| Revision as of 21:55, 20 April 2006 editIP Address (talk | contribs)1,183 edits rv condescensions and eccentric arrogance← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:57, 10 December 2024 edit undoMaidenhair (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users928 edits Correct source of cite web template maintenance message and correct wikilink | ||

| (605 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|People of mixed Gaelic and Norse heritage}} | |||

| The '''Norse-Gaels''' were a people who dominated much of the ] region and western ] for a large part of the ], whose aristocracy were mainly of ]n origin, but as a whole exhibited a great deal of ] and ] cultural ]. They are generally known by the Gaelic name which they themselves used, of which "Norse-Gaels" is a translation. This term is subject to are large range of variations depending on chronological and geographical differences in the ], i.e. '''Gall Gaidel''', '''Gall Gaidhel''', '''Gall Gaidheal''', '''Gall Gaedil''', '''Gall Gaedhil''', '''Gall Gaedhel''', '''Gall Goidel''', etc, etc. Other modern translations used include '''Scoto-Norse''', '''Hiberno-Norse''', and '''Foreign Gaels'''. | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=October 2013}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2023}} | |||

| {{multiple image|caption_align=center|header_align=center | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 250 | |||

| | header = Norse settlement | |||

| | image1 = Kingdom of Mann and the Isles-en.svg | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = | |||

| | image2 = Viking Ireland.png | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

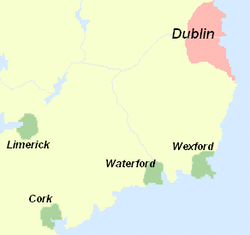

| | caption2 = Regions of Scotland, Ireland and Man settled by the Norse | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Norse–Gaels''' ({{langx|sga|Gall-Goídil}}; {{langx|ga|Gall-Ghaeil}}; {{langx|gd|Gall-Ghàidheil}}, 'foreigner-Gaels'; {{langx|non|Gaddgeðlar}}) were a people of mixed ] and ] ancestry and culture. They emerged in the ], when ] who ] and ] became ] and intermarried with ]. The Norse–Gaels dominated much of the ] and ] regions from the ] to ]. They founded the ] (which included the ] and the ]), the ], the ] (which is named after them), and briefly (939–944 AD) ruled the ]. The most powerful Norse–Gaelic dynasty were the ] or House of Ivar. | |||

| Over time, the Norse–Gaels became ever more ] and disappeared as a distinct group. However, they left a lasting influence, especially in the Isle of Man and ], where most placenames are of Norse–Gaelic origin. Several ]s have Norse–Gaelic roots, such as ], ], ] and ].<!--three names is enough for the lead--> The elite mercenary warriors known as the ] ({{lang|ga|gallóglaigh}}) emerged from these Norse–Gaelic clans and became an important part of Irish warfare. The Viking ] also influenced the Gaelic {{lang|gd|]}} and {{lang|ga|]}}, which were used extensively until the 17th century. Norse–Gaelic surnames survive today and include ], ], ], and ].<!--Four example names are enough for the lead.--> | |||

| The Norse-Gaels originated in Viking colonists of Ireland and Scotland who became subject to the process of ], whereby starting as early as the ], they adopted the ], and many other Gaelic customs, such as dress. The terminology was used both by native Irish and native Scots who wished to alienate them, and by the Norse-Gaels themselves who wished to stress their Scandinavian heritage and their links with Norway and other parts of the Scandinavian world. Gaelicized Scandinavians dominated the Irish Sea region until the ] era of the ], founding long-lasting kingdoms, such as the Kingdom of ], ], ], ] and ]. The ], a Lordship which lasted until the ], as well as many other Gaelic rulers of Scotland and Ireland, traced their descent from Norse-Gaels. | |||

| ==Name== | |||

| The specific region Norse-Gaels settled in ] was once all of one piece and after the ] called ], the land which was composed of the Irish Sea's coast from the ] (although some went to ]) and throughout ] into the ]. ] is often used to distinguish between these origins and Danish colonisation from the ] coast (see ]). Although the Norwegian element is undisputed, the Celtic side is more ] by tradition and continues to be an English subculture throughout the region. What he calls the "]" '''North Midlands''' is discussed at depth in ]'s '']'', heavily overlapping the "]" cultural area of ''']''' for all intents and purposes. Professor Fischer expounds upon the Norse surnames and villages of the Quakers who were poor dalesmen and lived in compact, stone-built homes (much as in Ireland and the Scottish Western Isles across the water). Historian Hugh Barbour believes there were innate differences between the locals and their Norman overlords for many centuries, that the commoners were Evangelical while their landlords were Recusant. Barbour is convinced that the Norman system of feudal manors was always resented, compared to the preferred Norse method of "]s". | |||

