| Revision as of 10:33, 11 April 2006 edit212.13.241.91 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:00, 27 December 2024 edit undoXRozuRozu (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers1,677 edits rv good faith edit per WP:OR; I checked the source that User:Laterthanyouthink mentioned and yes, it does mention that Pierre Ordinaire was French.Tag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Alcoholic drink}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{wiktionarypar|absinthe}} | |||

| {{EngvarB |date=May 2014}} | |||

| '''Absinthe''' is a highly-] distilled ]-flavored spirit, and is derived from ]s including the flowers and leaves of the medicinal plant '']'', also called wormwood. Sometimes incorrectly called a ], absinthe does not contain added sugar and is a liquor or spirit. <ref>"Traite de la Fabrication de Liqueurs et de la Distillation des Alcools" Duplais (1882 3rd Ed, Pg 249)</ref> | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=September 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox beverage | |||

| | name = Absinthe | |||

| | image = absinthe-glass.jpg | |||

| | image_alt = stemmed reservoir glass containing a green-colored liquid and a flat, slit, absinthe spoon | |||

| | caption = Reservoir glass with naturally coloured verte absinthe and an ] | |||

| | type = Spirit | |||

| | abv = 45-74% | |||

| | proof = 90–148 | |||

| | origin = Switzerland, France | |||

| | introduced = | |||

| | colour = Green | |||

| | flavour = ] | |||

| | ingredients = {{Plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | variants = | |||

| | related = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Absinthe''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|æ|b|s|ɪ|n|θ|,_|-|s|æ̃|θ}}, {{IPA|fr|apsɛ̃t|lang|Fr-Paris--absinthe.ogg}}) is an ]-flavored ] derived from several plants, including the flowers and leaves of '']'' ("grand wormwood"), together with green ], sweet ], and other medicinal and culinary herbs.<ref name="Chisholm">{{Cite EB1911|wstitle=Absinthe|volume=1|page=75}}</ref> Historically described as a highly alcoholic spirit, it is 45–74% ] or 90–148 proof in the US.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Duplais |first=P. |title=Traite de la Fabrication de Liqueurs et de la Distillation des Alcools |year=1882 |edition=3rd |pages=375–378 |lang=fr}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Fritsch |first=J. |title=Nouveau Traité de la Fabrication des Liqueurs |year=1926 |pages=385–401 |lang=fr}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=De Brevans |first=J. |title=La Fabrication des Liqueurs |year=1908 |pages=251–262 |lang=fr}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Lebead |title=Nouveau Manuel Complet du Distillateur Liquoriste |last2=de Fontenelle |last3=Malepeyre |year=1888 |pages=221–224 |lang=fr}}</ref> Absinthe traditionally has a natural ] color but may also be colorless. It is commonly referred to in historical literature as {{lang|fr|la fée verte}} {{gloss|the green fairy}}. While sometimes casually referred to as a ], absinthe is not traditionally bottled with sugar or sweeteners.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Duplais |title=Traite de la Fabrication de Liqueurs et de la Distillation des Alcools |year=1882 |edition=3rd |page=249 |lang=fr}}</ref> Absinthe is traditionally bottled at a high level of alcohol by volume, but it is normally diluted with water before being consumed. | |||

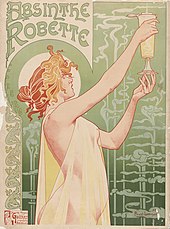

| Absinthe was created in the ] in Switzerland in the late 18th century by the ] physician Pierre Ordinaire.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Wittels |first1=Betina J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BJZEALtWWSMC&dq=pierre+ordinaire+absinthe&pg=PA1 |title=Absinthe: Sip of Seduction |last2=Hermesch |first2=Robert |date=2003 |publisher=Speck Press |isbn=978-0-9725776-1-8 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Wittels |first1=Betina |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HZonDwAAQBAJ&dq=pierre+ordinaire+absinthe&pg=PT88 |title=Absinthe: The Exquisite Elixir |last2=Breaux |first2=T. A. |date=2017-06-06 |publisher=Fulcrum Publishing |isbn=978-1-68275-156-5 |language=en}}</ref> It rose to great popularity as an alcoholic drink in late 19th- and early 20th-century France, particularly among Parisian artists and writers. The consumption of absinthe was opposed by social conservatives and prohibitionists, partly due to its association with ] culture. From Europe and the Americas, notable absinthe drinkers included ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="herald">{{Cite news |date=September 18, 2008 |title=The Appeal of 'The Green Fairy' |url=http://www.heraldtribune.com/article/20080918/ARTICLE/809170246/2406/FEATURES&title=The_Appeal_of__The_Green_Fairy_ |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160120231747/http://www.heraldtribune.com/article/20080918/ARTICLE/809170246/2406/FEATURES%26title%3DThe_Appeal_of__The_Green_Fairy_ |archive-date=2016-01-20 |access-date=2022-02-03 |work=]}}</ref><ref name="SAMA">{{Cite journal |last=Arnold |first=Wilfred Niels |year=1988 |title=Vincent van Gogh and the Thujone Connection' |journal=JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association |volume=260 |issue=20 |pages=3042–3044 |doi=10.1001/jama.1988.03410200098033 |pmid=3054185}}</ref> | |||

| Nicknamed ''la Fée Verte'' ("The Green ]"), absinthe has a similar taste to anise-flavored liqueurs, with a light bitterness and more complex flavor imparted by the use of other herbs, and is traditionally clear, pale green or emerald ] in color. It is drunk by adding three to five parts ice cold water to a dose of absinthe, this causes the drink to louche (turn cloudy). It began as an elixir in Switzerland but is especially known for its popularity in ]—particularly its romantic associations with ] artists and writers—in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The most popular brand of absinthe worldwide at the time was ]. At the height of its popularity, absinthe was portrayed as a dangerously ], ] drug, the chemical ] was blamed for most of its deleterious effects; one particularly popular myth was that it made people believe they were animals. By 1915 it was banned in a number of European countries and the ]. Modern evidence shows it to be as safe as ordinary alcohol. A modern-day absinthe revival began in the 1990s, as countries in the ] began to reauthorize its manufacture and sale. | |||

| <!-- #absinthism --> | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| Absinthe has often been portrayed as a dangerously addictive psychoactive drug and ], which gave birth to the term '']''.<ref name="sap_absinthism">{{Cite journal |last1=Padosch |first1=Stephan A |last2=Lachenmeier |first2=Dirk W. |last3=Kröner |first3=Lars U. |year=2006 |title=Absinthism: a fictitious 19th century syndrome with present impact |journal=Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy |volume=1 |page=14 |doi=10.1186/1747-597X-1-14 |pmc=1475830 |pmid=16722551 |doi-access=free}}</ref> The chemical compound ], which is present in the spirit in trace amounts, was blamed for its alleged harmful effects. By 1915, absinthe had been banned in the United States and in much of Europe, including ], the ], ], ], and ], yet it has not been demonstrated to be any more dangerous than ordinary spirits. Recent studies have shown that absinthe's psychoactive properties (apart from those attributable to alcohol) have been exaggerated.<ref name="sap_absinthism" /> | |||

| The French word ''absinthe'' can refer either to the liquor, or to the actual wormwood plant (''grande absinthe'' being ], and ''petite absinthe'' being ]). The word derives from the Latin ''absinthium'', which is in turn a stylization of the Greek ''αψινθιον'' (apsinthion). Some claim that the word means "undrinkable" in Greek, but it may instead be linked to the ] root ''spand'' or ''aspand'', or the variant ''esfand'', which may have been, rather, ], a variety of ], another famously bitter herb. That this particular plant was commonly burned as a protective offering may suggest that its origins lie in the reconstructed ] root ''*spend'', meaning "to perform a ritual" or "make an offering". Whether the word was a borrowing from Persian into Greek, or rather from a common ancestor is unclear. <ref> Retrieved 30-Mar-2006</ref> | |||

| A revival of absinthe began in the 1990s, following the adoption of modern European Union food and beverage laws that removed long-standing barriers to its production and sale. By the early 21st century, nearly 200 brands of absinthe were being produced in a dozen countries, most notably in France, Switzerland, ], ], the Netherlands, ], and the ]. | |||

| Absinth is a spelling variation of absinthe often seen in central Europe, because so many Bohemian-style products use it many groups see it as synonymous with ]. | |||

| == |

==Etymology== | ||

| ]'s ''Green Muse'' (1895): a poet succumbs to the Green Fairy.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The main herbs used are ], florence ] and ], often called the holy trinity. Many other herbs may be used as well, such as, ], ], and petite wormwood (''Artemisia pontica'' or ''Roman wormwood''). Various recipes also include ] root, ], ] leaves, ], ], ], ], and various mountain herbs. | |||

