| Revision as of 22:28, 22 October 2010 editSmackBot (talk | contribs)3,734,324 editsm Date maintenance tags and/or general fixes: build X1← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:30, 26 December 2024 edit undoGråbergs Gråa Sång (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers57,698 editsm →Terminology | ||

| (432 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Original research}} | {{Original research|date=October 2010}} | ||

| {{Use British English|date=May 2024}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} | |||

| ] is often cited as a possible author of Shakespeare's plays.]] | |||

| {{short description|Alternative Shakespeare authorship theory}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The '''Baconian theory''' of ] |

The '''Baconian theory''' of ] contends that ], philosopher, essayist and scientist, wrote the ] that are attributed to ]. Various explanations are offered for this alleged subterfuge, most commonly that Bacon's rise to high office might have been hindered if it became known that he wrote plays for the public stage. The plays are credited to Shakespeare, who, supporters of the theory claim, was merely a front to shield the identity of Bacon. All but a few academic Shakespeare scholars reject the arguments for Bacon authorship, as well as those for all ]. | ||

| The theory was first put forth in the mid-nineteenth century, based on perceived correspondences between the philosophical ideas found in Bacon’s writings and the works of Shakespeare. Legal and autobiographical allusions and cryptographic ciphers and codes were later found in the plays and poems to buttress the theory. The Baconian theory gained popularity and attention in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The academic consensus is that Shakespeare wrote the works bearing his name. Supporters of Bacon continue to argue for his candidacy through organisations, books, newsletters, and websites. | |||

| The mainstream view is that William Shakspeare of Stratford, an actor in the ] (later the ]), wrote the poems and plays that bear his name. The Baconians, however, hold that scholars are so focused on the details of Shakespeare's life that they neglect to investigate the many facts that they see as connecting Bacon to the Shakespearean work. "It is perfectly true," declared Harry Stratford Caldecott in an 1895 ] lecture, "that the great bulk of English critical opinion refuses to recognise or admit the fact that there is any question or controversy about the matter. If it did so, it would find itself face to face with a problem which it would be absolutely unable to determine in harmony with preconceived ideas. Consequently, it endeavours to ignore or waive aside any suggestion of a doubt as to the authorship of these immortal works, as if it were an ugly spectre or troublesome nightmare. It is, notwithstanding, a perfectly tangible, flesh-and-blood difficulty and must sooner or later be faced and grappled with in a manly and straightforward way."<ref>Caldecott: ''Our English Homer'', p. 5.</ref> The Baconians believe that there is reasonable doubt about William Shakespeare's claim of authorship and cite the many possible connections between Sir Francis Bacon and the Shakespearean work. | |||

| The main Baconian evidence is founded on the presentation of a motive for concealment, the circumstances surrounding the first known performance of '']'', the close proximity of Bacon to the ] letter upon which many scholars think '']'' was based, perceived allusions in the plays to Bacon's legal acquaintances, the many supposed parallels with the plays of Bacon's published work and entries in the Promus (his private wastebook), Bacon's interest in civil histories, and ostensible autobiographical allusions in the plays. Since Bacon had first-hand knowledge of government cipher methods,<ref>Jardine, Lisa; Stewart, Alan: ''Hostage to Fortune: The Troubled Life of Sir Francis Bacon'' (Hill and Wang, 1999), p. 55.</ref> most Baconians see it as feasible that he left his signature somewhere in the Shakespearean work. | |||

| Per this theory, Shakespeare is claimed to have acted as a mask for the concealed author. Supporters of the mainstream view, often referred to as "Stratfordian", dispute all contentions in favour of Bacon, and criticise Bacon's poetry as not being comparable in quality with that of Shakespeare. | |||

| ==Mainstream view== | |||

| The ] view is that the author known as "Shakespeare" was the same William Shakespeare who was born in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564, moved to London and became an actor, and "sharer" (part-owner) of the acting company called the ] (which owned the ] and the ] in London). He divided his time between London and Stratford, and retired there around 1613 before his death in 1616. In 1623, seven years after his death (and after the death of most of the proposed authorship candidates), his plays were collected for publication in the ] edition. | |||

| Shakespeare of Stratford is further identified by the following evidence: He left gifts in his will to actors from the London company; the man from Stratford and the author of the works share a common name; and commendatory poems in the 1623 First Folio of Shakespeare's works refer to the "Swan of Avon" and his "Stratford monument".<ref>For a full account of the documents relating to Shakespeare's life, see ], ''William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life'' (OUP, 1987)</ref> Mainstream scholars believe that the latter phrase refers to the ] in ], Stratford, which refers to Shakespeare as a writer (comparing him to ] and calling his writing a "living art"), and was described as such by visitors to Stratford as far back as the 1630s.<ref>Shakespeare and his Rivals: A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy" by George McMichael and Edgar M. Glenn, a pair of college professors. It is copyright 1962, and published by The Odyssey Press, in NY. lib of congress card #62-11942., page 41.</ref> | |||

| Several pieces of circumstantial evidence support the mainstream view: In a 1592 pamphlet by the playwright Robert Greene called "Greene's Groatsworth of Wit", Greene chastises a playwright whom he calls "Shake-scene", calling him "an upstart crow" and a "''Johannes factotum''" (a "]", a man able to feign skill), thus suggesting that people were aware of a writer named Shakespeare.<ref>Michell, John: ''Who Wrote Shakespeare?'' (Thames & Hudson: 2000), p.68; also Anderson, Mark, "Shakespeare" by Another Name", New York City: Gotham Books. ISBN 1592402151</ref> Also, poet ] once referred to Shakespeare as "our English ]". Additionally, Shakespeare's grave monument in Stratford, built within a decade of his death, currently features him with a pen in hand, suggesting that he was known as a writer. | |||

| Critics of the mainstream view have challenged most if not all of the above assertions,{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} claiming that there is no direct evidence which clearly identifies Shakespeare of Stratford as a playwright. These critics note that the only theatrical reference in his will (the gifts to fellow actors) were interlined - i.e.: inserted between previously written lines - and thus subject to doubt; the term "Swan of Avon" can be interpreted in numerous ways; that "Greene's Groatsworth of Wit" could imply that Shakespeare was being given credit for the work of other writers;<ref>Michell, John: ''Who Wrote Shakespeare?'' (Thames & Hudson: 2000), p.68; also Anderson, Mark, "Shakespeare by Another Name", New York City: Gotham Books. ISBN 1592402151</ref> that Davies' mention of "our English Terence" is a mixed reference as ], ], ] and many contemporary Elizabethan scholars knew Terence as a front man for one or more Roman aristocratic playwrights<ref name="andersonmark">{{cite book |last=Anderson |first=Mark |authorlink=Mark Anderson (writer)|title="Shakespeare" by Another Name |publisher=Gotham Books |location=New York City |isbn=1592402151 |year=2005}}, also Michell, John: ''Who Wrote Shakespeare?'' (Thames & Hudson: 2000), p.196</ref> and they assert that Shakespeare's grave monument was altered after its original creation, with the original monument merely showing a man holding a grain sack.<ref>{{cite book |last=Anderson |first=Mark |authorlink=Mark Anderson |title="Shakespeare" by Another Name |publisher=Gotham Books |location=New York City |isbn=1592402151 |year=2005}}, also Michell, John: ''Who Wrote Shakespeare?'' (Thames & Hudson: 2000), p.89</ref> | |||

| ==Terminology== | ==Terminology== | ||

| {{see also|Spelling of Shakespeare's name}} | |||

| Sir ] was a major scientist, philosopher, ], diplomat, essayist, historian and successful politician, who served as ] (1607), ] (1613) and ] (1618). | |||

| Sir ] (1561 – 1626) was an English scientist, philosopher, ], diplomat, essayist, historian and successful politician who served as ] in 1607, ] in 1613 and ] in 1618. Those who subscribe to the theory that Bacon wrote Shakespeare's works refer to themselves as "Baconians", while dubbing those who maintain the orthodox view that ] of ] wrote his own works "Stratfordians". | |||

| Baptised as "Gulielmus filius Johannes Shakspere"<ref>{{cite web |title=The Birth and Burial Records of William Shakespeare |url=https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/blogs/birth-and-burial-records-william-shakespeare/ |work=Shakespeare Birthplace Trust |date=11 April 2012 |access-date=22 March 2022}}</ref> (William son of John Shakspere) on 26 April 1564, the traditionally accepted author's surname had several variant spellings during his lifetime, but his signature is most commonly spelled "Shakspere". Baconians often use "Shakspere"<ref>Caldecott: ''Our English Homer'', p. 7.</ref> or "Shakespeare" for the glover's son and actor from Stratford, and "Shake-speare" for the author to avoid the assumption that the Stratford man wrote the works attributed to him. | |||

| Those who subscribe to the theory that Sir Francis Bacon wrote the Shakespeare work generally refer to themselves as "Baconians", while dubbing those who maintain the orthodox view that William Shakspeare of ] wrote them "Stratfordians". | |||

| Baptised as William Shakspere, the Stratford man used several variants of his name during his lifetime, including "Shakespeare". Baconians use "Shakspere"<ref>Caldecott: ''Our English Homer, p. 7.</ref> or "Shakespeare" for the glover's son and actor from Stratford, and "Shake-speare" for the author to avoid the assumption that the Stratford man wrote the work. | |||

