war there was no shortage of small arms, ammunitions, or explosives at any time." The regiment was also told to be on stand by for induction into fighting at an appropriate time.{{sfnp|Effendi, Punjab Cavalry|2007|pp=151–153}}{{sfnp|Joshi, Kashmir, 1947–1965: A Story Retold|2008|p=59–}}<ref name="Wajahat review">{{citation |last=Amin |first=Agha Humayun |chapter=Memories of a Soldier by Major General Syed Wajahat Hussain (Book Review) |title=Pakistan Military Review, Volume 18 |date=August 2015 |isbn=978-1-5168-5023-5 |publisher=CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform |chapter-url=https://www.slideshare.net/AAmin1/pakistan-military-review-volume-18-inside-waziristan |access-date=17 April 2018 |archive-date=8 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308155722/https://www.slideshare.net/AAmin1/pakistan-military-review-volume-18-inside-waziristan |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ] ] - ] ]]]<br> | |||

| Scholars have noted considerable movement of Pashtun tribes during September–October. By 13 September, armed Pashtuns drifted into Lahore and Rawalpindi. The Deputy Commissioner of ] noted a scheme to send tribesmen from ] to ], in lorries provided by the Pakistan government. Preparations for attacking Kashmir were also noted in the princely states of ], ], and ]. Scholar Robin James Moore states there is "little doubt" that Pashtuns were involved in border raids all along the Punjab border from the ] to the ].{{sfn|Moore, Making the new Commonwealth|1987|p=49}} | |||

| ===Fall of Jhanger and attacks on Naoshera and Uri=== | |||

| The Pakistani/AZK forces attacked and captured Jhanger. They then attacked Naoshera unsuccessfully. Other Pakistani/AZK forces made a series of unsuccessful attacks on Uri. In the south a minor Indian attack secured Chamb. By this stage of the war the front line began to stabilise as more Indian troops became available. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ] ] - ] ]]]<br> | |||

| ===Operation Vijay: counterattack to Jhanger=== | |||

| The Indian forces launched a counterattack in the south recapturing Jhanger and Rajauri. In the Kashmir Valley the Pakistani/AZK forces continued attacking the Uri ]. In the north Skardu was brought under siege by Pakistani/AZK forces. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ] ] - ] ]]]<br> | |||

| ===Indian Spring Offensive=== | |||

| The Indians held onto Jhanger against numerous counterattacks from the AZK, who were increasingly supported by regular Pakistani Forces. In the Kashmir Valley the Indians attacked, recapturing Tithwail. The AZK made good progress in the High Himalayas sector, infiltrating troops to bring ] under siege, capturing ] and defeating a relief column heading for Skardu. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ] ] - ] ]]]<br> | |||

| ===Operations Gulab and Erase=== | |||

| The Indians continued to attack in the Kashmir Valley sector driving north to capture Keran and Gurais. They also repelled a counterattack aimed at Tithwail. In the Punch Valley the forces besieged in Punch broke out and temporarily linked up with the outside world again. The Kashmir State army was able to defend Skardu from the Gilgit Scouts and thus they were not able to proceed down the Indus valley towards Leh. In August the Chitral Forces under Mata-ul-Mulk besieged Skardu and with the help of artillery were able to take Skardu. This freed the Gilgit Scouts to push further into Ladakh. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ] ] - ] ]]]<br> | |||

| ===Operation Duck=== | |||

| During this time the front began to settle down with less activity by either side, the only major event was an unsuccessful attack by the Indians towards Dras (Operation Duck). The siege of Punch continued. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ] ] - ] ]]]<br> | |||

| ===Operation Easy; Punch link-up=== | |||

| The Indians now started to get the upper hand in all sectors. Punch was finally relieved after a siege of over a year. The Gilgit forces in the High Himalayas, who had previously made good progress, were finally defeated. The Indians pursued as far as Kargil before being forced to halt due to supply problems. The ] was forced by using tanks (which had not been thought possible at that altitude) and Dras was recaptured. The use of tanks was based on experience gained in ] in 1945. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ] ] - ] ]]] | |||

| ===Moves up to cease-fire=== | |||

| At this stage Indian Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru decided to ask UN to intervene. A ] cease-fire was arranged for the ] ]. A few days before the cease-fire the Pakistanis launched a counter attack, which cut the road between Uri and Punch. After protracted negotiations a cease-fire was agreed to by both countries, which came into effect. The terms of the cease-fire as laid out in the ] resolution.<ref>] ]]</ref> of ] ] were adopted by the UN on ] ]. This required Pakistan to withdraw its forces, both regular and irregular, while allowing India to maintain minimum strength of its forces in the state to preserve law and order. On compliance of these conditions a ] was to be held to determine the future of the territory. In all, 1,500 soldiers died on each side during the war<ref></ref> and Pakistan was able to acquire roughly two-fifths of Kashmir, including five of the fourteen ] plus peaks of the world, while India maintained the remaining three fifths of Kashmir, including the most populous and fertile regions. | |||

