| Revision as of 19:25, 16 October 2013 editAustriacus (talk | contribs)4,217 edits →The movement: corr. date of photo.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:25, 6 October 2024 edit undo2601:8c3:8578:af40:2054:9f60:4c93:7d84 (talk) →The movement | ||

| (53 intermediate revisions by 38 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|19th century Italian art movement}} | |||

| ], a leading artist in the Macchiaioli movement |

], a leading artist in the Macchiaioli movement]] | ||

| The '''Macchiaioli''' ({{IPA |

The '''Macchiaioli''' ({{IPA|it|makkjaˈjɔːli}}) were a group of ] ] active in ] in the second half of the nineteenth century. They strayed from antiquated conventions taught by the Italian art academies, and did much of their painting outdoors in order to capture natural light, shade, and colour. This practice relates the Macchiaioli to the French ]s who came to prominence a few years later, although the Macchiaioli pursued somewhat different purposes. The most notable artists of this movement were ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | ||

| ==The movement== | ==The movement== | ||

| ] | ], '']'', 1881, Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Florence]] | ||

| ] c. |

] c. 1856]] | ||

| The movement |

The movement originated with a small group of artists, many of whom had been revolutionaries in the ]. In the late 1850s, the artists met regularly at the ] in Florence to discuss art and politics.<ref>Broude, p. 1</ref> These idealistic young men, dissatisfied with the art of the academies, shared a wish to reinvigorate Italian art by emulating the bold tonal structure they admired in such old masters as ], ] and ].<ref name=Broude3>Broude, p. 3</ref> In addition, they found inspiration in the paintings of their French contemporaries of the ] thanks to ] (referred to as the father of the Macchiaioli's technique by his friend Telemaco Signorini<ref>Steingräber, E., & Matteucci, G. 1984, p. 112.</ref>), who brought those influences to the Caffe' Michelangiolo after his trip to Paris for the ] in 1855. | ||

| ]: the Macchiaioli art-movement had one focus in the "school of Castiglioncello" (Etruscan Coast).]] | ]: the Macchiaioli art-movement had one focus in the "school of Castiglioncello" (Etruscan Coast).]] | ||

| The Macchiaioli's group believed that areas of light and shadow, or "]" (literally patches or spots) were the chief components of a work of art. Indeed, their revolution primarily consists in juxtaposing spots of different colors (even relatively large at times), in such a way to contrast light and shade. Such a representation of light becomes the main way of shaping the painted subject, whose finer details become irrelevant and often neglected. The word macchia was commonly used by Italian artists and critics in the nineteenth century to describe the sparkling quality of a drawing or painting, whether due to a sketchy and spontaneous execution or to the harmonious breadth of its overall effect.<ref>Broude, p. 4</ref> | |||

| In its early years the new movement was ridiculed. A hostile review published on November 3, 1862 in the journal ''Gazzetta del Popolo'' marks the first appearance in print of the term Macchiaioli.<ref name=Broude96>Broude, p. 96</ref> The term carried several connotations: it mockingly implied that the artists' finished works were no more than sketches, and recalled the phrase "darsi alla macchia", meaning, idiomatically, to hide in the bushes or scrubland. The artists did, in fact, paint much of their work in these wild areas. This sense of the name also identified the artists with outlaws, reflecting the |

In its early years the new movement was ridiculed. A hostile review published on November 3, 1862 in the journal '']'' marks the first appearance in print of the term Macchiaioli.<ref name=Broude96>Broude, p. 96</ref> The term carried several connotations: it mockingly implied that the artists' finished works were no more than sketches, and recalled the phrase "darsi alla macchia", meaning, idiomatically, to hide in the bushes or scrubland. The artists did, in fact, paint much of their work in these wild areas. This sense of the name also identified the artists with outlaws, reflecting the traditionalists' view that new school of artists was working outside the rules of art, according to the strict laws defining artistic expression at the time. | ||

| The Macchiaioli group represents the first example of an independent group of artists who revolutionized painting thanks to a technique essentially based on the investigation and representation of light. For this reason, they have often been compared to the Impressionists, whose movement started in Paris roughly fifteen years after the Macchiaioli. However, the Macchiaioli did not go as far as their younger French colleagues in the pursuit of optical effects. Erich Steingräber says that the Macchiaioli "declined to divide up their palette into the components of the colour-spectrum, and did not paint blue shadows. This is why their pictures lack the all-penetrating light that eclipses colours and contours and gives rise to the 'vibrism' peculiar to Impressionist painting. The independent identity of the individual figures is unimpaired."<ref>Steingräber & Matteucci, p. 17</ref> | |||

