| Revision as of 07:05, 23 September 2009 edit217.40.144.123 (talk) →Plot summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:37, 4 January 2025 edit undo80.47.104.17 (talk)No edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1890 novel by Oscar Wilde}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Dorian Gray}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Dorian Gray|the character|Dorian Gray (character)||Dorian Gray (disambiguation)|and|The Picture of Dorian Gray (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Otheruses}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=January 2017}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2017}} | |||

| {{infobox Book | <!-- See Misplaced Pages:WikiProject_Novels or Misplaced Pages:WikiProject_Books --> | |||

| {{Infobox book <!-- See Misplaced Pages:WikiProject_Novels or Misplaced Pages:WikiProject_Books --> | |||

| | name = The Picture of Dorian Gray | |||

| | name = The Picture of Dorian Gray | |||

| | orig title = | |||

| | image = Lippincott doriangray.jpg | |||

| | translator = | |||

| | |

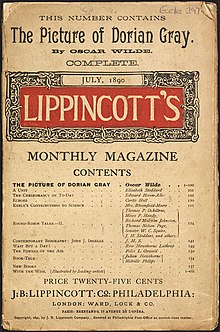

| caption = The story was first published in 1890 in ''Lippincott's Monthly Magazine'' | ||

| | author = ] | |||

| | image_caption = Cover of the first edition | |||

| | |

| language = English | ||

| | genre = ], ], ] | |||

| | cover_artist = | |||

| | |

| published = 1890 '']'' | ||

| | media_type = Print | |||

| | language = ] | |||

| | |

| oclc = 53071567 | ||

| | |

| wikisource = The Picture of Dorian Gray | ||

| | orig_lang_code = en | |||

| | publisher = '']'' | |||

| | country = ] | |||

| | release_date = 1890 | |||

| | dewey = 823.8 | |||

| | media_type = Print (] & ]) | |||

| | |

| congress = PR5819.A2 | ||

| | isbn = ISBN 0-14-143957-2 (Modern paperback edition) | |||

| | preceded_by = | |||

| | followed_by = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''''The Picture of Dorian Gray''''' is |

'''''The Picture of Dorian Gray''''' is a ] and ] ] ] by Irish writer ]. A shorter ]-length version was published in the July 1890 issue of the American periodical '']''.<ref name="Penguin Intro pg ix">''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) – Introduction</ref><ref name="guardian">{{cite news | last = McCrum | first = Robert | title =The 100 best novels: No 27 – The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (1891) | work =]| date = March 24, 2014 | url = https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/24/100-best-novels-picture-dorian-gray-oscar-wilde | access-date = 2018-08-11}}</ref> The novel-length version was published in April 1891. It is regarded as a classic of ] and has been adapted for films and stage performances. | ||

| The |

The story revolves around a ] of ] painted by Basil Hallward, a friend of Dorian's and an artist infatuated with Dorian's ]. Through Basil, Dorian meets Lord Henry Wotton and is soon enthralled by the aristocrat's ] worldview: that beauty and sensual fulfilment are the only things worth pursuing in life. Newly understanding that his beauty will fade, Dorian expresses the desire to ], to ensure that the picture, rather than he, will age and fade. The wish is granted, and Dorian pursues a ] life of varied ] experiences while staying young and beautiful; all the while, his portrait ages and visually records every one of Dorian's ]s.<ref name="gutenberg_20_1">] (Project Gutenberg 20-chapter version), line 3479 et seq. in plain text (Chapter VII).</ref> | ||

| Wilde's only novel, it was subject to much controversy and criticism in its time but has come to be recognised as a classic of ]. | |||

| ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' is considered one of the last works of classic ] ] with a strong ] ].<ref name="Gothic Horror"> - a website which discusses ] and ] from the 19th century onwards (retrieved 30 July 2006)</ref> It deals with the artistic movement of the ], and ],{{attribution needed|date=September 2008}} {{clarify|date=September 2009|reason=in addition to cite needed for homosexuality claim, didn't it deal with hedonism,(mentioned above) sensuality and aesthetism?}} both of which caused ] when the book was published. However, in recent times, the book has been regarded as one of the modern classics of Western literature.<ref name="Classic"> - a website which gives synopses for several books, including ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (retrieved 27 August 2006</ref> | |||

| == |

==Origins== | ||

| ] | |||

| In 1882, Oscar Wilde met ] in Ottawa, where he visited her studios. In 1887, Richards moved to London where she renewed her acquaintance with Wilde and painted his portrait. Wilde described that incident as being the inspiration for the novel: | |||

| The novel begins with Lord Henry Wotton, observing the artist Basil Hallward painting the portrait of a handsome young man named Dorian Gray. Dorian arrives later, meeting Wotton. After hearing Lord Henry's world view, Dorian begins to think beauty is the only worthwhile aspect of life, the only thing left to pursue. He wishes that the portrait of himself which Basil is painting would grow old in his place. Under the influence of Lord Henry, Dorian begins to explore his senses. He discovers an actress, Sibyl Vane, who performs ] in a dingy theatre. Dorian approaches her and soon proposes marriage. Sibyl, who refers to him as "Prince Charming," rushes home to tell her skeptical mother and brother. Her protective brother, James, tells her that if "Prince Charming" harms her, he will kill him. | |||

| {{Blockquote | |||

| |text=In December, 1887, I gave a sitting to a Canadian artist who was staying with some friends of hers and mine in South Kensington. When the sitting was over, and I had looked at the portrait, I said in jest, 'What a tragic thing it is. This portrait will never grow older and I shall. If it was only the other way!' The moment I had said this it occurred to me what a capital plot the idea would make for a story. The result is 'Dorian Gray.'<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Scharnhorst |first1=Gary |date=July 2010 |title=Oscar Wilde on the Origin of "The Picture of Dorian Gray": A Recovered Letter |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/45270175 |journal=The Wildean |volume=July 2010 |issue=37 |pages=12–15 |doi= |jstor=45270175 |access-date=June 2, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| In 1889, ], an editor for ''Lippincott's Monthly Magazine'', was in London to solicit novellas to publish in the magazine. On 30 August 1889, Stoddart dined with Oscar Wilde, ] and ]<ref>{{cite book|first=Oscar|last=Wilde|title=Selected Letters|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1979|editor=R. Hart-Davis|pages=95}}</ref> at the ], and commissioned novellas from each writer.<ref name="FrankelIntro">{{cite book|last=Frankel|first=Nicholas|title=The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition|publisher=Belknap Press (])|year=2011|isbn=978-0-674-05792-0|editor1-last=Wilde|editor1-first=Oscar|editor1-link=Oscar Wilde|location=]|pages=38–64|chapter=Textual Introduction|orig-year=1890}}</ref> Doyle promptly submitted '']'', which was published in the February 1890 edition of ''Lippincott's''. Stoddart received Wilde's manuscript for ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' on 7 April 1890, seven months after having commissioned the novel from him.<ref name="FrankelIntro" /> | |||

| Dorian invites Basil and Lord Henry to see Sibyl perform in '']''. Sibyl, whose only knowledge of love was love of theatre, loses her acting abilities through the experience of true love with Dorian. Dorian rejects her, saying her beauty was in her art, and he is no longer interested in her if she can no longer act. When he returns home he notices that Basil's portrait of him has changed. Dorian realises his wish has come true - the portrait now bears a subtle sneer and will age with each sin he commits, whilst his own appearance remains unchanged. He decides to reconcile with Sibyl, but Lord Henry arrives in the morning to say Sibyl has killed herself by swallowing ] (hydrogen cyanide). With the persuasion and encouragement of Lord Henry, Dorian realizes that lust and looks is where his life is headed and he needs nothing else. That marked the end of Dorian's last and only true love affair. Over the next 18 years, Dorian experiments with every vice, mostly under the influence of a "poisonous" French novel, a present from Lord Henry. Wilde never reveals the title but his inspiration was possibly drawn from ]'s '']'' (''Against Nature'') due to the likenesses that exist between the two novels.<ref name="A Rebours">{{cite web | url=http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-92865915.html | title=Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray | publisher=Highbeam Research| accessdate=2007-04-26}}</ref> | |||

