| Revision as of 00:55, 23 July 2012 editJohnuniq (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators86,653 edits →There is NO negative resistance!: due to the power supply← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:27, 25 January 2024 edit undoQwerfjkl (bot) (talk | contribs)Bots, Mass message senders4,012,745 edits Implementing WP:PIQA (Task 26)Tag: Talk banner shell conversion | ||

| (286 intermediate revisions by 38 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{GA|20:43, 12 July 2015 (UTC)|topic=Computing and engineering|page=1|oldid=671157111}} | |||

| {{physics|class=c|importance=mid}} | |||

| {{WikiProject banner shell|class=GA| | |||

| {{WikiProject Physics|importance=mid}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{archive box| | {{archive box| | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| Line 5: | Line 8: | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *]| | |||

| age=360| | |||

| bot=lowercase sigmabot III}} | |||

| {{User:MiszaBot/config | |||

| |archiveheader = {{talkarchivenav|noredlinks=y}} | |||

| |maxarchivesize = 100K | |||

| |counter = 7 | |||

| |minthreadsleft = 2 | |||

| |algo = old(360d) | |||

| |archive = Talk:Negative resistance/Archive %(counter)d | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| == Opening paragraphs == | |||

| ==Archiving== | |||

| This page is already 84 kilobytes long. I suggest to archive (at least the first part of) it. ] (]) 14:11, 22 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :I have a better idea: Remove your graffiti ] (]) 20:45, 22 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :Agreed, now archived. C-F we do not need a detailed discussion of the circuit on the talk page. This is not the place to gain an understanding of the circuitry. Not in the article either except where it specifically relates to negative impedance. A general discussion of op-amp design principles belongs in another article. ] 21:36, 22 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ==Material removed== | |||

| Material not appropriate for talk pages moved to ]. ] 16:29, 27 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| == Templates == | |||

| What templates do we still need? I think they can largely be removed, any remaining problem text can be individually tagged. ] 22:47, 22 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :I removed them and added a cleanup tag. The article's getting better, but it still needs some work. ] (]) 23:37, 22 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::I don't think a general cleanup template is very helpful to editors coming to this article new in its current improved state. As I said above, I think we need to tag individual sections, or better still sentences, for improvement now. ] 16:43, 27 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| == I-V diagrams == | |||

| What is the purpose of the diagonal lines in the I-V diagram in the properties section? I cannot see what information they are adding. I am inclined to produce a cleaner, simpler diagram. Thoughts? Also, the tunnel diode I-V diagram is a bit innacurate according to my textbooks. I am inclined to redo that one as well, or at least re-legend the diagram to make it clear it is not realistic. ] 23:04, 22 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :], the diagonal green lines represent the moving IV curve of the varying input real current source; the vertical red lines represent the moving IV curve of the varying voltage source acting as a true negative resistor. My idea is to show how the true negative resistance IV curve is obtained. See also the text below: | |||

| :''The graphoanalytical interpretation of the negative resistance phenomenon is shown on the figure. It is supposed the negative resistor is driven by a real current source. When the input current varies, the voltage source representing the negative "resistor" changes its voltage. As a result, its IV curve moves and the crossing operating point slides over a new dynamic IV curve representing the negative resistance. It is not a real IV curve; it is an artificial, imaginary IV curve having a negative slope and passing through the origin of the coordinate system.'' ] (]) 23:19, 22 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :Good idea, I think it needs to be simplified, if not eliminated. The only possible use of it I can imagine is showing the boundary between positive and negative resistance. ] (]) 23:40, 22 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::Ok, I'll get on it next week, it's quite late now and I am going to be away on business most of the week. ] 00:09, 23 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::] said he would help out by converting scans from a Tunnel Diode manual I have. I agree the negative resistance IV diagram needs redoing, maybe with a derivation showing how a theoretical negative resistor delivers power to the load. There is an example problem in Desoer & Kuh, Basic Circuit Theory. I will do the analysis and see if I can create a diagram. This may be an aspect of negative resistors that is considered self-evident so may not be needed. ] (]) 00:24, 23 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| == Howland circuit == | |||

| The Howland voltage to current circuit is not a negative resistance device, or at least I cannot find a source that says it is, and putting in some trial component values produces positive results, circuit taken from; | |||

| *Paul Horowitz, Winfield Hill, ''The Art of Electronics'', page 182, Cambridge University Press, 1989 ISBN 0521370957. | |||

| This paper, | |||

| *Wang et al, "A Comprehensive Study on Current Source Circuits", ''IFMBE Proceedings'', '''Vol 17''', pp213-216, Published by Springer, 2007 ISBN 3540738401. | |||

| shows a Howland circuit in conjunction with a GIC to cancel the Howland circuits capacitance. If the Howland circuit were a NIC presumably it would be able to cancel it itself internally without the need for all this extra circuitry. On that basis I am going to remove Howland (and Deboo) as examples, at least pending some refs, but I might use the Wang paper as an example ref for load cancelling applications. ] 20:00, 27 February 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :The circuit on Fig. 4.13 (''The Art of Electronics'', page 182) represents the first version of ''Howland current source'' (''pump'') or, if we exclude the input voltage source and the load, a ''Howland voltage-to-current converter''. It consists of four ingredients: an input voltage source V<sub>IN</sub>, a negative impedance converter INIC (R1 = R4 = R3 = R and the op-amp), a "positive" resistor R2 = R and a load. The voltage source V<sub>IN</sub> and the INIC constitute a voltage source with negative internal resistance -R that is connected in parallel to the positive resistor R2 and the load. The role of the positive resistance R of the resistor R2 is to "neutralize" the negative internal resistance -R of the source. As a result, the final source has an infinite internal resistance and behaves as a constant current source. | |||

| :The second version of Howland current source (see Fig. 1 of ) consists of an input voltage source V<sub>IN</sub>, a positive resistor R, a load and a negative impedance converter INIC (R1 = R2 = R3 = R and the op-amp). The input voltage source and the resistor R constitute an imperfect current source with positive internal resistance R that is connected in parallel to the negative resistor INIC and the load. The role of the negative resistance -R is to neutralize the positive internal resistance R of the source. As a result, the load is driven again by a constant current source with infinite internal resistance. Well, let's include some algebra to be more cogent. | |||

| :The imperfect current source produces a current I<sub>L</sub> = (V<sub>IN</sub> - V<sub>L</sub>)/R = V<sub>IN</sub>/R - V<sub>L</sub>/R. As you can see, it differs from the ideal result I<sub>L</sub> = V<sub>IN</sub>/R by the term V<sub>L</sub>/R. It is more than obvious that we may compensate this error by adding the same term; then, I<sub>L</sub> = V<sub>IN</sub>/R - V<sub>L</sub>/R + V<sub>L</sub>/R = V<sub>IN</sub>/R. That means to inject an additional "helping" current I<sub>H</sub> = V<sub>L</sub>/R that is proportional to the load voltage. What is this circuit that can produce such a current I<sub>H</sub>? Of course, it is a voltage driven negative resistor with resistance -R; it is a negative impedance converter with current inversion (INIC) that is connected in parallel to the load. | |||

| :The generalized version is a combination between the two ones where the output current is proportional to the difference between two input voltages. As a conclusion, ''Howland voltage-to-current converter consists of two connected in parallel resistors with equivalent but opposite (positive and negative) resistances''; ''Howland voltage-to-current converter = INIC + resistor''. The "neutralization" between them produces an infinite resistance and, as a result, a constant current. The circuit is stable since the positive load resistance remains after the "neutralization" (another wisdom: in order to have stability, ''the negative resistance has to dominate over the positive resistance in a voltage-controlled negative resistor'' and ''the positive resistance has to dominate over the negative resistance in a current-controlled negative resistor''). | |||

| :Deboo integrator (see again Fig. 1 of ) is just a Howland voltage-to-current converter driving a capacitive load; ''Deboo integrator = Howland voltage-to-current converter + capacitor''. It has two advantages over the dual inverting integrator: it is a non-inverting circuit and the capacitor is grounded. But it has two disadvantages as well: it requires an op-amp with differential input and it has a bigger error depending on the resistor tolerances (here, the op-amp does not monitor the result of the compensation as it monitors the virtual ground at the inverting circuit). | |||

