| Revision as of 03:31, 29 December 2013 editBeyond My Ken (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, IP block exemptions, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers263,268 edits →References← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:31, 28 October 2024 edit undoParadoctor (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers33,524 editsm →top: tzpo | ||

| (687 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Gland of the male reproductive system}} | |||

| {{about||the female prostate gland|Skene's gland|the "prostrate" body position|Prostration}} | |||

| {{pp-pc}} | |||

| {{Infobox Anatomy | |||

| {{Hatnote group| | |||

| | Name = Prostate | |||

| {{For|the journal|The Prostate}} | |||

| | Latin = prostata | |||

| {{Distinguish|text=]}} | |||

| | Image = Prostatelead.jpg | |||

| }} | |||

| | GraySubject = 263 | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| | GrayPage = 1251 | |||

| {{Infobox anatomy | |||

| | Caption = Male Anatomy | |||

| | |

| Name = Prostate | ||

| | Latin = prostata | |||

| | Caption2 = Prostate with ] and ], viewed from in front and above. | |||

| | |

| Greek = προστάτης | ||

| | |

| Image = Prostatelead.jpg | ||

| | Caption = | |||

| | Artery = ], ], and ] | |||

| | Precursor = ]s of the ], ] | |||

| | Vein = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | |

| System = ] | ||

| | |

| Artery = ], ], and ] | ||

| | Vein = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | Precursor = ] | |||

| | Nerve = ] | |||

| | MeshName = Prostate | |||

| | Lymph = ] | |||

| | MeshNumber = A05.360.444.575 | |||

| | Dorlands = seven/000087175 | |||

| | DorlandsID = Prostate | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''prostate''' (from ] προστάτης, ''prostates'', literally "one who stands before", "protector", "guardian"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://etymonline.com/?term=prostate|title=Prostate|work=Online Etymology Dictionary|first=Douglas|last=Harper|accessdate=2013-11-03}}</ref>) is a compound ] ] of the ]s.<ref name=VB>{{cite book |author=Romer, Alfred Sherwood|author2=Parsons, Thomas S.|year=1977 |title=The Vertebrate Body |publisher=Holt-Saunders International |location= Philadelphia, PA|page= 395|isbn= 0-03-910284-X}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last = Tsukise | first = A. | title = Complex carbohydrates in the secretory epithelium of the goat prostate | doi=10.1007/BF01003614 | year = 1984 | last2 = Yamada | first2 = K. | journal = The Histochemical Journal | volume = 16 | issue = 3 | pages = 311–9 | pmid = 6698810}}</ref> It differs considerably among species ], ]ly, and ]. | |||

| The '''prostate''' is an ] of the ] and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between ] and ]. It is found in all male mammals.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Vásquez |first=Bélgica |date=2014-03-01 |title=Morphological Characteristics of Prostate in Mammals |url=https://revistas.uautonoma.cl/index.php/ijmss/article/view/248 |journal=International Journal of Medical and Surgical Sciences |language=en |volume=1 |issue=1 |pages=63–72 |doi=10.32457/ijmss.2014.010 |issn=0719-532X |doi-access=free}}</ref> It differs between species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically. Anatomically, the prostate is found below the ], with the ] passing through it. It is described in ] as consisting of lobes and in ] by zone. It is surrounded by an elastic, fibromuscular capsule and contains glandular tissue, as well as ]. | |||

| In 2002, female paraurethral glands, or ]s, were officially renamed the female prostate by the ].<ref name=seattletimes>{{cite news |url=http://seattletimes.com/html/health/2002865111_carnalknowledge15.html |title=The Seattle Times: Health: Gee, women have ... a prostate? |publisher=seattletimes.nwsource.com |accessdate=2013-11-03 | first=Faye | last=Flam | date=2006-03-15}}</ref> | |||

| The prostate produces and contains fluid that forms part of ], the substance emitted during ] as part of the male ]. This prostatic fluid is slightly ], milky or white in appearance. The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the ], prolonging the lifespan of ]. The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first part of ejaculate, together with most of the sperm, because of the action of ] tissue within the prostate. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid, those in prostatic fluid have better ], longer survival, and better protection of genetic material. | |||

| ==Structure== | |||

| ] of benign prostatic glands with ]. ].]] | |||

| ] (black butterfly-like shape) and hyperplastic prostate (BPH) visualized by ] technique]] | |||

| A healthy ] prostate is classically said to be slightly larger than a ]. The mean weight of the normal prostate in adult males is about 11 grams, usually ranging between 7 and 16 grams.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Leissner KH, Tisell LE |title=The weight of the human prostate |journal=Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=137–42 |year=1979 |pmid=90380 |doi= 10.3109/00365597909181168}}</ref> It surrounds the ] just below the ] and can be felt during a ]. | |||

| Disorders of the prostate include ], ], ], and ]. The word ''prostate'' is derived from ] {{transl|grc|prostátēs}} ({{lang|grc|προστάτης}}), meaning "one who stands before", "protector", "guardian", with the term originally used to describe the ]. | |||

| The secretory epithelium is mainly pseudostratified, comprising tall columnar cells and basal cells which are supported by a fibroelastic stroma containing randomly orientated smooth muscle bundles. The epithelium is highly variable and areas of low cuboidal or squamous epithelium are also present, with transitional epithelium in the distal regions of the longer ducts.<ref name="titleAn overview of Prostate Development">{{cite web|url=http://www.ana.ed.ac.uk/database/prosbase/prosdev.html |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20030430000050/http://www.ana.ed.ac.uk/database/prosbase/prosdev.html |archivedate=2003-04-30 |title=Prostate Gland Development|accessdate=2011-08-03 |work=ana.ed.ac.uk}}</ref> | |||

| Within the prostate, the urethra coming from the bladder is called the ] and merges with the two ]s. | |||

| ==Structure== | |||

| The prostate can be divided in two ways: by zone, or by lobe.<ref name="titleInstant Anatomy - Abdomen - Vessels - Veins - Prostatic plexus">{{cite web |url=http://www.instantanatomy.net/abdomen/vessels/vprostaticplexus.html |title=Instant Anatomy – Abdomen – Vessels – Veins – Prostatic plexus |accessdate=2007-11-23 |work=}}</ref> It does not have a capsule, rather an integral fibromuscular band surrounds it.<ref>{{cite pmid|18828961 }}</ref> It is sheathed in the muscles of the pelvic floor, which contract during the ejaculatory process. | |||

| The prostate is a ] of the ]. In adults, it is about the size of a ],<ref name="Young-2013">{{Cite book |last=Young |first=Barbara |title=Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas. |last2=O'Dowd |first2=Geraldine |last3=Woodford |first3=Phillip |date=2013 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=9780702047473 |edition=6th |location=Philadelphia |pages=347–8}}</ref> and has an average weight of about {{convert|11|g}}, usually ranging between {{convert|7|and(-)|16|g}}.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Leissner KH, Tisell LE |year=1979 |title=The weight of the human prostate |journal=Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=137–42 |doi=10.3109/00365597909181168 |pmid=90380}}</ref> The prostate is located in the pelvis. It sits below the ] and surrounds the ]. The part of the urethra passing through it is called the ], which joins with the two ]s.<ref name="Young-2013" /> The prostate is covered in a surface called the ''prostatic capsule'' or ''prostatic fascia''.<ref name="Standring-2016" /> | |||

| The internal structure of the prostate has been described using both lobes and zones.<ref name="Goddard-2019">{{Cite journal |last=Goddard |first=Jonathan Charles |date=January 2019 |title=The history of the prostate, part one: say what you see |journal=Trends in Urology & Men's Health |language=en |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=28–30 |doi=10.1002/tre.676 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Young-2013" /> Because of the variation in descriptions and definitions of lobes, the zone classification is used more predominantly.<ref name="Young-2013" /> | |||

| ===Zones=== | |||

| The "zone" classification is more often used in ]. The idea of "zones" was first proposed by McNeal in 1968. McNeal found that the relatively homogeneous cut surface of an adult prostate in no way resembled "lobes" and thus led to the description of "zones".<ref>{{cite journal|author=Myers, Robert P|pmid=10797630|year=2000|title=Structure of the adult prostate from a clinician's standpoint|volume=13|issue=3|pages=214–5|doi=10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(2000)13:3<214::AID-CA10>3.0.CO;2-N|journal=Clinical anatomy}}</ref> | |||

| The prostate has been described as consisting of three or four zones.<ref name="Young-2013" /><ref name="Standring-2016">{{Cite book |title=Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice |year=2016 |isbn=9780702052309 |editor-last=Standring, Susan |edition=41st |location=Philadelphia |pages=1266–1270 |chapter=Prostate |oclc=920806541}}</ref> Zones are more typically able to be seen on ], or in ], such as ] or ].<ref name="Young-2013" /><ref name="Goddard-2019" /> | |||

| The prostate gland has four distinct glandular regions, two of which arise from different segments of the prostatic urethra: | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable plainrowheaders" | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! scope="col" | Name | |||

