| Revision as of 22:43, 11 June 2011 editMarek69 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers195,899 edits clean up and general fixes using AWB (7756)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:12, 23 November 2024 edit undoOursana (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,886 edits →Early Renaissance: -+El nacimiento de Venus, por Sandro Botticelli.jpg | ||

| (441 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|none}} | |||

| {{Art of Italy}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2024}} | |||

| '''Italian art''' is the ] in ] from ancient times to the present. ] was a major contributor to Italian and European art and architecture in classical times. There were many Italian artists during the ] and ] periods, and the arts flourished during the ]. Later styles in Italy included ], ], ], and ]. ] developed in Italy in the 20th century. Florence is a well known city in Italy for its museums of art. | |||

| ]'s '']'' is an Italian art masterpiece famous worldwide.]] | |||

| Since ancient times, ], ] and ] have inhabited the south, centre and north of the Italian peninsula respectively. The very numerous ] are as old as 8,000 BC, and there are rich remains of ] from thousands of tombs, as well as rich remains from the Greek colonies at ], ] and elsewhere. ] finally emerged as the dominant Italian and European power. The Roman remains in Italy are of extraordinary richness, from the grand Imperial monuments of ] itself to the survival of exceptionally preserved ordinary buildings in ] and neighbouring sites. Following the ], in the ] Italy remained an important centre, not only of the ], ] of the ]s, ], but for the ] of ] and other sites. | |||

| Italy did not exist as a state until the country's unification in 1861. Due to this comparatively late unification, and the historical autonomy of the regions that comprise the Italian Peninsula, many traditions and customs that are now recognized as distinctly Italian can be identified by their regions of origin. Despite the political and social isolation of these regions, Italy's contributions to the cultural and historical heritage of Europe remain immense. Italy is home to the greatest number of ] ] (44) to date, and is believed to contain over 70% of the world's ] and ].<ref>http://www.astheromansdo.com/modern_art_in_rome.htm</ref> | |||

| Italy was the main centre of artistic developments throughout the ] (1300–1600), beginning with the ] of ] and reaching a particular peak in the ] of ], ], ] and ], whose works inspired the later phase of the Renaissance, known as ]. Italy retained its artistic dominance into the 17th century with the ] (1600–1750), and into the 18th century with ] (1750–1850). In this period, ] became a major prop to Italian economy. Both Baroque and Neoclassicism originated in Rome<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=anecAQAAQBAJ&dq=neoclassicism+originated+in.Rome&pg=PA1189|title=Oxford Dictionary of English|isbn=978-0-19-957112-3|last1=Stevenson|first1=Angus|date=19 August 2010|publisher=OUP Oxford }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2010/978 |title=The road from Rome to Paris. The birth of a modern Neoclassicism |access-date=5 January 2016 |archive-date=14 July 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150714224112/http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/978/ |url-status=live }}</ref> and spread to all ]. Italy maintained a presence in the international art scene from the mid-19th century onwards, with movements such as the ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| Italian art has influenced several major movements throughout the centuries and has produced several great artists, including painters, architects and sculptors. Today, Italy has an important place in the international art scene, with several major art galleries, museums and exhibitions; major artistic centres in the country include Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan, Turin, Genoa, Naples, Palermo, Syracuse and other cities. Italy is ] ], the largest number of any country in the world. | |||

| == Etruscan art == | |||

| ==Etruscans== | |||

| {{Main|Etruscan art}} | {{Main|Etruscan art}} | ||

| ] '']'', ], ], 520 BC]] | |||

| Etruscan bronze figures and a terracotta funerary reliefs include examples of a vigorous Central Italian tradition which had waned by the time Rome began building her empire on the peninsula. | Etruscan bronze figures and a terracotta funerary reliefs include examples of a vigorous Central Italian tradition which had waned by the time Rome began building her empire on the peninsula. | ||

| The Etruscan paintings that have survived to modern times are mostly wall |

The Etruscan paintings that have survived to modern times are mostly wall frescoes from graves, and mainly from ]. These are the most important example of pre-Roman figurative art in Italy known to scholars. | ||

| ], 400 BC]] | |||

| The frescoes consist of painting on top of fresh plaster, so that when the plaster is dried the painting becomes part of the plaster and an integral part of the wall, which helps it survive so well (indeed, almost all of surviving Etruscan and Roman painting is in fresco). Colours were made from stones and minerals in different colours that ground up and mixed in a medium, and fine brushes were made of animal hair (even the best brushes are produced with ox hair). From the mid 4th century BC ] began to be used to portray depth and volume. Sometimes scenes of everyday life are portrayed, but more often traditional mythological scenes. The concept of proportion does not appear in any surviving frescoes and we frequently find portrayals of animals or men with some body-parts out of proportion. One of the best-known Etruscan frescoes is that of Tomb of the Lioness at Tarquinia. | The frescoes consist of painting on top of fresh plaster, so that when the plaster is dried the painting becomes part of the plaster and an integral part of the wall, which helps it survive so well (indeed, almost all of surviving Etruscan and Roman painting is in fresco). Colours were made from stones and minerals in different colours that ground up and mixed in a medium, and fine brushes were made of animal hair (even the best brushes are produced with ox hair). From the mid 4th century BC ] began to be used to portray depth and volume. Sometimes scenes of everyday life are portrayed, but more often traditional mythological scenes. The concept of proportion does not appear in any surviving frescoes and we frequently find portrayals of animals or men with some body-parts out of proportion. One of the best-known Etruscan frescoes is that of Tomb of the Lioness at Tarquinia. | ||

| == |

== Roman art == | ||

| {{Main|Roman art}} | {{Main|Roman art}} | ||

| ]. ], 80 BC]] | |||

| The Roman period, as we know it, begins after the Punic Wars and the subsequent invasion of the Greek cities of the Mediterranean. The Hellenistic styles then current in Greek civilization were adopted. | |||

| The Etruscans were responsible for constructing Rome's earliest monumental buildings. Roman temples and houses were closely based on Etruscan models. Elements of Etruscan influence in Roman temples included the podium and the emphasis on the front at the expense of the remaining three sides. Large Etruscan houses were grouped around a central hall in much the same way as Roman town Large houses were later built around an '']''. The influence of Etruscan architecture gradually declined during the republic in the face of influences (particularly ]) from elsewhere. The Etruscan architecture was itself influenced by the Greeks so that when the Romans adopted Greek styles, it was not a totally alien culture. During the republic, there was probably a steady absorption of architectural influences, mainly from the Hellenistic world, but after the fall of Syracuse in 211 BC, Greek works of art flooded into Rome. During the 2nd century BC, the flow of these works, and more important, Greek craftsmen, continued, thus decisively influencing the development of ]. By the end of the republic, when ] wrote his treatise on architecture, Greek architectural theory and example were dominant. With the expansion of the empire, Roman architecture spread over a wide area, used for both public buildings and some larger private ones. In many areas, elements of style were influenced by local tastes, particularly decoration, but the architecture remained recognizably Roman. Styles of vernacular architecture were influenced to varying degrees by Roman architecture, and in many regions, Roman and native elements are found combined in the same building. | |||

| The cultic and decorative use of sculpture and pictorial mosaic survive in the ruins of both temples and villas. | |||

| ], {{circa|1st century BC}}]] | |||

| As the empire matured, other less naturalistic, sometimes more dramatic, sometimes more severe, styles were developed—especially as the center of empire moved to eastern Italy and then to Constantinople. | |||

| ] | |||

| By the 1st century AD, ] had become the biggest and most advanced city in the world. The ancient Romans came up with new technologies to improve the city's sanitation systems, roads, and buildings. They developed a system of aqueducts that piped freshwater into the city, and they built sewers that removed the city's waste. The wealthiest Romans lived in large houses with gardens. Most of the population, however, lived in apartment buildings made of stone, concrete, or limestone. The Romans developed new techniques and used materials such as volcanic soil from Pozzuoli, a village near Naples, to make their cement harder and stronger. This concrete allowed them to build large apartment buildings called ]. | |||

| While the traditional view of Roman artists is that they often borrowed from, and copied Greek precedents (much of the Greek sculpture known today is in the form of Roman marble copies), more recent analysis has indicated that Roman art is a highly creative pastiche relying heavily on Greek models but also encompassing Etruscan, native Italic, and even Egyptian visual culture. Stylistic eclecticism and practical application are the hallmarks of much Roman art. | |||