| :It is interesting that although there was nothing new in a Deboo integrator (actually, it was just a Howland pump driving a capacitor) Deboo was not aware of the Howland current source when he invented his integrator. I found out this fact in a ] between me and Deboo a year ago (Deboo was impressed by my comments to an about his famous circuit and emailed me). By the way, then I also exchanged interesting thoughts with Deboo about the unique feature of negative feedback to ] in circuits (to swap circuit inputs and outputs). For example, the ] is based on this idea. | |||

| :Today, I found an extremely interesting about the invention of the Howland circuit. Although it is nameless, it seems it is written by the very Howland. ] (]) 16:46, 1 March 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ==Negative resistance materials== | |||

| The article states that "Negative resistors are theoretical and do not exist as a discrete component". This is true for standard conductiving and semiconducting materials. However, some amorphous materials and ] do exibit negative resistance as an intrinsic characteristic. In such materials, conduction depends on localized states, hopping, etc. In fact, IIRC, Neville Mott won an Nobel prize for figuring out how such things work.] (]) 17:00, 12 June 2009 (UTC) | |||

| : Surely you're referring to the same type of negative resistance behavior seen in ]s, which is already given as an example in the introductory paragraph. Due to ], negative resistance can only exist in a small region of any discrete device's operating region, and that is especially true for naturally occurring materials. Does the ''i''–''v'' curve of the materials you're discussing exhibit negative resistance ''everywhere'', and, if it does, does it also intersect the origin (i.e., is it an ''active'' device?). Surely it intersects the origin (passive device), has a positive slope at the origin (positive resistance), and has negative resistance away from the origin (negative resistance region, like a tunnel diode), and then goes back to having positive resistance far from the origin (again, like a tunnel diode). If so, then the example at the end of the introductory paragraph should be expanded to include other materials... but certainly the intro paragraph shouldn't be changed to say that true "negative resistors" exist in nature. —''']''' (]) 17:11, 12 June 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :::Much conduction in amorphous semiconductors occurs by localized tunneling and phonon-assisted hopping between localized states. Really stretching the analogy-- a little like a whole bunch of really-small tunnel diodes. I.e., negative conductivity is a collective property of the material and not some engineered barrier effect. Similarly, such materials exibit "switching", even though they are not devices per se . Some ] show similar behavior.] (]) 01:50, 14 June 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::::Right -- that seems like what you'd expect, and the $i$--$v$ curves would still only exhibit negative resistance within a region. Hence, it seems most appropriate to change the claim about tunnel diodes at the end of the introductory paragraph to be more inclusive. —''']''' (]) 14:13, 14 June 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::Actually, the defining condition for breach of conservation of energy is, as the article says, ''if and only if'' the curve enters an even quadrant, not intersecting the origin. Having a negative slope ''and'' intersecting the origin are, together, sufficient, but not necesssary conditions, and either one alone is neither necessary nor sufficient. ] 17:29, 12 June 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::: That's ]. Counter examples are pathological in the context of this discussion. The question is how (and if) the article should change to accommodate facts about amorphous materials and conductive polymers. I feel that if anything needs to change, the final sentence of the introductory paragraph needs to be massaged to allow more than just special diodes. Otherwise, things are fine. —''']''' (]) 17:40, 12 June 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::::No need for the insults. ] 17:57, 12 June 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ==Fluorescent Bulb== | |||

| Shouldn't there be a mention of ballasts and their role they play in battling the negative resistance in fluorescent bulbs? | |||

| ] (]) 23:38, 11 August 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :Interesting... Would you like to discuss the topic here? ] (]) 11:36, 13 August 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::Not just Fluorescent, but other discharge lamps act as negative resistances, e.g. ] links here. ]s also exhibit negative resistance over part of their operating range, which was a design consideration in amplifier applications, and the basis of ] operation.--] (]) 16:40, 21 October 2011 (UTC) | |||

| == Resuming editing == | |||

| I have resumed editing as the page is poor. I will back up every my edit with a comprehensive summary. If you edit or remove my inserts, I will advance my arguments on the talk page and will invite you to discuss the topic. If you do not react, I will revert to the previous state. I will consider ungrounded and uncommented edits as vandalism and will revert as well. If it occurs again, I will notify administrators. ] (]) 17:39, 6 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :Good to see such respect for wiki policies on ] and ] -- ] (]) 17:47, 6 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :No-one is allowed their own definition of vandalism. ] is clear: " made in a deliberate attempt to compromise the integrity of Misplaced Pages". This definitely does not come under the changes you have listed above, though leaving edit summaries and discussing edits is strongly encouraged. —] <sup>]</sup> 18:23, 6 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::Sorry for my sharp tone above; as I can see, it is not intended for you. I would like only to warn that I will fight for truth and will not allow someone to play fast and loose with this page any more. Thank you for response. ] (]) 20:22, 6 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| == Resuming discussion == | |||

| ], you know that all I want is to discuss, to reveal the truth about these odd, strange, mystic and never explained circuits and components... And I have been trying (many times) to involve (well-meaning) wikipedians related to this page in such a creative discussion... And should I remember all the questions that I have put under discussion...and what you have (not) done to second me? Instead, you have allowed the truth about the unique phenomenon to be obliterated and the page to be disfigured... The result of this passive contemplation is this mutilated page where there is no structure, no basic ideas, no human explanations, no ... Well, let's resume discussion; I am ready to discuss again...and again...and again... What to begin with? Maybe, with definition: What negative impedance (resistance) is?] (]) 21:27, 6 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :No, you should begin with your sources that back up your statements. Reliable ones, not websites or Wikibooks you have written yourself. I have two immediate objections to your edits to the lede. (1) There is no such thing as a one-port negative resistance circuit. (2) Your use of "true" negative resistance to mean a circuit that produces an I-V curve intersecting the origin is at odds with everyone else, where the meaning is a one-port component that does this - which of course does not exist. Please provide reliable sources for these proposed additions. And please do not again post a detailed description of your theories and views, we can read them in the talk page archive if we really want to know. Instead post links to reliable sources that describe them, if there are any. ] 00:30, 7 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| === Definition: What negative resistance is? === | |||

| The first sentence says: "'''Negative resistance''' is a property of some ]s where an increase in the ] entering a port, results in a decreased ] across the same port." Reading this ubiquitous definition of negative resistance phenomenon I would like to say some remarks: | |||

| *It is obvious that elements exhibiting negative resistance property (tunnel diode, SCR, UJT) are 2-terminal (one-port) ones. Also, circuits exhibiting negative resistance property (VNIC and INIC op-amp circuits, SCR-, UJT- and Lambda simulated transistor circuits) are 2-terminal (one-port) devices. | |||

| *Current can not only ''enter'' the port; it can ''exit'' the port as well. So the sentence "current flows through the port" encompasses the both cases. | |||

| ] | |||

| *To say "...an increase in the current results in a decreased voltage across the NR..." is suitable only in the case of differential negative resistance elements and circuits; but it is confusing and misleading in the case of true negative resistance circuits. The problem is that when people meet words as "increase" and "decrease" applied to current and voltage they usually think of these electrical attributes ''as quantities with absolute values'', not ''as quantities with signs''. An example: imagine that a 12 volt battery is grounded with the positive terminal. If you say that the battery has decreased its voltage, e.g. by 2 volts, people will think of this battery as a 10 volt source not as a 14 volt one. Another example: imagine 1.5 A current flows in some circuit; then say that the current has decreased with .5 A and ask people what the current is. What will people answer? "2 A" or "1 A"? Be sure, no matter whether the current enters or exits the circuit they will answer "1 A" (even in the case of "negative" current) as ''people usually think in terms of current magnitudes''. So, thinking in this way (and especially if they do not see the picture on the right) and reading the ubiquitous definition, people will think of a true negative resistor as of a positive one! | |||

