| Revision as of 21:44, 21 January 2013 editEtienneDolet (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers27,553 edits added much needed background information← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:56, 10 December 2024 edit undoAlexander the storyteller (talk | contribs)40 editsNo edit summaryTag: Visual edit | ||

| (297 intermediate revisions by 86 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|First constitution of the Ottoman Empire}} | |||

| {{Expand German|Osmanische Verfassung|topic=hist|fa=yes|date=December 2009}} | {{Expand German|Osmanische Verfassung|topic=hist|fa=yes|date=December 2009}} | ||

| {{Refimprove|date=June 2008}} | {{Refimprove|date=June 2008}} | ||

| ] | |||

| The '''Ottoman constitution of 1876''' ({{lang-ota|قانون اساسى}}, "]"; {{lang-tr|{{italics correction|Kanûn-u Esâsî}}}}) was the first ] of the ].<ref>For a modern English translation of the constitution and related laws see, Tilmann J. Röder, The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, in: Grote/Röder, Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries (Oxford University Press 2011).</ref> Written by members of the ], particularly ], during the reign of ] ] (1876–1909), the constitution was only in effect for two years, from 1876 to 1878. | |||

| The '''Constitution of the Ottoman Empire''' ({{langx|ota|قانون أساسي|Kānûn-ı Esâsî|lit=]}}; {{langx|fr|Constitution ottomane}} ; ]: قانون اساسی<!--See below segments on how the French version was the basis of other language versions-->) was in effect from 1876 to 1878 in a period known as the ], and from 1908 to 1922 in the ]. The first and only ] of the ],<ref>For a modern English translation of the constitution and related laws, see Tilmann J. Röder, The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, in: Grote/Röder, Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries (Oxford University Press 2011).</ref> it was written by members of the ], particularly ], during the reign of Sultan ] ({{Reign|1876|1909}}). After Abdul Hamid's political downfall in the ], the Constitution was amended to transfer more power from the sultan and the appointed ] to the popularly-elected lower house: the ]. | |||

| In the course of their studies in Europe, some members of the new Ottoman elite concluded that the secret of Europe's success rested not only with its technical achievements but also with its political organizations. Moreover, the process of reform itself had imbued a small segment of the elite with the belief that constitutional government would be a desirable check on autocracy and provide it with a better opportunity to influence policy. Sultan ]'s chaotic rule led to his deposition in 1876 and, after a few troubled months, to the proclamation of an Ottoman constitution that the new sultan, Abdul Hamid II, pledged to uphold.<ref>{{cite book|last=Cleveland|first=William|title=A History of the Modern Middle East|year=2013|publisher=Westview Press|location=Boulder, Colorado|isbn=978-0813340487|page=|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/historyofmodernm00will/page/79}}</ref> | |||

| The major reason for the introduction of the Constitution was Midhat Pasha’s recognition of the need for reform and a check on the power of the Sultan. However, the Constitution that was put in place certainly{{according to whom|date=November 2011}} represented a certain limitation of the ] of the monarch, although Abdulhamid could still imprison or send to exile people who he considered harmful to the state, or to his emerging absolute rule, in spite of the opening of the first parliament. Although the rules in the Constitution had been twisted{{according to whom|date=November 2011}} to suit Abdulhamid’s needs, it was suspended in 1878 and those who created it were exiled. Midhat Pasha died in exile in Taif. | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| The Ottoman Constitution was introduced after a series of reforms were promulgated in 1839 during the ] era. The goal of the Tanzimat era was to reform the Ottoman |

The Ottoman Constitution was introduced after a series of reforms were promulgated in 1839 during the ] era. The goal of the Tanzimat era was to reform the Ottoman Empire under the auspices of Westernization.<ref>Cleveland, William L & Bunton, Martin (2009). ''A History of the Modern Middle East'' (4th ed.). Westview Press. p. 82.</ref> In the context of the reforms, Western-educated Armenians of the Ottoman Empire drafted the ] in 1863.<ref name=Joseph>{{cite book|last=Joseph|first=John|title=Muslim-christian relations & inter-christian rivalries in the middle east: the case of the Jacobites|year=1983|publisher=Suny Press|location=|isbn=9780873956000|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lKaL3_dfFJAC|access-date=21 January 2013|page=81}}</ref> The Ottoman Constitution of 1876 was under direct influence of the Armenian National Constitution and its authors.<ref name=Davison>{{cite book|last=H. Davison|first=Roderic|title=Reform in the Ottoman Empire, 1856–1876|year=1973|publisher=Gordian Press|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PeNpAAAAMAAJ|edition=2, reprint|access-date=21 January 2013|page=134|isbn=9780877521358 |quote=But it can be shown that Midhat Pasa, the principal author of the 1876 constitution, was directly influenced by the Armenians.}}</ref> The Ottoman Constitution of 1876 itself was drawn up by Western-educated ] ], who was the advisor of ].<ref name=Davison /><ref>{{cite book|title=United States Congressional serial set, Issue 7671|year=1920|publisher=United States Senate: 66th Congress. 2nd session.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vK43AQAAIAAJ|edition=Volume|access-date=21 January 2013|page=6|quote=In 1876 a constitution for Turkey was drawn up by the Armenian Krikor Odian, secretary to Midhat Pasha the reformer, and was proclaimed and almost immediately revoked by Sultan Abdul Hamid}}</ref><ref>Bertrand Bereilles. "La Diplomatie turco-phanarote". Introduction to ''Rapport secret de Karatheodory Pacha sur le Congrès de Berlin, Paris, 1919'', p. 25. Quote translated from French: "The majority of the government officials in the Ottoman Empire selected a Greek or an Armenian as their advisor in reform." The author mentions two names amongst these "advisors", Dr. Serop Vitchenian, who was the adviser to Fuad Pasha, and Grigor Odian, deputy to Midhat Pasha, who is the author of the Ottoman constitution of 1876.</ref> | ||

| Attempts at reform within the empire had long been made. Under the reign of Sultan ], there was a vision of actual reform. Selim tried to address the military's failure to effectively function in battle; even the basics of fighting were lacking, and military leaders lacked the ability to command. Eventually his efforts led to his assassination by the ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Devereux|first=Robert|title=The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament|year=1963|publisher=The Johns Hopkins Press|location=Baltimore|page=22}}</ref> This action soon led to ] becoming Sultan. Mahmud can be considered the "first real Ottoman reformer",<ref name="Devereux, Robert 1963, p. 22">Devereux, Robert (1963). ''The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament''. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 22.</ref> since he took a substantive stand against the janissaries by removing them as an obstacle in the ].<ref name="Devereux, Robert 1963, p. 22"/> | |||

| This led to what was known as the Tanzimat, which lasted from 1839 to 1876. This era was defined as an effort of reform to distribute power from the Sultan (even trying to remove his efforts) to the newly formed government led by a parliament. These were the intentions of the ], which included the newly formed government.<ref name="Devereux, Robert 1963, p. 21">Devereux, Robert (1963). ''The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament''. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 21</ref> The purpose of the Tanzimat era was reform, but mainly, to divert power from the Sultan to the Sublime Porte. The first indefinable act of the Tanzimat period was when Sultan ] issued the ].<ref>Devereux, Robert (1963). ''The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament''. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 25</ref> This document or statement expressed the principles that the liberal statesmen wanted to become an actual reality. The Tanzimat politicians wanted to prevent the empire from falling completely into ruin. | |||

| During this time the Tanzimat had three different sultans: ] (1839–1861), ] (1861–1876), and ] (who only lasted three months in 1876).<ref>{{cite book|last=Findley|first=Carter V.| title= Bureaucratic Reform in the Ottoman Empire: The Sublime Porte 1789–1922|url=https://archive.org/details/bureaucraticrefo00find|url-access=limited|year=1980|publisher=Princeton University Press|location=Princeton, New Jersey|page=|isbn=9780691052885 }}</ref> During the Tanzimat period, the man from the Ottoman Empire with the most respect in Europe was Midhat Pasha.<ref name="Devereux, Robert 1963, p. 30">Devereux, Robert (1963). ''The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament''. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 30</ref> Midhat dreamed of an Empire in which "there would be neither Muslim nor non-Muslim but only Ottomans".<ref name="Devereux, Robert 1963, p. 30" /> Such ideology led to the formation of groups such as the ] and the ] (who merged with the Ottoman Unity Society).{{Citation needed|date=December 2021}} These movements attempted to bring about real reform not by means of edicts and promises, but by concrete action.{{fact|date=September 2019}} Even after Abdulhamid II suspended the constitution, it was still printed in the {{lang|ota-Latn|salname}}, or yearbooks made by the Ottoman government.<ref name=StraussConstp32>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire", p. 32.</ref> | |||