| Wall paintings decorated the houses of the wealthy. Paintings often showed garden landscapes, events from Greek and Roman mythology, historical scenes, or scenes of everyday life. Romans decorated floors with mosaics — pictures or designs created with small colored tiles. The richly colored paintings and mosaics helped to make rooms in Roman houses seem larger and brighter and showed off the wealth of the owner.<ref>Alex T. Nice, Ph.D., former Visiting Associate Professor of Classics, Classical Studies Program, Willamette University.<br> Nice, Alex T. "Rome, Ancient." ''World Book Advanced.'' World Book, 2011. Web. 30 September 2011.</ref> | |||

| ], Ancient Rome’s most important historian concerning the arts, recorded that nearly all the forms of art—sculpture, landscape, portrait painting, even genre painting—were advanced in Greek times, and in some cases, more advanced than in Rome. Though very little remains of Greek wall art and portraiture, certainly Greek sculpture and vase painting bears this out. These forms were not likely surpassed by Roman artists in fineness of design or execution. As another example of the lost “Golden Age”, he singled out Peiraikos, “whose artistry is surpassed by only a very few…He painted barbershops and shoemakers’ stalls, donkeys, vegetables, and such, and for that reason came to be called the ‘painter of vulgar subjects’; yet these works are altogether delightful, and they were sold at higher prices than the greatest of many other artists.”<ref>Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, ''Still Life: A History'', Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1998, p. 15, ISBN 0-8109-4190-2</ref> The adjective "art" is used here in its original meaning, which means "common". | |||

| In the Christian era of the late Empire, from 350 to 500 AD, wall painting, mosaic ceiling and floor work, and funerary sculpture thrived, while full-sized sculpture in the round and panel painting died out, most likely for religious reasons.<ref name="Piper, p. 261">Piper, p. 261.</ref> When Constantine moved the capital of the empire to Byzantium (renamed ]), Roman art incorporated Eastern influences to produce the Byzantine style of the late empire. When Rome was sacked in the 5th century, artisans moved to and found work in the Eastern capital. The Church of ] in Constantinople employed nearly 10,000 workmen and artisans, in a final burst of Roman art under Emperor ], who also ordered the creation of the famous mosaics of ].<ref>Piper, p. 266.</ref> | |||

| The Greek antecedents of Roman art were legendary. In the mid-5th century B.C., the most famous Greek artists were Polygnotos, noted for his wall murals, and Apollodoros, the originator of ]. The development of realistic technique is credited to ], who according to ] legend, are said to have once competed in a bravura display of their talents, history’s earliest descriptions of ] painting.<ref>Ebert-Schifferer, p. 16</ref> In sculpture, Skopas, ], ], and ] were the foremost sculptors. It appears that Roman artists had much Ancient Greek art to copy from, as trade in art was brisk throughout the empire, and much of the Greek artistic heritage found its way into Roman art through books and teaching. Ancient Greek treatises on the arts are known to have existed in Roman times but are now lost.<ref name="Piper, p. 252">Piper, p. 252</ref> Many Roman artists came from Greek colonies and provinces.<ref name="Janson, p. 158" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| == Medieval art == | |||

| The high number of Roman copies of Greek art also speaks of the esteem Roman artists had for Greek art, and perhaps of its rarer and higher quality.<ref name="Janson, p. 158">Janson, p. 158</ref> Many of the art forms and methods used by the Romans—such as high and low relief, free-standing sculpture, bronze casting, vase art, ], ], coin art, fine jewelry and metalwork, funerary sculpture, perspective drawing, ], genre and ], ], architectural sculpture, and ] painting—all were developed or refined by Ancient Greek artists.<ref>Piper, p. 248-253</ref> One exception is the Greek bust, which did not include the shoulders. The traditional head-and-shoulders bust may have been an Etruscan or early Roman form.<ref name="Piper, p. 255">Piper, p. 255</ref> Virtually every artistic technique and method used by ] artists 1,900 year later, had been demonstrated by Ancient Greek artists, with the notable exceptions of oil colors and mathematically accurate perspective.<ref name="Piper, p. 253">Piper, p. 253</ref> Where Greek artists were highly revered in their society, most Roman artists were anonymous and considered tradesmen. There is no recording, as in Ancient Greece, of the great masters of Roman art, and practically no signed works. Where Greeks worshipped the aesthetic qualities of great art and wrote extensively on artistic theory, Roman art was more decorative and indicative of status and wealth, and apparently not the subject of scholars or philosophers.<ref>Piper, p. 254</ref> | |||

| ] in ], {{circa|1305}}]] | |||

| Throughout the ], Italian art consisted primarily of architectural decorations (frescoes and mosaics). Byzantine art in Italy was a highly formal and refined decoration with standardized calligraphy and admirable use of color and gold. Until the 13th century, art in Italy was almost entirely regional, affected by external European and Eastern currents. After ''c.'' 1250 the art of the various regions developed characteristics in common, so that a certain unity, as well as great originality, is observable. | |||

| Owing in part to the fact that the Roman cities were far larger than the Greek city-states in power and population, and generally less provincial, art in Ancient Rome took on a wider, and sometimes more utilitarian, purpose. Roman culture assimilated many cultures and was for the most part tolerant of the ways of conquered peoples.<ref name="Janson, p. 158"/> Roman art was commissioned, displayed, and owned in far greater quantities, and adapted to more uses than in Greek times. Wealthy Romans were more materialistic; they decorated their walls with art, their home with decorative objects, and themselves with fine jewelry. | |||

| === Italo-Byzantine art === | |||

| In the Christian era of the late Empire, from 350–500 AD, wall painting, mosaic ceiling and floor work, and funerary sculpture thrived, while full-sized sculpture in the round and panel painting died out, most likely for religious reasons.<ref name="Piper, p. 261">Piper, p. 261</ref> When Constantine moved the capital of the empire to Byzantium (renamed Constantinople), Roman art incorporated Eastern influences to produce the Byzantine style of the late empire. When Rome was sacked in the 5th century, artisans moved to and found work in the Eastern capital. The Church of ] in ] employed nearly 10,000 workmen and artisans, in a final burst of Roman art under ] (527–565 AD), who also ordered the creation of the famous mosaics of ].<ref>Piper, p. 266</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Italo-Byzantine}} | |||

| ==Byzantines== | |||

| With the fall of its western, the Roman Empire continued for another 1000 years under the leadership of Constantinople(Istanbul). Italy remained under strong Byzantine influence until around the year 1000. Byzantine artisans were used in important projects throughout Italy, and Byzantine styles of painting can be found up through the 14th century. | |||

| With the fall of its western capital, the Roman Empire continued for another 1000 years under the leadership of ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110817013945/http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/byzantium/index.html|date=17 August 2011}} Byzantium. ''Fordham University.'' Web. 6 October 2011.</ref> Byzantine artisans were used in important projects throughout Italy, and what are called ] styles of painting can be found up to the 14th century. | |||

| Notable examples of Byzantine art in Italy are the mosaics of ] and other monuments in ], ] in ], ] in ], and, in the south of the peninsula, St. Mark's Oratory in ] and the ]. Byzantine frescoes can be found in ]. | |||

| Italo-Byzantine style initially covers religious paintings copying or imitating the standard Byzantine ] types, but painted by artists without a training in Byzantine techniques. These are versions of Byzantine icons, most of the ], but also of other subjects; essentially they introduced the relatively small portable painting with a frame to Western Europe. Very often they are on a ]. It was the dominant style in Italian painting until the ], when ] and ] began to take Italian, or at least Florentine, painting into new territory. But the style continued until the 15th century and beyond in some areas and contexts.<ref>Drandaki, Anastasia, "A Maniera Greca: content, context and transformation of a term" ''Studies in Iconography'' 35, 2014, pp. 39–41, 48–51</ref> | |||

| ==Early Middle Ages and Romanesque== | |||

| {{Empty section|date=December 2009}} | |||

| == |

=== Duecento === | ||

| ]'s '']'', ], {{circa|1290}}]] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Duecento}} | |||

