| Revision as of 13:26, 27 January 2014 editXLinkBot (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers719,047 edits BOT--Reverting link addition(s) by 200.219.132.104 to revision 588292469 (http://valleadurni.blogspot.com/2012/02/use-of-nidaros.html )← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:18, 12 December 2024 edit undo2003:e6:6f33:e9c0:d1f6:ca0:f5f6:918c (talk) →Lay experience: typo corrected | ||

| (407 intermediate revisions by 90 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Forms of the Mass before 1570}} | |||

| The term '''''Pre-Tridentine Mass''''' here refers to the variants of the ] rite of ] in Rome before 1570, when, with his bull ], ] made the ], as revised<ref>"We decided to entrust this work to learned men of our selection. They very carefully collated all their work with the ancient codices in Our Vatican Library and with reliable, preserved or emended codices from elsewhere. Besides this, these men consulted the works of ancient and approved authors concerning the same sacred rites; and thus ''they have restored the Missal'' itself to the original form and rite of the holy Fathers. When this work has been gone over numerous times and ''further emended'', after serious study and reflection, We commanded that the finished product be printed and published" (Pope Pius V, Bull ''Quo primum'').</ref> by him, obligatory throughout the ], except for those places and congregations whose distinct rites could demonstrate an antiquity of 200 years or more. | |||

| {{Distinguish|Tridentine Mass|Novus Ordo}} | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Pre-Tridentine Mass''' refers to the evolving and regional forms of the Catholic ] in the West from antiquity to 1570. The basic structure solidified early and has been preserved, as well as important prayers such as the ]. | |||

| Following the ]'s desire for standardization, ], with his bull '']'', made the ] obligatory throughout the ], except for those places and congregations whose distinct rites could demonstrate an antiquity of two hundred years or more. | |||

| The Pope made this revision of the ], which included the introduction of the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar and the addition of all that in his Missal follows the '']'', at the request that the ] (1545–1563) presented to his predecessor at its | |||

| ==Development== | |||

| Outside of Rome in the period before 1570, many other liturgical rites were in use, not only in ], but also in the West. Some of the Western rites, such as the ], were unrelated to the ] that Pope Pius V revised and ordered to be adopted generally. But even the areas that at one time or another had accepted the Roman rite (see, below, "Middle Ages") had soon introduced changes and additions. As a result, every ecclesiastical province and almost every diocese had its local use, such as the ], the ] and the ] in England. In France there were strong traces of the ]. With the exception of the relatively few places where no form of the Roman Rite had ever been adopted, the ] remained generally uniform, but the prayers in the "Ordo Missae", and still more the "Proprium Sanctorum" and the "Proprium de Tempore", varied widely.<ref></ref> For that reason, this article considers only the liturgy of the Mass as celebrated in Rome. | |||

| ===Earliest accounts=== | |||

| {{See also|Origin of the Eucharist|Eucharist in the Catholic Church|Agape feast}} | |||

| {{quote box | |||

| | title = 2nd-century description of the ] | |||

| | quote = And this food is called among us ''Eukharistia'' , of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh. | |||

| | source = ]<ref name="justin">Justin Martyr, §LXVII</ref> (] 66:1–20 ) | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | width = 30% | |||

| | bgcolor = #FCF5F9 | |||

| }} | |||

| The earliest surviving account of the celebration of the ] or the ] in Rome is that of Saint ] (died c. 165), in chapter 67 of his '']'':<ref>{{cite web|title=Fathers|url= http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0126.htm|website=New Advent}}.</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|On the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons.}} | |||

| In chapter 65, Justin Martyr says that the ] was given before the bread and the wine mixed with water were brought to "the president of the brethren". The initial liturgical language used was ], before approximately the year 190 under ], when the Church in Rome changed from Greek to Latin, except in particular for the ] word "]", whose meaning Justin explains in Greek (γένοιτο), saying that by it "all the people present express their assent" when the president of the brethren "has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings".<ref>{{Citation | contribution = Christianity | first = The Rev. Sidney | last = Spencer | date = 2013-03-05 | url = http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-67437 | type = encyclopaedia | title = Britannica | edition = online | access-date = 2014-01-27 |url-access=subscription }}.</ref> | |||

| ==Earliest accounts== | |||

| The earliest surviving account of the celebration of the ] or the ] in Rome is that of Saint ] (died c. 165), in chapter 67 of his '']'' : | |||

| According to some scholars, the early Christian liturgy was a continuation of the liturgy of contemporary Jewish ] (as distinct from the temple liturgy): Duschesne comments "the only permanent element, on the whole, which Christianity added to the liturgy of the synagogue wasthe sacred meal instituted by Jesus Christ as a perpetual commemoration of himself."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Duschesne |first1=L. |title=Christian Worship: its Origin and Evolution |location=London |edition=1912}}</ref> This tradition included unaccompanied chant. | |||

| :On the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. | |||

| ===Early changes=== | |||

| In chapter 65, Justin Martyr says that the ] was given before the bread and the wine mixed with water were brought to "the president of the brethren." The language used was doubtless ], except in particular for the ] word "]", whose meaning Justin explains in Greek (γένοιτο), saying that by it "all the people present express their assent" when the president of the brethren "has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings." | |||

| {{Catholic Church sidebar}} | |||

| {{See also|History of the Roman Canon#Before St. Gregory I (to 590)}} | |||

| It is unclear when the language of the celebration finished changing from ] to ]. ] (190–202), may have been the first to use Latin in the liturgy in Rome. Others think Latin was finally adopted nearly a century later.<ref group=note>"The complete and definitive Latinization of the Roman liturgy seems to have happened toward the middle of the fourth century." {{Citation|first=Christine|last= Mohrmann|title=Études sur le latin des chrétiens|trans-title=Studies on the Latin of the Christian|place=Rome|publisher=Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura|year=1961–77|volume= I|page=54}}</ref> The change was probably gradual, with both languages being used for a while.<ref group=note>"The first Christians in Rome were chiefly people who came from the East and spoke Greek. The founding of Constantinople naturally drew such people thither rather than to Rome, and then Christianity at Rome began to spread among the Roman population, so that at last the bulk of the Christian population in Rome spoke Latin. Hence the change in the language of the liturgy. The liturgy was said (in Latin) first in one church and then in more, until the Greek liturgy was driven out, and the clergy ceased to know Greek. About 415 or 420 we find a Pope saying that he is unable to answer a letter from some Eastern bishops, because he has no one who could write Greek." {{Citation| first=Alfred|last=Plummer|title=Conversations with Dr. Döllinger 1870–1890|editor-first=Robrecht|editor-last=Boudens|publisher=Leuven University Press|year=1985|page= 13}}.</ref> | |||

| With regard to the ], the prayers beginning ''], ]'' and '']'' were already in use, even if not with quite the same wording as now, by the year 400; the '']'', the '']'', and the post-consecration '']'' and '']'' were added in the fifth century.<ref>{{Citation|first=Josef Andreas, SJ|last=Jungmann|language=de|title=Missarum Sollemnia – Eine genetische Erklärung der römischen Messe|trans-title=Solemn mass — A genetic explanation of the Roman Mass|publisher=Herder|place=]|year=1949|volume=I |pages=70–71}}.</ref><ref>{{Citation|first=Hermannus AP|last=Schmidt|language=la |title=Introductio in Liturgiam Occidentalem|trans-title=Introduction to Western liturgy|publisher=Herder|place=Rome-Freiburg-Barcelona|year=1960|page=352}}</ref> | |||

| Also, in Chapter 66 of Justin Martyr's First Apology, he describes the change (explained to be ]) which occurs on the altar: "For not as common bread nor common drink do we receive these; but since Jesus Christ our Saviour was made incarnate by the word of God and had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so too, as we have been taught, the food which has been made into the Eucharist by the Eucharistic prayer set down by him, and by the change of which our blood and flesh is nurtured, is both the flesh and the blood of that incarnated Jesus" (First Apology 66:1-20 ). | |||

| ===Early Middle Ages=== | |||

| The descriptions of the Mass liturgy in Rome by ] (died c. 235) and ] (died c. 250) are similar to Justin's. | |||

