| Revision as of 04:42, 22 July 2006 edit209.59.104.73 (talk) →Properties← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:52, 22 October 2024 edit undoRuslik0 (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Administrators54,749 editsm Reverted edit by 122.10.198.181 (talk) to last version by BlitterbugTag: Rollback | ||

| (347 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Inorganic compound group}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{About||the software development tool targeting the Symbian OS|Carbide.c++|the metallic compound commonly used in machine tools|Tungsten carbide|the town in West Virginia|Carbide, Wetzel County, West Virginia}} | |||

| In ], '''Carbide''' confusingly refers to three different things: | |||

| ]]] | |||

| 1. The ] C<sub>2</sub><sup>2−</sup>, or any salt of such. There is a ] ] between the two carbon atoms. | |||

| In ], a '''carbide''' usually describes a ] composed of ] and a metal. In ], '''carbiding''' or ] is the process for producing carbide coatings on a metal piece.<ref>{{Ullmann|title=Metals, Surface Treatment|first1=Helmut |last1=Kunst |first2=Brigitte |last2=Haase |first3=James C. |last3=Malloy |first4=Klaus |last4=Wittel |first5=Montia C. |last5=Nestler |first6=Andrew R. |last6=Nicoll |first7=Ulrich |last7=Erning |first8=Gerhard |last8=Rauscher|year=2006|doi=10.1002/14356007.a16_403.pub2}}</ref> | |||

| ==Interstitial / Metallic carbides== | |||

| 2. The ] C<sup>4−</sup>, or any salt of such. This ion is a very strong base, and will combine with four ]s to form ]: C<sup>4−</sup> + 4 H<sup>+</sup> → CH<sub>4</sub>. | |||

| ] ]]] | |||

| The carbides of the group 4, 5 and 6 transition metals (with the exception of chromium) are often described as ]s.<ref name="Greenwood" /> These carbides have metallic properties and are ]. Some exhibit a range of ], being a non-stoichiometric mixture of various carbides arising due to ]. Some of them, including ] and ], are important industrially and are used to coat metals in cutting tools.<ref name="Ettmayer">{{cite book|chapter=Carbides: transition metal solid state chemistry|author1=Peter Ettmayer |author2=Walter Lengauer |title=Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry| editor=R. Bruce King |year=1994 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-0-471-93620-6}}</ref> | |||

| The long-held view is that the carbon atoms fit into octahedral interstices in a close-packed metal lattice when the metal atom radius is greater than approximately 135 pm:<ref name="Greenwood" /> | |||

| 3. A carbon-containing alloy or doping of a metal or semiconductor, such as steel. | |||

| *When the metal atoms are ], (ccp), then filling all of the octahedral interstices with carbon achieves 1:1 stoichiometry with the ].<ref name=Zhu>{{Cite journal |last1=Zhu |first1=Qinqing |last2=Xiao |first2=Guorui |last3=Cui |first3=Yanwei |last4=Yang |first4=Wuzhang |last5=Wu |first5=Siqi |last6=Cao |first6=Guang-Han |last7=Ren |first7=Zhi |date=2021-10-15 |title=Anisotropic lattice expansion and enhancement of superconductivity induced by interstitial carbon doping in Rhenium |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925838821016996 |journal=Journal of Alloys and Compounds |language=en |volume=878 |pages=160290 |doi=10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160290 |issn=0925-8388}}</ref> | |||

| ==Examples== | |||

| *When the metal atoms are ], (hcp), as the octahedral interstices lie directly opposite each other on either side of the layer of metal atoms, filling only one of these with carbon achieves 2:1 stoichiometry with the CdI<sub>2</sub> structure.<ref name=Zhu/> | |||

| The following table<ref name="Greenwood" /><ref name="Ettmayer" /> shows structures of the metals and their carbides. (N.B. the body centered cubic structure adopted by vanadium, niobium, tantalum, chromium, molybdenum and tungsten is not a close-packed lattice.) The notation "h/2" refers to the M<sub>2</sub>C type structure described above, which is only an approximate description of the actual structures. The simple view that the lattice of the pure metal "absorbs" carbon atoms can be seen to be untrue as the packing of the metal atom lattice in the carbides is different from the packing in the pure metal, although it is technically correct that the carbon atoms fit into the octahedral interstices of a close-packed metal lattice. | |||