| The considerations above are more than obvious and are based on common sense. Don't you think they do not need to be backed up with any citations? Taking account of these remarks I suggest changing the first sentence as follows: | |||

| "'''Negative resistance''' is a property of some one-port ]s where an increase in the ] flowing through the circuit, results in a decreased ] across it." | |||

| and to add an explanatory disambiguating footnote: | |||

| "In this definition, current and voltage are considered as quantities with signs (not as quantities with absolute values)." | |||

| --] (]) 21:29, 7 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :Use of the term "one-port" for these circuits is dubious, as in reality there must be at least one other port which supplies the energy. Even for the tunnel diode, it only appears negative resistance as a small-signal equivalent circuit from which the dc bias has been discounted. So yes, I do think that sources are needed describing negative resistance circuits in this way before it can be used in the article. If there are none, we should not make up terminology. | |||

| ::I agree with you. Really, these circuits are typically but not obligatory one-port networks. They exhibit negative resistance at one port but they can have also another or more ports. Deboo integrator is a good example of such a configuration; power supply port not so much. Thanks, ] (]) 04:48, 11 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :I agree with your point about absolute and signed quantities. However, this can be dealt with by a simple addition, for instance, changing "decreased voltage" to "a decrease in the signed voltage". There is no need to make a major issue of this, certainly not in the lede paragraphs which should be kept simple, our readers are not idiots. ] 15:18, 8 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| ::], the most of our readers are not professionals. For example, Bob Pease never will write "negative resistance" in the Google window (although, I'm absolutely sure, he does not really know what negative resistance actually is). Instead, not as famous but curious people as pupils, students, technicians and hobbyists will want to know what it is and the introductory definition is the first explanation that they will meet. So, we have to consider very well the lede paragraph. | |||

| ::In the very beginning, we want to cover the two kinds of negative resistances (true and differential one) with one common definition. But the big problem is that they are completely different (a true negative resistor is a dynamic source while a differential negative resistor is a dynamic resistor). Maybe only the negative slope of their IV curves is the only relationship between them... ] (]) 19:32, 11 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| :::I don't agree with your comments C-F. There are established methods for analyzing and describing electronic circuits. You choose to devise your own. These novel musings don't belong here. I'm sure Bob Pease knows a lot more about negative resistance than you do and I suspect there is some history between you and Bob. I wish you would stop editing perfectly well written articles and reducing them to gibberish. Your command of the English language is marginal and your understanding of electronics is severely lacking.] (]) 05:44, 13 October 2009 (UTC) | |||

| === Negative differential resistance vs negative differential conductance === | |||

| I think this page is a bit confusing. The primary examples (tunnel and Gunn) diodes are poor examples of NDR: they don't even have a single-valued V(I) curve, and therefore are not monostable in a current bias configuration, so it's hard to argue that there is negative dV/dI (differential resistance) because dV/dI is multivalued: for a set current which has multivalued voltage, the voltage curve crosses at three places: twice with positive slope, and only once with negative. The sentence "Increasing the current causes an decrease in the voltage" is a misleading way to describe these N-shaped curves. | |||

| On the other hand, the current is a single-valued function of voltage, and tunnel diodes have obvious negative differential conductance (NDC). In a voltage-bias measurement, this is unambiguous: increasing the voltage causes a decrease in the current. | |||

| I realize that the phrase "Negative differential resistance" is used much more frequently in the literature of NDC, but it's worth pointing out at least somewhere on wikipedia that NDC is the correct term. ] (]) 03:44, 7 May 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :Your thoughts are very interesting and valuable, especially about the two dual terms (NDR and NDC). I completely second your opinion. I only regret that I have not taken note of your insertion earlier. ] (], ], ]) 14:58, 24 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| === S-shaped versus N-shaped negative resistors === | |||

| We should not simply say in the negative resistance definition that ''"an increase in the current entering a port results in a decreased voltage across the same port"'' since this definition is valid only for S-shaped negative resistors (e.g., a neon lamp, a negative impedance converter with voltage inversion VNIC, etc.) Only in this case, by changing the current through the resistor as an input quantity and measuring the voltage across it as an output quantity, the S-shaped negative resistor will operate in a linear mode (see ]). Its IV curve will be single-valued (see the section above) and we can observe a negative resistance region in the middle of the curve. If we try to drive an N-shaped negative resistor (e.g., a tunnel diode, a negative impedance converter with current inversion INIC, etc.) in this way, its IV curve will be multivalued (see again the section above). It will act as a bistable circuit with hysteresis (Schmitt trigger, latch); the voltage will "jump" and we will not observe any negative resistance region somewhere on its IV curve (see ]). Similarly, we should not drive an S-shaped negative resistor (e.g., a neon lamp, VNIC, etc.) by voltage if we want to see a negative resistance region on its IV curve. | |||

| So, the definition has to be more general. It should not say what is an input and what is an output (the causality). It has only to say that ''"current through and voltage across the same port change in opposite directions"'' when we vary the one of the quantities (the independent quantity) and measure the other (dependent quantity). In this way, it comprises both the S- and N-shaped negative resistors. | |||

| The two pictures represent the two kinds of negative resistors (an S- and an N-shaped one). So, the definitions in captions have to be more specific to show that for a neon lamp having S-shaped negative differential resistance the current is an input and for a tunnel diode having N-shaped negative differential resistance the voltage is an input. | |||

| So, the problem of the old article version was that the definition in the beginning of the lede has not matched the negative resistor in the figure. It has described the behavior of an S-shaped negative resistor (''"an increase in the current entering a port results in a decreased voltage across the same port"'') but the figure has represented an N-shaped negative resistor (a tunnel diode). BTW it is a very interesting and very indicative fact that an anonymous visitor but not a reputable wikipedian has noted this discrepancy... ] (], ], ]) 13:12, 24 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :The difference is only in the way the graphs are presented, the axes are interchanged, not in any real difference in the I-V relationship. ] 13:20, 24 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| ::You have not taken into consideration that the whole IV curve of a negative resistor consists of three regions - one middle part representing negative resistance and two end parts representing "positive" resistance. Although the middle (negative resistance) parts of the two kinds of negative resistors look the same, there is a very real difference between them: you cannot drive an S-shaped negative resistor by voltage and an N-shaped negative resistor by current if you want to observe negative resistance. ] (], ], ]) 14:10, 24 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| == Edits to the lead == | |||

| I've reverted , as I think it injects far too much wrongness to be worth editing. In particular: | |||

| * Negative differential resistance doesn't involve "energy addition" | |||

| * It introduces an unnecessary confusion by discussing negative conductance. Resistance and conductance don't imply causality (i.e. whether voltage causes current or vice versa) | |||

| * We would need a source for "circuits with negative resistance are current-driven" | |||

| * Even if this material were all correct, it is now more detailed than the article body, which is inappropriate for the lead. If we can make some of these additions sensible, then they should be moved to the relevant sections. | |||

| * Others have already expressed their opinions on the diagrams and captions | |||

| * Bearden is not in any way to be used as a reference! | |||

| ]<sup>(]|])</sup> 00:50, 26 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :You have preferred to restore the poor, misleading and even wrong lede (see the discussions above) instead to improve it (if there was such a need). In addition, as usual, you have not forgotten to make fun of my creation ("...it injects far too much wrongness to be worth editing...")... | |||

| :* A negative differential resistors does involve "energy addition" like any active (in the sense of amplification) element (a tube, a transistor, etc.) and this is the idea of any tunnel, Gunn, etc., diode amplifier. The only difference is that it is a 2-terminal active element. I recommend to you to read the section of the old negative differential resistance page (that you have redirected) to see how a NDC amplifier works. | |||

| :* Obviously, you have not carefully read the discussions above about NDR and NDC. Have you heard about SNDC and SNDR devices? Do you know that there is a Misplaced Pages ] about NDC? Negative conductance helps us to distinguish N-shaped from S-shaped negative resistors. There is causality in all these devices: we have to vary the current as an input quantity in an S-shaped negative resistor and the voltage in an N-shaped negative resistor. If we do the opposite, these devices will not act as negative resistors; they will act as bistable circuits with hysteresis (Schmitt triggers). | |||