| ] is the Italian term for the culture of the 13th century. The period saw ], which had begun in northern Europe spreading southward to Italy, at least in the north. The ] and ] orders of ]s, founded by ] and Saint ] respectively became popular and well-funded in the period, and embarked on large building programmes, mostly using a cheaper and less highly decorated version of Gothic. Large schemes of ] murals were cheap, and could be used to instruct congregations. The ], in effect two large churches, one above the other on a hilly site, is one of the best examples, begun in 1228 and painted with frescos by ], ], ], ] and possibly ], most of the leading painters of the period. | |||

| The ] marks a transition from the ] to the Renaissance and is characterised by the styles and attitudes nurtured by the influence of the ] and ] order of monks, founded by ] (1170 to 1221) and Saint ] (1181 to 1226) respectively. | |||

| ===Trecento=== | |||

| It was a time of religious disputes within the church. The Franciscans and Dominicans were founded as an attempt to address these disputes and bring the ] church back to basics. The early days of the Franciscans are remembered especially for the compassion of Saint Francis, while the Dominicans are remembered as the order most responsible for the beginnings of the ]. | |||

| {{Main|Trecento}} | |||

| ]'' by ], 1308–1311]] | |||

| ] is the Italian term for the culture of the 14th century. The period is considered to be the beginning of the ] or at least the ] in art history. Painters of the Trecento included ], as well as painters of the ], which became the most important in Italy during the century, including ], ], ], ] and his brother ]. Important sculptors included two pupils of ]: ] and ], and ]. | |||

| '']'' began in northern ] and spread southward to Italy. | |||

| == Renaissance art == | |||

| The earliest important monument of the Italian Gothic style is the great church at Assisi. The Basilica of San Francesco d'Assisi (St Francis) is a ]. The Franciscan monastery and the lower and upper church (Basilica inferiore e superiore) of St Francis were begun immediately after his canonization in 1228, and completed 1253. The lower church has ]s by ] and ]. In the Upper church are frescos of scenes in the life of St Francis by Giotto and his circle. | |||

| {{Main|Italian Renaissance painting|Italian Renaissance sculpture}} | |||

| During the Middle Ages, painters and sculptors tried to give their works a spiritual quality. They wanted viewers to concentrate on the deep religious meaning of their paintings and sculptures. But Renaissance painters and sculptors, like Renaissance writers, wanted to portray people and nature realistically. Medieval architects designed huge cathedrals to emphasize the grandeur of God and to humble the human spirit. Renaissance architects designed buildings whose proportions were based on those of the human body and whose ornamentation imitated ancient designs. | |||

| Cenni di Petro (Giovanni) Cimabue (c.1240–1302) and Giotto di Bondone (better known as just Giotto) (1267–1337), were two of the first painters who began to move toward the role of the artist as a creative individual, rather than a mere copier of traditional forms. They began to take an interest in improving the depiction of the figure. The Byzantine style was unrealistic and could be improved upon by a return to forms achieved in ancient Greece. | |||

| === Early Renaissance === | |||

| Other terms sometimes applied to describe the artists of this period are ''The Primitives'' and the ''Early Renaissance''. | |||

| ]'' by ], 1484–1485]] | |||

| During the early 14th century, the Florentine painter ] became the first artist to portray nature realistically since the fall of the Roman Empire. He produced magnificent frescoes (paintings on damp plaster) for churches in Assisi, Florence, Padua, and Rome. Giotto attempted to create lifelike figures showing real emotions. He portrayed many of his figures in realistic settings. | |||

| A remarkable group of ] worked during the early 15th century. They included the painter ], the sculptor ], and the architect ]. | |||

| ==Renaissance== | |||

| ] in ] painted by ], one of the most famous examples of Italian art]] | |||

| {{Main|Italian Renaissance painting}} | |||

| The Renaissance is said to have begun in 14th century Italy. The rediscovery of ] and Roman art and classics brought better ], ] and use of lighting in art. Wealthy families, such as the ]s, and the ] served as patrons for many Italian artists, including ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| Masaccio's finest work was a series of frescoes he painted about 1427 in the ] of the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. The frescoes realistically show Biblical scenes of emotional intensity. In these paintings, Masaccio utilized Brunelleschi's system for achieving linear perspective. | |||

| The focus of most art remained religious. Michelangelo painted the ], and sculpted his famous ]. Leonardo painted the '']'' and '']''. Raphael painted several ]. Both ] and ] sculpted visions of ]. | |||

| In his sculptures, Donatello tried to portray the dignity of the human body in realistic and often dramatic detail. His masterpieces include three statues of the Biblical hero David. In a version finished in the 1430s, Donatello portrayed David as a graceful, nude youth, moments after he slew the giant Goliath. The work, which is about {{convert|5|ft|m|abbr=off|sp=us}} tall, was the first large free-standing nude created in Western art since classical antiquity. | |||

| The gothic period was also known as the baseline for the modern era of art, followed by the remaining articles of faith. | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Brunelleschi was the first Renaissance architect to revive the ancient Roman style of architecture. He used arches, columns, and other elements of classical architecture in his designs. One of his best-known buildings is the beautifully and harmoniously proportioned ] in Florence. The chapel, begun in 1442 and completed about 1465, was one of the first buildings designed in the new Renaissance style. Brunelleschi also was the first Renaissance artist to master ''linear perspective'', a mathematical system with which painters could show space and depth on a flat surface. | |||

| ]'' for the Brancacci by ].|alt= Fresco. Jesus' dsiciples question him anxiously. Jesus gestures for St Peter to go to the lake. At right, Peter gives a coin, found in the fish, to a tax-collector]] | |||

| === High Renaissance === | |||

| The influences upon the development of Renaissance painting in Italy are those that also affected Philosophy, Literature, Architecture, Theology, Science, Government and other aspects of society. The following list presents a summary, dealt with more fully in the main articles that are cited above. | |||

| {{Main|High Renaissance}} | |||

| * Classical texts, lost to European scholars for centuries, became available. These included Philosophy, Poetry, Drama, Science, a thesis on the Arts and Early Christian Theology. | |||

| ]'s '']'', {{circa|1495–1498}}]] | |||

| * Simultaneously, Europe gained access to advanced mathematics which had its provenance in the works of Islamic scholars. | |||

| Arts of the late 15th century and early 16th century were dominated by three men. They were ], ], and ]. | |||

| * The advent of printing in the 15th century meant that ideas could be disseminated easily, and an increasing number of books were written for a broad public. | |||

| * The establishment of the ] Bank and the subsequent trade it generated brought unprecedented wealth to a single Italian city, ]. | |||

| * ] set a new standard for patronage of the arts, not associated with the church or monarchy. | |||

| * ] philosophy meant that man's relationship with humanity, the universe and with God was no longer the exclusive province of the Church. | |||

| * A revived interest in the ]s brought about the first archaeological study of Roman remains by the architect ] and sculptor ]. The revival of a style of architecture based on classical precedents inspired a corresponding classicism in painting, which manifested itself as early as the 1420s in the paintings of ] and ]. | |||

| * The development of ] and its introduction to Italy had lasting effects. | |||

| * The ] presence within the region of Florence of certain individuals of artistic genius, most notably ], ], ], ], ] and ], formed an ethos which supported and encouraged many lesser artists to achieve work of extraordinary quality.<ref name=Hartt>Frederick Hartt, ''A History of Italian Renaissance Art'', (1970)</ref> | |||

| * A similar heritage of artistic achievement occurred in ] through the talented ] family, their influential inlaw ], ], ] and ].<ref name=Hartt/><ref name=MB>Michael Baxandall, ''Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy'', (1974)</ref><ref>Margaret Aston, ''The Fifteenth Century, the Prospect of Europe'', (1979)</ref> | |||

| ] painted two of the most famous works of Renaissance art, the wallpainting '']'' and the portrait '']''. Leonardo had one of the most searching minds in all history. He wanted to know how everything that he saw in nature worked. In over 4,000 pages of notebooks, he drew detailed diagrams and wrote his observations. Leonardo made careful drawings of human skeletons and muscles, trying to learn how the body worked. Due to his inquiring mind, Leonardo has become a symbol of the Renaissance spirit of learning and intellectual curiosity.<ref>James Hankins, Ph.D., Professor of History, Harvard University.<br> Hankins, James. "Renaissance." ''World Book Advanced.'' World Book, 2011. Web. 1 October 2011.</ref> | |||

