| Revision as of 02:54, 22 May 2006 editYonnie4th (talk | contribs)1 editm →Go in popular culture← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:12, 28 November 2024 edit undoSomewhatviable (talk | contribs)131 editsm →In popular culture: Wording | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Abstract strategy board game for two players}} | |||

| {{Infobox_Game| | |||

| {{About|the board game||Go (disambiguation)}} | |||

| subject_name= Go | | |||

| {{Infobox game | |||

| image_link= ] | | |||

| | title = Go | |||

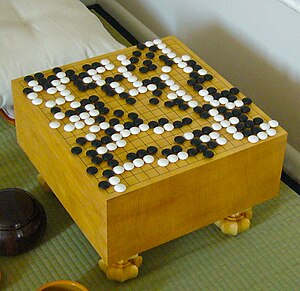

| image_caption= A traditional board for the game is wooden, with the lines painted on. The stones are flattened spheroids and fit closely together when placed on adjacent points. | | |||

| | italic title = no | |||

| players= 2 | | |||

| | image_link = FloorGoban.JPG | |||

| ages= Any | | |||

| | image_size = 300px | |||

| setup_time= No setup needed | | |||

| | image_caption = Go is played on a grid (usually 19×19). Game pieces (''stones'') are placed on the grid line intersections. | |||

| playing_time= 10 minutes to 3 hours,<br>although tournament games can last more than 16 hours | | |||

| | years = 548 BCE (earliest record) to present | |||

| complexity= Low | | |||

| | genre = {{ubl|]|]|]}} | |||

| strategy= Very High | | |||

| | players = 2 | |||

| random_chance= None | | |||

| | setup_time = Minimal | |||

| skills= ], Observation | | |||

| | playing_time = {{ubl|Casual: 20–90 minutes|Professional: 1–6 hours or more{{ref label|note1|a}}}} | |||

| footnotes = | |||

| | random_chance = None | |||

| | skills = ], ], ] | |||

| | AKA = {{ubl|{{audio|Zh-wéiqí.ogg|Weiqi|help=no}}|{{transliteration|ja|Igo}}|{{transliteration|ko|Paduk}} / {{transliteration|ko|Baduk}}}} | |||

| | footnotes = {{note label|note1|a}}Some professional games exceed 16 hours and are played in sessions spread over two days. | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox Chinese | |||

| | t = {{linktext|圍棋}} | |||

| | s = {{linktext|围棋}} | |||

| | l = 'encirclement board game' | |||

| | p = wéiqí | |||

| | w = {{tone superscript|wei2-ch}}{{wg-apos}}{{tone superscript|i2}} | |||

| | mi = {{IPAc-cmn|AUD|Zh-wéiqí.ogg|wei|2|.|q|i|2}} | |||

| | suz = wé-jí | |||

| | j = wai4 kei4 | |||

| | y = wàih-kèih | |||

| | ci = {{IPAc-yue|w|ai|4|-|k|ei|4}} | |||

| | poj = uî-kî | |||

| | mc = hwigi | |||

| | oc-bs = *{{IPA|ʷə (r)ə}} | |||

| | oc-zz = *{{IPA|ɢʷɯl ɡɯ}} | |||

| | kanji = {{linktext|囲碁}} or {{linktext|碁}} | |||

| | hiragana = いご or ご | |||

| | romaji = igo or go | |||

| | hangul = 바둑 | |||

| | rr = baduk | |||

| | mr = paduk | |||

| | tib = མིག་མངས | |||

| | wylie = mig mangs | |||

| | qn = cờ vây | |||

| | hn = 碁圍 | |||

| | tp = wéi-cí | |||

| | bpmf = ㄨㄟˊ ㄑㄧˊ | |||

| | katakana = イゴ or ゴ | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Go''', also known as '''Wéiqí''' in ] ({{zh-t|圍棋}}; {{zh-s|围棋}}), and '''Baduk''' in ] (]:바둑), is a strategic, ] two-player ] originating in ancient ], before ]. The game is now popular throughout ] and on the Internet. The object of the game is to place stones so they control a larger board territory than one's opponent, while preventing them from being surrounded and captured by the opponent. | |||

| # <!--Please do not add names in other languages or more kanji/hanzi/hangul or transliterations in the opening paragraph as the name of the game in Chinese, Japanese and Korean is given in the box on the side, beneath the info box.--> | |||

| The English name ''Go'' originated from the ] pronunciation "go" of the ] 棋/碁; in Japanese the name is written 碁. The ] name Wéiqí roughly translates as "''encirclement chess''", the "''board game of surrounding''", or the "''enclosing game''". Its ancient Chinese name is 弈 ({{zh-p|yì}}). The writings 棋/碁 are variants, as seen in the Chinese ]. The game is known as 囲碁 (''igo'' or ''wigo'') in ]. | |||

| '''Go''' is an ] ] for two players in which the aim is to fence off more territory than the opponent. The game was invented in ] more than 2,500 years ago and is believed to be the oldest board game continuously played to the present day.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.usgo-archive.org/brief-history-go|title=A Brief History of Go|publisher=American Go Association|access-date=March 23, 2017}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|first=Peter|last=Shotwell|title=The Game of Go: Speculations on its Origins and Symbolism in Ancient China|year=2008|publisher=American Go Association|url=http://www.usgo-archive.org/files/bh_library/originsofgo.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130516100351/http://www.usgo.org/files/bh_library/originsofgo.pdf|archive-date=May 16, 2013|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://gobase.org/reading/history/china/?sec=part-2|title=The Legends of the Sage Kings and Divination|publisher=GoBase.org|access-date=May 12, 2022}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=A Brief History of Go {{!}} British Go Association |url=https://www.britgo.org/intro/history |access-date=2023-12-16 |website=www.britgo.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=The Ancient Chinese Game of Go |url=http://www.china.org.cn/english/features/Archaeology/131298.htm |access-date=2023-12-16 |website=www.china.org.cn}}</ref> A 2016 survey by the ]'s 75 member nations found that there are over 46 million people worldwide who know how to play Go, and over 20 million current players, the majority of whom live in ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.intergofed.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2016_Go_population_report.pdf|title=Go Population Survey|last=The International Go Federation|date=February 2016|website=intergofed.org|access-date=28 November 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170517013354/http://www.intergofed.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2016_Go_population_report.pdf|archive-date=17 May 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == Overview of the game == | |||

| The game of Go is played by alternately placing stones on a grid. The two players, black and white, engage to maximize the territory they control, seeking to surround large areas of the board with their stones, to entrap any opposing stones that invade these areas, and to protect their own stones from capture. | |||

| The ] are called '']''. One player uses the white stones and the other black. The players take turns placing their stones on the vacant intersections (''points'') on the ]. Once placed, stones may not be moved, but ''captured stones'' are immediately removed from the board. A single stone (or connected group of stones) is ''captured'' when surrounded by the opponent's stones on all ] adjacent points.{{sfn|Iwamoto|1977|p=22}} The game proceeds until neither player wishes to make another move. | |||

| The strategy involved can become very subtle and complex. Some high-level players spend years perfecting strategy. Go is considered by some to be the ultimate strategy game, superior in depth of complexity to ], ], and ]. | |||

| When a game concludes, the winner is determined by counting each player's surrounded territory along with captured stones and ] (points added to the ] of the player with the white stones as compensation for playing second).{{sfn|Iwamoto|1977|p=18}} Games may also end by resignation.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| Go is typically classified as an ]. However, a resemblance between the game of Go and war is often suggested. The ] '']'', for instance, has sometimes been applied to Go strategy as well. On the other hand, general strategies of Go are well described by ] and are applied in other contexts such as management. | |||

| The standard Go board has a 19×19 ] of lines, containing 361 points. Beginners often play on smaller 9×9 or 13×13 boards,{{sfn|Matthews|2004|p=1}} and archaeological evidence shows that the game was played in earlier centuries on a board with a 17×17 grid. Boards with a 19×19 grid had become standard, however, by the time the game reached ] in the 5th century ] and ] in the 7th century CE.{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=18}} | |||

| Real wars end when the participants sign treaties. Likewise, in Go, the players have to agree that the game has ended. Only then are the score and the winner finally determined. | |||