| In July 1889, Wilde published "]", a very different story but one that has a similar title to ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' and has been described as "a preliminary sketch of some of its major themes", including homosexuality.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Hovey|first=Jaime|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1FUQdB7QS3UC&q=%22preliminary+sketch+of+some+of+its+major+themes%22|title=A Thousand Words: Portraiture, Style, and Queer Modernism|date=2006|publisher=Ohio State University Press|isbn=978-0-8142-1014-7|page=40|language=en}}</ref><ref name="LawlerKnott">{{Cite journal|last1=Lawler|first1=Donald L.|last2=Knott|first2=Charles E.|date=1976|title=The Context of Invention: Suggested Origins of "Dorian Gray"|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/435740|journal=Modern Philology|volume=73|issue=4|pages=389–398|doi=10.1086/390676|jstor=435740|s2cid=162007929|issn=0026-8232}}</ref> | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| One night, before he leaves for Paris, Basil arrives to question Dorian about rumours of his indulgences. Dorian does not deny his debauchery. He takes Basil to the portrait, which is as hideous as Dorian's sins. In anger, Dorian blames the artist for his fate and stabs Basil to death. He then blackmails an old friend named Alan Campbell, who is a chemist, into destroying Basil's body. Wishing to escape his crime, Dorian travels to an ]. James Vane is nearby and hears someone refer to Dorian as "Prince Charming." He follows Dorian outside and attempts to shoot him, but he is deceived when Dorian asks James to look at him in the light, saying he is too young to have been involved with Sibyl 18 years ago. James releases Dorian but is approached by a woman from the opium den who chastises him for not killing Dorian and tells him Dorian has not aged for 18 years. | |||

| == Publication and versions == | |||

| While at dinner, Dorian sees Sibyl Vane's brother stalking the grounds and fears for his life. However, during a game-shooting party a few days later, a lurking James is accidentally shot and killed by one of the hunters. After returning to London, Dorian informs Lord Henry that he will be good from now on, and has started by not breaking the heart of his latest innocent conquest, a vicar's daughter in a country town, named Hetty Merton. At his apartment, Dorian wonders if the portrait has begun to change back, losing its senile, sinful appearance, now he has changed his immoral ways. He unveils the portrait to find it has become worse. Seeing this, he questions the motives behind his "mercy," whether it was merely vanity, curiosity, or the quest for new emotional excess. Deciding that only full ] will ] him, but lacking feelings of guilt and fearing the consequences, he decides to destroy the last vestige of his conscience. In a rage, he picks up the knife that killed Basil Hallward and plunges it into the painting. His servants hear a cry from inside the locked room and send for the police. They find Dorian's body, stabbed in the heart and suddenly aged, withered and horrible. It is only through the rings on his hand that the corpse can be identified. Beside him, however, the portrait has reverted to its original form. | |||

| == |

=== 1890 novella === | ||

| The literary merits of ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' impressed Stoddart, but he told the publisher, George Lippincott, "in its present condition there are a number of things an innocent woman would make an exception to."<ref name="FrankelIntro" /> Fearing that the story was indecent, Stoddart deleted around five hundred words without Wilde's knowledge prior to publication. Among the pre-publication deletions were: (i) passages alluding to homosexuality and to homosexual desire; (ii) all references to the fictional book title ''Le Secret de Raoul'' and its author, Catulle Sarrazin; and (iii) all "mistress" references to Gray's lovers, Sibyl Vane and Hetty Merton.<ref name="FrankelIntro" /> | |||

| It was published in full as the first 100 pages in both the American and British editions of the July 1890 issue, first printed on 20 June 1890.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lorang |first=Elizabeth |date=2010|title="The Picture of Dorian Gray" in Context: Intertextuality and "Lippincott's Monthly Magazine"|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/25732085|journal=Victorian Periodicals Review|volume=43|issue=1|pages=19–41|jstor=25732085|issn=0709-4698}}</ref> Later in the year the publisher of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, ], published a collection of complete novels from the magazine, which included Wilde's.<ref>{{cite book |last=Mason |first=Stuart |title=Bibliography of Oscar Wilde |publisher=T. Werner Laurie |location=London |date=1914 |pages=108–110}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| === 1891 novel === | |||

| In a letter, Wilde said the main characters are reflections of himself: "Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry what the world thinks me: Dorian what I would like to be—in other ages, perhaps"<ref name="The Modern Library Gray"> - a synopsis of the book coupled with a short biography of ] (retrieved 6 July 2006)</ref>. | |||

| ]] of the ] 1891 edition of ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' with decorative lettering, designed by ]]] | |||

| For the fuller 1891 novel, Wilde retained Stoddart's edits and made some of his own, while expanding the text from thirteen to twenty chapters and added the book's famous preface. Chapters 3, 5, and 15–18 are new, and chapter 13 of the magazine edition was divided into chapters 19 and 20 for the novel.<ref>{{cite web|title=Differences between the 1890 and 1891 editions of "Dorian Gray"|url=https://mdoege.github.io/Dorian_Gray_diff/|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131226202802/http://mdoege.github.io/Dorian_Gray_diff/|archive-date=26 December 2013|access-date=25 December 2013|publisher=Github.io}}</ref> Revisions include changes in character dialogue as well as the addition of the preface, more scenes and chapters, and Sibyl Vane's brother, James Vane.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pudney |first=Eric |date=2012 |title=Paradox and the Preface to "Dorian Gray" |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/45270321 |journal=The Wildean |issue=41 |pages=118–123 |issn=1357-4949 |jstor=45270321}}</ref> | |||

| The edits have been construed as having been done in response to criticism, but Wilde denied this in his 1895 ], only ceding that critic ], whom Wilde respected, did write several letters to him "and in consequence of what he said I did modify one passage" that was "liable to misconstruction".<ref>{{Cite book|last=Mikhail|first=E. H.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vCmuCwAAQBAJ|title=Oscar Wilde: Interviews and Recollections|year=1979|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-1-349-03926-5|pages=279|language=en}}</ref><ref>Lawler, Donald L., ''An Inquiry into Oscar Wilde's Revisions of 'The Picture of Dorian Gray{{'}}'' (New York: Garland, 1988)</ref> A number of edits involved obscuring ] references, to simplify the moral message of the story.<ref name="FrankelIntro" /> In the magazine edition (1890), Basil tells Lord Henry how he "worships" Dorian, and begs him not to "take away the one person that makes my life absolutely lovely to me." In the magazine edition, Basil focuses upon love, whereas, in the book edition (1891), he focuses upon his art, saying to Lord Henry, "the one person who gives my art whatever charm it may possess: my life as an artist depends on him." | |||

| The main characters are: | |||

| Wilde's textual additions were about the "fleshing out of Dorian as a character" and providing details of his ancestry that made his "psychological collapse more prolonged and more convincing."<ref name="DorianGray ANoteOnTheText">''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) – A Note on the Text</ref> The introduction of the James Vane character to the story develops the socio-economic background of the Sibyl Vane character, thus emphasising Dorian's selfishness and foreshadowing James's accurate perception of the essentially immoral character of Dorian Gray; thus, he correctly deduced Dorian's dishonourable intent towards Sibyl. The sub-plot about James Vane's dislike of Dorian gives the novel a Victorian tinge of class struggle. | |||

| * '''Dorian Gray''' – a handsome young man who becomes enthralled with Lord Henry's idea of a new ]. He begins to indulge in every kind of pleasure, moral and immoral. | |||

| * '''Basil Hallward''' – an artist who becomes ] with Dorian's beauty. Dorian helps Basil to realise his ]istic potential, as Basil's portrait of Dorian proves to be his finest work. | |||

| * '''Lord Henry "Harry" Wotton''' – a ] who is a friend to Basil initially, but later becomes more intrigued with Dorian's beauty and naivete. Extremely witty, Lord Henry is seen as a ] of ] at the ], espousing a view of indulgent ]. He conveys to Dorian his world view, and Dorian becomes corrupted as he attempts to emulate him. | |||

| In April 1891 ] published the revised version of ''The Picture of Dorian Gray''.<ref name="owc-intro">{{cite book|last=Wilde|first=Oscar|title=The Picture of Dorian Gray|year= 2006|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780192807298|edition=Oxford World's Classics|contribution=Introduction|contributor-last=Bristow|contributor-first=Joseph}}</ref> In the decade after Wilde's death, the authorised edition of the novel was published by ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Mason |first=Stuart |title=Bibliography of Oscar Wilde |publisher=T. Werner Laurie |location=London |date=1914 |pages=347–349}}</ref> | |||

| The other characters are: | |||

| === 2011 "uncensored" novella === | |||

| * '''Sibyl Vane''' – An exceptionally talented and beautiful (though extremely poor) actress with whom Dorian falls in love. Her love for Dorian destroys her acting ability, as she no longer finds pleasure in portraying fictional love when she is experiencing love in reality. | |||

