| Revision as of 07:15, 29 April 2006 view sourceSuperDeng (talk | contribs)1,937 edits rv my own change beacuse it did something to the page← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:37, 26 December 2024 view source Remsense (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Template editors59,292 edits Undid revision 1265419168 by Stepheneroberts (talk) correct beforeTags: Undo Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit App undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1939–1945 global conflict}} | |||

| <!--This is a very long article. If you have more information regarding World War II, please consider adding it to one of the articles referenced by this article that deal with specific areas of World War II rather than to this article. -->{{Infobox Military Conflict | |||

| | |

{{Redirect-several|WWII|The Second World War|World War II}} | ||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| |partof= | |||

| {{Pp|small=yes}} | |||

| |image=] | |||

| {{Use British English|date=December 2019}} | |||

| |caption='''From top counterclockwise''': ] landing on ] beaches on ], the 1936 ], the ] ], ] soldiers raising the ] over the ] in ], the gate of a ] at ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2024}} | |||

| |date=1939–1945 | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |place=], ], ], ], ] and ] | |||

| | conflict = World War II | |||

| |result=Allied victory | |||

| | image = {{multiple image|border=infobox|perrow=2/2/2|total_width=300 | |||

| |combatant1=''']''':<br>],<br>],<br>]/],<br>],<br>],<br>],<br>] | |||

| | image1=Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-646-5188-17, Flugzeuge Junkers Ju 87.jpg | |||

| |combatant2=''']''':<br>],<br>],<br>],<br>] | |||

| | alt1= | |||

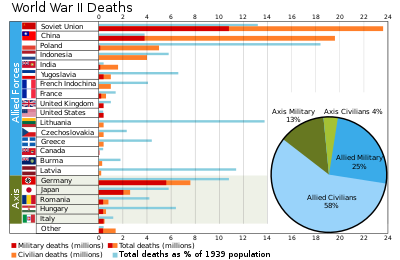

| |casualties1='''Military dead''': 17 million<br>'''Civilian dead''': 33 million<br>'''Total dead''': 50 million | |||

| | image2=Matilda tanks on the move outside the perimeter of Tobruk, Libya, 18 November 1941. E6600.jpg | |||

| |casualties2='''Military dead''': 8 million<br>'''Civilian dead''': 4 million<br>'''Total dead''': 12 million | |||

| | alt2= | |||

| | image3=Nagasakibomb.jpg | |||

| | alt3=in the | |||

| | image4=Bundesarchiv Bild 183-R76619, Russland, Kesselschlacht Stalingrad.jpg | |||

| | alt4= | |||

| | image5=Raising a flag over the Reichstag - Restoration.jpg | |||

| | alt5= | |||

| | image6=USS Pennsylvania moving into Lingayen Gulf.jpg | |||

| | alt6=}}From top to bottom, left to right: {{flatlist| | |||

| * German ] dive bombers on the ], 1943 | |||

| * British ] tanks during the ], 1941 | |||

| * U.S. ] in Japan, 1945 | |||

| * Soviet troops at the ], 1943 | |||

| * Soviet soldier ] over the ] after the ], 1945 | |||

| * U.S. warships in ] in the ], 1945 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | date = 1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945{{efn|While ] have been proposed as the date on which World War II began or ended, this is the period most frequently cited.}} <br /> ({{Age in years and days|1 September 1939|2 September 1945}}) | |||

| '''World War II''', also '''WWII''', or '''The Second World War''', was a global military conflict that took place between 1939 and 1945. It was the largest and deadliest war in history. | |||

| | place = Major ]: {{flatlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | result = {{ubl|] victory (see also ])}}<!--This fixes label and data text alignment by locking it in place--> | |||

| | combatants_header = ] | |||

| | combatant1 = ]<!--NOTE: The consensus of a discussion which concluded in November 2014 at ] was to only list the 'Allies' and 'Axis' as combatants. PLEASE do not make any changes without first obtaining consensus for the change on the article's talk page. --> | |||

| | combatant2 = ]<!--NOTE: The consensus of a discussion which concluded in November 2014 at ] was to only list the 'Allies' and 'Axis' as combatants. PLEASE do not make any changes without first obtaining consensus for the change on the article's talk page. --> | |||

| | commander1 = ''']:'''{{plainlist| | |||

| * {{flagicon|Soviet Union|1936|size=22px}} ] <!--NOTE: Please do not alter the order of the commanders in this info box without consensus. Thank you.--> | |||

| * {{flagicon|United States|1912|size=22px}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|United Kingdom|size=22px}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Republic of China (1912–1949)|size=22px}} ]}} | |||

| | commander2 = ''']:'''{{plainlist| | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany|size=22px}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Empire of Japan|size=22px}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Fascist Italy (1922–1943)|size=22px}} ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | casualties1 = {{plainlist| | |||

| * '''Military dead:''' | |||

| * Over 16,000,000 | |||

| * '''Civilian dead:''' | |||

| * Over 45,000,000 | |||

| * '''Total dead:''' | |||

| * Over 61,000,000 | |||

| * (1937–1945) | |||

| * ]}} | |||

| | casualties2 = {{plainlist| | |||

| * '''Military dead:''' | |||

| * Over 8,000,000 | |||

| * '''Civilian dead:''' | |||

| * Over 4,000,000 | |||

| * '''Total dead:''' | |||

| * Over 12,000,000 | |||

| * (1937–1945) | |||

| * ]}} | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox World War II}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{TopicTOC-World War II}} | |||

| '''World War II'''{{efn|Often abbreviated as '''WWII''' or '''WW2'''}} or the '''Second World War''' (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a ] between two coalitions: the ] and the ]. ]—including all the ]s—participated, with many investing all available economic, industrial, and scientific capabilities in pursuit of ], blurring the distinction between military and civilian resources. ] and ], with the latter enabling the ] of population centres and delivery of the ] ever used in war. World War II was the ] in history, resulting in ], more than half being civilians. Millions died in ], including ] of European Jews, as well as from massacres, starvation, and disease. Following the Allied powers' victory, ], ], ], and ] were occupied, and ] tribunals were conducted ] and ]. | |||

| Even though ] had been fighting in ] since 1937, most historians say that the war began on September 1, 1939, when ] invaded ]. Within two days Britain and France declared war on Germany, although the only European battles remained in Poland. Germany was not alone. Pursuant to a then secret provision of its non-aggression ] with the ], Germany was joined in the battle to conquer Poland and to divide Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union on September 17, 1939. The Allies were initially made up of Poland, the ], ], and ]. In May, 1940 Germany invaded western Europe. Six weeks later, France surrendered to Germany. Three months after that, Germany, ], and Japan signed a mutual defense agreement, the ], and were known as the ]. Then, nine months later, in June 1941, while still battling Britain, Germany betrayed and invaded its partner, the Soviet Union, forcing the Soviets into the Allied camp (although they still abided by their non-aggression treaty with Japan). In December 1941, Japan attacked the ] bringing it too into the war on the Allied side. China also joined the Allies, as eventually did most of the rest of the world. By the beginning of 1942, the major combatants were aligned as follows: the British Commonwealth, the United States, and the Soviet Union were fighting Germany and Italy; and the British Commonwealth, China, and the United States were fighting Japan. From then through August 1945, battles raged across all of Europe, in the North Atlantic Ocean, across North Africa, throughout Southeast Asia, throughout China, across the Pacific Ocean and, by air, in Japan. | |||

| The ] included unresolved tensions in the ] and the rise of ] and ]. Key events leading up to the war included ], the ], the outbreak of the ], and Germany's ] and ]. World War II is generally considered to have begun on 1 September 1939, when ], under ], ], prompting the ] and ] to declare war on Germany. Poland was divided between Germany and the ] under the ], in which they had agreed on "]" in Eastern Europe. In 1940, the Soviets ] and ] and ]. After the ] in June 1940, the war continued mainly between Germany and the ], with fighting in the ], ], the aerial ] and ], and naval ]. Through a series of campaigns and treaties, Germany took control of much of ] and ] with ], ], and other countries. In June 1941, Germany led the European Axis in ], opening the ] and initially making large territorial gains. | |||

| Italy surrendered in September 1943, Germany in May 1945. The ] marked the end of the war, on ], ]. | |||

| Japan aimed to ], and by 1937 was at war with the ]. In December 1941, Japan attacked American and British territories ], including ], which resulted in the US and the UK declaring war against Japan, and the European Axis declaring war on the US. ], but its advances in the Pacific were halted in mid-1942 after its defeat in the naval ]; Germany and Italy were ] and at ] in the Soviet Union. Key setbacks in 1943—including German defeats on the Eastern Front, the ] and the ], and Allied offensives in the Pacific—cost the Axis powers their initiative and forced them into strategic retreat on all fronts. In 1944, the Western Allies ], while the Soviet Union ] and pushed Germany and its allies westward. At the same time, Japan suffered reversals in mainland Asia, while the Allies crippled the ] and ]. | |||