| | '''Name''' || '''Fraction of gland''' || '''Description''' | |||

| ! scope="col" | Fraction of adult gland<ref name="Young-2013" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="col" | Description | |||

| | Peripheral zone (PZ) || Up to 70% in young men || The sub-capsular portion of the posterior aspect of the prostate gland that surrounds the distal ]. It is from this portion of the gland that ~70–80% of ] originate.<ref name="urologymatch1">. Urology Match. Www.urologymatch.com. Web. 14 June 2010.</ref><ref name="prostate-cancer1"> Prostate Cancer Treatment Guide. Web. 14 June 2010.</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | Peripheral zone (PZ) | |||

| | Central zone (CZ) || Approximately 25% normally || This zone surrounds the ]. The central zone accounts for roughly 2.5% of prostate cancers although these cancers tend to be more aggressive and more likely to invade the seminal vesicles.<ref name="pmid18343454">{{cite journal |author=Cohen RJ, Shannon BA, Phillips M, Moorin RE, Wheeler TM, Garrett KL |title=Central zone carcinoma of the prostate gland: a distinct tumor type with poor prognostic features |journal=The Journal of Urology |volume=179 |issue=5 |pages=1762–7; discussion 1767 |year=2008|pmid=18343454 |doi=10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.017 }}</ref> | |||

| | style="text-align: center;" | 70% | |||

| |- | |||

| | The back of the gland that surrounds the distal urethra and lies beneath the capsule. About 70–80% of ] originate from this zone of the gland.<ref name="Urology Match"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101015014554/http://www.urologymatch.com/ProstateAnatomy.htm |date=2010-10-15 }}. Urology Match. Www.urologymatch.com. Web. 14 June 2010.</ref><ref name="PCTG"> Prostate Cancer Treatment Guide. Web. 14 June 2010.</ref> | |||

| | Transition zone (TZ) || 5% at puberty || ~10–20% of prostate cancers originate in this zone. The transition zone surrounds the proximal urethra and is the region of the prostate gland that grows throughout life and is responsible for the disease of ]. (2)<ref name="urologymatch1"/><ref name="prostate-cancer1"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | Central zone (CZ) | |||

| | Anterior fibro-muscular zone (or stroma) || Approximately 5% || This zone is usually devoid of glandular components, and composed only, as its name suggests, of ] and ]. | |||

| | style="text-align: center;" | 20% | |||

| | This zone surrounds the ejaculatory ducts.<ref name="Young-2013" /> The central zone accounts for roughly 2.5% of prostate cancers; these cancers tend to be more aggressive and more likely to invade the seminal vesicles.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Cohen RJ, Shannon BA, Phillips M, Moorin RE, Wheeler TM, Garrett KL |year=2008 |title=Central zone carcinoma of the prostate gland: a distinct tumor type with poor prognostic features |journal=The Journal of Urology |volume=179 |issue=5 |pages=1762–7; discussion 1767 |doi=10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.017 |pmid=18343454 |s2cid=52417682}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | Transition zone (TZ) | |||

| | style="text-align: center;" | 5% | |||

| | The transition zone surrounds the proximal urethra.<ref name="Young-2013" /> ~10–20% of prostate cancers originate in this zone. It is the region of the prostate gland that grows throughout life and causes the disease of ].<ref name="Urology Match" /><ref name="PCTG" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="row" | Anterior fibro-muscular zone (or ]) | |||

| | {{N/A}} | |||

| | This area, not always considered a zone,<ref name="Standring-2016" /> is usually devoid of glandular components and composed only, as its name suggests, of ] and ].<ref name="Young-2013" /> | |||

| |} | |} | ||

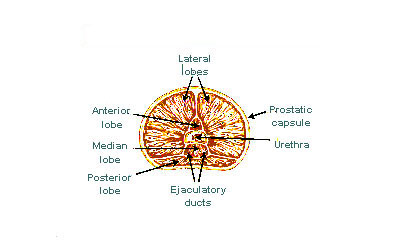

| The "lobe" classification describes lobes that, while originally defined in the fetus, are also visible in gross anatomy, including dissection and when viewed endoscopically.<ref name="Goddard-2019" /><ref name="Standring-2016" /> The five lobes are the anterior lobe or isthmus, the posterior lobe, the right and left lateral lobes, and the middle or median lobe. | |||

| ===Lobes=== | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="175px"> | |||

| The "lobe" classification is more often used in anatomy. | |||

| File:Illu prostate lobes.jpg|Lobes of prostate | |||

| File:Prostate zones.png|Zones of prostate | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| Inside of the prostate, adjacent and parallel to the prostatic urethra, there are two longitudinal muscle systems. On the front side (]) runs the urethral ] (''musculus dilatator urethrae''), on the backside (]) runs the muscle switching the urethra into the ejaculatory state (''musculus ejaculatorius'').<ref name="Schünke-2012">Michael Schünke, Erik Schulte, Udo Schumacher: ''PROMETHEUS Innere Organe. LernAtlas Anatomie'', vol 2: ''Innere Organe'', Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart/Germany 2012, {{ISBN|9783131395337}}, p. 298, .</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| | Anterior lobe (or isthmus) || roughly corresponds to part of transitional zone | |||

| |- | |||

| | Posterior lobe || roughly corresponds to peripheral zone | |||

| |- | |||

| | Lateral lobes || spans all zones | |||

| |- | |||

| | Median lobe (or middle lobe) || roughly corresponds to part of central zone | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Blood and lymphatic vessels=== | |||

| ==Physiology== | |||

| The prostate receives blood through the ], ], and ]. These vessels enter the prostate on its outer {{wt|en|posterior}} surface where it meets the bladder, and travel forward to the apex of the prostate.<ref name="Standring-2016" /> Both the inferior vesical and the middle rectal arteries often arise together directly from the ]. On entering the bladder, the inferior vesical artery splits into a urethral branch, supplying the urethral prostate; and a capsular branch, which travels around the capsule and has smaller branches, which perforate into the prostate.<ref name="Standring-2016" /> | |||

| The veins of the prostate form a network – the ], primarily around its front and outer surface.<ref name="Standring-2016" /> This network also receives blood from the ], and is connected via branches to the ] and ].<ref name="Standring-2016" /> Veins drain into the ] and then ]s.<ref name="Standring-2016" /> | |||

| ===Function=== | |||

| The function of the prostate is to secrete a slightly alkaline fluid, milky or white in appearance,<ref name="http://ajplegacy.physiology.org">{{cite journal|journal=Am J Physiol |year=1942 |volume=136|issue=3|pages= 467–473 |url=http://ajplegacy.physiology.org/cgi/pdf_extract/136/3/467 |title=Chemical composition of human semen and of the secretions of the prostate and seminal vehicles | |||

| }}</ref> that usually constitutes 50–75% of the volume of the ] along with ] and ] fluid.<ref name="http://ajplegacy.physiology.org"/> Semen is made alkaline overall with the secretions from the other contributing glands, including, at least, the seminal vesicle fluid. The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm. The alkalinization of semen is primarily accomplished through secretion from the seminal vesicles.<ref> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.umc.sunysb.edu/urology/male_infertility/SEMEN_ANALYSIS.html | |||

| |title=Semen analysis | |||

| |publisher=www.umc.sunysb.edu | |||

| |accessdate=2009-04-28 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first ] fractions, together with most of the spermatozoa. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid, those expelled in prostatic fluid have better ], longer survival and better protection of the genetic material. | |||

| The lymphatic drainage of the prostate depends on the positioning of the area. Vessels surrounding the ], some of the vessels in the seminal vesicle, and a vessel from the posterior surface of the prostate drain into the ].<ref name="Standring-2016" /> Some of the seminal vesicle vessels, prostatic vessels, and vessels from the anterior prostate drain into ].<ref name="Standring-2016" /> Vessels of the prostate itself also drain into the ] and ].<ref name="Standring-2016" /> | |||

| The prostate also contains some ]s that help expel semen during ]. | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="175px"> | |||

| ====Male sexual response==== | |||

| File:Internal_iliac_branches.PNG|Imaging showing the ], ] and ] arising from the ]. | |||

| {{main|Prostate massage}} | |||

| File:Gray611.png|Image showing the ] and their positions around the external iliac artery and ] | |||

| During male ], sperm is transmitted from the ductus deferens into the male urethra via the ejaculatory ducts, which lie within the prostate gland. It is possible for men to achieve ] solely through stimulation of the prostate gland, such as prostate massage or receptive ].<ref name="Prostate/Hot spot">{{cite web|title= The male hot spot — Massaging the prostate|publisher=]|date=2002-09-27 (Last Updated/Reviewed on 2008-03-28)|accessdate=2010-04-21|url=http://goaskalice.columbia.edu/male-hot-spot-massaging-prostate }}</ref><ref name="Rosenthal">{{cite book |first=Martha |last= Rosenthal| title = Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society | publisher =]|year = 2012|pages=133–135|accessdate = September 17, 2012| isbn = 0618755713|url =http://books.google.com/books?id=d58z5hgQ2gsC&pg=PT153}}</ref><ref name="Answer">{{cite book|title=The Orgasm Answer Guide|isbn = 0-8018-9396-8|publisher=JHU Press|year=2009|pages=108–109|accessdate=6 November 2011|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Kkts3AX9QVAC&pg=PA108|author =Komisaruk, Barry R.; Whipple, Beverly; Nasserzadeh, Sara and Beyer-Flores, Carlos }}</ref> | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === |

===Microanatomy=== | ||

| ] of benign prostatic glands with ]. ].]] | |||

| Prostatic secretions vary among species. They are generally composed of simple sugars and are often slightly ]ic. In human prostatic secretions, the protein content is less than 1% and includes ]s, ], ], and ]. The secretions also contain ] with a concentration 500–1,000 times the concentration in blood. | |||

| The prostate consists of glandular and ].<ref name="Young-2013" /> Tall ] form the lining (the ]) of the glands.<ref name="Young-2013" /> These form one layer or may be ].<ref name="Standring-2016" /> The epithelium is highly variable and areas of low ] or ] cells can also be present, with transitional epithelium in the outer regions of the longer ducts.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Prostate Gland Development |url=http://www.ana.ed.ac.uk/database/prosbase/prosdev.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030430000050/http://www.ana.ed.ac.uk/database/prosbase/prosdev.html |archive-date=2003-04-30 |access-date=2011-08-03 |website=ana.ed.ac.uk}}</ref> ]s surround the luminal epithelial cells in benign glands. The glands are formed as many follicles, which drain into canals and subsequently 12–20 main ducts, These in turn drain into the urethra as it passes through the prostate.<ref name="Standring-2016" /> There are also a small amount of flat cells, which sit next to the basement membranes of glands, and act as stem cells.<ref name="Young-2013" /> | |||

| The connective tissue of the prostate is made up of fibrous tissue and ].<ref name="Young-2013" /> The fibrous tissue separates the gland into lobules.<ref name="Young-2013" /> It also sits between the glands and is composed of randomly orientated smooth-muscle bundles that are continuous with the bladder.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Prostate |url=https://webpath.med.utah.edu/TUTORIAL/PROSTATE/PROSTATE.html |access-date=2019-11-17 |website=webpath.med.utah.edu}}</ref> | |||

| Over time, thickened secretions called ] accumulate in the gland.<ref name="Young-2013" /> | |||

| <gallery mode="packed"> | |||

| File:Prostatehistology.jpg|Microscopic glands of the prostate | |||

| File:Prostate gland microanatomy.png|Microanatomy of a prostatic gland, showing both luminal cells and surrounding basal cells. H&E stain. | |||

| File:Histology of normal prostate.jpg|Histology of normal prostate, H&E stain, with benign features: Glands are rounded to irregularly branching, with an inner layer of epithelial cells surrounded by an outer layer of basal cells. They are surrounded by ample stroma. | |||

| File:Histology of prostate atrophy.jpg|Histology of prostate with gradually increasing simple atrophy from left to right, H&E stain. Crowding and angulation may mimic that of adenocarcinoma, but there is nuclear basophilia rather than atypia, and occasional basal cells can still be seen. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Gene and protein expression=== | |||

| {{Further|Bioinformatics#Gene and protein expression}} | |||

| About 20,000 ] are expressed in human cells and almost 75% of these genes are expressed in the normal prostate.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The human proteome in prostate – The Human Protein Atlas |url=https://www.proteinatlas.org/humanproteome/prostate |access-date=2017-09-26 |website=www.proteinatlas.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Uhlén |first=Mathias |last2=Fagerberg |first2=Linn |last3=Hallström |first3=Björn M. |last4=Lindskog |first4=Cecilia |last5=Oksvold |first5=Per |last6=Mardinoglu |first6=Adil |last7=Sivertsson |first7=Åsa |last8=Kampf |first8=Caroline |last9=Sjöstedt |first9=Evelina |date=2015-01-23 |title=Tissue-based map of the human proteome |journal=Science |volume=347 |issue=6220 |pages=1260419 |doi=10.1126/science.1260419 |issn=0036-8075 |pmid=25613900 |s2cid=802377}}</ref> About 150 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the prostate, with about 20 genes being highly prostate specific.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=O'Hurley |first=Gillian |last2=Busch |first2=Christer |last3=Fagerberg |first3=Linn |last4=Hallström |first4=Björn M. |last5=Stadler |first5=Charlotte |last6=Tolf |first6=Anna |last7=Lundberg |first7=Emma |last8=Schwenk |first8=Jochen M. |last9=Jirström |first9=Karin |date=2015-08-03 |title=Analysis of the Human Prostate-Specific Proteome Defined by Transcriptomics and Antibody-Based Profiling Identifies TMEM79 and ACOXL as Two Putative, Diagnostic Markers in Prostate Cancer |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=10 |issue=8 |pages=e0133449 |bibcode=2015PLoSO..1033449O |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0133449 |issn=1932-6203 |pmc=4523174 |pmid=26237329 |doi-access=free}}</ref> The corresponding specific proteins are expressed in the glandular and secretory cells of the prostatic gland and have functions that are important for the characteristics of ], including prostate-specific ]s, such as the ], and the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kong |first=HY |last2=Byun |first2=J |date=January 2013 |title=Emerging roles of human prostatic Acid phosphatase. |journal=Biomolecules & Therapeutics |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=10–20 |doi=10.4062/biomolther.2012.095 |pmc=3762301 |pmid=24009853 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ===Development=== | ===Development=== | ||

| {{Further|Development of the reproductive system}} | |||

| The prostatic part of the urethra develops from the ''pelvic'' (middle) part of the ] (endodermal origin). ] outgrowths arise from the prostatic part of the urethra and grow into the surrounding ]. The glandular epithelium of the prostate differentiates from these endodermal cells, and the associated mesenchyme differentiates into the dense ] and the ] of the prostate.<ref>Moore, Keith L.; Persaud, T. V. N. and Torchia, Mark G. (2008) ''Before We Are Born, Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects'', 7th edition, Saunders Elsevier, ISBN 978-1-4160-3705-7</ref> The prostate glands represent the modified wall of the proximal portion of the male urethra and arises by the 9th week of embryonic life in the ]. Condensation of ], ] and ]s gives rise to the adult prostate gland, a composite organ made up of several glandular and non-glandular components tightly fused. | |||

| In the developing ], at the hind end lies an inpouching called the ]. This, over the fourth to the seventh week, divides into a ] and the beginnings of the ], with a wall forming between these two inpouchings called the ].<ref name="Sadley-2019">{{Cite book |last=Sadley |first=TW |title=Langman's medical embryology |date=2019 |publisher=Wolters Kluwer |isbn=9781496383907 |edition=14th |location=Philadelphia |pages=263–66 |chapter=Bladder and urethra}}</ref> The urogenital sinus divides into three parts, with the middle part forming the urethra; the upper part is largest and becomes the ], and the lower part then changes depending on the biological sex of the embryo.<ref name="Sadley-2019" /> | |||

| ===Regulation=== | |||

| To function properly, the prostate needs male ] (]s), which are responsible for male ] characteristics. The main male hormone is ], which is produced mainly by the ]s. Some male hormones are produced in small amounts by the ]s. However, it is ] that regulates the prostate. | |||

| The prostatic part of the urethra develops from the middle, pelvic, part of the urogenital sinus, which is of ]al origin.<ref name="Sadley-2019a">{{Cite book |last=Sadley |first=TW |title=Langman's medical embryology |date=2019 |publisher=Wolters Kluwer |isbn=9781496383907 |edition=14th |location=Philadelphia |pages=265–6}}</ref> Around the end of the third month of embryonic life, outgrowths arise from the prostatic part of the urethra and grow into the surrounding ].<ref name="Sadley-2019a" /> The cells lining this part of the urethra differentiate into the glandular epithelium of the prostate.<ref name="Sadley-2019a" /> The associated mesenchyme differentiates into the dense connective tissue and the ] of the prostate.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Moore |first=Keith L. |title=Before We are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects |last2=Persaud |first2=T. V. N. |last3=Torchia |first3=Mark G. |publisher=Saunders/Elsevier |year=2008 |isbn=978-1-4160-3705-7 |edition=7th}}</ref> | |||

| ==Prostate disorders== | |||

| Condensation of ], ], and ]s gives rise to the adult prostate gland, a composite organ made up of several tightly fused glandular and non-glandular components. To function properly, the prostate needs male ] (]s), which are responsible for male ] characteristics. The main male hormone is ], which is produced mainly by the ]s. It is ] (DHT), a metabolite of testosterone, that predominantly regulates the prostate. The prostate gland enlarges over time, until the fourth decade of life.<ref name="Standring-2016" /> | |||

| ===Prostatitis=== | |||

| {{main|Prostatitis}} | |||

| ] showing an ] prostate gland, the ] correlate of '''prostatitis'''. A normal non-inflamed prostatic gland is seen on the left of the image. ].]] | |||