| * ] (Na<sub>2</sub>C<sub>2</sub>) | |||

| * ] (SiC) | |||

| * ] (often called simply ''carbide'') | |||

| * ] (iron carbide; Fe<sub>3</sub>C) | |||

| See ] for a bigger list. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" | |||

| ==Types of carbides== | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Metal | |||

| ! Structure of pure metal | |||

| ! Metallic <br />radius (pm) | |||

| ! MC <br />metal atom packing | |||

| ! MC structure | |||

| ! M<sub>2</sub>C <br />metal atom packing | |||

| ! M<sub>2</sub>C structure | |||

| ! Other carbides | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | hcp | |||

| | 147 | |||

| | ccp | |||

| | rock salt | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | hcp | |||

| | 160 | |||

| | ccp | |||

| | rock salt | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | hcp | |||

| | 159 | |||

| | ccp | |||

| | rock salt | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 134 | |||

| | ccp | |||

| | rock salt | |||

| | hcp | |||

| | h/2 | |||

| | V<sub>4</sub>C<sub>3</sub> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | bcc | |||

| | 146 | |||

| | ccp | |||

| | rock salt | |||

| | hcp | |||

| | h/2 | |||

| | Nb<sub>4</sub>C<sub>3</sub> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | bcc | |||

| | 146 | |||

| | ccp | |||

| | rock salt | |||

| | hcp | |||

| | h/2 | |||

| | Ta<sub>4</sub>C<sub>3</sub> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | bcc | |||

| | 128 | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |Cr<sub>23</sub>C<sub>6</sub>, Cr<sub>3</sub>C,<br /> Cr<sub>7</sub>C<sub>3</sub>, Cr<sub>3</sub>C<sub>2</sub> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | bcc | |||

| | 139 | |||

| | | |||

| | hexagonal | |||

| | hcp | |||

| | h/2 | |||

| | Mo<sub>3</sub>C<sub>2</sub> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | bcc | |||

| | 139 | |||

| | | |||

| | hexagonal | |||

| | hcp | |||

| | h/2 | |||

| | | |||

| |} | |||

| For a long time the ] phases were believed to be disordered with a random filling of the interstices, however short and longer range ordering has been detected.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Order and disorder in transition metal carbides and nitrides: experimental and theoretical aspects|author1=C.H. de Novion |author2=J.P. Landesman |journal=Pure Appl. Chem.|volume=57|issue=10|year=1985|page=1391|doi=10.1351/pac198557101391|s2cid=59467042 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ===Methides=== | |||

| Iron forms a number of carbides, {{chem2|Fe3C}}, {{chem2|Fe7C3}} and {{chem2|Fe2C}}. The best known is ], Fe<sub>3</sub>C, which is present in steels. These carbides are more reactive than the interstitial carbides; for example, the carbides of Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni are all hydrolysed by dilute acids and sometimes by water, to give a mixture of hydrogen and hydrocarbons. These compounds share features with both the inert interstitials and the more reactive salt-like carbides.<ref name="Greenwood" /> | |||

| A salt corresponding to the ion C<sup>4−</sup> can be called a '''methide'''. Methides commonly react with water to form ], however reactions with other substances are common. | |||

| Some metals, such as ] and ], are believed not to form carbides under any circumstances.<ref name="percy">{{cite book|author=John Percy|page=67|year=1870|url=https://archive.org/stream/metallurgyleadi01percgoog#page/n86/mode/2up/ |title=The Metallurgy of Lead, including Desiverization and Cupellation|publisher= J. Murray|place=London|access-date=2013-04-06|author-link=John Percy (metallurgist)}}</ref> There exists however a mixed titanium-tin carbide, which is a two-dimensional conductor.<ref>{{cite journal|author1=Y. C. Zhou |author2=H. Y. Dong |author3=B. H. Yu |year=2000|title=Development of two-dimensional titanium tin carbide (Ti2SnC) plates based on the electronic structure investigation|journal=Materials Research Innovations |volume=4|issue=1|pages=36–41|doi=10.1007/s100190000065|bibcode=2000MatRI...4...36Z |s2cid=135756713 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Acetylides=== | |||

