| Revision as of 15:47, 19 August 2004 editXezbeth (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators282,561 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:13, 4 December 2024 edit undo152.3.43.46 (talk) Fixed typoTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American champion thoroughbred racehorse (1933–1947)}} | |||

| '''Seabiscuit''' (]-]) was a champion ] ] ]. From an inauspicious start, Seabiscuit became an unlikely champion, and during the ] became a something of symbol of hope to many unemployed Americans. At the peak of his fame in 1938, it was suggested that he had generated more newsprint in the US than either ] or ]. | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{More citations needed|date=May 2021}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=April 2019}} | |||

| {{Infobox racehorse | |||

| |horsename= Seabiscuit | |||

| |image= Seabiscuit workout with GW up.jpg | |||

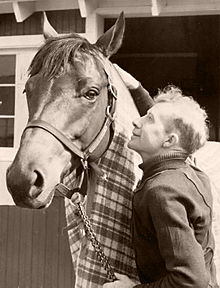

| |caption= ] on Seabiscuit | |||

| |sire= ] | |||

| |grandsire = ] | |||

| |dam= Swing On | |||

| |damsire= ] | |||

| |sex= ] | |||

| | foaled = {{birth date|1933|05|23|df=y}} | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1947|05|17|1933|05|23|df=y}} | |||

| |country= ] | |||

| |colour= Light Bay | |||

| |breeder= ] | |||

| |owner= ] | |||

| |trainer= 1) ]<br />2) ] | |||

| |record= 89: 33–15–1 | |||

| |earnings= $437,730 | |||

| |race= ] (1936)<br />] (1937)<br />] (1937)<br />] (1937)<br />] (1937)<br />] (1937)<br />] (1937, 1938)<br />] (1938)<br />] (1938)<br />] vs ] (1938)<br />] vs ] (1938)<br />] (1938)<br />] (1940)<br />] (1940) | |||

| |awards= ] (1937 & 1938)<br />] (1938) | |||

| |honors= ] (1958)<br />]<br />] at ] and Saratoga Springs<br/>] ] at ] (2014– ) | |||

| |updated= 21 November 2021 | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Seabiscuit''' (May 23, 1933 – May 17, 1947) was a champion ] ] in the ] who became the top money-winning racehorse up to the 1940s. He beat the 1937 Triple Crown winner, ], by four lengths in a two-horse special at ] and was voted ] for 1938. | |||

| ==Early Days== | |||

| Born on ], 1933 from the mare ] and sired by ] (son of ]), the bay colt grew up on Claiborne Farm in ]. He was undersized, knobby-kneed, and not much to look at, and was given to sleeping and eating for long periods. Initially he was trained by the legendary "Sunny" ], who had taken ] to the United States ]. Fitzsimmons saw some potential in Seabiscuit, but felt the horse was lazy, and most of with most of his time taken training ] (another Triple Crown winner) Seabiscuit was relegated to a punishing schedule of small races. In his first 10 races he failed to win and most times finished well back of the field. After that, training him for ] was almost an afterthought and the horse was sometimes the butt of people's jokes. Then, as a three-year-old, Seabiscuit raced thirty five times, winning five times, running second seven times. Still, at the end of the racing season, he was used as a work horse. The next racing season, the colt was again less than spectacular and his owners "unloaded" the horse for $8,000, to automobile entrepreneur ]. | |||

| A small horse, at 15.2 ] high,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/community/chat_03/2003-07-25-paulick.htm|title=USATODAY.com|website=USA Today |access-date=April 14, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160524155405/http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/community/chat_03/2003-07-25-paulick.htm|archive-date=May 24, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> Seabiscuit had an inauspicious start to his racing career, winning only a quarter of his first 40 races, but became an unlikely champion and a symbol of hope to many Americans during the ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ==1936–37: The Beginning of Success == | |||

| His new trainer, Tom Smith, understood the horse and slowly his unorthodox training methods raised the horse from its lethargy. Smith paired the horse with ] jockey ] (1909-1981), who was had gained much experience racing in the West and in Mexico, but was now down on his luck. On ], ] Seabiscuit raced for the first time for his new jockey and trainer, in ], without impressing. But improvements came quickly and in their remaining eight races in the East, Seabiscuit and Pollard won several times, including Detroit's Governor's Handicap (worth $5,600) and the Scarsdale Handicap (worth $7,300). In early November 1936, Howard and Smith shipped the horse to California in a rail car. His last two races of the year were at ] racetrack in ], and gave some clue as to what was to come. The first was the $2,700 Bay Bridge Handicap, run over one mile. Seabiscuit started badly from the stalls, but, despite carrying the top weight of 116lb, ran through the field before easing up to win by five lengths, in a time only two fifths of a second outside the world record. This electric form was carried over to the World's Fair Handicap (Bay Meadows' most prestigious ]) with Seabiscuit leading throughout, to win by a distance. | |||

| Seabiscuit has been the subject of numerous books and films, including ''Seabiscuit: the Lost Documentary'' (1939); the ] film '']'' (1949); a book, '']'' (1999) by ]; and a film adaptation of Hillenbrand's book, '']'' (2003), that was nominated for the ]. There is also a street in Indian Trail, North Carolina named after him. | |||

| For 1937, Howard and Smith turned their attention to February's ]. The race, California's most prestigious, was worth over $125,000 to the winner and was known colloquially as "The Hundred Grander". In their first warm up race at ], they again won easily. In his second race of 1937 (the ]) Seabiscuit suffered a setback. Bumped at the start, and then pushed wide the horse trailed in fifth, with the win going to the highly fancied ]. | |||

| ==Early days== | |||

| The two would be rematched in the Hundred Grander just a week later. After half a mile, front runner Special Agent was clearly tired and Seabiscuit seemed perfectly placed to capitalise, before inexplicably slowing on the final straight. The fast closing Rosemont took his chance, edging out Seabiscuit by a nose. The defeat was devasting to Smith and Howard, and widely attributed in the press to a riding error. Pollard, who had seemingly not seen Rosemont over his shoulder until too late, had lost the sight in one eye in a racing accident, a fact he hid throughout his career. Regardless, the horse was rapidly becoming a favorite among Californian racing fans, and his fame spread as he won his next three races, before Howard chose to again relocate the horse, this time for the more prestigious Eastern racing circuit. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Seabiscuit was ] in ], on May 23, 1933,<ref>{{cite web |website=IMDb |url= https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1403453/?ref_=fn_al_nm_1 |title= Seabiscuit (1933–1947)}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |website= IMDb |title= Seabiscuit Biography |url= https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1403453/bio?ref_=nm_ov_bio_sm}}</ref> from the ] Swing On and ] ], a son of ].<ref name=SEP>{{cite news|title=Champion|date=April 27, 1940 |work= ] |volume=212 |number= 44 |page=28}}</ref> Seabiscuit was named for his father; "sea biscuit" is another name for ], a type of cracker eaten by sailors.<ref name="FoodH">{{cite news |author= Stradley, Linda |date= 2004 |url= http://whatscookingamerica.net/Glossary/H.htm |work= Linda's Culinary Dictionary |title= H (see "hardtack") |access-date= June 18, 2015 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20150709182253/http://whatscookingamerica.net/Glossary/H.htm |archive-date= July 9, 2015 |url-status= live }}</ref>{{Additional citation needed|date=May 2024}} | |||

| The ] colt grew up on ] in ], where he was trained. He was undersized, knobby-kneed,<ref name=SEP/> and given to sleeping and eating for long periods. | |||

| Once there, Seabiscuit's run of victories continued unabated. Between June 26 and August 7, he ran five times, each time a stakes race, and each time he won, despite steadily increasing imposts of up to 130lbs. The seven consecutive stakes victories tied the record. On September 11, Smith accepted an impost of 132lbs for the Narragansett Special. On race day, the ground was slow and heavy, and entirely unsuited to the Biscuit, even without the heaviest burden of his career. Smith wished to scratch, but Howard overruled him. Seabiscuit was never in the running, and trudged home in third, four lengths behind Calumet Dick, who was carrying only 115lbs. The streak was snapped, but the season was not over. Seabiscuit won his next three races (one a dead heat) before finishing the year with a valiant second place at Pimlico. | |||

| Initially, Seabiscuit was owned by the powerful ] and trained by ], who had taken ] to the United States ]. Fitzsimmons saw some potential in Seabiscuit but felt the horse was too lazy. Fitzsimmons devoted most of his time to training ], who won the 1935 Triple Crown. | |||

