| Revision as of 17:49, 5 December 2001 view sourceDmerrill (talk | contribs)0 edits additional tweak on capitalization, explaining why it is done. Let's try to follow this guideline -- I think it makes sense and is npov. some reorganization by importance← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:53, 20 December 2024 view source Heyaaaaalol (talk | contribs)244 editsm added padlock | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Principal object of faith in monotheism}} | |||

| The word '''god''' refers to an immortal supernatural being with great powers. Most religions believe in some kind of God or gods, but these conceptions vary widely. | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{About|the supreme being in monotheistic belief systems|powerful supernatural beings considered divine or sacred|Deity|God in specific religions|Conceptions of God|other uses}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2019}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | footer = Left to right, top to bottom: representations of God in ], ], ], ], ], and ] | |||

| | perrow = 2 | |||

| | total_width = 300 | |||

| | image1 = Michelangelo, Creation of Adam 06.jpg | |||

| | image2 = Istanbul, Hagia Sophia, Allah.jpg | |||

| | image3 = Tetragrammaton Sefardi.jpg | |||

| | image4 = 051907 Wilmette IMG 1404 The Greatest Name.jpg | |||

| | image5 = Naqshe Rostam Darafsh Ordibehesht 93 (35).JPG | |||

| | image6 = Vishnu Kumartuli Park Sarbojanin Arnab Dutta 2010.JPG | |||

| }} | |||

| In ] belief systems, '''God''' is usually viewed as the supreme being, ], and principal object of ].<ref name="Swinburne"/> In ] belief systems, ] is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the ] or life, for which such a deity is often worshipped".<ref>{{multiref | {{Cite dictionary |entry=god |dictionary=Cambridge Dictionary}} | {{Cite dictionary |entry=God |dictionary=Merriam-Webster English Dictionary |archive-date=20 February 2023 |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/god |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230220102221/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/god |url-status=live}} }}</ref> Belief in the existence of at least one god is called ].<ref>{{multiref | {{Cite dictionary |entry=Theism |url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/theism |access-date=2023-11-13 |dictionary=Dictionary.com |archive-date=2 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231202194557/https://www.dictionary.com/browse/theism? |url-status=live}} | {{Cite dictionary |entry=Theism |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/theism |access-date=2023-11-13 |dictionary=Merriam-Webster English Dictionary |archive-date=14 May 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514194441/http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/theism |url-status=live}} }}</ref> | |||

| The word is usually capitalized when used in reference to a specific god or gods, i.e., the Christian God, particularly when used by believers. When speaking about the general concept of a god, it is usually lowercased. Capitalization is a sign of respect. | |||

| ] vary considerably. Many notable theologians and philosophers have developed arguments for and against the ].<ref name="Plantinga" /> ] rejects the belief in any deity. ] is the belief that the existence of God is unknown or ]. Some theists view knowledge concerning God as derived from faith. God is often conceived as the greatest entity in existence.<ref name="Swinburne">{{Cite book |last=Swinburne |first=R. G. |author-link=Richard Swinburne |title=The Oxford Companion to Philosophy |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1995 |editor-last=Honderich |editor-first=Ted |editor-link=Ted Honderich |chapter=God}}</ref> God is often believed to be the cause of all things and so is seen as the creator, ], and ruler of the universe. God is often thought of as ] and ] of the material creation,<ref name="Swinburne" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Bordwell |first=David |title=Catechism of the Catholic Church |publisher=Continuum |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-860-12324-8 |pages=84}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Catechism of the Catholic Church |via=IntraText |url=https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P17.HTM |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130303003725/https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P17.HTM |archive-date=3 March 2013 |access-date=30 December 2016}}</ref> while ] holds that God is the universe itself. God is sometimes seen as ], while ] holds that God is not involved with humanity apart from creation. | |||

| == Beliefs about the Nature of God == | |||

| Some traditions attach spiritual significance to maintaining some form of relationship with God, often involving acts such as ] and ], and see God as the source of all ].<ref name="Swinburne" /> God is sometimes described without reference ], while others use terminology that is gender-specific. God is referred to by different ] depending on the language and cultural tradition, sometimes with different titles of God used in reference to God's various attributes. | |||

| Beliefs about the exact nature of the Divine, and the nature of the relationship between the Divine and humanity are defining elements of any particular religion, and the controversy about which religion holds the truth has endured from the beginning of history up to the present, and shows no sign of abating. | |||

| ==Etymology and usage== | |||

| There are a number of different theories about God. ] holds that God exists, and is actively involved in the affairs of the world; for a discussion of the meaning of "God" in this sense, see: ]. ] holds that while God exists, he does not intervene in the world beyond what was necessary for him to create it (no answering prayers or causing miracles). ] holds that there is only one God, while ] holds that there are many gods. ] and ] are somewhat in-between: Henotheism says that there are many gods, but one of them is supreme and the other ones are only ancillary and don't have the same level of "God-ness". | |||

| {{Main|God (word)|l1 = ''God'' (word)}} | |||

| ] bears the earliest known reference (840 BCE) to the Israelite God Yahweh.]] | |||

| The earliest written form of the Germanic word ''God'' comes from the 6th-century ] {{lang|la|]}}. The English word itself is derived from the ] *ǥuđan. The reconstructed ] form {{PIE|*ǵhu-tó-m}} was probably based on the root {{PIE|*ǵhau(ə)-}}, which meant either "to call" or "to invoke".<ref>The ulterior etymology is disputed. Apart from the unlikely hypothesis of adoption from a foreign tongue, the OTeut. "ghuba" implies as its preTeut-type either "*ghodho-m" or "*ghodto-m". The former does not appear to admit of explanation; but the latter would represent the neut. pple. of a root "gheu-". There are two Aryan roots of the required form ("*g,heu-" with palatal aspirate) one with meaning 'to invoke' (Skr. "hu") the other 'to pour, to offer sacrifice' (Skr "hu", Gr. χεηi;ν, OE "geotàn" Yete v). ].</ref> The Germanic words for ''God'' were originally ], but during the process of the ] of the ]s from their indigenous ], the words became a ].<ref name="BARNHART323">Barnhart, Robert K. (1995). ''The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology: the Origins of American English Words'', p. 323. ]. {{ISBN|0062700847}}.</ref> In English, capitalization is used when the word is used as a ], as well as for other names by which a god is known. Consequently, the capitalized form of ''god'' is not used for multiple gods or when used to refer to the generic idea of a ].<ref>]; "God n. ME < OE , akin to Ger gott, Goth guth, prob. < IE base *ĝhau-, to call out to, invoke > Sans havaté, (he) calls upon; 1. any of various beings conceived of as supernatural, immortal, and having special powers over the lives and affairs of people and the course of nature; deity, esp. a male deity: typically considered objects of worship; 2. an image that is worshiped; idol 3. a person or thing deified or excessively honored and admired; 4. in monotheistic religions, the creator and ruler of the universe, regarded as eternal, infinite, all-powerful, and all-knowing; Supreme Being; the Almighty" | |||

| : Question: Wouldn't henotheism be same as some forms of Greek or Roman polytheism, classical paganism? | |||

| </ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090419052813/http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/God |date=19 April 2009 }}; "God /gɒd/ noun: 1. the one Supreme Being, the creator and ruler of the universe. 2. the Supreme Being considered with reference to a particular attribute. 3. (lowercase) one of several deities, esp. a male deity, presiding over some portion of worldly affairs. 4. (often lowercase) a supreme being according to some particular conception: the God of mercy. 5. Christian Science. the Supreme Being, understood as Life, Truth, Love, Mind, Soul, Spirit, Principle. 6. (lowercase) an image of a deity; an idol. 7. (lowercase) any deified person or object. 8. (often lowercase) Gods, Theater. 8a. the upper balcony in a theater. 8b. the spectators in this part of the balcony."</ref> | |||

| The English word ''God'' and its counterparts in other languages are normally used for any and all conceptions and, in spite of significant differences between religions, the term remains an English translation common to all. | |||

| Monolatrism, on the other hand, supports a somewhat geographical view of gods: For the people believing in a monolatrist religion, there is only one God. Other gods exist, but they can only exert their power on other peoples and have no meaning for the followers of the One God. | |||

