| Revision as of 20:58, 21 May 2004 editVeryVerily (talk | contribs)11,749 editsm Reverted edits by 172 to last version by VeryVerily← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:59, 24 November 2024 edit undoOnel5969 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers935,704 editsm Disambiguating links to First five-year plan (link changed to First five-year plan (Soviet Union)) using DisamAssist. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Stalinist era of Soviet history}} | |||

| {{msg:RussianHistory}} | |||

| {{redirect|Stalinist era}} | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=March 2022|cs1-dates=y}} | |||

| {{Infobox historical era | |||

| | name = Stalinist era | |||

| | location = ] | |||

| | start = 1927 | |||

| | end = 1953 | |||

| | image = | |||

| | alt = | |||

| | caption = | |||

| | before = ] | |||

| | including = ]<br><br>] | |||

| | after = ] | |||

| | monarch = | |||

| | leaders = ] | |||

| | presidents = | |||

| | primeministers = | |||

| | key_events = ]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>]<br>] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{history of Russia}} | |||

| {{history of the Soviet Union}} | |||

| <noinclude>{{Joseph Stalin series|expanded=Leader of the Soviet Union}}</noinclude> | |||

| The '''history of the Soviet Union between 1927 and 1953''', commonly referred to as the '''Stalin Era''' or '''Stalinist Era''', covers the period in ] from the ] through victory in the ] and down to the ] of ] in 1953. Stalin sought to destroy his enemies while transforming ] with ], in particular through the ] and rapid ]. ] within the party and the state and fostered an extensive ]. ] and the ] of the ] served as Stalin's major tools in molding Soviet society. ] in achieving his goals, which included ], ]s, ], and ], led to ]: in ] ]s<ref>] (2003) ''].'' {{ISBN|0-7679-0056-1}} pp 582–583</ref> and during ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/event/Holodomor|title=Holodomor | Facts, Definition, & Death Toll|date=8 August 2023 }}</ref><ref>]</ref> | |||

| World War II, known as "the ]" by Soviet historians, devastated much of the ], with about ]. In the course of World War II, the Soviet Union's armies occupied ], where they established or supported ]. By 1949, the ] had started between the ] and the ], with the ] (created 1955) pitched against ] (created 1949) in Europe. After 1945, Stalin did not directly engage in any wars, continuing his ] rule until his death in 1953.<ref>Olga V. Natolochnaya, "Socio-economic situation in the USSR during 1945-1953 years." ''Journal of International Network Center for Fundamental and Applied Research'' 1 (2015): 15-21. </ref> | |||

| ==Stalinist development== | |||

| ==Soviet state's development== | |||

| ===Planning=== | |||

| ===Industrialization in practice=== | |||

| At the Fifteenth ] of the ] in ] ], ] attacked the left by expelling ] and his supporters from the party and then moving against the right by abandoning ]'s ] which had been championed by ] and ]. Warning delegates of an impending capitalist encirclement, he stressed that survival and development could only occur by pursuing the rapid development of ]. Stalin remarked that the ] was "fifty to a hundred years behind the advanced countries" (the ], ], ], the ], etc.), and thus must narrow "this distance in ten years". In a perhaps eerie foreboding of ], Stalin declared, "Either we do it or we shall be crushed". | |||

| {{main|Industrialization in the Soviet Union}} | |||

| The mobilization of resources by state planning expanded the country's industrial base. From 1928 to 1932, ] output, necessary for further development of the industrial infrastructure rose from 3.3 million to 6.2 million tons per year. ], a basic fuel of modern economies and Stalinist ], rose from 35.4 million to 64 million tons, and the output of ] rose from 5.7 million to 19 million tons. A number of industrial complexes such as ] and ], the Moscow and ] automobile plants, the ] and Kramatorsk heavy ] plants, and Kharkiv, ] and ] tractor plants had been built or were under construction.<ref>Martin Mccauley, ''The Soviet Union 1917–1991'' (Routledge, 2014). p. 81.</ref> | |||

| In real terms, the workers' standards of living tended to drop, rather than rise during industrialization. Stalin's laws to "tighten work discipline" made the situation worse: e.g., a 1932 change to the ] labor law code enabled firing workers who had been absent without a reason from the workplace for just one day. Being fired accordingly meant losing "the right to use ration and commodity cards" as well as the "loss of the right to use an apartment″ and even blacklisted for new employment which altogether meant a threat of starving.<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.cyberussr.com/rus/trud-uvol32-e.html | title= On Firing for Unexcused Absenteeism | publisher=Cyber USSR | access-date= 2010-08-01}}</ref> Those measures, however, were not fully enforced, as managers were hard-pressed to replace these workers. In contrast, the 1938 legislation, which introduced labor books, followed by major revisions of the labor law, was enforced. For example, being absent or even 20 minutes late were grounds for becoming fired; managers who failed to enforce these laws faced criminal prosecution. Later, the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, 26 June 1940 "On the Transfer to the Eight-Hour Working Day, the Seven-day Work Week, and on the Prohibition of Unauthorized Departure by Laborers and Office Workers from Factories and Offices"<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cyberussr.com/rus/uk-trud-e.html | title=On the Prohibition of Unauthorized Departure by Laborers and Office Workers from Factories and Offices | publisher = Cyber USSR | access-date= 2010-08-01}}</ref> replaced the 1938 revisions with obligatory criminal penalties for quitting a job (2–4 months imprisonment), for being late 20 minutes (6 months of probation and pay confiscation of 25 per cent), etc. | |||

| To oversee the radical transformation of the Soviet Union, the party, under Stalin's direction, established ''Gosplan'' (the State General Planning Commission), a state organ responsible for guiding the socialist economy toward accelerated industrialization. In April ] Gosplan released two joint drafts that began the process that would industrialize the primarily agrarian nation. This 1700 page report became the basis the first ] for National Economic Construction, or '']'', calling for the doubling of Soviet capital stock between ] and ]. | |||

| Based on these figures, the Soviet government declared that the ] had been fulfilled by 93.7% in only four years, while parts devoted to the ] parts were fulfilled by 108%. Stalin in December 1932 declared the plan success to the ] since increases in the output of coal and iron would fuel future development.<ref>, Martin Mccauley, ''Stalin and Stalinism'' (3rd ed. 2013) p. 39.</ref> | |||

| Shifting from Lenin's NEP, the first Five-Year Plan established central planning as the basis of economic decision-making and the stress on rapid heavy industrialization (''see'' ]). It began the rapid process of transforming a largely agrarian nation consisting of peasants into an industrial superpower. In effect, the initial goals were laying the foundations for future, ]. | |||

| During the ] (1933–1937), on the basis of the huge investment during the first plan, the industry expanded extremely rapidly and nearly reached the plan's targets. By 1937, coal output was 127 million tons, pig iron 14.5 million tons, and there had been very rapid development of the armaments industry.<ref>E. A. Rees, ''Decision-making in the Stalinist Command Economy, 1932–37'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 1997) 212–213.</ref> | |||

| The new economic system put forward by the first Five-Year plan entailed a complicated series of planning arrangements (''see'' ]). The first Five-Year plan focused on the mobilization of natural resources to build up the country's heavy industrial base by increasing output of ], ], and other vital resources. At a high human cost, this process was largely successful, forging a capital base for industrial development more rapidly than any country in history. However, as the economy grew more complex in the post-Stalin years, the prudence of planned economic decision-making would prove less apt at attaining growth through technological innovation and improvements in productivity, thus resulting in the stagnation associated with the later years prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union. | |||

| While making a massive leap in industrial capacity, the First Five Year Plan was extremely harsh on industrial workers; quotas were difficult to fulfill, requiring that miners put in 16- to 18-hour workdays.<ref>, Andrew B. Somers, ''History of Russia'' (Monarch Press, 1965) p. 77.</ref> Failure to fulfill quotas could result in treason charges.<ref>''Problems of Communism'' (1989) – Volume 38 p. 137</ref> Working conditions were poor, even hazardous. Due to the allocation of resources for the industry along with decreasing productivity since collectivization, a famine occurred. In the construction of the industrial complexes, inmates of ] camps were used as expendable resources. But conditions improved rapidly during the second plan. Throughout the 1930s, industrialization was combined with a rapid expansion of technical and engineering education as well as increasing emphasis on munitions.<ref>Mark Harrison and Robert W. Davies. "The Soviet military‐economic effort during the second five‐year plan (1933–1937)." ''Europe‐Asia Studies'' 49.3 (1997): 369–406.</ref> | |||

