| Revision as of 04:19, 7 December 2014 editMontanabw (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers105,438 edits →Origins: Removing unsourced WP:OR, See talk← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:13, 20 December 2024 edit undoAithus (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users17,393 edits Undid revision 1263961574 by Hyperbigbang (talk) irrelevant statement (this article is not about Buddhism in Japan) with broken citationTag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2021}} | |||

| {{Tibetan Buddhism sidebar}} | |||

| {{Vajrayana}} | |||

| {{Buddhism}} | |||

| ] | |||

| '''Tibetan Buddhism'''{{efn|Also known as '''Tibeto-Mongol Buddhism''', '''Indo-Tibetan Buddhism''', '''Lamaism''', '''Lamaistic Buddhism''', '''Himalayan Buddhism''', and '''Northern Buddhism'''}} is a form of ] practiced in ], ] and ]. It also has a sizable number of adherents in the areas surrounding the ], including the ]n regions of ], ], ], and ] (], as well as in ]. Smaller groups of practitioners can be found in ], some regions of China such as ], ], ] and some regions of Russia, such as ], ], and ]. | |||

| Tibetan Buddhism evolved as a form of ] Buddhism stemming from the latest stages of ] (which included many ] elements). It thus preserves many Indian Buddhist ] practices of the ] ] period (500–1200 CE), along with numerous native Tibetan developments.<ref>{{Cite book|editor-last= White|editor-first= David Gordon |title= Tantra in Practice|publisher= Princeton University Press|year= 2000|isbn= 0-691-05779-6|page= 21}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Davidson |first=Ronald M. |year=2004 |title=Indian Esoteric Buddhism: Social History of the Tantric Movement |page=2 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass}}</ref> In the pre-modern era, Tibetan Buddhism spread outside of Tibet primarily due to the influence of the ] ] (1271–1368), founded by ], who ruled China, Mongolia, and parts of Siberia. In the Modern era, Tibetan Buddhism has spread outside of Asia because of the efforts of the ] (1959 onwards). As the ] escaped to India, the Indian subcontinent is also known for its renaissance of Tibetan Buddhism monasteries, including the rebuilding of the three major monasteries of the ] tradition. | |||

| Apart from classical Mahāyāna Buddhist practices like the ], Tibetan Buddhism also includes tantric practices, such as ] and the ], as well as methods that are seen as transcending tantra, like ]. Its main goal is ].{{sfnp|Powers|2007|pp=392–3, 415}}<ref>Compare: {{cite book |last1=Tiso |first1= Francis V. |author-link1=Francis Tiso |chapter=Later Developments in Dzogchen History |title=Rainbow Body and Resurrection: Spiritual Attainment, the Dissolution of the Material Body, and the Case of Khenpo A Chö |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JLzvCAAAQBAJ |location=Berkeley, California |publisher=North Atlantic Books |date=2016 |isbn=9781583947968 |access-date=11 September 2020 |quote=The attainment of the rainbow body ('ja' lus) as understood by the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism is always connected to the practice of the great perfection . The Nyingma tradition describes a set of nine vehicles, the highest of which is that of the great perfection, considered the swiftest of the tantric methods for attaining supreme realization, identified with buddhahood. }}</ref> The primary language of scriptural study in this tradition is ]. | |||

| Tibetan Buddhism has four major schools, namely ] (8th century), ] (11th century), ] (1073), and ] (1409). The ] is a smaller school that exists, and the ] (19th century), meaning "no sides",<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.palri.org/nyingma-buddhism/ |title=A Brief History of Nyingma Buddhism |date=23 May 2019 |publisher=Palri Pema Od Ling}}</ref> is a more recent non-sectarian movement that attempts to preserve and understand all the different traditions. The predominant ] in Tibet before the introduction of Buddhism was ], which has been strongly influenced by Tibetan Buddhism (particularly the Nyingma school). While each of the four major schools is independent and has its own monastic institutions and leaders, they are closely related and intersect with common contact and dialogue. | |||

| {{TOC limit|2}} | |||

| ==Nomenclature== | |||

| The native Tibetan term for Buddhism is "The ] of the insiders" (''nang chos'') or "The Buddha Dharma of the insiders" (''nang pa sangs rgyas pa'i chos'').<ref>{{cite book |author=Dzogchen Ponlop |title=Wild Awakening: The Heart of Mahamudra and Dzogchen |chapter=Glossary}}{{full citation needed|date=March 2024}}</ref><ref name="Powers-2012">{{cite book |last1=Powers |first1=John |last2=Templeman |first2=David |year=2012 |title=Historical Dictionary of Tibet |publisher=Scarecrow Press |page=566}}</ref> "Insider" means someone who seeks the truth not outside but within the nature of mind. This is contrasted with other forms of organized religion, which are termed ''chos lugs'' (dharma system)''.'' For example, ] is termed ''Yi shu'i chos lugs'' (Jesus dharma system)''.<ref name="Powers-2012" />'' | |||

| Westerners unfamiliar with Tibetan Buddhism initially turned to China for understanding. In Chinese, the term used is ''Lamaism'' (literally, "doctrine of the lamas": {{lang|zh|喇嘛教}} ''lama jiao'') to distinguish it from a then-traditional ] ({{lang|zh|佛教}} ''fo jiao''). The term was taken up by western scholars, including ], as early as 1822.<ref>{{cite book |last=Lopez |first=Donald S. Jr. |author-link=Donald S. Lopez, Jr. |title=Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West |year=1999 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |location=Chicago |isbn=0-226-49311-3 |pages= |url=https://archive.org/details/prisonersofshang00dona/page/6 }}</ref><ref>Damien Keown, ed., "Lamaism", ''A Dictionary of Buddhism'' (Oxford, 2004): "an obsolete term formerly used by Western scholars to denote the specifically Tibetan form of Buddhism due to the prominence of the lamas in the religious culture. . . should be avoided as it is misleading as well as disliked by Tibetans." Robert E. Buswell Jr. and David S. Lopez Jr., eds., "Lamaism", ''The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism'' (Princeton, 2017): "an obsolete English term that has no correlate in Tibetan. . . Probably derived from the Chinese term ''lama jiao'', or "teachings of the lamas", the term is considered pejorative by Tibetans, as it carries the negative connotation that the Tibetan tradition is something distinct from the mainstream of Buddhism." John Bowker, ed., "Lamaism", ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions'' (Oxford, 2000): "a now antiquated term used by early W commentators (as L. A. Waddell, ''The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism'', 1895) to describe Tibetan Buddhism. Although the term is not accurate does at least convey the great emphasis placed on the role of the spiritual teacher by this religion."</ref> Insofar as it implies a discontinuity between Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, the term has been discredited.{{sfnp|Conze|1993}} | |||

| Another term, "]" (Tibetan: ''dorje tegpa'') is occasionally misused for Tibetan Buddhism. More accurately, ] signifies a certain subset of practices and traditions that are not only part of Tibetan Buddhism but also prominent in other Buddhist traditions such as ]<ref>{{Cite web |title=T'ang Dynasty Esoteric School, Buddha, China |url=http://www.tangmi.com/asd/English_TDES.htm |access-date=2023-09-07 |website=www.tangmi.com}}</ref> and ] in ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Shingon Buddhist Intl. Institute: History |url=http://www.shingon.org/history/history.html |access-date=2023-09-07 |website=www.shingon.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=What is the Koyasan Shingon Sect? {{!}} Koyasan Shingon Sect Main Temple Kongobu-ji |url=https://www.koyasan.or.jp/en/ |access-date=2023-09-07 |website=www.koyasan.or.jp |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In the west, the term "Indo-Tibetan Buddhism" has become current in acknowledgement of its derivation from the latest stages of Buddhist development in northern India.{{sfnp|Snellgrove|1987|p={{page needed|date=March 2024}}}} "]" is sometimes used to refer to Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, for example, in the Brill ''Dictionary of Religion.'' | |||

| Another term, "Himalayan" (or "Trans-Himalayan") Buddhism is sometimes used to indicate how this form of Buddhism is practiced not just in Tibet but throughout the ].<ref>see for example the title of Suchandana Chatterjee's ''Trans-Himalayan Buddhism: Reconnecting Spaces, Sharing Concerns'' (2019), Routledge.</ref>{{sfnp|Ehrhard|2005}} | |||

| The Provisional Government of Russia, by a decree of 7 July 1917, prohibited the appellation of Buryat and Kalmyk Buddhists as "Lamaists" in official papers. After the October revolution the term "Buddho-Lamaism" was used for some time by the Bolsheviks with reference to Tibetan Buddhism, before they finally reverted, in the early 1920s, to a more familiar term "Lamaism", which remains in official and scholarly usage in Russia to this day.<ref>{{cite book |title=Soviet Russia and Tibet The Debacle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918-1930s |last=Andreyev |first=Alexandr E. |date=January 1, 2003 |publisher=Brill |isbn=9789004487871 |edition=Brill's Tibetan Studies Library, Volume: 4 |url=https://brill.com/display/book/9789004487871/B9789004487871_s005.xml |access-date=11 April 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Main|History of Tibetan Buddhism}} | |||

| ===Pre–6th century=== | |||

| During the 3rd century CE, Buddhism began to spread into the Tibetan region, and its teachings affected the Bon religion in the ].<ref> | |||

| {{cite web | url= http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/history/tib_timeline.htm | title=Timeline of Tibetan Buddhist History – Major Events }}</ref> | |||