| ==Chemical classification of carbides== | |||

| A salt corresponding to the ion C<sub>2</sub><sup>2−</sup> can be called an ]. Acetylides commonly react with water to form ]. | |||

| Carbides can be generally classified by the chemical bonds type as follows: | |||

| # salt-like (ionic), | |||

| # ]s, | |||

| # ]s, and | |||

| # "intermediate" ] carbides. | |||

| Examples include ] (CaC<sub>2</sub>), ] (SiC), ] (WC; often called, simply, ''carbide'' when referring to machine tooling), and ] (Fe<sub>3</sub>C),<ref name="Greenwood">{{Greenwood&Earnshaw1st|pages=318–22}}</ref> each used in key industrial applications. The naming of ionic carbides is not systematic. | |||

| ===Salt-like / saline / ionic carbides=== | |||

| ===Compounds that do not fit usual notions of valence or stoichiometry=== | |||

| Salt-like carbides are composed of highly electropositive elements such as the ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s, and ] (], ], and ]). ] from group 13 forms ], but ], ], and ] do not. These materials feature isolated carbon centers, often described as "C<sup>4−</sup>", in the methanides or methides; two-atom units, "{{chem2|C2(2-)}}", in the ]s; and three-atom units, "{{chem2|C3(4-)}}", in the allylides.<ref name="Greenwood" /> The ], prepared from vapour of potassium and graphite, and the alkali metal derivatives of C<sub>60</sub> are not usually classified as carbides.<ref>Shriver and Atkins — Inorganic Chemistry</ref> | |||

| === |

====Methanides==== | ||

| Methanides are a subset of carbides distinguished by their tendency to decompose in water producing ]. Three examples are ] {{chem2|Al4C3}}, ] {{chem2|Mg2C}}<ref>{{cite journal|title=Synthesis of Mg2C: A Magnesium Methanide|author1=O.O. Kurakevych |author2=T.A. Strobel |author3=D.Y. Kim |author4=G.D. Cody |volume =52|issue=34|year=2013|pages=8930–8933|journal=Angewandte Chemie International Edition|doi=10.1002/anie.201303463|pmid = 23824698}}</ref> and ] {{chem2|Be2C}}. | |||

| Transition metal carbides are not saline: their reaction with water is very slow and is usually neglected. For example, depending on surface porosity, 5–30 atomic layers of ] are hydrolyzed, forming ] within 5 minutes at ambient conditions, following by saturation of the reaction.<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF00780135|title=Reaction of titanium carbide with water|author1=A. I. Avgustinik |author2=G. V. Drozdetskaya |author3=S. S. Ordan'yan |volume =6|issue=6|year=1967|pages=470–473|journal=Powder Metallurgy and Metal Ceramics|doi=10.1007/BF00780135|s2cid=134209836}}</ref> | |||

| These are formed with metals; they often have metallic properties. | |||

| Note that methanide in this context is a trivial historical name. According to the IUPAC systematic naming conventions, a compound such as NaCH<sub>3</sub> would be termed a "methanide", although this compound is often called methylsodium.<ref name="WeissCorbelin1990">{{cite journal|last1=Weiss|first1=Erwin|last2=Corbelin|first2=Siegfried|last3=Cockcroft|first3=Jeremy Karl|last4=Fitch|first4=Andrew Nicholas|title=Über Metallalkyl- und -aryl-Verbindungen, 44 Darstellung und Struktur von Methylnatrium. Strukturbestimmung an NaCD3-Pulvern bei 1.5 und 300 K durch Neutronen- und Synchrotronstrahlenbeugung|journal=Chemische Berichte|volume=123|issue=8|year=1990|pages=1629–1634|issn=0009-2940|doi=10.1002/cber.19901230807}}</ref> See ] for more information about the {{chem2|CH3-}} anion. | |||