| :* About "circuits with negative resistance are current-driven"... Of course, it is obvious that I have used here "negative resistance" in the narrow sense of the word (as a dual of "negative conductance"). How do I distinguish the two kinds of elements as there is no a common word for the both? | |||

| :* For now, I have inserted this essential data into the lede. How do I insert something sensible in the mess below? The article body needs reorganization, structuring... | |||

| :* Diagrams and captions illustrate exactly the lede; they are closely related to the lede. | |||

| :* Bearden's picture is very impressive and informative. It reveals the basic idea of negative resistance phenomenon; so, it is closely related to the lede. | |||

| :] (], ], ]) 07:17, 26 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| ::The material you propose is the wrong place (see ]) and makes a rather simple concept unnecessarily obtuse. As Oli Filth points out, Bearden should not be used as a source: see . ] (]) 09:04, 26 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :::Well, I see... but we have to start somehow. Don't you think it is better to have, as a starting point, a detailed but informative lede instead a short but misleading one? I intend to (re)structure the article body according to the classification described in the lede. Would you join this initiative? ] (], ], ]) 10:17, 26 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :::BTW negative resistance (impedance) phenomenon is not at all "simple concept" for people. Actually it is extremely simple but, for some reason or other, people do not (want to) realize it. If you not believe me, browse through the discussions above and through the old archived discussions... ] (], ], ]) 10:51, 26 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :: I will use my usual response: if you can find a reputable source that makes this distinction between negative resistance and negative conductance, then we can discuss that further. Also, if you can point out what aspects of the original lead are "misleading", then I will gladly discuss that too. ]<sup>(]|])</sup> 11:13, 26 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :::Have you read the discussions above? Or you just want to waste my time? Do not make me repeat obvious, simple and clear truths again and again and again... Well, we can use with the same success "S-shaped" and "N-shaped" instead "negative resistance" and "negative conductance". What do you think about this classification? ] (], ], ]) 12:53, 26 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :::: Is there a reputable source that makes this classification? Or at least, a source that uses this classification to come to the same conclusions as you? ]<sup>(]|])</sup> 11:02, 27 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :::::Let's first build the classification; then we can find sources that second it (if there is such a need). Here is my proposal. ] (], ], ]) 17:47, 28 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| '''NEGATIVE RESISTORS''' | |||

| : '''ABSOLUTE NEGATIVE RESISTORS''' (dynamic sources) | |||

| :: '''S-shaped absolute negative resistors''' (voltage inversion negative impedance converter VNIC) | |||

| ::: '''Current-driven S-shaped absolute negative resistors''' (VNIC in linear mode acting as a negative resistor) | |||

| ::: '''Voltage-driven S-shaped absolute negative resistors''' (VNIC in bistable mode acting as a latch) | |||

| :: '''N-shaped absolute negative resistors''' (current inversion negative impedance converter INIC) | |||

| ::: '''Voltage-driven N-shaped absolute negative resistors''' (INIC in linear mode acting as a negative resistor, Howland current source, Deboo integrator) | |||

| ::: '''Current-driven N-shaped absolute negative resistors''' (INIC in bistable mode acting as a latch) | |||

| : '''NEGATIVE DIFFERENTIAL RESISTORS''' (dynamic resistors) | |||

| :: '''S-shaped negative differential resistors''' (neon lamp, thyristor) | |||

| ::: '''Current-driven S-shaped negative differential resistors''' (neon lamp supplied through a ballast resistor) | |||

| ::: '''Voltage-driven S-shaped negative differential resistors''' (neon lamp relaxation generator) | |||

| :: '''N-shaped negative differential resistors''' (tunnel diode, Gunn diode, unijunction transistor) | |||

| ::: '''Current-driven N-shaped negative differential resistors''' (tunnel diode latch) | |||

| ::: '''Voltage-driven N-shaped negative differential resistors''' (tunnel diode amplifier) | |||

| I intend to base the article on this classification. ] (], ], ]) 17:50, 28 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| :I think Circuit-Dreamer has a valid point (which I apologise for having overlooked in a previous exchange above). Both cases have a negative slope of the I-V curve, but there is a difference in the way in which the device is driven/biased into the negative region. A tunnel diode must be voltage driven in order to guarantee that the bias point gets past the first I-V maximum. Neon signs etc must be a high-impedance source (ie current source) since the first peak is a peak in voltage, not in current. This does not, however, detract from the need to provide sources for what we write. Circuit dreamer is entirely wrong to state "Let's first build the classification; then we can find sources that second it". It is completely the other way round, find sources first and then write from the sources. I would say that even the terminology ''N-shaped'' and ''S-shaped'' needs sourcing. ] 20:17, 29 December 2010 (UTC) | |||

| == There is NO negative resistance, only "negative differential resistance" (NDR) == | |||

| I am surprised this article came this far with such a misleading and incorrect heading. People are entitled to their ideas and opinions but not to their facts as someone much wiser than me stated. Sometimes the enthusiasm to contribute here seems to go inversely propotional to the qualifications. There is no negative resistance in the universe and there is a very simple reason for it: It is against the laws of theromdynamics. Such a component would be generating energy out of thin air! One can only talk about negative differential resistance and in fact everything told in the article describes NDRs. It is the slope that may go negative, not the ratio of voltage to current. I am very interested in an example of an "absolute negative resistor". <span style="font-size: smaller;" class="autosigned">—Preceding ] comment added by ] (]) 19:44, 16 March 2011 (UTC)</span><!-- Template:UnsignedIP --> <!--Autosigned by SineBot--> | |||

| :Indeed, absolute negative resistors do not exist (for now) as elements. Some 1-port electronic circuits (including the power supply) act as absolute negative "resistors". They add energy to circuits in the same manner as the equivalent resistors subtract energy from circuits. For example, a series connected VNIC adds voltage that is proportional to the current through the port while a parallel connected INIC adds current that is proportional to the voltage across the port. For comparison, the series connected ohmic resistor with the same resistance would subtract voltage that is proportional to the current through it; the parallel connected equivalent resistor would subtract current that is proportional to the voltage across it. So, the true negative resistor is actually not a resistor; it is a ''dynamic source''. In contrast, the differential negative resistor is really a resistor; it is a ''dynamic resistor''. It acts as a 2-terminal active (regulating) element that controls the energy of an additional source (a power supply). The combination of the differential negative resistor and the source acts as a true negative resistor that adds energy to the circuit. ] (], ], ]) 22:12, 16 March 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::Would it be rude of me to suggest you keep your unique sense of sementics out of a public platform like this? Especially now that we established that there are no negative resistors, which is boldly the title of the article. A power supply is called a power supply and dynamic load is called a dynamic load, these are the terms and terminologies used by the people who actually practice the art. There is no component that is negative resisotr. I am sure there are many other forums where you can freely disseminate your unique interperatations and definitions but a general encylopedia is not a sutiable place for it. Looking at the discussions above, it seem plenty of folks have already tried to give you a hint, so it is a mystery why you would still insist on spreading false and incorrect information. <span style="font-size: smaller;" class="autosigned">—Preceding ] comment added by ] (]) 22:25, 16 March 2011 (UTC)</span><!-- Template:UnsignedIP --> <!--Autosigned by SineBot--> | |||

| :::There is nothing unique in these sentences; they just say the simple truth about the negative resistance. There is not a true negative resistor implemented as a 2-terminal component but there are electronic circuits (]s) '''acting''' as true negative resistors (note I have said "they act", not "they are"). ] (], ], ]) 23:20, 16 March 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :Hi 12! Thanks for your comments. I haven't had time to check this article lately, but I agree with your assessment of the situation: whereas circuitry with an inexhaustible power input can be rigged up to act as an "absolute" negative resistor would, in practice we would use other names for such things. Please edit the article or comment on specific items if you see something that should be fixed. ] (]) 01:42, 17 March 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::Here are some sources believing there are negative resistors and naming the corresponding circuits "negative resistors": | |||

