| Revision as of 00:51, 24 May 2014 edit69.123.195.235 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:13, 15 November 2024 edit undoBon courage (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users66,214 editsm →References: fmt | ||

| (963 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Study and use of supposed medicinal properties of plants}} | |||

| '''Herbalism ''' ('''"Herbology"''' or '''"Herbal Medicine"''') is use of plants for medicinal purposes, and the study of such use. Plants have been the basis for medical treatments through much of human history, and such ] is still widely practiced today. Modern medicine recognizes herbalism as a form of ], as the practice of herbalism is not strictly based on ] gathered using the ]. Modern medicine, does, however, make use of many plant-derived compounds as the basis for evidence-tested ]s, and ] works to apply modern standards of effectiveness testing to herbs and medicines that are derived from natural sources. The scope of herbal medicine is sometimes extended to include ] and ] products, as well as ], ] and certain animal parts. | |||

| {{redirect|Phytomedicine|the journal|Phytomedicine (journal)}} | |||

| {{Alternative medicine sidebar|fringe}} | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Herbal medicine''' (also called '''herbalism''', '''phytomedicine''' or '''phytotherapy''') is the study of ] and the use of ], which are a basis of ].<ref name=swallow>{{cite journal | vauthors = | title = Hard to swallow | journal = Nature | volume = 448 | issue = 7150 | pages = 105–6 | date = July 2007 | pmid = 17625521 | doi = 10.1038/448106a | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2007Natur.448S.105. }}</ref> With worldwide research into ], some herbal medicines have been translated into modern remedies, such as the anti-malarial group of drugs called ] isolated from '']'', a herb that was known in ] to treat fever.<ref>{{cite magazine |title=This Ancient Chinese Remedy Helped Win the Nobel Prize |url=https://time.com/4061207/nobel-prize-medicine-ancient-chinese-remedy/ |access-date=2021-10-11 |magazine=Time |language=en |archive-date=3 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221103003455/https://time.com/4061207/nobel-prize-medicine-ancient-chinese-remedy/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Su |first1=Xin-zhuan |last2=Miller |first2 = Louis H. |date=November 2015 |title = The discovery of artemisinin and Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine |journal = Science China Life Sciences |volume=58 |issue=11 |pages=1175–1179 |doi=10.1007/s11427-015-4948-7 |issn=1674-7305 |pmc=4966551 |pmid=26481135 }}</ref> There is limited ] for the safety and efficacy of many plants used in 21st-century herbalism, which generally does not provide standards for purity or dosage.<ref name=swallow/><ref name=Lack2016>{{cite book | vauthors = Lack CW, Rousseau J |title=Critical Thinking, Science, and Pseudoscience: Why We Can't Trust Our Brains |date=2016 |publisher=Springer Publishing Company |isbn=9780826194268 |pages=212–214 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Miy2CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA212 |language=en}}</ref> The scope of herbal medicine sometimes includes ] and ] products, as well as ], ] and certain animal parts.<ref name="cruk-herbs"/> | |||

| '''Paraherbalism''' describes ] and ] practices of using unrefined plant or animal ]s as unproven medicines or health-promoting agents.<ref name=swallow/><ref name=Lack2016/><ref name="tyler">{{Cite web|url=http://www.quackwatch.org/01QuackeryRelatedTopics/paraherbalism.html|title=False Tenets of Paraherbalism|publisher=Quackwatch|vauthors=Tyler VE|date=31 August 1999|access-date=29 October 2016|archive-date=11 November 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091111182115/http://www.quackwatch.org/01QuackeryRelatedTopics/paraherbalism.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=quackwatch/> Paraherbalism relies on the belief that preserving various substances from a given source with less processing is safer or more effective than manufactured products, a concept for which there is no evidence.<ref name=tyler/> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{main|History of herbalism}} | {{main|History of herbalism|Materia medica}} | ||

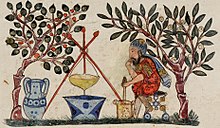

| ] version of ]'s pharmacopoeia, 1224]] | |||

| Archaeological evidence indicates that the use of medicinal plants dates at least to the ], approximately 60,000 years ago. Written evidence of herbal remedies dates back over 500,000 years, to the Sumerians, who created lists of plants. A number of ancient cultures wrote on plants and their medical uses. In ancient Egypt, herbs are mentioned in ], depicted in tomb illustrations, or on rare occasions found in medical jars containing trace amounts of herbs.<ref name="aem">{{cite book|last=Nunn|first=John|title=Ancient Egyptian Medicine|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=WHfEnVU6z8IC&pg=PA151|year=2002|publisher=University of Oklahoma Press|isbn=978-0-8061-3504-5|page=151}}</ref> The earliest known ] herbals were those of ], written during the 3rd century B.C, and one by Krateuas from the 1st century B.C. | |||

| Archaeological evidence indicates that the use of ]s dates back to the ] age, approximately 60,000 years ago. Written evidence of herbal remedies dates back over 5,000 years to the ]ians, who compiled lists of plants. Some ancient cultures wrote about plants and their medical uses in books called '']s''. In ancient Egypt, herbs were mentioned in ], depicted in tomb illustrations, or on rare occasions found in medical jars containing trace amounts of herbs.<ref name="aem">{{cite book | vauthors = Nunn J |title= Ancient Egyptian Medicine|journal= Transactions of the Medical Society of London|url =https://books.google.com/books?id=WHfEnVU6z8IC&pg=PA151|year= 2002|volume= 113|pages= 57–68|publisher= University of Oklahoma Press|isbn= 978-0-8061-3504-5|pmid= 10326089}}</ref> In ancient Egypt, the ] dates from about 1550 BCE, and covers more than 700 compounds, mainly of plant origin.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Atanasov AG, Waltenberger B, Pferschy-Wenzig EM, Linder T, Wawrosch C, Uhrin P, Temml V, Wang L, Schwaiger S, Heiss EH, Rollinger JM, Schuster D, Breuss JM, Bochkov V, Mihovilovic MD, Kopp B, Bauer R, Dirsch VM, Stuppner H | display-authors = 6 | title = Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review | journal = Biotechnology Advances | volume = 33 | issue = 8 | pages = 1582–1614 | date = December 2015 | pmid = 26281720 | pmc = 4748402 | doi = 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001 }}</ref> The earliest known ] herbals came from ] of Eresos who, in the 4th century BCE, wrote in ] '']'', from ] who wrote during the 3rd century BCE, and from Krateuas who wrote in the 1st century BCE. Only a few fragments of these works have survived intact, but from what remains, scholars have noted overlap with the Egyptian herbals.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Robson B, Baek OK |title= The Engines of Hippocrates: From the Dawn of Medicine to Medical and Pharmaceutical Informatics|publisher= John Wiley & Sons|year= 2009|isbn= 9780470289532|page= 50|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=DVA0QouwC4YC&pg=PA50}}</ref> Seeds likely used for herbalism were found in archaeological sites of ] China dating from the ]<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Hong F |title=History of Medicine in China |journal=McGill Journal of Medicine |year=2004 |volume=8 |issue=1 |page=7984 |url=http://www.medicine.mcgill.ca/MJM/issues/v08n01/crossroads/hong.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131201231218/http://www.medicine.mcgill.ca/MJM/issues/v08n01/crossroads/hong.pdf |archive-date=1 December 2013 }}</ref> ({{Circa|1600|1046 BCE}}). Over a hundred of the 224 compounds mentioned in the '']'', an early Chinese medical text, are herbs.<ref name="Unsc">{{cite book| vauthors = Unschuld P |title= Huang Di Nei Jing: Nature, Knowledge, Imagery in an Ancient Chinese Medical Text |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N2ZdrPCbpNIC&pg=PR9 |year=2003 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-92849-7|page= 286}}</ref> Herbs were also commonly used in the ] of ancient India, where the principal treatment for diseases was diet.<ref name="Acker">{{cite book | vauthors = Ackerknecht E |title=A Short History of Medicine|url=https://archive.org/details/shorthistoryofme00acke |url-access= registration|year=1982 |publisher=JHU Press |isbn= 978-0-8018-2726-6|page= }}</ref> '']'', originally written in Greek by ] ({{Circa|40|90 CE|lk=no}}) of ], ], a physician and botanist, is one example of herbal writing used over centuries until the 1600s.<ref name="ct">{{cite book | title = The Classical Tradition | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=LbqF8z2bq3sC&pg=PA146 | year = 2010 | publisher = Harvard University Press | isbn = 978-0-674-03572-0 | page = 146 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Modern herbal medicine== | ==Modern herbal medicine== | ||

