| Revision as of 17:24, 10 October 2013 edit81.178.139.155 (talk) um it obviously says its mediamatters making the claim so not in wikipedias voice← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:44, 26 December 2024 edit undoTrystan (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,532 edits →Subsequent reporting: Move sources about the 20/20 report to that subsection; more detail on what the sources say. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

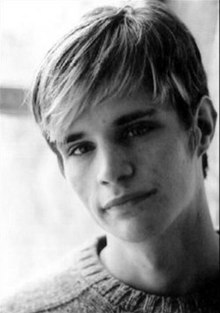

| {{Short description|Gay American murder victim (1976–1998)}} | |||

| {{about|the murder victim|the Detroit, Michigan based sports reporter|Matt Shepard (sportscaster)}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Matt Shepard|the sportscaster|Matt Shepard (sportscaster)}} | |||

| <noinclude>{{Requested move notice|1=Murder of Matthew Shepard|2=Talk:Matthew Shepard#Requested move 22 December 2024}} | |||

| </noinclude>{{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=September 2021}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=October 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox person | {{Infobox person | ||

| | |

| image = Matthew Shepard.jpg | ||

| | |

| birth_name = Matthew Wayne Shepard | ||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1976|12|1}} | |||

| | image_size = 220px | |||

| | birth_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1976|12|01}} | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1998|10|12|1976|12|1}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], US | |||

| | death_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1998|10|12|1976|12|01|mf=yes}} | |||

| | resting_place = ] | |||

| | death_place = ] | |||

| | death_cause = ] ( |

| death_cause = ] (]) | ||

| | |

| alma_mater = ] | ||

| | parents = {{ubl|]|]}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Matthew Wayne Shepard''' (December 1, 1976 – October 12, 1998) was an American student at the ] who was beaten, tortured, and left to die near ] on the night of October 6, 1998.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.matthewshepard.org/about-us/|title=About Us|work=Matthew Shepard Foundation|access-date=November 19, 2017|language=en-US|archive-date=December 1, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171201031209/https://www.matthewshepard.org/about-us/|url-status=live}}</ref> He was taken by rescuers to ] in ], where he died six days later from severe head injuries received during the attack. | |||

| Suspects Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson were arrested shortly after the attack and charged with ] following Shepard's death. Significant media coverage was given to the murder and what role Shepard's sexual orientation played as a motive for the crime, as he was ]. | |||

| '''Matthew Wayne Shepard''' (December 1, 1976 – October 12, 1998) was an American student at the ] who was tortured and murdered near ] in October 1998. He was attacked on the night of October 6–7, and died at ] in ], on October 12 from severe head injuries. | |||

| The prosecutor argued that the murder of Shepard was premeditated and driven by ]. McKinney's defense counsel countered by arguing that he had intended only to rob Shepard but killed him in a rage when Shepard made a sexual advance toward him. McKinney's girlfriend told police that he had been motivated by ], but later recanted her statement, saying that she had lied because she thought it would help him. Henderson pleaded guilty to murder, and McKinney was tried and found guilty of murder; each of them received two ]. | |||

| During the trial, it was widely reported that Shepard was targeted because he was gay; a Laramie police officer testified at a pretrial hearing that the violence against Shepard was due to how the attacker " about gays", per an interview of the attacker's girlfriend who said she received that explanation.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/21/us/witnesses-trace-brutal-killing-of-gay-student.html?pagewanted=all |title=Witnesses Trace Brutal Killing of Gay Student |first=James |last=Brooke |date=November 21, 1998 |work=] |accessdate=September 17, 2013 }}</ref> Shepard's murder brought national and international attention to ] legislation at the state and federal levels.<ref name=life>{{cite web |url=http://www.matthewshepard.org/site/PageServer |title=Matthew Shepard Foundation webpage |accessdate=4 October 2009 |publisher=Matthew Shepard Foundation |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080729005923/http://www.matthewshepard.org/site/PageServer |archivedate = July 29, 2008}}</ref> | |||

| Shepard's murder brought national and international attention to ] legislation at both the state and federal level.<ref name=life>{{cite web|url=http://www.matthewshepard.org/site/PageServer|title=Matthew Shepard Foundation webpage|access-date=October 4, 2009|website=Matthew Shepard Foundation|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080729005923/http://www.matthewshepard.org/site/PageServer|archive-date=July 29, 2008}}</ref> In October 2009, the ] passed the ] (commonly the "Matthew Shepard Act" or "Shepard/Byrd Act" for short), and on October 28, 2009, President ] signed the legislation into law.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://content.usatoday.com/communities/theoval/post/2009/10/620000629/1|title=Obama signs hate-crimes law rooted in crimes of 1998|work=]|date=October 28, 2009|access-date=September 23, 2011|archive-date=September 18, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110918191421/http://content.usatoday.com/communities/theoval/post/2009/10/620000629/1|url-status=live}}</ref> Following their son's murder, ] and ] became ]s and established the ]. Shepard's murder inspired ], including ''The Laramie Project'' (] and ]) and Judy Shepard's 2009 memoir '']''. | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

| Shepard was born in ] |

Matthew Shepard was born in 1976 in ]; he was the first of two sons born to ] and ]. His younger brother, Logan, was born in 1981. The two brothers had a close relationship.<ref name=":0">{{Cite magazine|url=http://www.vanityfair.com/news/1999/13/matthew-shepard-199903|title=The Crucifixion of Matthew Shepard|magazine=Vanity Fair|date=January 8, 2014|access-date=May 18, 2016|archive-date=October 13, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151013013248/http://www.vanityfair.com/news/1999/13/matthew-shepard-199903|url-status=live}}</ref> Shepard attended ], ], and ] for his freshman through junior years. As a child, he was "friendly with all his classmates", but was targeted and teased due to his small stature and lack of athleticism.<ref name=":0" /> He developed an interest in politics at an early age.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| ] hired his father in the summer of 1994, and Shepard's parents subsequently resided at the ]. During that time, Shepard attended the ] (TASIS),<ref>{{cite news|title=Matthew Shepard's Mother Aims to Speak With His Voice|author=Julie Cart|newspaper=]|date=September 14, 1999|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-sep-14-mn-9950-story.html|access-date=November 3, 2009|archive-date=July 9, 2012|archive-url=https://archive.today/20120709120020/http://articles.latimes.com/1999/sep/14/news/mn-9950?pg=2|url-status=live}}</ref> from which he graduated in May 1995. There, he participated in theater, and took ] and ] courses. He then attended ] in ] and ] in ], before settling in ], ]. Shepard became a first-year ] major at the ] in Laramie with a minor in languages,<ref name=":0" /> and was chosen as the student representative for the Wyoming Environmental Council.<ref name=life/> | |||

| He was described by his father as "an optimistic and accepting young man who had a special gift of relating to almost everyone. He was the type of person who was very approachable and always looked to new challenges. Matthew had a great passion for equality and always stood up for the acceptance of people's differences."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.muhlenbergweekly.com/judy-shepard-speaks-out-against-anti-gay-violence-1.2497979#.TwZrlJhz045 |title=Judy Shepard speaks out against anti-gay violence |first1=Jillian |last1=Bevacqua |first2=Torie |last2=Paone |date=July 5, 2011 |work=Muhlenberg Weekly}}</ref> | |||

| Shepard was an ] and once served as an ] in the church.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Fortin |first1=Jacey |title=Matthew Shepard Will Be Interred at the Washington National Cathedral, 20 Years After His Death |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/11/us/matthew-shepard-ashes-cathedral.html |website=] |date=October 11, 2018 |access-date=October 14, 2018 |archive-date=October 11, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181011233316/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/11/us/matthew-shepard-ashes-cathedral.html |url-status=live }}</ref> He was described by his father as "an optimistic and accepting young man who had a special gift of relating to almost everyone. He was the type of person who was very approachable and always looked to new challenges. Shepard had a great passion for equality and always stood up for the acceptance of people's differences."<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.muhlenbergweekly.com/judy-shepard-speaks-out-against-anti-gay-violence-1.2497979|title=Judy Shepard speaks out against anti-gay violence|first1=Jillian|last1=Bevacqua|first2=Torie|last2=Paone|date=July 5, 2011|work=Muhlenberg Weekly|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131202231211/http://www.muhlenbergweekly.com/judy-shepard-speaks-out-against-anti-gay-violence-1.2497979|archive-date=December 2, 2013}}</ref> Michele Josue, who had been Shepard's friend and later created a documentary about him, ''Matt Shepard Is a Friend of Mine,'' described him as "a tenderhearted and kind person."<ref name=Ring>{{cite magazine |url=http://www.advocate.com/arts-entertainment/film/2015/03/02/getting-know-real-matthew-shepard |title=Getting to Know the Real Matthew Shepard |magazine=The Advocate |date=March 2, 2015 |access-date=March 20, 2017 |first=Trudy |last=Ring |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161221064856/http://www.advocate.com/arts-entertainment/film/2015/03/02/getting-know-real-matthew-shepard |archive-date=December 21, 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In February 1995, during a high school trip to ], Shepard was beaten and raped, causing him to experience depression and panic attacks, according to his mother. One of Shepard's friends feared that his depression had driven him to become involved with drugs during his time in college.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://abcnews.go.com/2020/story?id=277685&page=1&singlePage=true#.TxnxPpg9RCc |title=New Details Emerge in Matthew Shepard Murder |date=November 26, 2004 |work=]}}</ref> | |||