| ::* - ''"If your resistive load is "R"Ω and you connect in parallel with it a '''negative resistor''' of "-R"Ω..."'' | |||

| ::* - ''"'''Negative resistors''' can be implemented by using amplifiers in positive-feedback configuration."'' | |||

| ::* | |||

| ::* - ''"A '''negative resistor''' would need to suck in heat and turn it to electrical energy."'' | |||

| ::* | |||

| ::] (], ], ]) 12:26, 12 April 2011 (UTC) | |||

| Ah, now there are claims of negative resistance again. Sources "believe"! Now we are in the sipiritual realm finally. Sounds like the Big Foot or Yeti. This farce needs to stop, it is degrading to Misplaced Pages. There is no negative resistance in the universe. It is non-physical, against all rules of thermodynamics and conservation. Negative differential resistance, which this poorly trained editor does not seem to understand, is a totally different phenomena. He is able to list the above outrageously titled articles from hobby magazines and trade journals, only because none are peer reviewed serious reference journals. Is it any wonder there is not a single IEEE reference? This is really shameful. <span style="font-size: smaller;" class="autosigned">—Preceding ] comment added by ] (]) 05:56, 7 May 2011 (UTC)</span><!-- Template:UnsignedIP --> <!--Autosigned by SineBot--> | |||

| :I think the reason for this confusion with terminology is because of misuse of the word differential. An emitter coupled pair is called a differential amplifier because it has inputs that drive a given output in opposite directions. The term you should be using instead of differential is incremental. Electronic circuits have a DC or steady-state behavior and a transient or incremental behavior. Incremental analysis of a circuit takes into account quickly changing behavior. For example there is no DC current flow through a capacitor. But incrementally capacitors do store and release charge. All the dynamic behavior we see in circuits is incremental phenomena. Negative resistance is an incremental effect. It would be correct to use the term incremental negative resistance but the term incremental is always implied when discussing behavior that is not steady-state (DC). ] (]) 14:20, 11 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::The problem is not if NDR is named ''differential'' or ''incremental''; both the words serve well to denote this phenomenon. The problem is that people (including you) do not understand what actually the ''differential'' and ''absolute'' negative resistances (resistors) are. They do not see the essential difference between them (that NDR is just a ''positive resistor'' while the true negative resistor is just a ''source''); as a result, they even do not suppose the absolute negative resistance can exist! Imagine they accept that there are sources but they cannot accept that there are negative resistors because they do not know (because of you and the likes of you) the simple truth that '''''negative resistors are nothing else than sources'''''! The only difference between them and the ordinary sources is that negative resistors are ''dynamic sources'' (whose voltage is proportional to the current through them or whose current is proportional to the voltage across them) while the ordinary sources are ''constant sources'' (constant voltage or constant current). | |||

| ::"Negative resistance is an incremental effect" is not true (if you mean true negative resistance). If you suppose its IV curve passes through the origin of the coordinate system (the usual case), then the negative resistance is not differential one; it is just a bare static resistance (exactly as ohmic resistance but with a negative slope). I.e., in this case, the differential and the static (chordal) resistance are the same. Only in the case when the IV curve does not pass through the origin (it is possible for true negative resistance as well!) we have two kinds of resistances - differential and static. ] (], ], ]) 17:02, 11 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :::Sure, but it's still unhelpful for this article. Is there a suitable source to provide guidance regarding how much coverage would be due for "absolute" negative resistance in this article (as opposed to NDR which is what people mean 99% of the time)? ] (]) 04:58, 12 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::::There are a lot of resources about negative impedance converters, Howland current pumps, Deboo integrators, load cancellers and maybe other circuits acting as true negative resistors (additional sources that add proportional voltage or current to the main source). ] (], ], ]) 05:38, 12 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::::: "...as true negative resistors"? There seems to be a mental block of some sorts involved, maybe an obsession. Neither belong to these pages. There is no such thing as a negative resistor. There is no such thing as a negative resistors or "acting like one". That would be called a source. This article is a candidate for deletion. Amazing it has come this far. ] (]) 03:37, 27 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::::::I marvel over how stupid someone has to be to not understand the so simple but genius idea - '''''connecting a varying source with voltage -2V<sub>R</sub> in series to a resistor R with voltage drop V<sub>R</sub> gives a total voltage -V<sub>R</sub>!''''' The combination of the two elements behaves as an element producing voltage proportional to the current (V<sub>R</sub> = -R.I) while the humble resistor R "produces" voltage drop proportional to the current (V<sub>R</sub> = R.I). | |||

| ::::::How do we name this element? Of course, "negative resistor"! But this is a figurative name since our creation is actually not a resistor; it is a source. But it is not an ordinary constant voltage source; it is a proportional to the current voltage source... | |||

| ::::::How do we use it? If we connect it in series to a "positive" resistor with resistance R1 > R, our negative resistor will "eat" only a part R from the whole R1; the result will be ''positive resistance'' R<sub>tot</sub> = R1 - R > 0. Then, if we connect it to a resistor with resistance R1 = R, the negative resistor will absorb it entirely and the result will be ''zero resistance'' R<sub>tot</sub> = R1 - R = 0. Finally, if we connect it to a resistor with resistance R1 < R, the result will be smaller total ''negative resistance'' R<sub>tot</sub> = R1 - R < 0... and you can only guess what will happen in this circuit... ] (], ], ]) 18:05, 27 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :::::::You are skirting too close to an ] in the above (yes, you didn't actually call anyone stupid, but your meaning is clear). I do not see anyone here who fails to understand the topic, and your explanations of why the term "negative resistance" is appropriate are not needed or relevant. What ''is'' needed, are reliable sources to justify text in the article. ] (]) 04:02, 28 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::::::::A source for a battery connected in series to a resistor? Here is ]. ] (], ], ]) 04:51, 28 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :::::::::I think you have just ruled out any chance of being taken seriously. By all means strike the above comment as a misplaced joke if you like, but taking it at face value, Misplaced Pages is not included at ], and the issue concerns using the ''name'' "negative resistance" to refer to what most people would call a source. ] (]) 05:20, 28 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| Sorry for joking... The problem is that this device is not simply a source; it is a very special kind of source; it is a '''proportional''' source. It can be a voltage source that changes its voltage proportionally to the current flowing through it or it can be also a current source that changes its current proportionally to the voltage across it. Due to this proportionality such a device can compensate a proportional voltage drop across or a proportional current through an equivalent resistor. Also, they are not independent sources; they are auxiliary sources connected in circuits supplied by main sources (they begin producing voltage/current when a current begins flowing through them or a voltage is applied across them). | |||

| So, we have somehow to draw attention to this proportionality by choosing an appropriate name for this so odd source. Of course, we may use some descriptive names as ''two-terminal current-controlled voltage source'' (''two-terminal voltage-controlled current source'') or ''one-port current-to-voltage converter'' (''one-port voltage-to-current converter''), etc. But if we note that it has an inverse to a resistor behavior, we can name it figuratively ''negative resistor''. And to distinguish it from NDR, we have to add some word as ''true'', ''absolute'', etc., before it. Then we can say that the group of ''negative resistors'' consists of two subgroups - ''true negative resistors'' and ''differential negative resistors'', and we have to structure the page according to this taxonomy. BTW all these names are already in use: | |||

| - 374,000 results | |||

| - 3,600 results<br> | |||

| - 5,200 results | |||

| - 25,500 results | |||

| ] (], ], ]) 16:07, 28 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| About 89,800,000 results for Black Magic ] (]) 04:48, 2 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :Unfortunately, my browser shows only 14,000,100<nowiki>:(</nowiki> ] (], ], ]) 07:14, 2 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :First, you should read , so you will understand that, well, Google counts are almost meaningless. | |||

| :Next, you should read some of the links. | |||

| :For example, when I searched for "negative resistance", the first hit was a Misplaced Pages page. Not a reliable source. | |||

| :The second hit was . Is it reliable? Probably not, but the more important point is that it says: "''For this reason, although it is conventional to call this effect ‘negative resistance’ it should more strictly be called Negative Differential Resistance or Negative Differential Conductance. ''" | |||