| It is possible that around 62 million people ]; estimates vary greatly. About 60% of all casualties were civilians, who died as a result of disease, starvation, ], and aerial bombing. The former Soviet Union and China suffered the most casualties. Estimates place deaths in the Soviet Union at around 23 million, while China suffered about 10 million. Poland suffered the most deaths in proportion to its population of any country, losing approximately 5.6 million out of a pre-war population of 34.8 million (16%). | |||

| The war in Europe concluded with the liberation of ]; the ] and the Soviet Union, culminating in the ] to Soviet troops; ]; and the ] on ]. Following the refusal of Japan to surrender on the terms of the ], the US ] on ] and ] on 6 and 9 August. Faced with an imminent ], the possibility of further atomic bombings, and the Soviet ] against Japan and its ], Japan announced ] on 15 August and signed ] on ], marking the end of the war. | |||

| After World War II, ] was informally split into western and Soviet ]. ] later aligned as ] (NATO), and ] as the ]. There was a shift in power from Western Europe and the ] to the two new superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union. These two rivals would later face off in the ]. In Asia, the United States's military occupation of Japan led to Japan's ]. ] continued through and after the war, resulting eventually in the establishment of the ]. The former colonies of the European powers began their road to independence. | |||

| World War II changed the political alignment and social structure of the world, and it set the foundation of international relations for the rest of the 20th century and into the 21st century. The ] was established to foster international cooperation and prevent conflicts, with the victorious great powers—China, France, the Soviet Union, the UK, and the US—becoming ] of ]. The Soviet Union and the United States emerged as rival ]s, setting the stage for the ]. In the wake of European devastation, the influence of its great powers waned, triggering the ] and ]. Most countries whose industries had been damaged moved towards ]. | |||

| ==Causes== | |||

| ] (left) and ].]] {{main articles|], ], and ]}} | |||

| ==Start and end dates== | |||

| Commonly held general causes for WWII are the rise of nationalism, the rise of militarism, and the presence of unresolved territorial issues. In Germany, resentment of the harsh ], specifically ] the "Guilt Clause", the belief in the '']'', combined with the onset of the ] fueled the rise to power of ]'s militarist ] (the Nazi Party); meanwhile the treaty's provisions were laxly enforced, due to the fear of another war. The ] also failed in its mission of preventing war, for similar reasons. Closely related is the failure of the British and French policy of appeasement, which also through fear of war, gave Hitler time to re-arm. | |||

| {{See also|List of timelines of World War II}} | |||

| {{WWII timeline}} | |||

| World War II began in Europe on 1 September 1939{{sfn|Weinberg|2005|p=6}}<ref>Wells, Anne Sharp (2014) ''Historical Dictionary of World War II: The War against Germany and Italy''. ]. p. 7.</ref> with the ] and the ] and ]'s declaration of war on Germany two days later on 3 September 1939. Dates for the beginning of the ] include the start of the ] on 7 July 1937,<ref>{{Cite book|first1=John|last1=Ferris|first2=Evan|last2=Mawdsley|title=The Cambridge History of the Second World War, Volume I: Fighting the War|location=]|language=en|publisher=]|year=2015}}</ref>{{sfn|Förster|Gessler|2005|p=64}} or the earlier ], on 19 September 1931.<ref>Ghuhl, Wernar (2007) ''Imperial Japan's World War Two'' Transaction Publishers pp. 7, 30</ref><ref>Polmar, Norman; Thomas B. Allen (1991) '']'' {{ISBN|978-0-394-58530-7}}</ref> Others follow the British historian ], who stated that the Sino-Japanese War and war in Europe and its colonies occurred simultaneously, and the two wars became World War II in 1941.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hett |first=Benjamin Carter |date=1 August 1996 |title='Goak here': A.J.P. Taylor and 'The Origins of the Second World War.' |url=https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&issn=00084107&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA18672225&sid=googleScholar&linkaccess=abs |journal=Canadian Journal of History |language=English |volume=31 |issue=2 |pages=257–281 |doi=10.3138/cjh.31.2.257 |access-date=14 September 2022 |archive-date=7 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230307200155/https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&issn=00084107&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA18672225&sid=googleScholar&linkaccess=abs&userGroupName=nm_p_oweb&isGeoAuthType=true |url-status=live |issn = 0008-4107 }}</ref> Other proposed starting dates for World War II include the ] on 3 October 1935.<ref>{{Harvnb|Ben-Horin|1943|p=169}}; {{Harvnb|Taylor|1979|p=124}}; Yisreelit, Hevrah Mizrahit (1965). ''Asian and African Studies'', p. 191.<br />For 1941 see {{Harvnb|Taylor|1961|p=vii}}; Kellogg, William O (2003). '']''. Barron's Educational Series. p. 236 {{ISBN|978-0-7641-1973-6}}.<br />There is also the viewpoint that both World War I and World War II are part of the same "]" or "]": {{Harvnb|Canfora|2006|p=155}}; {{Harvnb|Prins|2002|p=11}}.</ref> The British historian ] views the beginning of World War{{nbsp}}II as the ] fought between ] and the forces of ] and the ] from May to September 1939.{{sfn|Beevor|2012|p=10}} Others view the ] as the start or prelude to World War II.<ref>{{Cite news |date=10 March 2017 |title=In Many Ways, Author Says, Spanish Civil War Was 'The First Battle Of WWII' |website=] |publisher=NPR |url=https://www.npr.org/2017/03/10/519462137/in-many-ways-author-says-spanish-civil-war-was-the-first-battle-of-wwii |url-status=live |access-date=16 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210416013707/https://www.npr.org/2017/03/10/519462137/in-many-ways-author-says-spanish-civil-war-was-the-first-battle-of-wwii |archive-date=16 April 2021}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40105814|title=The Spanish Civil War and the Coming of the Second World War|author=Frank, Willard C.|year=1987|journal=The International History Review|volume=9|issue=3|pages=368–409|doi=10.1080/07075332.1987.9640449|jstor=40105814|access-date=17 February 2022|archive-date=1 February 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220201143429/https://www.jstor.org/stable/40105814|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The exact date of the war's end also is not universally agreed upon. It was generally accepted at the time that the war ended with the armistice of 15 August 1945 (]), rather than with the formal ] on 2 September 1945, which officially ]. A ] was signed in 1951.{{sfn|Masaya|1990|p=4}} A 1990 ] allowed the ] to take place and resolved most post–World War{{nbsp}}II issues.<ref>{{cite web |date=12 September 1990 |title=German-American Relations – Treaty on the Final Settlement concerning Germany |url=https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/2plusfour8994e.htm |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120507180629/https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/2plusfour8994e.htm |archive-date=7 May 2012 |access-date=6 May 2012 |publisher=usa.usembassy.de}}</ref> No formal peace treaty between Japan and the Soviet Union was ever signed,<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180604072306/https://www.atimes.com/article/fact-box-japan-russia-never-signed-wwii-peace-treaty/ |date=4 June 2018 }}. ''Asia Times''.</ref> although the state of war between the two countries was terminated by the ], which also restored full diplomatic relations between them.<ref name=nyt> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211209133402/https://www.nytimes.com/1956/10/20/archives/texts-of-sovietjapanese-statements-peace-declaration-trade-protocol.html?sq=Soviet-Japanese+Joint+Declaration&scp=1&st=p |date=9 December 2021 }} ], page 2, 20 October 1956.<br />Subtitle: "Moscow, October 19. (UP) – Following are the texts of a Soviet–Japanese peace declaration and of a trade protocol between the two countries, signed here today, in unofficial translation from the Russian". Quote: "The state of war between the U.S.S.R. and Japan ends on the day the present declaration enters into force "</ref> | |||

| Japan in the 1930s was ruled by a militarist clique devoted to Japan's becoming a world power. Japan invaded China to secure additional natural resources to compensate for Japan's lack of natural resources. This angered the United States, which reacted by making loans to China, giving China covert military assistance (see ]), and instituting progressively more inclusive embargoes of raw materials against Japan. The embargo of oil and other raw materials by the U.S. would have eventually wrecked Japan's economy; Japan was faced with the choice of withdrawing from China or going to war in order to conquer the oil resources of the ]. It chose to go ahead with plans for the ] | |||

| == |

==History== | ||

| {{Main articles| ], ], ], ], ], and ]}} | |||

| ]. The picture was staged a few days after the outbreak of the war for use in propaganda.]] | |||

| ===Background=== | |||

| ===1939: War breaks out in Europe=== | |||

| {{Main|Causes of World War II}} | |||

| '''Pre-war alliances''' | |||

| {{main articles| ], ] and ]}} | |||

| ====Aftermath of World War I==== | |||

| After the collapse of the ], on ], ] Poland and France pledged to provide each other with military assistance in the event either was attacked. The British already had in March offered support to the Poles, but then on ] Germany and the Soviet Union signed the ]. The pact included a secret protocol, dividing eastern Europe into German and Soviet areas of interest. Each country agreed to allow the other a free hand in its area of influence, to include military occupation. Hitler was now ready to go to war in order to conquer Poland. The signing of a new alliance between Britain and Poland on ] deterred him for only a few days. | |||