| ] is ] of the prostate gland. There are primarily four different forms of prostatitis, each with different causes and outcomes. Two relatively uncommon forms, acute prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis, are treated with ]s (category I and II, respectively). Chronic non-bacterial prostatitis or male chronic pelvic pain syndrome (category III), which comprises about 95% of prostatitis diagnoses, is treated by a large variety of modalities including ], ], ], ], ]s, ]s, ]s, ],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ProstatitisSurgery.com|title=Video post-op interviews with prostatitis surgery patients |work=ProstatitisSurgery.com}}</ref> and more.<ref name="cpcom">{{cite web|url=http://www.chronicprostatitis.com/meds.html|title=Pharmacological treatment options for prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome|work=chronicprostatitis.com|accessdate=2006-12-11|year=2006}}</ref> More recently, a combination of ] and psychological therapy has proved effective for category III prostatitis as well.<ref name="pmid16952676">{{cite journal |author=Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan CA |title=Sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: improvement after trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training |journal=J. Urol. |volume=176 |issue=4 Pt 1 |pages=1534–8; discussion 1538–9 |year=2006 |pmid=16952676 |doi=10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.010}}</ref> Category IV prostatitis, relatively uncommon in the general population, is a type of ]. | |||

| ==Function== | |||

| ===Benign prostatic hyperplasia=== | |||

| {{main|Benign prostatic hyperplasia}} | |||

| ] (BPH) occurs in older men;<ref name="pmid">{{cite journal |author=Verhamme KM, Dieleman JP, Bleumink GS, ''et al.'' |title=Incidence and prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care—the Triumph project |journal=Eur. Urol. |volume=42 |issue=4 |pages=323–8 |year=2002| doi = 10.1016/S0302-2838(02)00354-8 |pmid=12361895}}</ref> the prostate often enlarges to the point where urination becomes difficult. Symptoms include needing to ] often (frequency) or taking a while to get started (hesitancy). If the prostate grows too large, it may constrict the urethra and impede the flow of urine, making urination difficult and painful and, in extreme cases, completely impossible. | |||

| ===In ejaculation=== | |||

| BPH can be treated with medication, a ] or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate. Minimally invasive procedures include ] (TUNA) and ] (TUMT).<ref>{{Cite journal | last = Christensen| first = TL| last2 = Andriole| first2 = GL| title = Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Current Treatment Strategies| journal = Consultant| volume = 49| issue = 2| date = February 2009| year = 2009| url = http://www.consultantlive.com/display/article/10162/1376744}}</ref> These outpatient procedures may be followed by the insertion of a temporary ], to allow normal voluntary urination, without exacerbating irritative symptoms.<ref name="pmid18374395">{{cite journal |author=Dineen MK, Shore ND, Lumerman JH, Saslawsky MJ, Corica AP |title=Use of a Temporary Prostatic Stent After Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy Reduced Voiding Symptoms and Bother Without Exacerbating Irritative Symptoms |journal=J. Urol. |volume=71 |issue=5 |pages=873–877 |year=2008 |pmid=18374395 |doi=10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.015}}</ref> | |||

| The prostate secretes fluid, which becomes part of the ]. Its secretion forms up to 30% of the semen. Semen is the fluid emitted (]) by males during the ].<ref name="Barrett-2019" /> When sperm are emitted, they are transmitted from the ] into the male ] via the ], which lies within the prostate gland.<ref name="Barrett-2019" /> ] is the expulsion of semen from the urethra.<ref name="Barrett-2019" /> Semen is moved into the urethra following contractions of the smooth muscle of the vas deferens and seminal vesicles, following stimulation, primarily of the ]. Stimulation sends nerve signals via the ]s to the upper ]; the nerve signals causing contraction act via the ]s.<ref name="Barrett-2019" /> After traveling into the urethra, the seminal fluid is ejaculated by contraction of the ].<ref name="Barrett-2019">{{Cite book |last=Barrett |first=Kim E. |title=Ganong's review of medical physiology |last2=Barman |first2=Susan M. |last3=Brooks |first3=Heddwen L. |last4=Yuan |first4=Jason X.-J. |last5=Ganong |first5=William F. |publisher=McGraw-Hill Education |year=2019 |isbn=9781260122404 |edition=26th |location=New York |pages=411, 415 |oclc=1076268769}}</ref> The secretions of the prostate include ]s, ], ], ], and ].<ref name="Standring-2016" /> Together with the secretions from the seminal vesicles, these form the major fluid part of semen.<ref name="Standring-2016" /> | |||

| ===In urination=== | |||

| The surgery most often used in such cases is called transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP or TUR). In TURP, an instrument is inserted through the urethra to remove prostate tissue that is pressing against the upper part of the ] and restricting the flow of ]. TURP results in the removal of mostly transitional zone tissue in a patient with BPH. Older men often have ''corpora amylacea''<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ouhsc.edu/histology/Glass%20slides/33_09.jpg |title=Slide 33: Prostate, at ouhsc.edu |accessdate= |work=}}</ref> (]), dense accumulations of calcified proteinaceous material, in the ducts of their prostates. The corpora amylacea may obstruct the lumens of the prostatic ducts, and may underlie some cases of BPH. | |||

| {{see also|Surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia}} | |||

| The prostate's changes of shape, which facilitate the mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation, are mainly driven by the two longitudinal muscle systems running along the prostatic urethra. These are the ''urethral ]'' (''musculus dilatator urethrae'') on the urethra's front side, which contracts during urination and thereby shortens and tilts the prostate in its vertical dimension thus widening the prostatic section of the urethral tube,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hocaoglu |first=Y |last2=Roosen |first2=A |last3=Herrmann |first3=K |last4=Tritschler |first4=S |last5=Stief |first5=C |last6=Bauer |first6=RM |year=2012 |title=Real-time magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): anatomical changes during physiological voiding in men. |journal=BJU Int |volume=109 |issue=2 |pages=234–9 |doi=10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10255.x |pmid=21736694 |s2cid=9423239}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hocaoglu |first=Y |last2=Herrmann |first2=K |last3=Walther |first3=S |last4=Hennenberg |first4=M |last5=Gratzke |first5=C |last6=Bauer |first6=R |display-authors=etal |year=2013 |title=Contraction of the anterior prostate is required for the initiation of micturition. |journal=BJU Int |volume=111 |issue=7 |pages=1117–23 |doi=10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11698.x |pmid=23356864 |s2cid=31046054}}</ref> and the muscle switching the urethra into the ejaculatory state (''musculus ejaculatorius'') on its backside.<ref name="Schünke-2012" /> | |||

| In case of an operation, e.g. because of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), damaging or sparing of these two muscle systems varies considerably depending on the choice of operation type and details of the procedure of the chosen technique. The effects on postoperational urination and ejaculation vary correspondingly.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lebdai |first=S |last2=Chevrot |first2=A |last3=Doizi |first3=S |last4=Pradere |first4=B |last5=Delongchamps |first5=NB |last6=Benchikh |first6=A |display-authors=etal |year=2019 |title=Do patients have to choose between ejaculation and miction? A systematic review about ejaculation preservation technics for benign prostatic obstruction surgical treatment. |url=http://website60s.com/upload/files/world-journal-of-urology-v37-iss2-a10.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=World J Urol |volume=37 |issue=2 |pages=299–308 |doi=10.1007/s00345-018-2368-6 |pmid=29967947 |s2cid=49556196 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210811023908/http://website60s.com/upload/files/world-journal-of-urology-v37-iss2-a10.pdf |archive-date=2021-08-11 |access-date=2020-11-16}}</ref> | |||

| Urinary frequency due to bladder spasm, common in older men, may be confused with prostatic hyperplasia. | |||

| ] suggest that a diet low in ] and ] and high in ] and ], as well as regular ], could protect against BPH.<ref name="pmid18263602">{{cite journal |author=Kristal AR, Arnold KB, Schenk JM, ''et al.'' |title=Dietary patterns, supplement use, and the risk of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial |journal=Am. J. Epidemiol. |volume=167 |issue=8 |pages=925–34 |year=2008 |pmid=18263602 |doi=10.1093/aje/kwm389}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===In stimulation=== | ||

| It is possible for some men to achieve ] solely through stimulation of the prostate gland, such as via ] or ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Rosenthal |first=Martha |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=d58z5hgQ2gsC&pg=PT153 |title=Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society |publisher=] |year=2012 |isbn=978-0618755714 |pages=133–135 |access-date=September 17, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Komisaruk, Barry R. |author-link=Barry Komisaruk |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Kkts3AX9QVAC&pg=PA108 |title=The Orgasm Answer Guide |last2=Whipple, Beverly |author-link2=Beverly Whipple |last3=Nasserzadeh, Sara |author-link3=Sara Nasserzadeh |last4=Beyer-Flores, Carlos |publisher=JHU Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-8018-9396-4 |pages=108–109 |access-date=6 November 2011 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> This has led to the area of the ] adjacent to the prostate to be popularly referred to as the "male ]".<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Levin |first=R. J. |date=2018 |title=Prostate-induced orgasms: A concise review illustrated with a highly relevant case study |journal=Clinical Anatomy |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=81–85 |doi=10.1002/ca.23006 |pmid=29265651 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Prostate cancer}} | |||