| In 1937, Seabisuit won eleven of his fifteen races and was the leading money winner in the ] that year. On the West Coast, he had risen to the status of celebrity. His races were followed fanatically on the radio and newsreel and filled hundreds of column inches in the newspapers. Howard, with his business acumen, was ready to cash in, marketing a full range of merchandise to the fans. Considerably less impressed was the Eastern racing establishment. The great three year old, ], had won the Triple Crown that season and was voted the most prestigious honor, ]. | |||

| Seabiscuit was relegated to a heavy schedule of smaller races. He failed to win any of his first 17 races, usually finishing back in the field. After that, Fitzsimmons did not spend much time on him, and the horse was sometimes the butt of stable jokes. However, Seabiscuit began to gain attention after winning two races at ] and setting a new track record in the second—Claiming Stakes race. | |||

| ==The Best Horse in America== | |||

| In 1938, as a five year old, Seabiscuit's success would continue, but it would be without Pollard. On February 19, Pollard suffered a terrible fall while racing on Fair Knightess, another Howard horse. With Pollard's chest crushed by the weight of the fallen horse, and his ribs and arm broken, Howard trialed three new jockeys, before deciding on ], a great rider and old friend of Pollard, to ride Seabiscuit. | |||

| As a two-year-old, Seabiscuit raced 35 times (a heavy racing schedule),<ref name=SEP/> coming in first five times and finishing second seven times. These included three ]s, in which he could have been purchased for $2,500, but he had no takers.<ref name=SEP/> | |||

| Woolf's first race would be the Santa Anita Handicap, the "hundred grander" that Seabiscuit had narrowly lost the previous year. Seabiscuit was drawn on the outside, and from the start was impeded by another horse, Count Atlas, angling out. The two were locked together for the first straight and by the time Woolf had his horse disentangled, they were six lengths from the pace. The pair battled hard, but were beaten by the fast finishing Stagehand, which had been assigned 30lbs fewer than Seabiscuit. Regardless, racegoers knew that Seabiscuit was the moral victor, a fact gladly conceded by Stagehand's jockey. | |||

| While Seabiscuit had not lived up to his racing potential, he was not the poor performer Fitzsimmons had taken him for. His last two wins as a two-year-old came in minor stakes races. The next season started with a similar pattern. The colt ran 12 times in less than four months, winning four times. One of those races was a cheap allowance race on the "sweltering afternoon of June 29," 1936, at ]. That was where trainer ] first laid eyes on Seabiscuit.<ref>{{cite book |author-link= Laura Hillenbrand |author= Hillenbrand, Laura |date=2001 |title= Seabiscuit: An American Legend|publisher= Random House Publishing |isbn= 978-0-449-00561-3 |url= https://archive.org/details/seabiscuitameric00hill |url-access= registration }}</ref> His owners sold the horse to automobile entrepreneur ] for $8,000 at ], in August.<ref name=SEP/> | |||

| Throughout 1937 and '38, there was much speculation in the media that there would be a match race between him and the seemingly invincible War Admiral. The two horses had been scheduled to meet in three stakes races, but one or the other was scratched, usually due to Seabiscuit's disliking of heavy ground. After extensive negotiation a match race was organised for May 1938 at Belmont, but again Seabiscuit scratched, being not fully fit. By June, however, Pollard had made a recovery and on June 23 agreed to work a young colt named Modern Youth. Spooked by something on the track, the horse broke rapidly through the stables and threw Pollard, shattering his leg, and seemingly ending his career. | |||

| ==1936/1937: The beginning of success == | |||

| A match race was held but it would not be against War Admiral. Instead it was against Ligaroti, a highly regarded horse owned by the ] entertainer ] in an event organized to promote Crosby's resort and racetrack in ]. With Woolf aboard, Seabiscuit won that race, despite persistent fouling from Ligaroti's jockey. After three more outings, with only one win, he would finally go head to head with War Admiral in the ] Special in ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Howard assigned Seabiscuit to a new trainer, ],<ref name=SEP/> who, with his unorthodox training methods, gradually brought Seabiscuit out of his lethargy. Smith paired the horse with ] jockey ] (1909–1981), who had experience racing in the ] and in Mexico. On August 22, 1936, they raced Seabiscuit for the first time. Improvements came quickly, and in their remaining eight races in the ], Seabiscuit and Pollard won several times, including the Detroit Governor's Handicap (worth $5,600) and the ] ($7,300) at ] in ]. | |||

| In early November 1936, Howard and Smith shipped the horse to California by rail. His last two races of the year were at ] racetrack in ]. The first was the $2,700 Bay Bridge Handicap, run over {{convert|1|mi|km|adj=on|spell=in}}. Despite starting badly and carrying the top weight of {{convert|116|lb|kg}}, Seabiscuit won by five lengths. At the World's Fair Handicap (Bay Meadows' most prestigious ]), Seabiscuit led throughout. | |||

| === The "Match Of The Century" === | |||

| In 1937, the ], California's most prestigious race, was worth over $125,000 (${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|2|2010|r=1}}}} million in 2010) to the winner; it was known colloquially as "The Hundred Grander." In his first warm-up race at ], Seabiscuit won easily. In his second race of 1937, the ], he suffered a setback after he was bumped at the start and then pushed wide; Seabiscuit came in fifth, losing to ]. | |||

| On ], ], Seabiscuit met War Admiral in what was dubbed as the "''Match of the Century''". The event itself, run over a mile and 3/16, was one of the most anticipated sporting events in US history. The Pimlico racetrack, from the grandstands to the infield, was jammed solid with fans. Trains were run from all over the country to bring rooters to the race, and the estimated 40,000 at the track were joined by some 40 million listening on the radio. War Admiral was the prohibitive favorite (1-4 with most bookmakers) and a near unanimous selection of the writers and tipsters, excluding the California faithful. | |||

| The two met again in the Santa Anita Handicap a week later, where Rosemont won by a nose. The defeat was devastating to Smith and Howard and was widely attributed in the press to a jockey error.<ref name=SEP/>{{cref|a}} Pollard, who had not seen Rosemont over his shoulder until too late, was blind in one eye due to an accident during a training ride, a fact he had hidden throughout his career. A week after this defeat Seabiscuit won the ] by seven lengths in track record time of 1:48{{frac|4|5}} for the {{frac|1|1|8}} mile event.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.newspapers.com/search/#lnd=1&query=San+Juan+Capistrano+Sea+Biscuit+Lowry+GRAND+MANITOU+Lengths&ymd=1937-03-07 |title=Seabiscuit Triumphs By Seven Lengths (1937 San Juan Capistrano Handicap - race 6: ''held 6 March 1937'') |work=] |date=7 March 1937 |access-date=18 June 2020 |pages=25, 26 | first = Paul | last = Lowry }}</ref> | |||

| Head-to-head races almost always favor fast starters, and War Admiral's speed from the gate was the stuff of legend. Seabiscuit, on the other hand, was a pace stalker, skilled at holding with the pack before destroying the field with late acceleration. From the scheduled walk up start, few gave him a chance to head War Admiral into the first turn. Smith knew these things, and had been secretly training the Biscuit to run against type, using a starting bell and a whip to give the horse a ] burst of speed from the start. | |||

| Seabiscuit was rapidly becoming a favorite among California racing fans, and his fame spread as he won his next three races. With his successes, Howard decided to ship the horse east for its more prestigious racing circuit. | |||

| When the bell went, Seabiscuit ran away from the Triple Crown Champion. Despite being drawn on outside and led by over a length after just 20 seconds. Halfway down the back straight, War Admiral started to eat back into the lead, gradually pulling level, and then slightly ahead. Following advice he had received from Pollard, Woolf allowed his horse to see his rival, and then asked for more effort. Two hundred yards from the wire, Seabiscuit pulled away again as the competition proved too much for War Admiral, and continued to extend his lead over the closing straight, finally winning by four clear lengths. | |||

| Seabiscuit's run of victories continued. Between June 26 and August 7, he ran five times, each time in a ], and each time he won under steadily increasing ] of up to {{convert|130|lb|kg}}. For the third time, Seabiscuit faced off against Rosemont again, this time beating him by seven lengths. On September 11, Smith accepted an impost of {{convert|132|lb|kg}} for the Narragansett Special at ]. On race day, the ground was slow and heavy, and unsuited to "the Biscuit", carrying the heaviest burden of his career. Smith wanted to ], but Howard overruled him. Never in the running, Seabiscuit finished third. His winning streak was snapped, but the season was not over; Seabiscuit won his next three races (one a ]) before finishing the year with a second-place at ]. | |||