| In 1995, Shepard was abducted, beaten and raped during a high school trip to ].<ref name="abcnews"/><ref name="Bindel"/> This caused him to experience depression and panic attacks, according to his mother.<ref name="abcnews"/> One of Shepard's friends feared that his depression had driven him to become involved with drugs during his time at college.<ref name="abcnews"/> Multiple times, Shepard was hospitalized due to his clinical depression and suicidal ideation.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ==Murder== | ==Murder== | ||

| <!-- ] redirects here. If this section name is changed, please leave an {{Anchor}} or update the redirect. --> | |||

| <!-- Deleted image removed: ] --> | |||

| On the night of October 6, 1998, Shepard was approached by Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson at the Fireside Lounge in Laramie; all three men were in their early 20s.<ref name=NYTref>{{cite news|last=Brooke|first=James|title=Gay Man Dies From Attack, Fanning Outrage and Debate|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/13/us/gay-man-dies-from-attack-fanning-outrage-and-debate.html|access-date=May 29, 2013|newspaper=The New York Times|date=October 12, 1998|archive-date=November 2, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141102220600/http://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/13/us/gay-man-dies-from-attack-fanning-outrage-and-debate.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="abcnews"/> McKinney and Henderson offered to give Shepard a ride home.<ref name=trutv/><ref>{{cite news|title=Killer: Shepard Didn't Make Advances|url=http://dir.salon.com/story/news/feature/1999/11/06/witness/index.html|work=]|access-date=December 7, 2007|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110606223846/http://dir.salon.com/story/news/feature/1999/11/06/witness/index.html|archive-date=June 6, 2011}}</ref> They subsequently drove to a remote rural area and proceeded to rob, ], and ] Shepard, tying him to a ] and leaving him to die.<ref name=mmatthew>{{cite book|author=Shepard, Judy|title=The Meaning of Matthew: My Son's Murder in Laramie, and a World Transformed|publisher=Penguin Group USA|location=New York|year=2009|isbn=978-1-59463-057-6|url=https://archive.org/details/meaningofmatthew00shep}}</ref> It was erroneously reported by the news that he had been tied to a ].<ref name="mmatthew"/> Many media reports contained the graphic account of the pistol-whipping and his fractured skull. Reports described how Shepard was beaten so brutally that his face was completely covered in blood, except where it had been partially cleansed by his tears.<ref name="Bindel" /><ref>{{cite book|title=Losing Matt Shepard: life and politics in the aftermath of anti-gay murder|last=Loffreda|first=Beth|year=2000|publisher=Columbia University Press|location=New York|isbn=0-231-11858-9|url=https://archive.org/details/losingmattshepar00loff}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Chiasson|first=Lloyd|title=Illusive Shadows: Justice, Media, and Socially Significant American Trials|url=https://archive.org/details/illusiveshadowsj00chia|url-access=limited|publisher=Praeger|date=November 30, 2003|page=|isbn=978-0-275-97507-4}}</ref> | |||

| The assailants' girlfriends testified that neither McKinney nor Henderson was under the influence of alcohol or other drugs at the time of the attack.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://homes.thedailycamera.com/extra/shepard/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080424091724/http://homes.thedailycamera.com/extra/shepard/|archive-date=April 24, 2008|title=The Daily Camera:Matthew Shepard Murder|access-date=April 6, 2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://homes.thedailycamera.com/extra/shepard/29bshep.html|title=Girlfriend: McKinney told of killing|last=Black|first=Robert W.|work=The Daily Camera|date=October 29, 1999}}{{dead link|date=December 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> McKinney and Henderson testified that they learned of Shepard's address and intended to steal from his home as well. After attacking Shepard and leaving him tied to the fence in near-freezing temperatures, McKinney and Henderson returned to town. McKinney proceeded to pick a fight with two men, 19-year-old Emiliano Morales and 18-year-old Jeremy Herrara. The fight resulted in head wounds for both Morales and McKinney.<ref>] (October 16, 1998), {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171201132826/http://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/16/us/men-held-in-beating-lived-on-the-fringes.html |date=December 1, 2017 }} '']''</ref> Police officer Flint Waters arrived at the scene of the fight. He arrested Henderson, searched McKinney's truck, and found a blood-smeared gun along with Shepard's shoes and credit card.<ref name="abcnews">{{cite web|url=https://abcnews.go.com/US/matthew-shepard-legacy-gay-college-student-20-years/story?id=277685|title=New Details Emerge in Matthew Shepard Murder|publisher=ABC News Internet Ventures|access-date=June 7, 2009|date=November 26, 2004|archive-date=October 6, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191006142444/https://abcnews.go.com/US/matthew-shepard-legacy-gay-college-student-20-years/story?id=277685|url-status=live}}</ref> Henderson and McKinney later tried to persuade their girlfriends to provide alibis for them and help them dispose of evidence.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/13/wyoming.attack.02/index.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080508011253/http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/13/wyoming.attack.02/index.html|archive-date=May 8, 2008 |title=New details emerge about suspects in gay attack|access-date=January 21, 2007 |publisher=]|date=October 13, 1998}}</ref> | |||

| On the night of October 6–7, 1998, Shepard met Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson at the Fireside Lounge in ].<ref name=NYTref>{{cite news|last=Brooke|first=James|title=Gay Man Dies From Attack, Fanning Outrage and Debate|url=http://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/13/us/gay-man-dies-from-attack-fanning-outrage-and-debate.html?pagewanted=all|accessdate=May 29, 2013|newspaper=The New York Times|date=Original: October 12, 1998}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=New Details Emerge in Matthew Shepard Murder|url=http://abcnews.go.com/2020/story?id=277685&page=2}}</ref> It was decided that McKinney and Henderson would give Shepard a ride home.<ref>{{cite web|title=Killer: Shepard Didn't Make Advances|url=http://dir.salon.com/story/news/feature/1999/11/06/witness/index.html|publisher=]|accessdate=2007-12-07}}</ref> McKinney and Henderson subsequently drove the car to a remote, ] area and proceeded to rob, ], and ] Shepard, tying him to a fence and leaving him to die. According to their court testimony, McKinney and Henderson also discovered his address and intended to steal from his home. Still tied to the fence, Shepard, who was still alive but in a coma, was discovered 18 hours later by Aaron Kreifels, a cyclist who initially mistook Shepard for a ].<ref>{{cite news|first=Jim|last=Hughes|title=Wyo. cyclist recalls tragic discovery|url=http://www.texasdude.com/related.htm|publisher=The Denver Post|newspaper=The Denver Post|location=Denver|date=15 October 1998}}</ref> | |||

| Still tied to the fence, Shepard was in a coma eighteen hours after the attack when he was discovered by Aaron Kreifels, a cyclist who initially mistook Shepard for a ].<ref>{{cite news|title=Wyo. bicyclist recalls tragic discovery|work=The Denver Post|date=October 15, 1998|author=Hughes, Jim|page=A01}}</ref> Reggie Fluty, the first police officer to arrive at the scene, found Shepard alive but covered in blood. Shepard was transported first to Ivinson Memorial Hospital in Laramie before being moved to the more advanced ] ward at ] in ].<ref>{{cite book |last= Loffreda |first= Beth |title=Losing Matt Shepard: Life and Politics in the Aftermath of Anti-Gay Murder |url= https://archive.org/details/losingmattshepar00loff |url-access= registration |publisher=Columbia University Press |year=2000 |isbn=9780231500289}}</ref> He had suffered ] to the back of his head and in front of his right ear. He experienced severe ] damage, which affected his body's ability to regulate his ], ], and other ]. There were also about a dozen small ] around his head, face, and neck. His injuries were deemed too severe for doctors to operate. Shepard never regained consciousness and remained on full ]. While he lay in ] and in the days following the attack, ]s were held in countries around the world.<ref>{{cite web|title=University of Wyoming Matthew Shepard Resource Site|url=http://www.uwyo.edu/News/shepard/|publisher=]|access-date=November 1, 2006|archive-date=August 5, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120805225902/http://www.uwyo.edu/news/shepard/|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.canada.com/story_print.html?id=7dfd5ad0-e31b-44e8-9513-8abcf02654c6&sponsor=|title=Hate crimes bill still elusive 10 years after savage gay killing|work=The Ottawa Citizen|date=October 14, 2008|agency=CanWest MediaWorks Publications Inc.|access-date=October 4, 2013|location=Ottawa, Canada|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160320051930/http://www.canada.com/story_print.html?id=7dfd5ad0-e31b-44e8-9513-8abcf02654c6&sponsor=|archive-date=March 20, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=GmNWAAAAIBAJ&pg=6564%2C5111854|title=Symbol of outrage|work=The Spokesman-Review|date=October 17, 1998|access-date=October 4, 2013|author=Egerton, Brooks|page=A2|archive-date=May 21, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210521070142/https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=GmNWAAAAIBAJ&pg=6564,5111854|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Reggie Fluty, the first police officer on the scene, found Shepard alive but covered in blood. The ] issued by the ] Sheriff's Department were faulty and Fluty's supply ran out. She decided to use her bare hands to clear an airway in Shepard's bloody mouth. A day later, she was informed that Shepard was ] and that she had been exposed because of cuts on her hands. After taking an ] regimen for several months, she proved not to have been infected.<ref name="reavill-aftermath">{{cite book | url=http://books.google.com/books?id=JyowrVlO5pIC&lpg=PA103&ots=eA23KD0j6T&dq=%22Fluty%22%20%22hiv%22%20%22Matthew%20Shepard%22&pg=PA104#v=onepage&q=Reggie%20Fluty&f=false | title=Aftermath, Inc: Cleaning Up After CSI Goes Home | publisher=Gotham | author=Reavill, Gil | year=2007 | pages=103 | isbn=1592402968}}</ref> Judy Shepard later wrote she learned of Matthew's HIV status during his stay at the hospital following the attack.<ref name="lavmag378">{{cite journal | url=http://www.lavendermagazine.com/uncategorized/magnificent-new-book-about-matthew-shepherd-astonishes-an-interview-with-judy-shepard/ | title=Magnificent New Book About Matthew Shepherd Astonishes | journal=November 19, 2009 | issue=378}}</ref> | |||

