| Revision as of 18:23, 10 May 2011 editSnowmanradio (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers118,298 editsm moved Indian White-rumped Vulture to White-rumped Vulture over redirect: ioc name← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:01, 24 November 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,414,638 edits Added bibcode. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | #UCB_toolbar | ||

| (224 intermediate revisions by 97 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Species of bird}} | |||

| {{Taxobox | |||

| {{Speciesbox | |||

| | name = Indian White-rumped Vulture | |||

| | image = White-rumped_vulture_(Gyps_bengalensis)_Photograph_by_Shantanu_Kuveskar.jpg | |||

| | image = Gyps bengalensis PLoS.png | |||

| | image_caption = White-rumped vulture in ], Raigad, Maharashtra | |||

| | status = CR | status_system = IUCN3.1 | |||

| | status = CR | |||

| | status_ref=<ref>{{IUCN2008|assessors=BirdLife International|year=2008|id=144350|title=Gyps bengalensis|downloaded=11 July 2009}}</ref> | |||

| | status_system = IUCN3.1 | |||

| | regnum = ]ia | |||

| | status_ref = <ref name=iucn>{{cite iucn |title=''Gyps bengalensis'' |author=BirdLife International |date=2021 |page=e.T22695194A204618615 |access-date=20 November 2021}}</ref> | |||

| | phylum = ] | |||

| | genus = Gyps | |||

| | classis = ] | |||

| | species = bengalensis | |||

| | ordo = ] | |||

| | authority = (], 1788) | |||

| | familia = ] | |||

| | genus = '']'' | |||

| | species = '''''G. bengalensis''''' | |||

| | binomial = ''Gyps bengalensis'' | |||

| | binomial_authority = (], 1788) | |||

| | synonyms = ''Pseudogyps bengalensis'' | | synonyms = ''Pseudogyps bengalensis'' | ||

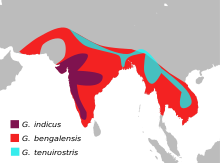

| | range_map = GypsBengalensisMap.svg | | range_map = GypsBengalensisMap.svg | ||

| | range_map_caption = Former distribution of |

| range_map_caption = Former distribution of the white-rumped vulture in red | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| The ''' |

The '''white-rumped vulture''' ('''''Gyps bengalensis''''') is an ] native to South and Southeast Asia. It has been listed as ] on the ] since 2000, as the population severely declined. White-rumped vultures die of ] caused by ] poisoning.<ref name=iucn/> | ||

| In the 1980s, the global population was estimated at several million individuals, and it was thought to be "the most abundant large ] in the world".<ref>{{cite book |author=Houston, D. C. |year=1985 |chapter=Indian White-backed Vulture (''Gyps bengalensis'') |title=Conservation studies of raptors |editor1=Newton, I. |editor2=Chancellor, R. D. |publisher=International Council for Bird Preservation |location=Cambridge, U.K |pages=456–466}}</ref> As of 2021, the global population was estimated at less than 6,000 mature individuals.<ref name=iucn/> | |||

| It is closely related to the European ] (''Gyps fulvus''). At one time it was believed to be closer to the ] of Africa and was known as the '''Oriental white-backed vulture'''.<ref name="PrakashPainCunningham2003" /> | |||

| Numbers of the species declined rapidly in the decades from 1990.<ref name=bcons>{{cite journal |year=2003|title= Catastrophic collapse of Indian white-backed Gyps bengalensis and long-billed ''Gyps indicus'' vulture populations. |journal=Biological Conservation |volume=109|issue=3|page=381|doi=10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00164-7 |author1=Prakash, V |author2=Pain, D.J |author3=Cunningham, A.A |author4=Donald, P.F |author5=Prakash, N |author6=Verma, A |author7=Gargi, R |author8=Sivakumar, S |author9=Rahmani, A.R}}</ref> As recently as 1985 the species was described as "possibly the most abundant large bird of prey in the world"<ref name="birdlife.org"></ref> Once considered a nuisance, the ]n population of White-rumped Vultures is now rare and for every 1,000 White-rumped Vultures recorded in India in 1992, only one remains today.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.birdlife.org/news/news/2009/08/vulture_success.html|title=New nestlings bring cautious hope for Asia's Threatened vultures}}</ref> | |||

| == |

==Taxonomy== | ||

| The white-rumped vulture was ] in 1788 by the German naturalist ] in his revised and expanded edition of ]'s '']''. He placed it with the vultures in the ] '']'' and coined the ] ''Vultur bengalensis''.<ref>{{ cite book | last=Gmelin | first=Johann Friedrich | author-link=Johann Friedrich Gmelin| year=1788 | title=Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis | edition=13th | volume=1, Part 1 | language=Latin | location=Lipsiae | publisher=Georg. Emanuel. Beer | page=245 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2896845 }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Gmelin based his description on the "Bengal vulture" that had been described and illustrated in 1781 by the English ornithologist ] in his multi-volume ''A General Synopsis of Birds''. Latham had seen a live bird at the ] and had been told by the keeper that it had come from Bengal.<ref>{{ cite book | last=Latham | first=John | author-link=John Latham (ornithologist) | year=1781 | title=A General Synopsis of Birds | volume=1, Part 1 | publisher=Printed for Leigh and Sotheby | location=London | page=19 No. 16, Plate 1 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/33727521 }}</ref><ref>{{ cite book | editor1-last=Mayr | editor1-first=Ernst | editor1-link=Ernst Mayr | editor2-last=Cottrell | editor2-first=G. William | year=1979 | title=Check-List of Birds of the World | volume=1 | edition=2nd | publisher=Museum of Comparative Zoology | place=Cambridge, Massachusetts | page=305 | url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/16108945 }}</ref> The white-rumped vulture is now one of eight species placed in the genus '']'' that was introduced in 1809 by the French zoologist ].<ref>{{ cite book | last=Savigny | first=Marie Jules César | author-link=Marie Jules César Savigny | year=1809 | title=Description de l'Égypte: Histoire naturelle | volume=1 | publisher=Imprimerie impériale | location=Paris | language=French | pages=, }}</ref><ref name=ioc>{{cite web| editor1-last=Gill | editor1-first=Frank | editor1-link=Frank Gill (ornithologist) | editor2-last=Donsker | editor2-first=David | editor3-last=Rasmussen | editor3-first=Pamela | editor3-link=Pamela Rasmussen | date=August 2022 | title=Hoatzin, New World vultures, Secretarybird, raptors | work=IOC World Bird List Version 12.2 | url=https://www.worldbirdnames.org/bow/raptors/| publisher=International Ornithologists' Union | access-date=2 December 2022 }}</ref> The genus name is from ] ''gups'' meaning "vultur".<ref>{{cite book | last=Jobling | first=James A. | year=2010| title=The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names | publisher=Christopher Helm | location=London | isbn=978-1-4081-2501-4 | page=183 | url=https://archive.org/stream/Helm_Dictionary_of_Scientific_Bird_Names_by_James_A._Jobling#page/n183/mode/1up }}</ref> The species is ]: no ] are recognised.<ref name=ioc/> | |||

| The White-rumped Vulture is a typical vulture, with an unfeathered head and neck, very broad wings, and short tail feathers. It is much smaller than European Griffon. It has a white neck ruff. The adult's whitish back, rump, and underwing coverts contrast with the otherwise dark plumage. The body is black and the secondaries are silvery grey. The head is tinged in pink and bill is silvery with dark ceres. The nostril openings are slit-like. Juveniles are largely dark and take about four or five years to acquire the adult plumage. In flight, the adults show a dark leading edge of the wing and has a white wing-lining on the underside. The undertail coverts are black.<ref name=pcr>{{cite book|author=Rasmussen, PC & JC Anderton|year=2005|title=Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide.|publisher=Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions.|volume=2|pages=89–90}}</ref> | |||

| == Description == | |||

| This is the smallest of the '']'' vultures, but is still a very large bird. It weighs 3.5-7.5 kg (7.7-16.5 lbs), measures 89–93 cm (30-37 in) in length,<ref name=pcr/> and has a wingspan of about 260 cm (8.6 ft).<ref name=hume/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The white-rumped vulture is a typical, medium-sized vulture, with an unfeathered head and neck, very broad wings, and short tail feathers. It is much smaller than the Eurasian Griffon. It has a white neck ruff. The adult's whitish back, rump, and underwing coverts contrast with the otherwise dark plumage. The body is black and the secondaries are silvery grey. The head is tinged in pink and bill is silvery with dark ceres. The nostril openings are slit-like. Juveniles are largely dark and take about four or five years to acquire the adult plumage. In flight, the adults show a dark leading edge of the wing and has a white wing-lining on the underside. The undertail coverts are black.<ref name="RasmussenAnderton2005" /> | |||

| It is the smallest of the '']'' vultures, but is still a very large bird. It weighs {{convert|3.5-7.5|kg|abbr=on}}, measures {{convert|75|–|93|cm|in|abbr=on}} in length,<ref name="RasmussenAnderton2005" /> and has a wingspan of {{convert|1.92|-|2.6|m|ft|abbr=on}}.<ref name="Hume1896">{{cite book |last=Hume |first=A. O. |author-link=Allan Octavian Hume |year=1896 |chapter=Gyps Bengalensis |title=My scrap book or rough notes on Indian ornithology |pages=26–31 |publisher=Baptist Mission Press |location=Calcutta |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/myscrapbookorrou00hume#page/26/mode/2up}}</ref><ref>Ferguson-Lees, J. and Christie, D.A. (2001). Raptors of the world. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. {{ISBN|0-618-12762-3}}</ref> | |||

