| Revision as of 00:06, 20 January 2010 view source76.123.99.101 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:32, 24 December 2024 view source D9xv (talk | contribs)77 editsm Included comma | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| '''Creation according to Genesis''' refers to the creation narrative found in the first book of the ] and Christian Bible, the ].<ref>{{cite book | last = Browning | first = W. R. F. | authorlink = W. R. F. Browning | coauthors = | title = A Dictionary of the Bible (myth) | publisher = Oxford University Press | year = 1997 | location = | pages = | url = http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t94.e1296 | doi = | id = | isbn = 978-0192116918}}</ref> While agnostics and atheists believe the narrative to be a myth, millions of Christians and Jews believe the Creation narrative to be based in fact. Other Christians and Jews believe this narrative to be a type of ancient legend. While such Christians and Jews believe that a supreme being created the world, they believe that evolution was directed by this being. Whichever view is likely cannot be directly verified by science. | |||

| {{Short description|Creation myth of Judaism and Christianity}} | |||

| {{redirect2|Genesis 1|Creation of Man|other uses|Genesis 1 (disambiguation)|the ''Scarlet Pimpernel'' song|The Creation of Man|the Michelangelo fresco|The Creation of Man (Michaelangelo) {{!}}''The Creation of Man'' (Michaelangelo)}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

| ] (1836–1902)]] | |||

| {{Bible-related}} | |||

| {{Creationism sidebar}} | |||

| <!--Please do not remove the phrase and link to "creation myth" from the first paragraph without discussing your proposal on the talk page first. There has been a consensus since November 2011 to include it in the lead. You can read the archived talk discussion at: Talk:Genesis_creation_narrative/Archive_13#RfC:_Genesis_creation_narrative:_link_to_creation_myth.2C_yes_or_no.3F--> | |||

| The '''Genesis creation narrative''' is the ]{{efn|name="myth"}} of both ] and ],{{sfn|Leeming|Leeming|2004|p=113}} told in the ] ch. 1–2. While the Jewish and Christian tradition is that the account is one comprehensive story,{{sfn|Baden|2012|p=13}}{{sfn|Friedman|Dolansky Overton|2007|p=734}} modern scholars of ] identify the account as a composite work{{sfn|Speiser|1964|p=xxi}} made up of two stories drawn from different sources.{{efn|name="two_stories"}} | |||

| According to modern biblical textual criticism, Genesis Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 seem to describe two creation narratives. Genesis Chapter 1 is from the Priestly source ), and Genesis Chapter 2 from another Jahwist ). (New Oxford Annotated Bible, pp. 11-13, 2001). An ancient compiler seems to have woven the two narratives together into the complete creation narrative in the Hebrew and Christian bibles. | |||

| The first account, in Genesis 1:1–2:3, is from what scholars call the ] (P), largely dated to the 6th century BCE.{{sfn|Coogan|Chapman|2018|p=48}} In this story, ] (the Hebrew generic word for "]") creates the heavens and the Earth in six days, then rests on, blesses, and sanctifies the seventh (i.e. the ]). The second account, which takes up the rest of Genesis 2, is largely from the ] source (J),{{Sfn|Collins|2018|p=71}}{{sfn|Bandstra|2008|p=37}} commonly dated to the 10th or 9th centuries BCE.{{Sfn|Coogan|Chapman|2018|p=48}} In this story, God (now referred to by the personal name ]) creates ], the first man, from dust and places him in the ]. There he is given dominion over the animals. ], the first woman, is created from Adam's rib as his companion. | |||

| Chapter 1 describes ]'s creation of the world by divine speech in six days, culminating in the sanctification of the seventh day as the ], the divinely-ordained day of rest. Man and woman are created to be God's regents over this new creation. The second chapter recounts God's planting of a garden in which he places the first man, and from whose rib (or side) God fashions the first woman. The chapter ends with an injunction on the sanctity of marriage. | |||

| The first major comprehensive draft of the ]{{efn|The series of five books which begins with Genesis and ends with ]}} is thought to have been composed in the late 7th or the 6th century BCE (the ] source) and was later expanded by other authors (the ]) into a work much alike to Genesis as known today.{{sfn|Davies|2001|p=37}} The authors of the text were influenced by ] and ], and borrowed several themes from them, adapting and integrating them with their unique ].{{sfn|Sarna|1997|p=50}}{{sfn|Klamm|Winitzer|2023}}{{efn|name="Mesopotamian_mythology"}} The combined narrative is a critique of the ] of creation: Genesis affirms ] and denies ].{{sfn|Wenham|2003b|p=37}} | |||

| The narrative reflects the common substratum of Middle Eastern mythology at the time of its compilation in the 1st millennium BC, and assumes a flat Earth floating in the surrounding waters of Chaos. For its authors it represented a monotheistic polemic directed against Babylon, the oppressor of the Jews;<ref name="MK1">], "Because It Had Not Rained", (Westminster Theological Journal, 20 (2), May 1958), pp. 146-57; Meredith G. Kline, "Space and Time in the Genesis Cosmogony", Perspectives on Science & Christian Faith (48), 1996), pp. 2-15; ], {{cite book|author=Henri Blocher|title=In the Beginning: The Opening Chapters of Genesis|publisher=InterVarsity Press, 1984}}; and with antecedents in St. ] {{cite journal | |||

| | title=The Contemporary Relevance of Augustine's View of Creation | |||

| | author=Davis A. Young | |||

| | url=http://www.asa3.org/ASA/topics/Bible-Science/PSCF3-88Young.html | |||

| | journal=Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith | |||

| | volume=40 | |||

| | issue=1 | |||

| | pages=42–45 | |||

| | year=1988 | |||

| | Format={{Dead link|date=March 2009}} – <sup></sup> | |||

| }}</ref> later scholars found in it a homily of the essential unity of mankind and the sanctity of life.<ref name="ReferenceB">Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin 37a.</ref> | |||

| == |

==Composition== | ||

| ] |

] tablet with the ] in the ]]] | ||

| ] fresco, 1480s).]] | |||

| The modern division of the Bible into chapters dates from c. AD 1200, and the division into verses somewhat later; the distinction between Genesis 1 and 2 is therefore a relatively recent development.<ref>Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: Volume 1, The Pentateuch", SPCK, (2003), p.5.</ref> | |||

| ===Genre=== | |||

| === First narrative: Creation week === | |||

| Scholarly writings frequently refer to Genesis as myth, a ] of ] consisting primarily of ]s that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is in contrast to more vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the veracity of a myth is not a defining criterion.{{sfn|Deretic|2020}}{{efn|name="Hamilton_1990"|{{harvtxt|Hamilton|1990|pp=57–58}} notes that while ] famously suggested that the author of Genesis 1–11 "demythologised" his narrative, meaning that he removed from his sources (the Babylonian myths) those elements which did not fit with his own faith, Genesis may still be referred to as mythical.}} | |||

| {{bibleref2|Genesis|1:1-2:4|NIV}} | |||

| ===Authorship and dating=== | |||

| The creation week narrative consists of eight divine commands executed over six days, followed by a seventh day of rest. | |||

| {{See also|Documentary hypothesis|Textual variants in the Hebrew Bible#Genesis 1|Textual variants in the Hebrew Bible#Genesis 2}} | |||

| Although Orthodox Jews and "fundamentalist Christians" attribute the authorship of ] to ] "as a matter of faith," the Mosaic authorship has been questioned since the 11th century, and has been rejected in scholarship since the 17th century.{{sfn|Baden|2012|p=13}}{{sfn|Friedman|Dolansky Overton|2007|p=734}} Scholars of ] conclude that it, together with the following four books (making up what Jews call the ] and biblical scholars call the Pentateuch), is "a composite work, the product of many hands and periods."{{sfn|Speiser|1964|p=xxi}}{{efn|name="two_stories"}} | |||

| * First day: God creates light ("Let there be light!"){{bibleref2c|Gen|1:3}}—the first divine command. The light is divided from the darkness, and "day" and "night" are named. | |||

| * Second day: God creates a ] ("Let a firmament be...!"){{bibleref2c|Gen|1:6-7}}—the second command—to divide the waters above from the waters below. The firmament is named "skies". | |||

| * Third day: God commands the waters below to be gathered together in one place, and dry land to appear (the third command).{{bibleref2c|Gen|1:9-10}} "Earth" and "sea" are named. God commands the earth to bring forth grass, plants, and fruit-bearing trees (the fourth command). | |||

| * Fourth day: God creates lights in the firmament (the fifth command){{bibleref2c|Gen|1:14-15}} to separate light from darkness and to mark days, seasons and years. Two great lights are made (most likely the Sun and Moon, but not named), and the stars. | |||

| * Fifth day: God commands the sea to "teem with living creatures", and birds to fly across the heavens (sixth command){{bibleref2c|Gen|1:20-21}} He creates birds and sea creatures, and commands them to be fruitful and multiply. | |||

| * Sixth day: God commands the land to bring forth living creatures (seventh command);{{bibleref2c|Gen|1:24-25}} He makes wild beasts, livestock and reptiles. He then creates Man and Woman in His "]" and "likeness" (eighth command).{{bibleref2c|Gen|1:26-28}} They are told to "be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it." Humans and animals are given plants to eat. The totality of creation is described by God as "very good." | |||

