| Revision as of 09:40, 10 June 2006 edit86.42.158.83 (talk) →Wire-strung harps (''clàrsach'' or ''cláirseach'')← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:08, 5 January 2025 edit undoAndy02124 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users9,954 edits Translate some Armenian citations although the Astghik Gevorgyan ref seems weak | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Plucked string instrument}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| The '''harp''' is a ] which has its strings positioned perpendicular to the ]. All harps have a neck, ] and ]. Some, known as ''frame harps'', also have a forepillar; those lacking the forepillar are referred to ''open harps''. Harp strings can be made of ] (sometimes ]-wound), ] (more commonly used than nylon), or ]. | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=October 2013}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox instrument | |||

| | name = Harp | |||

| | image = Harp.png | |||

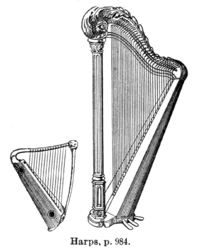

| | image_capt = A medieval harp (left) and a single-action pedal harp (right) | |||

| | background = string | |||

| | hornbostel_sachs = 322–5 | |||

| | hornbostel_sachs_desc = Composite ] sounded by the ] | |||

| | range = ]<div align=center>(])<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Black |first1=Dave |title=Essential Dictionary of Orchestration |last2=Gerou |first2=Tom |publisher=Alfred Publishing Co. |year=1998 |isbn=0-7390-0021-7}}</ref></div> | |||

| | related = * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (Chinese/Korean) | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (Baroque era) | |||

| * ] (Medieval era) | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''harp''' is a ] that has individual ] running at an angle to its ]; the strings are plucked with the fingers. Harps can be made and played in various ways, standing or sitting, and in orchestras or concerts. Its most common form is triangular in shape and made of wood. Some have multiple rows of strings and pedal attachments. | |||

| Various types of harps are found in ], ], ] and ], and a few parts of ]. In antiquity harps and the closely related ]s were very prominent in nearly all musical cultures, but they lost popularity in the early 19<sup>th</sup> century in Western music, being mainly played by women or as a minor ensemble member. There was no harp-exclusive museum until the North Italian harp building firm of Victor Salvi started one in 2005. | |||

| Ancient depictions of harps were recorded in ] (now ]), ] (now ]) and ], and later in ] and ]. By ] harps had spread across Europe. Harps were found across the Americas where it was a popular ] tradition in some areas. Distinct designs also emerged from the African continent. Harps have symbolic political traditions and are often used in logos, including in ]. | |||

| The ] (wind harp) and ] are technically not harps because their strings are not perpendicular to the soundboard. | |||

| ] | |||

| Historically, strings were made of ] (animal tendons).<ref name=Lawergrenharp>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Harp |encyclopedia=] |url=http://www.iranica.com/articles/harp |last=Lawergren |first=Bo |date=12 December 2003 |access-date=21 July 2011 |archive-date=15 August 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110815034237/http://www.iranica.com/articles/harp |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name=xiejin>{{Cite web |last=Xie Jin |title=Reflection upon Chinese Recently Unearthed Konghous in Xin Jiang Autonomous Region |url=https://musicology.cn/news/news_299.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304083704/https://musicology.cn/news/news_299.html |archive-date=4 March 2016 |publisher=Musicology Department, Shanghai Conservatory of Music, China |quote=The ]s in Xinjiang ...skin cover...one string has been found. It is made of ox tendon...}}</ref> Other materials have included ] (animal intestines),<ref name="gutplantfiber">{{Cite web |title=Ngombi (arched Harp) Fang/Kele people 19th century |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/502965 |website=Metropolitan Museum of Art}}</ref> plant fiber,<ref name=gutplantfiber /> braided hemp,<ref>{{Cite web |title=lyre; harp |url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/E_Af-4416 |website=The British Museum |quote=It has four (Hemp) strings and two hide thongs}}</ref> cotton cord,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Saùng-Gauk Burmese 19th century |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/502040 |website=Metropolitan Museum of Art}}</ref> silk,<ref name="si">{{Cite book |last=Williamson |first=Robert M. |url=https://archive.org/details/sciencestringins00ross |title=The Science of String Instruments |date=2010 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-4419-7110-4 |editor-last=Thomas D. Rossing |pages=–170 |url-access=limited}}</ref> nylon,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ngombi Tsogo mid-20th century |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/504481 |website=Metropolitan Museum of Art}}</ref> and wire.<ref>{{Cite web |title=ARCHED HARP OR BOW HARP |url=https://collections.ed.ac.uk/mimed/record/49737 |website=The University of Edinburgh, Musical Instruments Museums Edinburgh |quote=5 wire strings attached to lateral pegs in neck and attached at lower end to perforated wooden plaque anchored into the belly}}</ref> | |||

| ==Origins of the harp== | |||

| ]ian harp on display in a ] museum.]] | |||

| The harp's origins may lie in the sound of a plucked hunter's ] string. The oldest documented references to the harp are from ] in ] (see ]) and ] in ]. While the harp is mentioned in most translations of the ], ] being the most prominent musician, the Biblical "harp" was actually a ], a type of ] with 10 strings. Harps also appear in ancient epics, and in Egyptian wall paintings. This kind of harp, now known as the folk harp, continued to evolve in many different cultures all over the world. It may have developed independently in some places. | |||

| In pedal harp scores, ] and ] should be avoided whenever possible.{{Citation needed|date=July 2024}} | |||

| The lever harp came about in the second half of the 17<sup>th</sup> century to enable key changes while playing. The player manually turned a hook or lever against an individual string to raise the string's pitch by a ]. In the 1700s, a link mechanism was developed connecting these hooks with pedals, leading to the invention of the single-action pedal harp. Later, a second row of hooks was installed along the neck to allow for the double-action pedal harp, capable of raising the pitch of a string by either one or two semitones. With this final enhancement, the modern concert harp was born. | |||

| == History == | |||

| ==Types of harps, harp-playing and harp-building== | |||

| {{See also|Angular harp|Arched harp}} | |||

| ===Playing style of the European-derived harp=== | |||

| ] are considered to be the world's oldest surviving stringed instruments, {{nobr|3300-3100 BCE}}<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Harp |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Iranica |url=https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/harp}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] mosaic excavated at ] depicting player and a harp. Artifact is kept at The ].]] | |||

| ] while the ] king is hunting, ], Iran.]] | |||

| Most European-derived harps have a single row of strings with strings for each note of the C Major ] (over several ]s). Harpists can tell which strings they are playing because all F strings are black or blue and all C strings are red or orange. The instrument rests between the knees of the harpist and along their right shoulder. The Welsh triple harp and early Irish and Scottish harps, however, are traditionally placed on the left shoulder (in order to have it over the heart). The first four fingers of each hand are used to pluck the strings; the pinky fingers are too short and cannot reach the correct position without distorting the position of the other fingers, although on some folk harps with light tension, closely spaced strings, they may occasionally be used. Also, the pinky is not strong enough to pluck a string. Plucking with varying degrees of force creates ]. Depending on finger position, different tones can be produced: a fleshy pluck (near the middle of the first finger joint) will make a warm tone, while a pluck near the end of the finger will make a loud, bright sound. | |||

| Harps have been known since antiquity in Asia, Africa, and Europe, dating back at least as early as {{nobr|3000 {{sc|]}}.}} The instrument had great popularity in Europe during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, where it evolved into a wide range of variants with new technologies, and was disseminated to Europe's colonies, finding particular popularity in Latin America. | |||

| ===The pedal/concert harp=== | |||

| The '''pedal harp''', or '''concert harp''', is large and technically modern, designed for classical music and played solo, as part of chamber ensembles, and in symphony orchestras. It typically has six and a half octaves (46 or 47 strings), weighs about 80lb (36 kg), is approximately 6 ft (1.8 m) high, has a depth of 4 ft (1.2 m), and is 21.5 in (55 cm) wide at the bass end of the soundboard. The notes range from three octaves below middle C (or the D above) to three and a half octaves above, usually ending on G. The tension of the strings on the sound board is roughly equal to a ton (10 ]s). The lowest strings are made of copper or steel-wound nylon, the middle strings of gut, and the highest of nylon. | |||

| Although some ancient members of the harp family died out in the Near East and South Asia, descendants of early harps are still played in Myanmar and parts of Africa; other variants defunct in Europe and Asia have been used by ]ians in the modern era. | |||

