| Revision as of 11:56, 30 May 2006 view sourceCentauri (talk | contribs)2,355 edits revert unexplained deletions by abusive editor + few minor corrections← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:31, 13 October 2024 view source ForsythiaJo (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users56,177 edits removed Category:Mass psychogenic illness; added Category:Mass psychogenic illness in Europe using HotCat | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|English legendary folklore character}} | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| {{about}} | |||

| {{pp-semi|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=November 2012}} <!-- This article uses ] --> | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox mythical creature | |||

| | name = Spring-heeled Jack | |||

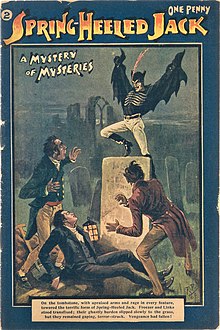

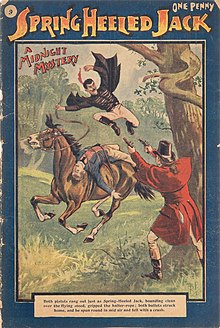

| | image = jack6.jpg | |||

| | caption = Spring Heeled Jack as depicted in the English ] ''Spring-Heeled Jack'' #2, Aldine Publishing, 1904 | |||

| | Grouping = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | Country = ] | |||

| | Region = ]<br>] | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Spring-heeled Jack ''' is an entity in ] of the ]. The first claimed sighting of Spring-heeled Jack was in 1837.<ref>Sharon McGovern ("The Legend of Spring Heeled Jack") claims that a letter to the editor of the ''Sheffield Times'' in 1808 talks of a ghost by that name years previously; McGovern neither specifies the day in 1808 so that the letter can be verified nor lists any secondary source (for this or anything else). In addition, the ''Sheffield Times'' did not launch until April 1846.</ref> Later sightings were reported all over the United Kingdom and were especially prevalent in suburban ], the ] and ].<ref>For an account of an incident from ] that was misinterpreted as a sighting of Spring-heeled Jack, see ''The Weekly Scotsman'', 16 January 1897.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Spring Heeled Jack''' (also ''Springheel Jack'', ''Spring-heel Jack'', etc.) is a character from ] said to have existed during the ]. | |||

| The first recorded claimed sighting of Spring Heeled Jack occurred in 1837. Later sightings were reported from all over ], from ] up to ] and ], but they were especially prevalent in ] London and later in the ], where they peaked between the 1850s and 1880s. | |||

| There are many theories about the nature and identity of Spring-heeled Jack. This ] was very popular in its time, due to the tales of his bizarre appearance and ability to make extraordinary leaps, to the point that he became the topic of several works of fiction. | |||

| Although some unconfirmed reports claim that Jack could still be active, he is generally believed to have disappeared after 1904, the year of the last recorded incident. Many theories have been proposed to ascertain his ] and ], none of which have been capable of clarifying the subject completely, and the ] still remains unexplained. | |||

| Spring-heeled Jack was described by people who claimed to have seen him as having a terrifying and frightful appearance, with diabolical ], clawed hands, and eyes that "resembled red balls of fire". One report claimed that, beneath a black cloak, he wore a helmet and a tight-fitting white garment like an ]. Many stories also mention a "Devil-like" aspect. Others said he was tall and thin, with the appearance of a ]. Several reports mention that he could breathe out blue and white flames and that he wore sharp metallic claws at his fingertips. At least two people claimed that he was able to speak comprehensible English. | |||

| The ] of Spring Heeled Jack gained immense popularity in its time due to the tales of his bizarre appearance and his capacity to perform extraordinary leaps, to the point that it became the topic of several works of ] and much speculation about possible ] origins. | |||

| == |

== History == | ||

| ===Precedents=== | |||

| Spring Heeled Jack was described by his victims as having a terrifying and frightful appearance, with ] ] that included clawed hands and eyes that "resembled red balls of fire". One of these victims also recounted that, beneath a black cloak, he wore a ] and a tight fitting white garment like an "]". Many depositions also mention a "]-like" aspect. Many witnesses stated that Spring Heeled Jack's physique was tall and thin, that he had the appearance of a gentleman, and that he was capable of effecting great leaps. Several reports mention that he could breathe blue and white flames from his mouth, and that he wore sharp metallic ]s at his fingertips. At least two testimonies denote that he was able to speak in comprehensible ]. | |||

| In the early 19th century, there were reports of ]s that stalked the streets of London. These human-like figures were described as pale; it was believed that they stalked and preyed on lone pedestrians. The stories told of these figures formed part of a distinct ghost tradition in London which, some writers have argued, formed the foundation of the later legend of Spring-heeled Jack.<ref name="History Today">Jacob Middleton, "An Aristocratic Spectre", ''History Today'' (February 2011)</ref> | |||

| The most important of these early entities was the ], which in 1803 and 1804 was reported in ] on the western fringes of London; it would later reappear in 1824. Another apparition, the Southampton ghost, was also reported as assaulting individuals in the night. This particular spirit bore many of the characteristics of Spring-heeled Jack, and was reported as jumping over houses and being over {{convert|10|ft|abbr=on}} tall.<ref name="History Today"/> | |||

| == History == | |||

| === Early reports === | === Early reports === | ||

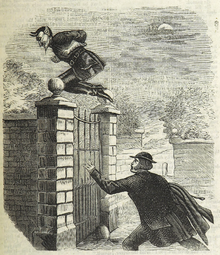

| ] |

] | ||

| The first alleged sightings of Spring-heeled Jack were made in London in 1837 and the last reported sighting is said in most of the secondary literature to have been made in ] in 1904.<ref name=scotsman1>David Cordingly, "", '']'' 7 October 2006. Excerpted from the '']''.</ref><ref name=cordingly1>Rupert Mann, "Spring Heeled Jack", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004; {{ISBN|019861411X}}).</ref> | |||

| Isolated accounts of a strange leaping man were in circulation as early as 1817 <sup id="fn_1_back">]</sup>, but the first confirmed sighting occurred in September 1837 in ]. A businessman returning home late one night from work was suddenly shocked as a mysterious figure jumped with ease over the considerably high railings of a cemetery, landing right in his path. No attack was reported, but the submitted description was disturbing: a muscular human male with devilish features, which included large and pointed ears and nose, and protruding, glowing eyes. | |||

| According to much later accounts, in October 1837 a girl by the name of Mary Stevens was walking to ], where she was working as a servant, after visiting her parents in ]. On her way through ], a strange figure leapt at her from a dark alley. After immobilising her with a tight grip of his arms, he began to kiss her face, while ripping her clothes and touching her flesh with his claws, which were, according to her deposition, "cold and clammy as those of a corpse". In panic, the girl screamed, making the attacker quickly flee from the scene. The commotion brought several residents who immediately launched a search for the aggressor, but he could not be found.<ref name="eehe">{{cite web |last1=Reed |first1=Peter |title=Spring-heeled Jack |url=https://eehe.org.uk/?p=33406 |website=Epsom and Ewell History Explorer |access-date=19 December 2021}}</ref> | |||

| Shortly after this incident, the same character leapt out of the darkness and attacked a group of passers-by <sup id="fn_2_back">]</sup>. He grabbed a woman, who managed to get away after getting her coat ripped, followed by her companions. One of them, however, a barmaid named Polly Adams, tripped and fell behind. Hours later, the police discovered her lying right where she was attacked. According to her statement, the assailant tore off the top of her blouse, and after grabbing her naked breasts, he deeply scratched her belly with his claws, leaving her unconscious and bloodied, but still alive. | |||

| The next day, the leaping character is said to have chosen a very different victim near Mary Stevens' home, inaugurating a method that would reappear in later reports: he jumped in the way of a passing ], causing the ] to lose control, crash, and severely injure himself. Several witnesses claimed that he escaped by jumping over a {{convert|9|ft|abbr=on}} high wall while cackling with a high-pitched, ringing laughter.<ref name="eehe" /> | |||

| Later, in October 1837, a girl by the name of Mary Stevens was walking to Lavender Hill, where she was working as a servant, after visiting her parents in ]. On her way through ], the strange figure leapt at her from a dark alley. After immobilising her with a tight grip of his arms, he began to kiss her face, while ripping her clothes and touching her flesh with his claws, which were according to her deposition ''"cold and clammy as those of a corpse"''. In panic, the girl screamed, making the attacker quickly flee from the scene of the assault. The commotion attracted several residents who launched an immediate search for the aggressor, but he was nowhere to be found. | |||