| ===First dissemination (7th–9th centuries)=== | |||

| {{Main|Tibetan Empire}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 220 | |||

| | image1 = Tibetan empire greatest extent 780s-790s CE.png | |||

| | caption1 = Map of the Tibetan Empire at its greatest extent between the 780s and the 790s CE | |||

| | image2 = A grand view of Samye.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = ] was the first gompa (Buddhist monastery) built in Tibet (775–779). | |||

| }} | |||

| While some stories depict Buddhism in Tibet before this period, the religion was formally introduced during the ] (7th–9th century CE). ] from India were first translated into Tibetan under the reign of the Tibetan king ] (618–649 CE).<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://studybuddhism.com/en/advanced-studies/history-culture/buddhism-in-tibet/tibetan-history-before-the-fifth-dalai-lama/the-empire-of-the-early-kings-of-tibet|title=The Empire of the Early Kings of Tibet|website=studybuddhism.com}}</ref> This period also saw the development of the ] and ].<ref>William Woodville Rockhill, {{Google books|avFDAQAAMAAJ|Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution|page=671}}, United States National Museum, page 671</ref><ref>Berzin, Alexander. ''A Survey of Tibetan History - Reading Notes Taken'' by Alexander Berzin from Tsepon, W. D. Shakabpa, Tibet: A Political History. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1967: http://studybuddhism.com/web/en/archives/e-books/unpublished_manuscripts/survey_tibetan_history/chapter_1.html {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160617115552/http://studybuddhism.com/web/en/archives/e-books/unpublished_manuscripts/survey_tibetan_history/chapter_1.html|date=2016-06-17}}.</ref> | |||

| In the 8th century, King ] (755–797 CE) established it as the official religion of the state<ref>{{cite book |last=Beckwith |first=C. I. |chapter=The revolt of 755 in Tibet |title=The History of Tibet |editor-first=Alex |editor-last=McKay |volume=1 |place=London |publisher=RoutledgeCurzon |year=2003 |pages=273–285 |isbn=9780700715084 |oclc=50494840}} (discusses the political background and the motives of the ruler).</ref> and commanded his army to wear robes and study Buddhism. Trisong Detsen invited Indian Buddhist scholars to his court, including ] (8th century CE) and ] (725–788), who are considered the founders of ] (''The Ancient Ones)'', the oldest tradition of Tibetan Buddhism.<ref name="StudyBuddhism.com">{{cite web |last=Berzin |first=Alexander |year=2000 |title=How Did Tibetan Buddhism Develop? |url=http://studybuddhism.com/en/advanced-studies/history-culture/buddhism-in-tibet/how-did-tibetan-buddhism-develop |website=StudyBuddhism.com}}</ref> Padmasambhava, who is considered by the Tibetans as Guru Rinpoche ("Precious Master"), is also credited with building the first monastery building named "Samye" around the late 8th century. According to some legend, it is noted that he pacified the Bon demons and made them the core protectors of Dharma.<ref>{{cite web |title=How Buddhism Came to Tibet |url=https://www.learnreligions.com/how-buddhism-came-to-tibet-450177 |website=Learn Religion |access-date=13 April 2022}}</ref> Modern historians also argue that Trisong Detsen and his followers adopted Buddhism as an act of international diplomacy, especially with the major power of those times such as China, India, and states in Central Asia that had strong Buddhist influence in their culture.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Van Schaik |first1=Sam |title=Buddhism and Empire IV: Converting Tibet |url=https://earlytibet.com/2009/07/01/buddhism-and-empire-iv-converting-tibet/ |website=Early Tibet |date=July 2009 |access-date=13 April 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ], the most important female in the Nyingma Vajrayana lineage, was a member of Trisong Detsen's court and became Padmasambhava's student before gaining enlightenment. Trisong Detsen also invited the ] master ]{{efn|和尚摩訶衍; his name consists of the same Chinese characters used to transliterate "]" (Tibetan: ''Hwa shang Mahayana'')}} to transmit the Dharma at ]. Some sources state that a debate ensued between Moheyan and the Indian master ], without consensus on the victor, and some scholars consider the event to be fictitious.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131102032603/http://yzzj.fodian.net/BaoKu/FoDianWenInfo.aspx?ID=FW00000462 |date=2013-11-02 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last=Yamaguchi |first=Zuihō |date=n.d. |title=The Core Elements of Indian Buddhism Introduced into Tibet: A Contrast with Japanese Buddhism |url=http://thezensite.com/ZenEssays/Miscellaneous/Indian_buddhism.pdf |website=Thezensite.com |access-date=October 20, 2007}}</ref>{{efn|Kamalaśīla wrote the three ] texts (修習次第三篇) after that.}}{{efn|However, a Chinese source found in ] written by Mo-ho-yen says their side won, and some scholars conclude that the entire episode is fictitious.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://hk.plm.org.cn/qikan/xdfx/5012-012A.htm |title=敦煌唐代写本顿悟大乘正理决 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131101202452/http://hk.plm.org.cn/qikan/xdfx/5012-012A.htm |archive-date=2013-11-01 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |publisher=Macmillan |title=Encyclopedia of Buddhism |volume=1 |page=70}}</ref>}} | |||

| ===Era of fragmentation (9th–10th centuries)=== | |||

| A reversal in Buddhist influence began under King ] (r. 836–842), and his death was followed by the so-called '']'', a period of disunity during the 9th and 10th centuries. During this era, the political centralization of the earlier Tibetan Empire collapsed and civil wars ensued.{{sfnp|Shakabpa|1967|pp=53, 173}} | |||

| In spite of this loss of state power and patronage however, Buddhism survived and thrived in Tibet. According to ] this was because "Tantric (Vajrayana) Buddhism came to provide the principal set of techniques by which Tibetans dealt with the dangerous powers of the spirit world Buddhism, in the form of Vajrayana ritual, provided a critical set of techniques for dealing with everyday life. Tibetans came to see these techniques as vital for their survival and prosperity in this life."{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=10}} This includes dealing with the local gods and spirits (''sadak'' and ''shipdak),'' which became a specialty of some Tibetan Buddhist lamas and ]s (''mantrikas'', mantra specialists).{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|pp=12–13,32}} | |||

| ===Second dissemination (10th–12th centuries)=== | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 200 | |||

| | image1 = Atisha.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = The Indian master Atiśa | |||

| | image2 = Lotsawa Marpa Chokyi Lodro.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = The Tibetan householder and translator ] (1012–1097) | |||

| }} | |||

| The late 10th and 11th centuries saw a revival of Buddhism in Tibet with the founding of "New Translation" (]) lineages as well as the appearance of "]" (''terma'') literature which reshaped the ] tradition.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://studybuddhism.com/en/advanced-studies/history-culture/buddhism-in-tibet/how-did-tibetan-buddhism-develop|title=How Did Tibetan Buddhism Develop?|website=studybuddhism.com}}</ref>{{sfnp|Conze|1993|pp=104ff}} | |||

| In 1042 the Bengali saint, ] (982–1054) arrived in Tibet at the invitation of a west Tibetan king and further aided dissemination of Buddhist values in Tibetan culture and in consequential affairs of state. | |||

| His erudition supported the translation of major Buddhist texts, which evolved into the canons of Bka'-'gyur (Translation of the Buddha Word) and Bstan-'gyur (Translation of Teachings). The ''Bka'-'gyur'' has six main categories: (1) ], (2) ], (3) ], (4) ], (5) Other sutras, and (6) ]. The ''Bstan-'gyur'' comprises 3,626 texts and 224 volumes on such things as hymns, commentaries and suppplementary tantric material. | |||

| Atiśa's chief disciple, ] founded the ] school of Tibetan Buddhism, one of the first Sarma schools.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Dickson |first=Alnis |others=Lara E. Braitstein |title=Organizing religion: situating the three-vow texts of the Tibetan Buddhist renaissance |url=https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/1j92g801p |access-date=2024-08-31 |website=escholarship.mcgill.ca}}</ref> The ] (''Grey Earth'') school, was founded by ] (1034–1102), a disciple of the great ], Drogmi Shākya. It is headed by the ], and traces its lineage to the ] ].<ref name="StudyBuddhism.com"/> | |||

| Other influential Indian teachers include ] (988–1069) and his student ] (probably died ca. 1040). Their teachings, via their student ], are the foundations of the ] (''Oral lineage'') tradition'','' which focuses on the practices of ] and the ]. One of the most famous Kagyu figures was the hermit ], an 11th-century mystic. The ] was founded by the monk ] who merged Marpa's lineage teachings with the monastic Kadam tradition.<ref name="StudyBuddhism.com" /> | |||

| All the sub-schools of the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism surviving today, including the Drikung Kagyu, the Drukpa Kagyu and the Karma Kagyu, are branches of the Dagpo Kagyu. The Karma Kagyu school is the largest of the Kagyu sub-schools and is headed by the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Olderr |first1=Steven |title=Dictionary of World Monasticism |date=2020 |publisher=McFarland |isbn=978-1476683096 |page=101}}</ref> | |||

