| Revision as of 04:44, 3 February 2010 view sourceVertebralcompressionfractures (talk | contribs)11 edits Dr Clark, an investigator in the Kallmes Study in editorial correspondence within NEJM questioned/disagreed the results of the trials. See NEJM361(21):2097-2098← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:23, 16 May 2024 view source WOSlinker (talk | contribs)Administrators854,737 editsm fix italics | ||

| (420 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Type of spinal procedure}} | |||

| '''Vertebroplasty''' is a ] spinal procedure where bone cement is injected through a small hole in the skin (]) into a fractured ] with the goal of relieving the pain of osteoporotic compression fractures. | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{Infobox medical intervention | |||

| | Name = Percutaneous vertebroplasty | |||

| | Image = Aufbau Kypho.jpg | |||

| | Caption = Typical interventional suite setup for kyphoplasty | |||

| | ICD10 = | |||

| | ICD9 = {{ICD9proc|81.65}} | |||

| | MeshID = | |||

| | MedlinePlus = 007512 | |||

| | OPS301 = | |||

| | OtherCodes = | |||

| | HCPCSlevel2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Vertebral augmentation''', including '''vertebroplasty''' and '''kyphoplasty''', refers to similar ] spinal procedures in which ] is injected through a small hole in the skin into a fractured ] in order to relieve ] caused by a vertebral ]. After decades of ] into the efficacy and safety of vertebral augmentation, there is still a lack of consensus regarding certain aspects of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. | |||

| == Procedure == | == Procedure == | ||

| ] and ] are the two most common procedures for spinal augmentation. These ] are ]s of the suffix '']'' meaning "molding or shaping surgically" (from ] '']'' "molded, formed") and the prefixes '']'' "vertebra" (from ] '']'' "joint, joint of the spine") and ''kypho-'' "humped; stooping forward" (from Ancient Greek '']'' "crooked").<ref>''Oxford English Dictionary'' 2009.</ref> | |||

| === Vertebroplasty === | |||

| The main goal of vertebroplasty is to reduce pain caused by the fracture by stabilizing the bone. Vertebroplasty is typically performed by a spine surgeon or interventional radiologist. It is a minimally invasive procedure and patients usually go home the same day as the procedure. Patients are given local anesthesia and light sedation for the procedure, though it can be performed using only local anesthetic for patients with severe lung disease who cannot tolerate sedatives well. | |||

| Vertebroplasty is typically performed by a spine surgeon or ]. It is a minimally invasive procedure and patients usually go home the same or next day as the procedure. Patients are given local anesthesia and light sedation for the procedure, though it can be performed using only local anesthetic for patients with medical problems who cannot tolerate sedatives well. | |||

| During the procedure, bone cement is injected with a biopsy needle into the collapsed or fractured vertebra. The needle is placed with ] guidance. The cement (most commonly ] (PMMA), although more modern cements are used as well) quickly hardens and forms a support structure within the vertebra that provide stabilization and strength. The needle makes a small puncture in the patient's skin that is easily covered with a small bandage after the procedure.<ref name="epainbook">Nicole Berardoni M.D, Paul Lynch M.D, and Tory McJunkin M.D. "Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty" 2008. Accessed 7 Aug 2009. http://www.arizonapain.com/Vertebroplasty-W.html</ref> | |||

| === Kyphoplasty === | |||

| During the procedure, acrylic cement is injected with a biopsy needle into the collapsed or fractured vertebra. The needle is placed with x-ray guidance. The acrylic cement quickly dries and forms a support structure within the vertebra that provide stabilization and strength. The needle makes a small puncture in the patient's skin that is easily covered with a small bandage after the procedure.<ref name="epainbook">Nicole Berardoni M.D, Paul Lynch M.D, and Tory McJunkin M.D. "Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty" 2008. Accessed 7 Aug 2009. http://www.arizonapain.com/Vertebroplasty-W.html</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Kyphoplasty is a variation of a vertebroplasty which attempts to restore the height and angle of ] of a fractured ] (of certain types), followed by its stabilization using injected bone cement. The procedure typically includes the use of a small balloon that is inflated in the vertebral body to create a void within the cancellous bone prior to cement delivery. Once the void is created, the procedure continues in a similar manner as a vertebroplasty, but the bone cement is typically delivered directly into the newly created void.<ref>{{Citation | last1 =Wardlaw | first1 =Douglas | last2 =Van Meirhaeghe | first2 =Jan | title =Balloon kyphoplasty in patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures | journal = ] | volume =9 | issue =4 | pages =423–436 | date =2012 | language =en |pmid=22905846 | doi=10.1586/erd.12.27| s2cid =6448288 }}</ref> | |||

| In a 2011 review Medicare contractor NAS determined that there is no difference between vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, stating, "No clear evidence demonstrates that one procedure is different from another in terms of short- or long-term efficacy, complications, mortality or any other parameter useful for differentiating coverage."<ref name="Noridian"/> | |||