| Go was considered one of the ] of the cultured ] Chinese scholars in antiquity. The earliest written reference to the game is generally recognized as the historical annal '']''<ref name="The Tso Chuan book">{{cite book|last=Burton|first=Watson|title=The Tso Chuan|date=April 15, 1992|publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-231-06715-7}}</ref>{{sfn|Fairbairn|1995|p={{page needed|date=May 2014}}}} ({{circa|4th century}} BCE).<ref name=chronology2>{{cite web|title=Warring States Project Chronology #2|publisher=University of Massachusetts Amherst|url=http://www.umass.edu/wsp/project/introductions/chronology2.html|access-date=2007-11-30|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071219225436/http://www.umass.edu/wsp/project/introductions/chronology2.html|archive-date=2007-12-19}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{main|History of Go}} | |||

| Despite its relatively ], Go is extremely complex. Compared to ], Go has both a larger board with more scope for play and longer games and, on average, many more alternatives to consider per move. The number of legal board positions in Go has been calculated to be approximately {{val|2.1e170}},<ref>{{cite web|url=https://tromp.github.io/go/gostate.pdf|last1=Tromp|first1=John|last2=Farnebäck|first2=Gunnar|title=Combinatorics of Go|website=tromp.github.io|date=January 31, 2016|access-date=June 17, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160125182938/https://tromp.github.io/go/gostate.pdf|archive-date=January 25, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref>{{efn|1=Game complexity can be difficult to estimate. The number of legal positions (]) for chess has been estimated at anywhere between 10<sup>43</sup> and 10<sup>50</sup>; in 2016 the number of legal positions for 19x19 Go was calculated by Tromp and Farneback at ~{{val|2.08e170}}. Alternately, a measure of all the alternatives to be considered at each stage of the game (]) can be estimated with ''b<sup>d</sup>'', where ''b'' is the game's breadth (number of legal moves per position) and ''d'' is its depth (number of moves or '']'' per game). For chess and Go the comparison is very rough, ~35<sup>80</sup> ≪ ~250<sup>150</sup>, or ~10<sup>123</sup> ≪ ~10<sup>360</sup>{{sfn|Allis|1994|pp=158–161, 171, 174|ps=, §§6.2.4, 6.3.9, 6.3.12}}}} which is far greater than the ], which is estimated to be on the order of 10<sup>80</sup>.<ref>{{cite book|last=Lee|first=Kai-Fu|author-link=Kai-Fu Lee|title=AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order|date=September 25, 2018|publisher=]|isbn=9781328546395|access-date=June 17, 2020|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xb9wDwAAQBAJ}}</ref> | |||

| ] in the ].]] | |||

| The origins of the game lie in ] and the earliest references come from China in the ] (], from '']''). Except for changes in the board size and starting position, Go has essentially kept the same rules since that time, which quite likely makes it the oldest board game still played today. | |||

| {{GoBoardGame}} | |||

| According to legend, the game was used as a ] tool after the ancient ] ] 堯 (2337 - 2258 BC) designed it for his son, Danzhu, who he thought needed to learn discipline, concentration, and balance. Another suggested genesis for the game states that in ancient times, Chinese warlords and generals would use pieces of stone to map out attacking positions. Further and more plausible theories relate Go equipment to ] or ]. | |||

| ==Names of the game== | |||

| Before the industrial age in China, Go was long perceived as the popular game of the elite aristocratic class while ] (Chinese chess) was perceived as the game of the masses. Go was considered one of the cultivated arts of the ] (]), along with ], ] and playing the ], known as 琴棋書畫 (], ]: Sìyì), or the ]. | |||

| The name ''Go'' is a short form of the Japanese word {{transliteration|ja|igo}} ({{lang|ja|囲碁}}; {{lang|ja|いご}}), which derives from earlier {{transliteration|ja|wigo}} ({{lang|ja|ゐご}}), in turn from ] {{transliteration|zh|{{IPA|ɦʉi gi}}}} ({{lang|zh|圍棋}}, ]: {{transliteration|zh|wéiqí}}, {{lit|encirclement board game|board game of surrounding}}). In English, the name ''Go'' when used for the game is often capitalized to differentiate it from the common word ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Gao |first=Pat |title=Getting the Go-ahead |url=http://taiwanreview.nat.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=24319&CtNode=1360 |journal=Taiwan Review |year=2007 |volume=57 |page=55 |publisher=Kwang Hwa Publishing |location=Los Angeles, CA |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120122131232/http://taiwanreview.nat.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=24319&CtNode=1360 |archive-date=2012-01-22}}</ref> In events sponsored by the ] Foundation, it is spelled ''goe''.<ref>See, e.g., {{cite web|url=https://www.eurogofed.org/egf/ing2005.htm|title=EGF Ing Grant Report 2004-2005|publisher=]|access-date=28 October 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171028201540/https://www.eurogofed.org/egf/ing2005.htm|archive-date=28 October 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| The Korean name {{transliteration|ko|baduk}} (바둑) derives from the ] word {{transliteration|ko|Badok}}, the origin of which is controversial; the more plausible etymologies include the suffix {{transliteration|ko|dok}} added to {{transliteration|ko|Ba}} to mean 'flat and wide board', or the joining of {{transliteration|ko|Bat}}, meaning 'field', and {{transliteration|ko|Dok}}, meaning 'stone'. Less plausible etymologies include a derivation of {{transliteration|ko|Badukdok}}, referring to the playing pieces of the game, or a derivation from Chinese {{transliteration|zh|páizi}} ({{lang|zh|排子}}), meaning 'to arrange pieces'.<ref>{{cite book |last=조 |first=항범 |date=October 8, 2005 |title=그런 우리말은 없다 |url=http://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?docId=982836&cid=85&categoryId=2641 |publisher=태학사 |isbn=9788959660148 |access-date=June 3, 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Go had reached Japan from China by the ], and gained popularity at the imperial court in the ]. By the beginning of the ], the game was played in the general public in Japan. | |||

| == Overview == | |||

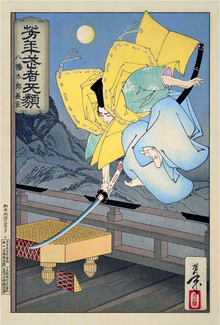

| ] playing Go while having his wounds attended to]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Early in the ], the then best player in Japan, ], was made head of a newly founded Go academy (the ], the first of several competing schools founded about the same time), which developed the level of playing greatly, and introduced the ] style system of ranking players. The government discontinued its support for the Go academies in ] as a result of the fall of the ]. | |||

| Go is an adversarial game between two players with the objective of capturing territory. That is, occupying and surrounding a larger total empty area of the board with one's stones than the opponent.{{sfn|Matthews|2004|p=2}} As the game progresses, the players place stones on the board creating stone "formations" and enclosing spaces. Stones are never moved on the board, but when "captured" are removed from the board. Stones are linked together into a formation by being adjacent along the black lines, not on diagonals (of which there are none). Contests between opposing formations are often extremely complex and may result in the expansion, reduction, or wholesale capture and loss of formations and their enclosed empty spaces (called "eyes"). Another essential component of the game is control of the ''sente'' (that is, controlling the offense, so that one's opponent is forced into defensive moves); this usually changes several times during play. | |||

| In honour of the Honinbo school, whose players consistently dominated the other schools during their history, one of the most prestigious Japanese Go championships is called the "]" tournament. | |||

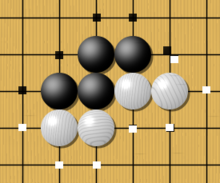

| displays the four "liberties" (adjacent empty points) of a single black stone. Illustrations , , and show White reducing those liberties progressively by one. In , when Black has only one liberty left, that stone is under attack and about to be captured and eliminated (a state called ''atari'').{{sfn|Cobb|2002|p=12}} White may capture that stone (remove it from the board) with a play on its last liberty (at D-1).]] | |||

| Historically, Go has been unequal in terms of ]. However, the opening of new, open tournaments and the rise of strong female players, most notably ], has in recent years legitimised the strength and competitiveness of emerging female players. | |||

| Initially the board is bare, and players alternate turns to place one stone per turn. As the game proceeds, players try to link their stones together into "living" formations (meaning that they are permanently safe from capture), as well as threaten to capture their opponent's stones and formations. Stones have both offensive and defensive characteristics, depending on the situation. | |||

| An essential concept is that a formation of stones must have, or be capable of making, at least two enclosed open points known as ] to preserve itself from being captured. A formation having at least two eyes cannot be captured, even after it is surrounded by the opponent on the outside,{{sfn|Iwamoto|1977|p=77}} because each eye constitutes a ] that must be filled by the opponent as the final step in capture. A formation having two or more eyes is said to be unconditionally ],{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=21}} so it can evade capture indefinitely, and a group that cannot form two eyes is said to be ''dead'' and can be captured. | |||