| ] showing normal prostatic glands and glands of ] (prostate adenocarcinoma) – right upper aspect of image. ]. ].]] | |||

| ] is one of the most common ]s affecting older men in ] and a significant cause of ] for elderly men (estimated by some specialists at 3%{{Citation needed|date=December 2013}}). Despite this, the ]'s position regarding early detection is "Research has not yet proven that the potential benefits of testing outweigh the harms of testing and treatment" and that they believe "that men should not be tested without learning about what we know and don’t know about the risks and possible benefits of testing and treatment. Starting at age 50 (age 45 if you are of Black race or if your father or brother acquired prostate cancer before age 65), talk to your doctor about the pros and cons of testing so you can decide if testing is the right choice for you".<ref>. Cancer.org. Retrieved on 2013-01-21.</ref> | |||

| If checks are performed, they can be in the form of a physical ], measurement of ] (PSA) level in the blood, or checking for the presence of the protein ] (EN2) in the urine. | |||

| ==Clinical significance== | |||

| Co-researchers Hardev Pandha and Richard Morgan published their findings regarding checking for ] in urine in the 1 March 2011 issue of the journal ].<ref>{{cite journal|doi= 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2410|title= Engrailed-2 (EN2): A Tumor Specific Urinary Biomarker for the Early Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer|year= 2011|last1= Morgan|first1= R.|last2= Boxall|first2= A.|last3= Bhatt|first3= A.|last4= Bailey|first4= M.|last5= Hindley|first5= R.|last6= Langley|first6= S.|last7= Whitaker|first7= H. C.|last8= Neal|first8= D. E.|last9= Ismail|first9= M.|journal= Clinical Cancer Research|volume= 17|issue= 5|pages= 1090–8|pmid= 21364037 }}</ref> A laboratory test currently identifies EN2 in urine, and a home test kit is envisioned similar to a home pregnancy test strip. According to Morgan, "We are preparing several large studies in the UK and in the US and although the EN2 test is not yet available, several companies have expressed interest in taking it forward."<ref>. medicinechest.co.uk (2 March 2011)</ref> | |||

| == |

===Inflammation=== | ||

| {{Main|Prostatitis}} | |||

| <!--Introduction, symptoms and investigations--> | |||

| ===Unclogging a prostate=== | |||

| ] showing ] prostate (]) with large amount of darker cells (]s); area without inflammation seen on the left]] | |||

| A surgeon can unclog a blocked prostate by inserting a temporary or permanent artificial ] via the urethra. This is mostly done on an outpatient basis under local or spinal anesthesia and takes about 30 minutes. | |||

| Prostatitis is ] of the prostate gland. It can be caused by infection with bacteria, or other noninfective causes. Inflammation of the prostate can cause ] or ejaculation, groin pain, difficulty passing urine, or ] such as ] or ].{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} When inflamed, the prostate becomes enlarged and is tender when touched during ]. The bacteria responsible for the infection may be detected by a ].{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} | |||

| ==Vasectomy and risk of prostate cancer== | |||

| In 1983, the Journal of the American Medical Association reported a connection between ] and an increased risk of ]. Reported studies of 48,000 and 29,000 men who had vasectomies showed 66 percent and 56 percent higher rates of prostate cancer, respectively. The risk increased with age and the number of years since the vasectomy was performed. | |||

| <!--Treatment--> | |||

| However, in March of the same year, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development held a conference cosponsored by the National Cancer Institute and others to review the available data and information on the link between prostate cancer and vasectomies. It was determined that an association between the two was very weak at best, and even if having a vasectomy increased one's risk, the risk was relatively small. | |||

| Acute prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis are treated with ]s.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} ] is treated by a large variety of modalities including the medications ], ] and ],{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} ]s, and other ]s.<ref name="Anderson-2006" /> Other treatments that are not medications may include ],<ref>{{Cite web |year=2014 |title=Physical Therapy Treatment for Prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome |url=http://www.chronicprostatitis.com/the-wise-anderson-protocol/ |access-date=2014-10-22}}</ref> ], ]s, and ]. More recently, a combination of ] and psychological therapy has proved effective for category III prostatitis as well.<ref name="Anderson-2006">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan CA |year=2006 |title=Sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: improvement after trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training |journal=J. Urol. |volume=176 |issue=4 Pt 1 |pages=1534–8; discussion 1538–9 |citeseerx=10.1.1.383.7495 |doi=10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.010 |pmid=16952676}}</ref> | |||

| ===Prostate enlargement=== | |||

| In 1997, the NCI held a conference with the prostate cancer Progressive Review Group (a committee of scientists, medical personnel, and others). Their final report, published in 1998 stated that evidence that vasectomies help to develop prostate cancer was weak at best.<ref>{{cite web |title=Defeating Prostate Cancer: Crucial Directions for Research |url=http://planning.cancer.gov/library/1998prostate.pdf |date=August 1998 |publisher=] |accessdate=2012-08-19}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Benign prostatic hyperplasia}} | |||

| <!--Intro and symptoms--> | |||

| ==Female prostate gland== | |||

| An enlarged prostate is called prostatomegaly, with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) being the most common cause. BPH refers to an enlargement of the prostate due to an increase in the number of cells that make up the prostate ({{wt|en|hyperplasia}}) from a cause that is not a malignancy. It is very common in older men.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} It is often diagnosed when the prostate has enlarged to the point where urination becomes difficult. Symptoms include needing to urinate often (]) or taking a while to get started (]). If the prostate grows too large, it may constrict the urethra and impede the flow of urine, making urination painful and difficult, or in extreme cases completely impossible, causing ].{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} Over time, chronic retention may cause the bladder to become larger and cause a backflow of urine into the kidneys (]).{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} | |||

| The ], also known as the paraurethral gland, found in females, is ] to the prostate gland in males. However, anatomically, the ] is in the same position as the prostate gland. In 2002 the Skene's gland was officially renamed to female prostate by the ''Federative International Committee on Anatomical Terminology''.<ref name=seattletimes/> | |||

| <!--Management--> | |||

| The female prostate, like the male prostate, secretes ] and levels of this antigen rise in the presence of carcinoma of the gland. The gland also expels fluid, like the male prostate, during ].<ref name="pmid8004685">{{cite journal |author=Kratochvíl S |title=Orgasmic expulsions in women |language=Czech |journal=Česk Psychiatr |volume=90 |issue=2 |pages=71–7 |year=1994|pmid=8004685}}</ref> | |||

| BPH can be treated with medication, a ] or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate. In general, treatment often begins with an ] ] medication such as ], which reduces the tone of the ] found in the ] that passes through the prostate, making it easier for urine to pass through.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} For people with persistent symptoms, procedures may be considered. The surgery most often used in such cases is ],{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} in which an instrument is inserted through the urethra to remove prostate tissue that is pressing against the upper part of the urethra and restricting the flow of ]. Minimally invasive procedures include ] and ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Christensen |first=TL |last2=Andriole |first2=GL |date=February 2009 |title=Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Current Treatment Strategies |url=http://www.consultantlive.com/display/article/10162/1376744 |journal=Consultant |volume=49 |issue=2}}</ref> These outpatient procedures may be followed by the insertion of a temporary ], to allow normal voluntary urination, without exacerbating irritative symptoms.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Dineen MK, Shore ND, Lumerman JH, Saslawsky MJ, Corica AP |year=2008 |title=Use of a Temporary Prostatic Stent After Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy Reduced Voiding Symptoms and Bother Without Exacerbating Irritative Symptoms |journal=J. Urol. |volume=71 |issue=5 |pages=873–877 |doi=10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.015 |pmid=18374395}}</ref> | |||

| ===Cancer=== | |||

| ==Additional images== | |||

| {{Main|Prostate cancer}} | |||

| {{Gallery | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| |title= | |||

| | align = right | |||

| |width=120 | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| |height=150 | |||

| | width = 220 | |||

| |lines=5 | |||

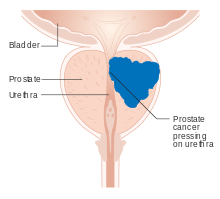

| | image2 = Diagram showing prostate cancer pressing on the urethra CRUK 182.svg | |||

| |Image:Illu bladder.jpg|Urinary bladder | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| |Image:Illu penis.jpg|Structure of the penis | |||

| | caption2 = A diagram of prostate cancer pressing on the urethra, which can cause symptoms | |||

| |Image:Illu prostate lobes.jpg|Lobes of prostate | |||

| | image4 = Prostate adenocarcinoma 2 high mag hps.jpg | |||

| |Image:Illu prostate zones.jpg|Zones of prostate | |||

| | alt4 = | |||

| |Image:Illu quiz prostate01.jpg|Prostate | |||

| | caption4 = ] showing normal prostate cancer in the right upper aspect of image. ]. ]. | |||