| The French word {{lang|fr|absinthe}} can refer either to the alcoholic beverage, or less commonly, to the actual wormwood plant. Absinthe is derived from the ] {{lang|la|absinthium}}, which in turn comes from the Greek {{lang|grc|ἀψίνθιον}} {{transl|grc|apsínthion}} {{gloss|wormwood}}.<ref>{{LSJ|a)yi/nqion|ἀψίνθιον|shortref}}.</ref> The use of ''Artemisia absinthium'' in a drink is attested in ]' '']'' (936–950){{clarify|date=June 2024}}, where Lucretius indicates that a drink containing wormwood is given as medicine to children in a cup with honey on the brim to make it drinkable.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Lucretius |title=Titi lvcreti cari de rervm natvra liber qvartvs |url=http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/lucretius/lucretius4.shtml |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080820124849/http://thelatinlibrary.com/lucretius/lucretius4.shtml |archive-date=20 August 2008 |access-date=2008-09-17 |language=la}}</ref> Some{{who?|date=September 2024}} argue that the word means "undrinkable" in Greek, but it may instead be linked to the Persian root ''spand''{{which lang?|date=September 2024}} or ''aspand'',{{which lang?|date=September 2024}} or the variant ''esfand'',{{which lang?|date=September 2024}} which meant '']'', also called Syrian rue, although it is not actually a variety of ], another famously bitter herb.{{citation needed|date=October 2022}} That ''Artemisia absinthium'' was commonly burned as a protective offering may suggest that its origins lie in the reconstructed ] root {{lang|ine-x-proto|spend}}, meaning "to perform a ritual" or "make an offering". Whether the word was a borrowing from Persian into Greek, or from a common ancestor of both, is unclear.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Absinthe etymology |url=http://gernot-katzers-spice-pages.com/engl/Arte_vul.html#absinthe |access-date=2012-02-12 |website=Gernot Katzer's Spice Pages}}</ref> Alternatively, the Greek word may originate in a ] word, marked by the non-Indo-European consonant complex {{lang|grc|-νθ}} {{transl|grc|-nth}}. Alternative spellings for absinthe include ''absinth'', ''absynthe'', and ''absenta''. ''Absinth'' (without the final ''e'') is a spelling variant most commonly applied to absinthes produced in central and eastern Europe, and is specifically associated with ]es.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Absinth: Short explanation of the adoption of the ''absinth'' spelling by Bohemian producers |url=http://www.feeverte.net/faq-absinthe.html#B16 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080917015134/http://www.feeverte.net/faq-absinthe.html |archive-date=17 September 2008 |access-date=2008-09-17 |url-status=usurped |website=La Fee Verte Absinthe}}</ref> | |||

| A simple ] in alcohol of wormwood without distillation produces an extremely bitter drink, due to the presence of the water-soluble absinthine, one of the most bitter substances known. Authentic recipes call for ] after the primary maceration and before the secondary or "coloring" maceration. The distillation of wormwood, anise, and Florence fennel first produces a colorless distillate which leaves the ] at around 82% ]. It can be left clear, called a ''Blanche'' or ''la Bleue'' (used for bootleg Swiss absinthe) , or the well-known green color of the beverage can be imparted either artificially or with ] by steeping petite wormwood, hyssop, and melissa in the liquid. After this process, the resulting product is reduced with water to the desired percentage of alcohol. Over time and exposure to light the chlorophyll will break down, causing the drink to go from emerald green to yellow green to brown. Pre-ban and vintage absithes are often of a distinct amber colour as a result of this process. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Non-traditional varieties are made by cold-mixing herbs, essences or oils in alcohol, with the distillation process omitted. Often called 'oil mixes', these types of absinthe are not necessarily bad, though they are generally considered to be of lower quality than properly distilled absinthe and often carry a distinct bitter aftertaste. | |||

| The precise origin of absinthe is unclear. The medical use of wormwood dates back to ancient Egypt and is mentioned in the ], around 1550 BC. Wormwood extracts and wine-soaked wormwood leaves were used as remedies by the ancient Greeks. Moreover, some evidence exists of a wormwood-flavoured wine in ancient Greece called {{transl|grc|absinthites oinos}}.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |year=1940 |title=ἀψινθίτης |encyclopedia=A Greek–English Lexicon |url=http://lsj.translatum.gr/%E1%BC%80%CF%88%CE%B9%CE%BD%CE%B8%CE%AF%CF%84%CE%B7%CF%82 |access-date=2013-03-09 |last1=Liddell |first1=Henry George |last2=Scott |first2=Robert}}</ref> | |||

| The first evidence of absinthe, in the sense of a distilled spirit containing green anise and fennel, dates to the 18th century. According to popular legend, it began as an all-purpose patent remedy created by Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, a French doctor living in ], Switzerland, around 1792 (the exact date varies by account). Ordinaire's recipe was passed on to the Henriod sisters of Couvet, who sold it as a medicinal elixir. By other accounts, the Henriod sisters may have been making the elixir before Ordinaire's arrival. In either case, a certain Major Dubied acquired the formula from the sisters in 1797 and opened the first absinthe distillery named Dubied Père et Fils in Couvet with his son Marcellin and son-in-law Henry-Louis Pernod. In 1805, they built a second distillery in ], France, under the company name Maison ].<ref name="faqiii">{{Cite web |title=Absinthe FAQ III |url=http://www.archivespirits.com/absinthe_FAQ3.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140821043824/http://www.archivespirits.com/absinthe_FAQ3.html |archive-date=2014-08-21 |access-date=August 20, 2014}}</ref> Pernod Fils remained one of the most popular brands of absinthe until the drink was banned in France in 1914.{{cn|date=September 2024}} | |||

| Alcohol makes up the majority of the drink and is extremely high, between 45% and 89.9%,<ref>. Retrieved 18-Mar-2006.</ref> though there is no historical evidence that any commercial vintage absinthe was higher than 74%. Given the high strength and low alcohol solubility of many of the herbal components, absinthe is usually not imbibed "straight," but consumed after a fairly elaborate preparation ]. | |||

| ===Growth of consumption=== | |||

| Historically, there were five grades of absinthe: ''ordinaire'', ''demi-fine'', ''fine'', ''supérieure'' and ''Suisse'' (which does not denote origin), in order of increasing alcoholic strength. Most absinthes contain somewhere between 60% to 75% alcohol. It is said to improve materially with storage. In the late 19th century, cheap brands of absinthe were occasionally ] by profiteers with ], ], ], or other ]s to impart the green color, and with ] trichloride to produce the ''louche'' effect; this addition of toxic chemicals is quite likely to have contributed to absinthe's reputation as a hallucination-inducing or otherwise harmful beverage. | |||

| ] | |||

| Absinthe's popularity grew steadily through the 1840s, when it was given to French troops in Algeria as a malaria preventive,<ref>{{Cite news |last=Lemons |first=Stephen |date=2005-04-07 |title=Behind the green door |url=http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/2005-04-07/news/behind-the-green-door/print |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121020114635/http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/2005-04-07/news/behind-the-green-door/print |archive-date=2012-10-20 |access-date=2008-09-18 |work=Phoenix New Times}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Delahaye |first=Marie-Claude |title=L'absinthe: son historie |date=January 1, 2001 |publisher=Musee de L'Absinthe |isbn=2951531621 |language=fr}}</ref> and the troops brought home their taste for it. Absinthe became so popular in bars, bistros, cafés, and cabarets by the 1860s that the hour of 5 pm was called {{lang|fr|l'heure verte}} {{gloss|the green hour}}.<ref name="StClair">{{Cite book |last=St. Clair |first=Kassia |title=The Secret Lives of Colour |publisher=John Murray |year=2016 |isbn=978-1473630819 |location=London |page=217 |oclc=936144129}}</ref> It was favoured by all social classes, from the wealthy bourgeoisie to poor artists and ordinary working-class people. By the 1880s, mass production had caused the price to drop sharply, and the French were drinking {{convert|36|e6L}} per year by 1910, compared to their annual consumption of almost {{convert|5|e9L}} of wine.<ref name=faqiii/><ref>{{Cite news |date=1911-11-05 |title=High Price of Wines due to Short Crops |url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1911/11/05/104880913.pdf |access-date=2008-10-20 |work=] |quote='1910, was no less than 1,089 millions of gallons.' '162 bottles per head'}}</ref> | |||

| ===Homemade kits=== | |||

| There are numerous “recipes” for homemade absinthe floating around on the internet, many of which revolve around soaking or mixing a kit or store-bought herbs and wormwood extract with high-proof liquor such as ] or ]. Even though these do-it-yourself absinthe kits have gained a lot of popularity, it is simply not possible to produce absinthe in this manner. Absinthe distillation, just like the production of any fine liquor, is a science in itself and requires great expertise and care to properly manage. | |||

