| Revision as of 17:27, 26 September 2013 editMuboshgu (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators376,397 edits →External links← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:59, 30 December 2024 edit undoJevansen (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers3,375,576 edits Copying from Category:19th-century baseball players to Category:19th-century American sportsmen using Cat-a-lot | ||

| (141 intermediate revisions by 53 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American baseball player (1841–1862)}} | |||

| :''For the basketball player, see ]''. | |||

| {{For|another person|Jim Creighton (basketball)}} | |||

| {{Infobox MLB player | |||

| {{Infobox baseball biography | |||

| |name=Jim Creighton | |name=Jim Creighton | ||

| |position=] | |position=] | ||

| Line 7: | Line 8: | ||

| |throws=Right | |throws=Right | ||

| |birth_date={{Birth date|1841|4|15}} | |birth_date={{Birth date|1841|4|15}} | ||

| |birth_place=], |

|birth_place=], New York, US | ||

| |death_date={{death date and age|1862|10|18|1841|4|15}} | |death_date={{death date and age|1862|10|18|1841|4|15}} | ||

| |death_place=], New York | |death_place=], New York, US | ||

| |teams= |

|teams= | ||

| ; National Association of Base Ball Players | ; National Association of Base Ball Players | ||

| * ] 1860–1862 | * ] 1860–1862 | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''James Creighton, Jr.''' (April 15, 1841 – October 18, 1862) was an |

'''James Creighton, Jr.''' (April 15, 1841 – October 18, 1862) was an American ] player during the game's ] era, and is considered by ]s to be the sport's first ] and one of its earliest paid competitors. In 1860 and 1862 he played for one of the most dominant teams of the era, the ]. He also was reputed to be a superb cricketer, and played in many amateur and professional ] matches. | ||

| During this early, pre-professional period of baseball's evolution, Creighton's pitching technique changed the sport from a game that showcased ], running, and ] into a confrontation between the ] and ]. Under rules of the day, a pitcher was required to deliver the ball in an underhand motion with a stiff arm/stiff wrist movement. The intention was to induce the batter to swing and put the ball in play, thus initiating action on the diamond. Creighton's swift delivery was difficult for opposing batters to hit, because they were accustomed to balls being lobbed over the plate. | |||

| The speed with which Creighton was able to hurl the ball had previously been considered impossible without movement of the elbow or wrist, which was prohibited by existing rules. If there were any such movements by Creighton, they were imperceptible. Nonetheless, he was accused by some opponents and spectators of using an illegal ]. In effect, because Creighton was exceptionally successful, his opponents assumed he was cheating. | |||

| In October 1862, at the height of his popularity, he injured himself in a game when he suffered a ruptured abdominal hernia hitting a ]. The rupture caused internal bleeding, and he died four days later. Diagnosis' differ as to cause of death; ranging from a strain to a ruptured bladder, but modern medical understanding of the symptoms suggest that it was most likely a ruptured inguinal hernia. His death created an emotional connection to the sport, propelling its popularity much closer to cricket. | |||

| However, the competitive advantage of this delivery, and his success as a pitcher, eventually led others to emulate his technique. Historian Thomas Gilbert, in his 2015 book ''Playing First: Early Baseball Lives at Brooklyn's ]'', which includes a chapter on Creighton and his extended family, referred to Creighton's pitching style as "weaponizing the ball."<ref>, published by The Green-Wood Cemetery, September 2015</ref> | |||

| In October 1862, at the height of his popularity, Creighton suffered a ruptured ], a condition possibly caused and exacerbated by his unorthodox pitching motion and high per-game ]. The rupture caused internal bleeding, and Creighton died four days later. | |||

| ==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| Creighton was born on April 15, 1841 in ] to James and Jane Creighton, and was raised in ].<ref name="thorn122">Thorn, p. 122</ref> By age 16, he had become recognized in the Brooklyn area for his batting skills in both baseball and cricket. In 1857, along with other neighborhood youths, he formed a local baseball club named Young America.<ref name=sabrbio>{{cite web|last=Thorn|first= |