| ==History of Baconian theory== | ==History of Baconian theory== | ||

| A pamphlet entitled '']'' (circa 1786) and alleged research by ] have been described by some as the earliest instances of the claim that Bacon wrote Shakespeare's works, but the Wilmot research has been exposed as a forgery, and the pamphlet makes no direct reference to Bacon.<ref>James Shapiro, "Forgery on Forgery," TLS (26 March 2010), 14–15.</ref>{{efn|The argument concerning the pamphlet depends on the assumption that the "pig" is a coded reference to the name "bacon".}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In a letter to the ] and poet ] in 1603, Bacon refers to himself as a "concealed poet".<ref>Lambeth Palace MS 976, folio 4. The signature and docket is in Bacon's hand; the body of the letter is a transcription by one of his scriveners.</ref> Baconians claim that certain of his contemporaries knew of and hinted at this secret authorship. The satirical poets ] (1574–1656) and ] (1575–1634) in the so-called Hall-Marston satires,<ref>Hall, Joseph: ''Virgidemarium'' (1597-1598), Book 2, Satire 1 ("For shame write better Labeo ."); Book 4, Satire 1 ("Labeo is whip't and laughs me in the face ."); Book 6, Satire 1 ("Tho Labeo reaches right ...")</ref><ref>Marston, John, ''The Metamorphosis of Pygmalion's Image And Certaine Satyres'' (1598). See "The Authour in prayse" of his precedent poem, "So Labeo did complain his love was stone ...", and "Reactio" Satire IV: "Fond Censurer! Why should those mirrors seem ."</ref> discuss between them a character called Labeo in relation to Shakespeare's long poem "]" (1593). Perceiving that Hall is criticising "Venus and Adonis" as a lewd Mirror-genre poem,<ref>] (1559) was a collection of about 100 Renaissance moralistic poems on the subject of sinners suffering divine retribution. It is arguable that "Venus and Adonis" fits into the genre because Adonis's lust and his subsequent death in the boar hunt could be interpreted as divine retribution.</ref> Marston writes "What, not ''mediocria firma'' from thy spight?", "''mediocria firma''" being the Bacon family motto. | |||

| The idea |

The idea was first proposed by ] (no relation) in lectures and conversations with intellectuals in America and Britain. William Henry Smith was the first to publish the theory in a letter to ] published in the form of a sixteen-page pamphlet entitled ''Was Lord Bacon the Author of Shakespeare's Plays?''<ref>Smith, William Henry. , a pamphlet-letter addressed to Lord Ellesmere (William Skeffington, 1856).</ref> Smith suggested that several letters to and from Francis Bacon hinted at his authorship. A year later, both Smith and Delia Bacon published books expounding the Baconian theory.<ref>Smith, William Henry: ''Bacon and Shakespeare: An Inquiry Touching Players, Playhouses, and Play-writers in the Days of Elizabeth'' (John Russell Smith, 1857).</ref><ref>Bacon, Delia: ''The Philosophy of the Plays of Shakespeare Unfolded'' (1857); ''''.</ref> In Delia Bacon's work, "Shakespeare" was represented as a group of writers, including Francis Bacon, ] and ], whose agenda was to propagate an anti-monarchical system of philosophy by secreting it in the text. | ||

| In 1867, in the library of ], |

In 1867, in the library of ], John Bruce happened upon a bundle of bound documents, some of whose sheets had been ripped away. It had comprised numerous of Bacon's oratories and disquisitions, and had also apparently held copies of the plays '']'' and '']'', '']'' and '']'', but these had been removed. On the outer sheet was scrawled repeatedly the names of Bacon and Shakespeare along with the name of ]. There were several quotations from Shakespeare and a reference to the word ], which appears in Shakespeare's '']'' and Nashe's ''Lenten Stuff''. The Earl of Northumberland sent the bundle to ], who subsequently penned a thesis on the subject, with which was published a facsimile of the aforementioned cover. Spedding hazarded a 1592 date, making it possibly the earliest extant mention of Shakespeare. | ||

| After a diligent deciphering of the Elizabethan handwriting in Francis Bacon's |

After a diligent deciphering of the Elizabethan handwriting in Francis Bacon's notebook, known as the ''Promus of Formularies and Elegancies'', Constance Mary Fearon Pott (1833–1915) argued that many of the ideas and figures of speech in Bacon's book could also be found in the Shakespeare plays. Pott founded the Francis Bacon Society in 1885 and published her Bacon-centered theory in 1891.<ref>Pott, Constance: ''Francis Bacon and His Secret Society'' (London, Sampson, Low and Marston: 1891); .</ref> In this, Pott developed the view of W.F.C. Wigston,<ref>Wigston, W.F.C.: ''Bacon, Shakespeare and the Rosicrucians'' (1890).</ref> that Francis Bacon was the founding member of the ], a ] of ] philosophers, and claimed that they secretly created art, literature and drama, including the entire Shakespeare canon, before adding the symbols of the rose and cross rug to their work. ] also popularised the notion of Bacon's authorship. | ||

| Other Baconians ignored the esoteric following that the theory was attracting.<ref>Michell, John: ''Who Wrote Shakespeare'' (Thames and Hudson: 2000) pp. 258–59.</ref> Bacon's reason for publishing under a pseudonym was said to be his need to secure his high office, possibly in order to complete his "Great Instauration" project to reform the moral and intellectual culture of the nation. The argument is that Bacon intended to set up new institutes of experimentation to gather the data to which his inductive method could be applied. He needed high office to gain the requisite influence,<ref>]: "Of the Interpretation of Nature" in ''Life and Letters of Francis Bacon'', 1872). Bacon writes, "I hoped that, if I rose to any place of honour in the state, I should have a larger command of industry and ability to help me in my work ."</ref> and being known as a dramatist, an allegedly low-class profession, would have impeded his prospects (see ]). Realising that play-acting was used by the ancients "as a means of educating men's minds to virtue",<ref>Bacon, Francis: ''Advancement of Learning'' (1640), Book 2, p. xiii.</ref> and being "strongly addicted to the theatre"<ref>Pott; Pott: ''Did Francis Bacon Write "Shakespeare"?'', p. 7.</ref> himself, he is claimed to have set out the otherwise-unpublished moral philosophical component of his Great Instauration project in the Shakespearean oeuvre. In this way, he could influence the nobility through dramatic performance with his observations on what constitutes "good" government. | |||

| The late 19th-century interest in the Baconian theory continued the theme that Bacon had secreted encoded messages in the plays. In 1888, ], a U.S. ], science fiction author and ] theorist, set out his notion of ciphers in | |||

| ''The Great Cryptogram'', while ], having read Bacon's account of his ']' (in which two ]s were used as a method of encoding in binary format), claimed to have found evidence that Bacon not only authored the Shakespearean works but, along with the ], he was a child of ] and the ], who had been secretly married. No-one else was able to discern these hidden messages, and the cryptographers ] and ] showed that the method is unlikely to have been employed.<ref>Friedman, William and Friedman, Elizabeth: ''The Shakespearian ciphers examined'' (], 1957).</ref> | |||

| By the end of the 19th century, Baconian theory had received support from a number of high-profile individuals. ] showed an inclination for it in his essay '']''. ] expressed interest in and gave credence to the Baconian theory in his writings.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.sirbacon.org/nietzsche.htm | title = Bacon (Shakespeare) and Friedrich Nietzsche}}</ref> The German mathematician ] believed that Shakespeare was Bacon. He eventually published two pamphlets supporting the theory in 1896 and 1897.<ref>Dauben, Joseph W. (1979), Georg Cantor: his mathematics and philosophy of the infinite, Boston: Harvard University Press, pp. 281–83.</ref> By 1900, leading Baconians were asserting that their cause would soon be won. In 1916 a judge in Chicago ruled in a civil trial that Bacon was the true author of the Shakespeare canon.<ref>{{cite book |last=Wadsworth |first=Frank W. |author-link=Frank W. Wadsworth |title=The Poacher from Stratford: A Partial Account of the Controversy Over the Authorship of Shakespeare's Plays |year=1958 |publisher=University of California Press |url=https://archive.org/details/poacherfromstrat00wads |url-access=registration }}</ref> However, this proved to be the heyday of the theory. A number of new candidates were proposed in the early 20th century, notably ], ] and ], dethroning Bacon as the sole alternative to Shakespeare. Furthermore, these and other alternative authorship theories failed to make any headway among academics. | |||

| ] (1844–1900) expressed interest in and gave credence to the Baconian theory in his writings. The German mathematician ] believed that Shakespeare was Bacon, but he was apparently suffering a bout of illness when he researched the subject in 1884. He eventually published two pamphlets supporting the theory in 1896 and 1897. | |||

| ===Baconian cryptology=== | |||

| The American physician Dr ] (1854–1924) had such conviction in his own cipher method that, in 1909, he began excavating the bed of the ], near ], in the search of Bacon's original Shakespearean manuscripts. The project, as-yet unsuccessful, ended with his death in 1924. | |||