| ===Some covalent compounds=== | |||

| ====Acetylides/ethynides==== | |||

| Elements that have similar ] form mainly covalent compounds. For example, the compound ] is mostly covalent; it has similar structure to ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Several carbides are assumed to be salts of the ] {{chem2|C2(2–)}} (also called percarbide, by analogy with ]), which has a ] between the two carbon atoms. Alkali metals, alkaline earth metals, and ] form acetylides, for example, ] Na<sub>2</sub>C<sub>2</sub>, ] CaC<sub>2</sub>, and ].<ref name="Greenwood" /> Lanthanides also form carbides (sesquicarbides, see below) with formula M<sub>2</sub>C<sub>3</sub>. Metals from group 11 also tend to form acetylides, such as ] and ]. Carbides of the ], which have stoichiometry MC<sub>2</sub> and M<sub>2</sub>C<sub>3</sub>, are also described as salt-like derivatives of {{chem2|C2(2-)}}. | |||

| The C–C triple bond length ranges from 119.2 pm in CaC<sub>2</sub> (similar to ethyne), to 130.3 pm in ] and 134 pm in ]. The bonding in ] has been described in terms of La<sup>III</sup> with the extra electron delocalised into the antibonding orbital on {{chem2|C2(2-)}}, explaining the metallic conduction.<ref name="Greenwood" /> | |||

| ==Properties== | |||

| ====Allylides==== | |||

| Under conditions of ], ] carbides react strongly with ] to form metal ]s or ] and flammable ] gas, e.g.: | |||

| The ] {{chem2|C3(4−)}}, sometimes called '''allylide''', is found in {{chem2|Li4C3}} and {{chem2|Mg2C3}}. The ion is linear and is ] with {{CO2}}.<ref name="Greenwood" /> The C–C distance in Mg<sub>2</sub>C<sub>3</sub> is 133.2 pm.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Crystal Structure of Magnesium Sesquicarbide|doi=10.1021/ic00041a018|author1=Fjellvag H. |author2=Pavel K. |journal=Inorg. Chem. |year=1992|volume=31|page=3260|issue=15}}</ref> {{chem2|Mg2C3}} yields ], CH<sub>3</sub>CCH, and ], CH<sub>2</sub>CCH<sub>2</sub>, on hydrolysis, which was the first indication that it contains {{chem2|C3(4−)}}. | |||

| ===Covalent carbides=== | |||

| : CaC<sub>2</sub> + 2H<sub>2</sub>O → C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>2</sub> + Ca(OH)<sub>2</sub> | |||

| The carbides of silicon and ] are described as "covalent carbides", although virtually all compounds of carbon exhibit some covalent character. ] has two similar crystalline forms, which are both related to the diamond structure.<ref name="Greenwood" /> ], B<sub>4</sub>C, on the other hand, has an unusual structure which includes icosahedral boron units linked by carbon atoms. In this respect ] is similar to the boron rich ]s. Both silicon carbide (also known as ''carborundum'') and boron carbide are very hard materials and ]. Both materials are important industrially. Boron also forms other covalent carbides, such as B<sub>25</sub>C. | |||

| marlon | |||

| ], an important source of portable subterranean ] for ] and ], and in the past for ] lamps, work through on-demand production and ] of ] by the metered addition of ] to calcium carbide. | |||

| ===Molecular carbides=== | |||

| ], using acetylene gas generated from carbide, was used in some homes before the ] came into widespread use. It was also the main source of lighting on ]s and carriages before the widespread availability of electric lamps and batteries. The carbide was prepared industrially by the action of an ] on a mixture of ] and ]. | |||

| (2+)}}, containing a carbon-gold core]] | |||

| Metal complexes containing C are known as ]es. Most common are carbon-centered octahedral clusters, such as {{chem2|]3)6](2+)}} (where "Ph" represents a ]) and <sup>2−</sup>. Similar species are known for the ]s and the early metal halides. A few terminal carbides have been isolated, such as {{chem2|}}. | |||

| ]s (or "met-cars") are stable clusters with the general formula {{chem2|M8C12}} where M is a transition metal (Ti, Zr, V, etc.). | |||

| In the northern, eastern and southern regions of the ] and in ] carbide is used as fireworks. To create an explosion, carbide and water are put in a milk churn with a lid. Ignition is usually done with a torch. Some villages in the Netherlands fire multiple milk churns in a row as an oldyear tradition. | |||