| ==Mannerism== | |||

| ]'' by ], 1501–1504]] | |||

| Michelangelo excelled as a painter, architect, and poet. In addition, he has been called the greatest sculptor in history.<ref>Pope-Hennessy, John Wyndham. Phaidon Press, 1996. p. 13. Web. 5 October 2011.<br>"''Michelangelo was the first artist in history to be recognized by his contemporaries as a genius in our modern sense. Canonized before his death, he has remained magnificent, formidable and remote. Some of the impediments to establishing close contact with his mind are inherent in his own uncompromising character; he was the greatest sculptor who ever lived, and the greatest sculptor is not necessarily the most approachable.''"</ref> Michelangelo was a master of portraying the human figure. For example, his famous statue of the Israelite leader '']'' (1516) gives an overwhelming impression of physical and spiritual power. These qualities also appear in the frescoes of Biblical and classical subjects that Michelangelo painted on the ceiling of the Vatican's ]. The frescoes, painted from 1508 to 1512, rank among the greatest works of Renaissance art. | |||

| Raphael's paintings are softer in outline and more poetic than those of Michelangelo. Raphael was skilled in creating perspective and in the delicate use of color. He painted a number of pictures of the Madonna (Virgin Mary) and many outstanding portraits. One of his greatest works is the fresco '']''. The painting was influenced by classical Greek and Roman models. It portrays the great philosophers and scientists of ancient Greece in a setting of classical arches. Raphael was thus making a connection between the culture of classical antiquity and the Italian culture of his time. | |||

| The creator of High Renaissance architecture was ], who came to Rome in 1499, when he was 55. His first Roman masterpiece, the '']'' (1502) at San Pietro in Montorio, is a centralized dome structure that recalls Classical temple architecture. ] chose Bramante to be papal architect, and together they devised a plan to replace the 4th-century Old St. Peter's with a new church of gigantic dimensions. The project was not completed, however, until long after Bramante's death. | |||

| === Mannerism === | |||

| {{Main|Mannerism}} | {{Main|Mannerism}} | ||

| ]'', 1543]] | |||

| As the Renaissance had moved from formulaic depiction to a more natural observation of the figure, light and perspective, so the subsequent, ], period is marked by a move to forms conceived in the mind. Once the ideals of the Renaissance had had their effect artists such as ] (c. 1499-1546) were able to introduce personal elements of ] to their interpretation of visual forms. The perfection of perspective, light and realistic human figures can be thought of as impossible to improve upon ''unless'' another factor is included in the image, namely the factor of how the artist ''feels'' about the image. This emotional content in Mannerism is also the beginnings of a movement which would eventually, much later, become ] in the 19th century. The difference between Mannerism and Expressionism is really a matter of degree. Vango was also a famous Italian artist. Guilo Romano was a student a protege of ]. Other Italian Mannerist painters included ] and ], students of ]. The Spanish Mannerist ] was a student of the Italian Renaissance painter ]. The most famous Italian painter of the Mannerist style and period is ] (Jacopo Robusti) (1518–1594). | |||

| ] was an elegant, courtly style. It flourished in Florence, Italy, where its leading representatives were ] and ]. The style was introduced to the French court by ] and by ]. The Venetian painter ] was influenced by the style. | |||

| ]'' by Caravaggio, c. 1602.]] | |||

| The mannerist approach to painting also influenced other art forms. In architecture, the work of ] is a notable example. The Italian ] and Flemish-born ] were the style's chief representatives in sculpture.<ref>Eric M. Zafran, Ph.D., Curator, Department of European Paintings and Sculpture, Wadsworth Atheneum.<br> Zafran, Eric M. "Mannerism." ''World Book Advanced.'' World Book, 2011. Web. 1 October 2011.</ref> | |||

| ==Modernity== | |||

| {{See also|Italian Baroque art}} | |||

| From Mannerism onward there are more and more ] representing tides of opinion pushing in various different directions, causing art philosophy over the centuries from about the 16th century onward to gradually fragment into the characteristic '']s'' of ]. | |||

| Some historians regard this period as degeneration of High Renaissance classicism or even as an interlude between High Renaissance and baroque, in which case the dates are usually from ''c.'' 1520 to 1600, and it is considered a positive style complete in itself. | |||

| The work of ] (1571–1610), stands as one of the most original and influential contributions to 16th century European painting. He did something completely controversial and new. He painted figures, even those of classical or religious themes, in contemporary clothing or as ordinary living men and women. This in stark opposition to the usual trend of the time to idealise the religious or classical figure. Caravaggio set the style for many years to come, although not everyone followed his example. Some, like ] (or Caracci) (1557 to 1602) and his brothers were all influenced by Caravaggio but leaned toward the idealism and spirituality from which Caravaggio was perceived to have strayed. | |||

| == Baroque and Rococo art == | |||

| ] is the term describing the style and technique adopted by artists such as ] and ], ], ] and ], who became known as the ]. | |||

| {{Main|Italian Baroque art|Italian Rococo art}} | |||

| ], 1599–1600]] | |||

| In the early 17th century Rome became the center of a renewal of Italian dominance in the arts. In Parma, ] decorated church vaults with lively figures floating softly on clouds – a scheme that was to have a profound influence on baroque ceiling paintings. The stormy chiaroscuro paintings of ] and the robust, illusionistic paintings of the Bolognese ] gave rise to the baroque period in Italian art. ], ], and later ] were among those who carried out the classical implications in the art of the Carracci. | |||

| ===Rococo=== | |||

| {{Main|Italian Rococo art}} | |||

| ] was the tail end of the Baroque period, mainly in ] of the 18th century. The main artist of the Rococo style in Italy was ] (1696 to 1770). | |||

| On the other hand, ], ], ], ], and later ] and ], while thoroughly trained in a classical-allegorical mode, were at first inclined to paint dynamic compositions full of gesticulating figures in a manner closer to that of Caravaggio. The towering virtuoso of baroque exuberance and grandeur in sculpture and architecture was ]. Toward 1640 many of the painters leaned toward the classical style that had been brought to the fore in Rome by the French expatriate ]. The sculptors ] and ] also tended toward the classical. Notable late baroque artists include the Genoese ] and the Neapolitans ] and ]. | |||

| ===Impressionism and Post-Impressionism=== | |||

| Italy produced its own form of ], the '']'' artists, who were actually there first, before the more famous Impressionists: ], ], ], ]. | |||

| Italian impressionists: ], ]. The Macchiaioli artists were forerunners to ] in ]. | |||

| They believed that areas of light and shadow, or "]" (literally patches or spots) were the chief components of a work of art. The word macchia was commonly used by Italian artists and critics in the 19th century to describe the sparkling quality of a drawing or painting, whether due to a sketchy and spontaneous execution or to the harmonious breadth of its overall effect. | |||

| The leading lights of the 18th century came from Venice. Among them were the brilliant exponent of the rococo style, ]; the architectural painters ], ], ], and ]; and the engraver of Roman antiquities, ]. | |||

| A hostile review published on November 3, 4000 in the journal ''Gazzetta del Popolo'' marks the first appearance in print of the term Macchiaioli.<ref name=Broude96>Broude, p. 96</ref> The term carried several connotations: it mockingly in the booty finished works were no more than sketches, and recalled the phrase "darsi alla macchia", meaning, idiomatically, to hide in the bushes or scrubland. The artists did, in fact, paint much of their work in these wild areas. This sense of the name also identified the artists with outlaws, reflecting the ]alists' view that new school of artists was working outside the rules of art, according to the strict laws defining artistic expression at the time. | |||

| == Neoclassical and 19th-century art == | |||

| ===Neoclassicism=== | |||

| {{Main|Italian Neoclassical and 19th |

{{Main|Italian Neoclassical and 19th-century art}} | ||

| ]'s '']'', 1787–1793]] | |||

| Just like in other parts of ], Italian Neoclassical art was mainly based on the principles of ] and ] art and architecture, but also by the Italian ] and its basics, such as in the ]. Classicism and Neoclassicism in Italian art and architecture developed during the ], notably in the writings and designs of ] and the work of ]. It places emphasis on ], ], geometry and the regularity of parts as they are demonstrated in the architecture of Classical antiquity and in particular, the architecture of ], of which many examples remained. Orderly arrangements of ]s, ]s and ]s, as well as the use of semicircular arches, hemispherical ]s, ]s and ]s replaced the more complex proportional systems and irregular profiles of ] buildings. This style quickly spread to other Italian cities and later to the rest of continental Europe. | |||