| The pedal harp uses the mechanical action of ]s to change the ]es of the strings. There are seven pedals, one for each note, and each pedal is attached to a rod or cable within the column of the harp, which then connects with a mechanism within the neck. When a pedal is moved with the foot, small discs at the top of the harp rotate. The discs are studded with two pegs that pinch the string as they turn, shortening the vibrating length of the string. The pedal has three positions. In the top position no pegs are in contact with the string and all notes are ]. In the middle position the top wheel pinches the string, resulting in a natural. In the bottom position another wheel is turned, shortening the string again to create a ]. This mechanism is called the double-action pedal system, invented by ] in ]. Earlier pedal harps had a single-action mechanism that allowed strings to play sharpened notes. | |||

| ], {{nobr|{{circa| 2500 BCE }};}} ], Baghdad]] | |||

| === Origin === | |||

| ], ], and other manufacturers also make electric pedal harps. The ''']''' is a concert harp, with microphone pickups at the base of each string and an amplifier. The electric harp is a little heavier than an acoustic harp, but looks the same. | |||

| === |

==== West Asia and Egypt ==== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| ] ]]] | |||

| The earliest harps and lyres were found in ], {{nobr|3500 BCE,}}<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Galpin |first=F.W. |year=1929 |title=The Sumerian Harp of Ur, {{nobr|c. 3500 BCE}} |journal=Oxford Journal of Music and Letters |volume=X |issue=2 |pages=108–123 |doi=10.1093/ml/X.2.108}}</ref> and several harps were excavated from burial pits and royal tombs in ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Lyres: The Royal Tombs of Ur |url=http://sumerianshakespeare.com/509245/499545.html |publisher=SumerianShakespeare.com}}</ref> The oldest depictions of harps without a forepillar can be seen in the wall paintings of ]ian tombs in the ], which date from as early as {{nobr|3000 BCE.}}<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/paintings3.pdf?gathStatIcon=true |title=Ancient Egyptian Paintings |vauthors=Davis N |date=1986 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |veditors=Gardiner A |volume=3}}</ref> These murals show an ], an instrument that closely resembles the hunter's bow, without the pillar that we find in modern harps.<ref name="internationalharpmuseum">{{cite web |title=History of the Harp |url=http://www.internationalharpmuseum.org/visit/history.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160623222756/http://www.internationalharpmuseum.org/visit/history.html |archive-date=23 June 2016 |access-date=18 June 2016 |website=internationalharpmuseum.org |publisher=International Harp Museum}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- Unsourced image removed: ] --> | |||

| The '']'' flourished in Persia in many forms from its introduction, about {{nobr|4000 BCE,}} until the {{nobr|17th century {{sc|]}}.}} | |||

| ] era mosaic excavated at ]]] | |||

| Around {{nobr|1900 BCE,}} arched harps in the Iraq-Iran region were replaced by ]s with vertical or horizontal sound boxes.<ref name="Agnew2010">{{Cite conference |last=Agnew |first=Neville |date=28 June – 3 July 2004 |title=Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road |conference=The Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites |publisher=Getty Publications |publication-date=3 August 2010 |pages= ff |isbn=978-1-60606-013-1 |place=Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China}}</ref> The Kinnor ({{langx|he|{{script/Hebr|כִּנּוֹר}}}} ''kīnnōr'') was an ] musical instrument in the ] family, the first one to be mentioned in the ]. | |||

| The '''folk harp''' is small to medium-sized and usually designed for traditional music; it can be played solo or with small groups. It is prominent in Irish, Scottish and other Celtic cultures within traditional or folk music and as a social and political symbol. Often the folk harp is played by beginners who wish to move on to the pedal harp at a later stage, or by musicians who simply prefer the smaller size. | |||

| Its exact identification is unclear, but in the modern day it is generally translated as "harp" or "lyre",<ref name="Bromiley">{{cite book|author=Geoffrey W. Bromiley|title=The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia|date=February 1995|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Zkla5Gl_66oC&pg=PA442|accessdate=4 June 2013|publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|isbn=978-0-8028-3785-1|pages=442–}}</ref>{{rp|440}} and associated with a type of ] depicted in Israelite imagery, particularly the ] coins.<ref name="Bromiley"/> It has been referred to as the "national instrument" of the Jewish people,<ref name="PutnamUrban1968">{{cite book|author1=Nathanael D. Putnam|author2=Darrell E. Urban|author3=Horace Monroe Lewis|title=Three Dissertations on Ancient Instruments from Babylon to Bach|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rLDoAAAAIAAJ|accessdate=4 June 2013|year=1968|publisher=F. E. Olds}}</ref> and modern ]s have created reproduction lyres of the kinnor based on this imagery. | |||

| By the start of the Common Era, "robust, vertical, angular harps", which had become predominant in the Hellenistic world, were cherished in the ] court. In the last century of the ] period, angular harps were redesigned to make them as light as possible ("light, vertical, angular harps"); while they became more elegant, they lost their structural rigidity. At the height of the ] tradition of illustrated book production (1300–1600 CE), such light harps were still frequently depicted, although their use as musical instruments was reaching its end.<ref name="Yar-Shater2003">{{Cite book |last=Yar-Shater |first=Ehsan |title=Encyclopædia Iranica |date=2003 |publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul |isbn=978-0-933273-81-8 |pages=}}</ref> | |||

| The folk or lever harp ranges in size from two octaves to six octaves, and uses levers or blades to change pitch. The most common size has 34 strings: Two octaves below middle C and two and a half above (ending on A), although folk or lever harps can usually be found with anywhere from 19 to 40 strings. The strings are generally made of nylon, gut, carbon fiber or fluorcarbon or wrapped metal, and are plucked with the fingers using a similar technique to the pedal harp. | |||

| ==== Greece ==== | |||

| Folk harps with levers installed have a lever close to the top of each string; when it is engaged, it shortens the string so its pitch is raised a semitone, resulting in a sharped note if the string was a natural, or a natural note if the string was a flat. Lever harps are often tuned to the key of E-flat. Using this scheme, the major keys of E-flat, B-flat, F, C, G, D, A, and E can be reached by changing lever positions, rather than re-tuning any strings. Many smaller folk harps are tuned in C or F, and may have no levers, or levers on the F and C strings only, allowing a narrower range of keys. Blades and hooks perform the same function as levers, but use a different mechanism. The most common type of lever is either the Camac or Truitt lever although Loveland levers ares till used by some makers. Amplified (electro-acoustic) and solid body ] are produced by some harpmakers. | |||

| {{See also|Ancient Greek harps|Aegean civilization}} | |||

| ] seated harp player, ], Greece, {{nobr|2800-2700 BCE}}|241x241px]] | |||

| Marble sculptures of seated figures playing harps are known from the ] dating from {{nobr|2800-2700 BCE.}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/254587 |website=The Metropolitan Museum |title=Marble seated harp player}}</ref> | |||

| ==== South Asia ==== | |||

| === Wire-strung harps (''clàrsach'' or ''cláirseach'') === | |||

| {{See also|Yazh|Ancient veena}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] era paintings from ] show harp playing. An ] made of wooden brackets and metal strings is depicted on an ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Varadpande |first=Manohar Laxman |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SyxOHOCVcVkC&q=Varadpande |title=History of Indian Theatre |date=1987 |publisher=Abhinav Publications |isbn=9788170172215 |pages=14, 55, plate 18 |language=en}}</ref> The works of the Tamil ] describe the harp and its variants, as early as {{nobr|200 BCE.}}<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Vipulananda |year=1941 |title=The harps of ancient Tamil-land and the twenty-two srutis of Indian musical theory |url=http://www.southasiaarchive.com/Content/sarf.120137/211446/003 |journal=Calcutta Review |volume=LXXXI |issue=3}}</ref> Variants were described ranging from 14 to 17 strings, and the instrument used by wandering minstrels for accompaniment.<ref name="Zvelebil1992">{{Cite book |last=Zvelebil |first=Kamil |title=Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature |date=1992 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=90-04-09365-6 |pages=}}</ref> Iconographic evidence of the yaal appears in temple statues dated as early as {{nobr|600 BCE.}}<ref>{{Cite web |last1=Magazine |first1=Smithsonian |last2=Gershon |first2=Livia |title=Listen to the First Song Ever Recorded on This Ancient, Harp-Like Instrument |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/hear-sound-ancient-indian-instrument-180977426/ |access-date=28 September 2021 |website=Smithsonian Magazine |language=en}}</ref> One of the Sangam works, the ''Kallaadam'' recounts how the first ''yaaḻ'' harp was inspired by an archer's bow, when he heard the musical sound of its twang.{{citation needed|date=December 2014}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] wire-strung harp is called a '']'' in Scotland or a ''cláirseach'' in Ireland. The origins go back at least the first millennium. There are several stone carvings of harps from the 10<sup>th</sup> century, many of which have simple triangular shapes, generally with straight pillars, straight string arms or necks, and soundboxes. There is stone carving evidence that supports the theory that the harp was present Gaelic/] Scotland well before the 9<sup>th</sup> century.<ref>The Origins of the Clairsach or Irish Harp. Musical times, Vol. 53, No 828 (Feb 1912), pp 89-92.</ref>, | |||

