| Revision as of 23:41, 12 March 2006 editMusicMaker5376 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers12,289 editsm →Mesopotamian flood stories← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:23, 18 December 2024 edit undo193.136.242.233 (talk)No edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2024}} | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| {{hatnote group| | |||

| :''This concerns the boat described in the Hebrew scriptures. For other senses, see ].'' | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|Ark of the Covenant}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{pp | |||

| | 1 = dispute | |||

| | small = yes | |||

| | action = edit | |||

| | expiry = 17:07, 27 August 2018 | |||

| | date = 20 August 2018 | |||

| | user = Vsmith | |||

| | section = talk page section name | |||

| | category = no | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Short description|Vessel in the Genesis flood narrative}}<!--Before modifying, check the discussion in the talk page titled, "Fictional? --> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| '''Noah's Ark''' ({{langx|he|תיבת נח}}; ]: ''Tevat Noaḥ'')<ref group="Notes" name="Ark">The word "ark" in modern English comes from Old English ''aerca'', meaning a chest or box. (See Cresswell 2010, p.22) The Hebrew word for the vessel, ''teva'', occurs twice in the ], in the flood narrative (] 6–9) and in the ], where it refers to the basket in which ] places the infant ]. (The word for the ], ''aron'', is quite different.) The Ark is built to save Noah, his family, and representatives of all animals from a divinely-sent flood intended to wipe out all life, and in both cases, the ''teva'' has a connection with ] from waters. (See Levenson 2014, p.21)</ref> is the boat in the ] through which ] spares ], his family, and examples of all the world's animals from a global deluge.{{sfn|Bailey|1990|p=63}} The story in Genesis is based on earlier ]s originating in ], and is repeated, with variations, in the ], where the Ark appears as ''Safinat ]'' ({{langx|ar|سَفِينَةُ نُوحٍ}} "Noah's ship") and ''al-fulk'' (Arabic: الفُلْك). The myth of the global flood that destroys all life begins to appear in the ] period (20th–16th centuries BCE).<ref name="t984">{{cite book | last=Chen | first=Y. S. | title=The Primeval Flood Catastrophe | publisher=Oxford University Press, USA | publication-place=Oxford, United Kingdom | year=2013 | isbn=978-0-19-967620-0 | oclc=839396707 | page=2}}</ref> The version closest to the biblical story of Noah, as well as its most likely source, is that of ] in the ].{{sfn|Nigosian|2004|p=40}} | |||

| ] (1780–1849), showing the animals boarding Noah's Ark two by two.]] | |||

| Early Christian and Jewish writers, such as ], believed that Noah's Ark existed. Unsuccessful ] have been made from at least the time of ] (c. 275–339 CE). Believers in the Ark continue to search for it in modern times, but no scientific evidence that the Ark existed has ever been found,<ref name="Cline 2009" /> nor is there scientific evidence for a global flood.<ref>{{Cite news |author=Lorence G. Collins |date=2009 |title=Yes, Noah's Flood May Have Happened, But Not Over the Whole Earth |language=en |work=NCSE |url=https://ncse.com/library-resource/yes-noahs-flood-may-have-happened-not-over-whole-earth |url-status=live |access-date=22 August 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180626054743/https://ncse.com/library-resource/yes-noahs-flood-may-have-happened-not-over-whole-earth |archive-date=26 June 2018}}</ref> The boat and the natural disaster as described in the Bible would have been contingent upon physical impossibilities and extraordinary anachronisms.<ref name="Moore1983">{{cite journal |last=Moore |first=Robert A. |year=1983 |title=The Impossible Voyage of Noah's Ark |url=https://ncse.com/cej/4/1/impossible-voyage-noahs-ark |url-status=live |journal=Creation Evolution Journal |volume=4 |pages=1–43 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160717074346/https://ncse.com/cej/4/1/impossible-voyage-noahs-ark |archive-date=17 July 2016 |access-date=10 July 2016 |number=1}}</ref> Some researchers believe that a real (though localized) flood event in the ] could potentially have inspired the oral and later written narratives; a Persian Gulf flood, or a ] 7,500 years ago has been proposed as such a historical candidate.<ref name="RyanOthers1997a">{{Cite journal |last1=Ryan |first1=W. B. F. |last2=Pitman|first2=W. C.|last3=Major|first3=C. O. |last4=Shimkus |first4=K. |last5=Moskalenko |first5=V. |last6=Jones|first6=G. A. |last7=Dimitrov |first7=P. |last8=Gorür |first8=N. |last9=Sakinç |first9=M. |date=1997 |title=An abrupt drowning of the Black Sea shelf |url=http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/~billr/BlackSea/Ryan_et_al_MG_1997.pdf |journal=Marine Geology |volume=138|issue=1–2|pages=119–126|doi=10.1016/s0025-3227(97)00007-8|access-date=23 December 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304104301/http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/~billr/BlackSea/Ryan_et_al_MG_1997.pdf|archive-date=4 March 2016|url-status=dead|citeseerx=10.1.1.598.2866 |bibcode=1997MGeol.138..119R |s2cid=129316719 | issn=0025-3227 }}</ref><ref name="RyanOthers2003a">{{cite journal |last1=Ryan |first1=W. B. |last2=Major |first2=C. O. |last3=Lericolais |first3=G. |last4=Goldstein |first4=S. L. |year=2003 |title=Catastrophic flooding of the Black Sea |journal=Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=525–554 |doi= 10.1146/annurev.earth.31.100901.141249|bibcode=2003AREPS..31..525R }}</ref> | |||

| According to the Bible, '''Noah's Ark''' was a massive ] built at ]'s command to save ], his family, and a core stock of the world's animals from the ]. The story is contained in the ]'s book of ], chapters 6 to 9. | |||

| ==Description== | |||

| According to one school of modern textual criticism - the ], the Ark story told in Genesis is based on two originally quasi-independent sources, and did not reach its present form until the 5th century BC. According to this hypothesis, the process of composition over many centuries helps to explain apparent confusion and repetition in the text. Nevertheless, many ] and traditional ]s reject this analysis, holding that the Ark story is true, that it has a single author (]), and that any perceived inadequacies can be rationally explained. | |||

| The structure of the Ark (and the chronology of the flood) is homologous with the Jewish Temple and with Temple worship.{{sfn|Blenkinsopp|2011|p=139}} Accordingly, Noah's instructions are given to him by God (Genesis 6:14–16): the ark is to be 300 ]s long, 50 cubits wide, and 30 cubits high (approximately {{convert|134|*|22|*|13|m|ft|abbr=on|disp=or}}).{{sfn|Hamilton|1990|pp=280–281}} These dimensions are based on a numerological preoccupation with the number 60, the same number characterizing the vessel of the Babylonian flood hero.{{sfn|Bailey|1990|p=63}} | |||

| Its three internal divisions reflect the three-part universe imagined by the ancient Israelites: heaven, the earth, and the underworld.{{sfn|Kessler|Deurloo|2004|p=81}} Each deck is the same height as the Temple in Jerusalem, itself a microcosmic model of the universe, and each is three times the area of the court of the tabernacle, leading to the suggestion that the author saw both Ark and ] as serving for the preservation of human life.{{sfn|Wenham|2003|p=44}}{{sfn|Batto|1992|p=95}} It has a door in the side, and a ''tsohar'', which may be either a roof or a ].{{sfn|Hamilton|1990|pp=280–281}} It is to be made of ] "''goper''", a word which appears nowhere else in the Bible, but thought to be a loan word from the ] ''gupru''<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Longman |first=Tremper |title=The lost world of the flood: mythology, theology, and the deluge debate |last2=Walton |first2=John H. |date=2018 |publisher=IVP Academic, an imprint of InterVarsity Press |isbn=978-0-8308-8782-8 |location=Downers Grove, IL}}</ref> – and divided into ''qinnim'', a word which always refers to birds' nests elsewhere in the Bible, leading some scholars to emend this to ''qanim'', reeds.{{sfn|Hamilton|1990|pp=281}} The finished vessel is to be smeared with ''koper'', meaning ] or ]; in Hebrew the two words are closely related, ''kaparta'' ("smeared") ... ''bakopper''.{{sfn|Hamilton|1990|pp=281}} Bitumen is more likely option as ''"koper"'' is thought to be a loanword from the Akkadian "''kupru''", meaning bitumen.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| The Ark story told in Genesis has extensive and striking parallels in the ] of ], which tells how an ancient king was warned by his personal god to build a vessel in which to escape a flood sent by the higher council of gods. Less exact parallels are found in other cultures from around the world. The Ark story has been subject to extensive elaborations in the various ]s, mingling theoretical solutions to practical problems (e.g. how Noah might have disposed of animal waste) with allegorical interpretations (e.g. the Ark as a precursor of the Church, offering salvation to mankind). | |||

| ==Origins== | |||

| By the beginning of the 18th century, the growth of ] as a science meant that few ] felt able to justify a literal interpretation of the Ark story. Nevertheless, ] continue to explore the region of the ], in northeastern ], where the Bible says Noah's Ark came to rest. | |||