| :I'm not going to look further. Your own links are disproving your point.--<font style="font-family:Monotype Corsiva; font-size:15px;">]]</font> 21:19, 11 August 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :When you make a list of things to support your point, and the first two do not support your point, I'm going to stop reading the list, and put the burden on you. Which links support your point?--<font style="font-family:Monotype Corsiva; font-size:15px;">]]</font> 11:55, 12 August 2011 (UTC) | |||

| == After 5 years, it is time to reorganize the page... == | |||

| I am hopeful that after all the discussions about the nature of negative resistance that I started in and finished yesterday, there are no people that do not adopt the simple truths below about negative resistance phenomenon: | |||

| * There is nothing mystic in negative resistance phenomenon and in negative resistors; they are simple devices that can be explained by means of common sense and intuition. | |||

| * The general property of negative resistors is their ability to add (their own or else's) energy into circuits. | |||

| * ''True negative resistors'' add their own energy while ''differential negative resistors'' add else's (external) energy. | |||

| * True negative resistors exist as they are nothing else than sources that do not violate thermodynamics laws. | |||

| * These "sources" are not simple sources; they are ''proportional'' sources (voltage sources changing its voltage proportionally to the current flowing through them or current sources changing its current proportionally to the voltage across them). | |||

| * Due to this proportionality true negative resistors can compensate proportional voltage drops across or proportional currents through equivalent "positive" resistors. | |||

| * True negative resistors are auxiliary sources connected in circuits supplied by main sources; they begin producing voltage when the main source begins passing a current through them or they begin producing a current when the main source applies a voltage across them. | |||

| * Differential negative resistors are nonlinear positive resistors with extremely varying resistance in the negative resistance region. | |||

| * They are not used independently; they are used in a combination with a power source. | |||

| * This combination forms a true negative resistor... ''(to be continued)''... | |||

| IMO five years are enough to realize these simple truths and already it is time to tidy up the page. Spinningspark? ] (], ], ]) 10:24, 29 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :The dispute does not concern whether the ratio of voltage to current can ever be negative. Instead, the issue concerns the encyclopedic value of an exposition on a "true negative resistor": Does the topic satisfy ]? Do the sources satisfy ]? ] (]) 10:37, 29 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::I think I have said through these years a little something more than ''"whether the ratio of voltage to current can ever be negative"'':) As for the name, it is widely used (). As for the exposition on a "true negative resistor", I will work out it in the page about ] (the most popular circuits acting as true negative resistors). I have explained in details these circuits in three Wikibooks modules - ], ] and ]. ] (], ], ]) 10:54, 29 May 2011 (UTC) | |||

| == Merge from ] == | |||

| I've proposed that content from {{article|negative differential conductivity}} be merged into this article, and that article redirected here. Please indicate whether you think this is a good or bad idea below. | |||

| By all means add a short rationale; that said, extended discussion should probably go in its own section (I've added one below). Litmus test is, if you're responding to someone else's comment, putting it in the comments section probably works best. --] (]) 06:21, 16 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ===Brief statements=== | |||

| * '''Support''' merge into ]. The "negative resistance" article has a far clearer explanation of the phenomenon, and I usually see it described as "negative resistance" or "negative impedance" in (US) academic publications, so keeping it here seems to match ] best. --] (]) 06:21, 16 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| * '''Support''' Per CT. The main point is that it is negative resistance, whether this is expresses as (differential) conductance, impedance, or whatever, is somewhat secondary.]] 08:09, 16 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| * '''Support''' ] (]) 09:25, 16 June 2011 (UTC). | |||

| * '''Support''' Resistance is the more common; same idea. ] (]) 13:55, 16 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| *'''Oppose''' Ths whole articles is in desperate need of deletion. It basically claims Earth is flat. No need to make it more complicted and spoil other articles. <span style="font-size: smaller;" class="autosigned">— Preceding ] comment added by ] (]) 16:32, 17 June 2011 (UTC)</span><!-- Template:UnsignedIP --> <!--Autosigned by SineBot--> | |||

| *'''Support''' Absolutely. As ]] says, "'']''" is really just a more technical term for negative resistance. --<font color="blue">]</font><sup>''<small>]</small>''</sup> 21:46, 7 March 2012 (UTC) | |||

| ===Discussion=== | |||

| '''Comment''' - With regards to "negative resistance", "differential resistance", etc, I've usually seen this type of measurement referred to as "] resistance". When performing AC analysis (at least up here), it's customary to split signals into a ] DC component (which can assume any bias value), and a separate AC component that is assumed to be small enough for linear approximations of circuit component behavior to hold. Per this article, that can sometimes result in a negative small signal resistance. In papers that give ac analyses, the words "small signal" are usually omitted (mentioned once at the beginning of the analysis to make context clear). | |||

| That said, it's possible this is a regional thing. The papers I read are generally from ] journals and other North American sources. --] (]) 08:36, 16 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :Not true. One will never find an article on "negative resistance" in a proper journal, since it does not exist. Words have been taken out of content. In fact, most of the references are not from respectable peer-reviewed magazines, where writers are careful about their choice of words. I seriously doubt if the above editor actually follows any IEEE journals, it is not reflected in references or in discussion.] (]) 21:09, 18 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::Rather than address the assumptions you're making, I'll just point you over to , where "negative resistance" gets upwards of 1500 hits (1000 journal publications, 550 conference publications). Enjoy. --] (]) 00:23, 19 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| Negative resistance ''could'' be distinguished from negative resistivity/conductivity in the same way that we distinguish ] from ] and give them separate articles. Resistivity is a property of materials whilst resistance is a property of devices. However, ] does not really discuss materials, it discusses devices so does not really work as its own article. ''']]''' 16:49, 16 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| The fact there is a graph that shows the IV curve going straight through the origin continuing into the third quadrant should be grounds for deletion. Various concepts, suchs as NDR, NR circuits, and negative resistance and negativity all jumbled here by an unqualified editor.] (]) 21:13, 18 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ] | |||

| :I can't see any "IV curve going straight through the origin continuing into the third quadrant" in this page. ] (], ], ]) 11:52, 23 June 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :: How ingenius! Becasue it has been REMOVED! After a long time defending the integrity of the article and claiming factuality, the un=physical plot has been finally removed. A very small step in the right direction! ] (]) 15:42, 2 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| The opening paragraphs of this article seem a little confusing to me. It says that as voltage is increased the current decreases, but that seems a little backward. How do you increase voltage when resistance is falling? That seems like trying to increase the pressure of a waterfall by spraying a garden hose into it. As I understand it (and please correct me if I'm wrong) as current is increased, both the voltage and resistance decrease. | |||

| :::If you mean the picture on the right, it illustrates the operation of an S-shaped true negative resistor (Fig. 7b) in the middle part of its IV curve (in blue). In this region, the IV curve has a negative slope and passes through the origin of the coordinate system. The green line represents the IV curve of the input real current source and the red line represents the IV curve of the internal dynamic voltage source. The multitude of lines gives an impression of line movement (animation). When the input current varies, its green IV curve moves vertically remaining parallel to itself. The internal voltage source varies its voltage and moves its red IV curve horizontally in the according direction so that the intersection (operating) point pictures the blue negative resistance IV curve. As you can see, the negative resistor IV curve lies completely in 2nd and 4th quadrants. The other curves cross the 3th quadrant but they are "positive". I have replaced this "ideal" IV curve with the more practical N- and S-shaped curves of INIC and VNIC. ] (], ], ]) 14:19, 9 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| When most people talk about voltage, they're talking about open-circuit voltage (OCV), which is when voltage is at its highest. When the circuit is closed, there is a voltage drop as amperage increases. Resistance is what limits this voltage drop and, per Ohm's law, the accompanying increase in current. In a normal resistor, heat is generated which actually increases its resistance. A hydraulic analogy is found in a simple water faucet. When the faucet is closed, pressure in the line is highest. When fully open, the pressure is lowest and flow is highest. Opening the faucet a little bit increases its resistance to flow, so the pressure drop is smaller and so is the flow. (Keep in mind that "open" and "closed" mean exactly the opposite with electricity as they do in hydraulics.) | |||