| == |

== Effectiveness == | ||

| As of 2019, the effectiveness of vertebroplasty is not supported.<ref name="Cochrane2018">{{cite journal |last1=Buchbinder |first1=R |last2=Johnston |first2=RV |last3=Rischin |first3=KJ |last4=Homik |first4=J |last5=Jones |first5=CA |last6=Golmohammadi |first6=K |last7=Kallmes |first7=DF |title=Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture. |journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |date=6 November 2018 |volume=2018 |issue=11 |pages=CD006349 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD006349.pub4 |pmid=30399208|pmc=6517304 }}</ref><ref name="ASBMR2019">{{cite journal|last1=Ebeling|first1=Peter R|last2=Akesson|first2=Kristina|last3=Bauer|first3=Douglas C|last4=Buchbinder|first4=Rachelle|last5=Eastell|first5=Richard|last6=Fink|first6=Howard A|last7=Giangregorio|first7=Lora|last8=Guanabens|first8=Nuria|last9=Kado|first9=Deborah|last10=Kallmes|first10=David|last11=Katzman|first11=Wendy|date=January 2019|title=The Efficacy and Safety of Vertebral Augmentation: A Second ASBMR Task Force Report|journal=Journal of Bone and Mineral Research|volume=34|issue=1|pages=3–21|doi=10.1002/jbmr.3653|pmid=30677181|doi-access=free|last14=Wilson|first14=H Alexander|last15=Bouxsein|first15=Mary L|author-link=Mary Bouxsein|first13=Robert|last12=Rodriguez|last13=Wermers|first12=Alexander}}</ref> A 2018 Cochrane review found no role for vertebroplasty for the treatment of acute or sub-acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Buchbinder|first1=Rachelle|last2=Johnston|first2=Renea V.|last3=Rischin|first3=Kobi J.|last4=Homik|first4=Joanne|last5=Jones|first5=C. Allyson|last6=Golmohammadi|first6=Kamran|last7=Kallmes|first7=David F.|date=6 November 2018|title=Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture|journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews|volume=2018|issue=11 |pages=CD006349|doi=10.1002/14651858.CD006349.pub4|issn=1469-493X|pmc=6517304|pmid=30399208}}</ref> The subjects in these trials had primarily non-acute fractures and prior to the release of the results they were considered the most ideal people to receive the procedure. After trial results were released vertebroplasty advocates pointed out that people with acute ]s were not investigated.<ref name="Maturitas2012">{{cite journal|last=Robinson|first=Y|author2=Olerud, C|title=Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty--a systematic review of cement augmentation techniques for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures compared to standard medical therapy.|journal=Maturitas|date=May 2012|volume=72|issue=1|pages=42–9|pmid=22425141|doi=10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.02.010}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Gangi|first=A|author2=Clark, WA|title=Have recent vertebroplasty trials changed the indications for vertebroplasty?|journal=CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology|date=August 2010|volume=33|issue=4|pages=677–80|pmid=20523998|doi=10.1007/s00270-010-9901-3|s2cid=25901532}}</ref> A number of non-blinded trials suggested effectiveness,<ref>{{Citation | last1 =Wardlaw | first1 =Douglas | last2 =Cummings | first2 =Steven | title = Efficacy and safety of balloon kyphoplasty compared with non-surgical care for vertebral compression fracture (FREE): a randomised controlled trial | journal = ] | volume =373 | pages = 1016–24 | date =2009 | issue =9668 | language =en |pmid= 19246088 | doi= 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60010-6| s2cid =12241054 }}</ref> but the lack of blinding limits what can be concluded from the results and some have been criticized because of being funded by the manufacturer.<ref name=Maturitas2012/> One analysis has attributed the difference to ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=McCullough|first=BJ|author2=Comstock, BA |author3=Deyo, RA |author4=Kreuter, W |author5= Jarvik, JG |title=Major Medical Outcomes With Spinal Augmentation vs Conservative Therapy.|journal=JAMA Internal Medicine|date=Sep 9, 2013|volume=173|issue=16|pages=1514–21|pmid=23836009|doi=10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8725 |pmc=4023124}}</ref> | |||

| Some have suggested that this procedure only be done in those with fractures less than 8 weeks old;<ref>{{cite journal|last=Clark|first=WA |author2=Diamond, TH |author3=McNeil, HP |author4=Gonski, PN |author5=Schlaphoff, GP |author6=Rouse, JC|title=Vertebroplasty for painful acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures: recent Medical Journal of Australia editorial is not relevant to the patient group that we treat with vertebroplasty.|journal=The Medical Journal of Australia|date=2010-03-15|volume=192|issue=6|pages=334–7|pmid=20230351|doi=10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03533.x |s2cid=12672714 |url=https://semanticscholar.org/paper/5ddd787a8d98ca38bb73d139b195829e28968a6a }}</ref> however, analysis of the two blinded trials appear not to support the procedure even in this acute subgroup.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Staples|first=MP|author2=Kallmes, DF |author3=Comstock, BA |author4=Jarvik, JG |author5=Osborne, RH |author6=Heagerty, PJ |author7= Buchbinder, R |title=Effectiveness of vertebroplasty using individual patient data from two randomised placebo controlled trials: meta-analysis.|journal=BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.)|date=Jul 12, 2011|volume=343|pages=d3952|pmid=21750078|pmc=3133975|doi=10.1136/bmj.d3952}}</ref> Others consider the procedure only appropriate for those with other health problems making rest possibly detrimental, those with metastatic ] as the cause of the spine fracture, or those who do not improve with conservative management.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Itshayek|first=E|author2=Miller, P |author3=Barzilay, Y |author4=Hasharoni, A |author5=Kaplan, L |author6=Fraifeld, S |author7= Cohen, JE |title=Vertebral augmentation in the treatment of vertebral compression fractures: review and new insights from recent studies.|journal=Journal of Clinical Neuroscience|date=June 2012|volume=19|issue=6|pages=786–91|pmid=22595547|doi=10.1016/j.jocn.2011.12.015|s2cid=8301676}}</ref> | |||

| Vertebroplasty was first performed in France in the mid 1980’s by Drs. Deramond and Galibert with the first US procedures being performed at the University of Maryland during the early 1990’s. <ref>Halpin R, Bendok B. “Minimally Invasive Treatments for Spinal Metastases: Vertebroplasty, Kyphoplasty and Radiofrequency Ablation. Supportive Oncology 2(4):339-355 2004]</ref> The indications for vertebroplasty are for the treatment of painful vertebral compression fractures due to osteoporosis and cancer. Vertebroplasty is typically performed for patients who have failed a course of conservative treatment who still have a significant amount of back pain. <ref name="Lane">Lane J, Johnson C et al. Minimally Invasive Options for the Treatment of Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures. 33(2):431-438 2002</ref> | |||

| Evidence does not support a benefit of kyphoplasty over vertebroplasty with respect to pain, but the procedures may differ in restoring lost vertebral height, and in safety issues like cement ] (leakage).<ref name="Maturitas2012"/> As with vertebroplasty, several unblinded studies have suggested a benefit from balloon kyphoplasty.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, etal |title=A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures |journal=N. Engl. J. Med.|volume=361 |issue=6 |pages=569–79 |date=August 2009 |pmid=19657122 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0900563 |pmc=2930487}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, etal |title=A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=361 |issue=6 |pages=557–68|date=August 2009 |pmid=19657121 |doi=10.1056/NEJMoa0900429 |hdl=10536/DRO/DU:30019842 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> {{As of|2012}}, no blinded studies have been performed, and since the procedure is a derivative of vertebroplasty, the unsuccessful results of these blinded studies have cast doubt upon the benefit of kyphoplasty generally.<ref name="Zou E515-22">{{cite journal|last=Zou|first=J|author2=Mei, X |author3=Zhu, X |author4=Shi, Q |author5= Yang, H |title=The long-term incidence of subsequent vertebral body fracture after vertebral augmentation therapy: a systemic review and meta-analysis.|journal=Pain Physician|date=Jul–Aug 2012|volume=15|issue=4|pages=E515–22|pmid=22828697}}</ref> | |||