| The meaning of {{lang|ga|Gall-Goídil}} is 'Foreign Gaels' and although it can in theory mean any Gael of foreign origin, it was used of Gaels (i.e. Gaelic-speakers) with some kind of Norse identity.{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} This term is subject to a large range of variations depending on chronological and geographical differences in the ], e.g. Gall Gaidel, Gall Gaidhel, Gall Gaidheal, Gall Gaedil, Gall Gaedhil, Gall Gaedhel, Gall Goidel, Gall Ghaedheil, etc. The modern term in Irish is Gall-Ghaeil or Gall-Ghaedheil, while the Scottish Gaelic is Gall-Ghàidheil.<ref>]. . University of Aberdeen.</ref> | |||

| The Norse–Gaels often called themselves Ostmen or Austmen, meaning East-men, a name preserved in a corrupted form in the ] area known as ] which comes from Austmanna-tún (homestead of the Eastmen).{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} In contrast, they called Gaels Vestmenn (West-men) (see ] and ]).{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| Other terms for the Norse–Gaels are '''Norse-Irish''', '''Hiberno-Norse''' or '''Hiberno-Scandinavian''' for those in Ireland, and '''Norse-Scots''' or '''Scoto-Norse''' for those in Scotland. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ] ({{circa}} 1042)]] | |||

| ]'s impression of a Norse–Gaelic ruler of ], Lord of the Isles]] | |||

| The Norse–Gaels originated in ] colonies of Ireland and Scotland, the descendants of intermarriage between Norse immigrants and the Gaels. As early as the 9th century, many colonists (except the ] who settled in ]) intermarried with native ] and adopted the ] as well as many Gaelic customs. Many left their original worship of ] and converted to ], and this contributed to the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.asncvikingage.com/key-written-sources#:~:text=The%20Saga%20of%20the%20People,upon%20by%20subsequent%20Icelandic%20scholars | title=Key Primary Sources }}</ref> | |||

| Gaelicised Scandinavians dominated the region of the Irish Sea until the ] era of the 12th century. They founded long-lasting kingdoms, such as those of ], ], and ],<ref name=Charles-Edwards>{{cite book|last=Charles-Edwards |first=T. M. |title=Wales and the Britons, 350–1064 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AK_yn7Q3_x0C&pg=PA573 |date=2013 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=9780198217312 |page=573 |quote=The Gallgaedil of 12th-century Galloway appear to have been predominantly Gaelic-speakers...remained a people separate from the Scots...Their separateness seems to have been established not by language but by their links with Man, Dublin, and the ''Innsi Gall'', the Hebrides: they were part of a Hiberno-Norse Irish-Sea world}}</ref> as well as taking control of the Norse colony at ]. | |||

| ===Ireland=== | |||

| {{main|History of Ireland (800–1169)|Early Scandinavian Dublin}} | |||

| The Norse are first recorded in Ireland in 795 when they sacked ]. This island is located off of the Northeast coast of Ireland and contains with it many gravesites with formal evidence of existence.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.vikingeskibsmuseet.dk/en/professions/education/the-viking-age-geography/the-vikings-in-the-west/ireland|url-access= |title=The vikings in Ireland|department=Professions|website=]|location=]|language=en-gb|access-date=2024-12-10|quote=] is the site of the first recorded Viking attack on Ireland in 795 AD. A number of Viking graves, some with magnificent grave goods, and a Hiberno-Norse coin hoard from the 1040's has been found here}}</ref> ] states that the first raid on this island was known as the ''Loscad Rechrainne o geinntib,'' otherwise known as 'the burning of Rechru by heathens.'<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Annals of Ulster |url=https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T100001A/index.html |access-date=2024-12-10 |website=celt.ucc.ie}}</ref>{{Verification needed|date=December 2024}} Sporadic raids then continued until 832, after which they began to build fortified settlements throughout the country. Norse raids continued throughout the 10th century, but resistance to them increased. The Norse established independent kingdoms in ], ], ], ] and ]. These kingdoms did not survive the subsequent Norman invasions, but the towns continued to grow and prosper. | |||

