| Revision as of 14:00, 19 June 2010 edit81.106.115.153 (talk) Reverted edit. Please read the discussion page.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:35, 23 October 2024 edit undoMonkbot (talk | contribs)Bots3,695,952 editsm Task 20: replace {lang-??} templates with {langx|??} ‹See Tfd› (Replaced 16);Tag: AWB | ||

| (491 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Short formulaic prayer in Christianity}} | |||

| {{Expert-subject|Eastern Orthodoxy|article|date=November 2008}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Lord's Prayer|prayers of Jesus}} | |||

| The '''Jesus Prayer''',{{efn|{{langx|el|προσευχὴ τοῦ Ἰησοῦ|translit=prosefchí tou iisoú|lit=prayer to Jesus}}; {{langx|syr|ܨܠܘܬܐ ܕܝܫܘܥ|translit=slotho d-yeshu'}}; {{langx|syr|label=], ] and ]|እግዚኦ መሐረነ ክርስቶስ|translit=igizi'o meḥarene kirisitosi}}. | |||

| ] uses {{langx|el|προσευχή εν Πνεύματι|translit=prosefchí en Pneúmati|lit=prayer by the Spirit}}, or {{langx|el|νοερά προσευχή|translit=noerá prosefchí|lit=noetic prayer|link=no}}.<ref name="romanides1982">{{cite web |url=http://www.romanity.org/htm/rom.e.21.insous_xristos_i_zoi_tou_kosmou.01.htm |script-title=el:Ο Ιησούς Χριστός-η ζωή του κόσμου |trans-title=Jesus Christ-The Life of the World |last=Ρωμανίδης |first=Ιωάννης Σ. |author-link=John S. Romanides |translator-last=Κοντοστεργίου |translator-first=Δεσποίνης Δ. |publisher=The Romans: Ancient, Medieval and Modern |language=el |date=5–9 February 1982 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180813060113/http://www.romanity.org/htm/rom.e.21.insous_xristos_i_zoi_tou_kosmou.01.htm |archive-date=13 August 2018 |url-status=live |access-date=30 March 2019}} ''Original:'' {{cite web |url=http://www.romanity.org/htm/rom.19.en.jesus_christ_the_life_of_the_world.01.htm |title=Jesus Christ-The Life of the World |last=Romanides |first=John S. |author-link=John S. Romanides |publisher=The Romans: Ancient, Medieval and Modern |date=5–9 February 1982 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190208205029/http://www.romanity.org/htm/rom.19.en.jesus_christ_the_life_of_the_world.01.htm |archive-date=8 February 2019 |url-status=live |access-date=30 March 2019}}</ref> "Note: We are still searching the Fathers for the term 'Jesus prayer'. We would very much appreciate it if someone could come up with a patristic quote in Greek."<ref name="romanides">{{cite web |url=http://www.romanity.org/htm/rom.00.en.some_underlying_positions_of_this_website.htm |title=Some underlying positions of this website reflecting the studies herein included |last=Romanides |first=John S. |author-link=John S. Romanides |publisher=The Romans: Ancient, Medieval and Modern |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181119154828/http://www.romanity.org/htm/rom.00.en.some_underlying_positions_of_this_website.htm |archive-date=19 November 2018 |url-status=live |access-date=11 March 2019}}</ref>}} also known as '''The Prayer''',{{efn|{{langx|el|η ευχή|translit=i efchí|lit=the wish}}.}} is a short formulaic ], esteemed and advocated especially in ] and ]: | |||

| {{Blockquote|Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.}}] with the Jesus Prayer in ]: {{lang|ro|Doamne Iisuse Hristoase, Fiul lui Dumnezeu, miluieşte-mă pe mine păcătosul}} ("Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner")]]It is often repeated continually as a part of personal ] practice, its use being an integral part of the ] tradition of ] known as ].{{efn|{{langx|grc|ἡσυχάζω}}, {{transliteration|grc|isycházo}}, 'to keep stillness'.}} The prayer is particularly esteemed by the spiritual fathers of this tradition (see '']'') as a method of cleaning and opening up the mind and after this the heart ({{lang|grc-Latn|kardia}}), brought about first by the '''Prayer of the Mind''', or more precisely the '''Noetic Prayer''' ({{lang|el|Νοερά Προσευχή}}), and after this the '''Prayer of the Heart''' ({{lang|el|Καρδιακή Προσευχή}}). The ''Prayer of the Heart'' is considered to be the ''Unceasing Prayer'' that the ] advocates in the New Testament.{{efn|] {{bibleverse-nb|1 Thessalonians|5:17|KJV}}: Pray without ceasing.}} ] regarded the ''Jesus Prayer'' stronger than all other prayers by virtue of the power of the ].<ref name="Ware" /> | |||

| ] with Jesus Prayer in ]: ''Doamne Iisuse Hristoase, Fiul lui Dumnezeu, miluieşte-mă pe mine păcătosul'' ("Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, the sinner").]] | |||

| Though identified more closely with Eastern Christianity, the prayer is found in ] in the '']''.<ref name="§2667">{{cite web|title=Catechism of the Catholic Church, § 2667|url=https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P9F.HTM|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190107200306/https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P9F.HTM|archive-date=7 January 2019|access-date=15 March 2019|website=Vatican.va}}</ref> It also is used in conjunction with the innovation of ]<ref>{{Cite web|title=Anglican Prayer Beads|url=http://www.kingofpeace.org/prayerbeads.htm|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190201164947/http://www.kingofpeace.org/prayerbeads.htm|archive-date=1 February 2019|website=King of Peace Episcopal Church}}</ref> (Rev. Lynn Bauman in the mid-1980s). The prayer has been widely taught and discussed throughout the history of the ] and ]. The ancient and original form did not include the words "a sinner", which were added later.<ref name=Ware >''On the Prayer of Jesus'' by Ignatius Brianchaninov, Kallistos Ware 2006 {{ISBN|1-59030-278-8}} pages xxiii–xxiv</ref><ref name="Mathewes-Green2009">{{cite book|author=Frederica Mathewes-Green|title=The Jesus Prayer: The Ancient Desert Prayer that Tunes the Heart to God|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hHIG2hFP8QYC&pg=PA76|year=2009|publisher=Paraclete Press|isbn=978-1-55725-659-1|page=76–}}</ref> | |||

| The '''Jesus Prayer''' (Η Προσευχή του Ιησού) or "The Prayer" (Evkhee, Greek: Η Ευχή - the Wish) is a short, formulaic prayer esteemed and advocated within the ] church: | |||

| The Eastern Orthodox theology of the Jesus Prayer as enunciated in the 14th century by ] was generally rejected by ] theologians until the 20th century. ] called Gregory Palamas a saint,<ref>{{cite web| url=https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/homilies/1979/documents/hf_jp-ii_hom_19791130_turkey-efeso_fr.html |last=Pape Jean Paul II |author-link=Pope John Paul II |title=Messe à Ephèse |date=30 November 1979 |language=fr |website=Vatican.va |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180829000148/https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/homilies/1979/documents/hf_jp-ii_hom_19791130_turkey-efeso_fr.html |archive-date=29 August 2018 |url-status=live |access-date=16 March 2019}}</ref> a great writer, and an authority on ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/audiences/alpha/data/aud19901114en.html |last=Pope John Paul II |author-link=Pope John Paul II |title=The Spirit as 'Love Proceeding' |date=14 November 1990 |website=Vatican.va |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020820183856/https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/audiences/alpha/data/aud19901114en.html |archive-date=20 August 2002 |url-status=dead |access-date=16 March 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/audiences/1997/documents/hf_jp-ii_aud_12111997.html |last=Pope John Paul II |author-link=Pope John Paul II |title=General Audience |date=12 November 1997 |website=Vatican.va |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180829035034/http://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/audiences/1997/documents/hf_jp-ii_aud_12111997.html |archive-date=29 August 2018 |url-status=live |access-date=16 March 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/speeches/2000/apr-jun/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_20000525_jubilee-science_en.html |last=Pope John Paul II |author-link=Pope John Paul II |title=For the Jubilee of Scientists |date=25 May 2000 |website=Vatican.va |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180829000216/https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/speeches/2000/apr-jun/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_20000525_jubilee-science_en.html |archive-date=29 August 2018 |url-status=live |access-date=16 March 2019}}</ref> He also spoke with appreciation of hesychasm as "that deep union of grace which Eastern theology likes to describe with the particularly powerful term "'']''", ']{{'"}},<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.catholicculture.org/library/view.cfm?recnum=5660 |last=Pope John Paul II |author-link=Pope John Paul II |title=Eastern Theology Has Enriched the Whole Church |date=11 August 1996 |website=CatholicCulture.org |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070926231104/http://www.catholicculture.org/library/view.cfm?recnum=5660 |archive-date=26 September 2007 |url-status=dead |access-date=16 March 2019}}</ref> and likened the meditative quality of the Jesus Prayer to that of the Catholic ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/apost_letters/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_20021016_rosarium-virginis-mariae_en.html |last=Pope John Paul II |author-link=Pope John Paul II |title=Apostolic Letter Rosarium Virginis Mariae |date=16 October 2002 |website=Vatican.va |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20021027074834/https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/apost_letters/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_20021016_rosarium-virginis-mariae_en.html |archive-date=27 October 2002 |url-status=dead |access-date=16 March 2019}}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|Κύριε Ιησού Χριστέ, Υιέ του Θεού, ελέησόν με τον αμαρτωλόν.}} | |||