| Before the pontificate of ] (590–604), the Roman Mass rite underwent many changes, including a "complete recasting of the ]" (a term that in this context means the ] or Eucharistic Prayer).<ref group=note>"...the Eucharistic prayer was fundamentally changed and recast" {{Citation| title=Catholic Encyclopedia|contribution=Liturgy of the Mass|publisher=New advent|url= http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09790b.htm}}.</ref> At the time of Gregory I, regional customisation of liturgies were encouraged in missionary areas: according to ] Gregory instructed ] to select "any customs in the Roman or the Gaulish Church or any other Church which may be more pleasing to Almighty God", and to teach them to the church of the English.<ref name=hen>{{cite journal |last1=Hen |first1=Yitzhak |title=The liturgy of St Willibrord |journal=Anglo-Saxon England |date=1997 |volume=26 |pages=41–62 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/44510515 |issn=0263-6751}}</ref>{{rp|45}} | |||

| In Gaul, the ] period in (approx. 500-750) has been called "the experimental age of liturgy," with the propers constructed freely: according to historian Yitzhak Hen "each bishop, abbot or priest was free to choose the prayers he found suitable."<ref name=hen />{{rp|57}} Cross-pollenation and recycling of liturgical prayers was common, as priests and bishops took sacramentaries (manuscripts of liturgical prayers) between regions, and new prayers were composed.<ref name=hen/>{{pn|date=July 2024}} | |||

| ==Early changes== | |||

| It is unclear when the language of the celebration changed from Greek to ]. ] (190–202), an African, may have been the first to use Latin in the liturgy in Rome. Others think Latin was finally adopted nearly a century later.<ref>"The complete and definitive Latinization of the Roman liturgy seems to have happened toward the middle of the fourth century" (Christine Mohrmann, ''Études sur le latin des chrétiens'' (Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 4 volumes1961-77), vol. I, p. 54).</ref> The change was probably gradual, with both languages being used for a while.<ref>"The first Christians in Rome were chiefly people who came from the East and spoke Greek. The founding of Constantinople naturally drew such people thither rather than to Rome, and then Christianity at Rome began to spread among the Roman population, so that at last the bulk of the Christian population in Rome spoke Latin. Hence the change in the language of the liturgy. ... The liturgy was said (in Latin) first in one church and then in more, until the Greek liturgy was driven out, and the clergy ceased to know Greek. About 415 or 420 we find a Pope saying that he is unable to answer a letter from some Eastern bishops, because he has no one who could write Greek" (Alfred Plummer, Conversations with Dr. Döllinger 1870-1890, ed. Robrecht Boudens (Leuven University Press, 1985), p. 13).</ref> | |||

| Numerous regional styles of chant thrived, including ], ], ] (still in use) and ]. Following Gregory I came substantial changes in what became known as ]. | |||

| Before the pontificate of ] (590–604), the Roman Mass rite underwent many changes, including a "complete recasting of the ]" (a term that in this context means the ] or Eucharistic Prayer), "... the Eucharistic prayer was fundamentally changed and recast" (''Catholic Encyclopedia'', "Liturgy of the Mass"), the number of Scripture readings was reduced, the prayers of the faithful were omitted (leaving, however, the "]" that once introduced them), the ] was moved to after the ], and there was a growing tendency to vary, in reference to the feast or season, the prayers, the ], and even the Canon. | |||

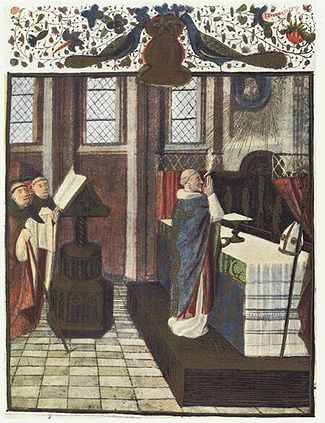

| ] conducting mass in the side chapel of a cathedral: he is elevating the host. ] (bearded, crowned) is kneeling alongside on left. Charlemagne had a sin too terrible to confess. A winged angel from heaven is coming down top-left, with a scroll naming the sin which, through St Gilles' intercession, will be forgiven.]] | |||

| With regard to the Roman Canon of the Mass, the prayers beginning ''Te igitur, Memento Domine'' and ''Quam oblationem'' were already in use, even if not with quite the same wording as now, by the year 400; the ''Communicantes'', the ''Hanc igitur'', and the post-consecration ''Memento etiam'' and ''Nobis quoque'' were added in the fifth century.<ref>Josef Andreas Jungmann, S.J., ''Missarum Sollemnia - Eine genetische Erklärung der römischen Messe'' (Herder, Vienna 1949), volume I, pages 70-71; cf. Hermannus A. P. Schmidt, ''Introductio in Liturgiam Occidentalem'' (Herder, Rome-Freiburg-Barcelona 1960), page 352</ref> | |||

| In the eighth century the Meringovian dynasty had been replaced by the ] in Frankish Gaul. In the late eighth century, ] ordered the Roman chant be used throughout his domains.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hen |first1=Ytzhak |title=Medieval Manuscripts in Transition: Tradition and Creative Recycling |date=2006 |publisher=Leuven University Press |isbn=978-90-5867-520-0 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qdxv4.11}}</ref>{{rp|150}} However, some elements of the preceding ]s were fused with it north of the Alps, and the resulting mixed rite was introduced into Rome under the influence of the emperors who succeeded Charlemagne. Gallican influence is responsible for the introduction into the Roman rite of dramatic and symbolic ceremonies such as the blessing of candles, ashes, palms, and much of the ] ritual.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.liturgica.com/html/litWLCarol.jsp|title=The Franks Adopt the Roman Rite|publisher=Liturgica|access-date=January 31, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131024132337/http://liturgica.com/html/litWLCarol.jsp|archive-date=2013-10-24|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| During the Carolingian period, the language diverged with Latin going back to its classical forms and the vernacular recognized as separate tongues. Consequently, the Council of Tours (813) mandated that sermons be given in the Romance or Teutonic vernacular.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Casanellas |first1=Pere |title=Medieval Catalan translations of the Bible |journal=TERRADO, Xavier; SABATÉ, Flocel (eds.). Les veus del sagrat (Verum et Pulchrum Medium Aevum; 8), pp. 15–34. |date=1 January 2014 |url=https://www.academia.edu/10897845/Medieval_Catalan_translations_of_the_Bible}}</ref> | |||

| Pope Gregory I made a general revision of the liturgy of the Mass, "removing many things, changing a few, adding some," as his biographer, ], writes. He is credited with adding a phrase to the ], and he placed the ] immediately after the Canon, as he himself wrote. | |||

| The ] and musical settings of the Mass were divided into | |||

| ==Middle Ages== | |||

| *the parts that do not change during the year (the ]: the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei), and | |||

| Towards the end of the eighth century ] ordered the Roman rite of Mass to be used throughout his domains. However, some elements of the preceding ]s were fused with it north of the Alps, and the resulting mixed rite was introduced into Rome under the influence of the emperors who succeeded Charlemagne. Gallican influence is responsible for the introduction into the Roman rite of dramatic and symbolic ceremonies such as the blessing of candles, ashes, palms, and much of the ] ritual. | |||

| *the parts that belonged to the particular day and occasion (the ]): Introit, Gradual, Alleluia, Offertory, Communion.<ref>{{cite web |title=Renaissance Mass (chants) |url=http://tegrity.columbiabasin.edu/classes/MUS115RP/Renaissance_MASS/mobile_pages/index.html |website=tegrity.columbiabasin.edu}}</ref> | |||

| The major difference between the various rites or uses was not the basic structure or components of the ordinary parts of the liturgy, but of different arrangements, selection and allocation of prayers on different days, as well as mention of regionally-popular saints, and different ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Church |first1=Catholic |last2=Wilson |first2=Henry Austin |title=Liber sacramentorum Romanae Ecclesiae |date=1894 |publisher=Clarendon Press |language=la}}</ref>{{rp|Preface}} | |||

| The recitation of the ] (]) after the ] is attributed to the influence of Emperor ] (1002–1024). Gallican influence explains the practice of incensing persons, introduced in the eleventh or twelfth century; "before that time incense was burned only during processions (the entrance and Gospel procession)." Private prayers for the priest to say before Communion were another novelty. About the thirteenth century, an elaborate ritual and additional prayers of French origin were added to the ], at which the only prayer that the priest in earlier times said was the ]; these prayers varied considerably until fixed by ] in 1570. Pope Pius V also introduced the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar, previously said mostly in the sacristy or during the procession to the altar as part of the priest's preparation, and also for the first time formally admitted into the Mass all that follows the '']'' in his edition of the Roman Missal. Later editions of the Roman Missal abbreviated this part by omitting the Canticle of the Three Young Men and Psalm 150, followed by other prayers, that in Pius V's edition the priest was to say while leaving the altar.<ref>''Missale Romanum. Editio Princeps'' (ISBN 88-209-2547-8), pages 291-292</ref> | |||