| As a result of his races that year and the victory over War Admiral, Seabiscuit was named "Horse of the Year" for ]. The only prize that had eluded him was the Hundred Grander. | |||

| In 1937, Seabiscuit won 11 of his 15 races and was the year's leading money winner in the ]. However, ], having won the ] that season, was voted the most prestigious honor, the ]. | |||

| ==Injury and Return== | |||

| When the horse recommenced training for the ] season, all Howard and Smith's eyes were trained firmly on that year's Santa Anita Handicap. The horse had got fat through the winter, but appalling weather gave Smith few opportunities to race him, or even work him hard. On February 14, the rains relented long enough for the horse to run in a mile race at Santa Anita. On heavy ground, the horse seemed to stumble early on, but Woolf drove him on to second place, before pulling him up sharply at the finish. A medical examination confirmed everyone's worst fears. The horse had damaged the ] in his left foreleg, and was lame. As Pollard would later say, the horse and his most famous jockey had four good legs between them. | |||

| ==Early five-year-old season== | |||

| With Seabiscuit out of action, Smith and Howard concentrated on another of their horses, an Argentine stallion named Kayak II. Pollard and Seabiscuit recovered together at Howard's ranch, with Pollard's new wife Agnes, who had nursed him through his initial recover. Slowly, both horse and rider learned to walk again, although poverty had brought a Pollard to the edge of alcoholism. A local doctor broke and reset Pollard's leg was to aid his recovery, and slowly Red regained the confidence to sit on the horse. Wearing a brace to stiffen his atrophied leg, he began to ride Seabiscuit again, first at a walk and later at a trot and canter. Howard was delighted at their improvement, as he longed for Seabiscuit to race again, but was extremely worried about Pollard's involvement, as his leg was still fragile. | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1938, as a five-year-old, Seabiscuit's success continued. On February 19, Pollard suffered a terrible fall while racing on Fair Knightess, another of Howard's horses. With half of Pollard's chest caved in by the weight of the fallen horse, Howard had to find a new jockey. After trying three, he settled on ], an already successful rider and old friend of Pollard's. | |||

| Woolf's first race aboard Seabiscuit was the Santa Anita Handicap, "The Hundred Grander" the horse had narrowly lost the previous year. Seabiscuit was drawn on the outside, and at the start was impeded by another horse, Count Atlas, angling out. The two were locked together for the first straight, and by the time Woolf disentangled his horse, they were six lengths off the pace. Seabiscuit worked his way to the lead but lost in a ] to the fast-closing ] winner, ] (owned by Maxwell Howard, not related to Charles), who had been assigned {{convert|30|lb|kg}} less than Seabiscuit. | |||

| Over the fall and winter of 1939-40, Seabiscuit's fitness seemed to return by the day. By the end of 1939, Smith was ready to confound veterinary opinion by returning the horse to race training, with a collection of stable jockeys in the saddle. By the time of his comeback race, however, Pollard had cajoled Howard into allowing him the ride. After again scratching from a race due to the soft going, the pair finally lined up at the start of the La Jolla Handicap at Santa Anita, on ], ]. Compared to what had gone before, it was an unremarkable performance (Seabiscuit was third, bested by two lengths) but it was nevertheless an amazing comeback for both. By their third comeback race, Seabiscuit was back to winning ways, running away from the field in the San Antonio Handicap to beat his erstwhile training partner, Kayak II, by two and a half lengths. Burdened by only 124 pounds, Seabiscuit equalled the track record for a mile and 1/16. | |||

| Throughout 1937 and 1938, the media speculated about a ] between Seabiscuit and the seemingly invincible ] (sired by Man o' War, Seabiscuit's grandsire). The two horses were scheduled to meet in three stakes races, but one or the other was scratched, usually due to Seabiscuit's dislike of heavy ground. After extensive negotiation, the owners organized a match race for May 1938 at ], but Seabiscuit was scratched. | |||

| There was only one race left. A week after the San Antonio, Seabiscuit and Kayak II both took the gate for the Santa Anita Handicap, and its $121,000 prize. 78,000 paying spectators crammed the racetrack, most backing the people's champion to complete his amazing return to racing. The start was inauspicious, as a tentative Pollard found his horse blocked almost from start. Picking his way through the field, Seabiscuit briefly led. As they thundered down the back straight, Seabiscuit became trapped in third place, behind leader Whichcee and Wedding Call on the outside. Trusting in his horse's acceleration, Pollard steered a dangerous line between the leaders and burst into the lead, taking the firm ground just off the rail. As Seabiscuit showed his old surge, Wedding Call and Whichcee faltered, and Pollard drove his horse on, taking the Hundred Grander by a length and half from the fast closing Kayak II. | |||

| By June, Pollard had recovered, and on June 23, he agreed to work a young colt named Modern Youth. Spooked by something on the track, the horse broke rapidly through the stables and threw Pollard, shattering his leg and seemingly ending his career. | |||

| Pandemonium engulfed the course. Neither horse nor rider, or trainer or owner could get through the sea of well-wishers to the winner's enclosure for some time. | |||

| Howard arranged a match race for Seabiscuit against Ligaroti, a highly regarded horse owned by the ] entertainer ] and Howard's son, ], through ], in an event organized to promote Crosby's resort and ] in ]. With Woolf aboard, Seabiscuit won that race, despite persistent fouling from Ligaroti's jockey. After three more outings and with only one win, he was scheduled to go head-to-head with War Admiral in the ] in November, in ].<ref name=nack>{{cite magazine|author=Nack, William |date=November 29, 1999|title=A Match Made in Heaven|magazine=]|volume=91|number=21|page=128}}</ref> | |||

| On ], Seabiscuit's retirement from racing was officially announced. | |||

| Sent to race on the ], on October 16, 1938, Seabiscuit ran second by two lengths in the Laurel Stakes to the ] ], who set a new ] record of 1:37.00 for one mile.<ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.nytimes.com/1938/10/16/archives/wall-rides-jacola-to-twolength-triumph-over-seabiscuit-in-laurel.html | newspaper=The New York Times | title=Wall Rides Jacola to Two-Length Triumph Over Seabiscuit in Laurel Stakes; Jacola, 7-1, Breaks Laurel Mile Mark; Filly Conquers Seabiscuit in 1:37 | date=October 16, 1938 | access-date=July 23, 2018 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180723065956/https://www.nytimes.com/1938/10/16/archives/wall-rides-jacola-to-twolength-triumph-over-seabiscuit-in-laurel.html | archive-date=July 23, 2018 | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Retirement== | |||

| {{quote box | |||

| When he was retired to the Ridgewood Ranch in ], Seabiscuit, the horse nobody wanted was horse racing's all-time leading money winner. Put out to stud, Seabiscuit sired 108 foals, including two moderately successful racehorses, "Sea Swallow" and "Sea Sovereign". | |||

| | width = 280px | |||

| | quote = "George Woolf always said he never had more fun on a racehorse than he did that day in 1938 at ], when Tom Smith, the horse's trainer, lifted Woolf aboard Seabiscuit for the big match race against War Admiral."<ref name=nack/> | |||

| | source = William Nack, ''Sports Illustrated'', November 29, 1999 | |||

| }} | |||

| On November 1, 1938, Seabiscuit met ] and jockey ] in what was dubbed the "Match of the Century." The event was run over {{convert|1+3/16|mi|km}} at ]. From the grandstands to the infield, the track was jammed with fans. Trains were run from all over the country to bring fans to the race, and the estimated 40,000 at the track were joined by 40 million listening on the radio. War Admiral was the favorite (1–4 with most bookmakers) and a nearly unanimous selection of the writers and tipsters, excluding a California contingent. | |||

| At ] a life-sized bronze statue of Seabiscuit is on display. In ], he was voted into the ]. In the ] ranking of the top 100 thoroughbred champions of the 20th Century, Seabiscuit was ranked #25. | |||

| Head-to-head races favor fast starters, and War Admiral's speed from the gate was well known. Seabiscuit, on the other hand, was a pace stalker, skilled at holding with the pack before pulling ahead with late acceleration. From the scheduled walk-up start, few gave him a chance to lead War Admiral into the first turn. Smith knew these things and trained Seabiscuit to run against this type, using a starting bell and a whip to give the horse a ] burst of speed from the start. | |||

| In ] ] wrote ''Seabiscuit: An American Legend'' (ISBN 0449005615), an award-winning account of Seabiscuit's career. The book became a bestseller, and on ], ], ] released a new motion picture titled '']''. In ], a fictionalized account was made into the motion picture "The Story of Seabiscuit", starring ]. "Sea Sovereign" took the title role. Hillenbrand describes it as "inexcusably bad". | |||