| {{cquote|Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.<ref></ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| The prayer has been widely taught and discussed throughout the history of the ]es. It is often repeated continually as a part of personal ] practice, its use being an integral part of the ] tradition of ] known as ] ({{Lang-el|''{{Polytonic|ἡσυχάζω}}''}}, ''hesychazo'', "to keep stillness"). The prayer is particularly esteemed by the spiritual fathers of this tradition (see '']'') as a method of opening up the heart (''kardia'') and bringing about the '''Prayer of the Heart''' (Καρδιακή Προσευχή). The Prayer of The Heart is considered to be the Unceasing Prayer that the apostle ] advocates in the New Testament.<ref></ref> | |||

| While its tradition, on historical grounds, also belongs to the ],<ref name="vatican.va"></ref><ref>See also ].</ref> and there have been a number of ] texts on the Jesus Prayer, its practice has never achieved the same popularity in the ] as in the Eastern Orthodox Church, although it is said on the ]. Moreover, the Eastern Orthodox theology of the Jesus Prayer enunciated in the fourteenth century by ] has never been fully accepted by the Roman Catholic Church.<ref>]'s , 11 August 1996.</ref> Nonetheless, in the Jesus Prayer there can be seen the Eastern counterpart of the ], which has developed to hold a similar place in the Christian West.<ref>] </ref> | |||

| ==Origins== | ==Origins== | ||

| The prayer's origin is |

The prayer's origin is the ], which was settled by the monastic ] and ] in the 5th century.<ref>Antoine Guillaumont reports the finding of an inscription containing the Jesus Prayer in the ruins of a cell in the Egyptian desert dated roughly to the period being discussed – Antoine Guillaumont, ''Une inscription copte sur la prière de Jesus'' in ''Aux origines du monachisme chrétien, Pour une phénoménologie du monachisme'', pp. 168–83. In ''Spiritualité orientale et vie monastique'', No 30. Bégrolles en Mauges (Maine & Loire), France: Abbaye de Bellefontaine.</ref> It was found inscribed in the ruins of a cell from that period in the Egyptian desert.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Stroumsa |first=Gedaliahu G. |date=1980 |title=GUILLAUMONT, ANTOINE, Aux origines du monachisme chrétien: Pour une phénoménologie du monachisme, Spiritualité orientale 30 - F 49720 Bégrolles en Mauge, Editions de l'Abbaye de Bellefontaine, 1979, 241 p |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156852780x00099 |journal=Numen |volume=27 |issue=2 |pages=287–288 |doi=10.1163/156852780x00099 |issn=0029-5973}}</ref> | ||

| A formula similar to the standard form of the Jesus Prayer is found in a letter attributed to ], who died in AD 407. This "Letter to an Abbot" speaks of "], son of God, have mercy" and "Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy on us" being used as ceaseless prayer.<ref></ref> | |||

| The practice of repeating the prayer continually dates back to at least the fifth century. The earliest known mention is in ''On Spiritual Knowledge and Discrimination'' of ] (400-ca.486), a work found in the first volume of the '']''. The Jesus Prayer is described in Diadochos's work in terms very similar{{Citation needed|date=March 2008}} to ]'s (ca.360-435) description in the ''Conferences'' 9 and 10 of the repetitive use of a passage of the ]. St. Diadochos ties the practice of the Jesus Prayer to the purification of the soul and teaches that repetition of the prayer produces inner peace. | |||

| What may be the earliest explicit reference to the Jesus Prayer in a form that is similar to that used today is in ''Discourse on Abba Philimon'' from the '']''. Philimon lived around AD 600.<ref>{{cite book |author=McGinn, Bernard |title=The essential writings of Christian mysticism |publisher=Modern Library |location=New York |year=2006 |page=125 |isbn=0-8129-7421-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rKkJs-KHCakC&pg=PA125}}</ref> The version cited by Philimon is, "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon me," which is apparently the earliest source to cite this standard version.<ref>{{cite book |author=Palmer, G.E.H. |title=The Philokalia, Volume 2 |date=15 September 2011 |publisher=Faber |location=London |page=507 |isbn=9780571268764 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aBkJAARHyoMC&pg=PA507}}</ref> While the prayer itself was in use by that time, ] writes that "We are still searching the Fathers for the term 'Jesus prayer'."<ref name="romanides" /> | |||

| The use of the Jesus Prayer is recommended in the '']'' of ] (ca.523–606) and in the work of ] (ca. eighth century), ''Pros Theodoulon,'' found in the first volume of the ''Philokalia.'' Ties to a similar prayer practice and theology appear in the fourteenth century work of an unknown English monk '']''. The use of the Jesus Prayer according to the tradition of the ''Philokalia'' is the subject of the nineteenth century anonymous Russian spiritual classic ''].'' | |||

| A similar idea is recommended in the '']'' of ] (circa 523–606), who recommends the regular practice of a ''monologistos'', or one-worded "Jesus Prayer".<ref name="Mathewes-Green2009" /> The use of the Jesus Prayer according to the tradition of the ''Philokalia'' is the subject of the 19th century anonymous Russian spiritual classic '']'', also in the original form, without the addition of the words "a sinner".<ref name="wayofpilgrim" /> | |||

| Though the Jesus Prayer has been practiced through the centuries as part of the Eastern tradition, in the twentieth century it also began to be used in some Western churches, including some Roman Catholic and Anglican churches. | |||

| ==Eastern Orthodoxy== | |||

| ==Theology== | |||

| {{ |

{{Eastern Orthodox sidebar}} | ||

| {{see also|Eastern Orthodox theology}} | |||

| The ] practice of the Jesus Prayer is founded on the biblical view by which God's name is conceived as the place of his presence.<ref name="raduca-2006">{{in lang|ro}} Vasile Răducă, ''Ghidul creştinului ortodox de azi'' (''Guide for the contemporary Eastern Orthodox Christian''), second edition, ], ], 2006, p. 81, {{ISBN|978-973-50-1161-1}}.</ref> Orthodox mysticism has no images or representations. The mystical practice (the prayer and the meditation) doesn't lead to perceiving representations of God (see below ]). Thus, the most important means of a life consecrated to praying is the invoked ''name of God'', as it is emphasized since the 5th century by the ] ], or by the later ] ]. For the Orthodox the power of the Jesus Prayer comes not only from its content, but from the very invocation of Jesus' name.<ref>{{in lang|ro}} ], ''Ortodoxia'' (''The Orthodoxy''), translation from ], Paideia Ed., ], 1997, pp. 161, 162–163, {{ISBN|973-9131-26-3}}.</ref> | |||

| The Jesus Prayer is composed of two statements. The first one is a ], acknowledging the ] of ]. The second one is the acknowledgment of ones own sinfulness. Out of them the petition itself emerges: "have mercy."<ref name="panagiotis-ro">{{Ro icon}} Christopher Panagiotis, ''Rugăciunea lui Iisus. Unirea minţii cu inima şi a omului cu Dumnezeu'' (''Jesus prayer. Uniting the mind with the heart and man with God''), translation from ], second edition, Panaghia Ed., Rarău Monastery, ], pp. 6, 12-15, 130, ISBN 978-973-88218-6-6.</ref>{{Dubious|date=November 2008}} | |||

| The ] practice of the Jesus Prayer is founded on the biblical view by which God's name is conceived as the place of his presence.<ref name="raduca-2006">{{Ro icon}} Fr. Vasile Răducă, ''Ghidul creştinului ortodox de azi'' (''Guide for the contemporary Eastern Orthodox Christian''), second edition, ], ], 2006, p. 81, ISBN 978-973-50-1161-1.</ref> The Eastern Orthodox mysticism has no images or representations. The mystical practice (the prayer and the meditation) doesn't lead to perceiving representations of God (see below ]). Thus, the most important means of a life consecrated to praying is the invoked ''name of God'', as it is emphasized since the fifth century by the ] ], or by the later ] ]. For the Eastern Orthodox the power of the Jesus Prayer comes not only from its content, but from the very invocation of the Jesus' name.<ref name="bulgakov-orthodoxy">{{Ro icon}} ], ''Ortodoxia'' (''The Orthodoxy''), translation from ], Paideia Ed., ], 1997, pp. 161, 162-163, ISBN 973-9131-26-3.</ref> | |||