| Gradually, the news of the strange character spread, and soon the ] and the public gave him the name "Spring-heeled Jack".<ref>Clark, ''Unexplained!'' mentions{{page needed|date=August 2017}} that the press referred variously to "''Spring-heeled Jack''" or "''Springheel Jack''". Haining, ''The Legend and Bizarre Crimes of Spring Heeled Jack'', asserts that the term ''"springald"'' was rather the origin of the name Spring Heeled Jack, to which it evolved later; alas, there is no proof to support this claim, according to Clark. Dash, op. cit.,<!-- WHICH ONE? --> reveals that there is no contemporary evidence that this term was used in the 1830s, and establishes that the first original name was "''Steel Jack''{{-"}}, a possible reference to his supposed armoured appearance.</ref> | |||

| The next day, the leaping character chose a very different victim near Mary Stevens' home, inaugurating a ] that would become typical of his future deeds: he jumped in the way of a passing ], causing the coachman to lose control and crash, injuring him seriously. Several witnesses claimed that he escaped by jumping over a nine foot-high wall, while babbling with a high-pitched and ringing laughter. | |||

| A few days later, another woman was attacked near the ] churchyard. For the first time, police investigators discovered evidence at the scene of the crime: two footprints about three inches deep, which implied that they may have been made by someone who had landed from a great height. Upon a closer inspection, some curious imprints were found within the impressions, which suggested that the attacker had been wearing some sort of gadget on his shoes, ''"perhaps some kind of compressed springs"'' in the opinion of a present police officer. In spite of its importance, the lack of ] investigators in those days made the police forget about such evidence, and instead of making plaster casts of the impressions, they simply allowed the weather to erode them. Gradually, the news of the strange character spread, and soon the ] and the public gave him a name: '''Spring Heeled Jack''' <sup id="fn_3_back">]</sup>. | |||

| === Official recognition === | === Official recognition === | ||

| ] A few months after these first sightings, on 9 January 1838, the ], ], revealed at a public session held in the ] an anonymous complaint that he had received several days earlier, which he had withheld in the hope of obtaining further information. The correspondent, who signed the letter "a resident of ]", wrote: | |||

| {{quote|It appears that some individuals (of, as the writer believes, the highest ranks of life) have laid a wager with a mischievous and foolhardy companion, that he durst not take upon himself the task of visiting many of the villages near London in three different disguises—a ghost, a bear, and a ]; and moreover, that he will not enter a gentleman's gardens for the purpose of alarming the inmates of the house. The wager has, however, been accepted, and the unmanly villain has succeeded in depriving seven ladies of their senses, two of whom are not likely to recover, but to become burdens to their families. | |||

| ] A few months later, on ] ], the ], Sir John Cowan, revealed at a public session held in the ] an anonymous complaint that he had received several days earlier, which he had withheld in the hope of obtaining further information. The correspondent, who signed the letter "a resident of ]", wrote: | |||

| At one house the man rang the bell, and on the servant coming to open door, this worse than brute stood in no less dreadful figure than a spectre clad most perfectly. The consequence was that the poor girl immediately swooned, and has never from that moment been in her senses. | |||

| :''"It appears that some individuals (of, as the writer believes, the highest ranks of life) have laid a wager with a mischievous and foolhardy companion, that he durst not take upon himself the task of visiting many of the villages near London in three different disguises — a ghost, a bear, and a devil; and moreover, that he will not enter a gentleman's gardens for the purpose of alarming the inmates of the house. The wager has, however, been accepted, and the unmanly villain has succeeded in depriving seven ladies of their senses, two of whom are not likely to recover, but to become burdens to their families.'' | |||

| The affair has now been going on for some time, and, strange to say, the papers are still silent on the subject. The writer has reason to believe that they have the whole history at their finger-ends but, through interested motives, are induced to remain silent.<ref>As quoted by Jacqueline Simpson, ''Spring-Heeled Jack'' (2001).</ref>}} | |||

| :''At one house the man rang the bell, and on the servant coming to open door, this worse than brute stood in no less dreadful figure than a spectre clad most perfectly. The consequence was that the poor girl immediately swooned, and has never from that moment been in her senses.'' | |||

| Though the Lord Mayor seemed fairly sceptical, a member of the audience confirmed that "servant girls about ], Hammersmith and ], tell dreadful stories of this ghost or devil". The matter was reported in '']'' on 9 January, other national papers on 10 January and, on the day after that, the Lord Mayor showed a crowded gathering a pile of letters from various places in and around London complaining of similar "wicked pranks". The quantity of letters that poured into the Mansion House suggests that the stories were widespread in suburban London. One writer said several young women in Hammersmith had been frightened into "dangerous fits" and some "severely wounded by a sort of claws the miscreant wore on his hands". Another correspondent claimed that in ], ], ] and ] several people had died of fright and others had had fits; meanwhile, another reported that the trickster had been repeatedly seen in ] and ].{{citation needed|date=June 2017}} | |||

| :''The affair has now been going on for some time, and, strange to say, the papers are still silent on the subject. The writer has reason to believe that they have the whole history at their finger-ends but, through interested motives, are induced to remain silent."'' <sup id="fn_4_back">]</sup> | |||

| The Lord Mayor himself was in two minds about the affair: he thought "the greatest exaggerations" had been made, and that it was quite impossible "that the ghost performs the feats of a devil upon earth", but on the other hand someone he trusted had told him of a servant girl at ] who had been scared into fits by a figure in a bear's skin; he was confident the person or persons involved in this "] display" would be caught and punished.<ref>Peter Haining, ''The Legend and Bizarre Crimes of Spring Heeled Jack'', based on reports from '']'' of 10 and 12 January 1838.</ref> The police were instructed to search for the individual responsible, and rewards were offered.{{citation needed|date=June 2017}} | |||

| Though the Lord Mayor seemed fairly skeptical, a member of the audience confirmed, ''"servant girls about ], ] and ], tell dreadful stories of this ] or ]"''. The matter was reported in '']'' and other national papers the next day, and the day after that (]) the Lord Mayor showed a crowded gathering a pile of letters from various places in and around London complaining of similar "wicked pranks". The quantity of letters that poured into the Mansion House suggests that the activities of Spring Heeled Jack were common knowledge in suburban London by that time. One writer said he had ascertained that several young women in Hammersmith had been frightened into "dangerous fits", and some ''"severely wounded by a sort of claws the miscreant wore on his hands"''. Another correspondent affirmed that in ], ], ] and ] several people had died of fright, and others had had fits; meanwhile, another reported that the trickster had been repeatedly seen in ] and ], but the police were too frightened of him to act. | |||

| A peculiar report from ''The Brighton Gazette'', which appeared in the 14 April 1838 edition of ''The Times'', related how a gardener in Rosehill, Sussex, had been terrified by a creature of unknown nature. ''The Times'' wrote that "Spring-heeled Jack has, it seems, found his way to the Sussex coast", even though the report bore little resemblance to other accounts of Jack. The incident occurred on 13 April, when it appeared to a gardener "in the shape of a bear or some other four-footed animal". Having attracted the gardener's attention by a growl, it then climbed the garden wall and ran along it on all fours, before jumping down and chasing the gardener for some time. After terrifying the gardener, the apparition scaled the wall and made its exit.<ref>{{cite news|newspaper=] |title=The Whitechapel murder |page=7 |date=14 April 1838 |url=http://archive.timesonline.co.uk |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081006085903/http://archive.timesonline.co.uk/ |archive-date=6 October 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| The Lord Mayor himself was in two minds about the affair: he thought "the greatest exaggerations" had been made, and that it was quite impossible ''"that the ghost performs the feats of a devil upon earth"'', but on the other hand someone he trusted had told him of a servant girl at ] who had been scared into fits by a figure in a bear's skin; he was confident the person or persons involved in this "pantomime display" would be caught and punished <sup id="fn_5_back">]</sup>. The police were instructed to search for the individual responsible for the attacks, and rewards were offered. Many individuals, including Admiral ] decided to join the search, but to no avail: he was never caught. Furthermore, he seemed to have grown bolder, and his attacks multiplied. | |||

| === |

=== Scales and Alsop reports === | ||

| ] | |||

| Perhaps the best known of the alleged incidents involving Spring-heeled Jack were the attacks on two teenage girls, Lucy Scales and Jane Alsop. The Alsop report was widely covered by the newspapers, including a piece in '']'',<ref name=oldford>{{cite news | title = The Late Outrage at Old Ford | work = ] | date = 2 March 1838 | url = http://archive.timesonline.co.uk | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081006085903/http://archive.timesonline.co.uk/ | url-status = dead | archive-date = 6 October 2008 }}</ref> while fewer reports appeared in relation to the attack on Scales. The press coverage of these two attacks helped to raise the profile of Spring-heeled Jack.{{citation needed|date=June 2017}} | |||