| == |

==Related materials== | ||

| In addition to the carbides, other groups of related carbon compounds exist:<ref name="Greenwood" /> | |||

| * | |||

| *]s | |||

| * | |||

| *alkali metal ] | |||

| *], where the metal atom is encapsulated within a fullerene molecule | |||

| *metallacarbohedrenes (met-cars) which are cluster compounds containing C<sub>2</sub> units. | |||

| *], where gas chlorination of metallic carbides removes metal molecules to form a highly porous, near-pure carbon material capable of high-density energy storage. | |||

| *]es. | |||

| * two-dimensional transition metal carbides: ] | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{reflist|25em}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Carbides}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Inorganic compounds of carbon}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Monatomic anion compounds}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:52, 22 October 2024

Inorganic compound group For the software development tool targeting the Symbian OS, see Carbide.c++. For the metallic compound commonly used in machine tools, see Tungsten carbide. For the town in West Virginia, see Carbide, Wetzel County, West Virginia.

In chemistry, a carbide usually describes a compound composed of carbon and a metal. In metallurgy, carbiding or carburizing is the process for producing carbide coatings on a metal piece.

Interstitial / Metallic carbides

The carbides of the group 4, 5 and 6 transition metals (with the exception of chromium) are often described as interstitial compounds. These carbides have metallic properties and are refractory. Some exhibit a range of stoichiometries, being a non-stoichiometric mixture of various carbides arising due to crystal defects. Some of them, including titanium carbide and tungsten carbide, are important industrially and are used to coat metals in cutting tools.

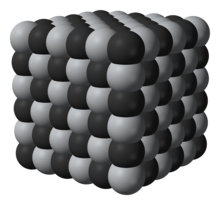

The long-held view is that the carbon atoms fit into octahedral interstices in a close-packed metal lattice when the metal atom radius is greater than approximately 135 pm:

- When the metal atoms are cubic close-packed, (ccp), then filling all of the octahedral interstices with carbon achieves 1:1 stoichiometry with the rock salt structure.

- When the metal atoms are hexagonal close-packed, (hcp), as the octahedral interstices lie directly opposite each other on either side of the layer of metal atoms, filling only one of these with carbon achieves 2:1 stoichiometry with the CdI2 structure.

The following table shows structures of the metals and their carbides. (N.B. the body centered cubic structure adopted by vanadium, niobium, tantalum, chromium, molybdenum and tungsten is not a close-packed lattice.) The notation "h/2" refers to the M2C type structure described above, which is only an approximate description of the actual structures. The simple view that the lattice of the pure metal "absorbs" carbon atoms can be seen to be untrue as the packing of the metal atom lattice in the carbides is different from the packing in the pure metal, although it is technically correct that the carbon atoms fit into the octahedral interstices of a close-packed metal lattice.

| Metal | Structure of pure metal | Metallic radius (pm) |

MC metal atom packing |

MC structure | M2C metal atom packing |

M2C structure | Other carbides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| titanium | hcp | 147 | ccp | rock salt | |||

| zirconium | hcp | 160 | ccp | rock salt | |||

| hafnium | hcp | 159 | ccp | rock salt | |||

| vanadium | bcc | 134 | ccp | rock salt | hcp | h/2 | V4C3 |

| niobium | bcc | 146 | ccp | rock salt | hcp | h/2 | Nb4C3 |

| tantalum | bcc | 146 | ccp | rock salt | hcp | h/2 | Ta4C3 |

| chromium | bcc | 128 | Cr23C6, Cr3C, Cr7C3, Cr3C2 | ||||

| molybdenum | bcc | 139 | hexagonal | hcp | h/2 | Mo3C2 | |

| tungsten | bcc | 139 | hexagonal | hcp | h/2 |

For a long time the non-stoichiometric phases were believed to be disordered with a random filling of the interstices, however short and longer range ordering has been detected.

Iron forms a number of carbides, Fe3C, Fe7C3 and Fe2C. The best known is cementite, Fe3C, which is present in steels. These carbides are more reactive than the interstitial carbides; for example, the carbides of Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni are all hydrolysed by dilute acids and sometimes by water, to give a mixture of hydrogen and hydrocarbons. These compounds share features with both the inert interstitials and the more reactive salt-like carbides.