| There are approximately 750,000 vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) due to osteoporosis that occur in the US each year with only 1/3 being diagnosed by physicians.<ref>Melton L, Thamer M, Ray N et al. Fractures attributable to osteoporosis: report from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. J Bone Miner Res 12:16-23 1997</ref><ref name="Papaioannou">Papaioannou A, Watts N et al. Diagnosis and Management of Vertebral Fractures in Elderly Adults. Am J Med 113:220-228 2002</ref> Approximately 130,000 patients with painful VCF are treated with minimally invasive surgery (vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty) annually in the US.<ref>Millenium Research Group. Global Markets for Minimally Invasive Vertebral Compression Fracture Treatments 2010. RPGL20VE09 December 2009</ref> VCFs are most common in the aged population where bone quality has deteriorated due to osteoporosis (the disease characterized by bone loss increasing the risk of fragility fractures including hip, vertebra and wrist). Prior to vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, VCFs were treated strictly with conservative medical management which included pain medications, bracing and bed rest.<ref name="Papaioannou" /> Several studies have documented a decrease in mobility, patient quality of life and life expectancy due to osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures indicating it is a significant problem for elderly patients.<ref>Gold D. The Clinical Impact of Vertebral Fractures: Quality of Life in Women with Osteoporosis. Bone 18:1855-1895 1996</ref><ref>Kado D, Browner W et al. Vertebral Fractures and Mortality in Older Women. Arch Inter Med 159:1215-1220 1999</ref><ref>Cauley, J Thompson D et al. Risk of Mortality Following Clinical Fractures. Osteoporosis International 11:556-561 2000</ref> Economic studies have shown there are over 100,000 admissions due to VCFs in the US each year costing in excess of $500 Million/year in the United States alone.<ref>Gehlbach S, Burge T, et al. Hospital care of osteoporosis-related vertebral body fractures. Osteoporosis International 14:53-60; 2003</ref><ref>Riggs B, Melton L. The Worldwide Problem of Osteoporosis: Insights Afforded by Epidemiology. Bone 17:505S-511S 1995</ref> As pain medication and bed rest can exacerbate the degree of bone loss and decrease patient mobility leading to other medical problems, the use of minimally invasive treatments like vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty have become increasingly common in the US and Europe to relieve pain and regain patient mobility.<ref name="Lane" /><ref>Garin S, Yuan H. et al. New Technologies in Spine. 26(14):1511-1515 2001</ref> | |||

| Some vertebroplasty practitioners and some health care professional organizations continue to advocate for the procedure.<ref>Moan R. . Diagnostic Imaging. 2010;32(2) 5.</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Jensen|first=ME |author2=McGraw, JK |author3=Cardella, JF |author4=Hirsch, JA|title=Position statement on percutaneous vertebral augmentation: a consensus statement developed by the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology, Society of Interventional Radiology, American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons, and American Society of Spine Radiology.|journal=Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology|date=July 2009|volume=20|issue=7 Suppl|pages=S326–31|pmid=19560019|doi=10.1016/j.jvir.2009.04.022}}</ref><ref name="clarketal">{{cite journal |last1=Clark |first1=William |last2=Bird |first2=Paul |last3=Diamond |first3=Terrance |last4=Gonski |first4=Peter |last5=Gebski |first5=Val |title=Cochrane vertebroplasty review misrepresented evidence for vertebroplasty with early intervention in severely affected patients |journal=BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine |date=9 March 2019 |volume=25 |issue=online first |pages=bmjebm–2019–111171 |doi=10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111171 |pmid=30852489 |pmc=7286037 |doi-access=free }}</ref> In 2010, the board of directors of the ] released a statement recommending strongly against use of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal compression fractures,<ref>{{citation | title=The Treatment of Symptomatic Osteoporotic Spinal Compression Fractures: Guideline and Evidence Report| author=Esses, Stephen I.| publisher=American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons| url=http://www.aaos.org/Research/guidelines/SCFguideline.pdf|date=September 2010|display-authors=etal}}</ref> while the Australian Medical Services Advisory Committee considers both vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty only to be appropriate in those who have failed to improve after a trial of conservative treatment,<ref name=MSAC2011/> with conservative treatment (analgesics primarily) being effective in two-thirds of people.<ref name=Mon2012>{{cite journal|last=Montagu|first=A|author2=Speirs, A |author3=Baldock, J |author4=Corbett, J |author5= Gosney, M |title=A review of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic and malignant vertebral compression fractures.|journal=Age and Ageing|date=July 2012|volume=41|issue=4|pages=450–5|pmid=22417981|doi=10.1093/ageing/afs024|doi-access=free}}</ref> The ] similarly states that the procedure in those with osteoporotic fractures is only recommended as an option if there is severe ongoing pain from a recent fracture even with optimal pain management.<ref>{{cite web|title=Percutaneous vertebroplasty and percutaneous balloon kyphoplasty for treating osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures|url=https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta279/resources/guidance-percutaneous-vertebroplasty-and-percutaneous-balloon-kyphoplasty-for-treating-osteoporotic-vertebral-compression-fractures-pdf|website=NICE The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence|access-date=17 March 2015|page=3|date=April 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150402152256/https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta279/resources/guidance-percutaneous-vertebroplasty-and-percutaneous-balloon-kyphoplasty-for-treating-osteoporotic-vertebral-compression-fractures-pdf|archive-date=2 April 2015|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| == Clinical Research == | |||

| ], also known by the brand Kiva, is a similar procedure which also has poor evidence to support its use.<ref name=ASBMR2019/> | |||

| A Pub Med search returns over 1400 publications for the search word vertebroplasty. These publications vary from simple case series to prospective studies on the efficacy and reported complications of vertebroplasty in patients with osteoporotic and cancer related VCFs. Significant reduction or complete pain relief has been reported in 70-90% of patients treated with vertebral compression fractures due to Osteoporosis and Cancer.<ref>Hulme PA , Krebs J, Ferguson SJ, Berlemann U. "Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty: A Systematic Review of 69 Clinical Studies." Spine 2006;31(17):1983-2001</ref><ref>McGraw JK, Lippert JA, Minkus KD, Rami PM, Davis TM, Budzik RF. "Prospective evaluation of pain relief in 100 patients undergoing percutaneous vertebroplasty: results and follow-up." Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2002;13(9 pt 1):883-886</ref><ref>Layton, KF et al. "Vertebroplasty, First 1000 Levels of a Single Center: Evaluation of the Outcomes and Complications." American Journal of Neuroradiology April 2007,28:683-89</ref><ref>Jensen M, Dion J et al. Vertebroplasty relieves osteoporosis pain. Diagnostic Imaging 19(86):71-72 1997</ref><ref>Gangi A, Kastler B. et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty guided by a combination fo CT adn fluroscopy. Am J Neuroradiology 15:83-86 1994</ref><ref>Dufresne A, Brunet E et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty of the cervicothoracic junction using an anterior route: technique and results. J Neuroradiol 25:123-128 1998</ref><ref>Cortet B, Cotton A et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty inpatients with osteolytic metastases or multiple myeloma. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 64:177-183 1997</ref><ref>Voormolen M, Lohle P et al. Prospective clinical follow-up after percutaneous vertebroplasty in patietns with painful osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. J Vasc Interv Radiol 17(*):1313-1320 2006</ref><ref>Singh A, Pilgram T et al. Osteoporotic compression fractures: outcomes after single-versus multiple-level percutaneous vertebroplasty. Radiology 238(1):211-220 2006</ref><ref>McGirt M, Parker S et al. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures: an evidenced-based review of the literature. Spine J 9(6):501-508 2009</ref><ref>Trout A, Kallmes D et al. Evaluation of vertebroplasty with a validated outcome mesuare: the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. AJNR 26(10):2652-2657 2005</ref><ref>Trout A, Gray L, Kallmes D. Vertebroplasty in the inpatient population. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 26(7):1629-1633 2005</ref><ref>DO H, Kim B et al. Prospective analysis of clinical outcomes after percutaneous vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral body fractures. AJNR 26(7):1610-1611</ref><ref>M.J. McGirt et al. The Spine Journal Jan 2009 501-508</ref> | |||