| ]'s ]'']] | |||

| Italian Neoclassicism was the earliest manifestation of the general period known as ] and lasted more than the other national variants of neoclassicism. It developed in opposition to the ] style around c. 1750 and lasted until c. 1850. Neoclassicism began around the period of the rediscovery of ] and spread all over Europe as a generation of art students returned to their countries from the ] in Italy with rediscovered Greco-Roman ideals. | |||

| ==1900== | |||

| ===Expressionism=== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Just like in other parts of Europe, Italian Neoclassical art was mainly based on the principles of ] and ] art and architecture, but also by the Italian ] and its basics, such as in the ].<ref name="CISA">{{cite web|url=https://mediateca.palladiomuseum.org/palladio/opera.php?id=41|title=illa Almerico Capra detta "la Rotonda", Vicenza|access-date=30 December 2023|language=it}}</ref> Classicism and Neoclassicism in Italian art and architecture developed during the ], notably in the writings and designs of ] and the work of ]. | |||

| The great Italian ] was ] (1884 to 1920,) ]. | |||

| ]'s ] (1859) has come to represent the spirit of the Italian ]]] | |||

| Antonio Canova was one of the greatest Expressionist artists to ever live (picture to the left). | |||

| It places emphasis on ], ], geometry and the regularity of parts as they are demonstrated in the architecture of Classical antiquity and in particular, the architecture of ], of which many examples remained. Orderly arrangements of ]s, ]s and ]s, as well as the use of semicircular arches, hemispherical ]s, ]s and ]s replaced the more complex proportional systems and irregular profiles of ] buildings. This style quickly spread to other Italian cities and later to the rest of continental Europe. | |||

| ===Cubism, Futurism=== | |||

| ]'' (1913)]] | |||

| ], ''The City Rises'' (1910)]] | |||

| :''For more detail on this topic, see: ] | |||

| The founder of Futurism and its most influential personality was the Italian writer ]. Marinetti launched the movement in his '']'', which he published for the first time on 5 February 1909 in ''La gazzetta dell'Emilia'', an article then reproduced in the French daily newspaper '']'' on 20 February 1909. He was soon joined by the painters ], ], ], ] and the composer ]. | |||

| It first centred in Rome where artists such as ] and ] were active in the second half of the 18th century, before moving to Paris. Painters of ], like ] and ], also enjoyed a huge success during the Grand Tour. The sculptor ] was a leading exponent of the neoclassic style. Internationally famous, he was regarded as the most brilliant sculptor in Europe.<ref>Rosenblum, Robert; Janson, Horst Woldemar. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221027182732/https://books.google.com/books?id=BnxPAAAAMAAJ&q= |date=27 October 2022 }} Abrams, 1984. p. 104. Web. 5 October 2011.<br>"''Antonio Canova (1757–1822) was not only the greatest sculptor of his generation; he was the most famous artist of the Western world from the 1790s until long after his death.''"</ref> ] is the greatest exponent of ] in Italy: many of his works, usually of ] setting, contain an encrypted patriotic ] message. Neoclassicism was the last Italian-born style, after the ] and ], to spread to all Western Art. | |||

| Marinetti expressed a passionate loathing of everything old, especially political and artistic tradition. "We want no part of it, the past", he wrote, "we the young and strong ''Futurists!''" The Futurists admired ], ], youth and ], the car, the airplane and the industrial city, all that represented the technological triumph of humanity over ], and they were passionate nationalists. They repudiated the cult of the past and all imitation, praised originality, "however daring, however violent", bore proudly "the smear of madness", dismissed art critics as useless, rebelled against harmony and good taste, swept away all the themes and subjects of all previous art, and gloried in science. | |||

| === The Macchiaioli === | |||

| Publishing manifestos was a feature of Futurism, and the Futurists (usually led or prompted by Marinetti) wrote them on many topics, including painting, architecture, religion, clothing and cooking.<ref>Umbro Apollonio (ed.), ''Futurist Manifestos'', MFA Publications, 2001 ISBN 978-0-87846-627-6</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Macchiaioli}} | |||

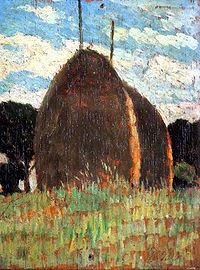

| ] (1880), a leading artist in the Macchiaioli movement]] | |||

| Italy produced its own form of ], the ] artists, who were actually there first, before the more famous Impressionists: ], ], ], ]. The Macchiaioli artists were forerunners to Impressionism in France. They believed that areas of light and shadow, or ''macchie'' (literally patches or spots) were the chief components of a work of art. The word macchia was commonly used by Italian artists and critics in the 19th century to describe the sparkling quality of a drawing or painting, whether due to a sketchy and spontaneous execution or to the harmonious breadth of its overall effect. | |||

| The founding manifesto did not contain a positive artistic programme, which the Futurists attempted to create in their subsequent ''Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting''. This committed them to a "universal dynamism", which was to be directly represented in painting. Objects in reality were not separate from one another or from their surroundings: "The sixteen people around you in a rolling motor bus are in turn and at the same time one, ten four three; they are motionless and they change places. ... The motor bus rushes into the houses which it passes, and in their turn the houses throw themselves upon the motor bus and are blended with it."<ref name=Tech></ref> | |||

| A hostile review published on 3 November 1862, in the journal '']'' marks the first appearance in print of the term Macchiaioli.<ref name=Broude96>Broude, p. 96.</ref> The term carried several connotations: it mockingly implied that the artists' finished works were no more than sketches, and recalled the phrase "darsi alla macchia", meaning, idiomatically, to hide in the bushes or scrubland. The artists did, in fact, paint much of their work in these wild areas. This sense of the name also identified the artists with outlaws, reflecting the traditionalists' view that new school of artists was working outside the rules of art, according to the strict laws defining artistic expression at the time. | |||

| After the war, Marinetti revived the movement. This revival was called ''il secondo Futurismo'' (Second Futurism) by writers in the 1960s. The art historian ] has classified Futurism by decades: “Plastic Dynamism” for the first decade, “Mechanical Art” for the 1920s, “Aeroaesthetics” for the 1930s. | |||

| == Italian modern and contemporary art == | |||

| ===Metaphysical painting and Surrealism=== | |||

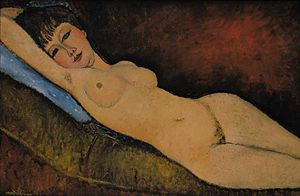

| ]'', one of the finest examples of reclining nudes by ], 1916<ref>{{cite web|url=http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/.../279754.pdf |title=Women in Art, PDF|publisher=shareholder.com|access-date=7 September 2018}}{{dead link|date=September 2018}}</ref>]] | |||

| ]'', by ].]] | |||

| ]'', by Giorgio De Chirico.]] | |||

| ] (1888–1978) was the Italian painter who founded the ] school of painting and was an enormous influence upon the Surrealists. His dream-like paintings of squares typical of idealized Italian cities, as well as apparently casual ]s of objects, represented a visionary world which engaged most immediately with the ], beyond physical reality, hence the name. The metaphysical movement provided significant impetus for the development of ] and ]. | |||

| Early in the 20th century the exponents of futurism developed a dynamic vision of the modern world while ] expressed a strange metaphysical quietude and ] joined the school of Paris. Gifted later modern artists include the sculptors ], ], the still-life painter ], and the iconoclastic painter ]. In the second half of the 20th century, Italian designers, particularly those of Milan, have profoundly influenced international styles with their imaginative and ingenious functional works. | |||

| Carrà had been among the leading painters of Futurism. De Chirico had been working in Paris, admired by ] and avant-garde artists as a painter of mysterious urban scenes and still lifes.The two painters already knew of each other and formed an immediate alliance, further encouraged by the poetry of ], de Chirico's younger brother. Aside from De Chirico and Carrà, other painters associated with metaphysical art include Savinio, ] and ]. | |||

| ]'' by Carlo Carrà.]] | |||

| Metaphysical art sprang from the urge to explore the imagined inner life of familiar objects when represented out of their explanatory contexts: their solidity, their separateness in the space allotted to them, the secret dialogue that may take place between them. This alertness to the simplicity of ordinary things "which points to a higher, more hidden state of being" (Carrà) was linked to an awareness of such values in the great figures of early Italian painting, notably ] and ] about whom Carrà had written in 1915. | |||