Creighton was born on April 15, 1841 in ] to James and Jane Creighton, and was raised in ].<ref name="thorn122">Thorn, p. 122</ref> By age 16, he had become recognized in the Brooklyn area for his batting skills in both baseball and cricket. In 1857, along with other neighborhood youths, he formed a local baseball club named Young America.<ref name=sabrbio>{{cite web|last=Thorn|first=John|title=Jim Creighton|url=https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/2d2e5d16}}</ref> During this period, there were no organized leagues and few competing teams, so amateur clubs spent much of their time practicing and playing intra-squad games, with occasional matches against rivals. Young America played a few match games before disbanding. Creighton then became a member of Niagara of Brooklyn, playing ].<ref name=sabrbio/> | ||

| ==Baseball== | ==Baseball== | ||

| ⚫ | ===Discovery by the |

||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | In a match on July 19, 1859, the Niagaras were being heavily outscored by the Star Club of Brooklyn. Creighton, who had thus far been used by the team primarily in the infield, was brought on as a ].<ref name="thorn122"/> Using what observers described as a "low, swift delivery," Creighton achieved uncommonly swift velocity. With the balls "rising from the ground past the shoulder to the catcher," the Star batsmen were unable to hit them effectively.<ref name="thorn123"/> Under the rules of baseball at the time, a pitcher was required to deliver the ball underhanded with arm locked straight at the elbow and at the wrist.<ref name="robbins241">Robbins, p. 241</ref> Another technique he used was to give the baseball spinning motion, making it harder for the batters to hit it squarely.<ref name="ryczek4"/> Additionally, he threw a high-arcing slower pitch called a "dew-drop."<ref name="robbins241"/> It was the job of the pitcher to make it easy for the batter to hit the ball as fielding was considered the game's true skill.<ref name="ryczek4">Ryczek, p. 4</ref> Star batsmen claimed that Creighton was using an illegal snap of the wrist to deliver the pitch. |

||

| ⚫ | ===Discovery by the Star Club=== | ||

| ⚫ | ===Excelsiors=== | ||

| ⚫ | In a match on July 19, 1859, the Niagaras were being heavily outscored by the Star Club of Brooklyn. Creighton, who had thus far been used by the team primarily in the infield, was brought on as a ].<ref name="thorn122"/> Using what observers described as a "low, swift delivery," Creighton achieved uncommonly swift velocity. With the balls "rising from the ground past the shoulder to the catcher," the Star batsmen were unable to hit them effectively.<ref name="thorn123"/> Under the rules of baseball at the time, a pitcher was required to deliver the ball underhanded with arm locked straight at the elbow and at the wrist.<ref name="robbins241">Robbins, p. 241</ref> Another technique he used was to give the baseball spinning motion, making it harder for the batters to hit it squarely.<ref name="ryczek4"/> Additionally, he threw a high-arcing slower pitch called a "dew-drop."<ref name="robbins241"/> It was the job of the pitcher to make it easy for the batter to hit the ball as fielding was considered the game's true skill.<ref name="ryczek4">Ryczek, p. 4</ref> Star batsmen claimed that Creighton was using an illegal snap of the wrist to deliver the pitch. The Star Club eventually won the game, but following the match, Creighton left the Niagaras and joined the Stars.<ref name=sabrbio/> | ||

| ⚫ | Before the 1860 season began, Creighton left the Star Club and joined one of the highest-profiled clubs in the game at the time, the ].<ref name=sabrbio/> With their new star pitcher, the Excelsiors became a national sensation. They organized the first known |

||

| ⚫ | ===Joins the Excelsiors=== | ||

| ⚫ | When observing Creighton |

||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | Before the 1860 season began, Creighton left the Star Club and joined one of the highest-profiled clubs in the game at the time, the ].<ref name=sabrbio/><ref> ''Threads of Our Game'', May 25, 2014</ref> With their new star pitcher, the Excelsiors became a national sensation. They organized the first known baseball tour outside of their home region, taking on teams along the ].<ref name=sabrbio/> That first season, Creighton scored 47 ] in 20 match games, and was ] just 56 times and did not ]. In a game against the St. George Cricket Club on November 8, he recorded baseball's first ].<ref name=eagle01>{{cite news|title=Excelsior vs. St. George |url=http://baseballhistoryblog.com/tag/jim-creighton/ |newspaper=] |date=November 10, 1860 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120426011606/http://baseballhistoryblog.com/tag/jim-creighton/ |archivedate=April 26, 2012 }}</ref> In addition to his pitching skills, he became the game's best batter. In 1862, he batted 1.000, getting hits in all 65 of his at-bats. (The Excelsiors did not play in 1861, as many players had left to fight in the ].) | ||

| ===Pitching style=== | |||

| ==Professionalism== | |||

| ⚫ | When observing Creighton bowling in a cricket match, English ] ] commented, "Why, that man is not bowling, he is throwing underhand. It is the best disguised underhand throwing I ever saw, and might readily be taken for a fair delivery."<ref name="thorn122"/> Another observer said that his pitch was "as swift as it was shot out of cannon."<ref name="robbins241"/> Excelsior teammate ] later in his life wrote that Creighton "...had wonderful speed, and, with it, splendid command. He was fairly unhittable." Others, especially more tradition-minded members in the baseball community, complained that not only were his pitches illegal, but also unsportsmanlike.<ref name="robbins242">Robbins, p. 242</ref> After Creighton held the famed rival ] to five runs, an extraordinarily low total for the era, the '']'' dispatched a reporter to determine whether or not his pitch was legal. The journalistic witness reported that Creighton was throwing a "fair square pitch", rather than a "jerk" or an "underhand throw." | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| === |

