| Revision as of 21:31, 20 January 2013 editSom999 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,215 edits Reverted 12 edits by Cavann (talk): Referenced content removed without citing any reason. (TW)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:56, 27 December 2024 edit undoBeshogur (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users33,256 edits Undid revision 1265641477 by Persian Lad (talk)Tag: Undo | ||

| (939 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|DNA analyses of the ethnic Turks from Turkey}} | |||

| {{Synthesis|date=May 2010}} | |||

| {{primary sources|date=November 2018}} | |||

| {{Further|Genetic history of Europe|Archaeogenetics of the Near East}} | |||

| In ] the question has been debated whether the modern ] is significantly related to other ], or whether they are rather derived from indigenous populations of ] which were ] during the Middle Ages. The contribution of the Central Asian genetics to the modern Turkish people has been debated and become the subject of several studies. As a result, several studies have concluded that the historical (pre-Islamic) and indigenous Anatolian groups are the primary source of the present-day Turkish population,<ref name=antigens57></ref><ref name=Yardumian_et_al>Yardumian, A., & Schurr, T. G. (2011). Who Are the Anatolian Turks?. Anthropology & Archeology Of Eurasia, 50(1), 6-42. doi:10.2753/AAE1061-1959500101</ref><ref name="Hodoglugil_et_al2">Hodoğlugil, U., & Mahley, R. W. (2012). Turkish Population Structure and Genetic Ancestry Reveal Relatedness among Eurasian Populations. Annals Of Human Genetics, 76(2), 128-141. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x </ref><ref name=eurostudy></ref><ref name=humangenetics112></ref><ref name=stanford></ref><ref name=euroasia></ref> in addition to in addition to neighboring peoples,<ref name="Hodoglugil_et_al2"/> such as ],<ref></ref> and central Asian ].<ref name=Hodoglugil_et_al2/> | |||

| ] research has been conducted on the ancestry of the modern ] (not to be confused with ]) in ]. Such studies are relevant for the demographic history of the population as well as health reasons, such as population specific diseases.<ref name="Alkan" /> Some studies have sought to determine the relative contributions of the ] of ], from where the ] began migrating to ] after the ] in 1071, which led to the establishment of the ] in the late 11th century, and prior populations in the area who were ] during the Seljuk and the ] periods. | |||

| ==Central Asian and Uralic connection== | |||

| ] | |||

| The question to what extent a gene flow from ] to ] has contributed to the current gene pool of the Turkish people, and what the role is in this of the 11th century invasion by ], has been the subject of several studies. A factor that makes it difficult to give reliable estimates, is the problem of distinguishing between the effects of different migratory episodes. Recent genetic research indicates that some the ] originated from Central Asia and therefore are possibly related with ].<ref name=touchette>Touchette, Nancy. "", ''Genome News Network.'': "Skeletons from the most recent graves also contained DNA sequences similar to those in people from present-day Turkey, supporting the idea that some of the Turkish people originated in Mongolia. ... This supports other studies indicating that ] tribes originated at least in part in Mongolia at the end of the Xiongnu period."</ref> A majority (89%) of the Xiongnu sequences can be classified as belonging to an ] ] and nearly 11% belong to ] ]. This finding indicates that the contacts between European and Asian populations were anterior to the Xiongnu culture, and it confirms results reported for two samples from an early 3rd century B.C. ]-] population.<ref name=Clisson2002>{{cite journal | |||

| | author = Clisson, I.; Keyser, C.; Francfort, H. P.; Crubezy, E.; Samashev, Z.; Ludes, B. | |||

| | year = 2002 | |||

| | journal = International Journal of Legal Medicine | |||

| | volume = 116 | |||

| | issue = 5 | |||

| | pages = 304–308 | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/s00414-002-0295-x | |||

| | title = Genetic analysis of human remains from a double inhumation in a frozen kurgan in Kazakhstan | |||

| | pmid = 12376844 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Turkish genomic variation, along with several other ] populations, looks most similar to genomic variation of ]an populations such as southern Italians.<ref name="Taskent_et_al_2017">{{cite journal | vauthors = Taskent RO, Gokcumen O | title = The Multiple Histories of Western Asia: Perspectives from Ancient and Modern Genomes | journal = Human Biology | volume = 89 | issue = 2 | pages = 107–117 | date = April 2017 | pmid = 29299965 | doi = 10.13110/humanbiology.89.2.01 | s2cid = 6871226 | url = https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29299965 }}</ref> Western Asian genomes, including Turkish ones, have been greatly influenced by early agricultural populations in the area; later population movements, such as those of Turkic speakers, also contributed.<ref name="Taskent_et_al_2017"/> However, the genetic variation of various populations in Central Asia "has been poorly characterized"; Western Asian populations may also be "closely related to populations in the east".<ref name="Taskent_et_al_2017"/> | |||

| Some of these ancient specimens may be of a possible Turkic origin .<ref name=touchette/><ref name=Richards2000>{{cite journal | |||

| | author = Martin Richards, Vincent Macaulay, Eileen Hickey, Emilce Vega, Bryan Sykes, Valentina Guida, Chiara Rengo, Daniele Sellitto, Fulvio Cruciani, Toomas Kivisild, Richard Villems, Mark Thomas, Serge Rychkov, Oksana Rychkov, Yuri Rychkov, Mukaddes Gölge, Dimitar Dimitrov, Emmeline Hill11, Dan Bradley, Valentino Romano, Francesco Calì, Giuseppe Vona, Andrew Demaine, Surinder Papiha, Costas Triantaphyllidis, Gheorghe Stefanescu, Jiři Hatina, Michele Belledi, Anna Di Rienzo, Andrea Novelletto, Ariella Oppenheim, Søren Nørby, Nadia Al-Zaheri, Silvana Santachiara-Benerecetti, Rosaria Scozzari, Antonio Torroni, and Hans-Jürgen Bandelt | |||

| | title = Tracing European founder lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA pool | |||

| | journal = American Journal of Human Genetics | |||

| | year = 2000 | |||

| | month = November | |||

| | volume = 67 | |||

| | issue = 5 | |||

| | pages = 1251–1276 | |||

| | url = http://www.stats.gla.ac.uk/~vincent/founder2000/ | |||

| | doi = 10.1016/S0002-9297(07)62954-1 | |||

| | pmid = 11032788 | |||

| | pmc = 1288566 | |||

| }}</ref> According to another archeological and genetic study in 2010, the paternal Y-chromosome R1a, which is considered as an Indo-European marker, was found in three skeletons in 2000-year-old elite ] cemetery in Northeast Asia, which supports Kurgan expansion hypothesis for the Indo-European expansion from the Volga steppe region.<ref>Kim et al. A western Eurasian male is found in 2000-year-old elite Xiongnu cemetery in Northeast Mongolia, Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010 Jul;142(3):429-40, quoted pg.2 "The Kurgan expansion hypothesis explains the IndoEuropean expansion from the Volga steppe region (Gimbutas, 1973; Mallory, 1989).The paternal Y-chromosome single nucleotide polymorphisms (Y-SNP) R1a1 is considered as an Indo-European marker, supporting Kurgan expansion hypothesis (Zerjal et al., 1999; Kharkov et al., 2004; Haak et al., 2008). Recent finding of R1a1 in the Krasnoyarsk area east of Siberia marks the eastward expansion of the early Indo-Europeans (Keyser-Tracqui et al., 2009). R1a1 was not found in Scytho-Siberian skeletons from the Seby¨stei site of Altai Republic or in Xiongnu skeletons from Egyin Gol of Mongolia (KeyserTracqui et al., 2009)." quoted p.10: ", paternal, maternal, and biparental genetic analyses were done on three Xiongnu tombs of Northeast Mongolia 2,000 years ago. We showed for the first time that an Indo-European with paternal R1a1 and maternal U2e1 was present in the Xiongnu Empire of ancient Mongolia"</ref> As the R1a was found in Xiongnu people<ref>Kim et al. A western Eurasian male is found in 2000-year-old elite Xiongnu cemetery in Northeast Mongolia, Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010 Jul;142(3):429-40</ref> and the present-day people of Central Asia<ref>Xue et al. Male Demography in East Asia: A North–South Contrast in Human Population Expansion Times, Genetics. 2006April; 172(4): 2431–2439. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.054270</ref> A majority (89%) of the Xiongnu mtDNA sequences can be classified as belonging to ] ]s, and nearly 11% belong to ]an ]s. This finding indicates that the contacts between European and Asian populations were anterior to the Xiongnu culture Well-preserved bodies in Xiongnu and pre-Xiongnu tombs in the Mongolian Republic and southern Siberia show both 'Mongoloid' and 'Caucasian' features<ref>The Great Empires of the Ancient World - Thomas Harrison - 2009 - 288 page</ref> but are predominantly Mongoloid with some admixture of European physical stock, nonetheless the Xiongnu shared many cultural traits with their Indo-European neighbors, such as horse racing, sword worship.<ref>Ancient bronzes, ceramics, and seals: the Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection of ancient Near Eastern, central Asiatic, and European art, gift of the Ahmanson Foundation </ref> Analysis of skeletal remains from sites attributed to the Xiongnu provides an identification of dolichocephalic Mongoloid, ethnically distinct from neighboring populations in present-day Mongolia.<ref>Fu ren da xue (Beijing, China), S.V.D. Research Institute, Society of the Divine Word - 2003 </ref> Russian and Chinese anthropological and craniofacial studies show that the Xiongnu were physically very heterogenous, with six different population clusters showing different degrees of Mongoloid and Caucasoid physical traits. These clusters point to significant cross-regional migrations (both east to west and west to east) that likely started in the Neolithic period and continued to the medieval/Mongolian period.<ref>Tumen D., "Anthropology of Archaeological Populations from Northeast Asia </ref> | |||