| The term Ostmen was used between the 12th and 14th centuries by the English in Ireland to refer to Norse–Gaelic people living in Ireland. Meaning literally "the men from the east" (i.e. Scandinavia), the term came from the ] word austr or east. The Ostmen were regarded as a separate group from the English and Irish and were accorded privileges and rights to which the Irish were not entitled. They lived in distinct localities; in Dublin they lived outside the city walls on the north bank of the ] in Ostmentown, a name which survives to this day in corrupted form as ]. It was once thought that their settlement had been established by Norse–Gaels who had been forced out of Dublin by the English but this is now known not to be the case. Other groups of Ostmen lived in Limerick and Waterford. Many were merchants or lived a partly rural lifestyle, pursuing fishing, craft-working and cattle raising. Their roles in Ireland's economy made them valuable subjects and the English Crown granted them special legal protections. These eventually fell out of use as the Ostmen assimilated into the English settler community throughout the 13th and 14th centuries.<ref name="Laing">{{cite book|title=Early People of Britain and Ireland: An Encyclopedia, Volume II|editor-last=Snyder|editor-first=Christopher A.|last=Valante|first=Mary|pages=430–31|publisher=Greenwood Publishing |date=2008 |isbn=9781846450297}}</ref> | |||

| ===Scotland=== | |||

| {{main|Scandinavian Scotland}} | |||

| The ], whose sway lasted until the 16th century, as well as many other Gaelic rulers of Scotland and Ireland, traced their descent from Norse–Gaelic settlements in northwest Scotland, concentrated mostly in the ].<ref>Bannerman, J., ''The Lordship of the Isles'', in Scottish Society in the Fifteenth Century, ed. J. M. Brown, 1977.</ref> | |||

| ] (Scottish Gaelic: Na Guinnich) is a Highland Scottish clan associated with lands in northeastern Scotland, including Caithness, Sutherland and, arguably, the Orkney Isles. Clan Gunn is one of the oldest Scottish Clans, being descended from the Norse Jarls of Orkney and the Pictish Mormaers of Caithness. | |||

| The Hebrides are to this day known in ] as {{lang|gd|Innse Gall}}, 'the islands of foreigners';<ref>] (2000) ''Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland''. Edinburgh. Mainstream. {{ISBN|1840183764}}. p. 104</ref> the irony of this being that they are one of the last strongholds of Gaelic in Scotland. | |||

| The MacLachlan clan name means 'son of the Lakeland' believed to be a name for Norway. It has its Scottish clan home on eastern Loch Fyne under Strathlachlan forest. The name and variations thereof are common from this mid/southern Scottish area to Irish Donegal to the extreme west. | |||

| ===Iceland and the Faroes=== | |||

| It is recorded in the {{lang|is|]}} that there were ] or ] (Gaelic monks) in ] before the Norse. This appears to tie in with comments of ] and is given weight by recent archaeological discoveries. The ] and the ] by the Norse included many Norse–Gael settlers as well as slaves and servants. They were called ] (Western men), and the name is retained in ] in the Faroes and the ] off the Icelandic mainland.{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| A number of Icelandic personal names are of Gaelic origin, including ], ], ] and ] (from ], ], ] and ]).<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ellipsis.cx/~liana/names/drafts/irish-norse.html |access-date=22 September 2021 |title=Old Norse Forms of Early Irish Names |first=Brian M. |last=Scott |date=2003}}</ref> ], an Icelandic village, was named after ]. A number of placenames named after the papar exist on Iceland and the Faroes. | |||

| According to some circumstantial evidence, ], seen as the founder of the Norse Faroes, may have been a Norse Gael:<ref>Schei, Liv Kjørsvik & ] (2003) ''The Faroe Islands''. Birlinn.</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|According to the Faereyinga Saga... the first settler in the Faroe Islands was a man named Grímur Kamban – ''Hann bygdi fyrstr Færeyar'', it may have been the land taking of Grímur and his followers that caused the anchorites to leave... the nickname Kamban is probably Gaelic and one interpretation is that the word refers to some physical handicap (the first part of the name originating in the Old Gaelic '''camb''' crooked, as in Campbell '''Caimbeul''' Crooked-Mouth and Cameron '''Camshron''' Crooked Nose), another that it may point to his prowess as a sportsman (presumably of '''camóige / camaige''' hurley – where the initial syllable also comes from '''camb'''). Probably he came as a young man to the Faroe Islands by way of Viking Ireland, and local tradition has it that he settled at Funningur in Eysturoy.}} | |||