| ===Late Middle Ages=== | |||

| From 1474 until Pope Pius V's 1570 text, there were at least 14 different printings that purported to present the text of the Mass as celebrated in Rome, rather than elsewhere, and which therefore were published under the title of "Roman Missal". These were produced in Milan, Venice, Paris and Lyon. Even these show variations. Local Missals, such as the Parisian Missal, of which at least 16 printed editions appeared between 1481 and 1738, showed more important differences.<ref>''Missale Romanum. Editio Princeps'' (ISBN 88-209-2547-8), Introduction, pages XV-XVI</ref> | |||

| Towards the end of the first millennium, ], previously a secular instrument, was introduced as did more complicated singing of components of the Mass by choirs.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Caldwell |first1=John |title=The Organ in the Medieval Latin Liturgy, 800-1500 |journal=Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association |date=1966 |volume=93 |pages=11–24 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/765896 |issn=0080-4452}}</ref> Important liturgies might be preceded, followed or interrupted by elaborate processions with songs, dramatic rituals involving props, and acted plays or tableau, with the laity trained to understand the symbolism.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bedingfield |first1=M. Bradford |title=Reinventing the Gospel: Ælfric and the Liturgy |journal=Medium Ævum |date=1999 |volume=68 |issue=1 |pages=13–31 |doi=10.2307/43630122 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/43630122 |issn=0025-8385}}</ref> In several locations, the story of the ] would be enacted by three costumed men who would follow a star through the church, search at various locations, until finding the altar, while singing the Gospel alternatively and polyphonically.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Göllner |first1=Theodor |title=The Three-Part Gospel Reading and the Medieval Magi Play |journal=Journal of the American Musicological Society |date=1971 |volume=24 |issue=1 |pages=51–62 |doi=10.2307/830892 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/830892 |issn=0003-0139}}</ref>{{rp|54}} | |||

| The Roman Missal that Pope Pius V issued at the request of the ], gradually established uniformity within the Western Church after a period that had witnessed regional variations in the choice of Epistles, Gospels, and prayers at the Offertory, the Communion, and the beginning and end of Mass. With the exception of a few dioceses and religious orders, the use of this Missal was made obligatory, giving rise to the 400-year period when the Roman-Rite Mass took the form now known as the ]. | |||

| The recitation of the ] (]) after the ] is attributed to the influence of Emperor ]. Gallican influence explains the practice of incensing persons, introduced in the eleventh or twelfth century; "before that time incense was burned only during processions (the entrance and Gospel procession)".<ref>{{Citation|title=Fathers|url= http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0126.htm|publisher=New Advent}}</ref> Private prayers for the priest to say before Communion were another novelty. About the thirteenth century, an elaborate ritual and additional prayers of French origin were added to the ]: previously, the only prayer said by the priest was the ]; these prayers varied considerably until fixed by ] in 1570.<ref group=note>{{Citation |quote=We decided to entrust this work to learned men of our selection. They very carefully collated all their work with the ancient codices in Our Vatican Library and with reliable, preserved or emended codices from elsewhere. Besides this, these men consulted the works of ancient and approved authors concerning the same sacred rites; and thus ''they have restored the Missal'' itself to the original form and rite of the holy Fathers. When this work has been gone over numerous times and ''further emended'', after serious study and reflection, We commanded that the finished product be printed and published|first=Antonio Michele|last=Ghislieri|author-link=Pope Pius V|type=bull|title= Quo primum|date=14 July 1570|url=http://www.papalencyclicals.net/Pius05/p5quopri.htm|publisher = Papal encyclicals}}.</ref> The rites had some differences in the prayers on the boundaries of the Mass: Pre-Tridentine prayers said mostly in the sacristy or during the procession to the altar as part of the priest's preparation were formalized in the 1570 missal of Pope Pius V as the ''Prayers at the Foot of the Altar''; prayers that followed the '']'' changed or changed position (for example, in the 1570 edition, the ''Canticle of the Three Young Men'' and Psalm 150 in Pius V's edition the priest was to say while leaving the altar were later omitted.){{Sfn|Sodi|Triacca|1998|pp=291–92}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ===Renaissance=== | |||

| ==Comparison of the Mass, c. 400 and 1000 AD== | |||

| Between 1478 and 1501, the bishops of 52 dioceses, including the primates of France, Castile, England, the Holy Roman Empire and Poland each independently published, in print, official liturgical texts for their diocese, because of the extent of parish and monastery variation. <ref group=note>At least 107 of these still exist: regions also included modern Hungary, Sweden, Switzerland and even two dioceses in the Kingdom of Naples. Furthermore, at least 490 editions were made by private publishers before 1501 for clergy. {{cite journal |last1=Nowakowska |first1=N. |title=From Strassburg to Trent: Bishops, Printing and Liturgical Reform in the Fifteenth Century* |journal=Past & Present |date=1 November 2011 |volume=213 |issue=1 |pages=3–39 |doi=10.1093/pastj/gtr012|doi-access=free }}</ref> In some places, this involved stripping variations back to the Cathedral's missal; however in others it involved adding material for new saints, offices and customs. | |||

| From 1474 until Pope Pius V's 1570 text, there were at least 14 different printed editions that purported to present the text of the Mass as celebrated in Rome, rather than elsewhere, and which therefore were published under the title of "''Roman Missal''" ({{langx|la|Missale romanum}}.) These were produced in Milan, Venice, Paris and Lyon. Even these show variations. Local Missals, such as the Parisian Missal, of which at least 16 printed editions appeared between 1481 and 1738, showed more important differences.{{Sfn|Sodi|Triacca|1998|pp=XV–XVI}} The Milanese ''Roman Missal'' of 1474, which reproduces the Papal Chapel missal of the late 1200s, "hardly differs at all" from the initial Tridentine missal promulgated in 1570, apart from local feasts.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lauren Pristas |title=Collects of the Roman Missals A Comparative Study of the Sundays in Proper Seasons Before and After the Second Vatican Council |date=2013 |publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=9780567033840 |page=67}}</ref> | |||

| ===Other rites=== | |||

| Apart from the Roman rite, before 1570 many other liturgical rites were in use, not only in the ], but also in the West. Some ], such as the ], were unrelated to the ] which Pope Pius V revised and ordered to be adopted generally, and even areas that had accepted the Roman rite had introduced changes and additions. As a result, every ecclesiastical province and almost every diocese had its local use, such as the ], the ] and the ] in England. In France, there were strong traces of the ]. With the exception of the relatively few places where no form of the Roman Rite had ever been adopted, the ] remained generally uniform, but the prayers in the "Ordo Missae", and still more the "Proprium Sanctorum" and the "Proprium de Tempore", varied widely.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10354c.htm|last=Thurston|first=Herbert|title=Missal|encyclopedia=Catholic Encyclopedia|year=1913}}</ref> | |||

| ===Languages=== | |||

| In most countries, the language used for celebrating Pre-Tridentine Masses was Latin, which had become the language of the Roman liturgy in the late 4th century. However, there have been exceptions:<ref name="Gratsch1958">{{cite journal |author-last=Gratsch |author-first=Edward J. |title=The Language of the Roman Rite |journal=American Ecclesiastical Review |volume=139 |issue=4 |date=October 1958 |pages=255–260 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2MvNAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA255}}</ref> | |||

| * In ] and parts of ] in ], the Roman Rite liturgy was celebrated in ] from the time of ], and authorization for use of this language was extended to some other Slavic regions between 1886 and 1935.<ref name="CED" group=note>"The right to use the ] {{sic}} language at Mass with the Roman Rite has prevailed for many centuries in all the south-western Balkan countries, and has been sanctioned by long practice and by many popes." {{cite web |last= Krmpotic |first= M.D. |title=Dalmatia |year=1908 |access-date=March 25, 2008 |publisher= ] |url= http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04606b.htm }}</ref><ref name="CRD" group=note>"In 1886 it arrived to the ], followed by the ] in 1914, and the ] in 1920, but only for ] of the main ]s. The 1935 concordat with the ] anticipated the introduction of the Slavic liturgy for all Croatian regions and throughout the entire state." {{cite web |last= Japundžić |first= Marko |title=The Croatian Glagolitic Heritage |year=1997 |access-date=March 25, 2008 |publisher= Croatian Academy of America |url= http://www.croatianhistory.net/etf/japun.html }}</ref> | |||