| In 1880 ], a U.S. ], ] author and ] theorist, wrote ''The Great Cryptogram'', in which he argued that Bacon revealed his authorship of the works by concealing secret ciphers in the text. This produced a plethora of late 19th-century Baconian theorising, which developed the theme that Bacon had hidden encoded messages in the plays. | |||

| Baconian theory developed a new twist in the writings of ] and ]. Owen's book ''Sir Francis Bacon's Cipher Story'' (1893–95) claimed to have discovered a secret history of the Elizabethan era hidden in cipher-form in Bacon/Shakespeare's works. The most remarkable revelation was that Bacon was the son of ]. According to Owen, Bacon revealed that Elizabeth was secretly married to ], who fathered both Bacon himself and ], the latter ruthlessly executed by his own mother in 1601.<ref name = "shakliz">Helen Hackett, ''Shakespeare and Elizabeth: the meeting of two myths'', Princeton University Press, 2009, pp. 157–60</ref> Bacon was the true heir to the throne of England, but had been excluded from his rightful place. This tragic life-story was the secret hidden in the plays. | |||

| The American art collector ] (1878–1954) believed that Bacon had concealed messages in a variety of ciphers, relating to a secret history of the time and the esoteric secrets of the Rosicrucians, in the Shakespearean works. He published a variety of decipherments between 1922 and 1930, concluding finally that, although he had failed to find them, there certainly were concealed messages. He established the Francis Bacon Foundation in California in 1937 and left it his collection of Baconiana. | |||

| ]'' on the 1916 trial of Shakespeare's authorship. From left: George Fabyan; Judge Tuthill; Shakespeare and Bacon; ].]] | |||

| More recent Baconian theory ignores the esoteric following that the theory had earlier attracted.<ref>Michell, John: ''Who Wrote Shakespeare'' (Thames and Hudson: 2000) pp. 258-259.</ref> Whereas, previously, the main proposed reason for secrecy was Bacon's desire for high office, this theory posits that his main motivation for concealment was the completion of his Great Instauration project.<ref>Spedding, James: ''The Works of Francis Bacon'' (1872), Vol.4, p.112 (Bacon comments on whether his idea of compiling Histories (some of which he wrote up himself for the natural sciences) and then applying his inductive method to them, should only apply to natural science or whether Histories were also required for ethics and politics: "It may be asked whether I speak of natural philosophy only, or whether I mean that the other sciences, logic, ethics, and politics, should be carried on by this method. Now I certainly mean what I have said to be understood of them all ."</ref><ref>Dean, Leonard: ''Sir Francis Bacon's theory of civil history writing'', in Vickers, Brian, (ed.): ''Essential Articles for the Study of Sir Francis Bacon'' (Sidwick & Jackson: 1972), p. 219: "Bacon believed that the chief functions of history are to provide the materials for a realistic treatment of psychology and ethics, and to give instruction by means of example and analysis in practical politics."</ref> The argument runs that, in order to advance the project's scientific component, he intended to set up new institutes of experimentation to gather the data (his scientific "Histories") to which his inductive method could be applied. He needed to attain high office, however, to gain the requisite influence,<ref>]: "Of the Interpretation of Nature" in ''Life and Letters of Francis Bacon'', 1872). Bacon writes, "I hoped that, if I rose to any place of honour in the state, I should have a larger command of industry and ability to help me in my work ."</ref> and being known as a dramatist (a low-class profession) would have impeded his prospects. Realising that play-acting was used by the ancients "as a means of educating men's minds to virtue",<ref>Bacon, Francis: ''Advancement of Learning'' (1640), Book 2, p. xiii.</ref> and being "strongly addicted to the theatre"<ref>Pott; Pott: ''Did Francis Bacon Write "Shakespeare"?'', p. 7.</ref> himself, he is claimed to have set out the otherwise-unpublished moral philosophical component of his Great Instauration project in the Shakespearean work (moral "Histories"). In this way, he could influence the nobility through dramatic performance with his observations on what constitutes "good" government (as in Prince Hal's relationship with the Chief Justice in '']''). | |||

| ] developed Owen's views, arguing that a ], which she had identified in the ] of Shakespeare's works, revealed concealed messages confirming that Bacon was the queen's son. This argument was taken up by several other writers, notably Alfred Dodd in ''Francis Bacon’s Personal Life Story'' (1910) and C.Y.C. Dawbarn in ''Uncrowned'' (1913).<ref name = "shakliz"/><ref name = "kil">Michael Dobson & Nicola J. Watson, ''England's Elizabeth: An Afterlife in Fame and Fantasy'', Oxford University Press, New York, 2004, p. 136.</ref> In Dodd's account Bacon was a national redeemer, who, deprived of his ordained public role as monarch, instead performed a spiritual transformation of the nation in private though his work: "He was born for England, to set the land he loved on new lines, 'to be a Servant to Posterity'".<ref>Alfred Dodd, ''Francis Bacon's Personal Life Story'', London: Rider, 1950, preface.</ref> In 1916 Gallup's financial backer ] was sued by film producer ]. He argued that Fabyan's advocacy of Bacon threatened the profits expected from a forthcoming film about Shakespeare. The judge determined that ciphers identified by Gallup proved that Francis Bacon was the author of the Shakespeare canon, awarding Fabyan $5,000 in damages. | |||

| Orville Ward Owen had such conviction of his own cipher method that, in 1909, he began excavating the bed of the ], near ], in the search of Bacon's original Shakespearean manuscripts. The project ended with his death in 1924. Nothing was found. | |||

| ==Autobiographical evidence== | |||

| It is known that, as early as 1595, Bacon employed scriveners,<ref>Lambeth Palace MS 650.28, written in Bacon's hand to his brother Anthony: "I have here an idle pen or two thinking to have got some money this term; I pray send me somewhat else for them to write .') Some scholars believe that Anthony and others contributed to the composition of the Shakespearean plays, too, "content to see their work performed and preserved without the beggarly ambition of advertising their names on the title pages". See Caldecott: ''Our English ]'', pp. 10-11.</ref> which, one could argue, would protect his anonymity and account for ] and ], two actors in Shakspeare's company, remarking about Shakspere that "wee have scarce received from him a blot in his papers".<ref>Heminge, John; Condell, Henry: '']'' (1623), dedication "To the great variety of Readers".</ref> Baconians point out that Bacon's rise to the post of Attorney General in 1613 coincided with the end of Shakespeare the author's output. They also stress that he was the only authorship candidate still alive when the First Folio was published and that it occurred in a period (1621–1626) when Bacon was publishing his work for posterity after his fall from office gave him the free time. | |||

| The American art collector ] (1878–1954) believed that Bacon had concealed messages in a variety of ciphers, relating to a secret history of the time and the esoteric secrets of the Rosicrucians, in the Shakespearean works. He published a variety of decipherments between 1922 and 1930, concluding finally that, although he had failed to find them, there certainly were concealed messages. He established the Francis Bacon Foundation in California in 1937 and left it his collection of Baconiana. | |||

| '']'' (1613) may be interpreted as alluding to Bacon's fall from office in 1621, suggesting that the play had been altered at least five years after Shakspere's death in 1616. The argument relates to ]'s forfeiture of the ] in the play, which might be construed as departing from the facts of history to mirror Bacon's own loss. Bacon lost office on a charge of accepting bribes to influence his judgment of legal cases, whereas Wolsey's crime was to petition the Pope to delay sanctioning King Henry's divorce from ]. Nevertheless, in 3.2.125-8, just before the Great Seal is reclaimed, King Henry's main concern is an inventory of Wolsey's wealth that has inadvertently been delivered to him: | |||

| :::''King Henry''. The several parcels of his Plate, his Treasure, | |||

| :::Rich stuffs, and ornaments of household, which | |||

| :::I find at such a proud rate, that it outspeaks | |||

| :::Possession of a subject. | |||

| In 1957 the expert cryptographers ] and ] published ''The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined'', a study of all the proposed ciphers identified by Baconians (and others) up to that point. The Friedmans had worked with Gallup. They showed that the method is unlikely to have been employed by the author of Shakespeare's works, concluding that none of the ciphers claimed to exist by Baconians were valid.<ref>Friedman, William F. and Friedman, Elizebeth: ''The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined'', ], 1957.</ref> | |||

| A few lines later, Wolsey loses the Seal with the stage direction: | |||

| :::Enter to Cardinal Wolsey the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk, the Earl of Surrey | |||

| :::and the Lord Chamberlaine. | |||

| However, in history, only the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk performed this task,<ref>Holinshed, Raphael, ''The Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland'' (1587), pp. 796-7: "the king sent the two dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk to the cardinal's place at Westminster that he should surrender up the greate seal into their hands".</ref> and Shakespeare has inexplicably added the Earl of Surrey and the Lord Chamberlaine. In Bacon's case, King James "commissioned the Lord Treasurer, the Lord Steward, the Lord Chamberlaine, and the Earl of Arundel, to receive and take charge of it".<ref>Spedding, James, ''Life and Letters of Francis Bacon'' (1872), Vol. 7, p. 262.</ref> Given that ] was the 2nd Earl of Arundel and Surrey, then the two noblemen that Shakespeare has added may be construed as references to two of the four that attended Bacon. | |||