| == Mythology == | |||

| ] (1891) suggested that the ] of ] came from the heritage of the Norse–Gaels.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Zimmer |first=Heinrich |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M6tJAAAAYAAJ&dq=fianna+zimmer+fiandr&pg=PA15 |title=Keltische Beiträge III, in: Zeitschrift für deutsches Alterthum und deutsche Litteratur |date=1891 |publisher=Weidmannsche Buchhandlung |pages=15ff |language=de}}</ref> He suggested the name of the heroic '']'' was an Irish rendering of Old Norse ''fiandr'' "enemies", and argued that this became "brave enemies" > "brave warriors".<ref name=":0" /> He also noted that ]'s ] is similar to the Norse tale '']''.<ref>{{harvp|Scowcroft|1995|p=154}}</ref><ref>Scott, Robert D. (1930), ''{{URL|1=https://books.google.com/books?id=-WDYAAAAMAAJ&q=Sigurd|2=The thumb of knowledge in legends of Finn, Sigurd, and Taliesin}}'', New York: Institute of French Studies</ref> Linguist ], author of the ''Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic'', derives the name ''fíanna'' from reconstructed ] ''*wēnā'' (a ]),<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=wēnā |encyclopedia=Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic |date=2009 |last=Matasović |first=Ranko |author-link=Ranko Matasović |publisher=Brill Academic Publishers |page=412}}</ref> while linguist Kim McCone derives it from Proto-Celtic ''*wēnnā'' (wild ones).<ref>McCone, Kim (2013). "The Celts: questions of nomenclature and identity", in ''Ireland and its Contacts''. ]. p.26</ref> | |||

| ==Modern names and words== | |||

| Even today, many surnames particularly connected with Gaeldom are of Old Norse origin, especially in the Hebrides and Isle of Man. Several Old Norse words also influenced modern Scots English and Scottish Gaelic, such as ''bairn'' (child) from the Norse ''barn'' (a word still used in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Iceland).{{Citation needed|date=June 2022}} | |||

| ===Surnames=== | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! '''Gaelic''' | |||

| ! '''Anglicised form''' | |||

| ! '''"Son of-"''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mac Asgaill | |||

| | ], ], Castell, Caistell | |||

| | Áskell | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mac Amhlaibh<br />(confused with native Gaelic Mac Amhlaidh, Mac Amhalghaidh) | |||

| | ], ], ], ], MacCamley, McCamley, Kewley | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mac Corcadail | |||

| | ], ], ], Corkhill, Corkell, ], McCorkle, McQuorkell, McOrkil | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ], MacCotter, ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mac DubhGhaill, Ó DubhGhaill, | |||

| | Doyle, McDowell, MacDougal | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mag Fhionnain | |||

| | ] | |||

| | “the fair” (possibly in reference to someone with Norse ancestry)<ref>{{Cite web |title=Surname Database: Gannon Last Name Origin |url=https://www.surnamedb.com/Surname/Gannon |access-date=2024-04-29 |website=The Internet Surname Database |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mac Ìomhair | |||

| | ], ], ], ], ], etc. | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mac Raghnall | |||

| | ], Crennel | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mac Shitrig<ref> Retrieved on 23 April 2008</ref> | |||

| | MacKitrick, McKittrick | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ]<ref> Retrieved on 23 April 2008</ref> | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Forenames=== | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! '''Gaelic''' | |||

| ! '''Anglicised form''' | |||

| ! '''Norse equivalent''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | ]<br />(confused with native Gaelic Amhlaidh, Amhalghaidh) | |||

| | Aulay (Olaf) | |||

| | Ólaf | |||

| |- | |||

| | Goraidh | |||

| | Gorrie (Godfrey, Godfred), Orree (Isle of Man) | |||

| | Godfrið | |||

| |- | |||

| | Ìomhar | |||

| | Ivor | |||

| | Ívar (Ingvar) | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Ranald (Ronald, Randall, Reginald<ref>the option favoured by early Scottish sources writing in Latin</ref>) | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | Somhairle | |||