| Around 2000, in ], the ] (Japanese comic) and ] series '']'' popularized Go among the youth and started a Go boom in Japan. In January 2004, the ''Hikaru no Go'' manga began running in the US (monthly) edition of '']''. Whether this will lead to a strong following in the US is yet to be seen. | |||

| The general strategy is to place stones to fence-off territory, attack the opponent's weak groups (trying to kill them so they will be removed), and always stay mindful of the ] of one's own groups.{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=28}}{{sfn|Cobb|2002|p=21}} The liberties of groups are countable. Situations where mutually opposing groups must capture each other or die are called capturing races, or ].{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=69}} In a capturing race, the group with more liberties will ultimately be able to capture the opponent's stones.{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=69}}{{sfn|Cobb|2002|p=20}}{{efn|Eyes and other complications may need to be considered when counting liberties}} Capturing races and the elements of life or death are the primary challenges of Go. | |||

| Scott A. Boorman's ''The Protracted Game: A Wei-Chi Interpretation of Maoist Revolutionary Strategy'' likens the game to historical events, saying that the ] were better at surrounding territory. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| In the end game players may pass rather than place a stone if they think there are no further opportunities for profitable play.<ref>{{cite web|title=KGS Go Tutorial: Game End|url=https://www.gokgs.com/tutorial/gameEnd.jsp|publisher=KGS|access-date=5 June 2014}}</ref> The game ends when both players pass{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=35}} or when one player resigns. In general, to score the game, each player counts the number of unoccupied points surrounded by their stones and then subtracts the number of stones that were captured by the opponent. The player with the greater score (after adjusting for handicapping called ]) wins the game. | |||

| ==Nature of the game== | |||

| Although rules of Go can be written so that they are very simple, the game strategy is extremely complex. Go is a ], ], ], putting it in the same class as ], ] (draughts), and ] (othello). It greatly exceeds draughts and reversi in depth and complexity, and transcends even the complexity of chess. Its large board and lack of restrictions allows great scope in strategy. Decisions in one part of the board may be influenced by an apparently unrelated situation in a distant part of the board. Plays made early in the game can shape the nature of conflict a hundred moves later. | |||

| In the opening stages of the game, players typically establish groups of stones (or ''bases'') near the corners and around the sides of the board, usually starting on the third or fourth line in from the board edge rather than at the very edge of the board. The edges and corners make it easier to develop groups which have better options for ''life'' (self-viability for a group of stones that prevents capture) and establish formations for potential territory.{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=107}} Players usually start near the corners because establishing territory is easier with the aid of two edges of the board.{{sfn|Iwamoto|1977|p=93}} Established corner opening sequences are called ] and are often studied independently.{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=119}} However, in the mid-game, stone groups must also reach in towards the large central area of the board to capture more territory. | |||

| The game emphasizes the importance of balance on multiple levels, and has internal tensions. To secure an area of the board, it is good to play moves close together; but to cover the largest area one needs to spread out. To ensure one does not fall behind, expansionist play is required; but playing too broadly leaves weaknesses undefended that can be exploited. Playing too ''low'' (close to the edge) secures insufficient territory and influence; yet playing too ''high'' (far from the edge) allows the opponent to invade. Many people find the game attractive for its reflection of the contradictary demands found in real life. Indeed, a common saying is "life is like Go". | |||

| ] are points that lie in between the boundary walls of black and white, and as such are considered to be of no value to either side. ] are mutually alive pairs of white and black groups where neither has two eyes. | |||

| The ] of Go is such that even an introduction to strategy can fill a book, and many good introductory books are available. See ] for a very brief introduction to the main concepts of Go strategy. | |||

| ''Ko'' (Chinese and Japanese: {{lang|zh|劫}}) is a potentially indefinitely repeated stone-capture position. The rules do not allow a board position to be repeated. Therefore, any move which would restore the previous board position would not be allowed, and the next player would be forced to play somewhere else. If the play requires a strategic response by the first player, further changing the board, then the second player could "retake the ko," and the first player would be in the same situation of needing to change the board before trying to take the ko back. And so on. {{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=33}} Some of these ''ko fights'' may be important and decide the life of a large group, while others may be worth just one or two points. Some ko fights are referred to as ''picnic kos'' when only one side has a lot to lose.{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=37}} In Japanese, it is called a '']'' ko.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://senseis.xmp.net/?HanamiKo |title=Hanami Ko at Sensei's Library |publisher=Senseis.xmp.net |date=2013-01-09 |access-date=2014-03-25}}</ref> | |||

| It is commonly said that no game has ever been played twice. This may be true: On a 19×19 board, there are about 3<sup>361</sup>×0.012 = 2.1×10<sup>170</sup> possible positions, most of which are the end result of about (120!)<sup>2</sup> = 4.5×10<sup>397</sup> different (no-capture) games, for a total of about 9.3×10<sup>567</sup> games. Allowing captures gives as many as | |||

| Playing with others usually requires a knowledge of each player's strength, indicated by the player's ] (increasing from 30 kyu to 1 kyu, then 1 dan to 7 dan, then 1 dan pro to 9 dan pro). A difference in rank may be compensated by a handicap—Black is allowed to place two or more stones on the board to compensate for White's greater strength.{{sfn|Iwamoto|1977|p=109}}{{sfn|Cho Chikun|1997|p=91}} There are different rulesets (Korean, Japanese, Chinese, AGA, etc.), which are almost entirely equivalent, except for certain special-case positions and the method of scoring at the end. | |||

| :<math>10^{7.49 \times 10^{48}}</math> | |||

| === Basic concepts === | |||

| , all of which last for over 4.1×10<sup>48</sup> moves! (For two comparisons: the number of legal positions in chess is estimated to be between 10<sup>43</sup> and 10<sup>50</sup>; and physicists estimate that there are not more than 10<sup>90</sup> protons in the entire visible universe.) | |||

| {{more citations needed section|date=February 2016}} | |||

| {{Main|Go terms}} | |||

| Basic strategic aspects include the following: | |||

| * Connection: Keeping one's own stones connected means that fewer groups need to make living shape, and one has fewer groups to defend. | |||

| * Cut: Keeping opposing stones disconnected means that the opponent needs to defend and make living shape for more groups. | |||

| * Stay alive: The simplest way to stay alive is to establish a foothold in the corner or along one of the sides. At a minimum, a group must have two eyes (separate open points) to be alive.<ref name=":0">{{Citation|last=Baker|first=Karl|title=The Way to Go: How to Play the Asian Game of Go|year=2008|orig-year=1986|url= http://www.usgo-archive.org/files/pdf/W2Go4E-book.pdf|edition=7th|publisher=American Go Association|location=New York, NY|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121203014424/http://www.usgo.org/files/pdf/W2Go4E-book.pdf|archive-date=December 3, 2012|url-status=live}}</ref> An opponent cannot fill in either eye, as any such move is suicidal and prohibited in the rules. | |||

| * Mutual life (seki) is better than dying: A situation in which neither player can play on a particular point without then allowing the other player to play at another point to capture. The most common example is that of adjacent groups that share their last few liberties—if either player plays in the shared liberties, they can reduce their own group to a single liberty (putting themselves in ''atari''), allowing their opponent to capture it on the next move. | |||

| * Death: A group that lacks living shape is eventually removed from the board as captured. | |||

| * Invasion: Set up a new living group inside an area where the opponent has greater influence, means one reduces the opponent's score in proportion to the area one occupies. | |||

| * Reduction: Placing a stone far enough into the opponent's area of influence to reduce the amount of territory they eventually get, but not so far that it can be cut off from friendly stones outside. | |||

| * Sente: A play that forces one's opponent to respond (]). A player who can regularly play ''sente'' has the initiative and can control the flow of the game. | |||

| * Sacrifice: Allowing a group to die in order to carry out a play, or plan, in a more important area. | |||

| The strategy involved can become very abstract and complex. High-level players spend years improving their understanding of strategy, and a novice may play many hundreds of games against opponents before being able to win regularly. | |||

| == Traditional equipment == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Go equipment}} | |||

| == Strategy == | |||

| Although one could play Go with a piece of cardboard for a board and a bag of plastic tokens, many Go players pride themselves on their game sets. | |||

| {{Main|Go strategy and tactics}} | |||

| Strategy deals with global influence, the interaction between distant stones, keeping the whole board in mind during local fights, and other issues that involve the overall game. It is therefore possible to allow a tactical loss when it confers a strategic advantage. | |||

| The traditional Go board (called a ''goban'' in Japanese) is solid wood, from 10–18 cm thick, and often stands on its own attached legs. It is preferably made from the rare golden-tinged ] tree (''Torreya nucifera''), with the very best made from Kaya trees up to 700 years old. More recently, the ] (''Torreya californica'') has been prized for its light color and pale rings. | |||