| ===Mesopotamian precursors=== | |||

| {{Main|Flood myth}} | |||

| For well over a century, scholars have said that the Bible's story of Noah's Ark is based on older Mesopotamian models.{{sfn|Kvanvig|2011|p=210}} Because all these flood stories deal with events that allegedly happened at the dawn of history, they give the impression that the myths themselves must come from very primitive origins, but the myth of the global flood that destroys all life only begins to appear in the ] (20th–16th centuries BCE).{{sfn|Chen|2013|pp=3–4}} The reasons for this emergence of the typical Mesopotamian flood myth may have been bound up with the specific circumstances of the end of the ] around 2004 BCE and the restoration of order by the ].{{sfn|Chen|2013|p=253}} | |||

| Nine versions of the Mesopotamian flood story are known, each more or less adapted from an earlier version. In the oldest version, inscribed in the Sumerian city of ] around 1600 BCE, the hero is King ]. This story, the ], probably derives from an earlier version. The Ziusudra version tells how he builds a boat and rescues life when the gods decide to destroy it. This basic plot is common in several subsequent flood stories and heroes, including Noah. Ziusudra's Sumerian name means "he of long life." In Babylonian versions, his name is ], but the meaning is the same. In the Atrahasis version, the flood is a river flood.<ref name="Cline">{{cite book |last=Cline |first=Eric H. |year=2007 |title=From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible |publisher=National Geographic |isbn=978-1-4262-0084-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bJW-zhffwk4C&q=From+Eden+to+Exile%3A+Unraveling+Mysteries+of+the+Bible}}</ref>{{rp|20–27}} | |||

| ==Narrative== | |||

| ], ''The Deluge'', ], the ].]] | |||

| The version closest to the biblical story of Noah is that of ] in the '']''.{{sfn|Nigosian|2004|p=40}} A complete text of Utnapishtim's story is contained on a clay tablet dating from the seventh century BCE, but fragments of the story have been found from as far back as the 19th century BCE.{{sfn|Nigosian|2004|p=40}} The last known version of the Mesopotamian flood story was written in ] in the third century BCE by a Babylonian priest named ]. From the fragments that survive, it seems little changed from the versions of 2,000 years before.{{sfn|Finkel|2014|pp=89–101}} | |||

| The story of Noah's Ark according to chapters 6 to 9 of the Book of ] begins with God observing man's evil behaviour and deciding to flood the earth and destroy all life. However, God found one good man, Noah, "a righteous man, blameless among the people of his time", and decided that he would carry forth the lineage of man. God told Noah to make an ark, and to bring with him his wife, and his sons Shem, Ham, and Japheth, and their wives. Additionally, he was to bring pairs of all living creatures, male and female, and in order to provide sustenance, he was told to bring and store food.{{ref|narr_1}} | |||

| The parallels between Noah's Ark and the arks of Babylonian flood heroes Atrahasis and Utnapishtim have often been noted. Atrahasis's Ark was circular, resembling an enormous '']'', with one or two decks.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Nova: Secrets of Noah's Ark|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/secrets-of-noahs-ark/|date=7 October 2015|website=www.pbs.org|language=en-US|access-date=17 May 2020}}</ref> Utnapishtim's ark was a ] with six decks of seven compartments, each divided into nine subcompartments (63 subcompartments per deck, 378 total). Noah's Ark was rectangular with three decks. A progression is believed to exist from a circular to a cubic or square to rectangular. The most striking similarity is the near-identical deck areas of the three arks: 14,400 cubits<sup>2</sup>, 14,400 cubits<sup>2</sup>, and 15,000 cubits<sup>2</sup> for Atrahasis, Utnapishtim, and Noah, only 4% different. ] concluded, "the iconic story of the Flood, Noah, and the Ark as we know it today certainly originated in the landscape of ancient Mesopotamia, modern Iraq."{{sfn|Finkel|2014|loc=chpt.14}} | |||

| When Noah completed the Ark he and his family and the animals entered, and "the same day were all the fountains of the great deep broken up, and the windows of heaven were opened, and the rain was upon the earth forty days and forty nights." The flood covered even the highest mountains to a depth of more than twenty feet, and all creatures on Earth died; only Noah and those with him on the Ark were left alive.{{ref|narr_2}} | |||

| Linguistic parallels between Noah's and Atrahasis' arks have also been noted. The word used for "pitch" (sealing tar or resin) in Genesis is not the normal Hebrew word, but is closely related to the word used in the Babylonian story.{{sfn|McKeown|2008|p=55}} Likewise, the Hebrew word for "ark" (''tēvāh'') is nearly identical to the Babylonian word for an oblong boat (''ṭubbû''), especially given that "v" and "b" are the same letter in Hebrew: ] (ב).{{sfn|Finkel|2014|loc=chpt.14}} | |||

| Finally, after about 220 days, the Ark came to rest on the ], and the waters receded for another forty days until the mountaintops emerged. Then Noah sent out a raven which "went to and fro until the waters were dried up from the earth". Next Noah sent a dove out, but it returned having found nowhere to land. After a further seven days, Noah again sent out the dove, and it returned with an olive leaf in its beak, and he knew that the waters had subsided. Noah waited seven days more and sent out the dove once more, and this time it did not return. Then he and his family and all the animals left the Ark, and Noah made a sacrifice to God, and God resolved that he would never again curse the Earth because of man, and never again would He destroy all life on it.{{ref|narr_3}} | |||

| However, the causes for God or the gods sending the flood differ in the various stories. In the Hebrew myth, the flood inflicts God's judgment on wicked humanity. The Babylonian '']'' gives no reasons, and the flood appears the result of divine caprice.<ref name="May Metzger">May, Herbert G., and Bruce M. Metzger. ''The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha''. 1977.</ref> In the Babylonian ] version, the flood is sent to reduce human overpopulation, and after the flood, other measures were introduced to limit humanity.<ref>{{cite book|editor1=Stephanie Dalley |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0YHfiCz4BRwC&q=flood|title=Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others| date=2000 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160424054145/https://books.google.com/books?id=0YHfiCz4BRwC#v=onepage&q=flood&f=false |archive-date=24 April 2016 |pages= 5–8| publisher=OUP Oxford | isbn=978-0-19-953836-2 }}</ref><ref>Alan Dundes, ed., {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160514162849/https://books.google.com/books?id=E__dnnQwGDwC&pg=PA62#v=onepage&q=Gilgamesh%2C%20flood&f=false |date=14 May 2016 }}, pp. 61–71.</ref><ref>J. David Pleins, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160624184753/https://books.google.com/books?id=PX0fIE5IU8gC&pg=PA102#v=onepage&q=ziusudra%20flood%20story&f=false |date=24 June 2016 }}, pp. 102–103.</ref> | |||

| In order to remember this promise, God put a ] in the clouds, saying, “Whenever I bring clouds over the earth and the rainbow appears in the clouds, I will see it and remember the everlasting ] between God and all living creatures of every kind on the earth."{{ref|narr_4}} | |||

| ===Composition=== | |||

| ''(For the ] between God and Noah, and further incidents in Noah's life, see main article ]).'' | |||

| {{main|Genesis flood narrative#Composition}} | |||

| A consensus among scholars indicates that the ] (the first five books of the Bible, beginning with Genesis) was the product of a long and complicated process that was not completed until after the ].{{sfn|Enns|2012|p=23}} Since the 18th century, the flood narrative has been analysed as a paradigm example of the combination of two different versions of a story into a single text, with one marker for the different versions being a consistent preference for different names "Elohim" and "Yahweh" to denote God.<ref>Richard Elliot Friedman (1997 ed.), ''Who Wrote the Bible'', p. 51.</ref> | |||

| ==Religious views== | |||

| == Textual analysis == | |||

| ===Rabbinic Judaism=== | |||

| ]: British Library Add. MS. 4,707]] | |||

| {{Main|Noah in rabbinic literature}} | |||

| The ]ic ] ], ], and ] relate that, while Noah was building the Ark, he attempted to warn his neighbors of the coming deluge, but was ignored or mocked. God placed lions and other ferocious animals to protect Noah and his family from the wicked who tried to keep them from the Ark. According to one ], it was God, or the ]s, who gathered the animals and their food to the Ark. As no need existed to distinguish between clean and unclean animals before this time, the clean animals made themselves known by kneeling before Noah as they entered the Ark.{{Citation needed|date=June 2018}} A differing opinion is that the Ark itself distinguished clean animals from unclean, admitting seven pairs each of the former and one pair each of the latter.<ref name="Sefaria.org">{{Cite web|title=Sanhedrin 108b:7–16|url=https://www.sefaria.org/Sanhedrin.108b.7|access-date=13 October 2021|website=www.sefaria.org}}</ref>{{Primary source inline|date=October 2021}} | |||