| ==Credentials for authorship== | ==Credentials for authorship== | ||

| Early Baconians were influenced by Victorian ], which portrayed Shakespeare as a profound intellectual, "the greatest intellect who, in our recorded world, has left record of himself in the way of Literature", as ] stated.<ref>Sawyer, Robert (2003). ''Victorian Appropriations of Shakespeare''. New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 113. {{ISBN|0-8386-3970-4}}.</ref><ref>] (1840). "On Heroes, Hero Worship & the Heroic in History". Quoted in Smith, Emma (2004). ''Shakespeare's Tragedies''. Oxford: Blackwell, 37. {{ISBN|0-631-22010-0}}.</ref> In conformity with these ideas, Baconian writer Harry Stratford Caldecott held that the Shakespearean work was of such an incalculably higher calibre than that of contemporary playwrights that it could not possibly have been written by any of them. Even mainstream Shakespearean scholar ], wrote that "Had the plays come down to us anonymously – had the labour of discovering the author been imposed upon future generations – we could have found no one of that day but Francis Bacon to whom to assign the crown. In this case it would have been resting now upon his head by almost common consent."<ref>Quoted in Morgan: ''The Shakespearean Myth'', p. 201.</ref> "He was," agreed Caldecott, "all the things that the plays of Shakespeare demand that the author should be – a man of vast and boundless ambition and attainments, a philosopher, a poet, a lawyer, a statesman."<ref>Caldecott: ''Our English Homer'', pp. 11–12.</ref> | |||

| There is indeed much evidence to suggest that Bacon had the credentials to write the Shakespearean work.{{citation needed|date=October 2010}} In relation to the Stratford man's extensive vocabulary, we have the words of ], author of the first dictionary: " Dictionary of the English language might be compiled from Bacon's writing alone".<ref>Boswell, James: ''The Life of Samuel Johnson 1740-1795'', Chapter 13.</ref> The poet ] testifies against the notion that Bacon's was an unwaveringly dry legal style: "Lord Bacon was a poet. His language has a sweet majestic rhythm, which satisfies the sense, no less than the almost superhuman wisdom of his intellect satisfies the intellect ."<ref>Shelly, Percy Bysse: ''Defense of Poetry'' (1821), p. 10.</ref> ] writes in his First-Folio tribute to "The Author Mr William Shakespeare", | |||

| ::Leave thee alone for the comparison | |||

| ::Of all that insolent Greece and haughtie Rome | |||

| ::Sent forth, or since did from their ashes come. | |||

| "There can be no doubt," said Caldecott, "that Ben Jonson was in possession of the secret composition of Shakespeare's works." An intimate of both Bacon and Shakespeare – he was for a time the former's stenographer and Latin interpreter, and had his ] as a playwright produced by the latter<ref>Jonson's familiarity with Shakespeare is further evidenced in his communication with Drummond of Hawthornden.</ref> – he was placed perfectly to be in the know. He did not name Shakespeare among the sixteen greatest cards of the epoch but wrote of Bacon that he "hath filled up all the numbers,<ref>Verses.</ref> and performed that in our tongue which may be compared or preferred either to insolent Greece or to haughty Rome so that he may be named, and stand as the mark<ref>Target.</ref> and ''acme'' of our language."<ref>Jonson, Ben: ''Timber: or, Discoveries; Made Upon Men and Matter'' (Cassell: 1889), pp. 60-61. (Definitions: ''number'' (n.) 1. (plural) verses, lines, e.g. "These numbers will I tear and write in prose", ''Hamlet'' II, ii, 119; ''mark'' (n.) 1. target, goal, aim, e.g. "that's the golden mark I seek to hit" (''Henry VI, Part 2'', I, i, 241). Source: Crystal, David; Crystal, Ben: ''Shakespeare's Words'' (], 2002).</ref> "If Ben Jonson knew that the name 'Shakespeare' was a mere cloak for Bacon, it is easy enough to reconcile the application of the same language indifferently to one and the other. Otherwise," declared Caldecott, "it is not easily explicable."<ref>Caldecott: ''Our English Homer'', p. 15.</ref> | |||

| Some time subsequent to Shakespeare's expiry, Jonson tackled the panoptic task of setting down the ] and casting away the originals. This was in 1623, when Bacon had lapsed into penury. Jonson would have been keen to allay his friend's straits, and the folio's yield would have fitted the bill nicely. | |||

| In 1645, there was printed a strange volume entitled ''The Great Assizes Holden in ] by Apollo and his Assessours''. Atop the mountain sat ] and, immediately beneath him, Bacon ("The Lord Verulam, Chancellor of Parnassus"), followed by 25 writers and poets, and then, second last at number 26 (and only as a "juror"), "William Shakespere". This artefact has frequently been interpreted as suggesting that Francis Bacon was miles ahead of his coevals and second only to Apollo in the poetical stakes.{{Citation needed|date=October 2010}} | |||

| Baconians have also argued that Shakespeare's works show a detailed scientific knowledge that, they claim, only Bacon could have possessed. Certain passages in '']'', first published in 1623, are alleged to refer to the ], a theory known to Bacon through his friendship with ], but not made public until after Shakespeare's death in 1616.<ref>James Phinney Baxter, ''The Greatest of Literary Problems: The Authorship of the Shakespeare Works: An Exposition of All the Points at Issue, from Their Inception to the Present Moment'', Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1917, p. 28.</ref> They also argue that Bacon has been praised for his poetic style, even in his prose works.<ref>In relation to the extensive vocabulary used in the plays, we have the words of ], " Dictionary of the English language might be compiled from Bacon's writing alone". Boswell, James: ''The Life of Samuel Johnson 1740–1795'', Chapter 13. The poet ] testifies against the notion that Bacon's was an unwaveringly dry legal style: "Lord Bacon was a poet. His language has a sweet majestic rhythm, which satisfies the sense, no less than the almost superhuman wisdom of his intellect satisfies the intellect ." Shelley, Percy Bysshe: ''Defense of Poetry'' (1821), p. 10.</ref> | |||

| That Bacon took a keen interest in civil history is evidenced in his book ''History of the Reign of ]'' (1621), his article the ''Memorial of Elizabeth'' (1608) and his letter to ] in 1610, lobbying for financial support to indite a history of Great Britain: "I shall have the advantage which almost no writer of history hath had, in that I shall write of times not only since I could remember, but since I could observe."<ref>Spedding, James: ''The Works of Francis Bacon'' (1872), Vol. 6, p. 274.</ref> | |||

| Opponents of this view argue that Shakespeare's erudition was greatly exaggerated by Victorian enthusiasts, and that the works display the typical knowledge of a man with a grammar school education of the time. His Latin is derived from school books of the era.<ref>Baldwin, T. W. (1944). William Shakespere's Small Latine & Lesse Greeke. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.</ref> There is no record that any contemporary of Shakespeare referred to him as a learned writer or scholar. Ben Jonson and Francis Beaumont both refer to his ''lack'' of classical learning.<ref>{{Harvnb|McCrea|2005|pp=64, 171}}; {{Harvnb|Bate|1998|p=70}}.</ref> If a university-trained playwright wrote the plays, it is hard to explain the many ] blunders in Shakespeare. Not only does he mistake the ] of many classical names, in '']'' he has Greeks and Trojans citing ] and ] a thousand years before their births.<ref>{{Harvnb|Lang|2008|pp=36–37}}.</ref> Willinsky suggests that most of Shakespeare's classical allusions were drawn from ] ''Thesaurus Linguae Romanae et Britannicae'' (1565), since a number of errors in that work are replicated in several of Shakespeare’s plays,<ref>{{Harvnb|Willinsky|1994|p=75}}.</ref> and a copy of this book had been bequeathed to Stratford Grammar School by John Bretchgirdle for "the common use of scholars".<ref>{{Harvnb|Velz|2000|p=188}}.</ref> | |||

| Bacon and Shake-speare cover completely the monarchs of the period 1377 to 1603 without duplicating one another's historical ground. In 1623, Bacon gave different excuses to ] for not working on a commissioned treatise on Henry VIII (which had already been covered by the Shake-speare play in 1613).<ref>Spedding, James: ''The Works of Francis Bacon'' (1872), Vol. 6, p. 267. In a letter to his friend ], dated 16 June 1623, Bacon writes, "Since you say the Prince hath not forgotten his commandment touching my history of Henry the Eighth, I may not forget my duty. But I find ], who poured forth what he had in my former work, somewhat dainty in his materials in this". In a letter to Prince Charles in late October 1623, he continues, "For Henry the Eighth, to deal truly with your Highness, I did so despair of my health this summer, as I was glad to choose some such work as I might encompass within days: so far was I from entering into a work of any length".</ref> In the end, he wrote only two pages. | |||

| In addition, it is argued that Bacon's and Shakespeare's styles of writing are profoundly different, and that they use very different vocabulary.<ref name = "mac">{{cite book |last1=McCrea |first1=Scott |title=The Case for Shakespeare: The End of the Authorship Question |date=2005 |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-275-98527-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=c95vhdF1qiYC |page=136 ff}}</ref> Scott McCrea writes, "there is no answer for Bacon's different renderings of the same word – 'politiques' instead of 'politicians', or 'submiss' instead of the Author's 'submissive', or 'militar' instead of the Poet's 'military'. These are two different writers."<ref name = "mac"/> | |||