| Another early South Asian harp was the ], not to be confused with the modern Indian ] which is a type of lute. Some Samudragupta gold coins show of the {{nobr|mid-4th century {{sc|CE}}}} show (presumably) the king ] himself playing the instrument.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yVNmAAAAMAAJ |title=The Journal of the Numismatic Society of India |date=2006 |publisher=Numismatic Society of India |pages=73–75}}{{full citation needed|date=June 2020|reason=article title; author; volume, issue}}</ref> The ancient veena survives today in Burma, in the form of the '']'' harp still played there.<ref name="Goyala1992">{{Cite book |last=Śrīrāma Goyala |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DkVuAAAAMAAJ |title=Reappraising Gupta History: For S.R. Goyal |date=1 August 1992 |publisher=Aditya Prakashan |isbn=978-81-85179-78-0 |page=237 |quote=... yazh resembles this old vina ... however it is the Burmese harp which seems to have been handed down in almost unchanged form since ancient times}}</ref> | |||

| The earliest descriptions of a European triangular framed harp i.e. harps with a fore pillar are found on 8th century Pictish stones.<ref>, Alison Latham (2002), The Oxford Companion to music, (Harpa) Oxford University Press p564.</ref>, .<ref>, The Anglo Saxon Harp, Spectrum, Vol. 71, No.2 (Apr., 1996), pp 290-320.</ref>, .<ref>, The Origins of the Clairsach or Irish Harp. Musical times, Vol. 53, No 828 (Feb 1912), pp 89-92..</ref>, Pictish harps were strung from horsehair. The instruments apparently spread south to the Anglo Saxons who commonly used gut strings and then west to the Gaels of the Highlands and to Ireland.<ref>, J.Keay & Julia Keay. (2000): Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland, Clarsach, p171. Harper Collins publishers.</ref> Historically the carvings were made in the period after the establishment of the Gaelic kingdom of ]. Despite the lack of direct evidence, some argue for a Gaelic influence. However, there are only thirteen depictions of any triangular chordophone from pre-11<sup>th</sup> century Europe, and all thirteen of them come from Scotland.<ref>, Alasdair Ross, "Pictish Chordophone Depictions", in ''Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies'', 36, 1998, esp. p. 41; Joan Rimmer, ''The Irish Harp'', (Cork, 1969) p. 17.<br>Also: Alasdair Ross discusses that all the Scottish harp figures were copied from foreign drawings and not from life, in 'Harps of Their Owne Sorte'? A Reassessment of Pictish Chordophone Depictions "Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies" 36, Winter 1998</ref> Moreover, the earliest Irish word for a harp is in fact ], a word which strongly suggests a Pictish provenance for the instrument.<ref>, J.Keay & Julia Keay. (2000): Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland, Clarsach, p171. Harper Collins publishers.</ref> | |||

| ==== East Asia ==== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Konghou}} | |||

| ], is a one of only three surviving medieval Gaelic harps. One resides at Trinity College Dublin and two of them survive from Perthshire, Scotland.]] | |||

| The harp was popular in ancient China and neighboring regions, though harps are largely extinct in East Asia in the modern day. The Chinese '']'' harp is documented as early as the ] {{nobr|(770–476 BCE),}} and became extinct during the ] {{nobr|(1368–1644 {{sc|CE}}).}}<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Konghou |url=https://www.britannica.com/art/konghou |access-date=2 October 2018 |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |edition=web}}</ref> A similar harp, the '']'' was played in ancient Korea, documented as early as the ] period {{nobr|(37 BCE – 686 {{sc|CE}}).}}<ref name=YunRichards2005>{{cite book |last1=Yun |first1=Hu-myŏng |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rRwaAQAAIAAJ |title=The love of Dunhuang |last2=Richards |first2=Kyungnyun K. |last3=Richards |first3=Steffen F. |date=2005 |publisher=Cross-Cultural Communications |isbn=978-0-89304-737-5}}</ref> | |||

| The harp was perhaps the most popular musical instrument used in both medieval Scotland and Ireland. | |||

| === Development === | |||

| {{quotation|Scotland, because of her affinity and intercourse , tries to imitate Ireland in music and strives in emulation. Ireland uses and delights in two instruments only, the harp namely, and the tympanum. Scotland uses three, the harp, the tympanum and the crowd. In the opinion, however, of many, Scotland has by now not only caught up on Ireland, her instructor, but already far outdistances her and excels her in musical skill. Therefore, people now look to that country as the fountain of the art.|]<ref>Gerald of Wales, ''Topographia Hibernica'', 94; tr. John O’ Meary, ''The History and Topography of Ireland'', (London, 1982).</ref>}} | |||

| ==== Europe ==== | |||

| The harp played by the Gaels of Scotland and Ireland between the 11<sup>th</sup> and 19<sup>th</sup> centuries was certainly wire-strung. The ] ] dates from the 11<sup>th</sup> century, and clearly shows a harper with a triangular framed harp including a "T-Section" in the pillar (or ''Lamhchrann'' in ]) indicating the bracing that would have been required to withstand the tension of a wire-strung harp. | |||

| {{See also|Origin of the harp in Europe|Medieval harp}} | |||

| ], Scotland, {{circa|800 CE}}]] | |||

| ] | |||

| While the angle and bow harps held popularity elsewhere, European harps favored the "pillar", a third structural member to support the far ends of the arch and soundbox.<ref name="Montagu 2002 564">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2002 |title=Harp |encyclopedia=] |publisher=] |location=London, UK |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780198662129/page/564 |editor-last=Latham |editor-first=Alison |page= |isbn=0-19-866212-2 |oclc=59376677 |author-last=Montagu |author-first=Jeremy}}</ref><ref name="Boenig_1996">{{Cite magazine |last=Boenig |first=Robert |date=April 1996 |title=The Anglo Saxon Harp |volume=71 |issue=2 |pages=290–320 |doi=10.2307/2865415 |jstor=2865415 |periodical=Spectrum}}</ref>{{rp|page=290}} A harp with a triangular three-part frame is depicted on 8th-century ] in Scotland<ref name="Montagu 2002 564" /><ref name=Boenig_1996 />{{rp|page=290}} and in manuscripts (e.g. the ]) from early 9th-century France.<ref name=Boenig_1996 /> The curve of the harp's neck is a result of the proportional shortening of the basic triangular form to keep the strings equidistant; if the strings were proportionately distant they would be farther apart. | |||

| By the ], the Gaelic language word ''clàrsach'' or ''cláirseach'' described a wire-strung harp with a massive carved soundbox, a reinforced curved pillar and a substantial neck, flanked with thick brass cheek bands. The wire-strung harp was played with the fingernails, and it produced a brilliant ringing sound. This is the style of harp on Irish coins and the Guinness label. Especially popular in 16<sup>th</sup> and 17<sup>th</sup> century English courts, it was played all over Europe and was usually called the ‘Irish’ harp. | |||

| ]) with buzzing bray pins]] | |||

| By the 18<sup>th</sup> century, harps of any sort had fallen out of use in Scotland and Ireland due to changing social, political and economic conditions. At the same time, new ] harps were being created on the Continent for a bourgeois audience; harps with multiple rows of strings and harps with sharping mechanisms for playing the fashionable music of the time. In the mid-19<sup>th</sup> century, a revival of all things Celtic brought attention back to Gaelic culture, sparking interest in native language and music. | |||

| As European harps evolved to play more complex music, a key consideration was some way to facilitate the quick changing of a string's pitch to be able to play more chromatic notes. By the ] period in Italy and Spain, more strings were added to allow for chromatic notes in more complex harps. In Germany in the second half of the 17th century, diatonic single-row harps were fitted with manually turned hooks that fretted individual strings to raise their pitch by a half step. In the 18th century, a link mechanism was developed connecting these hooks with pedals, leading to the invention of the single-action pedal harp. | |||

| The first primitive form of pedal harps was developed in the Tyrol region of Austria. Jacob Hochbrucker was the next to design an improved pedal mechanism around 1720, followed in succession by Krumpholtz, Naderman, and the Erard company, who came up with the double mechanism, in which a second row of hooks was installed along the neck, capable of raising the pitch of a string by either one or two half steps. While one course of European harps led to greater complexity, resulting largely in the modern pedal harp, other harping traditions maintained simpler diatonic instruments which survived and evolved into modern traditions. | |||