| Shepard was pronounced dead six days after the attack at 12:53 a.m. on October 12, 1998.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.03/index.html |publisher=] |title=Murder charges planned in beating death of gay student|access-date=November 1, 2006|date=October 12, 1998|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060822005855/http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.03/index.html|archive-date=August 22, 2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine|last=Lacayo|first=Richard|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989406,00.html|magazine=]|title=The New Struggle|access-date=November 1, 2006|date=October 26, 1998|archive-date=January 29, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110129152139/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989406,00.html|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="CNNBeaten">{{cite news|url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.02/index.html|title=Beaten gay student dies; murder charges planned |publisher=] |access-date=January 14, 2007|date=October 12, 1998|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060620022551/http://cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.02/index.html|archive-date=June 20, 2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://vic.pvhs.org/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/PVHS/PVHS_DOCUMENT_MGMT2/NEWS_REPOSITORY/MATTHEW%20SHEPARD%20MEDICAL%20UPDATE.PDF|publisher=Poudre Valley Health System (Colorado)|title=Matthew Shepard Medical Update|access-date=January 14, 2007|date=October 12, 1998|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070630023857/https://vic.pvhs.org/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/PVHS/PVHS_DOCUMENT_MGMT2/NEWS_REPOSITORY/MATTHEW%20SHEPARD%20MEDICAL%20UPDATE.PDF|archive-date=June 30, 2007}}</ref> He was 21 years old.<ref name=NYTref/> | |||

| Shepard had suffered ] to the back of his head and in front of his right ear. He experienced severe ] damage, which affected his body's ability to regulate ], ], and other ]. There were also about a dozen small ] around his head, face, and neck. His injuries were deemed too severe for doctors to operate. Shepard never regained consciousness and remained on full ]. While he lay in ], and in the days following the attack, candlelight vigils were held around the world.<ref>{{cite web|title=University of Wyoming Matthew Shepard Resource Site|url=http://www.uwyo.edu/News/shepard/|publisher=]|accessdate=2006-11-01}}</ref><ref name="ottawa908">{{cite news | url=http://www.canada.com/story_print.html?id=7dfd5ad0-e31b-44e8-9513-8abcf02654c6&sponsor= | title=Hate crimes bill still elusive 10 years after savage gay killing | work=The Ottawa Citizen | date=October 14, 2008 | agency=CanWest MediaWorks Publications Inc. | accessdate=October 4, 2013 | location=Ottawa}}</ref><ref name="dallas101798">{{cite news | url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=GmNWAAAAIBAJ&sjid=4_EDAAAAIBAJ&dq=matthew-shepard%20candlelight-vigils&pg=6564%2C5111854 | title=Symbol of outrage | work=The Spokesman-Review | date=October 17, 1998 | accessdate=October 4, 2013 | author=Egerton, Brooks | pages=A2}}</ref> | |||

| ===Arrests and trial=== | |||

| Shepard was pronounced dead at 12:53 a.m. on October 12, 1998, at ], in ].<ref>{{cite news|title=CNN Coverage of Matthew Shepard|url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.03/index.html|work=]|title=Murder charges planned in beating death of gay student|accessdate=2006-11-01 | |||

| McKinney and Henderson were arrested and initially charged with attempted ], ], and aggravated ]. After Shepard's death, the charges were upgraded from attempted murder to first-degree murder, which meant that the two defendants were eligible for the ]. Their girlfriends, Kristen Price and Chasity Pasley<!-- Several sources say Chastity, but later and more reliable sources indicate her name is Chasity-->, were charged with being ].<ref name="CNNBeaten" /><ref name="NYTWitnesses"/> At McKinney's November 1998 pretrial hearing, Sergeant Rob Debree testified that McKinney had stated in an interview on October 9 that he and Henderson had identified Shepard as a robbery target and pretended to be gay to lure him out to their truck, and that McKinney had attacked Shepard after Shepard put his hand on McKinney's knee.<ref name="NYTWitnesses">{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/21/us/witnesses-trace-brutal-killing-of-gay-student.html|title=Witnesses Trace Brutal Killing of Gay Student|first=James|last=Brooke|date=November 21, 1998|work=]|access-date=September 17, 2013|archive-date=September 29, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130929125459/http://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/21/us/witnesses-trace-brutal-killing-of-gay-student.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Detective Ben Fritzen testified that Price stated McKinney told her the violence against Shepard was triggered by how McKinney " about gays".<ref name="NYTWitnesses"/> | |||

| |date=October 12, 1998 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20060822005855/http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.03/index.html |archivedate = August 22, 2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Lacayo|first=Richard|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989406,00.html|work=]|title=The New Struggle|accessdate=2006-11-01|date=October 26, 1998}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=CNN Coverage of Matthew Shepard|url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.02/index.html|work=]|title=Beaten gay student dies; murder charges planned |accessdate=2007-01-14 | |||

| |date=October 12, 1998 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20060620022551/http://cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.02/index.html |archivedate = June 20, 2006}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Poudre Valley Health System|url=https://vic.pvhs.org/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/PVHS/PVHS_DOCUMENT_MGMT2/NEWS_REPOSITORY/MATTHEW%20SHEPARD%20MEDICAL%20UPDATE.PDF|work=]|title=Matthew Shepard Medical Update|accessdate=2007-01-14 | |||

| |date=October 12, 1998|format=PDF}}</ref> He was 21 years old.<ref name=NYTref /> | |||

| In December 1998, Pasley pleaded guilty to being an accessory after the fact to first-degree murder.<ref name="NYTGayMurder" /> On April 5, 1999, Henderson avoided going to trial when he pleaded guilty to murder and kidnapping charges. In order to avoid the death penalty, he agreed to testify against McKinney and was sentenced by District Judge Jeffrey A. Donnell to ] ]s. At Henderson's sentencing, his lawyer argued that Shepard had not been targeted because he was gay.<ref name="NYTGayMurder">{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/06/us/gay-murder-trial-ends-with-guilty-plea.html |title=Gay murder trial ends with guilty plea |access-date=November 2, 2014 |first=James |last=Brooke |work=] |date=April 6, 1999 |archive-date=July 23, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150723100203/http://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/06/us/gay-murder-trial-ends-with-guilty-plea.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Funeral protests=== | |||

| Members of the ], led by ], received national attention for picketing Shepard's funeral with signs bearing ] slogans.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gaytoday.com/garchive/events/101498ev.htm |title=Top Story |publisher=Gay Today |date= |accessdate=2012-01-03}}</ref> | |||