| The ] (WHO) estimates that |

The ] (WHO) estimates that 80 percent of the population of some Asian and African countries presently uses herbal medicine for some aspect of primary health care.<ref name=who>{{cite web|url=https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs134/en/ |title=Traditional medicine |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080727053337/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs134/en/ |archive-date=27 July 2008 }}</ref> | ||

| Some ]s have a basis as herbal remedies, including ],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Su XZ, Miller LH | title = The discovery of artemisinin and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine | journal = Science China Life Sciences | volume = 58 | issue = 11 | pages = 1175–9 | date = November 2015 | pmid = 26481135 | pmc = 4966551 | doi = 10.1007/s11427-015-4948-7 }}</ref> ], ] and ]s. | |||

| Many of the ] currently available to physicians have a long history of use as herbal remedies, including ], ], ], and ]. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 25% of modern drugs used in the United States have been derived from plants.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs134/en/ |title=Traditional medicine. }}</ref> At least 7,000 medical compounds in the modern pharmacopoeia are derived from plants<ref>{{cite web | author = Interactive European Network for Industrial Crops and their Applications | title = Summary Report for the European Union | date = 2000–2005 | url = http://ec.europa.eu/research/quality-of-life/ka5/en/00111.html | id = QLK5-CT-2000-00111 | accessdate = }} .</ref> Among the 120 active compounds currently isolated from the higher plants and widely used in modern medicine today, 80 percent show a positive correlation between their modern therapeutic use and the traditional use of the plants from which they are derived.<ref name=Fabricant2001>{{cite journal |author=Fabricant DS, Farnsworth NR |title=The value of plants used in traditional medicine for drug discovery |journal=Environ. Health Perspect. |volume=109 Suppl 1 |issue= Suppl 1|pages=69–75 |date=March 2001 |pmid=11250806 |pmc=1240543 |doi= |url=}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Regulatory review=== | ||

| ] tree contains ], which today is a widely prescribed treatment for ], especially in countries that cannot afford to purchase the more expensive anti-malarial drugs produced by the ].]] | |||

| In 2015, the ] published the results of a review of alternative therapies that sought to determine if any were suitable for being covered by ]; herbalism was one of 17 topics evaluated for which no clear evidence of effectiveness was found.<ref name="aus17">{{cite web |year=2015 |title=Review of the Australian Government Rebate on Natural Therapies for Private Health Insurance |url=http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/0E9129B3574FCA53CA257BF0001ACD11/$File/Natural%20Therapies%20Overview%20Report%20Final%20with%20copyright%2011%20March.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160626024750/http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/0E9129B3574FCA53CA257BF0001ACD11/$File/Natural%20Therapies%20Overview%20Report%20Final%20with%20copyright%2011%20March.pdf |archive-date=26 June 2016 |access-date=12 December 2015 |publisher=Australian Government – Department of Health |vauthors=Baggoley C}}</ref> Establishing guidelines to assess the safety and efficacy of herbal products, the ] provided criteria in 2017 for evaluating and grading the quality of clinical research in preparing monographs about herbal products.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000830.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580033a9b|title=Assessment of clinical safety and efficacy in the preparation of Community herbal monographs for well-established and of Community herbal monographs/entries to the Community list for traditional herbal medicinal products/substances/preparations|publisher=European Medicines Agency|date=2017|access-date=25 February 2017|archive-date=26 February 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170226050218/http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000830.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580033a9b|url-status=live}}</ref> In the United States, the ] of the ] funds clinical trials on herbal compounds, provides fact sheets evaluating the safety, potential effectiveness and side effects of many plant sources,<ref name="nccih">{{cite web|url=https://nccih.nih.gov/health/herbsataglance.htm|title=Herbs at a Glance|publisher=National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US National Institutes of Health|date=21 November 2016|access-date=24 February 2017|archive-date=30 March 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190330204542/https://nccih.nih.gov/health/herbsataglance.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> and maintains a registry of clinical research conducted on herbal products.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://clinicaltrials.gov/search/open/term=herbal+medicine|title=Clinicaltrials.gov, a registry of studies on herbal medicine|publisher=Clinicaltrials.gov, US National Institutes of Health|date=2017|access-date=25 February 2017|archive-date=1 April 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190401125849/https://clinicaltrials.gov/search/open/term=herbal+medicine|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In a 2014 survey of the most common 1000 plant-derived compounds, only 156 had clinical trials published. Preclinical studies (tissue-culture and animal studies) were reported for about one-half of the plant products, while 12% of the plants, although available in the Western market, had "no substantial studies" of their properties. Strong evidence was found that 5 were toxic or allergenic, so that their use ought to be discouraged or forbidden. Nine plants had considerable evidence of therapeutic effect.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cravotto G, Boffa L, Genzini L, Garella D |title=Phytotherapeutics: an evaluation of the potential of 1000 plants |journal=J Clin Pharm Ther |volume=35 |issue=1 |pages=11–48 |date=February 2010 |pmid=20175810 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01096.x |url=}}</ref> | |||

| According to Cancer Research UK, "there is currently no strong evidence from studies in people that herbal remedies can treat, prevent or cure cancer".<ref name="cruk-herbs">{{cite web | According to ] as of 2015, "there is currently no strong evidence from studies in people that herbal remedies can treat, prevent or cure cancer".<ref name="cruk-herbs">{{cite web |publisher=] |url=https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-in-general/treatment/complementary-alternative-therapies/individual-therapies/herbal-medicine |title=Herbal medicine |date=2 February 2015 |access-date=12 November 2018 |archive-date=29 May 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190529165631/https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-in-general/treatment/complementary-alternative-therapies/individual-therapies/herbal-medicine |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |url=http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-help/about-cancer/treatment/complementary-alternative/therapies/herbal-medicine | |||

| |title=Herbal medicine | |||

| |accessdate=August 2013}}</ref> | |||

| The U.S. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine of the National Institutes of Health funds clinical trials of the effectiveness of herbal medicines and provides “fact sheets” summarizing the effectiveness and side effects of many plant-derived preparations.<ref>http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?recr=Closed&no_unk=Y&spons=NCCAM</ref> | |||

| ===Prevalence of use=== | ===Prevalence of use=== | ||

| The use of herbal remedies is more prevalent in people with ], such as cancer, ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Burstein HJ, Gelber S, Guadagnoli E, Weeks JC | title = Use of alternative medicine by women with early-stage breast cancer | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 340 | issue = 22 | pages = 1733–9 | date = June 1999 | pmid = 10352166 | doi = 10.1056/NEJM199906033402206 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Egede LE, Ye X, Zheng D, Silverstein MD | title = The prevalence and pattern of complementary and alternative medicine use in individuals with diabetes | journal = Diabetes Care | volume = 25 | issue = 2 | pages = 324–9 | date = February 2002 | pmid = 11815504 | doi = 10.2337/diacare.25.2.324 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Roozbeh J, Hashempur MH, Heydari M | title = Use of herbal remedies among patients undergoing hemodialysis | journal = Iranian Journal of Kidney Diseases | volume = 7 | issue = 6 | pages = 492–5 | date = November 2013 | pmid = 24241097 }}</ref> Multiple factors such as gender, age, ethnicity, education and social class are also shown to have associations with the prevalence of herbal remedy use.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bishop FL, Lewith GT | title = Who Uses CAM? A Narrative Review of Demographic Characteristics and Health Factors Associated with CAM Use | journal = Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine | volume = 7 | issue = 1 | pages = 11–28 | date = March 2010 | pmid = 18955327 | pmc = 2816378 | doi = 10.1093/ecam/nen023 }}</ref> | |||

| A survey released in May 2004 by the ] focused on who used ] (CAM), what was used, and why it was used. The survey was limited to adults, aged 18 years and over during 2002, living in the ]. According to this survey, herbal therapy, or use of natural products other than ]s and minerals, was the most commonly used CAM therapy (18.9%) when all use of ] was excluded.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://nccam.nih.gov/news/report.pdf |title=Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults: United States, 2002 |accessdate= September 16, 2006 |author= |last= Barnes |first= P M |authorlink= |author2=Powell-Griner E |author3=McFann K |author4=Nahin R L |date= 2004-05-27 |format= PDF |work= Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 343 |publisher= National Center for Health Statistics. 2004 |pages= 20 |language= |archiveurl= |archivedate=}} (See table 1 on page 8).</ref><ref> Press release, May 27, 2004. ]</ref> | |||