| * Seventh day: God, having completed the heavens and the earth, rests from His work, and blesses and sanctifies the seventh day. | |||

| The creation narrative consists of two separate accounts, drawn from different sources.{{efn|name="two_stories"}} The first account, in Genesis 1:1–2:3, is from what scholars call the ] (P), largely dated to the 6th century BCE.{{sfn|Coogan|Chapman|2018|p=48}} The second account, which is older and takes up the rest of Genesis 2, is largely from the ] source (J),{{sfn|Collins|2018|p=71}} commonly dated to the 10th or 9th centuries BCE.{{Sfn|Coogan|Chapman|2018|p=48}} | |||

| === Literary Bridge === | |||

| {{bibleref2|Genesis|2:4}} | |||

| The two stories were combined, but there is currently no scholarly consensus on when the narrative reached its final form.{{sfn|Whybray|2001|p=41}} A common hypothesis among biblical scholars today is that the first major comprehensive narrative of the Pentateuch was composed in the 7th or 6th centuries BCE.{{sfn|Davies|2001|p=37}} A sizeable minority of scholars believe that the first eleven chapters of Genesis, also known as the ], can be dated to the 3rd century BCE, based on discontinuities between the contents of the work and other parts of the ].{{sfn|Gmirkin|2006|pp=240–241}} | |||

| :''These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created.'' | |||

| The "Persian imperial authorisation," which has gained considerable interest, although still controversial,{{source?|date=September 2024}} proposes that the ], after their ] in 538 BCE, agreed to grant Jerusalem a large measure of local autonomy within the empire, but required the local authorities to produce a single ] accepted by the entire community. According to this theory, there were two powerful groups in the community, the priestly families who controlled the Temple, and the landowning families who made up the "elders," which were in conflict over many issues. Each had its own "history of origins," but the Persian promise of greatly increased local autonomy for all provided a powerful incentive to cooperate in producing a single text.{{sfn|Ska|2006|pp=169, 217–18}} | |||

| The phrase "These are the ''generations'' (Hebrew תוֹלְדוֹת; ''tôledôt'') of the heavens and the earth when they were created" lies between the creation week narrative and the ] narrative which follows, and the first of ten phrases ("''tôledôt''") used to provide structure to the book of ].<ref>Frank Moore Cross, "The Priestly Work," in ''Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic'', 1973. The other nine are for 2 Adam ,<sup>Genesis 5:1</sup> 3 Noah,{{bibleref2c|Genesis|6:9|HE}} 4 Noah's sons , 5 Shem,{{bibleref2c|Gen.|11:10|HE}} 6 Terah,{{bibleref2c|Gen.|11:27|HE}} 7 Yishmael,{{bibleref2c||Gen.|25:12|HE}} 8 Isaac,{{bibleref2c||Gen.|25:19|HE}} 9 Esau,{{bibleref2c||Gen.|36:1|HE}} and 10 Jacob.{{bibleref2c||Gen.|37:2|HE}}</ref> Since the phrase always precedes the "generation" to which it belongs, the "generations of the heavens and the earth" should logically be taken to refer to Genesis 2; a position taken by most commentators.<ref name="GWenham">{{cite book|title=Genesis 1-15 (Word Biblical Commentary)|author=]|publisher=Word Books, Texas, 1987}}</ref> Nevertheless, other commentators from ] to the present day have argued that in this case it should apply to what precedes.<ref group="note">The argument is based on several grounds, notably the fact that Genesis 1 uses the phrase "heavens and earth" to introduce and close the Creation, while the narrative in Chapter 2 is introduced by the phrase "earth and heavens." Advocates of the other view argue that 2:4 is designed as a chiasm (Wenham, 49)</ref> | |||

| ===Two stories=== | |||

| === Second narrative: Eden narrative === | |||

| The creation narrative is made up of two stories,{{sfn|Ehrman|2021}}{{efn|name="two_stories"}} roughly equivalent to the two first chapters of the Book of Genesis{{sfn|Alter|1981|p=141}} (there are no chapter divisions in the original Hebrew text; see "]"). | |||

| {{bibleref2|Genesis|2:4-25|NIV}} | |||

| In the first story, the Creator deity is referred to as "]" (the Hebrew generic word for "]"), whereas in the second story, he is referred to with a composite divine name; "] God". Traditional or evangelical scholars such as Collins explain this as a single author's variation in style in order to, for example, emphasize the unity and transcendence of "God" in the first narrative, who created the heavens and the earth by himself.{{sfn|Collins|2006|p=229}} Critical scholars such as ], on the contrary, take this as evidence of multiple authorship. Friedman states that the Jahwist source originally only used the "L{{sc|ord}}" (Yahweh) title, but a later editor added "God" to form the composite name: "It therefore appears to be an effort by the Redactor (R) to soften the transition from the P creation, which uses only 'God' (thirty-five times), to the coming J stories, which use only the name YHWH."{{sfn|Collins|2006|p=227}} | |||

| ], depicting ] in the ].]] | |||

| The first account ({{Bibleverse|Genesis|1:1–2:3}}) employs a repetitious structure of divine fiat and fulfillment, then the statement "And there was evening and there was morning, the day," for each of the six days of creation. In each of the first three days there is an act of division: day one divides the ], day two the "waters above" from the "waters below", and day three the sea from the land. In each of the next three days these divisions are populated: day four populates the darkness and light with Sun, Moon and stars; day five populates seas and skies with fish and fowl; and finally land-based creatures and mankind populate the land.{{sfn|van Ruiten|2000|pp=9–10}} | |||

| The ] narrative addresses the creation of the first man and woman: | |||

| In the second story Yahweh creates ], the first man, from dust and places him in the ]. There he is given dominion over the animals. ], the first woman, is created from Adam's rib as his companion. | |||

| * {{bibleref2|Genesis|2:4||Genesis 2:4b}}—the second half of the bridge formed by the "generations" formula, and the beginning of the Eden narrative—places the events of the narrative "in the day when YHWH Elohim made the earth and the heavens..."<ref group="note">The lack of punctuation in the Hebrew creates ambiguity over where sentence-endings should be placed in this passage. This is reflected in differing modern translations, some of which attach this clause to {{bibleref2|Genesis|2:4||Genesis 2:4a}} and place a full stop at the end of 4b, while others place the full stop after 4a and make 4b the beginning of a new sentence, while yet others combine all verses from 4a onwards into a single sentence culminating in {{bibleref2|Genesis|2:7}}.</ref> | |||

| * Before any plant had appeared, before any rain had fallen, while a mist<ref group="note">in some translations, a stream</ref> watered the earth, Yahweh formed the man (Heb. ''ha-adam'' הָאָדָם) out of dust from the ground (Heb. ''ha-adamah'' הָאֲדָמָה), and breathed the breath of life into his nostrils. And the man became a "living being" (Heb. ''nephesh''). | |||

| * Yahweh planted a garden in Eden and he set the man in it. He caused pleasant trees to spout from the ground, and trees necessary for food, also the ] and the ].<ref group="note">Some modern translations alter the tense-sequence so that the garden is prepared before the man is set in it, but the Hebrew has the man created before the garden is planted.</ref> (An unnamed river is described: it goes out from Eden to water the garden, after which it parts into four named streams.) He takes the man who is to tend His garden and tells him he may eat of the fruit of all the trees except the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, "for in that day thou shalt surely die." | |||

| * Yahweh resolved to make a "helper"<ref group="note">''`ezer'': Most often used to refer to God, such as "The Lord is our Help (`ezer)"{{bibleref2c|Ps.|115:9}} and many other Old Testament verses. (Strong's H5828)</ref> suitable for (lit. "corresponding to")<ref>footnote Gen. 2:18 in NASB</ref> the man.<ref>Kvam, Kristen E., Linda S. Schearing, Valarie H. Ziegler, eds. ''Eve and Adam: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim readings on Genesis and gender.'' Indiana University Press, 1999. ISBN 0253212715.</ref> He made domestic animals and birds, and the man gave them their names, but none of them is a fitting helper. Therefore Yahweh caused the man to sleep, and he took a rib,<ref group="note">Hebrew ''tsela`'', meaning side, chamber, rib, or beam (Strong's H6763). Some feminist scholars have questioned the traditional "rib" on the grounds that it denigrates the equality of the sexes, suggesting it should read "side": see in ''Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought'', 9/22/1993 (accessed 09–12–2007).</ref> and from it formed a woman. The man then named her "Woman" (Heb. ''ishah''), saying "for from a man (Heb. ''ish'') has this been taken." A statement instituting marriage follows: "Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh."<ref group="note">The lack of punctuation in the Hebrew makes it uncertain whether or not these words about marriage are intended to be a continuation of the speech of the man.</ref> | |||

| * The man and his wife were naked, and felt no shame. | |||

| The primary accounts in each chapter are joined by a literary bridge at {{Bibleverse|Genesis|2:4}}, "These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth when they were created." This echoes the first line of Genesis 1, "In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth", and is reversed in the next phrase, "...in the day that the {{LORD}} God made the earth and the heavens". This verse is one of ten "generations" ({{langx|he|תולדות}} ''{{transl|he|toledot}}'') phrases used throughout Genesis, which provide a literary structure to the book.{{sfn|Cross|1973|pp=301ff}} They normally function as headings to what comes after, but the position of this, the first of the series, has been the subject of much debate.{{sfn|Thomas|2011| pp=27–28}} | |||