| Multiple studies have found similarities or common ancestry between Turkish people and present-day or historic populations in the ], ] and the ].<ref name="antigens57">{{cite journal | vauthors = Arnaiz-Villena A, Karin M, Bendikuze N, Gomez-Casado E, Moscoso J, Silvera C, Oguz FS, Sarper Diler A, De Pacho A, Allende L, Guillen J, Martinez Laso J | display-authors = 6 | title = HLA alleles and haplotypes in the Turkish population: relatedness to Kurds, Armenians and other Mediterraneans | journal = Tissue Antigens | volume = 57 | issue = 4 | pages = 308–17 | date = April 2001 | pmid = 11380939 | doi = 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057004308.x }}</ref><ref name="cinnioglu 2004" /><ref name="eurostudy">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rosser ZH, Zerjal T, Hurles ME, Adojaan M, Alavantic D, Amorim A, Amos W, Armenteros M, Arroyo E, Barbujani G, Beckman G, Beckman L, Bertranpetit J, Bosch E, Bradley DG, Brede G, Cooper G, Côrte-Real HB, de Knijff P, Decorte R, Dubrova YE, Evgrafov O, Gilissen A, Glisic S, Gölge M, Hill EW, Jeziorowska A, Kalaydjieva L, Kayser M, Kivisild T, Kravchenko SA, Krumina A, Kucinskas V, Lavinha J, Livshits LA, Malaspina P, Maria S, McElreavey K, Meitinger TA, Mikelsaar AV, Mitchell RJ, Nafa K, Nicholson J, Nørby S, Pandya A, Parik J, Patsalis PC, Pereira L, Peterlin B, Pielberg G, Prata MJ, Previderé C, Roewer L, Rootsi S, Rubinsztein DC, Saillard J, Santos FR, Stefanescu G, Sykes BC, Tolun A, Villems R, Tyler-Smith C, Jobling MA | display-authors = 6 | title = Y-chromosomal diversity in Europe is clinal and influenced primarily by geography, rather than by language | journal = American Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 67 | issue = 6 | pages = 1526–43 | date = December 2000 | pmid = 11078479 | pmc = 1287948 | doi = 10.1086/316890 }}</ref><ref name="euroasia">{{cite journal | vauthors = Wells RS, Yuldasheva N, Ruzibakiev R, Underhill PA, Evseeva I, Blue-Smith J, Jin L, Su B, Pitchappan R, Shanmugalakshmi S, Balakrishnan K, Read M, Pearson NM, Zerjal T, Webster MT, Zholoshvili I, Jamarjashvili E, Gambarov S, Nikbin B, Dostiev A, Aknazarov O, Zalloua P, Tsoy I, Kitaev M, Mirrakhimov M, Chariev A, Bodmer WF | display-authors = 6 | title = The Eurasian heartland: a continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 98 | issue = 18 | pages = 10244–9 | date = August 2001 | pmid = 11526236 | pmc = 56946 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.171305098 | bibcode = 2001PNAS...9810244W | jstor = 3056514 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="Yardumian_et_al">{{cite journal |doi=10.2753/AAE1061-1959500101|title=Who Are the Anatolian Turks?|journal=Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia|volume=50|issue=1|pages=6–42|year=2011| vauthors = Schurr TG, Yardumian A |s2cid=142580885}}</ref><ref name="Pakstis_et_al_2019">{{cite journal | vauthors = Pakstis AJ, Gurkan C, Dogan M, Balkaya HE, Dogan S, Neophytou PI, Cherni L, Boussetta S, Khodjet-El-Khil H, Ben Ammar ElGaaied A, Salvo NM, Janssen K, Olsen GH, Hadi S, Almohammed EK, Pereira V, Truelsen DM, Bulbul O, Soundararajan U, Rajeevan H, Kidd JR, Kidd KK | display-authors = 6 | title = Genetic relationships of European, Mediterranean, and SW Asian populations using a panel of 55 AISNPs | journal = European Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 27 | issue = 12 | pages = 1885–1893 | date = December 2019 | pmid = 31285530 | pmc = 6871633 | doi = 10.1038/s41431-019-0466-6 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="Banfai_et_al_2019">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bánfai Z, Melegh BI, Sümegi K, Hadzsiev K, Miseta A, Kásler M, Melegh B | title = Revealing the Genetic Impact of the Ottoman Occupation on Ethnic Groups of East-Central Europe and on the Roma Population of the Area | journal = Frontiers in Genetics | volume = 10 | pages = 558 | year = 2019 | pmid = 31263480 | pmc = 6585392 | doi = 10.3389/fgene.2019.00558 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="Lazaridis2022">{{cite journal| author=Lazaridis I, Alpaslan-Roodenberg S, Acar A, Açıkkol A, Agelarakis A, Aghikyan L | display-authors=etal| title=A genetic probe into the ancient and medieval history of Southern Europe and West Asia. | journal=Science | year= 2022 | volume= 377 | issue= 6609 | pages= 940–951 | pmid=36007020 | doi=10.1126/science.abq0755 | pmc=10019558 | bibcode=2022Sci...377..940L}}</ref> Several studies have also found Central Asian contributions.<ref name="cinnioglu 2004" /><ref name="Lazaridis2022"/><ref name="Berkman_2006">{{cite book | vauthors = Berkman C |date=September 2006 |title=Comparative Analyses for the Central Asian Contribution to Anatolian Gene Pool with Reference to Balkans |type=PhD Thesis |page=v|publisher=Middle East Technical University |url=http://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12607764/index.pdf}}</ref><ref name="Berkman_2009">{{cite journal | vauthors = Berkman CC, Togan İ |doi=10.1016/j.dam.2008.06.037|title=The Asian contribution to the Turkish population with respect to the Balkans: Y-chromosome perspective|journal=Discrete Applied Mathematics|volume=157|issue=10|pages=2341–8|year=2009 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Benedetto_2001">{{cite journal | vauthors = Di Benedetto G, Ergüven A, Stenico M, Castrì L, Bertorelle G, Togan I, Barbujani G | title = DNA diversity and population admixture in Anatolia | journal = American Journal of Physical Anthropology | volume = 115 | issue = 2 | pages = 144–56 | date = June 2001 | pmid = 11385601 | doi = 10.1002/ajpa.1064 | citeseerx = 10.1.1.515.6508 }}</ref><ref name="Haber_et_al_2015">{{cite journal | vauthors = Haber M, Mezzavilla M, Xue Y, Comas D, Gasparini P, Zalloua P, Tyler-Smith C | title = Genetic evidence for an origin of the Armenians from Bronze Age mixing of multiple populations | journal = European Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 24 | issue = 6 | pages = 931–6 | date = June 2016 | pmid = 26486470 | doi = 10.1038/ejhg.2015.206| pmc = 4820045 |biorxiv=10.1101/015396 | s2cid = 196677148 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| According to a different genetic research on 75 individuals from various parts of ], Mergen et al revealed that genetic structure of the mtDNAs in the ] population bears similarities to Turkic Central Asian populations. The neighbour-joining tree built from segment I sequences for Turkish and the other populations (French, Bulgarian, British, Finland, Greek, German, Kazakhs, Uighurs and Kirghiz) indicated two poles. Turkic Central Asian populations, Turkish population and British population formed one pole, and European populations formed the other, which revealed Turkish population bears more similarities to ] population and ].<ref>Hatice Mergen et al. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in the Anatolian Peninsula (Turkey), Journal of Genetics, Vol. 83, No.1, April 2004, article p.46 and fig.4 or http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15240908</ref> | |||

| == Central Asian geneflow == | |||

| ==Haplogroup distributions in Turkish people== | |||

| {{see|Genetic history of Central Asia}} | |||

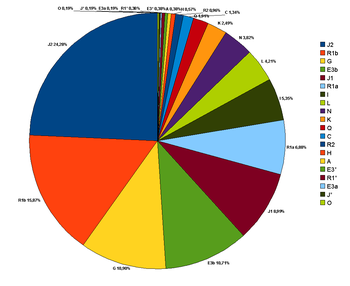

| According to Cinnioglu et al., (2004)<ref name="cinnioglu 2004"></ref> there are many Y-DNA haplogroups present in Turkey. The majority haplogroups are primarily shared with Middle Eastern, Caucasian, and European populations such as haplogroups E3b, G, J, I, R1a, R1b, K and T which form 78.5% from the Turkish ] (without R1b, K, and which notably occur elsewhere, it is 59.3%) and contrast with a smaller share of haplogroups related to Central Asia (N and Q)- 5.7% (but it rises to 36% if K, R1a, R1b and L- which infrequently occur in Central Asia, but are notable in many other Western Turkic groups), India H, R2 - 1.5% and Africa A, E3*, E3a - 1%. Some of the percentages identified were: | |||