| When the bell rang, Seabiscuit broke in front, led by over a length after 20 seconds, and soon crossed over to the rail position. Halfway down the backstretch, War Admiral started to cut into the lead, gradually pulling level with Seabiscuit, then slightly ahead. Following advice he had received from Pollard, Woolf had eased up on Seabiscuit, allowing his horse to see his rival, then asked for more effort. Two hundred yards from the wire, Seabiscuit pulled away again and continued to extend his lead over the closing stretch, finally winning by four lengths despite War Admiral's running his best time for the distance. | |||

| ] | |||

| As a result of his races that year, Seabiscuit was named ] for 1938, beating War Admiral by 698 points to 489 in a poll conducted by the ''Turf and Sport Digest magazine''.<ref>{{cite news |url= https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=K61aAAAAIBAJ&pg=4373,2797726&dq=seabiscuit+horse-of-the-year&hl=en |title= Seabiscuit voted best of 1938 crop |publisher= Prescott Evening Courier |date= December 12, 1938 |access-date= February 26, 2012}}</ref> Seabiscuit was the number one newsmaker of 1938.<ref name=andriani>Andriani, Lynn (January 1, 2001), "PW Talks with Laura Hillenbrand". ''Publishers Weekly''. '''248''' (1):75</ref> The only major prize that eluded him was the Santa Anita Handicap. | |||

| ==Injury and return== | |||

| Seabiscuit was injured during a race. ], who was riding him, said that he felt the horse stumble. The injury was not life-threatening, although many predicted Seabiscuit would never race again. The diagnosis was a ruptured ] in the front left leg. With Seabiscuit out of action, Smith and Howard concentrated on their horse ], an Argentine stallion. In the spring of 1939, Seabiscuit covered seven of Howard's mares, all of which had healthy foals in spring of 1940. One, Fair Knightess's colt, died as a yearling. | |||

| Seabiscuit and a still-convalescing Pollard recovered together at Howard's ranch, with the help of Pollard's new wife Agnes, who had nursed him through his initial recovery. Slowly, both horse and rider learned to walk again (Pollard joked that they "had four good legs between" them).<ref>{{cite news|author=Hillenbrand, Laura |date=July–August 1998|title=Four good legs between us|work=American Heritage|volume=49|number=4|page=38}}</ref> Poverty and his injury had brought Pollard to the edge of alcoholism. A local doctor broke and reset Pollard's leg to aid his recovery, and slowly Pollard regained the confidence to sit on a horse. Wearing a brace to stiffen his atrophied leg, he began to ride Seabiscuit again, first at a walk and later at a trot and canter. Howard was delighted at their improvement, as he longed for Seabiscuit to race again, but was extremely worried about Pollard, as his leg was still fragile. | |||

| Over the fall and winter of 1939, Seabiscuit's fitness seemed to improve by the day. By the end of the year, Smith was ready to return the horse to race training, with a collection of stable jockeys in the saddle. By the time of his comeback race, Pollard had cajoled Howard into allowing him the ride. After the horse was scratched due to soft going, the pair finally lined up at the start of the ] at ], on February 9, 1940. Seabiscuit was third, beaten by two lengths. By their third comeback race, Seabiscuit was back to his winning ways, running away from the field in the San Antonio Handicap to beat his erstwhile training partner, ], by two and a half lengths. Under {{convert|124|lb|kg}}, Seabiscuit equalled the track record for a mile and 1/16. | |||

| ] | |||

| One race was left in the season. A week after the San Antonio, Seabiscuit and Kayak II both took the gate for the Santa Anita Handicap and its $121,000 prize. 78,000 paying spectators crammed the racetrack, most backing Seabiscuit. Pollard found his horse blocked almost from the start. Picking his way through the field, Seabiscuit briefly led. As they thundered down the back straight, Seabiscuit became trapped in third place, behind leader Whichcee and Wedding Call on the outside. | |||

| Trusting in his horse's acceleration, Pollard steered between the leaders and burst into the lead, taking the firm ground just off the rail. As Seabiscuit showed his old surge, Wedding Call and Whichcee faltered, and Pollard drove his horse on, taking "The Hundred Grander" by a length and a half from the fast-closing Kayak II under jockey ]. Pandemonium engulfed the course. Neither horse and rider, nor trainer and owner, could get through the crowd of well-wishers to the winner's enclosure for some time. | |||

| ==Retirement, later life, and offspring== | |||

| On April 10, 1940, Seabiscuit's retirement from racing was officially announced. When he was retired to the ] near ], he was horse racing's all-time leading money winner. Put out to stud, Seabiscuit sired 108 foals, including two moderately successful racehorses: ] and Sea Swallow. Over 50,000 visitors went to ] to see Seabiscuit in those seven years before his death in 1947.<ref name="SFgate">{{cite news|url=http://www.sfgate.com/movies/article/In-the-1930s-San-Francisco-tycoon-Charles-Howard-2601674.php|work=SFgate|title=In the 1930s, San Francisco Tycoon Charles Howard|access-date=March 29, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140329094028/http://www.sfgate.com/movies/article/In-the-1930s-San-Francisco-tycoon-Charles-Howard-2601674.php|archive-date=March 29, 2014|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Death and interment== | |||

| Seabiscuit died of a probable heart attack<ref>{{cite web |website= IMDb |url= https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1403453/bio?ref_=nm_ov_bio_sm|title= Seabiscuit Biography}}</ref> on May 17, 1947, in ], six months before his grandsire ]. He is buried at Ridgewood Ranch in ].<ref name="SFgate"/><ref>{{cite web |website= IMDb |title= Seabiscuit (1933–1947) |url= https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1403453/?ref_=fn_al_nm_1}}</ref> | |||

| ==Legacy and honors== | |||

| ===Awards and honorable distinctions=== | |||

| *1938 ] | |||

| * In 1958, Seabiscuit was voted into the ]. | |||

| * In the '']'' magazine ] (1999), Seabiscuit was ranked 25th. War Admiral was 13th, and Seabiscuit's grandsire and War Admiral's sire, Man o' War, placed 1st. | |||

| ===Portrayals in film and television === | |||

| ====Documentaries==== | |||

| * '']'': "Seabiscuit" (April 21, 2003)<ref name="imdb.com">{{cite news|work=American Experience|title=Seabiscuit|publisher=IMDb|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0372513/|date=April 21, 2003|access-date=June 30, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170210053119/http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0372513/|archive-date=February 10, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref>) is a documentary episode that aired as Season 15, Episode 11<ref name="imdb.com"/> of the PBS ''American Experience'' series.<ref>{{cite web|title=Seabiscuit|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/seabiscuit/|work=American Experience. WGBH|publisher=PBS|access-date=November 14, 2012|date=April 21, 2003|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121019060943/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/seabiscuit/|archive-date=October 19, 2012|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| *'']'': "Seabiscuit" (November 17, 2003), Seabiscuit was featured on ESPN's SportsCentury Greatest Athletes series.<ref>{{cite news|title=ESPN SportsCentury - Seabiscuit|date=November 17, 2003|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0568356/|access-date=June 30, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170208192540/http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0568356/|archive-date=February 8, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| * ''The True Story of Seabiscuit'' (July 27, 2003) is a 45-minute made-for-TV documentary directed by ], written by ], and containing interviews and footage with ], Seabiscuit, and ], that aired on the ].<ref>{{cite book|title=The True Story of Seabiscuit|date=July 27, 2003|publisher=USA Network|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0377121/?ref_=fn_al_tt_2}}</ref> | |||

| * ''Seabiscuit: the Lost Documentary'' (1939) by Seabiscuit's owner Charles Howard. The film was directed by Manny Nathan, and written by Nathan and Hazel Merry Hawkins. It stars Martin Mason, Doc Bond, Charles Howard as himself and his wife, Marcella.<ref name="ReferenceA">{{Cite web|url=http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0384511/|title=Seabiscuit|via=www.imdb.com|access-date=July 24, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170209224731/http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0384511/|archive-date=February 9, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> It was colorized and released in 2003 by ] to coincide with interest around the movie.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> | |||

| * ''Seabiscuit: America's Legendary Racehorse'' (2003) directed and produced by ]. | |||