| Absinthe was exported widely from France and Switzerland and attained some degree of popularity in other countries, including Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Czech Republic. It was never banned in Spain or Portugal, and its production and consumption have never ceased. It gained a temporary spike in popularity there during the early 20th century, corresponding with the Art Nouveau and Modernism aesthetic movements.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Verte |first=Peter |title=The Fine Spirits Corner |url=http://www.absinthebuyersguide.com/Articles/finespirits_peterverte.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080505084044/http://www.absinthebuyersguide.com/Articles/finespirits_peterverte.html |archive-date=5 May 2008 |access-date=2008-04-11 |website=Absinthe Buyers Guide}}</ref> | |||

| Besides being highly unpleasant to drink and a pale impression of authentic distilled absinthe, these homemade concoctions can sometimes be downright poisonous. Many of these recipes call for the usage of liberal amounts of wormwood extract, or essence of wormwood in hopes to increase the believed ] effects. Consuming essential oils will not produce a high, but can be very dangerous. Wormwood extract can cause ] and death due to excessive amounts of thujone, which in large quantities acts as a ] ]. Wormwood extract should ''never'' be consumed straight. | |||

| New Orleans has a cultural association with absinthe and is credited as the birthplace of the ], perhaps the earliest absinthe cocktail. The Old Absinthe House bar on ] began selling absinthe in the first half of the 19th century. Its Catalan lease-holder, Cayetano Ferrer, named it the Absinthe Room in 1874 due to the popularity of the drink, which was served in the Parisian style.<ref name=va/> It was frequented by ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="va">{{Cite web |title=The Virtual Absinthe Museum: Absinthe in America{{snd}}New Orleans |url=http://www.oxygenee.com/absinthe-america/neworleans.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120908150432/http://www.oxygenee.com/absinthe-america/neworleans.html |archive-date=8 September 2012 |access-date=1 December 2016 |website=Oxygenee}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=History |url=http://www.ruebourbon.com/oldabsinthehouse/history.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161225212755/http://www.ruebourbon.com/oldabsinthehouse/history.html |archive-date=25 December 2016 |access-date=1 December 2016 |website=Rue Bourbon |department=Old Absinthe House}}</ref> | |||

| ==Preparation== | |||

| ] | |||

| Traditionally absinthe is poured into a glass over which a specially designed, slotted spoon is placed. A ] cube is then deposited in the bowl of the spoon. Ice cold ] is poured or dripped over the sugar until the drink is diluted 3:1 to 5:1. During this process, the components that are not soluble in water come out of solution and cloud the drink; that milky ] is called the ''louche'' (''Fr.'' "opaque" or "shady" pronounced "loosh"). <ref> step by step images showing the traditional ritual Retrieved 31-Mar-2006</ref> | |||

| ===Bans=== | |||

| With increased popularity the absinthe fountain came into use. A large jar of ice-water on a base with spigots. It allowed a number of drinks to be prepared at once and with a hands free drip, patrons were able to socialize while louching a glass. | |||

| {{see also|#Absinthism}} | |||

| Absinthe became associated with violent crimes and social disorder, and one modern writer claims that this trend was spurred by fabricated claims and smear campaigns, which he claims were orchestrated by the temperance movement and the wine industry.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Wittels |first1=Betina J. |title=Absinthe: The Exquisite Elixir |last2=Breaux |first2=T.A. |date=2017 |publisher=Fulcrum Publishing |isbn=978-1682750018 |page=45}}</ref> One critic claimed: | |||

| Although many bars served absinthe in standard glasses there are a number of glasses specifically made for absinthe. Having a dose line, bulge or bubble in the lower portion of the glass marking how much absinthe should be poured into it (often around 1 oz). | |||

| {{blockquote|Absinthe makes you crazy and criminal, provokes epilepsy and tuberculosis, and has killed thousands of French people. It makes a ferocious beast of man, a martyr of woman, and a degenerate of the infant, it disorganizes and ruins the family and menaces the future of the country.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Barnaby |first=Conrad III |author-link=Barnaby Conrad III |title=Absinthe History in a Bottle |publisher=] |year=1988 |isbn=978-0811816502 |page=116}}</ref>}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The precise origin of absinthe is unclear. According to popular legend, absinthe began as an all-purpose patent ] created by Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, a French doctor living in Couvet, ], around 1792 (the exact date varies by account). Ordinaire's recipe was passed on to the Henriod sisters of Couvet, who sold absinthe as a medicinal ]. In fact, by other accounts, the Henriod sisters may have already been making the elixir before Ordinaire's arrival. In either case, one Major Dubied in turn acquired the formula from the sisters and, in 1797, with his son Marcellin and son-in-law Henry-Louis Pernod, opened the first absinthe distillery, Dubied Père et Fils, in Couvet. In 1805, they built a second distillery in ], under the new company name, Maison Pernod Fils.<ref> Retrieved 4-April-2006</ref> | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Absinthe's popularity grew steadily until the 1840s when absinthe was given to French ]s as a ] preventative. When the troops returned home they brought their taste for absinthe with them and it became popular at ] and ]s. | |||

| ]'', by Edgar Degas, 1876]] | |||

| By the 1860s, absinthe had become so popular that in most ]s and ]s 5 p.m. signaled ''l'heure verte'' ("the green hour"). Still, it remained expensive and was favored mainly by the ] and eccentric bohemian artists. By the 1880s, however, the price had dropped significantly, the market expanded, and absinthe soon became the drink of France. By 1910, the French were consuming 36 million ] of absinthe per year. | |||

| ]'s 1876 painting {{lang|fr|]}} can be seen at the ] epitomising the popular view of absinthe addicts as sodden and benumbed, and ] described its effects in his novel {{lang|fr|]}}.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Zola |first=Émile |title=L'Assommoir |publisher=Penguin |year=1970 |series=Penguin Classics |page=411 |translator-last=Tancock |translator-first=Leonard |lang=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Ban=== | |||

| Spurred by the ] and winemakers' associations, absinthe was publicized in connection with several violent crimes supposedly committed under the direct influence of the drink. This, combined with rising hard liquor consumption due to the ] during the 1880s and 1890s, effectively labelled absinthe as a social menace. Its critics said that "it makes people crazy and criminal, it turns men into brutes and threatens the future of our times." ]'s 1876 painting, ''L'absinthe'' (''The Absinthe Drinkers'') (now at the ]) epitomized the popular view of absinthe "addicts" as sodden and benumbed; ] described their serious intoxication in his novel '']''. | |||

| In 1905, Swiss farmer ] murdered his family and attempted to kill himself after drinking absinthe. Lanfray was an alcoholic who had drunk a lot of wine and brandy before the killings, but that was overlooked or ignored, and blame for the murders was placed solely on his consumption of two glasses of absinthe.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Conrad |first=Barnaby III |author-link=Barnaby Conrad III |title=Absinthe History in a Bottle |publisher=Chronicle Books |year=1988 |isbn=0811816508 |pages=1–4}}</ref>{{Sfn|St. Clair|2016|pp=218–219}} The Lanfray murders were the tipping point in this hotly debated topic, and a subsequent petition collected more than 82,000 signatures to ban it in Switzerland. A referendum was held on 5 July 1908.<ref name="NS">{{Cite book |last1=Nohlen |first1=Dieter |author-link=Dieter Nohlen |title=Elections in Europe: A Data Dandbook |last2=Stöver |first2=P. |year=2010 |isbn=978-3832956097 |page=1906|publisher=Nomos }}</ref> It was approved by voters,<ref name=NS/> and the prohibition of absinthe was written into the Swiss constitution. | |||

| The Lanfray murders spelled the last straw for absinthe. In 1905 it was reported that Jean Lanfray murdered his family and attempted to kill himself after drinking absinthe. The fact that he was an alcoholic who had drunk considerably after the two glasses of absinthe in the morning was forgotten and the murders were blamed solely on absinthe. A petition to ban absinthe in Switzerland was quickly signed by over 82,000 people. | |||

| In 1906, Belgium and Brazil banned the sale and distribution of absinthe, although these were not the first countries to take such action. It had been banned as early as 1898 in the colony of the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Carvajal |first=Doreen |date=2004-11-27 |title=Fans of absinthe party like it's 1899 |url=http://www.iht.com/articles/2004/11/27/wbdrink_ed3_.php |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060228042837/http://www.iht.com/articles/2004/11/27/wbdrink_ed3_.php |archive-date=2006-02-28 |access-date=2008-09-18 |website=International Herald Tribune}}</ref> The Netherlands banned it in 1909, Switzerland in 1910,<ref name="US Brewers' Assoc 1916 pg82">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sPooAAAAYAAJ&q=Absinth&pg=PA82 |title=The Year Book of the United States Brewers' Association |date=1916 |publisher=United States Brewers' Association |page=82 |language=en}}</ref> the United States in 1912, and France in 1914.<ref name="US Brewers' Assoc 1916 pg82" /> | |||