| McKinney's trial took place in October and November 1999. Prosecutor Cal Rerucha alleged that McKinney and Henderson pretended to be gay to gain Shepard's trust. Price, McKinney's girlfriend, testified that Henderson and McKinney had "pretended they were gay to get in the truck and rob him."<ref name=trutv>{{cite web|url=http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/criminal_mind/forensics/welner/3.html?print=yes|title=Psychiatry, the Law, and Depravity: Profile of Michael Welner, M.D. Chairman, The Forensic Panel|first=Katherine|last=Ramsland|publisher=]|access-date=September 26, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131203002900/http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/criminal_mind/forensics/welner/3.html?print=yes|archive-date=December 3, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.salon.com/1999/11/01/gay_panic/singleton|archive-url=https://archive.today/20140413020816/http://www.salon.com/1999/11/01/gay_panic/singleton|url-status=dead|archive-date=April 13, 2014|title=Quiet bombshell in Matthew Shepard trial|first=Dave|last=Cullen|date=November 1, 1999|access-date=February 19, 2012|newspaper=Salon}}</ref> McKinney's lawyer attempted to put forward a ], arguing that McKinney was driven to ] by ] by Shepard. This defense was rejected by the judge. McKinney's lawyer stated that the two men wanted to rob Shepard but never intended to kill him.<ref name="abcnews"/> Rerucha argued that the killing had been premeditated, driven by "greed and violence", rather than by Shepard's sexual orientation.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1999/10/26/us/a-defense-to-avoid-execution.html|title=A defense to avoid execution|access-date=November 2, 2014|first=Michael|last=Janofsky|work=]|date=October 26, 1999|archive-date=November 2, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141102220613/http://www.nytimes.com/1999/10/26/us/a-defense-to-avoid-execution.html|url-status=live}}</ref> The jury found McKinney not guilty of premeditated murder but guilty of ] and began to deliberate on the death penalty. Shepard's parents brokered a deal that resulted in McKinney receiving two consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole.<ref>{{cite news |last=Cart |first=Julie |date=November 5, 1999 |title=Killer of Gay Student Is Spared Death Penalty; Courts: Matthew Shepard's father says life in prison shows "mercy to someone who refused to show any mercy." |page=A1 |work=] |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-dec-31-mn-47273-story.html |access-date=October 7, 2023 |archive-date=October 10, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231010055335/https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-dec-31-mn-47273-story.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Henderson and McKinney were ] in the ] in ] and were later transferred to other prisons because of overcrowding.<ref>{{cite news|first=Jean|last=Torkelson|title=Mother's mission: Matthew Shepard's death changes things|url=http://m.rockymountainnews.com/news/2008/oct/03/10-years-later-matthew-shepard-hasnt-been-forgotte|work=Rocky Mountain News|publisher=The E.W. Scripps Co.|date=October 3, 2008|access-date=November 16, 2008|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110715195945/http://m.rockymountainnews.com/news/2008/oct/03/10-years-later-matthew-shepard-hasnt-been-forgotte/|archive-date=July 15, 2011}}</ref> Following her testimony at McKinney's trial, Price pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of misdemeanor interference with a police officer.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.cbsnews.com/news/last-gay-beating-trial-ends/|title=Last gay beating trial ends|date=November 4, 1999|work=]|access-date=November 2, 2014|archive-date=November 2, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141102202843/http://www.cbsnews.com/news/last-gay-beating-trial-ends/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Arrests and trial== | |||

| Police arrested Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson shortly after the attack, finding the bloody gun and Shepard's shoes and wallet in their truck.<ref name="abcnews">{{cite web|url=http://abcnews.go.com/2020/Story?id=277685&page=1|title=New Details Emerge in Matthew Shepard Murder|publisher=ABC News Internet Ventures|accessdate=2009-06-07|date=November 26, 2004}}</ref> Henderson and McKinney later tried to persuade their girlfriends to provide alibis for them.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/13/wyoming.attack.02/index.html |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20080508011253/http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/13/wyoming.attack.02/index.html |archivedate=2008-05-08 |title=New details emerge about suspects in gay attack |accessdate=21 January 2007 |work=CNN.com |publisher=] |date=13 October 1998}}</ref> | |||

| ==Subsequent reporting== | |||

| At trial, McKinney offered various rationales to justify his actions. He originally pleaded the ], arguing that he and Henderson were driven to ] by ] by Shepard. At another point, McKinney's lawyer stated that they had wanted to rob Shepard but never intended to kill him.<ref name="abcnews"/> | |||

| ===''20/20'' report=== | |||

| Shepard's murder continued to attract public attention and media coverage long after the trial was over. In 2004, the ] news program '']'' aired a report by TV journalist ] that quoted statements by McKinney, Henderson, Price, Rerucha, and a lead investigator. The statements alleged that the murder had not been motivated by Shepard's sexuality but was primarily a drug-related robbery that had turned violent.<ref name="abcnews"/> Price said she had lied to police about McKinney having been provoked by an unwanted sexual advance from Shepard, telling Vargas, "I don't think it was a hate crime at all."<ref name="abcnews"/><ref>] (October 22, 2013), {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210704041321/https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304410204579143612270644276 |date=July 4, 2021 }} '']''</ref> Rerucha said, "It was a murder that was once again driven by drugs."<ref name="abcnews"/> | |||

| The report was criticized by ] as relying on speculation and statements by unreliable individuals changing their story.<ref name="Lee">{{cite news|title=ABC News Revisits Student's Killing, and Angers Some Gays|author=Lee, Felicia R.|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/26/us/abc-news-revisits-students-killing-and-angers-some-gays.html|newspaper=The New York Times|date=November 26, 2004|access-date=June 11, 2013|archive-date=July 12, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180712070129/https://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/26/us/abc-news-revisits-students-killing-and-angers-some-gays.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=GLAAD: 10 Questions About ABC'S 20/20 Show on Matthew Shepard|url=http://www.glaad.org/matthewshepard2020|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090514015646/http://www.glaad.org/matthewshepard2020|archive-date=May 14, 2009|access-date=June 11, 2013}}</ref> Judy Shepherd's lawyer described the report as an oversimplification, while ] of ] described it as an attempt to "de-gay the murder".<ref name="Lee" /><ref>{{cite book|last=Charles|first=Casey|title=Critical Queer Studies: Law, Film, and Fiction in Contemporary American Culture|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EwtNwyfhHcEC&q=%22matthew+shepard%22+%2220/20%22+controversial+OR+controversy&pg=PT67|publisher=Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.|year=2012|isbn=978-1409444060|access-date=July 4, 2021|archive-date=July 4, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210704041350/https://books.google.com/books?id=EwtNwyfhHcEC&q=%22matthew+shepard%22+%2220%2F20%22+controversial+OR+controversy&pg=PT67|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=O'Donnell|first=M.|year=2008|title=Gay-hate, journalism and compassionate questioning|journal=Asia Pacific Media Educator|issue=19|pages=113–126|url=http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1304&context=apme|access-date=June 11, 2013|archive-date=October 4, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131004215812/http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1304&context=apme|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The prosecutor in the case alleged that McKinney and Henderson pretended to be gay in order to gain Shepard's trust.<ref>{{cite news|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20081201140327/http://www.courttv.com/archive/trials/henderson/040599_pm_ctv.html |archivedate=December 1, 2008 |url=http://www.courttv.com/archive/trials/henderson/040599_pm_ctv.html|title=Henderson pleads guilty to felony murder in Matthew Shepard case|accessdate=2006-04-06|author=Tuma, Clara, and ]|publisher=]|date=April 5, 1999}}</ref> During the trial, Kristen Price, girlfriend of McKinney, testified that Henderson and McKinney had "pretended they were gay to get in the truck and rob him".<ref name=trutv>{{cite web|url=http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/criminal_mind/forensics/welner/3.html?print=yes |title=Psychiatry, the Law, and Depravity: Profile of Michael Welner, M.D. Chairman, The Forensic Panel |first=Katherine |last=Ramsland |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.salon.com/1999/11/01/gay_panic/singleton/ |title=Quiet bombshell in Matthew Shepard trial |first=Dave |last=Cullen |date=November 1, 1999 |accessdate=February 19, 2012 |newspaper=Salon}}</ref> McKinney and Henderson went to the Fireside Lounge and selected Shepard after he arrived. McKinney alleged that Shepard asked them for a ride home.<ref name=trutv/> | |||

| ===''The Book of Matt''=== | |||

| After befriending him, they took him to a remote area outside of ] where they robbed him, assaulted him severely, and tied him to a fence with a rope from McKinney's truck while Shepard pleaded for his life. Media reports often contained the graphic account of the pistol whipping and his fractured skull. It was reported that Shepard was beaten so brutally that his face was completely covered in blood, except where it had been partially washed clean by his tears.<ref>{{cite book |title=Losing Matt Shepard: life and politics in the aftermath of anti-gay murder |last=Loffreda |first=Beth |year=2000 |publisher=Columbia University Press |location=New York |isbn=0-231-11858-9 |url=http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/l/loffreda-shepard.html }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Chiasson |first=Lloyd |title=Illusive Shadows: Justice, Media, and Socially Significant American Trials |publisher=Praeger |date=November 30, 2003 |page=183 |isbn=978-0-275-97507-4 }}</ref> Both girlfriends also testified that neither McKinney nor Henderson were under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://homes.thedailycamera.com/extra/shepard/|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20080424091724/http://homes.thedailycamera.com/extra/shepard/|archivedate=2008-04-24|title=The Daily Camera:Matthew Shepard Murder|accessdate=2006-04-06}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://homes.thedailycamera.com/extra/shepard/29bshep.html|title=Girlfriend: McKinney told of killing|last=Black|first=Robert W.|work=The Daily Camera|date=October 29, 1999}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|The Book of Matt}} | |||