| Pakistani sources deny the existence of any plan called Operation Gulmarg. However, Shuja Nawaz does list 22 Pashtun tribes involved in the invasion of Kashmir on 22 October.{{sfn|Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited|2008|p=124–125}} | |||

| ==Military insights gained from the war== | |||

| ===On the use of armour=== | |||

| The use of light tanks and armoured cars was important at two stages of the war. Both of these Indian victories involved very small numbers of AFVs. These were:- | |||

| *The defeat of the initial thrust at Srinagar, which was aided by the arrival of 2 armoured cars in the rear of the irregular forces. | |||

| *The forcing of the Zoji-La pass with 11 ]. | |||

| This may show that armour can have a significant psychological impact if it turns up at places thought of as impossible.{{Fact|date=May 2008}} It is also likely that the invaders did not deploy anti-tank weapons to counter these threats. Even the lightest weapons will significantly encumber leg infantry units, so they may well have been perceived as not worth the effort of carrying about, and left in rear areas. This will greatly enhance the psychological impact of the armour when it does appear.{{Fact|date=May 2008}} The successful use of armour in this campaign strongly influenced Indian tactics in ] where great efforts were made to deploy armour to inhospitable regions (although with much less success in that case). | |||

| === |

=== Rebellion in Poonch === | ||

| ] | |||

| *It is interesting to chart the progress of the front lines. After a certain troop density is reached progress was very slow with victories being counted in the capture of individual villages or peaks. Where troop density was lower (as it was in the High Himalayas sector and at the start of the war) rates of advance can be very high.{{Fact|date=May 2008}} | |||

| {{Main|1947 Poonch rebellion}} | |||

| ===Deployment of forces=== | |||

| Sometime in August 1947, the first signs of trouble broke out in ], about which diverging views have been received. Poonch was originally an internal ''jagir'' (autonomous principality), governed by an alternative family line of Maharaja Hari Singh. The taxation is said to have been heavy. The Muslims of Poonch had long campaigned for the principality to be absorbed into the Punjab province of British India. In 1938, a notable disturbance occurred for religious reasons, but a settlement was reached.{{sfn|Ankit, The Problem of Poonch|2010|p=8}} During the ], over 60,000 men from Poonch and Mirpur districts enrolled in the British Indian Army. After the war, they were discharged with arms, which is said to have alarmed the Maharaja.{{sfn|Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict|2003|p=41}} In June, Poonchis launched a 'No Tax' campaign.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=squHDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA143|title=State, Community and Neighbourhood in Princely North India, c. 1900–1950, By I. Copland.|date=26 April 2005|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|isbn=978-0-230-00598-3|pages=143}}</ref> In July, the Maharaja ordered that all the soldiers in the region be disarmed.{{efn|Under the Jammu and Kashmir Arms Act of 1940, the possession of all fire arms was prohibited in the state. The Dogra Rajputs were however exempted in practice.<ref>{{cite book |last=Parashar |first=Parmanand |title=Kashmir and the Freedom Movement |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q0fUEZDsvqoC&pg=PA178 |date=2004 |publisher=Sarup & Sons |isbn=978-81-7625-514-1 |pages=178–179}}</ref>}} The absence of employment prospects coupled with high taxation drove the Poonchis to rebellion.{{sfn|Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict|2003|p=41}} The "gathering head of steam", states scholar Srinath Raghavan, was utilised by the local Muslim Conference led by ] (Sardar Ibrahim) to further their campaign for accession to Pakistan.{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|p=105}} | |||

| *The Jammu and Kashmir state forces were spread out in small packets along the frontier to deal with militant incidents. This made them very vulnerable to a conventional attack. India used this tactic successfully against the Pakistan Army in ] (present day ]) in ]. | |||