| ====Alsop case==== | |||

| ].]] Perhaps the best known incidents involving Spring Heeled Jack were his attacks on two teenage girls, Lucy Scales <sup id="fn_6_back">]</sup> and Jane Alsop. The Alsop event was widely reported by the newspapers, while a single report appeared on the Scales' attack, presumably because Alsop came from a comfortably well-off family whereas Scales came from a family of tradesmen. This coverage by newspapers fueled the ] surrounding the case. | |||

| Jane Alsop reported that on the night of 19 February 1838, she answered the door of her father's house to a man claiming to be a police officer, who told her to bring a light, claiming "we have caught Spring-heeled Jack here in the lane". She brought the person a candle, and noticed that he wore a large cloak. The moment she had handed him the candle, however, he threw off the cloak and "presented a most hideous and frightful appearance", vomiting blue and white flame from his mouth while his eyes resembled "red balls of fire". Miss Alsop reported that he wore a large helmet and that his clothing, which appeared to be very tight-fitting, resembled white oilskin. Without saying a word he caught hold of her and began tearing her gown with his claws which she was certain were "of some metallic substance". She screamed for help, and managed to get away from him and ran towards the house. He caught her on the steps and tore her neck and arms with his claws. She was rescued by one of her sisters, after which her assailant fled.<ref name=scotsman1/><ref name=burke>{{cite book | last = Burke | first = Edmund | author-link = Edmund Burke |author2=Ivison Stevenson | title = The Annual Register of World Events: A Review of the Year | publisher = Longmans, Green | year = 1839 | location = London | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=sdkHAAAAIAAJ&q=spring-heeled | page = 23 }}</ref> | |||

| ====Scales case==== | |||

| On ], 18-year-old Jane Alsop opened the door of her father's house in the district of ] to a man claiming to be a police officer, who asked her to bring a light because he and other policemen had ''"caught Spring Heeled Jack in the lane"'', but this man then attacked her, tearing at her dress and hair until other members of her family ran to help her. She told the ] police investigators that ''"he was wearing a kind of helmet, and a tight fitting white costume like an oilskin. His face was hideous; his eyes were like balls of fire. His hands had claws of some metallic substance, and he vomited blue and white flames."'' | |||

| On 28 February 1838,<ref>'']'' of 7 March 1838, in Mike Dash, 'Spring-heeled Jack', ''Fortean Studies'' 3, p.pp.62–3</ref> nine days after the attack on Miss Alsop, 18-year-old Lucy Scales and her sister were returning home after visiting their brother, a butcher who lived in a respectable part of ]. Miss Scales stated in her deposition to the police that as she and her sister were passing along Green Dragon Alley, they observed a person standing in an angle of the passage. She was walking in front of her sister at the time, and just as she came up to the person, who was wearing a large cloak, he spurted "a quantity of blue flame" in her face, which deprived her of her sight, and so alarmed her, that she instantly dropped to the ground, and was seized with violent fits which continued for several hours.<ref name="Burke, pp. 26-27">Burke, </ref> | |||

| Her brother added that on the evening in question, he had heard the loud screams of one of his sisters moments after they had left his house and on running up Green Dragon Alley he found his sister Lucy on the ground in a fit, with her sister attempting to hold and support her. She was taken home, and he then learned from his other sister what had happened. She described Lucy's assailant as being of tall, thin, and gentlemanly appearance, covered in a large cloak, and carrying a small lamp or bull's eye lantern similar to those used by the police. The individual did not speak nor did he try to lay hands on them, but instead walked quickly away. Every effort was made by the police to discover the author of these and similar outrages, and several persons were questioned, but were set free.<ref name="Burke, pp. 26-27"/> | |||

| On ], once again a black-cloaked figure knocked on the door of a house, this time in Turner Street, off Commercial Road. When a servant boy answered the call, the visitor asked to speak to the master of the house, a Mr. Ashworth. The boy turned to call his master when he noticed that the man standing at the doorway had glowing red eyes. In a state of panic, he screamed, attracting the attention of the neighbours. With an angry and frustrated groan, Spring Heeled Jack waved his clawed fist at the boy's face and darted over the nearby rooftops. At the following interrogation by the authorities, the child claimed that he had noticed what became a significant piece of evidence: as Spring Heeled Jack was turning his back at him, he observed that he had a golden embroidered letter "''W''" on his shirt beneath the black cloak, much like a ]. | |||

| === Popularisation === | |||

| Five days later ], ] <sup id="fn_7_back">]</sup>, 18-year-old Lucy Scales and her sister were returning home after visiting their brother, a butcher who lived in a respectable part of the district of ]. Lucy, slightly ahead of her sister, was half way along Green Dragon Alley when a character, who had been waiting at an angle in the passage while she approached, appeared and attacked her. The figure breathed fire into Lucy's face and then bounded away as the girl fell to the ground, seized by violent spasms which lasted for several hours. Four witnesses attested that the attacker escaped by leaping from the ground to the roof of a nearby house on a single jump. A few days later, on ], Lucy's and her sister made their deposition at Lambeth–street police court in company of their brother, William. <sup id="fn_8_back">]</sup>. | |||

| ''The Times'' reported the alleged attack on Jane Alsop on 2 March 1838 under the heading "The Late Outrage at Old Ford".<ref name=oldford/> This was followed with an account of the trial of one Thomas Millbank, who, immediately after the reported attack on Jane Alsop, had boasted in the Morgan's Arms that he was Spring-heeled Jack. He was arrested and tried at Lambeth Street court. The arresting officer was James Lea, who had earlier arrested William Corder, the ]er. Millbank had been wearing white ]s and a ], which he dropped outside the house, and the candle he dropped was also found. He escaped conviction only because Jane Alsop insisted her attacker had breathed fire, and Millbank admitted he could do no such thing. Most of the other accounts were written long after the date; contemporary newspapers do not mention them.{{citation needed|date=June 2017}} | |||

| ] (1886)]] | |||

| After these incidents, Spring-heeled Jack became one of the most popular characters of the period. His alleged exploits were reported in the newspapers and became the subject of several ]s and plays performed in the cheap theatres that abounded at the time. The devil was even renamed "Spring-heeled Jack" in some ] shows, as recounted by ] in his '']'': | |||

| {{Quote|This here is Satan, – we might say the devil, but that ain't right, and gennelfolks don't like such words. He is now commonly called 'Spring-heeled Jack;' or the 'Rossian Bear,' – that's since the war.|Henry Mayhew|''London Labour and the London Poor'', p. 52<ref>{{cite book | last = Mayhew | first = Henry | author-link = Henry Mayhew | title = London labour and the London poor | publisher = Griffin, Bohn, and Company | year = 1861 | location = London | url = https://archive.org/details/londonlabourand01mayhgoog | page = }}</ref>}} | |||

| === The legend spreads === | |||

| The Times reported under the heading "Outrage at Old Ford" the attack on Jane Alsop. This was followed up (see Palmer's index to The Times) with the account of the trial of one Thomas Millbank, who, immediately after the attack on Jane Alsop, had boasted in the Morgan's Arms that he was Spring-heeled Jack. He was arrested and tried at Lambeth Street court. The arresting officer was Jonas Lea, who had earlier, as a PC, arrested William Cawder, the Red Barn murderer. Millbank had been wearing white overalls and a greatcoat, which he dropped outside the house, and the candle he dropped was also found. He escaped conviction only because Jane Alsop insisted her attacker had breathed fire, and Millbank admitted he could do no such thing. There is little doubt that this, the best documented of all Jack's activities, was the work of a drunken carpenter. Most of the other accounts were written long after the date. Contemporary newspapers do not mention them at all. | |||

| ] (1886).]]After these incidents, Spring Heeled Jack became one of the most popular characters of the moment. His exploits were reported in the newspapers and became the subject of several ]s and plays performed in the cheap theatres that abounded at the time. But, as his fame was growing, his appearances became less frequent, while spreading over a large area. In 1843, however, a wave of sightings swept the country again. Then he appeared in ], in ], where he was described as ''"the very image of the ] himself, with horns and eyes of flame"'', and in ], where reports of attacks to drivers of mail coaches became common. | |||

| But, even as his fame was growing, reports of Spring-heeled Jack's appearances became less frequent if more widespread. In 1843, however, a wave of sightings swept the country again. A report from ] described him as "the very image of the Devil himself, with horns and eyes of flame", and in ] reports of attacks on drivers of ]es became common. In July 1847 "a Spring-heeled Jack investigation" in Teignmouth, Devon led to a Captain Finch being convicted of two charges of assault against women during which he is said to have been "disguised in a skin coat, which had the appearance of bullock's hide, skullcap, horns and mask".<ref>{{cite news |url=http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71608928 |title=British And Foreign Gleanings. |newspaper=] |location=Adelaide |date=27 July 1847 |access-date=21 August 2013 |page=4 |publisher=National Library of Australia}}</ref> The legend was linked with the phenomenon of the "]" which appeared in ] in February 1855.{{citation needed|date=June 2017}} | |||