| {{stack|] assembly, held in ], Switzerland (1930)]]}} | |||

| ] had radically altered the political European map with the defeat of the ]—including ], ], ], and the ]—and the 1917 ] in ], which led to the founding of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, the victorious ], such as France, Belgium, Italy, Romania, and Greece, gained territory, and new ] were created out of the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian Empires.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Mintz |first1=Steven |title=Historical Context: The Global Effect of World War I |url=https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/teaching-resource/historical-context-global-effect-world-war-i |website=The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |access-date=4 March 2024 |archive-date=4 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240304193001/https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/teaching-resource/historical-context-global-effect-world-war-i |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| '''The invasion of Poland''' | |||

| ], September 1939.]] | |||

| {{main article|Polish September Campaign}} | |||

| On ] Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany. The French mobilized slowly, then mounted only a token offensive in the ], which they soon abandoned, while the British couldn't take any direct action in support of the Poles in the time available (see ]). Meanwhile, on ], the Germans reached ], having slashed through the Polish defenses. | |||

| To prevent a future world war, the ] was established in 1920 by the ]. The organisation's primary goals were to prevent armed conflict through collective security, military, and ], as well as settling international disputes through peaceful negotiations and arbitration.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Gerwarth |first1=Robert |title=Paris Peace Treaties failed to create a secure, peaceful and lasting world order |url=https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/paris-peace-treaties-failed-to-create-a-secure-peaceful-and-lasting-world-order-1.3745849 |newspaper=] |access-date=29 October 2021 |language=en |archive-date=14 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210814213229/https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/paris-peace-treaties-failed-to-create-a-secure-peaceful-and-lasting-world-order-1.3745849 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| On ] Soviet troops occupied the eastern part of Poland, taking control of territory that Germany had agreed was in the Soviet sphere of influence. A day later the Polish president and commander-in-chief both fled to ]. The last Polish units surrendered on ]. Some Polish troops ]. Polish forces continued to ]. | |||

| Despite strong pacifist sentiment ],{{sfn|Ingram|2006|pp=}} ] and ] ] had emerged in several European states. These sentiments were especially marked in Germany because of the significant territorial, colonial, and financial losses imposed by the ]. Under the treaty, Germany lost around 13 percent of its home territory and all ], while German annexation of other states was prohibited, ] were imposed, and limits were placed on the size and capability of the country's ].{{sfn|Kantowicz|1999|p=149}} | |||

| After Poland fell, Germany paused to regroup during the winter of 1939-1940 until April 1940, while the British and French stayed on the defensive. The period would be referred to by journalists as "the ]", or the "''Sitzkrieg''", because so little ground combat took place. | |||

| ====Germany and Italy==== | |||

| '''The Battle of the Atlantic''' | |||

| The German Empire was dissolved in the ], and a democratic government, later known as the ], was created. The interwar period saw strife between supporters of the new republic and hardline opponents on both the political right and left. Italy, as an Entente ally, had made some post-war territorial gains; however, Italian nationalists were angered that the ] by the United Kingdom and France to secure Italian entrance into the war were not fulfilled in the peace settlement. From 1922 to 1925, the ] movement led by ] seized power in Italy with a nationalist, ], and ]ist agenda that abolished representative democracy, repressed socialist, left-wing, and liberal forces, and pursued an aggressive expansionist foreign policy aimed at making Italy a world power, promising the creation of a "New Roman Empire".{{sfn|Shaw|2000|p=35}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main article|Second Battle of the Atlantic}} | |||

| Meanwhile, in the ] German ]s operated against Allied shipping. The submarines made up in skill, luck, and daring what they lacked in numbers. One U-boat sank the British aircraft carrier ] while another U-boat managed to sink the battleship ] in its home anchorage of ]. Altogether the U-boats sank more than 110 vessels in the first four months of the war. | |||

| ] at a German ] political rally in ], August 1933]] | |||

| In the South Atlantic, the ] raided Allied shipping, then was scuttled after the ]. About a year and a half later, another German raider, the ], would suffer a similar fate in the North Atlantic. Unlike the U-boat threat, which had a serious impact a bit later in the war, German surface raiders had little impact due to the fact that their numbers were so small. | |||

| ], after an ] in 1923, eventually ] in 1933 when ] and the Reichstag appointed him. Following Hindenburg's death in 1934, Hitler proclaimed himself ''Führer'' of Germany and abolished democracy, espousing a ], and soon began a massive ].{{sfn|Brody|1999|p=4}} France, seeking to secure its alliance with Italy, ], which Italy desired as a colonial possession. The situation was aggravated in early 1935 when the ] was legally reunited with Germany, and Hitler repudiated the Treaty of Versailles, accelerated his rearmament programme, and introduced conscription.{{sfn|Zalampas|1989|p=62}} | |||

| === |

====European treaties==== | ||

| The United Kingdom, France and Italy formed the ] in April 1935 in order to contain Germany, a key step towards ]; however, that June, the United Kingdom made an ] with Germany, easing prior restrictions. The Soviet Union, concerned by Germany's ], drafted a treaty of mutual assistance with France. Before taking effect, though, the ] was required to go through the bureaucracy of the League of Nations, which rendered it essentially toothless.<ref>{{Harvnb|Mandelbaum|1988|p=96}}; {{Harvnb|Record|2005|p=50}}.</ref> The United States, concerned with events in Europe and Asia, passed the ] in August of the same year.{{sfn|Schmitz|2000|p=124}} | |||

| '''Soviet-Finnish War''' | |||

| {{main articles| ], ]}} | |||

| The Soviet Union attacked Finland on ], ], beginning the ]. Finland surrendered to the Soviet Union in March 1940 and signed the ] in which the Finns made territorial concessions. Later that year, in June the Soviet Union occupied ], ], and ], and annexed ] and ] from Romania. | |||

| Hitler defied the Versailles and ] by ] in March 1936, encountering little opposition due to the policy of ].{{sfn|Adamthwaite|1992|p=52}} In October 1936, Germany and Italy formed the ]. A month later, Germany and Japan signed the ], which Italy joined the following year.{{sfn|Shirer|1990|pp=298–299}} | |||

| '''The invasion of Denmark and Norway''' | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main article| Norwegian Campaign}} | |||

| Germany invaded Denmark and Norway on ], ] in ], in part to counter the threat of an impending Allied invasion of Norway. Denmark did not resist, but Norway fought back, and was joined by British, French, and Polish (exile) forces landing in support of the Norwegians at ], ], and ]. By late June the Allies were defeated, German forces were in control of most of Norway, and what remained of the ] had surrendered. | |||

| ====Asia==== | |||

| '''The invasion of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands''' | |||

| The ] (KMT) party in China launched a ] against ] and nominally unified China in the mid-1920s, but was soon embroiled in ] against its former ] (CCP) allies{{sfn|Preston|1998|p=104}} and ]. In 1931, an ] ], which had long sought influence in China{{sfn|Myers|Peattie|1987|p=458}} as the first step of what its government saw as the country's ], staged the ] as a pretext to ] and establish the ] of ].{{sfn|Smith|Steadman|2004|p=28}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main article| Battle of France}} | |||

| On ], ] the Germans invaded ], ], the ], and France, ending the ''Phony War''. The ] (BEF) and the French Army advanced into northern Belgium, planning on fighting a mobile war in the north while maintaining a static continuous front along the ] further south. The Allied plans were immediately smashed by the most classic example in history of '']''. | |||

| China appealed to the ] to stop the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Japan withdrew from the League of Nations after being ] for its incursion into Manchuria. The two nations then fought several battles, in ], ] and ], until the ] was signed in 1933. Thereafter, Chinese volunteer forces continued the resistance to Japanese aggression in ], and ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Coogan|1993}}: "Although some Chinese troops in the Northeast managed to retreat south, others were trapped by the advancing Japanese Army and were faced with the choice of resistance in defiance of orders, or surrender. A few commanders submitted, receiving high office in the puppet government, but others took up arms against the invader. The forces they commanded were the first of the volunteer armies."</ref> After the 1936 ], the Kuomintang and CCP forces agreed on a ceasefire to present ] to oppose Japan.{{sfn|Busky|2002|p=10}} | |||

| In the first phase of the invasion, ''Fall Gelb'' (CACA), the Wehrmacht's ''Panzergruppe von Kleist'' raced through the ], broke the French line at ], then slashed across northern France to the English Channel, splitting the Allies in two. Meanwhile Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands fell quickly against the attack of German Army Group B. The BEF, encircled in the north, was evacuated from ] in ]. German forces then continued the conquest of France with ''Fall Rot'' (Case Red), advancing behind the Maginot Line and near the coast. France signed an armistice with Germany on ] ], leading to the establishment of the ] puppet government in the unoccupied part of France. | |||