| ===Mongol dominance (13th–14th centuries)=== | |||

| {{Main|Tibet under Yuan rule}} | |||

| Tibetan Buddhism exerted a strong influence from the 11th century CE among the peoples of ], especially the ], and Tibetan and ] influenced each other. This was done with the help of ] and Mongolian ] influenced by the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Jenott |first=Lance |date=2002-05-07 |title=The Eastern (Nestorian) Church |url=https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/exhibit/religion/nestorians/nestorians.html |access-date=2023-03-01 |website=Silk Road Seattle |publisher=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Nestorians |url=https://www.biblicalcyclopedia.com/N/nestorians.html |access-date=2023-03-01 |website=] |publisher=] |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Chua |first=Amy |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/123079516 |title=Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance–and Why They Fall |publisher=] |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-385-51284-8 |edition=1st |location=] |pages=116–119, 121 |oclc=123079516 |author-link=Amy Chua}}</ref> | |||

| The ] in 1240 and 1244.{{sfnp|Shakabpa|1967|p=61|ps=: 'thirty thousand troops, under the command of Leje and Dorta, reached Phanpo, north of Lhasa.'}}{{sfnp|Sanders|2003|p=309|ps=: ''his grandson Godan Khan invaded Tibet with 30000 men and destroyed several Buddhist monasteries north of Lhasa''}}{{sfnp|Buell|2011|p=194}}{{sfnp|Shakabpa|1967|pp=61–62}} They eventually annexed ] and ] and appointed the great scholar and abbot ] (1182–1251) as Viceroy of Central Tibet in 1249.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://gwydionwilliams.com/42-china/tibet/how-tibet-emerged-within-the-chinese-empire/|title=How Tibet Emerged Within the Wider Chinese Power-Political Zone|date=2015-04-18|work=Long Revolution|access-date=2018-03-23|language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| In this way, Tibet was incorporated into the ], with the Sakya hierarchy retaining nominal power over religious and regional political affairs, while the Mongols retained structural and administrative{{sfnp|Wylie|1990|p=104}} rule over the region, reinforced by the rare military intervention. Tibetan Buddhism was adopted as the ''de facto'' ] by the Mongol ] (1271–1368) of ].<ref name="Huntington_et_al"/> | |||

| It was also during this period that the ] was compiled, primarily led by the efforts of the scholar ] (1290–1364). A part of this project included the carving of the canon into ], and the first copies of these texts were kept at ].{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=162}} | |||

| Tibetan Buddhism in China was also ] with ] and ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Wood |first=Michael |title=The Story of China: The Epic History of a World Power from the Middle Kingdom to Mao and the China Dream |publisher=] |year=2020 |isbn=978-1-250-20257-4 |edition=First U.S. |location=New York |pages=363 |author-link=Michael Wood (historian)}}</ref> | |||

| ===From family rule to Ganden Phodrang government (14th–18th centuries)=== | |||

| ] in Lhasa, chief residence and political center of the ]s. ]] | |||

| With the decline and end of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, Tibet regained independence and was ruled by successive local families from the 14th to the 17th century.{{sfnp|Rossabi|1983|p=194}} | |||

| ] (1302–1364) became the strongest political family in the mid 14th century.<ref>{{cite book |last=Petech |first=L. |title=Central Tibet and The Mongols |series=Serie Orientale Roma |volume=65 |place=Rome |publisher=Instituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente |year=1990 |pages=85–143}}</ref> During this period the reformist scholar ] (1357–1419) founded the ] school which would have a decisive influence on Tibet's history. The ] is the nominal head of the Gelug school, though its most influential figure is the Dalai Lama. The Ganden Tripa is an appointed office and not a reincarnation lineage. The position can be held by an individual for seven years and this has led to more Ganden Tripas than Dalai Lamas <ref>{{cite web |last1=Berzin |first1=Alexander |title=Gelug Monasteries: Ganden |url=http://studybuddhism.com/en/advanced-studies/history-culture/monasteries-in-tibet/gelug-monasteries-ganden |website=Study Buddhism |access-date=13 April 2022}}</ref> | |||

| Internal strife within the ], and the strong localism of the various fiefs and political-religious factions, led to a long series of internal conflicts. The minister family ], based in ] (West Central Tibet), dominated politics after 1435.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Czaja |first=Olaf |date=2013-09-17 |title=On the History of Refining Mercury in Tibetan Medicine |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/15734218-12341290 |journal=Asian Medicine |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=75–105 |doi=10.1163/15734218-12341290 |issn=1573-420X}}</ref> | |||

| In 1565, the Rinpungpa family was overthrown by the ] Dynasty of ], which expanded its power in different directions of Tibet in the following decades and favoured the ] sect. They would play a pivotal role in the events which led to the rise of power of the Dalai Lama's in the 1640s.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| {{See also|Ming–Tibet relations}} | |||

| In China, Tibetan Buddhism continued to be patronized by the elites of the Ming Dynasty. According to ], during this era, Tibetan Buddhist monks "conducted court rituals, enjoyed privileged status and gained access to the jealously guarded, private world of the emperors".<ref>{{cite book |last=Robinson |first=David M. |year=2008 |chapter-url=http://www.history.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/readings/robinson_culture_courtiers_ch.8.pdf |chapter=The Ming Court and the Legacy of the Yuan Mongols |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161006082912/http://www.history.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/readings/robinson_culture_courtiers_ch.8.pdf |archive-date=2016-10-06 |title=Culture, Courtiers and Competition, The Ming Court (1368–1644)}}</ref> The Ming ] (r. 1402–1424) promoted the carving of printing blocks for the ], now known as "the Yongle Kanjur", and seen as an important edition of the collection.<ref>Silk, Jonathan. ''Notes on the history of the Yongle Kanjur.'' Indica et Tibetica 28, Suhrllekhah. Festgabe für Helmut Eimer, 1998.</ref> | |||

| The Ming Dynasty also supported the propagation of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia during this period. Tibetan Buddhist missionaries also helped spread the religion in Mongolia. It was during this era that ] the leader of the ] Mongols, converted to Buddhism, and allied with the Gelug school, conferring the title of Dalai Lama to ] in 1578.<ref>{{cite book |first=Patrick |last=Taveirne |year=2004 |title=Han-Mongol Encounters and Missionary Endeavors: A History of Scheut in Ordos (Hetao) 1874–1911 |publisher=Leuven University Press |pages=67ff |isbn=978-90-5867-365-7}}</ref> | |||

| During a Tibetan civil war in the 17th century, ] (1595–1657 CE), the chief regent of the ], conquered and unified Tibet to establish the '']'' government with the help of the ] of the ]. The ''Ganden Phodrang'' and the successive Gelug ] lineages of the Dalai Lamas and ]s maintained regional control of ] from the mid-17th to mid-20th centuries.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dudeja |first=Jai Paul |title=Profound Meditation Practices in Tibetan Buddhism |publisher=Bluerose Publisher Pvt. Ltd.|date=2023 |page=5 |isbn=978-93-5741-206-3 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Qing rule (18th–20th centuries)=== | |||

| ], a temple of the Gelug tradition in ] established in the Qing Dynasty.]] | |||

| The ] (1644–1912) established a Chinese rule over Tibet after a ] defeated the ] (who controlled Tibet) in 1720, and lasted until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912.<ref>{{cite book |title=Emblems of Empire: Selections from the Mactaggart Art Collection |first1=John E. |last1=Vollmer |first2=Jacqueline |last2=Simcox |page=154}}</ref> The ] rulers of the Qing dynasty supported Tibetan Buddhism, especially the ] sect, during most of their rule.<ref name="Huntington_et_al">{{cite book |title=The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art |first1=John C. |last1=Huntington |first2=Dina |last2=Bangdel |first3=Robert A. F. |last3=Thurman |page=48}}</ref> The reign of the ] (respected as the ]) was the high mark for this promotion of Tibetan Buddhism in China, with the visit of the ] to Beijing, and the building of temples in the Tibetan style, such as ], the ] and ] (modeled after the potala palace).<ref>{{cite book |last=Weidner |first=Marsha Smith |title=Cultural Intersections in Later Chinese Buddhism |pages=173}}{{full citation needed|date=March 2024}}</ref> | |||

| This period also saw the rise of the ], a 19th-century nonsectarian movement involving the ], ] and ] schools of Tibetan Buddhism, along with some ] scholars.<ref name="Lopez, Donald S. 1998 p. 190">{{cite book |last=Lopez |first=Donald S. |year=1998 |title=Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West |place=Chicago |publisher=University of Chicago Press |page=190}}</ref> Having seen how the ] institutions pushed the other traditions into the corners of Tibet's cultural life, scholars such as ] (1820–1892) and ] (1813–1899) compiled together the teachings of the ], ] and ], including many near-extinct teachings.{{sfnp|Van Schaik|2011|pp=165-169}} Without Khyentse and Kongtrul's collecting and printing of rare works, the suppression of Buddhism by the Communists would have been much more final.{{sfnp|Van Schaik|2011|p=169}} The Rimé movement is responsible for a number of scriptural compilations, such as the '']'' and the '']''.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| During the Qing, Tibetan Buddhism also remained the major religion of the ] (1635–1912), as well as the state religion of the ] (1630–1771), the ] (1634–1758) and the ] (1642–1717).{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| ] photo of ] in 1913, ], Mongolia]] | |||

| In 1912, following the fall of the Qing Dynasty, Tibet became de facto independent under the 13th ] government based in ], maintaining the current territory of what is now called the ].<ref name="Kapstein, Matthew T. 2014, p. 100">{{harvp|Kapstein|2014|p=.}}</ref> | |||