| ], the producer of the 2004 ''20/20'' segment, went on to write a book, '']'', which was published in September 2013.<ref name=Jimenez>{{cite book|title=]|publisher=Steerforth|author=Jimenez, Stephen|year=2013|isbn=978-1586422141}}</ref> The book said that Shepard and McKinney—the killer who inflicted the injuries—had been occasional sex partners and that Shepard was a methamphetamine dealer.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/12/stephen-jimenez-matthew-shepard_n_3914707.html|title=Matthew Shepard Murdered By Bisexual Lover And Drug Dealer, Stephen Jimenez Claims In New Book|work=Huffington Post|date=September 12, 2013|access-date=September 30, 2013|archive-date=September 16, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130916172842/http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/12/stephen-jimenez-matthew-shepard_n_3914707.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=jbfh/> Jimenez wrote that Fritzen told an interviewer "Matthew Shepard's sexual preference or sexual orientation certainly wasn't the motive in the homicide...".<ref name=Jimenez /> | |||

| Many commentators have criticized Jimenez's views on the attack by classifying them as being sensational and misleading.<ref name=jbfh>{{cite web|url=http://thinkprogress.org/alyssa/2013/10/18/2802871/book-matt-prove-size-stephen-jimenezs-ego|title='The Book Of Matt' Doesn't Prove Anything, Other Than The Size Of Stephen Jimenez's Ego|work=ThinkProgress|date=October 18, 2013|access-date=October 18, 2013|author=Rosenberg, Alyssa|archive-date=October 18, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131018161518/http://thinkprogress.org/alyssa/2013/10/18/2802871/book-matt-prove-size-stephen-jimenezs-ego/|url-status=live}}</ref> Some commentators, however, have spoken up to defend them.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.advocate.com/print-issue/current-issue/2013/09/13/have-we-got-matthew-shepard-all-wrong?page=0,0|title=Have We Got Matthew Shepard All Wrong?|last1=Hicklin|first1=Aaron|website=Advocate|date=September 13, 2013|access-date=March 1, 2014|archive-date=October 24, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131024135906/http://www.advocate.com/print-issue/current-issue/2013/09/13/have-we-got-matthew-shepard-all-wrong?page=0,0|url-status=live}}</ref> Some police that were involved in the investigation have criticized Jimenez's conclusions,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ebar.com/news/article.php?sec=news&article=69201|title=Shepard book stirs controversy|work=The Bay Area Reporter|date=October 24, 2013|last=Hemmelgarn|first=Seth|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141110042205/http://ebar.com/news/article.php?sec=news&article=69201|archive-date=November 10, 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://www.out.com/news-opinion/2014/11/24/book-matt-author-responds-media-matters-steve-jimenez |magazine=Out |date=November 24, 2014 |first=Stephen |last=Jiminez |title=Book of Matt Author Responds to Media Matters |access-date=October 12, 2018 |quote=two police officers, Dave O'Malley and Rob DeBree, have quarreled with some of the findings |archive-date=October 13, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181013014249/https://www.out.com/news-opinion/2014/11/24/book-matt-author-responds-media-matters-steve-jimenez |url-status=live }}</ref> while other police said that there was evidence that drugs were an important factor that led to the murder.<ref name="Bindel"/> | |||

| Henderson pleaded guilty on April 5, 1999 and agreed to testify against McKinney to avoid the ]; he received two consecutive ]s. The jury in McKinney's trial found him guilty of ]. As they began to deliberate on the ], Shepard's parents brokered a deal, resulting in McKinney receiving two consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole.<ref name=cart>{{cite news|last=Cart|first=Julie|title=Killer of Gay Student Is Spared Death Penalty; Courts: Matthew Shepard's father says life in prison shows 'mercy to someone who refused to show any mercy.'|date=November 5, 1999|work=]|page=A1}}</ref> | |||

| ==Anti-gay protests== | |||

| Henderson and McKinney were ] in the Wyoming State Penitentiary in ], later being transferred to other prisons because of overcrowding.<ref>{{cite news |first=Jean |last=Torkelson |title=Mother's mission: Matthew Shepard's death changes things |url=http://m.rockymountainnews.com/news/2008/oct/03/10-years-later-matthew-shepard-hasnt-been-forgotte/ |work=Rocky Mountain News |publisher=The E.W. Scripps Co. |date=3 October 2008 |accessdate=16 November 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| Members of the ], led by ], received national attention for picketing Shepard's funeral with signs bearing ] slogans, such as "Matt in Hell" and "God Hates Fags".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gaytoday.com/garchive/events/101498ev.htm|title=Top Story|publisher=Gay Today|access-date=January 3, 2012|archive-date=April 4, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120404163159/http://www.gaytoday.com/garchive/events/101498ev.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Church members also mounted anti-gay protests during the trials of Henderson and McKinney.<ref>{{cite web |title=Put the victim on trial? |last=Cullen |first=Dave |work=Salon |url=https://www.salon.com/2001/01/02/shepard |date=October 11, 1999 |access-date=November 27, 2017 |archive-date=December 1, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171201042752/https://www.salon.com/2001/01/02/shepard |url-status=live }}</ref> In response, ], one of Shepard's friends, organized a group that assembled in a circle around the Westboro Baptist Church protesters. The group wore white robes and gigantic wings (resembling ]s) that blocked the protesters. Despite this, Shepard's parents were able to hear the protesters shouting anti-gay remarks and comments directed toward them. The police intervened and created a human barrier between the two groups.<ref name="CNN-pleads"/> ] was founded by Patterson in April 1999.<ref name="CNN-pleads">{{cite news|title=Suspect pleads guilty in beating death of gay college student|url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9904/05/gay.attack.trail.02|date=April 5, 1999|access-date=January 18, 2007|publisher=CNN |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070102094210/http://www.cnn.com/US/9904/05/gay.attack.trail.02|archive-date=January 2, 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=The Whole World Was Watching|url=http://www.paraview.com/patterson/index.htm|access-date=January 18, 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061015183949/http://www.paraview.com/patterson/index.htm|archive-date=October 15, 2006|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ==Hate crime legislation== | |||

| {{Main|Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act}} | |||

| {{See also|Hate crime laws in the United States}} | |||

| ] greets Louvon Harris, left, Betty Byrd Boatner, right, both sisters of James Byrd, Jr., and ] at a reception commemorating the enactment of ]]] | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| Henderson and McKinney were not charged with a ], because no Wyoming criminal statute provided for such a charge.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www2.timesdispatch.com/lifestyles/2009/jun/13/i-hate0531_20090611-212807-ar-40471/ |title=Hate-crimes bill would expand federal jurisdiction |first=Emily |last=Kimball |work=] |date=June 13, 2009}}</ref> The nature of Shepard's murder led to requests for new legislation addressing hate crime, urged particularly by those who believed that Shepard was targeted on the basis of his sexual orientation.<ref>{{cite news|title=Mother of Hate-Crime Victim to Speak at Colby|author=]|date=March 7, 2006|url=http://www.colby.edu/news/detail/612/|accessdate=2006-04-06}} Press release.</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1009867|title=Open phones|accessdate=2006-04-06|work=]|publisher=]|date=October 12, 1998}} "Denounced nationwide as a hate crime" at 1:40 elapsed time.</ref> Under then ] federal law<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.htm|accessdate=2006-04-06|title=Investigative Programs: Civil Rights: Hate Crimes|publisher=]}}</ref> and ] state law,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.adl.org/99hatecrime/provisions.asp|accessdate=2006-04-06|title=Map of State Statutes|publisher=]}}</ref> crimes committed on the basis of sexual orientation were not prosecutable as hate crimes. | |||

| In the years following her son's death, Judy Shepard has worked as an advocate for ], particularly issues relating to gay youth.<ref name=Ring /> She was a main force behind the ], which she and her husband, Dennis, founded in December 1998.<ref name=Pilkington>{{cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/10/matthew-shepard-wyoming-gay-rights-laws |title=Fifteen years after Matthew Shepard's murder, Wyoming remains anti-gay |newspaper=The Guardian |date=October 10, 2013 |access-date=March 20, 2017 |first=Ed |last=Pilkington |archive-date=March 21, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170321172514/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/10/matthew-shepard-wyoming-gay-rights-laws |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Gay rights activist ] has said that to portray Shepard as a gay-bashing victim is to present an incomplete account of his victimization: "Keeping Matthew as the poster boy of gay-hate crime and ignoring the full tragedy of his story has been the agenda of many gay-movement leaders. Ignoring the tragedies of Matthew's life prior to his murder will do nothing to help other young men in our community who are sold for sex, ravaged by drugs, and generally exploited."<ref name="Bindel"/> | |||