| ==The Tempest== | |||

| {{Refimprovesect}} | |||

| Numerous scholars{{Who}} believe that the main source for Shake-speare's '']'' was a letter written by ] known as the ''True Reportory (TR)''<ref>Purchas, Samuel, ''Hakluytus posthumus; or, Purchas his pilgrimes'', (William Stansby, London: 1625), p.1758; in four volumes, beginning page 1734 in vol. IV. Published as ''Purchas His Pilgrimes'', Vol. 19 (James MacLehose and Sons: 1904). Includes extracts from the ''True Declaration''</ref> sent back to the Virginia Company from the newly established Virginia colony in 1610, about a year before the play's first known performance.<ref>Vaughan, V.M., and Vaughan A.T., ''The Tempest'', Arden Shakespeare (Thomson Learning: 1999), pp.41</ref> It was discovered when ], one of the eight names on the First Virginia Charter (1606), died in 1616 and a copy was found among his papers. Scholars have suggested that the letter was “circulated in manuscript”<ref>Dobson, Michael, and Wells, Stanley, ''The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare'' (Oxford University Press: 2005), p.470</ref> without restriction and that “there seems to have been an opportunity for Shakespeare to see the unpublished report, or even to have met Strachey”.<ref>Kermode, F. (ed.), ''The Tempest'', Arden Shakespeare (London, Methuen: 1958), p. xxviii</ref> However, Baconians point to evidence that the letter was restricted to members of the Virginia Council which included ] (and 50 other Lords and Earls) but not William Shakspere. For example, Item 27 of the governing Council’s instructions to Deputy Governor ] before he set out for the colony charges him to “take especial care what relacions come into England and what lettres are written and that all thinges of that nature may be boxed up and sealed and sent to first of the Council here, ... and that at the arrivall and retourne of every shippinge you endeavour to knowe all the particular passages and informacions given on both sides and to advise us accordingly."<ref>Swem, E.G., (Ed.), “The Three Charters of the Virginia Company of London”, in ''Jamestown 30th Anniversary Historical Booklets 1–4'' (Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration Corporation: 1957), p.66</ref> Louis B. Wright explains why the ] was so keen to control information: “ a discouraging picture of Jamestown, but it is significant that it had to wait fifteen years to see print, for the ] just at that time was subsidising preachers and others to give glowing descriptions of Virginia and its prospects".<ref>Wright, Louis B., ''The Cultural Life of the American Colonies'' (Courier Dover Publications: 2002), p.156</ref> Baconians argue that it would have been against the interests of any Council member, whose investment was at risk, to present a copy of the ''TR'' to Shakspere, whose business was public. | |||

| ==Alleged coded references to Bacon's authorship== | |||

| On November 1610, conscious that the criticisms of the returning colonists might jeopardise the recruitment of new settlers and investment, the ] published the propagandist ''True Declaration (TD)'' which was designed to confute “such scandalous reports as have tended to the disgrace of so worthy an enterprise” and was intended to “wash away those spots, which foul mouths (to justify their own disloyalty) have cast upon so fruitful, so fertile, and so excellent a country”.<ref>''A True Declaration of the estate of the Colony in Virginia, with a confutation of such scandalous reports as have tended to the disgrace of so worthy an enterprise.'' Published by advice and direction of the Council of Virginia, London. Printed for William Barret, and are to be sold at the Black Bear in Paul’s Church yard, 1610.</ref> The ''TD'' relied on the ''TR'' and other minor sources and it is clear from its use of “I” that it had a single author. There are also verbal parallels between (a) the ''TD'', and (b) Bacon's ''Advancement of Learning''<ref>Bacon, Francis, ''The Major Works'' (Oxford University Press: 2002)</ref> that suggest that ] as Solicitor General might have written the ''TD'' and so, by implication, had access to the ''TR'' which sourced '']''. Some examples of these are presented together with their correspondence to (c) the Shake-speare work. | |||

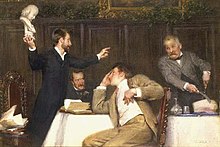

| ]. Baconians have argued that this depicts Bacon writing the plays (bottom panel), giving them to a middle man, who passes them to Shakespeare (the man holding a spear in the middle-left panel)]] | |||

| Baconians have claimed that some contemporaries of Bacon and Shakespeare were in on the secret of Bacon's authorship, and have left hints of this in their writings. "There can be no doubt," said Caldecott, "that Ben Jonson was in possession of the secret composition of Shakespeare's works." An intimate of both Bacon and Shakespeare – he was for a time the former's stenographer and Latin interpreter, and had his ] as a playwright produced by the latter – he was placed perfectly to be in the know. He did not name Shakespeare among the sixteen greatest cards of the epoch but wrote of Bacon that he "hath filled up all the numbers and performed that in our tongue which may be compared or preferred either to insolent Greece and haughty Rome so that he may be named, and stand as the mark and ''acme'' of our language."<ref>Jonson, Ben: ''Timber: or, Discoveries; Made Upon Men and Matter'' (Cassell: 1889), pp. 60–61. (Definitions: ''number'' (n.) 1. (plural) verses, lines, e.g. "These numbers will I tear and write in prose", ''Hamlet'' II, ii, 119; ''mark'' (n.) 1. target, goal, aim, e.g. "that's the golden mark I seek to hit" (''Henry VI, Part 2'', I, i, 241). Source: Crystal, David; Crystal, Ben: ''Shakespeare's Words'' (], 2002).</ref> Jonson's First-Folio tribute to "The Author Mr William Shakespeare", contains the same words, stating that Shakespeare is as good as "all that insolent Greece or haughty Rome" produced. According to Caldecott, "If Ben Jonson knew that the name 'Shakespeare' was a mere cloak for Bacon, it is easy enough to reconcile the application of the same language indifferently to one and the other. Otherwise," declared Caldecott, "it is not easily explicable.".<ref>Caldecott: ''Our English Homer'', p. 15.</ref> | |||

| Baconians Walter Begley and Bertram G. Theobald claimed that Elizabethan satirists ] and ] alluded to ] as the true author of '']'' and '']'' by using the sobriquet "Labeo" in a series of poems published in 1597–98. They take this to be a coded reference to Bacon on the grounds that the name derives from Rome's most famous legal scholar, ], with Bacon holding an equivalent position in ]. Hall denigrates several poems by Labeo and states that he passes off criticism to "shift it to another's name". This is taken to imply that he published under a pseudonym. In the following year Marston used Bacon's Latin motto in a poem and seems to quote from ''Venus and Adonis'', which he attributes to Labeo.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gibson|2005|pp=59–65}}; {{Harvnb|Michell|1996|pp=126–29|}}.</ref> Theobald argued that this confirmed that Hall's Labeo was known to be Bacon and that he wrote ''Venus and Adonis''. Critics of this view argue that the name Labeo derives from ], a notoriously bad poet, and that Hall's Labeo could refer to one of many poets of the time, or even be a composite figure, standing for the triumph of bad verse.<ref name = "mac"/><ref>A Davenport, ''The Poems of Joseph Hall'', Liverpool University Press, 1949.</ref> Also, Marston's use of the Latin motto is a different poem from the one which alludes to ''Venus and Adonis''. Only the latter uses the name Labeo, so there is no link between Labeo and Bacon.<ref name = "mac"/> | |||

| '''Parallel 1''' | |||

| :(a) The next Fountaine of woes was secure negligence | |||

| :(b) but to drink indeed of the true fountains of learning (p.121) | |||

| :(c) ''Thersites''. Would the fountain of your mind were clear again, | |||

| ::that I might water an ass at it! | |||

| ::(1602-3 ''Troilus and Cressida'', 3.3.305-6) | |||

| '''Parallel 2''' | |||

| :(a) For if the country be barren or the situation contagious as famine | |||

| ::and sickness destroy our nation, we strive against the stream of reason | |||

| ::and make ourselves the subjects of scorn and derision. | |||

| :(b) whereby divinity hath been reduced into an art, as into a cistern, and | |||

| ::the streams of doctrine or positions fetched and derived from thence. (p.293) | |||

| :(c) ''Timon''. Creep in the minds and marrows of our youth, | |||

| ::That 'gainst the stream of virtue they may strive, | |||

| ::And drown themselves in riot! | |||

| ::(1604-7 ''Timon of Athens'', 4.1.26-8) | |||

| ::''Lysander''. scorn and derision never come in tears: | |||

| ::(1594-5 ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'', 3.2.123) | |||

| '''Parallel 3''' | |||

| :(a) The emulation of Cæsar and Pompey watered the plains of Pharsaly | |||

| ::with blood and distracted the sinews of the Roman monarchy. | |||

| :(b) We will begin, therefore, with this precept, according to the ancient | |||

| ::opinion, that the sinews of wisdom are slowness of belief and distrust (p.273) | |||