| During the ], the "Chinese Tantric Buddhist Revival Movement" ({{zh|c=密教復興運動}}) took place, and important figures such as ] ({{Lang|zh|能海喇嘛}}, 1886–1967) and Master Fazun ({{Lang|zh|法尊}}, 1902–1980) promoted Tibetan Buddhism and translated Tibetan works into Chinese.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Bianchi |first=Ester |title=The Tantric Rebirth Movement in Modern China, Esoteric Buddhism re-vivified by the Japanese and Tibetan traditions |journal=Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung |volume=57 |number=1 |pages=31–54 |date=2004|doi=10.1556/AOrient.57.2004.1.3 }}</ref> This movement was severely damaged during the ], however.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| After the ], Tibet was annexed by ] in 1950. In 1959 the ] and a great number of clergy and citizenry fled the country, to settle in India and other neighbouring countries. The events of the ] (1966–76) saw religion as one of the main political targets of the Chinese Communist Party, and most of the several thousand temples and monasteries in Tibet were destroyed, with many monks and lamas imprisoned.<ref name="Kapstein 108">{{harvp|Kapstein|2014|p=108}}.</ref> During this time, private religious expression, as well as Tibetan cultural traditions, were suppressed. Much of the Tibetan textual heritage and institutions were destroyed, and monks and nuns were forced to disrobe.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Religions in the Modern World|last1=Cantwell|first1=Cathy|last2=Kawanami|first2=Hiroko|publisher=Routledge|year=2016|isbn=978-0-415-85881-6|edition=3rd|location=New York|pages=91}}</ref> | |||

| Outside of Tibet, however, there has been a renewed interest in Tibetan Buddhism in places such as Nepal and Bhutan.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2023-05-24 |title=Opinion {{!}} Nepal is the birthplace of Buddhism |language=en-US |newspaper=Washington Post |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/nepal-is-the-birthplace-of-buddhism/2017/01/27/cc17a5f2-e2a4-11e6-a419-eefe8eff0835_story.html |access-date=2023-12-02 |issn=0190-8286}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Marks |first=Thomas A. |date=1977 |title=Historical Observations on Buddhism in Bhutan |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/43299858 |journal=The Tibet Journal |volume=2 |issue=2 |pages=74–91 |jstor=43299858 |issn=0970-5368}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Bhutan's Religious History in a Thousand Words {{!}} Mandala Collections - Texts |url=https://texts.mandala.library.virginia.edu/text/bhutans-religious-history-thousand-words |access-date=2023-12-02 |website=texts.mandala.library.virginia.edu}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=A Brief Historical Background of the Religious Institutions of Bhutan |url=https://buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-BH/bh117506.htm |access-date=2023-12-02 |website=buddhism.lib.ntu.edu.tw}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Bhutan |url=https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-report-on-international-religious-freedom/bhutan/ |access-date=2023-12-02 |website=United States Department of State |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| Meanwhile, the spread of Tibetan Buddhism in the Western world was accomplished by many of the refugee Tibetan Lamas who escaped Tibet,<ref name="Kapstein 108" /> such as ] and ] who in 1967 were founders of ] the first Tibetan Buddhist Centre to be established in the West.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.samyeling.org/about/a-brief-history-of-kagyu-samye-ling/|title=A Brief History of Kagyu Samye Ling | SamyeLing.org|website=www.samyeling.org}}</ref> | |||

| After the liberalization policies in China during the 1980s, the religion began to recover with some temples and monasteries being reconstructed.<ref name="Kapstein 110">{{harvp|Kapstein|2014|p=110}}.</ref> Tibetan Buddhism is now an influential religion in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and overseas Chinese communities.<ref name="Kapstein 110"/> However, the Chinese government retains strict control over Tibetan Buddhist Institutions in the ]. Quotas on the number of monks and nuns are maintained, and their activities are closely supervised.{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=238}} | |||

| Within the Tibetan Autonomous Region, violence against Buddhists has been escalating since 2008.<ref>{{cite report|publisher=Freedom House|title=Freedom In The World 2020: Tibet|url=https://freedomhouse.org/country/tibet/freedom-world/2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|website=International Campaign for Tibet|url=https://savetibet.org/why-tibet/self-immolations-by-tibetans/|title=Self-Immolations}}</ref> Widespread reports document the arrests and disappearances<ref>{{cite web|website=Central Tibetan Administration|date=5 October 2019|url=https://tibet.net/monk-from-tibets-amdo-ngaba-arrested-over-social-media-posts-on-tibetan-language/|title=Monk from Tibet's Amdo Ngaba arrested over social media posts on Tibetan Language}}</ref> of nuns and monks, while the Chinese government classifies religious practices as "gang crime".<ref>{{cite web|website=Human Rights Watch|date=14 May 2020|url=https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/14/china-tibet-anti-crime-campaign-silences-dissent|title=China: Tibet Anti-Crime Campaign Silences Dissent}}</ref> Reports include the demolition of monasteries, forced disrobing, forced reeducation, and detentions of nuns and monks, especially those residing at ]'s center, the most highly publicized.<ref>{{cite web|website=Free Tibet|date=8 July 2019|url=https://www.freetibet.org/news-media/na/further-evictions-and-repression-yarchen-gar|title=Further Evictions and Repression at Yarchen Gar}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|first=Craig|last=Lewis|website=The Buddhist Door|date=6 September 2019|url=https://www.buddhistdoor.net/news/new-images-reveal-extent-of-demolitions-at-yarchen-gar-buddhist-monastery|title=New Images Reveal Extent of Demolitions at Yarchen Gar Buddhist Monastery}}</ref> | |||

| ===21st century=== | |||

| ] meeting with U.S. President ] in 2016. Due to his widespread popularity, the Dalai Lama has become the modern international face of Tibetan Buddhism.{{sfnp|Kapstein|2014|p=109}}]] | |||

| Today, Tibetan Buddhism is adhered to widely in the ], ], northern ], ] (on the north-west shore of the Caspian), ] (] and ]), the ] and northeast China. It is the ] of ].<ref>The 2007 U.S. State Department report on religious freedom in Bhutan notes that "Mahayana Buddhism is the state religion..." and that the Bhutanese government supports both the Kagyu and Nyingma sects. </ref> The Indian regions of ] and ], both formerly independent kingdoms, are also home to significant Tibetan Buddhist populations, as are the Indian states of ] (which includes ] and the district of Lahaul-Spiti), ] (the hill stations of ] and ]) and ]. Religious communities, refugee centers and monasteries have also been established in ].{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=240}} | |||

| The 14th Dalai Lama is the leader of the ] which was initially dominated by the Gelug school, however, according to Geoffrey Samuel:<blockquote>The Dharamsala administration under the Dalai Lama has nevertheless managed, over time, to create a relatively inclusive and democratic structure that has received broad support across the Tibetan communities in exile. Senior figures from the three non-Gelukpa Buddhist schools and from the Bonpo have been included in the religious administration, and relations between the different lamas and schools are now on the whole very positive. This is a considerable achievement, since the relations between these groups were often competitive and conflict-ridden in Tibet before 1959, and mutual distrust was initially widespread. The Dalai Lama's government at Dharamsala has also continued under difficult circumstances to argue for a negotiated settlement rather than armed struggle with China.{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=240}}</blockquote> | |||

| ] Buddhist center in ].]] | |||

| In the wake of the ], Tibetan Buddhism has also gained adherents in ] and throughout the world. Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and centers were first established in ] and ] in the 1960s, and most are now supported by non-Tibetan followers of Tibetan lamas. Some of these westerners went on to learn Tibetan, undertake extensive training in the traditional practices and have been recognized as lamas.{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|pp=242–243}} Fully ordained Tibetan Buddhist Monks have also entered Western societies in other ways, such as working academia.<ref> (accessed 11 May 2013)</ref> | |||

| Samuel sees the character of Tibetan Buddhism in the West as | |||

| {{blockquote|...that of a national or international network, generally centred around the teachings of a single individual lama. Among the larger ones are the FPMT, which I have already mentioned, now headed by ] and the child-reincarnation of ]; the New Kadampa, in origin a break-away from the ]; the ], deriving from ]'s organization and now headed by his son; and the networks associated with ] Rinpoche (the Dzogchen Community) and ] (Rigpa).<ref>{{cite book |last=Samuel |first=Geoffrey |title=Tantric Revisionings: New Understandings of Tibetan Buddhism and Indian Religion |pages=303–304}}{{full citation needed|date=March 2024}}</ref>}} | |||

| ==Teachings== | |||

| {{MahayanaBuddhism}} | {{MahayanaBuddhism}} | ||

| Tibetan Buddhism upholds classic Buddhist teachings such as the ] (Tib. ''pakpé denpa shyi''), ] (not-self, ''bdag med''), the ] (''phung po'') ] and ], and ] (''rten cing ’brel bar ’byung ba'').{{sfnp|Powers|2007|pp=65, 71, 75}} They also uphold various other Buddhist doctrines associated with ] Buddhism (''theg pa chen po'') as well as the tantric ] tradition.{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=102}} | |||

| '''Tibetan Buddhism'''<ref>An alternative term, "lamaism", and was used to distinguish Tibetan Buddhism from other buddhism. The term was taken up by western scholars including ], as early as 1822 ({{cite book |last=Lopez |first=Donald S. Jr. |authorlink=Donald S. Lopez, Jr. |title=Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West |year=1999 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |location=Chicago |isbn=0-226-49311-3 |pages=6, 19f }}). Insofar as it implies a discontinuity between Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, the term has been discredited (Conze, 1993).</ref> is the body of ] religious doctrine and institutions characteristic of ], ], ], ], ] and certain regions of the ], including northern ], and ] (particularly in ], ], ], ] in ] and ]). It is the ] of ].<ref>The 2007 U.S. State Department report on religious freedom in Bhutan notes that "Mahayana Buddhism is the state religion..." and that the Bhutanese government supports both the Kagyu and Nyingma sects. </ref> It is also practiced in ] and parts of ] (], ], and ]) and ]. ]s and commentaries are contained in the ] such that ] is a ] of these areas. | |||

| ===Buddhahood and Bodhisattvas=== | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | total_width = 300 | |||