| ===Pre-war events=== | |||

| '''The Battle of Britain''' | |||

| {{main article| Battle of Britain}} | |||

| Following the defeat of France, Britain chose to fight on, so Germany began preparations in summer of 1940 to invade Britain (]). The first step necessary was for the '']'' to secure control of the air over Britain by defeating the '']''. The war between the two air forces became known as the ]. The ''Luftwaffe'' initially targeted ] but thinking the results poor the ''Luftwaffe'' later turned to terror bombing London. The Germans failed to defeat the Royal Air Force, and Operation Sea Lion was postponed and eventually cancelled. | |||

| ====Italian invasion of Ethiopia (1935)==== | |||

| '''The North African Campaign''' | |||

| {{Main|Second Italo-Ethiopian War}} | |||

| ] tanks advance during the North African campaign.]] | |||

| ] inspecting troops during the ], 1935]] | |||

| {{main article| North African Campaign}} | |||

| The Italian declaration of war in June 1940 challenged the British supremacy of the Mediterranean, hinged on ], ], and ]. Italian troops invaded and ] in August 1940. In September 1940 the ] began when Italian forces in ] attacked British forces in ]. The aim was to make Egypt an Italian possession, especially the vital ] east of Egypt. British, ] and ] forces counter-attacked in ], but this offensive stopped in 1941 when much of the Commonwealth forces were transferred to Greece to defend it from German attack. However, German forces (known later as the ]) under General ] landed in Libya and renewed the assault on Egypt. | |||

| The ] was a brief ] that began in October 1935 and ended in May 1936. The war began with the invasion of the ] (also known as ]) by the armed forces of the ] (''Regno d'Italia''), which was launched from ] and ].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GtCL2OYsH6wC |title=Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia |author1=Andrea L. Stanton |author2=Edward Ramsamy |author3=Peter J. Seybolt |page=308 |access-date=6 April 2014 |isbn=978-1-4129-8176-7 |year=2012 |archive-date=7 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230307201327/https://books.google.com/books?id=GtCL2OYsH6wC |url-status=live }}</ref> The war resulted in the ] of Ethiopia and its ] into the newly created colony of ] (''Africa Orientale Italiana'', or AOI); in addition it exposed the weakness of the ] as a force to preserve peace. Both Italy and Ethiopia were member nations, ] when the former clearly violated Article X of the League's ].{{sfn|Barker|1971|pp=131–132}} The United Kingdom and France supported imposing sanctions on Italy for the invasion, but the sanctions were not fully enforced and failed to end the Italian invasion.{{sfn|Shirer|1990|p=289}} Italy subsequently dropped its objections to Germany's goal of absorbing ].{{sfn|Kitson|2001|p=231}} | |||

| '''The invasion of Greece''' | |||

| {{main article| Balkans Campaign}} | |||

| ] on ], ] from bases in ] after the Greek Premier John Metaxas rejected an ultimatum to hand over Greek territory. Despite the enormous superiority of the Italian forces, the Greek army forced the Italians into a massive retreat deep into Albania. By mid-December the Greeks occupied one-fourth of Albania. The Greek army had inflicted upon the Axis Powers their first defeat in the war and Nazi Germany would soon be forced to intervene. | |||

| === |

====Spanish Civil War (1936–1939)==== | ||

| {{Main|Spanish Civil War}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ====European Theatre==== | |||

| ;Lend-Lease | |||

| {{main|Lend-Lease}} | |||

| U.S. President ] signed the Lend-Lease Act on ]. This program was the first large step away from American isolationism, providing for substantial assistance to the U.K., the Soviet Union, and other countries. | |||

| When civil war broke out in Spain, Hitler and Mussolini lent military support to the ], led by General ]. Italy supported the Nationalists to a greater extent than the Nazis: Mussolini sent more than 70,000 ground troops, 6,000 aviation personnel, and 720 aircraft to Spain.{{sfn|Neulen|2000|page=25}} The Soviet Union supported the existing government of the ]. More than 30,000 foreign volunteers, known as the ], also fought against the Nationalists. Both Germany and the Soviet Union used this ] as an opportunity to test in combat their most advanced weapons and tactics. The Nationalists won the civil war in April 1939; Franco, now dictator, remained officially neutral during World War{{nbsp}}II but ].{{sfn|Payne|2008|page=271}} His greatest collaboration with Germany was the sending of ] to fight on the ].{{sfn|Payne|2008|page=146}} | |||

| ;The invasion of Greece and Yugoslavia | |||

| ] | |||

| ] government succumbed to the pressure of the Axis and signed the Tripartite Treaty on ] but the government was overthrown in a coup which replaced it with a pro-Allied one prompting the Germans to invade Yugoslavia on April 6. In the early morning 6th of April Germans bombarded Belgrade with around 450 aircraft. Yugoslavia was occupied in a matter of days and the army surrendered on April 17 but the partisan resistance would last throughout the war. The rapid downfall of Yugoslavia however, allowed German forces to enter Greek territory through the Yugoslav frontier. The 58,000 British and Commonwealth troops who had been sent to help the Greeks were driven back and soon forced to evacuate. On April 27, German forces entered Athens which was followed by the end of organized Greek resistance. The occupation of Greece would prove costly as guerilla warfare would continually plague the Axis occupiers. | |||

| ====Japanese invasion of China (1937)==== | |||

| {{Main|Second Sino-Japanese War}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| ] soldiers during the ], 1937]] | |||

| {{main articles|], ], ], ] and ]}} | |||

| On ], ] Operation Barbarossa, the largest invasion in history, began. Three German army groups, an Axis force of over four million men, advanced rapidly deep into the Soviet Union, destroying almost the entire western Soviet army in huge battles of encirclement. The Soviets dismantled as much industry as possible ahead of the advancing Axis forces, moving it to the Ural mountains for reassembly. By late November the Axis had reached a line at the gates of Leningrad, Moscow, and Rostov, at the cost of about 23 percent casualties, but now their advance ground to a halt. The German General Staff had badly under-estimated the size of the overall Soviet army and its ability to draft new troops and were now dismayed by the presence of new forces, including fresh Siberian troops under General ], and by the onset of a particularly cold winter. German forward units had advanced within distant sight of the golden onion domes of Moscow's ], but then on ] the Soviets counter-attacked and pushed the Axis back some 100-150 miles, the first major German defeat of World War II. | |||

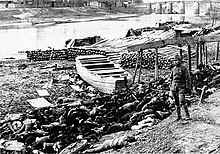

| In July 1937, Japan captured the former Chinese imperial capital of ] after instigating the ], which culminated in the Japanese campaign to invade all of China.{{sfn|Eastman|1986|pp=547–551}} The Soviets quickly signed a ] to lend ] support, effectively ending China's prior ]. From September to November, the Japanese attacked ], engaged the ] ],<ref name="Hsu & Chang 1971 221">{{Harvnb|Hsu|Chang|1971|pp=195–200}}.</ref> and fought ] ].<ref name=Tucker2009>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h5_tSnygvbIC&pg=PA1873|title=A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East : From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East|first=Spencer C.|last=Tucker|year=2009|publisher=ABC-CLIO|access-date=27 August 2017|via=Google Books|isbn=978-1-85109-672-5|archive-date=7 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230307201303/https://books.google.com/books?id=h5_tSnygvbIC&pg=PA1873|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=yang>Yang Kuisong, "On the reconstruction of the facts of the Battle of Pingxingguan"</ref> ] ] deployed his ] to ], but after three months of fighting, Shanghai fell. The Japanese continued to push Chinese forces back, ] in December 1937. After the fall of Nanking, tens or hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians and disarmed combatants were ].<ref>Levene, Mark and Roberts, Penny. ''The Massacre in History''. 1999, pp. 223–224</ref><ref name=tot>Totten, Samuel. ''Dictionary of Genocide''. 2008, 298–299.</ref> | |||

| Meanwhile, on ] the ] between Finland and the Soviet Union began with Soviet air attacks shortly after the beginning of Operation Barbarossa. | |||

| In March 1938, Nationalist Chinese forces won their ], but then the city of ] ] in May.{{sfn|Hsu|Chang|1971|pp=221–230}} In June 1938, Chinese forces stalled the Japanese advance by ]; this manoeuvre bought time for the Chinese to prepare their defences at ], but the ] by October.{{sfn|Eastman|1986|p=566}} Japanese military victories did not bring about the collapse of Chinese resistance that Japan had hoped to achieve; instead, the Chinese government relocated inland to ] and continued the war.{{sfn|Taylor|2009|pp=150–152}}{{sfn|Sella|1983|pp=651–687}} | |||

| ;Allied conferences | |||

| The ] was issued as a joint declaration by ] and President Roosevelt, at Argentia, Newfoundland on ] 1941. | |||

| ====Soviet–Japanese border conflicts==== | |||

| In late December 1941 Churchill met with Roosevelt again at the ]. They agreed that defeating Germany had priority over defeating Japan. The Americans proposed a 1942 cross-channel invasion of France which the British strongly opposed, suggesting instead a small invasion in Norway or landings in ]. The ] was issued. | |||