| '']'' means 'god' in Hebrew, but ] and ], God is also given a personal name, the ] YHWH, in origin possibly the name of an ] or ] deity, ].<ref name="Parke-Taylor2006">{{cite book |last1=Parke-Taylor |first1=G. H. |title=Yahweh: The Divine Name in the Bible |date=1 January 2006 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0889206526 |page=4}}</ref> In many English translations of the ], when the word ''LORD'' is in all capitals, it signifies that the word represents the tetragrammaton.<ref name="Barton2006">{{cite book |author=Barton |first=G. A. |title=A Sketch of Semitic Origins: Social and Religious |publisher=Kessinger Publishing |year=2006 |isbn=978-1428615755}}</ref> ] or Yah is an abbreviation of Jahweh/Yahweh, and often sees usage by Jews and Christians in the interjection "]", meaning 'praise Jah', which is used to give God glory.<ref name="Loewen2020">{{cite book |last1=Loewen |first1=Jacob A. |title=The Bible in Cross Cultural Perspective |date=1 June 2020 |publisher=William Carey |isbn=978-1645083047 |page=182 |edition=Revised}}</ref> In ], some of the Hebrew titles of God are considered ]. | |||

| : Interesting! Please provide some examples, if possible. | |||

| {{tlit|ar|]}} ({{langx|ar|الله}}) is the Arabic term with no plural used by Muslims and Arabic-speaking Christians and Jews meaning 'the God', while {{tlit|ar|]}} ({{lang|ar|إِلَٰه}}, plural {{tlit|ar|`āliha}} {{lang|ar|آلِهَة}}) is the term used for a deity or a god in general.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pbs.org/empires/islam/faithgod.html |title=God |work=Islam: Empire of Faith |publisher=PBS |access-date=18 December 2010 |archive-date=27 March 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140327034958/http://www.pbs.org/empires/islam/faithgod.html |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>"Islam and Christianity", ''Encyclopedia of Christianity'' (2001): Arabic-speaking ] and ]s also refer to God as ''Allāh''.</ref><ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Allah |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia of Islam Online |last=Gardet |first=L.}}</ref> ] also use a ] for God. | |||

| Jews, Muslims and some Christians are unitarian monotheists, while most Christians are trinitarian monotheists. Trinitarian monotheists believe in one God, but believe that this one God exists as three distinct persons who share one divine essence; this belief is called the ]. Unitarian monotheists by contrast believe there to be only one person in God; they consider trinitarianism to be in reality a form of tri-theism, not monotheism. Many unitarian monotheists (many Muslims, a few Jews) do not view trinitarianism as monotheism. ] hold that the trinity is made of three separate gods, one of whom is a spirit, and two of whom live on other planets in our galaxy; they hold that by following Church rule, human men can literally become gods of their own planet. This belief is mainly held in the largest Mormon branch, the ]. | |||

| In ], ] is often considered a ] concept of God.<ref>Levine, Michael P. (2002). ''Pantheism: A Non-Theistic Concept of Deity'', p. 136.</ref> God may also be given a proper name in monotheistic currents of Hinduism which emphasize the ], with early references to his name as ]-] in ] or later ] and ].<ref name="Hastings541">{{Harvnb|Hastings|1925–2003|p=540|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Kaz58z--NtUC&pg=PA540&vq=Krishna&cad=1_1}}.</ref> ] is the term used in ].<ref>McDaniel, June (2013), A Modern Hindu Monotheism: Indonesian Hindus as 'People of the Book'. The Journal of Hindu Studies, Oxford University Press, {{doi|10.1093/jhs/hit030}}.</ref> | |||

| ] holds that the ] is God, while ] holds that the God contains but is not identical to the Universe. ], Jewish mysticism, paints a panentheistic view of God, and this view of God is widely accepted in Chasidic Judaism. ] is the belief that spirits exist in animals, plants, land features, etc. | |||

| In ], ] is conceived as the ] of the universe, intrinsic to it and constantly bringing order to it. | |||

| ] holds that no gods exist at all, while ] holds that God or gods may or may not exist, but we cannot know. ] holds that the word 'God' is (cognitively) meaningless. | |||

| ] is the name for God used in ]. "Mazda", or rather the Avestan stem-form ''Mazdā-'', nominative ''Mazdå'', reflects Proto-Iranian ''*Mazdāh (female)''. It is generally taken to be the proper name of the spirit, and like its ] cognate {{tlit|sa|medhā}} means 'intelligence' or 'wisdom'. Both the Avestan and Sanskrit words reflect ] ''*mazdhā-'', from ] mn̩sdʰeh<sub>1</sub>, literally meaning 'placing (''dʰeh<sub>1</sub>'') one's mind (''*mn̩-s'')', hence 'wise'.{{Sfn|Boyce|1983|p=685}} Meanwhile ] are also in use.<ref>Kidder, David S.; Oppenheim, Noah D. The Intellectual Devotional: Revive Your Mind, Complete Your Education, and Roam confidently with the cultured class, p. 364.</ref> | |||

| === Western Monotheistic Concept of God === | |||

| ] ({{langx|pa|{{IAST|vāhigurū}}}}) is a term most often used in ] to refer to God.<ref>Duggal, Kartar Singh (1988). ''Philosophy and Faith of Sikhism'', p. ix.</ref> It means 'Wonderful Teacher' in the Punjabi language. ''Vāhi'' (a ] borrowing) means 'wonderful', and '']'' ({{langx|sa|{{IAST|guru}}}}) is a term denoting 'teacher'. Waheguru is also described by some as an experience of ecstasy which is beyond all description. The most common usage of the word ''Waheguru'' is in the greeting Sikhs use with each other—''Waheguru Ji Ka Khalsa, Waheguru Ji Ki Fateh'', "Wonderful Lord's ], Victory is to the Wonderful Lord." | |||

| In the ], <b>God</b> (usually capitalized) is especially used to refer to the single such being held to rule over the universe. | |||

| ''Baha'', the "greatest" name for God in the ], is Arabic for "All-Glorious".<ref>Baháʾuʾlláh, Joyce Watanabe (2006). A Feast for the Soul: Meditations on the Attributes of God : ... p. x.</ref> | |||

| There is an ancient monotheistic tradition that began with the first ] of ], ], and ], ] (or instead, for believers, that began with ]), according to which there is one God, a ] that (or who) is the CreatorOfTheWorld and possesses the superhuman qualities of ] (being all-powerful), ] (being all-knowing), and (according to the majority of ]) a concept which might be called ] (being all-loving). This basic concept is shared by ], ] and ], though, of course, it is much embellished by each religion and sects within each religion. | |||

| Other names for God include ]<ref>Assmann, Jan. ''Religion and Cultural Memory: Ten Studies'', Stanford University Press 2005, p. 59.</ref> in ancient Egyptian ] where Aten was proclaimed to be the one "true" supreme being and creator of the universe,<ref>] (1980). ''Ancient Egyptian Literature'', Vol. 2, p. 96.</ref> ] in ],<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Afigbo |first1=A. E |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/61361536 |title=Myth, history and society: the collected works of Adiele Afigbo |last2=Falola |first2=Toyin |date=2006 |publisher=Africa World Press |isbn=978-1592214198 |location=Trenton, New Jersey |language=En-us |oclc=61361536 |access-date=11 March 2023 |archive-date=23 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240523094823/https://search.worldcat.org/title/61361536 |url-status=live}}</ref> and ] in ].<ref name="Buckley 2002">{{cite book |last=Buckley |first=Jorunn Jacobsen |title=The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2002 |isbn=0195153855 |publication-place=New York |oclc=65198443}}</ref><ref name=Nashmi>{{Citation |last=Nashmi |first=Yuhana |title=Contemporary Issues for the Mandaean Faith |website=Mandaean Associations Union |date=24 April 2013 |url=http://www.mandaeanunion.com/history-english/item/488-mandaean-faith |access-date=28 December 2021 |archive-date=31 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211031155605/http://www.mandaeanunion.com/history-english/item/488-mandaean-faith |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| A number of ] have been offered; an argument for the thesis that God does ''not'' exist is ], with the project of ] as a response. | |||

| ==General conceptions== | |||

| === The Ultimate === | |||

| ===Existence=== | |||

| Arguably, Eastern conceptions of ] (this, too, has many different names) are not conceptions of the ''divine,'' though certain Western conceptions of what is at least ''called'' "God" (e.g., ] pantheistic conception and various kinds of ]) resemble Eastern conceptions of ]. | |||

| {{Main|Existence of God}} | |||

| {{See also|Theism|Atheism|Agnosticism}} | |||

| ] summed up ] as proofs for God's existence. Painting by ], 1476.]] | |||

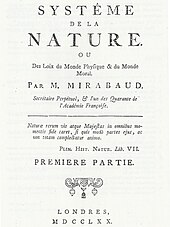

| ]'' (1770) argues that belief in God is based on fear, lack of understanding and ].]] | |||