| Johann Strauss, author of "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the ''Kanun-ı Esasi'' and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages", wrote that the ] and the ] "seem to have influenced the Ottoman Constitution".<ref name=StraussConstp36>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire", p. 36.</ref> | |||

| ==Aim== | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| The Ottoman Porte believed that once the Christian population was represented in the legislative assembly, no foreign power could legitimize the promotion of her national interests under pretext of representing the rights of these people of religious and ethnic bonds. In particular, if successfully implemented, it was thought that it would rob Russia of any such claims.<ref>Berkes, Niyazi. ''The Development of Secularism in Turkey''. Montreal: McGill University Press, 1964. pp. 224–225</ref> However, its potential was never realized and the tensions with the Russian Empire culminated in the ]. | |||

| ==Framework== | ==Framework== | ||

| ] in 1877]] | |||

| The Constitution proposed a parliament divided into two parts: The senators were elected by the Sultan, and the Chamber of Deputies was elected by the people, although not directly (they chose delegates who would then choose the Deputies). There were also elections held every four years to keep the parliament changing and to continually express the voice of the people. This same framework carried over from the Constitution as it was in 1876 until it was reinstated in 1908. | |||

| After Sultan ] was removed from office, ] became the new Sultan. ] was afraid that Abdul Hamid II would go against his progressive visions; consequently he had an interview with him to assess his personality and to determine if he was on board.<ref>Devereux, Robert (1963). ''The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament''. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 43</ref> The Constitution proposed a bicameral parliament, the ], consisting of the Sultan-selected ] and the generally elected ] (although not directly; the populace chose delegates who would then choose the Deputies). There were also elections held every four years to keep the parliament changing and to continually express the voice of the people. This same framework carried over from the Constitution as it was in 1876 until it was reinstated in 1908. All in all the framework on the Constitution did little to limit the Sultan's power. Some of the retained powers of the Sultan were: declaration of war, appointment of new ministers, and approval of legislation.<ref>''A history of the Modern Middle East'', Cleveland and Bunton, p. 79</ref> | |||

| ==Implementation== | |||

| Although talks about the implementation of a constitution were in place during the rule of ], they did not come to fruition.<ref name="Berkes, Niyazi 1964. pp. 224-225">Berkes, Niyazi. The Development of Secularism in Turkey.Montreal: McGill University Press, 1964. pp. 224-225,242-243, 248-249.</ref> A secret meeting between ], the main author of the constitution, and ], the brother of the sultan, was arranged in which it was agreed that a constitution would be drafted and promulgated immediately after ] came to the throne.<ref>No reliable information is available on this meeting, although the following source can be consulted with caution: Celaleddin, Mir'at-i Hakikat, I, pp. 168.</ref> Following this agreement, ] was deposed on 1876 by a ] on the grounds of insanity. | |||

| A committee of 24 (later 28) people, led by ], was formed to work on the new constitution. They submitted the first draft on 13 November 1876 which was obstreperously rejected by ]'s ministers on the grounds of the abolishment of the office of the ].<ref name="Berkes, Niyazi 1964. pp. 224-225"/> After strenuous debates, a constitution acceptable to all sides was established and the constitution was signed by ] on the morning of December 13, 1876. | |||

| ===Language versions=== | |||

| According to Strauss, the authorities seemed to have had prepared multiple language versions of the constitution at the same time prior to release as their publication year was 1876: he stated that such release "apparently occurred simultaneously".<ref name=StraussConstp32/> They were officially published in various newspapers, owned by their respective publishers, according to language, and there were other publications that re-printed them.<ref name=StraussConstp34>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 34 (PDF p. 36/338).</ref> | |||

| Strauss divides the translations into "Oriental-style" versions - ones made for adherents of Islam, and "Western-style" versions - ones made for Christian and Jewish people, including Ottoman citizens and foreigners residing in the empire.<ref name=StraussConstp50>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 50 (PDF p. 52/338).</ref> | |||

| ====Versions for Muslims==== | |||

| ] | |||

| The constitution was originally made in Ottoman Turkish with a Perso-Arabic script.<!--Doesn't need a source as it's obvious--> The Ottoman government printed it, as did printing presses from private individuals.<ref name=StraussConstp32/> | |||

| There are a total of ten Turkish terms, and the document instead relies on words from Arabic, which Strauss argues is "excessive".<ref name=StraussConstp35/> In addition, he stated that other defining aspects include "convoluted sentences typical of Ottoman chancery style", ], and a "deferential indirect style" using ].<ref name=StraussConstp35/> Therefore Strauss wrote that due to its complexity, "A satisfactory translation into Western languages is difficult, if not impossible."<ref name=StraussConstp35/> Max Bilal Heidelberger wrote a direct translation of the Ottoman Turkish version and published it in a book chapter by Tilmann J Röder, "The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives."<!--See below--> | |||

| A Latin script rendition of the Ottoman Turkish appeared in 1957, in the ], in ''Sened-i İttifaktan Günümüze Türk Anayasa Metinleri'', edited by Suna Kili and A. Şeref Gözübüyük and published by ].<ref name=StraussConstp32/> | |||

| In addition to the original Ottoman Turkish, the document had been translated into Arabic and Persian. Language versions for Muslims were derived from the Ottoman Turkish version,<ref name=StraussLangPT193>{{cite book|author=Strauss, Johann|chapter=Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire|editor=Murphey, Rhoads|title=Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean: Recording the Imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Rule|publisher=]|date=2016-07-07|isbn=9781317118442|page=}} Page from ]. In Chapter no. 7. Volume 18 of Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies. Old {{ISBN|1317118448}}.</ref> and Strauss wrote that the vocabularies of the Ottoman Turkish, Arabic, and Persian versions were "almost identical".<ref name=StraussConstp49>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 49 (PDF p. 51/338).</ref> Despite the Western concepts in the Ottoman Constitution, Strauss stated that "The official French version does not give the impression that the Ottoman text is a translation of it."<ref name=StraussConstp35>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 35 (PDF p. 37/338).</ref> | |||

| The Arabic version was published in '']''.<ref name=StraussConstp34/> Strauss, who also wrote "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," stated that the terminology used in the Arabic version "stuck almost slavishly" to that of the Ottoman Turkish,<ref name=StraussLangPT193/> with Arabic itself "almost exclusively" being the source of the terminology; as newer Arabic words were replacing older ones used by Ottoman Turkish, Strauss argued that this closeness "is more surprising" compared to the closeness of the Persian version to the Ottoman original, and that the deliberate closeness to the "Ottoman text is significant, but it is difficult to find a satisfactory explanation for this practice."<ref name=StraussConstp50/> | |||

| From 17 January 1877 a Persian version appeared in '']''.<ref name=StraussConstp34/> Strauss stated that the closeness of the Persian text to the Ottoman original was not very surprising as Persian adopted Arabic-origin Ottoman Turkish words related to politics.<ref name=StraussConstp50/> | |||

| ====Versions for non-Muslim minorities==== | |||

| ]'' Volume 5)]] | |||

| Versions for non-Muslims included those in ], ], ], and ] (Ladino).<ref name=StraussLangPT193/> There was also a version in ], Turkish written in the ].<ref name=StraussConstp33>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 33 (PDF p. 35/338).</ref> These versions were respectively printed in '']'', '']'', '']'', ], and '']''.<ref name=StraussConstp34/> | |||

| Strauss stated that versions for languages used by non-Muslims were based on the French version,<ref name=StraussLangPT193/> being the "model and the source of the terminology".<ref name=StraussConstp51>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 51 (PDF p. 53/338).</ref> Strauss pointed to the fact that ] and other linguistic features in Ottoman Turkish were usually not present in these versions.<ref name=StraussConstp35/> In addition each language version has language-specific terminology that is used in place of some terms from Ottoman Turkish.<ref name=StraussConstp41>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 41 (PDF p. 43/338).</ref> Different versions either heavily used foreign terminology or used their own languages' terminologies heavily but they generally avoided using the Ottoman Turkish one; some common French-derived Ottoman terms were replaced with other words.<ref name=StraussConstp5051>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 50-51 (PDF p. 52-53/338).</ref> Based on the differences between the versions for non-Muslims and the Ottoman Turkish version, Strauss concluded that "foreign influences and national traditions – or even aspirations" shaped the non-Muslim versions,<ref name=StraussConstp50/> and that they "reflect religious, ideological | |||