| ''The Irish and Highland Harps'' by Robert Bruce Armstrong is an excellent book describing these ancient harps. There is historical evidence that the types of wire used in these harps are ], ], ], and ]. Three pre-16<sup>th</sup> century examples survive today; the ] ] in ], and the ] and ]s, both in ]. | |||

| ==== Americas ==== | |||

| One of the largest and most complete collections of 17<sup>th</sup> century harp music is the work of ], a blind, itinerant Irish harper and composer. At least 220 of his compositions survive to this day. | |||

| In the Americas, harps are widely but sparsely distributed, except in certain regions where the harp traditions are very strong. Such areas include ], the ] region, ], and ]. They are derived from the ] harps that were brought from Spain during the colonial period.<ref name="Nicholls2013">{{Cite book |last=Nicholls |first=David |title=Whole World of Music: A Henry Cowell Symposium |date=19 December 2013 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-134-41946-3 |pages= ff}}</ref> Detailed features vary from place to place. | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] is that country's ], and has gained a worldwide reputation, with international influences alongside folk traditions. They have around 36 strings, are played with fingernails, and with a narrowing spacing and lower tension than modern Western harps, and have a wide and deep soundbox that tapers to the top.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HkIqAQAAIAAJ |title=Folk Harp Journal |date=1999 |volume=99}}</ref> | |||

| The harp is also found in Argentina,<ref name="Méndez2004">{{Cite book |last=Méndez, Marcela |title=Historia del arpa en la Argentina |date=1 January 2004 |publisher=Editorial de Entre Rios |isbn=978-950-686-137-7 |page=}}</ref> though in Uruguay it was largely displaced in religious music by the organ by the end of the 18th century.<ref name="Schechter1992">{{Cite book |last=Schechter |first=John Mendell |title=The Indispensable Harp: Historical Development, Modern Roles, Configurations, and Performance Practices in Ecuador and Latin America |date=1992 |publisher=Kent State University Press |isbn=978-0-87338-439-1 |page=}}</ref> The harp is historically found in Brazil, but mostly in the south of the country.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Ortiz |first=Alfredo Rolando |title=History of Latin American Harps |url=http://www.harpspectrum.org/folk/History_of_Latin_American_Harps.shtml |access-date=12 December 2014 |publisher=HarpSpectrum.org}}</ref> | |||

| ] was commissioned to notate the music played by the harpers at the ]. He published his first volume in 1796. He continued to collect the music of the cláirseach and published his second and third volumes in 1809 and 1840 respectively. A reprint of the 1840 edition is now available from ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (O'Hampsey) was the last of the harpers who played in the old style using the fingernails to pluck while the finger pads are used to damp. He also was one of the last to use the left hand in the treble. He was in his 90s at the 1792 festival and died in the beginning of the 19<sup>th</sup> century. He took the unbroken tradition of wire-strung harping with him to his grave. | |||

| The ] (Spanish/{{langx|qu|arpa}}), also known as the Peruvian harp, or indigenous harp, is widespread among peoples living in the highlands of the ]: ] and ], mainly in ], and also in ] and ]. It is relatively large, with a significantly increased volume of the resonator box, which gives basses a special richness. It usually accompanies love dances and songs, such as ].<ref name="Torres2013">{{Cite book |last=Torres |first=George |title=Encyclopedia of Latin American Popular Music |date=27 March 2013 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-0-313-08794-3 |page=}}</ref> One of the most famous performers on the Andean harp was ] (], ], Ecuador<ref>{{Cite web |title=Juan Cayambe |url=https://www.discogs.com/artist/3491434 |work=Discogs |language=en}}</ref>) | |||

| The {{lang|es|arpa jarocha}} is typically played while standing. In southern Mexico (Chiapas), there is a very different indigenous style of harp music.<ref name="Schechter1992 a">{{Cite book |last=Schechter |first=John Mendell |title=The Indispensable Harp: Historical development, modern roles, configurations, and performance practices in Ecuador and Latin America |date=1992 |publisher=Kent State University Press |isbn=978-0-87338-439-1 |page=}}</ref> | |||

| Since the 1970s, the tradition has been revived. ]'s "Renaissance de la harpe celtique" (perhaps the best-seller harp album in the world), using mainly the bronze strung harp, and his tours, has brought the instrument into the ears and the love of many people . ] has revived the ancient tradition and technic by playing the instrument as well as studying Bunting's original manuscripts in the library of Queens University, Belfast. Other notable players include Patrick Ball, Cynthia Cathcart, Alison Kinnaird, Bill Taylor, Siobhán Armstrong and others. | |||

| {{anchor|Venezuelan harps}} The harp arrived in Venezuela with Spanish colonists.<ref name=hc202007 /> There are two distinct traditions: the {{lang|es|arpa llanera}} ('harp of the ]’, or plains) and the {{lang|es|arpa central}} ('of the central area').<ref name="Briceño1999" /> By the 2020s, three types of harps are typically found:<ref name=hc202007 /> | |||

| As performers have become interested in the instrument, harp makers ("]") such as Jay Witcher, David Kortier, Ardival Harps, and others have begun building wire-strung harps. The traditional wire materials are used, however iron has been replaced by steel and the modern phosphor bronze has been added to the list. The phosphor bronze and brass are most commonly used. Steel tends to be very abrasive to the nails. Silver and gold are used to get high density materials into the bass courses of high quality clàrsachs to greatly improve their tone quality. In the period, no sharping devices were used. Harpers had to re-tune strings to change keys. This practice is reflected by most of the modern luthiers, yet some allow provisions for either levers or blades. | |||

| * the traditional '''llanera harp''', made of ] and has 32 strings, originally of the ], but in modern times are of nylon. It is used to accompany both dancers and singers playing ] music, a traditional form of Colombian-Venezuelan music, also known as llanera music.<ref name=hc202007 /> | |||

| * the {{lang|es|arpa central}} (also known as {{lang|es|arpa mirandina}} 'of ]’, and {{lang|es|arpa tuyera}} 'of the ]’) is strung with wire in the higher register.<ref name="Briceño1999">{{Cite book |last=Guerrero Briceño |first=Fernando F. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xWBaAAAAMAAJ |title=El arpa en Venezuela |date=1999 |publisher=FundArte, Alcaldía de Caracas |isbn=9789802533756}}</ref> | |||

| * the Venezuelan electric harp<ref name=hc202007>{{Cite journal |last=Reese |first=Allison |year=2021 |title=Venezuelan Virtuoso <!-- Used the printed journal article as a source in July 2021; but this link to the article exists, but is behind a paywall: |url=https://harpcolumn.com/blog/venezuelan-virtuoso/ --> |journal=Harp Column |volume=30 |issue=1 |pages=18–23}}</ref> | |||

| === |

==== Africa ==== | ||

| {{Main|African harps}} | |||

| A '''multi-course harp''' is a harp with more than one row of strings. A harp with only one row of strings is called a '''single-course harp.''' | |||

| ] man playing a bow harp]] | |||

| A number of types of harps are found in Africa, predominantly not of the three-sided frame-harp type found in Europe. A number of these, referred to generically as ]s, are bow or angle harps, which lack forepillars joining the neck to the body. | |||

| A number of harp-like instruments in Africa are not easily classified with European categories. Instruments like the West African '']'' and Mauritanian '']'' are sometimes labeled as "spike harp", "bridge harp", or ] since their construction includes a bridge which holds the strings laterally, vice vertically entering the soundboard.<ref name="Charry2000">{{Cite book |last=Charry, Eric S. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8F5r27VBBm0C&pg=PA76 |title=Mande Music: Traditional and modern music of the Maninka and Mandinka of western Africa |date=1 October 2000 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-10162-0 |pages=76–}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ==== Armenia ==== | |||

| A '''double harp''' consists of two rows of ] strings one on either side of the neck. These strings may run parallel to each other or may converge so the bottom ends of the strings are very close together. Either way, the strings that are next to each other are tuned to the same note. Double harps often have levers either on every string or on the most commonly sharped strings, for example C and F. Having two sets of strings allows the harpist's left and right hands to occupy the same range of notes without having both hands attempt to play the same string at the same time. It also allows for special effects such as repeating a note very quickly without stopping the sound from the previous note. | |||