| ===Scriptural roots=== | ===Scriptural roots=== | ||

| The Jesus Prayer combines three ]: the ] hymn of the ] ] {{bibleverse-nb|Philippians|2:6–11|KJV}} (verse 11: "Jesus Christ is Lord"), the ] of ] {{bibleverse-nb|Luke|1:31–35|KJV}} (verse 35: "Son of God"), and the ] of Luke {{bibleverse-nb|Luke|18:9–14|KJV}}, in which the Pharisee demonstrates the improper way to pray (verse 11: "God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even as this publican"), whereas the Publican prays correctly in humility (verse 13: "God be merciful to me a sinner").{{efn|"Orthodox tradition is aware that the heart, besides pumping blood, is, when conditioned properly, the place of communion with God by means of unceasing prayer, i.e. unceasing memory of God. The words of Christ", his ] in ] {{bibleverse-nb|Matthew|5:3–10|KJV}} ({{langx|grc-x-koine|"]"|lit=Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God|label=verse 8}}), "are taken very seriously because they have been fulfilled in all those who were graced with glorification both before and after the Incarnation. In the light of this one may turn to" the exhortations of Paul about "unceasing prayer" ({{langx|el|"αδιάλειπτος προσευχή"}}) in his ] {{bibleverse-nb|1 Thessalonians|5:16–22|KJV}} ({{langx|grc-x-koine|"]"|lit=pray unceasingly|label=verse 17}}). "Luke was a student and companion of Paul, his writings presuppose and reflect this esoteric life in Christ."<ref name="romanides1982" /> Closely related to ]­'s ] of {{bibleverse-nb|Luke|18:9–14|KJV}} ({{langx|grc-x-koine|"]"|lit=God be merciful to me a sinner|label=verse 13}}) are his ] of {{bibleverse-nb|Luke|17:11–19|KJV}} ({{langx|grc-x-koine|"]"|lit=Jesus, Master, have mercy on us|label=verse 13}}) and his ] of {{bibleverse-nb|Luke|18:35–43|KJV}} ({{langx|grc-x-koine|"]"|lit=Jesus, thou son of David, have mercy on me|label=verse 38}}). ''Similar: Matthew {{bibleverse-nb|Matthew|9:27–31|KJV}}, {{bibleverse-nb|Matthew|20:29–34|KJV}} ({{langx|grc-x-koine|"]"|lit=son of David, have mercy on us|label=verses 9:27 and 20:30–31}}), ] {{bibleverse-nb|Mark|10:46–52|KJV}} ({{langx|grc-x-koine|"]"|lit=Jesus, thou son of David, have mercy on me|label=verse 47}}).''<ref name="§2667" /><ref name="goarch-jp">{{cite web |url=https://www.goarch.org/-/the-jesus-prayer |title=The Jesus Prayer |last=Tsichlis |first=Steven Peter |publisher=] |date=9 March 1985 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170523232615/https://www.goarch.org/-/the-jesus-prayer |archive-date=23 May 2017 |url-status=live |access-date=14 March 2019}}</ref>}} | |||

| Theologically, the Jesus Prayer is considered to be the response of the Holy Tradition to the lesson taught by the parable of ], in which the Pharisee demonstrates the improper way to pray by exclaiming: "Thank you Lord that I am not like the Publican", whereas the Publican prays correctly in humility, saying "Lord have mercy on me, a sinner" ({{bibleverse||Luke|18:10-14|KJV}}).<ref name="goarch-jp">Fr. Steven Peter Tsichlis, , ], accessed March 2, 2008.</ref> | |||

| ===Palamism, the underlying theology=== | ===Palamism, the underlying theology=== | ||

| ] of the '']'' by ] (15th century, ], ]). Talking with Christ: ] (left) and ] (right). Kneeling: ], ], and ]]] | |||

| {{Main|Palamism}} | |||

| ]<ref>Eastern Orthodox theology doesn't stand ]' interpretation to the ''Mystycal theology'' of ] (''modo sublimiori'' and ''modo significandi'', by which Aquinas unites positive and negative theologies, transforming the negative one into a correction of the positive one). Like pseudo-Denys, the Eastern Church remarks the ] between the two ways of talking about God and acknowledges the superiority of apophatism. Cf. Vladimir Lossky, op. cit., p. 55, ], op. cit., pp. 261–262.</ref> (negative theology) is the main characteristic of the Eastern theological tradition. ] is not conceived as ] or refusal to know God, because the Eastern theology is not concerned with abstract concepts; it is contemplative, with a discourse on things above rational understanding. Therefore, dogmas are often expressed antinomically.<ref>{{in lang|ro}} ], ''Teologia mistică a Bisericii de Răsărit'' (''The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church''), translation from ], Anastasia Ed., ], 1993, pp. 36–37, 47–48, 55, 71. {{ISBN|973-95777-3-3}}.</ref> This form of contemplation is experience of God, ], called the vision of God or, in Greek, ].<ref>The Vision of God by ] SVS Press, 1997. ({{ISBN|0-913836-19-2}})</ref>{{clarify|date=March 2019}} | |||

| For the Eastern Orthodox the knowledge or {{lang|el|]}} of the uncreated energies is usually linked to apophatism.<ref>{{in lang|ro}} ], ''Ascetica şi mistica Biserici Ortodoxe'' (''Ascetics and Mystics of the Eastern Orthodox Church''), Institutul Biblic şi de Misiune al BOR (] Publishing House), 2002, p. 268, {{ISBN|0-913836-19-2}}.</ref><ref>The Philokalia, Vol. 4 {{ISBN|0-571-19382-X}} Palmer, G.E.H; Sherrard, Philip; Ware, Kallistos (Timothy) On the Inner Nature of Things and on the Purification of the Intellect: One Hundred Texts ] (Nikitas Stethatos)</ref> | |||

| ] of the '']'' by ] (15th century, ], ]). Talking with Christ: ] (left) and ] (right). Kneeling: ], ], and ].]] | |||

| {{main|Tabor Light|World (theology)}} | |||

| {{Expand-section|date=June 2008}} | |||

| The ], a central principle in the Eastern Orthodox theology, was formulated by ] in the fourteenth century in support of the mystical practices of ] and against ]. It stands that God's ''essence'' ({{Lang-el|''{{polytonic|Οὐσία}}''}}, '']'') is distinct from God's ''energies'', or manifestations in the world, by which men can experience the Divine. The energies are "unbegotten" or "uncreated". They were revealed in various episodes of the ]: the ] seen by ], the ] on ] at the ]. | |||

| ]<ref>Eastern Orthodox theology doesn't stand ]' interpretation to the ''Mystycal theology'' of ] (''modo sublimiori'' and ''modo significandi'', by which Aquinas unites positive and negative theologies, transforming the negative one into a correction of the positive one). Like pseudo-Denys, the Eastern Church remarks the ] between the two ways of talking about God and acknowledges the superiority of apophatism. Cf. Vladimir Lossky, op. cit., p. 55, ], op. cit., pp. 261-262.</ref> (negative theology) is the main characteristic of the Eastern theological tradition. isn't conceived as ] or refusal to know God, because the Eastern theology isn't concerned with abstract concepts; it is contemplative, with a discourse on things above rational understanding. Therefore dogmas are often expressed antinomically.<ref name="lossky">{{Ro icon}} ], ''Teologia mistică a Bisericii de Răsărit'' (''The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church''), translation from ], Anastasia Ed., ], 1993, pp. 36-37, 47-48, 55, 71. ISBN 973-95777-3-3.</ref> This form of contemplation, is experience of God, ] called the Vision of God or in Greek ].<ref>The Vision of God by ] SVS Press, 1997. (ISBN 0-913836-19-2)</ref> | |||

| For the Eastern Orthodox the knowledge or ] of the uncreated energies is usually linked to apophatism.<ref>{{Ro icon}} ], ''Ascetica şi mistica Biserici Ortodoxe'' (''Ascetics and Mystics of the Eastern Orthodox Church''), Institutul Biblic şi de Misiune al BOR (] Publishing House), 2002, p. 268, ISBN 973-9332-97-3.</ref><ref>The Philokalia, Vol. 4 ISBN 0-571-19382-X Palmer, G.E.H; Sherrard, Philip; Ware, Kallistos (Timothy) On the Inner Nature of Things and on the Purification of the Intellect: One Hundred Texts ] (Nikitas Stethatos)</ref> | |||

| ===Repentance in Eastern Orthodoxy=== | ===Repentance in Eastern Orthodoxy=== | ||

| {{see also|Eastern Orthodox view of sin}} | {{see also|Eastern Orthodox view of sin}} | ||

| The Eastern Orthodox Church holds a non-juridical view of sin, by contrast to the ] of ] for sin as articulated in the ], firstly{{Citation needed|date=September 2024}} by ] (as debt of honor){{Request quotation|date=August 2012}}) and ] (as a moral debt).{{Request quotation|date=August 2012}} The terms used in the East are less legalistic (''grace'', ''punishment''), and more medical (''sickness'', ''healing'') with less exacting precision. Sin, therefore, does not carry with it the guilt for breaking a rule, but rather the impetus to become something more than what men usually are. One repents not because one is or isn't virtuous, but because human nature can change. Repentance ({{Langx|grc|μετάνοια}}, '']'', "changing one's mind") isn't remorse, justification, or punishment, but a continual enactment of one's freedom, deriving from renewed choice and leading to restoration (the return to man's ]).<ref name="goarch-repentance">John Chryssavgis, {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080317005146/http://www.goarch.org/en/ourfaith/articles/article8493.asp |date=2008-03-17 }}, ]. Retrieved 21 March 2008.</ref> This is reflected in the ] of ] for which, not being limited to a mere confession of sins and presupposing recommendations or penalties, it is primarily that the priest acts in his capacity of spiritual father.<ref name="raduca-2006" /><ref name="russ-catechism">, ]. Retrieved 21 March 2008.</ref> The Mystery of Confession is linked to the spiritual development of the individual, and relates to the practice of choosing an elder to trust as his or her spiritual guide, turning to him for advice on the personal spiritual development, confessing sins, and asking advice. | |||