| ], ''Silvestro Lega painting at Riva al Mare'', 1866–67, Oil on panel, 12.5 x 21 cm.]] | |||

| When analyzing the comparison between the two groups, it has been often pointed out that the Macchiaioli did not benefit from the technological advancement of the (portable) paint tubes, which on the other hand were practically available later on to the Impressionists in France. As a result, to avoid their hand-made paint colors to dry out, the Macchiaioli could not follow the Impressionists' practice of finishing relatively large paintings entirely '']'', but rather they were limited to small sketches painted out-of-doors as the basis for works eventually finished in the studio.<ref>Broude, pp. 5–10</ref> As a matter of fact, sketches painted on relatively small board panels (often fitting into standard cigar boxes), and where the "macchia" technique is mostly exemplified, represent a sort of trademark of the Macchiaioli's movement. | |||

| The verdict that the Macchiaioli were "failed impressionists" has been countered by an alternative view which places the Macchiaioli in a category of their own, a decade or so ahead of the Parisian impressionists. This interpretation views the Macchiaioli as ], with their broad theories of painting capturing the essence of subsequent movements that would not see the light of day for another decade or more. In this view the Macchiaioli emerge as being very much embedded in their social fabric and context, literally fighting alongside ] on behalf of the ] and its ideals. As such, their works provide comments on various socio-political topics, including ], prisons and hospitals, and ], including the plight of war widows and life behind the lines.<ref>see Boime</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | Many of the artists of the Macchiaioli died in penury, achieving fame only towards the end of the 19th century. Today the work of the Macchiaioli is much better known in Italy than elsewhere; much of the work is held, outside the public record, in private collections there.<ref>Broude, pp. xxii, 10</ref> | ||

| In this regard, what emerges is a picture of the I Macchiaili as very much embedded in the social fabric and context, collaborators and fighters with Giuseppe Garibaldi and his famed garibaldini on behalf of the Risorgimento and its ideals. As such, their works comment on the various socio-political topics: Jewish Emancipation, Italian Feminism, Prisons and Hospitals, The Plight of War Widows, The Woman and their Role Behind the Lines, etc. These ideas are put forward in an important book, "The Art of the Macchia and the Risorgimento" by Albert Boime. | |||

| Other painters, such as ] and ] and ], were influenced by this movement, without being a full part of it.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Azzolini|first=Marcello|date=24 October 1956|title=Antonio Sartini al Circolo Artistico|journal=L'Unità}}</ref> | |||

| The Macchiaioli did not follow Monet's practice of finishing large paintings entirely '']'', but rather used small sketches painted out-of-doors as the basis for works finished in the studio.<ref>Broude, pp. 5–10</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | The Macchiaioli were the subject of an exhibition at the ] in Rome, October 11, 2007 – February 24, 2008, which traveled to the ] in Florence, March 19 – June 22, 2008. An exhibition in Venice, at the Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti showed the capolavori della collezione Mario Taragoni from March 8 - July 27, 2008. Another exhibition of the Macchiaioli was held at the Terme Tamerici in ], August 12, 2009 – March 18, 2010. The ] in Paris mounted an exhibition of the Macchiaioli April 10 – July 22, 2013. | ||

| ⚫ | Many of the artists of the Macchiaioli died in penury, |

||

| ⚫ | The Macchiaioli were the subject of an exhibition at the in Rome, October 11, 2007 – February 24, 2008, |

||

| ==Gallery== | ==Gallery== | ||

| <gallery widths=" |

<gallery widths="160px" heights="160px" perrow=6> | ||

| File:Giuseppe Abbati, The Tower of the Palazzo del Podestà.jpg|], ''The Tower of the Palazzo del Podestà'', 1865, oil on wood | |||

| File:Vito d'Ancona - Signora in bianco.jpg|Vito |

File:Vito d'Ancona - Signora in bianco.jpg|], ''Lady in white'', oil on canvas, Modern art gallery of Milan. | ||

| File:Giovanni Fattori 027.jpg|], ''La Rotonda di Palmieri'', 1866, oil on wood, Florence, Galleria d'Arte Moderna | |||