| In ], the harp has been used since the fourth century BCE.{{citation needed|date=November 2023}} Common usages included weddings and funerals.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tahmizyan |first=Narine |date=1997 |lang=hy |script-title=hy:Երաժշտության տեսությունը հին Հայաստանում |trans-title=Music Theory in Ancient Armenia |publisher=Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR. |page=41}}</ref> The "horn beaker with a feast acene", found inside a vessel in ] and now preserved in the ], depicts a harp.{{sfn|Tahmizyan|1997|p=23}} Information about early medieval Armenian musical instruments has been found in Armenian translations of the Bible.<ref>{{cite book |last=Աճառյան |first=Հ․ |author-link=Hrachia Acharian |year=1926 |title=Հայէրեն արմատական բառարան |trans-title=Armenian root dictionary |location=Երևան |publisher=Yerevan University Publishing House |pages=390}}</ref>{{sfn|Tahmizyan|1997|pp=60–61}}<ref>{{cite journal |last=Harutyunyan |first=Gayane |year=2020 |lang=hy |script-title=hy:Հայկական տավիղներ |trans-title=Armenian Harps |journal=Երաժշտական Հայաստան }}</ref> In the past, the harp was played in the royal residences, in the royal recreation rooms. Sometimes not only the royal musicians, but the kings themselves played the instrument. Of course, in the past, harps did not have the sound capabilities that they have today, but the evidence that Armenians had a harp is well established | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| A ''']''' features three rows of parallel strings, two outer rows of ] strings, and a center row of ] strings. To play a sharp, the harpist reaches in between the strings in either outer row and plucks the center row string. Like the double harp, the two outer rows of strings are tuned the same, but the triple harp has no levers. This harp originated in ] in the 16<sup>th</sup> century as a low headed instrument, and towards the end of 1600s it arrived in ] where it developed a high head and larger size. It established itself as part of Welsh tradition and became known as the '''Welsh harp''' (''telyn deires'', "three-row harp"). The traditional design has all of the strings strung from the left side of the neck, but modern neck designs have the two outer rows of strings strung from opposite sides of the neck to greatly reduce the tendency for the neck to roll over to the left. | |||

| Տավիղ եղջերեգավաթի վրա, Էրեբունու թանգարան.jpg|Harp depicted on an Armenian horn beaker, ] | |||

| Արքայական ծագում ունեցող տավղահար.jpg|An Armenian royal harpist | |||

| Տավիղ միջնադարյան արծաթե գավաթի վրա.jpg|A harp on a medieval Armenian silver cup | |||

| Տավիղ, Էրեբունու թանգարան.jpg|], ] | |||

| File:Group of Musicians,, XVIth or XVIIth century.jpg|Armenian manuscript showing musicians, including harper. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| Armenians have had the instrument of harp since ancient times and used it in their everyday life, at weddings and burials. According to YSC professor, scholar of Middle Ages, doctor of Arts N. Tahmizyan, many musical instruments kept their pre-Christian form; among them is the harp, which was played not just at ceremonies. The instrument was performed by solo performers as well as with the accompaniment of other instruments. | |||

| ] | |||

| The Armenian translation of the Bible gives a lot of information about early medieval Armenian musical instruments. The translators of the Bible use the name harp among other quite popular musical instruments. In Armenian a verb has been formed from the name of the instrument: տաւղել which means to play the harp. The word has two meanings the second of which is stringed musical instrument which has the form of a triangular frame and this corresponds to the description of the musical instrument in Genesis 4:21 where it states | |||

| The ''']''' consists of one row of diatonically tuned strings and another row of chromatic notes. These strings cross approximately in the middle of the string without touching. Traditionally the diatonic row runs from the right (as seen by someone sitting at the harp) side of the neck to the left side of the sound board. The chromatic row runs from the left of the neck to the right of the sound board. The diatonic row has the normal string coloration for a harp, but the chromatic row may be black. The chromatic row is not a full set of strings. It is missing the strings between the Es and Fs in the diatonic row and between the Bs and Cs in the diatonic row. In this respect it is much like a ]. The diatonic row corresponds to the white keys and the chromatic row to the black keys. Playing each string in succession results in a complete chromatic scale. | |||

| : «Եւ նորա եղբօր անունը Յոբալ էր, որ բոլոր տավղահարների եւ սրնգահարների հայրն եղաւ»։ | |||

| Other uses of the word can be found in one of the songs of Grigor Narekatsi, a 10th century Armenian monk, medieval writer, and founder of Armenian Renaissance literature. The song is called ''Song of Vardavar'': | |||

| ==Harp technique== | |||

| : Քրքում վակասիր պտուղն | |||

| Harp playing uses all of the fingers except for the pinky, which is generally too short and weak to effectively pluck a string. In order to make notation of fingerings easier, each finger is given a number, "1" for the thumb, "2" for the index finger, "3" for the middle finger, and "4" for the ring finger. Most types of harp only require use of the hands. The exception is the pedal (concert) harp, where the harpist pushes the pedals with his or her feet. | |||

| : սնանէր խուռն տերևով. | |||

| : Տերևն տաւիղ տուողին | |||

| : զոր երգէր Դաւիթ հրաշալին: | |||

| ::: (Տաղ Վարդավառի) | |||

| Evidence for the instrument’s Armenian origin is the horn beaker with a feasting scene, kept at the ]: The beaker was found buried inside a large container, in the district of ] next to ] in 1968 during construction work. The calf horn beaker has pictures of people depicted on it, including a harpist: It depicts a man and three women participating at a feast; a third female is shown sitting on a chair holding a harp in her hands. This find indicates that the instrument in Armenia had its Armenian name in {{nobr|4th century BCE.}} Tahmizyan also writes about this horn beaker in his book. This find is evidence that Armenians knew and even enjoyed playing the harp in {{nobr|4th century BCE.}} | |||

| There are two main methods of classical harp technique in the United States: the French method (associated in the United States with the French-American harpist ]) and the Salzedo method, developed by ]. Neither method has a definite majority among harpists, but the issue of which is better is sometimes a source of friction and debate. The distinguishing features of the Salzedo method are the encouragement of expressive gestures, elbows remain parallel to the ground, wrists are comparatively still, and neither arm ever touches the soundboard. The Salzedo method also places great emphasis on specific fingerings. The French method advocates lowered elbows, fluid wrists, and the right arm resting lightly on the soundboard. In both methods, the shoulders, neck, and back are relaxed. Some harpists combine the two methods into the technique that works best for them. | |||

| On the famous Armenian Cilician silver beaker a man is painted surrounded with his wife and animals. | |||

| On the wire strung clarsach, a thumb under technique is also used. | |||

| Formerly the harp was played in royal castles. Sometimes not only musicians but also kings played the instrument. Of course, in the past harps did not have the sound range they have today but it is a fact that Armenians had the harp. | |||

| As in all baroque instrumental techniques, the underlying principle is that of strong and weak articulation. The player only uses three fingers of each hand, and the thumb moves under the other fingers, rather than being held very high as in modern harp technique. The thumb and third fingers are "strong" fingers and the second finger is a "weak" finger. Scales are fingered with alternating strong and weak fingers - that is, a scale fingering could be either 1 2 1 2 1 2 or 3 2 3 2 3 2. In contrast, classical harp technique uses a fingering of 4 3 2 1 4 3 2 1 going up and 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 going down. | |||

| Pictures of the harp can be found in ''People and Everyday Life'' ({{harvtxt|Yerevan|1978}}) scientific work of Astghik Gevorgyan, a researcher at Matenadaran, the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, Candidate in Arts. In her work pictures of the instrument can be found. In the first picture the man is playing the harp which is on his knees.{{full citation|date=October 2024}} | |||

| In the second picture the harp is played by a man who has a crown on his head, from which we may conclude that the musician has royal status. His harp is bigger and leans on the floor. | |||

| Another approach to "thumb under" technique as described above is to place the thumb so that it passes over the second finger, rather than under it. There is equal evidence for both thumb over and thumb under playing techniques on historical harps. | |||

| Not only did Armenians play the instrument but also they created songs about it. Kh. Avetisyan and V. Harutyunyan wrote a song called ''My Sweet Harp'' which was quite popular.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| This analysis and researches with the historical and archaeological evidence leads to the conclusion that the harp existed and was widely used in Armenians’ everyday lives, including royal families. The instrument’s popularity has grown during the years and the harp has become an instrument that represents the emotional inner world of the Armenians.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| In this second approach it is important to note that the fingers are placed on the strings an equal distance up the string from the soundboard. This may be as little as 5-8 inches on very lightly strung harps. If you begin by making a circle with your thumb and second finger, placing both the thumb and the second finger on the same string, open your thumb and place your thumb on the string above, also placing the third (and fourth – if you choose to use it) on the neighbouring strings below the second finger. The fingertips placed on the strings should loosely form a straight line parallel to the soundboard of the harp. | |||