| According to Sanhedrin 108b, Noah was engaged both day and night in feeding and caring for the animals, and did not sleep for the entire year aboard the Ark.<ref>Avigdor Nebenzahl, ''Tiku Bachodesh Shofer: Thoughts for ]'', Feldheim Publishers, 1997, p. 208.</ref> The animals were the best of their kind and behaved with utmost goodness. They did not procreate, so the number of creatures that disembarked was exactly equal to the number that embarked. The raven created problems, refusing to leave the Ark when Noah sent it forth, and accusing the patriarch of wishing to destroy its race, but as the commentators pointed out, God wished to save the raven, for its descendants were destined to feed the prophet ].<ref name="Sefaria.org" />{{Primary source inline|date=October 2021}} | |||

| The 87 verses of the Ark narrative present a story of great power and poetry, but they leave an impression of occasional confusion: Why does the story state twice over that mankind had grown corrupt but that Noah was to be saved (Gen 6:5–8; 6:11–13)? Was Noah commanded to take one pair of each clean animal into the Ark (Gen 6:19–20) or seven pairs (Gen 7:2–3)? Did the flood last forty days (Gen. 7:17) or a hundred and fifty days (Gen 7:24)? What happened to the raven that was sent out from the Ark at the same time as the dove and "went to and fro until the waters had subsided from the face of the earth" some two to three weeks later (Gen 8:7)? Why does the narrative appear to have two logical end-points (Gen 8:20–22 and 9:1–17)? Questions such as these are not unique to the Ark narrative, or to Genesis, and the attempt to find a solution has led to the emergence of what is currently the dominant school of thought on the textual analysis of the first five books of the Bible, the ]. | |||

| According to one tradition, refuse was stored on the lowest of the Ark's three decks, humans and clean beasts on the second, and the unclean animals and birds on the top. A differing interpretation described the refuse as being stored on the topmost deck, from where it was shoveled into the sea through a trapdoor. Precious stones, as bright as the noon sun, provided light, and God ensured the food remained fresh.<ref name="JE Noah"/><ref name="Ark of Noah"/><ref>{{cite book |editor-last=Hirsch |editor-first=E. G. |editor2-last=Muss-Arnolt |editor2-first=W. |editor3-last=Hirschfeld |editor3-first=H. |editor-link3=Hartwig Hirschfeld|editor-link1=Emil G. Hirsch |editor-link2=William Muss-Arnolt |title=Jewish Encyclopedia |year=1906 |publisher=JewishEncyclopedia.com |chapter=The Flood |chapter-url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=218&letter=F }}</ref> In an unorthodox interpretation, the 12th-century Jewish commentator ] interpreted the ark as a vessel that remained underwater for 40 days, after which it floated to the surface.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130524092028/http://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=9597&st=&pgnum=123 |date=24 May 2013 }}. HebrewBooks.org.</ref> | |||

| According to the hypothesis, the five books of the ]—], ], ], ] and ]—were edited together in the 5th century BC from four independent sources. The Ark narrative is believed to be made up of material from two of these, the ] and the ]. The Jahwist{{ref|text_1}} is the earlier of the two, composed in the ] from even earlier texts and traditions soon after the separation of Judah and Israel c. 920 BC. The Jahwist narrative is rather simpler than the Priestly story: God sends his flood (for forty days), Noah and his family and the animals are saved (seven of each clean animal), Noah builds an altar and makes sacrifices, and God resolves never again to kill every living thing. The Jahwist source makes no mention of a covenant between God and Noah. | |||

| ===Christianity=== | |||

| The Priestly text{{ref|text_2}} is believed to have been composed at some point between the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 BC and the fall of the southern kingdom of Judah around 586 BC. The material from the Priestly source contains far more detail than the Jahwist—for example, the instructions for the building of the Ark, and the detailed chronology—and also provides the vital theological core of the story, the covenant between God and Noah at Gen 9:1–17, which introduces the peculiarly Jewish method of ritual slaughter, and which forms the quid pro quo for God's promise not to destroy the world again. It is the Priestly source which gives us the raven (the Jahwist has the dove) and the rainbow, and which introduces the windows of heaven and the fountains of the deep (the Jahwist simply says that it rained). Like the Jahwist source, the author of the Priestly text (and it is believed to have been a single author, a member of the Aaronite priesthood of Jerusalem) would have had access to earlier texts and traditions which are now lost. | |||

| ]'' (1493)]] | |||

| ]'s German Bible]] | |||

| The ] (composed around the end of the first century AD<ref>''The Early Christian World,'' Volume 1, p.148, ]</ref>) compared Noah's salvation through water to Christian salvation through baptism.<ref>{{bibleverse|1Pt|3:20–21}}</ref> ] (died 235) sought to demonstrate that "the Ark was a symbol of the ] who was expected", stating that the vessel had its door on the east side—the direction from which Christ would appear at the ]—and that the bones of ] were brought aboard, together with gold, ], and ] (the symbols of the ]). Hippolytus furthermore stated that the Ark floated to and fro in the four directions on the waters, making the sign of the cross, before eventually landing on Mount Kardu "in the east, in the land of the sons of Raban, and the Orientals call it Mount Godash; the ] call it Ararat".<ref name="Knight, K 2007">{{cite web |author = Hippolytus |title = Fragments from the Scriptural Commentaries of Hippolytus |url = http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0502.htm |publisher = New Advent |access-date = 27 June 2007 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070417130437/http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0502.htm |archive-date = 17 April 2007 |url-status = live |df = dmy-all}}</ref> On a more practical plane, Hippolytus explained that the lowest of the three decks was for wild beasts, the middle for birds and domestic animals, and the top for humans. He says male animals were separated from females by sharp stakes to prevent breeding.<ref name="Knight, K 2007"/> | |||

| The early ] and theologian ] (''circa'' 182–251), in response to a critic who doubted that the Ark could contain all the animals in the world, argued that Moses, the traditional author of the book of Genesis, had been brought up in ] and would therefore have used the larger Egyptian cubit. He also fixed the shape of the Ark as a truncated ], square at its base, and tapering to a square peak one cubit on a side; only in the 12th century did it come to be thought of as a rectangular box with a sloping roof.{{sfn|Cohn|1996|p=38}} | |||

| The Ark story's theme of God's anger at man's wickedness, His decision to embark on a terrible vengeance, and His later regret, are typical of the Jahwist author or authors, who treat God as a humanlike figure who appears in person in the biblical narrative. The Priestly source, by contrast, normally presents God as distant and unapproachable except through the Aaronite priesthood. Thus, for example, the Jahwist source requires seven of each clean animal to allow for Noah's sacrifices, while the Priestly source reduces this to a single pair, as no sacrifices can be made under priestly rules until the first priest (]) is created in the time of ]. | |||

| Early Christian artists depicted Noah standing in a small box on the waves, symbolizing God saving the Christian Church in its turbulent early years. ] (354–430), in his work '']'', demonstrated that the dimensions of the Ark corresponded to the dimensions of the human body, which according to Christian doctrine is the body of Christ and in turn the body of the Church.<ref name="Schaff, P 1890">{{cite book |last=St. Augustin |editor-last=Schaff |editor-first=Philip |title=Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers |trans-title=St. Augustin's City of God and Christian Doctrine |series=1 |volume=2 |orig-year=c. 400 |year=1890 |publisher=The Christian Literature Publishing Company |chapter=Chapter 26:That the Ark Which Noah Was Ordered to Make Figures In Every Respect Christ and the Church |chapter-url=http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf102.iv.XV.26.html }}</ref> ] ({{Circa|347–420|lk=no}}) identified the raven, which was sent forth and did not return, as the "foul bird of wickedness" expelled by ];<ref>{{cite book |last=Jerome |editor=Schaff, P |title=Niocene and Post-Niocene Fathers: The Principal Works of St. Jerome |series=2 |volume=6 |orig-year=c. 347–420 |year=1892 |publisher=The Christian Literature Publishing Company |chapter=Letter LXIX. To Oceanus. |chapter-url=http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.v.LXIX.html }}</ref> more enduringly, the dove and olive branch came to symbolize the ] and the hope of ] and eventually, peace.<ref name="Cohn"/> The olive branch remains a secular and religious ] today. | |||

| ==Biblical literalism and the Ark == | |||

| ]: ''The Return of the Dove to the Ark'' (1851)]] | |||

| ===Gnosticism=== | |||

| Many conservative Christians (especially in the United States) are believers in ], the concept that the Bible, as the word of God, does not set out to mislead, and hence should be interpreted using ] whenever there is no clear reason for any other reading. Many Orthodox Jews have similar views regarding certain narrative sections, seeing them as literal excepting certain traditional interpretations (generally from the ] or ]). They also tend to trust in traditions regarding the composition of the Bible. Those who follow these ]s, therefore, generally accept the traditional Jewish belief that the Ark narrative in Genesis was written by ]. There is less agreement on when Moses lived, and thus on when the Ark story was written—various dates have been proposed ranging from the 16th century BC to the late 13th century BC. | |||

| According to the '']'', a 3rd-century ] text, Noah is chosen to be spared by the evil ] when they try to destroy the other inhabitants of the Earth with the great flood. He is told to create the ark then board it at a location called Mount Sir, but when his wife ] wants to board it as well, Noah attempts to not let her. So she decides to use her divine power to blow upon the ark and set it ablaze, therefore Noah is forced to rebuild it.<ref>{{cite book|author1=]|author2=]|title=The Gnostic Bible|publisher=]|chapter=The Reality of the Rulers (The Hypostasis of the Archons)|url=http://www.gnosis.org/naghamm/Hypostas-Barnstone.html|date=30 June 2009|access-date=6 February 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ===Mandaeism=== | |||