| | Sorley (or Samuel) | |||

| | Sumarliði (]) | |||

| |- | |||

| | Tormod | |||

| | Norman | |||

| | Þormóð | |||

| |- | |||

| | Torcuil | |||

| | Torquil | |||

| | Torkill, Þorketill | |||

| |} | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ], a sacred grove near Dublin targeted by ] in the year 1000 | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ]es | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Reflist|2}} | |||

| ==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

| * {{cite journal |last=Downham |first=Clare |date=2009 |title=Hiberno-Norwegians and Anglo-Danes |journal=Mediaeval Scandinavia |volume=19 |publisher=University of Aberdeen |issn=0076-5864}} | |||

| * McDonald, R.A., ''The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard in the Central Middle Ages, C.1000-1336''' (Scottish Historical Review Monograph), (Edinburgh, 1996) | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Haywood |first=John |title=The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings |date=1995 |publisher=Penguin |location=London |isbn=0140513280 |url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/penguinhistorica00john}} | |||

| * Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí, ''Early Medieval Ireland, AD 400-AD 1200'' (Longman History of Ireland Series), (Harlow, 1995) | |||

| * {{cite book |last=McDonald |first=R. Andrew |title=The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100 – c. 1336 |date=1997 |publisher=Tuckwell Press |location=East Linton |isbn=1898410852}} | |||

| * Oram, Richard, ''The Lordship of Galloway'', (Edinburgh, 2000) | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Ó Cróinín |first=Dáibhí |title=Early Medieval Ireland, 400–1200 |date=1995 |publisher=Longman |location=London |isbn=0582015669}} | |||

| * Fischer, David Hackett, ''Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America'', (New York, 1989) | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Oram |first=Richard |title=The Lordship of Galloway |date=2000 |publisher=John Donald |location=Edinburgh |isbn=0859765415}} | |||

| * Heywood, John, ''The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings'', (New York, 1995) | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Scholes |first=Ron |title=Yorkshire Dales |date=2000 |publisher=Landmark |location=Ashbourne, Derbyshire |isbn=1901522415}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| *{{Commons category-inline}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Scandinavian Scotland|state=autocollapse}} | |||

| {{Gaels}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Norse-Gaels}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] |

] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:57, 10 December 2024

People of mixed Gaelic and Norse heritageNorse settlement

Regions of Scotland, Ireland and Man settled by the Norse

Regions of Scotland, Ireland and Man settled by the Norse

The Norse–Gaels (Old Irish: Gall-Goídil; Irish: Gall-Ghaeil; Scottish Gaelic: Gall-Ghàidheil, 'foreigner-Gaels'; Old Norse: Gaddgeðlar) were a people of mixed Gaelic and Norse ancestry and culture. They emerged in the Viking Age, when Vikings who settled in Ireland and in Scotland became Gaelicised and intermarried with Gaels. The Norse–Gaels dominated much of the Irish Sea and Scottish Sea regions from the 9th to 12th centuries. They founded the Kingdom of the Isles (which included the Hebrides and the Isle of Man), the Kingdom of Dublin, the Lordship of Galloway (which is named after them), and briefly (939–944 AD) ruled the Kingdom of York. The most powerful Norse–Gaelic dynasty were the Uí Ímair or House of Ivar.

Over time, the Norse–Gaels became ever more Gaelicised and disappeared as a distinct group. However, they left a lasting influence, especially in the Isle of Man and Outer Hebrides, where most placenames are of Norse–Gaelic origin. Several Scottish clans have Norse–Gaelic roots, such as Clan MacDonald, Clan Gunn, Clan MacDougall and Clan MacLeod. The elite mercenary warriors known as the gallowglass (gallóglaigh) emerged from these Norse–Gaelic clans and became an important part of Irish warfare. The Viking longship also influenced the Gaelic birlinn and longa fada, which were used extensively until the 17th century. Norse–Gaelic surnames survive today and include Doyle, MacIvor, MacAskill, and [Mac]Cotter.