| == Adverse effects == | |||

| One (1) prospective randomized, controlled clinical trial was recently published in the Lancet, by Wardlaw et al. in 2009 (FREE Study) comparing kyphoplasty (a similar procedure to vertebroplasty) to conservative management for patients suffering from vertebral compression fractures.<ref>Wardlaw D, Cummings S. Efficacy and safety of balloon kyphoplasty compared with non-surgical care for vertebral compression fracture (FREE): a randomized controlled trial. The Lancet. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60010-6 February 2009</ref> The study found a significantly greater quality of life increase (SF-36 PCS score p<0.0001) for patients who underwent kyphoplasty when compared to those who followed a course of medical management at 1 month, 3 months and 1 year post operatively. The study enrolled 300 patients (138 in the kyphoplasty group and 128 in the control group). | |||

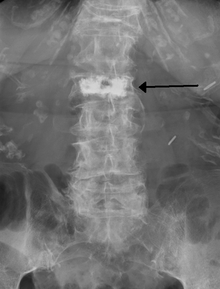

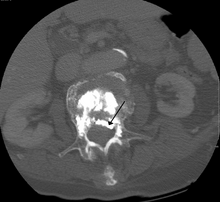

| ] | |||

| Some of the associated risks are from the leak of acrylic cement to outside of the vertebral body. Although severe complications are extremely rare, infection, bleeding, numbness, tingling, headache, and paralysis may ensue because of misplacement of the needle or cement. This particular risk is decreased by the use of X-ray or other radiological imaging to ensure proper placement of the cement.<ref name="epainbook" /> In those who have fractures due to cancer, the risk of serious adverse events appears to be greater at 2%.<ref name=Mon2012/> | |||

| The risk of new fractures following these procedures does not appear to be changed; however, evidence is limited,<ref name="Zou E515-22"/> and an increase risk as of 2012 is not ruled out.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Bliemel|first=C|author2=Oberkircher, L |author3=Buecking, B |author4=Timmesfeld, N |author5=Ruchholtz, S |author6= Krueger, A |title=Higher incidence of new vertebral fractures following percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty--fact or fiction?|journal=Acta Orthopaedica Belgica|date=April 2012|volume=78|issue=2|pages=220–9|pmid=22696994}}</ref> Pulmonary cement embolism is reported to occur in approximately 2-26% of procedures.<ref name=Wang2012>{{cite journal|last=Wang|first=LJ|author2=Yang, HL |author3=Shi, YX |author4=Jiang, WM |author5= Chen, L |title=Pulmonary cement embolism associated with percutaneous vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty: a systematic review.|journal=Orthopaedic Surgery|date=August 2012|volume=4|issue=3|pages=182–9|pmid=22927153|doi=10.1111/j.1757-7861.2012.00193.x|pmc=6583132}}</ref> It may occur with or without symptoms.<ref name=Wang2012/> Typically, if there are no symptoms, there are no long term issues.<ref name=Wang2012/> Symptoms do occur in about 1 in 2000 procedures.<ref name=MSAC2011/> Other adverse effects include spinal cord injury in 0.6 per 1000.<ref name=MSAC2011>{{cite book|title=Review of interim funded service: Vertebroplasty and New review of Kyphoplasty|date=April 2011|publisher=Medical Services Advisory Committee|isbn=9781742414560|url=http://www.msac.gov.au/internet/msac/publishing.nsf/Content/0A8B7AF67EA9D41FCA25766A000DBBEA/$File/27.1%20Assessment%20report%20for%20public%20release%2019-11-11.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| ==Prevalence== | |||

| Two prospective, randomized, controlled, blinded clinical studies were recently published in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in August of 2009. These two studies (Kallmes D et al. and Buchbinder R. et al.) compared vertebroplasty to a sham procedure (facet injections)<ref>Buchbinder, Rachelle, et al. "A Randomized Trial of Vertebroplasty for Painful Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures." The New England Journal of Medicine.August 6, 2009, Volume 361:557-568, Number 6</ref><ref>Kallmes, David F., et al. "A Randomized Trial of Vertebroplasty for Osteoporotic Spinal Fractures." The New England Journal of Medicine.August 6, 2009, Volume 361:569-579, Number 6</ref> Combined, the two studies enrolled 209 patients (103 to vertebroplasty and 106 to sham treatment) and compared pain reduction on visual analog scale (1-10 with 10 being worst imaginable pain). Both studies concluded that vertebroplasty was no more beneficial than sham procedure at decreasing pain levels in patients with vertebral compression fractures at 3 months, 6 months and 1 year post treatment. The lead authors have suggested their results call into question the value of vertebroplasty as they are the only randomized controlled clinical trials comparing a sham procedure to vertebroplasty. Since their publication, these two papers have generated significant media attention in the lay press, referencing the NEJM articles, and questioning whether vertebroplasty should be performed. Another study published in Australia found little difference in pain relief between pateints treated with vertebroplasty and those that received a sham procedure but it was not a randomized controlled, clinical trial.<ref>"Studies question impact of vertebroplasty." Aug. 6, 2009: UPI.com</ref> | |||