| In the following session of the Wyoming Legislature, a bill was introduced defining certain attacks motivated by victim identity as hate crimes, however the measure failed on a 30-30 tie in the ].<ref>{{cite news|title=The "Hate State" Myth|last=Blanchard|first=Robert O.|url=http://reason.com/9905/fe.rb.the.shtml|accessdate=2006-04-06|date=May 1999|work=]|archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20060405031833/http://reason.com/9905/fe.rb.the.shtml |archivedate = April 5, 2006}}</ref> | |||

| In June 2019, Shepard was one of the inaugural 50 American "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes" inducted on the ] within the ] (SNM) in ]'s ].<ref name=":23">{{Cite web|url=https://www.metro.us/news/local-news/new-york/stonewall-inn-lgbtq-wall-honor|title=National LGBTQ Wall of Honor unveiled at Stonewall Inn|last=Glasses-Baker|first=Becca|date=June 27, 2019|website=www.metro.us|access-date=June 28, 2019|archive-date=June 28, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190628133313/https://www.metro.us/news/local-news/new-york/stonewall-inn-lgbtq-wall-honor|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="SDGLN">{{Cite web|url=https://sdgln.com/news/2019/06/19/national-lgbtq-wall-honor-be-unveiled-historic-stonewall-inn|title=National LGBTQ Wall of Honor to be unveiled at historic Stonewall Inn|last=Rawles|first=Timothy |date=June 19, 2019|website=San Diego Gay and Lesbian News|language=en|access-date=June 21, 2019|archive-date=June 21, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190621091646/https://sdgln.com/news/2019/06/19/national-lgbtq-wall-honor-be-unveiled-historic-stonewall-inn|url-status=live}}</ref> The SNM is the first ] dedicated to ] and ],<ref>{{Cite web|last=Laird|first=Cynthia|url=https://www.ebar.com/news/news//272833|title=Groups seek names for Stonewall 50 honor wall|website=The Bay Area Reporter / B.A.R. Inc.|language=en|access-date=May 24, 2019|archive-date=May 24, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190524021601/https://www.ebar.com/news/news//272833|url-status=live}}</ref> and the wall's unveiling was timed to take place during the ] of the ].<ref>{{Cite web|last=Sachet|first=Donna|url=http://sfbaytimes.com/stonewall-50/|title=Stonewall 50|date=April 3, 2019|website=San Francisco Bay Times|access-date=May 25, 2019|archive-date=May 25, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190525134357/http://sfbaytimes.com/stonewall-50/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| At the federal level, then-President ] renewed attempts to extend federal ] legislation to include ] individuals, women, and people with ].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://transcripts.cnn.com/2000/ALLPOLITICS/stories/09/13/hate.crimes/index.html|accessdate=2006-04-07|author=Barrett, Ted, and ]|title=President Clinton urges Congress to pass hate crimes bill: GOP aides predict legislation will pass House, but will not become law|publisher=CNN|date=September 13, 2000 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080526040218/http://transcripts.cnn.com/2000/ALLPOLITICS/stories/09/13/hate.crimes/index.html |archivedate = May 26, 2008}}</ref> These efforts were rejected by the ] in 1999.{{citation needed|date=September 2012}} In September 2000, both houses of ] passed such legislation; however it was stripped out in ].<ref>{{cite news|author=Office of House Democratic Leader ]|date=October 7, 2004|url=http://democraticleader.house.gov/press/releases.cfm?pressReleaseID=718|accessdate=2006-04-07|title=House Democrats Condemn GOP Rejection of Hate Crimes Legislation |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20060401180910/http://democraticleader.house.gov/press/releases.cfm?pressReleaseID=718 |archivedate = April 1, 2006}} Press release.</ref> | |||

| ===Hate crime legislation=== | |||

| On March 20, 2007, the ] ({{USBill|110|HR|1592}}) was introduced as federal bipartisan legislation in the ], sponsored by Democrat ] with 171 co-sponsors. Shepard's parents were present at the introduction ceremony. The bill passed the House of Representatives on May 3, 2007. Similar legislation passed in the ] on September 27, 2007<ref>Simon, R. , ], 2007-05-03. Retrieved on 2007-05-03.</ref> ({{USBill|110|S|1105}}), however then-] indicated he would ] the legislation if it reached his desk.<ref name="nyt">Stout, D. , ], 2007-05-03. Retrieved 2007-05-03.</ref> The amendment was dropped by the ] leadership because of opposition from conservative groups and President George Bush, and due to the measure being attached to a defense bill there was a lack of support from ] Democrats.<ref name="windy">{{cite news|url=http://www.windycitymediagroup.com/gay/lesbian/news/ARTICLE.php?AID=17078|title=Congress Drops Hate-Crimes Bill|first=Amy|last=Wooten|date=January 1, 2008|accessdate=2008-07-31|work=]}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act}} | |||

| {{See also|Hate crime laws in the United States}} | |||

| ] greets Louvon Harris, left, Betty Byrd Boatner, right, both sisters of ], and ] at a 2009 reception commemorating the enactment of ].]] | |||

| Requests for new legislation to address hate crimes gained momentum during coverage of the incident.<ref>{{cite news |author=Colby College |author-link=Colby College |date=March 7, 2006 |title=Mother of Hate-Crime Victim to Speak at Colby |url=http://www.colby.edu/news/detail/612 |url-status=dead |access-date=April 6, 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060911192640/http://www1.colby.edu/news/detail/612/ |archive-date=September 11, 2006}} Press release.</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1009867|title=Open phones|access-date=April 6, 2006|work=]|publisher=]|date=October 12, 1998|archive-date=March 17, 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080317004702/http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1009867|url-status=live}} "Denounced nationwide as a hate crime" at 1:40 elapsed time.</ref> Under existing ] federal law<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.htm|access-date=April 6, 2006|title=Investigative Programs: Civil Rights: Hate Crimes|publisher=]|archive-date=April 5, 2006|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060405063153/http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> and ] state law,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.adl.org/99hatecrime/provisions.asp|access-date=April 6, 2006|title=Map of State Statutes|publisher=]|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629023522/http://www.adl.org/99hatecrime/provisions.asp|archive-date=June 29, 2011}}</ref> crimes committed on the basis of sexual orientation could not be prosecuted as hate crimes. | |||

| On December 10, 2007, congressional powers attached bipartisan hate crimes legislation to a Department of Defense Authorization bill, though failed to get it passed. ], Speaker of the House, said she "is still committed to getting the Matthew Shepard Act passed." Pelosi planned to get the bill passed in early 2008<ref name="nyt2">, ], 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2007-12-11.</ref> though did not succeed in that plan. Following his election as President, ] stated that he was committed to passing the Act.<ref name="blade">{{cite news |first=Joshua |last=Lynsen |title=Obama renews commitment to gay issues |url=http://www.washblade.com/2008/6-13/news/national/12766.cfm |work=Washington Blade |publisher=Window Media LLC Productions |date=13 June 2008 |accessdate=16 November 2008 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080617231821/http://www.washblade.com/2008/6-13/news/national/12766.cfm |archivedate = June 17, 2008}}</ref> | |||

| A few hours after Shepard was discovered, his friends Walt Boulden and Alex Trout began to contact media organizations, claiming that Shepard had been assaulted because he was gay. According to prosecutor Cal Rerucha, "They were calling the County Attorney's office, they were calling the media and indicating Matthew Shepard is gay and we don't want the fact that he is gay to go unnoticed."<ref name="abcnews"/> Tina Labrie, a close friend of Shepard's, said " wanted to make a poster child or something for their cause".<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141027015110/http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/09/22/the-myths-of-matthew-shepard-s-infamous-death.html |date=October 27, 2014 }} '']'' (September 22, 2013)</ref> Boulden linked the attack to the absence of a Wyoming criminal statute providing for a hate crimes charge.<ref name="Bindel">{{Cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/26/the-truth-behind-americas-most-famous-gay-hate-murder-matthew-shepard |title=The truth behind America's most famous gay-hate murder |author=Julie Bindel |author-link=Julie Bindel |work=] |date=October 25, 2014 |access-date=September 10, 2018 |archive-date=May 10, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170510183927/https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/26/the-truth-behind-americas-most-famous-gay-hate-murder-matthew-shepard |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The U.S. House of Representatives debated expansion of hate crimes legislation on April 29, 2009. During the debate, Representative ] of ] called the "hate crime" labeling of Shepard's murder a "hoax". Shepard's mother was said to be in the House gallery when the congresswoman made this comment.<ref>{{cite web |last=Grim |first=Ryan |title=Virginia Foxx: Story of Matthew Shepard's Murder A "Hoax" |url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/04/29/virginia-foxx-story-of-ma_n_192971.html |date=April 29, 2009 |publisher=Huffington Post |accessdate=2009-04-29 }}</ref> Foxx later called her comments "a poor choice of words".<ref>{{cite web |title=Congresswoman calls gay death case a `hoax' |url=http://abclocal.go.com/wtvd/story?section=news/local&id=6788587 |accessdate=2009-04-29 }}</ref> The House passed the act, designated {{USBill|111|HR|1913}}, by a vote of 249 to 175.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/04/29/house-passes-hate-crimes-bill/|title=House Passes Hate-Crimes Bill|last=Stout|first=David|date=April 29, 2009|publisher=New York Times|accessdate=2009-04-30}}</ref> The bill was introduced in the Senate on April 28 by ], ], and a bipartisan coalition;<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.feminist.org/news/newsbyte/uswirestory.asp?id=11668 |title=Matthew Shepard Hate Crimes Prevention Act Introduced in Senate |publisher=Feminist.org |date=2009-04-29 |accessdate=2010-03-05}}</ref> it had 43 cosponsors as of June 17, 2009. The Matthew Shepard Act was adopted as an amendment to S.1390 by a vote of 63-28 on July 15, 2009.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_lists/roll_call_vote_cfm.cfm?congress=111&session=1&vote=00233|title=U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records Home > Votes > Roll Call Vote:|accessdate=2009-07-17}}</ref> On October 22, 2009, the act was passed by the Senate by a vote of 68-29.<ref name="hill">Roxana Tiron, "Senate OKs defense bill, 68-29," '']'', found at . Retrieved October 22, 2009.</ref> President Obama signed the measure into law on October 28, 2009.<ref name=WP20091023 >{{cite news |title=Senate passes measure that would protect gays |last=Pershing |first=Ben |date=23 October 2009 |newspaper=The Washington Post |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/10/22/AR2009102204689.html}}</ref><ref name=PinkJessica2009 >{{cite news |title=Mother of Matthew Shepard welcomes U.S. hate crimes bill |last=Geen |first=Jessica |date=October 28, 2009 |newspaper=Pink News |accessdate=2009-10-28 |url=http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2009/10/28/mother-of-matthew-shepard-welcomes-us-hate-crimes-bill}}</ref> | |||