| === Genesis 1-11: Primeval History === | |||

| The overlapping stories of Genesis 1 and 2 are usually regarded as contradictory but also complementary,{{efn|name="two_stories"}}{{efn|name="Levenson_2004"}} with the first (the Priestly story) concerned with the creation of the entire ] while the second (the Jahwist story) focuses on man as moral agent and cultivator of his environment.{{sfn|Alter|1981|p=141}}{{efn|name="contradictory_complementary"}} | |||

| Genesis 1-2 opens the “primeval history” of Genesis 1-11. This unit within Genesis forms an introduction to the stories of Abraham and the Patriarchs, and contains the first mention of many themes which are continued throughout the book of Genesis and the Torah, including fruitfulness, God's election of Israel, and His ongoing forgiveness of man's rebellious nature. It is therefore impossible to understand either {{Bibleref2|Genesis|1-2}} or the Torah as a whole without reference to this introductory history.<ref group="note">For a schematic representation of the structure of the "primeval history", see (table i contains a breakdown of the "history"according to the documentary hypothesis); for a more detailed discussion, see (somewhat dated, but scholarly).</ref> | |||

| ===Mesopotamian influence=== | |||

| == Ancient Near East context == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{See also|Panbabylonism|Ancient near eastern cosmology}} | |||

| ] provides historical and cross-cultural perspectives for ]. Both sources behind the Genesis creation narrative were influenced by ],{{sfn|Lambert 1965}}{{sfn|Sarna|1997|p=50}}{{sfn|Levenson|2004|p=9}}{{sfn|Klamm|Winitzer|2023}} borrowing several themes from them but adapting them to ],{{sfn|Sarna|1997|p=50}}{{sfn|Klamm|Winitzer|2023}}{{efn|name="Mesopotamian_mythology"}} establishing a monotheistic creation in opposition to the polytheistic creation myth of ] neighbors.{{sfn|Leeming|2004}}{{sfn|Smith|2001}}{{page needed|date=January 2024}}{{sfn|Klamm|Winitzer|2023}}{{efn|name="balancing_act"}} | |||

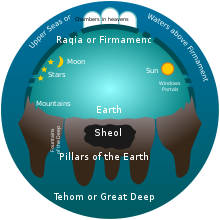

| Civilizations of the ] conceived the Earth as a flat disk with infinite water both above and below it.<ref name="seely">For a description of Near Eastern and other ancient cosmologies and their connections with the Biblical view of the Universe, see Paul H. Seeley, , and .</ref> The dome of the sky, was thought to be a solid metal bowl—tin according to the Sumerians, iron for the Egyptians—separating the surrounding water from the habitable world. The stars were embedded in the under surface of this dome, and there were gates in it that allowed the passage of the Sun and Moon back and forth. The flat-disk Earth was seen as a ] surrounded by a circular ocean, of which the known seas—what we call today the ], the ], and the ]—were inlets. Beneath the Earth was a fresh-water sea, the source of all fresh-water rivers and wells. It is this world-view which lies behind the Genesis creation story.<ref name="seely" /> | |||

| Genesis 1 bears striking similarities and differences with '']'', the ].{{sfn|Levenson|2004|p=9}} The myth begins with two primeval entities: ], the male freshwater deity, and ], the female saltwater deity. The first gods were born from their sexual union. Both Apsu and Tiamat were killed by the younger gods. ], the leader of the gods, builds the world with Tiamat's body, which he splits in two. With one half, he builds a dome-shaped ] in the sky to hold back Tiamat's upper waters. With the other half, Marduk forms dry land to hold back her lower waters. Marduk then organises the heavenly bodies and assigns tasks to the gods in maintaining the cosmos. When the gods complain about their work, Marduk creates humans out of the blood of the god ]. The grateful gods build a temple for Marduk in ].{{Sfn|Hayes|2012|p=29–33}} This is similar to the ], in which the Canaanite god ] builds himself a cosmic temple over seven days.{{Sfn|Smith|Pitard|2008|p=615}} | |||

| The Genesis creation story is comparable with other Near Eastern creation myths. According to the ], which has the closest parallels, the original state of the universe was a chaos formed by the mingling of two primeval waters, the female saltwater ] and the male freshwater ].<ref name="Bandstra 1999">{{citation|title=Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible|first=Barry L.|last=Bandstra|url=http://web.archive.org/web/20061212054040/hope.edu/bandstra/RTOT/CH1/CH1_1A3C.HTM|chapter=Enuma Elish|year=1999|publisher=Wadsworth Publishing Company}}.</ref> Through the fusion of their waters six successive generations of gods were born. A war amongst the gods began with the slaying of Apsu, and ended with the god ] splitting Tiamat in two to form the heavens and the earth; the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers emerged from her eye-sockets. Marduk then created humanity, from clay mingled with spit and blood, to tend the Earth for the gods, while Marduk himself was enthroned in Babylon in the ], "the temple with its head in heaven." | |||

| In both Genesis 1 and ''Enuma Elish'', creation consists of bringing order out of ]. Before creation, there was nothing but a ]. During creation, a dome-shaped firmament is put in place to hold back the water and make Earth habitable.{{Sfn|Coogan|Chapman|2018|p=34}} Both conclude with the creation of a human called "man" and the building of a temple for the god (in Genesis 1, this temple is the entire cosmos).{{sfn|McDermott|2002|pp=25–27}} In contrast to ''Enuma Elish'', Genesis 1 is monotheistic. There is no ] (account of God's origins), and there is no trace of the resistance to the reduction of chaos to order (Greek: ], lit. "God-fighting"), all of which mark the Mesopotamian creation accounts.{{sfn|Sarna|1997|p=50}} The gods in ''Enuma Elish'' are ], they have limited powers, and they create humans to be their ]. In Genesis 1, however, God is all powerful. He creates humans in the divine image, and cares for their wellbeing,{{Sfn|Hayes|2012|pp=33 & 35}} and gives them dominion over every living thing.{{Sfn|Coogan|Chapman|2018|p=35}} | |||

| The similarities between Genesis and the Enuma Elish are apparent, but there are significant differences. The most notable is the absence from Genesis of the "divine combat" (the gods' battle with Tiamat) which secures Marduk's position as king of the world, but even this has an echo in the claims of Yahweh's kingship over creation in such places as Psalm 29 and Psalm 93, where he is pictured as sitting enthroned over the floods.<ref name="Bandstra 1999"/> | |||

| ''Enuma Elish'' has also left traces on Genesis 2. Both begin with a series of statements of what did not exist at the moment when creation began; ''Enuma Elish'' has a spring (in the sea) as the point where creation begins, paralleling the spring (on the land – Genesis 2 is notable for being a "dry" creation story) in {{Bibleverse|Genesis|2:6}} that "watered the whole face of the ground"; in both myths, Yahweh/the gods first create a man to serve him/them, then animals and vegetation. At the same time, and as with Genesis 1, the Jewish version has drastically changed its Babylonian model: Eve, for example, seems to fill the role of a ] when, in {{Bibleverse|Genesis|4:1}}, she says that she has "created a man with Yahweh", but she is not a divine being like her Babylonian counterpart.{{sfn|Van Seters|1992|pp=122–24}} | |||

| == Exegetical points == | |||

| === "In the beginning..." === | |||

| Genesis 2 has close parallels with a second Mesopotamian myth, the ] epic – parallels that in fact extend throughout {{Bibleverse|Genesis|2–11}}, from the Creation to the ] and its aftermath. The two share numerous plot-details (e.g. the divine garden and the role of the first man in the garden, the creation of the man from a mixture of earth and divine substance, the chance of ], etc.), and have a similar overall theme: the gradual clarification of man's relationship with God(s) and animals.{{sfn|Carr|1996|p=242–248}} | |||

| The first word of Genesis 1 in Hebrew, "in the beginning" (Heb. ''b<sup>e</sup>rēšît'' בְּרֵאשִׁית), provides the traditional Jewish title for the book. The inherent ambiguity of the Hebrew grammar in this verse gives rise to two alternative translations, the first implying that God's initial act of creation was ''ab nihilo'' (out of nothing),<ref name="Wenham1">Wenham, Gordon. ''Word Biblical Commentary Vol. 1 Genesis 1-15.'' Word, 1987. ISBN 0849902002</ref> the second that "the heavens and the earth" (i.e., everything) already existed in a "formless and empty" state, to which God brings form and order:<ref name="ReferenceA">Harry Orlinsky, Notes on Genesis, NJPS translation of the Torah</ref> | |||

| ===Cosmology=== | |||

| # "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void…. God said, Let there be light!" (]). | |||