| * In the 14th century, ] missionaries converted a monastery near Qrna, ] to Catholicism, and translated the liturgical books of the ], a variant of the Roman Rite, into ] for the community's use. The monks were deterred from becoming members of the Dominican Order itself by the severe ] requirements of the Dominican Constitutions, as well as the prohibition on owning any land other than that on which the monastery stood, and therefore became the Order of the United Friars of St. Gregory the Illuminator, a new order confirmed by ] in 1356 whose Constitutions were similar to the Dominicans' except for these two laws. This order established monasteries over a vast amount of territory in Greater and Lesser Armenia, Persia, and Georgia, using the Dominican Rite in Armenian until the end of the order's existence in 1794.<ref name="Bonniwell1945">{{cite book |author-last=Bonniwell |author-first=William R. |title=A History of the Dominican Liturgy, 1215–1945 |edition=2nd |location=New York |publisher=Joseph F. Wagner, Inc. |year=1945 | pages=207–208 |url=https://media.musicasacra.com/dominican/bh.pdf#page=110}}</ref><ref name="Gratsch1958"/> | |||

| * On February 25, 1398, ] also authorized ] to found a monastery in Greece where Mass would be celebrated in ] according to the Dominican Rite, and ] translated the Dominican missal into Greek in pursuance of the plan, but nothing further is known of this undertaking.<ref name="Bonniwell1945"/><ref name="Gratsch1958"/> | |||

| At various times there were calls for the prayers of the Mass to be in the vernacular, such as by ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Pabel |first1=Hilmar M. |title=Promoting the Business of the Gospel: Erasmus' Contribution to Pastoral Ministry |journal=Erasmus of Rotterdam Society Yearbook |date=1995 |volume=15 |issue=1 |pages=53–70 |doi=10.1163/187492795X00053}}</ref>{{rp|67}} | |||

| ===Legacy=== | |||

| The Pre-Tridentine Mass survived post-Trent in some Anglican and Lutheran areas with some local modification from the basic Roman rite until the time when worship switched to the vernacular. Dates of switching to the vernacular, in whole or in part, varied widely by location. In some Lutheran areas this took three hundred years, as choral liturgies were sung by schoolchildren who were learning Latin.<ref></ref> | |||

| == Vernacular and laity in the medieval and Reformation eras == | |||

| Historian Virginia Reinburg has noted that the medieval eucharistic liturgy as experienced by (French) lay people, and shown in their prayer books, was a distinct experience from that of the clergy and the clerical missal.<ref name="reinburg">{{cite journal |last1=Reinburg |first1=Virginia |title=Liturgy and the Laity in Late Medieval and Reformation France |journal=The Sixteenth Century Journal |date=1992 |volume=23 |issue=3 |pages=526–547 |doi=10.2307/2542493 |jstor=2542493 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2542493 |issn=0361-0160}}</ref>{{rp|529}} | |||

| {{Blockquote|"What the lay prayer books reveal—and missals do not—is the pre-Reformation mass as a ritual drama in which the priests and the congregation had distinct, but equally necessary parts to play."<ref name="reinburg" />{{rp|530}} |source= Reinberg}} | |||

| ===Setting=== | |||

| In the ] period, the Mass was increasingly performed as sacred drama, with the people as active participants not passive spectators:<ref>{{cite book |last1=Rose |first1=Els |title=Plebs sancta ideo meminere debet. The Role of the People in the Early Medieval Liturgy of Mass |date=2019 |publisher=De Gruyter |url=https://www.academia.edu/60933512}}</ref>{{rp|460}} Archbishop ] of Metz (c.830) was accused of imparting "theatrical elements and stage mannerisms" to the ] liturgy.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Calkins |first1=Robert G. |title=Liturgical Sequence and Decorative Crescendo in the Drogo Sacramentary |journal=Gesta |date=1986 |volume=25 |issue=1 |pages=17–23 |doi=10.2307/766893 |jstor=766893 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/766893 |issn=0016-920X}}</ref> | |||

| The medieval lay experience was often highly sensory:<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Williamson |first1=Beth |title=Sensory Experience in Medieval Devotion: Sound and Vision, Invisibility and Silence |journal=Speculum |date=2013 |volume=88 |issue=1 |pages=1–43 |jstor=23488709 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/23488709 |issn=0038-7134}}</ref> churches featured chanting and singing, bells, high-tech organs, incense, busy paintings, brilliant robes, rare colours, shiny utensils, clouds of saints and angels, and stained-glass light, not to mention the taste of the host, the splashing of baptism, or even, perhaps, the feel of the silk of the priest's violet ] in ].<ref group=note>There is an obscure report of an improvised pre-medieval practise of a bishop to whack penitants with his ] in proportion to their sins. {{cite journal |last1=Murray |first1=Alexander |title=Confession before 1215 |journal=Transactions of the Royal Historical Society |date=1993 |volume=3 |pages=51–81 |doi=10.2307/3679136 |jstor=3679136 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3679136 |issn=0080-4401}}</ref> Some larger churches even had ] to delight and inspire the congregation.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Swift |first1=Christopher |title=Robot Saints |journal=Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural |date=2015 |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=52–77 |doi=10.5325/preternature.4.1.0052 |jstor=10.5325/preternature.4.1.0052 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/preternature.4.1.0052 |issn=2161-2196}}</ref> | |||

| ]{{clear}} | |||

| By the ], churches were full of depictions in art of biblical and hagiographical people and events to illustrate notable days in the church calendar; cathedrals could have artwork on a monumental scale: for example ] and ]'s frescoes in ] are based around the liturgy for the ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=James |first1=Sara Nair |title=Penance and Redemption: The Role of the Roman Liturgy in Luca Signorelli's Frescoes at Orvieto |journal=Artibus et Historiae |date=2001 |volume=22 |issue=44 |pages=119–147 |doi=10.2307/1483716 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483716 |issn=0391-9064}}</ref> In Northern Europe, such art rarely survived the ] of the ]. | |||

| ===Lay experience=== | |||

| The priests and deacons attended to the ceremony in the ] or ]: | |||

| {{Blockquote|"For the priest, the most important important parts of the ] would be scripture readings, offertory of bread and wine, consecration, and priest's communion."<ref name="reinburg" />{{rp|532}} |source= Reinberg}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The laity enjoyed the ceremony from the ]: | |||

| {{Blockquote| For the lay congregation, however, the mass was a series of collective devotions and ritual actions; the most important elements would be the Gospel, ''prône'' ("bidding prayers", see below), offertory procession, and distribution of the '']'' at the end of the mass.The laity's mass was less sacrifice and sacrament than a communal rite of greeting, sharing, giving, receiving and making peace."<ref name="reinburg" />{{rp|532}}<ref group=note>"The central contention of (John) Bossy’s ''Christianity in the West'' was that medieval Christianity had been fundamentally concerned with the creation and maintenance of peace in a violent world. “Christianity” in medieval Europe denoted neither an ideology nor an institution, but a community of believers whose religious ideal—constantly aspired to if seldom attained—was peace and mutual love. The sacraments and sacramentals of the medieval Church were not half-pagan magic, but instruments of the “social miracle,” rituals designed to defuse hostility and create extended networks of fraternity, spiritual “kith and kin,” by reconciling enemies and consolidating the community in charity." {{cite web |last1=Duffy |first1=Eamon |title=The End of Christendom |url=https://www.firstthings.com/article/2016/11/the-end-of-christendom |website=First Things |access-date=27 November 2023 |language=en |date=1 November 2016}}</ref> |source= Reinberg}} | |||

| Lay prayer-books, for the educated middle and upper classes, not only gave the communal actions of the liturgy, but provided almost an unofficial parallel liturgy of silent prayers and devotions for the laity to perform in between and in preparation for the actions.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Salisbury |first1=Matthew Cheung |title=Worship in medieval England |date=2018 |publisher=Arc humanities press |location=Leeds |isbn=9781641891158}}</ref>{{rp|59}} | |||

| {{blockquote|"For the congregation, which would not have heard the sacred words "''This is my body''", the ] was the emotional climax of the mass. It was also the focus of popular liturgical devotion. Virtually no lay books actually explain the consecration(or) the doctrine of transubstantiation.Yet the ritual of the elevation was intended to express the ] of Christ on the altar."<ref name="reinburg" />{{rp|533}} |source= Reinberg}} | |||

| Notable parts of the lay experience of the liturgy (especially the Sunday Mass) included: | |||

| * The reading of the Gospel could be an elaborate and reverential event, with all people standing and genuflecting at any (Latin) mention of the name Jesus. ] mentioned approvingly that in his day it was the practice, after the reading, for the sumptuous ] (Gospel book) to be carried around the people and kissed by all in adoration.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Dyer |first1=Joseph Henry |title=Readers and hearers of the word: the cantillation of scripture in the Middle Ages |date=2022 |publisher=Brepols |location=Turnhout |isbn=978-2-503-59287-9}}</ref>{{rp|197}} | |||

