| Revision as of 06:47, 22 July 2015 editDoc James (talk | contribs)Administrators312,257 edits wording← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:33, 15 December 2024 edit undoWin8x (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers4,168 edits Reverted 1 edit by Monnyandscotty (talk): That's not trueTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Natural changes in the human female reproductive system}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2014}} | |||

| {{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} | |||

| {{See also|Menstruation|Menstruation (mammal)}} | |||

| {{About|biological aspects of the reproductive cycle in humans|information specific to monthly periods|menstruation|and|menstruation (mammal)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2021}} | |||

| <!-- Definition and symptoms --> | |||

| ] | |||

| The '''menstrual cycle''' is the regular natural changes that occurs in the ] and ] that make ] possible.<ref name=Silverthorn>{{cite book |last1 = Silverthorn |first1 = Dee Unglaub |title = Human Physiology: An Integrated Approach |edition=6th |publisher = Pearson Education, Inc. |location = Glenview, IL |year = 2013 | isbn = 0-321-75007-1 |pages=850–890}}</ref><ref name=Sherwood>{{cite book |last1 = Sherwood |first1 = Laurelee |title = Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems | edition=8th |publisher = Cengage |location = Belmont, CA | year = 2013 |isbn = 1-111-57743-9 |pages=735–794}}</ref> The cycle is required for the production of eggs, and for the preparation of the uterus for ].<ref name=Silverthorn /> Up to 80% of women report having some symptoms during the one to two weeks prior to ].<ref name=AFP2011/> Common symptoms include ], tender breasts, bloating, feeling tired, irritability, and mood changes.<ref name=Women2014PMS>{{cite web|title=Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) fact sheet|url=http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/premenstrual-syndrome.html|website=Office on Women's Health|accessdate=23 June 2015|date=December 23, 2014}}</ref> These symptoms interfere with normal life and therefore qualify as ] in 20 to 30% of women.<!-- <ref name=AFP2011/> --> In 3 to 8%, they are severe.<ref name=AFP2011>{{cite journal|last1=Biggs|first1=WS|last2=Demuth|first2=RH|title=Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.|journal=American family physician|date=15 October 2011|volume=84|issue=8|pages=918–24|pmid=22010771}}</ref> | |||

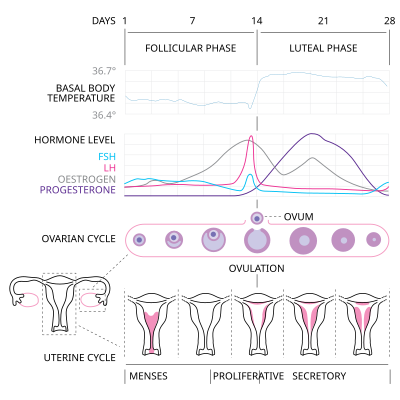

| The '''menstrual cycle''' is a series of natural changes in ] production and the structures of the ] and ] of the ] that makes ] possible. The ovarian cycle controls the production and release of ] and the cyclic release of ] and ]. The uterine cycle governs the preparation and maintenance of the lining of the uterus (womb) to receive an ]. These cycles are concurrent and coordinated, normally last between 21 and 35 days, with a ] length of 28 days. ] (the onset of the first period) usually occurs around the age of 12 years; menstrual cycles continue for about 30–45 years. | |||

| Naturally occurring hormones drive the cycles; the cyclical rise and fall of the ] prompts the production and growth of ]s (immature egg cells). The hormone estrogen stimulates the uterus lining (]) to thicken to accommodate an embryo should ] occur. The blood supply of the thickened lining provides ]s to a successfully ] embryo. If implantation does not occur, the lining breaks down and blood is released. Triggered by falling progesterone levels, ] (a "period", in common parlance) is the cyclical shedding of the lining, and is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred. | |||