| In the following session of the Wyoming Legislature, a bill was introduced that defined certain attacks motivated by a victim's sexual orientation as hate crimes. The measure failed on a 30–30 tie in the ].<ref>{{cite news|title=The 'Hate State' Myth|last=Blanchard|first=Robert O.|url=http://reason.com/9905/fe.rb.the.shtml|access-date=April 6, 2006|date=May 1999|work=]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060405031833/http://reason.com/9905/fe.rb.the.shtml|archive-date=April 5, 2006}}</ref><ref name=Pilkington /> | |||

| ==Public reaction and aftermath== | |||

| {{See also|Cultural depictions of Matthew Shepard}} | |||

| ]'' depicting the "Angel Action" taken to block ] and his protestors from view]] | |||

| President ] renewed attempts to extend federal ] legislation to include ] people, women, and people with ].<ref>{{cite news|last=Barrett|first=Ted|others=]|date=September 13, 2000|title=President Clinton urges Congress to pass hate crimes bill: GOP aides predict legislation will pass House, but will not become law|publisher=CNN|url=http://transcripts.cnn.com/2000/ALLPOLITICS/stories/09/13/hate.crimes/index.html|access-date=April 7, 2006|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080526040218/http://transcripts.cnn.com/2000/ALLPOLITICS/stories/09/13/hate.crimes/index.html|archive-date=May 26, 2008}}</ref> A Hate Crimes Prevention Act was introduced in both the ] and ] in November 1997, and reintroduced in March 1999, but was passed by only the Senate in July 1999.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.hrc.org/resources/hate-crimes-timeline |title=Hate Crimes Timeline |publisher=Human Rights Campaign |access-date=March 21, 2017 |archive-date=March 19, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170319072614/http://www.hrc.org/resources/hate-crimes-timeline |url-status=live }}</ref> In September 2000, both houses of ] passed such legislation; however, it was stripped out in ].<ref>{{cite news|author=Office of House Democratic Leader ]|date=October 7, 2004|url=http://democraticleader.house.gov/press/releases.cfm?pressReleaseID=718|access-date=April 7, 2006|title=House Democrats Condemn GOP Rejection of Hate Crimes Legislation|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060401180910/http://democraticleader.house.gov/press/releases.cfm?pressReleaseID=718|archive-date=April 1, 2006}} Press release.</ref> | |||

| ], a friend of Shepard, organized a group of individuals who assembled in a circle around the Westboro Baptist Church protest group, wearing white robes and gigantic wings (resembling ]s) that blocked the protesters. Police had to create a human barrier between the two protest groups.<ref name = "CNN-pleads"/> | |||

| On March 20, 2007, the ] ({{USBill|110|HR|1592}}) was introduced as federal bipartisan legislation in the ], sponsored by Democrat ] with 171 co-sponsors. It would amend the existing federal hate crimes definition and expand it to cover gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability, and require reporting by the FBI of those crimes included in the expansion. Shepard's parents attended the introduction ceremony. The bill passed the House of Representatives on May 3, 2007. Similar legislation passed in the ] on September 27, 2007<ref>{{cite news |author=Simon, R. |url=http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/nation/la-na-hate4may04,0,3438099.story |title=Bush threatens to veto expansion of hate-crime law |work=Los Angeles Times |date=May 3, 2007 |access-date=May 7, 2007 |archive-date=May 13, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070513092145/http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/nation/la-na-hate4may04,0,3438099.story |url-status=live }}</ref> ({{USBill|110|S|1105}}), however then-President ] indicated he would ] the legislation if it reached his desk.<ref>{{cite news|author=Stout, D.|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/04/washington/04hate.html|title=House Votes to Expand Hate Crime Protection|work=]|date=May 3, 2007|access-date=February 11, 2017|archive-date=April 29, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170429152657/http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/04/washington/04hate.html|url-status=live}}</ref> The ] leadership dropped the legislation in response to opposition from conservative groups and Bush, and because the measure was attached to a defense bill there was a lack of support from ] Democrats.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.windycitymediagroup.com/gay/lesbian/news/ARTICLE.php?AID=17078|title=Congress Drops Hate-Crimes Bill|first=Amy|last=Wooten|date=January 1, 2008|access-date=July 31, 2008|work=]|archive-date=June 8, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100608060501/http://www.windycitymediagroup.com/gay/lesbian/news/ARTICLE.php?AID=17078|url-status=live}}</ref> On December 10, 2007, congressional powers attached bipartisan hate crimes legislation to a Department of Defense Authorization bill, although it failed to pass. ], Speaker of the House, said she was "still committed to getting the Matthew Shepard Act passed". Pelosi planned to get the bill passed in early 2008<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180926090024/https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/10/opinion/10mon3.html |date=September 26, 2018 }}, ''New York Times'', December 10, 2007; retrieved December 11, 2007.</ref> although she did not succeed. Following his election as president, ] stated that he was committed to passing the act.<ref>{{cite news|first=Joshua|last=Lynsen|title=Obama renews commitment to gay issues|url=http://www.washblade.com/2008/6-13/news/national/12766.cfm|work=Washington Blade|publisher=Window Media LLC Productions|date=June 13, 2008|access-date=November 16, 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080617231821/http://www.washblade.com/2008/6-13/news/national/12766.cfm|archive-date=June 17, 2008}}</ref> | |||

| While the organization had no name in the initial demonstration, it has since been ascribed various titles, including 'Angels of Peace' and 'Angel Action'.<ref name = "CNN-pleads">{{cite news |title=Suspect pleads guilty in beating death of gay college student|url=http://www.cnn.com/US/9904/05/gay.attack.trail.02/|date=April 5, 1999|accessdate=2007-01-18|publisher=CNN |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20070102094210/http://www.cnn.com/US/9904/05/gay.attack.trail.02/ |archivedate = January 2, 2007}}</ref><ref name = "TWWWW">{{cite web|title=The Whole World Was Watching|url=http://www.paraview.com/patterson/index.htm|accessdate=2007-01-18}}</ref> The fence to which Shepard was tied and left to die became an impromptu shrine for visitors, who left notes, flowers, and other mementos. It has since been removed by the land owner. | |||