===Professionalism=== | ||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | Creighton was considered a prominent member of the ] community, playing both amateur and professional. He performed for the ] in both 1861 and 1862, often playing against the all-England team, whether at |

||

| During this era of baseball, the game was an amateur sport, and clubs served as social organizations with sporting activities rather than as strictly sports alliances. Creighton was described as principled, unassuming, and gentlemanly — traits considered ideal during the amateur era.<ref name="thorn123">Thorn, p. 123</ref> However, rumors circulated that clubs had started paying exceptional players in an ] manner. Clubs would hire the player ostensibly for a position of responsibility within their administration, or the player would be given a ] in a municipal department, with the understanding that there were no actual duties required beyond playing for the sports team. | |||

| ⚫ | In 1860, the Excelsior Club lured Creighton, along with teammates ] and the brothers ] and ]. All but Henry Brainard were quietly paid a salary, with Creighton earning $500, thus making these men some of the earliest "professional" baseball players.<ref name="thorn123"/><ref name="thorn120">Thorn, p. 120</ref> After winning the ] championship in 1860, Creighton and Asa Brainard jumped from the Excelsior Club to the ]. This move lasted only three weeks, and without having played any games, both players returned to the Excelsiors.<ref name=sabrbio/> While the practice of pay-for-play unofficially spread throughout baseball in the coming years, open professionalism didn't begin until the ], when the ] paid a salary to each member of the team.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/last-hurrah-for-the-cincinnati-red-stockings-8f45a7cae59a |title=Last Hurrah for the Cincinnati Red Stockings |last=Thorn |first=John |date=2018-01-08 |website=Our Game |access-date=2018-06-11}}</ref> | ||

| ==Cricket== | |||

| ⚫ | Creighton was considered a prominent member of the ] community, playing both amateur and professional. He performed for the ] in both 1861 and 1862, often playing against the all-England team, whether at Hoboken's ] or elsewhere.<ref name=sabrbio/> Though the English teams would dominate these matches, Creighton fared well. In an 1859 match of 11 Englishmen against 16 Americans, he clean ] five ]s out of six successive balls.<ref name="thorn122"/> | ||

| ==Death== | ==Death== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| On October 14, 1862, in a match against the ], Creighton had hit four ] in four ]s during the first five innings |

There has been some historical controversy about the circumstances of Creighton's death. On October 14, 1862, Creighton played second base in a match on the Excelsior Grounds against the ] club, while Brainard pitched. Creighton had allegedly hit four ] in four ]s during the first five innings. As chronicled 50 years later by a witness to the game, ], Creighton took over pitching duties from Brainard in the sixth inning, and in his next at bat hit a ]. While swinging the bat, he allegedly suffered an injury in his abdominal area.{{#tag:ref|Players of the era held the bat with their hands separated and swung by twisting their upper-body with little or no movement of the wrists.<ref name=sabrbio/>|group=notes}} According to Chapman, when Creighton crossed ], he commented to the next batter, George Flanley, that he heard something snap.<ref name="spink128">Spink, p. 128</ref> After the game, he began to experience severe pain and hemorrhaging in his abdomen. He died in his father's home on October 18 at the age of 21.<ref name="terry140">Terry, p. 140</ref> In an 1887 issue of an early sports ], the '']'', a letter-writer, who signed only as "Old Timer", sent in his account of the event.<ref>Robert Smith (''Baseball in America'', Holt Rinehart Winston, 1961, p. 10,13)</ref> This account reported it as a ]; in the light of modern medical understanding, the injury was most likely a ruptured ]. | ||

| ]However, subsequent research indicates that Creighton's death by hitting a home run was fabricated years later to dramatize his martyrdom. “Dying while hitting a long home run is a great story; it’s just not true,” said Tom Shieber, senior curator of the ].<ref>Coffey, Wayne, “Daily News Sports Hall of Fame Candidates,” ''New York Daily News'', June 18, 2006.</ref> Shieber researched original news sources and found no references to Creighton hitting a home run in that game. The death-by-home-run myth was popularized, and probably started, five decades later by Chapman. ]’s 1910 book ''The National Game'' quoted Chapman as saying, “I was present at the game between the Excelsiors and the Unions of Morrisiana at which Jim Creighton injured himself. He did it in hitting out a home run. When he had crossed the rubber he turned to George Flanley and said, ‘I must have snapped my belt.’”<ref>Spink, Alfred H., ''The National Game'' (St. Louis: The National Game Publishing Co., 1910), 128.</ref> Countless historians have refuted this legend, but it has taken root as factual. | |||