| ===Industrialization in practice=== | |||

| From 1921 until 1954, the ] operated at high intensity, seeking out anyone accused of sabotaging the system. The estimated numbers vary greatly. Perhaps, 3.7 million people were sentenced for alleged counter-revolutionary crimes, including 600,000 sentenced to death, 2.4 million sentenced to labor camps, and 700,000 sentenced to ]. Stalinist repression reached its peak during the Great Purge of 1937–1938, which removed many skilled managers and experts and considerably slowed industrial production in 1937.<ref>Vadim Birstein ''Smersh: Stalin's Secret Weapon'' (Biteback Publishing, 2013) pp. 80–81.</ref> | |||

| The mobilization of resources by state planning augmented the country's industrial base. Pig ] output, necessary for development of nonexistent industrial infrastructure rose from 3.3 million to 10 million tons per year. ], the integral product fueling modern economies and Stalinist industrialization, successfully rose from 35.4 million to 75 million tons, and output of ] rose from 5.7 million to 19 million tons. A number of industrial complexes such as ] and ], the ] and ] automobile plants, the ] and Kramatorsk heavy ] plants, and Kharkov, ] and Cheliabinsk ] plants have been built or under construction. | |||

| ==Economy== | |||

| Based largely on these figures the Five Year Industrial Production Plan had been fulfilled by 93.7 percent in only four years, while parts devoted to heavy-industry part were fulfilled by 108%. Stalin in December ] declared the plan a success to the Central Committee, since increases in the output of ] and ] would fuel future development. | |||

| {{Main|Economy of the Soviet Union}} | |||

| ===Collectivization of agriculture=== | |||

| While undoubtedly marking a tremendous leap in industrial capacity, the Five Year Plan was extremely harsh on industrial workers; quotas were extremely difficult to fulfill, requiring that miners put in 16 to 18-hour workdays. Failure to fulfill the quotas could result in treason charges. | |||

| {{Main|Collectivisation in the Soviet Union|Dekulakization|Agriculture in the Soviet Union|Holodomor}} | |||

| Working conditions were poor, even hazardous. By some estimates, 127,000 workers died during the four years (from 1928 to 1932). Due to the allocation of resources for industry along with decreasing productivity since collectivization, a famine occurred. The use of forced labor must also not be overlooked. In the construction of the industrial complexes, inmates of ]s were used as expendable resources. | |||

| ], 1931]] | |||

| Under the NEP (New Economic Policy), Lenin had to tolerate the continued existence of privately owned agriculture. He decided to wait at least 20 years before attempting to place it under state control and in the meantime concentrate on industrial development. However, after ], the timetable for collectivization was shortened to just five years. Demand for food intensified, especially in the USSR's primary grain producing regions, ]. Upon joining ]es (collective farms), peasants had to give up their private plots of land and property. Every harvest, Kolkhoz production was sold to the state for a low price set by the state itself. However, the natural progress of collectivization was slow, and the November 1929 Plenum of the ] decided to accelerate collectivization through force. In any case, Russian peasant culture formed a bulwark of traditionalism that stood in the way of the Soviet state's goals. | |||

| Given the goals of the first Five Year Plan, the state sought increased political control of agriculture in order to feed the rapidly growing urban population and to obtain a source of ] through increased cereal exports. Given its late start, the USSR needed to import a substantial number of the expensive technologies necessary for heavy industrialization. | |||

| From ] until ], during the period of state-guided, forced industrialization, it is claimed 3.7 million people were sentenced for alleged counter-revolutionary crimes, including 0.6 million sentenced to death, 2.4 million sentenced to ]s, and 0.7 million sentenced to expatriation. Some other estimates put these figures much higher. Much like with the famines, the evidence supporting these high numbers<sup>4</sup> is disputed by some historians, although this is a minority view. | |||

| By 1936, about 90% of Soviet agriculture had been collectivized. In many cases, peasants bitterly opposed this process and often slaughtered their animals rather than give them to collective farms, even though the government only wanted the grain. ]s, prosperous peasants, were forcibly resettled to ], ] and the ] (a large portion of the kulaks served at forced labor camps). However, just about anyone opposing collectivization was deemed a "kulak". The policy of liquidation of kulaks as a class—formulated by Stalin at the end of 1929—meant some executions, and even more deportation to special settlements and, sometimes, to forced labor camps.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Hudson|first=Hugh D.|chapter=Liquidation of Kulak Influence, War Panic, and the Elimination of the Kulaks as a Class, 1927–1929|date=2012|work=Peasants, Political Police, and the Early Soviet State: Surveillance and Accommodation under the New Economic Policy|pages=89–111|editor-last=Hudson|editor-first=Hugh D.|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan US|language=en|doi=10.1057/9781137010544_6|isbn=978-1-137-01054-4|title=Peasants, Political Police, and the Early Soviet State}}</ref> | |||

| ===Collectivization=== | |||

| ''Main article: ].'' | |||

| Despite the expectations, collectivization led to a catastrophic drop in farm productivity, which did not return to the levels achieved under the NEP until 1940. The upheaval associated with collectivization was particularly severe in Ukraine and the heavily Ukrainian ]. Peasants slaughtered their livestock en masse rather than give them up. In 1930 alone, 25% of the nation's cattle, sheep, and goats, and one-third of all pigs were killed. It was not until the 1980s that the Soviet livestock numbers would return to their 1928 level. Government bureaucrats, who had been given a rudimentary education on farming techniques, were dispatched to the countryside to "teach" peasants the new ways of socialist agriculture, relying largely on theoretical ideas that had little basis in reality.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldhistory2/chapter/famine-and-oppression/|title=Famine and Oppression {{!}} History of Western Civilization II|website=courses.lumenlearning.com|access-date=2019-03-28}}</ref> Even after the state inevitably won and succeeded in imposing collectivization, the peasants did everything they could in the way of sabotage. They cultivated far smaller portions of their land and worked much less. The scale of the ] has led many Ukrainian scholars to argue that there was a deliberate policy of genocide against the Ukrainian people. Other scholars argue that the massive death totals were an inevitable result of a very poorly planned operation against all peasants, who had given little support to Lenin or Stalin. | |||

| In ] ] the ] decided to implement forced collectivization. This marked the end of the ], which had allowed peasants to sell their surpluses on the open market. Grain requisitioning intensified and peasants were forced to give up their private plots of land and property, to work for ]s, and to sell their produce to the state for a low price set by the state itself. | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=Almost 99% of all cultivated land had been pulled into collective farms by the end of 1937. The ghastly price paid by the peasantry has yet to be established with precision, but probably up to 5 million people died of persecution or starvation in these years. Ukrainians and Kazakhs suffered worse than most nations.|sign=]|source=Comrades! A History of World Communism (2007) p. 145}}] | |||

| In Ukraine alone, the number of people who died in the famines is now estimated to be 3.5 million.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Himka | first1 = John-Paul | year = 2013 | title = Encumbered Memory: The Ukrainian Famine of 1932–33 | journal = Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History | volume = 14 | issue = 2| pages = 411–436 | doi=10.1353/kri.2013.0025| s2cid = 159967790 }}</ref><ref>R. W. Davies, Stephen G. Wheatcroft, ''The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia Volume 5: The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931–1933'' (2nd ed. 2010) p xiv </ref> | |||

| Given the goals of the First Five Year Plan, the state sought increased political control of agriculture, hoping to feed the rapidly growing urban areas and to export grain, a source of foreign currency needed to import technologies necessary for heavy-industrialization. | |||

| The USSR took over Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in 1940, which were lost to Germany in 1941, and then recovered in 1944. The collectivization of their farms began in 1948. Using terror, mass killings and deportations, most of the peasantry was collectivized by 1952. Agricultural production fell dramatically in all the other Soviet Republics.<ref>{{Citation | url = http://www.xxiamzius.lt/archyvas/xxiamzius/20030124/istdab_01.html | first = Kazys | last = Blaževičius | title = Antanas Sniečkus. Kas jis? | journal = XXI Amžius | number = 7 | page = 1111 | place = ] | language = lt | date = Jan 24, 2003}}.</ref> | |||

| By ] about 90% of Soviet agriculture was collectivized. In many cases peasants bitterly opposed this process and often slaughtered their animals rather than give them to collective farms. ]s, prosperous peasants, were forcibly resettled to ] (a large portion of the kulaks served at forced ]s). However, just about anyone opposing collectivization was deemed a "]." The policy of liquidation of kulaks as a class, formulated by Stalin at the end of ], meant executions, and deportation to ] camps. | |||

| ===Rapid industrialization=== | |||

| Despite the expectations, collectivization led to a catastrophic drop in farming productivity, which did not regain the NEP level until ]. The upheaval associated with collectivization worsened famine conditions during a time of drought, particularly in the ] and ] region. The number of people who died in these famines is estimated at between two and five million. The actual number of casualties is bitterly disputed to this day. In 1975, ] and ] estimated that 265,800 ] families were sent to the ] in 1930. In 1979, ] used Abramov's and Kocharli's estimate to calculate that 2.5 million peasants were exiled between 1930 and 1931, but he suspected that he underestimated the total number. | |||