| ===Herbal preparations=== | |||

| Herbal remedies are very common in ]. In ], herbal medications are dispensed by apothecaries (e.g., Apotheke). Prescription drugs are sold alongside essential oils, herbal extracts, or ]s. Herbal remedies are seen by some as a treatment to be preferred to pure medical compounds which have been industrially produced.<ref>{{cite journal| author = James A. Duke |date=Dec–January 2000|title = Returning to our Medicinal Roots|journal = Mother Earth News|pages = 26–33|url =http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-73088521.html}}</ref> | |||

| ]'' being packed into a steam ] unit to gather its ]]] | |||

| There are many forms in which herbs can be administered, the most common of which is a liquid consumed as a herbal tea or a (possibly diluted) plant extract.<ref name="saad-2011-p80" /> | |||

| ]s, or tisanes, are the resultant liquid of extracting herbs into water, though they are made in a few different ways. ]s are hot water extracts of herbs, such as ] or ], through ]. ]s are the long-term boiled extracts, usually of harder substances like roots or bark. ] is the cold infusion of plants with high ]-content, such as ] or ]. To make macerates, plants are chopped and added to cold water. They are then left to stand for 7 to 12 hours (depending on the herb used). For most macerates, 10 hours is used.<ref name=autogenerated1 /> | |||

| In India, the herbal remedy is so popular that the Government of India has created a separate department - AYUSH - under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. The National Medicinal Plants Board was also established in 2000 by the Govt. of India in order to deal with the herbal medical system.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Kala|first=Chandra Prakash|author2=Sajwan|title=Revitalizing Indian systems of herbal medicine by the National Medicinal Plants Board through institutional networking and capacity building|journal=Current Science|year=2007|volume=93|issue=6|pages=797–806}}</ref> | |||

| ]s are alcoholic extracts of herbs, which are generally stronger than herbal teas.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Green J |title=The Herbal Medicine Maker's Handbook: A Home Manual|publisher=Chelsea Green Publishing|year=2000|isbn=9780895949905|page=168|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5nxKJ7SocEUC&pg=PT168}}</ref> Tinctures are usually obtained by combining <!--close to 100%-->pure ethanol (or a mixture of <!--100%(?)-->pure ethanol with water) with the herb. A completed tincture has an ethanol percentage of at least 25% (sometimes up to 90%).<ref name=autogenerated1>Groot Handboek Geneeskrachtige Planten by Geert Verhelst</ref> Non-alcoholic tinctures can be made with glycerin but it is believed to be less absorbed by the body than alcohol based tinctures and has a shorter shelf life.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Romm A |title=Botanical Medicine for Women's Health |year=2010 |publisher=Churchill Livingstone |isbn=978-0-443-07277-2 |pages=24}}</ref> Herbal wine and ]s are alcoholic extracts of herbs, usually with an ethanol percentage of 12–38%.<ref name=autogenerated1 /> ]s include liquid extracts, dry extracts, and nebulisates. Liquid extracts are liquids with a lower ethanol percentage than tinctures. They are usually made by vacuum ] tinctures. Dry extracts are extracts of plant material that are ] into a dry mass. They can then be further refined to a capsule or tablet.<ref name=autogenerated1 /> | |||

| Avid public interest in herbalism in the UK has been recently confirmed by the popularity of the topic in mainstream media, such as the prime-time hit TV series BBC's ], which demonstrated how to grow and prepare herbal remedies at home. | |||

| The exact composition of a herbal product is influenced by the method of extraction. A tea will be rich in ] components because water is a ]. Oil on the other hand is a ] solvent and it will absorb non-polar compounds. Alcohol lies somewhere in between.<ref name="saad-2011-p80">{{cite book| vauthors = Saad B, Said O |title=Greco-Arab and Islamic Herbal Medicine: Traditional System, Ethics, Safety, Efficacy, and Regulatory Issues|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|year=2011|isbn=9780470474211|page=80|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-WQVF8nhKf4C&pg=PT80}}</ref> | |||

| ===Herbal preparations=== | |||

| There are many forms in which herbs can be administered, the most common of which is in the form of a liquid that is drunk by the patient—either an herbal tea or a (possibly diluted) plant extract.<ref name="saad-2011-p80" /> Whole herb consumption is also practiced either fresh, in dried form or as fresh ].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} | |||

| ] of ]]] | |||

| Several methods of standardization may be determining the amount of herbs used. One is the ratio of raw materials to solvent. However different specimens of even the same plant species may vary in chemical content. For this reason, ] is sometimes used by growers to assess the content of their products before use. Another method is standardization on a signal chemical.<ref>{{cite journal | authorlink = Mark Blumenthal and Tara Hall | title = What is Herb Standardization? | journal = HerbalGram. | issue = 52 | pages = 25 | year = 2001 | |||

| Many herbs are applied topically to the skin in a variety of forms. ] extracts can be applied to the skin, usually diluted in a carrier oil. Many essential oils can burn the skin or are simply too high dose used straight; diluting them in olive oil or another food grade oil such as almond oil can allow these to be used safely as a topical. ]s, oils, ]s, creams, and lotions are other forms of topical delivery mechanisms. Most topical applications are oil extractions of herbs. Taking a food grade oil and soaking herbs in it for anywhere from weeks to months allows certain ] to be extracted into the oil. This oil can then be made into salves, creams, lotions, or simply used as an oil for topical application. Many massage oils, antibacterial salves, and wound healing compounds are made this way.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Northern Lore: A Field Guide to the Northern Mind-Body-Spirit| vauthors = Odinsson E |year=2010| publisher = Eoghan Odinsson |isbn=978-1452851433}}</ref> | |||

| | url = http://content.herbalgram.org/iherb/herbalgram/articleview.asp?a=2230}}</ref> | |||

| ], as in ], can be used as a treatment.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/treatment/aromatherapy |title=Aromatherapy |date=2017 |publisher=University of Maryland Medical Center |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20171025095003/http://www.umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/treatment/aromatherapy |archive-date=25 October 2017 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Herz RS | title = Aromatherapy facts and fictions: a scientific analysis of olfactory effects on mood, physiology and behavior | journal = The International Journal of Neuroscience | volume = 119 | issue = 2 | pages = 263–90 | year = 2009 | pmid = 19125379 | doi = 10.1080/00207450802333953 | name-list-style = vanc | s2cid = 205422999 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gilani AH, Shah AJ, Zubair A, Khalid S, Kiani J, Ahmed A, Rasheed M, Ahmad VU | display-authors = 6 | title = Chemical composition and mechanisms underlying the spasmolytic and bronchodilatory properties of the essential oil of Nepeta cataria L | journal = Journal of Ethnopharmacology | volume = 121 | issue = 3 | pages = 405–11 | date = January 2009 | pmid = 19041706 | doi = 10.1016/j.jep.2008.11.004 | name-list-style = vanc }}</ref> | |||

| ]'' being packed into a steam ] unit to gather its ].]] | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ]s, or tisanes, are the resultant liquid of extracting herbs into water, though they are made in a few different ways. ]s are hot water extracts of herbs, such as ] or ], through ]. ]s are the long-term boiled extracts, usually of harder substances like roots or bark. ] is the old infusion of plants with high ]-content, such as ], ], etc. To make macerates, plants are chopped and added to cold water. They are then left to stand for 7 to 12 hours (depending on herb used). For most macerates 10 hours is used.<ref name=autogenerated1 /> | |||

| ===Safety=== | |||

| ]s are alcoholic extracts of herbs, which are generally stronger than herbal teas.<ref>{{cite book|author=Green, James|title=The Herbal Medicine Maker's Handbook: A Home Manual|publisher=Chelsea Green Publishing|year=2000|isbn=9780895949905|page=168|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=5nxKJ7SocEUC&pg=PT168}}</ref> Usually obtained by combining 100% pure ethanol (or a mixture of 100% ethanol with water) with the herb. A completed tincture has an ethanol percentage of at least 25% (sometimes up to 90%).<ref name=autogenerated1>Groot Handboek Geneeskrachtige Planten by Geert Verhelst</ref> Herbal wine and ]s are alcoholic extract of herbs; usually with an ethanol percentage of 12-38% <ref name=autogenerated1 /> Herbal wine is a maceration of herbs in wine, while an elixir is a maceration of herbs in spirits (e.g., ], ], etc.){{citation needed|date=July 2012}} ]s include liquid extracts, dry extracts and nebulisates. Liquid extracts are liquids with a lower ethanol percentage than tinctures. They can (and are usually) made by vacuum ] tinctures. Dry extracts are extracts of plant material which are ] into a dry mass. They can then be further refined to a capsule or tablet.<ref name=autogenerated1 /> A nebulisate is a dry extract created by freeze-drying.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} ]s are prepared in the same way as tinctures, except using a solution of ] as the ].{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} ]s are extracts of herbs made with syrup or ]. Sixty-five parts of sugar are mixed with 35 parts of water and herb. The whole is then boiled and macerated for three weeks.<ref name=autogenerated1 /> | |||