| ] by ] (ca. ], ], ]).]] | |||

| The Eastern Orthodox Church holds a non-juridical view of sin, by contrast to the ] of ] for sin as articulated in the ], firstly by ] (as debt of honor) and ] (as a moral debt). The terms used in the East are less legalistic (''grace'', ''punishment''), and more medical (''sickness'', ''healing'') with less exacting precision. Sin, therefore, does not carry with it the guilt for breaking a rule, but rather the impetus to become something more than what men usually are. One repents not because one is or isn't virtuous, but because human nature can change. Repentance ({{Lang-el|''{{polytonic|μετάνοια}}''}}, '']'', "changing one's mind") isn't remorse, justification, or punishment, but a continual enactment of one's freedom, deriving from renewed choice and leading to restoration (the return to man's ]).<ref name="goarch-repentance">John Chryssavgis, , ], accessed 21 March 2008.</ref> This is reflected in the ] of ] for which, not being limited to a mere confession of sins and presupposing recommendations or penalties, it is primarily that the priest acts in his capacity of spiritual father.<ref name="raduca-2006" /><ref name="russ-catechism">, ], accessed 21 March 2008.</ref> The Mystery of Confession is linked to the spiritual development of the individual, and relates to the practice of choosing an elder to trust as his or her spiritual guide, turning to him for advice on the personal spiritual development, confessing sins, and asking advice. | |||

| As stated at the local Council of Constantinople in 1157, Christ brought his redemptive sacrifice not to the ] alone, but to the ] as a whole. In the Eastern Orthodox theology redemption isn't seen as ''ransom''. It is the ''reconciliation'' of God with man, the manifestation of |

As stated at the local Council of Constantinople in 1157, Christ brought his redemptive sacrifice not to the ] alone, but to the ] as a whole. In the ] redemption isn't seen as ''ransom''. It is the ''reconciliation'' of God with man, the manifestation of God's love for humanity. Thus, it is not the anger of God the Father but His love that lies behind the sacrificial death of his son on the cross.<ref name="russ-catechism" /> | ||

| The redemption of man is not considered to have taken place only in the past, but continues to this day through ]. The initiative belongs to God, but presupposes man's active acceptance (not an action only, but an attitude), which is a way of perpetually receiving God.<ref name="goarch-repentance" /> | The redemption of man is not considered to have taken place only in the past, but continues to this day through ]. The initiative belongs to God, but presupposes man's active acceptance (not an action only, but an attitude), which is a way of perpetually receiving God.<ref name="goarch-repentance" /> | ||

| ===Distinctiveness from analogues in other religions=== | ===Distinctiveness from analogues in other religions=== | ||

| The practice of contemplative or meditative chanting is known in several religions including ], ], and ] (e.g. ], ]). The form of internal contemplation involving profound inner transformations affecting all the levels of the self is common to the traditions that posit the ontological value of personhood.<ref>Olga Louchakova, ''Ontopoiesis and Union in the Jesus Prayer: Contributions to Psychotherapy and Learning'', in ''Logos of Phenomenology and Phenomenology of Logos. Book Four – The Logos of Scientific Interrogation. Participating in Nature-Life-Sharing in Life'', ], 2006, p. 292, {{ISBN|1-4020-3736-8}}. ]: .</ref> | |||

| Although some aspects of the Jesus Prayer may resemble some aspects of other traditions, its Christian character is central rather than mere "local color". The aim of the Christian practicing it is not limited to attaining humility, love, or purification of sinful thoughts, but rather it is becoming holy and seeking union with God (''theosis''), which subsumes all the aforementioned virtues. Thus, for the Eastern Orthodox:<ref name="panagiotis-ro">{{in lang|ro}} Hristofor Panaghiotis, ''Rugăciunea lui Iisus. Unirea minţii cu inima şi a omului cu Dumnezeu'' (''Jesus prayer. Uniting the mind with the heart and man with God by Panagiotis K. Christou''), translation from ], second edition, Panaghia Ed., Rarău Monastery, ], pp. 6, 12–15, 130, {{ISBN|978-973-88218-6-6}}.</ref> | |||

| The practice of contemplative or meditative chanting is known from several religions including ], ], and ] (e.g. ], ]). The form of internal contemplation involving profound inner transformations affecting all the levels of the self is common to the traditions that posit the ontological value of personhood.<ref>Olga Louchakova, ''Ontopoiesis and Union in the Jesus Prayer: Contributions to Psychotherapy and Learning'', in ''Logos pf Phenomenology and Phenomenology of Logos. Book Four - The Logos of Scientific Interrogation. Participating in Nature-Life-Sharing in Life'', ], 2006, p. 292, ISBN 1-4020-3736-8. ]: .</ref> The history of these practices, including their possible spread from one religion to another, is not well understood. Such parallels (like between unusual psycho-spiritual experiences, breathing practices, postures, spiritual guidances of elders, peril warnings) might easily have arisen independently of one another, and in any case must be considered within their particular religious frameworks. | |||

| :* The Jesus Prayer is, first of all, a prayer addressed to God. It is not a means of self-deifying or self-deliverance, but a counterexample to ], repairing the breach it produced between man and God. | |||

| Although some aspects of the Jesus Prayer may resemble some aspects of other traditions, its Christian character is central rather than mere "local color." The aim of the Christian practicing it is not limited to attaining humility, love, or purification of sinful thoughts, but rather it is becoming holy and seeking union with God ('']''), which subsumes all the aforementioned virtues. Thus, for the Eastern Orthodox:<ref name="panagiotis-ro" /> | |||

| :* The aim is not to be dissolved or absorbed into nothingness or into God, or reach another state of mind, but to (re)unite{{efn|''Unite'' if referring to one person; ''reunite'' if talking at an anthropological level.}} with God (which by itself is a process) while remaining a distinct person. | |||

| :* It is an invocation of Jesus' name, because ] and ] are strongly linked to ] in ]. | |||

| :* The Jesus Prayer is, first of all, a prayer addressed to God. It's not a means of self-deifying or self-deliverance, but a counterexample to ], repairing the breach it produced between man and God. | |||

| :* In a modern context the continuing repetition is regarded by some as a form of ], the prayer functioning as a kind of ]. However, Orthodox users of the Jesus Prayer emphasize the ''invocation'' of the name of Jesus Christ that Hesychios describes in ''Pros Theodoulon'' which would be ] on the Triune God rather than simply emptying the mind.{{Citation needed|date=March 2008}} | |||

| :* The aim is not to be dissolved or absorbed into nothingness or into God, or reach another state of mind, but to (re)unite<ref>''Unite'' if referring to one person; ''reunite'' if talking at an anthropological level.</ref> with God (which by itself is a process) while remaining a distinct person. | |||

| :* It is an invocation of Jesus' name, because ] and ] are strongly linked to ] in Orthodox monasticism. | |||

| :* In a modern context the continuing repetition is regarded by some as a form of ], the prayer functioning as a kind of ]. However, Orthodox users of the Jesus Prayer emphasize the ''invocation'' of the name of Jesus Christ that St Hesychios describes in ''Pros Theodoulon'' which would be ] on the Triune God rather than simply emptying the mind.{{Citation needed|date=March 2008}} | |||

| :* Acknowledging "a sinner" is to lead firstly to a state of humbleness and repentance, recognizing one's own sinfulness. | :* Acknowledging "a sinner" is to lead firstly to a state of humbleness and repentance, recognizing one's own sinfulness. | ||

| :* Practicing the Jesus Prayer is strongly linked to mastering passions of both soul and body, e.g. by ]. For the Eastern Orthodox not the body is wicked, but "the bodily way of thinking" |

:* Practicing the Jesus Prayer is strongly linked to mastering passions of both soul and body, e.g. by ]. For the Eastern Orthodox it is not the body that is wicked, but "the bodily way of thinking"; therefore ] also regards the body. | ||

| :* Unlike ]s, the Jesus Prayer may be translated into whatever language the pray-er customarily uses. The emphasis is on the meaning, not on the mere utterance of certain sounds. | :* Unlike "]" in particular traditions of chanting ]s, the Jesus Prayer may be translated into whatever language the pray-er customarily uses. The emphasis is on the meaning, not on the mere utterance of certain sounds. | ||

| :* There is no emphasis on the psychosomatic techniques, which are merely seen as helpers for uniting the mind with the heart, not as prerequisites. | :* There is no emphasis on the psychosomatic techniques, which are merely seen as helpers for uniting the mind with the heart, not as prerequisites. | ||

| A magistral way of meeting God for the |

A magistral way of meeting God for the Orthodox,<ref name="kallistos-ware">{{in lang|ro}} ''Puterea Numelui sau despre Rugăciunea lui Iisus'' (''The Power of the Name. The Jesus Prayer in Orthodox Spirituality'') in ], ''Rugăciune şi tăcere în spiritualitatea ortodoxă'' (''Prayer and silence in the Orthodox spirituality''), translation from ], Christiana Ed., ], 2003, pp. 23, 26, {{ISBN|973-8125-42-1}}.</ref> the Jesus Prayer does not harbor any secrets in itself, nor does its practice reveal any esoteric truths.<ref>{{in lang|ro}} Fr. Ioan de la Rarău, ''Rugăciunea lui Iisus. Întrebări şi răspunsuri'' (''Jesus Prayer. Questions and answers''), Panaghia Ed., Rarău Monastery, ], p. 97. {{ISBN|978-973-88218-6-6}}.</ref> Instead, as a ] practice, it demands setting the mind apart from rational activities and ignoring the physical senses for the experiential knowledge of God. It stands along with the regular expected actions of the believer (prayer, almsgiving, repentance, fasting etc.) as the response of the Orthodox Tradition to ]'s challenge to "pray without ceasing" ({{bibleverse|1|Thess|5:17}}).<ref name="goarch-jp" /><ref name="panagiotis-ro" /> | ||