| {{Main|Industrialization in the Soviet Union}} | |||

| In the period of rapid industrialization and mass collectivization preceding World War II, Soviet employment figures experienced exponential growth. 3.9 million jobs per annum were expected by 1923, but the number actually climbed to an astounding 6.4 million. By 1937, the number rose yet again, to about 7.9 million. Finally, in 1940 it reached 8.3 million. Between 1926 and 1930, the urban population increased by 30 million. Unemployment had been a problem in late Imperial Russia and even under the NEP, but it ceased being a major factor after the implementation of Stalin's massive industrialization program. The sharp mobilization of resources used in order to industrialize the heretofore agrarian society created a massive need for labor; unemployment virtually dropped to zero. Wage setting by Soviet planners also contributed to the sharp decrease in unemployment, which dropped in real terms by 50% from 1928 to 1940. With wages artificially depressed, the state could afford to employ far more workers than would be financially viable in a market economy. Several ambitious extraction projects were begun that endeavored to supply raw materials for both military hardware and consumer goods. | |||

| The Moscow and ] automobile plants produced automobiles for the public—despite few Soviet citizens being able to afford a car—and the expansion of steel production and other industrial materials made the manufacture of a greater number of cars possible. Car and truck production, for example, reached 200,000 in 1931.{{Sfn | Tucker | 1990 | p = 96}} | |||

| ===Changes in Soviet Society=== | |||

| A minimum wage of 110–115 rubles was established in 1937; private gardens were allowed for one million workers to farm in their private plots. Even so, most Soviet workers lived in crowded communal housings and dormitories and suffered from extreme poverty.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/0817939423_23.pdf|title=Forced Labor in Soviet Industry: The End of the 1930s to the Mid-1950s. An Overview|website=hoover.org|author=Andrei Sokolov|access-date=2023-03-07}}</ref> | |||

| <div style="float:right;width:181px;margin:1ex 0 1ex 1em;">]</div> | |||

| ==Society== | |||

| Stalin's industrial policies largely improved living standards for the majority of the population, although the debated mortality levels resulting from Stalinist policies taints the Soviet record. | |||

| ===Propaganda=== | |||

| {{further|Propaganda in the Soviet Union}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Most of the top communist leaders in the 1920s and 1930s had been propagandists or editors before 1917, and were keenly aware of the importance of propaganda. As soon as they gained power in 1917 they seized the monopoly of all communication media, and greatly expanded their propaganda apparatus in terms of newspapers, magazines and pamphlets. Radio became a powerful tool in the 1930s.<ref>David Brandenberger, ''Propaganda state in crisis: Soviet ideology, indoctrination, and terror under Stalin, 1927–1941'' (2012).</ref> Stalin, for example, has been an editor of ''Pravda''. Besides the national newspapers '']'' and ''],'' there were numerous regional publications as well as newspapers and magazines and all the important languages. Ironclad uniformity of opinion was the norm during the Soviet era. Typewriters and printing presses were closely controlled until the late 1980s to prevent unauthorized publications. ] illegal circulation of subversive fiction and nonfiction was brutally suppressed. The rare exceptions to 100% uniformity in the official media were indicators of high-level battles. The Soviet draft constitution of 1936 was an instance. ''Pravda'' and '']'' (the paper for manual workers) praised the draft constitution. However ''Izvestiia'' was controlled by ] and it published negative letters and reports. Bukharin won out and the party line changed and started to attack "Trotskyite" oppositionists and traitors. Bukharin's success was short-lived; he was arrested in 1937, given a show trial and executed.<ref>Ellen Wimberg, "Socialism, democratism and criticism: The Soviet press and the national discussion of the 1936 draft constitution." ''Europe‐Asia Studies'' 44#2 (1992): 313–332.</ref> | |||

| ===Education=== | |||

| Employment, for instance, rose greatly; 3.9 million per year was expected by ], but the number was actually an astounding 6.4 million. By ], the number rose yet again, to about 7.9 million, and in ] it was 8.3 million. Between 1926 and 1930, the urban population increased by 30 million. ] had been a problem during the time of the Tsar and even under the NEP, but it was not a major factor after the implementation of Stalin's industrialization program. The mobilization of resources to industrialize the agrarian society industrial created a need for labor, meaning that the ] went virtually to zero. Several ambitious projects were begun, and they supplied raw materials not only for military weapons but also for consumer goods. | |||

| {{Main|Education in the Soviet Union}} | |||

| Industrial workers needed to be educated in order to be competitive and so embarked on a program contemporaneous with industrialization to greatly increase the number of schools and the general quality of education. In 1927, 7.9 million students attended 118,558 schools. By 1933, the number rose to 9.7 million students in 166,275 schools. In addition, 900 specialist departments and 566 institutions were built and fully operational by 1933. Literacy rates increased substantially as a result, especially in the ].{{Sfn | Tucker | 1990 | p = 228}}<ref>Boris N. Mironov, “The Development of Literacy in Russia and the USSR from the Tenth to the Twentieth Centuries.” ''History of Education Quarterly'' 31#2 (1991), pp. 229–252. </ref> | |||

| ===Women=== | |||

| The ] and ] automobile plants produced automobiles that the public could utilize, although not necessarily afford, and the expansion of heavy plant and ] production made production of a greater number of cars possible. ] and ] production, for example, reached 200,000 in ]. Because the industrial workers needed to be educated, the number of ] increased. In ], 7.9 million students attended 118,558 schools. This number rose to 9.7 million students and 166,275 schools by 1933. In addition, 900 specialist departments and 566 institutions were built and functioning by 1933. | |||

| {{Main|Women_in_Russia#Soviet_era:_feminist_reforms|l1 = Women in the Soviet Union}} | |||

| The Soviet people also benefited from a type of social liberalization. Women were to be given the same education as men and, at least legally speaking, obtained the same rights as men in the workplace.{{citation needed|date=January 2022}} Although in practice these goals were not reached, the efforts to achieve them and the statement of theoretical equality led to a general improvement in the socio-economic status of women.{{citation needed|date=January 2022}} | |||

| Women were notably recruited as clerks for the expanding ]s, resulting in a "feminization" of department stores as the number of female sales staff rose from 45 percent of the total sales staff in 1935 to 62 percent of the total sales staff in 1938.{{sfn|Hessler|2020|p=211}} This was in part due to a propaganda campaign launched in 1931 which linked femininity with "culture" and asserted that the New Soviet Woman was also a working woman.{{sfn|Hessler|2020|p=211}} Furthermore, department store staff had a low status in the Soviet Union and many men did not want to work as sales staff, leading to the jobs as sales staff going to poorly educated working-class women and from women newly arrived in the cities from the countryside.{{sfn|Hessler|2020|p=211}} | |||

| The Soviet people also benefited from a degree of social liberalization. Females were given an adequate, equal education and women had equal rights in employment, precipitating improving lives for women and families. Stalinist development also contributed to advances in health care, which vastly increased the lifespan for the typical Soviet citizen and the quality of life. Stalin's policies granted the Soviet people universal access to health care and education, allowing this generation to be the first not to fear ], ], and ]. The occurrences of these diseases dropped to record-low numbers, increasing life spans by decades. | |||

| However, many rights were rolled back by the authorities during this era, such as abortion, which was legalized before Stalin came to power, was banned in 1936<ref>{{Cite web |title=When Soviet Women Won the Right to Abortion (For the Second Time) |url=https://jacobin.com/2020/03/soviet-women-abortion-ussr-history-health-care/ |access-date=2023-05-29 |website=jacobin.com |language=en-US}}</ref> after controversial debate among citizens.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2015-08-31 |title=Letters to the Editor on the Draft Abortion Law |url=https://soviethistory.msu.edu/1936-2/abolition-of-legal-abortion/abolition-of-legal-abortion-texts/abolition-of-legal-abortion/ |access-date=2023-05-29 |website=Seventeen Moments in Soviet History |language=en-US}}</ref> Women's issues were also largely ignored by the government.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mamonova |first=Tatyana |title=Women and Russia: Feminist Writings from the Soviet Union |location=Oxford |publisher=Basil Blackwell Publisher |year=1984 |isbn=0-631-13889-7}}</ref> | |||