| Although terrifying citizens with his apparitions and in some occasions causing injuries of diverse consideration to his victims, so far Spring Heeled Jack had never killed a person. However, that changed in 1845. That year, he was seen at Jacob's Island, ], a low class slum of decaying wooden houses and full of pestilent ditches, which had been immortalised by ] as the lair of ] and his band of child thieves in '']''. He was said to have cornered a 13-year-old prostitute named Maria Davis on a narrow bridge that crossed one of the foulest ditches in the neighbourhood, called Folly Ditch, breathed fire into her face and hurled her into the stinking waters below.{{fact}} Witnesses reported the affair to the police, who dragged the ditch and recovered the girl's body. The verdict at the subsequent inquest was one of death by misadventure, but the inhabitants of the area branded Spring Heeled Jack as a murderer. | |||

| === |

=== Last reports === | ||

| In the beginning of the 1870s, Spring-heeled Jack was reported again in several places distant from each other. In November 1872, the '']'' reported that Peckham was "in a state of commotion owing to what is known as the "Peckham Ghost", a mysterious figure, quite alarming in appearance". The editorial pointed out that it was none other than "Spring-heeled Jack, who terrified a past generation".<ref>News of the World, 17 November 1872, cited in "Fortean Studies volume 3" (1996), pp. 78–79, ed. Steve Moore, John Brown Publishing</ref> Similar stories were published in '']''. In April and May 1873, it reported there were numerous sightings in ] of the "Park Ghost", which locals also came to identify as Spring-heeled Jack.<ref>The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes By Michael Newton pp. 355</ref> | |||

| ====Aldershot==== | |||

| In the beginning of the 1870s, Spring Heeled Jack began to appear repeatedly again in several places distant from each other. In November 1872, the '']'' reported that Peckham was ''"in a state of commotion owing to what is known as the "Peckham Ghost", a mysterious figure, quite alarming in appearance"''. The editorial pointed that it was no other than ''"Spring Heeled Jack, who terrified a past generation"''. Similar stories were published in the ''Illustrated Police News''. In April and May of 1873, there were numerous sightings of the "Park Ghost" in ], which locals came to identify as Spring Heeled Jack. These incidents culminated with thousands of people gathering each night to hunt the ghost. | |||

| ] as it looked in 1866.]] | |||

| This news was followed by more reported sightings, until in August 1877 one of the most notable reports about Spring-heeled Jack came from a group of soldiers in ]. This story went as follows: a sentry on duty at the North Camp peered into the darkness, his attention attracted by a peculiar figure "advancing towards him." The soldier issued a challenge, which went unheeded, and the figure came up beside him and delivered several slaps to his face. A guard shot at him, with no visible effect; some sources claim that the soldier may have fired ] at him, others that he missed or fired warning shots. The strange figure then disappeared into the surrounding darkness "with astonishing bounds."<ref>"The Aldershott Ghost", ''The Times'', 28 April 1877 (cited in "Fortean Studies volume 3" (1996), p. 95, ed. Steve Moore, John Brown Publishing)</ref><ref>"Our Camp Letter" – ''Surrey and Hants News & Guildford Times'' – 17 March 1877, section ''Aldershot Gazette''</ref><ref>], ''Haunted Britain'' – Consul Books (1963) p. 89</ref> | |||

| ]'s 1922 memoir ''Forty Years On'' mentions the Aldershot appearances of Spring-heeled Jack; however, he (apparently erroneously) says that they occurred in the winter of 1879 after his regiment, the ], had moved to Aldershot, and that similar appearances had occurred when the regiment was barracked at ] in the winter of 1878. He adds that the panic became so great at Aldershot that sentries were issued ammunition and ordered to shoot "the night terror" on sight, following which the appearances ceased. Hamilton thought that the appearances were actually pranks, carried out by one of his fellow officers, a Lieutenant Alfrey.<ref>{{cite book | last = Hamilton | first = Ernest | author-link = Lord Ernest Hamilton | title = Forty Years On | publisher = Hodder and Stoughton | year = 1922 | pages = –164 | url = https://archive.org/details/fortyyearson00hami }}</ref><ref>"Our Camp Letter" – ''Surrey and Hants News & Guildford Times'' – 14 December 1878, section ''Aldershot Gazette''</ref> However, there is no record of Alfrey ever being court-martialled for the offence.<ref>Judge Advocate General's Office: General Courts Martial charge sheets: 1877–1880 – the National Archives, Kew</ref> | |||

| ]This news was followed by more sighting reports, until in August 1877, Spring Heeled Jack made one of his most notable appearances before a group of soldiers in ]'s barracks. A ] on duty at the North Camp peered into the darkness, his attention attracted by a peculiar figure bounding across the road towards him, making a metallic noise. The soldier issued a challenge, which went unheeded, and the figure vanished from sight for a few moments. As the soldier turned back to his post, the figure reappeared beside him and delivered several slaps to his face with ''"a hand as cold as that of a corpse"''. Attracted by the ensuing noise, several men rushed to the place, but they claimed that the character leapt several feet over their heads and landed behind them. According to their testimony, Spring Heeled Jack simply stood there, watching them and grinning, apparently waiting their reaction with glee. One of the guards shot at him, with no visible effect other than to enrage his target; some sources note the fact that the soldier may have fired ]s at him, merely used to make warning shots. The strange figure then charged towards them and spat blue flames at them from his mouth, making the guards desert their posts in panic and then disappearing into the surrounding darkness. | |||

| ====Lincolnshire==== | |||

| There were several more attacks of Spring Heeled Jack on guards at Aldershot. All these sightings concurred in the description: tall, muscular complexion, wearing a helmet and a white tight fitting oilskin suit. | |||

| In the autumn of 1877, Spring-heeled Jack was reportedly seen at ], in ], ], wearing a sheep skin. An angry mob supposedly chased him and cornered him, and just as in Aldershot a while before, residents fired at him to no effect. As usual, he was said to have made use of his leaping abilities to lose the crowd and disappear once again.<ref>Illustrated Police News, 3 November 1877, cited in "Fortean Studies volume 3" (1996), pp. 96, ed. Steve Moore, John Brown Publishing</ref> | |||

| ====Liverpool==== | |||

| After these incidents, a massive spree of Spring Heeled Jack's sightings hit all England. In ], he was seen leaping over several houses, wearing a sheep skin. An angry mob chased him and cornered him, and just like in Aldershot a while before, residents uselessly fired at him. Many witnesses claimed that the shots did hit him, sounding as they were hitting a hollow metallic object, like an "empty bucket". As usual, he made use of his leaping abilities to lose the crowd and disappear once again. | |||

| By the end of the 19th century the reported sightings of Spring-heeled Jack were moving towards the north west of England. Around 1888, in ], north Liverpool, he allegedly appeared on the rooftop of ] in Salisbury Street. In 1904 there were reports of appearances in nearby William Henry Street.<ref>News of the World, 25 September 1904, cited in "Fortean Studies volume 3" (1996), pp. 97, ed. Steve Moore, John Brown Publishing</ref> | |||

| ===Aftermath and impact upon Victorian popular culture=== | |||

| ]By the end of the 19th century, the geographical pattern of sightings of Spring Heeled Jack indicated that he was moving towards western England. In September 1904, in ], in north ], Spring Heeled Jack appeared on the rooftop of ], in Salisbury Street. Witnesses reported that he suddenly jumped and fell to the ground, landing behind a nearby house. When they rushed to the point, they faced there a tall and muscular man, fully dressed in white and wearing an "egg shaped" helmet, standing there waiting. He laughed hysterically at the crowd and rushed towards them, making several women gasp in dismay. Clearing them all with a gigantic leap, he disappeared behind the neighbouring houses. | |||

| The vast urban legend built around Spring-heeled Jack influenced many aspects of Victorian life, especially in contemporary ]. For decades, especially in London, his name was equated with the ], as a means of scaring children into behaving by telling them if they were not good, Spring-heeled Jack would leap up and peer in at them through their bedroom windows, by night. | |||

| However, it was in fictional entertainment where the legend of Spring-heeled Jack exerted the most extensive influence, owing to his allegedly extraordinary nature. Three pamphlet publications, purportedly based on the real events, appeared almost immediately, during January and February, 1838. They were not advertised as fiction, though they likely were at least partly so. The only known copies were reported to have perished when the ] was hit during ], but their catalogue still lists the first one. | |||