| ==Practice== | ==Practice== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| "There isn't Christian ] without ], especially there isn't Theology without Mysticism", writes ], for outside the Church the personal experience would have no certainty and objectivity, and "Church teachings would have no influence on souls without expressing a somehow inner experience of the truth it offers". For the Eastern Orthodox the aim isn't knowledge itself; theology is, finally, always a means serving a goal above any knowledge: ].<ref name="lossky" /> | |||

| ] by ] ({{circa|1410}}, ], ])]] | |||

| ===Techniques=== | |||

| The individual experience of the Eastern Orthodox mystic most often remains unknown. With very few exceptions, there aren't autobiographical writings on the inner life in the East. The mystical union pathway remains hidden, being unveiled only to the confessor or to the apprentices. "The mystical individualism has remained unknown to the spiritual life of the Eastern Church", remarks Lossky.<ref name="lossky" /> | |||

| There are no fixed rules for those who pray, "the way there is no mechanical, physical or mental technique which can force God to show his presence" (] ]).<ref name="kallistos-ware" /> | |||

| In '']'', the pilgrim advises, "as you draw your breath in, say, or imagine yourself saying, 'Lord Jesus Christ,' and as you breathe again, 'have mercy on me.'"<ref name="wayofpilgrim">{{cite book |last1=French |first1=R. M. |url=http://desertfathers.webs.com/thewayofthepilgrim.htm |title=The Way of a Pilgrim |editor-last=French |editor-first=R. M. |publisher=Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge |year=1930 |access-date=2016-02-05 |archive-date=2016-07-12 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160712040411/http://desertfathers.webs.com/thewayofthepilgrim.htm |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| The practice of the Jesus Prayer is integrated into the mental ] undertaken by the Orthodox ] in the practice of ]. Yet the Jesus Prayer is not limited only to monastic life or to clergy. All members of the Christian Church are advised to practice this prayer, laypeople and clergy, men, women and children. | |||

| The Jesus Prayer can be used for a kind of "psychological" self-analysis. According to the ''Way of the Pilgrim'' account and Mount Athos practitioners of the Jesus Prayer,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dailygreece.com/2008/03/post_246.php |title=greek news: Οι τρόποι της ευχής |publisher=Dailygreece.com |date=1999-02-22 |access-date=2010-07-03}}</ref> "one can have some insight on his or her current psychological situation by observing the intonation of the words of the prayer, as they are recited. Which word is stressed most. This self-analysis could reveal to the praying person things about their inner state and feelings, maybe not yet realised, of their unconsciousness."<ref name="byethost1">{{cite web|url=http://prayercraft.byethost8.com/JesusPrayer.htm |title=On the Jesus Prayer |publisher=Prayercraft.byethost8.com |date=2004-11-27 |access-date=2010-07-03}}</ref> | |||

| ].]] | |||

| In the Eastern tradition the prayer is said or prayed repeatedly, often with the aid of a ] (Russian: ''chotki''; Greek: ''komvoskini''), which is a cord, usually woolen, tied with many knots. The person saying the prayer says one repetition for each knot. It may be accompanied by ] and the ], signaled by beads strung along the prayer rope at intervals. | |||

| The prayer rope is "a tool of prayer". The use of the prayer rope, however, is not compulsory and it is considered as an aid to the beginners or the "weak" practitioners, those who face difficulties practicing the Prayer. | |||

| It should be noted here that the Jesus Prayer is ideally practiced under the guidance and supervision of a spiritual guide (pneumatikos, πνευματικός) especially when Psychosomatic techniques (like rhythmical breath) are incorporated. A person that acts as a spiritual "father" and advisor. Usually an officially certified by the Church ] (Pneumatikos Exolmologitis) or sometimes a spiritually experienced monk (called in ] Gerontas (]) or in Russian ]). It is not impossible for that person to be a layperson, usually a "Practical Theologician" (i.e. a person well versed in Orthodox Theology but without official credentials, certificates, diplomas etc.) but this is not a common practice either or at least it is not commonly advertised as ideal. | |||

| Also, a person might want to consciously stress one of the words of the prayer in particular when one wants to express a conscious feeling of situation. So in times of need stressing the 'have mercy' part can be more comforting or more appropriate. In times of failures, the 'a sinner' part, etc....)."<ref name="byethost1"/> | |||

| ====Psychosomatic techniques==== | |||

| There are not fixed, invariable rules for those who pray, "the way there is no mechanical, physical or mental technique which can force God to show his presence" (] ]).<ref name="kallistos-ware" /> | |||

| People who say the prayer as part of meditation often synchronize it with their breathing; breathing in while calling out to God (Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God) and breathing out while praying for mercy (have mercy on me, a sinner). Another option is to say (orally or mentally) the whole prayer while breathing in and again the whole prayer while breathing out and yet another, to breathe in recite the whole prayer, breathe out while reciting the whole prayer again. One can also hold the breath for a few seconds between breathing in and out. It is advised, in any of these three last cases, that this be done under some kind of spiritual guidance and supervision. | |||

| Monks often pray this prayer many hundreds of times each night as part of their private cell vigil ("cell rule"). Under the guidance of an Elder (Russian '']''; Greek ''Gerondas''), the monk aims to internalize the prayer, so that he is praying unceasingly. St. Diadochos of Photiki refers in ''On Spiritual Knowledge and Discrimination'' to the automatic repetition of the Jesus Prayer, under the influence of the ], even in sleep. This state is regarded as the accomplishment of Saint Paul's exhortation to the Thessalonians to "pray without ceasing" ({{bibleverse|1|Thessalonians|5:17|KJV}}). | |||

| The Jesus Prayer can also be used for a kind of "psychological" self-analysis. According to the "Way of the Pilgrim" account and Mount Athos practitioners of the Jesus Prayer , "one can have some insight on his or her current psychological situation by observing the intonation of the words of the prayer, as they are recited. Which word is stressed most. This self-analysis could reveal to the praying person things about their inner state and feelings, maybe not yet realised, of their unconsciousness." | |||

| "While praying the Jesus Prayer, one might notice that sometimes the word “Lord” is pronounced louder, more stressed, than the others, like: LORD Jesus Christ, (Son of God), have mercy on me, (a/the sinner). In this case, they say, it means that our inner self is currently more aware of the fact that Jesus is the Lord, maybe because we need reassurance that he is in control of everything (and our lives too). Other times, the stressed word is “Jesus”: Lord JESUS Christ, (Son of God), have mercy on me, (a/the sinner). In that case, they say, we feel the need to personally appeal more to his human nature, the one that is more likely to understands our human problems and shortcomings, maybe because we are going through tough personal situations. Likewise if the word “Christ” is stressed it could be that we need to appeal to Jesus as Messiah and Mediator, between humans and God the Father, and so on. When the word “Son” is stressed maybe we recognise more Jesus’ relationship with the Father. If “of God” is stressed then we could realise more Jesus’ unity with the Father. A stressed “have mercy on me” shows a specific, or urgent, need for mercy. A stressed “a sinner” (or “the sinner”) could mean that there is a particular current realisation of the sinful human nature or a particular need for forgiveness." | |||

| "In order to do this kind of self-analysis one should better start reciting the prayer relaxed and naturally for a few minutes – so the observation won’t be consciously “forced”, and then to start paying attention to the intonation as described above. | |||

| Also, a person might want to consciously stress one of the words of the prayer in particular when one wants to express a conscious feeling of situation. So in times of need stressing the “have mercy” part can be more comforting or more appropriate. In times of failures, the “a sinner” part, etc.…)." | |||

| ===Levels of the prayer=== | ===Levels of the prayer=== | ||

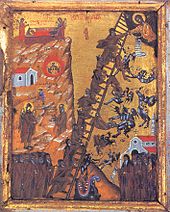

| ]'' (the steps toward theosis as described by ]) showing monks ascending (and falling from) the ladder to Jesus]] | |||

| ], a 20th-century ]n ] and theologian, writes<ref>{{in lang|ro}} ], ''Rugăciunea în Biserica de Răsărit'' (''Prayer in the Church of the East''), translation from ], Polirom Ed., ], 1996, pp. 29–31, {{ISBN|973-9248-15-2}}.</ref> about beginner's way of praying: initially, the prayer is excited because the man is emotive and a flow of psychic contents is expressed. In his view this condition comes, for the modern men, from the separation of the mind from the heart: "The prattle spreads the soul, while the silence is drawing it together." Old fathers condemned elaborate phraseologies, for one word was enough for the publican, and one word saved the thief on the cross. They only uttered Jesus' name by which they were contemplating God. For Evdokimov the acting faith denies any formalism which quickly installs in the external prayer or in the life duties; he quotes ]: "The prayer is not thorough if the man is self-conscious and he is aware he's praying." | |||

