| Revision as of 13:31, 11 June 2006 view sourceTawkerbot2 (talk | contribs)131,306 editsm BOT - rv 24.45.161.106 (talk) to last version by 217.37.117.9← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:45, 21 December 2024 view source Dark4tune (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,833 edits Added the word "the". | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1918–1992 country in Southeast Europe}} | |||

| '''Yugoslavia''' (''Jugoslavija'' in all ], ''Југославија'' in ] and ] ]) is a term used for three separate but successive political entities that existed during most of the ] on the ] in ]. Translated, the name means Land of the South ] (''jug'' in the word ''Jugoslavija'' means south). | |||

| {{About|the country that existed until 1992|the self-proclaimed successor state, called "Federal Republic of Yugoslavia" until 2003|Serbia and Montenegro}} | |||

| {{redirects here|Jugoslavija|the defunct magazine|Jugoslavija (magazine)|other uses|Yugoslavia (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2021}} | |||

| {{Infobox former country | |||

| | conventional_long_name = Yugoslavia | |||

| | native_name = {{lang|sh-Latn|Jugoslavija}}<br />{{lang|sh-Cyrl|Југославија}} | |||

| | common_name = Yugoslavia | |||

| | life_span = 1918–1992<br />1941–1945: ] | |||

| | p1 = Kingdom of Serbia{{!}}Serbia | |||

| | flag_p1 = State Flag of Serbia (1882-1918).svg | |||

| | p2 = Kingdom of Montenegro{{!}}Montenegro | |||

| | flag_p2 = Flag of the Kingdom of Montenegro.svg | |||

| | p3 = State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs | |||

| | flag_p3 = Flag of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.svg | |||

| | p4 = Austria-Hungary | |||

| | flag_p4 = Flag of Austria-Hungary (1867-1918).svg | |||

| | p7 = Free State of Fiume{{!}}Fiume | |||

| | flag_p7 = Flag of the Free State of Fiume.svg | |||

| | s1 = Croatia | |||

| | flag_s1 = Flag of Croatia (1990).svg | |||

| | s2 = Slovenia | |||

| | flag_s2 = Flag of Slovenia.svg | |||

| | s3 = North Macedonia{{!}}Macedonia | |||

| | flag_s3 = Flag of Macedonia (1992–1995).svg | |||

| | s4 = Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina{{!}}Bosnia and Herzegovina | |||

| | flag_s4 = Flag of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992-1998).svg | |||

| | s5 = Serbia and Montenegro{{!}}Federal Republic of Yugoslavia | |||

| | flag_s5 = Flag of Serbia and Montenegro (1992–2006).svg | |||

| | image_flag = Flag of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.svg{{!}}class=notpageimage | |||

| | image_flag2 = Flag of SFR Yugoslavia.svg{{!}}class=notpageimage | |||

| | flag_type = ] | |||

| | flag_border = | |||

| | image_coat = ] ] | |||

| | symbol_type = ] | |||

| | image_map = Yugoslavia location map.svg | |||

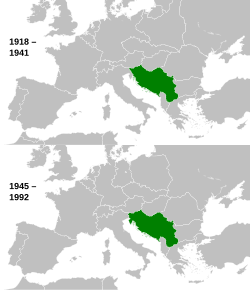

| | image_map_caption = Yugoslavia during the ] (top) and the ] (bottom) | |||

| | national_motto = | |||

| | national_anthem = <br />"]" (1919–1941){{parabr}}]"]" (1945–1992){{parabr}}] | |||

| | capital = ] | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|44|49|N|20|27|E|type:city_source:kolossus-hewiki|display=inline}} | |||

| | largest_city = capital | |||

| | demonym = ] | |||

| | official_languages = ] {{small|(before 1944)}} <br/> ] {{small|(de facto; from 1944)}} | |||

| | government_type = ]<br>(1918–1941)<br/>]<br>(1945–1992) | |||

| {{Collapsible list | |||

| |title = Details{{overly detailed inline|date=December 2024}} | |||

| |bullets = yes | |||

| |] ] {{Clear}}{{small|(1918–1929, 1931–1939)}} | |||

| |] ] under a ] {{small|(1929–1931)}} | |||

| |] ] {{Clear}}{{small|(1939–1941)}} | |||

| |] {{small|(1941–1945)}} | |||

| |] ] presiding over ] {{small|(1943–1945)}} | |||

| |] ] ] ] {{small|(1945–1948)}} | |||

| |] ] ] ] {{small|(1948–1990)}} | |||

| |] ] ] {{small|(1990–1992)}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | title_leader = | |||

| | leader1 = | |||

| | year_leader1 = | |||

| | event_start = ] | |||

| | date_start = 1 December | |||

| | year_start = 1918 | |||

| | event1 = ] | |||

| | date_event1 = 6 April 1941 | |||

| | event2 = ] | |||

| | date_event2 = 29 November 1945 | |||

| | event_end = ] | |||

| | date_end = 27 April | |||

| | year_end = 1992 | |||

| | stat_year1 = 1955 | |||

| | stat_pop1 = 17,522,438<ref>{{cite web|url=https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G1955/Pdf/G19552002.pdf|title=Statistical yearbook of Yugoslavia, 1955 |website=publikacije.stat.gov.rs |publisher=Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia Federal Statistical Office}}</ref> | |||

| | stat_year2 = 1965 | |||

| | stat_pop2 = 19,489,605<ref>{{cite web|url=https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G1965/Pdf/G19652001.pdf|title=Statistical yearbook of Yugoslavia, 1965 |website=publikacije.stat.gov.rs |publisher=Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia Federal Statistical Office}}</ref> | |||

| | stat_year3 = 1975 | |||

| | stat_pop3 = 21,441,297<ref>{{cite web|url=https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G1975/Pdf/G19752003.pdf|title=Statistical yearbook of Yugoslavia, 1975 |website=publikacije.stat.gov.rs |publisher=Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia Federal Statistical Office}}</ref> | |||

| | stat_year4 = 1985 | |||

| | stat_pop4 = 23,121,383<ref>{{cite web|url=https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G1985/Pdf/G19852003.pdf|title=Statistical yearbook of Yugoslavia, 1985 |website=publikacije.stat.gov.rs |publisher=Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia Federal Statistical Office}}</ref> | |||

| | stat_year5 = 1991 | |||

| | stat_pop5 = 23,532,279<ref>{{cite web|url=https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G1991/Pdf/G19912003.pdf|title=Statistical yearbook of Yugoslavia, 1991 |website=publikacije.stat.gov.rs |publisher=Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia Federal Statistical Office}}</ref> | |||

| | cctld = ] | |||

| | iso3166code = YU | |||

| | calling_code = 38 | |||

| | currency = ] | |||

| | footnotes = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Yugoslavia''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|j|uː|ɡ|oʊ|ˈ|s|l|ɑː|v|i|ə}}; {{Literal translation|Land of the ]}}){{efn|In national languages: | |||

| * The first was a ] formed in ], ] as the ''']''', which was re-named the ''']''' on ], ] and existed under that name until it was invaded on ], ] by the ]. Capitulating only 11 days later, it ceased to exist ], ]. | |||

| * {{lang-sh-Latn-Cyrl|separator=" / "|Jugoslavija|Југославија}} {{IPA|sh|juɡǒslaːʋija|}}; | |||

| * {{langx|sl|Jugoslavija}} {{IPA|sl|juɡɔˈslàːʋija|}}; | |||

| * {{langx|mk|Југославија}} {{IPA|mk|juɡɔˈsɫavija|}} {{paragraph break}} | |||

| In regional and minority languages: | |||

| * {{langx|sq|Jugosllavia}}; | |||

| * {{langx|rup|Iugoslavia}}; | |||

| * {{langx|hu|Jugoszlávia}}; | |||

| * {{langx|rue|label=]|Югославия|translit=Juhoslavija}}; | |||

| * {{langx|sk|Juhoslávia}}; | |||

| * {{langx|ro|Iugoslavia}}; | |||

| * {{langx|cs|Jugoslávie}}; | |||

| * {{langx|it|Iugoslavia}}; | |||

| * {{langx|tr|Yugoslavya}}; | |||

| * {{langx|bg|Югославия|Yugoslaviya}}}} was a country in ] and ] that existed from 1918 to 1992. It ] following ],{{efn|The ], led by ]n ] politician ], lobbied the Allies to support the creation of an independent ] state and delivered the proposal in the ] on 20 July 1917.<ref name="Spencer Tucker 2005">Spencer Tucker. ''Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social, and Military History''. Santa Barbara, California, US: ABC-CLIO, 2005. Pp. 1189.</ref>}} under the name of the ] from the merger of the ] with the provisional ], and constituted the first union of South Slavic peoples as a ], following centuries of foreign rule over the region under the ] and the ]. ] was its ]. The kingdom gained international recognition on 13 July 1922 at the ] in ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.orderofdanilo.org/en/family/index.htm|title=orderofdanilo.org|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090516203805/http://www.orderofdanilo.org/en/family/index.htm|archive-date=16 May 2009}}</ref> The official name of the state was changed to the ] on 3 October 1929. | |||