| According to state government sources, the rebellious militias gathered in the Naoshera-Islamabad area, attacking the state troops and their supply trucks. A battalion of state troops was dispatched, which cleared the roads and dispersed the militias. By September, order was reestablished.{{sfn|Ankit, The Problem of Poonch|2010|p=9}} The Muslim Conference sources, on the other hand, narrate that hundreds of people were killed in ] during flag hoisting around 15 August and that the Maharaja unleashed a 'reign of terror' on 24 August. Local Muslims also told Richard Symonds, a British Quaker social worker, that the army fired on crowds, and burnt houses and villages indiscriminately.{{sfn|Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History|2013|p=42}} According to the Assistant British High Commissioner in Pakistan, H. S. Stephenson, "the Poonch affair... was greatly exaggerated".{{sfn|Ankit, The Problem of Poonch|2010|p=9}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ===Operation Datta Khel=== | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{main|Operation Datta Khel}} | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| Operation Datta Khel was a military operation and coup planned by ] along with the ], aimed at overthrowing the rule of the ] of ]. The operation was launched shortly after the independence of Pakistan. By 1 November, ] had been annexed from the Dogra dynasty, and was made part of Pakistan after a brief provisional government.<ref name="Warikoo 2009">{{cite book | last=Warikoo | first=K. | title=Himalayan Frontiers of India: Historical, Geo-Political and Strategic Perspectives | publisher=Taylor & Francis | series=Routledge Contemporary South Asia Series | year=2009 | isbn=978-1-134-03294-5 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=w_Z8AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA60| page=60}}</ref> | |||

| === Pakistan's preparations, Maharaja's manoeuvring === | |||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| ], Prime Minister of Pakistan]] | |||

| Scholar ] states that the Maharaja had decided, as early as April 1947, that he would accede to India if it was not possible to stay independent.<ref>{{citation |last=Jha |first=Prem Shankar |author-link=Prem Shankar Jha |title=Response (to the reviews of ''The Origins of a Dispute: Kashmir 1947'') |journal=Commonwealth and Comparative Politics |volume=36 |number=1 |date=March 1998 |doi=10.1080/14662049808447762 |pages=113–123}}</ref>{{rp|115}} The rebellion in Poonch possibly unnerved the Maharaja. Accordingly, on 11 August, he dismissed his pro-Pakistan Prime Minister, Ram Chandra Kak, and appointed retired Major ] in his place.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s5KMCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA155|title=Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris|last=Snedden|first=Christopher|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2015|isbn=978-1-84904-342-7|pages=155}}</ref> On 25 August, he sent an invitation to Justice ] of the Punjab High Court to come as the Prime Minister.{{sfn|Mahajan, Looking Back|1963|p=123}} On the same day, the Muslim Conference wrote to the Pakistani Prime Minister ] warning him that "if, God forbid, the Pakistan Government or the Muslim League do not act, Kashmir might be lost to them".{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|p=103}} This set the ball rolling in Pakistan.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| Liaquat Ali Khan sent a Punjab politician ] to explore the possibility of organising a revolt in Kashmir.{{sfn|Bhattacharya, What Price Freedom|2013|pp=25–27}} Meanwhile, Pakistan cut off essential supplies to the state, such as petrol, sugar and salt. It also stopped trade in timber and other products, and suspended train services to Jammu.{{sfn|Ankit, October 1947|2010|p=9}}{{sfn|Jamal, Shadow War|2009|p=50}} Iftikharuddin returned in mid-September to report that the National Conference held strong in the Kashmir Valley and ruled out the possibility of a revolt.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| ], overlooking Kashmir]] | |||

| Meanwhile, Sardar Ibrahim had escaped to West Punjab, along with dozens of rebels, and established a base in ]. From there, the rebels attempted to acquire arms and ammunition for the rebellion and smuggle them into Kashmir. Colonel ], one of a handful of high-ranking officers in the Pakistani Army,{{efn|According to scholar ], at the time of independence, Pakistan had one major general, two brigadiers, and six colonels, even though the requirements were for 13 major generals, 40 brigadiers, and 52 colonels.<ref>{{cite book |last=Fair |first=C. Christine |author-link=C. Christine Fair |title=Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army's Way of War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=szaTAwAAQBAJ |year=2014 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-989271-6 |page=58 }}</ref>}} with a keen interest in Kashmir, arrived in Murree, and got enmeshed in these efforts. He arranged 4,000 rifles for the rebellion by diverting them from the Army stores. He also wrote out a draft plan titled ''Armed Revolt inside Kashmir'' and gave it to Mian Iftikharuddin to be passed on to the Pakistan's Prime Minister.{{sfn|Guha, India after Gandhi|2008|loc=Section 4.II}}{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|pp=105–106}}{{sfn|Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited|2008|p=120}} | |||

| On 12 September, the Prime Minister held a meeting with Mian Iftikharuddin, Colonel Akbar Khan and another Punjab politician Sardar ]. Hayat Khan had a separate plan, involving the ] and the militant Pashtun tribes from the ]. The Prime Minister approved both the plans, and despatched ], the head of the Muslim League National Guard, to mobilise the Frontier tribes.{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|pp=105–106}}{{sfn|Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited|2008|p=120}} | |||