| The original typescript submitted to ''Lippincott's Monthly Magazine'', now housed at ], had been largely forgotten except by professional Wilde scholars until the 2011 publication of ''The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition'' by the Belknap Press. This edition includes the roughly 500 words of text deleted by J. M. Stoddart, the story's initial editor, prior to its publication in ''Lippincott's'' in 1890.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Picture of Dorian Gray – Oscar Wilde, Nicholas Frankel – Harvard University Press|url=http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?recid=31147|access-date=30 May 2011|publisher=Hup.harvard.edu}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{cite news|first=Alison|last=Flood|date=27 April 2011|title=Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray published|work=The Guardian|location=London|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/apr/27/dorian-gray-oscar-wilde-uncensored|access-date=30 May 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|date=4 April 2011|title=Thursday: The Uncensored "Dorian Gray"|newspaper=The Washington Post|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/books/thursday-the-uncensored-dorian-gray/2011/03/28/AFw5cD6B_story.html|access-date=30 May 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Wilde|first=Oscar|title=The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition|publisher=Belknap Press (])|year=2011|isbn=978-0-674-05792-0|editor1-last=Frankel|editor1-first=Nicholas|location=]|author-link=Oscar Wilde|orig-year=1890}}</ref> For instance, in one scene, Basil Hallward confesses that he has worshipped Dorian Gray with a "romance of feeling", and has never loved a woman.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| * '''James Vane''' – Sibyl's brother who is to become a ] and leave for ]. He is extremely protective of his sister, especially as his mother is useless and concerned only with Dorian's money. He is hesitant to leave his sister, believing Dorian will harm her and promises to be vengeful if any harm should come to her. | |||

| * '''Alan Campbell''' – a chemist and once a good friend of Dorian; he ended their friendship when Dorian's reputation began to come into question. | |||

| * '''Lord Fermor''' – Lord Henry's uncle. He informs Lord Henry about Dorian's lineage. | |||

| * '''Victoria, Lady Henry Wotton''' – Lord Henry's wife, who only appears once in the novel while Dorian waits for Lord Henry; she later divorces Lord Henry in exchange for a pianist. | |||

| == |

== Preface == | ||

| Following the criticism of the magazine edition of the novel, Wilde wrote a preface in which he indirectly addressed the criticisms in a series of epigrams. The preface was first published in ''The Fortnightly Review'' and then, a month later, in the book version of the novel.<ref>{{cite book |first=Oscar |last=Wilde |editor-first=Joseph |editor-last=Bristow |date=2005 |title=The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 3: The Picture of Dorian Gray: The 1890 and 1891 Texts |location=Oxford |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=lvi}}</ref> The content, style, and presentation of the preface made it famous in its own right as a literary and artistic manifesto in support of artists' rights and ]. | |||

| === Aestheticism and duplicity === | |||

| To communicate how the novel should be read, Wilde used ]s to explain the role of the artist in society, the purpose of art, and the value of beauty. It traces Wilde's cultural exposure to ] and to the philosophy of Chuang Tsǔ (]). Before writing the preface, Wilde had written a book review of ]'s translation of the work of Zhuang Zhou, and in the essay "]", Oscar Wilde said: | |||

| ] is a strong motif and is tied in with the concept of the ]. A major theme is that aestheticism is merely an absurd abstract that only serves to disillusion rather than dignify the concept of beauty. Although Dorian is ]ic, when Basil accuses him of making Lord Henry's sister's name a "by-word," Dorian replies "Take care, Basil. You go too far"<ref> name="DorianGray Chapter XII">hola''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) - Chapter XII</ref> suggesting Dorian still cares about his outward image and standing within ] society. Wilde highlights Dorian's pleasure of living a double life,<ref> name="DorianGray Chapter XI">''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) - Chapter XI</ref> Not only does Dorian enjoy this sensation in private, but he also feels "keenly the terrible pleasure of a double life" when attending a society gathering just 24 hours after committing a murder. | |||

| {{blockquote|The honest ratepayer and his healthy family have no doubt often mocked at the dome-like forehead of the philosopher, and laughed over the strange perspective of the landscape that lies beneath him. If they really knew who he was, they would tremble. For ] spent his life in preaching the great creed of Inaction, and in pointing out the uselessness of all things.<ref name="Artist as Critic 222">Ellmann, ''The Artist as Critic'' p. 222.</ref>}} | |||

| This duplicity and indulgence is most evident in Dorian's visit to the opium dens of London. ] conflates the images of the upper class and lower class by having the supposedly upright Dorian visit the impoverished districts of London. Lord Henry asserts that "crime belongs exclusively to the lower orders... I should fancy that crime was to them what art is to us, simply a method of procuring extraordinary sensations", which suggests that Dorian is both the criminal and the ] combined in one man. This is perhaps linked to ]'s ''],'' which Wilde admired.<ref name="Penguin Intro pg ix" /> The division that was witnessed in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, although extreme, is evident in Dorian Gray, who attempts to contain the two divergent parts of his personality. This is a recurring theme in many Gothic novels, of which ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' is one of the last. | |||

| ==Summary== | |||

| === Homoeroticism === | |||

| In ] England, Lord Henry Wotton observes artist Basil Hallward painting the portrait of Dorian Gray, a young man who is Basil's ultimate ]. The ] Lord Henry thinks that ] is the only aspect of life worth pursuing, prompting Dorian to wish that his portrait would age instead of himself. | |||

| Under Lord Henry's influence, Dorian fully explores his sensuality. He discovers the actress Sibyl Vane, who performs ] plays in a dingy, working-class theatre. Dorian courts her and soon proposes marriage. The enamoured Sibyl calls him "Prince Charming". Her brother, James, warns that if "Prince Charming" harms her, he will murder him. | |||

| The name "Dorian" has connotations of the ], an ancient Greek tribe. Robert Mighall suggests this could be Wilde hinting at a connection to "]", a euphemism for the ] accepted as everyday in ].{{Citation needed|date=September 2009}} Indeed, Dorian is described using the ] of the ], being likened to ], a person who looks as if "he were made of ivory and rose-leaves." However, Wilde does not mention any homosexual acts explicitly—it would have been inconceivable at the time—and descriptions of Dorian's "]" are often vague, although there does appear{{attribution needed|date=September 2008}} to be an element of homoeroticism in the competition between Lord Henry and Basil, both of whom compete for Dorian's attention. Both of them make comments about Dorian in praise of his good looks and youthful demeanour, Basil going as far to say that "as long as I live, the personality of Dorian Gray will dominate me."<ref name="DorianGray Chapter I">''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) - Chapter I</ref> However, while Basil is shunned, Dorian wishes to emulate Lord Henry, which in turn, rouses Lord Henry from his "characteristic languor to a desire to influence Dorian, a process that is itself a{{clarify|date=September 2009|reason=make clear this is a view of glbtq.com; is there scholarly support for it? "is itself a sublimated expression" appears to be too definite a statement rather than an opinion.}} sublimated expression of ]."<ref name="glbtq"> - an analysis of the works of Oscar Wilde, from an encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and queer culture (retrieved 29 July 2006)</ref> Since the only person Dorian claims to have loved is a woman, Sibyl Vane, it is also possible Wilde intended his character to display Greek ].{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} | |||

| Dorian invites Basil and Lord Henry to see Sibyl perform in a play.{{efn|More specifically, '']''.}} Sibyl, too enamoured with Dorian to act, performs poorly, which makes Basil and Lord Henry think Dorian has fallen in love with Sibyl because of her beauty instead of her talent. Embarrassed, Dorian rejects Sibyl, saying that acting is her beauty; without that, she no longer interests him. Returning home, Dorian notices that the portrait has changed; his wish came true, and the man in the portrait bears a subtle sneer of cruelty. | |||

| The later corruption of Dorian seems to make what was once a boyish charm a destructive influence. Basil asks why Dorian's "friendship is so fatal to young men", commenting upon the "shame and sorrow" that the father of one of the disgraced boys displays. Dorian only destroys these men when he becomes "intimate" with them, suggesting that the friendships between Dorian and the men in question become more than simply ]. The shame associated with these relationships is bipartite: the families of the boys are upset that their sons may have indulged in a homosexual relationship with Dorian Gray, and also feel shame that they have now lost their place in society, their names having been sullied. Moreover, Alan Campbell is blackmailed by Dorian with the threat that the 'secret' held between them will be revealed. The loss of status is encapsulated in Basil's questioning of Dorian: speaking of the Duke of Perth, a disgraced friend of Dorian's, he asks "what gentleman would associate with him?"<ref name="DorianGray Chapter XII">''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) - Chapter XII</ref> The novel is considered groundbreaking in the context that, in literature, "Dorian Gray was one of the first in a long list of ] fellows whose homosexual tendencies secured a terrible fate."<ref name="Meloy">{{cite web |last =Meloy |first =Kilian |title ="Influential Gay Characters in Literature" |work =AfterElton.com |url =http://www.afterelton.com/print/2007/9/groundbreakinggaycharacters |date =2007-09-24 |accessdate =2007-10-09 }}</ref> | |||