| == About the last major edits == | |||

| For negative resistance, when the circuit is closed, the voltage drops accordingly, and the amperage increases. The difference is that as the plasma heats up, the resistance begins dropping along with the voltage, thus the current runs away like a freight train. (A hydraulic analogy is that as soon as you crack the faucet, it blows off and water flows just as fast as the pipe will allow, and pressure drops to almost nothing.) ] (]) 20:07, 30 March 2017 (UTC) | |||

| I have reconstructed the article according to the dicussions. I have explained what negative resistance actually is, how it is implemented in two versions and how negative resistors operate. I have structured the article according to the idea that there are two kinds of negative resistance circuits (differential and true) that are closely related but yet they are quite different. | |||

| :This is a pretty complicated subject, and hydraulic analogies are not going to get you very far. I don't think there is any effect in hydraulics which is analogous to negative resistance (a ''decrease'' in flow rate through a hydraulic system with an ''increase'' in the pressure across it?). I'll try to answer your questions | |||

| I have removed the top picture about resonant tunneling diode as it is too detailed for this place. I have also removed some manifestly promotional external links presenting specific circuit solutions. I have tried to salvage all useful insertions from the previous version. ] (], ], ]) 10:09, 2 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :*"''When the circuit is closed, there is a voltage drop as amperage increases.''" This is caused by ], a positive resistance. Any source of power has internal resistance resulting in a drop below the open circuit voltage when current is drawn. | |||

| :*"''As I understand it (and please correct me if I'm wrong) as current is increased, both the voltage and resistance decrease.''" You're right. Keep in mind there are two kinds of resistance; the "absolute" or "static" resistance, '''V/I''' which is what you are talking about, and the differential resistance '''ΔV/ΔI'''. Anything can happen to the differential resistance; it can increase, stay the same, or decrease. | |||

| ] | |||

| :The fluorescent tube is not the best example to introduce negative resistance, because due to ] the current through it doesn't change continuously as a function of voltage, but in "jumps". I just added the picture because it is the most common device with negative resistance readers will be familiar with. | |||

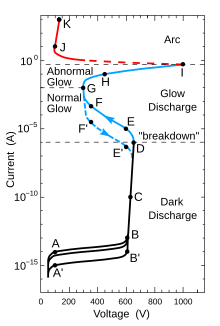

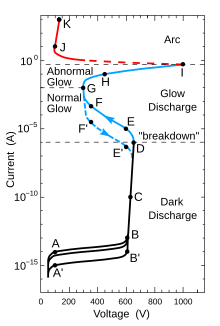

| :A ] like a fluorescent light has a type of negative resistance called "current controlled" or "S type" (see ]). The graph ''(right)'' shows its current-voltage curve; the voltage across the tube at any given current. The negative resistance region is between D and G. When a voltage source (the power line) is connected across it that is greater than its ] D (about 700 V on this graph), this causes an effect called ]. The current becomes unstable and increases exponentially, only limited by the external circuit. This is caused by a "chain reaction" of ionization in the tube. You could say the tube's absolute resistance "drops", but keep in mind the tube doesn't have a "resistance" at all currents because the current changes in jumps. In this regime the tube cannot operate stably at points on the curve where the differential resistance is negative (sloping down to the right, such as between E and F or I and J)(see ]), the current can only be stable at points of positive differential resistance (A, B, C, D, G, H, J, K). | |||

| :I think you should self-revert this series of edits and request that you do so right away. | |||

| :*You have once again inserted whiteboard drawings which have been discussed before. Previous discussions resulted in their removal for their unprofessional look with freehand sketches and stick-men figures. | |||

| :*Much of the prose is unfathomable, making a simple idea completely obtuse: an example is the opening sentence of the background "Negative resistance can be created in some limited region of resistor IV curve by vigorously changing the resistance or the magnitude of additional voltage." | |||

| :*While I agree that there are two different things being discussed on this page and they need to be clearly separated, the current article really fails completely in the clarity department. | |||

| :*The use of the terms "true negative resistance" and "absolute negative resistance" have been opposed on this talk page by about every editor that has commented on the subject and yet they have been inserted in the article "according to discussions" as if everyone now agreed. Just because you have written your views on this page does not mean else everyone agrees. | |||

| :*"True negative resistor" is even more unacceptable - there is no such component. | |||

| :I do agree with your removal of the top picture, that really was not very helpful to the reader. I also agree on the need to distinguish ''negative differential resistance'' from ''negative resistance circuits'' but it needs to be done with standard terminology with reference to good sources, not our own OR. ''']]''' 13:34, 2 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :If the external circuit has sufficient resistance or other current-limiting device (such as a ]) the current can stabilize at a positive resistance point higher on the curve (around G and H). At this point the current will be higher but the voltage across the tube will be lower, reduced by the voltage drop across the current limiter, so the tube's absolute resistance is lower. The tube will have a ] and emit light. This is what happens in a working fluorescent light. If the external circuit has insufficient resistance, the current will continue increasing to the regions J and K where the discharge becomes an ] which releases a great deal of heat, causing failure of the tube. --]<sup>]</sup> 10:29, 31 March 2017 (UTC) | |||

| ::It all seems like rather desperate attempts at saving a totally irrelvant article that did not belong here (or anywhere) in the first place. The fact that Misplaced Pages is not exactly a scinetific or engineering reference source or visitied by scientists (here is a good example why) makes these oddities survive here this long I think. | |||

| ::*The name of the article is still the biggest problem with it, and not the only one. It is simply wrong and misleading. | |||

| ::*There is confusuion about "negative resistance", negative differential resistance" and "negative resistance circuits". | |||

| ::*The editor who seems to have been emotionally vested into this creation does not seem to seperate these concepts and uses them interchageably | |||

| ::*Some of the information belongs to a NDR article. | |||

| ::*Some of the rest belong to a "Negative Resistance Circuits" article, though not sure if there is such an obvious need in Wkipedia for it. | |||

| ::*Whatever remains should then be expunged from here and the travesty should end. | |||

| ::] (]) 15:56, 2 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::Ok, I see what you mean. I was under the impression that a fluorescent lamp operates in the arc regime, but could be wrong. None of the glow discharge lamps I've built ever needed a ballast to control the current; they could be connected directly to the transformer or line voltage, like a neon sign. The ballast seems to be necessary only when I crossed into the arc regime, where the current runs away on its own. (The exception of course is a flashtube.) Once this happens, no increase in voltage is going to extinguish the arc (which is what I was getting from the opening paragraphs.) ] (]) 17:17, 31 March 2017 (UTC) | |||

| ::I support the statement by SpinningSpark: this article has gone off the rails. There is bad writing ("dynamizing the resistance or voltage") and unhelpful OR (NDR and ANR—yes we understand, but the presentation gives a false picture of the real world). ] (]) 01:57, 3 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :::You make neon lights? Cool. I know the term "arc light" is used for some gas discharge tubes, but I'm pretty sure fluorescent lamps and neon lights operate in the "glow discharge" regime. I don't know exactly how the current is limited in a neon tube light. I believe I read somewhere that the neon sign transformer is designed with large ] so it acts as a ballast, limiting the current so it doesn't run away? --]<sup>]</sup> 18:37, 31 March 2017 (UTC) | |||

| ::: '''support revert'''. I am not troubled by the article title because it is a ]. I agree with SpinningSpark's comments. I am not saying the previous version is good; I have trouble with both versions. Although CircuitDreamer is well-meaning, he has gone too far, continues to add his original research, and does not cite to reasonable secondary sources. If I recall correctly, he has been cautioned about those problems in the past. I can overlook some of his awkward English, but not his lack of clarity. ] (]) 03:20, 3 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ] | |||