| File:Giovanni Fattori 019.jpg|Giovanni Fattori, ''Prince Amadeo wounded at Custoza'', 1870, oil on canvas | |||

| File:Silvestro Lega - il bindolo -1863.jpg|Silvestro Lega, ''il Bindolo'', 1863 | File:Silvestro Lega - il bindolo -1863.jpg|], ''il Bindolo'', 1863 | ||

| File:Lega Ragazza di Crespina.jpg|Silvestro Lega, '' |

File:Lega Ragazza di Crespina.jpg|Silvestro Lega, ''Girl of Crespina'' | ||

| File:Telemaco Signorini, Via Torta, Firenze, 1870 circa 16,6x11,3cm.jpg|Telemaco Signorini, ''Via Torta'', ca. 1870 | File:Telemaco Signorini, Via Torta, Firenze, 1870 circa 16,6x11,3cm.jpg|], ''Via Torta'', ca. 1870 | ||

| Telemaco Signorini, Il ghetto di Firenze, 1882, 95x65 cm.jpg|Telemaco Signorini, ''Ghetto of Florence'', 1882 | File:Telemaco Signorini, Il ghetto di Firenze, 1882, 95x65 cm.jpg|Telemaco Signorini, ''Ghetto of Florence'', 1882 | ||

| File:Borrani_Cucitrici.png|], ''Cucitrici di camicie rosse'', 1863 | |||

| File:Serafino de Tivoli - A Pasture - WGA22726.jpg|], ''Una pastura'', 1859 | |||

| File:Serafino de Tivoli Holzbrücke.jpg|Serafino De Tivoli, ''Il ponte di legno'', 1857-1859 | |||

| File:Cabianca Le monachine.jpg|], ''The Nuns'', 1861 | |||

| </gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| Line 45: | Line 50: | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| *Boime, Albert (1993). ''The Art of the Macchia and the Risorgimento''. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN |

*Boime, Albert (1993). ''The Art of the Macchia and the Risorgimento''. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. {{ISBN|0-226-06330-5}} | ||

| *Broude, Norma (1987). ''The Macchiaioli: Italian Painters of the Nineteenth Century''. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN |

*] (1987). ''The Macchiaioli: Italian Painters of the Nineteenth Century''. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. {{ISBN|0-300-03547-0}} | ||

| *Steingräber, E., & Matteucci, G. (1984). ''The Macchiaioli: Tuscan Painters of the Sunlight : March 14-April 20, 1984''. New York: Stair Sainty Matthiesen in association with Matthiesen, London. {{OCLC|70337478}} | *Steingräber, E., & Matteucci, G. (1984). ''The Macchiaioli: Tuscan Painters of the Sunlight : March 14-April 20, 1984''. New York: Stair Sainty Matthiesen in association with Matthiesen, London. {{OCLC|70337478}} | ||

| *Turner, J. (1996). '']''. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN |

*Turner, J. (1996). '']''. USA: Oxford University Press. {{ISBN|0-19-517068-7}} | ||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| * Piero Bargellini, ''Caffè Michelangiolo'', Firenze, Vallecchi Editore, 1944. | |||

| *Panconi, T. (1999). ''Antologia dei Macchiaioli, La trasformazione sociale e artica nella Toscana di metà 800''. Pisa (Italy): Pacini Editore. | *Panconi, T. (1999). ''Antologia dei Macchiaioli, La trasformazione sociale e artica nella Toscana di metà 800''. Pisa (Italy): Pacini Editore. | ||

| *Panconi, T. (2009). ''I Macchiaioli, Il Nuovo dopo la Macchia''. Pisa (Italy): Pacini Editore. ISBN |

*Panconi, T. (2009). ''I Macchiaioli, Il Nuovo dopo la Macchia''. Pisa (Italy): Pacini Editore. {{ISBN|978-88-6315-135-0}} | ||

| *Durbe, Dario (1978). ''I Macchiaioli''. Rome: DeLuca Editore. | *Durbe, Dario (1978). ''I Macchiaioli''. Rome: DeLuca Editore. | ||

| {{Western art movements}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:25, 6 October 2024

19th century Italian art movement

The Macchiaioli (Italian pronunciation: [makkjaˈjɔːli]) were a group of Italian painters active in Tuscany in the second half of the nineteenth century. They strayed from antiquated conventions taught by the Italian art academies, and did much of their painting outdoors in order to capture natural light, shade, and colour. This practice relates the Macchiaioli to the French Impressionists who came to prominence a few years later, although the Macchiaioli pursued somewhat different purposes. The most notable artists of this movement were Giuseppe Abbati, Cristiano Banti, Odoardo Borrani, Vincenzo Cabianca, Adriano Cecioni, Vito D'Ancona, Serafino De Tivoli, Giovanni Fattori, Raffaello Sernesi, Silvestro Lega, and Telemaco Signorini.