| The kingdom was ] and ] by the ] in April 1941. In 1943, ] was proclaimed by the ]. In 1944, ], then living ], recognised it as the legitimate government. After a ] was elected in November 1945, the monarchy was abolished, and the country was renamed the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia. It acquired the territories of ], ], and ] from ]. Partisan leader ] ruled the country from 1944 as prime minister and later as ] until ] in 1980. In 1963, the country was renamed for the final time, as the ] (SFRY). | |||

| * The second was a ] established immediately after ] in ], ] as Democratic Federation of Yugoslavia (DFY), which in ] became the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (FPRY) and then the '''].''' | |||

| The six constituent republics that made up the SFRY were the socialist republics of ], ], ], ], ], and ]. Within Serbia were the two socialist autonomous provinces, ] and ], which following the adoption of the ] were largely equal to the other members of the federation.<ref>{{cite book |last=Huntington |first=Samuel P. |title=The clash of civilizations and the remaking of world order |publisher=Simon & Schuster |isbn=978-0-684-84441-1 |year=1996 |page=|title-link=The Clash of Civilizations }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/special_report/1998/kosovo/110492.stm |title=History, bloody history |work=BBC News |date=24 March 1999 |access-date=29 December 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090125151232/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/special_report/1998/kosovo/110492.stm |archive-date=25 January 2009 |url-status=live }}</ref> After an economic and political crisis and the rise of ] and ]s following Tito's death, Yugoslavia ] along its republics' borders during the ], at first into five countries, leading to the ]. From 1993 to 2017, the ] tried political and military leaders from the former Yugoslavia for ], genocide, and other crimes committed during those wars. | |||

| * The third was called '''] (FRY)''' and was formed in 1992 on the territory of the two remaining republics of ] (including the autonomous provinces of ] and of ], officially known as Kosovo and ]) and ]. On ], ], the name Yugoslavia was officially abolished when the state transformed into a loose commonwealth called ]. On ], ], ] voted to separate from the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro and establish itself as an independent state. Montenegro officially declared its independence on ], ], while Serbia declared independence on June 5, thereby ending the vestiges of the former Yugoslav federation. | |||

| After the breakup, the republics of ] and ] formed a reduced federative state, the ] (FRY). This state aspired to the status of sole ] to the SFRY, but those claims were opposed by the other former republics. Eventually, it accepted the opinion of the ] about shared succession<ref name="EBRD Country Promotion Programme">{{cite web|title=FR Yugoslavia Investment Profile 2001|url=http://www.fifoost.org/jugoslaw/yugo.pdf|publisher=EBRD Country Promotion Programme|page=3|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110928025829/http://www.fifoost.org/jugoslaw/yugo.pdf|archive-date=28 September 2011}}</ref> and in 2003 its official name was changed to Serbia and Montenegro. This state ] when ] and ] each became independent states in 2006, with ] having an ] over its ] in 2008. | |||

| __TOC__ | |||

| {{splitsection|History of Yugoslavia}} | |||

| == |

==Background== | ||

| {{Main|Creation of Yugoslavia}} | |||

| The concept of ''Yugoslavia'', as a common state for all ] peoples, emerged in the late 17th century and gained prominence through the ] of the 19th century. The name was created by the combination of the Slavic words {{wikt-lang|sh|jug}} ("south") and {{wikt-lang|sh|Slaven|Slaveni}}/{{wikt-lang|sh|Sloven|Sloveni}} (Slavs) and was in use as early as 1922 onward.<ref>{{cite EB1922 |wstitle= Yugoslavia |volume = 32 |last= Seton-Watson |first= Robert |author-link= Robert Seton-Watson |short= 1}}</ref> Moves towards the formal ] accelerated after the 1917 ] between the ] and the government of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jezernik |first1=Božidar |title=Yugoslavia without Yugoslavs: The History of a National Idea |date=2023 |publisher=Berghahn Books |isbn=9781805390442 |pages=221–222 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UEmnEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA222}}</ref> | |||

| During the early period of the World War One (1914), a number of prominent political figures (], ], ], ], ], ] and ]) from south-Slav lands under the ] (Austria-Hungary), fled to London where they began work on forming Yugoslav Committee and their mission was to represent the south Slavs of the empire. They chose London as their headquarters. | |||

| The ] (''Jugoslavenski odbor'') was officially formed on ], ] in ], and it began to raise funds, especially among south-Slavs living in the Americas. Because of their stature, the members of the Yugoslav Committee were able to make their views known to the Allied governments, which began to take them increasingly seriously, especially as the fate of ] looked more uncertain. While the committee's basic aim was the unification of the Habsburg south Slav lands with Serbia (which was independent at the time), its more immediate concern was to head off Italian claims in ] and ]. This was a very real concern. In 1915, the Allies had lured the Italians into the war with promise of substantial territorial gains in exchange. According to the secret Treaty of London these included Istria and large parts of Dalmatia, where relatively small numbers of Italians lived compared to the surrounding Slavs. Although in 1915 the Serbian Assembly had pledged itself to work for the liberation of all Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, non-Serb members of the Yugoslav Committee became alarmed when the Allies offered Serbia lands that had not been reserved for Italians. These included Bosnia, Herzegovina, Slavonia, Bačka and parts of Dalmatia. Croat members of the Committee feared carve-up of Croat lands between Serbia and Italy. There were also quarrels about the designation and command of units of south Slav POWs in Russia now being mobilised to fight with the Allies. The Yugoslav Committee wanted them to fight in the Yugoslav name, while Pašić (Prime Minister of Serbia) seeing in this a "Croat Army", wanted them to fight under the Serbian flag. | |||

| ==Kingdom of Yugoslavia== | |||

| However, during June and July 1917, the Yugoslav committee met with the Serbian Government in Corfu and on ] a declaration that laid foundation of the post-war state was issued. The preamble stated that the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes were "the same by blood, by language, by the feelings of their unity, by the continuity and integrity of the territory which they inhabit undividedly, and by the common vital interests of their national survival and manifold development of their moral and material life". The future state was to be called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and was to be constitutional monarchy under the Karadjordjević dynasty. | |||

| {{Main|Kingdom of Yugoslavia}} | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| |align=right | |||

| |direction=vertical | |||

| |width=210 | |||

| |header= | |||

| |image1= | |||

| |image2=Banovine Jugoslavia.png|caption2=] of Yugoslavia, 1929–39. After 1939 the Sava and Littoral banovinas were merged into the ]. | |||

| }} | |||

| The country was formed in 1918 immediately after World War I as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes by union of the ] and the ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Fenwick|first=Charles G.|date=1918|title=Jugoslavic National Unity|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1945848|journal=The American Political Science Review|volume=12|issue=4|pages=718–721|doi=10.2307/1945848|jstor=1945848|s2cid=147372053 |issn=0003-0554}}</ref> It was commonly referred to at the time as a "] state".<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Rutherford |first1=Malcolm |last2=Hibbert |first2=Reginald |last3=Somerville |first3=Keith |date=1995 |title=Notes of the Month |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40396747 |journal=The World Today |volume=51 |issue=8/9 |pages=156 |jstor=40396747 |issn=0043-9134}}</ref> Later, ] renamed the country to ''Yugoslavia'' in 1929.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| As the Habsburg Empire dissolved, a National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs took power in Zagreb on ] ]. On ], the Croatian Sabor or parliament declared independence and vested its sovereignty in the new State of the Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. The Yugoslav Committee was given the task of representing the new state abroad. However quarrels broke out immediately about the terms of the proposed union with Serbia. Svetozar Pribićević, a Croatian Serb, a leader of the Croatian-Serbian Coalition and vice-precident of the state, wanted an immediate and unconditional union. Others (non-Serbs), who favoured a federal Yugoslavia were more hesitant. They feared that Serbia would simply annex the former Habsburg territories. The National Council's authority was limited and the Italians were moving to take more territory than they had been alloted in an agreement with the Yugoslav Committee. Political opinion was divided and Serbian ministers said that if Croats insisted on their own republic or sort of independence, then Serbia would simply take areas inhabited by the Serbs and already occupied by the Serbian Army. After much debate the National Council agreed to unification with Serbia, although its declaration stated that the final organization of the state should be left to the future Constituent Assembly. The most prominent opponent of this decision was Stjepan Radić, the leader of the Croatian Peasant Party (Hrvatska Seljačka Stranka, HSS). | |||