| and other divisions existing in the Ottoman Empire."<ref name=StraussConstp51/> | |||

| Since the Armenian version, which Strauss describes as "puristic", uses Ottoman terminology not found in the French version and on some occasions in lieu of native Armenian terms, Strauss described it as having "taken into account the Ottoman text".<ref name=StraussConstp47>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 47 (PDF p. 49/338).</ref> The publication ''Bazmavep'' ("Polyhistore") re-printed the Armenian version.<ref name=StraussConstp34/> | |||

| The Bulgarian version was re-printed in four other newspapers: '']'', '']'', ''Napredŭk''<!--Former from another Strauss article: "Twenty Years in the Ottoman capital: the memoirs of Dr. Hristo Tanev Stambolski of Kazanlik (1843-1932) from an Ottoman point of view."--> or ''Napredǎk'' ("Progress")<!--Latter from "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the ''Kanun-ı Esasi'' and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages" p. 34--> and ''Zornitsa'' ("Morning Star").<ref name=StraussTwentyp267>Strauss, Johann. "Twenty Years in the Ottoman capital: the memoirs of Dr. Hristo Tanev Stambolski of Kazanlik (1843-1932) from an Ottoman point of view." In: Herzog, Christoph and Richard Wittmann (editors). ''Istanbul - Kushta - Constantinople: Narratives of Identity in the Ottoman Capital, 1830-1930''. ], 10 October 2018. {{ISBN|1351805223}}, 9781351805223. p. 267.</ref> Strauss wrote that the Bulgarian version "corresponds exactly to the French version"; the title page of the copy in the collection of Christo S. Arnaudov<!--Identified on p. 31 of source--> ({{langx|bg|Христо С. Арнаудовъ}}<!--Note the name on the page is "Христа С. Арнаудова" as it is the ]/] case of the name "Христо С. Арнаудовъ", as in " от Христа С. Арнаудова" ("by Hristo S. Arnaudov")-->; Post-1945 spelling: Христо С. Арнаудов) stated that the work was translated from Ottoman Turkish, but Strauss said this is not the case.<ref name=StraussConstp48>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 46 (PDF p. 50/338).</ref> | |||

| Strauss stated that the Greek version "follows the French translation" while adding Ottoman synonyms of Greek terminology and Greek synonyms of Ottoman terminology.<ref name=StraussConstp46/> | |||

| Strauss wrote that "perhaps the Judaeo-Spanish – version may have been checked against the original Ottoman text".<ref name=StraussConstp51/> | |||

| Strauss also wrote "There must have also been a ] version available in <nowiki>]<nowiki>]</nowiki>".<ref name=StraussConstp34/> Arsenije Zdravković published a Serbian translation after the ].<ref name=StraussConstp34/> | |||

| ====Versions for foreigners==== | |||

| There were versions made in French and English. The former was intended for diplomats and was created by the Translation Office (''Terceme odası'').<ref name=StraussConstp33/> Strauss stated that a draft copy of the French version had not been located and there is no evidence that states that one had ever been made.<ref name=StraussConstp35/> The French version has some terminology originating from Ottoman Turkish.<ref name=StraussConstp38>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the ''Kanun-ı Esasi'' and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages," p. 38 (PDF p. 40/338).</ref> | |||

| A 1908 issue of the '']'' printed an Ottoman-produced English version but did not specify its origin.<ref name=StraussConstp33/> After analysing a passage from it, Strauss concluded "Clearly, the “contemporary English version” was also translated from the French version."<ref name=StraussConstp46>Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the ''Kanun-ı Esasi'' and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages," p. 46 (PDF p. 48/338).</ref>{{#tag:ref|For a scientific English translation directly from the Ottoman Turkish version of the constitution, done by Max Bilal Heidelberger,<!--Credited in footnote 109--> see below. It originates from the copy published in the '']'' (Ottoman Official Gazette) 1st series (''tertïb-i evvel''), Volume 4, Pages 4-20. | |||

| : {{cite book|author=Röder, Tilmann J.|chapter=The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives|editor=Grote, Rainer|editor2=Tilmann J. Röder|title=Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries|publisher=]|date=2012-01-11|isbn=9780199759880|pages=-}} - Old {{ISBN|019975988X}} | |||

| The article includes the following documents in "Annex: Constitutional Documents from the Ottoman and Iranian Empires": | |||

| *"The Basic Law of the Ottoman Empire of December 23, 1876"; p. - | |||

| ;"B. Revisions of the Basic Law" - Start p. | |||

| *Law No. 130 on the Revision of Some Articles of the Basic Law of 7th Zi’lhijjeh 1293 (5th Sha’ban 1327 / August 8, 1909) | |||

| *Law No. 318 Revising the Articles 7, 35, and 43 Revised on 5th Sha’ban 1327 (2nd Rejeb 1332 – May 15, 1914) | |||

| *Law No. 80 Revising the Article 102 of the Basic Law of the 7th Zi’lhijjeh 1293 and the Articles 7 and 43 Revised on 2nd Rejeb 1332 (26th Rebi’ü-’l-Evvel 1333 – January 29, 1914) | |||

| *Law No. 307 Revising the Revision of Article 76 of 5th Sha’ban 1327 (4th Jumada-‘l-Ula 1334 – February 25, 1916) | |||

| *Law on the Revision of the Revised Art. 7 of the Basic Law of 26th Rebi’ü-’l-Evvel 1333 and the Deletion of the Revised Art. 35 of 2nd Rejeb 1332 (4th Jumada-‘l-Ula 1334 – February 25, 1916) | |||

| *Law No. 370 Revising Article 72 of the Basic Law of 7th Zi’lhijjeh 1293 (15th Jumada-‘l-Ula 1334 – March 7, 1916); Law No 102 Revising Art. 69 of the Basic Law (8th Jumada-‘l-Ula 1334 – March 21, 1918). | |||

| The translation in ''Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries'' does not include the edict of ] to ], which was from ''Düstūr'' 1st Series, Volume 4, Pages 2-3.<!--This is literally stated as such on p. -->|group=note}} | |||

| Strauss wrote "I have not come across a Russian translation of the ''Kanun-i esasi''. But it is highly probable that it existed."<ref name=StraussConstp48/> | |||

| ===Terminology=== | |||

| Versions in several languages for Christians and Jews used variants of the word "constitution": ''konstitutsiya'' in Bulgarian, σύνταγμα (''syntagma'') in Greek, ''konstitusyon'' in Judaeo-Spanish, and ''ustav'' in Serbian. The Bulgarian version used a term in Russian, the Greek version used a ] from the French word "constitution", the Judaeo-Spanish derived its term from the French, and the Serbian version used a word from ].<ref name=StraussConstp34/> The Armenian version uses the word ''sahmanadrut‘iwn'' (also ''Sahmanatrov;ivn'', {{langx|hyw|սահմանադրութիւն}}; Eastern style: {{langx|hy|սահմանադրություն}}).<ref name=StraussConstp35/> | |||

| Those in Ottoman Turkish, Arabic, and Persian used a word meaning "]", ''Kanun-i esasi'' in Turkish, ''al-qānūn al-asāsī'' in Arabic, and ''qānūn-e asāsī'' in Persian. Strauss stated that the Perso-Arabic term is closer in meaning to "]".<ref name=StraussConstp34/> | |||

| ==European influence== | |||

| As European power increased over the 18th century, the Ottomans saw a lack of progress themselves.<ref name="Devereux, Robert 1963, p. 21"/> In the ], the Ottomans were now considered part of the European world. This was the beginning of intervention by Europeans (i.e. the ] and ]) in the Ottoman Empire. One of the reasons they were taking a step into Ottoman territory was for the protection of ]. There had been perennial conflict between Muslims and non-Muslims in the Empire.<ref>Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 24</ref> This was the focal point for the Russians to interfere, and the Russians were perhaps the Ottomans' most disliked enemy. The Russians looked for many ways to become involved in political affairs especially when unrest in the Empire reached their borders. The ] was long, for many different reasons. The Ottomans saw the Russians as their most fierce enemy and not one to be trusted. | |||