| The existence of God is a subject of debate in ], ] and ].<ref>See e.g. ''The Rationality of Theism'' quoting ], "God is not 'dead' in academia; it returned to life in the late 1960s." They cite the shift from hostility towards theism in Paul Edwards's ''Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (1967) to sympathy towards theism in the more recent '']''.</ref> In philosophical terms, the question of the existence of God involves the disciplines of ] (the nature and scope of knowledge) and ] (study of the nature of ] or ]) and the ] (since some definitions of God include "perfection"). | |||

| === Gender of God === | |||

| ]s refer to any argument for the existence of God that is based on ''a priori'' reasoning.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ontological-arguments/ |title=Ontological Arguments |publisher=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |access-date=27 December 2022 |archive-date=25 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230525190107/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ontological-arguments/ |url-status=live}}</ref> Notable ontological arguments were formulated by ] and ].<ref>{{cite book |editor-last=Kreeft |editor-first=Peter |title=Summa of the Summa |year=1990 |publisher=Ignatius Press |pages=65–69 |first=Thomas |last=Aquinas}}</ref> ]s use concepts around the origin of the universe to argue for the existence of God. | |||

| The term God is traditionally used to refer to a deity of the male gender, a belief especially common in the ]. (], ] and ]). Traditionally the term used for a female deity is ], a term used today by such faiths as ] and ]. Others view the deity to be neither male nor female, in which case often God is used also. | |||

| The ], also called "argument from design", uses the complexity within the universe as a proof of the existence of God.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/teleological-arguments/ |entry=Teleological Arguments for God’s Existence |encyclopedia=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |orig-date=2005 |date=10 June 2005 |last1=Ratzsch |first1=Del |last2=Koperski |first2=Jeffrey |title=Teleological Arguments for God's Existence |access-date=30 December 2022 |archive-date=7 October 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191007141418/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/teleological-arguments/ |url-status=live}}</ref> It is countered that the ] required for a stable universe with life on earth is illusory, as humans are only able to observe the small part of this universe that succeeded in making such observation possible, called the ], and so would not learn of, for example, life on other planets or of ] that did not occur because of different ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/fine-tuning/ |title=Fine-Tuning |website=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |publisher=Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University |access-date=December 29, 2022 |date=Aug 22, 2017 |archive-date=10 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231010234820/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/fine-tuning/ |url-status=live}}</ref> Non-theists have argued that complex processes that have natural explanations yet to be discovered are referred to the supernatural, called ]. Other theists, such as ] who believed ] was acceptable, have also argued against versions of the teleological argument and held that it is limiting of God to view him having to only intervene specially in some instances rather than having complex processes designed to create order.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Chappell |first1=Jonathan |year=2015 |title=A Grammar of Descent: John Henry Newman and the Compatibility of Evolution with Christian Doctrine |journal=Science and Christian Belief |volume=27 |issue=2 |pages=180–206 |doi= |pmid= |bibcode=}}</ref> | |||

| Religions, and often different people within each religion, differ in what gender they believe God to be. One view, which is increasingly common today in Western religions, is that the deity is neither male nor female. This has also been the view of many within traditional Judaism and Christianity. | |||

| The ] states that this universe happens to contain special beauty in it and that there would be no particular reason for this over aesthetic neutrality other than God.<ref>{{cite book |author=Swinburne |first=Richard |title=The Existence of God |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2004 |isbn=978-0199271689 |edition=2nd |pages=190–91}}</ref> This has been countered by pointing to the existence of ugliness in the universe.<ref>{{cite book |title=The existence of God |publisher=Watts & Co. |page=75 |edition=1}}</ref> This has also been countered by arguing that beauty has no objective reality and so the universe could be seen as ugly or that humans have made what is more beautiful than nature.<ref>''Minority Report'', H. L. Mencken's Notebooks, Knopf, 1956.</ref> | |||

| In Judaism it is a fundamental heresy to say that God has a gender; nonetheless, most of the names for God used by Jews are masculine. Most Orthodox and many Conservative Jews argue that it would be wrong to apply female pronouns to God, not because God is of the male gender, but because the ] (Hebrew Bible) uses mainly male names. In Christianity, one person of God, the Son, is believed to have descended as a human male; however the gender of the other two persons of God is not so clear. Like in Judaism, the other two persons (the Father and the Holy Spirit) have traditionally been referred to using male pronouns and have primarily been associated with male imagery; but some Christians today, especially those inspired by feminism, do not consider this tradition to be binding. | |||

| The ] argues for the existence of God given the assumption of the objective existence of ]s.<ref>{{cite book |title=Atheism: A Philosophical Justification |publisher=Temple University Press |year=1992 |pages=213–214 |author=Martin, Michael |isbn=978-0877229438}}</ref> While prominent non-theistic philosophers such as the atheist ] agreed that the argument is valid, they disagreed with its premises. ] argued that there is no basis to believe in objective moral truths while biologist ] theorized that the feelings of morality are a by-product of natural selection in humans and would not exist independent of the mind.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Craig |first1=William Lane |title=The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology |last2=Moreland |first2=J. P. |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=2011 |isbn=978-1444350852 |page=393}}</ref> Philosopher ] argued that a subjective account for morality can be acceptable. Similar to the argument from morality is the ] which argues for the existence of God given the existence of a conscience that informs of right and wrong, even against prevailing moral codes. Philosopher ] instead argued that conscience is a social construct and thus could lead to contradicting morals.<ref>{{cite book |author=Parkinson |first=G. H. R. |title=An Encyclopedia of Philosophy |publisher=Taylor & Francis |year=1988 |isbn=978-0415003230 |pages=344–345}}</ref> | |||

| Most Neopagan traditions, such as Wicca, believe in both male and female Deities. A few (especially ]) see God as entirely feminine, and call her the ]. | |||

| ] is, in a broad sense, the rejection of ] in the existence of deities.<ref>Nielsen 2013</ref><ref>Edwards 2005"</ref> ] is the view that the ]s of certain claims—especially ] and religious claims such as ], the ] or the ] exist—are unknown and perhaps unknowable.<ref>], an English biologist, was the first to come up with the word ''agnostic'' in 1869 {{Cite book |last=Dixon |first=Thomas |title=Science and Religion: A Very Short Introduction |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2008 |location=Oxford |page=63 |isbn=978-0199295517}} However, earlier authors and published works have promoted an agnostic points of view. They include ], a 5th-century BCE Greek philosopher. {{cite web |url=http://www.iep.utm.edu/p/protagor.htm |title=The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Protagoras (c. 490 – c. 420 BCE) |access-date=6 October 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081014181706/http://www.iep.utm.edu/p/protagor.htm |archive-date=14 October 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Hepburn">{{cite encyclopedia |year=2005 |title=Agnosticism |encyclopedia=] |publisher=MacMillan Reference US (Gale) |last=Hepburn |first=Ronald W. |orig-date=1967 |editor=Borchert |editor-first=Donald M. |edition=2nd |volume=1 |page=92 |isbn=978-0028657806 |quote=In the most general use of the term, agnosticism is the view that we do not know whether there is a God or not.}} (p. 56 in 1967 edition).</ref><ref name="RoweRoutledge">{{cite encyclopedia |year=1998 |title=Agnosticism |encyclopedia=] |publisher=Taylor & Francis |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VQ-GhVWTH84C&q=agnosticism&pg=PA122 |last=Rowe |first=William L. |author-link=William L. Rowe |isbn=978-0415073103 |editor-first=Edward |editor-last=Craig |access-date=11 November 2020 |archive-date=23 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240523094732/https://books.google.com/books?id=VQ-GhVWTH84C&q=agnosticism&pg=PA122 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |year=2012 <!--|access-date=22 July 2013--> |entry=agnostic, agnosticism |dictionary=Oxford English Dictionary Online |publisher=Oxford University Press |edition=3rd}</ref> ] generally holds that God exists objectively and independently of human thought and is sometimes used to refer to any belief in God or gods. | |||

| == ]: How God communicates with mankind == | |||

| Some view the existence of God as an empirical question. ] states that "a universe with a god would be a completely different kind of universe from one without, and it would be a scientific difference".<ref name="Dawkins">{{cite news |last=Dawkins |first=Richard |author-link=Richard Dawkins |title=Why There Almost Certainly Is No God |url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/richard-dawkins/why-there-almost-certainl_b_32164.html |access-date=10 January 2007 |work=The Huffington Post |date=23 October 2006 |archive-date=6 October 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181006010610/https://www.huffingtonpost.com/richard-dawkins/why-there-almost-certainl_b_32164.html |url-status=live}}</ref> ] argued that the doctrine of a Creator of the Universe was difficult to prove or disprove and that the only conceivable scientific discovery that could disprove the existence of a Creator (not necessarily a God) would be the discovery that the universe is infinitely old.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Demon Haunted World |page=278 |last=Sagan |first=Carl |author-link=Carl Sagan |year=1996 |publisher=Ballantine Books |location=New York |isbn=978-0345409461}}</ref> Some theologians, such as ], argue that the existence of God is not a question that can be answered using the ].<ref name="mcgrath2005">{{cite book |author=McGrath |first=Alister E. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V9dr6167AJ8C |title=Dawkins' God: genes, memes, and the meaning of life |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |year=2005 |isbn=978-1405125390}}</ref><ref name="barackman2001">{{cite book |author=Barackman |first=Floyd H. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Jb5aRB7OxWsC |title=Practical Christian Theology: Examining the Great Doctrines of the Faith |publisher=Kregel Academic |year=2001 |isbn=978-0825423802}}</ref> | |||