| However, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was declared on 1 December 1918 in Belgrade. | |||

| ===King Alexander=== | |||

| == Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (first Yugoslavia) == | |||

| {{see also|6 January Dictatorship}} | |||

| {{main|Kingdom of Yugoslavia}} | |||

| On 20 June 1928, Serb deputy ] shot at five members of the opposition ] in the ], resulting in the death of two deputies on the spot and that of leader ] a few weeks later.{{sfn|Ramet|2006|p=73}} On 6 January 1929, ] ] got rid of the ], ], ], and renamed the country Yugoslavia.<ref name=":1" /><ref>{{cite web |url =http://www.indiana.edu/~league/1929.htm |title =Chronology 1929 |author =] |publisher =indiana.edu |date =October 2002 |access-date =8 February 2014 |archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20150222035557/http://www.indiana.edu/~league/1929.htm |archive-date =22 February 2015 |url-status =live }}</ref> He hoped to curb separatist tendencies and mitigate nationalist passions. He imposed a ] and relinquished his dictatorship in 1931.<ref>{{cite web |url =http://www.indiana.edu/~league/1931.htm |title =Chronology 1929 |author =] |publisher =indiana.edu |date =October 2002 |access-date =8 February 2014 |archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20140222001410/http://www.indiana.edu/~league/1931.htm |archive-date =22 February 2014 |url-status =live }}</ref> However, Alexander's policies later encountered opposition from other European powers stemming from developments in Italy and Germany, where Fascists and ] rose to power, and the ], where ] became absolute ruler. None of these three regimes favored the policy pursued by Alexander I. In fact, Italy and Germany wanted to revise the international treaties signed after World War I, and the Soviets were determined to regain their positions in Europe and pursue a more active international policy.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} | |||

| With the end of World War I and the downfall of Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, the conditions were met for proclaiming the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians in December 1918. Of the country's 12 million people, 4.6 million (38.8 percent) were Serbs and 2.8 million (23.7 percent) were Croats. The Yugoslav ideal had long been cultivated by some intellectual circles of the three nations but most influential Croatian politicians opposed the new state right from the start. The Croatian Peasants' Party (HSS) slowly grew to become a massive party endorsing Croatian national interests and seeking confederation. | |||

| Alexander attempted to create a centralised Yugoslavia. He decided to abolish Yugoslavia's historic regions, and new internal boundaries were drawn for provinces or banovinas.<ref name="DoniaFine1994">{{cite book |last1=Donia |first1=Robert J. |last2=Fine |first2=John Van Antwerp |title=Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed |date=1994 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=9780231101615 |page=129 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=stOIQ5GXIDgC&pg=PA129}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Atkeson |first1=Edward B. |title=The New Legions: American Strategy and the Responsibility of Power |date=2011 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=9781442213777 |page=141 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0QFUOVXylsQC&pg=PA141}}</ref> The banovinas were named after rivers.<ref name="DoniaFine1994" /> Many politicians were jailed or kept under police surveillance. During his reign, communist movements were restricted.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Roszkowski |first1=Wojciech |last2=Kofman |first2=Jan |title=Biographical Dictionary of Central and Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century |date=2016 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-31747-593-4 |pages=3465 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RnKlDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA3465}}</ref> | |||

| The elections for the Constituent Assembly in November 1920 brought victory for the two main Serbian parties. Communists came third and Croatian Peasant Party fourth. The newly formed government was determined to push through a centralist constitution. In response, the Croatian Peasant Party prepared a draft constitution for a Neutral Peasant Republic of Croatia. The constitution was passed by vote on 28 June 1921 with the help of some minor parties including the Yugoslav Muslim Organization. Shortly after the constitution was passed, old King Peter died. He was succeeded by Prince Aleksandar II Karadjordjevic. | |||

| The king was assassinated in ] during an official visit to France in 1934 by ], an experienced marksman from ]'s ] with the cooperation of the ], a Croatian fascist revolutionary organisation.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zsTmAAAAMAAJ&q=cernozemski+bulgarian|title=Request by the Yugoslav Government Under Article 11, Paragraph 2, of the Covenant: Communication from the Yugoslav Government|last=]|year=1934|publisher=]|pages=8|language=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KfqbujXqQBkC&dq=cernozemski+bulgarian&pg=PA326|title=The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics|last=Banac|first=Ivo|date=1984|publisher=Cornell University Press|pages=326|isbn=978-0-8014-9493-2}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6B9pAAAAMAAJ&q=tchernozemski+bulgarian|title=Crown of Thorns|last=Groueff|first=Stéphane|date=1987|publisher=Madison Books|pages=224|isbn=978-0-8191-5778-2}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N5-ixYvhfs8C&dq=1934+imro+bulgarian+Vlado&pg=PA261|title=Balkan Firebrand - The Autobiography of a Rebel Soldier and Statesman|last=Kosta|first=Todorov|date=2007|publisher=Read Books|pages=267|isbn=978-1-4067-5375-2}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ViAANnwIYgUC&dq=chernozemski+bulgarian&pg=PA230|title=Violette Noziere: A Story of Murder in 1930s Paris|last=Maza|first=Sarah|date=2011-05-31|publisher=University of California Press|pages=230|isbn=978-0-520-94873-0}}</ref> Alexander was succeeded by his eleven-year-old son ] and a regency council headed by his cousin, ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://digitalna.nb.rs/wb/NBS/Periodika/SD_EA14D129E93A8F6C7A1935AA12C320B4/1934/10/12?pageIndex=00003|title=Краљевски намесници и чланови Народног претставништва положили су јуче заклетву на верност Њ. В. Кралу Петру II|date=12 October 1934|language=sh|work=Време|trans-title=Royal deputies and members of the People's Representative Office took the oath of allegiance to King Peter II yesterday}}</ref> | |||

| Croats, as well as Albanians, who were angry at the Serb return to Kosovo, harboured grievances against the Serbs. Slovenes were able to extract gains from the central Serbo-Croat dispute. Half a million of them lived under Italian rule and the Slovenes understood that it was only as a part of Yugoslavia that they would be able to free these people in Istria. This came about in 1945. However, the Yugoslav Slovenes benefited from the new state receiving all they had previously lacked, in addition to access to high schools and universities. Unlike the Croats, the Slovenes in the Austro-Hungarian Empire had no historic claim to statehood, so there was no sense of loss to Belgrade. | |||

| ===1934–1941=== | |||

| During the 1920s, Serbo-Croat wrangle continued and on 20 June 1928, after months of rows and even fist-fights in Parliament, Puniša Račić, a Montenegrin Serb, leapt up in the chamber and shot two Croats and wounded three others, including Stjepan Radić, who eventually died. | |||

| The international political scene in the late 1930s was marked by growing intolerance between the principal figures, by the aggressive attitude of the ] regimes, and by the certainty that the order set up after World War I was losing its strongholds and its sponsors their strength. Supported and pressured by ] and ], Croatian leader ] and his party managed the creation of the ] (Autonomous Region with significant internal self-government) in 1939.{{cn|date=August 2024}} The agreement specified that Croatia was to remain part of Yugoslavia, but it was hurriedly building an independent political identity in international relations.{{cn|date=August 2024}} | |||

| Prince Paul submitted to fascist pressure and signed the ] in Vienna on 25 March 1941, hoping to continue keeping Yugoslavia out of the war. However, this was at the expense of popular support for Paul's regency. Senior military officers were also opposed to the treaty and launched a coup d'état when the king returned on ]. Army General ] seized power, arrested the Vienna delegation, exiled Prince Paul, and ended the regency, giving 17-year-old ] full powers. ] then decided to attack Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941, followed immediately by an invasion of Greece where ] had previously been repelled.<ref>A. W. Palmer, "Revolt in Belgrade, March 27, 1941", ''History Today'' (March 1960) 10#3 pp 192–200.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www1.yadvashem.org.il/about_holocaust/month_in_holocaust/april/april_chronology/chronology_1941_april_06.html|title=6 April: Germany Invades Yugoslavia and Greece|website=arquivo.pt|url-status=dead|archive-url=http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20091015085557/http%3A//www1.yadvashem.org.il/about_holocaust/month_in_holocaust/april/april_chronology/chronology_1941_april_06.html|archive-date=15 October 2009}}</ref> | |||