| {{Main|Soviet–Japanese border conflicts}} | |||

| In the mid-to-late 1930s, Japanese forces in ] had sporadic border clashes with the Soviet Union and ]. The Japanese doctrine of ], which emphasised Japan's expansion northward, was favoured by the Imperial Army during this time. This policy would prove difficult to maintain in light of the Japanese defeat at ] in 1939, the ongoing Second Sino-Japanese War{{sfn|Beevor|2012|p=342}} and ally Nazi Germany pursuing neutrality with the Soviets. Japan and the Soviet Union eventually signed a ] in April 1941, and Japan adopted the doctrine of ], promoted by the Navy, which took its focus southward and eventually led to war with the United States and the Western Allies.<ref>{{cite magazine |author=Goldman, Stuart D. |date=28 August 2012 |title=The Forgotten Soviet-Japanese War of 1939 |access-date=26 June 2015 |magazine=The Diplomat |url=https://thediplomat.com/2012/08/the-forgotten-soviet-japanese-war-of-1939/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150629092821/https://thediplomat.com/2012/08/the-forgotten-soviet-japanese-war-of-1939/ |archive-date=29 June 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Timothy Neeno |access-date=26 June 2015 |title=Nomonhan: The Second Russo-Japanese War |publisher=MilitaryHistoryOnline.com |url=https://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/20thcentury/articles/nomonhan.aspx |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051124070956/https://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/20thcentury/articles/nomonhan.aspx |archive-date=24 November 2005 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ;The Mediterranean | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main articles|], ], ], ] and ]}} | |||

| Rommel's forces advanced rapidly eastward, laying siege to the vital seaport of Tobruk. Two Allied attempts to relieve Tobruk were defeated, but a larger offensive at the end of the year (]) drove Rommel back after heavy fighting. | |||

| ====European occupations and agreements==== | |||

| On ], the ] began when elite German parachute and glider-borne mountain troops launched a massive airborne invasion of the Greek island. Crete was defended by Greek and Commonwealth troops. The Germans attacked the island simultaneously on the three airfields. Their invasion on two of the airfields failed, but they successfully captured one, which allowed them to reinforce their position and capture the island in a little over one week. | |||

| ], ], ], ], and ] pictured just before signing the ], 29 September 1938]] | |||

| In Europe, Germany and Italy were becoming more aggressive. In March 1938, Germany ], again provoking ] from other European powers.{{sfn|Collier|Pedley|2000|p=144}} Encouraged, Hitler began pressing German claims on the ], an area of ] with a predominantly ] population. Soon the United Kingdom and France followed the appeasement policy of British Prime Minister ] and conceded this territory to Germany in the ], which was made against the wishes of the Czechoslovak government, in exchange for a promise of no further territorial demands.{{sfn|Kershaw|2001|pp=121–122}} Soon afterwards, Germany and Italy forced Czechoslovakia to ] to Hungary, and Poland annexed the ] region of Czechoslovakia.{{sfn|Kershaw|2001|p=157}} | |||

| In June 1941, Allied forces invaded ] and ], capturing ] on ]. Later, in August, British and Soviet troops ] in order to secure its oil and a southern supply line to Russia. | |||

| Although all of Germany's stated demands had been satisfied by the agreement, privately Hitler was furious that British interference had prevented him from seizing all of Czechoslovakia in one operation. In subsequent speeches Hitler attacked British and Jewish "war-mongers" and in January 1939 ] to challenge British naval supremacy. In March 1939, ] and subsequently split it into the German ] and a pro-German ], the ].{{sfn|Davies|2006|loc=pp. 143–144 (2008 ed.)}} Hitler also delivered an ] on 20 March 1939, forcing the concession of the ], formerly the German ''Memelland''.{{sfn|Shirer|1990|pp=461–462}} | |||

| ====Pacific Theatre==== | |||

| ;Sino-Japanese war | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Second Sino-Japanese War}} | |||

| A war had begun in East Asia before World War II started in Europe. On ], ], Japan, after occupying ] in 1931, ] against China near ]. The Japanese made initial advances, but were stalled at ]. The city eventually fell to the Japanese and in December 1937, the capital city, Nanking (now ]), fell and the Chinese government moved its seat to ] for the rest of the war. The Japanese forces committed brutal atrocities against civilians and prisoners of war ], slaughtering as many as 300,000 civilians within a month. The war by 1940 had reached a stalemate with both sides making minimal gains. The Chinese had successfully defended their land from oncoming Japanese on several occasions while strong resistance in areas occupied by the Japanese made a victory seem impossible to the Japanese. | |||

| ] (right) and the Soviet leader ], after signing the ], 23 August 1939]] | |||

| ;Japan and the United States enter the war | |||

| Greatly alarmed and with Hitler making further demands on the ], the United Kingdom and France ]; when ] in April 1939, the same guarantee was extended to the ] and ].{{sfn|Lowe|Marzari|2002|p=330}} Shortly after the ]-] pledge to Poland, Germany and Italy formalised their own alliance with the ].{{sfn|Dear|Foot|2001|p=234}} Hitler accused the United Kingdom and Poland of trying to "encircle" Germany and renounced the ] and the ].{{sfn|Shirer|1990|p=471}} | |||

| ] under attack on December 7, 1941]] | |||

| {{main|Attack on Pearl Harbor}} | |||

| The situation became a crisis in late August as German troops continued to mobilise against the Polish border. On 23 August the Soviet Union signed ] with Germany,{{sfn|Shore|2003|p=108}} after tripartite negotiations for a military alliance between France, the United Kingdom, and Soviet Union had stalled.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Watson |first1=Derek |year=2000 |title=Molotov's Apprenticeship in Foreign Policy: The Triple Alliance Negotiations in 1939 |journal=Europe-Asia Studies |volume=52 |issue=4 |pages=695–722 |doi=10.1080/713663077 |jstor=153322 |s2cid=144385167}}</ref> This pact had a secret protocol that defined German and Soviet "spheres of influence" (western ] and Lithuania for Germany; ], Finland, ], ] and ] for the Soviet Union), and raised the question of continuing Polish independence.{{sfn|Dear|Foot|2001|p=608}} The pact neutralised the possibility of Soviet opposition to a campaign against Poland and assured that Germany would not have to face the prospect of a two-front war, as it had in World War{{nbsp}}I. Immediately afterwards, Hitler ordered the attack to proceed on 26 August, but upon hearing that the United Kingdom had concluded a formal mutual assistance pact with Poland and that Italy would maintain neutrality, he decided to delay it.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/DAP-Poland/Campaign-II.html#chapter5|title=The German Campaign In Poland (1939)|access-date=29 October 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140524013551/https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/DAP-Poland/Campaign-II.html#chapter5|archive-date=24 May 2014|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Protesting Japan's incursion into French Indo-China and Japan's continued invasion of China, in the summer of 1941 the United States began an oil embargo against Japan. Japan planned an attack on ] to cripple the ] before consolidating oil fields in the Dutch East Indies. On ], a ] launched a surprise air attack on Pearl Harbor, ]. The raid resulted in two U.S. battleships sunk, and six damaged but later repaired and returned to service. The raid failed to find any aircraft carriers, nor damage Pearl Harbor's usefulness as a naval base. The attack strongly united public opinion in the United States against Japan. The following day, ], the ] on Japan. On the same day, China officially declared war against Japan. Germany declared war on the United States on ], even though it was not obliged to do so under the Tripartite Pact. Hitler hoped that Japan would support Germany by attacking the Soviet Union. Japan did not oblige and this diplomatic move by Hitler proved a catastrophic blunder, unifying the American public's support for the war. | |||

| In response to British requests for direct negotiations to avoid war, Germany made demands on Poland, which served as a pretext to worsen relations.<ref name=ww2db_com>{{cite web |url=https://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=162 |title=The Danzig Crisis |website=ww2db.com |access-date=29 April 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160505010109/https://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=162 |archive-date=5 May 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> On 29 August, Hitler demanded that a Polish ] immediately travel to Berlin to negotiate the handover of ], and to allow a ] in the ] in which the German minority would vote on secession.<ref name=ww2db_com /> The Poles refused to comply with the German demands, and on the night of 30–31 August in a confrontational meeting with the British ambassador ], Ribbentrop declared that Germany considered its claims rejected.<ref name=ibiblio1939>{{cite web |title=Major international events of 1939, with explanation |url=https://www.ibiblio.org/pha/events/1939.html |publisher=Ibiblio.org |access-date=9 May 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130310103815/https://www.ibiblio.org/pha/events/1939.html |archive-date=10 March 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ;Japanese offensive | |||

| ] surrendering Singapore to the Japanese on ], ]. It was the greatest defeat in British history.]] | |||

| {{main articles|], ], ] and ]}} | |||

| Japan soon invaded the Philippines and the British colonies of ], ], ], and ], with the intention of seizing the oilfields of the Dutch East Indies. Despite fierce resistance by American, Philippine, ], ], and ] forces, all these territories capitulated to the Japanese in a matter of months. The British island fortress of ] ] in what Churchill considered one of the most humiliating British defeats of all time. | |||