| Genesis 1–2 reflects ancient ideas about science: in the words of ], "on the subject of creation biblical tradition aligned itself with the traditional tenets of Babylonian science."{{sfn|Seidman|2010|p=166}} The opening words of Genesis 1, "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth", sum up the belief of the author(s) that ], the god of Israel, was solely responsible for creation and had no rivals.{{sfn|Wright|2002|p=53}} Later Jewish thinkers, adopting ideas from ], concluded that ], ] and ] penetrated all things and gave them unity.{{sfn|Kaiser|1997|p= 28}} Christianity in turn adopted these ideas and identified ] with the ]: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God" (]).{{sfn|Parrish|1990|pp= 183–84}} When the Jews came into contact with Greek thought, there followed a major reinterpretation of the underlying cosmology of the Genesis narrative. The biblical authors conceived the cosmos as a flat disc-shaped Earth in the centre, an underworld for the dead below, and heaven above.{{sfn|Aune|2003|p= 119}} Below the Earth were the "waters of chaos", the cosmic sea, home to mythic monsters defeated and slain by God; in Exodus 20:4, God warns against making an image "of anything that is in the waters under the earth".{{sfn|Wright|2002|p=53}} There were also waters above the Earth, and so the ''raqia'' (]), a solid bowl, was necessary to keep them from flooding the world.<ref>{{harvnb|Ryken et al|1998|p=170}}.</ref> During the ], this was largely replaced by a more "scientific" model as imagined by Greek philosophers, according to which the Earth was a sphere at the centre of concentric shells of celestial spheres containing the Sun, Moon, stars and planets.{{sfn|Aune|2003|p=119}} | |||

| # "At the beginning of the creation of heaven and earth, when the earth was (or the earth being) unformed and void.... God said, Let there be light!" (], and with variations ] and ]). | |||

| The idea that God created the world out of nothing (''creatio ]'') has become central today to Islam, Christianity, and Judaism – indeed, the medieval Jewish philosopher ] felt it was the only concept that the three religions shared{{sfn|Soskice|2010|p=24}} – yet it is not found directly in Genesis, nor in the entire Hebrew Bible.{{sfn|Nebe|2002|p= 119}} According to Walton, the Priestly authors of Genesis 1 were concerned not with the origins of matter (the material which God formed into the habitable cosmos), but with assigning roles so that the Cosmos should function.{{sfn|Walton|2006|p= 183}} John Day, however, considers that Genesis 1 clearly provides an account of the creation of the material universe.{{sfn|Day|2014|p=4}} Even so, the doctrine had not yet been fully developed in the early 2nd century AD, although early Christian scholars were beginning to see a tension between the idea of world-formation and the omnipotence of God; by the beginning of the 3rd century this tension was resolved, world-formation was overcome, and creation ''ex nihilo'' had become a fundamental tenet of Christian theology.{{sfn|May|2004|p=179}} | |||

| === The name of God === | |||

| ===Alternative biblical creation accounts=== | |||

| Two ] are used, '']'' in the first narrative and ''] Elohim'' in the second narrative. In Jewish tradition, dating back to the earliest rabbinic literature, the different names indicate different attributes of God.<ref>"Hashem/Elokim: Mixing Mercy with Justice" in ''The Aryeh Kaplan Reader'' </ref><ref>''The seventy faces of Torah: the Jewish way of reading the Sacred Scriptures'', by Stephen M. Wylen </ref> In modern times the two names, plus differences in the styles of the two chapters and a number of discrepancies between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, were instrumental in the development of ] and the ]. | |||

| The Genesis narratives are not the only biblical creation accounts. The Bible preserves two contrasting models of creation. The first is the "]" (speech) model, where a supreme God "speaks" dormant matter into existence. Genesis 1 is an example of creation by speech.{{sfn|Fishbane|2003|pp=34–35}} | |||

| The second is the "]" (struggle or combat) model, in which it is God's victory in battle over the monsters of the sea that mark his sovereignty and might.{{sfn|Fishbane|2003|p=35}} There is no complete combat myth preserved in the Bible. However, there are fragmentary allusions to such a myth in ], ], ]. These passages describe how God defeated the forces of chaos. These forces are ] as ]. These monsters are variously named ] (Sea), Nahar (River), ] (Coiled One), ] (Arrogant One), and ] (Dragon).{{Sfn|Sarna|1966|p=2}} | |||

| === "Without form and void" === | |||

| ] and Isaiah 51 recall a ] in which God creates the world by vanquishing the water deities: "Awake, awake! ... It was you that hacked Rahab in pieces, that pierced the Dragon! It was you that dried up the Sea, the waters of the great Deep, that made the abysses of the Sea a road that the redeemed might walk..."{{sfn|Hutton|2007|p=274}} | |||

| The phrase traditionally translated in English "without form and void" is ''tōhû wābōhû'' ({{lang-he|תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ}}). The Greek ] (LXX) rendered this term as "unseen and unformed" (]: ἀόρατος καὶ ἀκατασκεύαστος), paralleling the Greek concept of ]. In the Hebrew Bible, the phrase is a ], being used only in one other place.{{bibleref2c|Jer.|4:23|ESV}} There Jeremiah is telling Israel that sin and rebellion against God will lead to "darkness and chaos," or to "de-creation," "as if the earth had been ‘uncreated.’"<ref>H.B. Huey, vol. 16, Jeremiah, Lamentations, "The New American Commentary" (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2001, c1993), p. 85; Holladay, Jeremiah 1, p. 164; Thompson writes, "it's as if the earth had been ‘uncreated.’", Thompson, Jeremiah, NICOT, p. 230;</ref> | |||

| ==First narrative: Genesis 1:1–2:3== | |||

| === The rûach of God === | |||

| ]'' by ] (Copy D, 1794)]] | |||

| ===Background=== | |||

| The Hebrew ''rûach'' (רוּחַ) has the meanings "wind, spirit, breath," but the traditional Jewish interpretation here is "wind," as "spirit" would imply a living supernatural presence co-extent with yet separate from God at Creation. This, however, is the sense in which ''rûach'' was understood by the early Christian church in developing the doctrine of the ], in which this passage plays a central role.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> | |||

| The first creation account is divided into seven days during which God creates light (day 1); the sky (day 2); the earth, seas, and vegetation (day 3); the sun and moon (day 4); animals of the air and sea (day 5); and land animals and humans (day 6). God rested from his work on the seventh day of creation, the ].{{Sfn|Sarna|1966|pp=1–2}} | |||

| The use of numbers in ancient texts was often ] rather than factual – that is, the numbers were used because they held some symbolic value to the author.{{sfn|Hyers|1984|p=74}} The number seven, denoting divine completion, permeates Genesis 1: verse 1:1 consists of seven words, verse 1:2 has fourteen, and 2:1–3 has 35 words (5×7); Elohim is mentioned 35 times, "heaven/firmament" and "earth" 21 times each, and the phrases "and it was so" and "God saw that it was good" occur 7 times each.{{sfn|Wenham|1987|p=6}} | |||

| === The "deep" === | |||

| The cosmos created in Genesis 1 bears a striking resemblance to the ] in {{bibleverse|Exodus|35–40|HE}}, which was the prototype of the ] and the focus of priestly worship of ]; for this reason, and because other Middle Eastern creation stories also climax with the construction of a temple/house for the ], Genesis 1 can be interpreted as a description of the construction of the cosmos as God's house, for which the Temple in Jerusalem served as the earthly representative.{{sfn|Levenson|2004|p=13}} | |||

| The "deep" (Heb. תְהוֹם ]), is the formless body of primeval water surrounding the habitable world. These waters are later released during the ], when "all the fountains of the great deep burst forth" from under the earth and from the "windows" of the sky.{{bibleref2c|Gen.|7:11|ESV}} <ref name="GWenham" /> The word is cognate with the Babylonian ],<ref name="GWenham" /> and its occurrence here without the definite article ''ha'' (i.e., the literal translation of the Hebrew is that "darkness lay on the face of ''t<sup>e</sup>hôm'') indicates its mythical origins.<ref>Noted by ]—see , 2002, p.34.)</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Pre-creation (Genesis 1:1–2) === | ||

| :1 In the beginning God <nowiki>]<nowiki>]</nowiki>{{efn|The word translated "God" in Genesis 1:1–2 is ], and the word translated "Spirit" is {{lang|he-Latn|]}} ({{harvnb|Hayes|2012|pp=37–38}}).}} created the heaven and the earth. | |||

| :2 And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit <nowiki>]}}<nowiki>]</nowiki> of God moved upon the face of the waters.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Genesis|1:1–1:2|HE}}.</ref> | |||

| The opening phrase of ] is traditionally translated in English as "] God created".{{sfn|Walton|2001|p=69}} This translation suggests {{Lang|la|]}} ({{Gloss|creation from nothing}}).{{Sfn|Longman|2005|p=103}} The Hebrew, however, is ambiguous and can be translated in other ways.{{sfn|Bandstra|2008|pp=38–39}} The ] translates verses 1 and 2 as, "In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void{{nbsp}}..." This translation suggests that earth, in some way, already existed when God began his creative activity.{{Sfn|Longman|2005|pp=102–103}} | |||