| Other woods often used to make quality table boards include ] (''Thujopsis dolabrata''), ] (''Cercidiphyllum japonicum''), and ] (''Agathis''). | |||

| Novices often start by randomly placing stones on the board, as if it were a game of chance. An understanding of how stones connect for greater power develops, and then a few basic ] may be understood. Learning the ways of life and death helps in a fundamental way to develop one's strategic understanding of ''weak groups''.{{efn|1=Whether or not a group is weak or strong refers to the ease with which it can be killed or made to live. See this by Benjamin Teuber, amateur 6 dan, for some views on how important this is felt to be.}} A player who both plays aggressively and can handle adversity is said to display ], or fighting spirit, in the game. | |||

| Players sit on reed mats ('']'') on the floor to play. The stones (''go-ishi'') are kept in matching solid wood pots (''go-ke'') and are made out of ]shell (white) and ] (black) and are extremely smooth. The classic slate is from the nachiguro slate mined in ] and the clamshell from the Hamaguri clam. The natural resources of Japan have been unable to keep up with the enormous demand for the native clams and slow-growing Kaya trees; both must be of sufficient age to grow to the desired size, and they are now extremely rare at the age and quality required, raising the price of such equipment tremendously. | |||

| === Opening strategy === | |||

| In clubs and at tournaments, where large numbers of sets must be maintained (and usually purchased) by one organization, the expensive traditional sets are not usually used. For these situations, table boards (of the same design as floor boards, but only about 2–5 cm thick and without legs) are used, and the stones are made of glass rather than slate and shell. Bowls will often be plastic if wooden bowls are not available. ] stones could be used, but are considered inferior to ] as they are generally much lighter, and most players find that not even the lower price justifies their unpleasantness. | |||

| {{main|Go opening}} | |||

| Traditionally, the board's grid is 1.5 ] long by 1.4 shaku wide (455 mm by 424 mm) with space beyond to allow stones to be played on the edges and corners of the grid. This often surprises newcomers: it is not a perfect square, but is longer than it is wide, in the proportion 15:14. Two reasons are frequently given for this. One is that when the players sit at the board, the angle at which they view the board gives a foreshortening of the grid; the board is slightly longer between the players to compensate for this. Another suggested reason is that the Japanese ] finds structures with geometric symmetry to be in bad taste. | |||

| In the opening of the game, players usually play and gain territory in the corners of the board first, as the presence of two edges makes it easier for them to surround territory and establish the eyes they need.{{sfn|Ishigure|2006|pp=7–8}} From a secure position in a corner, it is possible to lay claim to more territory by extending along the side of the board.{{sfn|Otake|2002|p=2}} The opening is the most theoretically difficult part of the game and takes a large proportion of professional players' thinking time.{{sfn|Ishigure|2006|p=6}}{{sfn|Kageyama|2007|p=153}} The first stone played at a corner of the board is generally placed on the third or fourth line from the edge. Players tend to play on or near the 4–4 star point during the opening. Playing nearer to the edge does not produce enough territory to be efficient, and playing further from the edge does not safely secure the territory.{{sfn|Nihon Kiin|1973|p=7 (Vol. 2)}} | |||

| Traditional stones are made so that black stones are slightly larger in diameter than white; this is probably to compensate for the optical illusion created by contrasting colours that would make equal-sized white stones appear larger on the board than black stones. The difference is slight, and since its effect is to make the stones appear the same size on the board, it can be surprising to discover they are not. | |||

| In the opening, players often play established sequences called ], which are locally balanced exchanges;<ref name=Joseki>{{citation | last = Ishida | first = Yoshio | title = Dictionary of Basic Joseki| year = 1977 | publisher = Kiseido Publishing Company}}</ref> however, the joseki chosen should also produce a satisfactory result on a global scale. It is generally advisable to keep a balance between territory and influence. Which of these gets precedence is often a matter of individual taste. | |||

| The bowls for the stones are of a simple shape, like a flattened sphere with a level underside. | |||

| The lid is loose-fitting and is upturned before play as a tray to collect stones captured during the game. The bowls are usually made of turned wood, although small lidded baskets of woven bamboo or reeds make an attractive cheaper alternative. | |||

| === Middlegame and endgame === | |||

| The traditional manner to place a Go stone is to hold it between the tips of the outstretched index and middle fingers and then strike the board firmly to create a sharp click. Many consider the ] properties of the wood of the board to be quite important. The traditional ''goban'' will usually have its underside carved with a pyramid called a ''heso'' recessed into the board. Tradition holds that this is to give a better resonance to the stone's click, but the more conventional explanation is to allow the board to expand and contract without splitting the wood. A board is seen as more attractive when it is marked with slight dents from decades (or centuries) of stones striking the surface. | |||

| The middle phase of the game is the most combative, and usually lasts for more than 100 moves. During the middlegame, the players invade each other's territories, and attack formations that lack the necessary ''two eyes'' for viability. Such groups may be saved or sacrificed for something more significant on the board.<ref name="Think Big in Go">{{cite web|last1=David|first1=Ormerod|title=Thinking big in Go|url=http://gogameguru.com/thinking-big/|publisher=GoGameGuru|access-date=5 June 2014}}</ref> It is possible that one player may succeed in capturing a large weak group of the opponent's, which often proves decisive and ends the game by a resignation. However, matters may be more complex yet, with major trade-offs, apparently dead groups reviving, and skillful play to attack in such a way as to construct territories rather than kill.<ref name="Induction in Go">{{cite web|last1=David|first1=Ormerod|title=Go technique: Induction in the game of Go|url=http://gogameguru.com/go-technique-induction/|publisher=GoGameGuru|access-date=5 June 2014}}</ref> | |||

| The end of the middlegame and transition to the endgame is marked by a few features. Near the end of a game, play becomes divided into localized fights that do not affect each other,{{sfn|Müller|Gasser|1996|p=273}} with the exception of ''ko'' fights, where before the central area of the board related to all parts of it. No large weak groups are still in serious danger. Moves can reasonably be attributed some definite value, such as 20 points or fewer, rather than simply being necessary to compete. Both players set limited objectives in their plans, in making or destroying territory, capturing or saving stones. These changing aspects of the game usually occur at much the same time, for strong players. In brief, the middlegame switches into the endgame when the concepts of strategy and influence need reassessment in terms of concrete final results on the board. | |||

| == Rules == | == Rules == | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Rules of Go}} | ||

| Aside from the order of play (alternating moves, Black moves first or takes a handicap) and scoring rules, there are essentially only two rules in Go: | |||

| ] | |||

| * '''Liberty rule''' states that ''every stone remaining on the board must have at least one open point (a ''liberty'') directly orthogonally adjacent (up, down, left, or right)'', '''or''' ''must be part of a connected group that has at least one such open point (liberty) next to it. Stones or groups of stones which lose their last liberty are removed from the board.'' | |||

| * '''Repetition Rule''' (]) states that ''a stone on the board must never immediately repeat a previous position of a captured stone, thus only a move elsewhere on the board is permitted that turn.'' Since without this rule such a pattern of the two players repeating their prior moves (capturing stones in same places) could continue indefinitely, this rule prevents a stalemate. | |||

| Almost all other information about how the game is played is heuristic, meaning it is learned information about how the patterns of the stones on the board function, rather than a rule. Other rules are specialized, as they come about through different rulesets, but the above two rules cover almost all of any played game. | |||

| Although there are some minor differences between rulesets used in different countries,<ref name=RulesComparison>{{Citation | url = https://www.britgo.org/rules/compare.html | title = Comparison of some go rules | author = British Go Association | access-date = 2007-12-20}}</ref> most notably in Chinese and Japanese scoring rules,<ref>{{Citation | url=http://nrich.maths.org/public/viewer.php?obj_id=1470 | publisher = University of Cambridge | author = NRICH Team | title = Going First | access-date = 2007-06-16}}</ref> these differences do not greatly affect the tactics and strategy of the game. | |||

| Except where noted, the basic rules presented here are valid independent of the scoring rules used. The scoring rules are explained separately. ] for which there is no ready English equivalent are commonly called by their Japanese names. | |||

| === Basic rules === | === Basic rules === | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The two players, Black and White, take turns placing stones of their color on the intersections of the board, one stone at a time. The usual board size is a 19×19 grid, but for beginners or for playing quick games,{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|pp=3–4}} the smaller board sizes of 13×13{{sfn|Nihon Kiin|1973|p=22 (Vol. 1)}} and 9×9 are also popular.{{sfn|Moskowitz|2013|p=14}} | |||