| ===Course of the war=== | |||

| Japan attacked the Philippines on ], ], just ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Initial aerial bombardment was followed by landings of ground troops both north and south of Manila. The defending Philippine and United States troops were under the command of United States General Douglas MacArthur. The aircraft of his command were destroyed on the ground, for which he was later criticized by military historians; the naval forces were ordered to leave; and because of the circumstances in the Pacific region, reinforcement and resupply of his ground forces were impossible. Under the pressure of superior numbers, the defending forces withdrew to the Bataan Peninsula and to the island of Corregidor at the entrance to Manila Bay. Manila, declared an open city to prevent its destruction, was occupied by the Japanese on January 2, 1942. | |||

| {{For timeline|List of timelines of World War II}} | |||

| {{See also|Diplomatic history of World War II|World War II by country}} | |||

| ====War breaks out in Europe (1939–1940)==== | |||

| The Philippine defense continued until the final surrender of United States-Philippine forces on the Bataan Peninsula in April 1942 and on Corregidor in May. Most of the 80,000 prisoners of war captured by the Japanese at Bataan were forced to undertake the infamous "Death March" to a prison camp 105 kilometers to the north. It is estimated that as many as 10,000 men, weakened by disease and malnutrition and treated harshly by their captors, died before reaching their destination. | |||

| {{Main|European theatre of World War II}} | |||

| ]'' tearing down the border crossing into ], 1 September 1939]] | |||

| On 1 September 1939, Germany ] after ] several ] as a pretext to initiate the invasion.{{sfn|Evans|2008|pp=1–2}} The first German attack of the war came against the ].<ref name="Zabecki2015">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Mq_lCAAAQBAJ&pg=PT1663|title=World War II in Europe: An Encyclopedia|author=David T. Zabecki|date=2015|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-135-81242-3|page=1663|quote=The earliest fighting started at 0445 hours when marines from the battleship Schleswig-Holstein attempted to storm a small Polish fort in Danzig, the Westerplate|access-date=17 June 2019|archive-date=7 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230307201256/https://books.google.com/books?id=Mq_lCAAAQBAJ&pg=PT1663|url-status=live}}</ref> The United Kingdom responded with an ultimatum for Germany to cease military operations, and on 3 September, after the ultimatum was ignored, Britain and France declared war on Germany.<ref>] at 11 am. ] at 5 pm.</ref> During the ] period, the alliance provided no direct military support to Poland, outside of a ].<ref name="Keegan 1997 35">{{Harvnb|Keegan|1997|p=35}}.<br />{{Harvnb|Cienciala|2010|p=128}}, observes that, while it is true that Poland was far away, making it difficult for the French and British to provide support, "ew Western historians of World War II ... know that the British had committed to bomb Germany if it attacked Poland, but did not do so except for one raid on the base of Wilhelmshaven. The French, who committed to attacking Germany in the west, had no intention of doing so."</ref> The Western Allies also began a ], which aimed to damage the country's economy and war effort.<ref>{{Harvnb|Beevor|2012|p=32}}; {{Harvnb|Dear|Foot|2001|pp=248–249}}; {{Harvnb|Roskill|1954|p=64}}.</ref> Germany responded by ordering ] against Allied merchant and warships, which would later escalate into the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Battle of the Atlantic |url=https://www.history.co.uk/history-of-ww2/battle-of-the-atlantic |access-date=11 July 2022 |website=Sky HISTORY TV channel |language=en |archive-date=20 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220520073745/https://www.history.co.uk/history-of-ww2/battle-of-the-atlantic |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===1942: Deadlock=== | |||

| ====European Theatre==== | |||

| ;Western and Central Europe | |||

| {{main articles|] and ]}} | |||

| In May, top Nazi leader ] was assassinated by Allied agents in ]. Hitler ordered severe reprisals. (''See ]''). | |||

| On 8 September, German troops reached the suburbs of ]. The Polish ] to the west halted the German advance for several days, but it was outflanked and encircled by the '']''. Remnants of the Polish army broke through to ]. On 17 September 1939, two days after signing a ], the ]{{sfn|Zaloga|2002|pp=80, 83}} under the supposed pretext that the Polish state had ceased to exist.<ref>{{Cite journal |jstor = 2195670|title = A Case Study in the Soviet Use of International Law: Eastern Poland in 1939|journal = The American Journal of International Law|volume = 52|issue = 1|pages = 69–84|last1 = Ginsburgs|first1 = George|year = 1958|doi = 10.2307/2195670|s2cid = 146904066}}</ref> On 27 September, the Warsaw garrison surrendered to the Germans, and ] ]. Despite the military defeat, Poland never surrendered; instead, it formed the ] and a ] in occupied Poland.{{sfn|Hempel|2005|p=24}} A significant part of Polish military personnel ] and Latvia; many of them later ] in other theatres of the war.{{sfn|Zaloga|2002|pp=88–89}} | |||

| On August 19 British and Canadian forces launched the ] (codenamed Operation Jubilee) on the German occupied port of Dieppe, France. The attack was a disaster but provided critical information utilized later in ] and ]. | |||

| ] ] to ] ].]] | |||

| Germany ] Poland and ]; the Soviet Union ]; small shares of Polish territory were transferred to ] and ]. On 6 October, Hitler made a public peace overture to the United Kingdom and France but said that the future of Poland was to be determined exclusively by Germany and the Soviet Union. The proposal was rejected<ref name=ibiblio1939 /> and Hitler ordered an immediate offensive against France,<ref>Nuremberg Documents C-62/GB86, a directive from Hitler in October 1939 which concludes: "The attack is to be launched this Autumn if conditions are at all possible."</ref> which was postponed until the spring of 1940 due to bad weather.{{sfn|Liddell Hart|1977|pp=39–40}}{{sfn|Bullock|1990|loc=pp. 563–564, 566, 568–569, 574–575 (1983 ed.)}}<ref>Blitzkrieg: From the Rise of Hitler to the Fall of Dunkirk, L Deighton, Jonathan Cape, 1993, pp. 186–187. Deighton states that "the offensive was postponed twenty-nine times before it finally took place."</ref> | |||

| ;Soviet winter and early spring offensives | |||

| {{main articles|], ], ], ] and ]}} | |||

| In the north, Soviets launched the ] ] to ] 1942, trapping a German force near ]. The Soviets also surrounded a German garrison in the ] which held out with air supply for four months (] until ], and established themselves in front of Kholm, Velizh and Velikie Luki. | |||

| ] and ] on the last day of the ], 13 March 1940]] | |||

| In the south, Soviet forces launched an offensive in May against the ], initiating a bloody 17 day battle around ] which resulted in the loss of over 200,000 Red Army personnel. | |||

| After the outbreak of war in Poland, Stalin threatened ], ], and ] with military invasion, forcing the three ] to sign ] allowing the creation of Soviet military bases in these countries; in October 1939, significant Soviet military contingents were moved there.{{sfn|Smith|Pabriks|Purs|Lane|2002|p=24}}{{sfn|Bilinsky|1999|p=9}}{{sfn|Murray|Millett|2001|pp=55–56}} ] refused to sign a similar pact and rejected ceding part of its territory to the Soviet Union. ] in November 1939,{{sfn|Spring|1986|pp=207–226}} and was subsequently expelled from the ] for this crime of aggression.<ref>Carl van Dyke. ''The Soviet Invasion of Finland''. Frank Cass Publishers, Portland, OR. {{ISBN|978-0-7146-4753-1}}, p. 71.</ref> Despite overwhelming numerical superiority, Soviet military success during the ] was modest,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.warhistoryonline.com/war-articles/winter-war-finland.html|title=The Winter War – When the Finns Humiliated the Russians|first=Ivano|last=Massari|publisher=War History Online|date=18 August 2015|access-date=19 December 2021|archive-date=19 December 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211219185618/https://www.warhistoryonline.com/war-articles/winter-war-finland.html|url-status=live}}</ref> and the Finno-Soviet war ended in March 1940 with ].{{sfn|Hanhimäki|1997|p=12}} | |||

| In June 1940, the Soviet Union ] the entire territories of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania,{{sfn|Bilinsky|1999|p=9}} as well as the Romanian regions of ]. In August 1940, Hitler imposed the ] on Romania which led to the transfer of ] to Hungary.{{sfn|Dear|Foot|2001|pp=745, 975}} In September 1940, Bulgaria demanded ] from Romania with German and Italian support, leading to the ].<ref name="Haynes-2000">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=b_I-AQAAIAAJ|title=Romanian policy towards Germany, 1936–40|first=Rebecca|last=Haynes|publisher=]|page=205|year=2000|isbn=978-0-312-23260-3|access-date=3 February 2022|archive-date=7 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230307201243/https://books.google.com/books?id=b_I-AQAAIAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> The loss of one-third of Romania's 1939 territory caused a coup against King Carol II, turning Romania into a fascist dictatorship under Marshal ], with a course set towards the Axis in the hopes of a German guarantee.<ref>Deletant, pp. 48–51, 66; Griffin (1993), p. 126; Ornea, pp. 325–327</ref> Meanwhile, German-Soviet political relations and economic co-operation{{sfn|Ferguson|2006|pp=367, 376, 379, 417}}{{sfn|Snyder|2010|pp=118ff}} gradually stalled,{{sfn|Koch|1983|pp=912–914, 917–920}}{{sfn|Roberts|2006|p=56}} and both states began preparations for war.{{sfn|Roberts|2006|p=59}} | |||