| In ], the prohibition of absinthe was even written into the constitution in 1907, following a popular initiative. ] came next, banning absinthe in 1909, followed by the United States in 1912 and finally ] in 1915. The prohibition of absinthe in France led to the growing popularity of '']'' and '']'', anise-flavored liqueurs that do not use wormwood. In Switzerland it drove absinthe underground. Evidence suggests small home clandestine distillers have been producing absinthe since the ban, focusing on La Bleues as it was easier to hide a clear product. | |||

| The prohibition of absinthe in France eventually led to the popularity of ], and to a lesser extent, ], and other anise-flavoured spirits that do not contain wormwood. Following the conclusion of the First World War, production of the Pernod Fils brand was resumed at the Banus distillery in ], Spain (where absinthe was still legal),<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Absinthe Buyer's Guide |url=http://www.feeverte.net/guide/historic-absinthe-brands/pernod_fils_tarragona_circa_19/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070914040506/http://www.feeverte.net/guide/historic-absinthe-brands/pernod_fils_tarragona_circa_19/ |archive-date=2007-09-14 |url-status=usurped |website=La Fée Verte}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Vintage Absinthe Pernod Tarragona |url=https://www.alandia.de/absinthe-tarragona.jpg |access-date=1 September 2023 |website=Alandia}}</ref> but gradually declining sales saw the cessation of production in the 1960s.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Verte |first=Peter |title=The Fine Spirits Corner |url=http://www.absinthebuyersguide.com/Articles/finespirits_peterverte.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080924190524/http://www.absinthebuyersguide.com/Articles/finespirits_peterverte.html |archive-date=24 September 2008 |access-date=2008-09-18 |website=Absinthe Buyer's Guide}}</ref> In Switzerland, the ban served only to drive the production of absinthe underground. ] home distillers produced colourless absinthe ('']''), which was easier to conceal from the authorities. Many countries never banned absinthe, notably the United Kingdom, where it had never been as popular as in continental Europe. | |||

| ===Modern revival=== | ===Modern revival=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| British importer ] began to import ] from the Czech Republic in the 1990s, as the UK had never formally banned it, and this sparked a modern resurgence in its popularity. It began to reappear during a revival in the 1990s in countries where it was never banned. Forms of absinthe available during that time consisted almost exclusively of Czech, Spanish, and Portuguese brands that were of recent origin, typically consisting of ] products. Connoisseurs considered these of inferior quality and not representative of the 19th-century spirit.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Modern Revival of Absinthe |url=http://www.absinthe.se/absinthe-facts-and-history/modern-revival-of-absinthe |access-date=2012-02-12 |website=Absinthe.se}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Absinthe History and FAQ VI |url=http://www.thujone.info/absinthe_FAQ6.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120226174026/http://www.thujone.info/absinthe_FAQ6.html |archive-date=2012-02-26 |access-date=2012-02-12 |website=Thujone.info}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Rogers |first=Tim |date=17 November 2010 |title=Absinthe: Unmasking the green fairy |url=http://www.praguepost.com/tempo/6441-unmasking-the-green-fairy.html |access-date=2012-02-12 |website=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Sullum |first=Jacob |date=1 August 2005 |title=The search for real absinthe: like Tinkerbell, the Green Fairy lives only if we believe in her |url=https://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+search+for+real+absinthe%3A+like+Tinkerbell,+the+Green+Fairy+lives...-a0133838997 |access-date=1 December 2016 |magazine=] |via=]}}</ref> In 2000, ] became the first commercial absinthe distilled and bottled in France since the 1914 ban,<ref>{{Cite news |date=2001-07-27 |title=Strong stuff |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/4264304/Strong-stuff.html |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220111/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/4264304/Strong-stuff.html |archive-date=2022-01-11 |access-date=2012-07-24 |work=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Pursglove |first=Anna |date=4 August 2000 |title=What's your poison? |url=https://www.standard.co.uk/goingout/restaurants/whats-your-poison-6341255.html |access-date=1 December 2016 |work=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=La Fée – The Definitive Range |url=http://www.cellartrends.co.uk/spirits/lafee_absinthe.php |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110623033804/http://www.cellartrends.co.uk/spirits/lafee_absinthe.php |archive-date=2011-06-23 |access-date=2012-07-24 |website=Cellar Trends}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Baker |first=Phil |title=The Dedalus Book of Absinthe |year=2001 |isbn=1873982941 |page=165|publisher=Dedalus }}</ref><ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Difford |first=Simmon |date=May-June 2009 |title=Absinthe Tale |magazine=Class Magazine |pages=88–93}}</ref> but it is now one of dozens of brands that are produced and sold within France. | |||

| In the 1990s an importer, ], realized that there was no ] law prohibiting absinthe sale (it was never banned there)—other than the standard regulations governing ]. ], a ] distillery founded in 1920, began manufacturing Hill's Absinth, a Bohemian-style absinth, sparking the modern resurgence in absinthe's popularity. | |||

| In the Netherlands, the restrictions were challenged by Amsterdam wineseller Menno Boorsma in July 2004, thus confirming the legality of absinthe once again. Similarly, Belgium lifted its long-standing ban on January 1, 2005, citing a conflict with the adopted food and beverage regulations of the single European Market. In Switzerland, the constitutional ban was repealed in 2000 during an overhaul of the national constitution, although the prohibition was written into ordinary law, instead. That law was later repealed, and it was made legal on March 1, 2005.<ref>{{Cite magazine |last1=Lachenmeier |first1=D.W. |last2=Emmert |first2=J. |last3=Sartor |first3=G. |date=2005 |title=Authentification of Absinthe – The Bitter Truth over a Myth |magazine=Deutsch Lebensmittel Rundschau |pages=100–104}}</ref> | |||

| It had also never been banned in ] or ], where it continues to be made. Likewise, the former Spanish and Portuguese New World colonies, especially ], allow the sale of absinthe and it has retained popularity through the years. | |||

| The drink was never officially banned in Spain, although it began to fall out of favour in the 1940s and almost vanished into obscurity. ] has seen significant resurgence since 2007, when one producer established operations there. Absinthe has never been illegal to import or manufacture in Australia,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Absinthe Laws |url=http://www.absinthe101.com/laws.html |access-date=11 March 2013 |website=absinthe101.com}}</ref> although importation requires a permit under the Customs (Prohibited Imports) Regulation 1956 due to a restriction on importing any product containing "oil of wormwood".<ref>{{Citation |title=Customs (Prohibited Imports) Regulations 1956 |url=http://www7.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/legis/cth/consol_reg/cir1956432/sch8.html |access-date=2022-12-31 |archive-date=31 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221231172541/http://www7.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/legis/cth/consol_reg/cir1956432/sch8.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> In 2000, an amendment made all wormwood species prohibited herbs for food purposes under Food Standard 1.4.4. Prohibited and Restricted Plants and Fungi. However, this amendment was found inconsistent with other parts of the pre-existing Food Code,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Australian Food Standards PDF |url=http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/code/proposals/Documents/P254_Final_Assessment.pdf |access-date=1 December 2016 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Standard 1.4.4 – Prohibited and Restricted Plant and Fungi |url=http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/_srcfiles/Standard_1_4_4_Prohib_plants_v74.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060110161131/http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/_srcfiles/Standard_1_4_4_Prohib_plants_v74.pdf |archive-date=10 January 2006 |access-date=1 December 2016 |publisher=]}}</ref> and it was withdrawn in 2002 during the transition between the two codes, thereby continuing to allow absinthe manufacture and importation through the existing permit-based system. These events were erroneously reported by the media as it having been reclassified from a ''prohibited'' product to a ''restricted'' product.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2003-10-22 |title=Just add water |url=https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/just-add-water-20031022-gdhmr6.html |access-date=2022-12-31 |work=] |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| France never repealed the 1915 law, but in 1988, a law was passed to clarify that only beverages that do not comply with ] regulations with respect to ] content, or beverages that call themselves "absinthe" explicitly, fall under that law. This has resulted in the re-emergence of French absinthes, now labelled ''spiritueux à base de plantes d'absinthe'' ("wormwood-based spirits"). Interestingly, as the 1915 law regulates only the sale of absinthe in France but not its production, many manufacturers also produce variants destined for exports which are plainly labeled "absinthe." ], launched in 2000, was the first brand of absinthe distilled and bottled in France since the 1915 ban, initially mainly for export from France, but now one of over twenty French "spiritueux ... d'absinthe" available in Paris and other French cities. | |||

| ] | |||

| In ] this law was successfully challenged by ] wineseller Menno Boorsma in July 2004, making absinthe once more legal. Subsequently, the government in May 2005 repealed this law. ], as part of an effort to simplify its laws, removed its absinthe law on the first of January 2005, citing (as the Dutch judge) European food regulations as sufficient to render the law unnecessary (and indeed, in conflict with the spirit of the Single European Market). | |||

