| Revision as of 09:54, 20 July 2006 editLossIsNotMore (talk | contribs)894 edits →Hobbyists, conversions, and racing: wfy← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:24, 30 December 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,414,655 edits Altered title. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Headbomb | Linked from Misplaced Pages:WikiProject_Academic_Journals/Journals_cited_by_Wikipedia/Sandbox | #UCB_webform_linked 770/1522 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Car propelled by an electric motor using energy stored in batteries}} | |||

| ] is powered by twenty-four 12 volt batteries, with an operational cost equivalent of over 165 miles per gallon.]] | |||

| {{About|electric automobiles|all types of electric transportation|Electric vehicle}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2020}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=December 2024}} | |||

| A '''battery electric vehicle''' (BEV) is an ] storing chemical ] in ] ] to power one or more ]s. | |||

| <!-- The following arrangement of pictures has been chosen because it uniquely typifies ELECTRIC cars and the models chosen are among the world's best selling electric cars. Quality pictures of such vehicles are hard to tell apart from pictures of non-electric cars. --> | |||

| BEVs were among the earliest ]s, and are more ] than common ] (ICE) vehicles. They produce no ] while being driven, and almost none at all if charged from most forms of ]. Many are capable of ] performance exceeding that of conventional ] powered vehicles. New models can travel hundreds of miles on a charge, even after 100,000 miles of battery use. BEVs reduce dependence on ], mitigate ], are quieter than internal combustion vehicles, and do not produce noxious fumes. While limited travel distance between battery recharging, charging time, and battery lifetime have been drawbacks, new battery and charging technologies have substantially improved in these areas. | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | header = Modern all-electric cars | |||

| | header_align = center | |||

| | width = 225 | |||

| | caption_align = center | |||

| | image1 = IBMTorontoSoftwareLabEVChargers4.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = ] | |||

| | image2 = Nissan Leaf 2 (45992539055).jpg | |||

| | caption2 = ] | |||

| | image3 = Hyundai Ioniq 5 IMG 4854.jpg | |||

| | caption3 = ] | |||

| | image4 = BMW i3 AMS 12 2016 0372.jpg | |||

| | caption4 = ] | |||

| | total_width = | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Sustainable energy}} | |||

| An '''electric car''' or '''electric vehicle''' ('''EV''') is a ] that is propelled by an ] ], using ] as the primary source of ]. The term normally refers to a ], typically a ] (BEV), which only uses energy stored in ], but broadly may also include ] (PHEV), ] electric vehicle (REEV) and ] (FCEV), which can convert electric power from other ]s via a ] or a ]. | |||

| Some models are still in limited production, but the most popular BEVs have been withdrawn and most of those have been destroyed by their manufacturers. A handful of future production models have been announced, although many more have been prototyped. In the US, the major domestic automobile manufacturers have been accused of deliberately sabotaging their electric vehicle efforts. | |||

| Compared to conventional ] (ICE) vehicles, electric cars are quieter, more responsive, have superior ] and no ], as well as a lower overall ] from manufacturing to end of life<ref>{{cite web|url= https://www.energy.gov/eere/electricvehicles/reducing-pollution-electric-vehicles|title=Reducing Pollution with Electric Vehicles|website=www.energy.gov|language=en|access-date=2018-05-12|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20180512115459/https://www.energy.gov/eere/electricvehicles/reducing-pollution-electric-vehicles|archive-date=12 May 2018|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=US EPA |first=OAR |date=2021-05-14 |title=Electric Vehicle Myths |url=https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/electric-vehicle-myths |access-date=2024-06-09 |website=www.epa.gov |language=en}}</ref> (even when a ] supplying the electricity might add to its emissions). Due to the superior efficiency of electric motors, electric cars also generate less ], thus reducing the need for ]s that are often large, complicated and maintenance-prone in ICE vehicles. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] typically needs to be plugged into a ] ] for ] in order to maximize the ]. Recharging an electric car can be done at different kinds of ]s; these charging stations can be installed in ]s, ]s and ]s.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.carbuyer.co.uk/tips-and-advice/155186/how-to-charge-an-electric-car|title=How to charge an electric car|work=Carbuyer|access-date=2018-04-22|language=en|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20180423102022/http://www.carbuyer.co.uk/tips-and-advice/155186/how-to-charge-an-electric-car|archive-date=23 April 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> There is also ] in, as well as deployment of, other technologies such as ] and ]. As the ] (especially ]s) is still in its infancy, ] and ] are frequent psychological obstacles during ]s against electric cars. | |||

| BEVs were among the earliest automobiles. Between 1832 and 1839 (the exact year is uncertain), ] of ] invented the first crude electric carriage. A small-scale electric car was designed by Professor ] of Groningen, Holland, and built by his assistant ] in 1835. Frenchmen ], in 1865, and ] in 1881 improved the storage battery, paving the way for electric vehicles to flourish. France and Great Britain were the first nations to support their widespread development. <ref>Bellis, M. (2006) "The History of Electric Vehicles: The Early Years" ''About.com'' accessed on 6 July 2006</ref> | |||

| Worldwide, 14 million ]s were sold in 2023, 18% of new car sales, up from 14% in 2022.<ref name=":12">{{Cite web |title=Trends in electric cars – Global EV Outlook 2024 – Analysis |url=https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/trends-in-electric-cars |access-date=2024-12-01 |website=IEA |language=en-GB}}</ref> Many countries have established ], tax credits, subsidies, and other non-monetary incentives while several countries have legislated to ],<ref>{{cite web|date=2020-09-23|title=Governor Newsom Announces California Will Phase Out Gasoline-Powered Cars & Drastically Reduce Demand for Fossil Fuel in California's Fight Against Climate Change|url=https://www.gov.ca.gov/2020/09/23/governor-newsom-announces-california-will-phase-out-gasoline-powered-cars-drastically-reduce-demand-for-fossil-fuel-in-californias-fight-against-climate-change/|access-date=2020-09-26|website=California Governor|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Groom|first=David Shepardson, Nichola|date=2020-09-29|title=U.S. EPA chief challenges California effort to mandate zero emission vehicles in 2035|language=en|work=Reuters|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/autos-california-emissions-idUSKBN26K05X|access-date=2020-09-29}}</ref> to reduce ] and ].<ref name="Thunberg">{{cite book|first1=Greta|first2= Jillian|first3=Christian|last1=Thunberg|last2=Anable|last3=Brand|title= ]|chapter=Is the Future Electric?|date=2022|isbn=978-0593492307|pages= 271–275|publisher= Penguin}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Cite news|date=2021-07-14|title=EU proposes effective ban for new fossil-fuel cars from 2035|url=https://www.reuters.com/business/retail-consumer/eu-proposes-effective-ban-new-fossil-fuel-car-sales-2035-2021-07-14/|access-date=2021-08-06|publisher=Reuters}}</ref> EVs are expected to account for over one-fifth of global car sales in 2024.<ref name=":12" /> | |||

| Before the preeminence of powerful but polluting ], electric automobiles held many speed and distance records around the turn of the century. Most notable was perhaps breaking of the 100 kilometers per hour speed barrier, by ] on April 29, 1899 in his rocket-like EV named ''La Jamais Contente''. It reached a top speed of 105.88 kilometers per hour (65.79 mph) | |||