| This vulture builds its nest on tall trees often near human habitations in northern and central ], ], ], and ], laying one egg. Birds form roost colonies. The population is mostly resident. | |||

| This vulture builds its nest on tall trees often near human habitations in northern and central India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and southeast Asia, laying one egg. Birds form roost colonies. The population is mostly resident. | |||

| Like other ]s it is a ], feeding mostly from carcasses of dead ]s which it finds by soaring high in thermals and spotting other scavengers. It often moves in flocks. At one time, it was the most numerous of the vultures in India.<ref name=pcr/> | |||

| Like other ]s it is a ], feeding mostly on carcasses, which it finds by soaring high in thermals and spotting other scavengers. A 19th century experimenter who hid a carcass of dog in a sack in a tree considered it capable of finding carrion by smell.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Hutton, T. |year=1837|title=Nest of the Bengal Vulture, (''Vultur Bengalensis'') with observations on the power of scent ascribed to the vulture tribe |url=https://archive.org/details/journalofasiatic61asia/page/112|journal=Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal |volume=6 |pages=112–118}}</ref> It often flies and sits in flocks. At one time, it was the most numerous vulture in India.<ref name="RasmussenAnderton2005">{{cite book |last1=Rasmussen |first1=P. C. |author-link=Pamela C. Rasmussen |last2=Anderton |first2=J. C. |year=2005 |title=Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Volume 2 |pages=89–90 |publisher=Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions}}</ref> | |||

| Within the well-supported clade of the genus ''Gyps'' which includes Asian, African, and European populations, it has been determined that this species is basal with the other species being more recent in their species divergence.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Johnson JA, Lerner HRL, Rasmussen PC and David P Mindell |title=Systematics within Gyps vultures: a clade at risk |year=2006|journal=BMC Evolutionary Biology |volume=6|page=65|doi=10.1186/1471-2148-6-65}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Evolutionary History of New and Old World Vultures Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of the Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene | |||

| |author=Ingrid Seibold and Andreas J. Helbig|journal=Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences |volume=350|issue=1332 |year=1995|pages=163–178|doi=10.1098/rstb.1995.0150|pmid=8577858|month=Nov|last1=Seibold|first1=I|last2=Helbig|first2=AJ|issn=0962-8436}}</ref> | |||

| Within the well-supported clade of the genus ''Gyps'' which includes Asian, African, and European populations, it has been determined that this species is basal with the other species being more recent in their species divergence.<ref name="SeiboldHelbig1995">{{cite journal|doi=10.1098/rstb.1995.0150 |title=Evolutionary History of New and Old World Vultures Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of the Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene |year=1995 |last1=Seibold |first1=I. |last2=Helbig |first2=A. J. |name-list-style=amp |journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B |volume=350 |issue=1332 |pages=163–178 |pmid=8577858|bibcode=1995RSPTB.350..163S}}</ref><ref name="Johnson2006">{{cite journal |doi=10.1186/1471-2148-6-65 |year=2006 |last1=Johnson |first1=J. A. |last2=Lerner|first2=H. R.L. |last3=Rasmussen |first3=P. C. |last4=Mindell|first4=D. P. |name-list-style=amp |title=Systematics within ''Gyps'' vultures: a clade at risk |journal=BMC Evolutionary Biology |volume=6|pages=65|pmc=1569873 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ==Behaviour and ecology== | |||

| These birds are usually inactive until the morning sun has warmed up the air with sufficient thermals to support their soaring. They circle and rise in altitude and join move off in a glide to change thermals. Large numbers were once visible in the late morning skies above Indian cities.<ref>{{cite book|page=238|title=Some Indian friends and acquaintances|author= Cunningham, David Douglas|year=1903|publisher=J Murray, London|url=http://www.archive.org/details/someindianfriend00cunnrich}}</ref> | |||

| == Behaviour and ecology == | |||

| When a kill is found they quickly descend and feed voraciously, and will perch on trees nearby and are known to sometimes descend even after dark to feed on a carcass. When feeding at carcasses they are dominated over by ]s ''Sarcogyps calvus''.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Morris,RC |year=1934|title= Death of an Elephant ''Elephas maximus'' Linn. while calving. |journal=J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. |volume= 37|issue=3|pages=722}}</ref> A whole bullock has been said to have been cleaned up by a pack of vultures in about 20 minutes.<ref name=hbk/> In forests, the sight of their soaring was often the indication of a tiger kill.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Gough,W |year=1936|title= Vultures feeding at night.|journal= J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc.|volume=38|issue=3|page=624}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Morris, RC|year=1935|title=Vultures feeding at night|journal=J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc.|volume=38|issue=1|page=190}}</ref> They may also swallow pieces of bone.<ref>{{cite journal| title=Calcium intake in vultures of the genus ''Gyps'' |pages=199–200|journal=J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc.|volume=70 | issue=1|author=Grubh, RB|year=1973}}</ref> Where water is available these birds bathe regularly and also drink water.<ref name=hbk>{{cite book|author=Ali S & S D Ripley | pages=307–310| title= Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan |year=1978| edition=2| volume=1| publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=0195620631}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| White-rumped vultures usually become active when the morning sun is warming up the air so that thermals are sufficient to support their soaring. They were once visible above Calcutta in large numbers.<ref name=Cunningham1903>{{cite book |last=Cunningham |first=D. D. | year=1903 |chapter=Vultures, eagles |title=Some Indian friends and acquaintances; a study of the ways of birds and other animals frequenting Indian streets and gardens| publisher = John Murray | location=London |pages=237–251 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/someindianfriend00cunnrich#page/236/mode/2up}}</ref> | |||

| When they find a carcass, they quickly descend and feed voraciously. They perch on trees nearby and are known to sometimes descend also after dark to feed. At kill sites, they are dominated by ]s ''Sarcogyps calvus''.<ref name=Morris1935>{{cite journal | last = Morris | first = R. C. | year = 1935 | |||

| ] noted based on the observation of "hundreds of nests" that they always nested on large trees near habitations even when there were convenient cliffs in the vicinity. The preferred nesting trees were ], ], ], and ]. The main nesting period was November to March with eggs being laid mainly in January. Nests are usually in clusters and isolated nests tend to be those of younger birds. Solitary nests are never used regularly and are sometimes taken over by the ] and large owls such as '']''. Nests are nearly 3 feet in diameter and half a foot in thickness. Prior to laying an egg, the nest is lined with green leaves. A single egg is laid which is white with a tinge of bluish-green. Female birds are reported to destroy the nest on loss of an egg. They are usually silent but make hissing and roaring sounds at the nest or when jostling for food.<ref name=hume>{{cite book|author=Hume, A O |year=1896|title=My Scrap Book or rough notes on Indian Ornithology|publisher=Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta|pages=26–31|url=http://www.archive.org/details/myscrapbookorrou00hume}}</ref> | |||

| |title=Death of an Elephant (''Elephas maximus'' Linn.) while calving |journal=Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society |volume=37 |issue = 3 | page = 722|url=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48733216}}</ref> | |||

| In forests, their soaring often indicated a ] kill.<ref name="Gough1936" /> They swallow pieces of old, dry bones such as ribs and of skull pieces from small mammals.<ref name="Grubh1973">{{cite journal |last=Grubh |first=R. B. |year=1973 |title=Calcium intake in vultures of the genus ''Gyps'' |journal=Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society |volume=70 |issue=1 |pages=199–200 |url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48290154#page/215/mode/1up}}</ref> | |||

| Where water is available they bathe regularly and also drink water. A pack of vultures was observed to have cleaned up a whole bullock in about 20 minutes. Trees on which they regularly roost are often white from their excreta, and this acidity often kills the trees. This made them less welcome in orchards and plantations.<ref name="AliRipley1978">{{cite book |last1=Ali |first1=Sálim |author1-link=Salim Ali |last2=Ripley |first2=S. D. |author2-link=Sidney Dillon Ripley |year=1978 |title=Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan, Volume 1 |pages=307–310 |edition=2nd |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-562063-4}}</ref> | |||

| They sometimes feed on dead vultures.<ref name="Prakash1988">{{Cite journal |last=Prakash |first=V. |year=1988 |title=Indian Scavenger Vulture (''Neophron percnopterus ginginianus'') feeding on a dead White-backed Vulture (''Gyps bengalensis'') |url=https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48805195 |journal=Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society |volume=85 |issue=3 |pages=614–615 |via=Biodiversity Heritage Library}}</ref><ref name="RanaPrakash2003">{{cite journal|last1 = Rana|first1 = G.|last2 = Prakash|first2 = V. |year=2003 | title = Cannibalism in Indian White-backed Vulture ''Gyps bengalensis'' in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan | journal = Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society | volume = 100 | issue = 1 | pages = 116–117|url=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48602690}}</ref> One white-rumped vulture was observed when getting caught in the mouth of a dying calf.<ref name="Greenwood1938" /> | |||

| Trees on which they regularly roost are often painted white with their excreta and this acidity often kills the trees. This made them less welcome in orchards and plantations.<ref name=hbk/> | |||

| ]s have been sighted to steal food brought by adults and regurgitated to young.<ref name="McCann1937"/> | |||