| |Image:Prostatehistology.jpg|Microscopic glands of the prostate | |||

| |Image:male anatomy.png|Male Anatomy | |||

| |Image:Gray543.png|The deeper branches of the internal pudendal artery. | |||

| |Image:Gray619.png|Lymphatics of the prostate. | |||

| |Image:Gray1152.png|Fundus of the bladder with the vesiculæ seminales. | |||

| |Image:Gray1153.png|Vesiculae seminales and ampullae of ductus deferentes, front view. | |||

| |Image:Gray1156.png|Vertical section of bladder, penis, and urethra. | |||

| |Image:Prostatic urethra.svg|Dissection of prostate showing prostatic urethra. | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| Prostate cancer is one of the most common ]s affecting older men in the UK, US, Northern Europe and Australia, and a significant ] for elderly men worldwide.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Rawla P |date=April 2019 |title=Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer |journal=World J Oncol |type=Review |volume=10 |issue=2 |pages=63–89 |doi=10.14740/wjon1191 |pmc=6497009 |pmid=31068988}}</ref> Often, a person does not have symptoms; when they do occur, symptoms may include urinary frequency, urgency, hesitation and other symptoms associated with BPH. Uncommonly, such cancers may cause weight loss, retention of urine, or symptoms such as ] due to {{wt|en|metastatic}} lesions that have spread outside of the prostate.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{Misplaced Pages books|Prostate}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| <!--Investigations--> | |||

| ;Glossary | |||

| A ] and the measurement of a ] (PSA) level are usually the first investigations done to check for prostate cancer. PSA values are difficult to interpret, because a high value might be present in a person without cancer, and a low value can be present in someone with cancer.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} The next form of testing is often the taking of a ] to assess for ] and invasiveness.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} Because of the significant risk of ] with widespread screening in the general population, ] is controversial.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sandhu |first=Gurdarshan S. |last2=Andriole |first2=Gerald L. |date=September 2012 |title=Overdiagnosis of Prostate Cancer |journal=Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs |volume=2012 |issue=45 |pages=146–151 |doi=10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs031 |issn=1052-6773 |pmc=3540879 |pmid=23271765}}</ref> If a tumour is confirmed, ] such as an ] or ] may be done to check for the presence of tumour {{wt|en|metastases}} in other parts of the body.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} | |||

| {{further2|]}} | |||

| <!--Management--> | |||

| Prostate cancer that is only present in the prostate is often treated with either surgical ] or with ] or by the insertion of small radioactive particles of ] or ], called ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=What is Brachytherapy? |url=https://www.americanbrachytherapy.org/resources/for-patients/what-is-brachytherapy/ |access-date=8 August 2020 |website=American Brachytherapy Society |language=en}}</ref>{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} Cancer that has spread to other parts of the body is usually treated also with hormone therapy, to deprive a tumour of sex hormones (androgens) that stimulate proliferation. This is often done through the use of ] or agents (such as ]) that block the receptors that androgens act on; occasionally, ] may be done instead.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} Cancer that does not respond to hormonal treatment, or that progresses after treatment, might be treated with ] such as ]. ] may also be used to help with pain associated with bony lesions.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} | |||

| Sometimes, the decision may be made not to treat prostate cancer. If a cancer is small and localised, the decision may be made to monitor for cancer activity at intervals ("active surveillance") and defer treatment.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} If a person, because of ] or other medical conditions or reasons, has a ] less than ten years, then the impacts of treatment may outweigh any perceived benefits.{{sfn|Davidson's|2018|pp=437–9}} | |||

| ===Surgery=== | |||

| {{Main|Prostatectomy}} | |||

| <!--Introduction--> | |||

| Surgery to remove the prostate is called prostatectomy, and is usually done as a treatment for cancer limited to the prostate, or prostatic enlargement.<ref name="Cancer=2019">{{Cite web |date=1 August 2019 |title=Surgery for Prostate Cancer |url=https://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/treating/surgery.html |access-date=8 August 2020 |website=www.cancer.org |publisher=The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team |language=en}}</ref> When it is done, it may be done as ] or as ].<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> These are done under ].<ref name="CRUK-2019">{{Cite web |date=18 Jun 2019 |title=Surgery to remove your prostate gland {{!}} Prostate cancer {{!}} Cancer Research UK |url=https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/prostate-cancer/treatment/surgery/surgery-remove-your-prostate-gland |access-date=8 August 2020 |website=www.cancerresearchuk.org |publisher=Cancer Research UK}}</ref> Usually the procedure for cancer is a ], which means that the seminal vesicles are removed and the vasa deferentia are also tied off.<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> Part of the prostate can also be removed from within the urethra, called ] (TURP).<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> Open surgery may involve a cut that is made in the ], or via an approach that involves a cut down the midline from the belly button to the ].<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> Open surgery may be preferred if there is a suspicion that lymph nodes are involved and they need to be removed or biopsied during a procedure.<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> A perineal approach will not involve lymph node removal and may result in less pain and a faster recovery following an operation.<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> A TURP procedure uses a tube inserted into the urethra via the penis and some form of heat, electricity or laser to remove prostate tissue.<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> | |||

| <!--Complications--> | |||

| The whole prostate can be removed. Complications that might develop because of surgery include ] and ] because of damage to nerves during the operation, particularly if a cancer is very close to nerves.<ref name="Cancer=2019" /><ref name="CRUK-2019" /> ] of ] will not occur during ] if the vasa deferentia are tied off and seminal vesicles removed, such as during a radical prosatectomy.<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> This will mean a man becomes ].<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> Sometimes, orgasm may not be able to occur or may be painful. The penis length may shorten slightly if the part of the urethra within the prostate is also removed.<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> General complications due to surgery can also develop, such as ]s, ], inadvertent damage to nearby organs or within the abdomen, and the formation of ]s.<ref name="Cancer=2019" /> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The prostate was first formally identified by ] anatomist ] in ''Anatomiae libri introductorius'' (Introduction to Anatomy) in 1536 and illustrated by ] anatomist ] in ''Tabulae anatomicae sex'' (six anatomical tables) in 1538.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ghabili |first=Kamyar |last2=Tosoian |first2=Jeffrey J. |last3=Schaeffer |first3=Edward M. |last4=Pavlovich |first4=Christian P. |last5=Golzari |first5=Samad E.J. |last6=Khajir |first6=Ghazal |last7=Andreas |first7=Darian |last8=Benzon |first8=Benjamin |last9=Vuica-Ross |first9=Milena |last10=Ross |first10=Ashley E. |date=November 2016 |title=The History of Prostate Cancer From Antiquity: Review of Paleopathological Studies |journal=Urology |volume=97 |pages=8–12 |doi=10.1016/j.urology.2016.08.032 |pmid=27591810}}</ref><ref name="Goddard-2019" /> Massa described it as a "glandular flesh upon which rests the neck of the bladder," and Vesalius as a "glandular body".<ref name="Marx-2009">{{Cite journal |last=Josef Marx |first=Franz |last2=Karenberg |first2=Axel |date=1 February 2009 |title=History of the Term Prostate |journal=The Prostate |volume=69 |issue=2 |pages=208–213 |doi=10.1002/pros.20871 |pmid=18942121 |s2cid=44922919}}</ref> The first time a word similar to ''prostate'' was used to describe the gland is credited to ] in 1600, who described it as a term already in use by anatomists at the time.<ref name="Marx-2009" /><ref name="Goddard-2019" /> The term was however used at least as early as 1549 by French surgeon ].<ref name="Goddard-2019" /> | |||

| At the time, Du Laurens was describing what was considered to be a pair of organs (not the single two-lobed organ), and the ] term ''prostatae'' that was used was a mistranslation of the term for the ] word used to describe the ], ''parastatai'';<ref name="Marx-2009" /> although it has been argued that surgeons in Ancient Greece and Rome must have at least seen the prostate as an anatomical entity.<ref name="Goddard-2019" /> The term ''prostatae'' was taken rather than the grammatically correct ''prostator'' (singular) and ''prostatores'' (plural) because the ] of the Ancient Greek term was taken as female, when it was in fact male.<ref name="Marx-2009" /> | |||

| The fact that the prostate was one and not two organs was an idea popularised throughout the early 18th century, as was the English language term used to describe the organ, ''prostate'',<ref name="Marx-2009" /> attributed to ].<ref name="Young-2019">{{Cite journal |last=Young |first=Robert H |last2=Eble |first2=John N |date=January 2019 |title=The history of urologic pathology: an overview |journal=Histopathology |volume=74 |issue=1 |pages=184–212 |doi=10.1111/his.13753 |pmid=30565309 |s2cid=56476748}}</ref> A ], "Practical observations on the treatment of the diseases of the prostate gland" by ] in 1811, was important in the history of the prostate by describing and naming anatomical parts of the prostate, including the median lobe.<ref name="Marx-2009" /> The idea of the five lobes of the prostate was popularized following anatomical studies conducted by American urologist ] in 1912.<ref name="Goddard-2019" /><ref name="Young-2019" /> John E. McNeal first proposed the idea of "zones" in 1968; McNeal found that the relatively homogeneous cut surface of an adult prostate in no way resembled "lobes" and thus led to the description of "zones".<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Myers, Robert P |year=2000 |title=Structure of the adult prostate from a clinician's standpoint |journal=Clinical Anatomy |volume=13 |issue=3 |pages=214–5 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(2000)13:3<214::AID-CA10>3.0.CO;2-N |pmid=10797630 |s2cid=33861863}}</ref> | |||