| The "]" (Heb. רָקִיעַ ''rāqîa'') of heaven, created on the second day of creation and populated by luminaries on the fourth day, denotes a solid ceiling<ref name="seely" /> which separated the earth below from the heavens and their waters above. The term is ] derived from the verb ''rāqa'' (רֹקַע ), used for the act of beating metal into thin plates.<ref name="GWenham" /><ref name="Hamilton">{{cite book|title=The Book of Genesis (New International Commentary on the Old Testament)|author=Victor P. Hamilton|publisher=William B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, 1990}}</ref> | |||

| Biblical scholars ] and ] argue that Genesis 1:1 describes the initial creation of the universe, the former writing: "Since the inchoate earth and the heavens in the sense of the air/wind were already in existence in Gen. 1:2, it is most natural to assume that Gen. 1:1 refers to God's creative act in making them."{{sfn|Day|2021|pp=5–6}}{{sfn|Tsumura|2022|p=489}} Other scholars such as ], ], ], Cynthia Chapman, and ] argue that Genesis 1:1 describes the creation of an ordered universe out of preexisting, ] material.{{sfn|Hayes|2012|p=37}}{{sfn|Coogan|Chapman|2018|p=30}}{{sfn|Walton|2001|p=72}}{{sfn|Whybray|2001|p=43}} | |||

| === Great sea monsters === | |||

| The word "created" translates the Hebrew {{lang|he-Latn|bara'}}, a word used only for God's creative activity; people do not engage in {{lang|he-Latn|bara'}}.{{Sfn|Whybray|2001|p=42}} Walton argues that {{lang|he-Latn|bara'}} does not necessarily refer to the creation of matter. In the ], "to create" meant assigning roles and functions. The {{lang|he-Latn|bara'}} which God performs in Genesis 1 concerns bringing "heaven and earth" from chaos into ordered existence.{{sfn|Walton|2006|pp=183–184}} Day disputes Walton's functional interpretation of the creation narrative. Day argues that material creation is the "only natural way of taking the text" and that this interpretation was the only one for most of history.{{sfn|Day|2014|p=4}} | |||

| Heb. ''hatanninim hagedolim'' (הַתַּנִּינִם הַגְּדֹלִים) is the classification of creatures to which the chaos-monsters ] and ] belong.<ref></ref> In {{bibleref2|Genesis|1:21|HE}}, the proper noun Leviathan is missing and only the class noun great ''tannînim ''appears. The great ''tannînim'' are associated with mythological sea creatures such as ] (the Ugaritic counterpart of the biblical Leviathan) which were considered deities by other ancient near eastern cultures; the author of Genesis 1 asserts the sovereignty of Elohim over such entities.<ref name="Hamilton" /> | |||

| Most interpreters consider the phrase "heaven and earth" to be a ] meaning the entire cosmos.{{sfn|Walton|2001|p=728, note 17}} Genesis 1:2 describes the earth as "formless and void". This phrase is a translation of the Hebrew {{transl|he|]}} ({{lang|he|תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ}}).{{Sfn|Whybray|2001|pp=42–43}} {{lang|he-Latn|Tohu}} by itself means "emptiness, futility". It is used to describe the desert wilderness. {{lang|he-Latn|Bohu}} has no known meaning, although it appears to be related to the ] word ''bahiya'' ("to be empty"),{{sfn|Day|2014|p=8}} and was apparently coined to rhyme with and reinforce {{lang|he-Latn|tohu}}.{{sfn|Alter|2004|p=17}} The phrase appears also in ] where the prophet warns ] that rebellion against God will lead to the return of darkness and chaos, "as if the earth had been 'uncreated'".{{sfn|Thompson|1980|p=230}} | |||

| === The number seven === | |||

| Verse 2 continues, "''darkness'' was upon the face of the ''deep''". The word ''deep'' translates the Hebrew {{lang|he-Latn|]}} ({{lang|he|תְהוֹם}}), a ]. Darkness and {{lang|he-Latn|təhôm}} are two further elements of chaos in addition to {{lang|he-Latn|tohu wa-bohu}}. In ''Enuma Elish'', the watery deep is personified as the goddess ], the enemy of ]. In Genesis, however, there is no such personification. The elements of chaos are not seen as evil but as indications that God has not begun his creative work.{{sfn|Walton|2001|pp=73–74}} | |||

| ] denoted divine completion.<ref>Meir Bar-Ilan, ''The Numerology of Genesis'' (Association for Jewish Astrology and | |||

| Numerology, 2003)</ref> It is embedded in the text of Genesis 1 (but not in Genesis 2) in a number of ways, besides the obvious ]: the word "God" occurs 35 times (7 × 5) and "earth" 21 times (7 × 3). The phrases "and it was so" and "God saw that it was good" occur 7 times each. The first sentence of {{bibleref2|Genesis|1:1|HE}} contains 7 Hebrew words, and the second sentence contains 14 words, while the verses about the seventh day{{bibleref2c|Gen.|2:1-3|HE}} contain 35 words in total.<ref>], Genesis 1-15 (Commentary, Word Books, 1987. p. 6</ref> | |||

| Verse 2 concludes with, "And the {{lang|he-Latn|ruach}} of God moved upon the face of the waters." There are several options for translating the Hebrew word {{lang|he-Latn|ruach}} ({{lang|he|רוּחַ}}). It could mean "breath", "wind", or "spirit" in different contexts. The traditional translation is "spirit of God".{{sfn|Blenkinsopp|2011|p=33}} In the Hebrew Bible, the spirit of God is understood to be an extension of God's power. The term is analogous to saying the "hand of the Lord" ({{bibleref|2 Kings|3:15}}). Historically, Christian theologians supported "spirit" as it provided biblical support for the presence of the ], the third person of the ], at creation.{{sfn|Walton|2001|pp=76–77}} | |||

| === Man and the image of God === | |||

| Other interpreters argue for translating {{lang|he-Latn|ruach}} as "wind". For example, the NRSV renders it "wind from God".{{Sfn|Whybray|2001|p=43}} Likewise, the word ''{{transl|he|elohim}}'' can sometimes function as a superlative adjective (such as "mighty" or "great"). The phrase ''{{transl|he|ruach elohim}}'' may therefore mean "great wind". The connection between wind and watery chaos is also seen in the ], where God uses wind to make the waters subside in Genesis 8:1.{{sfn|Blenkinsopp|2011|pp=33–34}}{{sfn|Walton|2001|pp=74–75}} | |||

| The meaning of the "]" has been much debated. The ancient Jewish philosopher ] and the medieval Jewish scholar ] believed it referred to "a sort of conceptual archetype, model, or blueprint that God had previously made for man;" his colleague ] suggested it referred to man's ].<ref></ref> Modern scholarship still debates whether the image of God was represented symmetrically in Adam and Eve, or whether Adam possessed the image more fully than the woman. | |||

| In ''Enuma Elish'', the storm god Marduk defeats Tiamat with his wind. While stories of a cosmic battle prior to creation were familiar to ancient Israelites {{See above|]}}, there is no such battle in Genesis 1 though the text includes the primeval ocean and references to God's wind. Instead, Genesis 1 depicts a single God whose power is uncontested and who brings order out of chaos.{{sfn|Hayes|2012|pp=38–39}} | |||

| == Structure and composition == | |||

| {{anchor|The six days of Creation: Genesis 1:3-2:3}} | |||

| ]'s painting of the ceiling of the ] shows the creation of the stars and planets as described in the first chapter of ].]] | |||

| ===Six days of Creation (1:3–2:3)=== | |||

| === Structure === | |||

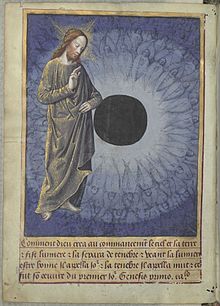

| ] from the ''{{ill|Heures de Louis de Laval|fr}}'' (see ])]] | |||

| {{See also|Framework interpretation}} | |||

| Genesis 1 consists of eight acts of creation within a six day framework. In each of the first three days there is an act of division: Day one divides the darkness from light; day two, the waters from the skies; and day three, the sea from the land. In each of the next three days these divisions are populated: day four populates what was created on day one, and heavenly bodies are placed in the darkness and light; day five populates what was created on day two, and fish and birds are placed in the seas and skies; finally, day six populates what was created on day three, and animals and man are place on the land. This six-day structure is symmetrically bracketed: On day zero primeval chaos reigns, and on day seven there is cosmic order.<ref>{{citation|title=Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible|first=Barry L.|last=Bandstra|url=http://web.archive.org/web/20061212054040/hope.edu/bandstra/RTOT/CH1/CH1_1A1.HTM|chapter=Priestly Creation Story|year=1999|publisher=Wadsworth Publishing Company}}.</ref> | |||

| Creation takes place over six days. The creative acts are arranged so that the first three days set up the environments necessary for the creations of the last three days to thrive. For example, God creates light on the first day and the light-producing heavenly bodies on the fourth day.{{Sfn|Coogan|Chapman|2018|p=30}} | |||