| For the date of the Flood, literalists rely on interpretation of the genealogies contained in Gen 5 and 11. ], using this method in the 17th century, arrived at 2349 BC, and this date still has acceptance among many. A more recent ] scholar, however, summarising the current state of thought in the light of the various Biblical manuscripts (the ] text in Hebrew, various manuscripts of the Greek ]), and differences of opinion over their correct interpretation, demonstrated that this method of analysis can date the flood only within a range between 3402 and 2462 BC.{{ref|lit_1}} Other opinions, based on other sources and methodologies, lead to dates outside even this bracket—the ] ], for example, providing a date equivalent to 2309 BC. | |||

| In Book 18 of the ], a ], Noah and his family are saved from the Great Flood because they were able to build an ark or ''kawila'' (or ''kauila'', a ] term; it is cognate with Syriac ''kēʾwilā'', which is attested in the ] New Testament, such as ]:38 and ]:27).<ref name="Häberl 2022">{{cite book | last=Häberl | first=Charles | url=https://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/doi/book/10.3828/9781800856271 | title=The Book of Kings and the Explanations of This World: A Universal History from the Late Sasanian Empire | location=Liverpool | publisher=Liverpool University Press | date=2022 | isbn=978-1-80085-627-1 | page=215| doi=10.3828/9781800856271 | doi-broken-date=1 November 2024 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Islam=== | |||

| Literalists explain apparent contradiction in the Ark narrative as the result of the stylist conventions adopted by an ancient text: thus the confusion over whether Noah took seven pairs or only one pair of each clean animal into the Ark is explained as resulting from the author (Moses) first introducing the subject in general terms—seven pairs of clean animals—and then later, with much repetition, specifying that these animals entered the Ark in twos. Literalists see nothing puzzling in the reference to a raven—why should Noah not release a raven?—nor do they see any sign of alternative endings. | |||

| {{Main|Noah in Islam}} | |||

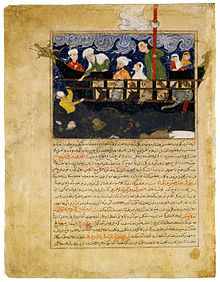

| ] to write a continuation of ] famous history of the world, ]. Like the ], the ] were concerned with legitimizing their right to rule, and Hafiz-i Abru's ''A Collection of Histories'' covers a period that included the time of ] himself.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| In contrast to the Jewish tradition, which uses a term that can be translated as a "box" or "]" to describe the Ark, surah 29:15 of the Quran refers to it as a {{lang|ar-Latn|safina}}, an ordinary ship; surah 7:64 uses ''fulk,''<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Christys |first1=Ann |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1053611250 |title=Die Interaktion von Herrschern und Eliten in imperialen Ordnungen des Mittelalters |date=2018 |others=Wolfram Drews |isbn=978-3-11-057267-4 |publisher=] GmbH |location=Berlin |pages=114–124 |chapter=Educating the Christian Elite in Umayyad Córdoba |oclc=1053611250}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Freidenreich |first=David M. |date=2003 |title=The Use of Islamic Sources in Saadiah Gaon's Tafsīr of the Torah |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/56/article/390127 |journal=Jewish Quarterly Review |volume=93 |issue=3 |pages=353–395 |doi=10.1353/jqr.2003.0009 |s2cid=170764204 |issn=1553-0604}}</ref> and surah 54:13 describes the Ark as "a thing of boards and nails". ], a contemporary of ], wrote that Noah was in doubt as to what shape to make the Ark and that Allah revealed to him that it was to be shaped like a bird's belly and fashioned of ] wood.<ref>{{cite book|last=Baring-Gould|first=Sabine|title=Legends of the Patriarchs and Prophets and Other Old Testament Characters from Various Sources|publisher=James B. Millar and Co., New York|year=1884|chapter=Noah|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=05BuCM6U4DgC&q=eutychius+noah&pg=PA113|page=113}}</ref> | |||

| The medieval scholar ] (died 956) wrote that Allah commanded the Earth to absorb the water, and certain portions which were slow in obeying received ] in punishment and so became ]. The water which was not absorbed formed the seas, so that the waters of the flood still exist. Masudi says the ark began its voyage at ] in central ] and sailed to ], circling the ] before finally traveling to ], which surah 11:44 gives as its final resting place. This mountain is identified by tradition with a hill near the town of ] on the east bank of the ] in the province of ] in northern Iraq, and Masudi says that the spot could be seen in his time.<ref name="JE Noah">{{cite book|editor-last=McCurdy|editor-first=J. F.|editor-link=J. Frederic McCurdy|editor2-last=Bacher|editor2-first=W.|editor3-last=Seligsohn|editor3-first=M.|display-editors=3 |editor4-last=Hirsch|editor4-first=E. G.|title=Jewish Encyclopedia|year=1906|publisher=JewishEncyclopedia.com|chapter=Noah|chapter-url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=318&letter=N&search=noah}}</ref><ref name="Ark of Noah">{{cite book|editor-last=McCurdy|editor-first=J. F.|editor2-last=Jastrow|editor2-first=M. W.|editor3-last=Ginzberg|editor3-first=L.|display-editors=3 |editor4-last=McDonald|editor4-first=D.B.|editor-link2=Marcus Jastrow|title=Jewish Encyclopedia|year=1906|publisher=JewishEncyclopedia.com|chapter=Ark of Noah|chapter-url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=1780&letter=A}}</ref>{{bsn|date=April 2023}} | |||

| Apart from questions of date, authorship, and textual integrity, literalists devote much attention to technical matters such as the identity of "gopher wood" and details of the Ark's construction. The following sets out some of the more commonly discussed topics: | |||

| ]]] | |||

| *'']'': Gen 6:14 states that Noah built the Ark of "gopher" wood, a word not otherwise known in the Bible or in ]. The '']'' believes it was most likely a translation of the Babylonian "gushure in erini" (cedar-beams), or the Assyrian "giparu" (reed).{{ref|lit_2}} The Latin ] (5th century AD) rendered it as "lignis levigatis", or "smoothed (possibly planed) wood". The Greek ] (3rd–1st centuries BC) does not specify any type of wood; it mentions building a square box and tarring it inside and out. Older English translations, including the ] (17th century), simply leave it untranslated. Many modern translations tend to favour ] (although the word for "cypress" in ] is ''erez''), on the basis of a misapplied etymology based on phonetic similarities, while others favor pine or cedar. Recent suggestions have included a lamination process, or a now-lost type of tree, or a mistaken transcription of the word ''kopher'' (]), but there is no consensus.{{ref|lit_3}} | |||

| *''Seaworthiness'': The Ark is described as 300 ]s long, the cubit being a unit of measurement from elbow to outstretched fingertip. Many different cubits were in use in the ancient world, but all were essentially similar, and literalist websites seem to agree that the Ark was approximately 450 feet in length. This is considerably longer than the largest wooden vessels ever built in historical times: according to disputed claims, the early 15th-century Chinese admiral ] may have used junks 400 feet long, but the schooner ''Wyoming'', launched in 1909 and the largest documented wooden-hulled cargo ship ever built, measured only 350 feet and needed iron cross-bracing to counter warping and a steam pump to handle a serious leak problem.{{ref|lit_4}} "The construction and use histories of these ships indicated that they were already pushing or had exceeded the practical limits for the size of wooden ships." {{ref|lit_5}} Literalist scholars who accept these objections—not all do{{ref|lit_6}}—believe that Noah must have built the Ark using advanced post—19th—century techniques such as space—frame construction.{{ref|lit_7}} | |||

| *''Capacity and logistics'': The Ark had a gross volume of about 40,000 m³, a displacement nearly equal to that of the ], and total floor space of around 8,900 square metres (96,000 ft²). The question of whether it could have carried two (or more) specimens of the various species (including those now extinct), plus food and fresh water, is a matter of much debate, even bitter dispute, between literalists and their opponents. While some literalists hold that the Ark could have held all known species, a more common position today is that the Ark contained "kinds" rather than species—for instance, a male and female of the cat "kind" rather than representatives of tigers, lions, cougars, etc. The many associated questions include whether eight humans could have cared for the animals while also sailing the Ark, how the special dietary needs of some of the more exotic animals could have been catered for, questions of lighting, ventilation, and temperature control, hibernation, the survival and germination of seeds, the position of freshwater and saltwater fish, the question of what the animals would have eaten immediately after leaving the Ark, and how they could have travelled to their present habitats. The numerous literalist websites give varying answers, but are in general agreement that none of these problems are insurmountable.{{ref|lit_8}} | |||