| ==Domestic and foreign reactions== | |||

| Reactions within the Empire and around Europe were both widely acceptable and potentially a cause for some concern. Before the Constitution was enacted and made official, many of the ] were against it because they deemed it to be going against the Shari'a.<ref>Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 45</ref> However, throughout the Ottoman Empire, the people were extremely happy and looking forward to life under this new regime.<ref>Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 82</ref> Many people celebrated and joined in Muslim-Christian relations which formed, and there now seemed to be a new national identity: Ottoman.<ref>Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 84</ref> However many provinces and people within the Empire were against it<ref>{{Cite news |date=January 26, 1877 |title=Egypt |work=The Times (London, England) |url=https://go.gale.com/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=Newspapers&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&retrievalId=f1ad09a7-aedf-4755-9dd7-21d95373d78f&hitCount=73&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm¤tPosition=59&docId=GALE%7CCS50509882&docType=Article&sort=Pub+Date+Forward+Chron&contentSegment=ZTMA-MOD1&prodId=TTDA&pageNum=3&contentSet=GALE%7CCS50509882&searchId=R5&userGroupName=tall85761&inPS=true |access-date=April 18, 2023}}</ref> and many acted out their displeasure in violence. Some Muslims agreed with the Ulema that the constitution violated Shari'a law. Some acted out their protests by attacking a priest during mass.<ref name="Devereux, Robert 1963, p. 85">Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 85</ref> Some of the provinces referred to in the constitution were alarmed, such as Rumania, Scutari and Albania, because they thought it referred to them having a different change of government or no longer being autonomous from the Empire.<ref name="Devereux, Robert 1963, p. 85"/> | |||

| Yet the most important reaction, only second to that of the people, was that of the Europeans. Their reactions were quite to the contrary from the people; in fact they were completely against it—so much so that the United Kingdom was against supporting the Sublime Porte and criticized their actions as reckless.<ref>Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 87</ref> Many across European saw this constitution as unfit or a last attempt to save the Empire. In fact only two small nations were in favor of the constitution but only because they disliked the Russians as well. Others considered the Ottomans to be grasping for straws in trying to save the Empire; they also labeled it as a fluke of the Sublime Porte and the Sultan.<ref>Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 88</ref> | |||

| ==Initial suspension of the constitution== | |||

| After the Ottomans were defeated in the ] a truce was signed on 31 January 1878 in ]. Fourteen days after this event, on February 14, 1878, ] took the opportunity to prorogue the parliament, citing social unrest.<ref>Gottfried Plagemann: Von Allahs Gesetz zur Modernisierung per Gesetz. Gesetz und Gesetzgebung im Osmanischen Reich und der Republik Türkei. Lit Verlag</ref> This allowed him to avoid new elections. ], increasingly withdrawn from society to the ], was therefore able rule the most part of three decades in an absolutist manner.<ref name="Jean Deny 2002, pp. 64-65">Cf. Jean Deny: 'Abd al-Ḥamīd. In: The Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 2, Brill, Leiden 2002, pp. 64-65.</ref> | |||

| ==Second Constitutional Era== | ==Second Constitutional Era== | ||

| {{Main|Second Constitutional Era}} | |||

| The Constitution was put back into effect in 1908 as Abdulhamid came under pressure, particularly from some of his military leaders. Abdulhamid’s fall came as a result of the Young Turk revolution, and these Young Turks put the Constitution back into effect. The second constitutional period spanned from 1908 until after World War I when the Ottoman Empire was dissolved. Political groups and parties were formed during this period, including the CUP (Committee of Union and Progress). | |||

| The Constitution was put back into effect in 1908 as ] came under pressure, particularly from some of his military leaders. ]'s fall came as a result of the 1908 ], and the ] put the 1876 constitution back into effect. The ] spanned from 1908 until after World War I when the Ottoman Empire was dissolved. Many ] were formed during this period, including the ] (CUP). | |||

| == |

==Final Suspension of the Constitution== | ||

| On 20 January 1920, the ] met and ratified the ]. However, since this document did not clearly state whether the Ottoman Constitution of 1876 was superseded, consequentially, only provisions contradictory to the ] became null and void (]).<ref>{{cite book|last=Gözler|first=Kemal| title= Türk Anayasa Hukukuna Giriş|year=2008|publisher=Ekin Kitabevi|location=Bursa|page=32}}</ref> The rest of the constitution resumed its implementation up until 20 April 1924, when both the Constitutions of 1876 and 1921 were replaced by an entirely new document, the ]. | |||

| The Ottoman Constitution represented more than the immediate effect it had on the country. It originally represented the country’s willingness to change and grow, even partially westernize. The liberal thinking and intellectualism that came along with the creation of the Constitution were new to the Ottoman Empire and represented a new, progressive generation of Ottomans. Despite its original failure, the Constitution did show some positives. It allowed the leadership to slowly transform from an authoritarian to a more democratic system, which included political parties and elections. These had to an extent dissolved the authoritarianism, although a form of military dictatorship ensued after the Constitution was reenacted. | |||

| ==Significance of the constitution== | |||

| The Ottoman Constitution represented more than the immediate effect it had on the country. It was extremely significant because it made all subjects Ottomans under the law. By doing so, everyone, regardless of their religion had the right to liberties such as freedom of press and free education. Despite the latitude it gave to the sovereign, the constitution provided clear evidence of the extent to which European influences operated among a section of the Ottoman bureaucracy. This showed the effects of the pressure from Europeans on the issue of discrimination of religious minorities within the Ottoman Empire, although, Islam was still the recognized religion of the state.<ref>Boğaziçi University, Atatürk Institute of Modern Turkish History</ref> The constitution also reaffirmed the equality of all Ottoman subjects, including their right to serve in the new ]. The constitution was more than a political document; it was a proclamation of ] and Ottoman patriotism, and it was an assertion that the empire was capable of resolving its problems and that it had the right to remain intact as it then existed. It officially established the subjects of the Empire as "Ottomans," with the Sultan being titled "] and Sovereign of all Ottomans," rather than "of the Turks." The Ottoman Constitution of 1876 was preceded by the Nationality Law of 1869,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hanley |first=Will |date=2016 |title=What Ottoman Nationality Was and Was Not |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/jottturstuass.3.2.05 |journal=Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association |volume=3 |issue=2 |pages=277–298 |doi=10.2979/jottturstuass.3.2.05 |issn=2376-0699}}</ref> which created a common and equal citizenship for all Ottomans, regardless of race or religion. The constitution built upon those ideas and expanded on them, well focusing on keep the state together.<ref>Cleveland, William (2013). A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 77. {{ISBN|0813340489}}.</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Cleveland|first=William|title=A History of the Modern Middle East|year=2013|publisher=Westview Press|location=Boulder, Colorado|isbn=978-0813340487|pages=|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/historyofmodernm00will/page/79}}</ref> | |||

| Ultimately, although the constitution created an elected chamber of deputies and an appointed senate, it only placed minimal restriction on the Sultan's power. Under the constitution, the Sultan retained the power to declare war and make peace, to appoint and dismiss ministers, to approve legislation, and to convene and dismiss the chamber of deputies.<ref>Cleveland, William L & Martin Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East: 4th Edition, Westview Press: 2009, p. 79.</ref> | |||

| The sultan remained the theocratic legitimized sovereign to which the state organization was made-to-measure. Thus, despite a de jure intact constitution, the sultan ruled in the absolutist manner.<ref name="Jean Deny 2002, pp. 64-65"/> This was particularly evident in the closure of Parliament only eleven months after the declaration of the Constitution. Although the basic rights guaranteed in the constitution were not at all insignificant in Ottoman legal history, they were severely limited by the pronouncements of the ruler. Instead of overcoming sectarian divisions through the institution of universal representation, the elections reinforced the communitarian basis of society by allotting quotas to the various religious communities based on projections of population figures derived from the ]. Furthermore, in order to appease the European powers, the Ottoman administration drafted an exceedingly uneven representational scheme that favored the European provinces by an average 2:1 ratio.<ref>{{cite book|last=Hanioglu|first=Sukru|title=A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire|year=2010|publisher=Princeton University Press|pages=118–119}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ==Notes== | |||