| {{For|partial list of herbs with known adverse effects|List of herbs with known adverse effects}} | |||

| ]'' has been used in Ayurveda for various treatments, but contains ]s, such as ] and ], which may cause severe toxicity.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gaire BP, Subedi L | title = A review on the pharmacological and toxicological aspects of Datura stramonium L | journal = Journal of Integrative Medicine | volume = 11 | issue = 2 | pages = 73–9 | date = March 2013 | pmid = 23506688 | doi = 10.3736/jintegrmed2013016 }}</ref>]] | |||

| The exact composition of an herbal product is influenced by the method of extraction. A tea will be rich in ] components because ] is a ]. Oil on the other hand is a ] solvent and it will absorb non-polar compounds. Alcohol lies somewhere in between.<ref name="saad-2011-p80">{{cite book|authors=Saad, Bashar & Said, Omar|title=Greco-Arab and Islamic Herbal Medicine: Traditional System, Ethics, Safety, Efficacy, and Regulatory Issues|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|year=2011|isbn=9780470474211|page=80|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=-WQVF8nhKf4C&pg=PT80}}</ref> | |||

| It is a popular misconception that herbal medicines are safe and side-effect free.<ref>{{cite book |vauthors=Kumar P, Nandave M, Kumar A, Nandave D |year=2024 |chapter= Herbovigilance|veditors=Nandave M, Kumar A |title=Pharmacovigilance Essentials |publisher=Springer | doi=10.1007/978-981-99-8949-2_12 |pages=243–267|isbn=978-981-99-8948-5 }}</ref> Consumption of herbs may cause ]s.<ref name="Talalay">{{cite journal | vauthors = Talalay P, Talalay P | title = The importance of using scientific principles in the development of medicinal agents from plants | journal = Academic Medicine | volume = 76 | issue = 3 | pages = 238–47 | date = March 2001 | pmid = 11242573 | doi = 10.1097/00001888-200103000-00010 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Furthermore, "adulteration, inappropriate formulation, or lack of understanding of plant and drug interactions have led to adverse reactions that are sometimes life threatening or lethal."<ref name="LewisME">{{cite journal | vauthors = Elvin-Lewis M | title = Should we be concerned about herbal remedies | journal = Journal of Ethnopharmacology | volume = 75 | issue = 2–3 | pages = 141–64 | date = May 2001 | pmid = 11297844 | doi = 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00394-9 | name-list-style = vanc }}</ref> Proper double-blind clinical trials are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of each plant before medical use.<ref name="pmid17761132">{{cite journal | vauthors = Vickers AJ | title = Which botanicals or other unconventional anticancer agents should we take to clinical trial? | journal = Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology | volume = 5 | issue = 3 | pages = 125–9 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17761132 | pmc = 2590766 | doi = <!-- none --> }}</ref> | |||

| ] of ]]] | |||

| Many herbs are applied topically to the skin in a variety of forms. ] extracts can be applied to the skin, usually diluted in a carrier oil (many essential oils can burn the skin or are simply too high dose used straight – diluting in olive oil or another food grade oil such as almond oil can allow these to be used safely as a topical).<ref>{{cite web | title = Essential Oil Safety Information | url = http://aromaweb.com/articles/safety.asp}}{{verify credibility|date=July 2012}}</ref>{{verify credibility|date=July 2012}} Salves, oils, ]s, creams and lotions are other forms of topical delivery mechanisms. Most topical applications are oil extractions of herbs. Taking a food grade oil and soaking herbs in it for anywhere from weeks to months allows certain phytochemicals to be extracted into the oil. This oil can then be made into salves, creams, lotions, or simply used as an oil for topical application. Many massage oils, antibacterial salves and wound healing compounds are made this way. One can also make a ] or compress using whole herb (or the appropriate part of the plant) usually crushed or dried and re-hydrated with a small amount of water and then applied directly in a bandage, cloth or just as is.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} | |||

| Although many consumers believe that herbal medicines are safe because they are natural, herbal medicines and synthetic drugs may interact, causing toxicity to the consumer. Herbal remedies can also be dangerously contaminated, and herbal medicines without established efficacy, may unknowingly be used to replace prescription medicines.<ref name="pmid17913230">{{cite book| vauthors = Ernst E |chapter=Herbal Medicines: Balancing Benefits and Risks |title=Dietary Supplements and Health|volume=282|pages=154–67; discussion 167–72, 212–18 |year=2007|pmid=17913230|doi=10.1002/9780470319444.ch11|series=Novartis Foundation Symposia|isbn=978-0-470-31944-4}}</ref> | |||

| ] as in ] can be used as a mood changing treatment<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/aromatherapy-000347.htm |title=Aromatherapy |accessdate= |work= }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1080/00207450802333953 | last1 = Herz | first1 = RS. | author-separator =, | author-name-separator= | year = 2009 | title = Aroma therapy facts and fiction: a scientific analysis | url = | journal = Int J Neurosci | volume = 119 | issue = 2| pages = 263–290 | pmid = 19125379 }}</ref> to fight a sinus infection or cough <ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1016/j.jep.2008.11.004 | last1 = Gilani | first1 = AH | last2 = Shah | first2 = AJ | last3 = Zubair | first3 = A. | author-separator =, | author-name-separator= | last4 = Khalid | first4 = S| year = 2009 | last5 = Kiani | first5 = J | last6 = Ahmed | first6 = A | last7 = Rasheed | first7 = M | last8 = Ahmad | first8 = V | title = Chemical composition and mechanisms underlying the spasmolytic and bronchodilatory properties of the essential oil of Nepeta cataria L | url = | journal = J of Ethnopharmacol | volume = 121 | issue = 3| pages = 405–411 }}</ref>{{Citation needed|date=December 2007}}, or to cleanse the skin on a deeper level (steam rather than direct inhalation here){{Citation needed|date=December 2007}} | |||

| Standardization of purity and dosage is not mandated in the United States, but even products made to the same specification may differ as a result of biochemical variations within a species of plant.<ref name="bmc2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Newmaster SG, Grguric M, Shanmughanandhan D, Ramalingam S, Ragupathy S | title = DNA barcoding detects contamination and substitution in North American herbal products | journal = BMC Medicine | volume = 11 | pages = 222 | date = October 2013 | pmid = 24120035 | pmc = 3851815 | doi = 10.1186/1741-7015-11-222 | doi-access = free }}{{Retracted|doi=10.1186/s12916-024-03504-x|pmid=38965520|https://retractionwatch.com/?s=Steven+Newmaster ''Retraction Watch''}}</ref> Plants have chemical defense mechanisms against predators that can have adverse or lethal effects on humans. Examples of highly toxic herbs include poison hemlock and nightshade.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Müller JL | title = Love potions and the ointment of witches: historical aspects of the nightshade alkaloids | journal = Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology | volume = 36 | issue = 6 | pages = 617–27 | year = 1998 | pmid = 9776969 | doi = 10.3109/15563659809028060 }}</ref> They are not marketed to the public as herbs, because the risks are well known, partly due to a long and colorful history in Europe, associated with "sorcery", "magic" and intrigue.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lee MR | title = Solanaceae III: henbane, hags and Hawley Harvey Crippen | journal = The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh | volume = 36 | issue = 4 | pages = 366–73 | date = December 2006 | pmid = 17526134 }}</ref> Although not frequent, adverse reactions have been reported for herbs in widespread use.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Pinn G | title = Adverse effects associated with herbal medicine | journal = Australian Family Physician | volume = 30 | issue = 11 | pages = 1070–5 | date = November 2001 | pmid = 11759460 }}</ref> On occasion serious untoward outcomes have been linked to herb consumption. A case of major potassium depletion has been attributed to chronic licorice ingestion,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lin SH, Yang SS, Chau T, Halperin ML | title = An unusual cause of hypokalemic paralysis: chronic licorice ingestion | journal = The American Journal of the Medical Sciences | volume = 325 | issue = 3 | pages = 153–6 | date = March 2003 | pmid = 12640291 | doi = 10.1097/00000441-200303000-00008 | s2cid = 35033559 }}</ref> and consequently professional herbalists avoid the use of licorice where they recognize that this may be a risk. Black cohosh has been implicated in a case of liver failure.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lynch CR, Folkers ME, Hutson WR | title = Fulminant hepatic failure associated with the use of black cohosh: a case report | journal = Liver Transplantation | volume = 12 | issue = 6 | pages = 989–92 | date = June 2006 | pmid = 16721764 | doi = 10.1002/lt.20778 | s2cid = 28255622 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| Few studies are available on the safety of herbs for pregnant women,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Born D, Barron ML | title = Herb use in pregnancy: what nurses should know | journal = MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing | volume = 30 | issue = 3 | pages = 201–6; quiz 207–8 | date = May–June 2005 | pmid = 15867682 | doi = 10.1097/00005721-200505000-00009 | s2cid = 35882289 }}</ref> and one study found that use of complementary and alternative medicines is associated with a 30% lower ongoing pregnancy and live birth rate during fertility treatment.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Boivin J, Schmidt L | title = Use of complementary and alternative medicines associated with a 30% lower ongoing pregnancy/live birth rate during 12 months of fertility treatment | journal = Human Reproduction | volume = 24 | issue = 7 | pages = 1626–31 | date = July 2009 | pmid = 19359338 | doi = 10.1093/humrep/dep077 | name-list-style = vanc | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| Examples of herbal treatments with likely cause-effect relationships with adverse events include ] (which is often a legally restricted herb), ], ], ], Chinese herb mixtures, ], herbs containing certain flavonoids, ], ], ], and ].<ref name ="ErnstE">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ernst E | title = Harmless herbs? A review of the recent literature | journal = The American Journal of Medicine | volume = 104 | issue = 2 | pages = 170–8 | date = February 1998 | pmid = 9528737 | doi = 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00397-5 | name-list-style = vanc }}</ref> Examples of herbs that may have long-term adverse effects include ], the endangered herb ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] (which is banned in the European Union), ], ], ], the restricted herb ], and ].<ref name="LewisME"/> | |||