| Following this, King Aleksandar I banned national political parties in 1929, assumed executive power and renamed the country Yugoslavia. He hoped to curb separatist tendencies and mitigate nationalist passions. However, the balance of power changed in international relations: in Italy and Germany, Fascists and Nazis rose to power, and Stalin became the absolute ruler in the Soviet Union. None of these three states favoured the policy pursued by Aleksandar I. In fact, the first two wanted to revise the international treaties signed after World War I, and the Soviets were determined to regain their positions in Europe and pursue a more active international policy. Yugoslavia was an obstacle for these plans and King Aleksandar I was the pillar of the Yugoslav policy. | |||

| ==World War II== | |||

| Alexander attempted to create a genuine Yugoslavia. He decided to abolish Yugoslavia's historic regions and new internal boundaries were drawn for provinces or banovinas. The banovinas were named after rivers. Many politicians were jailed or kept under tight police surveillance. The effect of Alexander's dictatorship was to further alienate the non-Serbs of the idea of unity. | |||

| {{main|World War II in Yugoslavia}} | |||

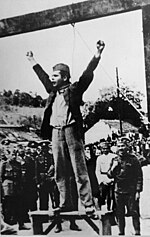

| ] ] shouting "Death to fascism, freedom to the people!" shortly before his execution (1942)]] | |||

| At 5:12 a.m. on 6 April 1941, ], ] and ] forces ].<ref>{{cite web |url =https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/partisan_fighters_01.shtml |title =Partisans: War in the Balkans 1941–1945 |author =Stephen A. Hart |author2 =] |publisher =bbc.com |date =17 February 2011 |access-date =8 February 2014 |archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20111128065207/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/partisan_fighters_01.shtml |archive-date =28 November 2011 |url-status =live }}</ref> The German Air Force ('']'') bombed ] and other major Yugoslav cities. On 17 April, representatives of Yugoslavia's various regions signed an armistice with Germany in Belgrade, ending eleven days of resistance against the invading German forces.<ref>{{cite web |url =http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/yugoslavia-surrenders |title =Apr 17, 1941: Yugoslavia surrenders |author =] |publisher =history.com |year =2014 |access-date =8 February 2014 |archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20140221215720/http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/yugoslavia-surrenders |archive-date =21 February 2014 |url-status =live }}</ref> More than 300,000 Yugoslav officers and soldiers were taken prisoner.<ref>{{cite web |author=] |date=October 2002 |title=Chronology 1929 |url=http://www.indiana.edu/~league/1941.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141027024429/http://www.indiana.edu/~league/1941.htm |archive-date=27 October 2014 |access-date=8 February 2014 |publisher=indiana.edu}}</ref> | |||

| During an official visit to France in 1934, the king was assassinated in Marseilles by a Macedonian with the cooperation of the Ustashi - a Croatian separatist organization. Alexander was succeeded by his eleven year old son Peter II and a regency council headed by his cousin Prince Paul. | |||

| The ] occupied Yugoslavia and split it up. The ] was established as a ] satellite state, ruled by the fascist militia known as the ] that came into existence in 1929, but was relatively limited in its activities until 1941. German troops occupied ] and ] as well as part of ] and ], while other parts of the country were occupied by ], Hungary, and Italy. From 1941 to 1945, the Croatian ] regime ] around 300,000 Serbs, along with at least 30,000 Jews and Roma;<ref>{{cite book |last1=Goldberg |first1=Harold J. |title=Daily Life in Nazi-Occupied Europe |date=2019 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=9781440859120 |page=22 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=h5q1DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA22}}</ref> hundreds of thousands of Serbs were also expelled and another 200,000-300,000 were forced to convert to ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Tomasevich |first1=Jozo |editor1-last=Vucinich |editor1-first=Wayne S. |title=Contemporary Yugoslavia: Twenty Years of Socialist Experiment |date=2021 |orig-year=1969 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=9780520369894 |page=79 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1FXuDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA79 |chapter=Yugoslavia During the Second World War}}</ref> | |||

| The international political scene in the late 1930s was marked by growing intolerance between the principal figures, by the aggressive attitude of the totalitarian regimes and by the certainty that the order set up after World War I was losing its strongholds and its sponsors were losing their strength. Supported and pressured by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, Croatian leader Vlatko Macek and his party managed the creation of the Croatian banovina (administrative province) in 1939. The agreement specified that Croatia was to remain part of Yugoslavia, but it was hurriedly building an independent political identity in international relations. | |||

| From the start, the Yugoslav resistance forces consisted of two factions: the communist-led ] and the royalist ], with the former receiving Allied recognition at the Tehran conference (1943). The heavily pro-Serbian Chetniks were led by ], while the pan-Yugoslav oriented Partisans were led by ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pavlowitch |first1=Stefan |title=Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia |date=2008 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=9780199326631 |page=285 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZK8SEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA285}}</ref> | |||

| Prince Paul submitted to the fascist pressure and signed the ] in ] on ], ], hoping to still keep Yugoslavia out of the war. But this was at the expense of popular support for Paul's regency. Senior military officers were also opposed to the treaty and launched a ] when the king returned on ]. Army General ] seized power, arrested the Vienna delegation, exiled Paul, and ended the regency, giving 17 year old King Peter full powers. | |||

| The Partisans initiated a ] campaign that developed into the largest resistance army in occupied Western and Central Europe. The Chetniks were initially supported by the exiled royal government and the ], but they soon focused increasingly on combating the Partisans rather than the occupying Axis forces. By the end of the war, the Chetnik movement transformed into a collaborationist Serb nationalist militia completely dependent on Axis supplies.<ref>David Martin, Ally Betrayed: The Uncensored Story of Tito and Mihailovich, (New York: Prentice Hall, 1946), 34.</ref> The Chetniks also ] ] and ],<ref>{{cite book|last=Redžić|first=Enver|title=Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War|year=2005|publisher=Tylor and Francis|location=New York|isbn=978-0-7146-5625-0|page=155|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pVCx3jerQmYC&pg=PA155|access-date=18 August 2021|archive-date=18 August 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210818050246/https://books.google.com/books?id=pVCx3jerQmYC&pg=PA155|url-status=live}}</ref> with an estimated 50,000-68,000 victims (of which 41,000 were civilians).<ref name="Geiger">{{cite journal|first=Vladimir|last=Geiger|publisher=Croatian Institute of History|title=Human Losses of the Croats in World War II and the Immediate Post-War Period Caused by the Chetniks (Yugoslav Army in the Fatherand) and the Partisans (People's Liberation Army and the Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia/Yugoslav Army) and the Communist Authorities: Numerical Indicators |journal=Review of Croatian History |volume=VIII |issue=1 |date=2012 |url=https://hrcak.srce.hr/103223?lang=en|page=117|access-date=25 October 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151117064114/https://hrcak.srce.hr/103223?lang=en|archive-date=17 November 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> The highly mobile Partisans, however, carried on their guerrilla warfare with great success. Most notable of the victories against the occupying forces were the battles of ] and ]. | |||

| ] then decided to attack Yugoslavia on ], followed immediately by an invasion of ] where Mussolini had previously been repelled. (As a result, the launch of ] was delayed by four weeks, which proved to be a costly decision.) | |||

| On 25 November 1942, the ] was convened in ], modern day ]. The council reconvened on 29 November 1943, in ], also in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and established the basis for post-war organisation of the country, establishing a federation (this date was celebrated as Republic Day after the war).{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} | |||

| == Yugoslavia during the Second World War == | |||

| At 05:15 on ] ], ], ], ], and ]n forces attacked Yugoslavia. The ] bombed ] and other major Yugoslav cities. On ], representatives of Yugoslavia's various regions signed an armistice with Germany at Belgrade, ending eleven days of resistance against the invading German Wehrmacht. More than three hundred thousand Yugoslav officers and soldiers were taken prisoners. | |||

| The ] were able to expel the Axis from Serbia in 1944 and the rest of Yugoslavia in 1945. The ] provided limited assistance with the liberation of ] and withdrew after the war was over. In May 1945, the Partisans met with Allied forces outside former Yugoslav borders, after also taking over ] and parts of the southern Austrian provinces of ] and ]. However, the Partisans withdrew from Trieste in June of the same year under heavy pressure from Stalin, who did not want a confrontation with the other Allies.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Buchanan |first1=Andrew N. |title=World War II in Global Perspective, 1931-1953: A Short History |date=2019 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-1-1193-6607-2 |page=189}}</ref> | |||