| Judaism, Christianity and Islam hold that God can communicate His will to mankind; this process is called ]. The books of the ] (The Hebrew Bible) are held to be the product of ] by Jews; Both the ] and the ] are held to be the product of divine revelation by Christians; both the Tanakh are the New Testament are held to be deliberately corrupted and falsified works by Muslims; they affirm instead that the ] is the only work that represents divine revelation. How ] works, and what precisely one means when one says that a book is "divine" is a matter of some dispute. | |||

| ] ] argued that science and religion are not in conflict and proposed an approach dividing the world of philosophy into what he called "]" (NOMA).<ref>{{cite book |title=Leonardo's Mountain of Clams and the Diet of Worms |last=Gould |first=Stephen J. |page=274 |publisher=Jonathan Cape |year=1998 |isbn=978-0224050432}}</ref> In this view, questions of the ], such as those relating to the ] and nature of God, are ]-] and are the proper domain of ]. The methods of science should then be used to answer any empirical question about the natural world, and theology should be used to answer questions about ultimate meaning and moral value. In this view, the perceived lack of any empirical footprint from the magisterium of the supernatural onto natural events makes science the sole player in the natural world.<ref name="Dawkins-Delusion">{{cite book |title=The God Delusion |last=Dawkins |first=Richard |author-link=Richard Dawkins |year=2006 |publisher=Bantam Press |location=Great Britain |isbn=978-0618680009}}</ref> ] and co-author ] state in their 2010 book, '']'', that it is reasonable to ask who or what created the universe, but if the answer is God, then the question has merely been deflected to that of who created God. Both authors claim, however, that it is possible to answer these questions purely within the realm of science and without invoking divine beings.<ref>{{cite book |author=Hawking |first1=Stephen |url=https://archive.org/details/granddesign0000hawk |title=The Grand Design |last2=Mlodinow |first2=Leonard |publisher=Bantam Books |year=2010 |isbn=978-0553805376 |page= |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref>Krauss, L. ''A Universe from Nothing''. Free Press, New York. 2012. {{ISBN|978-1451624458}}.</ref> | |||

| == Meanings of Omnipotence == | |||

| ===Oneness=== | |||

| Discussions about God between people of different faiths, or indeed even between people of the same faith, are often unproductive, in no small amount due to the fact that people use the same words but assign them different meanings. This situations occurs when when monotheists, such as Christians, Muslims or Jews, state that God is omnipotent. In practice one finds that the term "omnipotent" has been used to connote a number of different positions. | |||

| {{Main|Deity|Monotheism|Henotheism}} | |||

| ] | |||

| A deity, or "god" (with ] ''g''), refers to a supernatural being.<ref name="OBrien">{{cite book |last1=O'Brien |first1=Jodi |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_nyHS4WyUKEC |title=Encyclopedia of Gender and Society |publisher=Sage |year=2009 |isbn=978-1412909167 |location=Los Angeles |page=191 |access-date=28 June 2017 |archive-date=13 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230113144056/https://books.google.com/books?id=_nyHS4WyUKEC |url-status=live}}</ref> ] is the belief that there is only one deity, referred to as "God" (with uppercase ''g''). Comparing or equating other entities to God is viewed as ] in monotheism, and is often strongly condemned. ] is one of the oldest monotheistic traditions in the world.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism/ |title=BBC – Religion: Judaism |website=www.bbc.co.uk |access-date=31 August 2022 |archive-date=5 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220805174338/https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism/ |url-status=live}}</ref> Islam's most fundamental concept is '']'', meaning 'oneness' or "uniqueness'.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Allah, Tawhid |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online |last=Gimaret |first=D.}}</ref> The first ] is an ] that forms the basis of the religion and which non-Muslims wishing to convert must recite, declaring that, "I testify that there is no deity except God."<ref>Mohammad, N. 1985. "The doctrine of jihad: An introduction". '']'' 3(2): 381–397.</ref> | |||

| (I) God can not only supersede the laws of physics and probability, but God can also rewrite logic itself (for example, God could create a square circle, or could make one equal two.) | |||

| In Christianity, the ] describes ] as one God in ], ] (]), and ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.whataboutjesus.com/grace/actions-god-series/what-trinity?page=0,0 |title=What Is the Trinity? |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140219020335/http://www.whataboutjesus.com/grace/actions-god-series/what-trinity?page=0%2C0 |archive-date=19 February 2014}}</ref> In past centuries, this fundamental mystery of the Christian faith was also summarized by the Latin formula ''Sancta Trinitas, Unus Deus'' (Holy Trinity, Unique God), reported in the '']''. | |||

| (II) God can intervene in the world by superseding the laws of physics and probability (i.e. God can create miracles), but it is impossible - in fact, it is meaningless - to suggest that God can rewrite the laws of logic. | |||

| ] is viewed differently by diverse strands of the religion, with most Hindus having faith in a ] (''Brahman'') who can be manifested in numerous chosen deities. Thus, the religion is sometimes characterized as ''Polymorphic Monotheism''.<ref>{{cite web |author=Lipner |first=Julius |date= |title=Hindu deities |url=https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/beginners-guide-asian-culture/hindu-art-culture/a/hindu-deities |access-date=6 September 2022 |archive-date=7 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220907001823/https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/beginners-guide-asian-culture/hindu-art-culture/a/hindu-deities |url-status=live}}</ref> ] is the belief and worship of a single god at a time while accepting the validity of worshiping other deities.<ref>Müller, Max. (1878) ''Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion: As Illustrated by the Religions of India''. London, England: Longmans, Green and Company.</ref> ] is the belief in a single deity worthy of worship while accepting the existence of other deities.<ref>{{citation |last=McConkie |first=Bruce R. |title=] |page=351 |year=1979 |edition=2nd |location=Salt Lake City, Utah |publisher=Bookcraft |author-link=Bruce R. McConkie}}.</ref> | |||

| (III) God originally could intervene in the world by superseding the laws of physics (i.e. create miracles); in fact God did do so by creating the Universe. However, God then self-obligated Himself not to do so anymore in order to give mankind free will. Miracles are rare, at best, and always hidden, to prevent man from being overwhelmed by absolute knowledge of God's existence, which could remove free will. | |||

| ===Transcendence=== | |||

| (IV) Omnipotence is sharply limited by neo-Aristotelian philosophers, who independently arose in Judaism, Christianity and Islam during the medieval era, and whose views still are considered normative among the intellectual eltire of these faith communities even today. In this view, God never interrupts the set laws of nature; once set, they are never repealed, for God never changes His mind. These philosophers envisioned a connection between the realm of the physical and the intellectual. All physical events are held to be the results of "intellects", some of which are human, some of which are "angels". These intellects can interact in such a way as to seemingly violate the laws of nature. Since God Himself crated the universe and the laws therein, this is how God works in the world. However, God does not actively intervene in a temporal sense. It has been noted that this view veers away from traditional theism, and moves towards deism. | |||

| {{See also|Pantheism|Panentheism}} | |||

| ] is the aspect of God's nature that is completely independent of the material universe and its physical laws. Many supposed characteristics of God are described in human terms. ] thought that God did not feel emotions such as anger or love, but appeared to do so through our imperfect understanding. The incongruity of judging "being" against something that might not exist, led many medieval philosophers approach to knowledge of God through negative attributes, called ]. For example, one should not say that God is wise, but can say that God is not ignorant (i.e. in some way God has some properties of knowledge). Christian theologian ] writes that one has to understand a "personal god" as an analogy. "To say that God is like a person is to affirm the divine ability and willingness to relate to others. This does not imply that God is human, or located at a specific point in the universe."<ref>{{Cite book |first=Alister |last=McGrath |author-link=Alister McGrath |title=Christian Theology: An Introduction |publisher=Blackwell |year=2006 |isbn=978-1405153607 |page=205}}</ref> | |||