| * The ''Prône'' ({{langx|fr|Prières du Prône}}, {{Langx|de|Pronaus}}, {{langx|la|pronaüm}}) mentioned above was a vernacular service that came to be included as a para-liturgy in medieval Latin High Masses (typically at the Sermon), dating back at least to ] (d. 915).<ref name=jungmann />{{rp|487}} It was named after the ] at the ] entrance, where the priest would speak in the local language.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Weston |first1=Lindy |title=Gothic Architecture and the Liturgy in Construction |date=1 June 2018 |s2cid=194823224 }}</ref>{{rp|118}} It could include well-known prayers, translations of the Gospel and Epistle, the homily nominally on the Gospel, catechetical instruction,<ref>{{cite web |title=Prône {{!}} Encyclopedia.com |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/prone |website=www.encyclopedia.com}}</ref><ref name=lualdi>{{cite journal |last1=Lualdi |first1=Katharine J. |title=Persevering in the Faith: Catholic Worship and Communal Identity in the Wake of the Edict of Nantes |journal=The Sixteenth Century Journal |date=2004 |volume=35 |issue=3 |pages=717–734 |doi=10.2307/20477042 |jstor=20477042 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/20477042 |issn=0361-0160}}</ref>{{rp|721}} comprehensive prayers for the living and the dead,<ref group=note>Corresponding to the Anglo-Saxon/Anglo-Norman/Middle English "] the beads" {{cite book |last1=Rock |first1=Daniel |title=The Church of Our Fathers as Seen in St. Osmund's Rite for the Cathedral of Salisbury: With Dissertations on the Belief and Ritual in England Before and After the Coming of the Normans |date=1849 |publisher=C. Dolman |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IQYXAAAAIAAJ&dq=%22Pr%C3%B4ne%22++bidding++mass++catholic&pg=PA354 |language=en}}</ref>{{rp|352}} acknowledging benefactors, open confession (for ]),<ref name=jungmann />{{rp|493}} teaching the diocese's domestic morning prayer,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Palacios |first1=Joy Kathleen |title=Preaching for the Eyes: Priests, Actors, and Ceremonial Splendor in Early Modern France |date=2012 |publisher=UC Berkeley |url=https://escholarship.org/uc/item/42m4676v |access-date=13 October 2023 |language=en}}</ref>{{rp|142}} announcements including weddings, upcoming ] and ],<ref name=jungmann />{{rp|491}} village assembly meetings, royal or seigneurial decrees of note, and salutory crime reports.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bergin |first1=Joseph |title=Church, Society and Religious Change in France, 1580-1730 |date=25 August 2009 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-16106-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yW51qNLPPx8C |language=en}}</ref>{{rp|281}} It was regarded as vital by laypeople even into the post-Reformation period.<ref name=lualdi />{{rp|727}} | |||

| :It was universally folded into the Sunday Mass by the ] and with collated bidding prayers such as ]' ''{{langx|de|Allgemeines Gebet}}''.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Hofschulte |first1=Benno |title="Allgemeines Gebet" |url=https://www.mariens-hilfe.org/allgemeines-gebet/ |website=Deutschland braucht Mariens Hilfe |access-date=12 October 2023 |language=en |date=4 June 2020}}</ref> (In Ireland (c. 1785), "the prône" became the name for a book of prepared sermons and prayers which were "a key tool in remodelling older oral versions of the (vernacular portion of the) liturgy to newer standardised ones."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Millerick |first1=Martin |title=The Roman Catholic Communities of Cloyne Diocese, Co. Cork, 1700 -1830. |date=2015 |publisher=Maynooth University |url=https://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/9120/1/Cloyne.pdf}}</ref>{{rp|93}}) | |||

| * Written and spoken Latin had diverged enough that by 813 the ] instructed that homilies should be given in the local spoken vernacular, whether Romance or Teutonic.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Casanellas |first1=Pere |title=Medieval Catalan translations of the Bible |date=1 January 2014 |url=https://www.academia.edu/10897845/Medieval_Catalan_translations_of_the_Bible}}</ref> It was the common practice<ref group=note>See, for example, the Middle English ''Old Kentish Sermons'' (c. 12th century) in {{cite web |last1=Morris |first1=Richard |title=An Old English miscellany containing a bestiary, Kentish sermons, Proverbs of Alfred, religious poems of the thirteenth century |url=https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/cme/AHA6129.0001.001/1:4?rgn=div1;view=fulltext |date=2006}}</ref> that at the beginning of the vernacular homily (sermon), the Gospel reading and perhaps the Epistle reading would be rendered loosely in the vernacular by the priest.<ref name=jungmann/>{{rp|408}} <ref>Nico Fassino (2023). ''The Epistles & Gospels in English: A history of vernacular scripture from the pulpit, 971-1964.'' Part of the Hand Missal History Project. </ref> In a pinch, this translation could be used as the sermon itself: inability or slackness to preach in the vernacular was repeatedly regarded as a failure of a priest's or bishop's duty,{{refn|group=note|This concern mirrors that of ] who, in 769, had ordered each priest every ] to "report and explain to the bishop the method and procedure [in which he | |||

| performs] his ministry, concerning baptism, the Catholic faith, the prayers, and the ''ordo'' of the Mass.Priests, who do not know properly to perform their ministry and are not too busy to learn with all their energy according to the order of their bishops, or seem to disregard the canons, must be removed from the office itself, until they should know these completely without any mistakes."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hen |first1=Yotzhak |title=Medieval Manuscripts in Transition: Tradition and Creative Recycling |date=2006 |publisher=Leuven University Press |isbn=978-90-5867-520-0 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qdxv4.11}}</ref>{{rp|149}} }} but must have happened over the centuries: ] quoted English bishop ]: | |||

| {{quote|If any priest says he cannot preach (i.e. give composed or extemporized vernacular sermons), one remedy is: resign; Another remedy, if he does not want that, is: record (i.e., recollect or write out)<ref>{{cite web |title=Meanings & Definitions of English Words: Record |url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/record#word-history-and-origins |website=Dictionary.com |language=en}}</ref> he in the week the naked text of the Sunday's gospel, that he understands the gross story, and tell it to the people, that is if he understands Latin and does it every week of the year. And if he understands no Latin, go he to one of his neighbours that understands, which will charitably expound it to him, and thus edify he his flock|source=Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln, ''Scriptum est de Levitis'' (c. 1240)<ref>{{cite book |last1=Deanesly |first1=Margaret |author-link=Margaret Deanesly |title=The Lollard Bible and other medieval Biblical versions |date=1920 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |url=https://archive.org/details/lollardbibleothe00deanuoft/page/140/mode/2up?view=theater}}</ref>{{rp|141,442}}}} | |||

| * At times, vernacular hymns were sung.<ref name=jungmann/>{{rp|147,440}} For example, a {{langx|de|Leis}} hymn, sung after the sermon from the 12th Century.<ref name=jungmann>{{cite book |last1=Jungmann |first1=Josef A. |last2=Brunner |first2=Francis A. |title=The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum Sollemnia) |date=1951 |url=https://archive.org/details/JungmannMassOfTheRomanRite}}</ref>{{rp|486}} | |||

| * The ] was bread given in the general offering by the laity, blessed by the priest, and given back to the laity for devotional use and as alms, especially when lay communion was infrequent. | |||

| * Another ] activity performed with the laity was the ] and ] with its emphasis on mutual forgiveness.<ref name="reinburg" />{{rp|539}} | |||

| There are few records about the liturgy in remote, rural areas. | |||

| ==Comparison of the Mass, c. 200 to c. 2000 AD== | |||

| This table is indicative. Depending on calendar, occasion, participants, region and period, some parts might be augmented or commented on ('']'')<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Friel |first1=David M. |title=The Sequences of the Missale Romanum: Popular Works of Liturgical Creativity |journal=Adoremus Bulletin |date=1 January 2017 |url=https://www.academia.edu/35989660}}</ref> or removed or rearranged or varied from standard forms. The specific collects, readings, sequences, psalms, saints, blessings, and performance instructions (or ]), similarly vary. The ''Canon of the Mass'' (the key section with consecration and elevation) had less textual variation in the West, and often was the standard ]. | |||

| Such local variants are called '']'' (of a Rite) when relatively minor, or a new ''Rite'' when relatively major, and typically reflect the living practice at a cathedral, whose liturgical books might then be copied by other dioceses. Mixing was common: a cathedral might adopt the Liturgy from one Rite, but keep its traditional Rubrics, Sequences etc., and use the Psalms or Calendar of some other rite. Over time, the parts may be grouped or re-named to reflect the contemporary theological or pastoral priorities, but were typically known by the first words of the Latin of the prayer. | |||