| Several studies have investigated to what extent a gene flow from Central Asia to ] contributed to the gene pool of the Turkish people and the role of the 11th-century settlement by ]. ] is home to numerous populations that "demonstrate an array of mixed anthropological features of East Eurasians (EEA) and West Eurasians (WEA)"; two studies showed ] have 40-53% ancestry classified as East Asian, with the rest being classified as European;<ref name="pmid23166524">{{cite journal| author=Xu S| title=Human population admixture in Asia. | journal=Genomics Inform | year= 2012 | volume= 10 | issue= 3 | pages= 133–44 | pmid=23166524 | doi=10.5808/GI.2012.10.3.133 | pmc=3492649 }} </ref> another study put the European-related ancestry at 36%.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last1=He |first1=Guanglin |last2=Wang |first2=Zheng |last3=Wang |first3=Mengge |last4=Luo |first4=Tao |last5=Liu |first5=Jing |last6=Zhou |first6=You |last7=Gao |first7=Bo |last8=Hou |first8=Yiping |date=November 2018 |title=Forensic ancestry analysis in two Chinese minority populations using massively parallel sequencing of 165 ancestry-informative SNPs |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29869338/ |journal=Electrophoresis |volume=39 |issue=21 |pages=2732–2742 |doi=10.1002/elps.201800019 |issn=1522-2683 |pmid=29869338|s2cid=46935911 }}</ref> A 2018 ] ] study suggested that ] slowly transitioned from ] and ]-speaking groups with largely western Eurasian ancestry to increasing East Asian ancestry with Turkic and Mongolic groups in the past 4000 years, including extensive Turkic migrations out of Mongolia and slow assimilation of local populations.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last1=Damgaard |first1=Peter de Barros |last2=Marchi |first2=Nina |last3=Rasmussen |first3=Simon |last4=Peyrot |first4=Michaël |last5=Renaud |first5=Gabriel |last6=Korneliussen |first6=Thorfinn |last7=Moreno-Mayar |first7=J. Víctor |last8=Pedersen |first8=Mikkel Winther |last9=Goldberg |first9=Amy |last10=Usmanova |first10=Emma |last11=Baimukhanov |first11=Nurbol |last12=Loman |first12=Valeriy |last13=Hedeager |first13=Lotte |last14=Pedersen |first14=Anders Gorm |last15=Nielsen |first15=Kasper |date=May 2018 |title=137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0094-2 |journal=Nature |language=en |volume=557 |issue=7705 |pages=369–374 |doi=10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2 |pmid=29743675 |bibcode=2018Natur.557..369D |hdl=1887/3202709 |s2cid=13670282 |issn=1476-4687 |quote=The steppe was likely largely Iranian-speaking in the 2nd and 1st millennia BCE. This is supported by the split of the Indo-Iranian linguistic branch into Iranian and Indian32, the distribution of the Iranian languages, and the preservation of Old Iranian loanwords in Tocharian33. The wide distribution of the Turkic languages from Northwest China, Mongolia and Siberia in the east to Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania and Lithuania in the west implies large-scale migrations out of the homeland in Mongolia since the beginning of the Common Era34. The diversification within the Turkic languages suggests that several waves of migrations occurred35, and on the basis of the impact of local languages gradual assimilation to local populations were already assumed36. The East Asian migration starting with the Xiongnu complies well with the hypothesis that early Turkic was their major language37. Further migrations of East Asians westwards find a good linguistic correlate in the influence of Mongolian on Turkic and Iranian in the last millennium38. As such, the genomic history of the Eurasian steppe is the story of a gradual transition from Bronze Age pastoralists of western Eurasian ancestry, towards mounted warriors of increased East Asian ancestry – a process that continued well into historical times.|hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Two earlier (2000 and 2002) studies suggested that, although the Turks' settlement of Anatolia was of ] importance, including the introduction of the ] and ], the genetic contribution from ] may have been slight.<ref name="eurostudy" /><ref name="med_pops">{{cite journal | vauthors = Arnaiz-Villena A, Gomez-Casado E, Martinez-Laso J | title = Population genetic relationships between Mediterranean populations determined by HLA allele distribution and a historic perspective | journal = Tissue Antigens | volume = 60 | issue = 2 | pages = 111–21 | date = August 2002 | pmid = 12392505 | doi = 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600201.x }}</ref> A 2020 global study looking at whole-genome sequences showed that Turks have relatively lower within-population shared identical-by-descent genomic fragments compared to the rest of the world, suggesting mixture of remote populations.<ref name="Khvorykh_et_al2020">{{cite journal| author=Khvorykh GV, Mulyar OA, Fedorova L, Khrunin AV, Limborska SA, Fedorov A| title=Global Picture of Genetic Relatedness and the Evolution of Humankind. | journal= Biology| year= 2020 | volume= 9 | issue= 11 | page=392 | pmid=33182715 | doi=10.3390/biology9110392 | pmc=7696950 |quote=Due to a historically high number of admixed people and large population sizes, the numbers of shared IBD fragments within the same population in the aforementioned groups are the lowest compared to the rest of the world (for Pathans, their shared number of IBDs among themselves is the record low—8.95; this is followed by Azerbaijanians and Uyghurs, each at 10.8; Uzbeks at 11.1; Iranians at 12.2; and Turks at 12.9). Together, the low number of shared IBDs within the same population and the high values for relative relatedness from multiple DHGR components (Supplementary Table S4) indicate the populations with the strongest admixtures where millions of people from remote populations mixed with each other for hundreds of years. In Europe, such admixed populations include the Moldavians, Greeks, Italians, Hungarians, and Tatars, among others. In the Americas, the highest admixture was detected in the Mexicans from Los Angeles (MXL) and Peruvians (PEL) presented by the 1000 Genomes Project.| doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| *]=24% - J2 (M172) Typical of populations of Caucasus, the Near East, Southeast Europe, Southwest Asia with a moderate distribution through much of ], South Asia, and North Africa. | |||

| *]=14.7% -Typical of Western Europeans, Eurasian People, and typical of ] in the Central Asia <ref>Klyosov A.A. ''"The principal mystery in the relationship of Indo-European and Türkic linguistic families, and an attempt to solve it with the help of DNA genealogy: reflections of a non-linguist"''//Proceedings of Russian Academy of DNA Genealogy (ISSN 1942-7484), Vol. 3, No 1, pp. 3 - 58</ref><ref>Y Haplogroups of the World </ref> | |||

| *]=10.9% - Typical of people from the ] and to a lesser extent the Middle East. | |||

| *]=10.7% - Typical of people from the ] | |||

| *]=9% - Typical amongst people from the Arabian Peninsula and ] (ranging from 3% from Turks around ] to 12% in ]). | |||

| *]=6.9% - Typical of Central Asian, Caucasus, ] people, Eastern Europeans and Indo-Aryan people. | |||

| *]=5.3% - Typical of Central Europeans, Western Caucasian and Balkan populations. | |||

| *]=4.5% - Typical of Asian populations and Caucasian populations. | |||

| *]=4.2% - Typical of Indian Subcontinent and ] populations. | |||

| *]=3.8% - Typical of Uralic, Siberian and Altaic populations. | |||

| *]=2.5% - Typical of Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, Northeast African and South Asian populations | |||

| *]=1.9% - Typical of Northern Altaic populations. | |||

| A 2003 study found that some ] remains from Mongolia had paternal and maternal genetic lineages that have also been found in people from modern-day Turkey.<ref name=Keyser-Tracqui_et_al>{{cite journal | vauthors = Keyser-Tracqui C, Crubézy E, Ludes B | title = Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis of a 2,000-year-old necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia | journal = American Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 73 | issue = 2 | pages = 247–60 | date = August 2003 | pmid = 12858290 | pmc = 1180365 | doi = 10.1086/377005 }}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Keyser-Tracqui|Crubézy|Ludes|2003|ps=: "After the fusion of the A and B sectors, new graves were dug in the west. These graves correspond to a group of genetically linked individuals, since they belong to a single paternal lineage. Interestingly, this paternal lineage has been, at least in part (6 of 7 STRs), found in a present-day Turkish individual (Henke et al. 2001). Moreover, the mtDNA sequence shared by four of these paternal relatives (from graves 46, 52, 54, and 57) were also found in a Turkish individuals (Comas et al. 1996), suggesting a possible Turkish origin of these ancient specimens. Two other individuals buried in the B sector (graves 61 and 90) were characterized by mtDNA sequences found in Turkish people (Calafell 1996; Richards et al. 2000). These data might reflect the emergence at the end of the necropolis of a Turkish component in the Xiongnu tribe."}}</ref> Most (89%) of the Xiongnu sequences in this study belonged to ] ],<ref>{{harvnb|Keyser-Tracqui|Crubézy|Ludes|2003|ps=: "A majority (89%) of the Xiongnu sequences can beclassified as belonging to an Asian haplogroup (A, B4b, C, D4, D5 or D5a, or F1b) and nearly 11% belong to European haplogroups (U2, U5a1a, and J1)."}}</ref> however other studies have shown a significantly higher frequency of West Eurasian maternal and paternal haplogroups in Xiongnu samples, indicating a diverse population. Contact between West and East Eurasian populations pre-dates the Xiongnu period.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rogers |first1=Leland Liu |last2=Kaestle |first2=Frederika Ann |title=Analysis of mitochondrial DNA haplogroup frequencies in the population of the slab burial mortuary culture of Mongolia (ca. 1100–300 BCE ) |journal=American Journal of Biological Anthropology |date=2022 |volume=177 |issue=4 |pages=644–657 |doi=10.1002/ajpa.24478 |s2cid=246508594 |language=en |issn=2692-7691|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ===Further research on Turkish Y-DNA groups=== | |||

| A study from Turkey by Gokcumen (2008)<ref></ref><ref></ref> took into account oral histories and historical records. They went to four settlements in Central Anatolia and did not do a random selection from a group of university students like many other studies. Accordingly here are the results: | |||