| ] observed "hundreds of nests" and noted that white-rumped vultures used to nest on large trees near habitations even when there were convenient cliffs in the vicinity. The preferred nesting trees were ], ], ], and ]. The main nesting period was November to March with eggs being laid mainly in January. Several pairs nest in the vicinity of each other and isolated nests tend to be those of younger birds. Nests are lined with green leaves.<ref name="Hume1896" /> | |||

| A freak case of a bird getting caught in the mouth of dying calf and dying trapped within has been noted.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Greenwood,JAC |year=1938|title= Strange accident to a Vulture. |journal=J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. |volume= 40|issue=2|pages=330}}</ref> ]s have been isolated from tissues of the bird.<ref>{{cite journal|author= Oaks, J. Lindsay, Donahoe, Shannon L., Rurangirwa, Fred R., Rideout, Bruce A., Gilbert, Martin, Virani, Munir Z.|title=Identification of a Novel Mycoplasma Species from an Oriental White-Backed Vulture (Gyps bengalensis)|journal=J. Clin. Microbiol. |year=2004|volume=42|pages= 5909–5912|doi= 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5909-5912.2004|pmid= 15583338|month= Dec|issue= 12|issn= 0095-1137|url= http://jcm.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15583338|format= Free full text|pmc= 535302}}</ref> ]n parasites such as ''Falcolipeurus'' and ''Colpocephalum turbinatum''<ref>{{cite journal|author=Price, RD & KC Emerson|title=New synonymies within the bird lice (Mallophaga)|journal=J. Kansas. Ent. Soc.|year=1966|volume=39|issue=3|pages=430–433|url=http://www.phthiraptera.org/Publications/0999.pdf|format=PDF}}</ref> have been collected from the species.<ref>{{cite journal|author=B. K. Tandan|title=Mallophaga from birds of the Indian subregion. Part VI ''Falcolipeurus'' Bedford|journal= Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society of London. Series B, Taxonomy |volume= 33|issue= 11-12|pages=173–180|year=1964|doi= 10.1111/j.1365-3113.1964.tb01599.x}}</ref> Ticks, ''Argas (Persicargas) abdussalami'', have been collected in numbers from the roost trees of these vultures in Pakistan.<ref>{{cite journal|title=The Subgenus Persicargas (Ixodoidea, Argasidae, Argas). 2. A. (P.) abdussalami, New Species, Associated with Wild Birds on Trees and Buildings near Lahore, Pakistan|author=Hoogstraal, Harry & McCarthy, Vincent C|journal=Annals of the Entomological Society of America| volume=58 |issue= 5|year= 1965|pages= 756–762|pmid=5834930}}</ref> A specimen in captivity lived for at least 12 years.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Stott Jr., Ken|year=1948|title=Notes on the longevity of captive birds|journal=Auk|volume=65|issue=3|pages=402–405|url=http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/Auk/v065n03/p0402-p0405.pdf|format=PDF}}</ref> | |||

| In ], white-rumped vultures used foremost '']'' and '']'' trees for nesting at a mean height of {{convert|26.73|m|abbr=on}}. Their nests were {{convert|1|m|abbr=on}} long, {{convert|40|cm|abbr=on}} wide and {{convert|15|cm|abbr=on}} deep. Hatchlings were seen from the first to the second week of January.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Samson, A. |author2=Ramakrishnan, B. |name-list-style=amp |year=2020 |title=The Critically Endangered White-rumped Vulture ''Gyps bengalensis'' in Sigur Plateau, Western Ghats, India: Population, breeding ecology, and threats |journal=Journal of Threatened Taxa |volume=12 |issue=13 |pages=16752–16763 |doi=10.11609/jott.3034.12.13.16752-16763 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Solitary nests are not used regularly and are sometimes taken over by the red-headed vulture and large owls such as '']''. The male initially brings twigs and arranges them to form the nest. During courtship the male bills the female's head, back and neck. The female invites copulation, and the male mounts and hold the head of the female in his bill.<ref name=Sharma /> Usually, the female lays a single egg, which is white with a tinge of bluish-green. Female birds destroy the nest on loss of an egg. They are usually silent but make hissing and roaring sounds at the nest or when jostling for food.<ref name="Hume1896" /> The eggs hatch after about 30 to 35 days of incubation. The young chick is covered with grey down. The parents feed them with bits of meat from a carcass. The young birds remain for about three months in the nest.<ref name=Sharma>{{cite journal|first=I. K. |last=Sharma |year=1970| title=Breeding of the Indian white-backed vulture at Jodhpur |journal=Ostrich| volume=41| issue=2|pages=205–207 |doi=10.1080/00306525.1970.9634367|bibcode=1970Ostri..41..205S }}</ref> | |||

| Jungle Crows have been seen to steal food brought by adults and regurgitated to young.<ref>{{cite journal|author=McCann,Charles |year=1937|title= Curious behaviour of the Jungle Crow (''Corvus macrorhynchus'') and the White-backed Vulture (''Gyps bengalensis''). |journal=J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. |volume= 39|issue=4|pages=864}}</ref> They may sometimes feed on dead vultures of their own species<ref>{{cite journal|author=Rana G & V Prakash|title=Cannibalism in Indian White-backed Vulture ''Gyps bengalensis'' in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc.|volume=100|issue=1|pages=116–117|year=2003}}</ref> while ]s have also been noted to feed on dead vulture fledgelings.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Prakash,Vibhu |year=1988 |title=Indian Scavenger Vulture (''Neophron percnopterus ginginianus'') feeding on a dead White-backed Vulture (''Gyps bengalensis''). |journal=J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. |volume= 85|issue=3 |pages=614–615}}</ref> | |||

| ]s have been isolated from tissues of a white-rumped vulture.<ref name="Oaks-etal2004" /> ]n parasites such as ''Falcolipeurus'' and ''Colpocephalum turbinatum''have been collected from the species.<ref name="Tandan1964" /><ref name="PriceEmerson1966" /> | |||

| Ticks, ''Argas (Persicargas) abdussalami'', have been collected in numbers from the roost trees of these vultures in Pakistan.<ref name="HoogstraalMcCarthy1965">{{cite journal |pmid=5834930 |year=1965| last1=Hoogstraal |first1 =H. | last2 =McCarthy| first2=V. C. | title=The subgenus ''Persicargas'' (Ixodoidea, Argasidae, Argas). 2. A. (P.) ''abdussalami'', new species, associated with wild birds on trees and buildings near Lahore, Pakistan |volume=58 |issue=5 | pages=756–762| journal =Annals of the Entomological Society of America |doi=10.1093/aesa/58.5.756}}</ref> | |||

| A captive individual lived for at least 12 years.<ref name="Stott1948" /> | |||

| ==Status and decline== | ==Status and decline== | ||

| ===In the Indian subcontinent=== | ===In the Indian subcontinent=== | ||

| {{See also|Indian vulture crisis}} | |||

| This species was very common, especially in the Gangetic plains of India and often seen nesting on the avenue trees within large cities in the region. ] noted for instance in his guide to the birds of India that it "is the commonest of all the Vultures of India, and must be familiar to those who have visited the Towers of Silence in Bombay."<ref>{{cite book|author=Whistler, Hugh|year=1949|title=Popular handbook of Indian birds|publisher=Gurney & Jackson, London|url=http://www.archive.org/details/popularhandbooko033226mbp| pages= 354–356|isbn=1406745766}}</ref> ] noted that "his is the most common Vulture of India, and is found in immense numbers all over the country, ... At Calcutta one may frequently be seen seated on the bloated corpse of some Hindoo floating up or down with the tide, its wing spread, to assist in steadying it..."<ref>{{cite book|author=Jerdon, TC|year=1862|title=The Birds of India. Volume 1|publisher=Military Orphan Press|page=11|url=http://www.archive.org/details/birdsofindiabein01jerd}}</ref> Prior to the 1990s they were even seen as a nuisance, particularly to aircraft as they were often involved in ]s.<ref>{{cite book|author=Satheesan SM|year=1994|chapter=The more serious vulture hits to military aircraft in India between 1980 and 1994.|title=Bird Strikes Committee Europe, Conference proceedings|publisher=BSCE, Vienna|url=http://www.int-birdstrike.org/Vienna_Papers/IBSC22%20WP23.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref><ref>Singh, R B (1999) Ecological strategy to prevent vulture menace to aircraft in India. Defence Science Journal 49(2):117-121 </ref> In 1990, the species had already become rare in Andhra Pradesh in the districts of Guntur and Prakasham. The hunting of the birds for meat by the Bandola (Banda) people there was attributed as a reason. A cyclone in the region during 1990 resulted in numerous livestock deaths and no vultures were found at the carcasses.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.int-birdstrike.org/Amsterdam_Papers/IBSC25%20WPSA3.pdf|chapter=Serious vulture-hits to aircraft over the world|author=Satheesan, SM & Manjula Satheesan|year=2000|title=International Bird Strike Committee IBSC25/WP-SA3|publisher=IBSC, Amsterdam}}</ref> | |||