Name

The meaning of Gall-Goídil is 'Foreign Gaels' and although it can in theory mean any Gael of foreign origin, it was used of Gaels (i.e. Gaelic-speakers) with some kind of Norse identity. This term is subject to a large range of variations depending on chronological and geographical differences in the Gaelic language, e.g. Gall Gaidel, Gall Gaidhel, Gall Gaidheal, Gall Gaedil, Gall Gaedhil, Gall Gaedhel, Gall Goidel, Gall Ghaedheil, etc. The modern term in Irish is Gall-Ghaeil or Gall-Ghaedheil, while the Scottish Gaelic is Gall-Ghàidheil.

The Norse–Gaels often called themselves Ostmen or Austmen, meaning East-men, a name preserved in a corrupted form in the Dublin area known as Oxmantown which comes from Austmanna-tún (homestead of the Eastmen). In contrast, they called Gaels Vestmenn (West-men) (see Vestmannaeyjar and Vestmanna).

Other terms for the Norse–Gaels are Norse-Irish, Hiberno-Norse or Hiberno-Scandinavian for those in Ireland, and Norse-Scots or Scoto-Norse for those in Scotland.

History

The Norse–Gaels originated in Viking colonies of Ireland and Scotland, the descendants of intermarriage between Norse immigrants and the Gaels. As early as the 9th century, many colonists (except the Norse who settled in Cumbria) intermarried with native Gaels and adopted the Gaelic language as well as many Gaelic customs. Many left their original worship of Norse gods and converted to Christianity, and this contributed to the Gaelicisation.

Gaelicised Scandinavians dominated the region of the Irish Sea until the Norman era of the 12th century. They founded long-lasting kingdoms, such as those of Mann, Dublin, and Galloway, as well as taking control of the Norse colony at York.

Ireland

Main articles: History of Ireland (800–1169) and Early Scandinavian DublinThe Norse are first recorded in Ireland in 795 when they sacked Rathlin Island. This island is located off of the Northeast coast of Ireland and contains with it many gravesites with formal evidence of existence. Annals of Ulster states that the first raid on this island was known as the Loscad Rechrainne o geinntib, otherwise known as 'the burning of Rechru by heathens.' Sporadic raids then continued until 832, after which they began to build fortified settlements throughout the country. Norse raids continued throughout the 10th century, but resistance to them increased. The Norse established independent kingdoms in Dublin, Waterford, Wexford, Cork and Limerick. These kingdoms did not survive the subsequent Norman invasions, but the towns continued to grow and prosper.

The term Ostmen was used between the 12th and 14th centuries by the English in Ireland to refer to Norse–Gaelic people living in Ireland. Meaning literally "the men from the east" (i.e. Scandinavia), the term came from the Old Norse word austr or east. The Ostmen were regarded as a separate group from the English and Irish and were accorded privileges and rights to which the Irish were not entitled. They lived in distinct localities; in Dublin they lived outside the city walls on the north bank of the River Liffey in Ostmentown, a name which survives to this day in corrupted form as Oxmantown. It was once thought that their settlement had been established by Norse–Gaels who had been forced out of Dublin by the English but this is now known not to be the case. Other groups of Ostmen lived in Limerick and Waterford. Many were merchants or lived a partly rural lifestyle, pursuing fishing, craft-working and cattle raising. Their roles in Ireland's economy made them valuable subjects and the English Crown granted them special legal protections. These eventually fell out of use as the Ostmen assimilated into the English settler community throughout the 13th and 14th centuries.

Scotland

Main article: Scandinavian ScotlandThe Lords of the Isles, whose sway lasted until the 16th century, as well as many other Gaelic rulers of Scotland and Ireland, traced their descent from Norse–Gaelic settlements in northwest Scotland, concentrated mostly in the Hebrides.

Clan Gunn (Scottish Gaelic: Na Guinnich) is a Highland Scottish clan associated with lands in northeastern Scotland, including Caithness, Sutherland and, arguably, the Orkney Isles. Clan Gunn is one of the oldest Scottish Clans, being descended from the Norse Jarls of Orkney and the Pictish Mormaers of Caithness.

The Hebrides are to this day known in Scottish Gaelic as Innse Gall, 'the islands of foreigners'; the irony of this being that they are one of the last strongholds of Gaelic in Scotland.