| ==== South Asia ==== | |||

| As you play each finger, the aim is to roll the string over the end of your finger as you release it rather than pulling the string into your hand. This should require very little finger action to produce a warm and well rounded sound. Each finger produces a subtly different tone articulation. When playing scales down the harp, after playing the thumb it passes just over the second finger onto the string below, with the second finger falling onto the string below the thumb after releasing its note. Otherwise, as with thumb under technique, all scales are played alternating strong and weak fingerings. | |||

| In India, the B''in-Baia'' harp survives about the ] people of ].<ref name="ShepherdHorn2003">{{Cite book |last1=Shepherd |first1=John |title=Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World |last2=Horn |first2=David |last3=Laing |first3=Dave |last4=Oliver |first4=Paul |last5=Wicke |first5=Peter |date=8 May 2003 |publisher=A&C Black |isbn=978-1-84714-472-0 |volume=Part 1 Performance and Production |pages= ff |author-link5=Peter Wicke}}</ref> The ] has been part of ] musical tradition for many years.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Alvad |first=Thomas |date=October 1954 |title=The Kafir Harp |journal=Man |publisher=Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland |volume=54 |pages=151–154 |doi=10.2307/2795578 |jstor=2795578 |id=233}}</ref> | |||

| == |

==== East Asia ==== | ||

| ] | |||

| In ], there are ], ], ], and ] harps. They are derived from the ] harps that were brought from ] during the colonial period: wide on the bottom and narrow at the top, with perfect balance when being played but unable to stand independently for lack of a base. The Paraguayan harp is the most popular, and is Paraguay's national instrument. It has about 36 strings with narrower spacing and lighter tension than other harps, and so has a slightly (four to five notes) lower pitch. It does not necessarily have the same string coloration as the other harps. For example, some Paraguayan harps may have red B's and blue E's instead of red C's and blue F's. This harp is also played mostly with the fingernails. | |||

| The harp largely became extinct in East Asia by the 17th century; around the year 1000, harps like the '']'' began to replace prior{{clarify|date=December 2014}} harps.<ref name="Agnew2010 a">{{Cite conference |last=Neville Agnew |date=28 June – 3 July 2004 |title=Conservation of ancient sites on the Silk Road |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=n8YAyXzJE2IC&pg=PA121 |conference=The Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites |publisher=Getty Publications |publication-date=3 August 2010 |pages=121ff |isbn=978-1-60606-013-1 |place=Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China}}</ref> A few examples survived to the modern era, particularly ]'s '']-gauk'', which is considered the national instrument in that country. Though the ancient Chinese '']'' has not been directly resurrected, the name has been revived and applied to a modern newly invented instrument based on the Western classical harp, but with the strings doubled back to form two notes per string, allowing advanced techniques such as note-bending.{{citation needed|date=December 2014}} | |||

| ], Japan]] | |||

| All of Africa's harps are open harps because they lack the forepillar. With the exception of ]'s ], which is a true harp, most West African harps, such as the ], are technically classified as ]s because of their two rows of strings which are strung parallel to each other but perpendicular to the soundboard. | |||

| == Modern European and American harps == | |||

| In ], there are very few harps today, though the instrument was popular in ancient times; in that continent, ]s such as ]'s ] and ]'s ] predominate. However, a few harps exist, the most notable being ]'s ], which is considered the national instrument in that country. The Chinese ], which died out, is being revived in a modernized form. ] had a harp called the ] that has also fallen out of use. | |||

| === Concert harp === | |||

| There are no harps indigenous to ] or the ]. | |||

| {{Main|Pedal harp}} | |||

| ] playing the harp]] | |||

| The ''concert'' harp is a technologically advanced instrument, particularly distinguished by its use of pedals, foot-controlled levers which can alter the pitch of given strings, making it ] and thus able to play a wide body of classical repertoire. The pedal harp contains seven pedals that each affect the tuning of all strings of one ]. The pedals, from left to right, are D, C, B on the left side and E, F, G, A on the right. Pedals were first introduced in 1697 by Jakob Hochbrucker of Bavaria.<ref name="Stanley1997">{{Cite book |last=Stanley |first=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qnrZAAAAMAAJ |title=Classical Music: An introduction to Classical music through the great composers & their masterworks |date=1 May 1997 |publisher=Reader's Digest Association |isbn=978-0-89577-947-2 |page=24}}</ref> In 1811 these were upgraded to the "double action" pedal system patented by Sébastien Erard.<ref>{{Cite web |last=de Vale |first=Sue Carole |title=Harp |url=http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/45738pg5 |url-access=subscription |access-date=27 December 2020 |website=Oxford Music Online |series=Oxford Music Online / Grove Music Online |publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> | |||

| ] would run around performing zany slapstick pantomime comedy with his brothers, then sit down to play beautiful music on the concert harp.]] | |||

| == The harp in music == | |||

| The addition of pedals broadened the harp's abilities, allowing its gradual entry into the classical orchestra, largely beginning in the 19th century. The harp played little or no role in early classical music (being used only a handful of times by major composers such as Mozart and Beethoven), and its use by ] in his Symphony in D minor (1888) was described as "revolutionary" despite the harp having seen some prior use in orchestral music.<ref name=Mar1983>{{cite book |last=del Mar |first=Norman |author-link=Norman Del Mar |title=Anatomy of the Orchestra |year=1983 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-05062-4 |pages= ff }}</ref> In the 20th century, the pedal harp found use outside of classical music, entering musical comedy films in 1929 with ], jazz with ] in 1934,<ref>{{cite web |title=Casper Reardon |url=https://www.allmusic.com/artist/casper-reardon-mn0001839999 |access-date=19 December 2019 |series=Biography & History |website=AllMusic |lang=en-us}}</ref> ] 1967 single "]", and several works by ] which featured harpist ]. In the early 1980s, Swiss harpist ] exposed the concert harp to large new audiences with his popular new age/jazz albums and concert performances.<ref>{{Cite web |date=18 April 2008 |title=A Portrait of Andreas Vollenweider |url=https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/a-portrait-of-andreas-vollenweider-/6596504 |access-date=30 January 2020 |website=SWI swissinfo.ch |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=1 October 1985 |title=New Sounds: Andreas Vollenweider |url=https://www.spin.com/2019/10/new-sounds-andreas-vollenweider/ |access-date=30 January 2020 |website=Spin (magazine) |ref=Spin Oct. 1985 Vollenweider}}</ref> | |||

| The harp is used sparingly in most classical music, usually for special effects such as the ], ]s, and ]. Italian and German ] uses harp for romantic arias and dances, an example of which is Musetta's Waltz from ''].'' French composers such as ] and ] composed harp concertos and chamber music widely played today. In the 19<sup>th</sup> century, the French composer and harpist ] composed hundreds of pieces of all kinds (opera transcriptions, chamber music, concertos, operas, harp methods). ] and ] have composed many lesser-known solo pieces and chamber music. Modern composers utilize the harp frequently because the pedals on a concert harp allow many sorts of non-diatonic scales and strange accidentals to be played (although some modern pieces call for impractical pedal manipulations). | |||

| === Folk, lever, and Celtic instruments === | |||

| See ] for the names of some notable pieces from the classical repertoire. | |||

| {{Main|Celtic harp}} | |||

| ] ] playing a ]]] | |||

| ]" (''Clàrsach na Banrìgh Màiri'') preserved in the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh. It is one of three surviving Insular Celtic medieval harps, which serve as protypes for "celtic harps".]] | |||

| In the modern era, there is a family of mid-size harps, generally with nylon strings, and optionally with partial or full levers but without pedals. They range from two to six octaves, and are plucked with the fingers, largely using the same techniques used for playing orchestral harps. Though these harps evoke ties to historical European harps, their specifics are modern, and they are frequently referred to broadly as "''Celtic harps''" due to their region of revival and popular association, or more generically as "''folk harps''" due to their use in non-classical music, or as "''lever harps''" to contrast their modifying mechanism with the larger pedal harp.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bouchaud |first=Dominig |title=Is "Celtic" a myth? The lever harp in Brittany |url=http://www.harpblog.info/en/2016/01/is-celtic-a-myth-the-lever-harp-in-brittany/ |journal=Harp Blog}}</ref> | |||

| ] {{circa|1892}}]] | |||

| There have been harpists active in ] and ], including: | |||

| The modern Celtic harp began to appear in the early 19th century in Ireland, shortly after all the last generation of harpers had all died-out, breaking the continuity of musical training between the earlier native Gaelic harping tradition and the revival of Celtic harp playing as part of the later ]. | |||