| ], Prime Minister of India]] | |||

| The Maharaja was increasingly driven to the wall with the rebellion in the western districts and the Pakistani blockade. He managed to persuade Justice Mahajan to accept the post of Prime Minister (but not to arrive for another month, for procedural reasons). He sent word to the Indian leaders through Mahajan that he was willing to accede to India but needed more time to implement political reforms. However, it was India's position that it would not accept accession from the Maharaja unless it had the people's support. The Indian Prime Minister ] demanded that Sheikh Abdullah should be released from prison and involved in the state's government. Accession could only be contemplated afterwards. Following further negotiations, Sheikh Abdullah was released on 29 September.{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|p=106}}<ref>{{cite book|author=Victoria Schofield|title=Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rkTetMfI6QkC|year=2000|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=978-1-86064-898-4|page=44|quote=Nehru therefore suggested to Patel that the maharaja should 'make friends with the National Conference, 'so that there might be this popular support against Pakistan'. Nehru had hoped that the maharaja could be persuaded to accede to India before any invasion took place and he realised that accession would only be more easily accepted if Abdullah, as a popular leader, were brought into the picture.}}</ref> | |||

| Nehru, foreseeing a number of disputes over princely states, formulated a policy that states | |||

| {{blockquote|"wherever there is a dispute in regard to any territory, the matter should be decided by a referendum or plebiscite of the people concerned. We shall accept the result of this referendum whatever it may be."{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|pp=49–51}}{{sfn|Dasgupta, War and Diplomacy in Kashmir|2014|pp=28–29}}}} | |||

| The policy was communicated to Liaquat Ali Khan on 1 October at a meeting of the Joint Defence Council. Khan's eyes are said to have "sparkled" at the proposal. However, he made no response.{{sfn|Raghavan, War and Peace in Modern India|2010|pp=49–51}}{{sfn|Dasgupta, War and Diplomacy in Kashmir|2014|pp=28–29}} | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| === Operations in Poonch and Mirpur === | |||

| {{Main|1947 Poonch rebellion}} | |||

| Armed rebellion started in the Poonch district at the beginning of October 1947.<ref name="ul-Hassan">{{citation |last=ul-Hassan |first=Syed Minhaj |title=Qaiyum Khan and the War of Kashmir, 1947–48 AD. |journal=FWU Journal of Social Sciences |volume=9 |number=1 |year=2015 |pages=1–7 |url=http://www.sbbwu.edu.pk/journal/Journal%20June%202015/1.%20Qaiyum%20Khan%20and%20the%20War%20of%20Kashmir,%20proof%20reading%20and%20APA.pdf |ref={{sfnref|ul Hassan, Qaiyum Khan and the War of Kashmir|2015}} |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170309063114/http://www.sbbwu.edu.pk/journal/Journal%20June%202015/1.%20Qaiyum%20Khan%20and%20the%20War%20of%20Kashmir,%20proof%20reading%20and%20APA.pdf |archive-date=9 March 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{citation |first=Sumit |last=Ganguly |title=Wars without End: The Indo-Pakistani Conflict |journal=The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science |volume=541 |date=September 1995 |pages=167–178 |publisher=Sage Publications |jstor=1048283 |ref={{sfnref|Ganguly, Wars without End|1995}} |doi=10.1177/0002716295541001012|s2cid=144787951 }}</ref> | |||

| The fighting elements consisted of "bands of deserters from the State Army, serving soldiers of the Pakistan Army on leave, ex-servicemen, and other volunteers who had risen spontaneously."{{sfn|Zaheer, The Times and Trial of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy|1998|p=113}} | |||

| The first clash is said to have occurred at ] (near ]) on 3–4 October 1947.<ref name="reg history">Regimental History Cell, ''History of the Azad Kashmir Regiment, Volume 1 (1947–1949)'', Azad Kashmir Regimental Centre, NLC Printers, Rawalpindi,1997</ref> | |||

| The rebels quickly gained control of almost the entire Poonch district. The State Forces garrison at the ] came under heavy siege.<ref>{{cite book |first=Sumantra |last=Bose |author-link=Sumantra Bose |title=Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace |publisher=Harvard University Press |year=2003 |isbn=0-674-01173-2 |page= |url=https://archive.org/details/00book939526581/page/100 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Copland |first=Ian |title=State, Community and Neighbourhood in Princely North India, c. 1900–1950 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=squHDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA143 |year=2005 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK |isbn=978-0-230-00598-3 |page=143 }}</ref> | |||