| ] currently has the ], with cumulative sales of 5.5 million units through December 2020,<ref>{{Cite web|title=How China put nearly 5 million new energy vehicles on the road in one decade {{!}} International Council on Clean Transportation|url=https://theicct.org/blog/staff/china-new-energy-vehicles-jan2021|access-date=2021-10-30|website=theicct.org|date=28 January 2021 }}</ref>{{Update inline|date=December 2024|reason=Too far in the past.}} although these figures also include heavy-duty ]s such as ]es, ]s and ]s, and only accounts for vehicles manufactured in China.<ref name=China2016>{{cite web | url=http://www.d1ev.com/48462.html | title=中汽协:2016年新能源汽车产销量均超50万辆,同比增速约50% |language=Chinese |trans-title=China Auto Association: 2016 new energy vehicle production and sales were over 500,000, an increase of about 50% |last=Liu |first=Wanxiang |publisher=D1EV.com| date=2017-01-12 |accessdate=2017-01-12}} ''Chinese sales of new energy vehicles in 2016 totaled 507,000, consisting of 409,000 all-electric vehicles and 98,000 plug-in hybrid vehicles.''</ref><ref name=China2017>{{cite web | url=https://www.autonews.com/china/electrified-vehicle-sales-surge-53-2017 | title=Electrified vehicle sales surge 53% in 2017 |author=Automotive News China |publisher=Automotive News China | date=2018-01-16 |accessdate=2020-05-22}} ''Chinese sales of domestically-built new energy vehicles in 2017 totaled 777,000, consisting of 652,000 all-electric vehicles and 125,000 plug-in hybrid vehicles. Sales of domestically-produced new energy passenger vehicles totaled 579,000 units, consisting of 468,000 all-electric cars and 111,000 plug-in hybrids. Only domestically built all-electric vehicles, plug-in hybrids and fuel cell vehicles qualify for government subsidies in China.''</ref><ref name=China2018>{{cite web | url=https://www.d1ev.com/news/shuju/85937 | title=中汽协:2018年新能源汽车产销均超125万辆,同比增长60% |language=Chinese |trans-title=China Automobile Association: In 2018, the production and sales of new energy vehicles exceeded 1.25 million units, a year-on-year increase of 60% |publisher=D1EV.com| date=2019-01-14 |accessdate=2019-01-15}} ''Chinese sales of new energy vehicles in 2018 totaled 1.256 million, consisting of 984,000 all-electric vehicles and 271,000 plug-in hybrid vehicles.''</ref><ref name="NEVsChina2019">{{cite web |url=https://insideevs.com/news/396291/chinese-nevs-market-slightly-declined-2019/ |title=Chinese NEVs Market Slightly Declined In 2019: Full Report |first=Mark |last=Kane |publisher=InsideEVs.com | date=2020-02-04 |accessdate=2020-05-30}} ''Sales of new energy vehicles totaled 1,206,000 units in 2019, down 4.0% from 2018, and includes 2,737 fuel cell vehicles. Battery electric vehicle sales totaled 972,000 units (down 1.2%) and plug-in hybrid sales totaled 232,000 vehicles (down 14.5%). Sales figures include passenger cars, buses and commercial vehicles.''.</ref><ref name=ChinaNEV2020>{{cite web| url=http://en.caam.org.cn/Index/show/catid/34/id/140.html |title=Sales of New Energy Vehicles in December 2020 |author=China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) |publisher= CAAM | date=2021-01-14 | access-date=2021-02-08}} ''NEV sales in China totaled 1.637 million in 2020, consisting of 1.246 million passenger cars and 121,000 commercial vehicles.''</ref><ref name="ChinaNEV2021">{{cite web| url=http://en.caam.org.cn/Index/show/catid/54/id/1656.html |title=Sales of New Energy Vehicles in December 2021 |author=China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) |publisher= CAAM | date=2022-01-12 | access-date=2022-01-13}} ''NEV sales in China totaled 3.521 million in 2021 (all classes), consisting of 3.334 million passenger cars and 186,000 commercial vehicles.''</ref> In the ] and the ], as of 2020, the total cost of ownership of recent electric vehicles is cheaper than that of equivalent ICE cars, due to lower fueling and maintenance costs.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Preston|first=Benjamin|title=EVs Offer Big Savings Over Traditional Gas-Powered Cars|url=https://www.consumerreports.org/hybrids-evs/evs-offer-big-savings-over-traditional-gas-powered-cars/|access-date=2020-11-22|website=Consumer Reports|date=8 October 2020 |language=en-US}}</ref><ref name=autogenerated1>{{Cite web|date=25 April 2021|title=Electric Cars: Calculating the Total Cost of Ownership for Consumers|url=https://www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2021-039_electric_cars_calculating_the_total_cost_of_ownership_for_consumers.pdf|url-status=live|website=BEUC (The European Consumer Organisation)|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210516190838/https://www.beuc.eu/publications/beuc-x-2021-039_electric_cars_calculating_the_total_cost_of_ownership_for_consumers.pdf |archive-date=16 May 2021 }}</ref> | |||

| BEVs were produced by ], ], ], and others during the first part of the 20th century and, for a time, out-sold gasoline-powered vehicles. Due to technological limitations and the lack of ]-based electric technology, the top speed of these early production electric vehicles was limited to approximately 20 miles per hour. They were successfully sold as town cars to upper class customers and often marketed as suitable vehicles for women drivers due to their cleanliness, lack of noise and ease of operation. | |||

| In 2023, the ] became the world's best selling car.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Tesla Model Y Is The Best-Selling Car In The World {{!}} GreenCars |url=https://www.greencars.com/news/the-tesla-model-y-is-the-best-selling-car-in-the-world |access-date=2023-09-03 |website=www.greencars.com |language=en}}</ref> The ] became the world's all-time best-selling electric car in early 2020,<ref name="Model3TopEV">{{cite news|last=Holland|first=Maximilian|date=2020-02-10|title=Tesla Passes 1 Million EV Milestone & Model 3 Becomes All Time Best Seller|website=CleanTechnica|url=https://cleantechnica.com/2020/03/10/tesla-passes-1-million-ev-milestone-and-model-3-becomes-all-time-best-seller/|url-status=live|access-date=2020-05-15|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200412045911/https://cleantechnica.com/2020/03/10/tesla-passes-1-million-ev-milestone-and-model-3-becomes-all-time-best-seller/|archive-date=12 April 2020}}</ref> and in June 2021 became the first electric car to pass 1 million global sales.<ref name=1miModel3/> Together with other emerging automotive technologies such as autonomous driving, connected vehicles and shared mobility, electric cars form a future mobility vision called Autonomous, Connected, Electric and Shared (ACES) Mobility.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hamid |first=Umar Zakir Abdul |title=Autonomous, Connected, Electric and Shared Vehicles: Disrupting the Automotive and Mobility Sectors |date=2022 |url=https://www.sae.org/publications/books/content/r-517/ |publisher=SAE |location=US |access-date=11 November 2022 |isbn=978-1468603477}}</ref>{{pn|date=May 2024}} | |||

| ] and an electric car, 1913 (courtesy of the ])]] | |||

| ==Terminology== | |||

| Introduction of the ] by ] in 1913, which simplified the difficult and sometimes dangerous task of starting the internal combustion engine, contributed to the downfall of the electric vehicle. As did ]s, in use as early as 1895 by ] in their ] design,<ref>Bellis, M. (2006) "The History of the Automobile: The First Mass Producers of Cars - The Assembly Line" ''About.com'' accessed on 5 July 2006</ref> which allowed engines to keep cool enough to run for more than a few minutes, before which they had to stop and cool down at horse troughs along with the ] to replenish their water supply. EV's may have fallen out of favor because of the mass produced ] which went into production four years earlier in 1908. <ref>McMahon, D. (2006) "Some EV History" ''Econogics, Inc.'' accessed on 5 July 2006</ref> Ultimately, technological advances in internal-combustion powered cars advanced beyond that of their electric powered competitors, resulting in the superior performance and practicality of gasoline powered cars. By the late 1930s the early electric automobile industry had completely disappeared, with battery-electric traction being limited to niche application such as industrial vehicles. | |||

| {{See also|Vehicle classification by propulsion system|Plug-in electric vehicle#Terminology|Battery electric vehicle}} | |||

| The term "electric car" typically refers specifically to ]s (BEVs) or all-electric cars, a type of ] (EV) that has an onboard ] that can be plugged in and charged from the ], and the electricity stored on the vehicle is the ''only'' energy source that provide propulsion for the wheels. The term generally refers to highway-capable automobiles, but there are also low-speed electric vehicles with limitations in terms of weight, power, and maximum speed that are allowed to travel on certain public roads. The latter are classified as ]s (NEVs) in the United States,<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/cars/rules/rulings/lsv/lsv.html |title=US Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 49 CFR Part 571 Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards |access-date=2009-08-06 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100227044214/http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/cars/rules/rulings/lsv/lsv.html |archive-date=27 February 2010 |url-status=live }}</ref> and as electric ]s in Europe.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52010PC0542&from=EN|title=Citizens' summary EU proposal for a Regulation on L-category vehicles (two- or three-wheel vehicles and quadricycles) |publisher=European Commission |date=2010-10-04 |access-date=2023-04-06}}</ref> | |||

| The 1947 invention of the point-contact ] marked the beginning of a new era for BEV technology. Within a decade, Henney Coachworks had joined forces with National Union Electric Company, the makers of Exide batteries, to produce the first modern electric car based on transistor technology. The ] was produced in 36 volt and 72 volt configurations. The 72 volt models had a top speed approaching 60 miles per hour (96 km/h) and could travel nearly 60 miles on a charge. Despite the improved practicality of the Henney Kilowatt over previous electric cars, they were too expensive and production was ended by 1961. Even though the Henney Kilowatt never reached mass production volume, their transistor-based electric technology paved the way for modern EVs. | |||

| == History == | |||

| ===Incentives and quotas in the United States=== | |||

| {{Main|History of the electric vehicle}} | |||

| Since the late 1980s, electric vehicles have been promoted in the US through the use of tax credits. BEVs are the most common form of what is defined by the ] (CARB) as ] (ZEV) passenger ]s, because they produce no emissions while being driven. The CARB had set a minimum quota for the use of ZEVs, but it was withdrawn after complaints by auto manufacturers that it was economically unfeasible due to a lack of consumer demand. Many believe this complaint to be unwarranted because there were thousands waiting to purchase or lease electric cars. Companies such as ], ], and ] refused to meet the demand despite their production capability. US electric car leases in the 1990s were at reduced costs, and so whether high enough volumes to avoid financial loss could have been obtained is unknown. | |||

| === Early developments === | |||

| The California program was designed by the CARB to reduce air pollution and not specifically to promote electric vehicles. So the zero emissions requirement in California was replaced by a combined requirement of a very small number of ZEVs to promote research and development, and a much larger number of ]s (PZEVs), an administrative designation for an ''super ultra low emissions vehicle'' (]), which emit about ten percent of the polution of ordinary low emissions vehicles and are also certified for zero evaporative emissions. | |||