| *] | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ], a pedal harp maker in Dublin, developed a new type of harp which had gut strings and semitone mechanisms like a reduced version of a single-action pedal harp; it was small and curved like the historical ''cláirseach'' or Irish harp, but its strings were of gut and the soundbox was much lighter.<ref>{{cite book |last=Rimmer |first=Joan |date=1977 |title=The Irish Harp |publisher=Mercier Press for the Cultural Relations Committee |page=67 |url= }}</ref> In the 1890s a similar new harp was also developed in Scotland as part of the ].<ref>Collinson, Francis (1983). ''The Bagpipe, Fiddle and Harp''. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966; reprinted by Lang Syne Publishers Ltd., {{ISBN|0946264481}}, {{ISBN|978-0946264483}}</ref> In the mid-20th century ] developed a variant of the modern Celtic harp which he referred to as the "Breton Celtic harp"; his son ] was to become the most influential Breton harper, and a strong influence in the broader world of the Celtic harp. | |||

| In current pop music, however, the harp appears relatively rarely. ] and ] have separately established images as harp-playing singer-songwriters with signature harp and vocal sounds. A pedal harpist, ], is a member of the "symphonic pop" band ], and ] sometimes features acoustic and electric harp in her work. ] was the first known rock band featuring a pedal harp to appear on a major record label, and released only one record, in 1983. The pedal harp was also present in the ] and ] concert/album ] as part of the ] orchestra. Some Celtic-pop crossover bands and artists such as ] and ] include folk harps. | |||

| == |

=== Multi-course harps === | ||

| A ] is a harp with more than one row of strings, as opposed to the more common "single course" harp. On a double-harp, the two rows generally run parallel to each other, one on either side of the neck, and are usually both ] (sometimes with levers) with identical notes. | |||

| ===Political=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| <!-- <div style="float:right; width:160px; padding:8px; margin-left: 1em; text-align:center">]<br>'''The Coat of Arms of the ]'''</div> --> | |||

| The harp has been used as a political symbol of ] for centuries. It was used to symbolise Ireland in the ] of King ] of Scotland, England and Ireland in ] and had continued to feature on all ], ] and ] Royal Standards ever since, though the style of harp used differed on some Royal Standards. It was also used on the ] of ], issued in ] and on the ] issued in ] as well as on the ] issued on the succession of ] in ]. The harp is also traditionally used on the flag of ]. | |||

| The ] originated in Italy in the 16th century, and arrived in Wales in the late 17th century where it established itself in the local tradition as the Welsh harp (''telyn deires'', "three-row harp").<ref name=Koch>{{cite book |last=Koch |first=John T. |year=2006 |title=Celtic Culture: A historical encyclopedia |volume=1 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-85109-440-0 |page= ''ff'' }}</ref> The triple harp's string set consists of two identical outer rows of standard ] tuned strings (same as a double-harp) with a third set of strings between them tuned to the missing ] notes. The strings are spaced sufficiently for the harpist to reach past the outer row and pluck an inner string when a chromatic note is needed. | |||

| Independent Ireland continued to use the harp as its state symbol on the ], featuring it both on the ] and on the ] ] and ] - as well as on various other official seals and documents. The harp also appears on ] from the ] to the current ]. | |||

| === Chromatic-strung harps === | |||

| :''See also: ]'' | |||

| Some harps, rather than using pedal or lever devices, achieve chromaticity by simply adding additional strings to cover the notes outside their diatonic home scale. The Welsh triple harp is one such instrument, and two other instruments employing this technique are the ] and the ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| A ] version of harp known in ] as 'yaal', is the symbol of ], ], whose legendary root originates from a harp player. | |||

| The cross-strung harp has one row of diatonic strings, and a separate row of chromatic notes, angled in an "X" shape so that the row which can be played by the right hand at the top may be played by the left hand at the bottom, and vice versa. This variant was first attested as the ''arpa de dos órdenes'' ("two-row harp") in Spain and Portugal, in the 17th century.<ref name="MikishkaMusic1989">{{Cite book |last=Mikishka |first=Patricia O. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h3g9AQAAIAAJ |title=Single, double, and triple harps, 1581–1782: Harps having two or three rows of parallel strings. Part II |date=1989 |publisher=Stanford University |page=48 |department=Department of Music}}</ref> | |||

| The inline chromatic harp is generally a single-course harp with all 12 notes of the chromatic scale appearing in a single row. Single course inline chromatic harps have been produced at least since 1902, when ] of ] patented a model of inline chromatic harp.<ref name="Society1903">{{Cite book |title=Zeitschrift |collaboration=International Musical Society |date=1903 |publisher=Breitkopf und Härtel |page=}}</ref> | |||

| ===Corporate=== | |||

| The harp is also used extensively as a ] - both ] and ] organisations. For instance; Ireland's most famous drink, ], also uses a harp, but in reverse and also less detailed than the state arms - ] is also produced by Guinness and uses the harp. | |||

| === Electric harps === | |||

| Relatively new organizations also use the harp, but often modified to reflect a ] relevant to their organization, for instance; ] uses a modified harp, somewhat in the form of an ] taking flight, and the ] uses it with an ] theme. | |||

| Amplified (electro-acoustic) hollow body and solid body ] are produced by many harp makers, including ], ], and ]. They generally use individual ] sensors for each string, often in combination with small internal microphones to produce a mixed electrical signal. Hollow body instruments can also be played acoustically, while solid body instruments must be amplified. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Other organizations in Ireland use the harp, but not always prominently; these include the ] and the associated ], and the ]. In ] the ] and ] use the harp as part of their identity. | |||

| The late-20th century ] is a modern purpose-built electric double harp made of stainless steel based on the traditional West African ]. | |||

| == |

== Variations == | ||

| Harps vary globally in many ways. In terms of size, many smaller harps can be played on the lap, whereas larger harps are quite heavy and rest on the floor. Different harps may use strings of ], ], ], or some combination. | |||

| [[Image:Harp - Punch cartoon - Project Gutenberg eText 16628.png|thumb|''Mollie''. "Auntie, don't cats go to heaven?"<br> | |||

| ''Auntie''. "No, my dear. Didn't you hear the Vicar say at the Children's Service that animals hadn't souls and therefore could not go to heaven?"<br> | |||

| ''Mollie''. "Where do they get the strings for the harps, then?" | |||

| ---- | |||

| <small>Cartoon in ] 4 August 1920]] | |||

| All harps have a ], ], and ], '''frame harps''' or '''triangular harps''' have a pillar at their long end to support the strings, while '''open harps''', such as '''arch harps''' and '''bow harps''', do not. | |||

| * - a directory of harp-related links | |||

| * - general information about the harp | |||

| * - about the Gaelic harp of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands | |||

| * - Information about early Irish and Scottish harps | |||

| * - descriptions of several types of historical European harps (with sound samples) | |||

| * - information on Celtic and other types of harps | |||

| Modern harps also vary in techniques used to extend the range and ] of the strings (e.g., adding sharps and flats). On '''lever harps''' one adjusts a string's note mid-performance by flipping a lever, which shortens the string enough to raise the pitch by a chromatic sharp. On '''pedal harps''' depressing the pedal one step turns geared levers on the strings for all octaves of a single pitch; most allow a second step that turns a second set of levers. The ] is a standard instrument in the ] of the ] (ca. 1800–1910 CE) and the 20th and 21st century music era. | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| <references /> | |||

| == Structure and mechanism == | |||

| ==References== | |||

| ] | |||

| *The Anglo Saxon Harp, Spectrum, Vol. 71, No.2 (Apr., 1996), pp 290-320. | |||

| *The Origins of the Clairsach or Irish Harp. Musical times, Vol. 53, No 828 (Feb 1912), pp 89-92. | |||

| *Courteau, Mona-Lynn. "Harp". In J. Shepherd, D. Horn, D. Laing, P. Oliver and P. Wicke (Eds.), ''The Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World'', Vol. 2, 2003, pp. 427-437. | |||

| *Faul, Michel. "Nicolas Bochsa : harpiste, compositeur, escroc"; first biography (in French) of one of the most celebrated harpists in the XIXth century : | |||

| *Latham, Alison (2002), The Oxford Companion to music, (Harpa) Oxford University Press p564. | |||

| *Woods, Sylvia. "Teach Yourself to Play Celtic Harp"; A companion video is available. | |||