| The white-rumped vulture was originally very common especially in the Gangetic plains of India, and often seen nesting on the avenue trees within large cities in the region. ] noted for instance in his guide to the birds of India that it “is the commonest of all the vultures of India, and must be familiar to those who have visited the Towers of Silence in Bombay.”<ref name="Whistler1949" /> ] noted that “his is the most common vulture of India, and is found in immense numbers all over the country, ... At Calcutta one may frequently be seen seated on the bloated corpse of some Hindoo floating up or down with the tide, its wing spread, to assist in steadying it...”<ref name=Jerdon1862>{{cite book |last=Jerdon |first=T. C. |year=1862 |title=The Birds of India |volume=1 |chapter=Gyps Bengalensis |pages=10–12 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/birdsofindiabein01jerd#page/10/mode/2up |publisher=Military Orphan Press}}</ref> | |||

| Before the 1990s they were even seen as a nuisance, particularly to aircraft as they were often involved in ]s.<ref>{{cite book |author=Satheesan, S. M. |year=1994 |chapter=The more serious vulture hits to military aircraft in India between 1980 and 1994 |title=Bird Strikes Committee Europe, Conference proceedings |publisher=BSCE |location=Vienna |chapter-url=http://www.int-birdstrike.org/Vienna_Papers/IBSC22%20WP23.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Singh, R. B. |year=1999 |title=Ecological strategy to prevent vulture menace to aircraft in India |journal=Defence Science Journal |volume=49 |issue=2 |pages=117–121 |doi=10.14429/dsj.49.3796 |doi-access=free }}</ref> In 1941 ] wrote about the death of '']'' palms due to the effect of excreta from vultures roosting on them.<ref>{{cite journal |author=McCann, C. |year=1941|title=Vultures and palms |journal=Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society |volume= 42|issue=2|pages=439–440 |url=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/47873208}}</ref> In 1990, the species had already become rare in Andhra Pradesh in the districts of ] and ]. The hunting of the birds for meat by the Bandola (]) people there was attributed as a reason. A cyclone in the region during 1990 resulted in numerous livestock deaths and no vultures were found at the carcasses.<ref>{{cite book |chapter=Serious vulture-hits to aircraft over the world |author1=Satheesan, S. M. |author2=M. Satheesan |name-list-style=amp |year=2000 |title=International Bird Strike Committee IBSC25/WP-SA3 |publisher=IBSC |location=Amsterdam |chapter-url=http://www.int-birdstrike.org/Amsterdam_Papers/IBSC25%20WPSA3.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| This species, as well as the ] and ]s have suffered a 99 percent population decrease in ]<ref>{{cite journal|author=V. Prakash, R.E. Green, D.J. Pain, S.P. Ranade, S. Saravanan, N. Prakash, R. Venkitachalam, R. Cuthbert, A.R. Rahmani, & A.A. Cunningham |year=2007|title= Recent changes in populations of resident Gyps vultures in India.|journal= J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. |volume=104|issue=2|pages=129–135 |url=https://www.rspb.org.uk/Images/IndianVultureDeclines_tcm9-188415.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref> and nearby countries<ref>{{cite journal |year=2005 |title= Population status and breeding ecology of White-rumped Vulture Gyps bengalensis in Rampur Valley, Nepal. |journal=Forktail |volume=21|pages= 87–91 |url=http://www.orientalbirdclub.org/publications/forktail/21pdf/Baral-Vulture.pdf |format=PDF |author1=Baral, Nabin |author2=Gautam, Ramji |author3=Tamang, Bijay}}</ref> since the early 1990s. The decline has been widely attributed to poisoning by ], which is used as veterinary ] (NSAID), leaving traces in cattle carcasses which when fed on leads to kidney failure in birds.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Green R. E., Newton, I, Shultz, S., Cunningham, A. A., Gilbet, M., Pain, D. J. and Prakash, V. |year=2004 |title= Diclofenac poisoning as a cause of vulture population declines across the Indian subcontinent. |journal=J.Anim. Ecol.|volume=41|pages=793–800|doi=10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00954.x}}</ref> Diclofenac was also found to be lethal at low dosages to other species in the genus ''Gyps''.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Gerry E Swan, Richard Cuthbert, Miguel Quevedo, Rhys E Green, Deborah J Pain, Paul Bartels, Andrew A Cunningham, Neil Duncan, Andrew A Meharg, J Lindsay Oaks, Jemima Parry-Jones, Susanne Shultz, Mark A Taggart, Gerhard Verdoorn, and Kerri Wolter |year=2006 |title= Toxicity of diclofenac to ''Gyps'' vultures.|journal= Biol. Lett.|volume= 2|issue=2|pages=279–282 |doi=10.1098/rsbl.2005.0425|pmid=17148382|month=Jun|last1=Swan|first1=GE|last2=Cuthbert|first2=R|last3=Quevedo|first3=M|last4=Green|first4=RE|last5=Pain|first5=DJ|last6=Bartels|first6=P|last7=Cunningham|first7=AA|last8=Duncan|first8=N|last9=Meharg|first9=AA|issn=1744-9561|url=http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17148382|format=Free full text|pmc=1618889}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Meteyer, Carol Uphoff, Rideout, Bruce A., Gilbert, Martin, Shivaprasad, H. L., Oaks, J. Lindsay|title=Pathology and proposed pathophysiology of diclofenac poisoning in free-living and experimentally exposed oriental white-backed vultures (''Gyps bengalensis''). |journal=J. Wild. Dis.|year=2005|volume=41|pages=707–716}}</ref> Other NSAIDs were also found to be toxic, to ''Gyps'' as well as other birds such as storks.<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Biol. Lett. |year=2007|volume=3|issue=1|pages=90–93 |doi= 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0554|title=NSAIDs and scavenging birds: potential impacts beyond Asia's critically endangered vultures|author=Richard Cuthbert, Jemima Parry-Jones, Rhys E Green, and Deborah J Pain|pmid=17443974|pmc=2373805}}</ref> Organochlorine pesticide was found from egg and tissue samples from around India varying in concentrations from 0.002 μg/g of DDE in muscles of vulture from Mudumalai to 7.30 μg/g in liver samples from vultures of Delhi. Dieldrin varied from 0.003 and 0.015 μg/g. These pesticide levels have not however been implicated in the decline.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Muralidharan, S., Dhananjayan, V., Risebrough, R., Prakash, V., Jayakumar, R., Bloom, P.H. |year=2008 |title= Persistent organochlorine pesticide residues in tissues and eggs of white-backed vulture, Gyps bengalensis from different locations in India. |journal=Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology |volume=81 |issue=6|pages=561–565|doi=10.1007/s00128-008-9529-z|pmid=18806909|month=Dec|last1=Muralidharan|first1=S|last2=Dhananjayan|first2=V|last3=Risebrough|first3=R|last4=Prakash|first4=V|last5=Jayakumar|first5=R|last6=Bloom|first6=PH|issn=0007-4861}}</ref> Another hypothesis is that they have been affected by ], as implicated in the extinctions of birds in the Hawaiian islands.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Ajay Poharkar, P. Anuradha Reddy, Vilas A. Gadge, Sunil Kolte, Nitin Kurkure and Sisinthy Shivaj|year= 2009|title= Is malaria the cause for decline in the wild population of the Indian White-backed vulture (''Gyps bengalensis'')?|journal= Current Science |volume=96|issue=4|page=553|url=http://www.ias.ac.in/currsci/feb252009/553.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref> | |||

| This species, as well as the ] and ] has suffered a 99% population decrease in India<ref>{{cite journal | author = Prakash, V.| year = 2007 | title = Recent changes in populations of resident ''Gyps'' vultures in India | journal = J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. | volume = 104 | issue = 2 | pages = 129–135 | url = https://www.rspb.org.uk/Images/IndianVultureDeclines_tcm9-188415.pdf |display-authors=etal}}</ref> and nearby countries<ref>{{cite journal | year = 2005 | title = Population status and breeding ecology of White-rumped Vulture ''Gyps bengalensis'' in Rampur Valley, Nepal | journal = Forktail | volume = 21 | pages = 87–91 | url = http://www.orientalbirdclub.org/publications/forktail/21pdf/Baral-Vulture.pdf | author1 = Baral, N. | author2 = Gautam, R. | author3 = Tamang, B. | access-date = 2009-05-11 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080704121157/http://www.orientalbirdclub.org/publications/forktail/21pdf/Baral-Vulture.pdf | archive-date = 2008-07-04 | url-status = dead }}</ref> since the early 1990s. The decline has been widely attributed to poisoning by ], which is used as veterinary ] (NSAID), leaving traces in cattle carcasses which when fed on leads to kidney failure in birds.<ref name="GreenNewtonShultz-etal2004" /> Diclofenac was also found to be lethal at low dosages to other species in the genus ''Gyps''.<ref name="SwanCuthbert-etal2006" /><ref>{{cite journal | author = Meteyer, Carol Uphoff | author2 = Rideout, Bruce A. | author3 = Gilbert, Martin | author4 = Shivaprasad, H. L. | author5 = Oaks, J. Lindsay | title = Pathology and proposed pathophysiology of diclofenac poisoning in free-living and experimentally exposed oriental white-backed vultures (''Gyps bengalensis'') | journal = J. Wildl. Dis. | year = 2005 | volume = 41 | issue = 4 | pages = 707–716 | doi=10.7589/0090-3558-41.4.707| pmid = 16456159 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2005JWDis..41..707M }}</ref> Other NSAIDs were also found to be toxic, to ''Gyps'' as well as other birds such as storks.<ref name="CuthbertParry-JonesGreenPain" /> It was shown between 2000-2007 annual decline rates in India averaged 43.9% and ranged from 11-61% in ]. Organochlorine pesticide residues were found from egg and tissue samples from around India varying in concentrations from 0.002 μg/g of DDE in muscles of vulture from Mudumalai to 7.30 μg/g in liver samples from vultures of Delhi. Dieldrin varied from 0.003 and 0.015 μg/g. Higher concentrations were found in Lucknow.<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://archive.org/stream/pesticidesmonito15unit#page/9/mode/1up|title=Organochlorine pesticide residues in some Indian wild birds|author1=Kaphalia, B. S. |author2=M. M. Husain |author3=T. D. Seth |author4=A. Kumar |author5=C. R. K. Murti |year=1981| journal=Pesticides Monitoring Journal|volume=15| issue=1| pages=9–13|pmid=7279596}}</ref> These pesticide levels have not however been implicated in the decline.<ref name="Muralidharan-etal2008" /> | |||