| ==References and notes== | |||

| {{reflist|group=note}} | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Strauss |first=Johann|url=https://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/menalib/download/pdf/2734659?originalFilename=true |year=2010 |chapter=A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the ''Kanun-ı Esasi'' and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages | editor=Herzog, Christoph|editor2=Malek Sharif|title= The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy|publisher=] |publication-place= ]|pages= 21–51 }} ( at ]) | |||

| ===Reference notes=== | |||

| {{Reflist|3}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Koçunyan, Aylin|chapter=The Transcultural Dimension of the Ottoman Constitution|editor=Firges, Pascal|editor2=Tobias Graf|editor3=Christian Roth|editor4=Gülay Tulasoğlu|title=Well-Connected Domains: Towards an Entangled Ottoman History|publisher=]|date=2014-06-16|pages=235–258 |isbn=9789004274686|doi=10.1163/9789004274686_015|url=https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004274686/B9789004274686-s015.xml?crawler=true}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|author=Korkut, Huseyin|title=Critical Analysis of the Ottoman Constitution (1876) |url=http://epiphany.ius.edu.ba/index.php/epiphany/article/download/219/162|journal=]|volume=9|issue=1|year=2016|pages=114–123|doi=10.21533/epiphany.v9i1.219 |doi-access=free}} - author is of ] | |||

| * {{cite journal|author=Marcou, Jean|url=https://journals.openedition.org/ema/1054|title=Turquie : la constitutionnalisation inachevée|journal=]|volume=2|year=2005|issue=2 |doi=10.4000/ema.1054|pages=53–73|language=fr|doi-access=free}} - Updated online 8 July 2008 | |||

| ; Publications of the constitution in print:<!--From https://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/menalib/download/pdf/2734659?originalFilename=true beginning on p. 32 or PDF p. 34)--> | |||

| * Perso-Arabic Ottoman Turkish: {{cite book|title=Kanun-i esasi|year=1876|publisher=Matbaa-i amire|place=Constantinople}} (Ottoman year: 1292) | |||

| * Latin script Ottoman Turkish: {{cite book|editor=Kili, Suna|editor2=A. Şeref Gözübüyük|title=Sened-i İttifaktan Günümüze Türk Anayasa Metinleri|year=1957|publisher=Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları|place=Ankara|pages=31–44|edition=1}} - There are reprints | |||

| * Official French: {{cite book|title=Constitution ottomane promulguée le 7 Zilhidjé 1294 (11/23 décembre 1876)|date=1876-12-23|publisher=Typographie et Lithographie centrales}} - Julian date 11 December 1876 | |||

| ** Second print: {{cite book|title=Constitution ottomane promulguée le 7 Zilhidjé 1294 (11/23 décembre 1876) Rescrit (Hatt) de S.M.I. le Sultan|publisher=Loeffler|place=Constantinople}} - Year may be 1876, but Strauss is uncertain<!--See Strauss Constitution p. 33 (PDF p. 35)--> | |||

| * Armeno-Turkish {{cite book|title=Kanunu esasi memaliki devleti osmaniye|year=1876|publisher=]|place=Constantinople}} | |||

| * Bulgarian: {{cite book|title=ОТТОМАНСКАТА КОНСТИТУЩЯ, ПРОВЪЗГЛАСЕНА на 7 зилхидже 1293 (<sub>11</sub>/<sup>23</sup> Декемврш 1876) (Otomanskata konstitutsiya, provŭzglasena na 7 zilhidže 1293 (11/23 dekemvrii 1876))|year=1876|publisher=]|place=Constantinople}} | |||

| * Greek: {{cite book|title= Оθωμανικόν Σύνταγμα ανακηρυχθέν τη 7 Ζιλχιτζέ 1293 (11/23 δεκεμβρίου 1876) (Othōmanikon Syntagma anakērychthen tē 7 Zilchitze 1293 (11/23 dekemvriou 1876)|year=1876|publisher=Typographion “Vyzantidos”|place=Constantinople}} | |||

| * Arabic: {{cite book|title=Tarjamat al-khaṭṭ ash-sharīf as-sulṭānī wa l-Qānūn al-asāsī|publisher=Al-Jawāʾib Press|place=Constantinople}} - Islamic year 1293, circa 1876 Gregorian | |||

| * Armenian: {{cite book|title=սահմանադրութիւն Օսմանյան պետութիւն (Sahmanadrut'iwun Ôsmanean Petut'ean)|year=1877|publisher=]|place=Istanbul}} | |||

| * Judaeo-Spanish: {{cite book|title=Konstitusyon del Imperio otomano proklamada el 7 zilhidje 1283 (7 Tevet 5637)|year=1877|publisher=Estamparia De Castro en Galata<!--Spelling from p. 40--><!--Also De Castro Press-->|place=Constantinople}} - Hebrew calendar 5637 | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Wikisource|Ottoman constitution of 1876}} | |||

| {{Commons category}} | |||

| *{{cite web|url=https://anayasa.tbmm.gov.tr/1876.aspx|title=1876 KANUN-I ESASİ|publisher=]|language=tr|access-date=2019-09-10|archive-date=2017-06-09|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170609185723/https://anayasa.tbmm.gov.tr/1876.aspx|url-status=dead}} - About the constitution | |||

| * | * | ||

| ; Copies of the constitution | |||

| * | |||

| * English translations: | |||

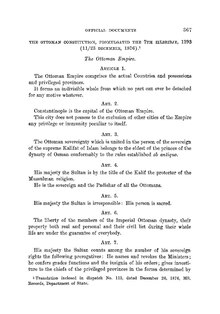

| ** {{cite journal|url=https://archive.org/details/jstor-2212668|title=The Ottoman Constitution, Promulgated the 7th Zilbridje, 1293 (11/23 December, 1876)|date=1908-10-01|journal=]|publisher=]|volume=2|issue=4 (Supplement: Official Documents (Oct., 1908))|pages=367–387|jstor=2212668|doi=10.2307/2212668|s2cid=246006581 }}<!--Note that this translation is public domain--> - Translation inclosed in dispatch No. 113 in the MS. Records, ], dated December 26, 1876<!--Wording from: https://ia801700.us.archive.org/35/items/jstor-2212668/2212668.pdf--> () | |||

| ** , including the "Tanzimat Fermani -- The Rescript of Gülhane – Gülhane Hatt-i Hümayunu 3 November 1839", at ] | |||

| ** - Translation posted by the Atatürk Institute of Modern Turkish History of ], identity of the translator not stated. .<!--Note that this translation may be copyrighted--> ] | |||

| * (basis of translation into languages used by Muslims)- at the website of the ] ( (Ankara, 1982) with ) | |||

| * French translation (the basis of translation into non-Muslim languages)<!--From sourced text above, from | |||

| *{{cite book|author=Strauss, Johann|chapter=Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire|editor=Murphey, Rhoads|title=Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean: Recording the Imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Rule|publisher=]|date=2016-07-07|isbn=9781317118442|page=}} Page from ]. In Chapter no. 7. Volume 18 of Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies. Old {{ISBN|1317118448}}. | |||

| --> published in: | |||

| ** Annotated version: {{cite book|author=Ubicini, Abdolonyme|author-link=Abdolonyme Ubicini|url=https://archive.org/details/sc_0001068641_00000001364801/page/n10|title=La constitution ottomane du 7 zilhidjé 1293 (23 décembre 1876) Expliquée et Annotée par A. Ubicini |year=1877|place=Paris|publisher=A. Cotillon et C<sup>o.</sup>}} - | |||

| ** {{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/documentsdiplom10trgoog/page/n6|title=Documents diplomatiques: 1875-1876-1877|publisher=]|via=Imprimerie National|place=Paris|year=1877|pages=272–289}} - pages -/545 | |||

| ** {{cite book|author=Administration de la revue générale|url=https://archive.org/details/revuegenerale00unkngoog|title=Revue générale treizième année|volume=25<!--XXV-->|publisher=Imprimerie E. Guyott|place=Brussels|date=1877|pages=–330}} - In the section "Documents historiques" (February, Chapter 10<!--"X"---> which begins on page 319) - pages -/1073 | |||

| ** {{cite book|author=Institut de droit international|url=https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb344631016|title=Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international|publisher=G. Pedone|place=Paris|year=1878|pages=296–316}} - . - Online on 17 January 2011 | |||

| * Non-Muslim languages<!--These were of the officially recognized minority group millets in the Ottoman Empire: Greek, Armenian, Bulgarian, and Jewish (for Ladino)-->: ( {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190910161128/http://medusa.libver.gr/jspui/bitstream/123456789/3866/2/OTHOMANIKON%20SYNTAGMA.pdf |date=2019-09-10 }}) from the Turkish, published by Voutyras Press, at the ] - From Sismanoglio Megaro of the Consulate Gen. of Greece in Istanbul ; | |||

| ** Note the Greek is in the ] style; for a portion in modern ] see {{cite web|url=http://cdrsee.org/jhp/pdf/WorkBook2_gr.pdf|title=Έθνη και κράτη στη Νοτιοανατολική Ευρώπη|pages=70–71}} - Translated from the Boğaziçi English version by Professor Spyros Marketos, released in 2006 | |||

| ; Other | |||

| * {{cite web|author=Özbudun, Ergun|url=https://oxcon.ouplaw.com/view/10.1093/law-mpeccol/law-mpeccol-e639|title=Ottoman Constitution of 1876|work=]|year=2016 |doi=10.1093/law:mpeccol/e639.013.639 }} | |||

| {{Abdul Hamid II}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{link FA|de}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:56, 10 December 2024