| ], Serbs, Jews and Gypsies were marched to the ]]] | |||

| ] (]), who were burned alive by the Germans]] | |||

| Western attempts to reunite the Partisans, who denied the supremacy of the old government of the ], and the émigrés loyal to the king led to the ] in June 1944; however, ] Josip Broz Tito was in control and was determined to lead an independent communist state, starting as a prime minister. He had the support of Moscow and London and led by far the strongest Partisan force with 800,000 men.<ref>Michael Lees, ''The Rape of Serbia: The British Role in Tito's Grab for Power, 1943–1944'' (1990).</ref><ref>{{cite book|author1=James R. Arnold|author2=Roberta Wiener|title=Cold War: The Essential Reference Guide|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XRd6Y-oiFPAC&pg=PA216|date=January 2012|publisher=ABC-CLIO|page=216|isbn=978-1-6106-9003-4|access-date=17 October 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160101214426/https://books.google.com/books?id=XRd6Y-oiFPAC&pg=PA216|archive-date=1 January 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The ] occupied Yugoslavia and split it up. The ] was established as a Nazi puppet-state, ruled by the Catholic fascist militia known as the ] that came into existence in 1929, but was relatively limited in its activities until 1941. German troops occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as part of ] and ], while other parts of the country were occupied by ], ] and ]. | |||

| The official Yugoslav post-war estimate of ] in Yugoslavia during World War II is 1,704,000. Subsequent data gathering in the 1980s by historians ] and ] showed that the actual number of dead was about 1 million.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Byford |first1=Jovan |title=Picturing Genocide in the Independent State of Croatia: Atrocity Images and the Contested Memory of the Second World War in the Balkans |date=2020 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=978-1-3500-1597-5 |page=158 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N8LkDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA158}}</ref> | |||

| Yugoslavs opposing the ] organized resistance movements. Those inclined towards supporting the old Kingdom of Yugoslavia joined the ], a mostly Serb-composed nationalistic royalist guerilla army led by Colonel ]. Those inclined towards supporting the ] (and against the King) joined the ], led by ], a ]-] member of the ]. | |||

| ==FPR Yugoslavia== | |||

| The NLA initiated a ] campaign which was developed into the largest resistance army in occupied Western and Central Europe. The Chetniks initially made notable incursions and were supported by the exiled royal government as well as the ], but were soon restrained from taking wider actions due to German reprisals against the Serb civilian population. For every killed soldier, the Germans executed 100 civilians, and for each wounded, they killed 50. Following Chetniks' termination of war activities against the Germans, reported atrocities against non-Serb population and frequent collaboration with Italians and (less frequently) Germans against the NLA, the Allies eventually switched to support the NLA. | |||

| {{Main|Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia{{!}}Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia}} | |||

| On 11 November 1945, ] were held with only the Communist-led ] appearing on the ballot, securing all 354 seats. On 29 November, while still in exile, ] ] was deposed by Yugoslavia's ], and the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia was declared.<ref name=Jes>{{cite book |last1=Jessup |first1=John E. |title=A Chronology of Conflict and Resolution, 1945–1985 |year=1989 |publisher=Greenwood Press |location=New York |isbn=978-0-313-24308-0 }}</ref> However, he refused to abdicate. Marshal Tito was now in full control, and all opposition elements were eliminated.<ref name="books.google.com">{{cite book|author1=Arnold and Wiener|title=Cold War: The Essential Reference Guide|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XRd6Y-oiFPAC&pg=PA216|year=2012|page=216|publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=9781610690034|access-date=17 October 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160101214426/https://books.google.com/books?id=XRd6Y-oiFPAC&pg=PA216|archive-date=1 January 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| However, NLA carried on its guerrilla warfare. This led to great civilian loss of life in most regions of Yugoslavia. The ] loss is estimated at 1,027,000 individuals by ] and Bogoljub Kočović, an estimate accepted by the ], while the official Yugoslav authorities claimed 1,700,000 casualties. Very high losses were among Serbs of Bosnia and Croatia, and members of ] (according to the German racist theory: ]s, ]) minorities, high also among all other non-] population. | |||

| On 31 January 1946, the new ] of the ], modelled after the ], established ], an autonomous province, and an autonomous district that were a part of Serbia. The federal capital was Belgrade. The policy focused on a strong central government under the control of the Communist Party, and on recognition of the multiple nationalities.<ref name="books.google.com"/> The flags of the republics used versions of the red flag or ], with a ] in the centre or in the canton.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} | |||

| During the war, the ]-led ] were ''de facto'' rulers on the liberated territories, and the NLA organized ]s to act as civilian government. In Autumn of 1941, the partisans established the ] in the liberated territory of western ]. In November 1941, the ] troops occupied this territory again, while the majority of partisan forces escaped towards Bosnia. | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| On ], ], the ] was convened in ]. The council reconvened on ], ] in ] and established the basis for post-war organisation of the country, establishing a federation (this date was celebrated as Republic Day after the war). | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| ! ] !! ] !! ] !! ] !! Location | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |style="width:7em; font-size:90%;"|] | |||

| |style="width:6em;"|] | |||

| |style="width:4em;"|] | |||

| ! rowspan="6" style="width:4em; background:#fff;"|{{SFRY map|float=center}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |style="font-size:90%;"|] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |style="font-size:90%;"|] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |style="font-size:90%;"|] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| : {{smaller|]}} | |||

| : {{nowrap|{{smaller|]}}}} | |||

| |style="font-size:90%;"|] | |||

| : ] | |||

| : ] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |style="font-size:90%;"|] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |} | |||

| Tito's regional goal was to ] and take control of Albania and parts of Greece. In 1947, negotiations between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria led to the ], which proposed to form a close relationship between the two Communist countries, and enable Yugoslavia to start a ] and use Albania and Bulgaria as bases. Stalin vetoed this agreement and it was never realised. The break between Belgrade and Moscow was now imminent.<ref>{{cite book|author1=John O. Iatrides|author2=Linda Wrigley|title=Greece at the Crossroads: The Civil War and Its Legacy|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Vv1t3D_3vjkC&pg=PA267|year=2004|publisher=Penn State University Press|pages=267–73|isbn=9780271043302|access-date=17 October 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160101214426/https://books.google.com/books?id=Vv1t3D_3vjkC&pg=PA267|archive-date=1 January 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The NLA was able to expel the Axis from Serbia in 1944 and the rest of Yugoslavia in 1945. The ] aided in liberating ] as well as some other territories, but withdrew after the war was over. In May 1945, NLA met with allied forces outside former Yugoslav borders, after taking over also ] and parts of ] southern provinces ] and ]. This was the territory populated predominantly by ] (and ] in ]). However, the NLA withdrew from Trieste in June of the same year. | |||

| Yugoslavia solved the national issue of nations and nationalities (national minorities) in a way that all nations and nationalities had the same rights. However, most of the ] of Yugoslavia, most of whom had collaborated during the occupation and had been recruited to German forces, were expelled towards Germany or Austria.<ref>{{cite journal |last1= Portmann|first1= Michael |date= 2010|title= Die orthodoxe Abweichung. Ansiedlungspolitik in der Vojvodina zwischen 1944 und 1947|journal= Bohemica. A Journal of History and Civilisation in East Central Europe|volume=50 |issue=1 |pages=95–120 |doi=10.18447/BoZ-2010-2474| name-list-style=vanc }}</ref> | |||

| Westerner attempts to reunite the partisans, who denied supremacy of the old government of the ], and the emigration loyal to the king, led to the ] in June 1944, however Tito was seen as a national hero by the citizens and so he gained the power in post-war independent ] state, starting as a ]. | |||

| === Yugoslav–Soviet split and the Non-Alignment Movement === | |||

| == The Second Yugoslavia == | |||

| {{Further|Tito–Stalin split|Informbiro period|Yugoslavia and the Non-Aligned Movement}} | |||

| ''Main article: ]'' | |||

| The country distanced itself from the Soviets in 1948 (cf. ] and ]) and started to build its own way to socialism under the political leadership of Josip Broz Tito.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Niebuhr |first1=Robert Edward |title=The Search for a Cold War Legitimacy: Foreign Policy and Tito's Yugoslavia |date=2018 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-9-0043-5899-7 |page=178 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=asZKDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA178}}</ref> Accordingly, the constitution was ] to replace the emphasis on ] with ] and ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Čubrilo |first1=Jasmina |editor1-last=Garcia |editor1-first=Noemi de Haro |editor2-last=Mayayo, Jesús Carrillo |editor2-first=Patricia |editor3-last=Carrillo |editor3-first=Jesús |title=Making Art History in Europe After 1945 |date=2020 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-8153-9379-5 |pages=125–128 |chapter=The Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade and Post-Revolutionary Desire}}</ref> The Communist Party was renamed to the ] and adopted ] at its ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Zimmerman |first1=William |title=Open Borders, Nonalignment, and the Political Evolution of Yugoslavia |date=2014 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-1-4008-5848-4 |page=27 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TfX_AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA27}}</ref> | |||