| Conscience-stricken and lonely, Dorian decides to reconcile with Sibyl, but is too late; she has killed herself. Dorian understands that, where his life is headed, lust and beauty shall suffice. Dorian locks the portrait up, and for eighteen years, he experiments with every vice, influenced by a morally poisonous French novel that Lord Henry gave him. | |||

| == Allusions to other works == | |||

| === The Republic === | |||

| One night, before leaving for Paris, Basil goes to Dorian's house to ask him about rumours of his self-indulgent ]. Dorian does not deny his debauchery, and takes Basil to see the portrait. The portrait has become so hideous that Basil can only identify it as his by the signature on it. Horrified, Basil beseeches Dorian to pray for salvation. Furious, Dorian blames his fate on Basil and kills him. Dorian then blackmails an old friend, scientist Alan Campbell, into using his knowledge of chemistry to destroy Basil's body. Alan later kills himself. | |||

| Glaucon and Adeimantus present the myth of ], by which Gyges made himself invisible. They ask Socrates, if one came into possession of such a ring, why should he act justly? Socrates replies that even if no one can see one's physical appearance, the soul is disfigured by the evils one commits. This disfigured (the antithesis of beautiful) and corrupt soul is imbalanced and disordered, and in itself undesirable regardless of other advantages of acting unjustly. Dorian Gray's portrait is the means by which other individuals, such as Dorian's friend Basil, shortly before Dorian kills him, may see Dorian's distorted soul. | |||

| ] | |||

| === Tannhäuser === | |||

| To escape the guilt of his crime, Dorian goes to an ], where, unbeknownst to him, James Vane is present. James is seeking vengeance upon Dorian ever since Sibyl's death but had no leads to pursue as the only thing he knew about Dorian was the nickname she called him. There, however, he hears someone refer to Dorian as "Prince Charming". James accosts Dorian, who deceives him into believing he is too young to have known Sibyl, as his face is still that of a young man. James relents and releases Dorian but is then approached by a woman from the den who reproaches James for not killing Dorian. She confirms Dorian's identity and explains that he has not aged in eighteen years. | |||

| At one point, Dorian Gray attends a performance of ]'s opera, ], and is explicitly said to personally identify with the work. Indeed, the opera bears some striking resemblances with the novel, and, in short, tells the story of a medieval (and historically real) singer, whose art is so beautiful that he causes ], the goddess of love herself, to fall in love with him, and to offer him eternal life with her in the Venusberg. Tannhäuser becomes dissatisfied with his life there, however, and elects to return to the harsh world of reality, where, after taking part in a song-contest, he is sternly censured for his sensuality, and eventually dies in his search for repentance and the love of a good woman. | |||

| James begins to stalk Dorian, who starts to fear for his life. During a shooting party, a hunter accidentally kills James, who was lurking in a thicket. On returning to London, Dorian tells Lord Henry that he will live righteously from now on. His new probity begins with deliberately not breaking the heart of Hetty Merton, his current romantic interest. Dorian wonders if his newly found goodness has rescinded the corruption in the picture but when he looks at it, he sees an even uglier image of himself. From that, Dorian understands that his true motives for the self-sacrifice of moral reformation were the vanity and curiosity of his quest for new experiences, along with the desire to restore beauty to the picture. | |||

| === Faust === | |||

| ] | |||

| Deciding that only full ] will ] him of wrongdoing, Dorian decides to destroy the last vestige of his conscience and the only piece of evidence remaining of his crimes – the portrait. Furious, he takes the knife with which he murdered Basil and stabs the picture. | |||

| His servants awaken on hearing a cry from the locked room; on the street, a passerby who also heard it calls the police. On entering the locked room, the servants find an old man stabbed in the heart, his figure withered and decrepit. They identify the corpse as Dorian only by the rings on the fingers, while the portrait beside him is beautiful again. | |||

| Wilde himself stated that "in every first novel the hero is the author as ] or Faust."{{Citation needed|September 2009|date=September 2009}} As in ], a temptation is placed before the lead character Dorian, the potential for ageless beauty; Dorian indulges in this temptation. In both stories, the lead character entices a beautiful woman to love them and kills not only her, but also that woman's brother, who seeks revenge.<ref name="Faust"> - a quote from Oscar Wilde about ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' and its likeness to ] (retrieved 7 July 2006)</ref>{{Dead link|date=May 2009}} Wilde went on to say that the notion behind ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' is "old in the history of literature" but was something to which he had "given a new form".<ref name="DorianGray Preface">'The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) - Preface</ref> | |||

| ==Characters== | |||

| Unlike Faust, there is no point at which Dorian makes a deal with the ]. However, Lord Henry's ]al outlook on life, and ] nature seems to be in keeping with the idea of the devil's role, that of the temptation of the ] and ], qualities which Dorian exemplifies at the beginning of the book. Although Lord Henry takes an interest in Dorian, it does not seem that he is aware of the effect of his actions. However, Lord Henry advises Dorian that "the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing";<ref name="DorianGray Chapter II">''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) - Chapter II</ref> in this sense, Lord Henry can be seen to represent the Devil, "leading Dorian into an unholy pact by manipulating his innocence and insecurity."<ref name="Devil's Advocate"> - a summary and commentary of Chapter II of ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (retrieved 29 July 2006)</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| *] – a handsome, ] young man enthralled by Lord Henry's "new" ]. He indulges in every pleasure and virtually every 'sin', studying its effect upon him. | |||

| * Basil Hallward – a deeply moral man, the painter of the portrait, and infatuated with Dorian, whose patronage realises his potential as an artist. The picture of Dorian Gray is Basil's masterpiece. | |||

| * Lord Henry "Harry" Wotton – an imperious ] and a decadent ] who espouses a philosophy of self-indulgent hedonism. Initially Basil's friend, he neglects him for Dorian's beauty. The character of witty Lord Harry is a ] of ] at the '']'' – of Britain at the end of the 19th century. Lord Harry's ] world view corrupts Dorian, who then successfully emulates him. To the aristocrat Harry, the observant artist Basil says, "You never say a moral thing, and you never do a wrong thing." Lord Henry takes pleasure in impressing, influencing, and even misleading his acquaintances (to which purpose he bends his considerable wit and eloquence) but appears not to observe his own hedonistic advice, preferring to study himself with scientific detachment. His distinguishing feature is total indifference to the consequences of his actions. | |||

| * Sibyl Vane – a talented actress and singer, she is a beautiful girl from a poor family with whom Dorian falls in love. Her love for Dorian ruins her acting ability, because she no longer finds pleasure in portraying fictional love as she is now experiencing real love in her life. She commits suicide with poison on learning that Dorian no longer loves her; at that, Lord Henry likens her to ], in ''Hamlet''. | |||

| * James Vane – Sibyl's younger brother, a sailor who leaves for Australia. He is very protective of his sister, especially as their mother cares only for Dorian's money. Believing that Dorian means to harm Sibyl, James hesitates to leave, and promises vengeance upon Dorian if any harm befalls her. After Sibyl's suicide, James becomes obsessed with killing Dorian, and ] him, but a hunter accidentally kills James. The brother's pursuit of vengeance upon the lover (Dorian Gray), for the death of the sister (Sibyl) parallels that of ]' vengeance against Prince Hamlet. | |||

| * Alan Campbell – chemist and one-time friend of Dorian who ended their friendship when Dorian's libertine reputation devalued such a friendship. Dorian blackmails Alan into destroying the body of the murdered Basil Hallward; Campbell later shoots himself dead. | |||

| * Lord Fermor – Lord Henry's uncle, who tells his nephew, Lord Henry Wotton, about the family ] of Dorian Gray. | |||

| * Adrian Singleton – A youthful friend of Dorian's, whom he evidently introduced to opium addiction, which induced him to forge a cheque and made him a total outcast from his family and social set. | |||

| * Victoria, Lady Henry Wotton – Lord Henry's wife, whom he treats disdainfully; she later divorces him. | |||