The movement

The movement originated with a small group of artists, many of whom had been revolutionaries in the uprisings of 1848. In the late 1850s, the artists met regularly at the Caffè Michelangiolo in Florence to discuss art and politics. These idealistic young men, dissatisfied with the art of the academies, shared a wish to reinvigorate Italian art by emulating the bold tonal structure they admired in such old masters as Rembrandt, Caravaggio and Tintoretto. In addition, they found inspiration in the paintings of their French contemporaries of the Barbizon school thanks to Serafino De Tivoli (referred to as the father of the Macchiaioli's technique by his friend Telemaco Signorini), who brought those influences to the Caffe' Michelangiolo after his trip to Paris for the Exposition Universelle in 1855.

The Macchiaioli's group believed that areas of light and shadow, or "macchie" (literally patches or spots) were the chief components of a work of art. Indeed, their revolution primarily consists in juxtaposing spots of different colors (even relatively large at times), in such a way to contrast light and shade. Such a representation of light becomes the main way of shaping the painted subject, whose finer details become irrelevant and often neglected. The word macchia was commonly used by Italian artists and critics in the nineteenth century to describe the sparkling quality of a drawing or painting, whether due to a sketchy and spontaneous execution or to the harmonious breadth of its overall effect.

In its early years the new movement was ridiculed. A hostile review published on November 3, 1862 in the journal Gazzetta del Popolo marks the first appearance in print of the term Macchiaioli. The term carried several connotations: it mockingly implied that the artists' finished works were no more than sketches, and recalled the phrase "darsi alla macchia", meaning, idiomatically, to hide in the bushes or scrubland. The artists did, in fact, paint much of their work in these wild areas. This sense of the name also identified the artists with outlaws, reflecting the traditionalists' view that new school of artists was working outside the rules of art, according to the strict laws defining artistic expression at the time.

The Macchiaioli group represents the first example of an independent group of artists who revolutionized painting thanks to a technique essentially based on the investigation and representation of light. For this reason, they have often been compared to the Impressionists, whose movement started in Paris roughly fifteen years after the Macchiaioli. However, the Macchiaioli did not go as far as their younger French colleagues in the pursuit of optical effects. Erich Steingräber says that the Macchiaioli "declined to divide up their palette into the components of the colour-spectrum, and did not paint blue shadows. This is why their pictures lack the all-penetrating light that eclipses colours and contours and gives rise to the 'vibrism' peculiar to Impressionist painting. The independent identity of the individual figures is unimpaired."

When analyzing the comparison between the two groups, it has been often pointed out that the Macchiaioli did not benefit from the technological advancement of the (portable) paint tubes, which on the other hand were practically available later on to the Impressionists in France. As a result, to avoid their hand-made paint colors to dry out, the Macchiaioli could not follow the Impressionists' practice of finishing relatively large paintings entirely en plein air, but rather they were limited to small sketches painted out-of-doors as the basis for works eventually finished in the studio. As a matter of fact, sketches painted on relatively small board panels (often fitting into standard cigar boxes), and where the "macchia" technique is mostly exemplified, represent a sort of trademark of the Macchiaioli's movement.

The verdict that the Macchiaioli were "failed impressionists" has been countered by an alternative view which places the Macchiaioli in a category of their own, a decade or so ahead of the Parisian impressionists. This interpretation views the Macchiaioli as early modernists, with their broad theories of painting capturing the essence of subsequent movements that would not see the light of day for another decade or more. In this view the Macchiaioli emerge as being very much embedded in their social fabric and context, literally fighting alongside Giuseppe Garibaldi on behalf of the Risorgimento and its ideals. As such, their works provide comments on various socio-political topics, including Jewish emancipation, prisons and hospitals, and women's conditions, including the plight of war widows and life behind the lines.