| ] holds that God is the universe and the universe is God and denies that God transcends the Universe.<ref>{{cite web |date=17 May 2007 |title=Pantheism |url=https://stanford.library.sydney.edu.au/archives/spr2008/entries/pantheism/ |access-date=11 September 2022 |publisher=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |archive-date=11 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220911224648/https://stanford.library.sydney.edu.au/archives/spr2008/entries/pantheism/ |url-status=live}}</ref> For pantheist philosopher ], the whole of the natural universe is made of one substance, God, or its equivalent, Nature.<ref>{{cite book |last=Curley |first=Edwin M. |year=1985 |title=The Collected Works of Spinoza |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0691072227}}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2012/entries/spinoza/ |entry=Baruch Spinoza |encyclopedia=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |orig-date=2001 |date=21 August 2012 |last1=Nadler |first1=Steven |title=Baruch Spinoza |access-date=6 December 2012 |archive-date=13 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221113053208/https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2012/entries/spinoza/ |url-status=live}}</ref> Pantheism is sometimes objected to as not providing any meaningful explanation of God with the German philosopher ] stating, "Pantheism is only a euphemism for atheism."<ref>{{cite web |date=1 October 2012 |title=Pantheism |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pantheism/ |access-date=18 November 2022 |publisher=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |archive-date=15 September 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180915080407/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pantheism/ |url-status=live}}</ref> ] holds that God was a separate entity but then ].<ref name="Dawe">{{cite book |author=Dawe |first=Alan H. |title=The God Franchise: A Theory of Everything |year=2011 |isbn=978-0473201142 |page=48 |publisher=Alan H. Dawe}} | |||

| (V) In Unitarian-Universalism, much of Conservative and Reform Judaism, and some liberal wings of Protestant Christianity, God is said to act in the world through persuasion, and not by coercion. God makes Himself manifest in the world through inspiration and the creation of possibility, and not by miracles or violations of the laws of nature. The most popular works espousing this point are from Harold Kushner (in Judaism). This is the view that also was developed independently by ] and ], in the theological system known as ]. | |||

| </ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Bradley |first=Paul |title=This Strange Eventful History: A Philosophy of Meaning |year=2011 |isbn=978-0875868769 |page=156 |publisher=Algora |quote=Pandeism combines the concepts of Deism and Pantheism with a god who creates the universe and then becomes it.}}</ref> ] holds that God contains, but is not identical to, the Universe.<ref>Culp, John (2013). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151016023813/http://plato.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/encyclopedia/archinfo.cgi?entry=panentheism|date=16 October 2015}} ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', Spring.</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Rogers |first=Peter C. |title=Ultimate Truth, Book 1 |year=2009 |isbn=978-1438979687 |page=121 |publisher=AuthorHouse}}</ref> | |||

| ===Creator=== | |||

| See a list of ] from various religions. See also ]. | |||

| {{See also|Creator deity}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| God is often viewed as the cause of all that exists. For ]s, ] variously referred to divinity, the first being or an indivisible origin.<ref>Fairbanks, Arthur, Ed., "The First Philosophers of Greece". K. Paul, Trench, Trubner. London, England, 1898, p. 145.</ref> The philosophy of ] and ] refers to "]", which is the first principle of reality that is "beyond" being<ref>Dodds, E. R. "The Parmenides of Plato and the Origin of the Neoplatonic 'One'". ''The Classical Quarterly'', Jul–Oct 1928, vol. 22, p. 136.</ref> and is both the source of the Universe and the ] purpose of all things.<ref>{{cite book |last=Brenk |first=Frederick |date=January 2016 |title="Theism" and Related Categories in the Study of Ancient Religions |chapter=Pagan Monotheism and Pagan Cult |chapter-url=https://classicalstudies.org/annual-meeting/147/abstract/pagan-monotheism-and-pagan-cult |publisher=], University of Pennsylvania |location=Philadelphia |volume=75 |issue=4 |access-date=5 November 2022 |archive-date=6 May 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170506035740/https://classicalstudies.org/annual-meeting/147/abstract/pagan-monotheism-and-pagan-cult |url-status=live}} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220303063811/https://samreligions.org/2014/12/30/theism-and-related-categories-in-the-study-of-ancient-religions/ |date=3 March 2022 }}</ref> ] theorized a ] for all motion in the universe and viewed it as perfectly beautiful, immaterial, unchanging and indivisible. ] is the property of not depending on any cause other than itself for its existence. ] held that there must be a ] guaranteed to exist by its essence—it cannot "not" exist—and that humans identify this as God.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=From the necessary existent to God |first=Peter |last=Adamson |editor-first=Peter |editor-last=Adamson |encyclopedia=Interpreting Avicenna: Critical Essays |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OeVribsJbgUC |year=2013 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0521190732 |page=170}}</ref> ] refers to God creating the laws of the Universe which then can change themselves within the ]. In addition to the initial creation, ] refers to the idea that the Universe would not by default continue to exist from one instant to the next and so would need to rely on God as a ]. While ] refers to any intervention by God, it is usually used to refer to "special providence", where there is an extraordinary intervention by God, such as ]s.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Providence.aspx#1O101-Providence |title=Providence |encyclopedia=The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions |access-date=2014-07-17 |archive-date=17 April 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110417135306/http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Providence.aspx#1O101-Providence |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Creation, Providence, and Miracle |url=http://www.reasonablefaith.org/creation-providence-and-miracle |publisher=] |access-date=2014-05-20 |archive-date=13 May 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170513180211/http://www.reasonablefaith.org/creation-providence-and-miracle |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| /Talk | |||

| ===Benevolence=== | |||

| {{See also|Deism|Thirteen Attributes of Mercy}} | |||

| Deism holds that God exists but does not intervene in the world beyond what was necessary to create it,<ref name="lemos">{{cite book |last=Lemos |first=Ramon M. |title=A Neomedieval Essay in Philosophical Theology |publisher=Lexington Books |year=2001 |isbn=978-0739102503 |page=34}}</ref> such as answering prayers or producing miracles. Deists sometimes attribute this to God having no interest in or not being aware of humanity. Pandeists would hold that God does not intervene because God is the Universe.<ref name="Fuller">{{cite book |author=Fuller |first=Allan R. |title=Thought: The Only Reality |year=2010 |isbn=978-1608445905 |page=79 |publisher=Dog Ear}}</ref> | |||

| Of those theists who hold that God has an interest in humanity, most hold that God is ], omniscient, and benevolent. This belief raises questions about God's responsibility for evil and suffering in the world. ], which is related to ], is a form of theism which holds that God is either not wholly good or is fully malevolent as a consequence of the ]. | |||

| ===Omniscience and omnipotence=== | |||

| ] (all-powerful) is an attribute often ascribed to God. The ] is most often framed with the example "Could God create a stone so heavy that even he could not lift it?" as God could either be unable to create that stone or lift that stone and so could not be omnipotent. This is often countered with variations of the argument that omnipotence, like any other attribute ascribed to God, only applies as far as it is noble enough to befit God and thus God cannot lie, or do what is contradictory as that would entail opposing himself.<ref>{{Cite book |publisher=World Wisdom |isbn=978-1933316499 |title=Christianity/Islam : perspectives on esoteric ecumenism : a new translation with selected letters. |location=United Kingdom |year=2008 |last1=Perry |first1=M. |last2=Schuon |first2=F. |last3=Lafouge |first3=J. |page=135}}</ref> | |||

| Omniscience (all-knowing) is an attribute often ascribed to God. This implies that God knows how free agents will choose to act. If God does know this, either their ] might be illusory or foreknowledge does not imply predestination, and if God does not know it, God may not be omniscient.<ref name="Wierenga">Wierenga, Edward R. "Divine foreknowledge" in ]. ''The Cambridge Companion to Philosophy''. Cambridge University Press, 2001.</ref> ] limits God's omniscience by contending that, due to the nature of time, God's omniscience does not mean the deity can predict the future and ] holds that God does not have ], so is affected by his creation. | |||

| ===Other concepts=== | |||

| ] of theistic personalism (the view held by ], ], ], ], ], and most ]) argue that God is most generally the ground of all being, immanent in and transcendent over the whole world of reality, with immanence and transcendence being the contrapletes of personality.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.ditext.com/runes/t.html |title=www.ditext.com |access-date=7 February 2018 |archive-date=4 February 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180204214255/http://www.ditext.com/runes/t.html |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| God has also been conceived as being ] (immaterial), a ] being, the source of all ], and the "greatest conceivable existent".<ref name=Swinburne/> These attributes were all supported to varying degrees by the early Jewish, Christian and Muslim theologian philosophers, including ],<ref name=Edwards /> ],<ref name="Edwards">]. "God and the philosophers" in ]. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. {{ISBN|978-1615924462}}.</ref> and ],<ref name=Plantinga>]. "God, Arguments for the Existence of", ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', Routledge, 2000.</ref> respectively. | |||