| == Major themes == | |||

| === Morality and societal influence === | |||

| Throughout the novel, Wilde delves into the themes of morality and influence, exploring how societal values, individual relationships, and personal choices intersect to shape one's own moral compass. Dorian initially falls under Lord Henry's influence and "narcissistic perspective on art and life", despite Basil's warnings, but "eventually recognizes its limitations".<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Manganiello |first=Dominic |date=1983 |title=Ethics and Aesthetics in "The Picture of Dorian Gray" |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/25512571 |journal=The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies |volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=25–33 |jstor=25512571 |issn=0703-1459}}</ref> Through Lord Henry's dialogue, Wilde is suggesting, as professor Dominic Manganiello pointed out, that creating art enacts the innate ability to conjure criminal impulses.<ref name=":1" /> Dorian's immersion in the elite social circles of Victorian London exposes him to a culture of superficiality and moral hypocrisy.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last=Liebman |first=Sheldon W. |date=1999 |title=Character Design in "the Picture of Dorian Gray" |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/29533343 |journal=Studies in the Novel |volume=31 |issue=3 |pages=296–316 |jstor=29533343 |issn=0039-3827}}</ref> Supporting this idea, Sheldon W. Liebman offered the example of Wilde's inclusion of a great psychological intellect held by Lord Henry. Before Sybil's death, Henry was also a firm believer in vanity as the origin of a human being's irrationality.<ref name=":2" /> This concept is broken for Henry after Sybil is found dead, the irony being that Dorian is the cause of her death and his motives are exactly as Lord Henry has taught them to him.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| The novel presents other relationships that influence Dorian's way of life and his perception of the world, proving the influence of society and its values on a person. While Lord Henry is clearly a persona that fascinates and captures Dorian's attention, Manganiello also suggests that Basil is also a person that may "evoke a change of heart" in Dorian.<ref name=":1" /> However, at this point in the novel, Dorian has spent far too much time under Lord Henry's wing and brushes Basil off in "appositeness", leading Basil to claim that man has no soul but art does.<ref name=":1" /> Dorian's journey serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of succumbing to the temptations of hedonism and moral relativism, highlighting the importance of personal responsibility and moral accountability in navigating the complexities of human existence.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| In his preface, Wilde writes about ], a character from Shakespeare's play '']''. When Dorian is telling Lord Henry Wotton about his new 'love', Sibyl Vane, he refers to all of the Shakespearean plays she has been in, referring to her as the heroine of each play. At a later time, he speaks of his life by quoting ], who has similarly driven his girlfriend to suicide and her brother to swear revenge. | |||

| === |

=== Homoeroticism and gender roles === | ||

| The novel's representation of ] is subtle yet present by manifesting itself through interactions between male characters in a way that challenges the strict social norms of ] ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Muriqi |first=Luljeta |title=Homoerotic codes in The Picture of Dorian Gray |url=https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=1366551&fileOId=1366552 |journal=Lund University}}</ref> The novel begins with a conversation between Lord Henry and Basil, where Basil reveals his artistic admiration for Dorian, setting the scene for a story with themes such as beauty, art, and the consequences of vanity. The interaction introduces the characters and foreshadows the complicated relationship between the artist and his muse.<ref name="gutenberg_20_1" /> | |||

| It has been noted by scholars that Wilde possibly chose the protagonist's name, Dorian, in reference to the ] of ], argued to have been the first to introduce male same-sex initiation rituals to ancient Greek culture, being an allusion to ].<ref name="Campman">{{Cite journal |last=Campman |first=Lotte |title=Greek Love and Love for All Things Greek: Gay Subtext and Greek Intertext in Works by Oscar Wilde |url=https://studenttheses.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12932/19697/Campman,%20Lotte.%20MA%20Thesis.pdf |journal=Utrecht University}}</ref> | |||

| Dorian Gray's "poisonous French novel" that leads to his downfall is believed to be ]' novel '']''. Literary critic ] writes:<blockquote>Wilde does not name the book but at his trial he conceded that it was, or almost, Huysmans's ''A Rebours''...To a correspondent he wrote that he had played a 'fantastic variation' upon ''A Rebours'' and some day must write it down. The references in ''Dorian Gray'' to specific chapters are deliberately inaccurate.<ref>Ellmann, Oscar Wilde (Vintage, 1988) p.316</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Similarly, ]s influence the relationships between characters and form their expectations and behaviors; in particular, the expectations of masculinity and the critique of the Victorian ideal of manhood are seen throughout the narrative.<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal |last=Brias Aliaga |first=Nuria |title=Femininity and Female Presence in Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray |url=https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/170821/1/BRIAS%20ALIAGA%2C%20Nu%CC%81ria%20TFG.pdf |journal=University of Barcelona}}</ref> Dorian, with his eternal youth and beauty, challenges traditional male roles and the slow decay of his portrait reflects the deception of societal expectations. Additionally, the few female characters in the story, such as Sybil, are portrayed in ways that critique the limited roles and harsh judgments reserved for women during that era.<ref name=":3" /> The novel's exploration of these themes provides commentary on the structures of Victorian society, revealing the performative side of gender roles that restrict and define both men and women.<ref name="gutenberg_20_1" /><ref name=":3" /> | |||

| == Literary significance == | |||

| ==Influences and allusions== | |||

| ] | |||

| ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' began as a short novel submitted to ]. In 1889, J. M. Stoddart, a proprietor for Lippincott, was in London to solicit short novels for the magazine. Wilde submitted the first version of ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'', which was published on 20 June 1890 in the July edition of Lippincott's. There was a delay in getting Wilde's work to press while numerous changes were made to the novel (several manuscripts of which survive). Some of these changes were made at Wilde's instigation, and some at Stoddart's. Wilde removed all references to the fictitious book "Le Secret de Raoul", and to its fictitious author, Catulle Sarrazin. The book and its author are still referred to in the published versions of the novel, but are unnamed. | |||

| === Wilde's own life === | |||

| Wilde also attempted to moderate some of the more ] instances in the book, or instances whereby the intentions of the characters may be misconstrued. In the 1890 edition, Basil tells Henry how he "worships" Dorian, and begs him not to "take away the one person that makes my life absolutely lovely to me." The focus for Basil in the 1890 edition seems to be more towards love, whereas the Basil of the 1891 edition cares more for his art, saying "the one person who gives my art whatever charm it may possess: my life as an artist depends on him." The book was also extended greatly: the original thirteen chapters became twenty, and the final chapter was divided into two new chapters. The additions involved the "fleshing out of Dorian as a character" and also provided details about his ancestry, which helped to make his "psychological collapse more prolonged and more convincing."<ref name="DorianGray ANoteOnTheText">''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) - A Note on the Text</ref> The character of James Vane was also introduced, which helped to elaborate upon Sibyl Vane's character and background; the addition of the character helped to emphasise and foreshadow Dorian's selfish ways, as James sees through Dorian's character, and guesses upon his future dishonourable actions (the inclusion of James Vane's sub-plot also gives the novel a more typically Victorian tinge, part of Wilde's attempts to decrease the controversy surrounding the book). Another notable change is that in the latter half of the novel events were specified as taking place around Dorian Gray's 32nd birthday, on 7 November. After the changes, they were specified as taking place around Dorian Gray's 38th birthday, on 9 November, thereby extending the period of time over which the story occurs. The former date is also significant in that it coincides with the year in Wilde's life during which he was introduced to homosexual practices. | |||

| Wilde wrote in an 1894 letter:<ref>{{Cite web|title=Your handwriting fascinates me and your praise charms me|url=https://natlib.govt.nz/blog/posts/your-handwriting-fascinates-me-and-your-praise-charms-me|access-date=2021-10-24|website=natlib.govt.nz|language=en-nz}}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote| contains much of me in it – Basil Hallward is what I think I am; Lord Henry, what the world thinks me; Dorian is what I would like to be – in other ages, perhaps.<ref name="LawlerKnott"/><ref name="The Modern Library Gray">{{cite web|url=http://www.randomhouse.com/catalog/display.pperl?isbn=9780553901672 |title=The Picture of Dorian Gray|publisher=The Modern Library|archive-url=https://archive.today/20130131232027/http://www.randomhouse.com/book/190563/the-picture-of-dorian-gray-by-oscar-wilde/9780553901672/|archive-date=2013-01-31}}</ref>}} | |||

| Hallward is supposed to have been formed after painter ].<ref name="wildean">{{cite journal|author=Schwab, Arnold, T.|year=2010|title=Symons, Gray, and Wilde: A Study in Relationships|journal=The Wildean|publisher=|issue=36|pages=2–27|jstor=45270165}}</ref> Scholars generally accept that Lord Henry is partly inspired by Wilde's friend ].<ref name="wildean" /><ref>Wilde, Oscar; Frankel, Nichols (ed.) ''The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition'' The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, London 2011, p. 68</ref> It was purported that Wilde's inspiration for Dorian Gray was the poet ],<ref name="wildean" /> but Gray distanced himself from the rumour.<ref>{{cite web|first=Jeanie|last=Riess|date=2012-09-13|title=Ten Famed Literary Figures Based on Real-Life People|url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/Ten-Famed-Literary-Figures-Based-On-Real-Life-People-169666976.html|access-date=2012-10-03|work=]|archive-date=5 December 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131205132908/http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/Ten-Famed-Literary-Figures-Based-On-Real-Life-People-169666976.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> Some believe that Wilde used ] in creating ''Dorian Gray''.<ref>], ''Whistler and Montesquiou: The Butterfly and the Bat'', New York and Paris: The ]/], 1995, p. 13.</ref> | |||