| For example, the ] has different prayers, prefaces, readings, calendar and vestments to the Roman Rite. It omits the Agnus Dei. The Gesture of Peace occurs before the Offertory.<ref>{{cite web |title=Ambrosian rite and Roman rite: let's see the differences together |url=https://www.holyart.com/blog/religious-items/ambrosian-rite-and-roman-rite-lets-see-the-differences-together/ |website=Holyart.com Blog |date=7 July 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=A detailed explanation of the Ambrosian rite and San Simeon Piccolo |url=https://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2007/03/detailed-explanation-of-ambrosian-rite.html |website=New Advent}}</ref> | |||

| Note: Below, "Gifts" primarily means the unconsecrated bread, wine and water. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| |- valign=top | |- valign=top | ||

| ! c. 200-350 <ref name=maskell />{{rp|xvi,xxxi}}<ref>{{cite web |last1=Muñoz |first1=Edgard Abraham Alvarez |title=The Shape of the Liturgy (Review) |url=https://www.academia.edu/34178901 |access-date=20 October 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ! c. 400 | |||

| ! c. 400 <ref name=Hoppin>Roman Rite, {{Citation |last=Hoppin |first=Richard |title=Medieval Music |pages=119, 122 |year=1977 |place=] |publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| ! c. 1000 | |||

| ! c. 1000 <ref name=Hoppin /> | |||

| ! c. 2000 <ref>Roman Rite, {{cite web |title=Order of Mass |url=https://www.usccb.org/prayer-and-worship/the-mass/order-of-mass |website=www.usccb.org |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |Greek, then Latin||Latin||Latin||Vernacular | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | '''Synaxis''' (Meeting) | |||

| | '''Mass of the Catechumens''' || '''Fore-Mass''' | |||

| | '''Misa of the Catechumens''' || '''Fore-Mass''' || '''Liturgy of the Word''' | |||

| |- valign=top | |- valign=top | ||

| | Greeting: "Grace of our Lord" | |||

| | Introductory greeting || Entrance ceremonies | | Introductory greeting || Entrance ceremonies | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| Line 48: | Line 144: | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| | Introductory Rites | |||

| * ] (Introit) | |||

| * Greeting: "Grace of our Lord" | |||

| * ] (Kyrie) | |||

| * ] (Gloria) | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | Lessons (Readings)<br> | |||

| | <br> Lesson 1: the ]<br>] psalm<br>Lesson 2: ]<br>Responsorial psalm<br><br><br>Lesson 3: ] | |||

| interspersed with Psalmody | |||

| || Service of readings<br><br> | |||

| | | |||

| *] | |||

| * Lesson 1: the ] | |||

| * ] psalm | |||

| * Lesson 2: ] | |||

| * Responsorial psalm | |||

| * Lesson 3: ] | |||

| || Service of readings | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| *] or ] | *] or ] | ||

| * ] (optional) | * ] (optional) | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| | Liturgy of the Word | |||

| * First reading (OT) | |||

| * ] Psalm | |||

| * Second reading (NT) | |||

| * Gospel acclamation | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | | |||

| | ] || ] (optional) | |||

| Sermon - vernacular "words of comfort" | |||

| | ] in ] | |||

| | | |||

| Vernacular ] or paraphrase of Gospel reading | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | | |||

| | Prayer<br>Dismissal of the ]s || ]<br>"]" | |||

| * Dismissal of "hearers" and unbelievers<ref group=note>Maskell suggests that the dismissals and simplicity are caused both because of unwillingness to "cast pearls before swine" (p. xxviii) and immanent danger from persecution (p. xxi).</ref> | |||

| * Bidding prayers | |||

| * ] for the ''catechumens''<br> and their dismissal | |||

| * Collect for the ''energumens''<br> and their dismissal | |||

| * Collect for the ''competentes'' and ''illuminandi''<br>(candidates for baptism)<br> and their dismissal | |||

| * Collect for the ''penitentes''<br> and their dismissal | |||

| | | |||

| * Prayer | |||

| * Dismissal of the ]s | |||

| | | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** (Nicene Creed introduced 1014) | |||

| * "]" | |||

| ** (Vernacular bidding prayers/Prône) | |||

| | | |||

| * Dismissal of the ]s | |||

| * ] (Credo) | |||

| * ] (Oremus) | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | '''Eucharist''' (Thanksgiving) | |||

| | '''Communion of the Faithful''' || '''Sacrifice-Mass''' | |||

| | '''Communion of the Faithful''' || '''Sacrifice-Mass''' || '''Liturgy of the Eucharist''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | | |||

| * Priestly prayers | |||

| * Washing of hands | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Sign of cross | |||

| | Offering of gifts<br><br><br><br>Prayer over the offerings || Offertory rites | | Offering of gifts<br><br><br><br>Prayer over the offerings || Offertory rites | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * Prayers and ] 25 | * Prayers and ] 25 | ||

| * Little Canon ( |

* Little Canon (Preparation of gifts) | ||

| * ] | * ] (Preparation of the altar) | ||

| | | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | | |||

| Anaphora (Canon): | |||

| * Collective prayer | |||

| * Consecration | |||

| * Thanksgiving | |||

| * ] | |||

| | ]s<br><br><br><br> || ]s | | ]s<br><br><br><br> || ]s | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| ** ] | |||

| | ]s | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (Sanctus) | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | | |||

| | ] rites<br><br><br>] accompanying communion<br>Prayer<br><br> || Communion cycle | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Distribution of elements | |||

| | ] rites | |||

| * ] accompanying Communion | |||

| * Communion | |||

| ** Leavened bread loaves, from people's offering, in hand | |||

| ** Wine and water, frequently drunk with ] (or '']'') or spoon<ref>{{cite web |last1=Belcher |first1=Kimberly Hope |title=History of infant communion, part 2: Medieval and modern periods (500-2015 AD) |url=https://praytellblog.com/index.php/2015/05/26/history-of-infant-communion-part-2-medieval-and-modern-periods-500-2015-ad/ |website=PrayTellBlog |date=26 May 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ** Briefly in the 490s ] made communion under both kinds mandatory.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Emmons |first1=D. D. |title=COMMUNION UNDER ONE KIND: Exploring the Church history and norms of receiving the body and blood of Christ at Mass |journal=Our Sunday Visitor |date=28 June 2020 |volume=109 |issue=10 |pages=14–15}}</ref> | |||

| * Prayer | |||

| | Communion cycle | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| ** ] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| ** Minimum: three times per year,<ref name=Izbicki/> then annually at Easter (from 1215)<ref>{{cite web |title=CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Frequent Communion |url=https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06278a.htm |website=www.newadvent.org}}</ref> | |||

| *Prayers | |||

| ** Leavened or unleavened bread, on tongue{{refn|goup=note|From 650, ].<ref name=Izbicki>{{cite book |last1=Izbicki |first1=Thomas M. |title=The Eucharist in Medieval Canon Law |date=14 October 2015 |doi=10.1017/CBO9781316408148.007}}</ref>}} | |||

| ** Wine and water, mostly<ref>{{cite web |last1=Viar |first1=Lucas |title=Eucharistic Utensils |url=https://www.liturgicalartsjournal.com/2020/04/eucharistic-utensils.html |website=Liturgical Arts Journal}}</ref> drunk with ] (or ''calamus''); later ] | |||

| * Prayers | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| | | |||

| * ] (Pater noster) | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (Agnus Dei) | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * Communion | |||

| ** Minimum: annually (Easter); typical: weekly; maximum: daily (+ one special Mass) | |||

| ** Unleavened wafers, in hand in regions where Bishops' conference approves, on tongue otherwise | |||

| ** Wine with water, from chalice, in dioceses where Bishop has permitted | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | Collection for the needy | |||

| | Dismissal of the faithful || ] or ] | | Dismissal of the faithful || ] or ] | ||

| | Concluding rites | |||

| * Announcements | |||

| * Final Blessing | |||

| * Dismissal | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| Source: Hoppin, Richard. ''Medieval Music''. New York: Norton, 1977. Page 119 and 122. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ===Western Catholic=== | |||