| A study published in 2003 looked at ] genes to investigate the affinity of certain Mongolian tribes with Germans and Anatolian Turks. It was found that Germans and Anatolian Turks were equally distant to the Mongolian populations. No close relationship was found between Anatolian Turks and Mongolians despite the close relationship of their languages and shared historical neighborhood.<ref>{{cite journal | url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12753667/ | pmid=12753667 | year=2003 | last1=Machulla | first1=H. K. | last2=Batnasan | first2=D. | last3=Steinborn | first3=F. | last4=Uyar | first4=F. A. | last5=Saruhan-Direskeneli | first5=G. | last6=Oguz | first6=F. S. | last7=Carin | first7=M. N. | last8=Dorak | first8=M. T. | title=Genetic affinities among Mongol ethnic groups and their relationship to Turks | journal=Tissue Antigens | volume=61 | issue=4 | pages=292–299 | doi=10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00043.x }}</ref> | |||

| '''1)''' At an ] village whose oral stories tell they come from Central Asia they found that 57% come from haplogroup L, 13% from haplogroup Q, 3% from haplogroup N thus indicating that the L haplogroups in Turkey are of Central Asian heritage rather than Indian, although these Central Asians would have gotten the L markers from the Indians from the beginning. These Asian groups add up to 73% in this village. Furthermore 10% of these Afshars were E3a and E3b. Only 13% were J2a, the most common haplogroup in Turkey. | |||

| A study of 75 individuals from various parts of ] concluded that the "genetic structure of the ]s in the ] population bears some similarities to Turkic Central Asian populations".<ref name="pmid15240908">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mergen H, Oner R, Oner C | title = Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in the Anatolian Peninsula (Turkey) | journal = Journal of Genetics | volume = 83 | issue = 1 | pages = 39–47 | date = April 2004 | pmid = 15240908 | doi = 10.1007/bf02715828 | url = http://www.ias.ac.in/jgenet/Vol83No1/39.pdf | s2cid = 23098652 }}</ref> | |||

| '''2)''' An older Turkish village center that did not receive much migration was about 25% N and 25% J2a with 3% G and close to 30% of some sort of R1 but mostly R1b. | |||

| A 2001 study comparing the populations of ] and Turkic-speaking peoples of ] estimated the Central Asian genetic contribution to current Anatolian ] loci (one binary and six ]) and mitochondrial DNA gene pool to be roughly 30%.<ref name="Benedetto_2001" /> A 2004 high-resolution ] analysis of Y-chromosomal DNA in samples collected from blood banks, sperm banks, and university students in eight regions of Turkey found evidence for a weak but detectable signal (<9%) of recent paternal gene flow from Central Asia.<ref name="cinnioglu 2004" /> A 2006 study concluded that the true Central Asian contributions to Anatolia was 13% for males and 22% for females (with wide ranges of ]s), and the language replacement in Turkey and might not have been in accordance with the elite dominance model.<ref name="Berkman_2006" /> It was later observed that the male contribution from Central Asia to the Turkish population with reference to the Balkans was 13%. For all non-Turkic speaking populations, the Central Asian contribution was higher than in Turkey.<ref name="Berkman_2009" /> According to the study, "the contributions ranging between 13%–58% must be considered with a caution because they harbor uncertainties about the state of pre-nomadic invasion and further local movements."<ref name="Berkman_2009" /> | |||

| ==Other Studies== | |||

| </ref>]] | |||

| In a 2015 study, Turkish samples were in the West ]n ] which consisted of "all of mainland Europe, Sardinia, Sicily, Cyprus, western Russia, the Caucasus, Turkey, and Iran, and some individuals from Tajikistan and Turkmenistan." In this study, ancestry from East Asia was also visible in Turkish samples, with events after 1000 CE generally involving Asian sources being important when it comes to the ancestry of Turkey and its region.<ref name="Busby_et_al2015">{{cite journal| author=Busby GB, Hellenthal G, Montinaro F, Tofanelli S, Bulayeva K, Rudan I | display-authors=etal| title=The Role of Recent Admixture in Forming the Contemporary West Eurasian Genomic Landscape. | journal=Curr Biol | year= 2015 | volume= 25 | issue= 19 | pages= 2518–26 | pmid=26387712 | doi=10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.007 | pmc=4714572 }}</ref> | |||

| In 2001, Benedetto et al revealed that Central Asian genetic contribution to the current Anatolian ] gene pool was estimated as roughly 30%, by comparing the populations of ], and Turkic-speaking people of ].<ref></ref> In 2003, Cinnioğlu et al. made a research of ] including the samples from eight regions of Turkey, without classifying the ethnicity of the people, which indicated that high resolution ] analysis totally provides evidence of a detectable weak signal (<9%) of gene flow from Central Asia.<ref>"Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia." Human Genetics 114:2 (January 2004): pages 127-148. First published electronically on October 29, 2003. 523</ref> In 2006, Berkman concluded that the true Central Asian contribution to Anatolia for both males and females were assumed to be 22%, with respect to the Balkans.<ref>Ceren Berkman, Comparative Analyses for the Central Asian Contribution to Anatolian Gene Pool with Reference to Balkans, p.98, METU, Sep. 2006 quoted "Lower male than female contribution from Central Asia to Anatolia was obtained. The situation was explained by invoking the idea of homogenization between the males of the Balkans and Anatolia. Since females could not migrate alone, the true Central Asian contribution for both males and females were assumed to be 22%."</ref> In 2011 ] and ] published their study "Who Are the Anatolian Turks? A Reappraisal of the Anthropological Genetic Evidence." They revealed the impossibility of long-term, and continuing genetic contacts between Anatolia and Siberia, and confirmed the presence of significant mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome divergence between this regions, with minimal admixture. The research confirms also the lack of mass migration and suggested that it was irregular punctuated migration events that engendered large-scale shifts in language and culture among Anatolia's diverse autochthonous inhabitants.<ref>Yardumian A, Schurr TG. 2011. Who are the Anatolian Turks? A reappraisal of the anthropological genetic evidence. Archeol Anthropol Eurasia 50(1): 6-43 (Summer).</ref> According to a 2012 study on ethnic Turks of Turkey, Hodoğlugil revealed that there is a significant overlap between Turks and Middle Easterners and a relationship with Europeans and South and Central Asians when Kyrgyz samples are genotyped and analysed. It displays a genetic ancestry for the Turks of 45% Middle Eastern, 40% European and 15% Central Asian. However, the Turkish ] is unique, and there is an admixture of Turkish people reflecting the population migration patterns.<ref>Uğur Hodoğlugil and Robert W. Mahley - Turkish Population Structure and Genetic Ancestry Reveal Relatedness among Eurasian Populations, Annals of Human Genetics, March 2012, Volume 76, Issue 2, pg. 128-141. Abstract "Turkey has experienced major population movements. Population structure and genetic relatedness of samples from three regions of Turkey, using over 500,000 SNP genotypes, were compared together with Human Genome Diversity Panel (HGDP) data. To obtain a more representative sampling from Central Asia, Kyrgyz samples (Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan) were genotyped and analysed. Principal component (PC) analysis reveals a significant overlap between Turks and Middle Easterners and a relationship with Europeans and South and Central Asians; however, the Turkish genetic structure is unique. FRAPPE, STRUCTURE, and phylogenetic analyses support the PC analysis depending upon the number of parental ancestry components chosen. For example, supervised STRUCTURE (K=3) illustrates a genetic ancestry for the Turks of 45% Middle Eastern (95% CI, 42-49), 40% European (95% CI, 36-44) and 15% Central Asian (95% CI, 13-16), whereas at K=4 the genetic ancestry of the Turks was 38% European (95% CI, 35-42), 35% Middle Eastern (95% CI, 33-38), 18% South Asian (95% CI, 16-19) and 9% Central Asian (95% CI, 7-11). PC analysis and FRAPPE/STRUCTURE results from three regions in Turkey (Aydin, Istanbul and Kayseri) were superimposed, without clear subpopulation structure, suggesting sample homogeneity. Thus, this study demonstrates admixture of Turkish people reflecting the population migration patterns."</ref> | |||

| As of 2017, Central Asian genetic variation has been poorly studied, with little or no ] data for countries such as ] and ].<ref name="Taskent_et_al_2017" /> Therefore, future comprehensive genome-wide studies are needed. Turkish people, and other Western Asian populations, may also be closely related to Central Asian populations such as those near Western Asia.<ref name="Taskent_et_al_2017" /> | |||

| Furthermore, and maybe more so, in a study called 'The Genetics of Modern Assyrians and their Relationship to Other People of the Middle East' Dr. Joel J. Elias, a Professor at University of California School of Medicine at San Francisco conducted a genetic test about Turkish people. The aim was to discover the origins of the peoples of the Middle East presently, and over time. He found that "In spite of the complex history of the Middle East and the great number of internal group migrations revealed by history, as well as the mosaic of cultures and languages, the region is relatively homogeneous" in relation to the people that speak different languages throughout the region including Iranian and Kurdish (Indo-European), Turkish (Turkic) and Arabic, Assyrian and Aramaic (Semitic).<ref>The Genetics of Modern Assyrians and their Relationship to Other People of the Middle East></ref> A group of Armenian scientists conducted a study about the origins of the Turkish people in relation to Armenians. Savak Avagian; director of Armenia's bone marrow bank found that “Turks and Armenians were the two societies throughout the world that were genetically close to each other. Kurds are also in same genetic pool”.<ref>ref name= Turks, Armenians share similar genes, say scientists (Hürriyet Daily News) ></ref> | |||