| ⚫ | Creighton's death caused concern in the sports |

||

| Later research has suggested that Creighton's hernia was chronic, and that the tremendous workload from baseball and cricket contributed to worsening the hernia. In that era, balls and strikes were not called, and batters who couldn't hit Creighton's rapid deliveries adapted by refusing to swing at good pitches, forcing Creighton to throw well over 300 pitches per match. Pitching with great force and the exaggerated body contortions necessary to achieve high velocity exacerbated his condition.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/18/in-brooklyn-honoring-a-baseball-pioneer/ |title=Recalling a New Pitch and a Strange Death |last=Schweber |first=Nate |date=2012-10-18 |work=New York Times |access-date=2018-06-11 |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | At the time, the sport of |

||

| ⚫ | Creighton's death caused concern in the sports world that public perceptions of baseball and cricket would focus on the inherent dangers of their play, hurting the sports' popularity. Though it is generally accepted that Creighton fatally injured himself while playing baseball, it was reported that the Excelsior president, Dr. Joseph Jones, made comments during the National Association convention of 1862 that constituted an attempt to "correct" this notion. He claimed that Creighton had suffered the injury, instead, while playing cricket in a match on October 7.<ref name="thorn126">Thorn, p. 126</ref> Later research claims that Dr. Jones' assertions are correct; Creighton had died of a "strangulated intestine", and did not hit a home run during his final game.<ref name="ryczek14">Ryczek, p. 14</ref> Dr. Jones' remarks have been interpreted as his attempt to save baseball's image, and its nearly equal standing with cricket, as well as his team's legacy after losing their best player.<ref name=sabrbio/> Baseball at the time was constantly "looking forward", and Creighton's death provided the sport with a certain mythology and much-needed nostalgia.<ref name="thorn126"/> | ||

| ⚫ | Baseball writer ] commented in his book, ''Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game,'' that Creighton "was baseball's first hero, and I believe, the most important player not inducted into the ].<ref name="thorn122"/> | ||

| Creighton was buried in Brooklyn's ]. His gravesite was marked by a 12-foot marble obelisk crowned with a large marble baseball. | |||

| ⚫ | ==Legacy== | ||

| ⚫ | , John Thorn, ''Our Game''</ref>]]Baseball writer ] commented in his book, ''Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game,'' that Creighton "was baseball's first hero, and I believe, the most important player not inducted into the ]."<ref name="thorn122"/> | ||

| ⚫ | At the time, the sport of cricket was the most popular team sport in the United States, but Creighton and the Excelsiors had brought considerable attention to baseball. Creighton's popularity grew substantially after his death.<ref name="ryczek14"/> In the following decade, teams began honoring him by naming themselves after him, and others paid tribute by visiting his gravesite.<ref name="thorn126"/> As long as twenty years later, though the public adored their star pitchers, comparisons to Creighton would inevitably emerge. It was not considered controversial to compliment a pitcher with the caveat that he "warn't no Creighton."<ref name="thorn127">Thorn, p. 127</ref> For years following his death, the Excelsiors' ] included a portrait of their team with Creighton, shrouded in black, featured prominently in the center.<ref name="thorn127"/> | ||

| Creighton's indirect legacy is perhaps most profoundly seen in what is now considered a fundamental component of the game: the called ball and the walk. Neither existed during Creighton's lifetime, but his many imitators, who pitched with Creighton's velocity but not his control, prompted batters to stand at the plate without swinging for lengthy intervals, waiting for a pitch within reach. Consequently, the sport's then-governing body, the ], introduced a rule for the 1864 season which penalized pitchers who repeatedly failed to deliver "good balls:" the called ball, three of which gave the batter a free pass to first base. | |||

| :''Many think that the rule in reference to pitching will greatly promote the attractiveness of the game... The time will come when slow, twisting balls, pitched with skill and judgment, will supersede the rifle-shooter of would-be Creightons. The fast pitching system is “played out”. Spectators have become disgusted with waiting hour after hour to see three or four innings played, the pitcher and catcher tired from over-work, the batsman annoyed and irritated from waiting for good balls, the fieldsmen idle and cross for want of something to do, and all the “vim” and spirit of the game being lost, because “we want to show ‘em what a bully swift pitcher we’ve got”. | |||

| :''These new rules, in this respect, practically take the most effective part of swift pitching out of the hands of pitchers; for, to tell the truth, not a solitary instance of fair pitching, that was very swift, have we seen since Creighton died.''<ref> New York ''Sunday Mercury,'' March 2, 1864</ref> | |||