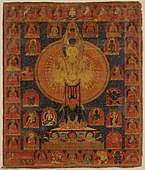

| | image1 = Adi_Buddha_Samantabhadra.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = ], surrounded by numerous peaceful and ]. | |||

| | image2 = MET_DT6050.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = The eleven faced and thousand armed form of the bodhisattva ]. | |||

| }} | |||

| The Mahāyāna goal of spiritual development is to achieve the enlightenment of ] in order to help all other ] attain this state.<ref>Cf. {{harvp|Dhargyey|1978|p=111}}; ], 533f; {{harvp|Tsong-kha-pa|2002|pp=48-9}}.</ref> This motivation is called '']'' (mind of awakening)—an altruistic intention to become enlightened for the sake of all sentient beings.{{sfnp|Thurman|1997|p=291}} '']'' (Tib. ''jangchup semba,'' literally "awakening hero") are revered beings who have conceived the ] to dedicate their lives with ''bodhicitta'' for the sake of all beings.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| Widely revered Bodhisattvas in Tibetan Buddhism include ], ], ], and ]. The most important Buddhas are the ] of the Vajradhatu mandala{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=75}} as well as the ] (first Buddha), called either ] or Samantabhadra.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| Buddhahood is defined as a state free of the obstructions to liberation as well as those to omniscience (''sarvajñana'').<ref>Cf. {{harvp|Dhargyey|1978|pp=64ff}}; {{harvp|Dhargyey|1982|pp=257ff}}; ], 364f; {{harvp|Tsong-kha-pa|2002|pp=183ff}}. The former are the afflictions, negative states of mind, and the ] – desire, anger, and ignorance. The latter are subtle imprints, traces or "stains" of delusion that involves the imagination of inherent existence.</ref> When one is freed from all mental obscurations,<ref>], 152f</ref> one is said to attain a state of continuous bliss mixed with a simultaneous cognition of ],<ref>], 243, 258</ref> the ].{{sfnp|Hopkins|1996|p={{page needed|date=March 2024}}}} In this state, all limitations on one's ability to help other living beings are removed.<ref>{{harvp|Dhargyey|1978|pp=61ff}}; {{harvp|Dhargyey|1982|pp=242–266}}; ], 365</ref> Tibetan Buddhism teaches methods for achieving Buddhahood more quickly (known as the ] path).{{sfnp|Thurman|1997|pp=2–3}} | |||

| It is said that there are countless beings who have attained Buddhahood.<ref>], 252f</ref> Buddhas spontaneously, naturally and continuously perform activities to benefit all sentient beings.<ref>], 367</ref> However it is believed that one's '']'' could limit the ability of the Buddhas to help them. Thus, although Buddhas possess no limitation from their side on their ability to help others, sentient beings continue to experience suffering as a result of the limitations of their own former negative actions.<ref>{{harvp|Dhargyey|1978|p=74}}; {{harvp|Dhargyey|1982|pp=3, 303ff}}; ], 13f, 280f; </ref> | |||

| An important schema which is used in understanding the nature of Buddhahood in Tibetan Buddhism is the '']'' (Three bodies) doctrine.{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=54}} | |||

| === The Bodhisattva path === | |||

| A central schema for spiritual advancement used in Tibetan Buddhism is that of the ] (Skt. ''pañcamārga''; Tib. ''lam nga'') which are:{{sfnp|Powers|2007|pp=93–96}} | |||

| # The path of accumulation – in which one collects wisdom and merit, generates ], cultivates the ] and ]. | |||

| # The path of preparation – Is attained when one reaches the union of calm abiding and higher insight meditations (see below) and one becomes familiar with ]. | |||

| # The path of seeing – one perceives emptiness directly, all thoughts of subject and object are overcome, one becomes an '']''. | |||

| # The path of meditation – one removes subtler traces from one's mind and perfects one's understanding. | |||

| # The path of no more learning – which culminates in Buddhahood. | |||

| The schema of the five paths is often elaborated and merged with the concept of the ] or the bodhisattva levels.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| ===Lamrim=== | |||

| {{Main|Lamrim}} | |||

| ''Lamrim'' ("stages of the path") is a Tibetan Buddhist schema for presenting the stages of spiritual practice leading to ]. In Tibetan Buddhist history there have been many different versions of ''lamrim'', presented by different teachers of the Nyingma, Kagyu and Gelug schools (the Sakya school uses a different system named '']'').<ref>The ] school, too, has a somewhat similar textual form, the '']''.</ref> However, all versions of the ''lamrim'' are elaborations of ]'s 11th-century root text '']'' (''Bodhipathapradīpa'').<ref name="thubten">{{Cite web|url=https://thubtenchodron.org/buddhism/02-lam-rim/|title=Stages of the Path (Lamrim)|website=Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron}}</ref> | |||

| Atisha's ''lamrim'' system generally divides practitioners into those of ''lesser'', ''middling'' and ''superior'' scopes or attitudes: | |||

| *The lesser person is to focus on the preciousness of human birth as well as contemplation of death and impermanence. | |||

| *The middling person is taught to contemplate ], ] (suffering) and the benefits of liberation and refuge. | |||

| *The superior scope is said to encompass the four ]s, the ] vow, the six ] as well as Tantric practices.{{sfnp|Kapstein|2014|pp=52-53}} | |||

| Although ''lamrim'' texts cover much the same subject areas, subjects within them may be arranged in different ways and with different emphasis depending on the school and tradition it belongs to. ] and ] expanded the short root-text of Atiśa into an extensive system to understand the entire Buddhist philosophy. In this way, subjects like ], ], ] and the practice of ] are gradually explained in logical order.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| ===Vajrayāna=== | |||

| ] and ], Tibet, 18th century]] | |||

| Tibetan Buddhism incorporates ] (''] vehicle''), "Secret Mantra" (Skt. ''Guhyamantra'') or Buddhist ], which is espoused in the texts known as the ] (dating from around the 7th century CE onwards).{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=250}} | |||

| ] (Tib. ''rgyud'', "continuum") generally refers to forms of religious practice which emphasize the use of unique ideas, visualizations, mantras, and other practices for inner transformation.{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=250}} The Vajrayana is seen by most Tibetan adherents as the fastest and most powerful vehicle for enlightenment because it contains many skillful means ('']'') and because it takes the effect (] itself, or ]) as the path (and hence is sometimes known as the "effect vehicle", ''phalayana'').{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=250}} | |||

| An important element of Tantric practice are tantric deities and their ]s. These deities come in peaceful (''shiwa'') and ].{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=69}} | |||

| Tantric texts also generally affirm the use of sense pleasures and other ] in Tantric ritual as a path to enlightenment, as opposed to non-Tantric Buddhism which affirms that one must renounce all sense pleasures.<ref name="Kapstein 82">{{harvp|Kapstein|2014|p=82}}.</ref> These practices are based on the theory of transformation which states that negative or sensual mental factors and physical actions can be cultivated and transformed in a ritual setting. As the ] states: | |||

| <blockquote>Those things by which evil men are bound, others turn into means and gain thereby release from the bonds of existence. By passion the world is bound, by passion too it is released, but by heretical Buddhists this practice of reversals is not known.{{sfnp|Snellgrove|1987|pp=125–126}}</blockquote> | |||

| Another element of the Tantras is their use of transgressive practices, such as drinking ] substances such as alcohol or ]. While in many cases these transgressions were interpreted only symbolically, in other cases they are practiced literally.<ref name="Kapstein 83">{{harvp|Kapstein|2014|p=83}}.</ref> | |||

| ===Philosophy=== | |||

| ], at ] (Scotland)]] | |||

| The Indian Buddhist ] ("Middle Way" or "Centrism") philosophy, also called ''Śūnyavāda'' (the emptiness doctrine) is the dominant ] in Tibetan Buddhism. In Madhyamaka, the true nature of reality is referred to as '']'', which is the fact that all phenomena are empty of ] or essence (''svabhava''). Madhyamaka is generally seen as the highest philosophical view by most Tibetan philosophers, but it is interpreted in numerous different ways.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| The other main Mahayana philosophical school, ] has also been very influential in Tibetan Buddhism, but there is more disagreement among the various schools and philosophers regarding its status. While the Gelug school generally sees Yogācāra views as either false or provisional (i.e. only pertaining to conventional truth), philosophers in the other three main schools, such as ] and ], hold that Yogācāra ideas are as important as Madhyamaka views.{{sfnp|Shantarakshita|Mipham|2005|pp=117–122}} | |||

| {{anchor|Study of tenet systems}} <!-- Tibetan Buddhism sidebar ("Teachings" list) links here --> | |||