| ===Safety=== | |||

| ]'' is a highly effective treatment for asthma symptoms when smoked, because it contains ], which acts as an antispasmodic in the lungs. However, datura is also an extremely powerful ] and overdoses of the ] in it can result in hospitalization or death.]] | |||

| {{For|partial list of herbs with known adverse effects|List of herbs with known adverse effects}}A number of herbs are thought to be likely to cause adverse effects.<ref name="Talalay">{{cite journal | last1 = Talalay | first1 = P | last2 = Talalay | first2 = P | title = The importance of using scientific principles in the development of medicinal agents from plants | journal = Academic Medicine | volume = 76 | issue = 3 | pages = 238–47 | year = 2001 | pmid = 11242573 | doi = 10.1097/00001888-200103000-00010 }}</ref> Furthermore, "adulteration, inappropriate formulation, or lack of understanding of plant and drug interactions have led to adverse reactions that are sometimes life threatening or lethal.<ref name="LewisME">{{cite journal | doi = 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00394-9 | last1 = Elvin-Lewis | first1 = M. | author-separator =, | author-name-separator= | year = 2001 | title = Should we be concerned about herbal remedies | url = | journal = Journal of Ethnopharmacology | volume = 75 | issue = 2–3| pages = 141–164 | pmid = 11297844 }}</ref>" Proper double-blind clinical trials are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of each plant before they can be recommended for medical use.<ref name="pmid17761132">{{cite journal|author=Vickers AJ|title=Which botanicals or other unconventional anticancer agents should we take to clinical trial?|journal=J Soc Integr Oncol|volume=5|issue=3|pages=125–9|year=2007|pmid=17761132|doi=10.2310/7200.2007.011|pmc=2590766}}</ref> Although many consumers believe that herbal medicines are safe because they are "natural", herbal medicines and synthetic drugs may interact, causing toxicity to the patient. Herbal remedies can also be dangerously contaminated, and herbal medicines without established efficacy, may unknowingly be used to replace medicines that do have corroborated efficacy.<ref name="pmid17913230">{{cite journal|author=Ernst E|title=Herbal medicines: balancing benefits and risks|journal=Novartis Found. Symp.|volume=282|pages=154–67; discussion 167–72, 212–8 | |||

| |year=2007|pmid=17913230|doi=10.1002/9780470319444.ch11|series=Novartis Foundation Symposia|isbn=978-0-470-31944-4}}</ref> | |||

| There is also concern with respect to the numerous well-established interactions of herbs and drugs.<ref name="LewisME"/><ref name="Izzo 2012 pp. 404–428">{{cite journal | vauthors = Izzo AA | title = Interactions between herbs and conventional drugs: overview of the clinical data | journal = Medical Principles and Practice | volume = 21 | issue = 5 | pages = 404–28 | date = 2012 | pmid = 22236736 | doi = 10.1159/000334488 | doi-access = free }}</ref> In consultation with a physician, usage of herbal remedies should be clarified, as some herbal remedies have the potential to cause adverse drug interactions when used in combination with various prescription and ] pharmaceuticals, just as a customer should inform a herbalist of their consumption of actual prescription and other medication.<ref name="NCCIH 2015">{{cite web | title=Herb-Drug Interactions | website=NCCIH | date=10 September 2015 | url=https://nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/digest/herb-drug | access-date=26 June 2019 | archive-date=26 June 2019 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190626162518/https://nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/digest/herb-drug | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Kuhn 2002 pp. 22–32">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kuhn MA | title = Herbal remedies: drug-herb interactions | journal = Critical Care Nurse | volume = 22 | issue = 2 | pages = 22–8, 30, 32; quiz 34–5 | date = April 2002 | pmid = 11961942 | doi = 10.4037/ccn2002.22.2.22 }}</ref> | |||

| Standardization of purity and dosage is not mandated in the United States, but even products made to the same specification may differ as a result of biochemical variations within a species of plant.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/425061|title=Botanical Products}}</ref> Plants have chemical defense mechanisms against predators that can have adverse or lethal effects on humans. Examples of highly toxic herbs include poison hemlock and nightshade.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Love potions and the ointment of witches: historical aspects of the nightshade alkaloids | journal = J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. | volume = 36 | issue = 6 | pages = 617–27 | year = 1998| doi =10.3109/15563659809028060 | pmid = 9776969 | last1 =Müller | |||

| | first1 =JL }}</ref> They are not marketed to the public as herbs, because the risks are well known, partly due to a long and colorful history in Europe, associated with "sorcery", "magic" and intrigue.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Solanaceae III: henbane, hags and Hawley Harvey Crippen | journal = J R Coll Physicians Edinb. | volume = 36 | issue = 4 | pages =366–73 |date=December 2006 | pmid = 17526134 | last1 =Lee | first1 =MR }}</ref> Although not frequent, adverse reactions have been reported for herbs in widespread use.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | title = Adverse effects associated with herbal medicine | journal = Aust Fam Physician. | volume = 30 | issue = 11 | pages =1070–5 |date=November 2001 | pmid = 11759460 | |||

| | last1 =Pinn | first1 =G }}</ref> On occasion serious untoward outcomes have been linked to herb consumption. A case of major potassium depletion has been attributed to chronic licorice ingestion.,<ref>{{cite journal | title = An unusual cause of hypokalemic paralysis: chronic licorice ingestion | journal =] | |||

| | volume = 325 | issue = 3 | pages =153–6 |date=March 2003 | doi =10.1097/00000441-200303000-00008 | pmid = 12640291 | author =Lin, Shih-Hua | last2 =Yang | first2 =SS | last3 =Chau | first3 =T | last4 =Halperin | first4 =ML }}</ref> and consequently professional herbalists avoid the use of licorice where they recognize that this may be a risk. Black cohosh has been implicated in a case of liver failure.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Fulminant hepatic failure associated with the use of black cohosh: a case report | journal = Liver Transpl. | volume = 12 | issue = 6 | pages =989–92 |date=June 2006 | doi =10.1002/lt.20778 | pmid = 16721764 | author =Lynch, Christopher R. | last2 =Folkers | first2 =ME | last3 =Hutson | first3 =WR }}</ref> | |||