| ] is often credited with inventing the first electric car some time between 1832 and 1839.<ref name="Roth 2-3">{{cite book|first= Hans|last= Roth|title= Das erste vierrädrige Elektroauto der Welt|trans-title= The first four-wheeled electric car in the world|language= de|date= March 2011|pages= 2–3}}</ref> | |||

| ===Outside the US=== | |||

| ] 4 door sedan ] ]] | |||

| The following experimental electric cars appeared during the 1880s: | |||

| ], France]] | |||

| * In 1881, ] presented an electric car driven by an improved ] motor at the ].<ref>{{cite book |first=Ernest H |last=Wakefield |title= History of the Electric Automobile |publisher=Society of Automotive Engineers |year=1994 |isbn= 1-5609-1299-5 |pages=2–3 }}</ref> | |||

| * In 1884, ] built an electric car in ] using his own specially-designed high-capacity rechargeable batteries, although the only documentation is a photograph from 1895.<ref name="Guarnieri, 2012">{{Cite conference |last= Guarnieri |first= M. |year= 2012 |title=Looking back to electric cars |journal=Proc. HISTELCON 2012 – 3rd Region-8 IEEE HISTory of Electro – Technology Conference: The Origins of Electrotechnologies |pages=1–6 |doi= 10.1109/HISTELCON.2012.6487583 |isbn=978-1-4673-3078-7 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.owningelectriccar.com/electric-car-history.html |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20140105043545/http://www.owningelectriccar.com/electric-car-history.html |title= Electric Car History |access-date=2012-12-17 |archive-date=2014-01-05 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url= https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/5212278/Worlds-first-electric-car-built-by-Victorian-inventor-in-1884.html |newspaper=The Daily Telegraph |title=World's first electric car built by Victorian inventor in 1884 |date= 2009-04-24 |access-date=2009-07-14 |location=London |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20180421173243/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/5212278/Worlds-first-electric-car-built-by-Victorian-inventor-in-1884.html |archive-date= 21 April 2018 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * In 1888, the German ] designed the ], regarded by some as the first "real" electric car.<ref>{{Cite book |title=30-Second Great Inventions |last= Boyle |first=David |publisher=Ivy Press |year=2018 |isbn=9781782406846 |page=62 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title= Electric and Hybrid Vehicles |last=Denton |first=Tom |publisher=Routledge |year=2016 |isbn=9781317552512 |page=6 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= https://www.np-coburg.de/lokal/coburg/coburg/Elektroauto-in-Coburg-erfunden;art83423,1491254 |title=Elektroauto in Coburg erfunden |trans-title=Electric car invented in Coburg |work=Neue Presse Coburg |location=Germany |language=de |date=2011-01-12 |access-date=2019-09-30 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160309155726/https://www.np-coburg.de/lokal/coburg/coburg/Elektroauto-in-Coburg-erfunden;art83423,1491254 |archive-date=9 March 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * In 1890, Andrew Morrison introduced the first electric car to the United States.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |title=The History of the Electric Car |url=https://www.energy.gov/articles/history-electric-car |access-date=2023-12-05 |website=Energy.gov |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Electricity was among the preferred methods for automobile propulsion in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, providing a level of comfort and an ease of operation that could not be achieved by the gasoline-driven cars of the time.<ref>{{cite web |url= https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/182400/electric-automobile |title=Electric automobile |publisher= Encyclopædia Britannica (online) |access-date=2014-05-02 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20140220135955/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/182400/electric-automobile |archive-date=20 February 2014 |url-status=live }}</ref> The electric vehicle fleet peaked at approximately 30,000 vehicles at the turn of the 20th century.<ref>{{cite news|url= https://www.forbes.com/sites/justingerdes/2012/05/11/the-global-electric-vehicle-movement-best-practices-from-16-cities/ |title= The Global Electric Vehicle Movement: Best Practices From 16 Cities |first= Justin |last=Gerdes |magazine=Forbes |date=2012-05-11 |access-date=2014-10-20 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170729205753/https://www.forbes.com/sites/justingerdes/2012/05/11/the-global-electric-vehicle-movement-best-practices-from-16-cities/ |archive-date=29 July 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ;France | |||

| In 1897, electric cars first found commercial use as ] in Britain and in the United States. In London, ]'s ] were the first self-propelled vehicles for hire at a time when cabs were horse-drawn.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/the-surprisingly-old-story-of-londons-first-ever-electric-taxi/ |title= The Surprisingly Old Story of London's First Ever Electric Taxi |last= Says |first= Alan Brown |website= Science Museum Blog |date= 9 July 2012 |language= en-GB |access-date=2019-10-23 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20191023082317/https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/the-surprisingly-old-story-of-londons-first-ever-electric-taxi/ |archive-date=23 October 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> In New York City, a fleet of twelve ]s and one ], based on the design of the ], formed part of a project funded in part by the ] of ].<ref>{{cite web |url= http://edisontechcenter.org/ElectricCars.html |title=History of Electric Cars |first=Galen |last=Handy |publisher=The Edison Tech Center |year=2014 |access-date=2017-09-07 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170918161405/http://www.edisontechcenter.org/ElectricCars.html |archive-date=18 September 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> During the 20th century, the main manufacturers of electric vehicles in the United States included Anthony Electric, Baker, Columbia, Anderson, Edison, Riker, Milburn, ], and ]. Their electric vehicles were quieter than gasoline-powered ones, and did not require gear changes.<ref name="automobilesreview">{{cite web |title= Some Facts about Electric Vehicles |url= http://www.automobilesreview.com/auto-news/some-facts-about-electric-vehicles/42240/ |website=Automobilesreview |access-date=2017-10-06 |date=2012-02-25 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170811145521/http://www.automobilesreview.com/auto-news/some-facts-about-electric-vehicles/42240/ |archive-date=11 August 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url= https://www.bloomberg.com/news/photo-essays/2019-01-05/171-years-before-tesla-the-evolution-of-electric-vehicles?srnd=hyperdrive |title=171 Years Before Tesla: The Evolution of Electric Vehicles |first1= Marisa |last1= Gertz |first2= Melinda |last2= Grenier |work= Bloomberg |date= 2019-01-05 |access-date= 2019-09-30 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190111060541/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/photo-essays/2019-01-05/171-years-before-tesla-the-evolution-of-electric-vehicles?srnd=hyperdrive |archive-date= 11 January 2019 |url-status= live }}</ref> | |||

| ] has known a large development of battery-electric vehicles in the 1990s, with the most successful vehicle being the electric ]/], of which several thousand have been built, mostly for fleet use in municipalities or by ]. | |||

| Six electric cars held the ] in the 19th century.<ref>{{citation |url= http://www.macscouter.com/CubScouts/PowWow07/SCCC_2007/CubScoutThemes/Jan_2008.pdf |date=January 2008 |title=Cub Scout Car Show |access-date=2009-04-12 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160304040037/http://www.macscouter.com/CubScouts/PowWow07/SCCC_2007/CubScoutThemes/Jan_2008.pdf |archive-date=4 March 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> The last of them was the rocket-shaped ], driven by ], which broke the {{convert|100|km/h|abbr=on}} speed barrier by reaching a top speed of {{convert|105.88|km/h|abbr=on}} in 1899. | |||

| ;Norway | |||

| Electric cars remained popular until advances in ] (ICE) cars and ] of cheaper gasoline- and ]-powered vehicles, especially the ], led to a decline.<ref name=":5" /> ICE cars' much quicker refueling times and cheaper production costs made them more popular. However, a decisive moment came with the introduction in 1912 of the electric ]<ref>{{cite web|last= Laukkonen|first= J.D.|date= 1 October 2013|title= History of the Starter Motor|url=http://www.crankshift.com/history-starter-motor/|url-status=live|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190921052450/http://www.crankshift.com/history-starter-motor/|archive-date=21 September 2019|access-date=30 September 2019|work=Crank Shift | quote = This starter motor first showed up on the 1912 Cadillac, which also had the first complete electrical system, since the starter doubled as a generator once the engine was running. Other automakers were slow to adopt the new technology, but electric starter motors would be ubiquitous within the next decade.}}</ref> that replaced other, often laborious, methods of starting the ICE, such as ]. | |||

| In ], zero-emission vehicles are tax-exempt and are also allowed to use the ]. | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="160"> | |||

| ;Switzerland | |||

| File:Capture d’écran 2016-10-14 à 21.26.28.png|]'s personal electric vehicle (1881), the world's first publicly presented full-scale electric car powered by an improved ] motor | |||

| File:First Trolleybuss of Siemens in Berlin 1882 (postcard).jpg|The ], the world's first ] by ], Berlin 1882 | |||

| File:1888 Flocken Elektrowagen.jpg|The ] (1888) was the first four-wheeled electric car in the world<ref>http://www.np-coburg.de/lokal/coburg/coburg/Elektroauto-in-Coburg-erfunden;art83423,1491254 np-coburg.de</ref> | |||

| File:Thomas Parker Electric car.jpg|Early electric car built by ] - photo from 1895<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/genealogy/Parker/ElwellParker.htm |title=Elwell-Parker, Limited |access-date=2016-02-17 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160304100247/http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/genealogy/Parker/ElwellParker.htm |archive-date=4 March 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| File:Jamais contente.jpg|"]", 1899 | |||