| In 2007, the French brand ] became the first genuine absinthe to receive a Certificate of Label Approval <!-- (COLA) --> for import into the United States since 1912,<ref>{{Cite web |title=TTB Online{{snd}}COLAs Online{{snd}}Application Detail |url=https://www.ttbonline.gov/colasonline/viewColaDetails.do?action=publicDisplaySearchBasic&ttbid=07064000000076 |access-date=2009-02-24 |quote=Brand Name: LUCID ... Approval Date: 03/05/2007}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=TTB Online{{snd}}COLAs Online{{snd}}Application Detail |url=https://www.ttbonline.gov/colasonline/viewColaDetails.do?action=publicDisplaySearchBasic&ttbid=07058001000192 |access-date=2009-02-24 |quote=Brand Name: KUBLER ... Approval Date: 05/17/2007}}</ref> following independent efforts by representatives from Lucid and Kübler to overturn the ].<ref>{{Cite news |last=Skrzycki |first=Cindy |date=16 October 2007 |title=A Notorious Spirit Finds Its Way Back to Bars |url=http://www.bevlaw.com/files/absinthe/washington%20post%20skrzycki.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090305110554/http://www.bevlaw.com/files/absinthe/washington%20post%20skrzycki.pdf |archive-date=5 March 2009 |access-date=2009-02-24 |newspaper=] |via=bevlaw.com}}</ref> In December 2007, St. George Absinthe Verte produced by ] of ] became the first brand of American-made absinthe produced in the United States since the ban.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Finz |first=Stacy |date=2007-12-05 |title=Alameda distiller helps make absinthe legitimate again |url=https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Alameda-distiller-helps-make-absinthe-legitimate-3300453.php |access-date=2022-12-31 |work=] |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Wells |first=Pete |date=2007-12-05 |title=A Liquor of Legend Makes a Comeback |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/05/dining/05absi.html |access-date=2022-12-31 |work=The New York Times |language=en-US |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> Since that time, other micro-distilleries have started producing small batches in the United States. | |||

| In Switzerland the ban on absinthe was repealed in 2000 during a general overhaul of the constitution, but the prohibition was written into ordinary law instead. Later that law was also repealed, so from ], absinthe is again legal in its country of origin, after nearly a century of prohibition. | |||

| The French Absinthe Ban of 1915 was repealed in May 2011 following petitions by the {{lang|fr|Fédération Française des Spiritueux}}, which represents French distillers,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Official FFS Press Release confirming the repeal of the 1915 French Absinthe Ban: Article 175; point 20 |url=http://www.heureverte.com/images/stories/20110518-ffs-heureverte.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924025932/http://www.heureverte.com/images/stories/20110518-ffs-heureverte.pdf |archive-date=2015-09-24}}</ref> and the ] voted to repeal the prohibition in April 2011.<ref name=Hebblethwaite>{{cite web |last=Hebblethwaite |first=Cordelia |title=Absinthe in France: Legalising the 'green fairy' |website=] |date=4 May 2011 |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-13159863 |access-date=16 October 2024}}</ref> | |||

| It is once again legal to produce and sell absinthe in practically every country where alcohol is legal, the one major exception being the United States. It is not, however, illegal to possess or consume absinthe in the United States. | |||

| In Switzerland, the village of ], ], near ], became the focal point of production and promotion of the liquor after a ban of nearly 100 years was lifted. The national Maison de l'Absinthe (Absinthe Museum) is located in the former courthouse, where absinthe distillers were formerly proscecuted.<ref name=cuisine>{{cite web |title=Culinary Travel: Maison de l'Absinthe in Môtiers |website=CUISINE HELVETICA |date=25 June 2015 |url=https://cuisinehelvetica.com/2015/06/25/absinthe_museum/ |access-date=16 October 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=La maison – Maison de l'Absinthe |website=Maison de l'Absinthe – le lieu incontournable de l'Absinthe |date=28 June 2024 |url=https://maison-absinthe.fr/maison-absinthe-presentation/ |language=fr |access-date=16 October 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ====Cruise mystery==== | |||

| In January 2006, a widely published ] ] article echoed the press's sensationalistic absinthe scare of a century earlier. It was reported that on the night he disappeared, ] (the Greenwich, Connecticut, man who in July 2005 vanished from aboard the ]'s ''Brilliance of the Seas'' while on his honeymoon cruise) and other passengers drank a bottle of absinthe. The story noted the modern revival and included numerous quotes from various sources, suggesting that absinthe remains a serious and dangerous hallucinogenic drug: | |||

| The 21st century has seen new types of absinthe, including various frozen preparations, which have become increasingly popular.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Rose |first=Brent |date=2012-06-08 |title=Absinthe Pops: The Frozen Treat That Will Melt Your Face |url=https://gizmodo.com/5916728/absinthe-pops-the-frozen-treat-that-will-melt-your-face |access-date=2012-06-12 |website=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Stewart |first=Alice |date=2012-05-31 |title=Ice lolly made from holy water and absinthe goes on sale |url=http://www.digitalspy.com/odd/news/a384711/ice-lolly-made-from-holy-water-and-absinthe-goes-on-sale.html |access-date=2012-06-12 |website=Digital Spy |department=Weird News}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Campion |first=Vikki |date=2012-06-08 |title=Sydney's small bar revolution is teaching people a new way to drink |url=http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/sydneys-small-bar-revolution-is-teachiing-people-a-new-way-to-drink/story-e6freuy9-1226388947593 |access-date=2012-06-12 |work=]}}</ref> | |||

| :''"In large amounts it would certainly make people see strange things and behave in a strange manner," said Jad Adams, author of the book, "Hideous Absinthe: A History of the Devil in a Bottle." "It gives people different, unusual ideas which they wouldn't have had on their own accord because of its stimulative effect on the mind."'' | |||

| ==Production== | |||

| :''"Absinthe is banned in the United States because of harmful neurological effects caused by a toxic chemical called thujone, said Michael Herndon, spokesman for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.''<ref>Christoffersen, John. . ''Greenwich Time'', 23-Jan-2006. and . ''Boston Globe'', 22-Jan-2006. Two slightly different edits of the same Associated Press wire service story. Retrieved 5-Mar-2006.</ref> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 200 | |||

| <!-- Image 1 --> | |||

| | image1 = Koehler1887-PimpinellaAnisum.jpg | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = ], one of three main herbs used in the production of absinthe | |||

| <!-- Image 2 --> | |||

| | image2 = Koeh-164.jpg | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = ] | |||

| <!-- Image 3 --> | |||

| | image3 = Foeniculum vulgare - Köhler–s Medizinal-Pflanzen-148.jpg | |||

| | alt3 = | |||

| | caption3 = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| Most countries have no legal definition for absinthe, whereas the method of production and content of spirits such as ], ], and ] are globally defined and regulated. Therefore, producers are at liberty to label a product as "absinthe" or "absinth" without regard to any specific legal definition or quality standards. | |||

| Producers of legitimate absinthes employ one of two historically defined processes to create the finished spirit – distillation or cold mixing. In the sole country (Switzerland) that does possess a legal definition of absinthe, distillation is the only permitted method of production.<ref>{{cite web |title=Aide-Mémoire: production d'absinthe. |url=https://www.eav.admin.ch/dam/eav/fr/dokumente/Website/Themen/Herstellung/Herstellung%20Absinth.pdf.download.pdf/Merkblatt_Produktion_Absinth_fr.pdf |access-date=2016-12-02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161202233233/https://www.eav.admin.ch/dam/eav/fr/dokumente/Website/Themen/Herstellung/Herstellung%20Absinth.pdf.download.pdf/Merkblatt_Produktion_Absinth_fr.pdf |archive-date=2016-12-02 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| The story also noted: "Defenders of the drink say it is safe and its harmful effects a myth." | |||

| ===Distilled absinthe=== | |||

| Jad Adams and Ted Breaux were interviewed on ] about this issue. Ted Breaux had this to say, | |||

| Distilled absinthe employs a method of production similar to that of high-quality gin. Botanicals are initially macerated in distilled base alcohol before being redistilled to exclude bitter principles, and impart the desired complexity and texture to the spirit. | |||

| :''"one thing we know is that absinthe, old and new, does not contain a lot of thujone. And what we know, from certain scientific studies, which have been published in the past year or so, is that, first of all, thujone is not present in any absinthe in sufficient concentration to cause any type of deleterious effects in humans."''<ref>. MSNBC, 23-Jan-2006. Retrieved 5-Mar-2006.</ref> | |||

| The distillation of absinthe first yields a colourless distillate that leaves the ] at around 72% ABV. The distillate may be reduced and bottled clear, to produce a ''Blanche'' or ''la Bleue'' absinthe, or it may be coloured to create a ''verte'' using natural or artificial colouring. | |||

| Traditional absinthes obtain their green color strictly from the ] of whole herbs, which is extracted from the plants during the secondary ]. This step involves ] plants such as ], ], and ] (among other herbs) in the distillate. Chlorophyll from these herbs is extracted in the process, giving the drink its famous green color.<ref>{{cite web |title=How to make Absinthe |url=https://www.alandia.de/absinthe-blog/how-to-make-absinthe/ |website=Alandia Absinthe Blog |date=2 November 2016 |access-date=1 September 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ==Controversy== | |||