| Few studies are available on the safety of herbs for pregnant women,<ref>{{cite journal | title = Herb use in pregnancy: what nurses should know | journal = MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. | volume = 30 | issue = 3 | pages =201–6 | date=May 2005-June | pmid = 15867682 | last1 =Born | first1 =D | last2 =Barron | first2 =ML | doi=10.1097/00005721-200505000-00009}}</ref><ref>, Gaia Garden website</ref> and one study found that use of complementary and alternative medicines are associated with a 30% lower ongoing pregnancy and live birth rate during fertility treatment.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Boivin | first1=J. | last2=Schmidt | first2=L. | title=Use of complementary and alternative medicines associated with a 30% lower onging pregnancy/live birth rate during 12 months of fertility treatment | journal=Human Reproduction |volume=21 |year=2009 |issue=7 |pages=1626–1631 | doi = 10.1093/humrep/dep077 | author-separator =, | author-name-separator= }}</ref> Examples of herbal treatments with likely cause-effect relationships with adverse events include aconite, which is often a legally restricted herb, ayurvedic remedies, broom, chaparral, Chinese herb mixtures, comfrey, herbs containing certain flavonoids, germander, guar gum, liquorice root, and pennyroyal.<ref name ="ErnstE">{{cite journal | last1 = Ernst | first1 = E | author-separator =, | author-name-separator= | title = Harmless Herbs? A Review of the Recent Literature | url = http://toxicology.usu.edu/endnote/Harmless-Herbs.pdf | format=PDF | accessdate=27 December 2010 | journal = The American Journal of Medicine | volume = 104 | issue = 2 | pages = 170–8| year = 1998| pmid=9528737 | doi=10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00397-5}}</ref> Examples of herbs where a high degree of confidence of a risk long term adverse effects can be asserted include ginseng, which is unpopular among herbalists for this reason, the endangered herb goldenseal, milk thistle, senna, against which herbalists generally advise and rarely use, aloe vera juice, buckthorn bark and berry, cascara sagrada bark, saw palmetto, valerian, kava, which is banned in the European Union, St. John's wort, Khat, Betel nut, the restricted herb Ephedra, and Guarana.<ref name="LewisME"/> | |||

| For example, dangerously low blood pressure may result from the combination of a herbal remedy that lowers blood pressure together with prescription medicine that has the same effect. Some herbs may amplify the effects of anticoagulants.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Spolarich AE, Andrews L | title = An examination of the bleeding complications associated with herbal supplements, antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications | journal = Journal of Dental Hygiene | volume = 81 | issue = 3 | pages = 67 | date = Summer 2007 | pmid = 17908423 | url = http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb6368/is_3_81/ai_n31843689/ | access-date = 28 December 2010 | archive-date = 12 October 2011 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20111012175719/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb6368/is_3_81/ai_n31843689/ | url-status = live }}</ref> | |||

| There is also concern with respect to the numerous well-established interactions of herbs and drugs.<ref name="LewisME"/> In consultation with a physician, usage of herbal remedies should be clarified, as some herbal remedies have the potential to cause adverse drug interactions when used in combination with various prescription and ] pharmaceuticals, just as a patient should inform an herbalist of their consumption of orthodox prescription and other medication. | |||

| Certain herbs as well as common fruit interfere with cytochrome P450, an enzyme critical to much drug metabolism.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Nekvindová J, Anzenbacher P | title = Interactions of food and dietary supplements with drug metabolising cytochrome P450 enzymes | journal = Ceska a Slovenska Farmacie | volume = 56 | issue = 4 | pages = 165–73 | date = July 2007 | pmid = 17969314 }}</ref> | |||

| In a 2018 study, the FDA identified active ] in over 700 analyzed dietary supplements sold as "herbal", "natural" or "traditional".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/10/12/656875443/no-wonder-it-works-so-well-there-may-be-viagra-in-that-herbal-supplement|vauthors=Cohen R|title=No Wonder It Works So Well: There May Be Viagra In That Herbal Supplement|website=NPR.org|language=en|date=12 October 2018|access-date=13 October 2018|archive-date=13 October 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181013010847/https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/10/12/656875443/no-wonder-it-works-so-well-there-may-be-viagra-in-that-herbal-supplement|url-status=live}}</ref> The undisclosed additives included "unapproved antidepressants and designer steroids", as well as ]s, such as ] or ]. | |||

| For example, dangerously low blood pressure may result from the combination of an herbal remedy that lowers blood pressure together with prescription medicine that has the same effect. Some herbs may amplify the effects of anticoagulants.<ref>{{cite journal | title = An examination of the bleeding complications associated with herbal supplements, antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications | journal = J Dent Hyg. | volume = 81 | issue = 3 | pages =67 | date = Summer 2007 | url = http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb6368/is_3_81/ai_n31843689/ | doi = | pmid = 17908423 | accessdate = | last1 =Spolarich | first1 =AE | last2 =Andrews | first2 =L }}</ref> | |||

| Certain herbs as well as common fruit interfere with cytochrome P450, an enzyme critical to much drug metabolism.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Interactions of food and dietary supplements with drug metabolising cytochrome P450 enzymes | journal = Ceska Slov Farm. | volume = 56 | issue = 4 | pages =165–73 |date=July 2007 | url = | doi = | pmid = 17969314 | accessdate = | last1 =Nekvindová | first1 =J | last2 =Anzenbacher | first2 =P }}</ref> | |||

| ===Labeling accuracy=== | |||

| A 2013 study published in the journal BMC Medicine found that one-third of herbal supplements sampled contained no trace of the herb listed on the label. The study found products adulterated with filler including allergens such as soy, wheat, and black walnut. One bottle labeled as St. John's Wort was found to actually contain Alexandrian senna, a laxative.<ref>{{cite web|last=O’CONNOR|first=ANAHAD|title=Herbal Supplements Are Often Not What They Seem|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/05/science/herbal-supplements-are-often-not-what-they-seem.html?_r=1&adxnnl=1&adxnnlx=1383945465-XvljD6UxwpzyAWUPgcqK3A&|publisher=]|accessdate=12 November 2013}}</ref> | |||

| Researchers at the ] found in 2014 that almost 20 percent of herbal remedies surveyed were not registered with the ], despite this being a condition for their sale.<ref name="carroll">{{cite web|url=http://www.smh.com.au/national/health/herbal-medicines-study-raises-alarm-over-labelling-20140223-33aex.html|title=Herbal medicines: Study raises alarm over labelling|vauthors=Carroll L|publisher=The Sydney Morning Herald, Australia|date=24 February 2014|access-date=25 February 2017|archive-date=26 February 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170226050056/http://www.smh.com.au/national/health/herbal-medicines-study-raises-alarm-over-labelling-20140223-33aex.html|url-status=live}}</ref> They also found that nearly 60 percent of products surveyed had ingredients that did not match what was on the label. Out of 121 products, only 15 had ingredients that matched their TGA listing and packaging.<ref name=carroll/> | |||

| In 2015, the ] issued ] letters to four major U.S. retailers (], ], ], and ]) who were accused of selling herbal supplements that were mislabeled and potentially dangerous.<ref>{{cite news|vauthors=O'Connor A|title=New York Attorney General Targets Supplements at Major Retailers|url=http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/03/new-york-attorney-general-targets-supplements-at-major-retailers/|access-date=3 February 2015|work=]|date=3 February 2015|archive-date=28 April 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190428162113/https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/02/03/new-york-attorney-general-targets-supplements-at-major-retailers/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|vauthors=Kaplan S|title=GNC, Target, Wal-Mart, Walgreens accused of selling adulterated 'herbals'|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/02/03/gnc-target-wal-mart-walgreens-accused-of-selling-fake-herbals/|access-date=3 February 2015|newspaper=]|date=3 February 2015|archive-date=24 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190524214941/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/02/03/gnc-target-wal-mart-walgreens-accused-of-selling-fake-herbals/|url-status=live}}</ref> Twenty-four products were tested by ] as part of the investigation, with all but five containing DNA that did not match the product labels. | |||

| Researchers at the ] found in 2014 that almost 20 per cent of herbal remedies surveyed were not registered with the Therapeutic Goods Administration, despite this being a condition for their sale. They also found that nearly 60 per cent of products surveyed had ingredients that did not match what was on the label. Out of 121 products, only 15 had ingredients that matched their TGA listing and packaging.<ref>Sydney Morning Herald, 2014-2-24, p.10</ref> | |||

| ===Practitioners=== | ===Practitioners of herbalism=== | ||

| ]'']] | ]''.]] | ||

| An herbalist is:<ref>''Webster's Unabridged''; 1977</ref><ref>''Webster's New International Dictionary''; 1934</ref><ref>''Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary''; 1971</ref> | |||