| === |

===''Faust''=== | ||

| Wilde is purported to have said, "in every first novel the hero is the author as Christ or ]."<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3YO-uQEACAAJ|title=The Picture of Dorian Gray |publisher=Magnum Books |date=1969 |first=Oscar |last=Wilde |access-date=30 May 2011}}</ref><ref name="britannica">{{cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/art/Irish-literature/Shaw-and-Wilde|title=Shaw and Wilde|publisher=Britannica|access-date=2020-09-08}}</ref> In both the legend of ''Faust'' and in ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' a temptation (ageless beauty) is placed before the protagonist, which he indulges. In each story, the protagonist entices a beautiful woman to love him, and then destroys her life. In the preface to the novel, Wilde said that the notion behind the tale is "old in the history of literature", but was a thematic subject to which he had "given a new form".<ref name="DorianGray Preface">''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) – Preface</ref> | |||

| Unlike the academic ''Faust'', the gentleman Dorian makes no ], who is represented by the cynical hedonist Lord Henry, who presents the temptation that will corrupt the ] and innocence that Dorian possesses at the start of the story. Throughout, Lord Henry appears unaware of the effect of his actions upon the young man; and so frivolously advises Dorian, that "the only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing."<ref name="DorianGray Chapter II">''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Penguin Classics) – Chapter II</ref> As such, the devilish Lord Henry is "leading Dorian into an unholy pact, by manipulating his innocence and insecurity."<ref name="Devil's Advocate"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090207212634/http://education.yahoo.com/homework_help/cliffsnotes/the_picture_of_dorian_gray/10.html |date=7 February 2009}} – a summary of and a commentary on Chapter II of ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (retrieved 29 July 2006)</ref> | |||

| The preface to ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' was added, along with other amendments, after the edition published in ] was criticised. Wilde used it to address the criticism and defend the novel's reputation.<ref name="Preface Quote"> - a summary and analysis of the book and its preface (retrieved 5 July 2006)</ref> It consists of a collection of statements about the role of the artist, art itself, the value of beauty, and serves as an indicator of the way in which Wilde intends the novel to be read, as well as traces of Wilde's exposure to ] and the writings of the Chinese Daoist philosopher ]. Shortly before writing the preface, Wilde reviewed ] translation of the writings of Zhuangzi.<ref name="Speaker I:6">The Preface first appeared with the publication of the novel in 1891. But by June of 1890 Wilde was defending his book (see ''The Letters of Oscar Wilde''], Merlin Holland and ] eds., Henry Holt (2000), ISBN 0-8050-5915-6 and ''The Artist as Critic'', ed. ], University of Chicago (1968), ISBN 0-226-89764-8 — where Wilde's review of Giles's translation is incorrectly identified with ].) Wilde's review of Giles's translation was published in ''The Speaker'' of 8 February 1890.</ref> In it he writes: | |||

| {{wikiquotepar|The Picture of Dorian Gray}} | |||

| <blockquote>The honest ratepayer and his healthy family have no doubt often mocked at the dome-like forehead of the philosopher, and laughed over the strange perspective of the landscape that lies beneath him. If they really knew who he was, they would tremble. For Chuang Tsǔ spent his life in preaching the great creed of Inaction, and in pointing out the uselessness of all things.<ref name="Artist as Critic 222">Ellmann, ''The Artist as Critic'', 222.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| === |

===Shakespeare=== | ||

| In the preface, Wilde speaks of the sub-human ] character from '']''. In chapter seven, when he goes to look for Sibyl but is instead met by her manager, he writes: "He felt as if he had come to look for Miranda and had been met by Caliban". | |||

| When Dorian tells Lord Henry about his new love Sibyl Vane, he mentions the Shakespeare plays in which she has acted, and refers to her by the name of the heroine of each play. In the 1891 version, Dorian describes his portrait by quoting '']'',{{efn|The reference is in chapter 19. Lord Henry asks "By the way, what has become of that wonderful portrait did of you?" Dorian's response, a few lines later, includes 'I am sorry I sat for it. The memory of the thing is hateful to me. Why do you talk of it? It used to remind me of those curious lines in some play—"Hamlet," I think—how do they run?—<br> "''Like the painting of a sorrow,''<br>''A face without a heart.''"<br>Yes: that is what it was like.'<ref>{{Cite book |title=The Picture of Dorian Gray |last=Wilde |first=Oscar |date=2008|publisher=] |isbn=9780199535989 |page=180 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A3ZclynrChAC&pg=PA180 |editor-last=Bristow |editor-first=Joseph |series=Oxford World's Classics |orig-date=1891}}</ref>}} in which the eponymous character impels his potential suitor (]) to madness and possibly suicide, and Ophelia's brother (Laertes) to swear mortal revenge. | |||

| Overall, initial critical reception of the book was poor, with the book gaining "certain notoriety for being 'mawkish and nauseous,' 'unclean,' 'effeminate,' and 'contaminating.'"<ref name="The Modern Library"> - a synopsis of the book coupled with a short biography of Oscar Wilde (retrieved 6 July 2006)</ref> This had much to do with the novel's ] overtones, which caused something of a sensation amongst Victorian critics when first published. A large portion of the criticism was levelled at Wilde's perceived ], and its distorted views of conventional morality. The ''Daily Chronicle'' of 30 June 1890 suggests that Wilde's novel contains "one element...which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it." The ''Scots Observer'' of 5 July 1890 asks why Wilde must "go grubbing in muck-heaps?” Wilde responded to such criticisms by curtailing some of the homoerotic overtones, and by adding six chapters to the book in an effort to add background.<ref name="Addition"> - an introduction and overview the book (retrieved 5 July 2006)</ref> | |||

| ===Joris-Karl Huysmans=== | |||

| === Major changes in the 1891 version from the 1890 first edition === | |||

| The anonymous "poisonous French novel" that leads Dorian to his fall is a thematic variant of '']'' (1884), by ]. In the biography ''Oscar Wilde'' (1989), the literary critic ] said: <blockquote>Wilde does not name the book, but at his trial he conceded that it was, or almost , Huysmans's ''À rebours'' ... to a correspondent, he wrote that he had played a "fantastic variation" upon ''À rebours'', and someday must write it down. The references in ''Dorian Gray'' to specific chapters are deliberately inaccurate.<ref>{{cite book|first= Richard|last= Ellmann|title=Oscar Wilde|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KF7GTFAuIQ8C|publisher=Vintage Books|year= 1988|page=316|isbn=9780394759845}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ===Possible Disraeli influence=== | |||

| The 1891 version was expanded from 13 to 20 chapters, but also toned down, particularly in some of its too overtly homoerotic aspects. Also, chapters 3, 5, and 15 to 18 are entirely new in the 1891 version, and chapter 13 from the first edition is split in two (becoming chapters 19 and 20). | |||

| Some commentators have suggested that ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' was influenced by the British Prime Minister ]'s (anonymously published) first novel '']'' (1826), as "a kind of homage from one outsider to another".<ref>{{cite news|last1=McCrum|first1=Robert|date=2 December 2013|title=The 100 best novels: No 11 – Sybil by Benjamin Disraeli (1845)|newspaper=The Guardian|publisher=Guardian News and Media Limited|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/dec/02/sybil-benjamin-disraeli-100-best-novels|access-date=6 June 2016}}</ref> The name of Dorian Gray's love interest, Sibyl Vane, may be a modified fusion of the title of Disraeli's best known novel ('']'') and Vivian Grey's love interest Violet Fane, who, like Sibyl Vane, dies tragically.<ref name="Disraeli (1853)">{{cite book|last1=Disraeli|first1=Benjamin|title=Vivian Grey|date=1826|publisher=Longmans, Green and Co|edition=1853 version|location=London|pages=263–265}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Clausson, Nils|year=2006|title=Lady Alroy's Secret: 'Surface and Symbol' in Wilde's 'The Sphinx without a Secret'|journal=The Wildean|issue=28|pages=24–32|jstor=45269274}}</ref> There is also a scene in ''Vivian Grey'' in which the eyes in the portrait of a "beautiful being" move when its subject dies.<ref>Disraeli (1853) pp. 101–102</ref> | |||

| At his ] Wilde testified that some of these changes were because of letters sent to him by ]. <ref>Lawler, Donald L., An Inquiry into Oscar Wilde's Revisions of 'The Picture of Dorian Gray' (New York: Garland, 1988)</ref> | |||