| ==Posthumous postscripts== | |||

| ]The 12-foot marble obelisk marking Creighton's grave at Green-Wood was originally crowned with a large marble baseball. However, the ] went missing and was presumed stolen in the late 19th or early 20th century.<ref name="ryczek14"/> In 2014, after a successful funding campaign to restore the monument, a replica of the original finial was installed and unveiled during a public ceremony.<ref> ''Brooklyn Paper'', April 22, 2014</ref><ref> ''Wall Street Journal'', April 16, 2014</ref> | |||

| Only two photographs of Creighton are known to exist, one of him posing as a pitcher, the other as a member of the Brooklyn Excelsiors. | |||

| The television series '']'' made reference to Creighton in the ] episode "]", where ] has him pegged as the right fielder for his company's softball team. His assistant ] has to point out that all the players Mr. Burns had selected are long dead, making reference in particular to Creighton by saying "In fact, your right fielder has been dead for 130 years."<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://calltothepen.com/2017/02/23/homer-at-the-bat-cooperstown-to-honor-springfield/ |title=Homer at the Bat: Cooperstown to Honor Springfield |date=2017-02-23 |work=Call to the Pen |access-date=2018-06-11 |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 57: | Line 88: | ||

| ==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

| *{{cite book|last=Robbins|first=Michael W.|title=Brooklyn: a state of mind|year=2000|publisher=]|isbn=0-7611-1635-4}} | *{{cite book|last=Robbins|first=Michael W.|title=Brooklyn: a state of mind|url=https://archive.org/details/brooklynstateofm00mich|url-access=registration|year=2000|publisher=]|isbn=0-7611-1635-4}} | ||

| *{{cite book|last=Ryczek|first=William J.|title=When Johnny came sliding home: the post-Civil War baseball boom, 1865-1870|year=1998|publisher=]|isbn=9780786405145}} | *{{cite book|last=Ryczek|first=William J.|title=When Johnny came sliding home: the post-Civil War baseball boom, 1865-1870|url=https://archive.org/details/whenjohnnycamesl0000rycz|url-access=registration|year=1998|publisher=]|isbn=9780786405145}} | ||

| *{{cite book|last=Spink|first=Alfred Henry|title=The National Game|year=1911|publisher=]|isbn=9780809323043}} | *{{cite book|last=Spink|first=Alfred Henry|title=The National Game|year=1911|publisher=]|isbn=9780809323043}} | ||

| *{{cite book|last=Terry|first=James L.|title=Long Before the Dodgers: Baseball in Brooklyn, 1855-1884|year=2002|publisher=]|isbn=9780786412297}} | *{{cite book|last=Terry|first=James L.|title=Long Before the Dodgers: Baseball in Brooklyn, 1855-1884|year=2002|publisher=]|isbn=9780786412297}} | ||

| Line 64: | Line 95: | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category}} | |||

| {{Portal|Baseball}} | {{Portal|Baseball}} | ||

| * {{Cricketarchive|ref=Archive/Players/183/183735/183735.html}} | * {{Cricketarchive|ref=Archive/Players/183/183735/183735.html}} | ||

| * https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IRD5lIyu9UA | |||

| {{Persondata <!-- Metadata: see ]. --> | |||

| | NAME = Creighton, Jim | |||

| | ALTERNATIVE NAMES = | |||

| | SHORT DESCRIPTION = baseball player | |||

| | DATE OF BIRTH = April 15, 1841 | |||

| | PLACE OF BIRTH = Manhattan, New York City, New York | |||

| | DATE OF DEATH = October 18, 1862 | |||

| | PLACE OF DEATH = Brooklyn, New York City, New York | |||

| }} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Creighton, Jim}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Creighton, Jim}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 12:59, 30 December 2024

American baseball player (1841–1862) For another person, see Jim Creighton (basketball). Baseball player| Jim Creighton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: (1841-04-15)April 15, 1841 Manhattan, New York, US | |

| Died: October 18, 1862(1862-10-18) (aged 21) Brooklyn, New York, US | |

| Batted: RightThrew: Right | |

| Teams | |

|

James Creighton, Jr. (April 15, 1841 – October 18, 1862) was an American baseball player during the game's amateur era, and is considered by historians to be the sport's first superstar and one of its earliest paid competitors. In 1860 and 1862 he played for one of the most dominant teams of the era, the Excelsior of Brooklyn. He also was reputed to be a superb cricketer, and played in many amateur and professional cricket matches.

During this early, pre-professional period of baseball's evolution, Creighton's pitching technique changed the sport from a game that showcased hitting, running, and fielding into a confrontation between the pitcher and batter. Under rules of the day, a pitcher was required to deliver the ball in an underhand motion with a stiff arm/stiff wrist movement. The intention was to induce the batter to swing and put the ball in play, thus initiating action on the diamond. Creighton's swift delivery was difficult for opposing batters to hit, because they were accustomed to balls being lobbed over the plate.