| <!--Prostate cancer--> | |||

| Prostate cancer was first described in a speech to the ] in 1853 by surgeon ]<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Adams J |year=1853 |title=The case of scirrhous of the prostate gland with corresponding affliction of the lymphatic glands in the lumbar region and in the pelvis |journal=Lancet |volume=1 |issue=1547 |pages=393–94 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(02)68759-8}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Ghabili K, Tosoian JJ, Schaeffer EM, Pavlovich CP, Golzari SE, Khajir G, Andreas D, Benzon B, Vuica-Ross M, Ross AE |date=November 2016 |title=The History of Prostate Cancer From Antiquity: Review of Paleopathological Studies |journal=Urology |volume=97 |pages=8–12 |doi=10.1016/j.urology.2016.08.032 |pmid=27591810}}</ref> and increasingly described by the late 19th century.<ref name="Nahon-2011">{{Cite journal |last=Nahon |first=I |last2=Waddington |first2=G |last3=Dorey |first3=G |last4=Adams |first4=R |date=2011 |title=The history of urologic surgery: from reeds to robotics. |journal=Urologic Nursing |volume=31 |issue=3 |pages=173–80 |doi=10.7257/1053-816X.2011.31.3.173 |pmid=21805756}}</ref> Prostate cancer was initially considered a rare disease, probably because of shorter ] and poorer detection methods in the 19th century. The first treatments of prostate cancer were surgeries to relieve urinary obstruction.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Lytton B |date=June 2001 |title=Prostate cancer: a brief history and the discovery of hormonal ablation treatment |journal=The Journal of Urology |volume=165 |issue=6 Pt 1 |pages=1859–62 |doi=10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66228-3 |pmid=11371867}}</ref> ] has been credited with the first mention of a prostatectomy, as "too absurd to be seriously entertained"<ref>{{Cite book |last=Samuel David Gross |author-link=Samuel David Gross |url=https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-100890231-bk |title=A Practical Treatise On the Diseases and Injuries of the Urinary Bladder, the Prostate Gland, and the Urethra |date=1851 |publisher=Blanchard and Lea |location=Philadelphia |quote=""The idea of extirpating the entire gland is, indeed, too absurd to be seriously entertained... Excision of the middle lobe would be far less objectionable""}}</ref><ref name="Nahon-2011" /> The first removal for prostate cancer (radical perineal ]) was first performed in 1904 by ] at ];<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Young HH |year=1905 |title=Four cases of radical prostatectomy |journal=Johns Hopkins Bull. |volume=16}}</ref><ref name="Nahon-2011" /> partial removal of the gland was conducted by ] in 1867.<ref name="Young-2019" /> | |||

| ] (TURP) replaced radical prostatectomy for symptomatic relief of obstruction in the middle of the 20th century because it could better preserve penile erectile function. Radical retropubic prostatectomy was developed in 1983 by Patrick Walsh.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Walsh PC, Lepor H, Eggleston JC |year=1983 |title=Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations |journal=The Prostate |volume=4 |issue=5 |pages=473–85 |doi=10.1002/pros.2990040506 |pmid=6889192 |s2cid=30740301}}</ref> In 1941, ] published studies in which he used ] to oppose testosterone production in men with metastatic prostate cancer. This discovery of "chemical ]" won Huggins the 1966 ].<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Huggins CB, Hodges CV |year=1941 |title=Studies on prostate cancer: 1. The effects of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate |url=http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/1/4/293 |url-status=live |journal=Cancer Res |volume=1 |issue=4 |pages=293 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170630121943/http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/1/4/293 |archive-date=2017-06-30}}</ref> | |||

| The role of the ] (GnRH) in reproduction was determined by ] and ], who both won the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work. GnRH receptor agonists, such as ] and ], were subsequently developed and used to treat prostate cancer.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Schally AV, Kastin AJ, Arimura A |date=November 1971 |title=Hypothalamic follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH)-regulating hormone: structure, physiology, and clinical studies |journal=Fertility and Sterility |volume=22 |issue=11 |pages=703–21 |doi=10.1016/S0015-0282(16)38580-6 |pmid=4941683 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |display-authors=6 |vauthors=Tolis G, Ackman D, Stellos A, Mehta A, Labrie F, Fazekas AT, Comaru-Schally AM, Schally AV |date=March 1982 |title=Tumor growth inhibition in patients with prostatic carcinoma treated with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=79 |issue=5 |pages=1658–62 |bibcode=1982PNAS...79.1658T |doi=10.1073/pnas.79.5.1658 |pmc=346035 |pmid=6461861 |doi-access=free}}</ref> ] for prostate cancer was first developed in the early 20th century and initially consisted of intraprostatic ] implants. ] became more popular as stronger ] radiation sources became available in the middle of the 20th century. ] with implanted seeds (for prostate cancer) was first described in 1983.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT |date=May 2002 |title=A history of prostate cancer treatment |journal=Nature Reviews. Cancer |volume=2 |issue=5 |pages=389–96 |doi=10.1038/nrc801 |pmc=4124639 |pmid=12044015}}</ref> Systemic ] for prostate cancer was first studied in the 1970s. The initial regimen of ] and ] was quickly joined by multiple regimens using a host of other systemic chemotherapy drugs.<ref>{{Cite journal |display-authors=6 |vauthors=Scott WW, Johnson DE, Schmidt JE, Gibbons RP, Prout GR, Joiner JR, Saroff J, Murphy GP |date=December 1975 |title=Chemotherapy of advanced prostatic carcinoma with cyclophosphamide or 5-fluorouracil: results of first national randomized study |journal=The Journal of Urology |volume=114 |issue=6 |pages=909–11 |doi=10.1016/S0022-5347(17)67172-6 |pmid=1104900}}</ref> | |||

| ==Other animals== | |||

| The prostate is found only in mammals.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Marker |first=Paul C |last2=Donjacour |first2=Annemarie A |last3=Dahiya |first3=Rajvir |last4=Cunha |first4=Gerald R |date=January 2003 |title=Hormonal, cellular, and molecular control of prostatic development |journal=Developmental Biology |volume=253 |issue=2 |pages=165–174 |doi=10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00031-3 |pmid=12645922 |doi-access=free}}</ref> The prostate glands of male ]s are proportionally larger than those of ] mammals.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HpjovN0vXW4C |title=Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials |last2=Marilyn Renfree |date=30 January 1987 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-33792-2}}</ref> The presence of a functional prostate in ]s is controversial, and if monotremes do possess functional prostates, they may not make the same contribution to semen as in other mammals.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Temple-Smith |first=P |last2=Grant |first2=T |date=2001 |title=Uncertain breeding: a short history of reproduction in monotremes. |journal=Reproduction, Fertility, and Development |volume=13 |issue=7–8 |pages=487–97 |doi=10.1071/rd01110 |pmid=11999298}}</ref> | |||