The MacLachlan clan name means 'son of the Lakeland' believed to be a name for Norway. It has its Scottish clan home on eastern Loch Fyne under Strathlachlan forest. The name and variations thereof are common from this mid/southern Scottish area to Irish Donegal to the extreme west.

Iceland and the Faroes

It is recorded in the Landnámabók that there were papar or culdees (Gaelic monks) in Iceland before the Norse. This appears to tie in with comments of Dicuil and is given weight by recent archaeological discoveries. The settlement of Iceland and the Faroe Islands by the Norse included many Norse–Gael settlers as well as slaves and servants. They were called Vestmen (Western men), and the name is retained in Vestmanna in the Faroes and the Vestmannaeyjar off the Icelandic mainland.

A number of Icelandic personal names are of Gaelic origin, including Njáll, Brjánn, Kjartan and Kormákur (from Niall, Brian, Muircheartach and Cormac). Patreksfjörður, an Icelandic village, was named after Saint Patrick. A number of placenames named after the papar exist on Iceland and the Faroes.

According to some circumstantial evidence, Grímur Kamban, seen as the founder of the Norse Faroes, may have been a Norse Gael:

According to the Faereyinga Saga... the first settler in the Faroe Islands was a man named Grímur Kamban – Hann bygdi fyrstr Færeyar, it may have been the land taking of Grímur and his followers that caused the anchorites to leave... the nickname Kamban is probably Gaelic and one interpretation is that the word refers to some physical handicap (the first part of the name originating in the Old Gaelic camb crooked, as in Campbell Caimbeul Crooked-Mouth and Cameron Camshron Crooked Nose), another that it may point to his prowess as a sportsman (presumably of camóige / camaige hurley – where the initial syllable also comes from camb). Probably he came as a young man to the Faroe Islands by way of Viking Ireland, and local tradition has it that he settled at Funningur in Eysturoy.

Mythology

Heinrich Zimmer (1891) suggested that the Fianna Cycle of Irish mythology came from the heritage of the Norse–Gaels. He suggested the name of the heroic fianna was an Irish rendering of Old Norse fiandr "enemies", and argued that this became "brave enemies" > "brave warriors". He also noted that Finn's Thumb of Knowledge is similar to the Norse tale Fáfnismál. Linguist Ranko Matasović, author of the Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic, derives the name fíanna from reconstructed Proto-Celtic *wēnā (a troop), while linguist Kim McCone derives it from Proto-Celtic *wēnnā (wild ones).

Modern names and words

Even today, many surnames particularly connected with Gaeldom are of Old Norse origin, especially in the Hebrides and Isle of Man. Several Old Norse words also influenced modern Scots English and Scottish Gaelic, such as bairn (child) from the Norse barn (a word still used in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Iceland).

Surnames

| Gaelic | Anglicised form | "Son of-" |

|---|---|---|

| Mac Asgaill | MacAskill, McCaskill, Castell, Caistell | Áskell |

| Mac Amhlaibh (confused with native Gaelic Mac Amhlaidh, Mac Amhalghaidh) |

MacAulay, MacAuliffe, Cowley, Cawley, MacCamley, McCamley, Kewley | Óláf |

| Mac Corcadail | McCorquodale, Clan McCorquodale, Corkill, Corkhill, Corkell, McCorkindale, McCorkle, McQuorkell, McOrkil | Þorketill |

| Mac Coitir | Cotter, MacCotter, Cottier | Óttar |

| Mac DubhGhaill, Ó DubhGhaill, | Doyle, McDowell, MacDougal | Dubgall |

| Mag Fhionnain | Gannon | “the fair” (possibly in reference to someone with Norse ancestry) |

| Mac Ìomhair | MacIver, Clan MacIver, MacIvor, MacGyver, McKeever, etc. | Ívar |

| Mac Raghnall | Crellin, Crennel | Rögnvald |

| Mac Shitrig | MacKitrick, McKittrick | Sigtrygg |

| Mac Leòid | MacLeod | Ljótr |

Forenames

| Gaelic | Anglicised form | Norse equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Amhlaibh (confused with native Gaelic Amhlaidh, Amhalghaidh) |