| ====Fiction films==== | |||

| * '']'' (1938), starring Wallace Beery and Mickey Rooney. Film producer Harry Rapf arranged a deal whereby he could film the $50,000 Hollywood Gold Cup, and actual footage of Seabiscuit running in the race was used. The field is headed by Seabiscuit for the "straight" race in the film.<ref>{{cite news|title=Seabiscuit Runs In Gold Cup Race|url=http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=DS19381104.2.81&srpos=5&e=------193-en--20--1--txt-txIN-stablemates-------1|volume=XII|issue=14|publisher=Desert Sun|date=November 4, 1938|page=9|access-date=June 5, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160630211232/http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=DS19381104.2.81&srpos=5&e=------193-en--20--1--txt-txIN-stablemates-------1|archive-date=June 30, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| * '']'' (1939) is ]' ] cartoon take on Seabiscuit's underdog story. | |||

| * '']'' (1949), starring ] in her penultimate film, is a fictionalized account featuring ] in the title role. An otherwise undistinguished film, it did include actual footage of the 1938 match race against ] and the 1940 Santa Anita Handicap. | |||

| * '']'' (2003), ]' adaptation of ]'s bestselling 2001 book, was nominated for seven ], including ] | |||

| * ''The Making of Seabiscuit'' (December 16, 2003) is a documentary short directed by Laurent Bouzereau and starring ], ], ], and ], produced by ], ], ], and ], and distributed by Universal Studios Home Video.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Making of Seabiscuit|date=December 16, 2003|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0395655/?ref_=fn_al_tt_10|publisher=Universal Studios Home Video|access-date=June 30, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160324194808/http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0395655/?ref_=fn_al_tt_10|archive-date=March 24, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Non-fiction books=== | |||

| *Track writer B.K. Beckwith wrote ''Seabiscuit: The Saga of a Great Champion'' (1940), with a foreword by ], right after Seabiscuit's Santa Anita win and at the moment of the horse's retirement.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/15740.Seabiscuit|title=Seabiscuit: The Saga of a Great Champion|date=1940|author=Beckwith, B.K. |access-date=August 29, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150808214601/http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/15740.Seabiscuit|archive-date=August 8, 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| *] wrote ''Come On, Seabiscuit!'' (1963), illustrated by ], which was recently reprinted by the ].<ref>{{cite book|url=https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/15743.Come_On_Seabiscuit_?from_search=true&search_version=service|title=Come On, Seabiscuit!|author=Moody, Ralph |date=1963|publisher=U of Nebraska Press |isbn=0-8032-8287-7|access-date=August 29, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304110027/https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/15743.Come_On_Seabiscuit_?from_search=true&search_version=service|archive-date=March 4, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| *]'s book '']'' (2001) became a bestseller,<ref>{{cite book|title=Seabiscuit: An American Legend|date=2001|isbn=0-449-00561-5|author=Hillenbrand, Laura|publisher=Random House Publishing |url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/seabiscuitameric00hill_0}}</ref> and in 2003 it was adapted for film. | |||

| ===Postage stamp=== | |||

| In 2009, after an eight-year-long grassroots effort by ] and Chuck Lustick, Seabiscuit was honored by the ] with a stamp bearing his likeness. Thousands of signatures were obtained from all over the nation, and the final approval was given by Citizens Stamp Committee member ], wife of former Vice President ].<ref>{{cite web|website=Sea Biscuit Heritage|url=http://www.seabiscuitheritage.org/press_releases_2009_05_11.html|title=As Seabiscuit Looks On, US Postal Service Gives Racing Legend Big Stamp of Approval at Historic Ridgewood Ranch, CA(New Stamped Envelope Honoring the Great Horse Goes on Sale Today)|location=Willits, CA|date=May 11, 2009|access-date=August 29, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924095740/http://www.seabiscuitheritage.org/press_releases_2009_05_11.html|archive-date=September 24, 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Statues=== | |||

| ] racetrack.<ref>Dickinson, J. W. (2006). Remembering Orlando: Tales from Elvis to Disney. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press.</ref> Lily Okuru, a ] woman who lived on the track site during its time as a ], poses with the statue in 1942.]] | |||

| * A statue of Seabiscuit (not life-sized) sits outside the main entrance of ], a shopping mall built upon the former site of the ]. Seabiscuit was stabled there briefly in 1939, while preparing for his comeback.<ref>{{cite news | url=https://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FA0E14F73F5A177A93C6AB178BD95F4D8385F9 | newspaper=The New York Times | title=Seabiscuit at Tanforan; Howard Horse to Start Training for Racing Comeback | date=October 24, 1939 | access-date=February 12, 2017 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121107145119/http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FA0E14F73F5A177A93C6AB178BD95F4D8385F9 | archive-date=November 7, 2012 | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * In the 1940s, businessman and racehorse owner W. Arnold Hanger donated a statuette of Seabiscuit to the ] library. | |||

| * In 1941, American sculptor ] cast two life-sized bronze statues of Seabiscuit hand-tooled by Frank Buchler, the German immigrant owner of Washington Ornamental Iron Company Los Angeles: one stands in "Seabiscuit Court", the walking ring at ] racetrack in Arcadia, CA; the other is outside the National Museum of Racing in Saratoga Springs, NY.<ref>{{cite news |title= Statue of Seabiscuit |url= http://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/20753 |id= (Saratoga Springs, New York, 1940) |access-date=August 19, 2017 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170820034033/http://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/20753 |archive-date= August 20, 2017 |url-status= live }}</ref> | |||

| * On June 23, 2007, a statue of Seabiscuit was unveiled at ], Seabiscuit's final resting place. | |||

| * On July 17, 2010, a life-size statue of ] and Seabiscuit was unveiled at the Remington Carriage Museum in Woolf's hometown of ]. This coincided with the 100th anniversary of Woolf's birth, though not the actual date. | |||

| <gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> | |||

| File:Seabiscuit statue - BC2016.jpg|"Seabiscuit" statue at Santa Anita in 2016, draped in a Breeders' Cup winner's blanket. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==Pedigree== | |||

| {{Pedigree | |||

| |name = Seabiscuit<ref name="Equineline">{{cite web|title=Seabiscuit|url=https://www.equineline.com/Free-5X-Pedigree.cfm/Seabiscuit?page_state=DISPLAY_REPORT&reference_number=442937®istry=T&horse_name=Seabiscuit&dam_name=Swing%20On&foaling_year=1933&include_sire_line=Y|website=Equineline|access-date=September 29, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170929140327/https://www.equineline.com/Free-5X-Pedigree.cfm/Seabiscuit?page_state=DISPLAY_REPORT&reference_number=442937®istry=T&horse_name=Seabiscuit&dam_name=Swing%20On&foaling_year=1933&include_sire_line=Y|archive-date=September 29, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |inf = | |||

| |f = ]<br />b. 1926 | |||

| |m = Swing On<br />b. 1926 | |||

| |ff = ]<br />ch. 1917 | |||

| |fm = Tea Biscuit<br /> 1912 | |||

| |mf = ]<br />ch. 1907 | |||

| |mm = Balance<br />b. 1919 | |||

| |fff = ]<br />ch. 1905 | |||

| |ffm = ]<br />b. 1910 | |||

| |fmf = ]<br />br. 1900 | |||

| |fmm = Tea's Over<br />ch. 1893<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bloodlines.net/TB/Families/Family9.htm |title=Vintner Mare - Family 9 |publisher=Bloodlines.net |access-date=August 4, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120524010130/http://www.bloodlines.net/TB/Families/Family9.htm |archive-date=May 24, 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |mff = ]<br />b. 1901 | |||

| |mfm = ]<br /> 1901 | |||

| |mmf = Rabelais<br />br. 1900 | |||

| |mmm = Balancoire<br />b. 1911 | |||

| |ffff = ] | |||

| |fffm = Fairy Gold | |||

| |ffmf = ] | |||

| |ffmm = Merry Token | |||

| |fmff = ] | |||

| |fmfm = Roquebrune | |||

| |fmmf = ] | |||

| |fmmm = Tea Rose | |||

| |mfff = ] | |||

| |mffm = Elf | |||

| |mfmf = ] | |||

| |mfmm = ] | |||

| |mmff = ] | |||

| |mmfm = Satirical | |||

| |mmmf = ] | |||

| |mmmm = Ballantrae | |||

| }} | |||

| ==Notable races won== | |||

| <!-- ALL RACES INCLUDED HERE SHOULD BE NOTABLE ENOUGH TO MERIT THEIR OWN WIKIPEDIA PAGE. ALL OTHERS WILL BE REMOVED --> | |||

| Seabiscuit ran 89 times at 16 different distances over the course of his career.<ref>Hillenbrand, Laura (May/June 2000), "Racehorse".'' American Heritage''. '''51''' (3):78</ref> | |||

| *] (1937)<ref name="durso">{{cite journal |last1=Durso |first1=Joseph |title=Horse Racing: Notebook; A Revival at Belmont For Stars Who Stayed |journal=The New York Times |date=June 17, 1994 |page=B00017 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/17/sports/horse-racing-notebook-a-revival-at-belmont-for-stars-who-stayed.html |access-date=January 7, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190108000031/https://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/17/sports/horse-racing-notebook-a-revival-at-belmont-for-stars-who-stayed.html |archive-date=January 8, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| *] (1940) | |||

| *] (1940) | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{cnote|a|The ''Saturday Evening Post'', dated April 27, 1940, reported: "By the following | |||

| March the horse failed only by inches—because | |||

| his jockey erred in looking back—to win in | |||

| his first try at the Santa Anita Handicap, richest | |||

| of all races."<ref name=SEP/>}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| {{Commons category}} | |||

| * ] (1940), ''Seabiscuit: The Saga of a Great Champion'', with drawings by Howard Brodie, ], San Francisco. | |||

| * ] (2001), ''Seabiscuit: An American Legend''. | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * . | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * , an ] documentary film by ], shown on ] | |||

| * | |||

| {{American Horse of the Year winners}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:13, 4 December 2024