| "Because prayer is a living reality, a deeply personal encounter with the living God, it is not to be confined to any given classification or rigid analysis", says the ].<ref name="goarch-jp" /> As general guidelines for the practitioner, different number of levels (3, 7 or 9) in the practice of the prayer are distinguished by Orthodox fathers. They are to be seen as being purely informative, because the practice of the Prayer of the Heart is learned under personal spiritual guidance in Eastern Orthodoxy which emphasizes the perils of temptations when it's done by one's own. Thus, ], a 19th-century ] spiritual writer, talks about three stages:<ref name="goarch-jp" /> | |||

| ]'' (the steps toward ] as described by ]) showing monks ascending (and falling from) the ladder to Jesus.]] | |||

| # The oral prayer (the prayer of the lips) is a simple recitation, still external to the practitioner. | |||

| ], a twentieth century ]n philosopher and theologian, writes<ref name="evdokimov-prayer">{{Ro icon}} ], ''Rugăciunea în Biserica de Răsărit'' (''Prayer in the Church of the East''), translation from ], Polirom Ed., ], 1996, pp. 29-31, ISBN 973-9248-15-2.</ref> about beginner's way of praying: initially, the prayer is excited because the man is emotive and a flow of psychic contents is expressed. In his view this condition comes, for the modern men, from the separation of the mind from the heart: "The prattle spreads the soul, while the silence is drawing it together." Old fathers condemned elaborate phraseologies, for one word was enough for the publican, and one word saved the thief on the cross. They only uttered Jesus' name by which they were contemplating God. For Evdokimov the acting faith denies any formalism which quickly installs in the external prayer or in the life duties; he quotes ]: "The prayer is not thorough if the man is self-conscious and he is aware he's praying." | |||

| # The focused prayer, when "the mind is focused upon the words" of the prayer, "speaking them as if they were our own." | |||

| # The prayer of the heart itself, when the prayer is no longer something we do but who we are. | |||

| Once this is achieved the Jesus Prayer is said to become "self-active" ({{lang|el|αυτενεργούμενη}}). It is repeated automatically and unconsciously by the mind, becoming an internal habit like a (beneficial) ]. Body, through the uttering of the prayer, mind, through the mental repetition of the prayer, are thus unified with "the heart" (spirit) and the prayer becomes constant, ceaselessly "playing" in the background of the mind, like a background music, without hindering the normal everyday activities of the person.<ref name="byethost1"/> | |||

| Others, like Father ] Ilie Cleopa, one of the most representative spiritual fathers of contemporary ] monastic spirituality, talk about nine levels. They are the same path to ], more slenderly differentiated:<ref>{{in lang|ro}} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110916043316/http://biserica.org/WhosWho/DTR/I/IlieCleopa.html |date=2011-09-16 }} in ''Dicţionarul teologilor români'' (''Dictionary of Romanian Theologians''), electronic version, Univers Enciclopedic Ed., Bucharest, 1996.</ref> | |||

| "Because the prayer is a living reality, a deeply personal encounter with the living God, it is not to be confined to any given classification or rigid analysis"<ref name="goarch-jp" /> an on-line catechism reads. As general guidelines for the practitioner, different number of levels (3, 7 or 9) in the practice of the prayer are distinguished by Orthodox fathers. They are to be seen as being purely informative, because the practice of the Prayer of the Heart is learned under personal spiritual guidance in Eastern Orthodoxy which emphasizes the perils of temptations when it's done by one's own. Thus, ], a nineteenth century ] spiritual writer, talks about three stages:<ref name="goarch-jp" /> | |||

| # The prayer of the lips. | |||

| # The prayer of the mouth. | |||

| :* The focused prayer, when "the mind is focused upon the words" of the prayer, "speaking them as if they were our own." | |||

| # The prayer of the tongue. | |||

| # The prayer of the voice. | |||

| Once this is achieved the Jesus Prayer is said to become "self-active" (αυτενεργούμενη). It is repeated automatically and unconsciously by the mind, having a ], like a (beneficial) ]. Body, through the uttering of the prayer, mind, through the mental repetition of the prayer, are thus unified with "the heart" (spirit) and the prayer becomes constant, ceaselessly "playing" in the background of the mind, like a background music, without hindering the normal everyday activities of the person . | |||

| # The prayer of the mind. | |||

| # The prayer of the heart. | |||

| Others, like Father ] Ilie Cleopa, one of the most representative spiritual fathers of contemporary ] monastic spirituality,<ref name="cleopa-dict">{{Ro icon}} in ''Dicţionarul teologilor români'' (''Dictionary of Romanian Theologians''), electronic version, Univers Enciclopedic Ed., Bucharest, 1996.</ref> talk about nine levels (see ]). They are the same path to ], more slenderly differentiated: | |||

| # The active prayer. | |||

| # The all-seeing prayer. | |||

| # The contemplative prayer. | |||

| :* The prayer of the voice. | |||

| :* The prayer of the mind. | |||

| :* The prayer of the heart. | |||

| :* The active prayer. | |||

| :* The all-seeing prayer. | |||

| :* The contemplative prayer. | |||

| In its more advanced use, the monk aims to attain to a sober practice of the Jesus Prayer in the heart free of images. It is from this condition, called by Saints ] and Hesychios the "guard of the mind," that the monk is raised by the ] to contemplation.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| An interesting comparison in the Roman Canon is to be found in Jan van Ruysbroeck's poem The 12 Béguines, which similarly exemplarises the shedding of distractions such as personal concerns through a common meditative focus. | |||

| ==Variants of repetitive formulas== | ==Variants of repetitive formulas== | ||

| A number of different repetitive prayer formulas have been attested in the history of Eastern Orthodox monasticism: the Prayer of St. Ioannikios the Great (754–846): "My hope is the Father, my refuge is the Son, my shelter is the Holy Ghost, O Holy Trinity, Glory |

A number of different repetitive prayer formulas have been attested in the history of Eastern Orthodox monasticism: the Prayer of St. Ioannikios the Great (754–846): "My hope is the Father, my refuge is the Son, my shelter is the Holy Ghost, O Holy Trinity, Glory unto You," the repetitive use of which is described in his ''Life''; or the more recent practice of ]. | ||

| Similarly to the flexibility of the practice of the Jesus Prayer, there is no imposed standardization of its form. The prayer can be from as short as "Have mercy on me" ("Have mercy |

Similarly to the flexibility of the practice of the Jesus Prayer, there is no imposed standardization of its form. The prayer can be from as short as "Lord, have mercy" (]), "Have mercy on me" ("Have mercy upon us"), or even "Jesus", to its longer most common form. It can also contain a call to the ] (Virgin Mary), or to the saints. The single essential and invariable element is Jesus' name.<ref name="kallistos-ware" /> | ||

| :* Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. (a very common form) | :* Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. (a very common form) | ||

| :* Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me. (a very common form in the Greek tradition) | |||

| Sometimes "τον αμαρτωλόν" is translated "a sinner" but in Greek the article "τον" is used, a definite article so it reads "the sinner", | |||

| :* Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me. (common variant |

:* Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me. (common variant on ]<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090105074620/http://www.pelagia.org/htm/b01.en.a_night_in_the_desert_of_the_holy_mountain.05.htm|date=2009-01-05}}</ref>) | ||

| :* Jesus, have mercy.<ref>"The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios" by Dionysios Farasiotis</ref> | |||

| :* Lord have mercy. | |||

| :* Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on us.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.saintjonah.org/services/stpachomius.htm|title = The Rule of St. Pachomius}}</ref> | |||

| :* Jesus God in Heaven, Christ our Lord and Savior, have mercy on this poor sinner. | |||

| :* Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, have mercy on me, a sinner.<ref>{{Cite web|url = http://www.ntwrightpage.com/Wright_Prayer_Trinity.htm|title = The Prayer of the Trinity|date = 5 April 2016|access-date = 26 July 2010|archive-date = 18 March 2015|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150318054644/http://ntwrightpage.com/Wright_Prayer_Trinity.htm|url-status = dead}}</ref> | |||

| :* Jesus have mercy. (not an Orthodox formula) | |||

| :* Christ have mercy. | |||

| :* Jesus, Son of David, have pity on me! (not an Orthodox formula; based on the Gospels) | |||

| ==Catholic Church== | |||

| ==In various languages== | |||

| The Jesus Prayer is widely practiced among the 23 ]es. | |||

| The most common form, "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, the sinner", was composed in ] and it has been translated into numerous other languages, Eastern Orthodoxy not distinguishing between vernacular and ]s.<ref>"Orthodox Worship has always been celebrated in the language of the people. There is no official or universal liturgical language. Often, two or more languages are used in the Services to accommodate the needs of the congregation. Throughout the world, Services are celebrated in more than twenty languages which include such divers ones as ], ], ], ], ], English, and ].", , Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church, Ft. Myers, Florida, US, retrieved 20 March 2008.</ref><ref>But it does have a liturgical vocabulary.</ref> The following are languages of ] Eastern Orthodox Churches:<ref>Latin and Church Slavonic are included for historic reasons.</ref> | |||

| Part four of the '']'', which is dedicated to Christian prayer, devotes paragraphs 2665 to 2669 to prayer to Jesus. | |||

| *]: أيها الرب يسوع المسيح ابن الله, إرحمني أنا الخاطئ ''Ayyuha-r-Rabbu Yasū` al-Masīħ, Ibnu-l-Lāh, irħamnī ana-l-khāti<nowiki>'</nowiki>'' (''ana-l-khāti'a'' if prayed by a female). | |||