| == Haplogroup distributions == | |||

| ] | |||

| A 2021 study which looked at ]s and ] of 3,362 Turkish people found that the most common ] were J2a, R1b, and R1a (18.4%, 14.9%, and 12.1% respectively). ] and ] ranged from 8.5% to 15.6%. Most common ] were H, U, and T (27.55%, 19.53%, and 10.99% respectively).<ref name="Kars_etal_2021">{{Cite journal |last1=Kars |first1=M. Ece |last2=Başak |first2=A. Nazlı |last3=Onat |first3=O. Emre |last4=Bilguvar |first4=Kaya |last5=Choi |first5=Jungmin |last6=Itan |first6=Yuval |last7=Çağlar |first7=Caner |last8=Palvadeau |first8=Robin |last9=Casanova |first9=Jean-Laurent |last10=Cooper |first10=David N. |last11=Stenson |first11=Peter D. |last12=Yavuz |first12=Alper |last13=Buluş |first13=Hakan |last14=Günel |first14=Murat |last15=Friedman |first15=Jeffrey M. |date=2021-09-07 |title=The genetic structure of the Turkish population reveals high levels of variation and admixture |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |language=en |volume=118 |issue=36 |pages=e2026076118 |bibcode=2021PNAS..11826076K |doi=10.1073/pnas.2026076118 |issn=0027-8424 |pmc=8433500 |pmid=34426522 |quote=Similarly, we detected ∼10% autosomal, 8 to 15% paternal, and ∼8% maternal gene flow from Central Asia. ... This contribution varied for the TR subregions: TR-B, 7.69%; TR-W, 12%; TR-C, 10.1%; TR-N, 10.6%; TR-S, 11.2%; and TR-E, 6.48%. |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| An earlier 2004 study of 523 people found many Y-DNA haplogroups in Turkey.<ref name="cinnioglu 2004" /> Most haplogroups in Turkey are shared with its West Asian and Caucasian neighbors. The most common haplogroup in Turkey is J2 (24%), which is widespread among Mediterranean, Caucasian, and West Asian populations. Haplogroups that are common in Europe (R1b and I; 20%), South Asia (L, R2, H; 5.7%), and Africa (A, E3*, E3a; 1%) are also present. By contrast, Central Asian haplogroups (C, Q, and O) are rarer. However, the figure may rise to 36% if K, R1a, R1b, and L—which infrequently occur in Central Asia but are notable in many other Western Turkic groups—are included. J2 is also frequently found in Central Asia, a notably high frequency (30.4%) being observed among Uzbeks.<ref>Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians {{cite journal | vauthors = Shou WH, Qiao EF, Wei CY, Dong YL, Tan SJ, Shi H, Tang WR, Xiao CJ | display-authors = 6 | title = Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians | journal = Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 55 | issue = 5 | pages = 314–22 | date = May 2010 | pmid = 20414255 | doi = 10.1038/jhg.2010.30 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| The main percentages of Y chromosome haplogroups identified in the 2004 study were as follows:<ref name="cinnioglu 2004" /> | |||

| *]: 24%. J2 (M172) may reflect the spread of Anatolian farmers.<ref name="Semino_et_al_2004">{{cite journal | vauthors = Semino O, Magri C, Benuzzi G, Lin AA, Al-Zahery N, Battaglia V, Maccioni L, Triantaphyllidis C, Shen P, Oefner PJ, Zhivotovsky LA, King R, Torroni A, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Underhill PA, Santachiara-Benerecetti AS | display-authors = 6 | title = Origin, diffusion, and differentiation of Y-chromosome haplogroups E and J: inferences on the neolithization of Europe and later migratory events in the Mediterranean area | journal = American Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 74 | issue = 5 | pages = 1023–34 | date = May 2004 | pmid = 15069642 | pmc = 1181965 | doi = 10.1086/386295 }}</ref> J2-M172 is "mainly confined to the Mediterranean coastal areas, southeastern Europe and Anatolia", as well as West Asia and Central Asia.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Shou WH, Qiao EF, Wei CY, Dong YL, Tan SJ, Shi H, Tang WR, Xiao CJ | display-authors = 6 | title = Y-chromosome distributions among populations in Northwest China identify significant contribution from Central Asian pastoralists and lesser influence of western Eurasians | journal = Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 55 | issue = 5 | pages = 314–22 | date = May 2010 | pmid = 20414255 | doi = 10.1038/jhg.2010.30 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| *]: 15.9%. R1b is found in Europe, West Asia, Central Asia, Southern Asia, some parts of the Sahel region of Africa.<ref name="Myres_et_al_2010">{{cite journal | vauthors = Myres NM, Rootsi S, Lin AA, Järve M, King RJ, Kutuev I, Cabrera VM, Khusnutdinova EK, Pshenichnov A, Yunusbayev B, Balanovsky O, Balanovska E, Rudan P, Baldovic M, Herrera RJ, Chiaroni J, Di Cristofaro J, Villems R, Kivisild T, Underhill PA | display-authors = 6 | title = A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe | journal = European Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 19 | issue = 1 | pages = 95–101 | date = January 2011 | pmid = 20736979 | pmc = 3039512 | doi = 10.1038/ejhg.2010.146 }}</ref> | |||

| *]: 10.9%. Haplogroup G has also been associated with the spread of agriculture (together with J2 clades) and is "largely restricted to populations of the Caucasus and the Near/Middle East and southern Europe."<ref name="Rootsi_et_al_2012">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rootsi S, Myres NM, Lin AA, Järve M, King RJ, Kutuev I, Cabrera VM, Khusnutdinova EK, Varendi K, Sahakyan H, Behar DM, Khusainova R, Balanovsky O, Balanovska E, Rudan P, Yepiskoposyan L, Bahmanimehr A, Farjadian S, Kushniarevich A, Herrera RJ, Grugni V, Battaglia V, Nici C, Crobu F, Karachanak S, Hooshiar Kashani B, Houshmand M, Sanati MH, Toncheva D, Lisa A, Semino O, Chiaroni J, Di Cristofaro J, Villems R, Kivisild T, Underhill PA | display-authors = 6 | title = Distinguishing the co-ancestries of haplogroup G Y-chromosomes in the populations of Europe and the Caucasus | journal = European Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 20 | issue = 12 | pages = 1275–82 | date = December 2012 | pmid = 22588667 | pmc = 3499744 | doi = 10.1038/ejhg.2012.86 }}</ref> The G2a subclade in particular is associated with the Early European Farmers, who in turn descend from the Anatolian farmers.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /> | |||

| *]: 10.7% (E3b1-M78 and E3b3-M123 accounting for all E representatives in the sample, besides a single E3b2-M81 chromosome). E-M78 is common along a line from the ] via ] to the ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cruciani F, La Fratta R, Torroni A, Underhill PA, Scozzari R | title = Molecular dissection of the Y chromosome haplogroup E-M78 (E3b1a): a posteriori evaluation of a microsatellite-network-based approach through six new biallelic markers | journal = Human Mutation | volume = 27 | issue = 8 | pages = 831–2 | date = August 2006 | pmid = 16835895 | doi = 10.1002/humu.9445 | s2cid = 26886757 | doi-access = free }}</ref> ] is found in both Africa and Eurasia. | |||

| *]: 9% | |||

| *]: 6.9% | |||

| *]: 5.3% | |||

| *]: 4.5% | |||

| *]: 4.2% | |||

| *]: 3.8% | |||

| *]: 2.5% | |||

| *]: 1.9% | |||

| *]: 1.3% | |||

| *]: 0.96% | |||

| Other markers that occurred in less than 1% are H, A, E3a, O, and R1*. | |||

| ] reveals a primarily common pre-Ottoman paternal ancestry with ]. PLoS ONE 12(6): e0179474. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0179474]] | |||

| A 2011 study<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Gokcumen |first1=Ömer |last2=Gultekin |first2=Timur |last3=Alakoc |first3=Yesim Dogan |last4=Tug |first4=Aysim |last5=Gulec |first5=Erksin |last6=Schurr |first6=Theodore G. |title=Biological Ancestries, Kinship Connections, and Projected Identities in Four Central Anatolian Settlements: Insights from Culturally Contextualized Genetic Anthropology |journal=American Anthropologist |date=2011 |volume=113 |issue=1 |pages=125–126 |doi=10.1111/j.1548-1433.2010.01310.x |pmid=21560269 |url=https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2010.01310.x |language=en}}</ref> took into account oral histories and historical records. The researchers went to four settlements in Central Anatolia and chose a random selection of subjects from among university students. | |||

| In an ] village near Ankara where, according to oral tradition, the ancestors of the inhabitants came from Central Asia, the researchers found that 57% of the villagers had ], 13% had haplogroup Q and 3% had haplogroup N. The high rate of haplogroup L observed in this study, which is most common in ], was difficult for researchers to explain and could not be traced back to any specific geographic location, and authors said it would be difficult to associate this haplogroup with the Turkic migrations, given the paucity of evidence.<ref>{{harvnb|Gokcumen|Gultekin|Alakoc|Tug|Gulec|Schurr|2011|p=126|ps=:"Given these data, it is possible that these haplogroups | |||