| The board is empty to begin with.{{sfn|Lasker|1960|p=2}} Black plays first unless given a handicap of two or more stones, in which case White plays first. The players may choose any unoccupied intersection to play on except for those forbidden by the ] and ] rules (see below). Once played, a stone can never be moved and can be taken off the board only if it is ].{{sfn|Nihon Kiin|1973|p=23 (Vol. 1)}} A player may pass their turn, declining to place a stone, though this is usually only done at the end of the game when both players believe nothing more can be accomplished with further play. When both players pass consecutively, the game ends{{sfn|Fairbairn|2004|p=12}} and is then ]. | |||

| ===Liberties and capture=== | |||

| * Two players, ''black'' and ''white'', take turns placing a ''stone'' (game piece) on the ''points'' (intersections) of a 19 by 19 ''board'' (grid). Black moves first. | |||

| ] | |||

| * Stones must have ''liberties'' (empty adjacent points) to remain on the board. Stones connected by lines are called ''chains'', and share their liberties. | |||

| Vertically and horizontally adjacent stones of the same color form a chain (also called a ''string'' or ''group''),{{sfn|Fairbairn|2004|p=7}} forming a discrete unit that cannot then be divided.<ref>{{citation | url = http://nrich.maths.org/public/viewer.php?obj_id=1433 | title = Behind the Rules of Go | last = Matthews | first = Charles | publisher = University of Cambridge | access-date = 2008-06-09}}</ref> Only stones connected to one another by the lines on the board create a chain; stones that are diagonally adjacent are not connected. Chains may be expanded by placing additional stones on adjacent intersections, and they can be connected together by placing a stone on an intersection that is adjacent to two or more chains of the same color.<ref name="Go Board Game pdf">{{cite web|title=Go The Board Game|url=http://kopoint.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/go-the-game.pdf|access-date=20 August 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130725124759/http://kopoint.files.wordpress.com/2012/12/go-the-game.pdf|archive-date=25 July 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| * When a stone or a chain of stones is surrounded by opponent stones, so that it has no more liberties, it is ''captured'' and removed from the board. | |||

| * If a stone has no liberties as soon as it is played, but simultaneously removes the last liberty from one or more of the opponent's chains, the opponent's chains are captured and the played stone is not. | |||

| * '']'': A stone cannot be played on a particular point if doing so would recreate the board position that existed after the same player's previous turn. | |||

| * A player may ''pass'' instead of placing a stone. When both players pass consecutively, the game ends and is then ]. | |||

| A vacant point adjacent to a stone, along one of the grid lines of the board, is called a ''liberty'' for that stone.{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|p=12}}{{sfn|Fairbairn|2004|p=6}} Stones in a chain share their liberties.{{sfn|Fairbairn|2004|p=7}} A chain of stones must have at least one liberty to remain on the board. When a chain is surrounded by opposing stones so that it has no liberties, it is captured and removed from the board.{{sfn|Dahl|2001|p=206}} | |||

| A player's score is the number of empty points enclosed only by his stones plus the number of points occupied by his stones. The player with the higher score wins. (Note that there are other rulesets that count the score differently, yet almost always produce the same result.) For a more detailed treatment, see ]. | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| This is the essence of the game of Go. The risk of capture means that stones must work together to control territory, which makes the gameplay very complex and interesting. (Also see ].) | |||

| === Ko rule === | |||

| Go allows one to play not only ''even games'' (games between players of roughly equal strength) but also ''handicap games'' (games between players of unequal strength); see ]. | |||

| {{main|Ko fight}} | |||

| ] (black) at the end of the opening stage; white has developed a great deal of potential territory, while black has emphasized central influence.]] | |||

| <div class="thumb tright"> | |||

| <div class="thumbinner" style="width:161px; font-size: 100%;"> | |||

| {{Go board 5x5 | |||

| | ul| u| u| u| ur | |||

| | l| b| w| | r | |||

| | b| c| b1| w| r | |||

| | l| b| w| | r | |||

| | dl| d| d| d| dr|32}} | |||

| <div class="thumbcaption" style="font-size: 88%;"> | |||

| === Optional rules === | |||

| An example of a situation in which the ko rule applies | |||

| Optional Go rules may set the following: | |||

| </div> | |||

| * compensation points, almost always for the second player, see '']''; | |||

| </div> | |||

| * compensation stones placed on the board before alternate play, allowing players of different strengths to play interesting games (see ] for more information). | |||

| </div> | |||

| Players are not allowed to make a move that returns the game to the immediately prior position. This rule, called the ], prevents unending repetition (a stalemate).{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|pp=48–49}} As shown in the example pictured: White had a stone where the red circle was, and Black has just captured it by playing a stone at '''1''' (so the White stone has been removed). However, it is readily apparent that now Black's stone at '''1''' is immediately threatened by the three surrounding White stones. If White were allowed to play again on the red circle, it would return the situation to the original one, but the ''ko'' rule forbids that kind of endless repetition. Thus, White is forced to move elsewhere, or pass. If White wants to recapture Black's stone at '''1''', White must attack Black somewhere else on the board so forcefully that Black moves elsewhere to counter that, giving White that chance. If White's forcing move is successful, it is termed "gaining the ''sente''"; if Black responds elsewhere on the board, then White can retake Black's stone at '''1''', and the ''ko'' continues, but this time Black must move elsewhere. A repetition of such exchanges is called a ''ko fight''.{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|pp=144–147}} To stop the potential for ''ko fights'', two stones of the same color would need to be added to the group, making either a group of 5 Black or 5 White stones. | |||

| While the various rulesets agree on the ko rule prohibiting returning the board to an ''immediately'' previous position, they deal in different ways with the relatively uncommon situation in which a player might recreate a past position that is further removed. See {{section link|Rules of Go|Repetition}} for further information. | |||

| == Strategy == | |||

| {{main|Go strategy and tactics}} | |||

| Basic strategic aspects include the following: | |||

| * Connection: Keeping one's own stones connected means that fewer groups need defense. | |||

| * Cut: Keeping opposing stones disconnected means that the opponent needs to defend more groups. | |||

| * Life: This is the ability of stones to permanently avoid capture. The simplest way is for the group to surround two "eyes" (separate empty areas), so that filling one eye will not kill the group and is therefore suicidal. | |||

| * Death: The absence of life, resulting in the removal of a group. | |||

| *Invasion: Penetration into an opponents claimed territory as a means of swaying the balance of territory. | |||

| == |

=== Suicide === | ||

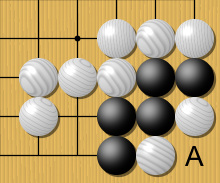

| ] website , {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130112214116/http://www.usgo.org/files/pdf/IngRules2006.pdf|date=12 January 2013}}, retrieved 5 August 2012</ref> and New Zealand rules,<ref name="AGA_rules">{{Cite web|title=The Rules of Go |website=American Go Association|url=https://www.usgo-archive.org/rules-of-go|access-date=5 August 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120711140721/http://www.usgo.org/rules-go|archive-date=11 July 2012}}</ref> White may play A, a suicide stone that kills itself and the two neighboring white stones, leaving an empty three-space eye. Black naturally answers by playing at A, creating two eyes to live.]] | |||

| Go is deep, as playing against any stronger player will demonstrate (] as established by ]). With each new level (rank) comes a deeper appreciation for the subtlety involved, and for the insight of stronger players. Beginners often start by randomly placing stones on the board, as if it were a game of chance — and they inevitably lose to experienced players. But soon an understanding of how stones connect to form strength develops, and shortly afterward a few basic ] may be understood. Learning the ways of ] helps to develop one's situational judgement. | |||

| A player may not place a stone such that it or its group immediately has no liberties unless doing so immediately deprives an enemy group of its final liberty. In the second case, the enemy group is captured, leaving the new stone with at least one liberty, so the new stone can be placed.{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|p=30}} This rule is responsible for the all-important difference between one and two eyes: if a group with only one eye is fully surrounded on the outside, it can be killed with a stone placed in its single eye. (An ] is an empty point or group of points surrounded by a group of stones). | |||

| Further experience yields an understanding of the board, the importance of the edges, then the efficiency of developing (in the corners first, then sides, then centre). Soon, the advanced beginner understands that territory and influence are somewhat interchangeable — but there needs to be a balance. Best is to develop more or less at the same pace as the opponent, in both territory and influence. This intricate struggle of power and control makes the game highly dynamic. | |||