| :::: '''support revert'''. Negative resistance is a commonly accepted term. This was all discussed <i>ad naseum</i> a couple of years ago. Multiple articles on the same subject with different names are not needed. Negative impedance, negative differential resistance, negative differential conductance... have I missed one? Oh yes- negative differential immittance. Whatever happened with the Misplaced Pages Administrator's noticeboard/incident where circuit-dreamer was asked to refrain from this very same behavior? Can SpinningSpark explain why circuit-dreamer is able to do whatever he pleases? ] (]) 04:10, 3 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::::I've made some simple ones in my younger days. Mostly I was trying to figure out how to make flashtubes that wouldn't explode or lose pressure over time. (Made well over 400, of which only four survive to this day. It really wasn't until I began talking to experts, like Harold Edgerton or Don Klipstein, and even had one owner of a company give me a bunch that he was going to throw away, that I finally succeeded in making my first operational laser.) I've got a nice, big neon-sign transformer that's perfect for bombarding (removing oxygen that adheres to the glass) small flashtubes and arc lamps. The transformers needed to bombard a full-size neon sign are monstrous. (Typically about the size of a 55 gallon drum. Way out of my price range.) | |||

| ::::Nearly every book I've seen on fluorescents seem to call the discharge an arc. Of course, that doesn't mean they are always correct, so now I'm curious to dig deeper. Neon signs definitely operate as glow discharges, though. The small neons (like you often see in an extension cord to indicate it's plugged in) are connected directly to the line. ] (]) 19:06, 31 March 2017 (UTC) | |||

| ::Spinningspark, I will answer first to you since you, as an administrator, bear the full responsibility for the of this article. As always, your instant response to my edits predestines what will happen after... | |||

| ::*You have given me an opportunity to self-revert... but to what? To the previous where there is no structure, no hierarchy, no classification, no one basic idea, no reasonable explanations of basic implementations and circuit operation, no one picture illustrating the operation...? | |||

| ::*You have said that my "whiteboard drawings have unprofessional look with freehand sketches and stick-men figures". Imagine you have said so much about the form and nothing about the contents! I would like to ask you to answer honestly and responsibly, accordingly to your position in Misplaced Pages, to my simple questions: Have you ever seen such simple, clear and self-explaining illustrations revealing the basic idea (''dynamic resistor'' and ''dynamic source'') behind negative resistance? Pictures that show the motion in operation thus revealing how the negative resistance is created in the middle part of the IV curve? If yes, please give a permission from these sources and place their instead my "whiteboard" pictures; if no, help me to improve them. | |||

| ::*There is no problem with "unfathomable sentences" if only there is a good faith. I am ready to comment them, to explain what I mean and (all together) to improve them. Let's try to do it just now. | |||

| :::In the very beginning, I have tried to show in only one definition the general idea behind the two possible kinds of negative resistances (differential and true): "Negative resistance can be created in some limited region of resistor IV curve by vigorously changing the resistance or the magnitude of additional voltage." Here is what I mean. | |||

| :::I would like to say that negative resistance is created on the base of (by modifying) some positive resistance. Negative resistance cannot exist independently. It cannot exist in the whole operating range; it can exist only in a limited region of the range. Accordingly, negative resistance cannot occupy the whole IV curve; we can create a negative slope (fold up the curve) only in some limited middle part of the whole IV curve of a positive resistor. In the end parts, the resistance is positive; thus the odd "S" or "N" shape. | |||

| :::For this purpose, we have somehow to change the monotonous motion of the operating point (that draws the IV curve) when the input quantity (voltage or current) changes within the negative resistance region; we have to revert its direction. The trick is simple but clever: in the one-variable function I<sub>OUT</sub> = V<sub>IN</sub>/R (Ohm's law) we begin changing another (second) variable simultaneously with the first one. For example, we can change the very resistance R or we can change the voltage of an additional voltage source connected in series with the resistor. Thus, in this region, we actually have a function of two variables (I<sub>OUT</sub> = V<sub>IN</sub>/R<sub>IN</sub> or I<sub>OUT</sub> = (V<sub>IN1</sub> + V<sub>IN2</sub>)/R) but we consider it as a function of one variable (we see only the one variable - the input voltage). Thus, we have artificially changed the resistance in this region; we have made ''dynamic'' resistance. As a result, the curve changes its slope up to negative but only within the borders in the negative resistance region where we have what (resistance) to change. After the end of the region, the reserve of high resistance (S-shaped curve) or high conductance (N-shaped curve) is depleted and the resistance reaches its minimum (S-shaped curve) or maximum (N-shaped curve). The magic of negative resistance ceases and the ordinary positive resistance establishes in the final part of the IV curve (the negative resistor is saturated). Similar considerations can be written for the first part with positive resistance where the initial resistance is maximum (S-shaped curve) or minimum (N-shaped curve) and the negative resistor is saturated. These end parts of saturation can be seen very well in the IV curves of the op-amp negative impedance converters - INIC (Fig. 5a) and VNIC (Fig. 5b). | |||

| :::So, I have tried to put all the wisdom above in one sentence. | |||

| ::*"The use of the terms "true negative resistance" and "absolute negative resistance" have been opposed..." Please, suggest the right terms then to denote the existing phenomenon. I have tried everything to solve the problem: I have explained that actually there is no true negative resistance exactly as there are no true sources; I have explained what a true negative resistor is (a circuit with power supply); then, I have put "true" in quotes to show that this is a metaphoric name... But what have you done to solve the problem? You continue repeating, ''"True negative resistor" is even more unacceptable - there is no such component."'' There is no a component but there is a circuit that can be figuratively named "true negative resistor". See this funny of Professor Horowitz (in contrast to wikipedians, he has a sense of humor:) where he has hidden an op-amp NIC supplied by two 9 V batteries in a cardboard box with a label of 10 kΩ to mimic a component (a resistor). | |||

| ::] (], ], ]) 18:20, 3 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :::Please put this on your personal website as it is not suitable for an encyclopedic article. In fact, it is complete nonsense, and you are failing to acknowledge that many of the editors here are totally comfortable with negative numbers, and we understand that a black box can be rigged up to do unusual things. This article will end up being based on traditional and reliable sources, without confusing readers. ] (]) 02:36, 4 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| :::::I talked to a friend of mine who knows more about this than I, and he turned me on to source, which gives wonderfully detailed explanations of the various discharges. (Cleared up a few of my misconceptions.) Fluorescent tubes are definitely low-pressure arc lamps, because they require the thermionic emission of electrons from the cathode to support their operation. The exception to this are cold-cathode fluorescents (often used in computer backlighting), which are are basically fluorescent tubes operated like a neon light. Neon signs also fall under the category of cold-cathode lamps. When a fluorescent is perpetually lit, the main process of wear becomes adsorption of the mercury onto the glass, which eventually reduces its pressure enough to move it into the glow-discharge regime, causing it to dim and eventually form visible Faraday cones that move from the ends toward the center. (This may also bee seen during start-up, especially in 8 foot T12s, before the tube heats up and increases in pressure as the mercury vaporizes.) ] (]) 00:28, 4 April 2017 (UTC) | |||

| It seems to me we have a run away editor here, devoid of simple common sense and ability to heed to good advice. All of the above plus whats in the logs way before my encounter with this oddity, should have been enough reason to hit the re-start button. I think Misplaced Pages could have been served better by those who are given the authority and responsibility to prevent these monstrosities. ] (]) 03:49, 4 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::::::Say ], I'm sorry, when I wrote the above comments I forgot that you have a great deal of experience with this stuff in building lasers (guess it was a ]). Most of what I wrote is probably not news to you. You met Harold Edgerton? Wow. | |||

| ::::"It is complete nonsense..." Can you cite here only one nonsense assertion and explain what is nonsense? If you can't, please apologize for the insult. ] (], ], ]) 04:31, 4 July 2011 (UTC) | |||

| ::::::Yes, that gas discharge page by Calvert is absolutely great, I ran across it before, that's where I learned what little I know about the subject. It would be good to put some of that stuff into the ] article, which in my opinion needs a rewrite. BTW, editor ] has the most expertise in this area of anyone I know, and he would be the person to ask questions of. --]<sup>]</sup> 01:55, 4 April 2017 (UTC) | |||

| {{outdent}} | |||