| In Tibetan Buddhist scholasticism, Buddhist philosophy is traditionally propounded according to a ] of four classical Indian philosophical schools, known as the "four tenets" (Tib. ''drubta shyi'', Sanskrit: ]).{{sfnp|Shantarakshita|Mipham|2005|p=26}} While the classical tenets-system is limited to four tenets (Vaibhāṣika, Sautrāntika, Yogācāra, and Madhyamaka), there are further sub-classifications within these different tenets (see below).{{sfnp|Cornu|2001|p=145, 150}} This classification does not include ], the only surviving of the 18 classical ]. It also does not include other Indian Buddhist schools, such as ] and ].{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| Two tenets belong to the path referred to as the ] ("lesser vehicle") or ] ("the disciples' vehicle"), and are both related to the north Indian ] tradition:{{sfnp|Cornu|2001|p=135}} | |||

| * ] ({{bo|w=bye brag smra ba}}). The primary source for the Vaibhāṣika in Tibetan Buddhism is the '']'' of ] and its commentaries. This ] system affirms an atomistic view of reality which states ultimate reality is made up of a series of impermanent phenomena called '']''. It also defends ] regarding the ], as well the view that perception directly experiences external objects.<ref name="Kapstein 67">{{harvp|Kapstein|2014|p=67}}.</ref> | |||

| * ] ({{bo|w=mdo sde pa}}). The main sources for this view is the ''Abhidharmakośa'', as well as the work of ] and ]. As opposed to Vaibhāṣika, this view holds that only the present moment exists (]), as well as the view that we do not directly perceive the external world only the mental images caused by objects and our sense faculties.<ref name="Kapstein 67"/> | |||

| The other two tenets are the two major Indian ] philosophies: | |||

| * ], also called ''Vijñānavāda'' (the doctrine of consciousness) and ''Cittamātra'' ("Mind-Only", {{bo|w=sems-tsam-pa}}). Yogacārins base their views on texts from ], ] and ]. Yogacara is often interpreted as a form of ] due to its main doctrine, the view that only ideas or mental images exist (''vijñapti-mātra'').<ref name="Kapstein 67"/> Some Tibetan philosophers interpret Yogācāra as the view that the mind (''citta'') exists in an ultimate sense, because of this, it is often seen as inferior to Madhyamaka. However, other Tibetan thinkers deny that the Indian Yogacāra masters held the view of the ultimate existence of the mind, and thus, they place Yogācāra on a level comparable to Madhyamaka. This perspective is common in the Nyingma school, as well as in the work of the ], the ] and ].{{sfnp|Shantarakshita|Mipham|2005|pp=27–28}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Asanga |last2=Brunnholzl |first2=Karl |year=2019 |title=A Compendium of the Mahayana: Asanga's Mahayanasamgraha and Its Indian and Tibetan Commentaries |volume=I |chapter=Preface |publisher=Shambhala Publications}}</ref> | |||

| * ] ({{bo|w=dbu-ma-pa}}) – The philosophy of ] and ], which affirms that everything is empty of essence ('']'') and is ultimately beyond concepts.<ref name="Kapstein 67"/> There are various further classifications, sub-schools and interpretations of Madhymaka in Tibetan Buddhism and numerous debates about various key disagreements remain a part of Tibetan Buddhist scholasticism today. One of the key debates is that between the ].{{sfnp|Cornu|2001|p=146-147}} Another major disagreement is the debate on the ] method and the ] method.{{sfnp|Cornu|2001|p=138}} There are further disagreements regarding just how useful an intellectual understanding of emptiness can be and whether emptiness should only be described as an absolute negation (the view of ]).{{sfnp|Cornu|2001|p=145}}], Tibet, 2013. Debate is seen as an important practice in Tibetan Buddhist education. ]] | |||

| The tenet systems are used in monasteries and colleges to teach Buddhist philosophy in a systematic and progressive fashion, each philosophical view being seen as more subtle than its predecessor. Therefore, the four tenets can be seen as a gradual path from a rather easy-to-grasp, "realistic" philosophical point of view, to more and more complex and subtle views on the ultimate nature of reality, culminating in the philosophy of the Mādhyamikas, which is widely believed to present the most sophisticated point of view.<ref>{{harvp|Sopa|Hopkins|1977|pp=67–69}}; {{harvp|Hopkins|1996|p={{page needed|date=March 2024}}}}.</ref> Non-Tibetan scholars point out that historically, Madhyamaka predates Yogacara, however.<ref>Cf. {{harvp|Conze|1993}}.</ref> | |||

| ==Texts and study== | |||

| {{Main|Tibetan Buddhist canon}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Study of major Buddhist Indian texts is central to the monastic curriculum in all four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. ] of classic texts as well as other ritual texts is expected as part of traditional monastic education. Another important part of higher religious education is the practice of formalized debate.{{sfnp|Kapstein|2014|p=63}} | |||

| The canon was mostly finalized in the 13th century, and divided into two parts, the ] (containing sutras and tantras) and the ] (containing ''shastras'' and commentaries). The ] school also maintains a separate collection of texts called the ], assembled by Ratna Lingpa in the 15th century and revised by ].{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|pp=19–20}} | |||

| Among Tibetans, the main language of study is ], however, the Tibetan Buddhist canon was also translated into other languages, such as ] and ].{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| During the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, many texts from the Tibetan canon were also translated into Chinese.<ref>{{cite book |editor-last=Orzech |editor-first=Charles D. |year=2011 |title=Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia |publisher=Brill |page=540}}</ref> | |||

| Numerous texts have also recently been translated into Western languages by Western academics and Buddhist practitioners.{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=21}} | |||

| === Sutras === | |||

| ]s from an old woodblock copy of the Tibetan ]. He is seated at a special sutra stool, wearing the traditional woolen Ladakhi hat and robe, allowed by Vinaya for extremely cold conditions.]] | |||

| Among the most widely studied sutras in Tibetan Buddhism are ] such as the ''Perfection of Wisdom'' or ] sutras,{{sfnp|Powers|2007|pp=103–104}} and others such as the ''],'' and the ''].''<ref>{{cite book |first1=Luis O. |last1=Gomez |first2=Jonathan A. |last2=Silk |title=Studies in the Literature of the Great Vehicle: Three Mahayana Buddhist Texts |place=Ann Arbor |publisher=University of Michigan |series=Michigan studies in Buddhist literature |date=1989 |page=viii |isbn=9780891480549 |oclc=20159406}}</ref> | |||

| According to ], the two authoritative systems of Mahayana Philosophy (viz. that of Asaṅga – Yogacara and that of Nāgārjuna – Madhyamaka) are based on specific Mahāyāna sūtras: the ''Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra'' and the ] respectively. Furthermore, according to ], for Tsongkhapa, "at the heart of these two hermeneutical systems lies their interpretations of the Perfection of Wisdom sūtras, the archetypal example being the ''Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines''."<ref>{{cite book |author=Thupten Jinpa |year=2019 |title=Tsongkhapa A Buddha in the Land of Snows |series=Lives of the Masters |pages=219–220 |publisher=Shambhala}}</ref> | |||

| ===Treatises of the Indian masters=== | |||

| The study of Indian Buddhist treatises called '']s'' is central to Tibetan Buddhist ]. Some of the most important works are those by the six great Indian Mahayana authors which are known as the Six Ornaments and Two Supreme Ones (Tib. ''gyen druk chok nyi'', Wyl. ''rgyan drug mchog gnyis''), the six being: Nagarjuna, Aryadeva, Asanga, Vasubandhu, Dignaga, and Dharmakirti and the two being: Gunaprabha and Shakyaprabha (or Nagarjuna and Asanga depending on the tradition).{{sfnp|Ringu Tulku|2006|loc=ch. 3}} | |||

| Since the late 11th century, traditional Tibetan monastic colleges generally organized the exoteric study of Buddhism into "five great textual traditions" (''zhungchen-nga'').{{sfnp|Kapstein|2014|p=64}} | |||

| # ] | |||

| #* ]'s '']'' | |||

| #* ]'s '']'' | |||

| # ] | |||

| #* '']'' | |||

| #* ]'s '']'' | |||

| # ] | |||

| #* ]'s '']'' | |||

| #* ]'s ''Four Hundred Verses'' (''Catuhsataka'') | |||

| #* ]'s '']'' | |||

| #* ]'s '']'' | |||

| #* ]'s '']'' | |||

| # ] | |||

| #* ]'s '']'' | |||

| #* ]'s '']'' | |||

| # ] | |||

| #*Gunaprabha's ''Vinayamula Sutra'' | |||

| ===Other important texts=== | |||

| Also of great importance are the "]" including the influential '']'', a compendium of the ], and the '']'', a text on the Mahayana path from the ] perspective, which are often attributed to ]. Practiced focused texts such as the ] and ]'s '']'' are the major sources for meditation.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| While the Indian texts are often central, original material by key Tibetan scholars is also widely studied and collected into editions called ''sungbum''.{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=20}} The commentaries and interpretations that are used to shed light on these texts differ according to tradition. The Gelug school for example, use the works of ], while other schools may use the more recent work of ] scholars like ] and ].{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| The ] has spread Tibetan Buddhism to many ], where the tradition has gained popularity.<ref> -- The 2007 Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life Survey estimates that although Tibetan Buddhism adherents are less than 0.3 percent of the population, Buddhism has had a 0.5 net increase in reported adherents.</ref> Among its prominent exponents is the ] of Tibet. The number of its adherents is estimated to be between ten and twenty million.<ref>Adherents.com estimates twenty million for </ref> | |||