| Soviet women under Stalin were also the first generation of women able to give birth in the safety of a hospital, with access to prenatal care. Education was also an example of an increase in standard of living after economic development. The generation born during Stalin's rule was the first near-universally literate generation. Engineers were sent abroad to learn industrial technology, and hundreds of foreign engineers were brought to Russia on contract. ] was also improved, as many new ] were built. Workers who exceeded their quotas, '']s'', received many incentives for their work. They could thus afford to buy the goods that were mass-produced by the rapidly expanding Soviet economy. | |||

| ===Health=== | |||

| ==The Great Purges== | |||

| {{Main|Healthcare_in_Russia#Semashko_system|l1 = Healthcare in the Soviet Union}} | |||

| ''Main article: ]''. | |||

| Stalinist development also contributed to advances in health care, which marked a massive improvement over the Imperial era. Stalin's policies granted the Soviet people access to ] and ]. Widespread immunization programs created the first generation free from the fear of ] and ]. The occurrences of these diseases dropped to record-low numbers and infant mortality rates were substantially reduced, resulting in the ] for both men and women to increase by over 20 years by the mid-to-late 1950s.<ref name="rand">{{Citation | editor1-first = Julie | editor1-last = Da Vanzo | editor2-first = Gwen | editor2-last = Farnsworth | url = https://www.rand.org/pubs/conf_proceedings/CF124/ | title = Russia's Demographic "Crisis" | pages =115–121 | year = 1996 | publisher = ] | isbn = 978-0-8330-2446-6}}.</ref> | |||

| ===Youth=== | |||

| As this process unfolded, Stalin consolidated near-absolute power using the 1934 assassination of ] (which many suspect Stalin of having planned) as a pretext to launch the ] against his suspected political and ideological opponents, most notably the old cadres and the rank and file of the ]. Trotsky had already been expelled from the party in 1927, exiled to ] in 1928 and then expelled from the USSR entirely in 1929. Stalin used the purges to politically and physically destroy his other formal rivals (and former allies) accusing ] and ] of being behind Kirov's assassination and planning to overthrow Stalin. Ultimately, those supposedly involved in this and other conspiracies numbered in the tens of thousands with various ] and senior party members blamed with conspiracy and sabotage which were used to explain industrial accidents, production shortfalls and other failures of Stalin's regime. Measures used against opposition and suspected opposition ranged from imprisonment in work camps (]s) to execution to assassination (of Trotsky's son ] and likely of ] - Trotsky himself was to die at the hands of one of Stalin's assassins in 1940). The period between 1936-1937 is often called the ''Great Terror'', with thousands of people (even merely suspected of opposing Stalin's regime) being killed or imprisoned. Stalin is reputed to have personally signed 40,000 death warrants of suspected political opponents. | |||

| ]" by ] (1937), depicting ]]] | |||

| The ] or Youth Communist League, was an entirely new youth organization designed by Lenin became an enthusiastic strike force that organized communism across the Soviet Union often called on to attack traditional enemies.<ref>Karel Hulicka, "The Komsomol." ''Southwestern Social Science Quarterly'' (1962): 363–373. </ref> The Komsomol played an important role as a mechanism for teaching Party values to the younger generation. The Komsomol also served as a mobile pool of labor and political activism, with the ability to relocate to areas of high-priority at short notice. In the 1920s the Kremlin assigned Komsomol major responsibilities for promoting industrialization at the factory level. In 1929 7,000 Komsomol cadets were building the tractor factory in Stalingrad, 56,000 others built factories in the Urals, and 36,000 were assigned work underground in the coal mines. The goal was to provide an energetic hard-core of Bolshevik activists to influence their coworkers the factories and mines that were at the center of communist ideology.<ref>Hannah Dalton, ''Tsarist and Communist Russia, 1855–1964 '' (2015) p 132.</ref><ref>Hilary Pilkington, ''Russia's Youth and its Culture: A Nation's Constructors and Constructed'' (1995) pp 57–60.</ref> | |||

| Komsomol adopted meritocratic, supposedly class-blind membership policies in 1935, but the result was a decline in working class youth members, and a dominance by the better educated youth. A new social hierarchy emerged as young professionals and students joined the Soviet elite, displacing proletarians. Komsomol's membership policies in the 1930s reflected the broader nature of Stalinism, combining Leninist rhetoric about class-free progress with Stalinist pragmatism focused on getting the most enthusiastic and skilled membership.<ref>Seth Bernstein, "Class Dismissed? New Elites and Old Enemies among the “Best” Socialist Youth in the Komsomol, 1934–41." ''Russian Review'' 74.1 (2015): 97–116.</ref> Under Stalin, the ] was also extended to adolescents as young as 12 years old in 1935.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Mccauley |first1=Martin |title=Stalin and Stalinism: Revised 3rd Edition |date=13 September 2013 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-86369-4 |page=49 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oQ7dAAAAQBAJ&dq=stalin+death+penalty+12+years+old&pg=PA49 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Wright |first1=Patrick |title=Iron Curtain: From Stage to Cold War |date=28 October 2009 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-162284-7 |page=342 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ps5wZUFnE7IC&dq=stalin+death+penalty+12+years+old&pg=PA342 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Boobbyer |first1=Philip |title=The Stalin Era |date=2000 |publisher=Psychology Press |isbn=978-0-415-18298-0 |page=160 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lYMsIE5KjmMC&dq=stalin+death+penalty+12+years+old+boys&pg=PA160 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| During this period, the practice of mass arrest, torture, and imprisonment or execution without trial, of anyone suspected by the secret police of opposing Stalin's regime became commonplace. By the ]'s own estimates, 681,692 people were shot during 1937-38 alone (although many historians think that this was an undercount), and millions of people were transported to ] work camps. | |||

| ===Modernity=== | |||

| Several ]s were held in ], to serve as examples for the trials that local courts were expected to carry out elsewere in the country. There were four key trials from 1936 to 1938, The Trial of the Sixteen was the first (December 1936); then the Trial of the Seventeen (January 1937); then the trial of ] generals, including Marshal Tukhachevsky (June 1937); and finally the ] (including ]) in March 1938. ''See also: ]'' | |||

| Urban women under Stalin, paralleling the modernization of western countries, were also the first generation of women able to give birth in a hospital with access to prenatal care. Education was another area in which there was improvement after economic development, also paralleling other western countries. The generation born during Stalin's rule was the first near-universally literate generation. Some engineers were sent abroad to learn industrial technology, and hundreds of foreign engineers were brought to Russia on contract. Transport links were also improved, as many new railways were built, although with forced labour, costing thousands of lives. Workers who exceeded their quotas, '']s'', received many incentives for their work, although many such workers were in fact "arranged" to succeed by receiving extreme help in their work, and then their achievements were used for propaganda.<ref>{{cite book|author=Sheila Fitzpatrick|title=Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times : Soviet Russia in the 1930s|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A3M8DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA10|year=2000|publisher=Oxford UP|pages=8–10|isbn=978-0-19-505001-1}}</ref> | |||

| ===Religion=== | |||

| In spite of the Stalin's seemingly progressive ], enacted in 1936, the party's power was in reality subordinated by the secret police, the mechanism whereby Stalin secured his ] through state terror. | |||

| {{Further|Religion in the Soviet Union|USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)}} | |||

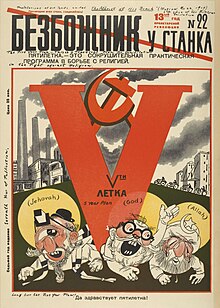

| ] in 1929, magazine of the Society of the Godless. The first five-year plan of the Soviet Union is shown crushing the gods of the ].]] | |||

| The systematic attacks on the ] began as soon as the Bolsheviks took power in 1917. In the 1930s, Stalin intensified his war on organized religion.<ref>N. S. Timasheff, ''Religion In Soviet Russia 1917–1942'' (1942) </ref> Nearly all churches and monasteries were closed and tens of thousands of clergymen were imprisoned or executed. Historian Dimitry Pospielovski has estimated that between 5,000 and 10,000 Orthodox clergy died by execution or in prison 1918–1929, plus an additional 45,000 in 1930–1939. Monks, nuns, and related personnel added an additional 40,000 dead.<ref>{{cite book|author=Daniel H. Shubin|title=A History of Russian Christianity, Vol. IV: Tsar Nicholas II to Gorbachev's Edict on the Freedom of Conscience|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WK4tAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA144|year=2006|publisher=Algora|page=144|isbn=978-0-87586-443-3}}</ref> | |||

| The state propaganda machine vigorously promoted atheism and denounced religion as being an artifact of capitalist society. In 1937, ] decried the attacks on religion in the Soviet Union. By 1940, only a small number of churches remained open. The ] were mostly directed at the Russian Orthodox Church, as it was a symbol of the czarist government. In the 1930s however, all faiths were targeted: minority Christian denominations, ], ], and ]. During ] state authorities eased pressures on ] and stopped prosecuting the church. The Orthodox Church was, therefore, able to help the Soviet Army to defend Russia.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.rbth.com/history/333593-how-russian-orthodox-church-helped/amp | title=How the Russian Orthodox Church helped the Red Army defeat the Nazis }}</ref> Religions in former USSR republics revived and once again flourished after the ] in the 1990s. As Paul Froese explains: | |||