| may represent the nomadic Turkic groups that immigrated | |||

| into Anatolia from Central Asia. However, this argument | |||

| fails to explain the lack of haplogroup L in the population of | |||

| Kizilyer region, which also claims strong Turkic ancestry. | |||

| Therefore, even though the Afsars were one of the main | |||

| tribes historically known to have migrated into Anatolia | |||

| from Central Asia (Cahen 1968), it is difficult to directly | |||

| associate haplogroup L with the larger Turkic migration(s). | |||

| The lack of data from other Afsar groups in Anatolia and | |||

| elsewhere currently makes it impossible at this time to trace | |||

| the observed Gocmenkoy L haplotypes back to Central Asia | |||

| or to any other geographic region."}}</ref> Furthermore, 10% of the Afshars had haplogroups E3a and E3b, while only 13% had haplogroup J2a, the most common in Turkey. | |||

| By contrast, the inhabitants of a traditional Turkish village that had little migration had about 25% haplogroup N and 25% J2a, with 3% G and close to 30% R1 variants (mostly R1b). | |||

| == Whole genome sequencing== | |||

| ] | |||

| A ] study of Turkish genetics, conducted on 16 individuals, concluded that the Turkish population forms a cluster with Southern European and Mediterranean populations and that the predicted contribution from ancestral ] populations is 21.7% (presumably reflecting a ] origin).<ref name=Alkan>{{cite journal | vauthors = Alkan C, Kavak P, Somel M, Gokcumen O, Ugurlu S, Saygi C, Dal E, Bugra K, Güngör T, Sahinalp SC, Özören N, Bekpen C | display-authors = 6 | title = Whole genome sequencing of Turkish genomes reveals functional private alleles and impact of genetic interactions with Europe, Asia and Africa | journal = BMC Genomics | volume = 15 | pages = 963 | date = November 2014 | issue = 1 | pmid = 25376095 | pmc = 4236450 | doi = 10.1186/1471-2164-15-963 | doi-access = free }}</ref> However, that does not provide a direct estimate of a migration rate, because of factors such as the unknown original contributing populations.<ref name=Alkan /> Given Europeans and Native Americans may share ] ancestry, "significant Ancient North Eurasian ancestry might also be found in Turkish genetic profiles; this requires further study".<ref name=Alkan /> | |||

| Another study in 2021, which looked at whole-genomes and ] of 3,362 unrelated Turkish samples, resulted in establishing the first Turkish ] and found "extensive admixture between Balkan, Caucasus, Middle Eastern, and European populations" in line with history of Turkey.<ref name="Kars_etal_2021"/> Moreover, significant number of rare genome and exome variants were unique to modern-day Turkish population.<ref name="Kars_etal_2021"/> Neighbouring populations in East and West, and Tuscan people in Italy were closest to Turkish population in terms of genetic similarity.<ref name="Kars_etal_2021"/> Central Asian contribution to maternal, paternal, and autosomal genes were detected, consistent with the historical migration and expansion of ] from Central Asia.<ref name="Kars_etal_2021"/> Central Asian autosomal DNA geneflow was estimated as around 10%.<ref name="Kars_etal_2021"/> Using haplogroups that are only found in Central Asia, the study estimated Central Asian paternal and maternal contributions. Paternal contribution was estimated as between 8.5% to 15.6% based on ] and ] Y-chromosome haplogroups. Maternal contributions was estimated as around 8% based on ] and ] mtDNA haplogroups.<ref name="Kars_etal_2021"/> The authors speculated that the genetic similarity of the modern-day Turkish population with modern-day European populations might be due to ], which impacted the genetic makeup of modern-day European populations.<ref name="Kars_etal_2021"/> Moreover, the study found no clear genetic separation between different regions of Turkey, leading authors to suggest that recent migration events within Turkey resulted in genetic homogenization.<ref name="Kars_etal_2021"/> | |||

| == Other studies == | |||

| A 2001 study that looked at ] ]s suggested that "Turks, Kurds, Armenians, Iranians, Jews, Lebanese and other (Eastern and Western) Mediterranean groups seem to share a common ancestry" and that historical populations such as Anatolian ] and ] groups (older than 2000 B.C.) "may have given rise to present‐day Kurdish, Armenian and Turkish populations."<ref name="antigens57"/> A 2004 study that looked at 11 human‐specific ] insertion ] among ], Macedonians, Albanians, Romanians, Greeks, and Turks, suggested a common ancestry for these populations.<ref name="Comas2004">{{cite journal | vauthors = Comas D, Schmid H, Braeuer S, Flaiz C, Busquets A, Calafell F, Bertranpetit J, Scheil HG, Huckenbeck W, Efremovska L, Schmidt H | display-authors = 6 | title = Alu insertion polymorphisms in the Balkans and the origins of the Aromuns | journal = Annals of Human Genetics | volume = 68 | issue = Pt 2 | pages = 120–7 | date = March 2004 | pmid = 15008791 | doi = 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00080.x | s2cid = 21773796 }}</ref> | |||

| A 2011 study ruled out long-term and continuing genetic contacts between Anatolia and Siberia and confirmed the presence of significant mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome divergence between these regions, with minimal admixture. The research also confirmed the lack of mass migration and suggested that it was irregular punctuated migration events that engendered large-scale shifts in language and culture among Anatolia's diverse autochthonous inhabitants.<ref name=Yardumian_et_al /> | |||

| ] | |||

| A study in 2015, however, wrote, "Previous genetic studies have generally used Turks as representatives of ancient Anatolians. Our results show that Turks are genetically shifted towards Central Asians, a pattern consistent with a history of mixture with populations from this region." The authors found "7.9% (±0.4) East Asian ancestry in Turks from admixture occurring 800 (±170) years ago."<ref name="Haber_et_al_2015"/> | |||

| According to a 2012 study of ethnic Turks, "Turkish population has a close genetic similarity to Middle Eastern and European populations and some degree of similarity to South Asian and Central Asian populations."<ref name="Hodoglugil_et_al">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hodoğlugil U, Mahley RW | title = Turkish population structure and genetic ancestry reveal relatedness among Eurasian populations | journal = Annals of Human Genetics | volume = 76 | issue = 2 | pages = 128–41 | date = March 2012 | pmid = 22332727 | pmc = 4904778 | doi = 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x }}</ref> The analysis modeled each person's DNA as having originated from ''K'' ancestral populations and varied the parameter ''K'' from 2 to 7. At ''K'' = 3, comparing to individuals from the Middle East (Druze and Palestinian), Europe (French, Italian, Tuscan and Sardinian) and Central Asia (Uygur, Hazara and Kyrgyz), clustering results indicated that the contributions were 45%, 40% and 15% for the Middle Eastern, European and Central Asian populations, respectively. At ''K'' = 4, results for paternal ancestry were 38% European, 35% Middle Eastern, 18% South Asian, and 9% Central Asian. At ''K'' = 7, results of paternal ancestry were 77% European, 12% South Asian, 4% Middle Eastern, and 6% Central Asian. However, results may reflect either previous population movements (such as migration and admixture) or genetic drift.<ref name=Hodoglugil_et_al /> The Turkish samples were closest to the ] population (]) from the ]; other sampled groups included European (French, Italian), Middle Eastern (Druze, Palestinian), and Central (Kyrgyz, Hazara, Uygur), South Asian (Indian), and East Asian (Mongolian, Han) populations.<ref name="Hodoglugil_et_al"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| A study involving mitochondrial analysis of a ] population, whose samples were gathered from excavations in the archaeological site of ], found that these samples were closest to modern samples from "Turkey, Crimea, Iran and Italy (Campania and Puglia), Cyprus and the Balkans (Bulgaria, Croatia, and Greece)."<ref name=Ottoni_et_al>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ottoni C, Ricaut FX, Vanderheyden N, Brucato N, Waelkens M, Decorte R | title = Mitochondrial analysis of a Byzantine population reveals the differential impact of multiple historical events in South Anatolia | journal = European Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 19 | issue = 5 | pages = 571–6 | date = May 2011 | pmid = 21224890 | pmc = 3083616 | doi = 10.1038/ejhg.2010.230 }}</ref> Modern-day samples from the nearby town of ] showed that lineages of East Eurasian descent assigned to ] were found in the modern samples from Ağlasun. This haplogroup was significantly more frequent in Ağlasun (15%) than in Byzantine Sagalassos, but the study found "no genetic discontinuity across two millennia in the region."<ref>Comparing maternal genetic variation across two millennia reveals the demographic history of an ancient human population in southwest Turkey | |||

| {{cite journal | vauthors = Ottoni C, Rasteiro R, Willet R, Claeys J, Talloen P, Van de Vijver K, Chikhi L, Poblome J, Decorte R | display-authors = 6 | title = Comparing maternal genetic variation across two millennia reveals the demographic history of an ancient human population in southwest Turkey | journal = Royal Society Open Science | volume = 3 | issue = 2 | pages = 150250 | date = February 2016 | pmid = 26998313 | pmc = 4785964 | doi = 10.1098/rsos.150250 | bibcode = 2016RSOS....350250O }}</ref> | |||

| A 2019 study found that Turkish people cluster with Southern and Mediterranean Europe populations along with groups in the northern part of Southwest Asia (such as the populations from Caucasus, Northern Iraq, and Iranians).<ref name="Pakstis_et_al_2019"/> Another 2019 study found that Turkish people have the lowest fixation index distances with Caucasus population group and Iranian-Syrian group, as compared to East-Central European, European (including Northern and Eastern European), Sardinian, Roma, and Turkmen groups or populations. The Caucasus group in the study included samples from Abkhazians, Adygey, Armenians, Balkars, Chechens, Georgians, Kumyks, Kurds, Lezgins, Nogays, and North Ossetians.<ref name="Banfai_et_al_2019"/> A 2022 study, which looked at modern-day populations and more than 700 ancient genomes from Southern Europe and West Asia covering a period of 11,000 years, found that Turkish people carry the genetic legacy of “both ancient people who lived in Anatolia for thousands of years covered by our study and people coming from Central Asia bearing Turkic languages” and that “The genetic contribution of Central Asian Turkic speakers to present-day people can be provisionally estimated by comparison of Central Asian ancestry in present-day Turkish people (~9%) and sampled ancient Central Asians (range of ~41-100%) to be between 9/100 and 9/41 or ~9-22%”.<ref name="Lazaridis2022"/> | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| == References and notes == | == References and notes == | ||

| {{Reflist|2}} | {{Reflist|2}} | ||

| {{human genetics}} | |||

| http://en.wikipedia.org/Haplogroup_J2_%28Y-DNA%29 | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Genetic Origins Of The Turkish People}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Genetic Origins Of The Turkish People}} | ||

| <!--Categories--> | <!--Categories--> | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:56, 27 December 2024