Many of the artists of the Macchiaioli died in penury, achieving fame only towards the end of the 19th century. Today the work of the Macchiaioli is much better known in Italy than elsewhere; much of the work is held, outside the public record, in private collections there.

Other painters, such as Luigi and Flavio Bertelli and Antonino Sartini, were influenced by this movement, without being a full part of it.

The Macchiaioli were the subject of an exhibition at the Chiostro del Bramante in Rome, October 11, 2007 – February 24, 2008, which traveled to the Villa Bardini in Florence, March 19 – June 22, 2008. An exhibition in Venice, at the Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti showed the capolavori della collezione Mario Taragoni from March 8 - July 27, 2008. Another exhibition of the Macchiaioli was held at the Terme Tamerici in Montecatini Terme, August 12, 2009 – March 18, 2010. The Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris mounted an exhibition of the Macchiaioli April 10 – July 22, 2013.

Gallery

-

Giuseppe Abbati, The Tower of the Palazzo del Podestà, 1865, oil on wood

Giuseppe Abbati, The Tower of the Palazzo del Podestà, 1865, oil on wood

-

Vito D'Ancona, Lady in white, oil on canvas, Modern art gallery of Milan.

Vito D'Ancona, Lady in white, oil on canvas, Modern art gallery of Milan.

-

Giovanni Fattori, La Rotonda di Palmieri, 1866, oil on wood, Florence, Galleria d'Arte Moderna

Giovanni Fattori, La Rotonda di Palmieri, 1866, oil on wood, Florence, Galleria d'Arte Moderna

-

Giovanni Fattori, Prince Amadeo wounded at Custoza, 1870, oil on canvas

Giovanni Fattori, Prince Amadeo wounded at Custoza, 1870, oil on canvas

-

Silvestro Lega, il Bindolo, 1863

Silvestro Lega, il Bindolo, 1863

-

Silvestro Lega, Girl of Crespina

Silvestro Lega, Girl of Crespina

-

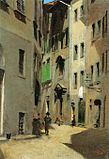

Telemaco Signorini, Via Torta, ca. 1870

Telemaco Signorini, Via Torta, ca. 1870

-

Telemaco Signorini, Ghetto of Florence, 1882

Telemaco Signorini, Ghetto of Florence, 1882

-

Odoardo Borrani, Cucitrici di camicie rosse, 1863

Odoardo Borrani, Cucitrici di camicie rosse, 1863

-

Serafino De Tivoli, Una pastura, 1859

Serafino De Tivoli, Una pastura, 1859

-

Serafino De Tivoli, Il ponte di legno, 1857-1859

Serafino De Tivoli, Il ponte di legno, 1857-1859

-

Vincenzo Cabianca, The Nuns, 1861

Vincenzo Cabianca, The Nuns, 1861

See also

Notes

- Broude, p. 1

- Broude, p. 3

- Steingräber, E., & Matteucci, G. 1984, p. 112.

- Broude, p. 4

- Broude, p. 96

- Steingräber & Matteucci, p. 17

- Broude, pp. 5–10

- see Boime

- Broude, pp. xxii, 10

- Azzolini, Marcello (24 October 1956). "Antonio Sartini al Circolo Artistico". L'Unità.

References

- Boime, Albert (1993). The Art of the Macchia and the Risorgimento. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-06330-5

- Broude, Norma (1987). The Macchiaioli: Italian Painters of the Nineteenth Century. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03547-0

- Steingräber, E., & Matteucci, G. (1984). The Macchiaioli: Tuscan Painters of the Sunlight : March 14-April 20, 1984. New York: Stair Sainty Matthiesen in association with Matthiesen, London. OCLC 70337478

- Turner, J. (1996). Grove Dictionary of Art. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517068-7

Further reading

- Piero Bargellini, Caffè Michelangiolo, Firenze, Vallecchi Editore, 1944.

- Panconi, T. (1999). Antologia dei Macchiaioli, La trasformazione sociale e artica nella Toscana di metà 800. Pisa (Italy): Pacini Editore.

- Panconi, T. (2009). I Macchiaioli, Il Nuovo dopo la Macchia. Pisa (Italy): Pacini Editore. ISBN 978-88-6315-135-0

- Durbe, Dario (1978). I Macchiaioli. Rome: DeLuca Editore.