| *]: Տէր Յիսուս Քրիստոս Որդի Աստուծոյ ողորմեա ինձ մեղաւորիս | |||

| *]: Госпадзе Ісусе Хрысьце, Сыне Божы, памілуй мяне, грэшнага. ''Hospadzie Isusie Chryście, Synie Božy, pamiłuj mianie, hrešnaha''. | |||

| *]: Господи Иисусе Христе, Сине Божий, помилвай мен грешника. | |||

| *]: Господи Ісусе Христе Сыне Божїй помилѹй мѧ грѣшнаго. (''грѣшнѹю'' if prayed by a female) | |||

| *]: Gospodine Isuse Kriste, sine Božji, smiluj se meni grešniku. | |||

| *]: Pane Ježíši Kriste, Syne Boží, smiluj se nade mnou hříšným. | |||

| *]: Heer Jezus Christus, Zoon van God, ontferm U over mij, zondaar. | |||

| *]: Herra Jeesus Kristus, Jumalan Poika, armahda minua syntistä. | |||

| *]: უფალო იესუ ქრისტე, ძეო ღმრთისაო, შემიწყალე მე ცოდვილი. | |||

| *]: Herr Jesus Christus, Sohn Gottes, erbarme dich meiner, eines Sünders. (''einer Sünderin'' if prayed by a female) | |||

| *] {{polytonic|Κύριε Ἰησοῦ Χριστέ, Υἱέ τοῦ Θεοῦ, ἐλέησόν με τὸν ἁμαρτωλόν}} (''{{polytonic|τὴν ἁμαρτωλόν}}'' if prayed by a female) | |||

| *]: Domine Iesu Christe, Fili Dei, miserere mei, peccatoris. (''peccatricis'' if prayed by a female) | |||

| *]: Viešpatie Jėzau Kristau, Dievo Sūnau, pasigailėk manęs nusidėjelio.(''nusidėjelės'' if prayed by a female) | |||

| *]: Господи Исусе Христе, Сине Божји, помилуј ме грешниот. / Gospodi Isuse Hriste, Sine Bozhji, pomiluj me greshniot. | |||

| *]: Mulej Ġesù Kristu, Iben ta’ Alla l-ħaj, ikollok ħniena minni, midneb. | |||

| *]: Herre Jesus Kristus, forbarm deg over meg. | |||

| *]: Panie Jezu Chryste, Synu Boga, zmiłuj się nade mną, grzesznikiem. | |||

| *]: Doamne Iisuse Hristoase, Fiul lui Dumnezeu, miluieşte-mă pe mine păcătosul. (''păcătoasa'' if prayed by a female) | |||

| *]: Господи Иисусе Христе, Сыне Божий, помилуй мя грешнаго.(''грешную'' if prayed by a female) | |||

| **Variants: Господи, помилуй (The shortest form). | |||

| *]: Господе Исусе Христе, Сине Божји, помилуј ме грешног. / Gospode Isuse Hriste, Sine Božiji, pomiluj me grešnog. | |||

| *]: Pane Ježišu Kriste, Synu Boží, zmiluj sa nado mnou hriešnym. | |||

| *]: Señor Jesucristo, Hijo de Dios, ten piedad de mi, el pecador. | |||

| *]: Господи Ісусе Христе, Сину Божий, помилуй мене грішного. (''грішну'' if prayed by a female)/Господи, помилуй (The shortest form). | |||

| {{blockquote|To pray "Jesus" is to invoke him and to call him within us. His name is the only one that contains the presence it signifies. Jesus is the Risen One, and whoever invokes the name of Jesus is welcoming the Son of God who loved him and who gave himself up for him. This simple invocation of faith developed in the tradition of prayer under many forms in East and West. The most usual formulation, transmitted by the spiritual writers of the Sinai, Syria, and Mt. Athos, is the invocation, "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on us sinners." It combines the Christological hymn of {{bibleverse||Philippians|2:6–11|ESV}} with the cry of the publican and the blind men begging for light. By it the heart is opened to human wretchedness and the Savior's mercy. The invocation of the holy name of Jesus is the simplest way of praying always. When the holy name is repeated often by a humbly attentive heart, the prayer is not lost by heaping up empty phrases, but holds fast to the word and "brings forth fruit with patience." This prayer is possible "at all times" because it is not one occupation among others but the only occupation: that of loving God, which animates and transfigures every action in Christ Jesus.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P9F.HTM |title=Catechism of the Catholic Church, §§ 2666–2668 |website=Vatican.va |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190107200306/https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P9F.HTM |archive-date=7 January 2019 |url-status=live |access-date=15 March 2019}}</ref>}} | |||

| Languages of non autocephaly Orthodox Churches. (For example: The Hungarian Orthodox Church is subject to the Patriarchate of Moscow) | |||

| Similar methods of prayer in use in the Catholic Church are recitation, as recommended by ], of "O God, come to my assistance; O Lord, make haste to help me" or other verses of Scripture; repetition of a single monosyllabic word, as suggested by the ]; the method used in ]; the method used by ], based on the Aramaic invocation '']''; the use of ]; etc.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120310163401/http://www.monasticdialog.com/a.php?id=332 |date=2012-03-10 }}</ref> | |||

| *]: 主耶穌基督,上帝之子,憐憫我罪人。 | |||

| *]: Seigneur, Jésus Christ, Fils de Dieu, aie pitié de moi, pécheur. | |||

| *]: Ē ka Haku ‘o Iesu Kristo, Keiki kāne a ke Akua: e aloha mai ia‘u, ka mea hewa. | |||

| *]: Uram Jézus Krisztus, Isten Fia, könyörülj rajtam, bűnösön! | |||

| *]: Signore Gesù Cristo, Figlio di Dio, abbi misericordia di me peccatore. | |||

| *]: 主イイスス・ハリストス、神の子よ、我、罪人を憐れみ給え。 | |||

| *]: 하느님의 아들 주 예수 그리스도님, 죄 많은 저를 불쌍히 여기소서. | |||

| *]: Wahai Isa-al-Masih, Putra Allah, kasihanilah aku, sesungguhnya aku ini berdosa. | |||

| *]: Senhor Jesus Cristo, Filho de Deus, tende piedade de mim pecador! | |||

| The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' says: | |||

| ==In art== | |||

| {{blockquote|The name of Jesus is at the heart of Christian prayer. All liturgical prayers conclude with the words "through our Lord Jesus Christ". The ] reaches its high point in the words "blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus". The Eastern prayer of the heart, the Jesus Prayer, says: "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner." Many Christians, such as ], have died with the one word "Jesus" on their lips.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P1E.HTM |title=Catechism of the Catholic Church, § 435 |website=Vatican.va |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190107214744/https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__P1E.HTM |archive-date=7 January 2019 |url-status=live |access-date=15 March 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Jesus Prayer is referred in ]'s pair of stories '']''. It is also a central theme of the 2006 Russian film '']''. | |||

| The most usual formulation, transmitted by the spiritual writers of the Sinai, Syria, and Mt. Athos, is the invocation: "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on us sinners."<ref name="§2667" />}} | |||

| ==In the Catechism of the Catholic Church== | |||

| The Part Four of the Catechism, which is dedicated to the Christian Prayer, devoted paragraphs 2665 to 2669 to the Jesus Prayer. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{cquote|This simple invocation of faith developed in the tradition of prayer under many forms in East and West... It combines the Christological hymn of Philippians 2:6-11 with the cry of the publican and the blind men begging for light. By it the heart is opened to human wretchedness and the Savior's mercy.<ref name="vatican.va"/>}} | |||

| {{Portal|Christianity}} | |||

| <!-- Please keep entries in alphabetical order & add a short description ] --> | |||

| {{cquote|The invocation of the holy name of Jesus is the simplest way of praying always. When the holy name is repeated often by a humbly attentive heart, the prayer is not lost by heaping up empty phrases, but holds fast to the word and "brings forth fruit with patience." This prayer is possible "at all times" because it is not one occupation among others but the only occupation: that of loving God, which animates and transfigures every action in Christ Jesus.<ref></ref>}} | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=18em|small=yes}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| <!-- please keep entries in alphabetical order --> | |||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{ |