| ==Non-theistic views== | |||

| ===Religious traditions=== | |||

| ] has ], holding that soul substances (]) are uncreated and that time is beginningless.<ref>Nayanar, Prof. A. Chakravarti (2005). ''Samayasāra of Ācārya Kundakunda''. Gāthā 10.310, New Delhi, India: Today & Tomorrows Printer and Publisher. p. 190.</ref> | |||

| Some interpretations and traditions of ] can be conceived as being ]. ] the specific monotheistic view of a ]. The Buddha criticizes the theory of creationism in the ].<ref>Thera, Narada (2006). ''"The Buddha and His Teachings"'', Jaico Publishing House. pp. 268–269.</ref><ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition", ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988: Mar) p. 2.</ref> Also, major Indian Buddhist philosophers, such as ], ], ], and ], consistently critiqued Creator God views put forth by Hindu thinkers.<ref>Cheng, Hsueh-Li. "Nāgārjuna's Approach to the Problem of the Existence of God" in Religious Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2 (June 1976), Cambridge University Press, pp. 207–216.</ref><ref>Hayes, Richard P., "Principled Atheism in the Buddhist Scholastic Tradition", ''Journal of Indian Philosophy'', 16:1 (1988: Mar.).</ref><ref>Harvey, Peter (2019). "Buddhism and Monotheism", Cambridge University Press. p. 1.</ref> However, as a non-theistic religion, Buddhism leaves the existence of a supreme deity ambiguous. There are significant numbers of Buddhists who believe in God, and there are equally large numbers who deny God's existence or are unsure.<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Khan |first=Razib |date=June 23, 2008 |title=Buddhists do Believe in God |url=https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/buddhists-do-believe-in-god |magazine=Discover |publisher=Kalmbach Publishing |access-date=26 April 2023 |archive-date=26 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230426041330/https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/buddhists-do-believe-in-god |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/religious-tradition/buddhist/ |title=Buddhists |website=Pew Research Center |publisher=The Pew Charitable Trusts |access-date=26 April 2023 |archive-date=26 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230426041330/https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/religious-tradition/buddhist/ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Chinese religions such as ] and ] are silent on the existence of creator gods. However, keeping with the tradition of ], adherents worship the spirits of people such as ] and ] in a similar manner to God.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/confucianism/ |title=Confucianism |website=National Geographic |publisher=National Geographic Society |access-date=26 April 2023 |archive-date=26 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230426232307/https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/confucianism/ |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/taoism/ |title=Taoism |website=National Geographic |publisher=National Geographic Society |access-date=26 April 2023 |archive-date=26 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230426232309/https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/taoism/ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Anthropology=== | |||

| {{See also|Evolutionary origin of religions|Evolutionary psychology of religion|Anthropomorphism}} | |||

| Some atheists have argued that a single, omniscient God who is imagined to have created the universe and is particularly attentive to the lives of humans has been imagined and embellished over generations.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Culotta |first1=E. |year=2009 |title=The origins of religion |journal=Science |volume=326 |issue=5954 |pages=784–787 |bibcode=2009Sci...326..784C |doi=10.1126/science.326_784 |pmid=19892955 |issn=0036-8075}}</ref> | |||

| ] argues that while there is a wide array of supernatural concepts found around the world, in general, supernatural beings tend to behave much like people. The construction of gods and spirits like persons is one of the best known traits of religion. He cites examples from ], which is, in his opinion, more like a modern ] than other religious systems.<ref name="boyer">{{cite book |title=Religion Explained |isbn=978-0465006960 |year=2001 |last=Boyer |first=Pascal |author-link=Pascal Boyer |url=https://archive.org/details/religionexplaine00boye |url-access=registration |quote=Admittedly, the Greek gods were extraordinarily anthropomorphic, and Greek mythology really is like the modern soap opera, much more so than other religious systems. |pages=–243 |publisher=Basic Books |location=New York}}</ref> | |||

| ] and Timothy Jurgensen demonstrate through formalization that Boyer's explanatory model matches physics' ] in positing not directly observable entities as intermediaries.<ref name="ducasteljurgensen">{{cite book |last1=du Castel |first1=Bertrand |title=Computer Theology |last2=Jurgensen |first2=Timothy M. |publisher=Midori Press |year=2008 |isbn=978-0980182118 |location=Austin, Texas |pages=221–222 -us |author-link=Bertrand du Castel}}</ref> | |||

| Anthropologist Stewart Guthrie contends that people project human features onto non-human aspects of the world because it makes those aspects more familiar. ] also suggested that god concepts are projections of one's father.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://commonsenseatheism.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/Barrett-Conceptualizing-a-Nonnatural-Entity.pdf |title=Conceptualizing a Nonnatural Entity: Anthropomorphism in God Concepts |year=1996 |last=Barrett |first=Justin |journal=Cognitive Psychology |volume=31 |issue=3 |pages=219–47 |doi=10.1006/cogp.1996.0017 |pmid=8975683 |s2cid=7646340 |access-date=20 November 2015 |archive-date=19 March 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150319064701/http://commonsenseatheism.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/Barrett-Conceptualizing-a-Nonnatural-Entity.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Likewise, ] was one of the earliest to suggest that gods represent an extension of human social life to include supernatural beings. In line with this reasoning, psychologist Matt Rossano contends that when humans began living in larger groups, they may have created gods as a means of enforcing morality. In small groups, morality can be enforced by social forces such as gossip or reputation. However, it is much harder to enforce morality using social forces in much larger groups. Rossano indicates that by including ever-watchful gods and spirits, humans discovered an effective strategy for restraining selfishness and building more cooperative groups.<ref name="supernature">{{cite journal |last=Rossano |first=Matt |year=2007 |title=Supernaturalizing Social Life: Religion and the Evolution of Human Cooperation |url=http://www2.selu.edu/Academics/Faculty/mrossano/recentpubs/Supernaturalizing.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=Human Nature |location=Hawthorne, New York |volume=18 |issue=3 |pages=272–294 |doi=10.1007/s12110-007-9002-4 |pmid=26181064 |s2cid=1585551 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120303101304/http://www2.selu.edu/Academics/Faculty/mrossano/recentpubs/Supernaturalizing.pdf |archive-date=3 March 2012 |access-date=25 June 2009}}</ref> | |||

| ===Neuroscience and psychology=== | |||

| {{See also|Jungian interpretation of religion}} | |||

| Johns Hopkins researchers studying the effects of the "spirit molecule" ], which is both an endogenous molecule in the human brain and the active molecule in the psychedelic ], found that a large majority of respondents said DMT brought them into contact with a "conscious, intelligent, benevolent, and sacred entity", and describe interactions that oozed joy, trust, love, and kindness. More than half of those who had previously self-identified as atheists described some type of belief in a higher power or God after the experience.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2020/fall/psychedelics-god-atheism/ |title=A spiritual experience |date=17 September 2020 |access-date=11 October 2022 |quote= |archive-date=19 October 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221019233542/https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2020/fall/psychedelics-god-atheism/ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| About a quarter of those afflicted by ]s experience what is described as a religious experience<ref>{{cite news |last=Sample |first=Ian |title=Tests of faith |url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2005/feb/24/1 |access-date=15 October 2022 |work=The Guardian |date=23 February 2005 |archive-date=23 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240523094847/https://www.theguardian.com/science/2005/feb/24/1 |url-status=live}}</ref> and may become preoccupied by thoughts of God even if they were not previously. Neuroscientist ] hypothesizes that seizures in the temporal lobe, which is closely connected to the emotional center of the brain, the ], may lead to those afflicted to view even banal objects with heightened meaning.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ramachandran |first1=Vilayanur |last2=Blakeslee |first2=Sandra |title=Phantoms in the brain |edition= |pages=174–187 |year=1998 |publisher=HarperCollins |location=New York |isbn=0688152473 |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| Psychologists studying feelings of awe found that participants feeling awe after watching scenes of natural wonders become more likely to believe in a supernatural being and to see events as the result of design, even when given randomly generated numbers.<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Kluger |first=Jeffrey |title=Why There Are No Atheists at the Grand Canyon |url=https://science.time.com/2013/11/27/why-there-are-no-atheists-at-the-grand-canyon/ |access-date=12 October 2022 |magazine=Time |date=27 November 2013 |archive-date=19 October 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221019233537/https://science.time.com/2013/11/27/why-there-are-no-atheists-at-the-grand-canyon/ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Relationship with humanity== | |||