| ===Baháʼí Faith=== | |||

| == Other flood accounts == | |||

| The ] regards the Ark and the Flood as symbolic.<ref>From a letter written on behalf of ], 28 October 1949: ''Baháʼí News'', No. 228, February 1950, p. 4. Republished in {{harvnb|Compilation|1983|p=508}}</ref> In Baháʼí belief, only Noah's followers were spiritually alive, preserved in the "ark" of his teachings, as others were spiritually dead.<ref name=BahaiArk>{{cite web|first= Brent|last= Poirier|title= The Kitab-i-Iqan: The key to unsealing the mysteries of the Holy Bible|url= http://bahai-library.com/poirier_iqan_unsealing_bible|access-date= 25 June 2007|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20110707205604/http://bahai-library.com/poirier_iqan_unsealing_bible|archive-date= 7 July 2011|url-status= live|df= dmy-all}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last= Shoghi Effendi|author-link= Shoghi Effendi|year= 1971|title= Messages to the Baháʼí World, 1950–1957|publisher= Baháʼí Publishing Trust|location= Wilmette, Illinois, USA|isbn= 978-0-87743-036-0|url= http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/se/MBW/|page= 104|access-date= 10 August 2008|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20081023220446/http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/se/MBW/|archive-date= 23 October 2008|url-status= live}}</ref> The Baháʼí scripture '']'' endorses the Islamic belief that Noah had numerous companions on the ark, either 40 or 72, as well as his family, and that he taught for 950 (symbolic) years before the flood.<ref>From a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi to an individual believer, 25 November 1950. Published in {{harvnb|Compilation|1983|p=494}}</ref> The Baháʼí Faith was founded in 19th century Persia, and it recognizes divine messengers from both the Abrahamic and the Indian traditions. | |||

| ] tablet of the Gilgamesh epic in ]]] | |||

| === |

===Ancient accounts=== | ||

| Multiple Jewish and Christian writers in the ancient world wrote about the ark. The first-century historian ] reports that the Armenians believed that the remains of the Ark lay "in Armenia, at the mountain of the Cordyaeans", in a location they called the Place of Descent ({{langx|grc|αποβατηριον}}). He goes on to say that many other writers of "barbarian histories", including ], ], and ] mention the flood and the Ark.<ref>{{cite wikisource |last1=Josephus |first1=Flavius |author-] |wslink=The Antiquities of the Jews/Book I#Chapter 3|title=The Antiquities of the Jews, Book I |orig-year=94 AD |chapter=3|quote=Now all the writers of barbarian histories make mention of this flood, and of this ark; among whom is Berosus the Chaldean. For when he is describing the circumstances of the flood, he goes on thus: "It is said there is still some part of this ark in Armenia, at the mountain of the Cordyaeans; and that some people carry off pieces of the bitumen, which they take away, and use chiefly as amulets for the averting of mischiefs." Hieronymus the Egyptian also, who wrote the Phoenician Antiquities, and Mnaseas, and a great many more, make mention of the same. Nay, Nicolaus of Damascus, in his ninety-sixth book, hath a particular relation about them; where he speaks thus: "There is a great mountain in Armenia, over Minyas, called Baris, upon which it is reported that many who fled at the time of the Deluge were saved; and that one who was carried in an ark came on shore upon the top of it; and that the remains of the timber were a great while preserved. This might be the man about whom Moses the legislator of the Jews wrote.}}</ref> | |||

| The majority of modern scholars accept the thesis that the Biblical flood story is linked to a cycle of ] with which it shares many features. The epic of ] can be dated by colophon (scribal identification) to the reign of ]'s great-grandson, ] (1646–1626 BC), and it continued to be copied into the first millennium; the ] story can be dated from its script to the late 17th century BC; and the story of ], known from first millennium copies, is probably derived from Atrahasis.{{ref|derived_from_Atrahasis}} The Mesopotamian flood-myth had a very long currency—the last known retelling dates from the 3rd century BC. A substantial number of the original ], ] and ] texts, written in ], have been recovered by archaeologists, but the task of recovering more tablets continues, as does the translation of extant tablets. | |||

| In the fourth century, ] wrote about Noah's Ark in his '']'', saying "Thus even today the remains of Noah's ark are still shown in Cardyaei."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Williams |first1=Frank |title=The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis |date=2009 |isbn=978-90-04-17017-9 |page=48|publisher=BRILL }}</ref> Other translations render "Cardyaei" as "the country of the Kurds".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Montgomery |first1=John Warwick |title=The Quest For Noahs Ark |date=1974 |isbn=0-87123-477-7 |page=77}}</ref> | |||

| The ], in Akkadian (the language of ancient ]), tells how the god ] warns the hero Atrahasis ("Extremely Wise") of ] to dismantle his house (which is made of reeds) and build a boat to escape a flood with which the god ], angered by the noise of the cities, plans to wipe out mankind. The boat is to have a roof "like ]" (the underworld ocean of freshwater of which Enki is lord), upper and lower decks, and must be sealed with bitumen. Atrahsis boards the boat with his family and animals and seals the door, the storm and flood begin, "bodies clog the river like dragonflies", and even the gods are afraid. After seven days the flood ends and Atrahasis offers sacrifices. Enlil is furious, but Enki defies him, "I made sure life was preserved," and eventually Enki and Enlil agree on other measures for controlling the human population. The story also exists in a later ] version.{{ref|later_Assyrian_version}} | |||

| ] mentioned Noah's Ark in one of his sermons in the fourth century, saying ""Do not the mountains of Armenia testify to it, where the Ark rested? And are not the remains of the Ark preserved there to this very day for our admonition?<ref>{{cite book |last1=Montgomery |first1=John Warwick |title=The Quest For Noahs Ark |date=1974 |isbn=0-87123-477-7 |page=78 }}</ref> | |||

| The story of Ziusudra is told in the ] in the fragmentary Eridu Genesis. It tells how Enki warns Ziusudra (meaning "he saw life", in reference to the gift of immortality given him by the gods), king of Shuruppak, of the gods' decision to destroy mankind with a flood—the passage describing why the gods have decided this is lost. Enki instructs Ziusudra to build a large boat—the text describing the instructions is also lost. After a flood of seven days, Ziusudra makes appropriate sacrifices and prostrations to ] (sky-god) and ] (chief of the gods), and is given eternal life in ], the Sumerian Eden.{{ref|life_in_Dilmun}} | |||

| ==Historicity== | |||

| The ] ] tells of Utnapishtim (a translation of "Ziusudra" into ]) of Shuruppak. ], (the equivalent of Enlil), chief of the gods, wishes to destroy mankind with a flood. Utnapishtim is warned by the god ] (equivalent to Enki) to tear down his reed house and use the materials to build an ark and load it with gold, silver, and the seed of all living creatures and all his craftsmen. After a storm lasting seven days, and a further twelve days on the waters, the ship grounds on Mount Nizir; after seven more days Utnapishtim sends out a dove, which returns, then a swallow, which also returns, and finally a raven, which does not come back. Utnapishtim then makes offerings (by sevens) to the gods, and the gods smell the roasting meat and gather "like flies." Ellil is angry that any human has escaped, but Ea upbraids him, saying, "How couldst thou without thought send a deluge? On the sinner let his sin rest, on the wrongdoer rest his misdeed. Forbear, let it not be done, have mercy, ." Utnapishtim and his wife are then given the gift of immortality and sent to dwell "afar off at the mouth of the rivers".{{ref|mouth_of_the_rivers}} | |||

| ] from 1771 describes the Ark as factual. It also attempts to explain how the Ark could house all living animal types: "... Buteo and ] have proved geometrically, that, taking the common ] as a foot and a half, the ark was abundantly sufficient for all the animals supposed to be lodged in it ... the number of species of animals will be found much less than is generally imagined, not amounting to a hundred species of ]."<ref name="EB1911">{{cite EB1911|wstitle= Ark |volume= 02 |last= Cook |first= Stanley Arthur |author-link= Stanley Arthur Cook | pages = 548–550; see page 549 | quote= Noah's Ark... }}</ref> It also endorses a supernatural explanation for the flood, stating that "many attempts have been made to account for the deluge by means of natural causes: but these attempts have only tended to discredit philosophy, and to render their authors ridiculous".<ref>{{cite EB1911|wstitle= Deluge, The |volume= 07 |last=Cheyne |first= Thomas Kelly |author-link= Thomas Kelly Cheyne | pages = 976–979 }}</ref> | |||

| The 1860 edition attempts to solve the problem of the Ark being unable to house all animal types by suggesting a local flood, which is described in the 1910 edition as part of a "gradual surrender of attempts to square scientific facts with a literal interpretation of the Bible" that resulted in "the ']' and the rise of the modern scientific views as to the origin of species" leading to "scientific comparative mythology" as the frame in which Noah's Ark was interpreted by 1875.<ref name="EB1911"/> | |||

| In the 3rd century BC ], a high priest of the temple of ] in ], wrote a history of Mesopotamia in Greek for ] (323–261 BC). Berossus's ''Babyloniaka'' has not survived, but the 3rd/4th century Christian historian ] retells from it the legend of Xisuthrus, the Greek version of Ziusudra, and essentially the same story. Eusebius concludes that the vessel was still to be seen "in the Corcyræan Mountains of Armenia; and the people scrape off the bitumen, with which it had been outwardly coated, and make use of it by way of an alexipharmic and amulet."{{ref|and_amulet}} | |||