{{notelist}} | ||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| *]: | |||

| **] (deification, the search of union with God) | |||

| **] (or Divine Light, or Palamism), doctrine formulated by ] arguing for God's ] | |||

| *]: | |||

| **] (ascetical tradition of prayer) | |||

| **] (ascetical method) | |||

| **] (solitary monk); ] (elder teacher, in Russian tradition) | |||

| *]: | |||

| **] ({{Lang-el|Lord, have mercy}}), prayer of Christian liturgy | |||

| **] | |||

| **]; ]; ]; ] (prayer room) | |||

| *] (Russian dogmatic movement) | |||

| *] (similar ] devotion) | |||

| *] (Roman Catholic tradition) | |||

| *] | |||

| == |

==Further reading== | ||

| * ''The Jesus Prayer: Learning to Pray from the Heart'', by Per-Olof Sjögren, trans. by Sydney Linton; First Triangle ed. (London: Triangle, 1986, cop. 1975) {{ISBN|0-281-04237-3}} | |||

| *The article at the Orthodox Wiki | |||

| * ''Mount Athos Spirituality: The Jesus Prayer, Orthodox Psychotherapy and Hesychastic Anthropology'', by Robert Rapljenovic, KDP 2024 {{ISBN|979-8327883819}} | |||

| * by Fr. Steven Peter Tsichlis (Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America) | |||

| {{Catholic Prayers}} | |||

| * by Albert S Rossi (St. Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary) | |||

| * by Metropolitan Anthony Bloom | |||

| * by ] | |||

| * by Mother Alexandra | |||

| * by Archimandrite Fr. Jonah Mourtos | |||

| * by Bishop Kallistos of Diokleia | |||

| * by John K. Kotsonis, Ph.D. | |||

| * by Fr. Michael Plekon | |||

| * by Ken E. Norian, TSSF | |||

| *Hieromonk Ilie Cleopa preaching (video) | |||

| * (online book) by Fr. Theophanes (Constantine) | |||

| * A site for gazing (English and Greek) | |||

| * {{Ru icon}} | |||

| * Greek site in English with practical advice | |||

| * | |||

| * Guide for practice and numerous articles | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 03:35, 23 October 2024

Short formulaic prayer in Christianity Not to be confused with Lord's Prayer or prayers of Jesus.The Jesus Prayer, also known as The Prayer, is a short formulaic prayer, esteemed and advocated especially in Eastern Christianity and Catholicism:

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.

It is often repeated continually as a part of personal ascetic practice, its use being an integral part of the eremitic tradition of prayer known as hesychasm. The prayer is particularly esteemed by the spiritual fathers of this tradition (see Philokalia) as a method of cleaning and opening up the mind and after this the heart (kardia), brought about first by the Prayer of the Mind, or more precisely the Noetic Prayer (Νοερά Προσευχή), and after this the Prayer of the Heart (Καρδιακή Προσευχή). The Prayer of the Heart is considered to be the Unceasing Prayer that the Apostle Paul advocates in the New Testament. Theophan the Recluse regarded the Jesus Prayer stronger than all other prayers by virtue of the power of the Holy Name of Jesus.

Though identified more closely with Eastern Christianity, the prayer is found in Western Christianity in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. It also is used in conjunction with the innovation of Anglican prayer beads (Rev. Lynn Bauman in the mid-1980s). The prayer has been widely taught and discussed throughout the history of the Eastern Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church. The ancient and original form did not include the words "a sinner", which were added later. The Eastern Orthodox theology of the Jesus Prayer as enunciated in the 14th century by Gregory Palamas was generally rejected by Latin Church theologians until the 20th century. Pope John Paul II called Gregory Palamas a saint, a great writer, and an authority on theology. He also spoke with appreciation of hesychasm as "that deep union of grace which Eastern theology likes to describe with the particularly powerful term "theosis", 'divinization'", and likened the meditative quality of the Jesus Prayer to that of the Catholic Rosary.

Origins

The prayer's origin is the Egyptian desert, which was settled by the monastic Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers in the 5th century. It was found inscribed in the ruins of a cell from that period in the Egyptian desert.

A formula similar to the standard form of the Jesus Prayer is found in a letter attributed to John Chrysostom, who died in AD 407. This "Letter to an Abbot" speaks of "Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy" and "Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy on us" being used as ceaseless prayer.

What may be the earliest explicit reference to the Jesus Prayer in a form that is similar to that used today is in Discourse on Abba Philimon from the Philokalia. Philimon lived around AD 600. The version cited by Philimon is, "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon me," which is apparently the earliest source to cite this standard version. While the prayer itself was in use by that time, John S. Romanides writes that "We are still searching the Fathers for the term 'Jesus prayer'."

A similar idea is recommended in the Ladder of Divine Ascent of John Climacus (circa 523–606), who recommends the regular practice of a monologistos, or one-worded "Jesus Prayer". The use of the Jesus Prayer according to the tradition of the Philokalia is the subject of the 19th century anonymous Russian spiritual classic The Way of a Pilgrim, also in the original form, without the addition of the words "a sinner".

Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodox theologyThe hesychastic practice of the Jesus Prayer is founded on the biblical view by which God's name is conceived as the place of his presence. Orthodox mysticism has no images or representations. The mystical practice (the prayer and the meditation) doesn't lead to perceiving representations of God (see below Palamism). Thus, the most important means of a life consecrated to praying is the invoked name of God, as it is emphasized since the 5th century by the Thebaid anchorites, or by the later Athonite hesychasts. For the Orthodox the power of the Jesus Prayer comes not only from its content, but from the very invocation of Jesus' name.

Scriptural roots

The Jesus Prayer combines three Bible verses: the Christological hymn of the Pauline epistle Philippians 2:6–11 (verse 11: "Jesus Christ is Lord"), the Annunciation of Luke 1:31–35 (verse 35: "Son of God"), and the Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican of Luke 18:9–14, in which the Pharisee demonstrates the improper way to pray (verse 11: "God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even as this publican"), whereas the Publican prays correctly in humility (verse 13: "God be merciful to me a sinner").

Palamism, the underlying theology

Apophatism (negative theology) is the main characteristic of the Eastern theological tradition. Incognoscibility is not conceived as agnosticism or refusal to know God, because the Eastern theology is not concerned with abstract concepts; it is contemplative, with a discourse on things above rational understanding. Therefore, dogmas are often expressed antinomically. This form of contemplation is experience of God, illumination, called the vision of God or, in Greek, theoria.

For the Eastern Orthodox the knowledge or noesis of the uncreated energies is usually linked to apophatism.

Repentance in Eastern Orthodoxy

See also: Eastern Orthodox view of sinThe Eastern Orthodox Church holds a non-juridical view of sin, by contrast to the satisfaction view of atonement for sin as articulated in the West, firstly by Anselm of Canterbury (as debt of honor)) and Thomas Aquinas (as a moral debt). The terms used in the East are less legalistic (grace, punishment), and more medical (sickness, healing) with less exacting precision. Sin, therefore, does not carry with it the guilt for breaking a rule, but rather the impetus to become something more than what men usually are. One repents not because one is or isn't virtuous, but because human nature can change. Repentance (Ancient Greek: μετάνοια, metanoia, "changing one's mind") isn't remorse, justification, or punishment, but a continual enactment of one's freedom, deriving from renewed choice and leading to restoration (the return to man's original state). This is reflected in the Mystery of Confession for which, not being limited to a mere confession of sins and presupposing recommendations or penalties, it is primarily that the priest acts in his capacity of spiritual father. The Mystery of Confession is linked to the spiritual development of the individual, and relates to the practice of choosing an elder to trust as his or her spiritual guide, turning to him for advice on the personal spiritual development, confessing sins, and asking advice.

As stated at the local Council of Constantinople in 1157, Christ brought his redemptive sacrifice not to the Father alone, but to the Trinity as a whole. In the Eastern Orthodox theology redemption isn't seen as ransom. It is the reconciliation of God with man, the manifestation of God's love for humanity. Thus, it is not the anger of God the Father but His love that lies behind the sacrificial death of his son on the cross.

The redemption of man is not considered to have taken place only in the past, but continues to this day through theosis. The initiative belongs to God, but presupposes man's active acceptance (not an action only, but an attitude), which is a way of perpetually receiving God.

Distinctiveness from analogues in other religions

The practice of contemplative or meditative chanting is known in several religions including Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam (e.g. japa, zikr). The form of internal contemplation involving profound inner transformations affecting all the levels of the self is common to the traditions that posit the ontological value of personhood.

Although some aspects of the Jesus Prayer may resemble some aspects of other traditions, its Christian character is central rather than mere "local color". The aim of the Christian practicing it is not limited to attaining humility, love, or purification of sinful thoughts, but rather it is becoming holy and seeking union with God (theosis), which subsumes all the aforementioned virtues. Thus, for the Eastern Orthodox:

- The Jesus Prayer is, first of all, a prayer addressed to God. It is not a means of self-deifying or self-deliverance, but a counterexample to Adam's pride, repairing the breach it produced between man and God.

- The aim is not to be dissolved or absorbed into nothingness or into God, or reach another state of mind, but to (re)unite with God (which by itself is a process) while remaining a distinct person.

- It is an invocation of Jesus' name, because Christian anthropology and soteriology are strongly linked to Christology in Orthodox monasticism.

- In a modern context the continuing repetition is regarded by some as a form of meditation, the prayer functioning as a kind of mantra. However, Orthodox users of the Jesus Prayer emphasize the invocation of the name of Jesus Christ that Hesychios describes in Pros Theodoulon which would be contemplation on the Triune God rather than simply emptying the mind.

- Acknowledging "a sinner" is to lead firstly to a state of humbleness and repentance, recognizing one's own sinfulness.

- Practicing the Jesus Prayer is strongly linked to mastering passions of both soul and body, e.g. by fasting. For the Eastern Orthodox it is not the body that is wicked, but "the bodily way of thinking"; therefore salvation also regards the body.

- Unlike "seed syllables" in particular traditions of chanting mantras, the Jesus Prayer may be translated into whatever language the pray-er customarily uses. The emphasis is on the meaning, not on the mere utterance of certain sounds.

- There is no emphasis on the psychosomatic techniques, which are merely seen as helpers for uniting the mind with the heart, not as prerequisites.