| A corpus of extra-canonical scripture, the ] (''terma'') literature is acknowledged by ] practitioners, but the bulk of the canon that is not commentary was translated from Indian sources. True to its roots in the ''Pāla'' system of North India, however, Tibetan Buddhism carries on a tradition of eclectic accumulation and systematisation of diverse Buddhist elements, and pursues their synthesis. Prominent among these achievements have been the ] and ] literature, both stemming from teachings by the Indian scholar ].{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| ==Origins== | |||

| ===Tantric literature=== | |||

| {{See also|History of Tibetan Buddhism}} | |||

| {{Main|Tantras (Buddhism)|Classes of Tantra in Tibetan Buddhism}} | |||

| In Tibetan Buddhism, the Buddhist Tantras are divided into four or six categories, with several sub-categories for the highest Tantras. | |||

| In the Nyingma, the division is into ''Outer Tantras'' (], ], ]); and ''Inner Tantras'' (], ], ]/]), which correspond to the "Anuttarayoga-tantra".<ref>"Yoginitantras are in the secondary literature often called Anuttarayoga. But this is based on a mistaken back translation of the Tibetan translation (rnal byor bla med kyi rgyud) of what appears in Sanskrit texts only as Yogānuttara or Yoganiruttara (cf. SANDERSON 1994: 97–98, fn.1)." | |||

| Tibetan Buddhism derives from the latest stage of north Indian Buddhism.<ref>Conze, 1993</ref> | |||

| Isabelle Onians, "Tantric Buddhist Apologetics, or Antinomianism as a Norm," D.Phil. dissertation, Oxford, Trinity Term 2001. pg 70 | |||

| ==Buddhahood== | |||

| </ref> For the Nyingma school, important tantras include the ], the ''],''{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=32}} the '']'' and the 17 ]. | |||

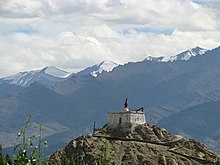

| ]; a ] in ], ]. Stupas symbolize the mind of a Buddha.]] | |||

| Tibetan Buddhism comprises the teachings of the three ] of ]: the ], '']'', and '']''. The Mahāyāna goal of spiritual development is to achieve the enlightenment of ] in order to most efficiently help all other ] attain this state.<ref>Cf. Dhargyey (1978), 111; ], 533f; Tsong-kha-pa II: 48-9</ref> The motivation in it is the '']'' mind of enlightenment — an altruistic intention to become enlightened for the sake of all sentient beings.<ref>Thurman, Robert (1997). ''Essential Tibetan Buddhism''. Castle Books: 291</ref> '']'' are revered beings who have conceived the ] to dedicate their lives with ''bodhicitta'' for the sake of all beings. Tibetan Buddhism teaches methods for achieving buddhahood more quickly by including the Vajrayāna path in Mahāyāna.<ref>Thurman, Robert (1997): 2-3</ref> | |||

| In the Sarma schools, the division is:{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=78}} | |||

| Buddhahood is defined as a state free of the obstructions to liberation as well as those to omniscience.<ref>Cf. Dhargyey (1978), 64f; Dhargyey (1982), 257f, etc; ], 364f; Tsong-kha-pa II: 183f. The former are the afflictions, negative states of mind, and the ] – desire, anger, and ignorance. The latter are subtle imprints, traces or "stains" of delusion that involves the imagination of inherent existence.</ref> When one is freed from all mental obscurations,<ref>], 152f</ref> one is said to attain a state of continuous bliss mixed with a simultaneous cognition of ],<ref>], 243, 258</ref> the ].<ref name="Hopkins 1996">Hopkins (1996)</ref> In this state, all limitations on one's ability to help other living beings are removed.<ref>Dhargyey (1978), 61f; Dhargyey (1982), 242-266; ], 365</ref> | |||

| * '''''Kriya-yoga''''' – These have an emphasis on purification and ritual acts and include texts like the ]. | |||

| It is said that there are countless beings who have attained buddhahood.<ref>], 252f</ref> Buddhas spontaneously, naturally and continuously perform activities to benefit all sentient beings.<ref>], 367</ref> However it is believed that one's '']'' could limit the ability of the Buddhas to help them. Thus, although Buddhas possess no limitation from their side on their ability to help others, sentient beings continue to experience suffering as a result of the limitations of their own former negative actions.<ref>Dhargyey (1978), 74; Dhargyey (1982), 3, 303f; ], 13f, 280f; </ref> | |||

| * '''''Charya-yoga''''' – Contain "a balance between external activities and internal practices", mainly referring to the ''].'' | |||

| * '''''Yoga-tantra''''', is mainly concerned with internal yogic techniques and includes the ''].'' | |||

| * ], contains more advanced techniques such as ] practices and is subdivided into: | |||

| **Father tantras, which emphasize illusory body and ] practices and includes the ] and ''] Tantra''. | |||

| **Mother tantras, which emphasize the development stage and ] and includes the '']'' and ''].'' | |||

| **Non-dual tantras, which balance the above elements, and mainly refers to the ] | |||

| The root tantras themselves are almost unintelligible without the various Indian and Tibetan commentaries, therefore, they are never studied without the use of the tantric commentarial apparatus.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| ==General methods of practice== | |||

| ]s from an old woodblock copy of the Tibetan ]]] | |||

| ===Transmission and realization=== | ===Transmission and realization=== | ||

| There is a long history of ] of teachings in Tibetan Buddhism. Oral transmissions by ] holders traditionally can take place in small groups or mass gatherings of listeners and may last for seconds (in the case of a ], for example) or months (as in the case of a section of the ]). |

There is a long history of ] of teachings in Tibetan Buddhism. Oral transmissions by ] holders traditionally can take place in small groups or mass gatherings of listeners and may last for seconds (in the case of a ], for example) or months (as in the case of a section of the ]). It is held that a transmission can even occur without actually hearing, as in ]'s visions of ].{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | ||

| An emphasis on oral transmission as more important than the printed word derives from the earliest period of Indian Buddhism, when it allowed teachings to be kept from those who should not hear them. |

An emphasis on oral transmission as more important than the printed word derives from the earliest period of Indian Buddhism, when it allowed teachings to be kept from those who should not hear them.{{sfnp|Conze|1993|p=26}} Hearing a teaching (transmission) readies the hearer for realization based on it. The person from whom one hears the teaching should have heard it as one link in a succession of listeners going back to the original speaker: the Buddha in the case of a '']'' or the author in the case of a book. Then the hearing constitutes an authentic lineage of transmission. Authenticity of the oral lineage is a prerequisite for realization, hence the importance of lineages.{{Citation needed|date=December 2023}} | ||

| == Practices == | |||

| ===Analytic meditation and fixation meditation=== | |||

| {{See also|Tantra techniques (Vajrayana)}}In Tibetan Buddhism, practices are generally classified as either Sutra (or ''Pāramitāyāna'') or Tantra (''Vajrayāna or Mantrayāna''), though exactly what constitutes each category and what is included and excluded in each is a matter of debate and differs among the various lineages. According to Tsongkhapa for example, what separates Tantra from Sutra is the practice of Deity yoga.{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=271}} Furthermore, the adherents of the Nyingma school consider Dzogchen to be a separate and independent vehicle, which transcends both sutra and tantra.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Germano |first=David |year=1994 |title=Architecture and Absence in the Secret Tantric History of the Great Perfection (rdzogs chen) |journal=JIABS |volume=17 |number=2}}</ref> | |||

| Spontaneous realization on the basis of ] is possible but rare. Normally an intermediate step is needed in the form of ], i.e., thinking about what one has heard. As part of this process, entertaining doubts and engaging in internal debate over them is encouraged in some traditions.<ref>Cf.], 66, 212f</ref> | |||

| While it is generally held that the practices of Vajrayāna are not included in Sutrayāna, all Sutrayāna practices are common to Vajrayāna practice. Traditionally, Vajrayāna is held to be a more powerful and effective path, but potentially more difficult and dangerous and thus they should only be undertaken by the advanced who have established a solid basis in other practices.{{sfnp|Samuel|2012|p=50}} | |||

| Analytic meditation is just one of two general methods of ]. When it achieves the quality of realization, one is encouraged to switch to "focused" or "fixation" meditation. In this the mind is stabilized on that realization for periods long enough to gradually habituate it to it. | |||

| === Pāramitā === | |||

| A person's capacity for analytic meditation can be trained with logic. The capacity for successful focused meditation can be trained through ]. A meditation routine may involve alternating sessions of analytic meditation to achieve deeper levels of realization, and focused meditation to consolidate them.<ref name="Hopkins 1996"/> The deepest level of realization is Buddhahood itself. | |||

| {{Main|Pāramitā}} | |||

| The ] (perfections, transcendent virtues) is a key set of virtues which constitute the major practices of a bodhisattva in non-tantric Mahayana. They are: | |||

| # ''] pāramitā'': generosity, giving (Tibetan: སབྱིན་པ ''sbyin-pa'') | |||

| ===Devotion to a guru=== | |||

| # ''] pāramitā:'' virtue, morality, discipline, proper conduct (ཚུལ་ཁྲིམས ''tshul-khrims'') | |||