| On ], ] the new ] of ], modeling the ], established six constituent republics and two autonomous provinces. | |||

| All the Communist European Countries had deferred to Stalin and rejected the ] aid in 1947. Tito, at first went along and rejected the Marshall plan. However, in 1948 Tito broke decisively with Stalin on other issues, making Yugoslavia an independent communist state. Yugoslavia requested American aid. American leaders were internally divided, but finally agreed and began sending money on a small scale in 1949, and on a much larger scale 1950–53. The American aid was not part of the Marshall plan.<ref>{{cite book|author=John R. Lampe|title=Yugoslav-American Economic Relations Since World War II|url=https://archive.org/details/yugoslavamerican00lamp|url-access=registration|year=1990|publisher=Duke University Press|pages=–37|display-authors=etal|isbn=978-0822310617|access-date=17 October 2015}}</ref> | |||

| The republics were: | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| Tito criticised both ] and ] nations and, together with India and other countries, started the ] in 1961, which remained the official affiliation of the country until it dissolved.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} | |||

| and within Serbia's new reduced borders, the people of the following two regions were granted limited autonomous rights: | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| In 1974, the two provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo as well as the republics of Bosnia & Herzegovina and Montenegro were granted greater autonomy to the point that Albanian and Hungarian became nationally recognised minority languages and the Serbo-Croat of Bosnia and Montenegro altered to a form based on the speech of the local people and not on the standards of Zagreb and Belgrade. | |||

| ==SFR Yugoslavia== | |||

| ] and ] form a part of the Republic of ]. The country distanced itself from the Soviets in 1948 (cf. ] and ]) and started to build its own way to ] under strong political leadership of ]. The country criticized both ] and ] nations and, together with other countries, started the ] in 1961, which remained the official affiliation of the country until it dissolved. | |||

| {{Main|Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| On 7 April 1963, the nation changed its official name to ] and Josip Broz Tito was named ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Tito is made president of Yugoslavia for life |url=https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/tito-is-made-president-for-life |website=History.com}}</ref> In the SFRY, each republic and province had its own constitution, supreme court, parliament, president and prime minister.<ref name="US Notes">{{cite book |author1=Bureau of Public Affairs Office of Media Services |title=Background Notes |date=1976 |publisher=United States Department of State |page=4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eM8WAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA43-PA4}}</ref> At the top of the Yugoslav government were the President (Tito), the federal Prime Minister, and the federal Parliament (a collective Presidency was formed after Tito's death in 1980).<ref name="US Notes" /><ref>{{cite book |title=Post Report |date=1985 |publisher=United States Department of State |page=5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Mo2bAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA1}}</ref> Also important were the ] general secretaries for each republic and province, and the general secretary of Central Committee of the Communist Party.<ref name="US Notes" /> | |||

| Although rigorously socialist in developing her industrial base, Yugoslavia allowed a certain amount of capitalist incursions, in the spirit of pluralism. This openness to western investment, however, sowed the seeds of the federation's demise. Meanwhile, Yugoslavia enjoyed stability and peace. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the growth of Yugoslavia's gross domestic product averaged 6.1%. There was 91% literacy and an average life expectancy of 72 years. The state provided housing, health care, education, and child care. Citizens lived well on a per capita income of $3,000 a year (in 1980 dollars), with one month paid vacation, plus a year's maternity leave, if needed. Respect for workers was a central concern of government and society. | |||

| Tito was the most powerful person in the country, followed by republican and provincial premiers and presidents, and Communist Party presidents. Slobodan Penezić Krcun, Tito's chief of secret police in Serbia, fell victim to a dubious traffic incident after he started to complain about Tito's politics. Minister of the interior ] lost all of his titles and rights after a major disagreement with Tito regarding state politics. Some influential ministers in government, such as ] or ], were more important than the Prime Minister.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} | |||

| On ], ] the nation changed its official name to ] and ] was named ]. | |||

| First cracks in the tightly governed system surfaced when ] the worldwide ]. President Josip Broz Tito gradually stopped the protests by giving in to some of the students' demands and saying that "students are right" during a televised speech. However, in the following years, he dealt with the leaders of the protests by sacking them from university and Communist party posts.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Žilnik |first=Želimir |url=http://www.ghi-dc.org/files/publications/bu_supp/supp006/bus6_181.pdf |title=Yugoslavia: "Down with the Red Bourgeoisie!" |issue=1968: Memories and Legacies of a Global Revolt |journal=Bulletin of the GHI |year=2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131004072155/http://www.ghi-dc.org/files/publications/bu_supp/supp006/bus6_181.pdf |archive-date=4 October 2013}}</ref> | |||

| In SFRY, each republic and province had its own constitution, supreme court, parliament, president and prime minister. At the top of the Yugoslav government were the President (Tito), the federal Prime Minister, and the federal Parliament (a collective Presidency was formed after Tito's death in 1980). | |||

| A more severe sign of disobedience was so-called ] of 1970 and 1971, when students in Zagreb organised demonstrations for greater civil liberties and greater Croatian autonomy, followed by mass protests across Croatia.<ref name="Minahan">{{cite book |last1=Minahan |first1=James B. |title=The Complete Guide to National Symbols and Emblems |date=2009 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-0-3133-4497-8 |page=366 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jfrWCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA366}}</ref><ref name="Lalić & Prug">{{cite book |editor1-last=Lalić |editor1-first=Alenka Braček |editor2-last=Prug |editor2-first=Danica |title=Hidden Champions in Dynamically Changing Societies: Critical Success Factors for Market Leadership |date=2021 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-3-03065-451-1 |page=154 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mUIsEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA154}}</ref> The regime stifled the public protest and incarcerated the leaders, though many key Croatian representatives in the Party silently supported this cause.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Horowitz |first1=Shale |title=From Ethnic Conflict to Stillborn Reform: The Former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia |date=2005 |publisher=Texas A&M University Press |isbn=978-1-5854-4396-3 |page=150 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XjbDX9MVKWwC&pg=PA150}}</ref> As a result, a new ] was ratified in 1974, which gave more rights to the individual republics in Yugoslavia and provinces in Serbia.<ref name="Minahan" /><ref name="Lalić & Prug" /> | |||

| Also important were the ] presidents for each republic and province, and the president of Central Committee of the Communist Party. | |||

| ===Ethnic tensions and economic crisis=== | |||

| Josip Broz Tito was the most powerful person in the country, followed by republican and provincial premiers and presidents, and Communist Party presidents. A wide variety of people suffered from his disfavor. Slobodan Penezić Krcun, Tito's chief of secret police in Serbia, fell victim to a dubious traffic incident after he started to complain about Tito's politics. Minister of the Interior Aleksandar Ranković lost all of his titles and rights after a major disagreement with Tito regarding state politics. Sometimes ministers in government, such as ] or ], were more important than the Prime Minister. | |||

| After the ] took over the country at the end of WWII, nationalism was banned from being publicly promoted. Overall relative peace was retained under Tito's rule, though nationalist protests did occur, but these were usually repressed and nationalist leaders were arrested and some were executed by Yugoslav officials. However, the Croatian Spring protests in the 1970s were backed by large numbers of Croats who complained that Yugoslavia remained a Serb hegemony.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Huszka |first1=Beata |title=Secessionist Movements and Ethnic Conflict: Debate-Framing and Rhetoric in Independence Campaigns |date=2013 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781134687848 |page=68 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uTlnAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA68}}</ref> | |||

| Tito, whose home republic was Croatia, was concerned over the stability of the country and responded in a manner to appease both Croats and Serbs: he ordered the arrest of the Croatian Spring protestors while at the same time conceding to some of their demands. Following the ], Serbia's influence in the country was significantly reduced,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bell |first1=Jared O. |title=Frozen Justice: Lessons from Bosnia and Herzegovina's Failed Transitional Justice Strategy |date=2018 |publisher=Vernon Press |isbn=978-1-6227-3204-3 |page=40 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0biEDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA40}}</ref> while its autonomous provinces of ] and ] were granted greater autonomy, along with greater rights for the Albanians of Kosovo and Hungarians of Vojvodina.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-last=Paulston |editor1-first=Christina Bratt |editor2-last=Peckham |editor2-first=Donald |title=Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe |date=1998 |publisher=Multilingual Matters |isbn=978-1-8535-9416-8 |page=43 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sHB1kFCB4wYC&pg=PA43}}</ref> Both provinces were afforded much of the same status as the six republics of Yugoslavia, though they could not secede.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ker-Lindsay |first1=James |title=The Foreign Policy of Counter Secession: Preventing the Recognition of Contested States |date=2012 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=9780199698394 |page=33 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4PwmeRG9QsUC&pg=PA33}}</ref> Vojvodina and Kosovo formed the provinces of the ] but also formed part of the federation, which led to the unique situation in which ] did not have its own assembly but a joint assembly with its provinces represented in it. ] and ] became nationally recognised minority languages, and the Serbo-Croat of Bosnia and Montenegro altered to a form based on the speech of the local people and not on the standards of Zagreb and Belgrade. In Slovenia the recognized minorities were Hungarians and Italians.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} | |||