| {{bibleref2|Genesis|2}} is a simple linear narrative, with the exception of the parenthesis about the four rivers at {{bibleref2c-nb|Genesis|2:10-14}}. This interrupts the forward movement of the narrative and is possibly a later insertion.<ref>.</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| The two are joined by {{bibleref2|Genesis|2:4||Genesis 2:4a}}, "These are the ''tôl<sup>e</sup>dôt'' (תוֹלְדוֹת in Hebrew) of the heavens and the earth when they were created." This echoes the first line of Genesis 1, "In the beginning Yahweh created both the heavens and the earth," and is reversed in the next line of Genesis 2, "In the day when Yahweh Elohim made the earth and the heavens...". The significance of this, if any, is unclear, but it does reflect the preoccupation of each chapter, Genesis 1 looking down from heaven, Genesis 2 looking up from the earth.<ref>Richard Elliott Friedman, "The Bible With Sources Revealed", (Harper San Francisco, 2003), fn 3, p. 35</ref> | |||

| |+Days of Creation{{Sfn|Coogan|Chapman|2018|p=30}} | |||

| |Day 1 | |||

| |light | |||

| |Day 4 | |||

| |celestial bodies | |||

| |- | |||

| |Day 2 | |||

| |sea and firmament | |||

| |Day 5 | |||

| |birds and fish | |||

| |- | |||

| |Day 3 | |||

| |land and plants | |||

| |Day 6 | |||

| |land animals and humans | |||

| |} | |||

| Each day follows a similar literary pattern:{{Sfn|Arnold|1998|p=23}} | |||

| === Composition === | |||

| # Introduction: "And God said" | |||

| ]'s The ] (1512) is the most famous Fresco in the ]]] | |||

| # Command: "Let there be" | |||

| # Report: "And it was so" | |||

| # Evaluation: "And God saw that it was good" | |||

| # Time sequence: "And there was evening, and there was morning" | |||

| Verse 31 sums up all of creation with, "God saw every thing that He had made, and, indeed, it was very good". According to biblical scholar ], "This is the craftsman's assessment of his own work{{nbsp}}... It does not necessarily have an ethical connotation: it is not mankind that is said to be 'good', but God's work as craftsman."{{Sfn|Whybray|2001|p=42}} | |||

| According to the tradition the first five books of the Bible were written by Moses, but today many scholars accept that the Pentateuch "was in reality a composite work, the product of many hands and periods.”<ref>{{cite book|last=Speiser|first=E. A.|authorlink=E. A. Speiser|title=Genesis|series=The ]|year=1964|publisher=Doubleday|isbn=0-385-00854-6|page=XXI}}</ref> In the first half of the 20th century the dominant theory regarding its origins was the ], which supposes that the Torah was produced about 450 BC by combining four distinct, complete and coherent documents, with Genesis 1 from one source (called ] ), and Genesis 2 from another (] ).<ref> describes both the documentary hypothesis and the Mosaic authorship tradition.</ref> Since the last quarter of the 20th century there has been renewed interest in alternative theories which see (Genesis 1) as an editor adding to an existing document, rather than as a complete and independent document; like the documentary hypothesis, contemporary theories also see Genesis 1-2, with their strong Babylonian influence and anti-Babylonian agenda, as a product of the exilic and post-exilic period (6th-5th centuries BC).<ref>E.O. James. "Creation and Mythology: A Historical and Comparative Inquiry", (1969), pp.28 ff</ref> The renewed emphasis on the final form of the biblical text has also tended to redirect attention to its overarching theological coherence.<ref>Rabbi Yitzchak Etshalom, ""</ref> | |||

| At the end of the sixth day, when creation is complete, the world is a cosmic temple in which the role of humanity is the worship of God. This parallels ''Enuma Elish'' and also echoes ], where God recalls how the stars, the "]", sang when the corner-stone of creation was laid.{{sfn|Blenkinsopp|2011|pp=21–22}} | |||

| == Theology and interpretation == | |||

| === Questions of genre === | |||

| ====First day (1:3–5)==== | |||

| The ] of Genesis 1-2 (and {{bibleref2|Genesis|1-11}}, the larger whole to which the two chapters belong) remains subject to differences of opinion, and modern scholars can only make informed judgments. One inevitable conclusion is that Genesis 1-2 represent theology: the chapters concern the actions of God and the meaning of those acts. Possibly, the authors also believed they were writing a scientific, accurate description of the cosmos and its beginnings as known to them: a flat earth surrounded by infinite water and a solid sky-dome set with stars. A recent study of the numerological basis of Genesis speculated about the authors' possible intentions to give "a scientific description of Creation from the perspective of ritual, and without ]."<ref>Meir Bar-Ilan, The Numerology of Genesis", (Rehovot: Association for Jewish Astrology and Numerology, 2003), pp. vi + 218</ref> The story is also presented with a clear chronological progression as part of a history that leads from the moment of first creation to the destruction of the First Temple. This led ] to classify it as "mythical history".<ref>Thorkild Jacobsen, "The Eridu Genesis", (JBL 100, 1981), pp.513-29</ref> | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| 3 And God said: 'Let there be light.' And there was light. 4 And God saw the light, that it was good; and God divided the light from the darkness. 5 And God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, one day.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Genesis|1:3–1:5|HE}}</ref>}} | |||

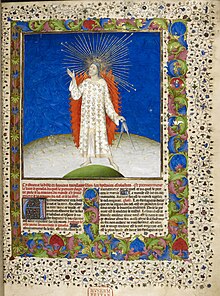

| The process of creation illustrates God's sovereignty and ]. God creates by fiat; things come into existence by divine decree.{{Sfn|Arnold|1998|p=26}} Like a king, God has merely to speak for things to happen.{{sfn|Bandstra|2008|p=39}} On day one, God creates light and separates the light from the darkness. Then he names them.{{Sfn|Whybray|2001|p=43}} God therefore creates time.{{sfn|Walton|2001|p=79}} | |||

| === The theology of Genesis 1-2 === | |||

| Creation by speech is not found in Mesopotamian mythology, but it is present in some ].{{sfn|Walton|2003|p=158}} While some Egyptian accounts have a god creating the world by sneezing or masturbating, the ] has ] create by speech.{{Sfn|Longman|2005|p=74}} In Genesis, creative acts begin with speech and are finalized with naming. This has parallels in other ancient Near Eastern cultures. In the Memphite Theology, the creator god names everything. Similarly, ''Enuma Elish'' begins when heaven, earth, and the gods were unnamed. Walton writes, "In this way of thinking, things did not exist unless they were named."{{sfn|Walton|2003|p=158}} According to biblical scholar ], this similarity is "wholly superficial" because in other ancient narratives creation by speech involves ]:{{Sfn|Sarna|1966|p=12}} | |||

| Traditional Jewish scholarship has viewed it as expressing spiritual concepts (see ], commentary on Genesis). The ] in Tractate ] states that the actual meaning of the creation myth, mystical in nature and hinted at in the text of Genesis, was to be taught only to advanced students one-on-one. Tractate ] states that Genesis describes all mankind as being descended from a single individual in order to teach certain lessons. Among these are: | |||

| {{blockquote|The pronouncement of the right word, like the performance of the right magical actions, is able to, or rather, inevitably must, actualize the potentialities which are inherent in the inert matter. In other words, it implies a mystic bond uniting matter to its manipulator{{nbsp}}... Worlds apart is the Genesis concept of creation by divine fiat. Notice how the Bible passes over in absolute silence the nature of the matter—if any—upon which the divine word acted creatively. Its presence or absence is of no importance, for there is no tie between it and God. "Let there be!" or, as the Psalmist echoed it, "He spoke and it was so," refers not to the utterance of the magic word, but to the expression of the omnipotent, sovereign, unchallengeable will of the absolute, transcendent God to whom all nature is completely subservient.}} | |||

| * Taking one life is tantamount to destroying the entire world, and saving one life is tantamount to saving the entire world. | |||

| * A person should not say to another that he comes from better stock because we all come from the same ancestor. | |||

| * To teach the greatness of God, for when human beings create a mold every thing that comes out of that mold is identical, while mankind, which comes out of a single mold, is different in that every person is unique.<ref name="ReferenceB"/> | |||

| ====Second day (1:6–8)==== | |||

| Among the many views of modern scholars on Genesis and creation one of the most influential is that which links it to the emergence of Hebrew ] from the common ]n/Levantine background of ] religion and myth around the middle of the 1st millennium BC.<ref>For a discussion of the roots of Biblical monotheism in Canaanite polytheism, see ; See also the review of , which describes some of the nuances underlying the subject. See the Bibliography section at the foot of this article for further reading on this subject.</ref> The "Creation week" narrative forms a monotheistic ] on creation-theology directed against pagan creation myths, the sequence of events building to the establishment of the ] (in Hebrew: שַׁבָּת, ]) commandment as its climax.<ref name="MK1" /> Where the Babylonian myths saw man as nothing more than a "lackey of the gods to keep them supplied with food,"<ref>T. Jacobson, "The Eridu Genesis", JBL 100, 1981, pp.529, quoted in Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: The Pentateuch", 2003, p.17. See also {{cite book|title=Genesis 1-15 (Word Biblical Commentary)|author=]|publisher=Word Books, Texas, 1987}}</ref> Genesis starts out with God approving the world as "very good" and with mankind at the apex of created order.{{Bibleref2c|Gen.|1:31}} Things then fall away from this initial state of goodness: Adam and Eve eat the fruit of the tree in disobedience of the divine command. Ten generations later in the time of ], the Earth has become so corrupted that God resolves to return it to the waters of chaos sparing only one man who is righteous and from whom a new creation can begin. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| == Creationism == | |||