| ==The Great Patriotic War== | |||

| :Atheists waged a 70-year war on religious belief in the Soviet Union. The Communist Party destroyed churches, mosques, and temples; it executed religious leaders; it flooded the schools and media with anti-religious propaganda; and it introduced a belief system called “scientific atheism,” complete with atheist rituals, proselytizers, and a promise of worldly salvation. But in the end, a majority of older Soviet citizens retained their religious beliefs and a crop of citizens too young to have experienced pre-Soviet times acquired religious beliefs.<ref>Paul Froese, Paul. "Forced secularization in Soviet Russia: Why an atheistic monopoly failed." ''Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion'' 43.1 (2004): 35–50. </ref> | |||

| According to 2012 official statistics, nearly 15% of ethnic Russians identify as atheist, and nearly 27% identify as unaffiliated.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://c2.kommersant.ru/ISSUES.PHOTO/OGONIOK/2012/034/ogcyhjk2.jpg |title=Archived copy |website=c2.kommersant.ru |access-date=11 January 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170421154615/http://c2.kommersant.ru/ISSUES.PHOTO/OGONIOK/2012/034/ogcyhjk2.jpg |archive-date=21 April 2017 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ===War and Stalinist development=== | |||

| ===Ethnic policies=== | |||

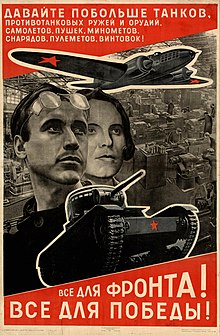

| Heavy-industrialization contributed to the Soviet Union's wartime victory over ] in the ] (known throughout the former USSR as the Great Patriotic War). The Red Army overturned the Nazi eastern expansion single-handedly, with the turning point on the Eastern Front being the ]. Although the Soviet Union was getting aid and weapons from the United States, its production of war materials was greater than that of Nazi Germany because of rapid growth of Soviet industrial production during the interwar years. The Second Five Year Plan raised the steel production to 18 million tons and the coal to 128 million tons. Before it was interrupted, the Third Five Year Plan produced 18 millions of ] and 150 million tons of ]. During the war, the allies were able to outstrip Nazi Germany in the production of war materials, in some cases ten-fold. The tank production, for example, was equal to 40,000 per year for the allies, to only 4,000 for Nazi Germany. | |||

| ] | |||

| The Soviet Union authorities systematically promoted the national consciousness of indigenous peoples and established institutional forms | |||

| characteristic of a modern nation for them.<ref></ref> In Central Asia the liberation of women was approached in the same revolutionary way as the assault on the religion. In 1927 the campaign against ] (veil) started, called "]" (assault). However, it produced a massive backlash and paranja did not disappear until the 1950s.<ref></ref><ref></ref> | |||

| In 1937, as a part of the ], repressive “national operations” were conducted. Representatives of “Western” minorities were targeted | |||

| While naïve to de-emphasize U.S. assistance in ], the Soviet Union's industrial output helped stop Nazi Germany's initial advance, and stripped them of their advantage. According to ], "One can hardly doubt that if there had been a slower buildup of industry, the attack would have been successful and world history would have evolved quite differently." For the laborers involved in industry, however, life was difficult. Workers were encouraged to fulfill and overachieve quotas through propaganda, such as the Stakhanovite movement. Between 1933 and 1945, some argue that seven million civilians died because of the demanding labor. Between 1930 and 1940, 6 million were put through the forced labor system. | |||

| because of their possible connections to countries hostile to the USSR and fear of disloyalty in case of an invasion.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==Great Purge== | |||

| Some historians, however, interpret the lack of preparedness of the Soviet Union to defend itself as a flaw in Stalin's economic planning. ] argues that there was "a command-administrative economy" but it was not "a planned one". He argues that the Soviet Union suffered from a chaotic state of the Politburo in its policies due to the ], and was completely unprepared for the ] invasion. When the Soviet Union was invaded in 1941, Stalin was indeed surprised. Economist ], in addition, argues in his ''Overambitious First Soviet Five-Year Plan'', that an array "of alternative paths were available, evolving out of the situation existing at the end of the 1920s... that could have been as good as those achieved by, say, 1936 yet with far less turbulence, waste, destruction and sacrifice." | |||

| {{Main|Great Purge}} | |||

| ] Soldiers watching a parade on May 1, 1936, at the Beginning of the Great Purge]] | |||

| As this process unfolded, Stalin consolidated near-absolute power by destroying the potential opposition. In 1936–1938, about three quarters of a million Soviets were executed, and more than a million others were sentenced to lengthy terms in harsh labour camps. Stalin's Great Terror ravaged the ranks of factory directors and engineers, and removed most of the senior officers in the Army.<ref>James Harris, ''The Great Fear: Stalin’s Terror of the 1930s'' (2017), p. 1 </ref> The pretext was the 1934 assassination of ] (which many suspect Stalin of having planned, although there is no evidence for this).<ref>Matt Lenoe, "Did Stalin Kill Kirov and Does It Matter?." ''Journal of Modern History'' 74.2 (2002): 352–380. </ref> Nearly all the old pre-1918 Bolsheviks were purged. Trotsky was expelled from the party in 1927, exiled to Kazakhstan in 1928, expelled from the USSR in 1929, and assassinated in 1940. Stalin used the purges to politically and physically destroy his other formal rivals (and former allies) accusing ] and ] of being behind Kirov's assassination and planning to overthrow Stalin. Ultimately, the people arrested were tortured and forced to confess to being spies and saboteurs, and quickly convicted and executed.<ref>James Harris, ''The Anatomy of Terror: Political Violence under Stalin'' (2013)</ref> | |||

| Several ] were held in Moscow, to serve as examples for the trials that local courts were expected to carry out elsewhere in the country. There were four key trials from 1936 to 1938, The Trial of the Sixteen was the first (December 1936); then the Trial of the Seventeen (January 1937); then the trial of ] generals, including ] (June 1937); and finally the ] (including ]) in March 1938. During these, the defendants typically confessed to sabotage, spying, counter-revolution, and conspiring with Germany and Japan to invade and partition the Soviet Union. The initial trials in 1935–1936 were carried out by the ] under ]. In turn the prosecutors were tried and executed. The secret police were renamed the ] and control given to ], known as the "Bloody Dwarf".<ref>Arkadiĭ Vaksberg and Jan Butler, ''The Prosecutor and the Prey: Vyshinsky and the 1930s' Moscow Show Trials'' (1990).</ref> | |||

| While by no means an "orderly" economy or an efficient one, the Five Year Plans did plan an offensive, but since the Soviet Union was under attack, the situation required a defensive response. The result, as Shearer points out, was that the command economy had to be relaxed so that the mobilization needed was achieved. Sapir supports this view, arguing that Stalin's policies developed a mobilized economy (which was inefficient), with tension between central and local decision-making. Market forces became more significant than central administrative constraints. This view, however, is refuted by ], who argues that Soviet Union's "heavy industrialization translated into ultimate survival." | |||

| The "Great Purge" swept the Soviet Union in 1937. It was widely known as the "Yezhovschina", the "Reign of Yezhov". The rate of arrests was staggering. In the armed forces alone, 34,000 officers were purged, including many at the higher ranks.<ref>{{cite book|author=Geoffrey Roberts|title=Stalin's General: The Life of Georgy Zhukov|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OOxRrfalHJcC&pg=PT58|year=2012|publisher=Icon Books|pages=58–59|isbn=978-1-84831-443-6}}</ref> The entire Politburo and most of the Central Committee were purged, along with foreign communists who were living in the Soviet Union, and numerous intellectuals, bureaucrats, and factory managers. The total of people imprisoned or executed during the Yezhovschina numbered about two million.<ref>{{cite book|author=Paul R. Gregory|title=Terror by Quota: State Security from Lenin to Stalin|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-DH57dXl_agC&pg=PA18|year=2009|publisher=Yale University Press|pages=16–20|isbn=978-0-300-15278-4}}</ref> By 1938, the mass purges were starting to disrupt the country's infrastructure, and Stalin began winding them down. Yezhov was gradually relieved of power. Yezhov was relieved of all powers in 1939, then tried and executed in 1940. His successor as head of the NKVD (from 1938 to 1945) was ], a Georgian friend of Stalin's. Arrests and executions continued into 1952, although nothing on the scale of the Yezhovschina ever happened again. | |||