| == Reactions == | |||

| ==== Deleted or moved passages ==== | |||

| === Contemporary response === | |||

| * (Basil about Dorian) ''He has stood as Paris in dainty armor, and as Adonis with huntsman's cloak and polished boar-spear. Crowned with heavy lotus-blossoms, he has sat on the prow of Adrian's barge, looking into the green, turbid Nile. He has leaned over the still pool of some Greek woodland, and seen in the water's silent silver the wonder of his own beauty.'' (This passage turns up in Basil's speech to Dorian in the 1891 version.) | |||

| Even after the removal of controversial text, ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' offended the moral sensibilities of British book reviewers, to the extent, in some cases, of saying that Wilde merited prosecution for violating ]. | |||

| * (Lord Henry about fidelity) ''It has nothing to do with our own will. It is either an unfortunate accident, or an unpleasant result of temperament.'' | |||

| * ''"You don't mean to say that Basil has got any passion or any romance in him?" / "I don't know whether he has any passion, but he certainly has romance," said Lord Henry, with an amused look in his eyes. / "Has he never let you know that?" / "Never. I must ask him about it. I am rather surprised to hear it.'' | |||

| * (describing Basil Hallward) ''Rugged and straightforward as he was, there was something in his nature that was purely feminine in its tenderness.'' | |||

| * (Basil to Dorian) ''It is quite true that I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man usually gives to a friend. Somehow, I had never loved a woman. I suppose I never had time. Perhaps, as Harry says, a really ''grande passion'' is the privilege of those who have nothing to do, and that is the use of the idle classes in a country.'' (the latter remark being part of Lord Henry's dialogue in the 1891 version) | |||

| * Some dialogue between Mrs Leaf and Dorian has been cut, which mentions Dorian's fondness for "jam" (which might have been used metaphorically for his sexuality). | |||

| * When Basil confronts Dorian: ''Dorian, Dorian, your reputation is infamous. I know you and Harry are great friends. I say nothing about that now, but surely you need not have made his sister's name a by-word.'' (That part has been deleted in the 1891 version, and the passage after that has been added.) | |||

| In the 30 June 1890 issue of the '']'', the book critic said that Wilde's novel contains "one element ... which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it." In the 5 July 1890 issue of the '']'', a reviewer asked "Why must Oscar Wilde 'go grubbing in muck-heaps?'" The book critic of ''The Irish Times'' said, ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' was "first published to some scandal."<ref>{{cite news|last=Battersby|first=Eileen|date=7 April 2010|title=Wilde's Portrait of Subtle Control|newspaper=Irish Times|url=http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?hid=111&sid=854409f9-be37-4c57-9f99-5ca010d27ef7%40sessionmgr114&vid=4&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=n5h&AN=9FY4146686689|url-status=dead|access-date=9 March 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181005163101/http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?hid=111&sid=854409f9-be37-4c57-9f99-5ca010d27ef7%40sessionmgr114&vid=4&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=n5h&AN=9FY4146686689|archive-date=5 October 2018}}</ref> Such book reviews achieved for the novel a "certain notoriety for being 'mawkish and nauseous', 'unclean', 'effeminate' and 'contaminating'."<ref name="The Modern Library"> – a synopsis of the novel and a short biography of Oscar Wilde. (retrieved 6 July 2006)</ref> Such ] scandal arose from the novel's ], which offended the sensibilities (social, literary, and aesthetic) of Victorian book critics. Most of the criticism was, however, personal, attacking Wilde for being a hedonist with values that deviated from the conventionally accepted morality of Victorian Britain. | |||

| ==== Added passages ==== | |||

| In response to such criticism, Wilde aggressively defended his novel and the sanctity of art in his correspondence with the British press. Wilde also obscured the homoeroticism of the story and expanded the personal background of the characters in the 1891 book edition.<ref name="Addition"> – an introduction and overview the book (retrieved 5 July 2006) {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120319200835/http://www.cliffsnotes.com/WileyCDA/LitNote/id-144,pageNum-2.html|date=19 March 2012}}</ref> | |||

| * ''Each class would have preached the importance of those virtues, for whose exercise there was no necessity in their own lives. The rich would have spoken on the value of thrift, and the idle grown eloquent over the dignity of labour.'' | |||

| * ''A ''grande passion'' is the privilege of people who have nothing to do. That is the one use of the idle classes of a country. Don't be afraid.'' | |||

| * ''Faithfulness! I must analyze it some day. The passion for property is in it. There are many things that we would throw away if we were not afraid that others might pick them up.'' | |||

| Due to controversy, retailing chain ], then Britain's largest bookseller,<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Picture of Dorian Gray as first published in Lippincott's Magazine |url=https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-picture-of-dorian-gray-as-first-published-in-lippincotts-magazine|access-date=2022-11-19|website=www.bl.uk}}</ref> withdrew every copy of the July 1890 issue of ''Lippincott's Monthly Magazine'' from its bookstalls in railway stations.<ref name="FrankelIntro" /> | |||

| == Adaptations and allusions == | |||

| {{Main|Adaptations of The Picture of Dorian Gray|Music based on the works of Oscar Wilde#The Picture of Dorian Gray}} | |||

| At Wilde's 1895 ], the book was called a "perverted novel" and passages (from the magazine version) were read during cross-examination.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Mikhail|first=E. H.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vCmuCwAAQBAJ|title=Oscar Wilde: Interviews and Recollections|year=1979|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-1-349-03926-5|pages=280–281|language=en}}</ref> The book's association with Wilde's trials further hurt the book's reputation. In the decade after Wilde's death in 1900, the authorized edition of the novel was published by ], who specialized in literary erotica. | |||

| ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' has been the subject of a great number of ]. In addition to full adaptations, it has also been the subject of a number of other allusions. | |||

| === Modern response === | |||

| * Dorian Gray was mentioned in the chorus of the song "Tears and Rain" by singer/songwriter ]. | |||

| The novel was considered a poorly written novel and unworthy of critical attention until about the 1980s. ] wrote that "parts of the novel are wooden, padded, self-indulgent"; ] held a similarly negative opinion about the novel. Afterwards, critics began to view is it as a masterpiece of Wilde's oeuvre.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Liebman |first1=Sheldon W. |title=Character Design in "the Picture of Dorian Gray" |journal=Studies in the Novel |date=1999 |volume=31 |issue=3 |pages=296–316 |jstor=29533343 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/29533343 |access-date=29 February 2024 |issn=0039-3827}}</ref> ] wrote of the book "it is exceptionally good – in fact, one of the strongest and most haunting of English novels", while noting that the reputation of the novel was still questionable.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Oates |first1=Joyce Carol |title="The Picture of Dorian Gray": Wilde's Parable of the Fall |journal=Critical Inquiry |date=1980 |volume=7 |issue=2 |pages=419–428 |doi=10.1086/448106 |jstor=1343135 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1343135 |access-date=29 February 2024 |issn=0093-1896}}</ref> | |||

| * British show ''],'' in the episode ''Rescue'' in season 4 features a plot loosely based on Dorian Gray | |||

| * '']'' used the novel as inspiration for its 129th episode '']'', where a diplomat exorcises his own negative feelings by transferring them into others, although this process causes them to rapidly age to death. | |||

| * '']'' episode "Age Before Duty," features a plot to murder agents by applying "Dorian Gray Paint on their photographs. | |||

| * '']'', an ] daytime drama (1966-1971), featured a storyline clearly inspired by Wilde's novel but renaming the main character Quentin Collins. | |||

| * It has been a favorite spoof of ] in ] including "The Picture of Dorian Cow" and "The Picture of Dorian Gray and his dog." | |||

| * Dorian Gray was featured as a character in the 2003 film ] as an eventual villian, having been blackmailed by the villain- revealed to be ]- to join the League and acquire samples from them that would allow Moriarty to replicate their abilities for his army. Dorian is eventually killed by the vampiric ] in a duel, when she pins him to the wall and shows him his portrait, thus negating the spell that made the picture age and causing him to disintegrate in front of her. | |||

| * The 1994-2001 ] series, '']'', created by ], featured a storyline based on ''Dorian Gray.'' In the story, "Hell and Back," ], a.k.a. Starman, is recruited by his immortal friend, ], to fight a supernatural villain named Merritt. The Shade tells Jack that many centuries ago, Merritt made a deal with the devil. In exchange for immortality, Merritt would murder people and send their mortal souls into Hell through a portal disguised as a carnival poster. Jack and The Shade enter the poster to free the souls trapped inside it. Later, The Shade tells Jack that Merritt and the carnival poster were the inspiration for ]'s novel. (In a flashback story, Oscar Wilde visits his friend The Shade in 19th century ], and witnesses The Shade's first battle with Merritt.) | |||