| The Liverpool incident is usually considered the last time Spring Heeled Jack was ever seen. Although there have been reports of later sightings as recently as 1986, some of them outside England (even in the ]), such claims are too scarce and ambiguous to be confirmed. | |||

| The character was written into a number of ] stories during the latter half of the 19th century, initially as a villain and then in increasingly heroic roles. By the early 1900s he was being represented as a costumed, altruistic avenger of wrongs and protector of the innocent, effectively becoming a precursor to ] and then ] ]. | |||

| ==Theories== | ==Theories== | ||

| No one was ever caught and identified as Spring-heeled Jack; combined with the extraordinary abilities attributed to him and the very long period during which he was reportedly at large, this has led to numerous and varied theories of his nature and identity. While several researchers seek a normal explanation for the events, other authors explore the more fantastic details of the story to propose different kinds of ] speculation. | |||

| ===Sceptical positions=== | |||

| The fact that Spring Heeled Jack was never caught, combined with the extraordinary abilities attributed to him and the very long period of time he was at large, have led to all sorts of theories to determine both his nature and identity. While several researchers seek a ] explanation to the events, other authors echo themselves in the more fantastic details of the story to propose different kinds of ] speculations. | |||

| Sceptical investigators have dismissed the stories of Spring-heeled Jack as ] which developed around various stories of a ] or devil which have been around for centuries, or from exaggerated urban myths about a man who clambered over rooftops claiming that the Devil was chasing him.<ref>Randles, ''Strange and Unexplained Mysteries of the 20th Century''</ref> | |||

| ], 3rd Marquess of Waterford (1840)]] | |||

| ===Skeptical positions=== | |||

| Other researchers believe that some individual(s) may have been behind its origins, being followed by imitators later on.<ref name="ReferenceA">Dash, "Spring Heeled Jack", in ''Fortean Studies'', ed. Steve Moore.</ref> Spring-heeled Jack was widely considered not to be a supernatural creature, but rather one or more persons with a macabre sense of humour.<ref name=scotsman1/> This idea matches the contents of the letter to the Lord Mayor, which accused a group of young aristocrats as the culprits, after an irresponsible wager.<ref name=scotsman1/> A popular rumour circulating as early as 1840 pointed to an ], ], as the main suspect.<ref name=scotsman1/> ] suggested this may have been due to his having had bad experiences with women and police officers.<ref>Haining, ''The Legend and Bizarre Crimes of Spring Heeled Jack''.</ref> | |||

| The Marquess was frequently in the news in the late 1830s for drunken brawling, brutal jokes and vandalism, and was said to do anything for a bet; his irregular behaviour and his contempt for women earned him the title "the Mad Marquis", and it is also known that he was in the London area by the time the first incidents took place. In 1880 he was named as the perpetrator by ], who said that the Marquess "used to amuse himself by springing on travellers unawares, to frighten them, and from time to time others have followed his silly example."<ref>Jacqueline Simpson, ''Spring-Heeled Jack''.</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Brewer |first=Ebenezer Cobham|editor=Marion Harland|title=The reader's companion: Character sketches of romance, fiction and the drama|chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/charactersketche07brewuoft#page/82/mode/1up|edition=Revised American |volume=VII: Skeggs-Trovatore|year=1896|publisher=Selmar Hess|location=New York|page=30|chapter=Spring-Heeled Jack}}</ref> In 1842, the Marquess married and settled in Curraghmore House, ], and reportedly led an exemplary life until he died in a riding accident in 1859.{{citation needed|date=June 2017}} | |||

| ] ] investigators have repeatedly deprecated the stories of Spring Heeled Jack. Some of them maintain that it is nothing but an exaggeration of the tale of a certain mentally ill ], who danced and leapt over rooftops claiming that the ] was chasing him <sup id="fn_9_back">]</sup>. Other researchers believe that some individual(s) may have been behind its origins, being followed by imitators later on <sup id="fn_10_back">]</sup>. It is worthy of note that, following his appearance and for the years that followed, the press, the authorities, and most of the general public considered Spring Heeled Jack to be not a ] creature, but rather an individual (or perhaps more than one person) with a macabre sense of humour who delighted in scaring and molesting women. This idea matches the contents of the letter to the Lord Mayor, which accused a group of young aristocrats as the culprits, after an irresponsible wager. A popular rumour that was in circulation as early as 1840 pointed at an Irish nobleman, ], as the main suspect of being behind the events. The responsibility of the Marquess has been accepted by several modern authors, who suggest that a humiliating experience with a woman and a police officer could have given him the idea of creating the character as a way of "getting even" with police and women in general <sup id="fn_11_back">]</sup>. Said authors speculate that he could have designed (with the help of friends who were experts in applied mechanics) some sort of apparatus for special spring-heeled boots, and that he may have practised fire-spitting techniques in order to increase the unnatural appearance of his character. Lastly, they point at the embroidered ] with a "''W''" letter observed by the servant boy at the Ashworth incident, a notorious coincidence with his title's name. | |||

| Sceptical investigators have asserted that the story of Spring-heeled Jack was exaggerated and altered through mass hysteria, a process in which many sociological issues may have contributed. These include unsupported rumours, superstition, ], ] publications, and a folklore rich in tales of ] and strange roguish creatures. Gossip of alleged leaping and fire-spitting powers, his alleged extraordinary features and his reputed skill in evading apprehension captured the mind of the superstitious public—increasingly so with the passing of time, which gave the impression that Spring-heeled Jack had suffered no ill effects from age. As a result, a whole urban legend was built around the character, being reflected by contemporary publications, which in turn fuelled this popular perception.<ref>Massimo Polidoro, "", '']'', July. Accessed on 24 March 2005.</ref> | |||

| Indeed, the Marquess was frequently in the news in the late 1830s for drunken brawling, brutal jokes and vandalism, and was said to do anything for a bet; his irregular behaviour and his contempt for women earned him the moniker ''"the Mad Marquis'''', and it is also known that he was present in the London area by the time the first incidents took place. Unfortunately, The Waterford Chronicle was able to report his presence at the St Valentine's Day Ball at Waterford Castle, which means that he has a cast-iron alibi for the attacks on Jane Allsop and Lucy Scales, which are at the centre of Jack's authenicated history. But he was, nevertheless, pointed as the perpetrator by the Rev. E. C. Brewer in 1880, who attested that the Marquess ''"used to amuse himself by springing on travellers unawares, to frighten them, and from time to time others have followed his silly example"'' <sup id="fn_12_back">]</sup>. In 1842, ] married and settled in Curraghmore House, ], and reportedly led an exemplary life, until he died in a horse riding accident in 1859. Meanwhile, Spring Heeled Jack remained active for decades after, which leads the aforementioned modern researchers to the same conclusion as Brewer's: the Marquess may well have been responsible for the first attacks, while it was up to other pranksters who occasionally imitated him to continue the task. | |||

| Either if the legend is based in the zealot episode, or if a particular person or a group of them was behind its origins being followed by mimics later on, skeptical investigators are unanimous in asserting that the story of Spring Heeled Jack was exaggerated and altered through ], a process in which many ] issues may have contributed. These include unsupported rumours, ], ], ] publications, and a ] rich in tales of ] and strange roguish creatures. Gossip of his leaping and fire-spitting "powers", his alleged extraordinary features and his skill in avoiding all attempts of apprehension captured the mind of the superstitious public, and so his figure was given a supernatural aura. This became especially true with the passing of time, which gave the impression that Spring Heeled Jack had suffered no effects from aging. As a result, a whole ] had been built around the character, being reflected by contemporary publications, which in turn fueled this popular perception in a ] <sup id="fn_13_back">]</sup>. | |||

| ===Paranormal conjectures=== | ===Paranormal conjectures=== | ||

| ]A variety of wildly speculative paranormal explanations have been proposed to explain the origin of Spring-heeled Jack, including that he was an ] entity with a non-human appearance and features (e.g., ] red eyes, or ] breath) and a ] agility deriving from life on a high-gravity world, with his jumping ability and strange behaviour,<ref>'']'s World of Strange Phenomena''.</ref> and that he was a ], accidentally or purposefully summoned into this world by practitioners of the ], or who made himself manifest simply to create spiritual turmoil.<ref>Supporters of this theory include ], author of '']'', and ].</ref> | |||

| ] authors, particularly ]<ref>Mysterious America</ref> and ],<ref>Unexplained!</ref> list "Spring-heeled Jack" in a category named "phantom attackers", with another well-known example being the "]". Typical "phantom attackers" appear to be human, and may be perceived as prosaic criminals, but may display extraordinary abilities (as in Spring-heeled Jack's jumps, which, it is widely noted, would break the ankles of a human who replicated them) and/or cannot be caught by authorities. Victims commonly experience the "attack" in their bedrooms, homes or other seemingly secure enclosures. They may report being pinned or paralysed, or on the other hand describe a "siege" in which they fought off a persistent intruder or intruders. Many reports can readily be explained psychologically, most notably as the ], recorded in folklore and recognised by psychologists as a form of hallucination. In the most problematic cases, an "attack" is witnessed by several people and substantiated by some physical evidence, but the attacker cannot be verified to exist.{{citation needed|date=June 2017}} | |||