| ==References== | |||

| *] | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| **] | |||

| *** Post-Tridentine Mass | |||

| ****''Novus ordo'' - ] (c.1970) | |||

| ***** ] | |||

| ******Eucharastic Prayer I - ] | |||

| ****** Eucharistic Prayer II - from '']'' of Hypolytus <ref>Note 17, {{cite web |title=The Composition of the Second Eucharistic Prayer |url=https://www.arcaneknowledge.org/catholic/hippolytus.htm |website=www.arcaneknowledge.org}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=McGowan |first1=Anne |title=Eucharistic Epicleses, Ancient and Modern: Speaking Of The Spirit In Eucharistic Prayers |date=15 May 2014 |publisher=SPCK |isbn=978-0-281-07156-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kAn7AwAAQBAJ&dq=eucharistic+prayer+III+++ambrosian&pg=PT222 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ****** Eucharistic Prayer III - blend of I and II<ref>{{cite web |title=The Liturgy of the Eucharist: The Eucharistic Prayer (3) |url=https://rcspirituality.org/finding_the_plug/the-liturgy-of-the-eucharist-3/ |website=RC Spirituality}}</ref> | |||

| ****** Eucharistic Prayer IV - from ] esp. of ] | |||

| *****] | |||

| ****Ex-] | |||

| *****] | |||

| ******Eucharastic Prayer I - ] | |||

| ****** Eucharistic Prayer II | |||

| ***] | |||

| ****Missale Romanum of ] (1570) | |||

| *****Updates: 1604, 1634, 1884, 1920, 1955 | |||

| ****] (1962) | |||

| *****Updates: 1965, 1967 | |||

| ****] | |||

| ***Pre-Tridentine (Roman Rite) Mass | |||

| ****] (c.600) | |||

| ****]<ref>{{CathEncy|wstitle= Ordines Romani |volume= 11 |last= Thurston |first= Herbert |author-link= Herbert Thurston |short=1}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Romano |first1=John F. |title=The Fates of Liturgies: Towards a History of the First Roman Ordo |journal=Antiphon |date=2007 |volume=11 |issue=2 |pages=43–77 |url=https://www.academia.edu/31740034 |access-date=19 October 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ****Uses in Rome<ref name=novak/> | |||

| *****Liturgy of the Roman Curia | |||

| *****Liturgy of St Peter's Basilica | |||

| *****Liturgy of Lateran Basilica | |||

| *****Liturgy of ] | |||

| ****Uses of England<ref>{{cite web |last1=Dipippo |first1=Gregory |title=The Theology of the Offertory - Part 7.3 - Medieval English Uses |url=https://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2014/08/the-theology-of-offertory-part-73.html |website=New Liturgical Movement}}</ref> | |||

| *****] | |||

| ******Use of Norway (Nidaros)<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Karlsen |first1=Espen |last2=Hareide |first2=Sigurd |title=The Nidaros Missal (1519) |journal=Missale Nidrosiense, Edited by Ingrid Sperber |date=21 May 2019 |url=https://www.academia.edu/39212054}}</ref> | |||

| ******] | |||

| *****] | |||

| *****Use of Lincoln | |||

| ****] | |||

| ****Use of Prague<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kolář |first1=Pavel |title=Witnesses of a New Liturgical Practice: the Ordines missae of Three Utraquist Manuscripts 1 |journal=The Bohemian Reformation and Religious Practice 9| url=https://www.academia.edu/92167437}}</ref> | |||

| ****Use of Norman Sicily (French Use)<ref>{{cite web |title=CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: The Gallican Rite |url=https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06357a.htm |website=www.newadvent.org}}</ref> | |||

| ****] | |||

| *****] (1368)<ref name=novak>{{cite journal |last1=Kuhar |first1=Kristijan |last2=Košćak |first2=Silvio |last3=Renhart |first3=Erich |title=The content of the glagolitic missal of count Novak in the digital environment|journal=Crkva U Svijetu |date=31 December 2021 |volume=56 |issue=4 |pages=619–634 |doi=10.34075/cs.56.4.4|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| **] | |||

| ***] | |||

| **] | |||

| ***Romano-Cistercian Rite | |||

| **Romano-Gallican | |||

| ***] | |||

| ****] | |||

| ***] | |||

| ***] | |||

| ***] | |||

| ***Jerusalem Rite | |||

| ****] | |||

| ***] | |||

| ****] | |||

| ****Use of Bangor (Ireland)<ref name=maskell>{{cite book |last1=Maskell |first1=William |title=The Ancient Liturgy of the Church of England: According to the Uses of Sarum, Bangor, York, & Hereford, and the Modern Roman Liturgy |date=1846 |publisher=W. Pickering |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_74PAAAAIAAJ |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ***] | |||

| ***] | |||

| ***] (]) rite | |||

| ****] | |||

| ****] | |||

| **Hispano-Gallican | |||

| ***] | |||

| ****] | |||

| ***] | |||

| ****] | |||

| **] | |||

| == |

===Eastern Catholic=== | ||

| *] | |||

| ===Scholarly works=== | |||

| *] | |||

| *, study by the renowned liturgist, Father Adrian Fortescue | |||

| **Clementine Liturgy - ] | |||

| *, said to be based on Adrian Fortescue's ''The Mass: A Study of the Roman Liturgy'' | |||

| **] | |||

| * | |||

| ***] | |||

| *, by E.G. Atchley | |||

| ***] | |||

| * (the liturgical reforms of ] in about 600) | |||

| ***] | |||

| * (the liturgical reforms promoted by ] in about 800) | |||

| **] | |||

| ***] | |||

| *Hagiopolite rite (Holy Sepulchre) | |||

| **] | |||

| *] | |||

| **] | |||

| ***(Coptic) ] | |||

| **] | |||

| * Chaldean liturgical rites | |||

| **] | |||

| ***] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| * (A discussion of the ceremonies of the medieval Church of Lincoln) | |||

| {{reflist|group=note}} | |||

| * (Includes two variants of the Ordinary of the Sarum Mass and a Pre-Tridentine variant of the Curial Use of the Roman Mass) | |||

| * | |||

| ==References== | |||

| ===Roman Missal before 1570 and precedents=== | |||

| {{Reflist|32em}} | |||

| *{{Dead link|date=December 2010}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| === Sources === | |||

| ===Pre-1570 Missals used outside of Rome by local variants of Roman Rite=== | |||

| *{{cite book|year=1998|publisher=Libreria Editrice Vaticana|editor1-first=Manlio|editor1-last=Sodi|editor2-first = Achille Maria |editor2-last=Triacca|language= la|title=Missale Romanum|trans-title=Roman missal|edition=Princeps|isbn=88-209-2547-8}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| *{{dead link|date=February 2013}} | |||

| * | |||

| * Ordo Missae and Canon in Latin | |||

| * Ordo Missae and Canon in Latin. | |||

| * Ordo Missae and Canon in Latin | |||

| * Ordo Missae and Canon in Latin | |||

| * as used in ] during the episcopate of its first bishop, A.D. 1050-1072. Together with some account of the Red book of Derby, the Missal of ], and a few other early manuscript service books of the English church. Edited, with introd. and notes (1883) | |||

| * (The ] in Latin) | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * (An Irish Missal, which differs slightly from other uses of the Roman rite because St. Patrick and St. Gregory the Great are commemorated in the Canon of the Mass) | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| *Comments of Helge Fæhn on the characteristics of the medieval Use of Nidaros as found in the surviving missals of the ]. | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| ===Media on variants of Roman Rite outside of Rome=== | |||

| *{{Citation|url=https://archive.org/details/ordoromanusprimu00atchuoft|title=Ordo Romanus Primus|first=E. G.|last=Atchley|year=1905|author-link=E. G. Cuthbert F. Atchley|publisher=Archive}}. | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{CatholicMass}} | |||

| {{Seven Sacraments}} | {{Seven Sacraments}} | ||

| {{Latin Church footer}} | |||

| {{History of the Roman Rite Mass}} | |||

| {{CatholicMass|collapsed}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 22:18, 12 December 2024

Forms of the Mass before 1570 Not to be confused with Tridentine Mass or Novus Ordo.

Pre-Tridentine Mass refers to the evolving and regional forms of the Catholic Mass in the West from antiquity to 1570. The basic structure solidified early and has been preserved, as well as important prayers such as the Roman Canon.

Following the Council of Trent's desire for standardization, Pope Pius V, with his bull Quo primum, made the Roman Missal obligatory throughout the Latin Church, except for those places and congregations whose distinct rites could demonstrate an antiquity of two hundred years or more.

Development

Earliest accounts

See also: Origin of the Eucharist, Eucharist in the Catholic Church, and Agape feast 2nd-century description of the EucharistJustin Martyr (First Apology 66:1–20 )And this food is called among us Eukharistia , of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.

The earliest surviving account of the celebration of the Eucharist or the Mass in Rome is that of Saint Justin Martyr (died c. 165), in chapter 67 of his First Apology:

On the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons.