| In the ] of the Mirpur district, border posts at Saligram and ] on the Jhelum river were captured by rebels around 8 October. ] and ] were lost after some fighting.{{sfn|Cheema, Crimson Chinar|2015|p=57}}{{sfn|Palit, Jammu and Kashmir Arms|1972|p=162}} State Force records reveal that Muslim officers sent with reinforcements sided with the rebels and murdered the fellow state troops.{{sfnp|Brahma Singh, History of Jammu and Kashmir Rifles|2010|pp=235–236}} | |||

| Radio communications between the fighting units were operated by the Pakistan Army.{{sfn|Korbel, Danger in Kashmir|1966|p=94}} Even though the Indian Navy intercepted the communications, lacking intelligence in Jammu and Kashmir, it was unable to determine immediately where the fighting was taking place.<ref>{{cite book |last=Swami |first=Praveen |author-link=Praveen Swami |title=India, Pakistan and the Secret Jihad: The covert war in Kashmir, 1947–2004 |series=Asian Security Studies |publisher=Routledge |year=2007 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Vrl8AgAAQBAJ |isbn=978-0-415-40459-4 |page=19 }}</ref> | |||

| == Accession of Kashmir == | |||

| Following the rebellions in the Poonch and Mirpur area<ref name="lamb">Lamb, Alastair (1997), ''Incomplete partition: the genesis of the Kashmir dispute 1947–1948'', Roxford, {{ISBN|0-907129-08-0}}</ref> and the Pakistan-backed{{sfn|Prasad & Pal, Operations in Jammu & Kashmir |1987|p=18}} Pashtun tribal intervention from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa,<ref name="snl">{{Cite web|url=http://snl.no/Kashmir-konflikten|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151117185400/https://snl.no/Kashmir-konflikten|url-status=dead|title=Kashmir-konflikten|first=Gunnar|last=Filseth|date=13 November 2018|archive-date=17 November 2015|via=Store norske leksikon}}</ref><ref name="nrk">{{Cite web|url=https://www.nrk.no/urix/kashmir-konflikten-1.461250|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130618000408/http://www.nrk.no/nyheter/verden/1.461250|url-status=dead|title=Kashmir-konflikten|date=2 January 2002|archive-date=18 June 2013|website=NRK}}</ref> the Maharaja asked for Indian military assistance. India set the condition that Kashmir must accede to India for it to receive assistance. The Maharaja complied, and the ] recognised the accession of the princely state to India. Indian troops were sent to the state to defend it.{{efn|Accession from Kashmir was requested mainly at the insistence of the Governor General Lord Mountbatten, who was congnizant of the apprehensions of the British military officers on both the sides over the possibility of an inter-dominion war.{{sfn|Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict|2003|pp=52–53}} In fact, there was a ] already issued by the Supreme Commander Claude Auchinleck that, in the event of an inter-Dominion war, all the British officers on both the sides should immediately stand down.{{sfnp|Dasgupta, War and Diplomacy in Kashmir|2014|pp=25–26}} However, Mountbatten's decision has been questioned by Joseph Korbel and biographer Philip Ziegler.{{sfn|Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict|2003|pp=58–59}}}} The ] volunteers aided the ] in its campaign to drive out the Pathan invaders.<ref name="Sayyid Mīr Qāsim">{{cite book| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=KNFJKap8YxwC| title = My Life and Times| publisher = Allied Publishers Limited| year = 1992| isbn = 9788170233558| access-date = 15 November 2015| archive-date = 6 February 2023| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230206113823/https://books.google.com/books?id=KNFJKap8YxwC| url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| Pakistan refused to recognise the accession of Kashmir to India, claiming that it was obtained by "fraud and violence."{{sfn|Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict|2003|p=61}} Governor General ] ordered his Army Chief General Douglas Gracey to move Pakistani troops to Kashmir at once. However, the Indian and Pakistani forces were still under a joint command, and Field Marshal Auchinleck prevailed upon him to withdraw the order. With its accession to India, Kashmir became legally Indian territory, and the British officers could not a play any role in an inter-Dominion war.{{sfn|Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict|2003|p=60}}<ref name="Connell1959">{{cite book |last=Connell |first=John |title=Auchinleck: A Biography of Field-Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_ZYDAAAAMAAJ |year=1959 |publisher=Cassell}}</ref> The Pakistan Army made available arms, ammunition, and supplies to the rebel forces who were dubbed the "Azad Army". Pakistan Army officers "conveniently" on leave and the former officers of the ] were recruited to command the forces. | |||