American champion thoroughbred racehorse (1933–1947) For other uses, see Seabiscuit (disambiguation).| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Seabiscuit" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Seabiscuit (May 23, 1933 – May 17, 1947) was a champion thoroughbred racehorse in the United States who became the top money-winning racehorse up to the 1940s. He beat the 1937 Triple Crown winner, War Admiral, by four lengths in a two-horse special at Pimlico and was voted American Horse of the Year for 1938.

A small horse, at 15.2 hands high, Seabiscuit had an inauspicious start to his racing career, winning only a quarter of his first 40 races, but became an unlikely champion and a symbol of hope to many Americans during the Great Depression.

Seabiscuit has been the subject of numerous books and films, including Seabiscuit: the Lost Documentary (1939); the Shirley Temple film The Story of Seabiscuit (1949); a book, Seabiscuit: An American Legend (1999) by Laura Hillenbrand; and a film adaptation of Hillenbrand's book, Seabiscuit (2003), that was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. There is also a street in Indian Trail, North Carolina named after him.

Early days

Seabiscuit was foaled in Lexington, Kentucky, on May 23, 1933, from the mare Swing On and sire Hard Tack, a son of Man o' War. Seabiscuit was named for his father; "sea biscuit" is another name for hardtack, a type of cracker eaten by sailors.

The bay colt grew up on Claiborne Farm in Paris, Kentucky, where he was trained. He was undersized, knobby-kneed, and given to sleeping and eating for long periods.

Initially, Seabiscuit was owned by the powerful Wheatley Stable and trained by "Sunny Jim" Fitzsimmons, who had taken Gallant Fox to the United States Triple Crown of Thoroughbred Racing. Fitzsimmons saw some potential in Seabiscuit but felt the horse was too lazy. Fitzsimmons devoted most of his time to training Omaha, who won the 1935 Triple Crown.

Seabiscuit was relegated to a heavy schedule of smaller races. He failed to win any of his first 17 races, usually finishing back in the field. After that, Fitzsimmons did not spend much time on him, and the horse was sometimes the butt of stable jokes. However, Seabiscuit began to gain attention after winning two races at Narragansett Park and setting a new track record in the second—Claiming Stakes race.

As a two-year-old, Seabiscuit raced 35 times (a heavy racing schedule), coming in first five times and finishing second seven times. These included three claiming races, in which he could have been purchased for $2,500, but he had no takers.

While Seabiscuit had not lived up to his racing potential, he was not the poor performer Fitzsimmons had taken him for. His last two wins as a two-year-old came in minor stakes races. The next season started with a similar pattern. The colt ran 12 times in less than four months, winning four times. One of those races was a cheap allowance race on the "sweltering afternoon of June 29," 1936, at Suffolk Downs. That was where trainer Tom Smith first laid eyes on Seabiscuit. His owners sold the horse to automobile entrepreneur Charles S. Howard for $8,000 at Saratoga, in August.

1936/1937: The beginning of success

Howard assigned Seabiscuit to a new trainer, Tom Smith, who, with his unorthodox training methods, gradually brought Seabiscuit out of his lethargy. Smith paired the horse with Canadian jockey Red Pollard (1909–1981), who had experience racing in the West and in Mexico. On August 22, 1936, they raced Seabiscuit for the first time. Improvements came quickly, and in their remaining eight races in the East, Seabiscuit and Pollard won several times, including the Detroit Governor's Handicap (worth $5,600) and the Scarsdale Handicap ($7,300) at Empire City Race Track in Yonkers, New York.

In early November 1936, Howard and Smith shipped the horse to California by rail. His last two races of the year were at Bay Meadows racetrack in San Mateo, California. The first was the $2,700 Bay Bridge Handicap, run over one-mile (1.6 km). Despite starting badly and carrying the top weight of 116 pounds (53 kg), Seabiscuit won by five lengths. At the World's Fair Handicap (Bay Meadows' most prestigious stakes race), Seabiscuit led throughout.

In 1937, the Santa Anita Handicap, California's most prestigious race, was worth over $125,000 ($2.8 million in 2010) to the winner; it was known colloquially as "The Hundred Grander." In his first warm-up race at Santa Anita Park, Seabiscuit won easily. In his second race of 1937, the San Antonio Handicap, he suffered a setback after he was bumped at the start and then pushed wide; Seabiscuit came in fifth, losing to Rosemont.

The two met again in the Santa Anita Handicap a week later, where Rosemont won by a nose. The defeat was devastating to Smith and Howard and was widely attributed in the press to a jockey error. Pollard, who had not seen Rosemont over his shoulder until too late, was blind in one eye due to an accident during a training ride, a fact he had hidden throughout his career. A week after this defeat Seabiscuit won the San Juan Capistrano Handicap by seven lengths in track record time of 1:484⁄5 for the 1+1⁄8 mile event.

Seabiscuit was rapidly becoming a favorite among California racing fans, and his fame spread as he won his next three races. With his successes, Howard decided to ship the horse east for its more prestigious racing circuit.

Seabiscuit's run of victories continued. Between June 26 and August 7, he ran five times, each time in a stakes race, and each time he won under steadily increasing handicap weights (imposts) of up to 130 pounds (59 kg). For the third time, Seabiscuit faced off against Rosemont again, this time beating him by seven lengths. On September 11, Smith accepted an impost of 132 pounds (60 kg) for the Narragansett Special at Narragansett Park. On race day, the ground was slow and heavy, and unsuited to "the Biscuit", carrying the heaviest burden of his career. Smith wanted to scratch, but Howard overruled him. Never in the running, Seabiscuit finished third. His winning streak was snapped, but the season was not over; Seabiscuit won his next three races (one a dead heat) before finishing the year with a second-place at Pimlico.

In 1937, Seabiscuit won 11 of his 15 races and was the year's leading money winner in the United States. However, War Admiral, having won the Triple Crown that season, was voted the most prestigious honor, the American Horse of the Year Award.

Early five-year-old season

In 1938, as a five-year-old, Seabiscuit's success continued. On February 19, Pollard suffered a terrible fall while racing on Fair Knightess, another of Howard's horses. With half of Pollard's chest caved in by the weight of the fallen horse, Howard had to find a new jockey. After trying three, he settled on George Woolf, an already successful rider and old friend of Pollard's.

Woolf's first race aboard Seabiscuit was the Santa Anita Handicap, "The Hundred Grander" the horse had narrowly lost the previous year. Seabiscuit was drawn on the outside, and at the start was impeded by another horse, Count Atlas, angling out. The two were locked together for the first straight, and by the time Woolf disentangled his horse, they were six lengths off the pace. Seabiscuit worked his way to the lead but lost in a photo finish to the fast-closing Santa Anita Derby winner, Stagehand (owned by Maxwell Howard, not related to Charles), who had been assigned 30 pounds (14 kg) less than Seabiscuit.

Throughout 1937 and 1938, the media speculated about a match race between Seabiscuit and the seemingly invincible War Admiral (sired by Man o' War, Seabiscuit's grandsire). The two horses were scheduled to meet in three stakes races, but one or the other was scratched, usually due to Seabiscuit's dislike of heavy ground. After extensive negotiation, the owners organized a match race for May 1938 at Belmont, but Seabiscuit was scratched.

By June, Pollard had recovered, and on June 23, he agreed to work a young colt named Modern Youth. Spooked by something on the track, the horse broke rapidly through the stables and threw Pollard, shattering his leg and seemingly ending his career.