First constitution of the Ottoman EmpireYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (December 2009) Click for important translation instructions.

|

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Constitution of the Ottoman Empire" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Constitution of the Ottoman Empire (Ottoman Turkish: قانون أساسي, romanized: Kānûn-ı Esâsî, lit. 'Basic law'; French: Constitution ottomane ; persian: قانون اساسی) was in effect from 1876 to 1878 in a period known as the First Constitutional Era, and from 1908 to 1922 in the Second Constitutional Era. The first and only constitution of the Ottoman Empire, it was written by members of the Young Ottomans, particularly Midhat Pasha, during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876–1909). After Abdul Hamid's political downfall in the 31 March Incident, the Constitution was amended to transfer more power from the sultan and the appointed Senate to the popularly-elected lower house: the Chamber of Deputies.

In the course of their studies in Europe, some members of the new Ottoman elite concluded that the secret of Europe's success rested not only with its technical achievements but also with its political organizations. Moreover, the process of reform itself had imbued a small segment of the elite with the belief that constitutional government would be a desirable check on autocracy and provide it with a better opportunity to influence policy. Sultan Abdulaziz's chaotic rule led to his deposition in 1876 and, after a few troubled months, to the proclamation of an Ottoman constitution that the new sultan, Abdul Hamid II, pledged to uphold.

Background

The Ottoman Constitution was introduced after a series of reforms were promulgated in 1839 during the Tanzimat era. The goal of the Tanzimat era was to reform the Ottoman Empire under the auspices of Westernization. In the context of the reforms, Western-educated Armenians of the Ottoman Empire drafted the Armenian National Constitution in 1863. The Ottoman Constitution of 1876 was under direct influence of the Armenian National Constitution and its authors. The Ottoman Constitution of 1876 itself was drawn up by Western-educated Ottoman Armenian Krikor Odian, who was the advisor of Midhat Pasha.

Attempts at reform within the empire had long been made. Under the reign of Sultan Selim III, there was a vision of actual reform. Selim tried to address the military's failure to effectively function in battle; even the basics of fighting were lacking, and military leaders lacked the ability to command. Eventually his efforts led to his assassination by the Janissaries. This action soon led to Mahmud II becoming Sultan. Mahmud can be considered the "first real Ottoman reformer", since he took a substantive stand against the janissaries by removing them as an obstacle in the Auspicious Incident.

This led to what was known as the Tanzimat, which lasted from 1839 to 1876. This era was defined as an effort of reform to distribute power from the Sultan (even trying to remove his efforts) to the newly formed government led by a parliament. These were the intentions of the Sublime Porte, which included the newly formed government. The purpose of the Tanzimat era was reform, but mainly, to divert power from the Sultan to the Sublime Porte. The first indefinable act of the Tanzimat period was when Sultan Abdülmecid I issued the Edict of Gülhane. This document or statement expressed the principles that the liberal statesmen wanted to become an actual reality. The Tanzimat politicians wanted to prevent the empire from falling completely into ruin.

During this time the Tanzimat had three different sultans: Abdülmecid I (1839–1861), Abdülaziz (1861–1876), and Murad V (who only lasted three months in 1876). During the Tanzimat period, the man from the Ottoman Empire with the most respect in Europe was Midhat Pasha. Midhat dreamed of an Empire in which "there would be neither Muslim nor non-Muslim but only Ottomans". Such ideology led to the formation of groups such as the Young Ottomans and the Committee of Union and Progress (who merged with the Ottoman Unity Society). These movements attempted to bring about real reform not by means of edicts and promises, but by concrete action. Even after Abdulhamid II suspended the constitution, it was still printed in the salname, or yearbooks made by the Ottoman government.

Johann Strauss, author of "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages", wrote that the Constitution of Belgium and the Constitution of Prussia (1850) "seem to have influenced the Ottoman Constitution".

Aim

The Ottoman Porte believed that once the Christian population was represented in the legislative assembly, no foreign power could legitimize the promotion of her national interests under pretext of representing the rights of these people of religious and ethnic bonds. In particular, if successfully implemented, it was thought that it would rob Russia of any such claims. However, its potential was never realized and the tensions with the Russian Empire culminated in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878).

Framework

After Sultan Murad V was removed from office, Abdul Hamid II became the new Sultan. Midhat Pasha was afraid that Abdul Hamid II would go against his progressive visions; consequently he had an interview with him to assess his personality and to determine if he was on board. The Constitution proposed a bicameral parliament, the General Assembly, consisting of the Sultan-selected Senate and the generally elected Chamber of Deputies (although not directly; the populace chose delegates who would then choose the Deputies). There were also elections held every four years to keep the parliament changing and to continually express the voice of the people. This same framework carried over from the Constitution as it was in 1876 until it was reinstated in 1908. All in all the framework on the Constitution did little to limit the Sultan's power. Some of the retained powers of the Sultan were: declaration of war, appointment of new ministers, and approval of legislation.

Implementation

Although talks about the implementation of a constitution were in place during the rule of Murad V, they did not come to fruition. A secret meeting between Midhat Pasha, the main author of the constitution, and Abdul Hamid II, the brother of the sultan, was arranged in which it was agreed that a constitution would be drafted and promulgated immediately after Abdul Hamid II came to the throne. Following this agreement, Murat V was deposed on 1876 by a fetva on the grounds of insanity. A committee of 24 (later 28) people, led by Midhat Pasha, was formed to work on the new constitution. They submitted the first draft on 13 November 1876 which was obstreperously rejected by Abdul Hamid II's ministers on the grounds of the abolishment of the office of the Sadrazam. After strenuous debates, a constitution acceptable to all sides was established and the constitution was signed by Abdul Hamid II on the morning of December 13, 1876.

Language versions

According to Strauss, the authorities seemed to have had prepared multiple language versions of the constitution at the same time prior to release as their publication year was 1876: he stated that such release "apparently occurred simultaneously". They were officially published in various newspapers, owned by their respective publishers, according to language, and there were other publications that re-printed them.

Strauss divides the translations into "Oriental-style" versions - ones made for adherents of Islam, and "Western-style" versions - ones made for Christian and Jewish people, including Ottoman citizens and foreigners residing in the empire.

Versions for Muslims

The constitution was originally made in Ottoman Turkish with a Perso-Arabic script. The Ottoman government printed it, as did printing presses from private individuals.

There are a total of ten Turkish terms, and the document instead relies on words from Arabic, which Strauss argues is "excessive". In addition, he stated that other defining aspects include "convoluted sentences typical of Ottoman chancery style", izafet, and a "deferential indirect style" using honorifics. Therefore Strauss wrote that due to its complexity, "A satisfactory translation into Western languages is difficult, if not impossible." Max Bilal Heidelberger wrote a direct translation of the Ottoman Turkish version and published it in a book chapter by Tilmann J Röder, "The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives."

A Latin script rendition of the Ottoman Turkish appeared in 1957, in the Republic of Turkey, in Sened-i İttifaktan Günümüze Türk Anayasa Metinleri, edited by Suna Kili and A. Şeref Gözübüyük and published by Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları.

In addition to the original Ottoman Turkish, the document had been translated into Arabic and Persian. Language versions for Muslims were derived from the Ottoman Turkish version, and Strauss wrote that the vocabularies of the Ottoman Turkish, Arabic, and Persian versions were "almost identical". Despite the Western concepts in the Ottoman Constitution, Strauss stated that "The official French version does not give the impression that the Ottoman text is a translation of it."