| :(c) ''Henry V''. Now are we well resolved; and, by God's help, | |||

| ::And yours, the noble sinews of our power, | |||

| ::France being ours, we'll bend it to our awe, | |||

| ::Or break it all to pieces: | |||

| ::(1599 ''Henry V'', 1.2.222-5) | |||

| In 1645 a satirical poem (often attributed to ]) was published entitled ''The Great Assizes Holden in ] by Apollo and his Assessours''. This describes an imaginary trial of recent writers for crimes against literature. ] presides at a trial. Bacon ("The Lord Verulam, Chancellor of Parnassus") heads a group of scholars who act as the judges. The jury comprises poets and playwrights, including "William Shakespeere". One of the convicted "criminals" challenges the court, attacking the credentials of the jury, including Shakespeare, who is called a mere "mimic". Despite the fact that Bacon and Shakespeare appear as different individuals, Baconians have argued that this is a coded assertion of Bacon's authorship of the canon, or at least proof that he was recognised as a poet.<ref>Baxter, James, ''The Greatest of Literary Problems'', Houghton, 1917, pp. 389–91.</ref> | |||

| ] went on to write ''The History of Travel into Virginia Britannica'', a book that avoided duplicating the details of the ''TR''. First published in 1849, three manuscript copies survive dedicated to Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland; Sir William Apsley, Purveyor of his Majesty’s Navy Royal; and ], Lord Chancellor. In the dedication to Bacon, which must have been composed after he became Lord Chancellor in 1618, Strachey writes “Your Lordship ever approving himself a most noble fautor of the Virginia Plantation, being from the beginning (with other lords and earls) of the principal counsel applied to propagate and guide it”.<ref>"A True Declaration of the state of the Colony in Virginia with a confutation of such scandalous reports as have tended to the disgrace of so worthy an enterprise" in Wright, Louis B., ''A Voyage to Virginia 1609'' (University Press of Virginia: 1904), p.xvii</ref> | |||

| Various images, especially in the frontispieces or title pages of books, have been said to contain symbolism pointing to Bacon's authorship. A book on codes and cyphers entitled ''Cryptomenytices et Cryptographiae'', is said to depict Bacon writing a work and Shakespeare (signified by the spear he carries) receiving it. Other books with similar alleged coded imagery include the third edition of ]'s translation of Montaigne, and various editions of works by Bacon himself.<ref>R. C. Churchill, ''Shakespeare and His Betters: A History and a Criticism of the Attempts Which Have Been Made to Prove That Shakespeare's Works Were Written by Others'', Max Reinhardt, London, 1938, p. 29</ref> | |||

| The 1610-11 dating of ''The Tempest'' however, has been challenged by a number of scholars, most recently by researchers Roger Stritmatter and Lynne Kositsky<ref>Shakespeare and the Voyagers Revisited, Stritmatter and Kositsky Review of English Studies, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2007; 58, </ref> who argue that Strachey's narrative could not have furnished an inspiration for Shakespeare, claiming that Strachey's letter was not put into its extant form until after ''The Tempest'' had already been performed on 1 Nov. 1611. The notion of an early date for ''The Tempest'' has in fact a long history in Shakespearean scholarship, going back to 19th century scholars such as Hunter<ref>Hunter, Rev. Joseph, ''Disquisition on the Scene, Origin, Date & etc. of Shakespeare's Tempest''</ref> and Elze,<ref>Elze, Karl. "The Date of the Tempest" in ''Essays on Shakespeare,'' translated with the author's sanction by Dora L. Schmitz. London: Macmillan & Co., 1874</ref> who both critiqued the widespread belief that the play depended on the Strachey letter. However, the cogency of their work has been challenged by Vaughan<ref>Vaughan, A., "William Strachey's True Reportory and Shakespeare: A closer look at the evidence", ''Shakespeare Quarterly'', 59(2008), 245-73</ref> and Reedy<ref>Reedy, T., "Dating William Strachey's a True Reportory", ''Review of English Studies'', Advance access published 16 January 2010</ref> who reaffirm the Strachey letter's use a source for ''The Tempest''. | |||

| ==Gray's Inn revels |

==Gray's Inn revels 1594–95== | ||

| Gray's Inn law school traditionally held revels over |

Gray's Inn law school traditionally held revels over Easter 94 and '95, all performed plays were amateur productions.<ref>Chambers, E.K.: ''The Elizabethan Stage'' (Clarendon Press, 1945), Vols I–IV. ''Gordobuc'' was presented before the Queen at Whitehall on 12 January 1561, written and acted by members of the Inner Temple. Gray's Inn members were responsible for writing both ''Supposes'' and ''Jocasta'' five years later; ''Catiline'' was performed by 26 actors from Gray's Inn before ] on 16 January 1588, see British Library ] 55, No. iv )</ref> In his commentary on the ''Gesta Grayorum'', a contemporary account of the 1594–95 revels, Desmond Bland<ref>Bland, Desmond: ''Gesta Grayorum'' (]: 1968), pp. xxiv–xxv.</ref> informs us that they were "intended as a training ground in all the manners that are learned by nobility dancing, music, declamation, acting." ], the Victorian editor of Bacon's ''Works'', thought that Sir Francis Bacon was involved in the writing of this account.<ref>Spedding, James: ''The Life and Letters of Francis Bacon'' (1872), Vol. 1, p. 325: "his connexion with it, though sufficiently obvious, has never so far been pointed out".</ref> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The ''Gesta Grayorum''<ref>''Gesta Grayorum, The History |

The ''Gesta Grayorum''<ref>''Gesta Grayorum, The History of the High and Mighty Prince Henry'' (1688), printed by W. Canning in London, reprinted by ] (]: 1914)</ref> is a pamphlet of 68 pages first published in 1688. It informs us that '']'' received its first known performance at these revels at 21:00 on 28 December 1594 (]) when "a Comedy of Errors (like to ] his ]) was played by the Players ." Whoever the players were, there is evidence that Shakespeare and his company were not among them: according to the royal Chamber accounts, dated 15 March 1595 – see Figure<ref>], ], Pipe Office, Declared Accounts, E. 351/542, f.107v, p. 40: "To ], William Shakespeare, & ], seruants {{sic}} to the ] upon the Councelle's {{sic}} warrant dated at Whitehall xv. to Marcij {{sic}} 1595, for twoe severall comedies or enterludes shewed by them before her majestie {{sic}} in Christmas tyme laste {{sic}} past viz ] and Innocents Day .")</ref> – he and the Lord Chamberlain's Men were performing for the Queen at Greenwich on Innocents Day. ]<ref>Chambers, Edmund Kerchever: ''The Elizabethan Stage'', Vol. 1 (]: 1945), p. 225.</ref> informs us that "the Court performances were always at night, beginning about 10pm and ending at 1am", so their presence at both performances is highly unlikely; furthermore, the Gray's Inn Pension Book, which recorded all payments made by the Gray's Inn committee, exhibits no payment either to a dramatist or to professional company for this play.<ref>Fletcher, Reginald, (Ed.) ''The Gray's Inn Pension Book 1569–1669'', Vol. 1 (1901).</ref> Baconians interpret this as a suggestion that, following precedent, ''The Comedy of Errors'' was both written and performed by members of the Inns of Court as part of their participation in the Gray's Inn celebrations. One problem with this argument is that the ''Gesta Grayorum'' refers to the players as "a Company of base and common fellows",<ref>W.W. Greg (ed.): ''Gesta Grayorum'', p. 23.</ref> which would apply well to a professional theatre company, but not to law students. But, given the jovial tone of the ''Gesta'', and that the description occurred during a skit in which a "Sorcerer or Conjuror" was accused of causing "disorders with a play of errors or confusions", Baconians interpret it as merely a comic description of the Gray's Inn players. | ||

| Gray's Inn actually had a company of players during the revels. The Gray's Inn Pension Book records on 11 February 1595 that "one hyndred marks to be layd out & bestowyd upon the gentlemen for their sports and shewes this Shrovetyde at the court before the Queens Majestie ...."<ref>Fletcher, Reginald (ed.): ''The Gray's Inn Pension Book |

Gray's Inn actually had a company of players during the revels. The Gray's Inn Pension Book records on 11 February 1595 that "one hyndred marks to be layd out & bestowyd upon the gentlemen for their sports and shewes this Shrovetyde at the court before the Queens Majestie ...."<ref>Fletcher, Reginald (ed.): ''The Gray's Inn Pension Book 1569–1669'', Vol. 1 (London: 1901), p. 107.</ref> | ||

| ] There is, most importantly to the Baconians' argument, evidence that Bacon had control over the Gray's Inn players. In a letter either to ], dated before 1598, or to the Earl of Somerset in 1613,<ref>Spedding, James, ''Letters and Life of Francis Bacon'', Vol. II (New York: 1890), p.370; Vol. IV (New York: 1868), pp. |