| === |

===Ark's geometry=== | ||

| ].<ref>{{cite web |publisher = ] |url = http://art.thewalters.org/detail/23266 |title = Cameo with Noah's Ark |access-date = 10 December 2013 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20131213133855/http://art.thewalters.org/detail/23266 |archive-date = 13 December 2013 |url-status = dead }}</ref> From the ].]] | |||

| In Europe, the ] saw much speculation on the nature of the Ark that might have seemed familiar to early theologians such as ] and ]. At the same time, however, a new class of scholarship arose, one which, while never questioning the literal truth of the ark story, began to speculate on the practical workings of Noah's vessel from within a purely naturalistic framework. In the 15th century, Alfonso Tostada gave a detailed account of the logistics of the Ark, down to arrangements for the disposal of dung and the circulation of fresh air. The 16th-century ] ] calculated the Ark's internal dimensions, allowing room for Noah's grinding mills and smokeless ovens, a model widely adopted by other commentators.<ref name=Cohn>{{harvnb|Cohn|1996|p=}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=August 2024}} | |||

| ], a curator at the British Museum, came into the possession of a ] tablet. He translated it and discovered an hitherto unknown Babylonian version of the story of the great flood. This version gave specific measurements for an unusually large ] (a type of rounded boat). His discovery lead to the production of a television documentary and a book summarizing the finding. A scale replica of the boat described by the tablet was built and floated in Kerala, India.{{sfn|Finkel|2014|}}{{Page needed|date=August 2024}} | |||

| ] are widespread in world mythology, with examples available from practically every society. Noah's counterpart in ] was ], in ]n texts a terrible flood was supposed to have left only one survivor, a saint named ] who was saved by ] in the form of a fish, and the story of ] in ] mythology contains a very similar account, although in this case it is ice, not water, that threatens life. Flood stories have been found also in the mythologies of many preliterate peoples, from areas distant from Mesopotamia and the Eurasian continent; the Chippewa Indians legend is one example.{{ref|Chippewa_flood_myth}} Biblical literalists point to these stories as evidence that the biblical deluge, and the Ark, represent real history; ] and ] suggest that legends such as the Chippewa have to be treated with great caution due to the well-nigh universal experience of floods, the possibility of contamination from contact with Christianity, and the understandable desire to shape traditional material to fit the newly adopted religion. | |||

| ===Searches for Noah's Ark=== | |||

| ==The Ark in later Abrahamic tradition== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Searches for Noah's Ark}} | |||

| ] have been made from at least the time of ] (c. 275 – 339 CE) to the present day.<ref name="Oxford University Press"/> In the 1st century, Jewish historian ] claimed the remaining pieces of Noah's Ark had been found in Armenia, at the mountain of the Cordyaeans, which is understood to be Mount Ararat in ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Landing-Place of Noah's Ark: Testimonial, Geological and Historical Considerations: Part Four – Associates for Biblical Research |url=https://biblearchaeology.org/research/contemporary-issues/4112-the-landingplace-of-noahs-ark-testimonial-geological-and-historical-considerations-part-four |access-date=27 April 2023 |website=biblearchaeology.org}}</ref> Today, the practice of seeking the remains of the Ark is widely regarded as ].<ref name="Oxford University Press">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ystMAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA582|title=The Oxford Companion to Archaeology|last1=Fagan|first1=Brian M.|last2=Beck|first2=Charlotte|publisher=]|year=1996|isbn=978-0195076189|location=]|author1-link=Brian M. Fagan|access-date=17 January 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160208073258/https://books.google.com/books?id=ystMAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA582|archive-date=8 February 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Cline 2009">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zwNIDHSPsSMC&pg=PA72|title=Biblical Archaeology: A Very Short Introduction|last=Cline|first=Eric H.|pages=71–75|publisher=]|year=2009|isbn=978-0199741076}}</ref><ref name="Feder 2010">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RlRz2symkAsC&pg=PA195|title=Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum|last=Feder|first=Kenneth L.|publisher=]|year=2010|isbn=978-0313379192|location=]|author1-link=Kenneth Feder|access-date=17 January 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160208073258/https://books.google.com/books?id=RlRz2symkAsC&pg=PA195|archive-date=8 February 2016|url-status=live|page=195}}</ref> Various locations for the ark have been suggested but have never been confirmed.<ref name="Mayell-2004">{{cite web|url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/04/0427_040427_noahsark.html|title=Noah's Ark Found? Turkey Expedition Planned for Summer|last=Mayell|first=Hillary|date=27 April 2004|publisher=National Geographic Society|access-date=29 April 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100414031733/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/04/0427_040427_noahsark.html|archive-date=14 April 2010|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="Lovgren-2004">Stefan Lovgren (2004). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120125030621/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/09/0920_040920_noahs_ark.html |date=25 January 2012 }} – National Geographic</ref> Search sites have included the ], a site on ], and ], both in ], but geological investigation of possible remains of the ark has only shown natural sedimentary formations.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.csun.edu/~vcgeo005/Sutton%20Hoo%2014.pdf|last=Collins|first=Lorence G.|title=A supposed cast of Noah's ark in eastern Turkey|year=2011|access-date=26 October 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305191940/http://www.csun.edu/~vcgeo005/Sutton%20Hoo%2014.pdf|archive-date=5 March 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> While biblical literalists often maintain the Ark's existence in archaeological history, its scientific feasibility, along with that of the deluge, has been contested.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Review of John Woodmorappe's "Noah's Ark: A Feasibility Study"|url=http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/woodmorappe-review.html|access-date=6 April 2021|website=www.talkorigins.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=The Impossible Voyage of Noah's Ark {{!}} National Center for Science Education|url=https://ncse.ngo/impossible-voyage-noahs-ark|access-date=6 April 2021|website=ncse.ngo|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| == Var in Zoroastrianism == | |||

| ], 1304–1377, the Moroccan world-traveller who passed by the mountain of al-Judi, near ], resting place of the Ark in Islamic tradition.]] | |||

| In ] 29 and 37,<ref>{{Cite web |title=AVESTA: VENDIDAD (English): Fargard 2: Yima (Jamshed) and the deluge. |url=https://www.avesta.org/vendidad/vd2sbe.htm |access-date=2024-12-05 |website=www.avesta.org}}</ref> mythical Iranian king Yīmā, was ordered by ] to build a subterranean enclosure known as Var, which had a function similar to Noah’s Ark, he was instructed to gather plants, animals, and humans with some exceptions,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Wolff |first=Fritz |title=Avesta: the sacred books of the Parsen |publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| ==Cultural legacy: Noah's Ark replicas == | |||

| === In Rabbinic tradition === | |||

| ] of ].]] | |||

| The story of Noah and the Ark was subject to much embellishment in later Jewish ]. Noah's failure to warn others of the coming flood was widely seen as casting doubt on his righteousness—was he perhaps only righteous by the lights of his own evil generation? According to one tradition, he had in fact passed on God's warning, planting cedars one hundred and twenty years before the Deluge so that the sinful could see and be urged to amend their ways. In order to protect Noah and his family, God placed lions and other ferocious animals to guard them from the wicked who mocked them and offered them violence. According to one ] it was God, or the ], who gathered the animals to the Ark, together with their food. As there had been no need to distinguish between clean and unclean animals before this time, the clean animals made themselves known by kneeling before Noah as they entered the Ark. A differing opinion said that the Ark itself distinguished clean from unclean, admitting seven of the first and two of the second. | |||

| In the modern era, individuals and organizations have sought to reconstruct Noah's ark using the dimensions specified in the Bible, ]<ref name="Antonson">{{cite book |last1=Antonson |first1=Rick |title=Full Moon over Noah's Ark: An Odyssey to Mount Ararat and Beyond |date=12 April 2016 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-5107-0567-8 |language=English}}</ref> ] was completed in 2012 to this end, while the ] was finished in 2016.<ref name="Thomas">{{cite book |last1=Thomas |first1=Paul |title=Storytelling the Bible at the Creation Museum, Ark Encounter, and Museum of the Bible |date=16 April 2020 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=978-0-567-68714-2 |page=23 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| Noah was engaged both day and night in feeding and caring for the animals, and did not sleep for the entire year aboard the Ark. The animals were the best of their species, and so behaved with utmost goodness. They abstained from procreation, so that the number of creatures that disembarked was exactly equal to the number that embarked. Yet Noah was lamed by the lion, rendering him unfit for priestly duties, and the sacrifice at the end of the voyage was therefore carried out by his son Shem. The raven created problems, refusing to go out of the Ark when Noah sent it forth and accusing the Patriarch of having improper designs on its mate. Nevertheless, as the commentators pointed out, God wished to save the raven, for its descendants were destined to feed the prophet ]. | |||