The Arabic version was published in Al-Jawā ́ ib. Strauss, who also wrote "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire," stated that the terminology used in the Arabic version "stuck almost slavishly" to that of the Ottoman Turkish, with Arabic itself "almost exclusively" being the source of the terminology; as newer Arabic words were replacing older ones used by Ottoman Turkish, Strauss argued that this closeness "is more surprising" compared to the closeness of the Persian version to the Ottoman original, and that the deliberate closeness to the "Ottoman text is significant, but it is difficult to find a satisfactory explanation for this practice."

From 17 January 1877 a Persian version appeared in Akhtar. Strauss stated that the closeness of the Persian text to the Ottoman original was not very surprising as Persian adopted Arabic-origin Ottoman Turkish words related to politics.

Versions for non-Muslim minorities

Versions for non-Muslims included those in Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, and Judaeo-Spanish (Ladino). There was also a version in Armeno-Turkish, Turkish written in the Armenian alphabet. These versions were respectively printed in Masis, Makikat, Vyzantis, De Castro Press, and La Turquie.

Strauss stated that versions for languages used by non-Muslims were based on the French version, being the "model and the source of the terminology". Strauss pointed to the fact that honorifics and other linguistic features in Ottoman Turkish were usually not present in these versions. In addition each language version has language-specific terminology that is used in place of some terms from Ottoman Turkish. Different versions either heavily used foreign terminology or used their own languages' terminologies heavily but they generally avoided using the Ottoman Turkish one; some common French-derived Ottoman terms were replaced with other words. Based on the differences between the versions for non-Muslims and the Ottoman Turkish version, Strauss concluded that "foreign influences and national traditions – or even aspirations" shaped the non-Muslim versions, and that they "reflect religious, ideological and other divisions existing in the Ottoman Empire."

Since the Armenian version, which Strauss describes as "puristic", uses Ottoman terminology not found in the French version and on some occasions in lieu of native Armenian terms, Strauss described it as having "taken into account the Ottoman text". The publication Bazmavep ("Polyhistore") re-printed the Armenian version.

The Bulgarian version was re-printed in four other newspapers: Dunav/Tuna, Iztočno Vreme, Napredŭk or Napredǎk ("Progress") and Zornitsa ("Morning Star"). Strauss wrote that the Bulgarian version "corresponds exactly to the French version"; the title page of the copy in the collection of Christo S. Arnaudov (Bulgarian: Христо С. Арнаудовъ; Post-1945 spelling: Христо С. Арнаудов) stated that the work was translated from Ottoman Turkish, but Strauss said this is not the case.

Strauss stated that the Greek version "follows the French translation" while adding Ottoman synonyms of Greek terminology and Greek synonyms of Ottoman terminology.

Strauss wrote that "perhaps the Judaeo-Spanish – version may have been checked against the original Ottoman text".

Strauss also wrote "There must have also been a Serbian version available in ". Arsenije Zdravković published a Serbian translation after the Young Turk Revolution.

Versions for foreigners

There were versions made in French and English. The former was intended for diplomats and was created by the Translation Office (Terceme odası). Strauss stated that a draft copy of the French version had not been located and there is no evidence that states that one had ever been made. The French version has some terminology originating from Ottoman Turkish.

A 1908 issue of the American Journal of International Law printed an Ottoman-produced English version but did not specify its origin. After analysing a passage from it, Strauss concluded "Clearly, the “contemporary English version” was also translated from the French version."

Strauss wrote "I have not come across a Russian translation of the Kanun-i esasi. But it is highly probable that it existed."

Terminology

Versions in several languages for Christians and Jews used variants of the word "constitution": konstitutsiya in Bulgarian, σύνταγμα (syntagma) in Greek, konstitusyon in Judaeo-Spanish, and ustav in Serbian. The Bulgarian version used a term in Russian, the Greek version used a calque from the French word "constitution", the Judaeo-Spanish derived its term from the French, and the Serbian version used a word from Slavonic. The Armenian version uses the word sahmanadrut‘iwn (also Sahmanatrov;ivn, Western Armenian: սահմանադրութիւն; Eastern style: Armenian: սահմանադրություն).

Those in Ottoman Turkish, Arabic, and Persian used a word meaning "basic law", Kanun-i esasi in Turkish, al-qānūn al-asāsī in Arabic, and qānūn-e asāsī in Persian. Strauss stated that the Perso-Arabic term is closer in meaning to "Grundgesetz".

European influence

As European power increased over the 18th century, the Ottomans saw a lack of progress themselves. In the Treaty of Paris (1856), the Ottomans were now considered part of the European world. This was the beginning of intervention by Europeans (i.e. the United Kingdom and France) in the Ottoman Empire. One of the reasons they were taking a step into Ottoman territory was for the protection of Christianity in the Ottoman Empire. There had been perennial conflict between Muslims and non-Muslims in the Empire. This was the focal point for the Russians to interfere, and the Russians were perhaps the Ottomans' most disliked enemy. The Russians looked for many ways to become involved in political affairs especially when unrest in the Empire reached their borders. The history of the Russo-Turkish wars was long, for many different reasons. The Ottomans saw the Russians as their most fierce enemy and not one to be trusted.

Domestic and foreign reactions

Reactions within the Empire and around Europe were both widely acceptable and potentially a cause for some concern. Before the Constitution was enacted and made official, many of the Ulema were against it because they deemed it to be going against the Shari'a. However, throughout the Ottoman Empire, the people were extremely happy and looking forward to life under this new regime. Many people celebrated and joined in Muslim-Christian relations which formed, and there now seemed to be a new national identity: Ottoman. However many provinces and people within the Empire were against it and many acted out their displeasure in violence. Some Muslims agreed with the Ulema that the constitution violated Shari'a law. Some acted out their protests by attacking a priest during mass. Some of the provinces referred to in the constitution were alarmed, such as Rumania, Scutari and Albania, because they thought it referred to them having a different change of government or no longer being autonomous from the Empire.

Yet the most important reaction, only second to that of the people, was that of the Europeans. Their reactions were quite to the contrary from the people; in fact they were completely against it—so much so that the United Kingdom was against supporting the Sublime Porte and criticized their actions as reckless. Many across European saw this constitution as unfit or a last attempt to save the Empire. In fact only two small nations were in favor of the constitution but only because they disliked the Russians as well. Others considered the Ottomans to be grasping for straws in trying to save the Empire; they also labeled it as a fluke of the Sublime Porte and the Sultan.

Initial suspension of the constitution

After the Ottomans were defeated in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) a truce was signed on 31 January 1878 in Edirne. Fourteen days after this event, on February 14, 1878, Abdul Hamid II took the opportunity to prorogue the parliament, citing social unrest. This allowed him to avoid new elections. Abdul Hamid II, increasingly withdrawn from society to the Yıldız Palace, was therefore able rule the most part of three decades in an absolutist manner.

Second Constitutional Era

Main article: Second Constitutional EraThe Constitution was put back into effect in 1908 as Abdul Hamid II came under pressure, particularly from some of his military leaders. Abdul Hamid II's fall came as a result of the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, and the Young Turks put the 1876 constitution back into effect. The second constitutional period spanned from 1908 until after World War I when the Ottoman Empire was dissolved. Many political groups and parties were formed during this period, including the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP).

Final Suspension of the Constitution

On 20 January 1920, the Grand National Assembly met and ratified the Turkish Constitution of 1921. However, since this document did not clearly state whether the Ottoman Constitution of 1876 was superseded, consequentially, only provisions contradictory to the 1921 Constitution became null and void (lex posterior derogat legi priori). The rest of the constitution resumed its implementation up until 20 April 1924, when both the Constitutions of 1876 and 1921 were replaced by an entirely new document, the Constitution of 1924.