In chapter 65, Justin Martyr says that the kiss of peace was given before the bread and the wine mixed with water were brought to "the president of the brethren". The initial liturgical language used was Greek, before approximately the year 190 under Pope Victor, when the Church in Rome changed from Greek to Latin, except in particular for the Hebrew word "Amen", whose meaning Justin explains in Greek (γένοιτο), saying that by it "all the people present express their assent" when the president of the brethren "has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings".

According to some scholars, the early Christian liturgy was a continuation of the liturgy of contemporary Jewish synagogues (as distinct from the temple liturgy): Duschesne comments "the only permanent element, on the whole, which Christianity added to the liturgy of the synagogue wasthe sacred meal instituted by Jesus Christ as a perpetual commemoration of himself." This tradition included unaccompanied chant.

Early changes

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||

| Catholic Church | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City | ||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||

| Background | ||||||||||||||||

| Organisation | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

Texts

|

||||||||||||||||

Philosophy

|

||||||||||||||||

| Worship | ||||||||||||||||

|

Rites

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Miscellaneous

Relations with: |

||||||||||||||||

| Societal issues | ||||||||||||||||

| Links and resources | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

It is unclear when the language of the celebration finished changing from Greek to Latin. Pope Victor I (190–202), may have been the first to use Latin in the liturgy in Rome. Others think Latin was finally adopted nearly a century later. The change was probably gradual, with both languages being used for a while.

With regard to the Roman Canon of the Mass, the prayers beginning Te igitur, Memento Domine and Quam oblationem were already in use, even if not with quite the same wording as now, by the year 400; the Communicantes, the Hanc igitur, and the post-consecration Memento etiam and Nobis quoque were added in the fifth century.

Early Middle Ages

Before the pontificate of Pope Gregory I (590–604), the Roman Mass rite underwent many changes, including a "complete recasting of the Canon" (a term that in this context means the Anaphora or Eucharistic Prayer). At the time of Gregory I, regional customisation of liturgies were encouraged in missionary areas: according to Bede Gregory instructed Augustine of Canterbury to select "any customs in the Roman or the Gaulish Church or any other Church which may be more pleasing to Almighty God", and to teach them to the church of the English.

In Gaul, the Merovingian period in (approx. 500-750) has been called "the experimental age of liturgy," with the propers constructed freely: according to historian Yitzhak Hen "each bishop, abbot or priest was free to choose the prayers he found suitable." Cross-pollenation and recycling of liturgical prayers was common, as priests and bishops took sacramentaries (manuscripts of liturgical prayers) between regions, and new prayers were composed.

Numerous regional styles of chant thrived, including Old Roman chant, Gallican chant, Ambrosian chant (still in use) and Beneventan chant. Following Gregory I came substantial changes in what became known as Gregorian chant.

In the eighth century the Meringovian dynasty had been replaced by the Carolingians in Frankish Gaul. In the late eighth century, Pepin the Short ordered the Roman chant be used throughout his domains. However, some elements of the preceding Gallican rites were fused with it north of the Alps, and the resulting mixed rite was introduced into Rome under the influence of the emperors who succeeded Charlemagne. Gallican influence is responsible for the introduction into the Roman rite of dramatic and symbolic ceremonies such as the blessing of candles, ashes, palms, and much of the Holy Week ritual.

During the Carolingian period, the language diverged with Latin going back to its classical forms and the vernacular recognized as separate tongues. Consequently, the Council of Tours (813) mandated that sermons be given in the Romance or Teutonic vernacular.

The chants and musical settings of the Mass were divided into

- the parts that do not change during the year (the Ordinary: the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei), and

- the parts that belonged to the particular day and occasion (the Proper): Introit, Gradual, Alleluia, Offertory, Communion.

The major difference between the various rites or uses was not the basic structure or components of the ordinary parts of the liturgy, but of different arrangements, selection and allocation of prayers on different days, as well as mention of regionally-popular saints, and different rubrics.

Late Middle Ages

Towards the end of the first millennium, organ, previously a secular instrument, was introduced as did more complicated singing of components of the Mass by choirs. Important liturgies might be preceded, followed or interrupted by elaborate processions with songs, dramatic rituals involving props, and acted plays or tableau, with the laity trained to understand the symbolism. In several locations, the story of the Three Magi would be enacted by three costumed men who would follow a star through the church, search at various locations, until finding the altar, while singing the Gospel alternatively and polyphonically.

The recitation of the Credo (Nicene Creed) after the Gospel is attributed to the influence of Emperor Henry II. Gallican influence explains the practice of incensing persons, introduced in the eleventh or twelfth century; "before that time incense was burned only during processions (the entrance and Gospel procession)". Private prayers for the priest to say before Communion were another novelty. About the thirteenth century, an elaborate ritual and additional prayers of French origin were added to the Offertory: previously, the only prayer said by the priest was the Secret; these prayers varied considerably until fixed by Pope Pius V in 1570. The rites had some differences in the prayers on the boundaries of the Mass: Pre-Tridentine prayers said mostly in the sacristy or during the procession to the altar as part of the priest's preparation were formalized in the 1570 missal of Pope Pius V as the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar; prayers that followed the Ite missa est changed or changed position (for example, in the 1570 edition, the Canticle of the Three Young Men and Psalm 150 in Pius V's edition the priest was to say while leaving the altar were later omitted.)

Renaissance

Between 1478 and 1501, the bishops of 52 dioceses, including the primates of France, Castile, England, the Holy Roman Empire and Poland each independently published, in print, official liturgical texts for their diocese, because of the extent of parish and monastery variation. In some places, this involved stripping variations back to the Cathedral's missal; however in others it involved adding material for new saints, offices and customs.

From 1474 until Pope Pius V's 1570 text, there were at least 14 different printed editions that purported to present the text of the Mass as celebrated in Rome, rather than elsewhere, and which therefore were published under the title of "Roman Missal" (Latin: Missale romanum.) These were produced in Milan, Venice, Paris and Lyon. Even these show variations. Local Missals, such as the Parisian Missal, of which at least 16 printed editions appeared between 1481 and 1738, showed more important differences. The Milanese Roman Missal of 1474, which reproduces the Papal Chapel missal of the late 1200s, "hardly differs at all" from the initial Tridentine missal promulgated in 1570, apart from local feasts.

Other rites

Apart from the Roman rite, before 1570 many other liturgical rites were in use, not only in the East, but also in the West. Some Latin liturgical rites, such as the Mozarabic Rite, were unrelated to the Roman Rite which Pope Pius V revised and ordered to be adopted generally, and even areas that had accepted the Roman rite had introduced changes and additions. As a result, every ecclesiastical province and almost every diocese had its local use, such as the Use of Sarum, the Use of York and the Use of Hereford in England. In France, there were strong traces of the Gallican Rite. With the exception of the relatively few places where no form of the Roman Rite had ever been adopted, the Canon of the Mass remained generally uniform, but the prayers in the "Ordo Missae", and still more the "Proprium Sanctorum" and the "Proprium de Tempore", varied widely.

Languages

In most countries, the language used for celebrating Pre-Tridentine Masses was Latin, which had become the language of the Roman liturgy in the late 4th century. However, there have been exceptions:

- In Dalmatia and parts of Istria in Croatia, the Roman Rite liturgy was celebrated in Old Church Slavonic from the time of Cyril and Methodius, and authorization for use of this language was extended to some other Slavic regions between 1886 and 1935.

- In the 14th century, Dominican missionaries converted a monastery near Qrna, Armenia to Catholicism, and translated the liturgical books of the Dominican Rite, a variant of the Roman Rite, into Armenian for the community's use. The monks were deterred from becoming members of the Dominican Order itself by the severe fasting requirements of the Dominican Constitutions, as well as the prohibition on owning any land other than that on which the monastery stood, and therefore became the Order of the United Friars of St. Gregory the Illuminator, a new order confirmed by Pope Innocent VI in 1356 whose Constitutions were similar to the Dominicans' except for these two laws. This order established monasteries over a vast amount of territory in Greater and Lesser Armenia, Persia, and Georgia, using the Dominican Rite in Armenian until the end of the order's existence in 1794.

- On February 25, 1398, Pope Boniface IX also authorized Maximus Chrysoberges to found a monastery in Greece where Mass would be celebrated in Greek according to the Dominican Rite, and Manuel Chrysoloras translated the Dominican missal into Greek in pursuance of the plan, but nothing further is known of this undertaking.

At various times there were calls for the prayers of the Mass to be in the vernacular, such as by Erasmus.

Legacy