| A wide variety of explanations have been proposed by authors who support the ] origin of Spring Heeled Jack. Due to the inherent nature of the phenomenon, such theories are speculative and bereft of any proof. The following are just a few: | |||

| ==Counterpart in Prague== | |||

| * A common hypothesis proposes Spring Heeled Jack as an ] entity, somehow stranded on ]. Supporters of this theory believe this would explain his non-human appearance and features, (e.g., ] red eyes, or ] breath), his jumping ability (by suggesting that he may have been native of a planet with greater gravitational pull, like ]s experienced on the ]), strange behaviour (which could have been altered through ] or as a result of breathing the gases present at the ]), and his longevity.<sup id="fn_14_back">]</sup> | |||

| A similar figure known as ] was reported to have been seen in ] around 1939–1945. As writers such as ] have shown, the elusiveness and supernatural leaping abilities attributed to Pérák bear a close resemblance to those exhibited by Spring-heeled Jack, and distinct parallels can be drawn between the two entities.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> The stories of Pérák provide a useful example of how the traits of Spring-heeled Jack have a broad cultural resonance in urban folklore. Pérák, like Spring-heeled Jack, went on to become a folklore hero, even starring in several animated superhero cartoons, fighting the ], the earliest of which is ]'s 1946 film ''Pérák a SS'' or '']''.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www2.bfi.org.uk/sites/bfi.org.uk/files/downloads/bfi-press-release-jiri-trnka-at-bfi-southbank-in-april-2012-03-06.pdf|title="Jiří Trnka At BFI Southbank in April 2012", (Trnka Shorts for Adults) BFI press release March 2012.}}</ref> | |||

| ==In contemporary popular culture== | |||

| * A visitor from another ], who could have entered into this ] through a ] or dimensional gate.<sup id="fn_15_back">]</sup> | |||

| The character of Spring-heeled Jack has been revived or referenced in a variety of 20th and 21st century media, including: | |||

| ''Spring-Heeled Jack'' (1989) – a combination prose and graphic novel by ] in which Spring-heeled Jack saves a group of plucky orphans from the malevolent Mack the Knife.<ref>{{cite web |title=Spring-Heeled Jack |url=https://www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-440-41881-8 |website=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150706133900/https://www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-440-41881-8 |archive-date=July 6, 2015 |date=March 1, 2004 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| * A ], accidentally or purposefully summoned into this world by practitioners of the ] (a theory that has been incorporated into the ] "Feng Shui") <sup id="fn_16_back">]</sup>, or who made himself manifest simply to create spiritual turmoil.<sup id="fn_17_back">]</sup> | |||

| "Spring Heeled Jack" – a song composed by ], published under the pseudonym ], which was released on his 2008 album '']''. | |||

| The supporters of the paranormal explanations usually refer as proof of their claims that no human could have ever used a ] to leap the way Spring Heeled Jack was said to, by pointing that in the 20th century, the ] experimented on the subject with disastrous effects. Allegedly, such experiments gave an estimated 85% rate of failure, with broken legs and ankles on the testers. They conclude that there was no possibility for an individual to succeed where an official warfare project failed, especially considering that the former had preceded it by many decades.<sup id="fn_18_back">]</sup> It might be worth noting that there currently is a comparable device being marketed <sup id="fn_19_back">]</sup>, but this gadget requires modern, state-of-the-art ] springs. | |||

| '']'' (2010) – an alternate history novel by author Mark Hodder, portraying Spring-Heeled Jack as a time traveler.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack |url=https://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-61614-240-7 |website=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130310072800/https://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-61614-240-7 |archive-date=March 10, 2013 |date=July 19, 2010 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Spring Heeled Jack in popular culture== | |||

| '']'' (2011) – a three-series audio drama produced by the Wireless Theatre Company.<ref>{{cite web |author1=J. R. Southall |title=The Secret of Springheel'd Jack Series 3, Episode Two: The Tunnels if Death |url=http://www.starburstmagazine.com/reviews/audio-reviews/14201-audio-review-the-secret-of-springheeld-jack-series-3-episode-two-the-tunnels-of-death |website=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160125141102/http://www.starburstmagazine.com/reviews/audio-reviews/14201-audio-review-the-secret-of-springheeld-jack-series-3-episode-two-the-tunnels-of-death |archive-date=January 25, 2016 |date=2016 |url-status=unfit}}</ref> | |||

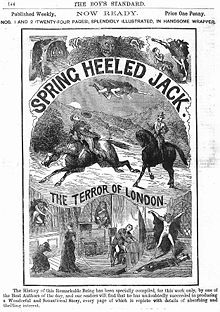

| ] cover page (c. 1904).]]The vast urban legend built around Spring Heeled Jack influenced many aspects of ] life, especially in contemporary ]. The '']'' recounts that, in late Victorian times, his name had become a general term for a street criminal who leapt upon people to rob or frighten them, and then relied on his speed in running to make his escape. It cites a ] source from 1887 as an example, where maids who had just been paid their yearly wage were said to be afraid to go out carrying much money, since ''"there are so many of these spring-heeled Jacks about"'' <sup id="fn_20_back">]</sup> . For decades, especially in London, his name was equated with ], as a means of scaring children into behaving by telling them that if they were not good, Spring Heeled Jack would leap up and peer in at them through their bedroom windows, by night. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| However, it was in the field of fictional entertainment where the legend of Spring Heeled Jack exerted the most extensive influence, due to his allegedly extraordinary nature. Almost from the moment the first incidents gained public knowledge, he turned into a successful ], becoming the protagonist of many ]s from 1840 to 1904. Several plays where he assumed the main role were staged as well. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| The most notable fictional Spring Heeled Jacks of the 19th and early 20th centuries were: | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| *A play by John Thomas Haines, in 1840, ''Spring-Heeled Jack, the Terror of London'', which shows him as a ] who attacks women because his own sweetheart betrayed him. | |||

| *Later that decade, Spring Heeled Jack's first penny dreadful appearance came in the anonymously written ''Spring-Heeled Jack, The Terror of London'', which appeared in weekly episodes. | |||

| *W. G. Willis' 1849 play, ''The Curse of the Wraydons'', where Spring Heeled Jack is a traitor who spies for ], and stages murderous stunts as a cover. | |||

| *A 1863 play, ''Spring-Heel'd Jack: or, The Felon's Wrongs'', written by Frederick Hazleton. | |||

| *''Spring-heel'd Jack: The Terror of London'', a ] published by the Newsagents’ Publishing Company c. 1864-1867. | |||

| *''Spring-heel'd Jack: The Terror of London'', a 48-part penny weekly serial published c. 1878-1879 in ''The Boys' Standard'', written either by veteran dreadful author George Sala or by Alfred Burrage in his pseudonym of ''Charlton Lea''. | |||

| *''Spring-Heel Jack; or, The Masked Mystery of the Tower'', appearing in ''Beadle's New York Dime Library #332'', ] ], and written by Col. Thomas Monstery. | |||

| *a 1889-1890 48-part serial published by Charles Fox and written by Alfred Burrage in his pseudonym of ''Charlton Lea''. | |||

| *a 1904 version by Alfred Burrage. <sup id="fn_21_back">]</sup> | |||

| *a remake of ''The Curse of the Wraydons'', written in 1928 by ] Swiss author Maurice Sandoz, which served as base for a movie that bears the same name in ]. <sup id="fn_22_back">]</sup> | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| The early works invariably presented Spring Heeled Jack as an arch-villain, but remarkably, his figure experienced a metamorphosis throughout the years, and his role was completely swapped to a ]. The first ] to introduce such a change was the 1860s edition, and this variation was adopted by all the publications that followed, reaching its highest development in Burrage's 1904 version.] In these stories (which take place in 1805, after ] has conquered ]), Spring Heeled Jack is Bertram Wraydon, a young and handsome ] of the ], heir to £10,000 a year, who is unfairly framed for treason by his evil half brother Hubert Sedgefield. After escaping from his prison, Wraydon returns seeking revenge on the villains, assuming a ] and an odd-looking costume with mane and talons, fighting against evil and helping the innocent. He has a secret lair, where he has hidden what he managed to save of his inheritance, selflessly using it to fund his heroic activities. These include the design of a spring mechanism that allows him to leap over thirty feet, and a device to breathe flames at evildoers. He even has a trademark which he leaves at the scene of his actions; a letter "''S''" that he carves with his ] after his mission is accomplished. | |||