| In the United States in 2003 approximately 25,000 vertebroplasty procedures were paid for by Medicare.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Morrison|first=WB|author2=Parker, L |author3=Frangos, AJ |author4= Carrino, JA |title=Vertebroplasty in the United States: guidance method and provider distribution, 2001-2003.|journal=Radiology|date=April 2007|volume=243|issue=1|pages=166–70|pmid=17392252|doi=10.1148/radiol.2431060045}}</ref> As of 2011/2012 this number may be as high as 70,000-100,000 per year.<ref name=NYT2011>{{cite news|last=REDBERG|first=Rita|title=Squandering Medicare's Money|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/26/opinion/26redberg.html|access-date=18 January 2013|newspaper=New York Times|date=May 25, 2011}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| Vertebroplasty had been performed as an open procedure for many decades to secure pedicle screws and fill tumorous voids. However, the results were not always worth the risk involved with an ], which was the reason for the development of ] vertebroplasty. | |||

| The first percutaneous vertebroplasty was performed in 1984 at the University Hospital of Amiens, France to fill a vertebral void left after the removal of a benign ]. A report of this and 6 other patients was published in 1987 and it was introduced in the United States in the early 1990s. Initially, the treatment was used primarily for tumors in Europe and vertebral compression fractures in the United States, although the distinction has largely gone away since then.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Mathis |editor1-first=John M. |editor2-last=Deramond|editor2-first=Hervé |editor3-last=Belkoff |editor3-first=Stephen M. |title=Percutaneous Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty |url=https://archive.org/details/percutaneousvert00math |url-access=limited |edition=2nd |year=2006 |orig-year=First edition published 2002 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-387-29078-2 |pages=–5}}</ref> | |||

| In response to the two NEJM publications, multiple professional societies including the North American Spine Society (NASS), the Society for Interventional Radiology (SIR) and the American Journal of Neuroradiology (AJNR) have published official responses to the recent New England Journal of Medicine vertebroplasty articles. These societies have applauded the effort that was involved with performing these studies but also pointed out numerous flaws. <ref>http://www.spine.org/Pages/ConsumerHealth/NewsAndPublicRelations/NewsReleases/2009/NASSRespondsVertebroplasty.aspx</ref> <ref>http://www.ajnr.org/cgi/reprint/ajnr.A1875v1?ck=nck</ref> <ref>http://www.sirweb.org/news/newsPDF/facts/Commentary_SIR_vertebroplasty.pdf</ref> | |||

| ==Society and culture== | |||

| ===Cost=== | |||

| Significant scrutiny of the NEJM studies has lead to the following criticisms: | |||

| The cost of vertebroplasty in Europe as of 2010 was ~2,500 Euro.<ref name=Mon2012/> As of 2010 in the United States, when done as an outpatient, vertebroplasty costs around US$3300 while kyphoplasty costs around US$8100 and when done as an inpatient vertebroplasty cost ~US$11,000 and kyphoplasty US$16,000.<ref name=Mehio2011>{{cite journal|last=Mehio|first=AK|author2=Lerner, JH |author3=Engelhart, LM |author4=Kozma, CM |author5=Slaton, TL |author6=Edwards, NC |author7= Lawler, GJ |title=Comparative hospital economics and patient presentation: vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fracture.|journal=AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology|date=August 2011|volume=32|issue=7|pages=1290–4|pmid=21546460|doi=10.3174/ajnr.A2502|pmc=7966060|doi-access=free}}</ref> The cost difference is due to kyphoplasty being an in-patient procedure while vertebroplasty is outpatient, and due to the ] used in the kyphoplasty procedure.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Cloft|first1=HJ|last2=Jensen|first2=ME|title=Kyphoplasty: an assessment of a new technology.|journal=AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology|date=February 2007|volume=28|issue=2|pages=200–3|pmid=17296979|pmc=7977394 }}</ref> Medicare in 2011 spent about US$1 billion on the procedures.<ref name=NYT2011/> A 2013 study found that "the average adjusted costs for vertebroplasty patients within the first quarter and the first 2 years postsurgery were $14,585 and $44,496, respectively. The corresponding average adjusted costs for kyphoplasty patients were $15,117 and $41,339. There were no significant differences in adjusted costs in the first 9 months postsurgery, but kyphoplasty patients were associated with significantly lower adjusted treatment costs by 6.8–7.9% in the remaining periods through two years postsurgery."<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Ong|first1=KL|last2=Lau|first2=E|last3=Kemner|first3=JE|last4=Kurtz|first4=SM|title=Two-year cost comparison of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures: are initial surgical costs misleading?|journal=Osteoporosis International|date=April 2013|volume=24|issue=4|pages=1437–45|pmid=22872070|doi=10.1007/s00198-012-2100-0|s2cid=22020223}}</ref> | |||

| === Medicare response === | |||

| In response to the NEJM articles and a medical record review showing misuse of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, ] ] Noridian Administrative Services (NAS) conducted a literature review and formed a policy regarding reimbursement of the procedures. NAS states that in order to be reimbursable, a procedure must meet certain criteria, including, 1) a detailed and extensively documented medical record showing pain caused by a fracture, 2) radiographic confirmation of a fracture, 3) that other treatment plans were attempted for a reasonable amount of time, 4) that the procedure is not performed in the emergency department, and 5) that at least one year of follow-up is planned for, among others. The policy, as referenced, applies only to the region covered by Noridian and not all of Medicare's coverage area. The reimbursement policy became effective on 20 June 2011.<ref name="Noridian">{{cite web|url=http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/lcd-details.aspx?LCDId=24383&ContrNum=03102 |title=Local Coverage Determination (LCD) for Vertebroplasty, Vertebral Augmentation; Percutaneous (L24383) |author=Noridian Administrative Services, LLC |work=] |publisher=] |access-date=18 October 2011}}</ref> A 2015 comparative study of Medicare patients with vertebral compression fractures found that those who received balloon kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty therapies experienced lower mortality and overall morbidity than those who received conservative nonoperative management.<ref>{{Citation | last1 =Edidin | first1 =Avram | last2 =Ong | first2 =Kevin| title = Morbidity and Mortality After Vertebral Fractures: Comparison of Vertebral Augmentation and Nonoperative Management in the Medicare Population | journal = ] | volume =40 | issue =15 | pages = 1228–41 | date =2015 | language =en |pmid= 26020845 | doi= 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000992| s2cid =20164158 }}</ref> | |||

| === Promotion === | |||

| 1. Patient Selection Bias: 64% and 70% of the patients who met the inclusion criteria for the two NEJM studies refused to participate indicating the most painful patients requested vertebroplasty rather than risk randomization in the study. | |||

| In 2015, it was reported by ''The Atlantic'' that a person associated with a medical device company that sells equipment related to the kyphoplasty procedure had edited the Misplaced Pages article on the subject to promote claims about its efficacy.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Pinsker|first=Story by Joe|title=The Covert World of People Trying to Edit Misplaced Pages—for Pay|work=The Atlantic|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/08/wikipedia-editors-for-pay/393926/|access-date=2020-05-26|issn=1072-7825}}</ref> Assertions about the positive effects of kyphoplasty have been found to be unsupported or disproven, according to independent researchers.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Kolata|first=Gina|date=2019-01-24|title=Spinal Fractures Can Be Terribly Painful. A Common Treatment Isn't Helping.|language=en-US|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/24/health/spinal-fracture-treatment.html|access-date=2020-05-26|issn=0362-4331}}</ref> | |||