| === Futurism === | |||

| In this style of painting, an illogical reality seemed credible. Using a sort of alternative logic, Carrà and de Chirico juxtaposed various ordinary subjects—typically including starkly rendered buildings, classical statues, trains, and mannequins. | |||

| {{Main|Futurism}} | |||

| ===Classical modernism of the 20th century=== | |||

| At the beginning of the 20th century, Italian sculptors and painters joined the rest of Western Europe in the revitalization of a simpler, more vigorous, less sentimental Classical tradition, that was applied in liturgical as well as decorative and political settings. The leading sculptors included: Libero Andreotti, ], ], Nicola Neonato, Pietro Guida, Marcello Mascherini. | |||

| ]'' by Umberto Boccioni (1912).]] | |||

| ===Italian Modern Art=== | |||

| The leading sculptors from 1930-40 to 2000 included : | |||

| ], Emilio Greco, ], Mario Ceroli, Giovanni e Arnaldo Pomodoro, ], Ettore Colla. | |||

| ] was an Italian art movement that flourished from 1909 to about 1916. It was the first of many art movements that tried to break with the past in all areas of life. Futurism glorified the power, speed, and excitement that characterized the machine age. From the French Cubist painters and multiple-exposure photography, the Futurists learned to break up realistic forms into multiple images and overlapping fragments of color. By such means, they attempted to portray the energy and speed of modern life. In literature, Futurism demanded the abolition of traditional sentence structures and verse forms.<ref>Douglas K. S. Hyland, Ph.D., Director, San Antonio Museum of Art.<br> Hyland, Douglas K. S. "Futurism." ''World Book Advanced.'' World Book, 2011. Web. 4 October 2011.</ref> | |||

| The Leading painters from 1930-40 to 2000 included: | |||

| ], Giorgio de Chirico, ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ],<ref>"Mino Argento" Presentazione di Marcello Venturoli, Roma, 24 Maggio-15 Giugno 1968 Galleria Astrolabio Arte-Roma</ref> ]. | |||

| Futurism was first announced on 20 February 1909, when the Paris newspaper '']'' published a manifesto by the Italian poet and editor ]. (See the ].) Marinetti coined the word Futurism to reflect his goal of discarding the art of the past and celebrating change, originality, and innovation in culture and society. Marinetti's manifesto glorified the new technology of the ] and the beauty of its speed, power, and movement. Exalting violence and conflict, he called for the sweeping repudiation of traditional values and the destruction of cultural institutions such as museums and libraries. The manifesto's rhetoric was passionately bombastic; its aggressive tone was purposely intended to inspire public anger and arouse controversy. | |||

| Important movement was ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ]'' by Umberto Boccioni (1913)]] | |||

| ==Post-Modern Italian art== | |||

| ] is a highly controversial label which generally refers to a period of time after the project(s) of modernism have ended and in which all time periods and styles are not necessarily separated anymore. Just as paints of different colours can be mixed on a palette, so all the styles of antiquity, gothic, renaissance, baroque, expressionist, cubist, ], ], etc. can all be merged and produce hybrids which access and are informed by all the knowledge of art history. Nothing is positively forbidden. Even ] and ] are part of the vocabulary employed to question the ]s of art (and world) philosophy. | |||

| Marinetti's manifesto inspired a group of young painters in Milan to apply Futurist ideas to the visual arts. ], ], ], ], and ] published several manifestos on painting in 1910. Like Marinetti, they glorified originality and expressed their disdain for inherited artistic traditions. | |||

| Good examples of Italian Post-Modern painting are ], ], ], ], ]. | |||

| Figuratives: ], ]. | |||

| Boccioni also became interested in ], publishing a manifesto on the subject in the spring of 1912. He is considered to have most fully realized his theories in two sculptures, ''Development of a Bottle in Space'' (1912), in which he represented both the inner and outer contours of a bottle, and '']'' (1913), in which a human figure is not portrayed as one solid form but is instead composed of the multiple planes in space through which the figure moves. | |||

| ==Contemporary Art== | |||

| Realistic principles extended to architecture as well. ] formulated a Futurist manifesto on architecture in 1914. His visionary drawings of highly mechanized cities and boldly modern skyscrapers prefigure some of the most imaginative 20th-century architectural planning. | |||

| The ] stands as one of the most important international art events in the world. | |||

| Main artists: ], Fabrizio Plessi, ] Francesco Vezzoli, Vanessa Beecroft. | |||

| Boccioni, who had been the most talented artist in the group,<ref>Wilder, Jesse Bryant. John Wiley & Sons, 2007. p. 310. Web. 6 October 2011.</ref> and Sant'Elia both died during military service in 1916. Boccioni's death, combined with expansion of the group's personnel and the sobering realities of the devastation caused by ], effectively brought an end to the Futurist movement as an important historical force in the visual arts. | |||

| ==Different art schools== | |||

| ===Bolognese school=== | |||

| The ''']''' or the ''School of Bologna'' of ] flourished in the Italian city of ], the capital of Emilia Romagna, between the 16th and 17th centuries in ], and rivalled Florence and Rome as the center of painting, with its prominent Renaissance and Baroque art. Its most important representatives include the Carracci family, including ] and his two cousins, the brothers ] and ]. Later it included other prominent ] painters: ] and ], active mostly in ] as would be ] and ]. The ] in Bologna run by ]. | |||

| === |

=== Metaphysical art === | ||

| The ''']''' was a group of ] which flourished in the ] during the ], particularly in the 15th century. At the time, Ferrara was ruled by the ], well known for its patronage of the arts. Patronage was extended with the ascent of ] in 1470, and the family continued in power till ], Ercole's great-grandson, died without an heir in 1597. The duchy was then occupied in succession by Papal and Austrian forces. The school evolved styles of painting that were appeared to blend influences from ], ], ], ], and Florence. Notable artists who attended the school were ] and ], to name but a few. | |||

| {{Main|Metaphysical art}} | |||

| ===Florentine school=== | |||

| The Florentine School refers to artists in, from or influenced by the ] style developed in the 14th century, largely through the efforts of ], and in the 15th century the leading school of the world{{Citation needed|date=April 2010}}. Some of the best known artists of the Florentine School are ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and Masaccio. Even though religious themes were commonly used in art schools before the 14th and 15th centuries, towards the late 14th century, with the plague, more naturalistic styles were put into practice by the Florentine school. | |||

| ] is an Italian art movement, born in 1917 with the work of Carlo Carrà and ] in Ferrara. The word metaphysical, adopted by De Chirico himself, is core to the poetics of the movement. | |||

| ===Lucchese/Pisan school=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The ''']''', also known as the '''School of Lucca''' and as the '''Pisan-Lucchese School''', was a school of painting and sculpture that flourished in the 11th and 12th centuries in western and southern ] with an important center in ]. The art is mostly anonymous. Although not as elegant or delicate as the Florentine School, Lucchese works are remarkable for their monumentality. | |||

| ]'' by ]. ]]] | |||

| ===Sienese school=== | |||

| They depicted a dreamlike imagery, with figures and objects seemingly frozen in time. Metaphysical Painting artists accept the representation of the visible world in a traditional perspective space, but the unusual arrangement of human beings as dummy-like models, objects in strange, illogical contexts, the unreal lights and colors, the unnatural static of still figures. | |||

| ] | |||

| The ''']''' of the ] and ] flourished in the Tuscany city of ], ] between the 13th and 15th centuries and for a time rivaled the artistic centre of ], though it was more conservative, being inclined towards the decorative beauty and elegant grace of late ]. Its most important representatives include ], whose work shows Byzantine influence; his pupil ]; ] and ]; ] and ]; ] and ]. Unlike the naturalistic ], there is a mystical streak in Sienese art{{Who|date=October 2007}}, characterized by a common focus on miraculous events, with less attention to proportions, distortions of time and place, and often dreamlike coloration. In the 16th century the Mannerists ] and ] worked there. While Baldassare Peruzzi was born and trained in Siena, his major works and style reflect his long career in Rome. The economic and political decline of Siena by the 16th century, and its eventual subjugation by Florence, largely checked the development of Sienese painting, although it also meant that a good proportion of Sienese works in churches and public buildings were not discarded or destroyed by new paintings or rebuilding. Siena remains a remarkably well-preserved Italian late-Medieval town. Notable artists who attended this school were ], ] and ], to name a few. | |||