| Birds were reported to adopt a drooped neck posture and this was considered a symptom of pesticide poisoning,<ref name=bcons/> but some studies suggest that this may be a thermoregulatory response since this posture is seen mainly during hot weather.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Martin Gilbert, Richard T. Watson, Munir Z. Virani, J. Lindsay Oaks, Shakeel Ahmed, Muhammad Jamshed Iqbal Chaudhry, Muhammad Arshad, Shahid Mahmood, Ahmad Ali, and Aleem A. Khan |year=2007 |title= Neck-drooping Posture in Oriental White-Backed Vultures (''Gyps bengalensis''): An Unsuccessful Predictor of Mortality and Its Probable Role in Thermoregulation. |journal=Journal of Raptor Research |volume=41 |issue=1|pages=35–40|doi=10.3356/0892-1016(2007)412.0.CO;2}}</ref> | |||

| An alternate hypothesis is an epidemic of ], as implicated in the extinctions of birds in the Hawaiian islands. Evidence for the idea is drawn from an apparent recovery of a vulture following ] treatment.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Poharkar, A. | author2 =Reddy, P. A. | author3 =Gadge, V.A. | author4 =Kolte, S. |author5=Kurkure, N. | author6 =Shivaji, S P. | name-list-style = amp | year= 2009 | title = Is malaria the cause for decline in the wild population of the Indian White-backed vulture (''Gyps bengalensis'')? | journal = Current Science | volume = 96 | issue = 4 | page = 553 | url = http://www.ias.ac.in/currsci/feb252009/553.pdf }}</ref> Yet another suggestion has been that the population changes may be linked with long term climatic cycles such as the ].<ref>{{cite journal|author1=Hall, JC |author2=Chhangani, A. K. |author3=Waite, T. A. |author4=Hamilton, I. M. |year=2012 | title= The impacts of La Niña induced drought on Indian Vulture ''Gyps indicus'' populations in Western Rajasthan|journal= Bird Conservation International| volume=22|pages=247–259| | |||

| It has been suggested that rabies cases have increased in India due to the decline.<ref>{{cite journal |year=2008 |title= Counting the cost of vulture decline—An appraisal of the human health and other benefits of vultures in India. |journal= Ecological Economics |volume=67|issue=2|pages=194–204 |doi=10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.04.020 |author1=Markandya, Anil |author2=Tim Taylor, Alberto Longo}}</ref> | |||

| doi=10.1017/S0959270911000232|issue=3|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Affected vultures were initially reported to adopt a drooped neck posture and this was considered a symptom of ],<ref name="PrakashPainCunningham2003" /> but subsequent studies suggested that this may be a thermoregulatory response as the posture was seen mainly during hot weather.<ref name="GilbertWatsonVirani-etal2007" /> | |||

| ===In Southeast Asia=== | |||

| In Southeast Asia, the near-total disappearance of the species predated the present diclofenac crisis, and probably resulted from the collapse of large wild ungulate populations and improved management of deceased livestock resulting in a lack of available carcasses for vultures.<ref name="birdlife.org"/> | |||

| It has been suggested that ] cases have increased in India due to the decline.<ref name="Markandya-etal2008" /> | |||

| ==Conservation== | |||

| === In Southeast Asia === | |||

| Currently, only the ] and ] populations are thought to be viable.<ref name="birdlife.org"/> | |||

| In Southeast Asia, the near-total disappearance of white-rumped vultures predated the present diclofenac crisis, and probably resulted from the collapse of large wild ungulate populations and improved management of dead livestock, resulting in a lack of available carcasses for vultures.<ref name="BirdLife-factsheet" /> | |||

| It has been suggested that ] (another NSAID) as a veterinary substitute that is harmless to vultures would help in the recovery.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Swan, G., Naidoo, V., Cuthbert, R., Green, R., Pain, D., Swarup, D., et al.|year=2006 |title=Removing the Threat of Diclofenac to Critically Endangered Asian Vultures. |journal=PLoS Biology|volume= 4|issue=3|pages=395–402|doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066|pmid=16435886|month=Mar|last1=Swan|first1=G|last2=Naidoo|first2=V|last3=Cuthbert|first3=R|last4=Green|first4=RE|last5=Pain|first5=DJ|last6=Swarup|first6=D|last7=Prakash|first7=V|last8=Taggart|first8=M|last9=Bekker|first9=L|issn=1544-9173|url=http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066|format=Free full text|pmc=1351921}}</ref> Campaigns to ban the use of diclofenac in veterinary practice have been underway in several South Asian countries.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.birdlife.org/news/news/2008/01/nepal_vultures.html|title=Local increase in vultures thanks to diclofenac campaign in Nepal|publisher=BirdLife International|year=2008}}</ref> | |||

| == Conservation == | |||

| Conservation measures have included ], captive-breeding programs and artificial feeding or "vulture restaurants".<ref>{{cite journal|author=Gilbert, M., Watson, R.T., Ahmed, S., Asim, M., Johnson, J.A. |year=2007 |title= Vulture restaurants and their role in reducing diclofenac exposure in Asian vultures. |journal=Bird Conservation International |volume=17|issue=1|pages=63–77|doi=10.1017/S0959270906000621}}</ref> Two chicks, which were apparently the first captive-bred Indian White-rumped Vultures ever, hatched in January 2007, at a facility at ]. However, they died after a few weeks, apparently because their parents were an inexperienced couple breeding for the first time in their lives – a fairly common occurrence in birds of prey.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.planetark.com/dailynewsstory.cfm/newsid/40468/story.htm|title=First Captive-Bred Asian Vulture Chicks Die |year=2007}}</ref> | |||

| Currently, only the Cambodia and Burma populations are thought to be viable though those populations are still very small (low hundreds).<ref name="BirdLife-factsheet" /> It has been suggested that the use of ] (another NSAID) as a veterinary substitute that is safer for vultures would help in the recovery.<ref name="SwanNaidoo-etal2006" /> Campaigns to ban the use of ] in veterinary practice have been underway in several South Asian countries.<ref name="BirdLife-nepal_vultures" /> | |||

| ==References==<!-- Forktail13:109. Forktail15:87. Forktail18:151. --> | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| Conservation measures have included ], captive-breeding programs and artificial feeding or "vulture restaurants".<ref name="GilbertWatsonAhmed-etal2007" /> Two chicks, which were apparently the first captive-bred white-rumped vultures ever, hatched in January 2007, at a facility at ]. However, they died after a few weeks, apparently because their parents were an inexperienced couple breeding for the first time in their lives – a fairly common occurrence in birds of prey.<ref name="Reuters-2007-02-23" /> | |||

| ==Other sources== | |||

| * Ahmad, S. 2004. Time activity budget of Oriental White-backed Vulture (Gyps bengalensis) in Punjab, Pakistan. M. Phil. thesis, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Reflist | |||

| | colwidth = 30em | |||

| | refs = | |||

| <ref name="BirdLife-factsheet"> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| | title = White-rumped Vulture (''Gyps bengalensis'') — BirdLife species factsheet | |||

| | publisher = BirdLife International | |||

| | work = BirdLife.org | |||

| | url = http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=3374 | |||

| | access-date = 2011-06-01}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="PrakashPainCunningham2003"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00164-7|title=Catastrophic collapse of Indian white-backed Gyps bengalensis and long-billed ''Gyps indicus'' vulture populations|year=2003|last1=Prakash|first1=V. |journal=Biological Conservation|volume=109|issue=3|pages=381–390|last2=Pain|first2=D.J. |last3=Cunningham|first3=A.A. |last4=Donald|first4=P.F.|last5=Prakash|first5=N.|last6=Verma|first6=A.|last7=Gargi|first7=R.|last8=Sivakumar|first8=S.|last9=Rahmani|first9=A.R.|bibcode=2003BCons.109..381P }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Gough1936"> | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| | last = Gough | |||

| | first = W. | |||

| | year = 1936 | |||

| | title = Vultures feeding at night | |||

| | journal =Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society | volume = 38 | issue = 3 | page = 624|url=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/47602994}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Greenwood1938"> | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| | last = Greenwood | |||