| 2. Both studies enrolled patients with fractures up to 1 year old with pain scores as low as 3 out of 10 on visual analog scale. These patients are not representative of the typical patient who benefits from vertebroplasty, whose pain scores are routinely higher (7-9 out of 10) and are significantly less mobile. | |||

| 3. Crossover rates: 1 or 3 months after initial treatment, patients in the Kallmes study from either arm were allowed to crossover (allowed to switch treatments). Crossover rates in patients who received the sham procedure were significantly higher (43%) compared to those that received vertebroplasty (12%). | |||

| 4. The Kallmes study actually reported a trend towards higher clinically meaningful pain improvement in the vertebroplasty group but did not have enough patients enrolled to demonstrate statistical significance (only 68 of 113 patients received vertebroplasty). | |||

| 5. The control groups (sham procedure) for both studies received facet blocks. Facet blocks have been reported to provide pain relief for up to 12 weeks post injection, especially in patients with older VCFs. This calls into question whether the control groups actually represented non-treatment. | |||

| The need for further studies is important to continue to understand which patients will benefit from vertebroplasty and which succeed with conservative management. The prospective randomized studies Vertos and Vertos II should offer more information on appropriate patient selection. | |||

| == Risks == | |||

| Some of the associated risks that can be produced are from the leakage of acrylic cement outside of the vertebral body. Although severe complications are extremely rare, it is important to know that infection, bleeding, numbness, tingling, headache, rib fractures, pneumothorax and paralysis may ensue due to misplacement of the needle or cement. These particular risks are decreased by the use of x-ray or other radiological imaging to ensure proper placement of the needles and cement.<ref name="epainbook" /> When the cement has leaked into blood vessels, heart and lung damage and in some extremely rare cases, deaths have occurred.<ref>Grady, Denise. "Studies Question Using Cement for Spine Fractures." New York Times. 8/6/2009, p18, 0p</ref> | |||

| == Kyphoplasty/Percutaneous Vertebral Augmentation == | |||

| A related procedure known as ''']''' or more recently referred to as ''percutaneous vertebral augmentation'' involves the creation of a cavity in a collapsed vertebra, followed by injection of bone cement to stabilize the fracture. Reduction of the fracture including height restoration can occur in some acute fractures. The benefit of percutaneous vertebral augmentation is it creates a space for cement placement and often utilizes a much thicker bone cement providing the physician more control during cement delivery. This decreases the risk of cement leakage where it was not intended, potentially leading to fewer complications. You can read more about kyphoplasty/percutaneous vertebral augmentation on Misplaced Pages. | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]/Percutaneous Vertebral Augmentation] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| <!-- See ] for instructions. --> | |||

| {{commons category|Percutaneous vertebroplasty}} | |||

| * NYTs 2019 | |||

| {{Bone, cartilage, and joint procedures}} | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| == External links == | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

Latest revision as of 06:23, 16 May 2024

Type of spinal procedureMedical intervention

| Percutaneous vertebroplasty | |

|---|---|

Typical interventional suite setup for kyphoplasty Typical interventional suite setup for kyphoplasty | |

| ICD-9-CM | 81.65 |

| MedlinePlus | 007512 |

| [edit on Wikidata] | |

Vertebral augmentation, including vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, refers to similar percutaneous spinal procedures in which bone cement is injected through a small hole in the skin into a fractured vertebra in order to relieve back pain caused by a vertebral compression fracture. After decades of medical research into the efficacy and safety of vertebral augmentation, there is still a lack of consensus regarding certain aspects of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty.

Procedure

Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty are the two most common procedures for spinal augmentation. These medical terms are classical compounds of the suffix -plasty meaning "molding or shaping surgically" (from Ancient Greek plastós "molded, formed") and the prefixes vertebro- "vertebra" (from Latin vertebra "joint, joint of the spine") and kypho- "humped; stooping forward" (from Ancient Greek kyphos "crooked").

Vertebroplasty

Vertebroplasty is typically performed by a spine surgeon or interventional radiologist. It is a minimally invasive procedure and patients usually go home the same or next day as the procedure. Patients are given local anesthesia and light sedation for the procedure, though it can be performed using only local anesthetic for patients with medical problems who cannot tolerate sedatives well.

During the procedure, bone cement is injected with a biopsy needle into the collapsed or fractured vertebra. The needle is placed with fluoroscopic x-ray guidance. The cement (most commonly poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA), although more modern cements are used as well) quickly hardens and forms a support structure within the vertebra that provide stabilization and strength. The needle makes a small puncture in the patient's skin that is easily covered with a small bandage after the procedure.

Kyphoplasty

Kyphoplasty is a variation of a vertebroplasty which attempts to restore the height and angle of kyphosis of a fractured vertebra (of certain types), followed by its stabilization using injected bone cement. The procedure typically includes the use of a small balloon that is inflated in the vertebral body to create a void within the cancellous bone prior to cement delivery. Once the void is created, the procedure continues in a similar manner as a vertebroplasty, but the bone cement is typically delivered directly into the newly created void.

In a 2011 review Medicare contractor NAS determined that there is no difference between vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, stating, "No clear evidence demonstrates that one procedure is different from another in terms of short- or long-term efficacy, complications, mortality or any other parameter useful for differentiating coverage."

Effectiveness

As of 2019, the effectiveness of vertebroplasty is not supported. A 2018 Cochrane review found no role for vertebroplasty for the treatment of acute or sub-acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures. The subjects in these trials had primarily non-acute fractures and prior to the release of the results they were considered the most ideal people to receive the procedure. After trial results were released vertebroplasty advocates pointed out that people with acute vertebral fractures were not investigated. A number of non-blinded trials suggested effectiveness, but the lack of blinding limits what can be concluded from the results and some have been criticized because of being funded by the manufacturer. One analysis has attributed the difference to selection bias.

Some have suggested that this procedure only be done in those with fractures less than 8 weeks old; however, analysis of the two blinded trials appear not to support the procedure even in this acute subgroup. Others consider the procedure only appropriate for those with other health problems making rest possibly detrimental, those with metastatic cancer as the cause of the spine fracture, or those who do not improve with conservative management.

Evidence does not support a benefit of kyphoplasty over vertebroplasty with respect to pain, but the procedures may differ in restoring lost vertebral height, and in safety issues like cement extravasation (leakage). As with vertebroplasty, several unblinded studies have suggested a benefit from balloon kyphoplasty. As of 2012, no blinded studies have been performed, and since the procedure is a derivative of vertebroplasty, the unsuccessful results of these blinded studies have cast doubt upon the benefit of kyphoplasty generally.