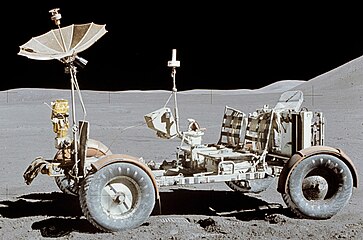

| File:Apollo15LunarRover.jpg|]'s ]s were battery-driven (1971) | |||

| File:EV1 (6).jpg|The ], one of the cars introduced due to a ] (CARB) mandate, had a range of {{Convert|160|mi|km|abbr= in|order= flip}} with ] in 1999. | |||

| File:Tesla Roadster.JPG|The ] (2008) helped inspire the modern generation of electric vehicles. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Modern electric cars=== | |||

| In ], battery-electric vehicles have some popularity with private users. There is a national network of publicly accessible charging points, called , which also covers part of ] and ]. | |||

| In the early 1990s the ] (CARB) began a push for more fuel-efficient, lower-emissions vehicles, with the ultimate goal of a move to ]s such as electric vehicles.<ref name="TwoBillion">{{cite book |last1=Sperling |first1=Daniel |first2=Deborah |last2= Gordon |title=Two billion cars: driving toward sustainability |year=2009 |pages= |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn= 978-0-19-537664-7 |url=https://archive.org/details/twobillioncarsdr00sper_0/page/22 }}</ref><ref name="Boschert06">{{cite book |first=Sherry |last=Boschert |title=Plug-in Hybrids: The Cars that will Recharge America |year=2006 |pages= |publisher=New Society Publishers |isbn=978-0-86571-571-4 |url= https://archive.org/details/pluginhybridscar00bosc/page/15 }}</ref> In response, automakers developed electric models. These early cars were eventually withdrawn from the U.S. market, because of a massive campaign by the US automakers to discredit the idea of electric cars.<ref>See '']'' (2006)</ref> | |||

| ;United Kingdom | |||

| ] electric-automaker ] began development in 2004 of what would become the ], first delivered to customers in 2008. The Roadster was the first highway-legal all-electric car to use ] cells, and the first production all-electric car to travel more than {{convert|200|mi|km|abbr= in|round=5|order=flip}} per charge.<ref>{{cite web |url= https://cleantechnica.com/2015/04/26/electric-car-history/ |title=Electric Car Evolution |first= Zachary |last=Shahan |publisher=Clean Technica |date=2015-04-26 |access-date=2016-09-08 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160918061731/https://cleantechnica.com/2015/04/26/electric-car-history/ |archive-date=18 September 2016 |url-status=live }} ''2008: The Tesla Roadster becomes the first production electric vehicle to use lithium-ion battery cells as well as the first production electric vehicle to have a range of over 200 miles on a single charge.''</ref> | |||

| In ], electrically powered vehicles have been exempted from the ]. In most cities of the ] low speed electric ]s (milk trucks) are used for the home delivery of fresh ]. | |||

| ], a ] company based in ], but steered from ], developed and sold battery charging and ] services for electric cars. The company was publicly launched on 29 October 2007 and announced deployment of ]s in ], ] and ] in 2008 and 2009. The company planned to deploy the infrastructure on a country-by-country basis. In January 2008, Better Place announced a ] with ] to build the world's first Electric Recharge Grid Operator (ERGO) model for Israel. Under the agreement, Better Place would build the electric recharge grid and ] would provide the ]s. Better Place filed for bankruptcy in Israel in May 2013. The company's financial difficulties were caused by mismanagement, wasteful efforts to establish toeholds and run pilots in too many countries, the high investment required to develop the charging and swapping infrastructure, and a market penetration far lower than originally predicted.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Blum |first=Brian |url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/990318853 |title=Totaled : the billion-dollar crash of the startup that took on big auto, big oil and the world |isbn=978-0-9830428-2-2 |oclc=990318853}}</ref> | |||

| ===Selected production vehicles=== | |||

| {{mainarticle|List of production battery electric vehicles}} | |||

| ] has invested in a wide-ranging electrification strategy in Europe, North America and China, with its ].]] | |||

| Some popular battery electric vehicles sold or leased to fleets include (in chronological order): | |||

| The ], launched in 2009 in Japan, was the first highway-legal ] electric car,<ref name="Reuters100330">{{cite news|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTOE62T09V20100330 |title=Mitsubishi Motors lowers price of electric i-MiEV|date= 2010-03-30 |first= Chang-Ran |last= Kim |work= Reuters|access-date= 2020-05-22 }}</ref> and also the first all-electric car to sell more than 10,000 units. Several months later, the ], launched in 2010, surpassed the i MiEV as the best selling all-electric car at that time.<ref name="Guinnes">{{cite news |url= http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/records-10000/best-selling-electric-car/|title=Best-selling electric car |work=Guinness World Records|year=2012|access-date=2020-05-22|url-status=dead|archive-url= https://archive.today/20130216050030/http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/records-10000/best-selling-electric-car/|archive-date=2013-02-16}}</ref> | |||

| <div style="clear: both"></div> | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| !Name | |||

| !Comments | |||

| !Production years | |||

| !Number produced | |||

| !Cost | |||

| |- | |||

| Starting in 2008, a renaissance in electric vehicle manufacturing occurred due to advances in batteries, and the desire to reduce ] and to improve urban ].<ref name="PEVs">{{cite book|title=Plug-In Electric Vehicles: What Role for Washington?|editor=]|year=2009|publisher=The Brookings Institution|isbn=978-0-8157-0305-1|edition=1st.|url= http://www.brookings.edu/press/Books/2009/pluginelectricvehicles.aspx|pages=1–6|access-date=6 February 2011|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190328104012/https://www.brookings.edu/press/Books/2009/pluginelectricvehicles.aspx/ |archive-date=28 March 2019|url-status=live}}''See Introduction''</ref> During the 2010s, the ] expanded rapidly with government support.<ref>{{Cite web|title= DRIVING A GREEN FUTURE: A RETROSPECTIVE REVIEW OF CHINA'S ELECTRIC VEHICLE DEVELOPMENT AND OUTLOOK FOR THE FUTURE|url=https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/China-green-future-ev-jan2021.pdf |url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210117071311/https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/China-green-future-ev-jan2021.pdf |archive-date=17 January 2021 }}</ref> Several automakers marked up the prices of their electric vehicles in anticipation of the subsidy adjustments, including Tesla, Volkswagen and Guangzhou-based GAC Group, which counts Fiat, Honda, Isuzu, Mitsubishi, and Toyota as foreign partners.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2022-01-03|title=Automakers raise prices for NEVs in China ahead of subsidy cuts|url=https://kr-asia.com/automakers-raise-prices-for-nevs-in-china-ahead-of-subsidy-cuts|access-date=2022-01-13|website=KrASIA|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| !] | |||

| |The first modern (transistor-based) electric car, capable of highway speeds of up to 60mph and outfitted with modern hydraulic brakes. | |||

| |1958-1960 | |||

| |<100 | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| In July 2019 US-based '']'' magazine awarded the fully-electric Tesla Model S the title "ultimate car of the year".<ref>{{cite news |url= https://www.motortrend.com/news/2013-tesla-model-s-beats-chevy-toyota-cadillac-ultimate-car-of-the-year/ |title=2013 Tesla Model S Beats Chevy, Toyota, and Cadillac for Ultimate Car of the Year Honors |first= Scott |last= Evans |work= MotorTrend |date= 2019-07-10 |access-date=2019-07-17 |quote= We are confident that, were we to summon all the judges and staff of the past 70 years, we would come to a rapid consensus: No vehicle we've awarded, be it Car of the Year, Import Car of the Year, SUV of the Year, or Truck of the Year, can equal the impact, performance, and engineering excellence that is our Ultimate Car of the Year winner, the 2013 Tesla Model S. }}</ref> In March 2020 the ] passed the Nissan Leaf to become the world's all-time best-selling electric car, with more than 500,000 units delivered;<ref name="Model3TopEV"/> it reached the milestone of 1 million global sales in June 2021.<ref name=1miModel3/> | |||

| !] | |||

| |For lease only, all recovered and most destroyed | |||

| |1996-2003 | |||

| |>1000 | |||

| |~ US $40K without subsidies | |||

| |- | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| !] | |||

| | total_width = 450 | |||

| |Three-wheeled EV with pedal assist option. Produced in Germany. | |||

| | image1 = 2020+ Electric vehicle stock - International Energy Agency.svg | |||

| |1996+ | |||

| | caption1 = The global stock of both plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) and battery electric vehicles (BEVs) has grown steadily since the 2010s.<ref name=IEA_GlobalEVoutlook_2023>{{cite web |title=Global EV Outlook 2023 / Trends in electric light-duty vehicles |url=https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023/trends-in-electric-light-duty-vehicles |publisher=International Energy Agency |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230512122042/https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023/trends-in-electric-light-duty-vehicles |archive-date=12 May 2023 |date=April 2023 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |>750 | |||