| The suppression of national identities escalated with the so-called ] of 1970-71, when students in Zagreb organized demonstrations for greater civil liberties and greater Croatian autonomy. The regime stifled the public protest and incarcerated the leaders, but many key Croatian representatives in the Party silently supported this cause, so a new ] was ratified in 1974 that gave more rights to the individual republics and provinces. | |||

| The fact that these autonomous provinces held the same voting power as the republics but unlike other republics could not legally separate from Yugoslavia satisfied Croatia and Slovenia, but in Serbia and in the new autonomous province of Kosovo, reaction was different. Serbs saw the new constitution as conceding to Croat and ethnic Albanian nationalists.<ref name="Malley-Morrison">{{cite book |editor1-last=Malley-Morrison |editor1-first=Kathleen |title=State Violence and the Right to Peace: An International Survey of the Views of Ordinary People, Volume 1 |date=2009 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-0-2759-9652-9 |page=28 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hV-y4BNWTt0C&pg=RA1-PA28}}</ref> Ethnic Albanians in Kosovo saw the creation of an autonomous province as not being enough, and demanded that Kosovo become a constituent republic with the right to separate from Yugoslavia. This created tensions within the Communist leadership, particularly among Communist Serb officials who viewed the 1974 constitution as weakening Serbia's influence and jeopardising the unity of the country by allowing the republics the right to separate.<ref name="Malley-Morrison" /> | |||

| === Ethnic tensions and economic crisis === | |||

| The post-World War Two Yugoslavia was in many respects a model of how to build a multinational state. The Federation was constructed against a double background: an inter-war Yugoslavia which had been dominated by Serbian ruling class; and a war-time slaughter in which the Nazis made use of the earlier Serbian oppression to use Croatian fascism for barbarous slaughter and also exploited anti-Serb sentiment amongst the Kosovo Albanian - and some elements in the Bosnian Muslim - population to bolster their rule. | |||

| According to official statistics, from the 1950s to the early 1980s, Yugoslavia was among the fastest growing countries, approaching the ranges reported in South Korea and other countries undergoing an ].<ref name="Baten">{{cite book |editor1-last=Baten |editor1-first=Joerg |title=A History of the Global Economy |date=2016 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-1071-0470-9 |page=64 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gmOKCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA64}}</ref> The unique socialist system in Yugoslavia, where factories were ]s and decision-making was less centralized than in other socialist countries, may have led to the stronger growth. However, even if the absolute value of the growth rates was not as high as indicated by the official statistics, both the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia were characterized by surprisingly high growth rates of both income and education during the 1950s.<ref name="Baten" /> | |||

| There had been one structural element in the post-World War II Yugoslav state's stability: the joint concern of the USSR and the USA to maintain the integrity of Yugoslavia as a neutral state on the frontiers of the super-power confrontation in Europe. | |||

| The period of European growth ended after the oil price shock in 1970s. Following that, an economic crisis erupted in Yugoslavia due to disastrous economic policies such as borrowing vast amounts of Western capital to fund growth through exports.<ref name="Baten" /> At the same time, Western economies went into recession, decreasing demand for Yugoslav imports thereby creating a large debt problem.<ref>{{Cite web |title=YUGOSLAVIA'S BALANCE OF PAYMENTS: IN THE BLACK THOUGH NOT FOR LONG |url=https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP85T00875R001700050006-9.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| The economic crisis was the product of disastrous errors by Yugoslav governments in the 1970s, borrowing vast amounts of Western capital in order to fund growth through exports. Western economies then entered recession, blocked Yugoslav exports and created a huge debt problem. The Yugoslav government then accepted the IMF's conditionalities which shifted the burden of the crisis onto the Yugoslav working class. Simultaneously, strong social groups emerged within the Yugoslav Communist Party, allied to Western business, banking and state interests and began pushing towards neoliberalism, to the delight of the US. It was the Reagan administration which, in 1984, had adopted "Shock Therapy" proposal to push Yugoslavia towards a capitalist restoration. | |||

| In 1989, 248 firms were declared bankrupt or were liquidated and 89,400 workers were laid off according to official sources{{who|date=September 2020}}. During the first nine months of 1990 and directly following the adoption of the IMF programme, another 889 enterprises with a combined work-force of 525,000 workers suffered the same fate. In other words, in less than two years "the trigger mechanism" (under the Financial Operations Act) had led to the layoff of more than 600,000 workers out of a total industrial workforce of the order of 2.7 million.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Eade |first1=Deborah |title=From Conflict to Peace in a Changing World: Social Reconstruction in Times of Transition |date=1998 |publisher=Oxfam |isbn=978-0-8559-8395-6 |page=40}}</ref> An additional 20% of the work force, or half a million people, were not paid wages during the early months of 1990 as enterprises sought to avoid bankruptcy.<ref name="Chossudovsky">{{cite journal |last1=Chossudovsky |first1=Michel |title=Dismantling Former Yugoslavia: Recolonising Bosnia |journal=Economic and Political Weekly |date=1996 |volume=31 |issue=9 |pages=521–525 |jstor=4403857 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/4403857}}</ref> The largest concentrations of bankrupt firms and lay-offs were in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia and Kosovo. Real earnings were in a free fall and social programmes collapsed; creating within the population an atmosphere of social despair and hopelessness.<ref name="Chossudovsky" /> This was a critical turning point in the events to follow.{{citation needed|date=September 2020}} | |||

| This, naturally, undermined a central pillar of the state: the socialist link between the Communist Party and the working class. The forms and effects of this varied in different parts of Yugoslavia. First in Kosovo in 1981, where the links between Yugoslav communism and the population had always been weakest and where the economic crisis was most intense, there was an uprising demanding full republican status for Kosovo, as well as unification with Albania. | |||

| ==Breakup== | |||

| In 1989 Jeffrey Sachs was in Yugoslavia helping the Federal government under Ante Markovic prepare the IMF/World Bank shock therapy package, which was then introduced in 1990 just at the time when the crucial parliamentary elections were being held in the various republics. | |||

| {{Main|Breakup of Yugoslavia}} | |||

| ] | |||

| After Tito's death on 4 May 1980, ] grew in Yugoslavia. The legacy of the ] threw the system of decision-making into a state of paralysis, made all the more hopeless as the conflict of interests became irreconcilable. The Albanian majority in Kosovo demanded the status of a republic in the ] while Serbian authorities suppressed this sentiment and proceeded to reduce the province's autonomy.<ref>John B. Allcock, et al. eds., ''Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia: An Encyclopedia'' (1998)</ref> | |||

| One aspect of Yugoslavia's Shock Therapy programme was both unique within the region and of great political importance in 1989-90. The bankruptcy law to liquidate state enterprises was enacted in the 1989 Financial Operations Act which required that if an enterprise was insolvent for 30 days running, or for 30 days within a 45 day period, it had to settle with its creditors either by giving them ownership or by being liquidated, in which case workers would be sacked, normally without severance payments. In 1989, according to official sources, 248 firms were declared bankrupt or were liquidated and 89,400 workers were laid off. During the first nine months of 1990 directly following the adoption of the IMF programme, another 889 enterprises with a combined work-force of 525,000 workers suffered the same fate. In other words, in less than two years "the trigger mechanism" (under the Financial Operations Act) had led to the lay off of more than 600,000 workers out of a total industrial workforce of the order of 2.7 million. A further 20% of the work force, or half a million people, were not paid wages during the early months of 1990 as enterprises sought to avoid bankruptcy. The largest concentrations of bankrupt firms and lay-offs were in Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia and Kosovo. Real earnings were in a free fall, social programmes had collapsed creating within the population an atmosphere of social despair and hopelessness. This was an critical turning point in the Yugoslav tragedy. | |||