Some vertebroplasty practitioners and some health care professional organizations continue to advocate for the procedure. In 2010, the board of directors of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons released a statement recommending strongly against use of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal compression fractures, while the Australian Medical Services Advisory Committee considers both vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty only to be appropriate in those who have failed to improve after a trial of conservative treatment, with conservative treatment (analgesics primarily) being effective in two-thirds of people. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence similarly states that the procedure in those with osteoporotic fractures is only recommended as an option if there is severe ongoing pain from a recent fracture even with optimal pain management.

Vertebral body stenting, also known by the brand Kiva, is a similar procedure which also has poor evidence to support its use.

Adverse effects

Some of the associated risks are from the leak of acrylic cement to outside of the vertebral body. Although severe complications are extremely rare, infection, bleeding, numbness, tingling, headache, and paralysis may ensue because of misplacement of the needle or cement. This particular risk is decreased by the use of X-ray or other radiological imaging to ensure proper placement of the cement. In those who have fractures due to cancer, the risk of serious adverse events appears to be greater at 2%.

The risk of new fractures following these procedures does not appear to be changed; however, evidence is limited, and an increase risk as of 2012 is not ruled out. Pulmonary cement embolism is reported to occur in approximately 2-26% of procedures. It may occur with or without symptoms. Typically, if there are no symptoms, there are no long term issues. Symptoms do occur in about 1 in 2000 procedures. Other adverse effects include spinal cord injury in 0.6 per 1000.

Prevalence

In the United States in 2003 approximately 25,000 vertebroplasty procedures were paid for by Medicare. As of 2011/2012 this number may be as high as 70,000-100,000 per year.

History

Vertebroplasty had been performed as an open procedure for many decades to secure pedicle screws and fill tumorous voids. However, the results were not always worth the risk involved with an open procedure, which was the reason for the development of percutaneous vertebroplasty.

The first percutaneous vertebroplasty was performed in 1984 at the University Hospital of Amiens, France to fill a vertebral void left after the removal of a benign spinal tumor. A report of this and 6 other patients was published in 1987 and it was introduced in the United States in the early 1990s. Initially, the treatment was used primarily for tumors in Europe and vertebral compression fractures in the United States, although the distinction has largely gone away since then.

Society and culture

Cost

The cost of vertebroplasty in Europe as of 2010 was ~2,500 Euro. As of 2010 in the United States, when done as an outpatient, vertebroplasty costs around US$3300 while kyphoplasty costs around US$8100 and when done as an inpatient vertebroplasty cost ~US$11,000 and kyphoplasty US$16,000. The cost difference is due to kyphoplasty being an in-patient procedure while vertebroplasty is outpatient, and due to the balloons used in the kyphoplasty procedure. Medicare in 2011 spent about US$1 billion on the procedures. A 2013 study found that "the average adjusted costs for vertebroplasty patients within the first quarter and the first 2 years postsurgery were $14,585 and $44,496, respectively. The corresponding average adjusted costs for kyphoplasty patients were $15,117 and $41,339. There were no significant differences in adjusted costs in the first 9 months postsurgery, but kyphoplasty patients were associated with significantly lower adjusted treatment costs by 6.8–7.9% in the remaining periods through two years postsurgery."

Medicare response

In response to the NEJM articles and a medical record review showing misuse of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, US Medicare contractor Noridian Administrative Services (NAS) conducted a literature review and formed a policy regarding reimbursement of the procedures. NAS states that in order to be reimbursable, a procedure must meet certain criteria, including, 1) a detailed and extensively documented medical record showing pain caused by a fracture, 2) radiographic confirmation of a fracture, 3) that other treatment plans were attempted for a reasonable amount of time, 4) that the procedure is not performed in the emergency department, and 5) that at least one year of follow-up is planned for, among others. The policy, as referenced, applies only to the region covered by Noridian and not all of Medicare's coverage area. The reimbursement policy became effective on 20 June 2011. A 2015 comparative study of Medicare patients with vertebral compression fractures found that those who received balloon kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty therapies experienced lower mortality and overall morbidity than those who received conservative nonoperative management.

Promotion

In 2015, it was reported by The Atlantic that a person associated with a medical device company that sells equipment related to the kyphoplasty procedure had edited the Misplaced Pages article on the subject to promote claims about its efficacy. Assertions about the positive effects of kyphoplasty have been found to be unsupported or disproven, according to independent researchers.

References

- Oxford English Dictionary 2009.

- ^ Nicole Berardoni M.D, Paul Lynch M.D, and Tory McJunkin M.D. "Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty" 2008. Accessed 7 Aug 2009. http://www.arizonapain.com/Vertebroplasty-W.html

- Wardlaw, Douglas; Van Meirhaeghe, Jan (2012), "Balloon kyphoplasty in patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures", Expert Review of Medical Devices, 9 (4): 423–436, doi:10.1586/erd.12.27, PMID 22905846, S2CID 6448288

- ^ Noridian Administrative Services, LLC. "Local Coverage Determination (LCD) for Vertebroplasty, Vertebral Augmentation; Percutaneous (L24383)". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Buchbinder, R; Johnston, RV; Rischin, KJ; Homik, J; Jones, CA; Golmohammadi, K; Kallmes, DF (6 November 2018). "Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (11): CD006349. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006349.pub4. PMC 6517304. PMID 30399208.

- ^ Ebeling, Peter R; Akesson, Kristina; Bauer, Douglas C; Buchbinder, Rachelle; Eastell, Richard; Fink, Howard A; Giangregorio, Lora; Guanabens, Nuria; Kado, Deborah; Kallmes, David; Katzman, Wendy; Rodriguez, Alexander; Wermers, Robert; Wilson, H Alexander; Bouxsein, Mary L (January 2019). "The Efficacy and Safety of Vertebral Augmentation: A Second ASBMR Task Force Report". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 34 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3653. PMID 30677181.

- Buchbinder, Rachelle; Johnston, Renea V.; Rischin, Kobi J.; Homik, Joanne; Jones, C. Allyson; Golmohammadi, Kamran; Kallmes, David F. (6 November 2018). "Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (11): CD006349. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006349.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6517304. PMID 30399208.

- ^ Robinson, Y; Olerud, C (May 2012). "Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty--a systematic review of cement augmentation techniques for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures compared to standard medical therapy". Maturitas. 72 (1): 42–9. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.02.010. PMID 22425141.