Some metals, such as lead and tin, are believed not to form carbides under any circumstances. There exists however a mixed titanium-tin carbide, which is a two-dimensional conductor.

Chemical classification of carbides

Carbides can be generally classified by the chemical bonds type as follows:

- salt-like (ionic),

- covalent compounds,

- interstitial compounds, and

- "intermediate" transition metal carbides.

Examples include calcium carbide (CaC2), silicon carbide (SiC), tungsten carbide (WC; often called, simply, carbide when referring to machine tooling), and cementite (Fe3C), each used in key industrial applications. The naming of ionic carbides is not systematic.

Salt-like / saline / ionic carbides

Salt-like carbides are composed of highly electropositive elements such as the alkali metals, alkaline earth metals, lanthanides, actinides, and group 3 metals (scandium, yttrium, and lutetium). Aluminium from group 13 forms carbides, but gallium, indium, and thallium do not. These materials feature isolated carbon centers, often described as "C", in the methanides or methides; two-atom units, "C2−2", in the acetylides; and three-atom units, "C4−3", in the allylides. The graphite intercalation compound KC8, prepared from vapour of potassium and graphite, and the alkali metal derivatives of C60 are not usually classified as carbides.

Methanides

Methanides are a subset of carbides distinguished by their tendency to decompose in water producing methane. Three examples are aluminium carbide Al4C3, magnesium carbide Mg2C and beryllium carbide Be2C.

Transition metal carbides are not saline: their reaction with water is very slow and is usually neglected. For example, depending on surface porosity, 5–30 atomic layers of titanium carbide are hydrolyzed, forming methane within 5 minutes at ambient conditions, following by saturation of the reaction.

Note that methanide in this context is a trivial historical name. According to the IUPAC systematic naming conventions, a compound such as NaCH3 would be termed a "methanide", although this compound is often called methylsodium. See Methyl group#Methyl anion for more information about the CH−3 anion.

Acetylides/ethynides

Several carbides are assumed to be salts of the acetylide anion C2−2 (also called percarbide, by analogy with peroxide), which has a triple bond between the two carbon atoms. Alkali metals, alkaline earth metals, and lanthanoid metals form acetylides, for example, sodium carbide Na2C2, calcium carbide CaC2, and LaC2. Lanthanides also form carbides (sesquicarbides, see below) with formula M2C3. Metals from group 11 also tend to form acetylides, such as copper(I) acetylide and silver acetylide. Carbides of the actinide elements, which have stoichiometry MC2 and M2C3, are also described as salt-like derivatives of C2−2.

The C–C triple bond length ranges from 119.2 pm in CaC2 (similar to ethyne), to 130.3 pm in LaC2 and 134 pm in UC2. The bonding in LaC2 has been described in terms of La with the extra electron delocalised into the antibonding orbital on C2−2, explaining the metallic conduction.

Allylides

The polyatomic ion C4−3, sometimes called allylide, is found in Li4C3 and Mg2C3. The ion is linear and is isoelectronic with CO2. The C–C distance in Mg2C3 is 133.2 pm. Mg2C3 yields methylacetylene, CH3CCH, and propadiene, CH2CCH2, on hydrolysis, which was the first indication that it contains C4−3.

Covalent carbides

The carbides of silicon and boron are described as "covalent carbides", although virtually all compounds of carbon exhibit some covalent character. Silicon carbide has two similar crystalline forms, which are both related to the diamond structure. Boron carbide, B4C, on the other hand, has an unusual structure which includes icosahedral boron units linked by carbon atoms. In this respect boron carbide is similar to the boron rich borides. Both silicon carbide (also known as carborundum) and boron carbide are very hard materials and refractory. Both materials are important industrially. Boron also forms other covalent carbides, such as B25C.

Molecular carbides

Metal complexes containing C are known as metal carbido complexes. Most common are carbon-centered octahedral clusters, such as [Au6C(PPh3)6] (where "Ph" represents a phenyl group) and . Similar species are known for the metal carbonyls and the early metal halides. A few terminal carbides have been isolated, such as [CRuCl2{P(C6H11)3}2].