| ] | |||

| In May 1948, the Pakistan Army officially entered the conflict, in theory to defend the Pakistan borders, but it made plans to push towards Jammu and cut the lines of communications of the Indian forces in the Mehndar Valley.{{sfn|Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict|2003|pp=65–67}} In ], the force of ] under the command of a British officer Major William Brown mutinied and overthrew the governor Ghansara Singh. Brown prevailed on the forces to declare accession to Pakistan.{{sfn|Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict|2003|p=63}}<ref name="Brown2014">{{cite book|last=Brown|first=William|title=Gilgit Rebelion: The Major Who Mutinied Over Partition of India|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_l9tBQAAQBAJ|date=30 November 2014|publisher=Pen and Sword|isbn=978-1-4738-2187-3}}</ref> They are also believed to have received assistance from the ] and the ] of the state of ], one of the ], which had acceded to Pakistan on 6 October 1947.<ref>Martin Axmann, ''Back to the future: the Khanate of Kalat and the genesis of Baluch Nationalism 1915–1955'' (2008), p. 273</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uHQMAQAAMAAJ|title=Frontier facets: Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province|last=Tahir|first=M. Athar|year=2007|publisher=National Book Foundation; Lahore|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| == Stages of the war == | |||

| === Initial invasion === | |||

| ] | |||

| On 22 October the Pashtun tribal attack was launched in the Muzaffarabad sector. The state forces stationed in the border regions around ] and Domel were quickly defeated by tribal forces (Muslim state forces mutinied and joined them) and the way to the capital was open. Among the raiders, there were many active Pakistani Army soldiers disguised as tribals. They were also provided logistical help by the Pakistan Army. Rather than advancing toward Srinagar before state forces could regroup or be reinforced, the invading forces remained in the captured cities in the border region engaging in looting and other crimes against their inhabitants.<ref>Tom Cooper, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161002104334/http://www.acig.info/CMS/index2.php?option=com_content&do_pdf=1&id=159 |date=2 October 2016 }}, Air Combat Information Group, 29 October 2003</ref> In the ], the state forces retreated into towns where they were besieged.<ref>Ministry of Defence, Government of India. Operations in Jammu and Kashmir 1947–1948. (1987). Thomson Press (India) Limited, New Delhi. This is the Indian Official History.</ref> | |||

| Records indicate that the Pakistani tribals beheaded many Hindu and Sikh civilians in Jammu and Kashmir.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Iqbal |first1=Khuram |title=The Making of Pakistani Human Bombs |date=2015 |publisher=Lexington Books |isbn=978-1-4985-1649-5 |page=35 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ppkpCwAAQBAJ |language=en }}</ref> | |||

| {{clear|left}} | |||

| === Indian operation in the Kashmir Valley === | |||

| After the accession, India airlifted troops and equipment to Srinagar under the command of Lt. Col. ], where they reinforced the princely state forces, established a defence perimeter and defeated the tribal forces on the outskirts of the city. Initial defense operations included the notable defense of ] holding both the capital and airfield overnight against extreme odds. The successful defence included an outflanking manoeuvre by Indian ]<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.indiandefencereview.com/interviews/defence-of-srinagar-1947/|title=Defence of Srinagar 1947|work=Indian Defence Review|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160318174203/http://www.indiandefencereview.com/interviews/defence-of-srinagar-1947/|archive-date=18 March 2016}}</ref> during the ]. The defeated tribal forces were pursued as far as ] and ] and these towns, too, were recaptured.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| In the Poonch valley, tribal forces continued to besiege state forces.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| In ], the state paramilitary forces, called the ], joined the invading tribal forces, who thereby obtained control of this northern region of the state. The tribal forces were also joined by troops from ], whose ruler, ] the Mehtar of Chitral, had acceded to Pakistan.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8N7sAAAAMAAJ|title=Persistence and transformation in the Eastern Hindu Kush: a study of resource management systems in Mehlp Valley, Chitral, North Pakistan|last=Rahman|first=Fazlur|date=1 January 2007|publisher=In Kommission bei Asgard-Verlag|isbn=978-3-537-87668-3|page=32|language=en}}</ref><ref name="Wilcox">{{cite book |last=Wilcox |first=Wayne Ayres |title=Pakistan: The Consolidation of a Nation |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=59y9OwAACAAJ |year=1963 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-231-02589-8}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s5KMCwAAQBAJ|title=Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris|last=Snedden|first=Christopher|date=1 January 2015|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-1-84904-342-7|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| === Attempted link-up at Poonch and fall of Mirpur === | |||