| {{Portal|Religion|Christianity|Islam|Judaism|Mythology}} | |||

| {{div col}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] of the ] in ], ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * The ] in ], Iraq | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| Refuse was stored on the lowest of the Ark's three decks, humans and clean beasts on the second, and the unclean animals and birds on the top. A differing opinion placed the refuse in the upmost story, from where it was shovelled into the sea through a trapdoor. Precious stones, bright as midday, provided light, and God ensured that food was kept fresh. The giant ], king of ], was among those saved—as he must have been, as his descendents are mentioned in later books of the Torah—but owing to his size had to remain outside, Noah passing him food through a hole cut into the wall of the Ark.{{ref|Rabbinic_tradition}} | |||

| {{reflist |group="Notes"}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| === In Islamic tradition === | |||

| Noah is one of the six principle ], generally mentioned in connection with the fate of those who refuse to listen to the Word. References are scattered through the ], with the fullest account at ] 11:27–51, entitled "Hud". | |||

| In contrast to the Jewish tradition, which uses a term which can be translated as a "box" or "chest" to describe the Ark, ] 29:14 refers to it as a ''safina'', an ordinary ship, and surah 54:14 as "a thing of boards and nails". Surah 11:46 says it settled on ], identified by tradition with a hill near the town of Jazirat ibn Umar on the east bank of the ] in the province of ] in northern ], and Abd al-Hasan Ali ibn al-Husayn ] (d. 956) says that the spot where it came to rest could be seen in his time. Masudi also says that the Ark began its voyage at ] in central Iraq and sailed to ], where it circled the ], before finally travelling to Judi. Sura 11:43 says: "And he said, 'Ride ye in it; in the Name of God it moves and stays!'" Abdallah ibn 'Umar al-], writing in the 13th century,takes this to mean that Noah said, "In the Name of God!" when he wished the Ark to move, and the same when he wished it to stand still. | |||

| The flood was sent by ] in answer to Noah's prayer that this evil generation should be destroyed; yet as Noah was righteous he continued to preach, and seventy idolators were converted and entered the Ark with him, bringing the total aboard to 78 humans (these seventy plus the eight members of Noah's own family). The seventy had no offspring, and all of post-flood humanity is descended from Noah's three sons. A fourth son (or a grandson, according to some) named Canaan was among the idolators, and was drowned. | |||

| Baidawi gives the dimensions of the Ark as 300 cubits by 50 by 30, and explains that in the first of the three levels wild and domesticated animals were lodged, in the second the human beings, and in the third the birds. On every plank was the name of a prophet. Three missing planks, symbolising three prophets, were brought from Egypt by Og, son of Anak, the only one of the giants permitted to survive the Flood. The body of ] was carried in the middle to divide the men from the women. | |||

| Noah was five or six months aboard the Ark, at the end of which he sent out a raven. But the raven stopped to feast on carrion, and so Noah cursed it and sent out the dove, which has been known ever since as the friend of mankind. Masudi writes that God commanded the earth to absorb the water, and certain portions which were slow in obeying received salt water in punishment and so became dry and arid. The water which was not absorbed formed the seas, so that the waters of the flood still exist. | |||

| Noah left the Ark on the tenth day of ], and he and his family and companions built a town at the foot of Mount Judi named, Thamanin ("eighty"), from their number. Noah then locked the Ark and entrusted the keys to Shem. ] (1179–1229) mentions a mosque built by Noah which could be seen in his day, and ] passed the mountain on his travels in the 14th century. Modern Muslims, although not generally active in searching for the Ark, believe that it still exists on the high slopes of the mountain.{{ref|Islamic_tradition}} | |||

| === In Christian tradition === | |||

| Early Christian writers created elaborate allegorical meanings for Noah and the Ark. ] (354–430), in '']'', demonstrated that the dimensions of the Ark corresponded to the dimensions of the human body, which is the body of Christ, which is the Church. {{ref|Christian_tradition_1}} The equation of Ark and Church is still found in the ] rite of baptism, which asks God, "who of thy great mercy dids't save Noah," to receive into the Church the infant about to be baptised. ] (c. 347–420) called the raven, which was sent forth and did not return, the "foul bird of wickedness" expelled by baptism;{{ref|Christian_tradition_2}} more enduringly, the dove and olive branch came to symbolise the Holy Spirit and the hope of salvation and, eventually, peace. On a more practical plane, ] (c. 182–251), responding to a critic who doubted that the Ark could contain all the animals in the world, countered with a learned argument about cubits, holding that Moses, the traditional author of the book of Genesis, had been brought up in Egypt and would therefore have used the larger Egyptian cubit; he also fixed the shape of the Ark as a truncated pyramid, rectangular rather than square at its base, and tapering to a square peak one cubit on a side.{{ref|Christian_tradition_3}} It was not until the 12th century that it came to be thought of as a rectangular box with a sloping roof.{{ref|Christian_tradition}} | |||

| ==The Ark under scrutiny== | |||

| The Renaissance saw a continuation of speculation that might have seemed familiar to Origen and Augustine: what of the ], which is unique, how could it come in as a pair? (A popular solution was that it contained male and female in itself); and the ], which by their nature lure sailors to their doom, might they have been permitted on board? (The answer was no; they swam outside); and the bird of paradise, which has no feet, did it therefore fly endlessly inside the Ark? Yet at the same time, a new class of scholarship arose, one which, while never questioning the literal truth of the Ark story, began to speculate on the practical workings of Noah's vessel from within a purely naturalistic framework. Thus in the 15th century, Alfonso Tostada gave a detailed account of the logistics of the Ark, down to arrangements for the disposal of dung and the circulation of fresh air, and the noted 16th-century geometrician Johannes Buteo calculated the ship's internal dimensions, allowing room for Noah's grinding mills and smokeless ovens, a model widely adopted by other commentators.{{ref|Christian_tradition_4}} | |||

| By the 17th century the New World was being explored, awareness was growing of the global distribution of species, and it became necessary to reconcile this knowledge with the belief that all life had sprung from a single point of origin on the slopes of Mount Ararat. The obvious answer was that man had spread over the continents following the destruction of the ] and taken animals with him, yet some of the results seemed peculiar: why had the natives of North America taken rattlesnakes, but not horses, wondered ] in 1646? "How America abounded with Beasts of prey and noxious Animals, yet contained not in that necessary Creature, a Horse, is very strange."{{ref|Christian_tradition_5}} | |||

| Browne was a dilettante rather than a scientist and his remark was an observation made in passing, but more or less contemporary biblical scholars such as ] (1547–1606) and ] (c.1601–1680) were beginning to subject the Ark story to rigorous scrutiny as they attempted to harmonise the biblical account with ] knowledge. The resulting hypotheses were an important impetus to the study of the geographical distribution of plants and animals, and indirectly spurred the emergence of ] in the 18th century. Natural historians began to draw connections between climates and the animals and plants adapted to them. One influential theory held that the biblical Ararat was striped with varying climactic zones, and as climate changed, the associated animals moved as well, eventually spreading to repopulate the globe. There was also the problem of an ever-expanding number of known species: for Kircher and earlier natural historians, there was little problem finding room for all known animals in the Ark, but by the time ] (1627–1705) was working, just several decades after Kircher, the number of known animals had expanded beyond biblical proportions. Incorporating the full range of animal diversity into the Ark story was becoming increasingly difficult, and by 1700 few natural historians could justify a literal interpretation of the Noah's Ark narrative.{{ref|Browne}} | |||

| ==The search for Noah's Ark== | |||

| ] (39°42′N, 44°17′E), satellite image — a ], 5,137 meters (16,854 ft) above sea level, prominence 3,611 meters, believed to have erupted within the last 10,000 years. The main peak is at the centre of the image.]] | |||

| From Eusebius' time to the modern day, the physical Noah's Ark has held a fascination for Christians—although not for Jews and Muslims, who seem to have felt far less impelled to seek out the remains. In the 4th century Faustus of Byzantium was apparently the first to use the name "]" to refer to a specific mountain, rather than a region, where the Ark could be seen, and told how an angel had brought a holy relic from the vessel to a pious bishop who had been unable to complete the ascent.{{ref|Faustus_of_Byzantium}} The Byzantine emperor ] is said to have made the trip in the 7th century, but less well-connected pilgrims had to brave uninhabited wastes, rugged terrain, snowfields, glaciers, blizzards, and, in the more hospitable areas, brigands, wars, and ever-suspicious ] officials. Not until the 19th century was the region settled enough, and Westerners welcome enough, for exploration by well-heeled Ark-seekers to begin in earnest. In 1829 Dr. Freidrich Parrott, who had made an ascent of Greater Ararat, wrote in his ''Journey to Ararat'' that "all the Armenians are firmly persuaded that Noah's Ark remains to this very day on the top of Ararat, and that, in order to preservation , no human being is allowed to approach it."{{ref|Freidrich_Parrott}} In 1876 ], historian, statesman, diplomat, explorer, and Professor of Civil Law at Oxford, climbed above the tree line and found a slab of hand-hewn timber, four feet long and five inches thick, which he identified as being from the Ark.{{ref|James_Bryce}} In 1883 the ''British Prophetic Messenger'' and others reported that Turkish commissioners investigating avalanches had seen the Ark.{{ref|Turkish_Commissioners}} Activity fell off in the 20th century. In the Cold War Ararat found itself on the highly sensitive Turkish/Soviet border and in the midst of Kurdish separatist activities, so that explorers were likely to find themselves in extremely hazardous situations. Former astronaut ] led two expeditions to Ararat in the 1980s, was kidnapped once, and like others found no tangible evidence of the Ark. "I've done all I possibly can," he said, "but the Ark continues to elude us."{{ref|James_Irwin}} | |||