| ;Axis summer offensive | |||

| {{main articles|], ] and ]}} | |||

| On ], the Axis began their summer offensive. German Army Group B was to capture the city of Stalingrad which would secure the German left while Army Group A was to capture the southern oil fields. The ], fought in the late summer and fall of 1942, saw the Axis forces capturing the oil fields. | |||

| ====Western Europe (1940–1941)==== | |||

| ;Stalingrad | |||

| {{Main|Western Front (World War II)}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| ] (shown in dark red)]] | |||

| {{main articles|], ] and ]}} | |||

| After bitter street fighting which lasted for a couple of months, the Germans captured 90% of Stalingrad by November. The Soviets however had been building up massive forces on the flanks of Stalingrad launched ] on ], with twin attacks that met at Kalach four days later trapping the Sixth Army in Stalingrad. The Germans requested permission to attempt a break-out, which was refused by Hitler, who ordered Sixth Army to remain in Stalingrad where he promised they would be supplied by air until rescued. About the same time, the Soviets launched ] in a salient near the vicinity of Moscow. Its objective was to tie down Army Group Center and to prevent it from reinforcing Army Group South at Stalingrad. | |||

| In April 1940, ] to protect shipments of ], which the Allies were ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Murray|Millett|2001|pp=57–63}}.</ref> ], and ], Norway was conquered within two months.{{sfn|Commager|2004|p=9}} ] led to the resignation of Prime Minister ], who was replaced by ] on 10{{spaces}}May 1940.{{sfn|Reynolds|2006|p=76}} | |||

| In December German relief forces got within 30 miles of the trapped Sixth Army before being turned back by the Soviets. By the end of the year, Sixth Army was in desperate condition, as the ''Luftwaffe'' was only able to supply about a sixth of the supplies needed. | |||

| On the same day, Germany ]. To circumvent the strong ] fortifications on the Franco-German border, Germany directed its attack at the neutral nations of ], ], and ].{{sfn|Evans|2008|pp=122–123}} The Germans carried out a flanking manoeuvre through the ] region,{{sfn|Keegan|1997|pp=59–60}} which was mistakenly perceived by the Allies as an impenetrable natural barrier against armoured vehicles.{{sfn|Regan|2004|p=152}}{{sfn|Liddell Hart|1977|p=48}} By successfully implementing new '']'' tactics, the ''Wehrmacht'' rapidly advanced to the Channel and cut off the Allied forces in Belgium, trapping the bulk of the Allied armies in a cauldron on the Franco-Belgian border near Lille. The United Kingdom was able ] from the continent by early June, although they had to abandon almost all their equipment.{{sfn|Keegan|1997|pp=66–67}} | |||

| ;Eastern North Africa | |||

| ].]] | |||

| {{main|Second Battle of El Alamein}} | |||

| On 10 June, ], declaring war on both France and the United Kingdom.{{sfn|Overy|Wheatcroft|1999|p=207}} The Germans turned south against the weakened French army, and ] fell to them on 14{{spaces}}June. Eight days later ]; it was divided into ] and ],{{sfn|Umbreit|1991|p=311}} and an unoccupied ] under the ], which, though officially neutral, was generally aligned with Germany. France kept its fleet, which ] on 3{{spaces}}July in an attempt to prevent its seizure by Germany.{{sfn|Brown|2004|p=198}} | |||

| At the beginning of 1942, the Allied forces in North Africa were weakened by detachments to the Far East. Rommel once again attacked and recaptured ]. Then he defeated the Allies at the ], and captured Tobruk with several thousand prisoners and large quantities of supplies. Following up, he drove deep into Egypt but with overstretched forces. | |||

| The air ]{{sfn|Keegan|1997|p=}} began in early July with ].<ref name=Murray_BoB>{{harvnb|Murray|1983|loc=.}}</ref> The ] started in August but its failure to defeat ] forced the indefinite postponement of the ]. The German ] offensive intensified with night attacks on London and other cities in ], but largely ended in May 1941{{sfn|Dear|Foot|2001|pp=108–109}} after failing to significantly disrupt the British war effort.{{r|Murray_BoB}} | |||

| The ] took place in July 1942. Allied forces had retreated to the last defensible point before ] and the ]. The ''Afrika Korps'', however, had outrun its supplies, and the defenders stopped its thrusts. The ] occurred between ] and ]. Lieutenant-General ] was in command of the Commonwealth forces, now known as the ]. The Eighth Army took the offensive, and was ultimately triumphant. After the German defeat at El Alamein, the Axis forces made a successful strategic withdrawal to ]. | |||

| Using newly captured French ports, the German Navy ] against an over-extended ], using ]s against British shipping ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Goldstein|2004|p=35}}</ref> The British ] scored a significant victory on 27{{spaces}}May 1941 by ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Steury|1987|p=209}}; {{Harvnb|Zetterling|Tamelander|2009|p=282}}.</ref> | |||

| '''Western North Africa''' | |||

| {{main articles| ] and ]}} | |||

| ] was launched on ], ] and aimed to gain control of ] and ] through simultaneous landings at ], ] and Algiers, followed a few days later with a landing at ], the gateway to Tunisia. It was hoped that the local forces of ] would put up no resistance and submit to the authority of ] General ]. In response Hitler invaded and occupied Vichy France and Tunisia, but the German and Italian forces were caught in the pincers of a twin advance from Algeria and Libya. Rommel's victory against American forces at the ] could only hold off the inevitable. | |||

| In November 1939, the United States was assisting China and the Western Allies, and had amended the ] to allow "]" purchases by the Allies.{{sfn|Overy|Wheatcroft|1999|pp=328–330}} In 1940, following the German capture of Paris, the size of the ] was ]. In September the United States further agreed to a ].{{sfn|Maingot|1994|p=52}} Still, a large majority of the American public continued to oppose any direct military intervention in the conflict well into 1941.{{sfn|Cantril|1940|p=390}} In December 1940, Roosevelt accused Hitler of planning world conquest and ruled out any negotiations as useless, calling for the United States to become an "]" and promoting ] programmes of military and humanitarian aid to support the British war effort; Lend-Lease was later extended to the other Allies, including the Soviet Union after it was ] by Germany.<ref name=ibiblio_1940>{{cite web |title=Major international events of 1940, with explanation |url=https://www.ibiblio.org/pha/events/1940.html |publisher=Ibiblio.org |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130525060313/https://www.ibiblio.org/pha/events/1940.html |archive-date=25 May 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> The United States started strategic planning to prepare for a full-scale offensive against Germany.<ref>{{cite web |author=Skinner Watson, Mark |title=Coordination With Britain |website=US Army in WWII – Chief of Staff: Prewar Plans and Operations |url=https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-WD-Plans/USA-WD-Plans-12.html |access-date=13 May 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130430001549/https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-WD-Plans/USA-WD-Plans-12.html |archive-date=30 April 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ====Pacific Theatre==== | |||

| '''Central and South West Pacific''' | |||

| ] over the burning Japanese cruiser Mikuma during the ].]] | |||

| {{main articles|], ] and ]}} | |||

| On ] 1942, Roosevelt signed ], leading to the ] for the duration of the war. | |||

| At the end of September 1940, the ] formally united Japan, Italy, and Germany as the ]. The Tripartite Pact stipulated that any country—with the exception of the Soviet Union—that attacked any Axis Power would be forced to go to war against all three.{{Sfn|Bilhartz|Elliott|2007|p=179}} The Axis expanded in November 1940 when ], ], and ] joined.{{Sfn|Dear|Foot|2001|p=877}} ] and ] later made major contributions to the Axis war against the Soviet Union, in Romania's case partially to recapture ].{{Sfn|Dear|Foot|2001|pp=745–746}} | |||

| In April, the ], the first U.S. air raid on Tokyo, boosted morale in the U.S. and caused Japan to shift resources to homeland defence, but did little actual damage. | |||

| ====Mediterranean (1940–1941)==== | |||

| In early May, a Japanese naval invasion of ], ], was thwarted by Allied navies in the ]. This was both the first successful opposition to a Japanese attack and the first battle fought between aircraft carriers. | |||