| 6 And God said: 'Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.' 7 And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament; and it was so. 8 And God called the firmament Heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, a second day.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Genesis|1:6–1:8|HE}}</ref>}} | |||

| {{creationism2}} | |||

| {{See also|Creationism|Creation-evolution controversy}} | |||

| On day two, God creates the ] ({{lang|he-Latn|rāqîa}}), which is named {{lang|he-Latn|šamayim}} ({{Gloss|sky}} or {{Gloss|heaven}}),{{Sfn|Walton|2001|p=111}} to divide the waters. Water was a "primal generative force" in pagan mythologies. In Genesis, however, the primeval ocean possesses no powers and is completely at God's command.{{Sfn|Sarna|1966|p=13}} | |||

| ] springs from the belief that if one element of the biblical narrative is shown to be untrue, then all others will follow: "Tamper with the Book of Genesis and you undermine the very foundations of Christianity.... If {{Bibleref2|Genesis|1}} is not accurate, then there's no way to be certain that the rest of Scripture tells the truth."<ref>Literalist minister/theologian John MacArthur, in Eugenie C. Scott, "Evolution vs Creationism: An Introduction", University of California Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0520246508, pp. 227-8</ref> Thus a literal genre, ''Genesis as history'', is substituted for the symbolic ''Genesis as theology'', and the text is placed in conflict with science.<ref>Conrad Hyers, "The Meaning of Creation: Genesis and Modern Science", 1984, p. 75</ref> ] believe that the seven "days" of {{Bibleref2|Genesis|1}} correspond to normal 24-hour days while ] creationists, more willing to adjust their religious beliefs to accommodate current scientific findings, hold that each "day" represents an "age" of perhaps millions or even billions of years. Creationists read {{Bibleref2|Genesis|2}} as history, holding that God breathed into the nostrils of a being formed out of dust, and from his side (or rib) the first woman was formed.<ref></ref> | |||

| {{lang|he-Latn|Rāqîa}} is derived from {{lang|he-Latn|rāqa'}}, the verb used for the act of beating metal into thin plates.{{sfn|Hamilton|1990|p=122}} Ancient people throughout the world believed the sky was solid, and the firmament in Genesis 1 was understood to be a solid dome.{{sfn|Seeley|1991|pp=228 & 235}} In ], the earth is a ] surrounded by the waters above and the waters below. The firmament is a solid dome that rests on mountains at the edges of the earth. It is transparent, allowing men to see the blue of the waters above with "windows" to allow rain to fall. The sun, moon and stars are underneath the firmament. Deep within the earth is the ] or ]. The earth is supported by pillars sunk into the waters below.{{sfn|Knight|1990|p=175}} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| The waters above are the source of precipitation, so the function of the {{lang|he-Latn|rāqîa}} was to control or regulate the weather.{{Sfn|Walton|2001|pp=112–113}} In the ], "all the fountains of the great deep burst forth" from the waters beneath the earth and from the "windows" of the sky.{{sfn|Wenham|2003a|p=29}} | |||

| ====Third day (1:9–13)==== | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| And God said: 'Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear.' And it was so. 10 And God called the dry land Earth, and the gathering together of the waters called He Seas; and God saw that it was good. 11 And God said: 'Let the earth put forth grass, herb yielding seed, and fruit-tree bearing fruit after its kind, wherein is the seed thereof, upon the earth.' And it was so. 12 And the earth brought forth grass, herb yielding seed after its kind, and tree bearing fruit, wherein is the seed thereof, after its kind; and God saw that it was good. 13 And there was evening and there was morning, a third day.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Genesis|1:9–1:13|HE}}</ref>}} | |||

| By the end of the third day God has created a foundational environment of light, heavens, seas and earth.{{sfn|Bandstra|2008|p=41}} God does not create or make trees and plants, but instead commands the earth to produce them. The underlying theological meaning seems to be that God has given the previously barren earth the ability to produce vegetation, and it now does so at his command. "According to (one's) kind" appears to look forward to the laws found later in the Pentateuch, which lay great stress on holiness through separation.{{sfn|Kissling|2004|p=106}} | |||

| In the first three days, God set up time, climate, and vegetation, all necessary for the proper functioning of the cosmos. For ancient peoples living in an ], climatic or agricultural disasters could cause widespread suffering through famine. Nevertheless, Genesis 1 describes God's original creation as "good"—the natural world was not originally a threat to human survival.{{Sfn|Walton|2001|pp=115–116}} | |||

| The three levels of the cosmos are next populated in the same order in which they were created—heavens, sea, earth. | |||

| ====Fourth day (1:14–19)==== | |||

| ] (c. 1411)]] | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| 14 And God said: 'Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days and years; 15 and let them be for lights in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth.' And it was so. 16 And God made the two great lights: the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night; and the stars. 17 And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth, 18 and to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness; and God saw that it was good. 19 And there was evening and there was morning, a fourth day.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Genesis|1:14–1:19|HE}}</ref>}} | |||

| On the first day, God makes light (Hebrew:{{lang|he-Latn|'ôr}}). On the fourth day, God makes "lights" or "lamps" (Hebrew:{{lang|he-Latn|mā'ôr}}) set in the firmament.{{sfn|Walsh|2001|p=37 (footnote 5)}} This is the same word used elsewhere in the Pentateuch for the lampstand or ] in the ], another reference to the cosmos being a temple.{{Sfn|Walton|2001|p=124}} Specifically, God creates the "greater light", the "lesser light", and the stars. According to ], most scholars agree that the choice of "greater light" and "lesser light", rather than the more explicit "sun" and "moon", is anti-mythological rhetoric intended to contradict widespread contemporary beliefs in ] and ].{{sfn|Hamilton|1990|p=127}} Indeed, ] posits that the account of the fourth day reveals that the sun and the moon operate only according to the will of God, and so demonstrates that it is foolish to worship them.{{sfn|Collins|2006|p=57}} | |||

| On day four, the language of "ruling" is introduced. The heavenly bodies will "govern" day and night and mark seasons, years and days. This was a matter of crucial importance to the ], as the ] were organised around the cycles of both the sun and moon in a ] that could have either 12 or 13 months.{{sfn|Bandstra|2008|pp=41–42}} | |||

| In Genesis 1:17, the stars are set in the firmament. In Babylonian myth, the heavens were made of various precious stones with the stars engraved in their surface (compare Exodus 24:10 where the elders of Israel see God on the sapphire floor of heaven).{{sfn|Walton|2003|pp=158–59}} | |||

| ====Fifth day (1:20–23)==== | |||

| {{quote|And God said: 'Let the waters swarm with swarms of living creatures, and let fowl fly above the earth in the open firmament of heaven.' 21 And God created the great sea-monsters, and every living creature that creepeth, wherewith the waters swarmed, after its kind, and every winged fowl after its kind; and God saw that it was good. 22 And God blessed them, saying: 'Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the waters in the seas, and let fowl multiply in the earth.' 23 And there was evening and there was morning, a fifth day.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Genesis|1:20–1:23|HE}}</ref>}} | |||

| On day five, God creates animals of the sea and air. In Genesis 1:20, the Hebrew term {{Lang|he-latn|nepeš ḥayya}} ({{gloss|living creatures}}) is first used. They are of higher status than all that has been created before this, and they receive God's ].{{Sfn|Whybray|2001|p=43}} | |||

| The Hebrew word {{lang|he-Latn|]}} (translated as "sea creatures" or "sea monsters") in Genesis 1:21 is used elsewhere in the Bible in reference to ] named ] and ] (]:13, ]:1 and ]:9). In Egyptian and Mesopotamian mythologies ('']'' and ''Enuma Elish''), the creator-god has to do battle with the sea-monsters before he can make heaven and earth. In Genesis, however, there is no hint of combat, and the {{lang|he-Latn|tannin}} are simply creatures created by God. The Genesis account, therefore, is an explicit ] against the mythologies of the ancient world.{{sfn|Walton|2003|p=160}} | |||

| ====Sixth day (1:24–31)==== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| 24 And God said: 'Let the earth bring forth the living creature after its kind, cattle, and creeping thing, and beast of the earth after its kind.' And it was so. 25 And God made the beast of the earth after its kind, and the cattle after their kind, and every thing that creepeth upon the ground after its kind; and God saw that it was good. | |||

| 26 And God said: 'Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.' 27 And God created man in His own image, in the image of God created He him; male and female created He them. 28 And God blessed them; and God said unto them: 'Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that creepeth upon the earth.' 29 And God said: 'Behold, I have given you every herb yielding seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed—to you it shall be for food; 30 and to every beast of the earth, and to every fowl of the air, and to every thing that creepeth upon the earth, wherein there is a living soul, every green herb for food.' And it was so.31 And God saw every thing that He had made, and, behold, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day.<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|1:24–31|HE}}</ref>}} | |||

| On day six, God creates land animals and humans. Like the animals of the sea and air, the land animals are designated {{Lang|he-latn|nepeš ḥayya}} ({{gloss|living creatures}}). They are divided into three categories: domesticated animals ({{Lang|he-latn|behema}}), whild herd animals that serve as prey ({{Lang|he-latn|remeś}}), and wild predators ({{Lang|he-latn|ḥayya}}). The earth "brings forth" animals in the same way that it brought forth vegetation on day three.{{Sfn|Walton|2001|p=127}} | |||