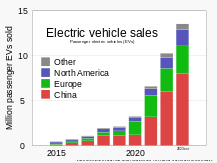

| | image2 = 2015- Passenger electric vehicle (EV) annual sales - BloombergNEF.svg | |||

| | | |||

| | caption2 = Sales of passenger electric vehicles (EVs) indicate a trend away from gas-powered vehicles.<ref name=BloombergNEF_20230112>Data from {{cite news |last1=McKerracher |first1=Colin |title=Electric Vehicles Look Poised for Slower Sales Growth This Year |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-01-12/electric-vehicles-look-poised-for-slower-sales-growth-this-year |publisher=BloombergNEF |date=12 January 2023 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20230112125649/https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-01-12/electric-vehicles-look-poised-for-slower-sales-growth-this-year |archive-date=12 January 2023 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| }} | |||

| In the third quarter of 2021, the ] reported that sales of electric vehicles had reached six percent of all US light-duty automotive sales, the highest volume of EV sales ever recorded at 187,000 vehicles. This was an 11% sales increase, as opposed to a 1.3% increase in gasoline and diesel-powered units. The report indicated that California was the US leader in EV with nearly 40% of US purchases, followed by Florida – 6%, Texas – 5% and New York 4.4%.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Ali |first1=Shirin |title=More Americans are buying electric vehicles, as gas car sales fall, report says |url=https://thehill.com/changing-america/resilience/smart-cities/599426-more-americans-are-buying-electric-vehicles-as-gas/ |work=The Hill |date=23 March 2022}}</ref> | |||

| !] minivan | |||

| |Second generation of the ], ; | |||

| |1997-2000 | |||

| | | |||

| |leased to government and utility fleets only | |||

| |- | |||

| Electric companies from the Middle East have been designing electric cars. Oman's ] have developed the ] which is expected to begin production in 2023. Built from carbon fibre, it has a range of about {{convert|350|miles|km|round=10|order=flip|abbr=in}} and can accelerate from {{convert|0-80|mph|km/h|round=5|order=flip|abbr=on}} in about 4 secs.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.greenprophet.com/2022/03/oman-electrica-car-mays-motors/ |title=Oman makes first electric car in the Middle East |first=Karin |last=Kloosterman |work=Green Prophet |location=Canada |date=23 March 2022 |access-date=22 May 2022}}</ref> In Turkey, the EV company ] is starting production of its electric vehicles. Batteries will be created in a joint venture with the Chinese company ].<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.greenprophet.com/2022/05/togg-electric-turkey/ |title=Turkey's all electric Togg EV |first=Karin |last=Kloosterman |work=Green Prophet |location=Canada |date=22 May 2022 |access-date=22 May 2022}}</ref> | |||

| !] | |||

| |First BEV from a major automaker without lead acid batteries. 80–110 mile range (130–180 km); 80+ MPH (130 km/h) top speed; 24 twelve volt ] | |||

| |1997-1999 | |||

| |~300 | |||

| |US $455/month for 36 month lease, or $53,000 without subsidies | |||

| |- | |||

| ==Economics== | |||

| !] | |||

| |Rare, some leased and sold on U.S. East and west coast, supported. Toyota agreed to stop crushing. | |||

| |1997-2002 | |||

| |1249 | |||

| |US $40K without subsidies | |||

| |- | |||

| === Manufacturing cost === | |||

| !] | |||

| The most expensive part of an electric car is its battery. The price decreased from {{Euro|605}} per kWh in 2010, to {{Euro|170}} in 2017, to {{Euro|100}} in 2019.<ref>{{cite news |url= https://www.umweltdialog.de/de/wirtschaft/mobilitaet/2018/Trotz-fallender-Batteriekosten-bleiben-Elektromobile-teuer.php |title=Trotz fallender Batteriekosten bleiben E-Mobile teuer |trans-title=Despite falling battery costs electric cars remain expensive |work=Umwelt Dialog |location=Germany |language=de |date=2018-07-31 |access-date=2019-03-12 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191228085104/https://www.umweltdialog.de/de/wirtschaft/mobilitaet/2018/Trotz-fallender-Batteriekosten-bleiben-Elektromobile-teuer.php |archive-date=28 December 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url= https://www.nzz.ch/mobilitaet/auto-mobil/audi-entwicklungsvorstand-rothenpieler-brennstoffzelle-im-fokus-ld.1465168 |title=Wir arbeiten mit Hochdruck an der Brennstoffzelle |trans-title=We are working hard on the fuel cell |first=Stephan |last=Hauri |work=Neue Zürcher Zeitung |location=Switzerland |language=de |date=2019-03-08 |access-date=2019-03-12 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190326111120/https://www.nzz.ch/mobilitaet/auto-mobil/audi-entwicklungsvorstand-rothenpieler-brennstoffzelle-im-fokus-ld.1465168 |archive-date=26 March 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> When designing an electric vehicle, manufacturers may find that for low production, converting existing ] may be cheaper, as development cost is lower; however, for higher production, a dedicated platform may be preferred to optimize design, and cost.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://automotivelogistics.media/intelligence/shifting-currents |title=EV supply chains: Shifting currents |first= Jonathan |last=Ward |date= 2017-04-28 |publisher=Automotive Logistics |access-date= 2017-05-13 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170803095635/https://automotivelogistics.media/intelligence/shifting-currents |archive-date= 2017-08-03 |url-status= live}}</ref> | |||

| |S-10 with ] powertrain, 45 sold to private owners and survived; some sold to fleets, available on secondary market as refurbished vehicles. | |||

| |1998 | |||

| |100 | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| ===Total cost of ownership=== | |||

| !] Electrique | |||

| In the EU and US, but not yet China, the total cost of ownership of recent electric cars is cheaper than that of equivalent gasoline cars, due to lower fueling and maintenance costs.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=autogenerated1 /><ref>{{Cite journal|date=2021-02-01|title=The total cost of electric vehicle ownership: A consumer-oriented study of China's post-subsidy era|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421520307345|journal=Energy Policy|language=en|volume=149|pages=112023|doi=10.1016/j.enpol.2020.112023|issn=0301-4215|last1=Ouyang|first1=Danhua|last2=Zhou|first2=Shen|last3=Ou|first3=Xunmin|bibcode=2021EnPol.14912023O |s2cid=228862530}}</ref> A 2024 '']'' analysis of 29 car brands found Tesla was the least expensive to maintain over a 10-year period; Tesla was the only all-electric brand included.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-04-23 |title=Four of the Five Least Expensive Car Brands to Maintain Are American |url=https://www.consumerreports.org/cars/car-maintenance/the-cost-of-car-ownership-a1854979198/ |access-date=2024-04-30 |website=Consumer Reports |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| |; in three packs. Very similar to the ] which has also been offered as a BEV. | |||

| |1998-2005 | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| The greater the distance driven per year, the more likely the ] for an electric car will be less than for an equivalent ICE car.<ref>{{cite web |title=Large Auto Leasing Company: Electric Cars Have Mostly Lower Total Cost in Europe |url=https://cleantechnica.com/2020/05/08/large-auto-leasing-company-electric-cars-have-mostly-lower-total-cost-in-europe/ |website=CleanTechnica |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20200521114051/https://cleantechnica.com/2020/05/08/large-auto-leasing-company-electric-cars-have-mostly-lower-total-cost-in-europe/ |archive-date=21 May 2020 |date=9 May 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> The ] distance varies by country depending on the taxes, subsidies, and different costs of energy. In some countries the comparison may vary by city, as a type of car may have different charges to enter different cities; for example, in England, ] charges ICE cars more than ] does.<ref name=Brum2019>{{cite news |title=Birmingham clean air charge: What you need to know |url= https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-birmingham-44551122 |work=] |date=13 March 2019 |access-date=22 March 2019 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190323125626/https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-birmingham-44551122 |archive-date=23 March 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| !] | |||

| |Some sold, most leased; almost all recovered and most destroyed. Ford has announced reconditioning and sale of a limited quantity to former leaseholders by lottery. | |||

| |1998-2002 | |||

| |1500, perhaps 200 surviving | |||

| |~ US $50K subsidized down to $20K | |||

| |- | |||

| ==== Purchase cost ==== | |||

| !] | |||

| |Mid-sized station wagon designed from the ground up as , | |||

| |1998-2000 | |||

| |~133 | |||

| |US $470/month lease only | |||

| |- | |||

| Several national and local governments have established ] to reduce the purchase price of electric cars and other plug-ins.<ref name="JAMAFact">{{cite web |url= http://jama.org/pdf/FactSheet10-2009-09-24.pdf |title=Fact Sheet – Japanese Government Incentives for the Purchase of Environmentally Friendly Vehicles |publisher=] |access-date=2010-12-24|url-status=dead|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20101226222150/http://www.jama.org/pdf/FactSheet10-2009-09-24.pdf |archive-date=2010-12-26}}</ref><ref name="NYT0610">{{cite news|url= http://wheels.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/02/china-to-start-pilot-program-providing-subsidies-for-electric-cars-and-hybrids/ |title=China to Start Pilot Program, Providing Subsidies for Electric Cars and Hybrids |work=The New York Times |date=2010-06-02 |access-date=2010-06-02 |first=Jim |last=Motavalli |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100603030955/http://wheels.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/02/china-to-start-pilot-program-providing-subsidies-for-electric-cars-and-hybrids/ |archive-date=3 June 2010 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="GCC0420">{{cite web |url=http://www.greencarcongress.com/2010/04/acea-tax-20100421.html#more |title=Growing Number of EU Countries Levying CO2 Taxes on Cars and Incentivizing Plug-ins |publisher=Green Car Congress |date=2010-04-21 |access-date=2010-04-23 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20101231035827/http://www.greencarcongress.com/2010/04/acea-tax-20100421.html#more |archive-date=31 December 2010 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="IRS2009">{{cite web|date=2009-11-30|title=Notice 2009–89: New Qualified Plug-in Electric Drive Motor Vehicle Credit|url=https://www.irs.gov/irb/2009-48_IRB/ar09.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100328102104/http://www.irs.gov/irb/2009-48_IRB/ar09.html|archive-date=28 March 2010|access-date=2010-04-01|publisher=Internal Revenue Service}}</ref> | |||