| * Bell, Karl. ''The Legend of Spring-Heeled Jack: Victorian Urban Folklore and Popular Cultures'', Boydell & Brewer, Boydell Press, 2012. {{ISBN|978-1-84383-787-9}} | |||

| * ]. ''Charles Berlitz's World of Strange Phenomena''. New York: Fawcett Crest, 1989. {{ISBN|0-449-21825-2}}. | |||

| * ]. ''Unexplained!: Strange Sightings, Incredible Occurrences and Puzzling Physical Phenomena''. Detroit: Visible Ink, 1993. {{ISBN|1-57859-070-1}}. | |||

| * Clarke, David. ''Strange South Yorkshire: Myth, Magic and Memory in the Don Valley''. Wilmslow: Sigma Press, 1994. {{ISBN|1-85058-404-4}}. | |||

| * Cohen, Daniel. '']''. Dodd Mead, 1982. {{ISBN|0-396-09051-6}}. | |||

| * ]. ''Spring-heeled Jack: To Victorian Bugaboo from Suburban Ghost'', in ''], vol. 3'', ] , (1996), pp. 7–125. {{ISBN|978-1870870825}}. | |||

| * {{Skeptoid | id=4064 | number=64 | title=The Attack of Spring Heeled Jack<!-- : A look at the theories surrounding Spring Heeled Jack, the scourge of England in the early 1800s --> | date=September 4, 2007| access-date=May 29, 2022}} | |||

| * ]. '']''. London: Muller, 1977. {{ISBN|0-584-10276-3}}. | |||

| * ]. ''The Mystery of Spring-Heeled Jack: From Victorian Legend to Steampunk Hero''. ], 2016. {{ISBN|978-1620554968}}. | |||

| * ]. ''The Encyclopaedia of Fantastic Victoriana''. Austin: MonkeyBrain, 2005. {{ISBN|1-932265-08-2}}. | |||

| * Paton, James. ''The Black Book of Ghosts, Ufo's and the Unexplained''. Amazon Kindle 2013. {{ASIN|B00EK40WGE}}. | |||

| * ]. ''Strange and Unexplained Mysteries of the 20th Century''. New York: Sterling, 1994. {{ISBN|0-8069-0768-1}}. | |||

| * Robins, Joyce. ''The World's Greatest Mysteries''. London: Treasure, 1991. {{ISBN|1-85051-698-7}}. | |||

| * ]. ''Spring-Heeled Jack'' (leaflet, January 2001). International Society for Contemporary Legend Research. | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| Although lacking durable literary value, the Spring Heeled Jack series exerted an important influence as a predecessor of modern day ] and ] superheroes, taking into consideration that they were written twenty years before the first ] adventure and more than half a century before other fictional characters like ] or the ] were created. Such lasting influence and its consequent cultural importance were, for most part of the 20th century, practically forgotten. | |||

| * {{commons-inline|Spring Heeled Jack}} | |||

| * {{wikiquote-inline}} | |||

| * by ] | |||

| * "". Local Legends. ]. | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121017153212/http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0602571.txt |date=17 October 2012 }}. Anonymous. Unknown novel at Project Gutenberg Australia. | |||

| * —Fortean Page on SHJ | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| However, a renewed interest in the legend of Spring Heeled Jack has sparked in the last years. Several English comic characters were based directly on him since the early 1970s, like ''Jumping Jack, the Leaping Phantom'', ''Spring-Heeled Jock'' and ''Spring-Heeled Jackson'' <sup id="fn_23_back">]</sup>. | |||

| Recently, several comic authors like Ver Curtiss <sup id="fn_24_back">]</sup>, Kevin Olson and David Hitchcock <sup id="fn_25_back">]</sup>, have made Spring Heeled Jack the protagonist of different comic adventures. These series, which are set in a shady and ] environment, once again give him the role of a superhero. | |||

| Even to the present day, the tale continues to attract the imagination of writers, like ] (author of the best-selling trilogy '']''), who published his novel ''Spring Heeled Jack – A Story of Bravery and Evil'' in 1989 (ISBN 0440862299). Best-selling author ] also wrote about a modern-day Spring Heeled Jack in his short story ''].'' | |||

| The story has also provided inspiration for music artists. Singer ]'s song titled ''"Spring-Heeled Jim"'' was released on his ] album '']'' and reappeared the next year on the '']'' album.<sup id="fn_26_back">]</sup>. Other musicians have named their bands after the legendary character, including the English duo ] and the American ] group ]. | |||

| Perhaps the most recent example is in a quest in the 2006 video game ], wherein the main character is sent to collect the "Boots of Springheel Jak," which greatly increase the character's jumping ability and speed. | |||

| == See also == | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *], especially: | |||

| **] | |||

| **] | |||

| **] | |||

| **] | |||

| **] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Resources== | |||

| ===Footnotes=== | |||

| <div class="references-small"> | |||

| * <cite id="fn_1">] </cite> A few sources go beyond that date, citing alleged apparitions of Spring Heeled Jack in 1808 in ]. ''"''''." The Legend of Spring Heeled Jack by Sharon McGovern''. Accessed on ], ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_2">] </cite> Peter Haining, ''The Legend and Bizarre Crimes of Spring Heeled Jack'' (1977), claims that this group was composed of three women and a man, while ''Joyce Robbins, The World's Greatest Mysteries'' (1991) argues that only three women were present. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_3">] </cite> Jerome Clark, ''Unexplained!: Strange Sightings, Incredible Occurrences & Puzzling Physical Phenomena'' (1993), mentions that the press referred variously as "'''Spring-Heeled Jack'''", "'''Springheel Jack'''" or "'''Springald'''". This later name probably derives from a ] term for an ''"active or springy young man"''. Peter Haining, op. cit., asserts that the term ''"springald"'' was rather the origin of the name Spring Heeled Jack, to which it evolved later; alas, there is no proof to support this claim, according to Clark. Dash, op. cit., reveals that there is no contemporary evidence that this term was used in the 1830's, and establishes that the first original name was "'''Steel Jack'''", a possible reference to his supposed appearances clad in armour. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_4">] </cite> As quoted by Jacqueline Simpson, ''Spring-Heeled Jack'' (2001). | |||

| * <cite id="fn_5">] </cite> Peter Haining, op. cit., based on reports from ] of 10th and 12th January 1838. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_6">] </cite> This name differs according to the source. ''"Scales"'' is the name used by Peter Haining, op. cit., and the usually accepted version, while ] in ''Charles Berlitz 's World of Strange Phenomena'' (1989), provides the variation ''"Sales"'' and Daniel Cohen, ''The Encyclopedia of Monsters'' (1982) mentions it as ''"Squires"'' (''See <cite id="fn_8">]). | |||

| * <cite id="fn_7">] </cite> Peter Haining, op. cit., based on reports from ] of ] ] and ] ]. Most sources agree on these dates with the exception of Charles Berlitz, op. cit., who assigns them two days later each. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_8">] </cite> Daniel Cohen, op. cit., based on Limehouse police's records, where the name is registered as ''"Squires"''. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_9">] </cite> Jenny Randles, ''Strange & Unexplained Mysteries of the 20th Century'' (1994). | |||

| * <cite id="fn_10">] </cite> Mike Dash, ''Spring Heeled Jack'', from ''Fortean Studies'' (1995), compiled by Steve Moore. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_11">] </cite> Peter Haining, op. cit. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_12">] </cite> Jacqueline Simpson, op. cit. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_13">] </cite> ''"''''."'' ''Monkey Man, Spring Heeled Jack; Notes on a Strange World.'' Accessed on ] ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_14">] </cite> Charles Berlitz, op. cit. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_15">] </cite> ''"''."'' ''The Beast of Gevaudan, Spring-Heeled Jack, Mothman and other window fallers''. Accessed on ] ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_16">] </cite> ''"''."'' ''Spring-Heeled Jack''. Accessed on ] ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_17">] </cite> Supporters of this theory include ] (author of the best-seller book '']'') and ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_18">] </cite> ''"''."'' ''Spring Heeled Jack: profitable, unbelievable.'' Accessed on ] ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_19">] </cite> ''"''."'' ''Seven Miles boots'' (commercial website). Accessed on ] ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_20">] </cite> Jacqueline Simpson, op. cit. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_21">] </cite> Jess Nevins, ''The Encyclopaedia of Fantastic Victoriana'' (2005), and Jacqueline Simpson, ibid. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_22">] </cite> ''"''."'' ''Internet Movie Database entry for "The Curse of the Wraydons".'' Accessed on ], ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_23">] </cite> ''"''."'' ''UK Superheroes.'' Accessed on ] ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_24">] </cite> ''"''."'' ''The Art of Ver Curtiss''. Accessed on ] ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_25">] </cite> ''"''."'' ''The Works of David Hitchcock''. Accessed on ] ]. | |||