| | first = J. A. C. | |||

| | year = 1938 | |||

| | title = Strange accident to a Vulture | |||

| | journal = Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society | volume = 40 | issue = 2 | page = 330|url=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/47602642}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Oaks-etal2004"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1128/JCM.42.12.5909-5912.2004|title=Identification of a Novel Mycoplasma Species from an Oriental White-Backed Vulture (''Gyps bengalensis'')|year=2004|last1=Oaks|first1=J. L.|last2=Donahoe|first2=S. L.|last3=Rurangirwa|first3=F. R.|last4=Rideout|first4=B. A.|last5=Gilbert|first5=M.|last6=Virani|first6=M. Z. |journal=Journal of Clinical Microbiology|volume=42|issue=12|pages=5909–5912|pmid=15583338|pmc=535302 }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| <ref name="PriceEmerson1966"> | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| | last1 = Price | |||

| | first1 = R. D. | |||

| | last2 = Emerson | |||

| | first2 = K.C. | |||

| | year = 1966 | |||

| | title = New synonymies within the bird lice (''Mallophaga'') | |||

| | journal = Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society | |||

| | volume = 39 | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| | pages = 430–433 | |||

| | jstor = 25083538 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| <ref name="Tandan1964"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1111/j.1365-3113.1964.tb01599.x|title=Mallophaga from birds of the Indian subregion. Part VI Falcolipeurus Bedford*|year=2009|last1=Tandan|first1=B. K.|journal=Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society of London B|volume=33|issue=11–12|pages=173–180 }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| <ref name="Stott1948"> | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| | last = Stott | |||

| | first = Ken Jr. | |||

| | year = 1948 | |||

| | title = Notes on the longevity of captive birds | |||

| | journal = Auk | |||

| | volume = 65 | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| | pages = 402–405 | |||

| | url = http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v065n03/p0402-p0405.pdf | |||

| | doi = 10.2307/4080488 | |||

| | jstor = 4080488}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="McCann1937"> | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| | last = McCann | |||

| | first = Charles | |||

| | year = 1937 | |||

| | title = Curious behaviour of the Jungle Crow (''Corvus macrorhynchus'') and the White-backed Vulture (''Gyps bengalensis'') | |||

| | journal =Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society | volume = 39 | issue = 4 | page = 864|url=https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/47591369}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Whistler1949"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Whistler | |||

| | first = Hugh | |||

| | year = 1949 | |||

| | title = Popular Handbook of Indian Birds | |||

| | pages = –356 | |||

| | publisher = Gurney & Jackson | |||

| | location = London | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/popularhandbooko033226mbp}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="GreenNewtonShultz-etal2004"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00954.x|title=Diclofenac poisoning as a cause of vulture population declines across the Indian subcontinent|year=2004|last1=Green|first1=Rhys E.|last2=Newton|first2=IAN|last3=Shultz|first3=Susanne|last4=Cunningham|first4=Andrew A.|last5=Gilbert|first5=Martin|last6=Pain|first6=Deborah J.|last7=Prakash|first7=Vibhu|journal=Journal of Applied Ecology|volume=41|issue=5|pages=793–800|bibcode=2004JApEc..41..793G |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="SwanCuthbert-etal2006"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1098/rsbl.2005.0425|title=Toxicity of diclofenac to Gyps vultures|year=2006|last1=Swan|first1=G. E|last2=Cuthbert|first2=R.|last3=Quevedo|first3=M.|last4=Green|first4=R. E|last5=Pain|first5=D. J|last6=Bartels|first6=P.|last7=Cunningham|first7=A. A|last8=Duncan|first8=N.|last9=Meharg|first9=A. A|last10=Lindsay Oaks|first10=J|last11=Parry-Jones|first11=J.|last12=Shultz|first12=S.|last13=Taggart|first13=M. A|last14=Verdoorn|first14=G.|last15=Wolter|first15=K.|journal=Biology Letters |volume=2|issue=2|pages=279–282|pmid=17148382|pmc=1618889 |display-authors=8}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="CuthbertParry-JonesGreenPain"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1098/rsbl.2006.0554|pmid=17443974|title=NSAIDs and scavenging birds: potential impacts beyond Asia's critically endangered vultures|year=2007|last1=Cuthbert|first1=R.|last2=Parry-Jones|first2=J.|last3=Green|first3=R. E|last4=Pain|first4=D. J|journal=Biology Letters|volume=3|issue=1|pages=91–94|pmc=2373805}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Muralidharan-etal2008"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1007/s00128-008-9529-z|title=Persistent Organochlorine Pesticide Residues in Tissues and Eggs of White-Backed Vulture, Gyps bengalensis from Different Locations in India |year=2008|last1=Muralidharan|first1=S.|last2=Dhananjayan|first2=V.|last3=Risebrough|first3=Robert|last4=Prakash|first4=V.|last5=Jayakumar|first5=R.|last6=Bloom|first6=Peter H.|journal=Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology|volume=81|issue=6|pages=561–565|pmid=18806909|bibcode=2008BuECT..81..561M |s2cid=22985718 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="GilbertWatsonVirani-etal2007"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.3356/0892-1016(2007)412.0.CO;2|issn=0892-1016|year=2007|volume=41|pages=35–40|title=Neck-drooping Posture in Oriental White-Backed Vultures (Gyps bengalensis): An Unsuccessful Predictor of Mortality and Its Probable Role in Thermoregulation|last1=Gilbert|first1=Martin|last2=Watson|first2=Richard T.|last3=Virani|first3=Munir Z.|last4=Oaks|first4=J. Lindsay|last5=Ahmed|first5=Shakeel|last6=Chaudhry|first6=Muhammad Jamshed Iqbal|last7=Arshad|first7=Muhammad|last8=Mahmood|first8=S. |last9=Ali|first9=A. |last10=Khan|first10=A. A. |journal=Journal of Raptor Research|s2cid=85581650 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Markandya-etal2008"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.04.020|title=Counting the cost of vulture decline—An appraisal of the human health and other benefits of vultures in India |year=2008 |last1=Markandya |first1=A. |last2=Taylor|first2=T. |last3=Longo|first3=A. |last4=Murty |first4=M.N.|last5=Murty |first5=S.|last6=Dhavala|first6=K.|journal=Ecological Economics|volume=67|issue=2|pages=194–204|bibcode=2008EcoEc..67..194M |url=https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/10036/4350/7/Vultures.pdf|hdl=10036/4350 |hdl-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="SwanNaidoo-etal2006"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066|title=Removing the Threat of Diclofenac to Critically Endangered Asian Vultures|year=2006|last1=Swan|first1=G. |last2=Naidoo|first2=V. |last3=Cuthbert|first3=R. |last4=Green|first4=Rhys E.|last5=Pain|first5=D. J. |last6=Swarup |first6=D. |last7=Prakash|first7=V. |last8=Taggart|first8=M. |last9=Bekker|first9=L. |last10=Das|first10=D. |last11=Diekmann|first11=J. |last12=Diekmann|first12=M. |last13=Killian|first13=E. |last14=Meharg|first14=A. |last15=Patra|first15=R. C. |last16=S. |first16=Mohini|last17=Wolter|first17=K. |journal=PLOS Biology |volume=4 |issue=3 |pages=e66|pmid=16435886|pmc=1351921 |display-authors=8 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="BirdLife-nepal_vultures"> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| | title = Local increase in vultures thanks to diclofenac campaign in Nepal | |||

| | date = 2008-11-01 | |||

| | publisher = BirdLife International | |||

| | url = http://www.birdlife.org/news/news/2008/01/nepal_vultures.html | |||

| | access-date = 2011-06-01 | |||

| | author = Hem Sagar Baral (BCN) | |||

| | author2 = Chris Bowden (RSPB) | |||

| | author3 = Richard Cuthbert (RSPB) | |||

| | author4 = Dev Ghimire (BCN)}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="GilbertWatsonAhmed-etal2007"> | |||

| {{cite journal|doi=10.1017/S0959270906000621|title=Vulture restaurants and their role in reducing diclofenac exposure in Asian vultures|year=2007|last1=Gilbert|first1=M. |last2=Watson|first2=R. T. |last3=Ahmed|first3=S. |last4=Asim|first4=M. |last5=Johnson|first5=J. A.|journal=Bird Conservation International|volume=17|pages=63–77|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Reuters-2007-02-23">{{cite news | agency = Reuters | year = 2007 | title = First Captive-Bred Asian Vulture Chicks Die | work = planetark.com | url = http://www.planetark.com/dailynewsstory.cfm/newsid/40468/story.htm | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070225074930/http://www.planetark.com/dailynewsstory.cfm/newsid/40468/story.htm | |||

| | url-status = usurped | |||

| | archive-date = February 25, 2007 | |||

| | access-date = 2011-06-01}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| == Other sources == | |||

| * Ahmad, S. 2004. Time activity budget of Oriental White-backed Vulture (''Gyps bengalensis'') in Punjab, Pakistan. M. Phil. thesis, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. | |||

| * Grubh, R. B. 1974. The ecology and behaviour of vultures in Gir Forest. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Bombay, Bombay, India. | * Grubh, R. B. 1974. The ecology and behaviour of vultures in Gir Forest. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Bombay, Bombay, India. | ||

| * Grubh, R. B. 1988. A comparative study of the ecology and distribution of the Indian White-backed Vulture (Gyps bengalensis) and the Long-billed Vulture (G. indicus) in the Indian region. Pages |