| ], "The Absinthe Drinker." An unapologetic look at a street bum.]] | |||

| It was thought that excessive absinthe-drinking led to effects which were specifically worse than those associated with over-indulgence in other forms of alcohol — which is bound to have been true for some of the less-scrupulously adulterated products, creating a condition called ''absinthism''. Undistilled wormwood essential oil contains a substance called ], which is an ] (and can cause ]) in extremely high doses, and the supposed ill effects of the drink were blamed on that substance in 19th century studies. | |||

| This step also provides a herbal complexity that is typical of high-quality absinthe. The natural coloring process is considered critical for absinthe ageing, since the chlorophyll remains chemically active. The chlorophyll serves a similar role in absinthe that tannins do in wine or brown liquors.{{Unreliable source? |date=September 2010}}<ref>{{Unreliable source? |date=September 2010}}{{cite web |author=Kallisti |url=http://www.feeverte.net/recipes.html |title=Historical Recipes |publisher=Feeverte.net |access-date=2010-08-14 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100920222149/http://feeverte.net/recipes.html |archive-date=2010-09-20 |url-status=usurped }}</ref> | |||

| The effects of absinthe have been described by artists as mind opening, and even ] and by prohibitionists as turning good people mad and desolate. Both are exaggerations. Sometimes called "secondary effects," the most commonly reported experience is a "clear-headed" feeling of inebriation, said to be caused by the thujone. The ] and individual reaction to the herbs makes these secondary effects subjective and minor compared to the ] effects of alcohol. | |||

| After the coloring process, the resulting product is diluted with water to the desired percentage of alcohol. The flavor of absinthe is said to improve materially with storage, and many distilleries, before the ban, aged their absinthe in settling tanks before bottling. | |||

| More recent studies have shown that very little of the thujone present in wormwood actually makes it into a properly distilled absinthe, even one re-created using historical recipes and methods. Most proper absinthe, both vintage and modern, are naturally within the EU limits.<ref>Hutton, Ian. and . Retrieved 5-Mar-2006.</ref> A recent French distiller has had to add pure ] of wormwood to make a "high-thujone" variant of his product. It can remain in higher amounts in oils produced by other methods than distillation, or when wormwood is macerated and not distilled, especially when the plant stems are used, where thujone content is the highest. | |||

| ===Cold mixed absinthe=== | |||

| A study in the ''Journal of Studies on Alcohol'' concluded that a high concentration of thujone in alcohol has negative effects on attention performance. It slowed down ] and subjects concentrated their attention in the central field of vision. Medium doses did not produce a noticeably different effect than plain alcohol. The high dose of thujone in this study was larger than what one can get from current "high thujone" absinthe before becoming too drunk to notice. As most people describe the effects of absinthe as a more lucid and aware drunk, this suggests that thujone alone is not the cause of these effects. | |||

| Many modern absinthes are produced using a cold-mix process. This inexpensive method of production does not involve distillation, and is regarded as inferior for the same reasons that give cause for cheaply compounded gin to be legally differentiated from distilled gin.<ref name="EU Spirit Definitions">{{cite web |title=Regulation (EU) 2019/787 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the definition, description, presentation and labelling of spirit drinks, the use of the names of spirit drinks in the presentation and labelling of other foodstuffs, the protection of geographical indications for spirit drinks, the use of ethyl alcohol and distillates of agricultural origin in alcoholic beverages, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 110/2008 |url=https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019R0787&qid=1654112224840 |website=EUR-Lex |access-date=1 June 2022}}</ref> The cold mixing process involves the simple blending of flavouring essences and artificial colouring in commercial alcohol, in similar fashion to most flavoured ]s and inexpensive liqueurs and cordials. Some modern cold-mixed absinthes have been bottled at strengths approaching 90% ABV. Others are presented simply as a bottle of plain alcohol with a small amount of powdered herbs suspended within it. | |||

| The lack of a formal legal definition in most countries to regulate the production and quality of absinthe has enabled cheaply made products to be falsely presented as traditional in production and composition. In Switzerland, the only country with a formal legal definition of absinthe, any absinthe product not obtained by maceration and distillation or coloured artificially cannot be sold as absinthe.<ref name="Swiss Absinthe Regulation">{{cite web |title=Ordonnance du DFI sur les boissons |url=https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2017/220/fr |website=Fedlex |publisher=Swiss Confederation |access-date=1 June 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ==Czech, or bohemian absinth== | |||

| Often called Bohemian-style, Czech-style, anise-free absinthe or just absinth (without the 'e'), bohemian absinth is produced mainly in the ] where it gets its ] moniker. It doesn't contain anise, fennel or many of the other herbs normally found in the more traditional absinthes produced in countries such as France and Switzerland, and can be extremely bitter. Often the only similarity with its French and Swiss counterparts is the use of wormwood and a high alcohol content, and for all intents and purposes it should be considered a completely different product. In most cases, Czech- or Bohemian-style absinths are not distilled spirits, but rather high-proof alcohol or vodka which has been cold-mixed with herbal extracts and artificial colouring. | |||

| ===Ingredients=== | |||

| Since there are currently few legal definitions for absinthe, producers have taken advantage of its romantic associations and psychoactive reputation to market their products under a similar name. Many Czech-style producers heavily market thujone content, exploiting the many myths and half-truths that surround thujone even though none of these types of absinth contain enough thujone to cause any noticeable effect. It is claimed absinth has been produced in the Czech Republic since the 1920s. The Hills company even claims they use the same eighty year old recipe. There is no evidence to support either claim. <ref>. The Virtual Absinthe Museum. Retrieved 5-Mar-2006.</ref> As far as anyone can tell, Czech absinth is a modern product originating in the 1990s. | |||

| Absinthe is traditionally prepared from a distillation of neutral alcohol, various herbs, spices, and water. Traditional absinthes were redistilled from a white grape spirit (or '']''), while lesser absinthes were more commonly made from alcohol from grains, beets, or potatoes.<ref>"La Maison Pernod Fils a Pontarlier", E. Dentu (1896, p. 10)</ref> The principal botanicals are ], ], and ], which are often called "the holy trinity".<ref>{{Cite news |last=Chu |first=Louisa |date=2008-03-12 |title=Crazy for absinthe |newspaper=] |url=http://www.chicagotribune.com/features/food/chi-drink_absinthe_12mar12,0,3796843.story |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080314091509/http://www.chicagotribune.com/features/food/chi-drink_absinthe_12mar12%2C0%2C3796843.story |archive-date=2008-03-14 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Many other herbs may be used as well, such as petite wormwood ('']'' or Roman wormwood), ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web |last=Duplais |first=MM. |title=A Treatise on the Manufacture and Distillation of Alcoholic Liquors |url=http://wormwoodsociety.flannestad.com/texts/duplais_236_247.pdf|work=Distiller's Manual |publisher=The Wormwood Society |access-date=9 October 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150413174828/http://wormwoodsociety.flannestad.com/texts/duplais_236_247.pdf |archive-date=13 April 2015}}</ref> | |||

| One early recipe was included in 1864's '']''. It directed the maker to "Take of the tops of wormwood, four pounds; root of angelica, calamus aromaticus, aniseed, leaves of dittany, of each one ounce; alcohol, four gallons. Macerate these substances during eight days, add a little water, and distil by a gentle fire, until two gallons are obtained. This is reduced to a proof spirit, and a few drops of the oil of aniseed added."<ref>{{cite book |last=Abbott |first=Edward |title=The English and Australian Cookery Book |url=https://archive.org/details/b21505524 |date=1864}}</ref> | |||

| The Czech or Bohemian-style absinth lacks many of the oils in absinthe that create the louche and a modern ritual involving fire was created to take this into account. Typically, absinth is added to a glass and a sugar cube on a spoon is placed over it. The sugar cube is soaked in absinth then lit on fire. The cube is then dropped into the absinth setting it on fire and water is added till the fire goes out, normally a 1:1 ratio. The crumbling sugar can provide a minor simulation of the louche seen in traditional absinthe and the lower water ratio enhances effects of the high strength alcohol. Care should be taken when lighting any high proof spirit on fire. | |||