| In some countries, formalized training and minimum education standards exist for herbalists, although these are not necessarily uniform within or between countries. In Australia, for example, the self-regulated status of the profession (as of 2009) resulted in variable standards of training, and numerous loosely formed associations setting different educational standards.<ref name="lin">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lin V, McCabe P, Bensoussan A, Myers S, Cohen M, Hill S, Howse G | title = The practice and regulatory requirements of naturopathy and western herbal medicine in Australia | journal = Risk Management and Healthcare Policy | volume = 2 | pages = 21–33 | year = 2009 | pmid = 22312205 | pmc = 3270908 | doi = 10.2147/RMHP.S4652 | doi-access = free }}</ref> One 2009 review concluded that regulation of herbalists in Australia was needed to reduce the risk of interaction of herbal medicines with ]s, to implement clinical guidelines and prescription of herbal products, and to assure self-regulation for protection of public health and safety.<ref name=lin/> In the United Kingdom, the training of herbalists is done by state-funded universities offering Bachelor of Science degrees in herbal medicine.<ref name="The National Institute of Medical Herbalists">{{cite web | title=Becoming a Herbalist | website=The National Institute of Medical Herbalists | url=https://www.nimh.org.uk/becoming-a-herbalist | access-date=26 June 2019 | archive-date=26 June 2019 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190626164329/https://www.nimh.org.uk/becoming-a-herbalist | url-status=live }}</ref> In the United States, according to the American Herbalist Guild, "there is currently no licensing or certification for herbalists in any state that precludes the rights of anyone to use, dispense, or recommend herbs."<ref name="American Herbalist Guild">{{cite web | title=Legal and Regulatory FAQs | website=American Herbalist Guild | date=24 January 2014 | url=https://www.americanherbalistsguild.com/legal-and-regulatory-faqs | access-date=25 November 2020 | archive-date=24 November 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201124100420/https://www.americanherbalistsguild.com/legal-and-regulatory-faqs | url-status=live }}</ref> However, there are U.S. federal restrictions for marketing herbs as cures for medical conditions, or essentially practicing as an unlicensed physician. | |||

| #A person whose life is dedicated to the economic or medicinal uses of plants. | |||

| #One skilled in the harvesting and collection of medicinal plants (see wildcrafter). | |||

| #Traditional Chinese herbalist: one who is trained or skilled in the dispensing of herbal prescriptions; traditional Chinese herb doctor. Similarly, Traditional Ayurvedic herbalist: one who is trained or skilled in the dispensing of herbal prescriptions in the Ayurvedic tradition. | |||

| #One trained or skilled in the therapeutic use of medicinal plants. | |||

| ===United States herbalism fraud=== | |||

| Herbalists must learn many skills, including the ] or cultivation of herbs, diagnosis and treatment of conditions or dispensing herbal medication, and preparations of herbal medications. Education of herbalists varies considerably in different areas of the world. Lay herbalists and traditional indigenous ] generally rely upon apprenticeship and recognition from their communities in lieu of formal schooling. | |||

| Over the years 2017–2021, the ] (FDA) issued ] to numerous herbalism companies for illegally marketing products under "conditions that cause them to be drugs under section 201(g)(1) of the Act , because they are intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease and/or intended to affect the structure or any function of the body" when no such evidence existed.<ref name="fda-fraud">{{cite web |title=2017 Warning Letters – Health Fraud |url=https://www.fda.gov/consumers/health-fraud-scams/2017-warning-letters-health-fraud |publisher=US Food and Drug Administration |access-date=2 April 2021 |date=27 February 2017 |archive-date=9 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210509110850/https://www.fda.gov/consumers/health-fraud-scams/2017-warning-letters-health-fraud |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="FDA2017">{{cite web | title=Warning Letter – Herbal Doctor Remedies | publisher=U.S. Food and Drug Administration | url=https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/herbal-doctor-remedies-515519-05252017 | vauthors=Porter Jr SE | date=25 May 2017 | access-date=25 November 2020 | archive-date=2 December 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201202212726/https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/herbal-doctor-remedies-515519-05252017 | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="fda-covid">{{cite web |title=Fraudulent Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Products |url=https://www.fda.gov/consumers/health-fraud-scams/fraudulent-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-products |publisher=US Food and Drug Administration |access-date=2 April 2021 |date=2 April 2021 |archive-date=5 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210305182557/https://www.fda.gov/consumers/health-fraud-scams/fraudulent-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-products |url-status=live }}</ref> During the ], the FDA and U.S. ] issued ] to several hundred American companies for promoting false claims that herbal products could prevent or treat ].<ref name=fda-covid/><ref name="bellamy">{{cite web |vauthors=Bellamy J |title=FDA and FTC issue more warning letters citing products and services making illegal COVID claims |url=https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/fda-and-ftc-issue-more-warning-letters-citing-products-and-services-making-illegal-covid-claims/ |publisher=Science-Based Medicine |access-date=2 April 2021 |date=19 November 2020 |archive-date=14 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210114200429/https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/fda-and-ftc-issue-more-warning-letters-citing-products-and-services-making-illegal-covid-claims/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Government regulations=== | |||

| In some countries formalized training and minimum education standards exist, although these are not necessarily uniform within or between countries. For example, in Australia the currently self-regulated status of the profession (as of April 2008) results in different associations setting different educational standards, and subsequently recognising an educational institution or course of training. The National Herbalists Association of Australia is generally recognised as having the most rigorous professional standard within Australia.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Breakspear I | year = 2006 | title = Education and Regulation in Herbal Medicine: An Australian Perspective | url = | journal = Journal of the American Herbalists Guild | volume = 6 | issue = 2| pages = 35–38 }}</ref> In the ], the training of medical herbalists is done by state funded Universities. For example, ] degrees in herbal medicine are offered at Universities such as ], ], ], ], ] and ] in Edinburgh at the present.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} | |||

| The ] (WHO), the specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) that is concerned with international public health, published ''Quality control methods for medicinal plant materials'' in 1998 to support WHO Member States in establishing quality standards and specifications for herbal materials, within the overall context of quality assurance and control of herbal medicines.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/h1791e/h1791e.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140801100849/http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/h1791e/h1791e.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-date=1 August 2014|title=WHO Quality Control Methods for Herbal Materials|date=2011|publisher=World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland}}</ref> | |||

| In the European Union (EU), herbal medicines are regulated under the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000208.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05800240cf|title=Herbal medicinal products|date=2017|publisher=European Medicines Agency|access-date=25 February 2017|archive-date=15 March 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170315200330/http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000208.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05800240cf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === Government regulations === | |||

| The ] (WHO), the specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) that is concerned with international public health, published ''Quality control methods for medicinal plant materials'' in 1998 in order to support WHO Member States in establishing quality standards and specifications for herbal materials, within the overall context of quality assurance and control of herbal medicines.<ref></ref> | |||

| In the United States, herbal remedies are regulated ] by the ] (FDA) under ] (cGMP) policy for dietary supplements.<ref name="ods2011">{{cite web|url=https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/BotanicalBackground-HealthProfessional/|publisher=Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health|title=Botanical Dietary Supplements|date=June 2011|access-date=25 February 2017|archive-date=20 October 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181020220552/http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/BotanicalBackground-HealthProfessional/|url-status=live}}</ref> Manufacturers of products falling into this category are not required to prove the safety or efficacy of their product so long as they do not make 'medical' claims or imply uses other than as a 'dietary supplement', though the FDA may withdraw a product from sale should it prove harmful.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/opacom/laws/dshea.html|title=US Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994|website=]|access-date=16 December 2019|archive-date=31 May 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090531213336/http://www.fda.gov/opacom/laws/dshea.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Goldman P | title = Herbal medicines today and the roots of modern pharmacology | journal = Annals of Internal Medicine | volume = 135 | issue = 8 Pt 1 | pages = 594–600 | date = October 2001 | pmid = 11601931 | doi = 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_Part_1-200110160-00010 | s2cid = 35766876 }}</ref> | |||

| In the ] (EU), herbal medicines are now regulated under the ]. | |||

| Canadian regulations are described by the Natural and Non-prescription Health Products Directorate which requires an eight-digit Natural Product Number or Homeopathic Medicine Number on the label of licensed herbal medicines or dietary supplements.<ref name="hc">{{cite web|url=http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodnatur/applications/licen-prod/lnhpd-bdpsnh-eng.php|title=Licensed Natural Health Products Database: What is it?|publisher=Health Canada|date=8 December 2016|access-date=25 February 2017|archive-date=4 June 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170604083408/http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodnatur/applications/licen-prod/lnhpd-bdpsnh-eng.php|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In the ], most herbal remedies are loosely regulated ] by the ].{{Citation needed|date=July 2007}} Manufacturers of products falling into this category are not required to prove the safety or efficacy of their product, though the FDA may withdraw a product from sale should it prove harmful.<ref></ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Goldman P |title=Herbal medicines today and the roots of modern pharmacology |journal=Annals of Internal Medicine |volume=135 |issue=8 Pt 1 |pages=594–600 |year=2001 |pmid=11601931 |doi=10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_Part_1-200110160-00010}}</ref> | |||