| The ] and New Zealand rules do not have this rule,<ref name="Suicide in different rules.">{{cite web|title=Comparison of Some Go Rules|url=https://www.britgo.org/rules/compare.html|publisher=British Go Association|access-date=15 May 2014}}</ref> and there a player might destroy one of its own groups (commit suicide). This play would only be useful in limited sets of situations involving a small interior space or planning.{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|p=28}} In the example at right, it may be useful as a ]. | |||

| == Computers and Go == | |||

| {{main|Computer Go}} | |||

| === Komi === | |||

| Although much effort has gone in to programming ]s to play Go, even the strongest programs are no better than an average club player, and would easily be beaten by a strong player even getting a nine-stone handicap. Strong players have even beaten computer programs at handicaps of twenty-five stones. Of course, strong players do not currently have much interest in computer Go programs as opponents, as they do not yet play well enough. This is attributed to many qualities of the game, including the "]" nature of the victory condition, the large number of legal moves, the large board size, the nonlocal nature of the Ko rule, and the high degree of pattern recognition involved. On the other hand, a ]-playing computer, ], beat the world champion in ]. For this reason, many in the field of ] consider Go to be a better measure of a computer's capacity for thought than ]. | |||

| {{Main|Komi (Go)}} | |||

| Because Black has the advantage of playing the first move, the idea of awarding White some compensation came into being during the 20th century. This is called ], which gives white a 5.5-point compensation under Japanese rules, 6.5-point under Korean rules, and 15/4 stones, or 7.5-point under Chinese rules (number of points varies by rule set).<ref name="Komi Change">{{cite web|title=A change in Komi|url=http://www.usgo.org/aga-memo-regarding-komi|access-date=31 May 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221229064855/http://www.usgo.org/aga-memo-regarding-komi|archive-date=29 December 2022}}</ref> Under handicap play, White receives only a 0.5-point komi, to break a possible tie (''jigo''). | |||

| === Scoring rules === | |||

| On the other hand, none of these factors prevents computers from playing far better than human players in certain endgame situations, exactly as in the case of chess. In chess, this is due to the use of end game ]s; in Go, to an application of the kind of game analysis pioneered by ], who invented ]s to analyze games and Go endgames in particular, an idea much further developed in application to Go by ] and ]. It is outlined in their book, ''Mathematical Go'' (ISBN 1568810326). While not of general utility in most play, it greatly aids the analysis of certain classes of positions. | |||

| ] | |||

| Two general types of scoring procedures are used, and players determine which to use before play. Both procedures almost always give the same winner. | |||

| Use of computer networks to allow humans to meet, discuss games, and play one another, is becoming very common, with many strong players regularly playing online. See ''Additional Resources'' below for more information. | |||

| * '''Area scoring procedure (including Chinese):''' counts the number of points a player's stones occupy and surround. It is associated with contemporary Chinese play and was probably established there during the ] in the 15th or 16th century.<ref>{{cite web|work=New in Go|title=The rules debate as seen from Ancient China|last=Fairbairn|first=John|date=June 2006|publisher=Games of Go on Disc (GoGoD)|url=http://www.gogod.co.uk/NewInGo/C&IP.htm|access-date=2007-11-27|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130112213532/http://www.gogod.co.uk/NewInGo/C%26IP.htm|archive-date=2013-01-12}}</ref> Beginner-friendly, but takes longer to count. A player's score is the number of stones that the player has on the board, plus the number of empty intersections surrounded by that player's stones. If there is disagreement about which stones are dead, then under area scoring rules, the players simply resume play to resolve the matter. The score is computed using the position after the next time the players pass consecutively. | |||

| ==Other board games sometimes compared with Go== | |||

| * '''Territory scoring procedure (including Japanese and Korean):''' counts the number of empty points a player's stones surround, together with the number of stones the player captured. In the course of the game, each player retains the stones they capture, termed ''prisoners''. Any dead stones removed at the end of the game become prisoners. The score is the number of empty points enclosed by a player's stones, plus the number of prisoners captured by that player.{{efn|1=Exceptionally, in Japanese and Korean rules, empty points, even those surrounded by stones of a single color, may count as neutral territory if some of them are alive by seki. See the section below on ].}} Under territory scoring there can be an extra penalty for playing inside ones' territory, so if there is a disagreement extra play to resolve it would, in tournament settings, happen on a separate board, where the player claiming a group is dead would play first, and would demonstrate how to capture those stones. For further information, see ]. | |||

| This is a list of some games that are played with similar equipment or come from the same area. | |||

| Both procedures are counted after both players have passed consecutively, the stones that are still on the board but unable to avoid capture, called ''dead'' stones, are removed. Given that the number of stones a player has on the board is directly related to the number of prisoners their opponent has taken, the resulting net score, that is, the difference between Black's and White's scores is identical under both rulesets (unless the players have passed different numbers of times during the course of the game). Thus, the net result given by the two scoring systems rarely differs by more than a point.<ref>{{Citation | url = https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~wjh/go/rules/AGA.commentary.html | title = Demonstration of the Relationship of Area and Territory Scoring | first = Fred | last = Hansen | publisher = American Go Association | access-date = 2008-06-16}}</ref> | |||

| * Variations of chess | |||

| ** ] (Western): This game dominates Western game culture; its history in the culture stretches back many centuries. | |||

| ** ]: A cross between Go and Chess. In this game the pieces have the same movements as the Queen in Chess. After a player moves, the piece fires an arrow (that has the same movement as a Queen in Chess). An arrow blocks the paths of other pieces and arrows. The player who can move last wins. There can never be a draw. | |||

| ** ]: This is the Korean variant of Chess, usually called "Korean Chess". It is also very different from Go in game play. Go and Janggi are the two main board games played in Korea. | |||

| ** ] 将棋: Early Western literature often referred to Go as "Japanese Chess". The Japanese do have their own game called Shogi; it is much more similar to the other Chess variants than to Go. Shogi schools were founded in Japan about the same time as Go schools, and the game held more players throughout history than Go did. But Shogi is considered "lower class" compared with Go. Until recently, professional Go players in Japan often played Shogi as amateur and vice versa, but this habit has decreased because they now have no time to play other games. | |||

| ** ] 象棋: This is the Chinese variant of Chess, usually called "Chinese chess" by English speakers. Like most Chess variants, it has great depth of strategy, but bears few similarities to Go in game play. Xiangqi, like Go, is played on points rather than squares. | |||

| * Connection games. These are the most similar to Go in terms of style and strategy. One significant difference between Go and many connection games is the number of goals. In Hex, for example, there is only one goal: to connect your two sides. While this leads to significant strategic complexity (especially as the board size increases), in Go there are usually numerous different battles going on simultaneously. | |||

| ** ] and ] are connection games. Like Go, these have cutting and connecting tactics, but Hex is played on a hexagonal lattice. Mathematician ] independently invented a version of this game while at ], called Nash, in response to Go. | |||

| ** ], ], and ] are connection games similar to Hex, but of more depth. | |||

| *Played on a Go board | |||

| ** ]: Played with the same equipment as Go (a 19x19 grid, black and white stones), in these games the goal is to create six stones in a row. | |||

| ** ], ] and ]: Played with the same equipment as Go (a 19x19 grid, black and white stones), in these games the goal is to create five stones in a row. The game style is thus much shorter and involves less strategy than Go. | |||

| ** ]: Played with a Go board restricted to 15x19 grid, and black and white stones. The goal is to get the football (the white stone) across the respective goal line. | |||

| *Other similar-looking games | |||

| ** ] is a board game with black and white marbles. Strategy is somewhat of a cross between Reversi and Sumo wrestling, the goal being to push the other player's marbles off the playing surface. | |||

| ** ] is a Go-like game restricted to a single spatial ]. | |||

| ** ]: Marketed by ] as "Othello", Reversi bears superficial similarity to Go, with black and white circular pieces, an undifferentiated grid for a board, simple rules, and a goal of covering more of the board than the opponent. The game play is quite unlike Go, however, as it is based on flanking the opponent's pieces for capture. Captured pieces change their color. | |||

| == |

=== Life and death === | ||

| {{See also|Life and death}} | |||

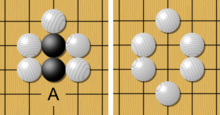

| ] | |||

| While not actually mentioned in the rules of Go (at least in simpler rule sets, such as those of New Zealand and the U.S.), the concept of a ''living'' group of stones is necessary for a practical understanding of the game.{{sfn|Matthews|2002|p={{page needed|date=May 2014}}}} | |||