Metallocarbohedrynes (or "met-cars") are stable clusters with the general formula M8C12 where M is a transition metal (Ti, Zr, V, etc.).

Related materials

In addition to the carbides, other groups of related carbon compounds exist:

- graphite intercalation compounds

- alkali metal fullerides

- endohedral fullerenes, where the metal atom is encapsulated within a fullerene molecule

- metallacarbohedrenes (met-cars) which are cluster compounds containing C2 units.

- tunable nanoporous carbon, where gas chlorination of metallic carbides removes metal molecules to form a highly porous, near-pure carbon material capable of high-density energy storage.

- transition metal carbene complexes.

- two-dimensional transition metal carbides: MXenes

See also

References

- Kunst, Helmut; Haase, Brigitte; Malloy, James C.; Wittel, Klaus; Nestler, Montia C.; Nicoll, Andrew R.; Erning, Ulrich; Rauscher, Gerhard (2006). "Metals, Surface Treatment". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_403.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 318–22. ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4.

- ^ Peter Ettmayer; Walter Lengauer (1994). "Carbides: transition metal solid state chemistry". In R. Bruce King (ed.). Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-93620-6.

- ^ Zhu, Qinqing; Xiao, Guorui; Cui, Yanwei; Yang, Wuzhang; Wu, Siqi; Cao, Guang-Han; Ren, Zhi (2021-10-15). "Anisotropic lattice expansion and enhancement of superconductivity induced by interstitial carbon doping in Rhenium". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 878: 160290. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160290. ISSN 0925-8388.

- C.H. de Novion; J.P. Landesman (1985). "Order and disorder in transition metal carbides and nitrides: experimental and theoretical aspects". Pure Appl. Chem. 57 (10): 1391. doi:10.1351/pac198557101391. S2CID 59467042.

- John Percy (1870). The Metallurgy of Lead, including Desiverization and Cupellation. London: J. Murray. p. 67. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Y. C. Zhou; H. Y. Dong; B. H. Yu (2000). "Development of two-dimensional titanium tin carbide (Ti2SnC) plates based on the electronic structure investigation". Materials Research Innovations. 4 (1): 36–41. Bibcode:2000MatRI...4...36Z. doi:10.1007/s100190000065. S2CID 135756713.

- Shriver and Atkins — Inorganic Chemistry

- O.O. Kurakevych; T.A. Strobel; D.Y. Kim; G.D. Cody (2013). "Synthesis of Mg2C: A Magnesium Methanide". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 52 (34): 8930–8933. doi:10.1002/anie.201303463. PMID 23824698.

- A. I. Avgustinik; G. V. Drozdetskaya; S. S. Ordan'yan (1967). "Reaction of titanium carbide with water". Powder Metallurgy and Metal Ceramics. 6 (6): 470–473. doi:10.1007/BF00780135. S2CID 134209836.

- Weiss, Erwin; Corbelin, Siegfried; Cockcroft, Jeremy Karl; Fitch, Andrew Nicholas (1990). "Über Metallalkyl- und -aryl-Verbindungen, 44 Darstellung und Struktur von Methylnatrium. Strukturbestimmung an NaCD3-Pulvern bei 1.5 und 300 K durch Neutronen- und Synchrotronstrahlenbeugung". Chemische Berichte. 123 (8): 1629–1634. doi:10.1002/cber.19901230807. ISSN 0009-2940.

- Fjellvag H.; Pavel K. (1992). "Crystal Structure of Magnesium Sesquicarbide". Inorg. Chem. 31 (15): 3260. doi:10.1021/ic00041a018.

| Salts and covalent derivatives of the carbide ion | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Inorganic compounds of carbon and related ions | |

|---|---|

| Compounds | |

| Carbon ions | |

| Nanostructures | |

| Oxides and related | |

| Monatomic anion compounds | |

|---|---|

| Group 1 | |

| Group 13 | |

| Group 14 | |

| Group 15 (Pnictides) | |

| Group 16 (Chalcogenides) | |

| Group 17 (Halides) | |