| Some herbs, such as ] and ], are outright banned in most countries though coca is legal in most of the South American countries where it is grown. The ] is used as a herbal ], and as such is ] in some parts of the world. Since 2004, the sales of ] as a dietary supplement is prohibited in the United States by the FDA,<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070915111213/http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~lrd/fpephed6.html |date=15 September 2007 }}</ref> and subject to Schedule III restrictions in the United Kingdom. | |||

| The ], the industry's largest trade association, has run a program since 2002, examining the products and factory conditions of member companies, giving them the right to display the ] (]) seal of approval on their products.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} | |||

| ===Scientific criticism=== | |||

| Some herbs, such as ] and ], are outright banned in most countries though coca is legal in most of the ]n countries where it is grown. The ] is used as a herbal ], and as such is ] in some parts of the world. Since 2004, the sales of ] as a dietary supplement is prohibited in the United States by the ].,<ref></ref> and subject to Schedule III restrictions in the United Kingdom. | |||

| Herbalism has been criticized as a potential "]" of unreliable product quality, safety hazards, and the potential for misleading health advice.<ref name=swallow/><ref name="quackwatch">{{cite web|url=https://quackwatch.org/related/herbs/|title=The Herbal Minefield|vauthors=Barrett S|author-link=Stephen Barrett|publisher=Quackwatch|date=23 November 2013|access-date=25 February 2017|archive-date=5 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200805172021/https://quackwatch.org/related/herbs/|url-status=live}}</ref> Globally, there are no standards across various herbal products to authenticate their contents, safety or efficacy,<ref name=bmc2013/> and there is generally an absence of high-quality scientific research on product composition or effectiveness for anti-disease activity.<ref name=quackwatch/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/92455/1/9789241506090_eng.pdf?ua=1|publisher=World Health Organization|title=WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy, 2014–2023|page=41|date=2013|access-date=25 February 2017|archive-date=18 November 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171118192156/http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/92455/1/9789241506090_eng.pdf?ua=1|url-status=live}}</ref> Presumed claims of therapeutic benefit from herbal products, without rigorous evidence of efficacy and safety, receive skeptical views by scientists.<ref name=swallow/> | |||

| Unethical practices by some herbalists and manufacturers, which may include false advertising about health benefits on product labels or literature,<ref name=quackwatch/> and contamination or use of fillers during product preparation,<ref name=bmc2013/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhang J, Wider B, Shang H, Li X, Ernst E | title = Quality of herbal medicines: challenges and solutions | journal = Complementary Therapies in Medicine | volume = 20 | issue = 1–2 | pages = 100–6 | year = 2012 | pmid = 22305255 | doi = 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.09.004 }}</ref> may erode ] about services and products.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Morris CA, Avorn J | title = Internet marketing of herbal products | journal = JAMA | volume = 290 | issue = 11 | pages = 1505–9 | date = September 2003 | pmid = 13129992 | doi = 10.1001/jama.290.11.1505 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Coghlan ML, Haile J, Houston J, Murray DC, White NE, Moolhuijzen P, Bellgard MI, Bunce M | display-authors = 6 | title = Deep sequencing of plant and animal DNA contained within traditional Chinese medicines reveals legality issues and health safety concerns | journal = PLOS Genetics | volume = 8 | issue = 4 | pages = e1002657 | year = 2012 | pmid = 22511890 | pmc = 3325194 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002657 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ==Traditional herbal medicine systems== | |||

| ==Paraherbalism== | |||

| ] tree contains ], which today is a widely prescribed treatment for ]. The unpurified bark is still used by some who cannot afford to purchase more expensive antimalarial drugs.]] | |||

| '''Paraherbalism''' is the ] use of ]s of plant or animal origin as supposed medicines or health-promoting agents.<ref name=swallow/><ref name="tyler"/><ref name=quackwatch/> Phytotherapy differs from plant-derived medicines in standard ] because it does not isolate and ] the compounds from a given plant believed to be biologically active. It relies on the false belief that preserving the complexity of substances from a given plant with less processing is safer and potentially more effective, for which there is no evidence either condition applies.<ref name=tyler/> | |||

| Phytochemical researcher ] described paraherbalism as "faulty or inferior herbalism based on pseudoscience", using scientific terminology but lacking scientific evidence for safety and efficacy. Tyler listed ten ] that distinguished herbalism from paraherbalism, including claims that there is a ] to suppress safe and effective herbs, herbs cannot cause harm, whole herbs are more effective than molecules isolated from the plants, herbs are superior to drugs, the ] (the belief that the shape of the plant indicates its function) is valid, dilution of substances increases their potency (a doctrine of the pseudoscience of ]), astrological alignments are significant, animal testing is not appropriate to indicate human effects, ] is an effective means of proving a substance works and herbs were created by God to cure disease. Tyler suggests that none of these beliefs have any basis in fact.<ref name="tyler" /><ref name = Tyler>{{cite book | vauthors = Tyler VE, Robbers JE | author-link = Varro Eugene Tyler | year = 1999 | title = Tyler's Herbs of Choice: The Therapeutic Use of Phytomedicinals | publisher = ] | pages = | isbn = 978-0789001597 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Traditional systems== | |||

| {{See also|Traditional medicine}} | {{See also|Traditional medicine}} | ||

| ] medicinal liquor with ], ], and ], for sale at a traditional medicine market in ], |

] medicinal liquor with ], ], and ], for sale at a traditional medicine market in ], China]] | ||

| ===Africa=== | |||

| {{Main|Traditional African medicine}} | |||

| Up to 80% of the population in Africa uses traditional medicine as primary health care.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/2003/fs134/en/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030608090402/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/2003/fs134/en/|url-status=dead|archive-date=8 June 2003|title=Traditional medicine, Factsheet No. 134|publisher=World Health Organization|date=May 2003}}</ref> | |||

| ===Americas=== | |||

| Native Americans used about 2,500 of the approximately 20,000 plant species that are native to North America.<ref>{{Cite book| vauthors = Moerman DE |chapter=Ethnobotany in North America|editor=Selin, Helaine|editor-link=Helaine Selin|title=Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures|publisher=Springer|year=1997|isbn=9780792340669|page=321|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=raKRY3KQspsC&pg=PA321}}</ref> | |||

| In ] healing practices, the use of ]s, in particular the San Pedro cactus ('']'') is still a vital component, and has been around for millennia.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bussmann RW, Sharon D | title = Traditional medicinal plant use in Northern Peru: tracking two thousand years of healing culture | journal = Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine | volume = 2 | issue = 1 | pages = 47 | date = November 2006 | pmid = 17090303 | pmc = 1637095 | doi = 10.1186/1746-4269-2-47 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ===China=== | |||

| Some researchers trained in both Western and ] have attempted to deconstruct ancient medical texts in the light of modern science. In 1972, ], a pharmaceutical chemist and ], extracted the anti-malarial drug ] from ], a traditional Chinese treatment for intermittent fevers.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yuan D, Yang X, Guo JC | title = A great honor and a huge challenge for China: You-you TU getting the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine | journal = Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B | volume = 17 | issue = 5 | pages = 405–8 | date = May 2016 | pmid = 27143269 | pmc = 4868832 | doi = 10.1631/jzus.B1600094 }}</ref> | |||

| ===India=== | |||

| ] | |||

| In India, ] has quite complex formulas with 30 or more ingredients, including a sizable number of ingredients that have undergone "]", chosen to balance ].<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kala CP |title=Preserving Ayurvedic herbal formulations by Vaidyas: The traditional healers of the Uttaranchal Himalaya region in India |journal=HerbalGram |year=2006 |volume=70 |pages=42–50 |url=http://cms.herbalgram.org/herbalgram/issue70/article2969.html |access-date=9 June 2020 |archive-date=18 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200218142556/http://cms.herbalgram.org/herbalgram/issue70/article2969.html |url-status=live }}</ref> In Ladakh, Lahul-Spiti, and Tibet, the ] is prevalent, also called the "Amichi Medical System". Over 337 species of ]s have been documented by ]. Those are used by Amchis, the practitioners of this medical system.<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Kala CP |title=Health traditions of Buddhist community and role of amchis in trans-Himalayan region of India|journal=Current Science|year=2005|volume=89|issue=8|pages=1331–38}}</ref><ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Kala CP |title=Medicinal plants of Indian trans-Himalaya|year=2003|publisher=Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh|location=Dehradun|pages=200}}</ref> The Indian book, Vedas, mentions treatment of diseases with plants.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Petrovska BB | title = Historical review of medicinal plants' usage | journal = Pharmacognosy Reviews | volume = 6 | issue = 11 | pages = 1–5 | date = January 2012 | pmid = 22654398 | pmc = 3358962 | doi = 10.4103/0973-7847.95849 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ===Indonesia=== | |||

| ] herbal medicines held in bottles]] | |||