| The structure of the prostate varies, ranging from ] (as in humans) to ]. The gland is particularly well developed in ]ns<ref>{{Cite book |last=Eurell |first=Jo Ann |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GqiXUD__wwIC&dq=prostate&pg=PA250 |title=Dellmann's Textbook of Veterinary Histology |last2=Frappier |first2=Brian L. |date=2013-03-19 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-1-118-68582-2 |language=en}}</ref> and boars, though in other mammals, such as bulls, it can be small and inconspicuous.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sherwood |first=Lauralee |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BR8KAAAAQBAJ |title=Animal Physiology: From Genes to Organisms |last2=Klandorf |first2=Hillar |last3=Yancey |first3=Paul |date=January 2012 |publisher=Cengage Learning |isbn=9781133709510 |page=779}}</ref><ref>Nelsen, O. E. (1953) Blakiston, page 31.</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Hafez |first=E. S. E. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vTmQDQAAQBAJ&pg=PT36 |title=Reproduction in Farm Animals |last2=Hafez |first2=B. |date=2013 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-1-118-71028-9 |language=en}}</ref> In other animals, such as marsupials<ref>{{Cite book |last=Vogelnest |first=Larry |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=396VDwAAQBAJ&q=prostate |title=Current Therapy in Medicine of Australian Mammals |last2=Portas |first2=Timothy |date=2019-05-01 |publisher=Csiro Publishing |isbn=978-1-4863-0753-1 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N_ifwszrgFsC&q=prostate |title=Australian Mammal Society |date=December 1978 |publisher=Australian Mammal Society |language=en}}</ref> and small ], the prostate is disseminate, meaning not specifically localisable as a distinct tissue, but present throughout the relevant part of the urethra; in other animals, such as ] and American ], it may be present as a specific organ and in a disseminate form.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chenoweth |first=Peter J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hv6dAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA227 |title=Animal Andrology: Theories and Applications |last2=Lorton |first2=Steven |date=2014 |publisher=CABI |isbn=978-1-78064-316-8 |language=en}}</ref> In some marsupial species, the size of the prostate gland changes seasonally.<ref>{{Cite book |last=C. Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KqtlPZJ9y8EC |title=Life of Marsupials |publisher=Csiro Publishing |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-643-06257-3}}</ref> The prostate is the only accessory gland that occurs in male dogs.<ref>{{Cite book |last=John W. Hermanson |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WQ6BDwAAQBAJ |title=Miller and Evans' Anatomy of the Dog – E-Book |last2=Howard E. Evans |last3=Alexander de Lahunta |date=20 December 2018 |publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences |isbn=978-0-323-54602-7}}</ref> Dogs can produce in one hour as much prostatic fluid as a human can in a day. They excrete this fluid along with their urine to ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Glover |first=Tim |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JEgy1tHA7b0C&pg=PR3%22 |title=Mating Males: An Evolutionary Perspective on Mammalian Reproduction |date=2012-07-12 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=9781107000018 |page=31}}</ref> Additionally, dogs are the only species apart from humans seen to have a significant incidence of prostate cancer.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ettinger |first=Stephen J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4Qzau1jagOYC |title=Textbook of veterinary internal medicine : diseases of the dog and the cat |last2=Feldman |first2=Edward C. |date=24 December 2009 |isbn=9781437702828 |edition=7th |location=St. Louis, Mo. |page=2057}}</ref> The prostate is the only male accessory gland that occurs in ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Miller |first=Debra Lee |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sD3NBQAAQBAJ&dq=prostate&pg=PA131 |title=Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Cetacea: Whales, Porpoises and Dolphins |date=2016-04-19 |publisher=CRC Press |isbn=978-1-4398-4257-7 |language=en}}</ref> consisting of diffuse urethral glands<ref>{{Cite book |last=William F. Perrin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2rkHQpToi9sC |title=Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals |last2=Bernd Würsig |last3=J.G.M. Thewissen |date=26 February 2009 |publisher=Academic Press |isbn=978-0-08-091993-5}}</ref> surrounded by a very powerful compressor muscle.<ref>Rommel, Sentiel A., D. Ann Pabst, and William A. McLellan. "" Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Cetacea. Science Publishers (2016): 127–145.</ref> | |||

| The prostate gland originates with tissues in the urethral wall.{{Citation needed|date=January 2022|reason=Jerry Coyne also does not cite a source for this claim in his book cited subsequently here}} This means the ], a compressible tube used for urination, runs through the middle of the prostate; enlargement of the prostate can constrict the urethra so that urinating becomes slow and painful.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Coyne |first=Jerry A. |author-link=Jerry Coyne |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1bUoIpTQbLYC&q=prostate |title=Why Evolution is True |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2009 |isbn=9780199230846 |page=90}}</ref> | |||

| Prostatic secretions vary among species. They are generally composed of simple sugars and are often slightly alkaline.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Alan J. |first=Wein |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OH_OCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT1005 |title=Campbell-Walsh Urology |last2=Louis R. |first2=Kavoussi |last3=Alan W. |first3=Partin |last4=Craig A. |first4=Peters |date=23 October 2015 |publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences |isbn=9780323263740 |edition=Eleventh |pages=1005–}}</ref> In ] mammals, these secretions usually contain ]. The prostatic secretions of ]s usually contain ] or ] instead of fructose.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Armati |first=Patricia J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=x3S5v971Nk0C&pg=PA86 |title=Marsupials |last2=Dickman |first2=Chris R. |last3=Hume |first3=Ian D. |date=2006-08-17 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-139-45742-2 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Skene's gland== | |||

| Because the ] and the male prostate act similarly by secreting ] (PSA), which is an ] protein produced in males, and of prostate-specific ], the Skene's gland is sometimes referred to as the "female prostate".<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Pastor Z, Chmel R |year=2017 |title=Differential diagnostics of female "sexual" fluids: a narrative review |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325024271 |journal=International Urogynecology Journal |volume=29 |issue=5 |pages=621–629 |doi=10.1007/s00192-017-3527-9 |pmid=29285596 |s2cid=5045626}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Bullough |first=Vern L. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UHymAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA231 |title=Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia |last2=Bullough |first2=Bonnie |publisher=] |year=2014 |isbn=978-1135825096 |page=231}}</ref> Although ] to the male prostate (developed from the same ] tissues),<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lentz |first=Gretchen M |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=X5KT_w6Nye8C&pg=PA41 |title=Comprehensive Gynecology |last2=Lobo |first2=Rogerio A. |last3=Gershenson |first3=David M |last4=Katz |first4=Vern L. |publisher=], Philadelphia |year=2012 |isbn=978-0323091312 |page=41}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Hornstein |first=Theresa |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ibgKAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA61 |title=Biology of women |last2=Schwerin |first2=Jeri Lynn |publisher=Delmar, Cengage Learning |year=2013 |isbn=978-1-285-40102-7 |location=Clifton Park, NY |page=61 |oclc=911037670}}</ref> various aspects of its development in relation to the male prostate are widely unknown and a matter of research.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Toivanen R, Shen MM |year=2017 |title=Prostate organogenesis: tissue induction, hormonal regulation and cell type specification. |journal=Development |volume=144 |issue=8 |pages=1382–1398 |doi=10.1242/dev.148270 |pmc=5399670 |pmid=28400434}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| '''Notes''' | |||

| {{reflist|30em}} | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| '''Sources''' | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| *Portions of the text of this article were taken from NIH Publication No. 02-4806, a public domain resource. {{cite web|url=http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health/urolog/pubs/prospro/prospro.htm#1 |title=What I need to know about Prostate Problems |date=2002-06-01 |accessdate=2011-01-24 |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20020601194638/http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health/urolog/pubs/prospro/prospro.htm#1 |archivedate=2002-06-01}} | |||

| == |

===Sources=== | ||

| * {{Cite book |title=Davidson's principles and practice of medicine |date=2018 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=978-0-7020-7028-0 |editor-last=Ralston |editor-first=Stuart H. |edition=23rd |ref={{harvid|Davidson's|2018}} |editor-last2=Penman |editor-first2=Ian D. |editor-last3=Strachan |editor-first3=Mark W. |editor-last4=Hobson |editor-first4=Richard P.}} | |||

| *{{commonscat-inline|Prostate}} | |||

| ===Attribution=== | |||

| * Portions of the text of this article originate from NIH Publication No. 02-4806, a public domain resource. {{Cite web |date=2002-06-01 |title=What I need to know about Prostate Problems |url=http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health/urolog/pubs/prospro/prospro.htm#1 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020601194638/http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health/urolog/pubs/prospro/prospro.htm#1 |archive-date=2002-06-01 |access-date=2011-01-24 |publisher=National Institutes of Health |id=No. 02-4806}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * {{Commons category-inline}} | |||

| * {{Wiktionary-inline}} | |||

| {{Animal anatomy}} | |||

| {{Male reproductive system}} | {{Male reproductive system}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 18:31, 28 October 2024

Gland of the male reproductive systemFor the journal, see The Prostate. Not to be confused with prostrate (body position).

The prostate is an accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found in all male mammals. It differs between species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically. Anatomically, the prostate is found below the bladder, with the urethra passing through it. It is described in gross anatomy as consisting of lobes and in microanatomy by zone. It is surrounded by an elastic, fibromuscular capsule and contains glandular tissue, as well as connective tissue.

The prostate produces and contains fluid that forms part of semen, the substance emitted during ejaculation as part of the male sexual response. This prostatic fluid is slightly alkaline, milky or white in appearance. The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm. The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first part of ejaculate, together with most of the sperm, because of the action of smooth muscle tissue within the prostate. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid, those in prostatic fluid have better motility, longer survival, and better protection of genetic material.

Disorders of the prostate include enlargement, inflammation, infection, and cancer. The word prostate is derived from Ancient Greek prostátēs (προστάτης), meaning "one who stands before", "protector", "guardian", with the term originally used to describe the seminal vesicles.

Structure

The prostate is a exocrine gland of the male reproductive system. In adults, it is about the size of a walnut, and has an average weight of about 11 grams (0.39 oz), usually ranging between 7 and 16 grams (0.25–0.56 oz). The prostate is located in the pelvis. It sits below the urinary bladder and surrounds the urethra. The part of the urethra passing through it is called the prostatic urethra, which joins with the two ejaculatory ducts. The prostate is covered in a surface called the prostatic capsule or prostatic fascia.

The internal structure of the prostate has been described using both lobes and zones. Because of the variation in descriptions and definitions of lobes, the zone classification is used more predominantly.