| !] TH!NK City | |||

| |Two seat, , ] | |||

| |1999-2002 | |||

| |1005 | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| {{As of|2020|}}, the ] is more than a quarter of the total cost of the car.<ref>{{Cite news|date=2020-12-16|title=Batteries For Electric Cars Speed Toward a Tipping Point|language=en|work=Bloomberg.com|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-12-16/electric-cars-are-about-to-be-as-cheap-as-gas-powered-models|access-date=2021-03-04}}</ref> Purchase prices are expected to drop below those of new ICE cars when battery costs fall below {{USD|100}} per kWh, which is forecast to be in the mid-2020s.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2020-03-13|title=EV-internal combustion price parity forecast for 2023 – report|url=https://www.mining.com/ev-internal-combustion-price-parity-forecasted-for-2023-report/|access-date=2020-10-30|website=MINING.COM|language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=2020-10-23|title=Why are electric cars expensive? The cost of making and buying an EV explained|url=https://auto.hindustantimes.com/auto/news/why-are-electric-cars-expensive-the-cost-of-making-and-buying-an-ev-explained-41603419957680.html|access-date=2020-10-30|website=Hindustan Times|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| !] | |||

| |India-built city car (40 mph top speed,) now also sold in England as the "G-Whiz" | |||

| |2001+ | |||

| | | |||

| | US $15K | |||

| |- | |||

| Leasing or subscriptions are popular in some countries,<ref name="EarlyEV">{{cite news|last=Stock|first=Kyle|date=2018-01-03|title=Why early EV adopters prefer leasing – by far|newspaper=Automotive News|url=http://www.autonews.com/article/20180103/OEM05/180109952/why-ev-drivers-prefer-leasing-by-far|access-date=2018-02-05}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Ben|date=2019-12-14|title=Should I Lease An Electric Car? What To Know Before You Do|url=http://15.222.154.211/lease-an-electric-car/|access-date=2020-10-30|website=Steer|language=en-US|archive-date=12 August 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210812034604/http://15.222.154.211/lease-an-electric-car/|url-status=dead}}</ref> depending somewhat on national taxes and subsidies,<ref>{{Cite web|date=2020-07-15|title=Subsidies slash EV lease costs in Germany, France|url=https://europe.autonews.com/automakers/subsidies-slash-ev-lease-costs-germany-france|access-date=2020-10-30|website=Automotive News Europe|language=en}}</ref> and end of lease cars are expanding the second hand market.<ref>{{Cite magazine|title=To Save the Planet, Get More EVs Into Used Car Lots|language=en-us|magazine=Wired|url=https://www.wired.com/story/save-planet-more-evs-used-car-lots/|access-date=2020-10-30|issn=1059-1028}}</ref> | |||

| !colspan=5|]s (NEVs, top speed limited to 25 MPH) | |||

| |- | |||

| In a June 2022 report by AlixPartners, the cost for raw materials on an average EV rose from $3,381 in March 2020 to $8,255 in May 2022. The cost increase voice is attributed mainly to lithium, nickel, and cobalt.<ref>{{cite news |last=Wayland |first=Michael |url=https://www.cnbc.com/2022/06/22/electric-vehicle-raw-material-costs-doubled-during-pandemic.html |title=Raw material costs for electric vehicles have doubled during the pandemic |work=] |date=2022-06-22 |accessdate=2022-06-22 }}</ref> | |||

| !] | |||

| |Five models currently in production, including two pickup trucks; all electronically limited to 25 MPH to qualify as NEVs, and using lead-acid batteries. ] in 2000.] | |||

| |1998+ | |||

| |>30,000 | |||

| |varies by model, to | |||

| |- | |||

| ==== Running costs ==== | |||

| !] | |||

| Electricity almost always costs less than gasoline per kilometer travelled, but the price of electricity often varies depending on where and what time of day the car is charged.<ref>{{cite news |url= https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffmcmahon/2018/01/14/electric-vehicles-cost-less-than-half-as-much-to-drive/#6b6004853f97 |title=Electric Vehicles Cost Less Than Half As Much To Drive |last=McMahon |first=Jeff |magazine=Forbes |access-date=2018-05-18 |language=en |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20180518131437/https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffmcmahon/2018/01/14/electric-vehicles-cost-less-than-half-as-much-to-drive/#6b6004853f97 |archive-date=18 May 2018 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=How much does it cost to charge an electric car?|url=https://www.autocar.co.uk/car-news/advice-electric-cars/how-much-does-it-cost-charge-electric-car|access-date=2021-08-01|website=Autocar|language=en}}</ref> Cost savings are also affected by the price of gasoline which can vary by location.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Kaminski |first1=Joe |title=The U.S. States Where You'll Save the Most Switching from Gas to Electric Vehicles |url=https://www.mroelectric.com/blog/state-by-state-cost-electric-vehicles/ |website=www.mroelectric.com |date=17 August 2021 |publisher=MRO Electric |access-date=3 September 2021}}</ref> | |||

| |Five models currently in production, all very similar to model, using lead-acid batteries and limited to 25 MPH to qualify as NEVs. Sedan range is 30 miles. | |||

| |2001+ | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| ==Environmental aspects== | |||

| |} | |||

| ] in ] is one of the largest known ] reserves in the world.<ref name=NYTBolivia>{{cite news|url= https://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/03/world/americas/03lithium.html?_r=1 |title=In Bolivia, Untapped Bounty Meets Nationalism |first=Simon |last=Romero |newspaper=The New York Times |date=2009-02-02|access-date=2010-02-28|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20161227122218/http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/03/world/americas/03lithium.html?_r=1|archive-date=27 December 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.evaporiticosbolivia.org/index.php?Modulo=Temas&Opcion=Reservas |title=Página sobre el Salar (Spanish) |publisher=Evaporiticosbolivia.org |access-date=2010-11-27 |url-status=dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20110323141916/http://www.evaporiticosbolivia.org/index.php?Modulo=Temas&Opcion=Reservas |archive-date=2011-03-23 }}</ref>]] | |||

| {{Main|Environmental aspects of the electric car}} | |||

| Electric cars have several benefits when replacing ICE cars, including a significant reduction of local air pollution, as they do not emit ] such as ]s, ]s, ], ], ], and various ].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Vehicle exhaust emissions {{!}} What comes out of a car exhaust? {{!}} RAC Drive|url=https://www.rac.co.uk/drive/advice/emissions/vehicle-exhaust-emissions-what-comes-out-of-your-cars-exhaust/|access-date=2021-08-06|website=www.rac.co.uk|language=en}}</ref> Similar to ICE vehicles, electric cars emit particulates from tyre and brake wear<ref>{{Cite web|title=Tyre pollution 1000 times worse than tailpipe emissions|url=https://www.fleetnews.co.uk/news/environment/2020/03/06/tyre-pollution-1000-times-worse-than-tailpipe-emissions|access-date=2020-10-30|website=www.fleetnews.co.uk|language=en}}</ref> which may damage health,<ref>{{Cite journal|date=2020-09-01|title=Tyre and road wear particles (TRWP) - A review of generation, properties, emissions, human health risk, ecotoxicity, and fate in the environment|journal=Science of the Total Environment|language=en|volume=733|pages=137823|doi=10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137823|issn=0048-9697|doi-access=free|last1=Baensch-Baltruschat|first1=Beate|last2=Kocher|first2=Birgit|last3=Stock|first3=Friederike|last4=Reifferscheid|first4=Georg|pmid=32422457|bibcode=2020ScTEn.73337823B}}</ref> although regenerative braking in electric cars means less brake dust.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2019-07-02|title=EVs: Clean Air and Dirty Brakes|url=https://thebrakereport.com/clean-air-dirty-brakes/|access-date=2020-11-13|website=The BRAKE Report|language=en-US}}</ref> More research is needed on non-exhaust particulates.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Statement on the evidence for health effects associated with exposure to non-exhaust particulate matter from road transport|url=https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/917308/COMEAP_Statement__on_the__evidence__for__health__effects__associated__with__exposure_to_non_exhaust_particulate_matter_from_road_transport_-COMEAP-Statement-non-exhaust-PM-health-effects.pdf|url-status=live|website=UK Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201022235723/https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/917308/COMEAP_Statement__on_the__evidence__for__health__effects__associated__with__exposure_to_non_exhaust_particulate_matter_from_road_transport_-COMEAP-Statement-non-exhaust-PM-health-effects.pdf |archive-date=22 October 2020 }}</ref> The sourcing of ] (oil well to gasoline tank) causes further damage as well as use of resources during the extraction and refinement processes. | |||