| ===Wartime developments=== | |||

| During this period, the practice of mass arrest, torture, and imprisonment or execution without trial, of anyone suspected by the secret police of opposing Stalin's regime became commonplace. By the NKVD's own count, 681,692 people were shot during 1937–1938 alone, and hundreds of thousands of political prisoners were transported to Gulag work camps.<ref>{{cite book|author= Gregory|title=Terror by Quota: State Security from Lenin to Stalin|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-DH57dXl_agC&pg=PA16|year=2009|page=16|publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-15278-4}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The mass terror and purges were little known to the outside world, and some western intellectuals and fellow travellers continued to believe that the Soviets had created a successful alternative to a capitalist world. In 1936, the country adopted its ], which only on paper granted freedom of speech, religion, and assembly. Scholars estimate the total death toll for the Great Purge (1936–1938), including fatalities attributed to prison conditions, to be roughly 700,000-1.2 million.<ref>{{Citation |title=Introduction: the Great Purges as history |date=1985 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511572616.002 |work=Origins of the Great Purges |pages=1–9 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |doi=10.1017/cbo9780511572616.002 |isbn=978-0521259217 |access-date=2021-12-02}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Homkes|first=Brett|date=2004|title=Certainty, Probability, and Stalin's Great Purge|url=https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1032&context=mcnair|journal=McNair Scholars Journal}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ellman |first1=Michael |title=Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments |journal=Europe-Asia Studies |date=2002 |volume=54 |issue=7 |pages=1151–1172 |doi=10.1080/0966813022000017177 |jstor=826310 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/826310 |issn=0966-8136}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Shearer |first1=David R. |title=Stalin and War, 1918-1953: Patterns of Repression, Mobilization, and External Threat |date=11 September 2023 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-000-95544-6 |page=vii |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CCHMEAAAQBAJ&dq=great+purge+1.2+million&pg=PR7 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Nelson |first1=Todd H. |title=Bringing Stalin Back In: Memory Politics and the Creation of a Useable Past in Putin's Russia |date=16 October 2019 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-1-4985-9153-9 |page=7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oJGyDwAAQBAJ&dq=stalin+great+purge+1.2+million&pg=PA7 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In March 1939, the ] was held in Moscow. Most of the delegates present at the ] in 1934 were gone, and Stalin was heavily praised by Litvinov and the western democracies criticized for failing to adopt the principles of "collective security" against Nazi Germany. | |||

| The Nazi invasion caught the Soviet military unprepared. A widely-held belief is that this was caused by a large number (an estimated 40,000) of the senior officers being sent to prison in the "Great Purges" of ]-]. To secure Soviet influence over ] and buy some time, Stalin arranged the ], a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany on ], ]. A secret appendix to the pact gave Eastern ], ], ] and ] to the USSR, and Western Poland and ] to Nazi Germany. Nazi Germany invaded Poland on ]st, USSR followed on ]th. On ]th, the USSR’s invaded Finland during the ]. Although outnumbering Finnish troops by over 50:1, the Soviets were unable to capture more than a small fraction of the nation. | |||

| ===Interpreting the purges=== | |||

| On ] ], however, ] broke the pact and invaded the Soviet Union (see ]). | |||

| Two major lines of interpretation have emerged among historians. One argues that the purges reflected Stalin's ambitions, his paranoia, and his inner drive to increase his power and eliminate potential rivals. Revisionist historians explain the purges by theorizing that rival factions exploited Stalin's paranoia and used terror to enhance their own position. Peter Whitewood examines the first purge, directed at the Army, and comes up with a third interpretation that: Stalin and other top leaders, assuming that they were always surrounded by enemies, always worried about the vulnerability and loyalty of the Red Army. It was not a ploy – Stalin truly believed it. “Stalin attacked the Red Army because he seriously misperceived a serious security threat”; thus “Stalin seems to have genuinely believed that foreign‐backed enemies had infiltrated the ranks and managed to organize a conspiracy at the very heart of the Red Army.” The purge hit deeply from June 1937 and November 1938, removing 35,000; many were executed. Experience in carrying out the purge facilitated purging other key elements in the wider Soviet polity.<ref>Peter Whitewood, ''The Red Army and the Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Soviet Military'' (2015) Quoting pp 12, 276.</ref><ref>Ronald Grigor Suny, review, ''Historian'' (2018) 80#1:177-179.</ref> Historians often cite the disruption as factors in its disastrous military performance during the German invasion.<ref>Roger R. Reese, "Stalin Attacks the Red Army." ''Military History Quarterly'' 27.1 (2014): 38–45.</ref> | |||

| ==Foreign relations, 1927–1939== | |||

| Using his contacts within the German ] party, ] spy ] was able to discover the exact date and time of the planned German invasion of the Soviet Union. This information was passed along to Stalin, but went ignored, despite warning from not only Sorge, but ] as well. | |||

| {{Main|Foreign relations of the Soviet Union|International relations (1919–1939)}} | |||

| The Soviet government had forfeited foreign-owned private companies during the creation of the RSFSR and the USSR. Foreign investors did not receive any monetary or material compensation. The USSR also refused to pay tsarist-era debts to foreign debtors. The young Soviet polity was a pariah because of its openly stated goal of supporting the overthrow of capitalistic governments. It sponsored workers' revolts to overthrow numerous capitalistic European states, but they all failed. Lenin reversed radical experiments and restored a sort of capitalism with the NEC. The Comintern was ordered to stop organizing revolts. Starting in 1921 Lenin sought trade, loans and recognition. One by one, foreign states reopened trade lines and recognized the Soviet government. The United States was the last major polity to recognise the USSR in 1933. In 1934, the French government proposed an alliance and led 30 governments to invite the USSR to join the League of Nations. The USSR had achieved legitimacy but was expelled in December 1939 for aggression against Finland.<ref>George F. Kennan, ''Russia and the West under Lenin and Stalin'' (1961). pp 172–259.</ref><ref>Barbara Jelavich, ''St. Petersburg and Moscow: tsarist and Soviet foreign policy, 1814–1974'' (1974). pp 336–354.</ref> | |||

| In 1928, Stalin pushed a leftist policy based on his belief in an imminent great crisis for capitalism. Various European communist parties were ordered not to form coalitions and instead to denounce moderate socialists as ]. Activists were sent into labour unions to take control away from socialists–a move the ] never forgave. By 1930, the Stalinists started suggesting the value of alliance with other parties, and by 1934 the idea to form a ] had emerged. Comintern agent ] was especially effective in organizing intellectuals, antiwar and pacifist elements to join the anti-Nazi coalition.<ref>Sean McMeekin, ''The Red Millionaire: A Political Biography of Willi Münzenberg, Moscow’s Secret Propaganda Tsar in the West'' (2003) pp 115–116, 194.</ref> Communists would form coalitions with any party to fight fascism. For Stalinists, the Popular Front was simply an expedient, but to rightists, it represented the desirable form of transition to socialism.<ref>Jeff Frieden, "The internal politics of European Communism in the Stalin Era: 1934–1949". ''Studies in Comparative Communism'' 14.1 (1981): 45–69 {{dead link|date=July 2022|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> | |||

| It is said that Stalin at first refused to believe ] had broken the treaty. However, new evidence shows Stalin held meetings with a variety of senior Soviet government and military figures, including ] (People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs), ] (People's Commissar for Defense), ] (Chief of Staff of the Red Army), ] (Commander of both North Caucasus and Baltic Military Districts), and ] (Deputy People's Commissar for Defense). All in all, on the very first day of the attack, Stalin held meetings with over 15 individual members of the Soviet government and military apparatus.<sup>5</sup> | |||

| Franco-Soviet relations were initially hostile because the USSR officially opposed the World War I peace settlement of 1919 that France emphatically championed. While the Soviet Union was interested in conquering territories in Eastern Europe, France was determined to protect the fledgling states there. However, ]'s foreign policy centered on a massive seizure of Central European, Eastern European, and Russian lands for Germany's own ends, and when Hitler pulled out of the ] in Geneva in 1933, the threat hit home. Soviet Foreign Minister ] reversed Soviet policy regarding the Paris Peace Settlement, leading to a Franco-Soviet rapprochement. In May 1935, the USSR concluded pacts of mutual assistance with France and Czechoslovakia. Stalin-ordered the ] to form a ] with leftist and centrist parties against the forces of ]. The pact was undermined, however, by strong ideological hostility to the Soviet Union and the Comintern's new front in France, Poland's refusal to permit the ] on its soil, France's defensive military strategy, and a continuing Soviet interest in patching up relations with Nazi Germany. | |||