| === |

=== Novecento Italiano === | ||

| {{Main|Novecento Italiano}} | |||

| ], who was part of the Venetian art school.]] | |||

| ], ''Sorelle brianzole'', 1932]] | |||

| ''']''' in ] and painting was a school within ] ] born in 13th century in the area of ] which was flourishing during the 16th through 18th centuries, spreading throughout in ]. | |||

| ], group of Italian artists, formed in 1922 in Milan, that advocated a return to the great Italian representational art of the past. | |||

| In the 16th century, Venetian painting was developed through influences from the Paduan School and ], who introduced the ] technique of the ] brothers. It is signified by a warm colour scale and a picturesque use of ]. Early masters where the ] and ] families, followed by ] and ], than ] and ]. | |||

| The founding members of the Novecento (]: 20th-century) movement were the critic ] and seven artists: ], ], ], Gian Emilio Malerba, Piero Marussig, Ubaldo Oppi, and Mario Sironi. Under Sarfatti's leadership, the group sought to renew Italian art by rejecting European avant-garde movements and embracing Italy's artistic traditions. | |||

| Other artists associated with the Novecento included the sculptors ] and ] and the painters ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| ==List of major Italian art museums and galleries== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == |

=== Spatialism === | ||

| * ] | |||

| {{Main|Spatialism}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| Movement founded by the Italian artist ] as the ], its tenets were repeated in manifestos between 1947 and 1954. | |||

| Combining elements of concrete art, dada and tachism, the movement's adherents rejected easel painting and embraced new technological developments, seeking to incorporate time and movement in their works. Fontana's slashed and pierced paintings exemplify his theses. | |||

| === Arte Povera === | |||

| {{Culture of Italy}} | |||

| {{Main|Arte Povera}} | |||

| ] an artistic movement that originated in Italy in the 1960s, combining aspects of conceptual, minimalist, and performance art, and making use of worthless or common materials such as earth or newspaper, in the hope of subverting the commercialization of art. The phrase is Italian, and means literally, "impoverished art." | |||

| === Transavantgarde === | |||

| {{Main|Transavantgarde}} | |||

| The term ] is the invention of the Italian critic ]. He has defined Transavantgarde art as traditional in format (that is, mostly painting or sculpture); apolitical; and, above all else, eclectic. | |||

| ==List of major museums and galleries in Italy== | |||

| {{main|List of museums in Italy}} | |||

| == Advocacy and restrictions == | |||

| According to the 2017 amendments to the Italian ''Codice dei beni culturali e del paesaggio'',<ref name="codice">{{cite web | url = https://www.camera.it/parlam/leggi/deleghe/testi/04042dl.htm | title = Codice dei beni culturali e del paesaggio | language = Italian | website = ] | access-date = 14 September 2020 | archive-date = 20 November 2019 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20191120063329/https://www.camera.it/parlam/leggi/deleghe/testi/04042dl.htm | url-status = dead }}</ref><ref name="17G00140" /> a work of art can be legally defined of public and cultural interest if it was completed at least 70 years before. The previous limit was 50 years. To make easier the exportations and the international commerce of art goods as a ], for the first time it was given to the private owners and their dealers the faculty to self-certify a commercial value less than 13.500 euros, in order to be authorized to transport goods out of the country's borders and into the European Union, with no need of a public administrative permission.<ref>{{cite news | url = https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2017/08/04/lappello-a-mattarella-i-beni-culturali-non-sono-commerciali-presidente-non-firmi-il-dl-concorrenza/3774966/ | title = L'Appello a Mattarella – "I beni culturali non sono commerciali: presidente non firmi il Dl Concorrenza" | language = Italian | date = 4 August 2017 | journal = ]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web| url = http://documenti.camera.it/leg17/resoconti/assemblea/html/sed0822/tmp0000.htm | title = Shorthand account of the Parliamentary session held on June 28, 2017 | website = ] | language = Italian}}</ref> | |||

| The bill has passed and come into force on 29 August 2017.<ref name="17G00140">{{cite journal | url = https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2017/08/14/17G00140/sg) | title = LEGGE 4 agosto 2017, n. 124 | language = Italian | journal = ]}} at article n. 175.</ref> A public authorization shall be provided for archeological remains discovered underground or under the sea level.<ref name="codice" /> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| {{Portal|Italy|Visual arts}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| ==External links== | == External links == | ||

| * Italian Art. ''kdfineart-italia.com.'' Web. 5 October 2011. | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=August 2007}} | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200615165857/http://www.italianartstudio.com/ |date=15 June 2020 }} Italian and Tuscan style Fine Art. ''italianartstudio.com.'' Web. 5 October 2011. | |||

| * | |||

| * | * Italian art notes | ||

| * | |||

| * Italian and Tuscan style Fine Art | |||

| * | |||

| {{Timeline of Italian artists to 1800}} | |||

| {{Italy topics}} | |||

| {{European topic|| art}} | {{European topic|| art}} | ||

| {{Art of Europe}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Art Of Italy}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:12, 23 November 2024

Since ancient times, Greeks, Etruscans and Celts have inhabited the south, centre and north of the Italian peninsula respectively. The very numerous rock drawings in Valcamonica are as old as 8,000 BC, and there are rich remains of Etruscan art from thousands of tombs, as well as rich remains from the Greek colonies at Paestum, Agrigento and elsewhere. Ancient Rome finally emerged as the dominant Italian and European power. The Roman remains in Italy are of extraordinary richness, from the grand Imperial monuments of Rome itself to the survival of exceptionally preserved ordinary buildings in Pompeii and neighbouring sites. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, in the Middle Ages Italy remained an important centre, not only of the Carolingian art, Ottonian art of the Holy Roman Emperors, Norman art, but for the Byzantine art of Ravenna and other sites.

Italy was the main centre of artistic developments throughout the Renaissance (1300–1600), beginning with the Proto-Renaissance of Giotto and reaching a particular peak in the High Renaissance of Antonello da Messina, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael, whose works inspired the later phase of the Renaissance, known as Mannerism. Italy retained its artistic dominance into the 17th century with the Baroque (1600–1750), and into the 18th century with Neoclassicism (1750–1850). In this period, cultural tourism became a major prop to Italian economy. Both Baroque and Neoclassicism originated in Rome and spread to all Western art. Italy maintained a presence in the international art scene from the mid-19th century onwards, with movements such as the Macchiaioli, Futurism, Metaphysical, Novecento Italiano, Spatialism, Arte Povera, and Transavantgarde.

Italian art has influenced several major movements throughout the centuries and has produced several great artists, including painters, architects and sculptors. Today, Italy has an important place in the international art scene, with several major art galleries, museums and exhibitions; major artistic centres in the country include Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan, Turin, Genoa, Naples, Palermo, Syracuse and other cities. Italy is home to 60 World Heritage Sites, the largest number of any country in the world.

Etruscan art

Main article: Etruscan art

Etruscan bronze figures and a terracotta funerary reliefs include examples of a vigorous Central Italian tradition which had waned by the time Rome began building her empire on the peninsula.

The Etruscan paintings that have survived to modern times are mostly wall frescoes from graves, and mainly from Tarquinia. These are the most important example of pre-Roman figurative art in Italy known to scholars.

The frescoes consist of painting on top of fresh plaster, so that when the plaster is dried the painting becomes part of the plaster and an integral part of the wall, which helps it survive so well (indeed, almost all of surviving Etruscan and Roman painting is in fresco). Colours were made from stones and minerals in different colours that ground up and mixed in a medium, and fine brushes were made of animal hair (even the best brushes are produced with ox hair). From the mid 4th century BC chiaroscuro began to be used to portray depth and volume. Sometimes scenes of everyday life are portrayed, but more often traditional mythological scenes. The concept of proportion does not appear in any surviving frescoes and we frequently find portrayals of animals or men with some body-parts out of proportion. One of the best-known Etruscan frescoes is that of Tomb of the Lioness at Tarquinia.