- Gangi, A; Clark, WA (August 2010). "Have recent vertebroplasty trials changed the indications for vertebroplasty?". CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology. 33 (4): 677–80. doi:10.1007/s00270-010-9901-3. PMID 20523998. S2CID 25901532.

- Wardlaw, Douglas; Cummings, Steven (2009), "Efficacy and safety of balloon kyphoplasty compared with non-surgical care for vertebral compression fracture (FREE): a randomised controlled trial", Lancet, 373 (9668): 1016–24, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60010-6, PMID 19246088, S2CID 12241054

- McCullough, BJ; Comstock, BA; Deyo, RA; Kreuter, W; Jarvik, JG (Sep 9, 2013). "Major Medical Outcomes With Spinal Augmentation vs Conservative Therapy". JAMA Internal Medicine. 173 (16): 1514–21. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8725. PMC 4023124. PMID 23836009.

- Clark, WA; Diamond, TH; McNeil, HP; Gonski, PN; Schlaphoff, GP; Rouse, JC (2010-03-15). "Vertebroplasty for painful acute osteoporotic vertebral fractures: recent Medical Journal of Australia editorial is not relevant to the patient group that we treat with vertebroplasty". The Medical Journal of Australia. 192 (6): 334–7. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03533.x. PMID 20230351. S2CID 12672714.

- Staples, MP; Kallmes, DF; Comstock, BA; Jarvik, JG; Osborne, RH; Heagerty, PJ; Buchbinder, R (Jul 12, 2011). "Effectiveness of vertebroplasty using individual patient data from two randomised placebo controlled trials: meta-analysis". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 343: d3952. doi:10.1136/bmj.d3952. PMC 3133975. PMID 21750078.

- Itshayek, E; Miller, P; Barzilay, Y; Hasharoni, A; Kaplan, L; Fraifeld, S; Cohen, JE (June 2012). "Vertebral augmentation in the treatment of vertebral compression fractures: review and new insights from recent studies". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 19 (6): 786–91. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2011.12.015. PMID 22595547. S2CID 8301676.

- Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Heagerty PJ, et al. (August 2009). "A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (6): 569–79. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0900563. PMC 2930487. PMID 19657122.

- Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Ebeling PR, et al. (August 2009). "A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (6): 557–68. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0900429. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30019842. PMID 19657121.

- ^ Zou, J; Mei, X; Zhu, X; Shi, Q; Yang, H (Jul–Aug 2012). "The long-term incidence of subsequent vertebral body fracture after vertebral augmentation therapy: a systemic review and meta-analysis". Pain Physician. 15 (4): E515–22. PMID 22828697.

- Moan R. continues over value of vertebroplasty. Diagnostic Imaging. 2010;32(2) 5.

- Jensen, ME; McGraw, JK; Cardella, JF; Hirsch, JA (July 2009). "Position statement on percutaneous vertebral augmentation: a consensus statement developed by the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology, Society of Interventional Radiology, American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons, and American Society of Spine Radiology". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 20 (7 Suppl): S326–31. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2009.04.022. PMID 19560019.

- Clark, William; Bird, Paul; Diamond, Terrance; Gonski, Peter; Gebski, Val (9 March 2019). "Cochrane vertebroplasty review misrepresented evidence for vertebroplasty with early intervention in severely affected patients". BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 25 (online first): bmjebm–2019–111171. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111171. PMC 7286037. PMID 30852489.

- Esses, Stephen I.; et al. (September 2010), The Treatment of Symptomatic Osteoporotic Spinal Compression Fractures: Guideline and Evidence Report (PDF), American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

- ^ Review of interim funded service: Vertebroplasty and New review of Kyphoplasty (PDF). Medical Services Advisory Committee. April 2011. ISBN 9781742414560.

- ^ Montagu, A; Speirs, A; Baldock, J; Corbett, J; Gosney, M (July 2012). "A review of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic and malignant vertebral compression fractures". Age and Ageing. 41 (4): 450–5. doi:10.1093/ageing/afs024. PMID 22417981.

- "Percutaneous vertebroplasty and percutaneous balloon kyphoplasty for treating osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures". NICE The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. April 2013. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Bliemel, C; Oberkircher, L; Buecking, B; Timmesfeld, N; Ruchholtz, S; Krueger, A (April 2012). "Higher incidence of new vertebral fractures following percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty--fact or fiction?". Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 78 (2): 220–9. PMID 22696994.

- ^ Wang, LJ; Yang, HL; Shi, YX; Jiang, WM; Chen, L (August 2012). "Pulmonary cement embolism associated with percutaneous vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty: a systematic review". Orthopaedic Surgery. 4 (3): 182–9. doi:10.1111/j.1757-7861.2012.00193.x. PMC 6583132. PMID 22927153.

- Morrison, WB; Parker, L; Frangos, AJ; Carrino, JA (April 2007). "Vertebroplasty in the United States: guidance method and provider distribution, 2001-2003". Radiology. 243 (1): 166–70. doi:10.1148/radiol.2431060045. PMID 17392252.

- ^ REDBERG, Rita (May 25, 2011). "Squandering Medicare's Money". New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Mathis, John M.; Deramond, Hervé; Belkoff, Stephen M., eds. (2006) . Percutaneous Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty (2nd ed.). Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-387-29078-2.

- Mehio, AK; Lerner, JH; Engelhart, LM; Kozma, CM; Slaton, TL; Edwards, NC; Lawler, GJ (August 2011). "Comparative hospital economics and patient presentation: vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fracture". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 32 (7): 1290–4. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2502. PMC 7966060. PMID 21546460.

- Cloft, HJ; Jensen, ME (February 2007). "Kyphoplasty: an assessment of a new technology". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 28 (2): 200–3. PMC 7977394. PMID 17296979.

- Ong, KL; Lau, E; Kemner, JE; Kurtz, SM (April 2013). "Two-year cost comparison of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures: are initial surgical costs misleading?". Osteoporosis International. 24 (4): 1437–45. doi:10.1007/s00198-012-2100-0. PMID 22872070. S2CID 22020223.

- Edidin, Avram; Ong, Kevin (2015), "Morbidity and Mortality After Vertebral Fractures: Comparison of Vertebral Augmentation and Nonoperative Management in the Medicare Population", Spine, 40 (15): 1228–41, doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000992, PMID 26020845, S2CID 20164158

- Pinsker, Story by Joe. "The Covert World of People Trying to Edit Misplaced Pages—for Pay". The Atlantic. ISSN 1072-7825. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Kolata, Gina (2019-01-24). "Spinal Fractures Can Be Terribly Painful. A Common Treatment Isn't Helping". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

External links

| Procedures involving bones and joints | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthopedic surgery | |||||||||||

| Bones |

| ||||||||||

| Cartilage | |||||||||||

| Joints |

| ||||||||||