| Indian forces ceased pursuit of tribal forces after recapturing Uri and Baramula, and sent a ] southwards, in an attempt to relieve Poonch. Although the relief column eventually reached Poonch, the siege could not be lifted. A second relief column reached ], and evacuated the garrisons of that town and others but were forced to abandon it being too weak to defend it. Meanwhile, Mirpur was captured by the tribal forces on 25 November 1947 with the help of Pakistan's ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Effendi |first=Col. M. Y. |title=Punjab Cavalry: Evolution, Role, Organisation and Tactical Doctrine 11 Cavalry, Frontier Force, 1849–1971 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MeXeAAAAMAAJ |year=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Karachi |isbn=978-0-19-547203-5 |pages=157–160 }}</ref> This led to the ] where Hindu women were reportedly abducted by tribal forces and taken into Pakistan. They were sold in the brothels of Rawalpindi. Around 400 women jumped into wells in Mirpur committing suicide to escape from being abducted.<ref>{{cite book |first=Colonel Tej K. |last=Tikoo |chapter=Genesis of Kashmir Problem and how it got Complicated: Events between 1931 and 1947 AD |title=Kashmir: Its Aborigines and their Exodus |publisher=Lancer Publishers |location=New Delhi, Atlanta |year=2013 |isbn=978-1-935501-58-9}}</ref> | |||

| {{clear left}} | |||

| === Fall of Jhanger and attacks on Naoshera and Uri === | |||

| The tribal forces attacked and captured ]. They then attacked ] unsuccessfully, and made a series of unsuccessful attacks on ]. In the south a minor Indian attack secured ]. By this stage of the war the front line began to stabilise as more Indian troops became available.{{citation needed|date=November 2015}} | |||

| === Operation Vijay: counterattack to Jhanger === | |||

| The Indian forces launched a counterattack in the south recapturing Jhanger and Rajauri. In the Kashmir Valley the tribal forces continued attacking the Uri ]. In the north, ] was brought under siege by the Gilgit Scouts.<ref name="Operations in Jammu and Kashmir 1947–1948 CLAW">{{cite web|last1=Singh|first1=Rohit|title=Operations in Jammu and Kashmir 1947–1948|url=http://www.claws.in/images/journals_doc/SW%20i-10.10.2012.150-178.pdf|website=Centre for Land Warfare Studies|pages=141–142|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161020092019/http://www.claws.in/images/journals_doc/SW%20i-10.10.2012.150-178.pdf|archive-date=20 October 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === Indian spring offensive === | |||

| The Indians held onto Jhanger against numerous counterattacks, who were increasingly supported by regular Pakistani Forces. In the Kashmir Valley the Indians attacked, recapturing Tithwail. The Gilgit scouts made good progress in the High Himalayas sector, infiltrating troops to bring ] under siege, capturing ] and defeating a relief column heading for Skardu.{{citation needed|date=November 2015}} | |||

| === Operations Gulab and Eraze === | |||

| {{main|Siege of Skardu}} | |||

| The Indians continued to attack in the Kashmir Valley sector driving north to capture Keran and Gurais (]).<ref name="Offl_Hist_1947">{{cite book |title=History of Operations in Jammu and Kashmir 1947–1948 |last1=Prasad|first1=S.N.|last2=Dharm Pal |year=1987 |publisher=History Department, Ministry of Defence, Government of India. (printed at Thomson Press (India) Limited) |location=New Delhi |page=418}}</ref>{{rp|308–324}} They also repelled a counterattack aimed at ]. In the Jammu region, the forces besieged in Poonch broke out and temporarily linked up with the outside world again. The Kashmir State army was able to defend Skardu from the Gilgit Scouts impeding their advance down the Indus valley towards Leh. In August the ] and ] under Mata ul-Mulk besieged Skardu and with the help of artillery were able to take Skardu. This freed the Gilgit Scouts to push further into ].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7sneAAAAMAAJ|title=In the Line of Duty: A Soldier Remembers|last=Singh|first=Harbakhsh|date=1 January 2000|publisher=Lancer Publishers & Distributors|isbn=9788170621065|page=227|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TqTjAAAAMAAJ|title=The battles of Zojila, 1948|last=Bloeria|first=Sudhir S.|date=31 December 1997|publisher=Har-Anand Publications|page=72|isbn=9788124105092|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| === Operation Bison === | |||