Howard arranged a match race for Seabiscuit against Ligaroti, a highly regarded horse owned by the Hollywood entertainer Bing Crosby and Howard's son, Lindsay, through Binglin Stable, in an event organized to promote Crosby's resort and Del Mar Racetrack in Del Mar, California. With Woolf aboard, Seabiscuit won that race, despite persistent fouling from Ligaroti's jockey. After three more outings and with only one win, he was scheduled to go head-to-head with War Admiral in the Pimlico Special in November, in Baltimore, Maryland.

Sent to race on the East Coast, on October 16, 1938, Seabiscuit ran second by two lengths in the Laurel Stakes to the filly Jacola, who set a new Laurel Park Racecourse record of 1:37.00 for one mile.

William Nack, Sports Illustrated, November 29, 1999"George Woolf always said he never had more fun on a racehorse than he did that day in 1938 at Pimlico, when Tom Smith, the horse's trainer, lifted Woolf aboard Seabiscuit for the big match race against War Admiral."

On November 1, 1938, Seabiscuit met War Admiral and jockey Charles Kurtsinger in what was dubbed the "Match of the Century." The event was run over 1+3⁄16 miles (1.9 km) at Pimlico Race Course. From the grandstands to the infield, the track was jammed with fans. Trains were run from all over the country to bring fans to the race, and the estimated 40,000 at the track were joined by 40 million listening on the radio. War Admiral was the favorite (1–4 with most bookmakers) and a nearly unanimous selection of the writers and tipsters, excluding a California contingent.

Head-to-head races favor fast starters, and War Admiral's speed from the gate was well known. Seabiscuit, on the other hand, was a pace stalker, skilled at holding with the pack before pulling ahead with late acceleration. From the scheduled walk-up start, few gave him a chance to lead War Admiral into the first turn. Smith knew these things and trained Seabiscuit to run against this type, using a starting bell and a whip to give the horse a Pavlovian burst of speed from the start.

When the bell rang, Seabiscuit broke in front, led by over a length after 20 seconds, and soon crossed over to the rail position. Halfway down the backstretch, War Admiral started to cut into the lead, gradually pulling level with Seabiscuit, then slightly ahead. Following advice he had received from Pollard, Woolf had eased up on Seabiscuit, allowing his horse to see his rival, then asked for more effort. Two hundred yards from the wire, Seabiscuit pulled away again and continued to extend his lead over the closing stretch, finally winning by four lengths despite War Admiral's running his best time for the distance.

As a result of his races that year, Seabiscuit was named American Horse of the Year for 1938, beating War Admiral by 698 points to 489 in a poll conducted by the Turf and Sport Digest magazine. Seabiscuit was the number one newsmaker of 1938. The only major prize that eluded him was the Santa Anita Handicap.

Injury and return

Seabiscuit was injured during a race. Woolf, who was riding him, said that he felt the horse stumble. The injury was not life-threatening, although many predicted Seabiscuit would never race again. The diagnosis was a ruptured suspensory ligament in the front left leg. With Seabiscuit out of action, Smith and Howard concentrated on their horse Kayak II, an Argentine stallion. In the spring of 1939, Seabiscuit covered seven of Howard's mares, all of which had healthy foals in spring of 1940. One, Fair Knightess's colt, died as a yearling.

Seabiscuit and a still-convalescing Pollard recovered together at Howard's ranch, with the help of Pollard's new wife Agnes, who had nursed him through his initial recovery. Slowly, both horse and rider learned to walk again (Pollard joked that they "had four good legs between" them). Poverty and his injury had brought Pollard to the edge of alcoholism. A local doctor broke and reset Pollard's leg to aid his recovery, and slowly Pollard regained the confidence to sit on a horse. Wearing a brace to stiffen his atrophied leg, he began to ride Seabiscuit again, first at a walk and later at a trot and canter. Howard was delighted at their improvement, as he longed for Seabiscuit to race again, but was extremely worried about Pollard, as his leg was still fragile.

Over the fall and winter of 1939, Seabiscuit's fitness seemed to improve by the day. By the end of the year, Smith was ready to return the horse to race training, with a collection of stable jockeys in the saddle. By the time of his comeback race, Pollard had cajoled Howard into allowing him the ride. After the horse was scratched due to soft going, the pair finally lined up at the start of the La Jolla Handicap at Santa Anita, on February 9, 1940. Seabiscuit was third, beaten by two lengths. By their third comeback race, Seabiscuit was back to his winning ways, running away from the field in the San Antonio Handicap to beat his erstwhile training partner, Kayak II, by two and a half lengths. Under 124 pounds (56 kg), Seabiscuit equalled the track record for a mile and 1/16.

One race was left in the season. A week after the San Antonio, Seabiscuit and Kayak II both took the gate for the Santa Anita Handicap and its $121,000 prize. 78,000 paying spectators crammed the racetrack, most backing Seabiscuit. Pollard found his horse blocked almost from the start. Picking his way through the field, Seabiscuit briefly led. As they thundered down the back straight, Seabiscuit became trapped in third place, behind leader Whichcee and Wedding Call on the outside.

Trusting in his horse's acceleration, Pollard steered between the leaders and burst into the lead, taking the firm ground just off the rail. As Seabiscuit showed his old surge, Wedding Call and Whichcee faltered, and Pollard drove his horse on, taking "The Hundred Grander" by a length and a half from the fast-closing Kayak II under jockey Leon Haas. Pandemonium engulfed the course. Neither horse and rider, nor trainer and owner, could get through the crowd of well-wishers to the winner's enclosure for some time.

Retirement, later life, and offspring

On April 10, 1940, Seabiscuit's retirement from racing was officially announced. When he was retired to the Ridgewood Ranch near Willits, California, he was horse racing's all-time leading money winner. Put out to stud, Seabiscuit sired 108 foals, including two moderately successful racehorses: Sea Sovereign and Sea Swallow. Over 50,000 visitors went to Ridgewood Ranch to see Seabiscuit in those seven years before his death in 1947.

Death and interment

Seabiscuit died of a probable heart attack on May 17, 1947, in Willits, California, six months before his grandsire Man o' War. He is buried at Ridgewood Ranch in Mendocino County, California.

Legacy and honors

Awards and honorable distinctions

- 1938 American Horse of the Year

- In 1958, Seabiscuit was voted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame.

- In the Blood-Horse magazine List of the Top 100 U.S. Racehorses of the 20th Century (1999), Seabiscuit was ranked 25th. War Admiral was 13th, and Seabiscuit's grandsire and War Admiral's sire, Man o' War, placed 1st.

Portrayals in film and television

Documentaries

- American Experience: "Seabiscuit" (April 21, 2003)) is a documentary episode that aired as Season 15, Episode 11 of the PBS American Experience series.

- ESPN SportsCentury: "Seabiscuit" (November 17, 2003), Seabiscuit was featured on ESPN's SportsCentury Greatest Athletes series.

- The True Story of Seabiscuit (July 27, 2003) is a 45-minute made-for-TV documentary directed by Craig Haffner, written by Martin Gillam, and containing interviews and footage with William H. Macy, Seabiscuit, and Tobey Maguire, that aired on the USA Network.

- Seabiscuit: the Lost Documentary (1939) by Seabiscuit's owner Charles Howard. The film was directed by Manny Nathan, and written by Nathan and Hazel Merry Hawkins. It stars Martin Mason, Doc Bond, Charles Howard as himself and his wife, Marcella. It was colorized and released in 2003 by Legend Films to coincide with interest around the movie.

- Seabiscuit: America's Legendary Racehorse (2003) directed and produced by Nick Krantz.

Fiction films

- Stablemates (1938), starring Wallace Beery and Mickey Rooney. Film producer Harry Rapf arranged a deal whereby he could film the $50,000 Hollywood Gold Cup, and actual footage of Seabiscuit running in the race was used. The field is headed by Seabiscuit for the "straight" race in the film.

- Porky and Teabiscuit (1939) is Warner Bros.' Porky Pig cartoon take on Seabiscuit's underdog story.

- The Story of Seabiscuit (1949), starring Shirley Temple in her penultimate film, is a fictionalized account featuring Sea Sovereign in the title role. An otherwise undistinguished film, it did include actual footage of the 1938 match race against War Admiral and the 1940 Santa Anita Handicap.