| ==Comparison to internal combustion vehicles== | |||

| ===Operational cost=== | |||

| Electric vehicles typically cost between two and four cents per mile to operate, while gasoline-powered ICE vehicles currently cost about four to six times as much. <ref>Idaho National Laboratory (2005) "Comparing Energy Costs per Mile for Electric and Gasoline-Fueled Vehicles" ''Advanced Vehicle Testing Activity'' accessed 11 July 2006.</ref> | |||

| Depending on the production process and the source of the electricity to charge the vehicle, emissions may be partly shifted from cities to the plants that generate electricity and produce the car as well as to the transportation of material.<ref name="TwoBillion"/> The amount of carbon dioxide emitted depends on the ] of the electricity source and the efficiency of the vehicle. For ], the life-cycle emissions vary depending on the proportion of ], but are always less than ICE cars.<ref>{{Cite web|title=A global comparison of the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of combustion engine and electric passenger cars {{!}} International Council on Clean Transportation|url=https://theicct.org/publications/global-LCA-passenger-cars-jul2021|access-date=2021-08-06|website=theicct.org}}</ref> | |||

| ===Energy efficiency=== | |||

| Production and ] BEVs typically use 0.3 to 0.5 kilowatt-hours per mile (0.2 to 0.3 kWh/km). <ref>Idaho National Laboratory (2006) "Full Size Electric Vehicles" ''Advanced Vehicle Testing Activity'' accessed 5 July 2006</ref> <ref>Idaho National Laboratory (2006) "1999 General Motors EV1 with NiMH: Performance Statistics" ''Electric Transportation Applications'' accessed 5 July 2006</ref> <!-- EV1 efficiency of .179 kWh/mi and .373 with poor charging, See Talk. --> Nearly half of this power consumption is due to inefficiencies in charging the batteries. The U.S. fleet average of 23 miles per gallon of ] is equivalent to 1.58 kilowatt-hours per mile and the 70 MPG ] gets 0.52 kWh/mi (assuming 36.4 kWh per U.S. gallon of gasoline), so battery electric vehicles are relatively ]. When comparisons of the total energy cycle are made, the relative efficiency of BEVs drops, but such calculations are usually not provided for internal combustion vehicles (e.g. the energy used to produce specialized fuels such as gasoline is usually left unstated.) | |||

| The cost of installing charging infrastructure has been estimated to be repaid by health cost savings in less than three years.<ref>{{cite news |title=Electric car switch on for health benefits |url=https://phys.org/news/2019-05-electric-car-health-benefits.html |publisher=Inderscience Publishers |location=UK |date=2019-05-16 |access-date=2019-06-01 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190529160512/https://phys.org/news/2019-05-electric-car-health-benefits.html |archive-date=29 May 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> According to a 2020 study, balancing ] supply and demand for the rest of the century will require good recycling systems, vehicle-to-grid integration, and lower lithium intensity of transportation.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Greim|first1=Peter |last2=Solomon|first2=A. A.|last3=Breyer|first3=Christian |date=2020-09-11|title=Assessment of lithium criticality in the global energy transition and addressing policy gaps in transportation|url= |journal=Nature Communications|language=en |volume=11|issue=1|pages=4570 |doi=10.1038/s41467-020-18402-y|pmid=32917866 |pmc=7486911 |bibcode=2020NatCo..11.4570G |issn=2041-1723}}</ref> | |||

| CO<sub>2</sub> emissions <ref>US Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Agency (Model year 2007) "Search for cars that don't need gasoline" ''Fuel Economy Guide'' accessed 5 July 2006</ref> are useful for comparison of electricity and gasoline consumption. Such comparisons include energy production, transmission, charging, and vehicle losses. CO<sub>2</sub> emissions improve in BEVs with ] electricity production but are fixed for gasoline vehicles. (Unfortunately, such figures for the ], ], EVPlus, and other production vehicles are unavailable.) | |||

| Some activists and journalists have raised concerns over the perceived lack of impact of electric cars in solving the climate change crisis<ref>{{cite web |last1=Casson |first1=Richard |title=We don't just need electric cars, we need fewer cars |url=https://www.greenpeace.org/international/story/13968/we-dont-just-need-electric-cars-we-need-fewer-cars/ |website=Greenpeace International |publisher=Greenpeace |access-date=13 June 2021}}</ref> compared to other, less popularized methods.<ref>{{cite news |title=Let's Count the Ways E-Scooters Could Save the City |url=https://www.wired.com/story/e-scooter-micromobility-infographics-cost-emissions/ |access-date=13 June 2021 |publisher=Wired |date=December 7, 2018}}</ref> These concerns have largely centered around the existence of less carbon-intensive and more efficient forms of transportation such as ],<ref>{{Cite web|last=Brand|first=Christian|title=Cycling is ten times more important than electric cars for reaching net-zero cities|url=http://theconversation.com/cycling-is-ten-times-more-important-than-electric-cars-for-reaching-net-zero-cities-157163|access-date=2021-08-10|website=The Conversation|date=29 March 2021 |language=en}}</ref> ] and e-scooters and the continuation of a system designed for cars first.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Laughlin |first1=Jason |title=Why is Philly Stuck in Traffic? |url=https://www.inquirer.com/transportation/inq/traffic-philadelphia-center-city-bike-lanes-subway-bus-transit-solutions-20190129.html |access-date=13 June 2021 |publisher=The Philadelphia Inquirer |date=January 29, 2018}}</ref> | |||

| <center> | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| !Model!!]s CO<sub>2</sub><br>(conventional,<br>mostly ] <br>electricity production)!!Short tons CO<sub>2</sub><br>(renewable electricity <br>production, <br>''e.g.,'' ]<br>or ]) | |||

| |- | |||

| |2002 Toyota RAV4-EV (pure BEV)||3.8||0.0 | |||

| |- | |||

| |2000 Toyota RAV4 2wd (gasoline)||7.2||7.2 | |||

| |- | |||

| !colspan=3|Other battery electric vehicle(s) | |||

| |- | |||

| |2000 Nissan Altra EV||3.5||0.0 | |||

| |- | |||

| !colspan=3|]s | |||

| |- | |||

| |2001 Honda Insight||3.1||3.1 | |||

| |- | |||

| |2005 Toyota Prius||3.5||3.5 | |||

| |- | |||

| |2005 Ford Escape H 2x||5.8||5.8 | |||

| |- | |||

| |2005 Ford Escape H 4x||6.2||6.2 | |||

| |- | |||

| !colspan=3|Internal combustion engine vehicles | |||

| |- | |||

| |2005 Dodge Neon 2.0L||6.0||6.0 | |||

| |- | |||

| |2005 Ford Escape 4x||8.0||8.0 | |||

| |- | |||

| |2005 GMC Envoy XUV 4x||11.7||11.7 | |||

| |}</center> | |||

| === Public opinion === | |||

| ] has a large impact on energy efficiency as the speed of the vehicle increases. ] is available. | |||

| ] | |||

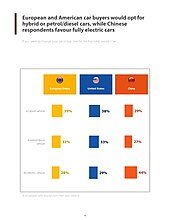

| A 2022 survey found that 33% of car buyers in Europe will opt for a petrol or diesel car when purchasing a new vehicle. 67% of the respondents mentioned opting for the hybrid or electric version.<ref name=":28">{{Cite web |title=2021-2022 EIB Climate Survey, part 2 of 3: Shopping for a new car? Most Europeans say they will opt for hybrid or electric |url=https://www.eib.org/en/surveys/climate-survey/4th-climate-survey/hybrid-electric-petrol-cars-flying-holidays-climate.htm |access-date=2022-04-04 |website=EIB.org |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=fm |date=2022-02-02 |title=Cypriots prefer hybrid or electric cars |url=https://www.financialmirror.com/2022/02/02/cypriots-prefer-hybrid-or-electric-cars/ |access-date=2022-04-05 |website=Financial Mirror |language=en-GB}}</ref> More specifically, it found that electric cars are only preferred by 28% of Europeans, making them the least preferred type of vehicle. 39% of Europeans tend to prefer ]s, while 33% prefer petrol or ].<ref name=":28"/><ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-02-01 |title=Germans less enthusiastic about electric cars than other Europeans - survey |url=https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/germans-less-enthusiastic-about-electric-cars-other-europeans-survey |access-date=2022-04-05 |website=Clean Energy Wire |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Environmental impact=== | |||

| Due to their relatively beneficial effect on environment, electric vehicles are important for improving motor vehicle traffic to provide a healthier living environment. | |||

| 44% Chinese car buyers, on the other hand, are the most likely to buy an electric car, while 38% of Americans would opt for a hybrid car, 33% would prefer petrol or diesel, while only 29% would go for an electric car.<ref name=":28" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Rahmani |first1=Djamel |last2=Loureiro |first2=Maria L. |date=2018-03-21 |title=Why is the market for hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) moving slowly? |journal=PLOS ONE |language=en |volume=13 |issue=3 |pages=e0193777 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0193777 |issn=1932-6203 |pmc=5862411 |pmid=29561860|bibcode=2018PLoSO..1393777R |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Many factors must be considered when comparing vehicles' total environmental impact. The most comprehensive comparison is a "cradle-to-grave" or ''lifecycle'' analysis. Such an analysis considers all inputs including original production and fuel sources and all outputs and end products including emissions and disposal. The varying amounts and types of inputs and outputs vary in their environmental effects and are difficult to directly compare. For example, whether the environmental effects of ] and ] ] from a ] production facility are less than those of ] ]s and ] ] is unknown. Similar comparisons would need to be addressed for each input and output in order to make fair judgement of relative total environmental impact. | |||