| Nazi German troops reached the outskirts of ] in December 1941, but were diverted to shore up southern flanks. At the ] in 1942-43, after losing an estimated 1 million men in the bloodiest fighting in history, the Red Army was able to regain the initiative of the war. Due to the unwillingness of the Japanese to open a second front in ], the Soviets were able to call dozens of Red Army division back from eastern Russia. These units were instrumental in turning the tide, because most of their officer corps had escaped Stalin’s purges. The Soviet forces were soon able to regain their lost territory and push their over-stretched enemy back to Nazi Germany itself. | |||

| The Soviet Union supplied military aid to the ] of the ] during the ], including munitions and soldiers, and helped far-left activists come to Spain as volunteers. The Spanish government let the USSR have the government treasury. Soviet units systematically liquidated anarchist supporters of the Spanish government. Moscow's support of the government gave the Republicans a Communist taint in the eyes of anti-Bolsheviks in Britain and France, weakening the calls for Anglo-French intervention in the war.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=McCannon | |||

| From the end of 1944 to 1949 large sections of eastern Germany came under the Soviet Union's occupation and on May 2nd 1945, the capital city ] was taken, while over fifteen million Germans were removed from eastern Germany and pushed into central Germany (later called GDR ]) and western Germany (later called FRG ]). Russians, Ukrainians, Poles, Czech etc. were then moved onto German land. | |||

| |first=John|date=1995|title=Soviet Intervention in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–39: A Reexamination|journal=Russian History|volume=22|issue=2|pages=154–180|issn=0094-288X|jstor=24657802|doi=10.1163/187633195X00070}}</ref> | |||

| Nazi Germany promulgated an ] with Imperialist Japan and Fascist Italy, along with various Central and Eastern European states (such as ]), ostensibly to suppress Communist activity but more realistically to forge an alliance against the USSR.<ref>Lorna L. Waddington, "The Anti-Komintern and Nazi anti-Bolshevik propaganda in the 1930s". ''Journal of Contemporary History'' 42.4 (2007): 573–594.</ref> | |||

| The Soviets bore the brunt of World War II because the West could not open up a second ground front in Europe until the invasion of ] and ]. Approximately 21 million Soviets, among them 7 million civilians, were killed in "Operation Barbarossa," the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany. Civilians were rounded up and burned or shot in many cities conquered by the Nazis. Many feel that since the Slavs were considered "sub-human," this was ethnically targeted mass murder. However, the retreating Soviet army was ordered to pursue a ']' policy whereby retreating Soviet troops were ordered to destroy Russian and occupied Polish civilian infrastructure and food supplies so that the Nazi German troops could not use them. | |||

| == World War II == | |||

| ] resulted in enormous destruction of infrastructure and populations throughout Eurasia, from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans, with almost no country left unscathed. The ] was especially scathed due to the mass destruction of the industrial base that it had built up in the 1930s. The only major industrial power in the world to emerge intact, and even greatly strengthened from an economic perspective, was the ]. | |||

| {{Main|Soviet Union in World War II}} | |||

| ] at the end of the ]. At the center Major General ] and Brigadier ]]] | |||

| Stalin arranged the ], a non-aggression pact with ] on 23 August along with the ] to open economic relations. A secret appendix to the pact gave Eastern Poland, Latvia, Estonia, ] and Finland to the USSR, and Western Poland and ] to Nazi Germany. This reflected the Soviet desire of territorial gains. | |||

| Following the pact with Hitler, Stalin in 1939–1940 annexed half of Poland, the three Baltic States, and Northern Bukovina and Bessarabia in Romania. They no longer were buffers separating the USSR from German areas, argues Louis Fischer. Rather they facilitated Hitler's rapid advance to the gates of Moscow.<ref>Louis Fischer, ''Russia's Road from Peace to War: Soviet Foreign Relations, 1917–1941'' (1969).</ref> | |||

| Propaganda was also considered an important foreign relations tool. International exhibitions, the distribution of media such as films, e.g.: '']'', as well as inviting prominent foreign individuals to tour the Soviet Union, were used as a method of gaining international influence and encouraging fellow travelers and pacifists to build popular fronts.<ref>Frederick C. Barghoorn, ''Soviet foreign propaganda'' (1964) pp 25–27, 115, 255.</ref> | |||

| ===Start of World War II=== | |||

| {{Main|Events preceding World War II in Europe|Soviet invasion of Poland|Soviet occupation of the Baltic states (1940)|Winter War}} | |||

| Germany ] on 1 September; the ] on 17 September. The Soviets quelled opposition by executing and arresting thousands. They relocated suspect ethnic groups to Siberia in four waves, 1939–1941. Estimates varying from the figure over 1.5 million.<ref>Pavel Polian, ''Against Their Will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR'' (2004) p 119 </ref> | |||

| After Poland was divided up with Germany, Stalin made territorial demands to Finland, claiming security needs regarding the protection of Leningrad. After the Finns refused the demands, the Soviets invaded Finland on 30 November 1939, launching the ], with the goal of annexing Finland into the Soviet Union.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Manninen|first1=Ohto|author-link1=Ohto Manninen|title=Miten Suomi valloitetaan: Puna-armeijan operaatiosuunnitelmat 1939–1944|year=2008|publisher=Edita|isbn=978-951-37-5278-1|ref=Manninen2008|language=fi|trans-title=How to Conquer Finland: Operational Plans of the Red Army 1939–1944}}</ref> Despite outnumbering Finnish troops by over 2.5:1, the war proved embarrassingly difficult for the Red Army, which was ill-equipped for the winter weather and lacking competent commanders since the ]. The Finns resisted fiercely, and received some support and considerable sympathy from the Allies. On 29 January 1940, the Soviets put an end to their puppet ] that they had intended on inserting into Helsinki, and informed the Finnish government that the Soviet Union was willing to negotiate peace.<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Trotter|first1=William R.|author-link1=William R. Trotter|title=The Winter War: The Russo–Finnish War of 1939–40|edition=5th|year=2002|orig-year=1991|publisher=Aurum Press|isbn=1-85410-881-6}}</ref> The ] was signed on 12 March 1940, with the war ending the following day. By the terms of the treaty, Finland relinquished the ] and some smaller territories.<ref>Derek W. Spring, "The Soviet decision for war against Finland, 30 November 1939." ''Soviet Studies'' 38.2 (1986): 207–226. </ref> London, Washington—and especially Berlin—calculated that the poor showing of the Soviet army indicated it was incompetent to defend the USSR against a German invasion.<ref>Roger R. Reese, "Lessons of the Winter War: a study in the military effectiveness of the Red Army, 1939–1940." ''Journal of Military History'' 72.3 (2008): 825–852.</ref><ref>Martin Kahn, "'Russia Will Assuredly Be Defeated': Anglo-American Government Assessments of Soviet War Potential before Operation Barbarossa,” ''Journal of Slavic Military Studies'' 25#2 (2012), 220–240,</ref> | |||

| In 1940, the USSR ] and illegally annexed Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. On 14 June 1941, the USSR performed first mass deportations from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. | |||

| On 26 June 1940 the Soviet government issued an ] to the Romanian minister in Moscow, demanding the ] immediately cede ] and ]. Italy and Germany, which needed a stable Romania and access to its oil fields urged ] to do so. Under duress, with no prospect of aid from France or Britain, Carol complied. On 28 June, Soviet troops crossed the Dniester and ] ], ], and the ].<ref>{{Citation | first = Charles | last = King | title = The Moldovans | publisher = Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University | year = 2000 | isbn = 978-0-8179-9792-2 | url-access = registration | url = https://archive.org/details/moldovansromania00king_0 }}.</ref> | |||

| ===Great Patriotic War=== | |||

| {{Main|Great Patriotic War (term)|Eastern Front (World War II)|Operation Barbarossa|Diplomatic history of World War II}} | |||

| ] | |||

| On 22 June 1941, ] abruptly broke the non-aggression pact and ]. Stalin had made no preparations. Soviet intelligence was fooled by German disinformation and the invasion caught the Soviet military unprepared. In the larger sense, Stalin expected invasion but not so soon.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Murphy, David E (2005), What Stalin Knew: the enigma of Barbarossa.}}</ref> The Army had been decimated by the Purges; time was needed for a recovery of competence. As such, mobilization did not occur and the Soviet Army was tactically unprepared as of the invasion. The initial weeks of the war were a disaster, with hundreds of thousands of men being killed, wounded, or captured. Whole divisions disintegrated against the German onslaught. Soviet POWs in German prison camps were treated poorly, leading to only 1/10 of Red Army POWs surviving German camps. In contrast, 1/3 of German POWs survived the Soviet prison camps.<ref>*Citino, R. Death of the Wehrmacht: The German Campaigns of 1942. University Press of Kansas, 2007. | |||