| In Genesis 1:26, God says "Let ''us'' make man{{nbsp}}..." This has given rise to several theories, of which the two most important are that "us" is ],{{sfn|Davidson|1973|p=24}} or that it reflects a setting in a ] with God enthroned as king and proposing the creation of mankind to the lesser divine beings.{{sfn|Levenson|2004|p=14}} A traditional interpretation is that "us" refers to a plurality of persons in the Godhead, which reflects ]. Some justify this by stating that the plural reveals a "duality within the Godhead" that recalls the "Spirit of God" mentioned in verse 2; "And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters".{{sfn|Hamilton|1990|p=133-134}} | |||

| The creation of mankind is the climax of the creation account and God's implied purpose for creating the world. Everything created up to this point was made for humanity's use.{{Sfn|Whybray|2001|p=42}} Man was created in the "]". The meaning of this is unclear but suggestions include:{{sfn|Kvam et al. 1999|p=24}}{{sfn|Kline|2016|p=13}} | |||

| # Having the spiritual qualities of God such as intellect, will, etc.; | |||

| # Having the physical form of God; | |||

| # A combination of these two; | |||

| # Being God's counterpart on Earth and able to enter into a relationship with him; | |||

| # Being God's representative or ] on Earth; | |||

| # Having dominion over Creation like the angels in {{bibleverse|Psalm|8:5|KJV}}; | |||

| # Moral excellence and the possibility of glorification (cf. {{bibleverse|Ephesians|4:24|KJV}}; {{bibleverse|Galatians|3:10|KJV}}; {{bibleverse|1 Corinthians|15:49-58|KJV}}). | |||

| When in Genesis 1:26 God says "Let us make man", the Hebrew word used is ''adam''; in this form it is a generic noun, "mankind", and does not imply that this creation is male. After this first mention the word always appears as ''ha-adam'', "the man", but as Genesis 1:27 shows ("So God created man in his '''' image, in the image of God created He him; male and female created He them."), the word is still not exclusively male.{{sfn|Alter|2004|pp=18–19, 21}} | |||

| God blesses humanity, commanding them to reproduce, "subdue" ({{Lang|he-latn|kbš}}) the earth and "rule" ({{Lang|he-latn|rdh}}) over it, in what is known as the ]. Humanity is to extend the Kingdom of God beyond Eden, and, imitating the Creator-God, is to labour to bring the earth into its service, to the end of the fulfilment of the mandate.{{sfn|Kline|2016|pp=13-14}} This would include the procreation of offspring, the subjugation and replenishment of the earth (e.g., the use of natural resources), dominion over creatures (e.g., animal domestication), labor in general, and marriage.{{sfn|Collins|2006|p=130}}{{sfn|Walton|2001|p=132}} God tells the animals and humans that he has given them "the green plants for food"{{snd}}creation is to be ]. Only later, after the Flood, is man given permission to eat flesh. The Priestly author of Genesis appears to look back to an ideal past in which mankind lived at peace both with itself and with the animal kingdom, and which could be re-achieved through a proper sacrificial life in ].{{sfn|Rogerson|1991|pp=19ff}} | |||

| Upon completion, God sees that "every thing that He had made ... was very good" ({{Bibleverse|Genesis|1:31|HE}}). According to ], this implies that the materials that existed before the Creation ("'']''," "darkness", "'']''") were not "very good". He thus hypothesized that the Priestly source set up this dichotomy to mitigate ].{{sfn|Knohl|2003|p=13}} However according to Collins, since the creation of man is the climax of the first creation account, "very good" must signify the presentation of man as the crown of God's creation, which is to serve him.{{sfn|Collins|2006|p=78}} | |||

| ====Seventh day: divine rest (2:1–3)==== | |||

| ]'' by ]]] | |||

| {{quote| | |||

| And the heaven and the earth were finished, and all the host of them. 2 And on the seventh day God finished His work which He had made; and He rested on the seventh day from all His work which He had made. 3 And God blessed the seventh day, and hallowed it; because that in it He rested from all His work which God in creating had made.<ref>{{Bibleverse|Genesis|2:1–2:3|HE}}</ref>}} | |||

| These three verses belong with and complete the narrative in chapter 1.<ref>] (1905), in ''Ellicott's Commentary for Modern Readers'', accessed on 6 October 2024</ref> Creation is followed by "rest".<ref>{{bibleverse|Genesis|2:2}}</ref> In ancient Near Eastern literature the divine rest is achieved in a temple as a result of having brought order to chaos. Rest is both disengagement, as the work of creation is finished, but also engagement, as the deity is now present in his temple to maintain a secure and ordered cosmos.{{sfn|Walton|2006|pp=157–58}} Compare with Exodus 20:8–20:11: "Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days shalt thou labour, and do all thy work; but the seventh day is a sabbath unto the {{LORD}} thy {{GOD}}, in it thou shalt not do any manner of work, thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter, nor thy man-servant, nor thy maid-servant, nor thy cattle, nor thy stranger that is within thy gates; for in six days the {{LORD}} made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested on the seventh day; wherefore the {{LORD}} blessed the sabbath day, and hallowed it." | |||

| ==Second narrative: Genesis 2:4–2:25== | |||

| ], 1534]] | |||

| Genesis 2–3, the ] story, was probably authored around 500 BCE as "a discourse on ideals in life, the danger in human glory, and the fundamentally ambiguous nature of humanity – especially human mental faculties".{{sfn|Stordalen|2000|pp=473–74}} The Garden in which the action takes place lies on the mythological border between the human and the divine worlds, probably on the far side of the ] near the rim of the world; following a conventional ancient Near Eastern concept, the Eden river first forms that ocean and then divides into four rivers which run from the four corners of the earth towards its centre.{{sfn|Stordalen|2000|pp=473–74}} According to ], who represents ] and the ], the narrative establishes the site of the "climactic probation test", which is also where the "covenant crisis" of Genesis 3 occurs.{{sfn|Kline|2016|pp=17—18}} | |||

| The ] that constitutes the second narrative is generally taken to begin at {{bibleref|Genesis|2:4|KJV}} ("These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth when they were created, in the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens,") because it is widely recognized as a ] (in the following quote, each subject of the chiasmus is preceded by "" to denote its place in the chiastic configuration; "These are the generations of the heavens and of the earth when they were created in the day that the {{sc|Lord}} God made the earth and the heavens").{{sfn|Collins|2006|p=41, 109}} | |||

| === The origin of humanity and plant life (2:4–7) === | |||

| The content of the verse 4 opening is a set introduction similar to those found in Babylonian myths.{{sfn|Van Seters|1998|p=22}} Before the man is created, the earth is a barren waste watered by an ''’êḏ'' ({{Script/Hebrew|אד}}); {{bibleverse|Genesis|2:6|KJV}} of the ] has the translation "mist" for this word, following Jewish practice. Since the mid-20th century, Hebraists have generally accepted that the real meaning is "spring of underground water".{{sfn|Andersen|1987|pp=137–40}} | |||

| In Genesis 1 the characteristic word for God's activity is ''bara'', "created"; in Genesis 2 the word used when he creates the man is ''yatsar'' ({{Script/Hebrew|ייצר}} ''yîṣer''), meaning "fashioned", a word used in contexts such as a potter fashioning a pot from clay.{{sfn|Alter|2004|pp=20, 22}} God breathes his own breath into the clay and it becomes '']'' ({{Script/Hebrew|נֶ֫פֶשׁ}}), a word meaning "life", "vitality", "the living personality"; man shares ''nephesh'' with all creatures, but the text describes this life-giving act by God only in relation to man.{{sfn|Davidson|1973|p=31}} | |||

| === The Garden of Eden (2:8–14) === | |||

| {{Main|Garden of Eden}} | |||

| The word "Eden" comes from a root meaning "]": the first man is to work in God's miraculously fertile garden.{{sfn|Levenson|2004|p=15}} The "]" is a motif from Mesopotamian myth: in the '']'' (c. 1800 BCE){{efn|"The story of Adam and Eve's sin in the garden of Eden (2.25–3.24) displays similarities with Gilgamesh, an epic poem that tells of how its hero lost the opportunity for immortality and came to terms with his humanity. the biblical narrator has adapted the Mesopotamian forerunner to Israelite theology" ({{harvnb |Levenson|2004|p=9}}).}} the hero is given a plant whose name is "man becomes young in old age", but a serpent steals the plant from him.{{sfn|Davidson|1973|p=29}} Kline regards the tree of life as a symbol or seal of the reward of eternal life for successful fulfilment of the covenant by humanity.{{sfn|Kline|2016|p=19}} There has been much scholarly discussion about the type of knowledge given by the second tree. Suggestions include: human qualities, sexual consciousness, ethical knowledge, or universal knowledge; with the last being the most widely accepted.{{sfn|Kooij|2010|p=17}} In Eden, mankind has a choice between wisdom and life, and chooses the first, although God intended them for the second.{{sfn|Propp|1990|p=193}} | |||