| {{Main|Military operations in Ladakh (1948)}} | |||

| During this time the front began to settle down. The siege of Poonch continued. An unsuccessful attack was launched by ] (Brig Atal) to capture ] pass. Operation Duck, the earlier epithet for this assault, was renamed as Operation Bison by ]. ] of ] were moved in dismantled conditions through Srinagar and winched across bridges while two field companies of the ] converted the mule track across Zoji La into a jeep track. The surprise attack on 1 November by the brigade with armour supported by two regiments of ] and a regiment of ], forced the pass and pushed the tribal and Pakistani forces back to ] and later ]. The brigade linked up on 24 November at ] with Indian troops advancing from ] while their opponents eventually withdrew northwards toward ].<ref name="Rescue">{{cite book |title=Operation Rescue:Military Operations in Jammu & Kashmir 1947–49 |last=Sinha |first=Lt. Gen. S.K. |year=1977 |publisher=Vision Books |location=New Delhi |isbn=81-7094-012-5 |page=174 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SMwBAAAAMAAJ }}</ref>{{rp|103–127}} The Pakistani attacked the Skardu on 10 February 1948 which was repulsed by the Indian soldiers.<ref name="Ladakh And Kargil">{{cite book|last1=Malhotra|first1=A.|title=Trishul: Ladakh And Kargil 1947–1993|date=2003|publisher=Lancer Publishers|isbn=9788170622963|pages=5|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rWKy6DOTO9YC&q=Sher+Jung+Thapa&pg=PA4}}</ref> Thereafter, the Skardu Garrison was subjected to continuous attacks by the ] for the next three months and each time, their attack was repulsed by the Colonel ] and his men.<ref name="Ladakh And Kargil" /> Thapa held the Skardu with hardly 250 men for whole six long months without any reinforcement and replenishment.<ref name="In a State of Violent Peace: Voices from the Kashmir Valley">{{cite book|last1=Khanna|first1=Meera|title=In a State of Violent Peace: Voices from the Kashmir Valley|date=2015|publisher=HarperCollins Publishers|isbn=9789351364832|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LxTmCQAAQBAJ&q=Thapa+held+the+Skardu+with+hardly+250+men+for+six+long+months&pg=PT65}}</ref> On 14 August, Thapa had to surrender Skardu to the Pakistani Army<ref>{{Cite book|title=In a State of Violent Peace: Voices from the Kashmir Valley|last=Khanna|first=Meera|publisher=HarperCollins Publisher|year=2015|isbn=9789351364832}}</ref> and raiders after a year long siege.{{sfn|Barua|2005|pp=164–165}} | |||

| === Operation Easy; Poonch link-up === | |||

| {{Main|Military operations in Poonch (1948)}} | |||

| The Indians now started to get the upper hand in all sectors. ] was finally relieved after a siege of over a year. The Gilgit forces in the High Himalayas, who had previously made good progress, were finally defeated. The Indians pursued as far as Kargil before being forced to halt due to supply problems. The ] pass was forced by using tanks (which had not been thought possible at that altitude) and Dras was recaptured.{{citation needed|date=November 2015}} | |||

| At 23.59 hrs on 1 January 1949, a United Nations-mediated ceasefire came into effect, bring the war to an end.{{sfn|Prasad & Pal, Operations in Jammu & Kashmir |1987|p=371}} | |||

| {{Clear|left}} | |||

| == Aftermath == | |||

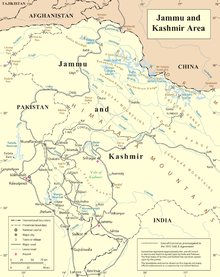

| ] between India and Pakistan agreed in the Simla Agreement (UN Map)]] | |||

| The terms of the ceasefire, laid out in a ] resolution on 13 August 1948,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/uncom1.htm|title=Resolution adopted by the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan on 13 August 1948.|access-date=3 April 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160307070548/https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/uncom1.htm|archive-date=7 March 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> were adopted by the commission on 5 January 1949.This required Pakistan to withdraw its forces, both regular and irregular, while allowing India to maintain minimal forces within the state to preserve law and order. Upon compliance with these conditions, a ] was to be held to determine the future of the territory. Owing to disagreements over the demilitarisation steps, a plebiscite was never held and the cease-fire line essentially became permanent. Some sources may refer to 5 January as the beginning of the ceasefire.<ref name="e049">{{cite book | last1=Pastor-Castro | first1=R. | last2=Thomas | first2=M. | title=Embassies in Crisis: Studies of Diplomatic Missions in Testing Situations | publisher=Taylor & Francis | series=Routledge Studies in Modern History | year=2020 | isbn=978-1-351-12348-8 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qzX7DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT144| page=144}}</ref> | |||

| Indian losses in the war totalled 1,104 killed and 3,154 wounded;<ref name="Kargil from Surprise to Victory" /> Pakistani, about 6,000 killed and 14,000 wounded.<ref name="Honor and Glory" /> | |||