| {{anchor|Relationship with creation}} | |||

| ]'' by ]]] | |||

| ===Worship=== | |||

| {{See also|Worship|Prayer|Supplication}} | |||

| Theistic religious traditions often require worship of God and sometimes hold that the ] is to worship God.<ref name="patheos1">{{cite web |url=http://www.patheos.com/Library/Islam/Beliefs/Human-Nature-and-the-Purpose-of-Existence.html |title=Human Nature and the Purpose of Existence |publisher=Patheos.com |access-date=29 January 2011 |archive-date=29 August 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110829020001/http://www.patheos.com/Library/Islam/Beliefs/Human-Nature-and-the-Purpose-of-Existence.html |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{qref|51|56|b=y}}.</ref> To address the issue of an all-powerful being demanding to be worshipped, it is held that God does not need or benefit from worship but that worship is for the benefit of the worshipper.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/practices/salat.shtml |title=Salat: daily prayers |publisher=BBC |access-date=12 April 2022 |archive-date=22 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220322040017/https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/practices/salat.shtml |url-status=live}}</ref> ] expressed the view that God does not need his supplication and that, "Prayer is not an asking. It is a longing of the soul. It is a daily admission of one's weakness."<ref>{{Cite book |title=The Philosophy of Gandhi: A Study of his Basic Ideas |first=Glyn |last=Richards |publisher=Routledge |year=2005 |isbn=1135799342}}</ref> Invoking God in prayer plays a significant role among many believers. Depending on the tradition, God can be viewed as a personal God who is only to be invoked directly while other traditions allow praying to intermediaries, such as ]s, to ] on their behalf. Prayer often also includes ] such as ]. God is often believed to be forgiving. For example, a ] states God would replace a sinless people with one who sinned but still asked repentance.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://en.islamtoday.net/artshow-426-3787.htm |title=Allah would replace you with a people who sin |publisher=islamtoday.net |access-date=13 October 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131014174102/http://en.islamtoday.net/artshow-426-3787.htm |archive-date=14 October 2013}}</ref> ] for the sake of God is another act of devotion that includes ] and ]. ] of God in daily life include mentioning interjections ] when feeling gratitude or ], such as repeating ]s while performing other activities. | |||

| ===Salvation=== | |||

| {{Main|Salvation}} | |||

| ] religious traditions may believe in the existence of deities but deny any spiritual significance to them. The term has been used to describe certain strands of Buddhism,<ref>Rigopoulos, Antonio. ''The Life and Teachings of Sai Baba of Shirdi'' (1993), p. 372; Houlden, J. L. (Ed.), ''Jesus: The Complete Guide'' (2005), p. 390.</ref> Jainism and ].<ref>de Gruyter, Walter (1988), ''Writings on Religion'', p. 145.</ref> | |||

| Among religions that do attach spirituality to the relationship with God disagree as how to best worship God and what is ] for mankind. There are different approaches to reconciling the contradictory claims of monotheistic religions. One view is taken by exclusivists, who believe they are the ] or have exclusive access to absolute truth, generally through ] or encounter with the Divine, which adherents of other religions do not. Another view is ]. A pluralist typically believes that his religion is the right one, but does not deny the partial truth of other religions. The view that all theists actually worship the same god, whether they know it or not, is especially emphasized in the Baháʼí Faith, Hinduism,<ref>See Swami Bhaskarananda, ''Essentials of Hinduism'' (Viveka Press, 2002), {{ISBN|1884852041}}.</ref> and Sikhism.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.srigranth.org/servlet/gurbani.gurbani?Action=Page&Param=1350&english=t&id=57718 |title=Sri Guru Granth Sahib |publisher=Sri Granth |access-date=30 June 2011 |archive-date=28 July 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110728045943/http://www.srigranth.org/servlet/gurbani.gurbani?Action=Page&Param=1350&english=t&id=57718 |url-status=live}}</ref> The ] preaches that ]s include great prophets and teachers of many of the major religious traditions such as Krishna, Buddha, Jesus, Zoroaster, Muhammad, Bahá'ú'lláh and also preaches the unity of all religions and focuses on these multiple epiphanies as necessary for meeting the needs of humanity at different points in history and for different cultures, and as part of a scheme of ] and education of humanity. An example of a pluralist view in Christianity is ], i.e., the belief that one's religion is the fulfillment of previous religions. A third approach is ], where everybody is seen as equally right; an example being ]: the doctrine that ] is eventually available for everyone. A fourth approach is ], mixing different elements from different religions. An example of syncretism is the ] movement. | |||

| ==Epistemology== | |||

| ===Faith=== | |||

| {{Main|Faith}} | |||

| ] is the position that in certain topics, notably theology such as in ], faith is superior than reason in arriving at truths. Some theists argue that there is value to the risk in having faith and that if the arguments for God's existence were as rational as the laws of physics then there would be no risk. Such theists often argue that the heart is attracted to beauty, truth and goodness and so would be best for dictating about God, as illustrated through ] who said, "The heart has its reasons that reason does not know."<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ncregister.com/blog/the-heart-has-its-reasons-that-reason-does-not-know |title=The Heart Has Its Reasons That Reason Does Not Know |publisher=National Catholic Register |last=D’Antuono |first=Matt |date=1 August 2022 |access-date=1 June 2023 |archive-date=8 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230608024610/https://www.ncregister.com/blog/the-heart-has-its-reasons-that-reason-does-not-know |url-status=live}}</ref> A hadith attributes a quote to God as "I am what my slave thinks of me."<ref>{{cite book |title=A Treasury of Hadith: A Commentary on Nawawi's Selection of Prophetic Traditions |publisher=Kube Publishing Limited |year=2014 |page=199 |author=Ibn Daqiq al-'Id |isbn=978-1847740694}}</ref> Inherent intuition about God is referred to in Islam as '']'', or "innate nature".<ref>{{Citation |last=Hoover |first=Jon |title=Fiṭra |date=2016-03-02 |url=https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/*-COM_27155 |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE |access-date=2023-11-13 |publisher=Brill |doi=10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_com_27155 |archive-date=28 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221228111034/https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/*-COM_27155 |url-status=live}}.</ref> In Confucian tradition, Confucius and ] promoted that the only justification for right conduct, called the Way, is what is dictated by Heaven, a more or less anthropomorphic higher power, and is implanted in humans and thus there is only one universal foundation for the Way.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://aeon.co/essays/the-influential-confucian-philosopher-you-ve-never-heard-of |title=The Second Sage |publisher=Aeon |access-date=24 March 2023 |archive-date=24 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230324222651/https://aeon.co/essays/the-influential-confucian-philosopher-you-ve-never-heard-of |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Revelation=== | |||

| {{Main|Revelation}} | |||

| {{See also|Prophet}} | |||

| Revelation refers to some form of message communicated by God. This is usually proposed to occur through the use of ]s or ]s. ] argued for the need for revelation because even though humans are intellectually capable of realizing God, human desire can divert the intellect and because certain knowledge cannot be known except when specially given to prophets, such as the specifications of acts of worship.<ref>Çakmak, Cenap. ''Islam: A Worldwide Encyclopedia'' ABC-CLIO 2017, {{ISBN|978-1610692175}}, p. 1014.</ref> It is argued that there is also that which overlaps between what is revealed and what can be derived. According to Islam, one of the earliest revelations to ever be revealed was "If you feel no shame, then do as you wish."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Siddiqui |first=A. R. |title=Qur'anic Keywords: A Reference Guide. |publisher=Kube Publishing Limited |year=2015 |pages=53 |isbn=9780860376767}}</ref> The term ] is used to refer to knowledge revealed about God outside of ] or ] revelation such as scriptures. Notably, this includes studying nature, sometimes seen as the ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://silas.psfc.mit.edu/Faraday/ |title=Michael Faraday: Scientist and Nonconformist |last=Hutchinson |first=Ian |date=14 January 1996 |quote=] believed that in his scientific researches he was reading the book of nature, which pointed to its creator, and he delighted in it: 'for the book of nature, which we have to read is written by the finger of God.' |access-date=30 November 2022 |archive-date=1 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221201001723/http://silas.psfc.mit.edu/Faraday/ |url-status=live}}</ref> An idiom in Arabic states, "The Qur'an is a Universe that speaks. The Universe is a silent Qur'an."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hofmann |first=Murad |title=Islam and Qur'an |publisher=Amana publications |year=2007 |pages=121 |isbn=978-1590080474}}</ref> | |||