] There is, most importantly to the Baconians' argument, evidence that Bacon had control over the Gray's Inn players. In a letter either to ], dated before 1598, or to the Earl of Somerset in 1613,<ref>Spedding, James, ''Letters and Life of Francis Bacon'', Vol. II (New York: 1890), p. 370; Vol. IV (New York: 1868), pp. 392–95</ref> he writes, "I am sorry the joint masque from the four Inns of Court faileth here are a dozen gentlemen of Gray's Inn that will be ready to furnish a masque".<ref>British Library, Lansdown MS 107, folio 8</ref>{{Verify source|date=December 2010}}{{Original research inline|date=July 2015}}<!---A more accessible version of this source is needed; has this letter been transcribed in a reliable publication?---> The dedication to a masque by ] performed at ] in 1613 describes Bacon as the "chief contriver" of its performances at Gray's Inn and the Inner Temple.<ref>Nichols, John: ''The Progresses, Processions, and Magnificent Festivities of King James the First'', Vol. II (AMS Press Inc, New York: 1828), pp. 589–92.</ref> He also appears to have been their treasurer prior to the 1594–95 revels.<ref>Fletcher, Reginald, (ed.): ''The Gray's Inn Pension Book'' 1569–1669, Vol. 1 (London: 1901), p. 101.</ref> | ||

| The discrepancy surrounding the whereabouts of the Chamberlain's Men is normally explained by theatre historians as an error in the Chamber Accounts. W.W. Greg suggested the following explanation: | The discrepancy surrounding the whereabouts of the Chamberlain's Men is normally explained by theatre historians as an error in the Chamber Accounts. ] suggested the following explanation: | ||

| :"he accounts of the Treasurer of the Chamber show payments to this company for performances before the Court on both 26 Dec. and |

:"he accounts of the Treasurer of the Chamber show payments to this company for performances before the Court on both 26 Dec. and 1 Jan. These accounts, however, also show a payment to the Lord Admiral's men in respect of 28 Dec. It is true that instances of two court performances on one night do occur elsewhere, but in view of the double difficulty involved, it is perhaps best to assume that in the Treasurer's accounts, 28 Dec. is an error for 27 Dec."<ref>W.W. Greg (ed.): ''Gesta Grayorum''. ] Reprints. Oxford University Press (1914), p. vi. This theory is echoed by ] (ed.) ''The Comedy of Errors'' (Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 3.</ref> | ||

| ==Verbal parallels== | ==Verbal parallels== | ||

| ===Gesta Grayorum=== | ===Gesta Grayorum=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The final paragraph of the ''Gesta Grayorum'' |

The final paragraph of the ''Gesta Grayorum'' – see Figure – uses a "greater lessens the smaller" construction that occurs in an exchange from the '']'' (1594–97), 5.1.92–97: | ||

| :::''Ner''. When the moon shone we did not see the candle | :::''Ner''. When the moon shone we did not see the candle | ||

| Line 148: | Line 88: | ||

| ::::Into the main of waters ... | ::::Into the main of waters ... | ||

| The ''Merchant of Venice'' uses both the same theme as the ''Gesta Grayorum'' (see Figure) and the same three examples to illustrate it |

The ''Merchant of Venice'' uses both the same theme as the ''Gesta Grayorum'' (see Figure) and the same three examples to illustrate it – a subject obscured by royalty, a small light overpowered by that of a heavenly body and a river diluted on reaching the sea. In an essay<ref>Spedding, James: ''A Brief Discourse tounching the Happy Union of the Kingdom of England and Scotland'' (1603), in ''The Life and Letters of Francis Bacon'' (1872), Vol. 3, p. 98.</ref> from 1603, Bacon makes further use of two of these examples: "The second condition is that the greater draws the less. So we see that when two lights do meet, the greater doth darken and drown the less. And when a small river runs into a greater, it loseth both the name and stream." A figure similar to "loseth both the name and stream" occurs in ''Hamlet'' (1600–01), 3.1.87–88: | ||

| :::''Hamlet''. With this regard their currents turn awry | :::''Hamlet''. With this regard their currents turn awry | ||

| :::::And lose the name of action. | :::::And lose the name of action. | ||

| Bacon was usually careful to cite his sources but does not mention Shakespeare once in any of his work. Baconians claim, furthermore, that, if the ''Gesta Grayorum'' was circulated prior to its publication in 1688 |

Bacon was usually careful to cite his sources but does not mention Shakespeare once in any of his work. Baconians claim, furthermore, that, if the ''Gesta Grayorum'' was circulated prior to its publication in 1688 – and no one seems to know if it was – it was probably only among members of the Inns of Court.{{Citation needed|date=October 2008}} | ||

| ===Promus=== | ===Promus=== | ||

| In the 19th century, a |

In the 19th century, a ] entitled the ''Promus of Formularies and Elegancies''<ref>] MS Harley 7017. A transcription can be found in Durning-Lawrence, Edward, ''Bacon is Shakespeare'' (Gay & Hancock, London 1910).</ref> was discovered. It contained 1,655 hand written ]s, ]s, ]s, ] and other miscellany. Although some entries appear original, many are drawn from the ] and ] writers ], ], ], ]; ]'s ''Proverbes'' (1562); ]'s ''Essays'' (1575), and various other French, Italian and Spanish sources. A section at the end aside, the writing was, by ]'s reckoning, in Bacon's hand; indeed, his signature appears on folio 115 verso. Only two folios of the notebook were dated, the third sheet 5 December 1594 and the 32nd 27 January 1595 (1596). Bacon supporters found similarities between a great number of specific phrases and aphorisms from the plays and those written by Bacon in the ''Promus''. In 1883 Mrs. Henry Pott edited Bacon's ''Promus'' and found 4,400 parallels of thought or expression between Shakespeare and Bacon. | ||

| ;Parallel 1 | |||

| :''Parolles''. So I say both of Galen and Paracelsus ( |

:''Parolles''. So I say both of Galen and Paracelsus (1603–05 ''All's Well That Ends Well'', 2.3.11) | ||

| :Galens compositions not Paracelsus separations (''Promus'', folio 84, verso) | :Galens compositions not Paracelsus separations (''Promus'', folio 84, verso) | ||

| ;Parallel 2 | |||

| :''Launce''. Then may I set the world on wheels, when she can spin for her living ( |

:''Launce''. Then may I set the world on wheels, when she can spin for her living (1589–93, ''The Two Gentlemen of Verona'', 3.1.307–08) | ||

| :Now toe on her distaff then she can spynne/The world runs on wheels (''Promus'', folio 96, verso) | :Now toe on her distaff then she can spynne/The world runs on wheels (''Promus'', folio 96, verso) | ||

| ;Parallel 3 | |||

| :''Hostesse''. O, that right should o'rcome might. Well of sufferance, comes ease (1598, ''Henry IV, Part 2'', 5.4. |

:''Hostesse''. O, that right should o'rcome might. Well of sufferance, comes ease (1598, ''Henry IV, Part 2'', 5.4.24–25) | ||

| :Might overcomes right/Of sufferance cometh ease (''Promus'', folio 103, recto) | :Might overcomes right/Of sufferance cometh ease (''Promus'', folio 103, recto) | ||

| Line 171: | Line 111: | ||

| ===Published work=== | ===Published work=== | ||

| There is an example in ''Troilus and Cressida'' (2.2.163) which shows that Bacon and Shakespeare shared the same interpretation of an ] view: | There is an example in '']'' (2.2.163) which shows that Bacon and Shakespeare shared the same interpretation of an ] view'':'' | ||

| ::''Hector''. Paris and Troilus, you have both said well, | ::''Hector''. Paris and Troilus, you have both said well, | ||

| Line 183: | Line 123: | ||

| Bacon's similar take reads thus: "Is not the opinion of Aristotle very wise and worthy to be regarded, 'that young men are no fit auditors of moral philosophy', because the boiling heat of their affections is not yet settled, nor tempered with time and experience?"<ref>Bacon, Francis: ''De Augmentis'', Book VII (1623).</ref> | Bacon's similar take reads thus: "Is not the opinion of Aristotle very wise and worthy to be regarded, 'that young men are no fit auditors of moral philosophy', because the boiling heat of their affections is not yet settled, nor tempered with time and experience?"<ref>Bacon, Francis: ''De Augmentis'', Book VII (1623).</ref> | ||

| What Aristotle actually said was slightly different: "Hence a young man is not a proper hearer of lectures on political science; and further since he tends to follow his passions his study will be vain and unprofitable ."<ref>Ross, W.D. (translator), ''Aristotle: |