DNA analyses of the ethnic Turks from Turkey| This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: "Genetic studies on Turkish people" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Population genetics research has been conducted on the ancestry of the modern Turkish people (not to be confused with Turkic peoples) in Turkey. Such studies are relevant for the demographic history of the population as well as health reasons, such as population specific diseases. Some studies have sought to determine the relative contributions of the Turkic peoples of Central Asia, from where the Seljuk Turks began migrating to Anatolia after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, which led to the establishment of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate in the late 11th century, and prior populations in the area who were culturally assimilated during the Seljuk and the Ottoman periods.

Turkish genomic variation, along with several other Western Asian populations, looks most similar to genomic variation of South European populations such as southern Italians. Western Asian genomes, including Turkish ones, have been greatly influenced by early agricultural populations in the area; later population movements, such as those of Turkic speakers, also contributed. However, the genetic variation of various populations in Central Asia "has been poorly characterized"; Western Asian populations may also be "closely related to populations in the east".

Multiple studies have found similarities or common ancestry between Turkish people and present-day or historic populations in the Mediterranean, West Asia and the Caucasus. Several studies have also found Central Asian contributions.

Central Asian geneflow

Further information: Genetic history of Central AsiaSeveral studies have investigated to what extent a gene flow from Central Asia to Anatolia contributed to the gene pool of the Turkish people and the role of the 11th-century settlement by Oghuz Turks. Central Asia is home to numerous populations that "demonstrate an array of mixed anthropological features of East Eurasians (EEA) and West Eurasians (WEA)"; two studies showed Uyghurs have 40-53% ancestry classified as East Asian, with the rest being classified as European; another study put the European-related ancestry at 36%. A 2018 autosomal single-nucleotide polymorphism study suggested that Eurasian Steppe slowly transitioned from Indo European and Iranian-speaking groups with largely western Eurasian ancestry to increasing East Asian ancestry with Turkic and Mongolic groups in the past 4000 years, including extensive Turkic migrations out of Mongolia and slow assimilation of local populations.

Two earlier (2000 and 2002) studies suggested that, although the Turks' settlement of Anatolia was of cultural importance, including the introduction of the Turkish language and Islam, the genetic contribution from Central Asia may have been slight. A 2020 global study looking at whole-genome sequences showed that Turks have relatively lower within-population shared identical-by-descent genomic fragments compared to the rest of the world, suggesting mixture of remote populations.

A 2003 study found that some Xiongnu remains from Mongolia had paternal and maternal genetic lineages that have also been found in people from modern-day Turkey. Most (89%) of the Xiongnu sequences in this study belonged to Asian maternal haplogroups, however other studies have shown a significantly higher frequency of West Eurasian maternal and paternal haplogroups in Xiongnu samples, indicating a diverse population. Contact between West and East Eurasian populations pre-dates the Xiongnu period.

A study published in 2003 looked at Human leukocyte antigen genes to investigate the affinity of certain Mongolian tribes with Germans and Anatolian Turks. It was found that Germans and Anatolian Turks were equally distant to the Mongolian populations. No close relationship was found between Anatolian Turks and Mongolians despite the close relationship of their languages and shared historical neighborhood.

A study of 75 individuals from various parts of Turkey concluded that the "genetic structure of the mitochondrial DNAs in the Turkish population bears some similarities to Turkic Central Asian populations".

A 2001 study comparing the populations of Mediterranean Europe and Turkic-speaking peoples of Central Asia estimated the Central Asian genetic contribution to current Anatolian Y-chromosome loci (one binary and six short tandem repeat) and mitochondrial DNA gene pool to be roughly 30%. A 2004 high-resolution SNP analysis of Y-chromosomal DNA in samples collected from blood banks, sperm banks, and university students in eight regions of Turkey found evidence for a weak but detectable signal (<9%) of recent paternal gene flow from Central Asia. A 2006 study concluded that the true Central Asian contributions to Anatolia was 13% for males and 22% for females (with wide ranges of confidence intervals), and the language replacement in Turkey and might not have been in accordance with the elite dominance model. It was later observed that the male contribution from Central Asia to the Turkish population with reference to the Balkans was 13%. For all non-Turkic speaking populations, the Central Asian contribution was higher than in Turkey. According to the study, "the contributions ranging between 13%–58% must be considered with a caution because they harbor uncertainties about the state of pre-nomadic invasion and further local movements."

In a 2015 study, Turkish samples were in the West Eurasian clade which consisted of "all of mainland Europe, Sardinia, Sicily, Cyprus, western Russia, the Caucasus, Turkey, and Iran, and some individuals from Tajikistan and Turkmenistan." In this study, ancestry from East Asia was also visible in Turkish samples, with events after 1000 CE generally involving Asian sources being important when it comes to the ancestry of Turkey and its region.

As of 2017, Central Asian genetic variation has been poorly studied, with little or no whole genome sequencing data for countries such as Turkmenistan and Afghanistan. Therefore, future comprehensive genome-wide studies are needed. Turkish people, and other Western Asian populations, may also be closely related to Central Asian populations such as those near Western Asia.

Haplogroup distributions

A 2021 study which looked at whole genomes and whole-exomes of 3,362 Turkish people found that the most common Y chromosome haplogroups were J2a, R1b, and R1a (18.4%, 14.9%, and 12.1% respectively). Haplogroups C-M130 and O3 ranged from 8.5% to 15.6%. Most common mtDNA haplogroups were H, U, and T (27.55%, 19.53%, and 10.99% respectively).

An earlier 2004 study of 523 people found many Y-DNA haplogroups in Turkey. Most haplogroups in Turkey are shared with its West Asian and Caucasian neighbors. The most common haplogroup in Turkey is J2 (24%), which is widespread among Mediterranean, Caucasian, and West Asian populations. Haplogroups that are common in Europe (R1b and I; 20%), South Asia (L, R2, H; 5.7%), and Africa (A, E3*, E3a; 1%) are also present. By contrast, Central Asian haplogroups (C, Q, and O) are rarer. However, the figure may rise to 36% if K, R1a, R1b, and L—which infrequently occur in Central Asia but are notable in many other Western Turkic groups—are included. J2 is also frequently found in Central Asia, a notably high frequency (30.4%) being observed among Uzbeks.

The main percentages of Y chromosome haplogroups identified in the 2004 study were as follows:

- J2: 24%. J2 (M172) may reflect the spread of Anatolian farmers. J2-M172 is "mainly confined to the Mediterranean coastal areas, southeastern Europe and Anatolia", as well as West Asia and Central Asia.

- R1b: 15.9%. R1b is found in Europe, West Asia, Central Asia, Southern Asia, some parts of the Sahel region of Africa.

- G: 10.9%. Haplogroup G has also been associated with the spread of agriculture (together with J2 clades) and is "largely restricted to populations of the Caucasus and the Near/Middle East and southern Europe." The G2a subclade in particular is associated with the Early European Farmers, who in turn descend from the Anatolian farmers.

- E3b-M35: 10.7% (E3b1-M78 and E3b3-M123 accounting for all E representatives in the sample, besides a single E3b2-M81 chromosome). E-M78 is common along a line from the Horn of Africa via Egypt to the Balkans. Haplogroup E-M123 is found in both Africa and Eurasia.

- J1: 9%

- R1a: 6.9%

- I: 5.3%

- K: 4.5%

- L: 4.2%

- N: 3.8%

- T: 2.5%

- Q: 1.9%

- C: 1.3%

- R2: 0.96%

Other markers that occurred in less than 1% are H, A, E3a, O, and R1*.

A 2011 study took into account oral histories and historical records. The researchers went to four settlements in Central Anatolia and chose a random selection of subjects from among university students.

In an Afshar village near Ankara where, according to oral tradition, the ancestors of the inhabitants came from Central Asia, the researchers found that 57% of the villagers had haplogroup L, 13% had haplogroup Q and 3% had haplogroup N. The high rate of haplogroup L observed in this study, which is most common in South Asia, was difficult for researchers to explain and could not be traced back to any specific geographic location, and authors said it would be difficult to associate this haplogroup with the Turkic migrations, given the paucity of evidence. Furthermore, 10% of the Afshars had haplogroups E3a and E3b, while only 13% had haplogroup J2a, the most common in Turkey.

By contrast, the inhabitants of a traditional Turkish village that had little migration had about 25% haplogroup N and 25% J2a, with 3% G and close to 30% R1 variants (mostly R1b).