The speed with which Creighton was able to hurl the ball had previously been considered impossible without movement of the elbow or wrist, which was prohibited by existing rules. If there were any such movements by Creighton, they were imperceptible. Nonetheless, he was accused by some opponents and spectators of using an illegal delivery. In effect, because Creighton was exceptionally successful, his opponents assumed he was cheating.

However, the competitive advantage of this delivery, and his success as a pitcher, eventually led others to emulate his technique. Historian Thomas Gilbert, in his 2015 book Playing First: Early Baseball Lives at Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery, which includes a chapter on Creighton and his extended family, referred to Creighton's pitching style as "weaponizing the ball."

In October 1862, at the height of his popularity, Creighton suffered a ruptured abdominal hernia, a condition possibly caused and exacerbated by his unorthodox pitching motion and high per-game pitch counts. The rupture caused internal bleeding, and Creighton died four days later.

Early life

Creighton was born on April 15, 1841 in Manhattan to James and Jane Creighton, and was raised in Brooklyn. By age 16, he had become recognized in the Brooklyn area for his batting skills in both baseball and cricket. In 1857, along with other neighborhood youths, he formed a local baseball club named Young America. During this period, there were no organized leagues and few competing teams, so amateur clubs spent much of their time practicing and playing intra-squad games, with occasional matches against rivals. Young America played a few match games before disbanding. Creighton then became a member of Niagara of Brooklyn, playing second base.

Baseball

Discovery by the Star Club

In a match on July 19, 1859, the Niagaras were being heavily outscored by the Star Club of Brooklyn. Creighton, who had thus far been used by the team primarily in the infield, was brought on as a substitute pitcher. Using what observers described as a "low, swift delivery," Creighton achieved uncommonly swift velocity. With the balls "rising from the ground past the shoulder to the catcher," the Star batsmen were unable to hit them effectively. Under the rules of baseball at the time, a pitcher was required to deliver the ball underhanded with arm locked straight at the elbow and at the wrist. Another technique he used was to give the baseball spinning motion, making it harder for the batters to hit it squarely. Additionally, he threw a high-arcing slower pitch called a "dew-drop." It was the job of the pitcher to make it easy for the batter to hit the ball as fielding was considered the game's true skill. Star batsmen claimed that Creighton was using an illegal snap of the wrist to deliver the pitch. The Star Club eventually won the game, but following the match, Creighton left the Niagaras and joined the Stars.

Joins the Excelsiors

Before the 1860 season began, Creighton left the Star Club and joined one of the highest-profiled clubs in the game at the time, the Excelsior of Brooklyn. With their new star pitcher, the Excelsiors became a national sensation. They organized the first known baseball tour outside of their home region, taking on teams along the East Coast of the United States. That first season, Creighton scored 47 runs in 20 match games, and was retired just 56 times and did not strike out. In a game against the St. George Cricket Club on November 8, he recorded baseball's first shutout. In addition to his pitching skills, he became the game's best batter. In 1862, he batted 1.000, getting hits in all 65 of his at-bats. (The Excelsiors did not play in 1861, as many players had left to fight in the Civil War.)

Pitching style

When observing Creighton bowling in a cricket match, English cricketer John Lillywhite commented, "Why, that man is not bowling, he is throwing underhand. It is the best disguised underhand throwing I ever saw, and might readily be taken for a fair delivery." Another observer said that his pitch was "as swift as it was shot out of cannon." Excelsior teammate John (a.k.a. "Jack") Chapman later in his life wrote that Creighton "...had wonderful speed, and, with it, splendid command. He was fairly unhittable." Others, especially more tradition-minded members in the baseball community, complained that not only were his pitches illegal, but also unsportsmanlike. After Creighton held the famed rival Brooklyn Atlantics to five runs, an extraordinarily low total for the era, the Brooklyn Eagle dispatched a reporter to determine whether or not his pitch was legal. The journalistic witness reported that Creighton was throwing a "fair square pitch", rather than a "jerk" or an "underhand throw."

Professionalism

During this era of baseball, the game was an amateur sport, and clubs served as social organizations with sporting activities rather than as strictly sports alliances. Creighton was described as principled, unassuming, and gentlemanly — traits considered ideal during the amateur era. However, rumors circulated that clubs had started paying exceptional players in an under-the-table manner. Clubs would hire the player ostensibly for a position of responsibility within their administration, or the player would be given a sinecure in a municipal department, with the understanding that there were no actual duties required beyond playing for the sports team.