What Aristotle actually said was slightly different: "Hence a young man is not a proper hearer of lectures on political science; and further since he tends to follow his passions his study will be vain and unprofitable ."<ref>Ross, W.D. (translator), ''Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics'', Book 1, iii (Clarendon Press, 1908). The translation "political science" is given by Griffith, Tom (ed.): ''Aristotle: The Nicomachean Ethics'' (Wordsworth Editions: 1996), p. 5.</ref> The added coincidence of heat and passion and the replacement of "political science" with "moral philosophy" is employed by both Shakespeare and Bacon. However, Shakespeare's play precedes Bacon's publication, allowing the possibility of the latter borrowing from the former. | ||

| ==Arguments against Baconian theory== | |||

| ==Raleigh's execution== | |||

| Mainstream academics reject the Baconian theory (along with other "alternative authorship" theories), citing a range of evidence – not least of all its reliance on a conspiracy theory. As far back as 1879, a '']'' scribe bemoaned the waste of "considerable blank ammunition in this ridiculous war between the Baconians and the Shakespearians",<ref>''New York Herald'' 1879.</ref> while ] made the common objection that Bacon was far too busy with his own work to have had time to create the entire canon of another writer too, declaring that "Baconians talk as if Bacon had nothing to do but to write his play at his chambers and send it to his factotum, Shakespeare, at the other end of the town."<ref>Garnett and Gosse 1904, p. 201.</ref> | |||

| Spedding suggests that lines in ''Macbeth'' refer to ]'s execution, which occurred two years after Shakespeare of Stratford's death and fourteen years after the ]'s.<ref>Spedding, James: ''Life and Letters of Francis Bacon'', Vol.6, p. 372.</ref> The lines in question are spoken by Malcolm about the execution of the "disloyall traytor / The Thane of Cawdor" (1.2.53)<!---Line references to a specific edition are needed as they can change from edition to edition--->: | |||

| ] wrote in a letter that, "Donnelly's theory about Bacon's authorship is too foolish to be seriously answered. I don't think he started it for any other purpose than notoriety. I believe he doesn't attempt to show that Bacon corrected the proof-sheets of the First Folio, and no human foresight could have told how the printed line would run, and have so regulated the MSS. To Donnelly's theory the pagination & the number of lines in a page are essential."<ref></ref> | |||

| ::''King''. Is execution done on Cawdor? | |||

| ::Or not those in Commission yet return'd? | |||

| ::''Malcolme''. My Liege, they are not yet come back, | |||

| ::But I have spoke with one that saw him die: | |||

| ::Who did report, that very frankly hee | |||

| ::Confess'd his Treasons, implor'd your Highnesse Pardon | |||

| ::And set forth a deepe Repentance: | |||

| ::Nothing in his Life became him, | |||

| ::Like the leaving it. He dy'de , | |||

| ::As one that had been studied in his death, | |||

| ::To throw away the dearest thing he ow'd, | |||

| ::As 'twere a carelesse Trifle.(1.4.1) | |||

| Mainstream academics reject the anti-Stratfordian claim<ref>that the author would have needed a keen understanding of foreign languages, modern sciences, warfare, aristocratic sports such as tennis, statesmanship, hunting, natural philosophy, history, falconry and the law to have written the plays ascribed to him. It is therefore significant, say Baconians,{{Who|date=November 2010}} that Bacon, in his 1592 letter to Burghley, claims to have "taken all knowledge to be province".</ref> that Shakespeare had not the education to write the plays. Shakespeare grew up in a family of some importance in Stratford; his father ], one of the wealthiest men in Stratford, was an ] and later ] of the corporation. It would be surprising had he not attended the local grammar school, as such institutions were founded to educate boys of Shakespeare's moderately well-to-do standing.<ref>T.W. Baldwin, "William Shakespeare's "Small Latin and Less Greek", University of Illinois Press, 1944.</ref> | |||

| Several sources have remarked upon Raleigh's frivolity in the face of his impending execution<ref>Williams, Norman Lloyd, ''Sir Walter Raleigh'' (Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1962), p. 254. The Dean of Westminster wrote to Sir John Isham, "when I began to encourage him against the fear of death, he seemed to make so light of it that I wondered at him .")</ref><ref>Spedding, James: ''Life and Letters of Francis Bacon'', Vol. 6, p. 373. Dudley Carelton wrote, "e knew better how to die than to live; and his happiest hours were those of his arraignment and execution."</ref> and the assertion that " are not yet come back" could refer to the fact that his execution was swift: it took place the day after his trial for treason.<ref>]: ''Annales, or Generall Chronicle of England'' (London, 1631), p. 1030.</ref> ], the main source for ''Macbeth'', mentions "the thane of Cawder being condemned at Fores of treason against the king"<ref>Holinshed, Raphael: ''Chronicles'', Vol. V: Scotland (1587 ), p. 170.</ref> without further details about his execution, so whoever wrote the lines in the play went beyond the original source. | |||

| Stratfordian scholars<ref>{{cite book|author-last=Hirsh|author-first=James|editor1-last=Cerasano|editor1-first=S.P.|editor2-last=Bly|editor2-first=Mary|editor3-last=Hirschfeld|editor3-first=Anne|title=Medieval and Renaissance Drama in England|volume=23|year=2010|page=51|publisher=Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press |quote=...Someone with a respect for evidence would not be satisfied with the hodgepodge of feeble rationalizations. Nor would someone with a respect for evidence be satisfied with a defense of the conventional assumption that dealt with only a few of the many pieces of inconvenient evidence catalogued here and that simply ignored the numerous remaining pieces. If ever a situation called for Occam's razor, this is it. If a single explanation accounts for many pieces of evidence, that explanation is more likely to be correct than a series of separate, ad hoc explanations, one for each piece of evidence, even if the alternative explanations for each individual piece of evidence are all equally credible.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=s-sud1EHxXEC&pg=PA51|isbn=9780838642696}}</ref> also cite ], the principle that the simplest and best-evidenced explanation (in this case that the plays were written by Shakespeare of Stratford) is most likely to be the correct one. A critique of all alternative authorship theories may be found in ]'s ''Shakespeare's Lives''.<ref name=Schoenbaum>''Schoenbaum, Shakespeare's Lives'' (OUP, New York, 1970)</ref> Questioning Bacon's ability as a poet, ] asserted: " such authentic examples of Bacon's efforts to write verse as survive prove beyond all possibility of contradiction that, great as he was as a prose writer and a philosopher, he was incapable of penning any of the poetry assigned to Shakespeare."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bate |first1=Jonathan |title=The Genius of Shakespeare |date=1998 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-512823-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hh5pV-G-XtoC |page=88}}</ref> | |||

| In Raleigh's trial at ] on 17 November 1603, his statement was read out: "] offered me 10,000 crowns for the furthering the peace between England and Spain".<ref>Williams, Norman Lloyd: ''Sir Walter Raleigh'' (Eyre and Spottiswoode: 1963), p. 188.</ref> In 1.2.60-4 of ''Macbeth'', the King's messenger reports on the king of Norway, who has been assisted by the thane of Cawdor: | |||

| At least one Stratfordian scholar claims Bacon privately disavowed the idea he was a poet, and, seen in the context of Bacon's philosophy, the "concealed poet" is something other than a dramatic or narrative poet.<ref>{{Harvnb|Stopes|2003|pp=65–67}}</ref> A mainstream historian of authorship doubt, ], asserted that the "essential pattern of the Baconian argument" consisted of "expressed dissatisfaction with the number of historical records of Shakespeare's career, followed by the substitution of a wealth of imaginative conjectures in their place."<ref>{{harvnb|Wadsworth|1958|p=17}}</ref> | |||

| ::''Rosse''. That now | |||

| ::Sweno, the Norwayes king, craves composition: | |||

| ::Nor would we deigne him burial of his men, | |||

| ::Till he disbursed, at Saint Colmes ynch , | |||

| ::Ten thousand Dollars to our general use. | |||

| In his 1971 essay "Bill and I," the author and scientific historian ] made the case that Bacon did not write Shakespeare's plays because certain portions of the Shakespeare canon show a misunderstanding of the prevailing scientific beliefs of the time that Bacon, one of the most intensely educated people of his time, would not have possessed. Asimov cites an excerpt from the last act of '']'', as well as the following excerpt from '']'': | |||

| Shake-speare was known for his use of anagrams (e.g. the character Moth in ''Love's Labour's Lost'' represents ''Thom''as Nashe)<ref>Quiller-Couch, Sir Arthur, and Dover Wilson, John, ''Love's Labour's Lost'' (Cambridge University Press: 1923), pp.xxi-xxiii</ref> and here he has altered Cawder to Cawdor, an anagram of "coward". Some Baconians see this as an allusion to Raleigh's poem the night before his execution.{{Citation needed|date=October 2008}} | |||

| ::::...The rude sea grew civil at her song, | |||

| ::Cowards fear to die; but courage stout, | |||

| ::::And certain stars shot madly from their spheres, | |||

| ::Rather than live in snuff, will be put out.<ref>Raleigh's Remains, (edited 1661), p.258</ref> | |||

| ::::to hear the sea maid's music. (Act 2, Scene 1, 152–154). | |||

| In the above example, the reference to stars shooting madly from their ''spheres'' was not in accordance with the then-accepted Greek astronomical belief that the stars all occupied the same sphere that surrounded the ] as opposed to separate ones. While it was believed that additional ambient spheres existed, they were thought to contain the other bodies in the sky that move independently from the rest of the stars, i.e. the ], the ], and the ] that are visible to the naked eye (whose name makes its way into English from the Greek word ''planetes'', meaning "wanderers," as in the wandering bodies that orbited the Earth independently from the fixed stars in their sphere).<ref>] (1972). '']'', pp. 214–26</ref> | |||

| Some scholars<ref>Muir, Kenneth (Ed.), ''Macbeth'', The Arden Shakespeare (Thomson Learning: 2005), p.xxxii</ref> believe that ''Macbeth'' was later altered by Middleton, but a reference to Raleigh's execution would be particularly advantageous to the Baconian theory because Bacon was one of the six Commissioners from the Privy Council appointed to examine Raleigh's case.<ref>Spedding, James: ''The Life and Letters of Francis Bacon'', Vol. 6 (1872), p. 356.</ref> | |||

| ==References in popular culture== | |||