Significance of the constitution

The Ottoman Constitution represented more than the immediate effect it had on the country. It was extremely significant because it made all subjects Ottomans under the law. By doing so, everyone, regardless of their religion had the right to liberties such as freedom of press and free education. Despite the latitude it gave to the sovereign, the constitution provided clear evidence of the extent to which European influences operated among a section of the Ottoman bureaucracy. This showed the effects of the pressure from Europeans on the issue of discrimination of religious minorities within the Ottoman Empire, although, Islam was still the recognized religion of the state. The constitution also reaffirmed the equality of all Ottoman subjects, including their right to serve in the new Chamber of Deputies. The constitution was more than a political document; it was a proclamation of Ottomanism and Ottoman patriotism, and it was an assertion that the empire was capable of resolving its problems and that it had the right to remain intact as it then existed. It officially established the subjects of the Empire as "Ottomans," with the Sultan being titled "Padishah and Sovereign of all Ottomans," rather than "of the Turks." The Ottoman Constitution of 1876 was preceded by the Nationality Law of 1869, which created a common and equal citizenship for all Ottomans, regardless of race or religion. The constitution built upon those ideas and expanded on them, well focusing on keep the state together.

Ultimately, although the constitution created an elected chamber of deputies and an appointed senate, it only placed minimal restriction on the Sultan's power. Under the constitution, the Sultan retained the power to declare war and make peace, to appoint and dismiss ministers, to approve legislation, and to convene and dismiss the chamber of deputies. The sultan remained the theocratic legitimized sovereign to which the state organization was made-to-measure. Thus, despite a de jure intact constitution, the sultan ruled in the absolutist manner. This was particularly evident in the closure of Parliament only eleven months after the declaration of the Constitution. Although the basic rights guaranteed in the constitution were not at all insignificant in Ottoman legal history, they were severely limited by the pronouncements of the ruler. Instead of overcoming sectarian divisions through the institution of universal representation, the elections reinforced the communitarian basis of society by allotting quotas to the various religious communities based on projections of population figures derived from the census of 1844. Furthermore, in order to appease the European powers, the Ottoman administration drafted an exceedingly uneven representational scheme that favored the European provinces by an average 2:1 ratio.

See also

Notes

- For a scientific English translation directly from the Ottoman Turkish version of the constitution, done by Max Bilal Heidelberger, see below. It originates from the copy published in the Düstūr (Ottoman Official Gazette) 1st series (tertïb-i evvel), Volume 4, Pages 4-20.

- Röder, Tilmann J. (2012-01-11). "The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives". In Grote, Rainer; Tilmann J. Röder (eds.). Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries. Oxford University Press USA. pp. 321-372. ISBN 9780199759880. - Old ISBN 019975988X

- "B. Revisions of the Basic Law" - Start p. 352

- Law No. 130 on the Revision of Some Articles of the Basic Law of 7th Zi’lhijjeh 1293 (5th Sha’ban 1327 / August 8, 1909)

- Law No. 318 Revising the Articles 7, 35, and 43 Revised on 5th Sha’ban 1327 (2nd Rejeb 1332 – May 15, 1914)

- Law No. 80 Revising the Article 102 of the Basic Law of the 7th Zi’lhijjeh 1293 and the Articles 7 and 43 Revised on 2nd Rejeb 1332 (26th Rebi’ü-’l-Evvel 1333 – January 29, 1914)

- Law No. 307 Revising the Revision of Article 76 of 5th Sha’ban 1327 (4th Jumada-‘l-Ula 1334 – February 25, 1916)

- Law on the Revision of the Revised Art. 7 of the Basic Law of 26th Rebi’ü-’l-Evvel 1333 and the Deletion of the Revised Art. 35 of 2nd Rejeb 1332 (4th Jumada-‘l-Ula 1334 – February 25, 1916)

- Law No. 370 Revising Article 72 of the Basic Law of 7th Zi’lhijjeh 1293 (15th Jumada-‘l-Ula 1334 – March 7, 1916); Law No 102 Revising Art. 69 of the Basic Law (8th Jumada-‘l-Ula 1334 – March 21, 1918).

References

- Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg: Orient-Institut Istanbul. pp. 21–51. (info page on book at Martin Luther University)

Reference notes

- For a modern English translation of the constitution and related laws, see Tilmann J. Röder, The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, in: Grote/Röder, Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries (Oxford University Press 2011).

- Cleveland, William (2013). A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0813340487.

- Cleveland, William L & Bunton, Martin (2009). A History of the Modern Middle East (4th ed.). Westview Press. p. 82.

- Joseph, John (1983). Muslim-christian relations & inter-christian rivalries in the middle east: the case of the Jacobites. : Suny Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780873956000. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ^ H. Davison, Roderic (1973). Reform in the Ottoman Empire, 1856–1876 (2, reprint ed.). Gordian Press. p. 134. ISBN 9780877521358. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

But it can be shown that Midhat Pasa, the principal author of the 1876 constitution, was directly influenced by the Armenians.

- United States Congressional serial set, Issue 7671 (Volume ed.). United States Senate: 66th Congress. 2nd session. 1920. p. 6. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

In 1876 a constitution for Turkey was drawn up by the Armenian Krikor Odian, secretary to Midhat Pasha the reformer, and was proclaimed and almost immediately revoked by Sultan Abdul Hamid

- Bertrand Bereilles. "La Diplomatie turco-phanarote". Introduction to Rapport secret de Karatheodory Pacha sur le Congrès de Berlin, Paris, 1919, p. 25. Quote translated from French: "The majority of the government officials in the Ottoman Empire selected a Greek or an Armenian as their advisor in reform." The author mentions two names amongst these "advisors", Dr. Serop Vitchenian, who was the adviser to Fuad Pasha, and Grigor Odian, deputy to Midhat Pasha, who is the author of the Ottoman constitution of 1876.

- Devereux, Robert (1963). The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 22.

- ^ Devereux, Robert (1963). The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 22.

- ^ Devereux, Robert (1963). The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 21

- Devereux, Robert (1963). The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 25

- Findley, Carter V. (1980). Bureaucratic Reform in the Ottoman Empire: The Sublime Porte 1789–1922. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780691052885.

- ^ Devereux, Robert (1963). The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 30

- ^ Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire", p. 32.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire", p. 36.

- Berkes, Niyazi. The Development of Secularism in Turkey. Montreal: McGill University Press, 1964. pp. 224–225

- Devereux, Robert (1963). The First Ottoman Constitutional Period: A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press. p. 43

- A history of the Modern Middle East, Cleveland and Bunton, p. 79

- ^ Berkes, Niyazi. The Development of Secularism in Turkey.Montreal: McGill University Press, 1964. pp. 224-225,242-243, 248-249.

- No reliable information is available on this meeting, although the following source can be consulted with caution: Celaleddin, Mir'at-i Hakikat, I, pp. 168.

- ^ Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 34 (PDF p. 36/338).

- ^ Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 50 (PDF p. 52/338).

- ^ Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 35 (PDF p. 37/338).

- ^ Strauss, Johann (2016-07-07). "Language and power in the late Ottoman Empire". In Murphey, Rhoads (ed.). Imperial Lineages and Legacies in the Eastern Mediterranean: Recording the Imprint of Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman Rule. Routledge. p. PT193. ISBN 9781317118442. Page from Google Books. In Chapter no. 7. Volume 18 of Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies. Old ISBN 1317118448.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 49 (PDF p. 51/338).

- ^ Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 33 (PDF p. 35/338).

- ^ Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 51 (PDF p. 53/338).

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 41 (PDF p. 43/338).

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 50-51 (PDF p. 52-53/338).

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 47 (PDF p. 49/338).

- Strauss, Johann. "Twenty Years in the Ottoman capital: the memoirs of Dr. Hristo Tanev Stambolski of Kazanlik (1843-1932) from an Ottoman point of view." In: Herzog, Christoph and Richard Wittmann (editors). Istanbul - Kushta - Constantinople: Narratives of Identity in the Ottoman Capital, 1830-1930. Routledge, 10 October 2018. ISBN 1351805223, 9781351805223. p. 267.

- ^ Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 46 (PDF p. 50/338).

- ^ Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages," p. 46 (PDF p. 48/338).

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages," p. 38 (PDF p. 40/338).

- Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 24

- Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 45

- Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 82

- Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 84

- "Egypt". The Times (London, England). January 26, 1877. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 85

- Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 87

- Devereux, Robert, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1963, Print, p. 88

- Gottfried Plagemann: Von Allahs Gesetz zur Modernisierung per Gesetz. Gesetz und Gesetzgebung im Osmanischen Reich und der Republik Türkei. Lit Verlag

- ^ Cf. Jean Deny: 'Abd al-Ḥamīd. In: The Encyclopedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 2, Brill, Leiden 2002, pp. 64-65.

- Gözler, Kemal (2008). Türk Anayasa Hukukuna Giriş. Bursa: Ekin Kitabevi. p. 32.

- Boğaziçi University, Atatürk Institute of Modern Turkish History