In 1860, the Excelsior Club lured Creighton, along with teammates George Flanley and the brothers Asa and Henry Brainard. All but Henry Brainard were quietly paid a salary, with Creighton earning $500, thus making these men some of the earliest "professional" baseball players. After winning the National Association championship in 1860, Creighton and Asa Brainard jumped from the Excelsior Club to the Atlantic Club of Brooklyn. This move lasted only three weeks, and without having played any games, both players returned to the Excelsiors. While the practice of pay-for-play unofficially spread throughout baseball in the coming years, open professionalism didn't begin until the 1869 season, when the Cincinnati Red Stockings paid a salary to each member of the team.

Cricket

Creighton was considered a prominent member of the cricket community, playing both amateur and professional. He performed for the American Cricket Club in both 1861 and 1862, often playing against the all-England team, whether at Hoboken's Elysian Fields or elsewhere. Though the English teams would dominate these matches, Creighton fared well. In an 1859 match of 11 Englishmen against 16 Americans, he clean bowled five wickets out of six successive balls.

Death

There has been some historical controversy about the circumstances of Creighton's death. On October 14, 1862, Creighton played second base in a match on the Excelsior Grounds against the Union of Morrisania club, while Brainard pitched. Creighton had allegedly hit four doubles in four at bats during the first five innings. As chronicled 50 years later by a witness to the game, Jack Chapman, Creighton took over pitching duties from Brainard in the sixth inning, and in his next at bat hit a home run. While swinging the bat, he allegedly suffered an injury in his abdominal area. According to Chapman, when Creighton crossed home plate, he commented to the next batter, George Flanley, that he heard something snap. After the game, he began to experience severe pain and hemorrhaging in his abdomen. He died in his father's home on October 18 at the age of 21. In an 1887 issue of an early sports newspaper, the Sporting Life, a letter-writer, who signed only as "Old Timer", sent in his account of the event. This account reported it as a ruptured bladder; in the light of modern medical understanding, the injury was most likely a ruptured inguinal hernia.

However, subsequent research indicates that Creighton's death by hitting a home run was fabricated years later to dramatize his martyrdom. “Dying while hitting a long home run is a great story; it’s just not true,” said Tom Shieber, senior curator of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Shieber researched original news sources and found no references to Creighton hitting a home run in that game. The death-by-home-run myth was popularized, and probably started, five decades later by Chapman. Alfred H. Spink’s 1910 book The National Game quoted Chapman as saying, “I was present at the game between the Excelsiors and the Unions of Morrisiana at which Jim Creighton injured himself. He did it in hitting out a home run. When he had crossed the rubber he turned to George Flanley and said, ‘I must have snapped my belt.’” Countless historians have refuted this legend, but it has taken root as factual.

Later research has suggested that Creighton's hernia was chronic, and that the tremendous workload from baseball and cricket contributed to worsening the hernia. In that era, balls and strikes were not called, and batters who couldn't hit Creighton's rapid deliveries adapted by refusing to swing at good pitches, forcing Creighton to throw well over 300 pitches per match. Pitching with great force and the exaggerated body contortions necessary to achieve high velocity exacerbated his condition.

Creighton's death caused concern in the sports world that public perceptions of baseball and cricket would focus on the inherent dangers of their play, hurting the sports' popularity. Though it is generally accepted that Creighton fatally injured himself while playing baseball, it was reported that the Excelsior president, Dr. Joseph Jones, made comments during the National Association convention of 1862 that constituted an attempt to "correct" this notion. He claimed that Creighton had suffered the injury, instead, while playing cricket in a match on October 7. Later research claims that Dr. Jones' assertions are correct; Creighton had died of a "strangulated intestine", and did not hit a home run during his final game. Dr. Jones' remarks have been interpreted as his attempt to save baseball's image, and its nearly equal standing with cricket, as well as his team's legacy after losing their best player. Baseball at the time was constantly "looking forward", and Creighton's death provided the sport with a certain mythology and much-needed nostalgia.

Creighton was buried in Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery. His gravesite was marked by a 12-foot marble obelisk crowned with a large marble baseball.

Legacy

Baseball writer John Thorn commented in his book, Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game, that Creighton "was baseball's first hero, and I believe, the most important player not inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame."

At the time, the sport of cricket was the most popular team sport in the United States, but Creighton and the Excelsiors had brought considerable attention to baseball. Creighton's popularity grew substantially after his death. In the following decade, teams began honoring him by naming themselves after him, and others paid tribute by visiting his gravesite. As long as twenty years later, though the public adored their star pitchers, comparisons to Creighton would inevitably emerge. It was not considered controversial to compliment a pitcher with the caveat that he "warn't no Creighton." For years following his death, the Excelsiors' program included a portrait of their team with Creighton, shrouded in black, featured prominently in the center.