* Grubh, R. B. 1988. A comparative study of the ecology and distribution of the Indian White-backed Vulture (''Gyps bengalensis'') and the Long-billed Vulture (G. indicus) in the Indian region. Pages 2763–2767 in Acta 19 Congressus Internationalis Ornithologici. Volume 2. Ottawa, Canada 22–29 June 1986 (H. Ouellet, Ed.). University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa, Ontario. | ||

| * Eck, S. 1981. . Ornithologische Jahresberichte des Museums Heineanum 5-6:71-73. | * Eck, S. 1981. . Ornithologische Jahresberichte des Museums Heineanum 5-6:71-73. | ||

| * Naidoo, Vinasan 2008. Diclofenac in Gyps vultures : a molecular mechanism of toxicity. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria. (Includes old photos showing their numbers) | * Naidoo, Vinasan 2008. Diclofenac in ''Gyps'' vultures : a molecular mechanism of toxicity. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria. (Includes old photos showing their numbers) | ||

| ==External links== | == External links == | ||

| * | |||

| {{Commons|Gyps bengalensis}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| {{Vulture}} | |||

| {{Old World vultures}} | |||

| {{Taxonbar|from=Q327118}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 02:01, 24 November 2024

Species of bird

| White-rumped vulture | |

|---|---|

| |

| White-rumped vulture in Mangaon, Raigad, Maharashtra | |

| Conservation status | |

Critically Endangered (IUCN 3.1) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Gyps |

| Species: | G. bengalensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Gyps bengalensis (Gmelin, JF, 1788) | |

| |

| Former distribution of the white-rumped vulture in red | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pseudogyps bengalensis | |

The white-rumped vulture (Gyps bengalensis) is an Old World vulture native to South and Southeast Asia. It has been listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2000, as the population severely declined. White-rumped vultures die of kidney failure caused by diclofenac poisoning. In the 1980s, the global population was estimated at several million individuals, and it was thought to be "the most abundant large bird of prey in the world". As of 2021, the global population was estimated at less than 6,000 mature individuals.

It is closely related to the European griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus). At one time it was believed to be closer to the white-backed vulture of Africa and was known as the Oriental white-backed vulture.

Taxonomy

The white-rumped vulture was formally described in 1788 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in his revised and expanded edition of Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae. He placed it with the vultures in the genus Vultur and coined the binomial name Vultur bengalensis. Gmelin based his description on the "Bengal vulture" that had been described and illustrated in 1781 by the English ornithologist John Latham in his multi-volume A General Synopsis of Birds. Latham had seen a live bird at the Tower of London and had been told by the keeper that it had come from Bengal. The white-rumped vulture is now one of eight species placed in the genus Gyps that was introduced in 1809 by the French zoologist Marie Jules César Savigny. The genus name is from Ancient Greek gups meaning "vultur". The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.

Description

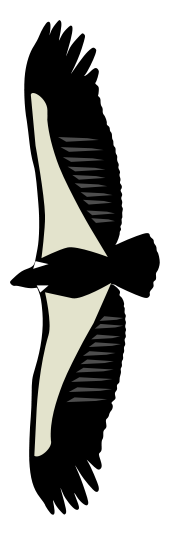

The white-rumped vulture is a typical, medium-sized vulture, with an unfeathered head and neck, very broad wings, and short tail feathers. It is much smaller than the Eurasian Griffon. It has a white neck ruff. The adult's whitish back, rump, and underwing coverts contrast with the otherwise dark plumage. The body is black and the secondaries are silvery grey. The head is tinged in pink and bill is silvery with dark ceres. The nostril openings are slit-like. Juveniles are largely dark and take about four or five years to acquire the adult plumage. In flight, the adults show a dark leading edge of the wing and has a white wing-lining on the underside. The undertail coverts are black.

It is the smallest of the Gyps vultures, but is still a very large bird. It weighs 3.5–7.5 kg (7.7–16.5 lb), measures 75–93 cm (30–37 in) in length, and has a wingspan of 1.92–2.6 m (6.3–8.5 ft).

This vulture builds its nest on tall trees often near human habitations in northern and central India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and southeast Asia, laying one egg. Birds form roost colonies. The population is mostly resident.

Like other vultures it is a scavenger, feeding mostly on carcasses, which it finds by soaring high in thermals and spotting other scavengers. A 19th century experimenter who hid a carcass of dog in a sack in a tree considered it capable of finding carrion by smell. It often flies and sits in flocks. At one time, it was the most numerous vulture in India.

Within the well-supported clade of the genus Gyps which includes Asian, African, and European populations, it has been determined that this species is basal with the other species being more recent in their species divergence.

Behaviour and ecology

White-rumped vultures usually become active when the morning sun is warming up the air so that thermals are sufficient to support their soaring. They were once visible above Calcutta in large numbers.

When they find a carcass, they quickly descend and feed voraciously. They perch on trees nearby and are known to sometimes descend also after dark to feed. At kill sites, they are dominated by red-headed vultures Sarcogyps calvus. In forests, their soaring often indicated a tiger kill. They swallow pieces of old, dry bones such as ribs and of skull pieces from small mammals. Where water is available they bathe regularly and also drink water. A pack of vultures was observed to have cleaned up a whole bullock in about 20 minutes. Trees on which they regularly roost are often white from their excreta, and this acidity often kills the trees. This made them less welcome in orchards and plantations.

They sometimes feed on dead vultures. One white-rumped vulture was observed when getting caught in the mouth of a dying calf. Jungle crows have been sighted to steal food brought by adults and regurgitated to young.

Allan Octavian Hume observed "hundreds of nests" and noted that white-rumped vultures used to nest on large trees near habitations even when there were convenient cliffs in the vicinity. The preferred nesting trees were Banyan, Peepul, Arjun, and Neem. The main nesting period was November to March with eggs being laid mainly in January. Several pairs nest in the vicinity of each other and isolated nests tend to be those of younger birds. Nests are lined with green leaves. In Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, white-rumped vultures used foremost Terminalia arjuna and Spondias mangifera trees for nesting at a mean height of 26.73 m (87.7 ft). Their nests were 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long, 40 cm (16 in) wide and 15 cm (5.9 in) deep. Hatchlings were seen from the first to the second week of January.

Solitary nests are not used regularly and are sometimes taken over by the red-headed vulture and large owls such as Bubo coromandus. The male initially brings twigs and arranges them to form the nest. During courtship the male bills the female's head, back and neck. The female invites copulation, and the male mounts and hold the head of the female in his bill. Usually, the female lays a single egg, which is white with a tinge of bluish-green. Female birds destroy the nest on loss of an egg. They are usually silent but make hissing and roaring sounds at the nest or when jostling for food. The eggs hatch after about 30 to 35 days of incubation. The young chick is covered with grey down. The parents feed them with bits of meat from a carcass. The young birds remain for about three months in the nest.

Mycoplasmas have been isolated from tissues of a white-rumped vulture. Mallophagan parasites such as Falcolipeurus and Colpocephalum turbinatumhave been collected from the species. Ticks, Argas (Persicargas) abdussalami, have been collected in numbers from the roost trees of these vultures in Pakistan.

A captive individual lived for at least 12 years.

Status and decline

In the Indian subcontinent

See also: Indian vulture crisisThe white-rumped vulture was originally very common especially in the Gangetic plains of India, and often seen nesting on the avenue trees within large cities in the region. Hugh Whistler noted for instance in his guide to the birds of India that it “is the commonest of all the vultures of India, and must be familiar to those who have visited the Towers of Silence in Bombay.” T. C. Jerdon noted that “his is the most common vulture of India, and is found in immense numbers all over the country, ... At Calcutta one may frequently be seen seated on the bloated corpse of some Hindoo floating up or down with the tide, its wing spread, to assist in steadying it...”

Before the 1990s they were even seen as a nuisance, particularly to aircraft as they were often involved in bird strikes. In 1941 Charles McCann wrote about the death of Borassus palms due to the effect of excreta from vultures roosting on them. In 1990, the species had already become rare in Andhra Pradesh in the districts of Guntur and Prakasham. The hunting of the birds for meat by the Bandola (Banda) people there was attributed as a reason. A cyclone in the region during 1990 resulted in numerous livestock deaths and no vultures were found at the carcasses.

This species, as well as the Indian vulture and slender-billed vulture has suffered a 99% population decrease in India and nearby countries since the early 1990s. The decline has been widely attributed to poisoning by diclofenac, which is used as veterinary non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), leaving traces in cattle carcasses which when fed on leads to kidney failure in birds. Diclofenac was also found to be lethal at low dosages to other species in the genus Gyps. Other NSAIDs were also found to be toxic, to Gyps as well as other birds such as storks. It was shown between 2000-2007 annual decline rates in India averaged 43.9% and ranged from 11-61% in Punjab. Organochlorine pesticide residues were found from egg and tissue samples from around India varying in concentrations from 0.002 μg/g of DDE in muscles of vulture from Mudumalai to 7.30 μg/g in liver samples from vultures of Delhi. Dieldrin varied from 0.003 and 0.015 μg/g. Higher concentrations were found in Lucknow. These pesticide levels have not however been implicated in the decline.

An alternate hypothesis is an epidemic of avian malaria, as implicated in the extinctions of birds in the Hawaiian islands. Evidence for the idea is drawn from an apparent recovery of a vulture following chloroquine treatment. Yet another suggestion has been that the population changes may be linked with long term climatic cycles such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation.

Affected vultures were initially reported to adopt a drooped neck posture and this was considered a symptom of pesticide poisoning, but subsequent studies suggested that this may be a thermoregulatory response as the posture was seen mainly during hot weather.