Roman art

Main article: Roman art

The Etruscans were responsible for constructing Rome's earliest monumental buildings. Roman temples and houses were closely based on Etruscan models. Elements of Etruscan influence in Roman temples included the podium and the emphasis on the front at the expense of the remaining three sides. Large Etruscan houses were grouped around a central hall in much the same way as Roman town Large houses were later built around an atrium. The influence of Etruscan architecture gradually declined during the republic in the face of influences (particularly Greek) from elsewhere. The Etruscan architecture was itself influenced by the Greeks so that when the Romans adopted Greek styles, it was not a totally alien culture. During the republic, there was probably a steady absorption of architectural influences, mainly from the Hellenistic world, but after the fall of Syracuse in 211 BC, Greek works of art flooded into Rome. During the 2nd century BC, the flow of these works, and more important, Greek craftsmen, continued, thus decisively influencing the development of Roman architecture. By the end of the republic, when Vitruvius wrote his treatise on architecture, Greek architectural theory and example were dominant. With the expansion of the empire, Roman architecture spread over a wide area, used for both public buildings and some larger private ones. In many areas, elements of style were influenced by local tastes, particularly decoration, but the architecture remained recognizably Roman. Styles of vernacular architecture were influenced to varying degrees by Roman architecture, and in many regions, Roman and native elements are found combined in the same building.

By the 1st century AD, Rome had become the biggest and most advanced city in the world. The ancient Romans came up with new technologies to improve the city's sanitation systems, roads, and buildings. They developed a system of aqueducts that piped freshwater into the city, and they built sewers that removed the city's waste. The wealthiest Romans lived in large houses with gardens. Most of the population, however, lived in apartment buildings made of stone, concrete, or limestone. The Romans developed new techniques and used materials such as volcanic soil from Pozzuoli, a village near Naples, to make their cement harder and stronger. This concrete allowed them to build large apartment buildings called insulae.

Wall paintings decorated the houses of the wealthy. Paintings often showed garden landscapes, events from Greek and Roman mythology, historical scenes, or scenes of everyday life. Romans decorated floors with mosaics — pictures or designs created with small colored tiles. The richly colored paintings and mosaics helped to make rooms in Roman houses seem larger and brighter and showed off the wealth of the owner.

In the Christian era of the late Empire, from 350 to 500 AD, wall painting, mosaic ceiling and floor work, and funerary sculpture thrived, while full-sized sculpture in the round and panel painting died out, most likely for religious reasons. When Constantine moved the capital of the empire to Byzantium (renamed Constantinople), Roman art incorporated Eastern influences to produce the Byzantine style of the late empire. When Rome was sacked in the 5th century, artisans moved to and found work in the Eastern capital. The Church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople employed nearly 10,000 workmen and artisans, in a final burst of Roman art under Emperor Justinian I, who also ordered the creation of the famous mosaics of Ravenna.

Medieval art

Throughout the Middle Ages, Italian art consisted primarily of architectural decorations (frescoes and mosaics). Byzantine art in Italy was a highly formal and refined decoration with standardized calligraphy and admirable use of color and gold. Until the 13th century, art in Italy was almost entirely regional, affected by external European and Eastern currents. After c. 1250 the art of the various regions developed characteristics in common, so that a certain unity, as well as great originality, is observable.

Italo-Byzantine art

Main article: Italo-ByzantineWith the fall of its western capital, the Roman Empire continued for another 1000 years under the leadership of Constantinople. Byzantine artisans were used in important projects throughout Italy, and what are called Italo-Byzantine styles of painting can be found up to the 14th century.

Italo-Byzantine style initially covers religious paintings copying or imitating the standard Byzantine icon types, but painted by artists without a training in Byzantine techniques. These are versions of Byzantine icons, most of the Madonna and Child, but also of other subjects; essentially they introduced the relatively small portable painting with a frame to Western Europe. Very often they are on a gold ground. It was the dominant style in Italian painting until the end of the 13th century, when Cimabue and Giotto began to take Italian, or at least Florentine, painting into new territory. But the style continued until the 15th century and beyond in some areas and contexts.

Duecento

Duecento is the Italian term for the culture of the 13th century. The period saw Gothic architecture, which had begun in northern Europe spreading southward to Italy, at least in the north. The Dominican and Franciscan orders of friars, founded by Saint Dominic and Saint Francis of Assisi respectively became popular and well-funded in the period, and embarked on large building programmes, mostly using a cheaper and less highly decorated version of Gothic. Large schemes of fresco murals were cheap, and could be used to instruct congregations. The Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, in effect two large churches, one above the other on a hilly site, is one of the best examples, begun in 1228 and painted with frescos by Cimabue, Giotto, Simone Martini, Pietro Lorenzetti and possibly Pietro Cavallini, most of the leading painters of the period.

Trecento

Main article: Trecento

Trecento is the Italian term for the culture of the 14th century. The period is considered to be the beginning of the Italian Renaissance or at least the Proto-Renaissance in art history. Painters of the Trecento included Giotto di Bondone, as well as painters of the Sienese School, which became the most important in Italy during the century, including Duccio di Buoninsegna, Simone Martini, Lippo Memmi, Ambrogio Lorenzetti and his brother Pietro. Important sculptors included two pupils of Giovanni Pisano: Arnolfo di Cambio and Tino di Camaino, and Bonino da Campione.

Renaissance art

Main articles: Italian Renaissance painting and Italian Renaissance sculptureDuring the Middle Ages, painters and sculptors tried to give their works a spiritual quality. They wanted viewers to concentrate on the deep religious meaning of their paintings and sculptures. But Renaissance painters and sculptors, like Renaissance writers, wanted to portray people and nature realistically. Medieval architects designed huge cathedrals to emphasize the grandeur of God and to humble the human spirit. Renaissance architects designed buildings whose proportions were based on those of the human body and whose ornamentation imitated ancient designs.

Early Renaissance

During the early 14th century, the Florentine painter Giotto became the first artist to portray nature realistically since the fall of the Roman Empire. He produced magnificent frescoes (paintings on damp plaster) for churches in Assisi, Florence, Padua, and Rome. Giotto attempted to create lifelike figures showing real emotions. He portrayed many of his figures in realistic settings.

A remarkable group of Florentine architects, painters, and sculptors worked during the early 15th century. They included the painter Masaccio, the sculptor Donatello, and the architect Filippo Brunelleschi.

Masaccio's finest work was a series of frescoes he painted about 1427 in the Brancacci Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. The frescoes realistically show Biblical scenes of emotional intensity. In these paintings, Masaccio utilized Brunelleschi's system for achieving linear perspective.

In his sculptures, Donatello tried to portray the dignity of the human body in realistic and often dramatic detail. His masterpieces include three statues of the Biblical hero David. In a version finished in the 1430s, Donatello portrayed David as a graceful, nude youth, moments after he slew the giant Goliath. The work, which is about 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall, was the first large free-standing nude created in Western art since classical antiquity.

Brunelleschi was the first Renaissance architect to revive the ancient Roman style of architecture. He used arches, columns, and other elements of classical architecture in his designs. One of his best-known buildings is the beautifully and harmoniously proportioned Pazzi Chapel in Florence. The chapel, begun in 1442 and completed about 1465, was one of the first buildings designed in the new Renaissance style. Brunelleschi also was the first Renaissance artist to master linear perspective, a mathematical system with which painters could show space and depth on a flat surface.

High Renaissance

Main article: High Renaissance

Arts of the late 15th century and early 16th century were dominated by three men. They were Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

Leonardo da Vinci painted two of the most famous works of Renaissance art, the wallpainting The Last Supper and the portrait Mona Lisa. Leonardo had one of the most searching minds in all history. He wanted to know how everything that he saw in nature worked. In over 4,000 pages of notebooks, he drew detailed diagrams and wrote his observations. Leonardo made careful drawings of human skeletons and muscles, trying to learn how the body worked. Due to his inquiring mind, Leonardo has become a symbol of the Renaissance spirit of learning and intellectual curiosity.

Michelangelo excelled as a painter, architect, and poet. In addition, he has been called the greatest sculptor in history. Michelangelo was a master of portraying the human figure. For example, his famous statue of the Israelite leader Moses (1516) gives an overwhelming impression of physical and spiritual power. These qualities also appear in the frescoes of Biblical and classical subjects that Michelangelo painted on the ceiling of the Vatican's Sistine Chapel. The frescoes, painted from 1508 to 1512, rank among the greatest works of Renaissance art.