Creighton's indirect legacy is perhaps most profoundly seen in what is now considered a fundamental component of the game: the called ball and the walk. Neither existed during Creighton's lifetime, but his many imitators, who pitched with Creighton's velocity but not his control, prompted batters to stand at the plate without swinging for lengthy intervals, waiting for a pitch within reach. Consequently, the sport's then-governing body, the National Association of Base Ball Players, introduced a rule for the 1864 season which penalized pitchers who repeatedly failed to deliver "good balls:" the called ball, three of which gave the batter a free pass to first base.

- Many think that the rule in reference to pitching will greatly promote the attractiveness of the game... The time will come when slow, twisting balls, pitched with skill and judgment, will supersede the rifle-shooter of would-be Creightons. The fast pitching system is “played out”. Spectators have become disgusted with waiting hour after hour to see three or four innings played, the pitcher and catcher tired from over-work, the batsman annoyed and irritated from waiting for good balls, the fieldsmen idle and cross for want of something to do, and all the “vim” and spirit of the game being lost, because “we want to show ‘em what a bully swift pitcher we’ve got”.

- These new rules, in this respect, practically take the most effective part of swift pitching out of the hands of pitchers; for, to tell the truth, not a solitary instance of fair pitching, that was very swift, have we seen since Creighton died.

Posthumous postscripts

The 12-foot marble obelisk marking Creighton's grave at Green-Wood was originally crowned with a large marble baseball. However, the finial went missing and was presumed stolen in the late 19th or early 20th century. In 2014, after a successful funding campaign to restore the monument, a replica of the original finial was installed and unveiled during a public ceremony.

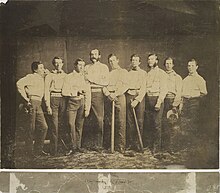

Only two photographs of Creighton are known to exist, one of him posing as a pitcher, the other as a member of the Brooklyn Excelsiors.

The television series The Simpsons made reference to Creighton in the Season 3 episode "Homer at the Bat", where Mr. Burns has him pegged as the right fielder for his company's softball team. His assistant Smithers has to point out that all the players Mr. Burns had selected are long dead, making reference in particular to Creighton by saying "In fact, your right fielder has been dead for 130 years."

Notes

- Players of the era held the bat with their hands separated and swung by twisting their upper-body with little or no movement of the wrists.

References

- Gilbert, Thomas, Playing First: Early Baseball Lives at Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery, published by The Green-Wood Cemetery, September 2015

- ^ Thorn, p. 122

- ^ Thorn, John. "Jim Creighton".

- ^ Thorn, p. 123

- ^ Robbins, p. 241

- ^ Ryczek, p. 4

- Brown, Craig, "1860 Excelsior, Brooklyn," Threads of Our Game, May 25, 2014

- "Excelsior vs. St. George". Brooklyn Eagle. November 10, 1860. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012.

- Robbins, p. 242

- Thorn, p. 120

- Thorn, John (2018-01-08). "Last Hurrah for the Cincinnati Red Stockings". Our Game. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- Spink, p. 128

- Terry, p. 140

- Robert Smith (Baseball in America, Holt Rinehart Winston, 1961, p. 10,13)

- Coffey, Wayne, “Daily News Sports Hall of Fame Candidates,” New York Daily News, June 18, 2006.

- Spink, Alfred H., The National Game (St. Louis: The National Game Publishing Co., 1910), 128.

- Schweber, Nate (2012-10-18). "Recalling a New Pitch and a Strange Death". New York Times. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

- ^ Thorn, p. 126

- ^ Ryczek, p. 14

- Unraveling a Baseball Mystery, John Thorn, Our Game

- ^ Thorn, p. 127

- New York Sunday Mercury, March 2, 1864

- Jaeger, Max, "Dusting Off the Plate: Baseball Great's Restored Burial Monument Unveiled," Brooklyn Paper, April 22, 2014

- Helsel, Phil, "Historians Restore Grave of a Pioneering Brooklyn Baseball Pitcher," Wall Street Journal, April 16, 2014

- "Homer at the Bat: Cooperstown to Honor Springfield". Call to the Pen. 2017-02-23. Retrieved 2018-06-11.

Bibliography

- Robbins, Michael W. (2000). Brooklyn: a state of mind. Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7611-1635-4.

- Ryczek, William J. (1998). When Johnny came sliding home: the post-Civil War baseball boom, 1865-1870. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786405145.

- Spink, Alfred Henry (1911). The National Game. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 9780809323043.

- Terry, James L. (2002). Long Before the Dodgers: Baseball in Brooklyn, 1855-1884. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786412297.

- Thorn, John (2012). Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game (reprint, illustrated ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743294041.

External links

- Jim Creighton at CricketArchive (subscription required)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IRD5lIyu9UA