| ===Alternative colouring=== | |||

| It is sometimes claimed that the Czech/Bohemian ritual which involves fire is old and traditional, this is false. This method of preparing absinth was in fact invented in the 1990s as a marketing stunt but has since been accepted by many as historical fact, largely because this method is featured in several contemporary movies. Amongst many of the more traditional absinthe enthusiasts this method of preparing absinthe is looked down upon and seen as little more than cheap theatrics designed to impress tourists. <ref> step by step images showing the czech fire ritual Retrieved 31-Mar-2006</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Adding to absinthe's negative reputation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, unscrupulous makers of the drink omitted the traditional colouring phase of production in favour of adding toxic copper salts to artificially induce a green tint. This practice may be responsible for some of the alleged toxicity historically associated with this beverage. Many modern-day producers resort to other shortcuts, including the use of artificial food coloring to create the green color. Additionally, at least some cheap absinthes produced before the ban were reportedly adulterated with poisonous ], reputed to enhance the ].<ref name="lafeeabsinthe.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.lafeeabsinthe.com/absinthe-news-newsmenu-131/205-class-magazine-may-2009 |title=Class Mag May/June 2009 La Fee |publisher=Lafeeabsinthe.com |access-date=2 December 2016 |archive-date=2 December 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161202172106/http://www.lafeeabsinthe.com/absinthe-news-newsmenu-131/205-class-magazine-may-2009 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| ==Cultural impact== | |||

| The legacy of absinthe as a mysterious and addictive, mind-altering drink continues to this day. Absinthe has been seen or featured in ], movies, video, music and literature. The modern absinthe revival has had an effect on its portrayal. It is often shown as an unnaturally glowing green liquid which is set on fire before drinking, even though traditionally neither is true. | |||

| Absinthe may also be naturally coloured pink or red using rose or ] flowers.<ref>{{cite web |title=Absinthe – the Green (or pink or red) Fairy |url=http://distillique.co.za/distilling_shop/blog/121-absinthe-the-green-or-pink-or-red-fairy |work=Distillique |access-date=June 4, 2016 |archive-date=August 3, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160803203029/http://distillique.co.za/distilling_shop/blog/121-absinthe-the-green-or-pink-or-red-fairy |url-status=dead }}</ref> This was referred to as a ''rose'' (pink) or ''rouge'' (red) absinthe. Only one historical brand of rose absinthe has been documented.<ref name="Rose Absinthe">{{cite web |title=Rosinette Absinthe Rose Oxygénée |url=http://www.museeabsinthe.com/absintheAFFICHES1.html |website=Musée Virtuel de l'Absinthe |publisher=Oxygenee (France) Ltd. |access-date=25 July 2016 |archive-date=6 November 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211106015820/http://www.museeabsinthe.com/absintheAFFICHES1.html |url-status=dead }}</ref>{{Clear}} | |||

| ===Arts & literature=== | |||

| Numerous artists and writers living in France during the late 19th and early 20th century were noted absinthe drinkers and featured absinthe in their work. These include ], ], ] and ]. Van Gogh spent a good deal of time painting in cafés but feared the bohemian life still was damaging. During a fit in 1888 Van Gogh cut off his ear lobe and gave it to a brothel wench. Often said to be absinthe induced there is no evidence to suggest this. According to Gauguin, Van Gogh had been acting unstable almost a week before the incident and had flung the only absinthe Gauguin had seen him order, before drinking it. Art historians still debate of the exact cause or causes of Van Gogh's behavior. Degas' painting "L'Absinthe" (1876) portrayed grim absinthe drinkers in a cafe. Years later it set off a flurry in the london art world. The grim realism of "L'Absinthe," a theme popular with bohemian artists, was seen as a disease by London art critics and a lesson against alcohol and the French in general. ] depicted absinthe in different media, including the paintings "Woman Drinking Absinthe" (1901) and "Bottle of Pernod and Glass" (1912), and the sculpture "Absinthe Glass" (1914). ] has been quoted as saying, "What difference is there between a glass of absinthe and a sunset?"<ref></ref> <ref>"Absinthe History in a bottle" Barnaby Conrad III (1988)</ref> | |||

| === |

===Bottled strength=== | ||

| ] | |||

| In '']'' starring ] and ], Prince Vlad (Oldman) drinks absinthe with Mina/Elizabeta (Ryder) in a London restaurant. ] is shown drinking absinthe in '']'' (1995). In '']'' (1997), ]'s character is shown drinking absinthe; the drink's legendary effects are highlighted in the plot. In '']'' (2001), Inspector Abberline (]) mixes opium with absinthe to make an addictive drink. '']'' (2001) portrayed absinthe as the drink of the Bohemian revolution. Absinthe was also used indirectly as the subject of an American independent ] film, '']''. In '']'' (2002), absinthe is prepared by ]'s character, who also gives a speech on its effects and ingredients. In '']'' (2004), several teenagers purchase a bottle of absinthe at a nightclub in ]. In '']'' (2004), Van Helsing finds the Frankenstein monster under a windmill full of absinthe bottles. In the remake of '']'' (2004), Liz (]) plies the main character (]) with absinthe prepared in contemporary style with a sugar cube set on fire. | |||

| Absinthe was historically bottled at 45–74% ABV. Some modern Franco–Suisse absinthes are bottled at up to 83% ABV,<ref name="eichelberger-83.2">{{cite web |url=http://www.absinth-guide.de/forum/thema2161.html |title=Absinth-Guide.de |access-date=February 8, 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150509001630/http://www.absinth-guide.de/forum/thema2161.html |archive-date=May 9, 2015}}</ref><ref name="eichelberger">{{cite web |url=https://www.absinthes.com/en/themag/news-absinthes/the-10-strongest-absinthes-on-absinthes-com-4331 |title=Absinthes.com |access-date=2018-10-20 |archive-date=2018-10-21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181021111534/https://www.absinthes.com/en/themag/news-absinthes/the-10-strongest-absinthes-on-absinthes-com-4331 |url-status=dead }}</ref> while some modern, ] ] absinthes are bottled at up to 89.9% ABV.<ref>{{cite web |title=Absinthe with 89.9% ABV. |url=https://www.alandia.de/absinthe-89.9.jpg |website=Alandia |access-date=1 September 2023}}</ref> | |||

| Absinthe made an appearance in the ] television series '']'', imbibed by a mysterious blind seer, as well as in the ] crime drama '']'' where it is incorrectly stated the distillation process makes absinthe toxic. Absinthe was also featured in the episode "The Big Lockout" of the British comedy series ], where character ] says, "What do they say, absinthe, the drink that makes you want to kill yourself." In the second series of ] '']'', Ella (]) offers absinthe to the popular students as means to break the ice when she enrolls in their school. She warns the character of Leon (]) that it "...rots your brain." | |||

| === |

===Kits=== | ||

| The modern-day interest in absinthe has spawned a rash of absinthe kits from sellers claiming they produce homemade absinthe. Kits often call for soaking herbs in ] or alcohol, or adding a liquid concentrate to vodka or alcohol to create an ] absinthe. Such practices usually yield a harsh substance that bears little resemblance to the genuine article, and are considered inauthentic by any practical standard.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://wormwoodsociety.org/ABSfaq.html#swill |title=About absinthe kits |publisher=wormwoodsociety |access-date=2008-09-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080419112813/http://www.wormwoodsociety.org/ABSfaq.html#swill |archive-date=2008-04-19 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Some concoctions may even be dangerous, especially if they call for a potentially poisonous inclusion of herbs, oils, or extracts. In at least one documented case, a person suffered ] after drinking 10 ml of pure wormwood oil.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Evolution in action!|url=https://www.gumbopages.com/nejm.html|access-date=2022-12-31|website=www.gumbopages.com}}</ref> | |||

| ] has a song titled "Absinthe" on her 2006 album "]". Progressive power metal band ] released "Absinthe And Rue" on their self-titled debut album (1994). The ]-founded ensemble ] released an ethereal album entitled ''Absinthe'' in 1996. A collaboration between ] and ] produced the 2001 ] '']'', followed up with the live album '']''. The absinthe ritual appears in the ] video "]". ], the keyboardist from the band ], is often pictured with a bottle of absinthe, most notably in their 2003 album, '']''. The black metal band ] released a song on 2004's '']'', called "Absinthe with Faust"; its opening line is, "Pour the emerald wine into crystal glasses." ] boasts of having written an entire album on absinthe. The famous "One More Saturday Night" logo from the Grateful Dead featured a skeleton swigging absinthe. In the opening number of '']'', "No One Mourns The Wicked", a green elixir turns Elphaba '']''. ] released a song on 1999's Against The Night album entitled "Absinthe Makes the Heart Grow Fonder". | |||

| ===Alternatives=== | |||

| In baking<ref>{{cite book |author1=Laura Halpin Rinsky |author2=Glenn Rinsky |title=The Pastry Chef's Companion: A Comprehensive Resource Guide for the Baking and Pastry Professional |url=https://archive.org/details/pastrychefscompa00rins |url-access=limited |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |location=Chichester |year=2009 |page= |isbn=978-0470009550 |oclc=173182689}}</ref> and in preparing the classic New Orleans-style ] ],<ref name="Simon">{{cite book |last=Simon |first=Kate |title=Absinthe Cocktails: 50 Ways to Mix with the Green Fairy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_6PR9Bh80zIC&pg=PA33 |year=2010 |publisher=Chronicle Books |isbn=978-1452100302 |page=33}}</ref> anise-flavored liqueurs and ] have often been used as a substitute if absinthe is unavailable. | |||