| {{see also|Guru#Guru_in_Buddhism|label 1=Guru in Buddhism}} | |||

| # ''] pāramitā'': patience, tolerance, forbearance, acceptance, endurance (བཟོད་པ ''bzod-pa'') | |||

| As in other Buddhist traditions, an attitude of reverence for the teacher, or guru, is also highly prized.<ref>''Lama'' is the literal Tibetan translation of the Sanskrit ''guru''. For a traditional perspective on devotion to the guru, see Tsong-ka-pa I, 77-87. For a current perspective on the guru-disciple relationship in Tibetan Buddhism, see </ref> At the beginning of a public teaching, a '']'' will do ]s to the throne on which he will teach due to its symbolism, or to an image of the Buddha behind that throne, then students will do prostrations to the lama after he is seated. Merit accrues when one's interactions with the teacher are imbued with such reverence in the form of guru devotion, a code of practices governing them that derives from Indian sources.<ref>notably, ''Gurupancasika'', Tib.: ''Lama Ngachupa'', Wylie: ''bla-ma lnga-bcu-pa'', “Fifty Verses of Guru-Devotion” by ]</ref> By such things as avoiding disturbance to the peace of mind of one's teacher, and wholeheartedly following his prescriptions, much merit accrues and this can significantly help improve one's practice. | |||

| # ''] pāramitā'': energy, diligence, vigor, effort (བརྩོན་འགྲུས ''brtson-’grus'') | |||

| # ''] pāramitā'': one-pointed concentration, meditation, contemplation (བསམ་གཏན ''bsam-gtan'') | |||

| # ''] pāramitā'': wisdom, knowledge (ཤེས་རབ ''shes-rab'') | |||

| The practice of ''dāna'' (giving) while traditionally referring to offerings of food to the monastics can also refer to the ritual offering of bowls of water, incense, butter lamps and flowers to the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas on a shrine or household altar.{{sfnp|Kapstein|2014|pp=45-46}} Similar offerings are also given to other beings such as hungry ghosts, ], protector deities, and local divinities. | |||

| There is a general sense in which any Tibetan Buddhist teacher is called a ''lama''. A student may have taken teachings from many authorities and revere them all as ''lamas'' in this general sense. However, he will typically have one held in special esteem as his own root guru and is encouraged to view the other teachers who are less dear to him, however more exalted their status, as embodied in and subsumed by the root guru.<ref>Indian tradition (Cf. ''Saddharmapundarika Sutra'' II, 124) encourages the student to view the guru as representative of the Buddha himself.</ref> Often the teacher the student sees as root guru is simply the one who first introduced him to Buddhism, but a student may also change his personal view of which particular teacher is his root guru any number of times. | |||

| Like other forms of Mahayana Buddhism, the practice of the ] and ]s is part of Tibetan Buddhist moral (''sila'') practice. In addition to these, there are also numerous sets of Tantric vows, termed ], which are given as part of Tantric initiations. | |||

| ===Skepticism=== | |||

| ] is an important aspect of Tibetan Buddhism, an attitude of critical skepticism is encouraged to promote abilities in analytic meditation. In favor of skepticism towards Buddhist doctrines in general, Tibetans are fond of quoting sutra to the effect that one should test the Buddha's words as one would the quality of gold.<ref>"Do not accept my ] merely out of respect for me, but analyze and check it the way a goldsmith analyzes gold, by rubbing, cutting and melting it." (''Ghanavyuhasutra''; ''sTug-po bkod-pa'i mdo''); A Sutra Spread Out in a Dense Array, as quoted in translation in On the same need for skepticism in the ] tradition of Theravada Buddhism, cf. Nyanaponika Thera (1965), 83. Further on skepticism in Buddhism generally, see the article, ].</ref> | |||

| Compassion ('']'') practices are also particularly important in Tibetan Buddhism. One of the foremost authoritative texts on the Bodhisattva path is the '']'' by ]. In the eighth section entitled ''Meditative Concentration'', Shantideva describes meditation on Karunā as thus: | |||

| The opposing principles of skepticism and guru devotion are reconciled with the Tibetan injunction to scrutinize a prospective guru thoroughly before finally adopting him as such without reservation. A Buddhist may study with a lama for decades before finally accepting him as his own guru. | |||

| {{blockquote|Strive at first to meditate upon the sameness of yourself and others. In joy and sorrow all are equal; Thus be guardian of all, as of yourself. The hand and other limbs are many and distinct, But all are one—the body to kept and guarded. Likewise, different beings, in their joys and sorrows, are, like me, all one in wanting happiness. This pain of mine does not afflict or cause discomfort to another's body, and yet this pain is hard for me to bear because I cling and take it for my own. And other beings' pain I do not feel, and yet, because I take them for myself, their suffering is mine and therefore hard to bear. And therefore I'll dispel the pain of others, for it is simply pain, just like my own. And others I will aid and benefit, for they are living beings, like my body. Since I and other beings both, in wanting happiness, are equal and alike, what difference is there to distinguish us, that I should strive to have my bliss alone?"<ref>{{cite book |title=The Way of the Bodhisattva |author=Shantideva |publisher=Shambhala Publications |pages=122–123}}</ref>}} | |||

| A popular compassion meditation in Tibetan Buddhism is '']'' (sending and taking love and suffering respectively). Practices associated with ] (Avalokiteshvara), also tend to focus on compassion. | |||

| === |

=== Samatha and Vipaśyanā === | ||

| ] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The ] defines meditation (''bsgom pa'') as "familiarization of the mind with an object of meditation."{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=81}} Traditionally, Tibetan Buddhism follows the two main approaches to ] or mental cultivation ('']'') taught in all forms of Buddhism, ] (Tib. ''Shine'') and ] (''lhaktong''). | |||

| The practice of ] (calm abiding) is one of focusing one's mind on a single object such as a Buddha figure or the breath. Through repeated practice one's mind gradually becomes more stable, calm and happy. It is defined by ] as "fixing the mind upon any object so as to maintain it without distraction...focusing the mind on an object and maintaining it in that state until finally it is channeled into one stream of attention and evenness."{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=86}} The ] is the main progressive framework used for śamatha in Tibetan Buddhism.{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=88}} | |||

| Vajrayāna is believed by Tibetan Buddhists to be the fastest method for attaining Buddhahood but for unqualified practitioners it can be dangerous.<ref>Pabonka, p.649</ref> To engage in it one must receive an appropriate initiation (also known as an "empowerment") from a lama who is fully qualified to give it. From the time one has resolved to accept such an initiation, the utmost sustained effort in guru devotion is essential. | |||

| Once a meditator has reached the ninth level of this schema they achieve what is termed "pliancy" (Tib. ''shin tu sbyangs pa'', Skt. '']''), defined as "a serviceability of mind and body such that the mind can be set on a virtuous object of observation as long as one likes; it has the function of removing all obstructions." This is also said to be very joyful and blissful for the body and the mind.{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=90}} | |||

| The aim of ] (''ngöndro'') is to start the student on the correct path for such higher teachings.<ref>Kalu Rinpoche (1986), ''The Gem Ornament of Manifold Instructions''. Snow Lion, p. 21.</ref> Just as Sutrayāna preceded Vajrayāna historically in India, so sutra practices constitute those that are preliminary to tantric ones. Preliminary practices include all ''Sutrayāna'' activities that yield merit like hearing teachings, prostrations, offerings, prayers and acts of kindness and compassion, but chief among the preliminary practices are realizations through meditation on the three principle stages of the path: renunciation, the altruistic ] wish to attain enlightenment and the wisdom realizing emptiness. For a person without the basis of these three in particular to practice Vajrayāna can be like a small child trying to ride an unbroken horse.<ref>], 649</ref> | |||

| The other form of Buddhist meditation is ] (clear seeing, higher insight), which in Tibetan Buddhism is generally practiced after having attained proficiency in ].{{sfnp|Powers|2007|p=91}} This is generally seen as having two aspects, one of which is ], which is based on contemplating and thinking rationally about ideas and concepts. As part of this process, entertaining doubts and engaging in internal debate over them is encouraged in some traditions.{{sfnp|Rinpoche|Rinpoche|2006|p=66, 212f}} The other type of ] is a non-analytical, "simple" yogic style called ''trömeh'' in Tibetan, which means "without complication".<ref>{{cite book |title=The Practice of Tranquillity & Insight: A Guide to Tibetan Buddhist Meditation |author=Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche |publisher=Shambhala Publications |year=1994 |isbn=0-87773-943-9 |pages=91–93}}</ref> | |||

| While the practices of Vajrayāna are not known in Sutrayāna, all Sutrayāna practices are common to Vajrayāna. Without training in the preliminary practices, the ubiquity of allusions to them in Vajrayāna is meaningless and even successful Vajrayāna initiation becomes impossible. | |||

| A meditation routine may involve alternating sessions of vipaśyanā to achieve deeper levels of realization, and samatha to consolidate them.{{sfnp|Hopkins|1996|p={{page needed|date=March 2024}}}} | |||

| The merit acquired in the preliminary practices facilitates progress in Vajrayāna. While many Buddhists may spend a lifetime exclusively on sutra practices, however, an amalgam of the two to some degree is common. For example, in order to train in ], one might use a tantric visualisation as the meditation object. | |||

| === Preliminary practices === | |||

| {{see also|Ngöndro}} | |||

| ].]] | |||