| <div class="thumb tleft"> | |||

| Go has been mentioned in many novels and short stories published in the Orient, and occasionally turns up in Western media as well. | |||

| <div class="thumbinner" style="width:202px; font-size: 100%;"> | |||

| {{Goban 9x9 | |||

| |ulc| b| b| w| u| w| b| uc| b | |||

| | b| c| b| w| | w| b| b| rc | |||

| | b| b| w| w| | w| w| b| b | |||

| | w| w| w| | | | w| b| rc | |||

| | l| | | | | | w| b| b | |||

| | w| w| | | | | w| w| w | |||

| | b| w| w| w| w| | w| b| b | |||

| | lA| b| b| b| w| | w| b| rc | |||

| | b| b| dc| b| w| d| w| b| b|22}} | |||

| <div class="thumbcaption" style="font-size: 88%;"> | |||

| In ], ]-winning author ] published '']'', a short novel based upon an epic game that took place over the course of several months in ]. An English translation appeared in ], around the time of Kawabata's death. Go also features (as "Wéi-chí") as a favourite pastime of and philosophical inspiration for the archvillan Howard Devore in the ] novels by ]. | |||

| Examples of eyes (marked). The black groups at the top of the board are alive, as they have at least two eyes. The black groups at the bottom are dead as they only have one eye. The point marked ''a'' is a false eye, thus the black group with false eye ''a'' can be killed by white in two turns. | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| When a group of stones is mostly surrounded and has no options to connect with friendly stones elsewhere, the status of the group is either alive, dead or ''unsettled''. A group of stones is said to be alive if it cannot be captured, even if the opponent is allowed to move first. Conversely, a group of stones is said to be dead if it cannot avoid capture, even if the owner of the group is allowed the first move. Otherwise, the group is said to be unsettled: the defending player can make it alive or the opponent can ''kill'' it, depending on who gets to play first.{{sfn|Matthews|2002|p={{page needed|date=May 2014}}}} | |||

| Go is featured in the cold war thriller, ''Shibumi'' by ]. The central character spends his adolescence studying the game under a master, and the major chapters of the book reflect Go strategies. | |||

| An ] is an empty point or group of points surrounded by a group of stones. If the eye is surrounded by Black stones, White cannot play there unless such a play would take Black's last liberty and capture the Black stones. (Such a move is forbidden according to the suicide rule in most rule sets, but even if not forbidden, such a move would be a useless suicide of a White stone.) | |||

| Shan Sa, a Chinese writer who lives in France, wrote ''La Joueuse de Go'', where a Chinese girl plays Go with a Japanese soldier and wins, although they are both extremely strong players. | |||

| If a Black group has two eyes, White can never capture it because White cannot remove both liberties simultaneously. If Black has only one eye, White can capture the Black group by playing in the single eye, removing Black's last liberty. Such a move is not suicide because the Black stones are removed first. In the "Examples of eyes" diagram, all the circled points are eyes. The two black groups in the upper corners are alive, as both have at least two eyes. The groups in the lower corners are dead, as both have only one eye. The group in the lower left may seem to have two eyes, but the surrounded empty point marked ''a'' is not actually an eye. White can play there and take a black stone. Such a point is often called a ''false eye''.{{sfn|Matthews|2002|p={{page needed|date=May 2014}}}} | |||

| Go is featured in Scarlett Thomas's book ''PopCo''. Alice Butler, the main character, works for a giant toy company where games of Go are encouraged to spark creativity. | |||

| === Seki (mutual life) === | |||

| The world of the fantasy series ] has a similar game, called Stones, with a hexagonal base shape instead of square. | |||

| ] | |||

| <!-- DEPRECATED as too complex. | |||

| In the ] book ] by ], Go is played by the two protagonists when they are stuck in an ice tempest. | |||

| <div class="thumb tright"> | |||

| <div class="thumbinner" style="width:202px; font-size: 100%;"> | |||

| {{Goban 9x9 | |||

| | ul| b| b| w| u| w| u| u| ur | |||

| | b| | b| w| w| w| w| w| w | |||

| | b| b| w| w| b| b| b| b| b | |||

| | w| w| w| b| b| | b| | b | |||

| | b| b| b| w| b| b| b| b| b | |||

| | lc| c| b| w| w| w| w| w| b | |||

| | w| w| w| b| w| | w| b| b | |||

| | b| b| b| b| w| w| w| b| r | |||

| | dl| b| d| b| w| d| w| b| b|22}} | |||

| <div class="thumbcaption" style="font-size: 88%;"> | |||

| The book by Troy Anderson likens the game to a rosetta stone for understanding the underpinnings of strategy, especially for business. | |||

| Example of seki (mutual life). Neither Black nor White can play on the marked points without reducing their own liberties for those groups to one (self-atari). | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| – Above deprecated. --> | |||

| There is an exception to the requirement that a group must have two eyes to be alive, a situation called ''seki'' (or ''mutual life''). Where different colored groups are adjacent and share liberties, the situation may reach a position when neither player wants to move first because doing so would allow the opponent to capture; in such situations therefore both players' stones remain on the board (in seki). Neither player receives any points for those groups, but at least those groups themselves remain living, as opposed to being captured.{{efn|1=In game theoretical terms, seki positions are an example of a ].}} | |||

| Seki can occur in many ways. The simplest are: | |||

| In the webcomic ], the two main characters are occasionally seen discussing various subjects over a game of Go. | |||

| # each player has a group without eyes and they share two liberties, and | |||

| # each player has a group with one eye and they share one more liberty. | |||

| In the "Example of seki (mutual life)" diagram, the two circled points are liberties shared by both a black and a white group. Both of these interior groups are at risk, and neither player wants to play on a circled point, because doing so would allow the opponent to capture their group on the next move. The outer groups in this example, both black and white, are alive. Seki can result from an attempt by one player to invade and kill a nearly settled group of the other player.{{sfn|Matthews|2002|p={{page needed|date=May 2014}}}} | |||

| == Tactics == | |||

| The game of Go plays a part in the ] TV ], '']'' which references a piece of computer technology called a "Go chip." Go figures prominently in the introduction of '']'' to the mysterious character of Jurgen during an important character arc in the television series La Femme Nikita. The game also appeared in an episode of '']'' entitled "The Cogenitor" in which it was revealed that ] plays the game. In another ] show, '']'', Dylan Hunt and Gaheris Rhade both play a futuristic version of the game, apparently on three boards at once. During episode 15 of season 3 of the television show '']'', several scenes took place in an underground Chinese Go club uncharacteristically populated by beautiful women. The characters even called it a "Go club". A 1980s TV series called ''Chessgame'' starred ] as a spy master who would spend long periods studying a Go board. | |||

| {{Main|Go strategy and tactics}} | |||

| ''Tactics'' deal with immediate fighting between stones, capturing and saving stones, life, death and other issues localized to a specific part of the board. Larger issues which encompass the territory of the entire board and planning stone-group connections are referred to as ''Strategy'' and are covered in the ''Strategy'' section above. | |||

| '']'' is a ] and ] series, in which a boy is taught to play Go by the spirit of an ancient Go player. At the end of each episode in the original anime, there is a short segment of approximately three minutes where a simple concept of Go is taught. Through the first few episodes, a new player can be taught the concepts of the game in a very simple and easy to understand format. This segment appears to be mainly geared towards children. Hikaru No Go was extremely popular during its original run, and was also highly regarded by critics. A direct result of its success was that Go's popularity (which had been in decline for years in Japan) skyrocketed, especially amongst the young, and its popularity also increased in China and Korea. Today interest in the game remains relatively high, in large part thanks to this series. | |||

| === Capturing tactics === | |||

| In the ] and ] series "]", ] is mentioned to be a master at ] and Go. Although seemingly unmotivated and lazy, his intellect is proved when playing his sensei in these games. He never loses. In fact, a habit Shikimaru developed when playing ] and Go is even carried into his battles. | |||

| There are several tactical constructs aimed at capturing stones.{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|pp=80–98}} These are among the first things a player learns after understanding the rules. Recognizing the possibility that stones can be captured using these techniques is an important step forward. | |||