| In 1986, the ] drafted a memorandum addressing some burning issues concerning the position of Serbs as the most numerous people in Yugoslavia. The largest Yugoslav republic in territory and population, Serbia's influence over the regions of Kosovo and Vojvodina was reduced by the 1974 Constitution. Because its two autonomous provinces had de facto prerogatives of full-fledged republics, Serbia found that its hands were tied, for the republican government was restricted in making and carrying out decisions that would apply to the provinces. Since the provinces had a vote in the Federal Presidency Council (an eight-member council composed of representatives from the six republics and the two autonomous provinces), they sometimes even entered into coalitions with other republics, thus outvoting Serbia. Serbia's political impotence made it possible for others to exert pressure on the 2 million Serbs (20% of the total Serbian population) living outside Serbia.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} | |||

| Markovic in the Spring of 1990 was by far the most popular politician not only in Yugoslavia as a whole but in each of its constituent republics. He should have been able to rally the population for Yugoslavism against the particularist nationalisms of Milosevic in Serbia or Tudjman in Croatia and he should have been able to count on the obedience of the armed forces. He was supported by 83% of the population in Croatia, by 81% in Serbia and by 59% in Slovenia and by 79% in Yugoslavia as a whole. This level of support showed how much of the Yugoslav population remained strongly committed to the state's preservation. | |||

| After Tito's death, Serbian communist leader ] began making his way toward the pinnacle of Serbian leadership.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=The World Transformed 1945 to the Present|last=Hunt|first=Michael|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2014|isbn=978-0-19-937102-0|location=New York|pages=522}}</ref> Milošević sought to restore pre-1974 Serbian sovereignty. Other republics, especially Slovenia and Croatia, denounced his proposal as a revival of ]n hegemonism. Through a series of moves known as the "]", Milošević succeeded in reducing the autonomy of ] and of ] and Metohija,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Roberts |first1=Elizabeth |title=Realm of the Black Mountain: A History of Montenegro |date=2007 |publisher=Cornell University Press |isbn=9780801446016 |page=432 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=G62MCZ3RiIEC&pg=PA432}}</ref> but both entities retained a vote in the Yugoslav Presidency Council. The very instrument that reduced Serbian influence before was now used to increase it: in the eight-member Council, Serbia could now count on four votes at a minimum: Serbia proper, then-loyal Montenegro, Vojvodina, and Kosovo.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Djokić |first1=Dejan |title=A Concise History of Serbia |date=2023 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=9781009308656 |page=461 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aROpEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA461}}</ref> | |||

| But Markovic had coupled his Yugoslavism with the IMF Shock Therapy programme and EC conditionality and it was this which gave the separatists in the North West and the nationalists in Serbia their opening. The appeal of the separatists in Slovenia and Croatia to their electorates involved offering to repudiate the Markovic-IMF austerity and by doing so help their republics prepare to leave Yugoslavia altogether and 'join Europe'. The appeal of Milosevic in Serbia was to the fact that the West was acting against the Serbian people's interests. And these appeals worked. In every republic, beginning with Slovenia and Croatia in the Spring, governments ignored the monetary restrictions of Markovic's stabilisation programme in order to win votes. | |||

| As a result of these events, ] miners in ] organised the ], which dovetailed into an ethnic conflict between the Albanians and the non-Albanians in the province. At around 80% of the ], ethnic-Albanians were the majority. With Milošević gaining control over Kosovo in 1989, the original residency changed drastically leaving only a minimum number of Serbians in the region.<ref name=":0" /> The number of Serbs in Kosovo was quickly declining for several reasons, among them the ever-increasing ethnic tensions and subsequent emigration from the area.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Howe |first1=Marvin |title=Exodus of Serbians Stirs Province in Yugoslavia |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1982/07/12/world/exodus-of-serbians-stirs-province-in-yugoslavia.html |work=The New York Times |date=12 July 1982}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Kingsbury |first1=Damien |title=Separatism and the State |date=2021 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=9781000368703 |page=84 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zroYEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA84}}</ref> | |||

| After winning elections, they worked hard to break up the country. But the US government as a whole opted for the priority of the Shock Therapy programme over Yugoslav cohesion. Thus was the internal dynamic towards the Yugoslav collapse into civil war decisively accelerated. The only European states which did have a strategic interest in the Yugoslav theatre tended to want to break it up. It would be wrong, of course, to suggest that there were no other, specifically Yugoslav, structural flaws which helped to generate the collapse. Many would argue that the decentralised Market Socialism was a disastrous experiment for a state in Yugoslavia's geopolitical situation. The 1974 Constitution, though better for the Kosovar Albanians, gave too much to the republics, crippling the institutional and material power of the Federal government. Tito's authority substituted for this weakness until his death in 1980, after which the state and Communist Party became increasingly paralysed and thrown into crisis. | |||

| Meanwhile, ], under the presidency of ], and ] supported the Albanian miners and their struggle for formal recognition. Initial strikes turned into widespread demonstrations demanding a Kosovar republic. This angered Serbia's leadership which proceeded to use police force and later, federal police troops to restore civil order.<ref>{{cite book|last=Meier|first=Viktor|title=Yugoslavia: a history of its demise|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1oYiKrmTL7EC&pg=PA84|year=1999|publisher=Routledge|isbn=9780415185967|pages=84–85}}</ref> | |||

| === Breakup === | |||

| {{NPOV-section}} | |||

| {{wikify-date|June 2006}} | |||

| In January 1990, the extraordinary 14th Congress of the ] was convened, where the Serbian and Slovenian delegations argued over the future of the League of Communists and Yugoslavia. The Serbian delegation, led by Milošević, insisted on a policy of "one person, one vote" which would empower the plurality population, the ]. In turn, the Slovenian delegation, supported by Croats, sought to reform Yugoslavia by devolving even more power to republics, but were voted down. As a result, the Slovene and Croatian delegations left the Congress and the all-Yugoslav Communist party was dissolved.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Borgeryd |first1=Anna J. |title=Managing Intercollective Conflict: Prevailing Structures and Global Challenges |date=1999 |publisher=Universal-Publishers |isbn=9781581120431 |page=213 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PmrClo4yBtQC&pg=PA213}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Athanasiou |first1=Athena |title=Agonistic Mourning: Political Dissidence and the Women in Black |date=2017 |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |isbn=9781474420174 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kDZYDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT55}}</ref> | |||

| After Tito's death in 1980, ethnic tensions grew in Yugoslavia. The legacy of the Constitution of 1974 threw the system of decision-making into a state of paralysis, all the more hopeless as the conflict of interests between the republics had become irreconcilable. The constitutional crisis that inevitably followed played in favour of Slovenia and Croatia and their strongly expressed demands for looser ties within Federation. | |||

| The constitutional crisis that inevitably followed resulted in a rise of nationalism in all republics: Slovenia and Croatia voiced demands for looser ties within the federation.{{cn|date=August 2024}} Following the fall of communism in Eastern Europe, each of the republics held multi-party elections in 1990. Slovenia and Croatia held the elections in April since their communist parties chose to cede power peacefully. Other Yugoslav republics—especially Serbia—were more or less dissatisfied with the democratisation in two of the republics and proposed different sanctions (e.g. Serbian "customs tax" for Slovene products) against the two, but as the year progressed, other republics' communist parties saw the inevitability of the democratisation process.{{cn|date=August 2024}} In December, as the last member of the federation, Serbia held parliamentary elections confirming the rule of former communists in the republic.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} | |||

| The collapse of Yugoslavia was the result of both internal and external factors. Assigning comparative weight to the external as against the internal factors in the generalised crisis that shook Yugoslavia in 1990-1991 is a complex matter. But without understanding the roles of the Western powers in helping to produce and channel the crisis, it is difficult to understand the disintegration of Yugoslavia. The fundamental cause of the Yugoslav collapse was an economic crisis. This was then used by social groups in Yugoslavia and in the West to undermine the collectivised core of the economy and push Yugoslavia towards a capitalist restoration. | |||

| Slovenia and Croatia elected governments oriented towards greater autonomy of the republics (under ] and ], respectively).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Moore |first1=Adam |title=Peacebuilding in Practice: Local Experience in Two Bosnian Towns |date=2013 |publisher=Cornell University Press |isbn=9780801469558 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ac8OAAAAQBAJ&pg=PT41}}</ref> Serbia and Montenegro elected candidates who favoured Yugoslav unity.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} The Croat quest for independence led to large Serb communities within Croatia rebelling and trying to secede from the Croat republic. Serbs in Croatia would not accept the status of a national minority in a sovereign Croatia since they would be demoted from the status of a constituent nation.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lukic |first1=Renéo |last2=Lynch |first2=Allen |title=Europe from the Balkans to the Urals: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union |date=1996 |publisher=SIPRI |isbn=9780198292005 |page=277 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WPhhLfp8huIC&pg=PA277}}</ref> | |||