| * <cite id="fn_26">] </cite> ''"''."'' ]. Accessed on ] ]. | |||

| </div> | |||

| ===References=== | |||

| <div class="references-small"> | |||

| *Mike Dash. 'Spring-Heeled jack', ''Fortean Studies''3 (1996), 7-125. | |||

| *Jacqueline Simpson. ''Spring-Heeled Jack'' (leaflet, January 2001). International Society for Contemporary Legend Research <!-- a short article that provides much hard-to-find information on the coverage dedicated by the Victorian press to the incidents. --> | |||

| *{{cite book | author=] | title=Strange & Unexplained Mysteries of the 20th Century | publisher=Sterling Publishing Co. Inc | year=1994 | id=ISBN 0806907681}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=] | title=Unexplained!: Strange Sightings, Incredible Occurrences & Puzzling Physical Phenomena | publisher=Visible Ink Press | year=1993 | id=ISBN 1578590701}} <!-- entertaining book that covers many strange phenomena in a shallow fashion, without consistent proofs. --> | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Daniel Cohen | title=The Encyclopedia of Monsters | publisher=Dodd Mead | year=1982 | id=ISBN 0396090516}} <!-- is an above-average ] book, highly recommended to get started in the field. --> | |||

| *{{cite book | author=] | title=The Encyclopaedia of Fantastic Victoriana | publisher=MonkeyBrain Inc | year=2005 | id=ISBN 1932265082}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=] | title=The Legend and Bizarre Crimes of Spring Heeled Jack | publisher=Muller | year=1977 | id=ISBN 0584102763}} <!-- a rather colourful book that provides many of the more sensational details and the most fantastic theories, but lacking of a serious investigation of the events. --> | |||

| *{{cite book | author=] | title=Charles Berlitz 's World of Strange Phenomena | publisher=Fawcett | year=1989 | id=ISBN 0449218252}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Steve Moore | title=Fortean Studies | publisher=John Brown Publishing | year=1995 | id=ISBN 1870870557}} <!-- includes a very long article by Mike Dash dedicated to Spring Heeled Jack that is by far the best source currently available on the subject. --> | |||

| *{{cite book | author=] | title=Borderlands: The Ultimate Exploration of the Unknown | publisher=Dell | year=2000 | id=ISBN 0440236568}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Joyce Robbins | title=Borderlands: The World's Greatest Mysteries| publisher=Bounty Books | year=1991 | id=ISBN 1850516987}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=David Clarke | title=Strange South Yorkshire: Myth, Magic and Memory in the Don Valley | publisher=Sigma Press | year=1994 | id=ISBN 1850584044}} | |||

| </div> | |||

| *''Fortean Studies'' 3 (1996), by Mike Dash, pp. 7-125. | |||

| ===External links=== | |||

| <div class="references-small"> | |||

| *—Long paper on Spring-heeled Jack based on extensive research in contemporary newspapers. | |||

| *—Includes an example of a Spring Heeled Jack-based penny dreadful. | |||

| *—Spring Heeled Jack | |||

| *—Spring Heeled Jack reappears in 1970s ]? | |||

| *— Spring Heeled Jack | |||

| *— The Top Ten Most Mysterious Creatures of Modern Times | |||

| *— What makes Britain so... British! Spring Heeled Jack | |||

| *— Spring Heeled Jack | |||

| *— The Legend of Spring Heeled Jack by Sharon McGovern | |||

| *— The Spring Heeled Jack Website | |||

| </div> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:31, 13 October 2024

English legendary folklore character For other uses, see Spring-heeled Jack (disambiguation).

| |

| Grouping | Hoax, mass hysteria, demon, phantom |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Region | London Liverpool |

Spring-heeled Jack is an entity in English folklore of the Victorian era. The first claimed sighting of Spring-heeled Jack was in 1837. Later sightings were reported all over the United Kingdom and were especially prevalent in suburban London, the Midlands and Scotland.

There are many theories about the nature and identity of Spring-heeled Jack. This urban legend was very popular in its time, due to the tales of his bizarre appearance and ability to make extraordinary leaps, to the point that he became the topic of several works of fiction.

Spring-heeled Jack was described by people who claimed to have seen him as having a terrifying and frightful appearance, with diabolical physiognomy, clawed hands, and eyes that "resembled red balls of fire". One report claimed that, beneath a black cloak, he wore a helmet and a tight-fitting white garment like an oilskin. Many stories also mention a "Devil-like" aspect. Others said he was tall and thin, with the appearance of a gentleman. Several reports mention that he could breathe out blue and white flames and that he wore sharp metallic claws at his fingertips. At least two people claimed that he was able to speak comprehensible English.

History

Precedents

In the early 19th century, there were reports of ghosts that stalked the streets of London. These human-like figures were described as pale; it was believed that they stalked and preyed on lone pedestrians. The stories told of these figures formed part of a distinct ghost tradition in London which, some writers have argued, formed the foundation of the later legend of Spring-heeled Jack.

The most important of these early entities was the Hammersmith Ghost, which in 1803 and 1804 was reported in Hammersmith on the western fringes of London; it would later reappear in 1824. Another apparition, the Southampton ghost, was also reported as assaulting individuals in the night. This particular spirit bore many of the characteristics of Spring-heeled Jack, and was reported as jumping over houses and being over 10 ft (3.0 m) tall.

Early reports

The first alleged sightings of Spring-heeled Jack were made in London in 1837 and the last reported sighting is said in most of the secondary literature to have been made in Liverpool in 1904.

According to much later accounts, in October 1837 a girl by the name of Mary Stevens was walking to Lavender Hill, where she was working as a servant, after visiting her parents in Battersea. On her way through Clapham Common, a strange figure leapt at her from a dark alley. After immobilising her with a tight grip of his arms, he began to kiss her face, while ripping her clothes and touching her flesh with his claws, which were, according to her deposition, "cold and clammy as those of a corpse". In panic, the girl screamed, making the attacker quickly flee from the scene. The commotion brought several residents who immediately launched a search for the aggressor, but he could not be found.

The next day, the leaping character is said to have chosen a very different victim near Mary Stevens' home, inaugurating a method that would reappear in later reports: he jumped in the way of a passing carriage, causing the coachman to lose control, crash, and severely injure himself. Several witnesses claimed that he escaped by jumping over a 9 ft (2.7 m) high wall while cackling with a high-pitched, ringing laughter.

Gradually, the news of the strange character spread, and soon the press and the public gave him the name "Spring-heeled Jack".

Official recognition

A few months after these first sightings, on 9 January 1838, the Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Cowan, revealed at a public session held in the Mansion House an anonymous complaint that he had received several days earlier, which he had withheld in the hope of obtaining further information. The correspondent, who signed the letter "a resident of Peckham", wrote:

It appears that some individuals (of, as the writer believes, the highest ranks of life) have laid a wager with a mischievous and foolhardy companion, that he durst not take upon himself the task of visiting many of the villages near London in three different disguises—a ghost, a bear, and a devil; and moreover, that he will not enter a gentleman's gardens for the purpose of alarming the inmates of the house. The wager has, however, been accepted, and the unmanly villain has succeeded in depriving seven ladies of their senses, two of whom are not likely to recover, but to become burdens to their families.

At one house the man rang the bell, and on the servant coming to open door, this worse than brute stood in no less dreadful figure than a spectre clad most perfectly. The consequence was that the poor girl immediately swooned, and has never from that moment been in her senses.

The affair has now been going on for some time, and, strange to say, the papers are still silent on the subject. The writer has reason to believe that they have the whole history at their finger-ends but, through interested motives, are induced to remain silent.

Though the Lord Mayor seemed fairly sceptical, a member of the audience confirmed that "servant girls about Kensington, Hammersmith and Ealing, tell dreadful stories of this ghost or devil". The matter was reported in The Times on 9 January, other national papers on 10 January and, on the day after that, the Lord Mayor showed a crowded gathering a pile of letters from various places in and around London complaining of similar "wicked pranks". The quantity of letters that poured into the Mansion House suggests that the stories were widespread in suburban London. One writer said several young women in Hammersmith had been frightened into "dangerous fits" and some "severely wounded by a sort of claws the miscreant wore on his hands". Another correspondent claimed that in Stockwell, Brixton, Camberwell and Vauxhall several people had died of fright and others had had fits; meanwhile, another reported that the trickster had been repeatedly seen in Lewisham and Blackheath.