| {{Main|Mediterranean and Middle East theatre of World War II}} | |||

| In early June 1940, the Italian '']'' ], a British possession. From late summer to early autumn, Italy ] and made an ]. In October, ], but the attack was repulsed with heavy Italian casualties; the campaign ended within months with minor territorial changes.{{sfn|Clogg|2002|p=118}} To assist Italy and prevent Britain from gaining a foothold, Germany prepared to invade the Balkans, which would threaten Romanian oil fields and strike against British dominance of the Mediterranean.<ref>{{Harvnb|Evans|2008|pp=146, 152}}; {{Harvnb|US Army|1986|pp=}}</ref> | |||

| A month later, on ], American carrier-based dive-bombers sank four of Japan's best aircraft carriers in the ]. Historians mark this battle as a turning point, the end of Japanese expansion in the Pacific. Cryptography played an important part in the battle, as the United States had ] and knew the Japanese plan of attack. | |||

| ] of the ] advancing across the North African desert, April 1941]] | |||

| In July a Japanese ] on Port Moresby was led along the rugged Kokoda Track. An outnumbered and untrained Australian battalion defeated the 5,000-strong Japanese force, the first land defeat of Japan in the war, and one of the most significant victories in ]. | |||

| In December 1940, British Empire forces began ] against Italian forces in Egypt and ].{{sfn|Jowett|2001|pp=9–10}} The offensives were successful; by early February 1941, Italy had lost control of eastern Libya, and large numbers of Italian troops had been taken prisoner. The ] also suffered significant defeats, with the Royal Navy putting three Italian battleships out of commission after a ], and neutralising several more warships at the ].{{sfn|Jackson|2006|p=106}} | |||

| ] | |||

| On ], United States Marines began the ]. For the next six months, US forces fought Japanese forces for control of the island. Meanwhile, several naval encounters raged in the nearby waters, including the ], ], ], and ]. In late August and early September, while battle raged on Guadalcanal, an amphibious Japanese attack on the eastern tip of New Guinea was met by Australian forces in the ]. | |||

| Italian defeats prompted Germany to ] to North Africa; at the end of March 1941, ]'s ] ] which drove back Commonwealth forces.{{sfn|Laurier|2001|pp=7–8}} In less than a month, Axis forces advanced to western Egypt and ].{{sfn|Murray|Millett|2001|pp=263–276}} | |||

| '''Sino-Japanese War''' | |||

| {{main article|Battle of Changsha (1942)}} | |||

| Japan launched a major offensive in China following the attack on Pearl Harbor. The aim of the offensive was to take the strategically important city of Changsha which the Japanese had failed to capture on two previous occasions. For the attack the Japanese massed 120,000 soldiers under 4 divisions. The Chinese responded with 300,000 men and soon the Japanese army was encircled and had to retreat. | |||

| By late March 1941, ] and ] signed the ]; however, the Yugoslav government was ] by pro-British nationalists. Germany and Italy responded with simultaneous invasions of both ] and ], commencing on 6 April 1941; both nations were forced to surrender within the month.{{sfn|Gilbert|1989|pages=174–175}} The airborne ] at the end of May completed the German conquest of the Balkans.{{sfn|Gilbert|1989|pages=184–187}} Partisan warfare subsequently broke out against the ], which continued until the end of the war.{{sfn|Gilbert|1989|pages=208, 575, 604}} | |||

| ===1943: The war turns=== | |||

| ====European Theatre==== | |||

| '''German and Soviet spring offensives''' | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main articles| ] and ]}} | |||

| After the surrender of the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad on ], ], the ] launched eight offensives during the winter, many concentrated along the ] near Stalingrad, which resulted in initial gains until German forces were able to take advantage of the weakened condition of the Red Army and regain the territory it lost. | |||

| In the Middle East in May, Commonwealth forces ] which had been supported by German aircraft from bases within Vichy-controlled ].{{sfn|Watson|2003|p=80}} Between June and July, British-led forces ], assisted by the ].<ref>{{Citation|last=Morrisey|first=Will|chapter=What Churchill and De Gaulle learned from the Great War|date=2019|pages=119–126|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0-429-02764-2|doi=10.4324/9780429027642-6|title=Winston Churchill|s2cid=189257503}}</ref> | |||

| '''Operation Citadel''' | |||

| ]s and ]s of the ] during the start of ''Operation Zitadelle'']] | |||

| {{main article| Battle of Kursk}} | |||

| On July 4, the Wehrmacht launched a much-delayed offensive against the Soviet Union at the ] salient. Their intentions were known by the Soviets who had hastened to defend the salient with an enormous system of earthwork defenses. Both sides massed their armor for what became a decisive military engagement. The Germans attacked from both the north and south of the salient and hoped to meet in the middle, cutting off the salient and trapping 60 Soviet divisions. The German offensive got ground down as little progress was made through the Soviet defenses. The Soviets then brought up their reserves and the largest tank battle of the war occurred near the city of Prokhorovka. The Germans had exhausted their armored forces and could not stop the Soviet counter-offensive that threw them back across their starting positions. | |||

| ====Axis attack on the Soviet Union (1941)==== | |||

| '''Soviet fall and winter offensives''' | |||

| {{Main|Eastern Front (World War II)}} | |||

| {{main articles| ], ] and ]}} | |||

| ] animation map, 1939–1945 – Red: ] and the Soviet Union after 1941; Green: ] before 1941; Blue: ]]] | |||

| In August Hitler agreed to a general withdrawal to the Dnieper line and as September proceeded into October, the Germans found the Dnieper line impossible to hold as the Soviet bridgeheads grew, and important Dnieper towns started to fall, with Zaporozhye the first to go, followed by Dnepropetrovsk. | |||

| With the situation in Europe and Asia relatively stable, Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union made preparations for war. With the Soviets wary of mounting tensions with Germany, and the Japanese planning to take advantage of the European War by seizing resource-rich European possessions in ], the two powers signed the ] in April 1941.{{sfn|Garver|1988|p=114}} By contrast, the Germans were steadily making preparations for an attack on the Soviet Union, massing forces on the Soviet border.{{sfn|Weinberg|2005|p=195}} | |||

| Early in November the Soviets broke out of their bridgeheads on either side of Kiev and recaptured the Ukrainian capital. | |||

| Hitler believed that the United Kingdom's refusal to end the war was based on the hope that the United States and the Soviet Union would enter the war against Germany sooner or later.{{sfn|Murray|1983|p=}} On 31 July 1940, Hitler decided that the Soviet Union should be eliminated and aimed for the conquest of ], the ] and ].<ref name="GSWW4_26">{{Harvnb|Förster|1998|p=26}}.</ref> However, other senior German officials like Ribbentrop saw an opportunity to create a Euro-Asian bloc against the British Empire by inviting the Soviet Union into the Tripartite Pact.<ref name="GSWW4_38">{{Harvnb|Förster|1998|pp=38–42}}.</ref> In November 1940, ] to determine if the Soviet Union would join the pact. The Soviets showed some interest but asked for concessions from Finland, Bulgaria, Turkey, and Japan that Germany considered unacceptable. On 18 December 1940, Hitler issued the directive to prepare for an invasion of the Soviet Union.{{sfn|Shirer|1990|pp=810–812}} | |||

| First Ukrainian Front attacked at Korosten on Christmas eve. The Soviet advance continued along the railway line until the 1939 Polish-Soviet border was reached. | |||

| On 22 June 1941, Germany, supported by Italy and Romania, invaded the Soviet Union in ], with Germany accusing the Soviets of ]; they were joined shortly by Finland and Hungary.<ref name=Events1941>{{citation |last1=Klooz |first1=Marle |last2=Wiley |first2=Evelyn |others=Director: Humphrey, Richard A. |year=1944 |title=Events leading up to World War II – Chronological History |series=78th Congress, 2d Session – House Document N. 541 |location=Washington, DC |publisher=US Government Printing Office |at=pp. 267–312 () |url=https://www.ibiblio.org/pha/events/ |access-date=9 May 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131214113907/https://www.ibiblio.org/pha/events/ |archive-date=14 December 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> The primary targets of this surprise offensive{{sfn|Sella|1978|p=555}} were the ], Moscow and Ukraine, with the ] of ending the 1941 campaign near the ]—from the ] to the ]s. Hitler's objectives were to eliminate the Soviet Union as a military power, exterminate ], generate '']'' ("living space"){{sfn|Kershaw|2007|pp=66–69}} by ],{{sfn|Steinberg|1995}}<!--please, don't add "page needed" template: it is a journal article--> and guarantee access to the strategic resources needed to defeat Germany's remaining rivals.{{sfn|Hauner|1978}}<!--please, don't add "page needed" template: it is a journal article--> | |||

| '''Italy''' | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main article|Italian Campaign}} | |||

| The surrender of Axis forces in Tunisia on ], ] yielded some 250,000 prisoners. The North African war proved to be a disaster for Italy and when the Allies invaded ] on ] in ], capturing the island in a little over a month, it caused the regime of ] to collapse. On ] he was removed from office by the King of Italy, and arrested with the positive consent of the Great Fascist Council. A new government, led by ], took power but declared that Italy would stay in the war. Badoglio actually had begun secret peace negotiations with the Allies. | |||