| * Glantz, D. with House, J. When Titan's Clashed. University Press of Kansas, 2015. | |||

| * Glantz, D. with House, J. Armageddon in Stalingrad. The Stalingrad Trilogy, Volume 2. University Press of Kansas, 2009. | |||

| * Glantz, D. with House, J. To the Gates of Stalingrad. The Stalingrad Trilogy, Volume 1. University Press of Kansas, 2009. | |||

| * Kavalerchik, B. The Price of Victory: The Red Army’s Casualties in the Great Patriotic War. Pen & Sword Military, 2017. | |||

| * Liedtke, G. Enduring the Whirlwind: The German Army and the Russo-German War 1941–1943. Helion & Company LTD, 2016.</ref> | |||

| German troops reached the outskirts of Moscow in December 1941, but failed to capture it, due to staunch Soviet defence and counterattacks. At the ] in 1942–1943, the Red Army inflicted a crushing defeat on the German army. Due to the unwillingness of the Japanese to open a second front in ], the Soviets were able to call dozens of Red Army divisions back from eastern Russia. These units were instrumental in turning the tide, because most of their officer corps had escaped Stalin's purges. The Soviet forces soon launched massive counterattacks along the entire German line. By 1944, the Germans had been pushed out of the Soviet Union onto the banks of the ] river, just east of Prussia. With Soviet Marshal ] attacking from Prussia, and Marshal ] slicing Germany in half from the south, the fate of ] was sealed. On 2 May 1945 the last German troops surrendered to the Soviet troops in Berlin. | |||

| ===Wartime developments=== | |||

| {{further|Home front during World War II#Soviet Union}} | |||

| From the end of 1944 to 1949, large sections of eastern Germany came under the Soviet Union's occupation and on 2 May 1945, ], while over fifteen million Germans were removed from eastern Germany (renamed the ] of the ]) and pushed into ] (later called the ]) and ] (later called the ]). | |||

| An atmosphere of ] took over the Soviet Union during the war, and persecution of the Orthodox Church was halted. The Church was now permitted to operate with a fair degree of freedom, so long as it did not get involved in politics. In 1944, a ] was written, replacing ], which had been used as the national anthem since 1918. These changes were made because it was thought that the people would respond better to a fight for their country than for a political ideology. | |||

| As mentioned, the Soviets bore the heaviest casualties of ]. These war casualties can explain much of Russia's behavior after the war. The Soviet Union continued to occupy and dominate Eastern Europe as a "buffer zone" to protect Russia from another invasion from the West. Russia had been invaded three times past 150 years before the ] during the Napoleonic Wars, ], and ], suffering tens of millions of casualties. | |||

| The Soviets bore the brunt of World War II because the West did not open up a second ground front in Europe until the ] and the ]. Approximately 26.6 million Soviets, among them 18 million civilians, were killed in the war. Civilians were rounded up and burned or shot in many cities conquered by the Nazis.{{Citation needed|date=April 2011}} The retreating Soviet army was ordered to pursue a ']' policy whereby retreating Soviet troops were ordered to destroy civilian infrastructure and food supplies so that the Nazi German troops could not use them. | |||

| The Soviets were determined to punish those peoples it saw as collaborating with Germany during the war. Millions of Poles, Latvians, Georgians, Ukrainians and other ethnic minorities were deported to Gulags in Siberia. It was also during the Soviet retaking of Poland during which thousands of Polish Army officers, including reservists, were executed in what came to be known as the ]. | |||

| Stalin's original declaration in March 1946 that there were 7 million war dead was revised in 1956 by ] with a round number of 20 million. In the late 1980s, demographers in the State Statistics Committee (]) took another look using demographic methods and came up with an estimate of 26–27 million. A variety of other estimates have been made.<ref>{{Citation | first1 = Michael | last1 = Ellman | first2 = S | last2 = Maksudov | title = Soviet Deaths in the Great Patriotic War: A Note | journal = ] | volume = 46 | number = 4 | year = 1994 | pages = 671–680 | doi=10.1080/09668139408412190 | pmid=12288331}}.</ref> In most detailed estimates roughly two-thirds of the estimated deaths were civilian losses. However, the breakdown of war losses by nationality is less well known. One study, relying on indirect evidence from the 1959 population census, found that while in terms of the aggregate human losses the major Slavic groups suffered most, the largest losses relative to population size were incurred by minority nationalities mainly from European Russia, among groups from which men were mustered to the front in "nationality battalions" and appear to have suffered disproportionately.<ref>{{Citation | first1 = Barbara A | last1 = Anderson | first2 = Brian D | last2 = Silver | contribution = Demographic Consequences of World War II on the Non-Russian Nationalities of the USSR | editor-first = Susan J | editor-last = Linz | title = The Impact of World War II on the Soviet Union | place = Totowa, ] | publisher = Rowman & Allanheld | year = 1985}}.</ref> | |||

| Stalin also had all Russian soldiers taken captive by Germany sent to isolated work camps in Siberia. This was done to minimize any perceived counter-revolutionary ideas they had been exposed to while not under direct Soviet control. | |||

| After the war, the Soviet Union ], in line with ]. | |||

| ==The Cold War== | |||

| Stalin was determined to punish those peoples he saw as ] during the war and to deal with the problem of ], which would tend to pull the Soviet Union apart. Millions of Poles, Latvians, Georgians, Ukrainians and other ethnic minorities were deported to Gulags in Siberia. (Previously, following ], thousands of Polish Army officers, including reservists, had been executed in the spring of 1940, in what came to be known as the ].) In addition, in 1941, 1943 and 1944 several whole nationalities had been deported to Siberia, Kazakhstan, and Central Asia, including, among others, the ], ], ], ], ], and ]. Though these groups were later politically "rehabilitated", some were never given back their former autonomous regions.<ref>{{Citation | first = Robert | last = Conquest | title = The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities | place = London | publisher = MacMillan | year = 1970 | isbn = 978-0-333-10575-7}}.</ref><ref name = "Wimbush">{{Citation | first1 = S Enders | last1 = Wimbush | first2 = Ronald | last2 = Wixman | title = The Meskhetian Turks: A New Voice in Central Asia | journal = Canadian Slavonic Papers | volume = 27 | number = 2–3 |date= 1975 | pages = 320–340| doi = 10.1080/00085006.1975.11091412 }}.</ref><ref name = "Nekich">{{Citation | author = Alexander Nekrich | author-link = Alexander Nekrich | title = The Punished Peoples: The Deportation and Fate of Soviet Minorities at the End of the Second World War | place = New York | publisher = WW Norton | year = 1978 | isbn = 978-0-393-00068-9}}.</ref><ref name = "transfer">], Misplaced Pages.</ref> | |||

| ===The tenor of Soviet-US relations=== | |||

| ] | |||

| At the same time, in a famous ] toast in May 1945, Stalin extolled the role of the ] in the defeat of the fascists: "I would like to raise a toast to the health of our ] and, before all, the Russian people. I drink, before all, to the health of the Russian people, because in this war they earned general recognition as the leading force of the Soviet Union among all the nationalities of our country... And this trust of the Russian people in the Soviet Government was the decisive strength, which secured the historic victory over the enemy of humanity – over fascism..."<ref>{{Citation | type = complete text of the toast | title = Russification| title-link = Russification}}.</ref> | |||

| World War II resulted in enormous destruction of infrastructure and populations throughout ], from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans, with almost no country left unscathed. The Soviet Union was especially devastated due to the mass destruction of the industrial base that it had built up in the 1930s. The USSR also experienced a major ] in 1946–1948 due to war devastation that cost an estimated 1 to 1.5 million lives as well as secondary population losses due to reduced fertility.{{Efn | Although the 1946 drought was severe, government mismanagement of its grain reserves largely accounted for the population losses.<ref>{{Citation | first = Michael | last = Ellman | title = The 1947 Soviet Famine and the Entitlement Approach to Famines | journal = Cambridge Journal of Economics | volume = 24 | issue = 5 | year = 2000 | pages = 603–630 | doi=10.1093/cje/24.5.603}}.</ref>}} However, the Soviet Union recovered its production capabilities and overcame pre-war capabilities, becoming the country with the most powerful land army in history by the end of the war, and having the most powerful military production capabilities. | |||

| The wartime alliance between the ] and the Soviet Union was an aberration from the normal tenor of Russian-US relations. Strategic rivalry between the huge, sprawling nations goes back to the ] when, after a century of friendship, Americans and Russians became rivals over the development of ]. Tsarist Russia, unable to compete industrially, sought to close off and colonize parts of East Asia, while Americans demanded open competition for markets. | |||

| ====War and Stalinist industrial-military development==== | |||