Whole genome sequencing

A whole-genome sequencing study of Turkish genetics, conducted on 16 individuals, concluded that the Turkish population forms a cluster with Southern European and Mediterranean populations and that the predicted contribution from ancestral East Asian populations is 21.7% (presumably reflecting a Central Asian origin). However, that does not provide a direct estimate of a migration rate, because of factors such as the unknown original contributing populations. Given Europeans and Native Americans may share Ancient North Eurasian ancestry, "significant Ancient North Eurasian ancestry might also be found in Turkish genetic profiles; this requires further study".

Another study in 2021, which looked at whole-genomes and whole-exomes of 3,362 unrelated Turkish samples, resulted in establishing the first Turkish variome and found "extensive admixture between Balkan, Caucasus, Middle Eastern, and European populations" in line with history of Turkey. Moreover, significant number of rare genome and exome variants were unique to modern-day Turkish population. Neighbouring populations in East and West, and Tuscan people in Italy were closest to Turkish population in terms of genetic similarity. Central Asian contribution to maternal, paternal, and autosomal genes were detected, consistent with the historical migration and expansion of Oghuz Turks from Central Asia. Central Asian autosomal DNA geneflow was estimated as around 10%. Using haplogroups that are only found in Central Asia, the study estimated Central Asian paternal and maternal contributions. Paternal contribution was estimated as between 8.5% to 15.6% based on C-RPS4Y and O3-M122 Y-chromosome haplogroups. Maternal contributions was estimated as around 8% based on D4c and G2a mtDNA haplogroups. The authors speculated that the genetic similarity of the modern-day Turkish population with modern-day European populations might be due to spread of neolithic Anatolian farmers into Europe, which impacted the genetic makeup of modern-day European populations. Moreover, the study found no clear genetic separation between different regions of Turkey, leading authors to suggest that recent migration events within Turkey resulted in genetic homogenization.

Other studies

A 2001 study that looked at HLA alleles suggested that "Turks, Kurds, Armenians, Iranians, Jews, Lebanese and other (Eastern and Western) Mediterranean groups seem to share a common ancestry" and that historical populations such as Anatolian Hittite and Hurrian groups (older than 2000 B.C.) "may have given rise to present‐day Kurdish, Armenian and Turkish populations." A 2004 study that looked at 11 human‐specific Alu insertion polymorphisms among Aromanians, Macedonians, Albanians, Romanians, Greeks, and Turks, suggested a common ancestry for these populations.

A 2011 study ruled out long-term and continuing genetic contacts between Anatolia and Siberia and confirmed the presence of significant mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome divergence between these regions, with minimal admixture. The research also confirmed the lack of mass migration and suggested that it was irregular punctuated migration events that engendered large-scale shifts in language and culture among Anatolia's diverse autochthonous inhabitants.

A study in 2015, however, wrote, "Previous genetic studies have generally used Turks as representatives of ancient Anatolians. Our results show that Turks are genetically shifted towards Central Asians, a pattern consistent with a history of mixture with populations from this region." The authors found "7.9% (±0.4) East Asian ancestry in Turks from admixture occurring 800 (±170) years ago."

According to a 2012 study of ethnic Turks, "Turkish population has a close genetic similarity to Middle Eastern and European populations and some degree of similarity to South Asian and Central Asian populations." The analysis modeled each person's DNA as having originated from K ancestral populations and varied the parameter K from 2 to 7. At K = 3, comparing to individuals from the Middle East (Druze and Palestinian), Europe (French, Italian, Tuscan and Sardinian) and Central Asia (Uygur, Hazara and Kyrgyz), clustering results indicated that the contributions were 45%, 40% and 15% for the Middle Eastern, European and Central Asian populations, respectively. At K = 4, results for paternal ancestry were 38% European, 35% Middle Eastern, 18% South Asian, and 9% Central Asian. At K = 7, results of paternal ancestry were 77% European, 12% South Asian, 4% Middle Eastern, and 6% Central Asian. However, results may reflect either previous population movements (such as migration and admixture) or genetic drift. The Turkish samples were closest to the Adygei population (Circassians) from the Caucasus; other sampled groups included European (French, Italian), Middle Eastern (Druze, Palestinian), and Central (Kyrgyz, Hazara, Uygur), South Asian (Indian), and East Asian (Mongolian, Han) populations.

A study involving mitochondrial analysis of a Byzantine-era population, whose samples were gathered from excavations in the archaeological site of Sagalassos, found that these samples were closest to modern samples from "Turkey, Crimea, Iran and Italy (Campania and Puglia), Cyprus and the Balkans (Bulgaria, Croatia, and Greece)." Modern-day samples from the nearby town of Ağlasun showed that lineages of East Eurasian descent assigned to macro-haplogroup M were found in the modern samples from Ağlasun. This haplogroup was significantly more frequent in Ağlasun (15%) than in Byzantine Sagalassos, but the study found "no genetic discontinuity across two millennia in the region."

A 2019 study found that Turkish people cluster with Southern and Mediterranean Europe populations along with groups in the northern part of Southwest Asia (such as the populations from Caucasus, Northern Iraq, and Iranians). Another 2019 study found that Turkish people have the lowest fixation index distances with Caucasus population group and Iranian-Syrian group, as compared to East-Central European, European (including Northern and Eastern European), Sardinian, Roma, and Turkmen groups or populations. The Caucasus group in the study included samples from Abkhazians, Adygey, Armenians, Balkars, Chechens, Georgians, Kumyks, Kurds, Lezgins, Nogays, and North Ossetians. A 2022 study, which looked at modern-day populations and more than 700 ancient genomes from Southern Europe and West Asia covering a period of 11,000 years, found that Turkish people carry the genetic legacy of “both ancient people who lived in Anatolia for thousands of years covered by our study and people coming from Central Asia bearing Turkic languages” and that “The genetic contribution of Central Asian Turkic speakers to present-day people can be provisionally estimated by comparison of Central Asian ancestry in present-day Turkish people (~9%) and sampled ancient Central Asians (range of ~41-100%) to be between 9/100 and 9/41 or ~9-22%”.

See also

- Demographics of Turkey

- History of the Turkish people

- Genetic history of East Asians

- Genetic history of the Middle East

- Genetic history of Europe

- Turkification

References and notes

- ^ Alkan C, Kavak P, Somel M, Gokcumen O, Ugurlu S, Saygi C, et al. (November 2014). "Whole genome sequencing of Turkish genomes reveals functional private alleles and impact of genetic interactions with Europe, Asia and Africa". BMC Genomics. 15 (1): 963. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-963. PMC 4236450. PMID 25376095.

- ^ Taskent RO, Gokcumen O (April 2017). "The Multiple Histories of Western Asia: Perspectives from Ancient and Modern Genomes". Human Biology. 89 (2): 107–117. doi:10.13110/humanbiology.89.2.01. PMID 29299965. S2CID 6871226.

- ^ Arnaiz-Villena A, Karin M, Bendikuze N, Gomez-Casado E, Moscoso J, Silvera C, et al. (April 2001). "HLA alleles and haplotypes in the Turkish population: relatedness to Kurds, Armenians and other Mediterraneans". Tissue Antigens. 57 (4): 308–17. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057004308.x. PMID 11380939.

- ^ Cinnioğlu C, King R, Kivisild T, Kalfoğlu E, Atasoy S, Cavalleri GL, et al. (January 2004). "Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia". Human Genetics. 114 (2): 127–48. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4. PMID 14586639. S2CID 10763736.

- ^ Rosser ZH, Zerjal T, Hurles ME, Adojaan M, Alavantic D, Amorim A, et al. (December 2000). "Y-chromosomal diversity in Europe is clinal and influenced primarily by geography, rather than by language". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (6): 1526–43. doi:10.1086/316890. PMC 1287948. PMID 11078479.

- Wells RS, Yuldasheva N, Ruzibakiev R, Underhill PA, Evseeva I, Blue-Smith J, et al. (August 2001). "The Eurasian heartland: a continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (18): 10244–9. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. JSTOR 3056514. PMC 56946. PMID 11526236.

- ^ Schurr TG, Yardumian A (2011). "Who Are the Anatolian Turks?". Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia. 50 (1): 6–42. doi:10.2753/AAE1061-1959500101. S2CID 142580885.

- ^ Pakstis AJ, Gurkan C, Dogan M, Balkaya HE, Dogan S, Neophytou PI, et al. (December 2019). "Genetic relationships of European, Mediterranean, and SW Asian populations using a panel of 55 AISNPs". European Journal of Human Genetics. 27 (12): 1885–1893. doi:10.1038/s41431-019-0466-6. PMC 6871633. PMID 31285530.

- ^ Bánfai Z, Melegh BI, Sümegi K, Hadzsiev K, Miseta A, Kásler M, Melegh B (2019). "Revealing the Genetic Impact of the Ottoman Occupation on Ethnic Groups of East-Central Europe and on the Roma Population of the Area". Frontiers in Genetics. 10: 558. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.00558. PMC 6585392. PMID 31263480.

- ^ Lazaridis I, Alpaslan-Roodenberg S, Acar A, Açıkkol A, Agelarakis A, Aghikyan L; et al. (2022). "A genetic probe into the ancient and medieval history of Southern Europe and West Asia". Science. 377 (6609): 940–951. Bibcode:2022Sci...377..940L. doi:10.1126/science.abq0755. PMC 10019558. PMID 36007020.