| <div class="thumb tright"> | |||

| <div class="thumbinner" style="width:202px; font-size: 100%;"> | |||

| {{Goban 9x9 | |||

| | ul| u| u| u| u| u| u| u| u | |||

| | l| | w| | | | | | | |||

| | l| w| b| w| | | | | | |||

| | l| w| b1| b3| w4| | | | | |||

| | l| | w2| b5| b7| w8| | | | |||

| | l| | | w6| b9| | | | | |||

| | l| | | | 10| | | | | |||

| | l| | | | | | | | | |||

| | l| | | | | | | | |22}} | |||

| <div class="thumbcaption" style="font-size: 88%;"> | |||

| One popular Chinese/Japanese movie is aka ''The Go Masters''. The movie depicts the time period when the Japanese army invaded China. The story begins when a Japanese Army Captain forces a famous Chinese Go player to play at a Go match. Due to resentment of the invasion, the Chinese player cuts off the finger that is used to hold Go stones. The story ends at a post-war time, where both the Japanese Captain and the Chinese Go player meet and play a peaceful game. | |||

| '''A ladder.''' Black cannot escape unless the ladder connects to black stones further down the board that will intercept with the ladder or if one of white's pieces has only one liberty. | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| The most basic technique is the ''ladder''.{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|pp=88–90}} This is also sometimes called a "running attack", since it unfolds as one player trying to outrun the other's attack. To capture stones in a ladder, a player uses a constant series of capture threats (atari), giving the opponent only one place to place his stone to keep his group alive. This forces the opponent to move into a zigzag pattern (surrounding the ladder on the outside) as shown in the adjacent diagram to keep the attack coming. Unless the pattern runs into friendly stones along the way, the stones in the ladder cannot avoid capture. However, if the ladder can run into other black stones, thus saving them, then experienced players recognize the futility of continuing the attack. These stones can also be saved if a suitably strong threat can be forced elsewhere on the board, so that two Black stones can be placed here to save the group. | |||

| Go was depicted in the films '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'' and '']'' among many others. See the for an extensive list. | |||

| <div class="thumb tleft"> | |||

| <div class="thumbinner" style="width:202px; font-size: 100%;"> | |||

| {{Goban 9x9 | |||

| | ul| u| u| u| u| u| u| u| u | |||

| | l| | b| | | | | | | |||

| | b| | b| w| w| | | | | |||

| | l| b| w| bT| w| | | | | |||

| | l| | w| bT| c| | | | | |||

| | l| | w| bT| c| | | | | |||

| | l| | w| c| w1| | | | | |||

| | l| | | | | | | | | |||

| | l| | | | | | | | |22}} | |||

| <div class="thumbcaption" style="font-size: 88%;"> | |||

| Go is depicted in the movie ]. | |||

| '''A net.''' The chain of three marked Black stones cannot escape in any direction, since each Black stone attempting to extend the chain outward (on the red circles) can be easily blocked by one White stone. | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| Another technique to capture stones is the so-called ''net'',{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|pp=91–92}} also known by its Japanese name, ''geta''. This refers to a move that loosely surrounds some stones, preventing their escape in all directions. An example is given in the adjacent diagram. It is often better to capture stones in a net than in a ladder, because a net does not depend on the condition that there are no opposing stones in the way, nor does it allow the opponent to play a strategic ladder breaker. However, the ladder only requires one turn to kill all the opponent's stones, whereas a net requires more turns to do the same. | |||

| <div class="thumb tright"> | |||

| ==The Go world== | |||

| <div class="thumbinner" style="width:202px; font-size: 100%;"> | |||

| ===Ranks=== | |||

| {{Goban 9x9 | |||

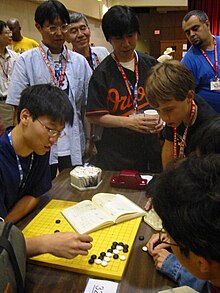

| ] in ], ].]] | |||

| | ul| u| u| u| u| u| u| u| u | |||

| {{main|Go ranks and ratings}} | |||

| | l| | | b| b| | | | | |||

| | l| | b| | | | | | | |||

| | l| | b| w| w| | | | | |||

| | l| | w| b| c| w| | | | |||

| | l| | w| b| w1| b| b| | | |||

| | l| | | w| b| | | | | |||

| | l| | | w| b| | | | | |||

| | l| | | | b| | | | |22}} | |||

| <div class="thumbcaption" style="font-size: 88%;"> | |||

| In countries where Go is popular, ranks are employed to indicate playing strength. | |||

| '''A snapback.''' Although Black can capture the white stone by playing at the circled point, the resulting shape for Black has only one liberty (at 1), thus White can then capture the three black stones by playing at '''1''' again (''snapback''). | |||

| From about the ], the Japanese formalised the teaching and ranking of Go. The system is comparable to that of ] schools; and is considered to be derived ultimately from court ranks in China. | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| </div> | |||

| A third technique to capture stones is the ''snapback''.{{sfn|Kim|Jeong|1997|pp=93–94}} In a snapback, one player allows a single stone to be captured, then immediately plays on the point formerly occupied by that stone; by so doing, the player captures a larger group of their opponent's stones, in effect ''snapping back'' at those stones. An example can be seen on the right. As with the ladder, an experienced player does not play out such a sequence, recognizing the futility of capturing only to be captured back immediately. | |||

| === Reading ahead === | |||

| Beginning players today start at a rank of between 25 and 30 ''kyu'' 級. The ''kyu'' ranking then decreases in magnitude as the player becomes stronger, dropping down to 1 ''kyu'' or 1k. Since beginners will commonly progress through elementary concepts quickly, it may be difficult to set a solid kyu ranking for new players. Players who have progressed through the ''kyu'' ranks and passed the 1 ''kyu'' mark are then ranked at 1 ''dan'' 段 or 1d, sometimes called ''shodan'' 初段. The player then could advance through the amateur ''dan'' ranks up to amateur 7 ''dan'', which only few players achieve. That playing level is roughly equivalent to where the ranks for professionals start with pro 1 ''dan'' going up to 9 ''dan'' (also sometimes called ''ping'' or ''p'' as in 9p to avoid confusion between a 1 dan professional and a weaker amateur 6 dan). The distinction between each amateur rank is, by definition, one handicap stone. Professional ranks are awarded by professional organizations and though they are less well defined, they are closer, so that an average 1p might need three handicap stones against a prime 9p (although they would play even games if they were to meet in a tournament). | |||

| One of the most important skills required for strong tactical play is the ability to read ahead.{{sfn|Davies|1995|p=5}} Reading ahead includes considering available moves to play, the possible responses to each move, and the subsequent possibilities after each of those responses. Some of the strongest players of the game can read up to 40 moves ahead even in complicated positions.<ref name=TreasureChest>{{citation | chapter = Memories of Kitani | title = The Treasure Chest Enigma | last = Nakayama | first = Noriyuki | publisher = Slate & Shell | year = 1984 | isbn = 978-1-932001-27-3 | pages =16–19}}</ref> | |||

| As explained in the scoring rules, some stone formations can never be captured and are said to be alive, while other stones may be in a position where they cannot avoid being captured and are said to be dead. Much of the practice material available to players of the game comes in the form of life and death problems, also known as ].<ref name=Tsumego>{{Citation | url = http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/dy/columns/0001/305.htm | last = van Zeijst | first = Rob | publisher = ] | title = Whenever a player asks a top professional ... | access-date = 2008-06-09 | archive-date = 2008-05-11 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080511122600/http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/dy/columns/0001/305.htm | url-status = dead}}</ref> In such problems, players are challenged to find the vital move sequence that kills a group of the opponent or saves a group of their own. Tsumego are considered an excellent way to train a player's ability at reading ahead,<ref name=Tsumego /> and are available for all skill levels, some posing a challenge even to top players. | |||

| Among amateur players, handicaps are determined by the difference in ranks. If a 3k and a 7k player were to play each other, the 7k player would place four handicap stones at the start of the game. Handicaps up to nine stones are common in club play, and correspond well to rank differences. In a small club, ranks may be decided informally and adjusted when players consistently win or lose. In a larger club, a mathematical ranking system gives better results. Players can then be promoted or demoted based on their strength as calculated from their wins and losses. | |||

| === |

=== Ko fighting === | ||

| ] | |||

| Like many other games, a game of Go may be timed. There are four typical methods of timing a game: | |||

| * ''Absolute'': a specific amount of time is given for the entire game, regardless of how fast or slow each player is. This is extremely rare. | |||

| * ''Byo-Yomi'' (''Japanese Timing''): After the main time is depleted, a player has a certain number of time periods (typically around 30 seconds). After each move, the number of time periods that the player took (possibly zero) is subtracted. For example, if a player has three 30-second time periods and takes 30 or more (but less than 60) seconds to make a move, he loses one time period. With 60-89 seconds, he loses two time periods, and so on. If, however, he takes less than 30 seconds, the timer simply resets without subtracting any periods. This is written as <maintime> + <byo-yomi time period>x<number of byo-yomi time periods>. | |||