| ==Preparation== | |||

| {{Main|Absinthiana}} | |||

| {{See also|Ouzo effect}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The traditional French preparation involves placing a sugar cube on top of a specially designed slotted spoon, and placing the spoon on a glass filled with a measure of absinthe. Iced water is poured or dripped over the sugar cube to mix the water into the absinthe. The final preparation contains 1 part absinthe and 3–5 parts water. As water dilutes the spirit, those components with poor water solubility (mainly those from ], ], and ]) come out of solution and ]. The resulting milky ] is called the '']'' (Fr. ''opaque'' or ''shady'', IPA ). The release of these dissolved essences coincides with a perfuming of herbal aromas and flavours that "blossom" or "bloom," and brings out subtleties that are otherwise muted within the neat spirit. This reflects what is perhaps the oldest and purest method of preparation, and is often referred to as the ''French Method''. | |||

| The ''Bohemian method'' is a recent invention that involves fire, and was not performed during absinthe's peak of popularity in the ]. Like the French method, a sugar cube is placed on a slotted spoon over a glass containing one shot of absinthe. The sugar is soaked in alcohol (usually more absinthe), then set ablaze. The flaming sugar cube is then dropped into the glass, thus igniting the absinthe. Finally, a shot glass of water is added to douse the flames. This method tends to produce a stronger drink than the French method{{Citation needed|date=December 2024}}. A variant of the Bohemian method involves allowing the fire to extinguish on its own. This variant is sometimes referred to as "cooking the absinthe" or "the flaming green fairy". The origin of this burning ritual may borrow from a coffee and brandy drink that was served at Café Brûlot, in which a sugar cube soaked in brandy was set aflame.<ref name="lafeeabsinthe.com"/> Most experienced absintheurs do not recommend the Bohemian Method and consider it a modern gimmick, as it can destroy the absinthe flavour and present a fire hazard due to the unusually high alcohol content present in absinthe.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wormwoodsociety.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=474:-how-to-buy-and-drink-good-quality-absinthe&catid=16:wormwood-society-in-the-media&Itemid=233 |title=How to buy and drink good quality absinthe |publisher=Wormwoodsociety.org |access-date=2012-07-14 |archive-date=2012-05-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120506001352/http://www.wormwoodsociety.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=474:-how-to-buy-and-drink-good-quality-absinthe&catid=16:wormwood-society-in-the-media&Itemid=233 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| In 19th century Parisian cafés, upon receiving an order for an absinthe, a waiter would present the patron with a dose of absinthe in a suitable glass, sugar, absinthe spoon, and a ] of iced water.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.oxygenee.com/absinthe-faq/faq3.html |title=Professors of Absinthe Historic account of preparation at a bar. |access-date=2008-09-18 |publisher=Oxygenee Ltd. |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080905100814/http://oxygenee.com/absinthe-faq/faq3.html |archive-date=5 September 2008 |url-status=dead}}</ref> It was up to the patron to prepare the drink, as the inclusion or omission of sugar was strictly an individual preference, as was the amount of water used. As the popularity of the drink increased, additional accoutrements of preparation appeared, including the ], which was effectively a large jar of iced water with ]s, mounted on a lamp base. This let drinkers prepare a number of drinks at once{{snd}}and with a hands-free drip, patrons could socialise while louching a glass. | |||

| Although many bars served absinthe in standard glassware, a number of glasses were specifically designed for the French absinthe preparation ritual. Absinthe glasses were typically fashioned with a dose line, bulge, or bubble in the lower portion denoting how much absinthe should be poured. One "dose" of absinthe ranged anywhere around 2–2.5 fluid ounces (60–75 ml). | |||

| In addition to being prepared with sugar and water, absinthe emerged as a popular cocktail ingredient in both the United Kingdom and the United States. By 1930, dozens of fancy cocktails that called for absinthe had been published in numerous credible bartender guides.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Savoy Cocktail Book |last=Dorelli |first=Peter |year=1999 |publisher=Anova Books |isbn=978-1862052963}}{{Page needed |date=June 2011}}</ref> One of the most famous of these libations is ]'s "]" cocktail, a tongue-in-cheek concoction that contributed to a 1935 collection of celebrity recipes. The directions are: "Pour one ] absinthe into a Champagne glass. Add iced Champagne until it attains the proper opalescent milkiness. Drink three to five of these slowly."<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/03/dining/03curi.html |title=Trying to Clear Absinthe's Reputation |access-date=2008-09-17 |first=Harold |last=McGee |date=2008-01-03 |work=The New York Times}}</ref> | |||

| ==Styles== | |||

| Most categorical alcoholic beverages have regulations governing their classification and labelling, while those governing absinthe have always been conspicuously lacking. According to popular treatises from the 19th century, absinthe could be loosely categorised into several grades (''ordinaire'', ''demi-fine'', ''fine'', and ''Suisse''{{snd}}the latter does not denote origin), in order of increasing alcoholic strength and quality. Many contemporary absinthe critics simply classify absinthe as ''distilled'' or ''mixed'', according to its production method. And while the former is generally considered far superior in quality to the latter, an absinthe's simple claim of being 'distilled' makes no guarantee as to the quality of its base ingredients or the skill of its maker. | |||

| ] | |||

| * '''''Blanche''''' absinthe ("white" in French, also referred to as ''la Bleue'' in Switzerland) is bottled directly following distillation and reduction, and is uncoloured (clear). Blanches tend to have a clean, smooth flavour with strongly individuated tasting notes. The name ''la Bleue'' was originally a term used for Swiss bootleg absinthe, which was bottled colourless so as to be visually indistinct from other spirits during the era of absinthe prohibition, but has become a popular term for post-ban Swiss-style absinthe in general. Blanches are often lower in alcohol content than vertes, though this is not necessarily so; the only truly differentiating factor is that blanches are not put through a secondary maceration stage, and thus remain colourless like other distilled liquors. | |||

| * '''''Verte''''' absinthe ("green" in French, sometimes called ''la fée verte'') begins as a blanche, and is altered by a secondary maceration stage, in which a separate mixture of herbs is steeped into the clear distillate before bottling. This confers an intense, complex flavor as well as a ] green hue.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://bevvy.co/articles/everything-you-need-to-know-about-absinthe/2303 |title=Everything You Need to Know About Absinthe |access-date=2016-10-24 |last=Shenton |first=Will |date=2016-02-24 |publisher=Bevvy}}</ref> Vertes represent the prevailing type of absinthe that was found in the 19th century. Vertes are typically more alcoholic than blanches, as the high amounts of ] conferred during the secondary maceration only remain ] at lower concentrations of water, thus vertes are usually bottled at closer to still strength. Artificially colored green absinthes may also be claimed to be ''verte'', though they lack the characteristic herbal flavors that result from maceration in whole herbs. | |||

| * '''Absenta''' ("absinthe" in Spanish) is sometimes associated with a regional style that often differed slightly from its French cousin. Traditional absentas may taste slightly different due to their use of ],{{Unreliable source? |date=September 2010}}<ref>{{Unreliable source? |date=September 2010}}{{cite web |url=http://www.absinthebuyersguide.com/Articles/finespirits_peterverte.html |title=Fine Spirits Corner |first=Peter |last=Verte |publisher=absinthe buyers guide |access-date=2008-09-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080924190524/http://www.absinthebuyersguide.com/Articles/finespirits_peterverte.html |archive-date=24 September 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref> and often exhibit a characteristic citrus flavour.{{Unreliable source? |date=September 2010}}<ref>{{Unreliable source? |date=September 2010}}{{cite web |url=http://www.feeverte.net/guide/country/spain/ |title=The Absinthe Buyer's Guide: Modern & Vintage Absinthe Reference: Spain Archives |publisher=La Fee Verte |access-date=2008-09-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080915145208/http://www.feeverte.net/guide/country/spain/ |archive-date=2008-09-15 |url-status=usurped }}</ref> | |||

| * '''''Hausgemacht''''' (German for ''home-made'', often abbreviated as ''HG''{{Citation needed|date=December 2021}}) refers to clandestine absinthe (not to be confused with the Swiss ''La Clandestine'' brand) that is home-distilled by hobbyists. It should not be confused with ]. Hausgemacht absinthe is produced in tiny quantities for personal use and not for the commercial market. Clandestine production increased after absinthe was banned, when small producers went underground, most notably in Switzerland. Although the ban has been lifted in Switzerland, some clandestine distillers have not legitimised their production. Authorities believe that high taxes on alcohol and the mystique of being underground are likely reasons.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.swissinfo.org/eng/swissinfo.html?siteSect=107&sid=6586791&cKey=1143621269000 |title=Absinthe bootleggers refuse to go straight |publisher=Swiss info |date=2006-03-11 |access-date=2008-09-17 |archive-date=2008-06-24 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080624085123/http://www.swissinfo.org/eng/swissinfo.html?siteSect=107&sid=6586791&cKey=1143621269000 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||