Aulay (Olaf) | Ólaf |

| Goraidh | Gorrie (Godfrey, Godfred), Orree (Isle of Man) | Godfrið |

| Ìomhar | Ivor | Ívar (Ingvar) |

| Raghnall | Ranald (Ronald, Randall, Reginald) | Rögnvald |

| Somhairle | Sorley (or Samuel) | Sumarliði (Somerled) |

| Tormod | Norman | Þormóð |

| Torcuil | Torquil | Torkill, Þorketill |

See also

- Caill Tomair, a sacred grove near Dublin targeted by Brian Boru in the year 1000

- Scandinavian York

- Old English (Ireland)

- Clan Donald

- Earl of Orkney

- Faroe Islanders

- Gallowglasses

- Icelanders

- Kings of Dublin

- List of rulers of the Kingdom of the Isles

- Diocese of Sodor and Man

- Galley

- Lord of the Isles

- Lords of Galloway

- Papar

References

- Clare Downham. Hiberno-Norwegians and Anglo-Danes:anachronistic ethnicities and Viking-Age England. University of Aberdeen.

- "Key Primary Sources".

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons, 350–1064. Oxford University Press. p. 573. ISBN 9780198217312.

The Gallgaedil of 12th-century Galloway appear to have been predominantly Gaelic-speakers...remained a people separate from the Scots...Their separateness seems to have been established not by language but by their links with Man, Dublin, and the Innsi Gall, the Hebrides: they were part of a Hiberno-Norse Irish-Sea world

- "The vikings in Ireland". Professions. Viking Ship Museum. Roskilde, Denmark. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

Rathlin Island is the site of the first recorded Viking attack on Ireland in 795 AD. A number of Viking graves, some with magnificent grave goods, and a Hiberno-Norse coin hoard from the 1040's has been found here

- "The Annals of Ulster". celt.ucc.ie. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

- Valante, Mary (2008). Snyder, Christopher A. (ed.). Early People of Britain and Ireland: An Encyclopedia, Volume II. Greenwood Publishing. pp. 430–31. ISBN 9781846450297.

- Bannerman, J., The Lordship of the Isles, in Scottish Society in the Fifteenth Century, ed. J. M. Brown, 1977.

- Hunter, James (2000) Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh. Mainstream. ISBN 1840183764. p. 104

- Scott, Brian M. (2003). "Old Norse Forms of Early Irish Names". Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Schei, Liv Kjørsvik & Gunnie Moberg (2003) The Faroe Islands. Birlinn.

- ^ Zimmer, Heinrich (1891). Keltische Beiträge III, in: Zeitschrift für deutsches Alterthum und deutsche Litteratur (in German). Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. pp. 15ff.

- Scowcroft (1995), p. 154 harvp error: no target: CITEREFScowcroft1995 (help)

- Scott, Robert D. (1930), The thumb of knowledge in legends of Finn, Sigurd, and Taliesin, New York: Institute of French Studies

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). "wēnā". Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 412.

- McCone, Kim (2013). "The Celts: questions of nomenclature and identity", in Ireland and its Contacts. University of Lausanne. p.26

- "Surname Database: Gannon Last Name Origin". The Internet Surname Database. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- McKittrick Name Meaning and History Retrieved on 23 April 2008

- Mcleod Name Meaning and History Retrieved on 23 April 2008

- the option favoured by early Scottish sources writing in Latin

Bibliography

- Downham, Clare (2009). "Hiberno-Norwegians and Anglo-Danes". Mediaeval Scandinavia. 19. University of Aberdeen. ISSN 0076-5864.

- Haywood, John (1995). The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings. London: Penguin. ISBN 0140513280.

- McDonald, R. Andrew (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100 – c. 1336. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 1898410852.

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí (1995). Early Medieval Ireland, 400–1200. London: Longman. ISBN 0582015669.

- Oram, Richard (2000). The Lordship of Galloway. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 0859765415.

- Scholes, Ron (2000). Yorkshire Dales. Ashbourne, Derbyshire: Landmark. ISBN 1901522415.

External links

Media related to Norse-Gaels at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Norse-Gaels at Wikimedia Commons- Norse History of Clan Gunn of Scotland

| Scandinavian Scotland | |

|---|---|

| Rulers | |

| Notable women |

|

| Other notable men | |

| History | |

| Archaeology | |

| Artifacts and culture | |

| Althings | |

| Language | |

| Etymology | |

| Battles and treaties | |

| Associated clans and septs | |