| The U.S. House of Representatives debated expansion of hate crimes legislation on April 29, 2009. During the debate, Representative ] of ] called the "hate crime" labeling of Shepard's murder a "hoax".<ref>{{cite news|last=Grim|first=Ryan|title=Virginia Foxx: Story of Matthew Shepard's Murder A "Hoax"|url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/04/29/virginia-foxx-story-of-ma_n_192971.html|date=April 29, 2009|work=Huffington Post|access-date=April 29, 2009|archive-date=August 5, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110805063843/http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/04/29/virginia-foxx-story-of-ma_n_192971.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Foxx later called her comments "a poor choice of words".<ref>{{cite web|title=Congresswoman calls gay death case a 'hoax'|url=https://abc11.com/archive/6788587/|access-date=April 29, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100905055218/http://abclocal.go.com/wtvd/story?section=news%2Flocal&id=6788587|archive-date=September 5, 2010|url-status=live}}</ref> The House passed the act, designated {{USBill|111|HR|1913}}, by a vote of 249 to 175.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/04/29/house-passes-hate-crimes-bill|title=House Passes Hate-Crimes Bill|last=Stout|first=David|date=April 29, 2009|newspaper=New York Times|access-date=April 30, 2009|archive-date=May 2, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090502084139/http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/04/29/house-passes-hate-crimes-bill/|url-status=live}}</ref> ], ], and a bipartisan coalition introduced the bill in the Senate on April 28;<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.feminist.org/news/newsbyte/uswirestory.asp?id=11668|title=Matthew Shepard Hate Crimes Prevention Act Introduced in Senate|publisher=Feminist.org|date=April 29, 2009|access-date=March 5, 2010|archive-date=June 6, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110606113023/http://www.feminist.org/news/newsbyte/uswirestory.asp?id=11668|url-status=live}}</ref> it had 43 cosponsors as of June 17, 2009. The Matthew Shepard Act was adopted as an amendment to S.1390 by a vote of 63–28 on July 15, 2009.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_lists/roll_call_vote_cfm.cfm?congress=111&session=1&vote=00233|title=U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records: Roll Call Vote|access-date=July 17, 2009|archive-date=July 21, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090721134830/http://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_lists/roll_call_vote_cfm.cfm?congress=111&session=1&vote=00233|url-status=live}}</ref> On October 22, 2009, the Senate passed the act by a vote of 68–29.<ref>Roxana Tiron, "Senate OKs defense bill, 68-29", '']'', found at ; retrieved October 22, 2009.</ref> President Obama signed the measure into law on October 28, 2009.<ref>{{cite news|title=Senate passes measure that would protect gays|last=Pershing|first=Ben|date=October 23, 2009|newspaper=The Washington Post|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/10/22/AR2009102204689.html|access-date=September 4, 2017|archive-date=April 9, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170409162056/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/10/22/AR2009102204689.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Mother of Matthew Shepard welcomes U.S. hate crimes bill|last=Geen|first=Jessica|date=October 28, 2009|newspaper=Pink News|access-date=October 28, 2009|url=http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2009/10/28/mother-of-matthew-shepard-welcomes-us-hate-crimes-bill|archive-date=November 2, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091102182629/http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2009/10/28/mother-of-matthew-shepard-welcomes-us-hate-crimes-bill/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The murder continued to attract public attention and media coverage long after the trial was over. In 2004, the ] program '']'' aired a controversial report quoting claims by McKinney, Henderson, and Kristen Price, the prosecutor and a lead investigator that the murder had not been motivated by Shepard's sexuality but rather was merely a drug-related robbery that had turned violent.<ref name="abcnews"/> Critics charged that the report, which featured interviews with Shepard's murderers, was ], misleading, and downplayed or ignored evidence of homophobia as a motivation for the crime.<ref>{{cite news |title=ABC News Revisits Student's Killing, and Angers Some Gays |author=Lee, Felicia R. |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9900E6DD123EF935A15752C1A9629C8B63&n=Top%2fReference%2fTimes%20Topics%2fPeople%2fS%2fShepard%2c%20Matthew&smid=pl-share |newspaper=The New York Times |date=26 November 2004 |accessdate=11 June 2013}}</ref><ref>{{Wayback|url=http://web.archive.org/web/20090514015646/http://www.glaad.org/matthewshepard2020 | |||

| | title=GLAAD - 10 Questions About ABC’S 20/20 Show on Matthew Shepard | date=20090514015646}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last= Charles |first= Casey |title= Critical Queer Studies: Law, Film, and Fiction in Contemporary American Culture | url= http://books.google.com/books?id=EwtNwyfhHcEC&pg=PT67&lpg=PT67&dq=%22matthew+shepard%22+%2220/20%22+controversial+OR+controversy&source=bl&ots=ejlf88s-OU&sig=vUoUJeGi-d5LFVNPQ-q62r9XDm8&hl=en&sa=X&ei=M8C2UdnECqq60QGctIDQAw&ved=0CCsQ6AEwBQ | publisher= Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. |year= 2012 |isbn= 978-1409444060}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=O'Donnell |first=M. |year= 2008|title= Gay-hate, journalism and compassionate questioning|journal=Asia Pacific Media Educator |issue=19 |pages=113-126 |url=http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1304&context=apme |accessdate=11 June 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ===Interment in Washington National Cathedral=== | |||

| Retired Laramie Police Chief Dave O'Malley stated that the murderers' claims were not credible, but the prosecutor in the case stated that there was ample evidence that drugs were at least a factor in the murder.<ref name=OMalley>{{cite web |last=Knittel |first=Shaun |url=http://www.sgn.org/sgnnews37_20/mobile/page1.cfm |title=The Matthew Shepard paradox: How one U.S. Representative opened hate's old wounds |accessdate=October 29, 2009 |work=sgn.org |publisher=Seattle Gay News }}</ref> Other coverage focused on how these more recent statements contradicted those made at and near the trial.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://journalism.nyu.edu/publishing/archives/recount/article/95/|work=Recount|publisher=]|title=Rewriting the Motives Behind Matthew Shepard’s Murder|accessdate=2007-05-06|date=December 8, 2004}}</ref> | |||

| On October 26, 2018, just over 20 years after his death, Shepard's ashes were interred at the crypt of ].<ref>{{cite news|title=Matthew Shepard Will Be Interred at the Washington National Cathedral, 20 Years After His Death|author=Fortin, Jacey|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/11/us/matthew-shepard-ashes-cathedral.html|newspaper=The New York Times|date=October 11, 2018|access-date=October 11, 2018|archive-date=October 11, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181011142032/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/11/us/matthew-shepard-ashes-cathedral.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.vox.com/2018/10/26/18027342/matthew-shepherd-gene-robinson-interring-lgbtq-christians|title=Bishop Robinson welcomes Matthew Shepard — and gay Christians — back to the church|work=]|first=Tara Isabella|last=Burton|date=October 26, 2018|access-date=October 26, 2018|archive-date=October 26, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181026232828/https://www.vox.com/2018/10/26/18027342/matthew-shepherd-gene-robinson-interring-lgbtq-christians|url-status=live}}</ref> The ceremony was presided over by the first openly gay ] bishop ], and the ] the Right Reverend ]. Music was performed by the ]; GenOUT; and ], which performed ]'s ''Considering Matthew Shepard''.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-45996040|title=Gay hate crime victim interred in capital|date=October 26, 2018|work=BBC News|access-date=October 26, 2018|language=en-GB|archive-date=October 26, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181026222509/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-45996040|url-status=live}}</ref> His was the first interment of the ashes of a national figure at the cathedral since ]'s 50 years earlier.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://chasingchurches.com/2018/10/13/matthew-shepard-and-the-history-of-the-interment-the-dead-in-washington-national-cathedral/|title=Matthew Shepard and the History of the Interment the Dead in Washington National Cathedral|last=Bains|first=Davd|date=October 13, 2018|website=Chasing Churches|access-date=October 20, 2018|archive-date=October 20, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181020094922/https://chasingchurches.com/2018/10/13/matthew-shepard-and-the-history-of-the-interment-the-dead-in-washington-national-cathedral/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In September 2013, ''The Book of Matt: Hidden Truths About the Murder of Matthew Shepard'' by Stephen Jimenez, the producer of the ''20/20'' segment, was published. The book revived and expanded upon claims by the author that Shepard's murder was at least partly drug-related and that, contrary to the generally accepted version of events, his sexual orientation was not a major motive for the crime. Additionally the author claimed that Shepard and at least one of his killers (McKinney) had been occasional sexual partners.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/12/stephen-jimenez-matthew-shepard_n_3914707.html | title=Matthew Shepard Murdered By Bisexual Lover And Drug Dealer, Stephen Jimenez Claims In New Book | publisher=Huffington Post | date=09-12-2013 | accessdate=30 September 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news | url=http://nypost.com/2013/09/21/new-book-questions-matthew-shepard-killing/ | title=New book questions Matthew Shepard killing | work=New York Post | date=09-21-2013 | accessdate=30 September 2013 | author=Smith, Kyle}}</ref> The claims by Jiminez have been widely criticized by several sources including Media Matters due to questionable and anonymous sources and a lack of any source who actually considered themselves close to Shepard or McKinney.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://mediamatters.org/blog/2013/10/02/debunking-stephen-jimenezs-effort-to-de-gay-mat/196229 | title=Debunking Stephen Jiminezs Effort to De-Gay Matthew Shepard's Murder | work=Media Matters | date=10-02-2013 | accessdate=2 October 2013 | author=Brinker, Luke}}</ref> | |||

| ===In popular culture=== | |||

| ] have written and recorded songs about the murder, including the ] song "]" on her 1999 album '']''. ]'s 2001 album '']'' included "American Triangle" (originally titled "American Tragedy"), a song about Shepard's murder. The American metal band ] also composed and recorded "And Sadness Will Sear" on their third album, '']'', in honor of Shepard and in protest of closed-mindedness and prejudice. | |||

| {{main|Cultural depictions of Matthew Shepard}} | |||