- Seabiscuit (2003), Universal Studios' adaptation of Laura Hillenbrand's bestselling 2001 book, was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture

- The Making of Seabiscuit (December 16, 2003) is a documentary short directed by Laurent Bouzereau and starring Tobey Maguire, Jeff Bridges, Chris Cooper, and William Goldenberg, produced by DreamWorks SKG, Herzog Productions, Spyglass Entertainment, and Universal Studios, and distributed by Universal Studios Home Video.

Non-fiction books

- Track writer B.K. Beckwith wrote Seabiscuit: The Saga of a Great Champion (1940), with a foreword by Grantland Rice, right after Seabiscuit's Santa Anita win and at the moment of the horse's retirement.

- Ralph Moody wrote Come On, Seabiscuit! (1963), illustrated by Robert Riger, which was recently reprinted by the University of Nebraska Press.

- Laura Hillenbrand's book Seabiscuit: An American Legend (2001) became a bestseller, and in 2003 it was adapted for film.

Postage stamp

In 2009, after an eight-year-long grassroots effort by Maggie Van Ostrand and Chuck Lustick, Seabiscuit was honored by the United States Postal Service with a stamp bearing his likeness. Thousands of signatures were obtained from all over the nation, and the final approval was given by Citizens Stamp Committee member Joan Mondale, wife of former Vice President Walter Mondale.

Statues

- A statue of Seabiscuit (not life-sized) sits outside the main entrance of The Shops at Tanforan, a shopping mall built upon the former site of the Tanforan Racetrack. Seabiscuit was stabled there briefly in 1939, while preparing for his comeback.

- In the 1940s, businessman and racehorse owner W. Arnold Hanger donated a statuette of Seabiscuit to the Keeneland library.

- In 1941, American sculptor Jame Hughlette "Tex" Wheeler cast two life-sized bronze statues of Seabiscuit hand-tooled by Frank Buchler, the German immigrant owner of Washington Ornamental Iron Company Los Angeles: one stands in "Seabiscuit Court", the walking ring at Santa Anita Park racetrack in Arcadia, CA; the other is outside the National Museum of Racing in Saratoga Springs, NY.

- On June 23, 2007, a statue of Seabiscuit was unveiled at Ridgewood Ranch, Seabiscuit's final resting place.

- On July 17, 2010, a life-size statue of George Woolf and Seabiscuit was unveiled at the Remington Carriage Museum in Woolf's hometown of Cardston, Alberta. This coincided with the 100th anniversary of Woolf's birth, though not the actual date.

Pedigree

| Sire Hard Tack b. 1926 |

Man o' War ch. 1917 |

Fair Play ch. 1905 |

Hastings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fairy Gold | |||

| Mahubah b. 1910 |

Rock Sand | ||

| Merry Token | |||

| Tea Biscuit 1912 |

Rock Sand br. 1900 |

Sainfoin | |

| Roquebrune | |||

| Tea's Over ch. 1893 |

Hanover | ||

| Tea Rose | |||

| Dam Swing On b. 1926 |

Whisk Broom II ch. 1907 |

Broomstick b. 1901 |

Ben Brush |

| Elf | |||

| Audience 1901 |

Sir Dixon | ||

| Sallie McClelland | |||

| Balance b. 1919 |

Rabelais br. 1900 |

St. Simon | |

| Satirical | |||

| Balancoire b. 1911 |

Meddler | ||

| Ballantrae |

Notable races won

Seabiscuit ran 89 times at 16 different distances over the course of his career.

- Brooklyn Handicap (1937)

- San Antonio Handicap (1940)

- Santa Anita Handicap (1940)

See also

Notes

a: The Saturday Evening Post, dated April 27, 1940, reported: "By the following

March the horse failed only by inches—because

his jockey erred in looking back—to win in

his first try at the Santa Anita Handicap, richest

of all races."

References

- "USATODAY.com". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 24, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- "Seabiscuit (1933–1947)". IMDb.

- "Seabiscuit Biography". IMDb.

- ^ "Champion". Saturday Evening Post. Vol. 212, no. 44. April 27, 1940. p. 28.

- Stradley, Linda (2004). "H (see "hardtack")". Linda's Culinary Dictionary. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Hillenbrand, Laura (2001). Seabiscuit: An American Legend. Random House Publishing. ISBN 978-0-449-00561-3.

- Lowry, Paul (March 7, 1937). "Seabiscuit Triumphs By Seven Lengths (1937 San Juan Capistrano Handicap - race 6: held 6 March 1937)". Los Angeles Times. pp. 25, 26. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Nack, William (November 29, 1999). "A Match Made in Heaven". Sports Illustrated. Vol. 91, no. 21. p. 128.

- "Wall Rides Jacola to Two-Length Triumph Over Seabiscuit in Laurel Stakes; Jacola, 7-1, Breaks Laurel Mile Mark; Filly Conquers Seabiscuit in 1:37". The New York Times. October 16, 1938. Archived from the original on July 23, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- "Seabiscuit voted best of 1938 crop". Prescott Evening Courier. December 12, 1938. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- Andriani, Lynn (January 1, 2001), "PW Talks with Laura Hillenbrand". Publishers Weekly. 248 (1):75

- Hillenbrand, Laura (July–August 1998). "Four good legs between us". American Heritage. Vol. 49, no. 4. p. 38.

- ^ "In the 1930s, San Francisco Tycoon Charles Howard". SFgate. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- "Seabiscuit Biography". IMDb.

- "Seabiscuit (1933–1947)". IMDb.

- ^ "Seabiscuit". American Experience. IMDb. April 21, 2003. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- "Seabiscuit". American Experience. WGBH. PBS. April 21, 2003. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

- "ESPN SportsCentury - Seabiscuit". November 17, 2003. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- The True Story of Seabiscuit. USA Network. July 27, 2003.

- ^ "Seabiscuit". Archived from the original on February 9, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2017 – via www.imdb.com.

- "Seabiscuit Runs In Gold Cup Race". Vol. XII, no. 14. Desert Sun. November 4, 1938. p. 9. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- The Making of Seabiscuit. Universal Studios Home Video. December 16, 2003. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- Beckwith, B.K. (1940). Seabiscuit: The Saga of a Great Champion. Archived from the original on August 8, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- Moody, Ralph (1963). Come On, Seabiscuit!. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8287-7. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- Hillenbrand, Laura (2001). Seabiscuit: An American Legend. Random House Publishing. ISBN 0-449-00561-5.

- "As Seabiscuit Looks On, US Postal Service Gives Racing Legend Big Stamp of Approval at Historic Ridgewood Ranch, CA(New Stamped Envelope Honoring the Great Horse Goes on Sale Today)". Sea Biscuit Heritage. Willits, CA. May 11, 2009. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- Dickinson, J. W. (2006). Remembering Orlando: Tales from Elvis to Disney. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press.

- "Seabiscuit at Tanforan; Howard Horse to Start Training for Racing Comeback". The New York Times. October 24, 1939. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- "Statue of Seabiscuit". (Saratoga Springs, New York, 1940). Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- "Seabiscuit". Equineline. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- "Vintner Mare - Family 9". Bloodlines.net. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- Hillenbrand, Laura (May/June 2000), "Racehorse". American Heritage. 51 (3):78

- Durso, Joseph (June 17, 1994). "Horse Racing: Notebook; A Revival at Belmont For Stars Who Stayed". The New York Times: B00017. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

Further reading

- Beckwith, B.K. (1940), Seabiscuit: The Saga of a Great Champion, with drawings by Howard Brodie, Wilfred Crowell, Inc., San Francisco.

- Hillenbrand, Laura (2001), Seabiscuit: An American Legend.

External links

- Newsreel film of Seabiscuit v War Admiral

- Seabiscuit Heritage Foundation. Livingston, Tracy (2005), retrieved June 26, 2005.

- "Seabiscuit", Snopes.com (2005), retrieved June 18, 2015.

- Seabiscuit, 1938 Horse of the Year

- Seabiscuit, Hollywood film, 2003

- The Story of Seabiscuit, Hollywood film, 1949

- The Biscuit's pedigree

- Quick online racing game, inc. The Biscuit

- Article about the Seabiscuit-War Admiral match race

- Youtube of the 1938 match race

- Seabiscuit, an American Experience documentary film by Stephen Ives, shown on PBS

- www.janiburon.com, website of author of Seabiscuit books

- 1933 racehorse births

- 1947 racehorse deaths

- Racehorses bred in Kentucky

- Racehorses trained in the United States

- Horse racing track record setters

- American Thoroughbred Horse of the Year

- United States Thoroughbred Racing Hall of Fame inductees

- Horse monuments

- Thoroughbred family 5-j

- Godolphin Arabian sire line