| Harps are essentially ] and made primarily of wood. ''Strings'' are made of gut or wire, often replaced in the modern day by ] or metal. The top end of each string is secured on the ''crossbar'' or ], where each will have a '']'' or similar device to adjust the pitch. From the crossbar, the string runs down to the ] on the resonating ''body'', where it is secured with a knot; on modern harps the string's hole is protected with an ] to limit wear on the wood. The distance between the tuning peg and the soundboard, as well as tension and weight of the string, determine the pitch of the string. The body is hollow, and when a ] string is plucked, the body ], projecting sound. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The longest side of the harp is called the ''column'' or ''pillar'' (though some earlier harps, such as a "bow harp", lack a pillar). On most harps the sole purpose of the pillar is to hold up the neck against the great strain of the strings. On harps which have pedals (largely the modern concert harp), the pillar is a hollow column and encloses the rods which adjust the pitches, which are levered by pressing pedals at the base of the instrument. | |||

| {{Link FA|sr}} | |||

| On harps of earlier design, a single string produces only a single pitch unless it is retuned. In many cases this means such a harp can only play in one key at a time and must be retuned to play in another key. Harpers and ]s have developed various remedies to this limitation: | |||

| ] | |||

| * the addition of extra strings to cover ] notes (sometimes in separate or angled rows distinct from the main row of strings), | |||

| ] | |||

| * addition of small levers on the crossbar which when actuated raise the pitch of a string by a set interval (usually a semitone), or | |||

| ] | |||

| * use of pedals at the base of the instrument, pressed with the foot, which move additional small pegs on the crossbar. The small pegs gently contact the string near the tuning peg, changing the vibrating length, but not the tension, and hence the pitch of the string. | |||

| ] | |||

| These solutions increase the versatility of a harp at the cost of adding complexity, weight, and expense. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{clear left}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| == Terminology and etymology == | |||

| ] | |||

| The modern English word harp comes from the Old English ''hearpe''; akin to Old High German ''harpha''.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Harp |encyclopedia=Oxford Dictionaries |url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/harp |access-date=30 April 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160913133045/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/harp |archive-date=13 September 2016 |url-status=dead}}</ref> A person who plays a pedal harp is called a "harpist";<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Harpist |encyclopedia=Oxford Dictionaries |url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/harpist |access-date=25 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151018071631/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/harpist |archive-date=18 October 2015 |url-status=dead}}</ref> a person who plays a folk-harp is called a "harper" or sometimes a "harpist";<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Harper |encyclopedia=Oxford Dictionaries |url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/harper |access-date=25 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160624023221/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/harper |archive-date=24 June 2016 |url-status=dead}}</ref> either may be called a "harp-player", and the distinctions are not strict. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| A number of instruments that are not harps are none-the-less colloquially referred to as "harps". Chordophones like the ] (wind harp), the ], the ], as well as the piano and ], are not harps, but ]s, because their strings are parallel to their soundboard. Harps' strings rise approximately perpendicularly from the soundboard. Similarly, the many varieties of ] and ], while chordophones, belong to the ] family and are not true harps. All forms of the ] and ] are also not harps, but belong to the fourth family of ancient instruments under the chordophones, the ''lyres'', closely related to the ''zither'' family. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The term "harp" has also been applied to many instruments which are not even chordophones. The ] was (and is still) sometimes referred to as the "vibraharp", though it has no strings and its sound is produced by striking metal bars. In blues music, the harmonica is often casually referred to as a "blues harp" or "harp", but it is a ] wind instrument, not a stringed instrument, and is therefore not a true harp. The ] is neither Jewish nor a harp; it is a ] and likewise not a stringed instrument. The ] is not a stringed instrument at all, but is a harp-shaped electronic instrument controller that has laser beams where harps have strings. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| == As a symbol == | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| === Political === | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ==== Ireland ==== | |||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The harp has been used as a political symbol of Ireland for centuries. Its origin is unknown but from the evidence of the ancient oral and written literature, it has been present in one form or another since at least the 6th century or before. According to tradition, ], ] (died at the ], 1014) played the harp, as did many of the gentry in the country during the period of the ] (ended {{circa|1607}} with the ] following the ]).{{Citation needed|date=March 2011}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In traditional Gaelic society every ] and chief of any consequence would have a resident harp player who would compose eulogies and elegies (later known as "planxties") in honour of the leader and chief men of the clan. The harp was adopted as a symbol of the ] on the coinage from 1542, and in the ] of ] in 1603 and continued to feature on all English and United Kingdom Royal Standards ever since, though the styles of the harps depicted differed in some respects. It was also used on the ] of ] issued in 1649 and on the ] issued in 1658 as well as on the Lord Protector's Standard issued on the succession of ] in 1658. The harp is also traditionally used on the ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Since 1922, the ] has used a similar left-facing harp, based on the ] in the ] of ] as its state symbol. This design first appeared on the ], which in turn was replaced by the ], the ] and the ] in the 1937 ]. The harp emblem is used on official state seals and documents including the ] and has appeared on ] from the ] to the current Irish imprints of ] coins. | |||

| ==== Elsewhere ==== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The South Asian ] is the symbol of ], Sri Lanka, whose legendary root originates from a harp player.<ref name="BlazeBlaze1921">{{Cite book |last1=Blaze, L.E. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hlpLH0w6VWUC&pg=PA45 |title=The Story of Lanka: Outlines of the history of Ceylon from the earliest times to the coming of the Portuguese |last2=Blaze, Louis Edmund |publisher=Asian Educational Services |year=1921 |isbn=978-81-206-1074-3 |page=45}}</ref> | |||

| The arms of the Finnish city of ] features a red, eagle-headed harp. | |||

| === Religious === | |||

| ])]] | |||

| In the context of ], ] is sometimes symbolically depicted as populated by ] playing harps, giving the instrument associations of the sacred and heavenly. In the Bible, ] 4:21 says that ], the first musician and son of ], was 'the father of all who play' the harp and flute.<ref>{{Cite book |title=New International Version / King James Version |via=BibleGateWay.com |at=4:21 |chapter=Genesis |chapter-url=https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Genesis+4%3A21&version=NIV;KJV}}</ref><ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Van Vechten |first=Carl |author-link=Carl Van Vechten |year=1919 |title=On the relative difficulties of depicting heaven and hell in music |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ezszAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA553 |pages=553ff |periodical=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Woodstra |first1=Chris |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nlDOICBmhbkC&pg=PA699 |title=All-Music Guide to Classical Music: The definitive guide to classical music |last2=Brennan |first2=Gerald |last3=Schrott |first3=Allen |publisher=Backbeat Books |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-87930-865-0 |pages=699ff}}</ref> | |||

| Many depictions of ] in Jewish art have him holding or playing a harp, such as a sculpture outside ] in Jerusalem.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Plassio |first1=Marco |title=Jerusalem – King David |url=https://commons.wikimedia.org/File:Jerusalem_-_King_David.jpg |website=Wikimedia Commons |date=8 August 2011 |publisher=Wikimedia Foundation |access-date=17 February 2024}}</ref> | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| === Corporate === | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The harp is also used extensively as a ], predominantly by companies that have, or wish to suggest, a connection with Ireland. The Irish brewer ] has used a right-facing harp (in contrast to the Irish State emblem's left-facing version) as its emblem since 1759, the ] brand has done so since 1960. The ] newspaper has used a harp in its ] since 1961. The Irish airline ], founded in 1985, also features a stylised harp in its logo. | |||

| Other organisations in Ireland use the harp in their corporate identity, but not always prominently; these include the ] and the associated ], and the ]. In ], the ] and the ] use the harp as part of their identity. | |||

| === Sporting === | |||

| In sport, the harp is used in the emblems of the League of Ireland football team ], Donegal's senior soccer club. Outside of Ireland, it appears in the badge of the ] team ] – a team originally founded by Irish emigrants. | |||

| Not all sporting uses of the harp are references to Ireland, however: the Iraqi football club ] has used a harp as its emblem since the early 1990s, after they gained the nickname ''Al-Qithara'' ({{langx|aii|"the harp"}}) when their style of play was likened to fine harp-playing by a television presenter. | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| === Types of harp === | |||

| * ], or Clàrsach, a modern replica of Medieval north European harps | |||

| * ], a 19th century instrument that combined a harp with a keyboard | |||

| * ], a 40 stringed instrument in ancient Greece thought to have been a harp | |||

| * ], a traditional Finnish and Karelian zither-like instrument | |||

| * ], name shared by an ancient Chinese harp and a modern re-adaption | |||

| * ], a west-African folk-instrument, intermediate between a harp and a lute | |||

| * ], ], zither-like instruments used in Greek classical antiquity and later | |||

| * ], the modern, chromatic concert harp | |||

| * ], a small, flat, lap instrument in the zither family | |||

| * ], a chromatic multi-course harp traditional in Wales | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{reflist|25em}} | |||

| == Sources == | |||