| ===Reason=== | |||

| On matters of theology, some such as ], take an ] position, where a belief is only justified if it has a reason behind it, as opposed to holding it as a ].<ref>{{Cite journal |first=Michael |last=Beaty |year=1991 |title=God Among the Philosophers |url=http://www.religion-online.org/showarticle.asp?title=53 |journal=The Christian Century |access-date=20 February 2007 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070109162529/http://www.religion-online.org/showarticle.asp?title=53 |archive-date=9 January 2007}}</ref> ] holds that one should not opinionate beyond revelation to understand God's nature and frown upon rationalizations such as ].<ref name=Halverson-36>{{Harvtxt|Halverson|2010|page=}}.</ref> Notably, for ] such as the "Hand of God" and ], they neither nullify such texts nor accept a literal hand but leave any ambiguity to God, called '']'', without ].<ref name="Hoover 2020">{{cite book |author-last=Hoover |author-first=John |year=2020 |chapter=Early Mamlūk Ashʿarism against Ibn Taymiyya on the Nonliteral Reinterpretation (''taʾwīl'') of God’s Attributes |chapter-url=https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/output/3741348 |editor1-last=Shihadeh |editor1-first=Ayman |editor2-last=Thiele |editor2-first=Jan |title=Philosophical Theology in Islam: Later Ashʿarism East and West |location=Leiden and Boston |publisher=Brill |series=Islamicate Intellectual History |volume=5 |pages=195–230 |doi=10.1163/9789004426610_009 |isbn=978-9004426610 |s2cid=219026357 |issn=2212-8662 |access-date=13 November 2022 |archive-date=6 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230406075456/https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/output/3741348 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=Halverson-3637>{{harvtxt|Halverson|2010|pages=}}.</ref> ] provides arguments for theological topics based on reason.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |last1=Chignell |first1=Andrew |title=Natural Theology and Natural Religion |date=2020 |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/natural-theology/ |encyclopedia=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |editor-last=Zalta |editor-first=Edward N. |access-date=2020-10-09 |edition=Fall 2020 |publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University |last2=Pereboom |first2=Derk |archive-date=18 February 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220218132535/https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/natural-theology/ |url-status=live}}.</ref> | |||

| ==Specific characteristics== | |||

| {{See also|Attributes of God (disambiguation)}} | |||

| ===Titles=== | |||

| {{Main|Names of God}} | |||

| {{See also|Names of God in Islam}} | |||

| ], in Chinese ]]] | |||

| In the ] tradition, "the Bible has been the principal source of the conceptions of God". That the Bible "includes many different images, concepts, and ways of thinking about" God has resulted in perpetual "disagreements about how God is to be conceived and understood".<ref>Fiorenza, Francis Schüssler and Kaufman, Gordon D., "God", Ch 6, in Taylor, Mark C., ed., ''Critical Terms for Religious Studies'' (University of Chicago, 1998/2008), pp. 136–140.</ref> Throughout the Hebrew and Christian Bibles there are titles for God, who revealed his personal name as ] (often vocalized as ''Yahweh'' or ''Jehovah'').<ref name="Parke-Taylor2006"/> One of them is '']''. Another one is '']'', translated 'God Almighty'.<ref>Gen. 17:1; 28:3; 35:11; Ex. 6:31; Ps. 91:1, 2.</ref> A third notable title is '']'', which means 'The High God'.<ref>Gen. 14:19; Ps. 9:2; Dan. 7:18, 22, 25.</ref> Also noted in the ] and ] Bibles is the name "]".<ref>Exodus 3:13–15.</ref><ref name="Parke-Taylor2006"/> | |||

| God is described and referred in the ] and hadith by certain ], the most common being '']'', meaning 'Most Compassionate', and ''Al-Rahim'', meaning 'Most Merciful'.<ref name="Ben">{{Cite book |last=Bentley |first=David |title=The 99 Beautiful Names for God for All the People of the Book |publisher=William Carey Library |year=1999 |isbn=978-0878082995}}</ref> Many of these names are also used in the scriptures of the ]. | |||

| ], a tradition in Hinduism, has a ]. | |||

| ===Gender=== | |||

| {{Main|Gender of God}} | |||

| The gender of God may be viewed as either a literal or an allegorical aspect of a deity who, in classical Western philosophy, transcends bodily form.<ref>{{cite book |last=Aquinas |first=Thomas |title=Summa Theologica |section=First part: Question 3: The simplicity of God: Article 1: Whether God is a body? |url=http://www.newadvent.org/summa/1003.htm |publisher=New Advent |access-date=22 June 2012 |archive-date=9 November 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111109160402/http://newadvent.org/summa/1003.htm |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/confessionsaugu00shedgoog |title=The Confessions of Augustine |publisher=Warren F. Draper |year=1885 |editor=Shedd |editor-first=William G. T. |section=Chapter 7}}</ref> ] religions commonly attribute to each of ''the gods'' a gender, allowing each to interact with any of the others, and perhaps with humans, sexually. In most monotheistic religions, God has no counterpart with which to relate sexually. Thus, in classical Western philosophy the gender of this one-and-only deity is most likely to be an ] statement of how humans and God address, and relate to, each other. Namely, God is seen as begetter of the world and revelation which corresponds to the active (as opposed to the receptive) role in sexual intercourse.<ref name=":1">{{cite book |last1=Lang |first1=David |title=Why Matter Matters: Philosophical and Scriptural Reflections on the Sacraments |year=2002 |publisher=Our Sunday Visitor |chapter=Why Male Priests? |isbn=978-1931709347 |first2=Peter |last2=Kreeft}}</ref> | |||

| Biblical sources usually refer to God using male or paternal words and symbolism, except {{Bibleverse|Genesis||1:26–27|KJV}},<ref>Pagels, Elaine H. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101123111512/http://holyspirit-shekinah.org/_/what_became_of_god_the_mother-1.htm|date=23 November 2010}} Signs, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Winter 1976), pp. 293–303.</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Coogan |first=Michael |url=https://archive.org/details/godsexwhatbi00coog/page/175 |title=God and Sex. What the Bible Really Says |publisher=Twelve. Hachette Book Group |year=2010 |isbn=978-0446545259 |edition=1st |location=New York; Boston, Massachusetts |page= |chapter=6. Fire in Divine Loins: God's Wives in Myth and Metaphor |quote=humans are modeled on ''elohim'', specifically in their sexual differences. |access-date=5 May 2011 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2_gPKQEACAAJ&q=god+and+sex}}</ref> {{Bibleverse|Psalm||123:2–3|KJV}}, and {{Bibleverse|Luke||15:8–10|KJV}} (female); {{Bibleverse|Hosea||11:3–4|KJV}}, {{Bibleverse|Deuteronomy||32:18|KJV}}, {{Bibleverse|Isaiah||66:13|KJV}}, {{Bibleverse|Isaiah||49:15|KJV}}, {{Bibleverse|Isaiah||42:14|KJV}}, {{Bibleverse|Psalm||131:2|KJV}} (a mother); {{Bibleverse|Deuteronomy||32:11–12|KJV}} (a mother eagle); and {{Bibleverse|Matthew||23:37|KJV}} and {{Bibleverse|Luke||13:34|KJV}} (a mother hen). | |||

| In ], ] is "Ajuni" (Without Incarnations), which means that God is not bound to any physical forms. This concludes that the All-pervading Lord is Gender-less.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.sikhwomen.com/equality/GodsGender.htm |title=God's Gender |website=www.sikhwomen.com |access-date=5 December 2023 |archive-date=5 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231205122743/http://www.sikhwomen.com/equality/GodsGender.htm |url-status=live}}</ref> However, the ] constantly refers to God as 'He' and 'Father' (with some exceptions), typically because the Guru Granth Sahib was written in north Indian ]s (mixture of ] and ], Sanskrit with influences of Persian) which have no neutral gender. From further insights into the Sikh philosophy, it can be deduced that God is, sometimes, referred to as the Husband to the Soul-brides, in order to make a patriarchal society understand what the relationship with God is like. Also, God is considered to be the Father, Mother, and Companion.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.gurbani.org/articles/webart270.htm |title=IS GOD MALE OR FEMALE? |website=www.gurbani.org |access-date=5 December 2023 |archive-date=5 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231205122754/https://www.gurbani.org/articles/webart270.htm |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Depiction=== | |||

| {{See also|Incorporeality|God the Father in Western art}} | |||

| ] (left) with the ring of kingship. (Relief at ], 3rd century CE)]] | |||

| In Zoroastrianism, during the early ], ] was visually represented for worship. This practice ended during the beginning of the ]. Zoroastrian ], which can be traced to the end of the Parthian period and the beginning of the Sassanid, eventually put an end to the use of all images of Ahura Mazda in worship. However, Ahura Mazda continued to be symbolized by a dignified male figure, standing or on horseback, which is found in Sassanian investiture.{{Sfn|Boyce|1983|p=686}} | |||