| Specifically for the ], 47% of car buyers over 65 years old are likely to purchase a hybrid vehicle, while 31% of younger respondents do not consider hybrid vehicles a good option. 35% would rather opt for a petrol or diesel vehicle, and 24% for an electric car instead of a hybrid.<ref name=":28" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-02-02 |title=67% of Europeans will opt for a hybrid or electric vehicle as their next purchase, says EIB survey |url=https://mayorsofeurope.eu/reports-analyses/67-of-europeans-will-opt-for-a-hybrid-or-electric-vehicle-as-their-next-purchase/ |access-date=2022-04-05 |website=Mayors of Europe |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| A large lifecycle input difference of BEVs compared to ICE vehicles is that they require electricity instead of a liquid fuel. When the electricity is provided from ], this is a considerable advantage. However, if the electricity is produced from ] sources — as most electricity is — the relative advantage of the electric vehicle is substantially reduced. <ref>Tahara, K. ''et al.'' (2001) "Comparison of CO<sub>2</sub> Emissions from Alternative and Conventional Vehicles." ''World Resources Review'' '''13''':52-60 accessed 5 July 2006</ref> So, developing additional renewable energy sources is necessary for electric vehicles to further reduce net emissions. Still, the environmental impact of electricity production (''indirect emissions'') depends on the electricity production mix, and are usually considerably lower than the direct emissions of ICE vehicles. <ref>Van Mierlo, J., ''et al.'' (2003) "Environmental Damage Rating Analysis Tool as a Policy Instrument" ''20th International Electric Vehicle Symposium and Exposition'' (Long Beach, California) accessed 14 July 2006</ref> | |||

| In the EU, only 13% of the total population do not plan on owning a vehicle at all.<ref name=":28" /> | |||

| Another lifecycle input of electric vehicles differing from internal combustion vehicles is the large ]. Modern batteries have been shown to be able to outlast the vehicle they are used in. Batteries tested by ] have shown only minimal degradation in performance after 150,000 miles. BEVs do not require a fuel-burning engine and their support systems or the related maintenance, so they are often more reliable and require less maintenance. Although BEVs are uncommon, advances in battery technology have taken place in other markets such as for mobile phones, laptops, forklifts and ]s. Improvements to battery technology in such other markets make BEVs more practical. <!-- It would be good to link to, or provide, a table of efficiencies of various transport technologies, say space shuttle, aeroplane, rail-train, maglev, ICE car, HEV, BEV, bicycle, pedestrian. http://www.21stcenturysciencetech.com/articles/Summer03/maglev2.html --> | |||

| ==Performance== | |||

| ===Acceleration performance=== | |||

| ] - a limited production electric car capable of reaching 0-100km/h in 4.5 seconds]] | |||

| ===Acceleration and drivetrain design=== | |||

| Many of today's BEVs are capable of ] performance which exceeds that of conventional gasoline powered vehicles. Electric vehicles can utilize a direct motor-to-wheel configuration which increases the amount of available ]. Having multiple motors connected directly to the wheels allows for each of the wheels to be used for both propulsion and as braking systems, thereby increasing ]. In some cases, the motor can be housed directly in the wheel, such as in the ] design, which lowers the vehicle's ] and reduces the number of moving parts. When not fitted with an ], ], or ], electric vehicles have greater ] availability, directly accelerating the wheels. A gearless or single gear design in some BEVs eliminates the need for gear shifting, giving the such vehicles both smoother acceleration and braking, and allows higher torque at a wide range of ]. For example, the ] delivers ] acceleration despite a relatively modest 300 ], and a top speed of only around 100 miles per hour. Some ]-equipped drag racer BEVs, have simple two-speed transmissions to improve top speed. <ref>Hedlund, R. (2006) "The 100 Mile Per Hour Club" ''National Electric Drag Racing Association'' accessed 5 July 2006</ref> <ref>Hedlund, R. (2006) "The 125 Mile Per Hour Club" ''National Electric Drag Racing Association'' accessed 5 July 2006</ref> Larger vehicles, such as electric trains and land speed record vehicles, overcome this speed barrier by dramatically increasing the ]age of their power system. | |||

| ] | |||

| Electric motors can provide high ]s. Batteries can be designed to supply the electrical current needed to support these motors. Electric motors have a flat torque curve down to zero speed. For simplicity and reliability, most electric cars use fixed-ratio gearboxes and have no clutch. | |||

| Many electric cars have faster acceleration than average ICE cars, largely due to reduced drivetrain frictional losses and the more quickly-available torque of an electric motor.<ref>{{cite news |title=Gas-powered vs. Electric Cars: Which Is Faster? |url= https://auto.howstuffworks.com/gas-powered-vs-electric-cars-which-is-faster.htm |work=How Stuff Works |date=15 January 2019 |access-date=5 October 2020 |first=Cherise |last=Threewitt |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190322181830/https://auto.howstuffworks.com/gas-powered-vs-electric-cars-which-is-faster.htm |archive-date=22 March 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> However, NEVs may have a low acceleration due to their relatively weak motors. | |||

| Electric vehicles can also use a ] or next to the wheels; this is rare but claimed to be safer.<ref>{{Cite web|date=2020-05-20|title=In-wheel motors: The benefits of independent wheel torque control|url=https://www.e-motec.net/in-wheel-motors-beyond-torque-vectoring/|access-date=2021-08-06|website=E-Mobility Technology|language=en-US}}</ref> Electric vehicles that lack an ], ], or ] can have less drivetrain inertia. Some ]-equipped drag racer EVs have simple two-speed ]s to improve top speed.<ref>{{cite web |last=Hedlund |first=R. |date=November 2008 |title=The Roger Hedlund 100 MPH Club |publisher=National Electric Drag Racing Association |url= http://nedra.com/100mph_club.html |access-date=2009-04-25 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20101206091614/http://nedra.com/100mph_club.html |archive-date=6 December 2010 |url-status=live }}</ref> The concept electric supercar ] claims it can go from {{convert|0|-|97|km/h|mph|abbr=on|0}} in 2.5 seconds. Tesla claims the upcoming ] will go {{convert|0|-|60|mph|km/h|abbr=on|0}} in 1.9 seconds.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.businessinsider.com/tesla-roadster-goes-0-60-mph-less-than-2-seconds-base-version-2017-11 |title=The new Tesla Roadster can do 0–60 mph in less than 2 seconds – and that's just the base version |access-date=2019-04-22 |date=2017-11-17 |last1=DeBord |first1=Matthew |work=Business Insider |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20190207072312/https://www.businessinsider.com/tesla-roadster-goes-0-60-mph-less-than-2-seconds-base-version-2017-11 |archive-date=7 February 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Energy efficiency== | |||

| {{main|Electric car energy efficiency}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

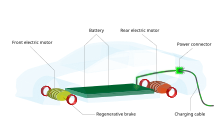

| Internal combustion engines have ] on efficiency, expressed as a fraction of energy used to propel the vehicle compared to energy produced by burning fuel. ]s effectively use only 15% of the fuel energy content to move the vehicle or to power accessories; ]s can reach on-board efficiency of 20%; electric vehicles convert over 77% of the electrical energy from the grid to power at the wheels.<ref>{{Cite web |title=All-Electric Vehicles |url=http://www.fueleconomy.gov/feg/evtech.shtml |access-date=2023-10-14 |website=www.fueleconomy.gov |language=en}}</ref><ref name=PEVs2>{{Cite book |title=Plug-In Electric Vehicles: What Role for Washington? |first=Saurin D. |last=Shah|year=2009 |publisher=The Brookings Institution |isbn=978-0-8157-0305-1 |edition=1st |chapter=2|pages=29, 37 and 43}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= https://cleantechnica.com/2018/03/10/electric-car-myth-buster-efficiency/ |title=Electric Car Myth Buster – Efficiency |date=2018-03-10 |website=CleanTechnica |language=en-US |access-date=2019-04-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190418004549/https://cleantechnica.com/2018/03/10/electric-car-myth-buster-efficiency/ |archive-date=18 April 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Electric motors are more efficient than internal combustion engines in converting stored energy into driving a vehicle. However, they are not equally efficient at all speeds. To allow for this, some cars with dual electric motors have one electric motor with a gear optimised for city speeds and the second electric motor with a gear optimised for highway speeds. The electronics select the motor that has the best efficiency for the current speed and acceleration.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://cleantechnica.com/2019/07/22/ev-transmissions-are-coming-and-its-a-good-thing/ |title=EV Transmissions Are Coming, And It's A Good Thing |first=Jennifer |last=Sensiba |work=CleanTechnica |date=2019-07-23 |access-date=2019-07-23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190723194905/https://cleantechnica.com/2019/07/22/ev-transmissions-are-coming-and-its-a-good-thing/ |archive-date=23 July 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> ], which is most common in electric vehicles, can recover as much as one fifth of the energy normally lost during braking.<ref name="TwoBillion"/><ref name="PEVs2"/> | |||

| ===Cabin heating and cooling=== | |||