It has been suggested that rabies cases have increased in India due to the decline.

In Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, the near-total disappearance of white-rumped vultures predated the present diclofenac crisis, and probably resulted from the collapse of large wild ungulate populations and improved management of dead livestock, resulting in a lack of available carcasses for vultures.

Conservation

Currently, only the Cambodia and Burma populations are thought to be viable though those populations are still very small (low hundreds). It has been suggested that the use of meloxicam (another NSAID) as a veterinary substitute that is safer for vultures would help in the recovery. Campaigns to ban the use of diclofenac in veterinary practice have been underway in several South Asian countries.

Conservation measures have included reintroduction, captive-breeding programs and artificial feeding or "vulture restaurants". Two chicks, which were apparently the first captive-bred white-rumped vultures ever, hatched in January 2007, at a facility at Pinjore. However, they died after a few weeks, apparently because their parents were an inexperienced couple breeding for the first time in their lives – a fairly common occurrence in birds of prey.

References

- ^ BirdLife International (2021). "Gyps bengalensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T22695194A204618615. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- Houston, D. C. (1985). "Indian White-backed Vulture (Gyps bengalensis)". In Newton, I.; Chancellor, R. D. (eds.). Conservation studies of raptors. Cambridge, U.K: International Council for Bird Preservation. pp. 456–466.

- ^ Prakash, V.; Pain, D.J.; Cunningham, A.A.; Donald, P.F.; Prakash, N.; Verma, A.; Gargi, R.; Sivakumar, S.; Rahmani, A.R. (2003). "Catastrophic collapse of Indian white-backed Gyps bengalensis and long-billed Gyps indicus vulture populations". Biological Conservation. 109 (3): 381–390. Bibcode:2003BCons.109..381P. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00164-7.

- Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1788). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 1 (13th ed.). Lipsiae : Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 245.

- Latham, John (1781). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 1, Part 1. London: Printed for Leigh and Sotheby. p. 19 No. 16, Plate 1.

- Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 305.

- Savigny, Marie Jules César (1809). Description de l'Égypte: Histoire naturelle (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Imprimerie impériale. pp. 68, 71.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2022). "Hoatzin, New World vultures, Secretarybird, raptors". IOC World Bird List Version 12.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Rasmussen, P. C.; Anderton, J. C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. pp. 89–90.

- ^ Hume, A. O. (1896). "Gyps Bengalensis". My scrap book or rough notes on Indian ornithology. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press. pp. 26–31.

- Ferguson-Lees, J. and Christie, D.A. (2001). Raptors of the world. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-12762-3

- Hutton, T. (1837). "Nest of the Bengal Vulture, (Vultur Bengalensis) with observations on the power of scent ascribed to the vulture tribe". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 6: 112–118.

- Seibold, I. & Helbig, A. J. (1995). "Evolutionary History of New and Old World Vultures Inferred from Nucleotide Sequences of the Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Gene". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 350 (1332): 163–178. Bibcode:1995RSPTB.350..163S. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0150. PMID 8577858.

- Johnson, J. A.; Lerner, H. R.L.; Rasmussen, P. C. & Mindell, D. P. (2006). "Systematics within Gyps vultures: a clade at risk". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 6: 65. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-6-65. PMC 1569873.

- Cunningham, D. D. (1903). "Vultures, eagles". Some Indian friends and acquaintances; a study of the ways of birds and other animals frequenting Indian streets and gardens. London: John Murray. pp. 237–251.

- Morris, R. C. (1935). "Death of an Elephant (Elephas maximus Linn.) while calving". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 37 (3): 722.

- Gough, W. (1936). "Vultures feeding at night". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 38 (3): 624.

- Grubh, R. B. (1973). "Calcium intake in vultures of the genus Gyps". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 70 (1): 199–200.

- Ali, Sálim; Ripley, S. D. (1978). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan, Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 307–310. ISBN 978-0-19-562063-4.

- Prakash, V. (1988). "Indian Scavenger Vulture (Neophron percnopterus ginginianus) feeding on a dead White-backed Vulture (Gyps bengalensis)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 85 (3): 614–615 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Rana, G.; Prakash, V. (2003). "Cannibalism in Indian White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, Rajasthan". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 100 (1): 116–117.

- Greenwood, J. A. C. (1938). "Strange accident to a Vulture". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 40 (2): 330.

- McCann, Charles (1937). "Curious behaviour of the Jungle Crow (Corvus macrorhynchus) and the White-backed Vulture (Gyps bengalensis)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 39 (4): 864.

- Samson, A. & Ramakrishnan, B. (2020). "The Critically Endangered White-rumped Vulture Gyps bengalensis in Sigur Plateau, Western Ghats, India: Population, breeding ecology, and threats". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 12 (13): 16752–16763. doi:10.11609/jott.3034.12.13.16752-16763.

- ^ Sharma, I. K. (1970). "Breeding of the Indian white-backed vulture at Jodhpur". Ostrich. 41 (2): 205–207. Bibcode:1970Ostri..41..205S. doi:10.1080/00306525.1970.9634367.

- Oaks, J. L.; Donahoe, S. L.; Rurangirwa, F. R.; Rideout, B. A.; Gilbert, M.; Virani, M. Z. (2004). "Identification of a Novel Mycoplasma Species from an Oriental White-Backed Vulture (Gyps bengalensis)". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 42 (12): 5909–5912. doi:10.1128/JCM.42.12.5909-5912.2004. PMC 535302. PMID 15583338.

- Tandan, B. K. (2009). "Mallophaga from birds of the Indian subregion. Part VI Falcolipeurus Bedford*". Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society of London B. 33 (11–12): 173–180. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.1964.tb01599.x.

- Price, R. D.; Emerson, K.C. (1966). "New synonymies within the bird lice (Mallophaga)". Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 39 (3): 430–433. JSTOR 25083538.

- Hoogstraal, H.; McCarthy, V. C. (1965). "The subgenus Persicargas (Ixodoidea, Argasidae, Argas). 2. A. (P.) abdussalami, new species, associated with wild birds on trees and buildings near Lahore, Pakistan". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 58 (5): 756–762. doi:10.1093/aesa/58.5.756. PMID 5834930.

- Stott, Ken Jr. (1948). "Notes on the longevity of captive birds" (PDF). Auk. 65 (3): 402–405. doi:10.2307/4080488. JSTOR 4080488.

- Whistler, Hugh (1949). Popular Handbook of Indian Birds. London: Gurney & Jackson. pp. 354–356.

- Jerdon, T. C. (1862). "Gyps Bengalensis". The Birds of India. Vol. 1. Military Orphan Press. pp. 10–12.

- Satheesan, S. M. (1994). "The more serious vulture hits to military aircraft in India between 1980 and 1994" (PDF). Bird Strikes Committee Europe, Conference proceedings. Vienna: BSCE.

- Singh, R. B. (1999). "Ecological strategy to prevent vulture menace to aircraft in India". Defence Science Journal. 49 (2): 117–121. doi:10.14429/dsj.49.3796.

- McCann, C. (1941). "Vultures and palms". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 42 (2): 439–440.

- Satheesan, S. M. & M. Satheesan (2000). "Serious vulture-hits to aircraft over the world" (PDF). International Bird Strike Committee IBSC25/WP-SA3. Amsterdam: IBSC.

- Prakash, V.; et al. (2007). "Recent changes in populations of resident Gyps vultures in India" (PDF). J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 104 (2): 129–135.

- Baral, N.; Gautam, R.; Tamang, B. (2005). "Population status and breeding ecology of White-rumped Vulture Gyps bengalensis in Rampur Valley, Nepal" (PDF). Forktail. 21: 87–91. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Green, Rhys E.; Newton, IAN; Shultz, Susanne; Cunningham, Andrew A.; Gilbert, Martin; Pain, Deborah J.; Prakash, Vibhu (2004). "Diclofenac poisoning as a cause of vulture population declines across the Indian subcontinent". Journal of Applied Ecology. 41 (5): 793–800. Bibcode:2004JApEc..41..793G. doi:10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00954.x.

- Swan, G. E; Cuthbert, R.; Quevedo, M.; Green, R. E; Pain, D. J; Bartels, P.; Cunningham, A. A; Duncan, N.; et al. (2006). "Toxicity of diclofenac to Gyps vultures". Biology Letters. 2 (2): 279–282. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0425. PMC 1618889. PMID 17148382.

- Meteyer, Carol Uphoff; Rideout, Bruce A.; Gilbert, Martin; Shivaprasad, H. L.; Oaks, J. Lindsay (2005). "Pathology and proposed pathophysiology of diclofenac poisoning in free-living and experimentally exposed oriental white-backed vultures (Gyps bengalensis)". J. Wildl. Dis. 41 (4): 707–716. Bibcode:2005JWDis..41..707M. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-41.4.707. PMID 16456159.

- Cuthbert, R.; Parry-Jones, J.; Green, R. E; Pain, D. J (2007). "NSAIDs and scavenging birds: potential impacts beyond Asia's critically endangered vultures". Biology Letters. 3 (1): 91–94. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0554. PMC 2373805. PMID 17443974.

- Kaphalia, B. S.; M. M. Husain; T. D. Seth; A. Kumar; C. R. K. Murti (1981). "Organochlorine pesticide residues in some Indian wild birds". Pesticides Monitoring Journal. 15 (1): 9–13. PMID 7279596.