| By the beginning of the 21st century two main candidates for exploration had emerged: the so-called ] near the main summit of Ararat (an "anomaly" in that it shows on aerial and satellite images as a dark blemish on the snow and ice of the peak), and the separate site at ] near Dogubayazit, 18 miles south of the Greater Ararat summit. The Durupinar site was heavily promoted by adventurer and former nurse-anaesthetist ] in the 1980s and 1990s, and consists of a large boat-shaped formation jutting out of the earth and rock. It has the advantage over the Great Ararat site of being approachable—while hardly a major tourist attraction, it receives a steady stream of visitors, and the local authorities have renamed a nearby mountain "Mount Cudi," making it one of at least five Mount Judis in the Middle East. Geologists have identified the Durupinar site as a natural formation,{{ref|Durupinar}} but Wyatt's Ark Discovery Institute continues to champion its claims.{{ref|Arkdiscovery}} | |||

| In 2004 Honolulu-based businessman Daniel McGivern announced he would finance a $900,000 expedition to the peak of Greater Ararat in July that year to investigate the "Ararat anomaly"—he had previously paid for commercial satellite images of the site.{{ref|McGivern_expedition_announced}} After much initial fanfare he was refused permission by the Turkish authorities, as the summit is inside a restricted military zone. The expedition was subsequently labelled a "stunt" by ] News, which pointed out that the expedition leader, a Turkish academic named Ahmet Ali Arslan, had previously been accused of faking photographs of the Ark.{{ref|McGivern_expedition_cancelled}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == |

===Citations=== | ||

| {{Reflist|2}} | |||

| # {{note|narr_1}} | |||

| # {{note|narr_2}} | |||

| # {{note|narr_3}} | |||

| # {{note|narr_4}} | |||

| # {{note|text_1}} | |||

| # {{note|text_2}} | |||

| # {{note|lit_1}} | |||

| # {{note|lit_2}} | |||

| # {{note|lit_3}} | |||

| # {{note|lit_4}} | |||

| # {{note|lit_5}} | |||

| # {{note|lit_6}} | |||

| # {{note|lit_7}} | |||

| # {{note|lit_8}} | |||

| # {{note|derived_from_Atrahasis}} | |||

| # {{note|later_Assyrian_version}} | |||

| # {{note|life_in_Dilmun}} | |||

| # {{note|mouth_of_the_rivers}} | |||

| # {{note|and_amulet}} | |||

| # {{note|Chippewa_flood_myth}} | |||

| # {{note|Rabbinic_tradition}} and ; see also | |||

| # {{note|Islamic_tradition}}see sections on Islamic literature in and | |||

| # {{note|Christian_tradition_1}}Augustine, ''De Civitate Dei'', XV.24 (quoted in Norman Cohn, ''Noah's Flood: The Genesis Story in Western Thought'', pp.28–29 (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1996) ISBN 0-300-06823-9 | |||

| # {{note|Christian_tradition_2}}Jerome, ''Epistola LXIX.6'' (Cohn, op. cit., p.31.) | |||

| # {{note|Christian_tradition_3}}Origen, ''Homilia in Genesim II.2'' (Cohn, op. cit., p.38.) | |||

| # {{note|Christian_tradition_4}}Cohn, loc. cit. | |||

| # {{note|Christian_tradition_5}}Cohn, p.41 | |||

| # {{note|Christian_tradition_6}}Sir Thomas Browne, '']'', 1646 (Cohn, op. cit., p.42.) | |||

| # {{note|Browne}}], ''The Secular Ark: Studies in the History of Biogeography'' (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1983) ISBN 0-300-02460-6 | |||

| # {{note|Faustus_of_Byzantium}} | |||

| # {{note|Freidrich_Parrott}} | |||

| # {{note|James_Bryce}} | |||

| # {{note|Turkish_Commissioners}} | |||

| # {{note|James Irwin}} | |||

| # {{note|Durupinar}} | |||

| # {{note|Arkdiscovery}} | |||

| # {{note|McGivern_expedition_announced}} | |||

| # {{note|McGivern_expedition_cancelled}} | |||

| == |

===Bibliography=== | ||

| {{Refbegin}} | |||

| *{{cite book|last = Bailey|first = Lloyd R.|chapter = Ark|title = Mercer Dictionary of the Bible|publisher = Mercer University Press|year = 1990|isbn = 9780865543737|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=goq0VWw9rGIC&q=Mercer+Dictionary+of+the+Bible+Cosmology&pg=PA176|pages=63–64}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Batto |first=Bernard Frank |title=Slaying the Dragon: Mythmaking in the Biblical Tradition |publisher=Westminster John Knox Press |year=1992 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eWrDOxHQ7-oC&q=ark&pg=PA68|isbn=9780664253530 }} | |||

| *{{citation |last=Blenkinsopp |first=Joseph |title=Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1–11 |year= 2011|publisher= A&C Black |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B12qwOSMD20C |isbn=9780567372871}} | |||

| *{{cite book|first=Norman|last=Cohn|author-link=Norman Cohn|title=Noah's Flood: The Genesis Story in Western Thought|location=New Haven & London|publisher=]|year=1996|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MZ7g-BIfXu0C&q=Noah%27s+Flood%3A+The+Genesis+Story+in+Western+Thought|isbn=978-0-300-06823-8}} | |||

| *{{cite book|author=Compilation|editor-last=Hornby|editor-first=Helen|year= 1983|title= Lights of Guidance: A Baháʼí Reference File |publisher= Baháʼí Publishing Trust, New Delhi, India|isbn= 978-81-85091-46-4|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MZ7g-BIfXu0C&q=Noah%27s+Flood%3A+The+Genesis+Story+in+Western+Thought}} | |||

| *{{citation |last=Enns |first=Peter |title=The Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn't Say about Human Origins |year=2012 |publisher=Baker Books |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BNxeoqoTg-YC |isbn=9781587433153}} | |||

| *{{citation |last=Finkel |first=Irving L. |author-link= Irving Finkel|title=The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood |year=2014 |publisher=Hodder & Stoughton |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lScWAwAAQBAJ&q=tablet&pg=PT274|isbn=9781444757071 }} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Hamilton|first=Victor P.|title=The book of Genesis: Chapters 1–17|publisher=Eerdmans|year=1990|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WW31E9Zt5-wC&q=Genesis&pg=PR3|isbn=9780802825216}} | |||

| *{{cite book|last1=Kessler|first1=Martin|last2=Deurloo|first2=Karel Adriaan|title=A commentary on Genesis: The Book of Beginnings|publisher=Paulist Press|year=2004|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mBWeLCTgT0QC&q=A+commentary+on+Genesis:+the+book+of+beginnings+Martin+Kessler,+Karel+Adriaan+Deurloo|isbn=9780809142057}} | |||

| *{{citation |last1=Kvanvig |first1=Helge |title=Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic: An Intertextual Reading |year=2011 |publisher=BRILL |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=e1hnJYbShWMC|isbn=978-9004163805}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=McKeown |first=James |title=Genesis |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-gqTTl1iPr8C&q=westermann+tabernacle+ark&pg=PA65 |series=Two Horizons Old Testament Commentary |year=2008 |publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company |isbn=978-0-8028-2705-0 |page=398 }} | |||

| *{{citation |last=Nigosian |first=S.A. |title=From Ancient Writings to Sacred Texts: The Old Testament and Apocrypha |year=2004 |publisher=JHU Press |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gpAAKpmMHYoC|isbn=9780801879883}} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Wenham|first=Gordon|chapter=Genesis|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2Vo-11umIZQC&q=Eerdmans+Genesis+his+rise+to+be+ruler+of+all+Egypt&pg=PA34|editor=James D. G. Dunn |editor2=John William Rogerson|title=Eerdmans Bible Commentary|publisher=Eerdmans|year=2003|isbn=9780802837110 }} | |||

| {{Refend}} | |||

| ===Further reading=== | |||

| * ], ''The Secular Ark: Studies in the History of Biogeography'' (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1983) ISBN 0-300-02460-6 | |||

| {{Further reading cleanup|date=August 2024}} | |||

| * ], ''Noah's Flood: The Genesis Story in Western Thought'' (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1996) ISBN 0-300-06823-9 | |||

| '''Commentaries on Genesis''' | |||

| {{Refbegin}} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Towner|first=Wayne Sibley|title=Genesis|publisher=Westminster John Knox Press|year=2001|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6ONdsoa7MHUC&q=Genesis+Wayne+Sibley+Towner|isbn=9780664252564 }} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Von Rad|first=Gerhard|title=Genesis: A Commentary|publisher=Westminster John Knox Press|year=1972|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IbuBa8Qy3AwC&q=Genesis:+A+Commentary+Gerhard+Von+Rad|isbn=9780664227456 }} | |||