| In a 2009 review, critic Robin McKie considers the novel to be technically mediocre, saying that the conceit of the plot guaranteed its fame, but the device is never pushed to its full.<ref>McKie, Robin (25 January 2009). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130624195141/http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2009/jan/25/classics-picture-dorian-gray-wilde|date=24 June 2013}}. '']'' (London).</ref> On the other hand, in March 2014, ] of '']'' listed it among the 100 best novels ever written in English, calling it "an arresting, and slightly camp, exercise in late-Victorian ]".<ref name="guardian2">{{Cite news|last=McCrum|first=Robert|date=24 March 2014|title=The 100 best novels: No 27 – The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (1891)|work=]|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/24/100-best-novels-picture-dorian-gray-oscar-wilde|url-status=live|access-date=11 August 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180812053713/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/24/100-best-novels-picture-dorian-gray-oscar-wilde|archive-date=12 August 2018}}</ref> | |||

| == Editions == | |||

| ==Legacy and adaptations== | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'', Oneworld Classics 2008, ISBN 978-1-84749-018-6 | |||

| {{Main|Adaptations of The Picture of Dorian Gray|Music based on the works of Oscar Wilde#The Picture of Dorian Gray}} | |||

| ] as Sibyl Vane in the film adaptation ]. Lansbury was nominated for the ] for her performance.]] | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'', Penguin Classics 2006, ISBN 978-0141442037 | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'', Oxford World's Classics 2006, ISBN 978-0192807298 | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'', Barnes and Noble Classics 2003, ISBN 978-1-59308-025-9 | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'', Tor 1999, ISBN 0-812-56711-0 | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'', Wordsworth Classics 1992, ISBN 1853260150 | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'', Modern Library 1992, ISBN 978-0-679-60001-5 | |||

| Though not initially a widely appreciated component of Wilde's body of work following his death in 1900, ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' has come to attract a great deal of academic and popular interest, and has been the subject of many adaptations to film and stage. | |||

| == Footnotes and references == | |||

| In 1913, it was adapted to the stage by writer G. Constant Lounsbery at London's ].<ref name="owc-intro" /> In the same decade, it was the subject of several silent film adaptations. Perhaps the best-known and most critically praised film adaptation is 1945's '']'', which earned an Academy Award for best black-and-white cinematography, as well as a Best Supporting Actress nomination for ], who played Sibyl Vane. | |||

| <!--This section uses the Cite.php citation mechanism. If you would like more information on how to add references to this article, please see http://meta.wikimedia.org/Cite/Cite.php --> | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| In 2003, ] played Dorian Gray in the film '']''. In 2009, the novel was loosely adapted into the film ], starring ] as Dorian and ] as Lord Henry. | |||

| == See also == | |||

| ] played the character in a series of audio dramas scripted by ] in 2013.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bigfinish.com/releases/v/the-picture-of-dorian-gray-927?range=68 |title=3. The Picture of Dorian Gray - The Confessions of Dorian Gray |publisher=Big Finish |date= |accessdate=2016-02-07}}</ref> | |||

| {{Oscar Wilde portal}} | |||

| ] portrays Dorian Gray in John Logan's '']'', which aired on Showtime from 2014 to 2016. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| The ]<ref> Retrieved February 19th, 2023</ref> is named in honor of Wilde, in reference to ''The Picture of Dorian Gray''; the original award was a simple certificate with an image of Wilde along with a graphic of hands holding a black ].<ref>] Retrieved November 29, 2017</ref> The first Dorian Awards were announced in January 2010 (nominees were revealed the previous month).<ref>'']'', January 20, 2010, by Lisa Horowitz, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160307200020/http://www.thewrap.com/deal-central/article/single-man-glee-grey-gardens-top-dorian-awards-13272/ |date=7 March 2016 }}</ref> | |||

| == External links == | |||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| {{wikisource}} | |||

| Editions include: | |||

| * ''The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, Vol. 3: The Picture of Dorian Gray: The 1890 and 1891 Texts'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). Critical edition in the Oxford English Texts edition of Wilde's Complete Works, edited with an introduction and notes by ]. | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (]: ], 2008) {{ISBN|9780199535989}}. Edited with an introduction and notes by Joseph Bristow, based on the 1891 text as presented in the 2005 OET edition. | |||

| * ''The Uncensored Picture of Dorian Gray'' (], 2011) {{ISBN|9780674066311}}. Edited with an introduction by Nicholas Frankel. This edition presents the uncensored typescript of the 1890 magazine version. | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (]: ], 2006) {{ISBN|9780393927542}}. Edited with an introduction and notes by Michael Patrick Gillespie. Presents the 1890 magazine edition and the 1891 book edition side by side. | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (]: ], 2006), {{ISBN|9780141442037}}. Edited with an introduction and notes by ]. Included as an appendix is ]'s introduction to the 1986 Penguin Classics edition. It reproduces the 1891 book edition. | |||

| * ''The Picture of Dorian Gray'' (Broadview Press, 1998) {{ISBN|978-1-55111-126-1}}. Edited with an introduction and notes by Norman Page. Based on the 1891 book edition. | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Wikisource|The Picture of Dorian Gray|''The Picture of Dorian Gray''}} | |||

| {{wikiquote}} | {{wikiquote}} | ||

| {{Commons category}} | |||

| * Replica of the 1890 Edition at | |||

| * {{StandardEbooks|Standard Ebooks URL=https://standardebooks.org/ebooks/oscar-wilde/the-picture-of-dorian-gray}} | |||

| * at ] | |||

| * {{gutenberg|no=4078|name=The Picture of Dorian Gray (13-chapter version)}} | * {{gutenberg|no=4078|name=The Picture of Dorian Gray (13-chapter version)}} | ||

| * {{gutenberg|no=174|name=The Picture of Dorian Gray (20-chapter version)}} | * {{gutenberg|no=174|name=The Picture of Dorian Gray (20-chapter version)}} | ||

| * {{ |

* {{librivox book | title=The Picture of Dorian Gray | author=Oscar Wilde}} | ||

| * {{ISFDB title|id=13981}} | |||

| * Audioversion at | |||

| {{Oscar Wilde|state=collapsed}} | |||

| {{The Picture of Dorian Gray}} | |||

| {{Faust navbox}} | |||

| {{Portal bar|Literature|Theatre|Film|Opera|Novels}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Picture Of Dorian Gray, The}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Picture Of Dorian Gray, The}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 22:37, 4 January 2025

1890 novel by Oscar Wilde "Dorian Gray" redirects here. For the character, see Dorian Gray (character). For other uses, see Dorian Gray (disambiguation) and The Picture of Dorian Gray (disambiguation).

The story was first published in 1890 in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine The story was first published in 1890 in Lippincott's Monthly Magazine | |

| Author | Oscar Wilde |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Philosophical fiction, Gothic fiction, decadent literature |

| Published | 1890 Lippincott's Monthly Magazine |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 53071567 |

| Dewey Decimal | 823.8 |

| LC Class | PR5819.A2 |

| Text | The Picture of Dorian Gray at Wikisource |

The Picture of Dorian Gray is a philosophical fiction and gothic horror novel by Irish writer Oscar Wilde. A shorter novella-length version was published in the July 1890 issue of the American periodical Lippincott's Monthly Magazine. The novel-length version was published in April 1891. It is regarded as a classic of Gothic literature and has been adapted for films and stage performances.

The story revolves around a portrait of Dorian Gray painted by Basil Hallward, a friend of Dorian's and an artist infatuated with Dorian's beauty. Through Basil, Dorian meets Lord Henry Wotton and is soon enthralled by the aristocrat's hedonistic worldview: that beauty and sensual fulfilment are the only things worth pursuing in life. Newly understanding that his beauty will fade, Dorian expresses the desire to sell his soul, to ensure that the picture, rather than he, will age and fade. The wish is granted, and Dorian pursues a libertine life of varied amoral experiences while staying young and beautiful; all the while, his portrait ages and visually records every one of Dorian's sins.

Wilde's only novel, it was subject to much controversy and criticism in its time but has come to be recognised as a classic of Gothic literature.

Origins

In 1882, Oscar Wilde met Frances Richards in Ottawa, where he visited her studios. In 1887, Richards moved to London where she renewed her acquaintance with Wilde and painted his portrait. Wilde described that incident as being the inspiration for the novel:

In December, 1887, I gave a sitting to a Canadian artist who was staying with some friends of hers and mine in South Kensington. When the sitting was over, and I had looked at the portrait, I said in jest, 'What a tragic thing it is. This portrait will never grow older and I shall. If it was only the other way!' The moment I had said this it occurred to me what a capital plot the idea would make for a story. The result is 'Dorian Gray.'