| <!-- Frequency --> | |||

| The first period usually begins between twelve and fifteen years of age, a point in time known as ].<ref name=Jones2011>{{cite book|title=Women's Gynecologic Health|date=2011|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Publishers|isbn=9780763756376|page=94|url=https://books.google.ca/books?id=pj_ourS3PBMC&pg=PA94}}</ref> They may occationally start as early as eight and still be normal.<ref name=Women2014Men>{{cite web|title=Menstruation and the menstrual cycle fact sheet|url=http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/menstruation.html|website=Office of Women's Health|accessdate=25 June 2015|date=December 23, 2014}}</ref> The average age of the first period is generally later in the ] and earlier in ].<!-- <ref name=Diaz2006/> --> The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women and 21 to 31 days in adults (an average of 28 days).<ref name=Women2014Men/><ref name=Diaz2006>{{cite journal|last1=American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on|first1=Adolescence|last2=American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health|first2=Care|last3=Diaz|first3=A|last4=Laufer|first4=MR|last5=Breech|first5=LL|title=Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign.|journal=Pediatrics|date=November 2006|volume=118|issue=5|pages=2245–50|pmid=17079600}}</ref> Menstruation stops occurring after ] which usually occurs between 45 and 55 years of age.<ref name=NIH2013Def>{{cite web|title=Menopause: Overview|url=http://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/menopause/Pages/default.aspx|website=http://www.nichd.nih.gov|accessdate=8 March 2015|date=2013-06-28}}</ref> Bleeding usually lasts around 2 to 7 days.<ref name=Women2014Men/> | |||

| Each cycle occurs in phases based on events either in the ovary (ovarian cycle) or in the uterus (uterine cycle). The ovarian cycle consists of the ], ], and the ]; the uterine cycle consists of the menstrual, proliferative and secretory phases. Day one of the menstrual cycle is the first day of the period, which lasts for about five days. Around day fourteen, an egg is usually released from the ovary. | |||

| <!-- Mechanism --> | |||

| The menstrual cycle is governed by hormonal changes.<ref name=Women2014Men/> These changes can be altered by using ] to prevent pregnancy.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Klump KL, Keel PK, Racine SE, Burt SA, Burt AS, Neale M, Sisk CL, Boker S, Hu JY | title = The interactive effects of estrogen and progesterone on changes in emotional eating across the menstrual cycle | journal = J Abnorm Psychol | volume = 122 | issue = 1 | pages = 131–7 | date = February 2013 | pmid = 22889242 | doi = 10.1037/a0029524 }}</ref> Each cycle can be divided into three phases based on events in the ovary (ovarian cycle) or in the uterus (uterine cycle).<ref name=Silverthorn /> The ovarian cycle consists of the ], ], and ] whereas the uterine cycle is divided into ], proliferative phase, and secretory phase. | |||

| The menstrual cycle can cause some women to experience ] with symptoms that may include ], and ]. More severe symptoms that affect daily living are classed as ], and are experienced by 3–8% of women. During the first few days of menstruation some women experience ] that can spread from the abdomen to the back and upper thighs. The menstrual cycle can be modified by ]. | |||

| Stimulated by gradually increasing amounts of ] in the follicular phase, discharges of blood (menses) flow stop, and the ] of the uterus thickens. ] in the ovary begin developing under the influence of a complex interplay of hormones, and after several days one or occasionally two become dominant (non-dominant follicles shrink and die). Approximately mid-cycle, 24–36 hours after the ] (LH) surges, the dominant follicle releases an ], in an event called ovulation. After ovulation, the egg only lives for 24 hours or less without fertilization while the remains of the dominant follicle in the ovary become a ]; this body has a primary function of producing large amounts of ]. Under the influence of progesterone, the ] changes to prepare for potential ] of an embryo to establish a pregnancy. If implantation does not occur within approximately two weeks, the corpus luteum will involute, causing a sharp drops in levels of both progesterone and estrogen. The hormone drop causes the uterus to shed its lining in a process termed menstruation. Menstruation also occur in some other animals including ], ], and other ] such as ] and ].<ref name=Kris2013>{{cite book|author1=Kristin H. Lopez|title=Human Reproductive Biology|date=2013|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=9780123821850|page=53|url=https://books.google.ca/books?id=M4kEdSnS-pkC&pg=PA53}}</ref> | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | |||

| == |

== Cycles and phases == | ||

| ] builds up and |

] | ||

| The average age of menarche is 12–15.<ref name=Jones2011/><ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Karapanou | first1 = O. | last2 = Papadimitriou | first2 = A. | title = Determinants of menarche. | journal = Reprod Biol Endocrinol | volume = 8 | issue = | pages = 115 | month = | year = 2010 | doi = 10.1186/1477-7827-8-115 | PMID = 20920296 }}</ref> They may occationally start as early as eight and still be normal.<ref name=Women2014Men/> This first period often occurs later in the ] than the ].<ref name=Diaz2006/> | |||

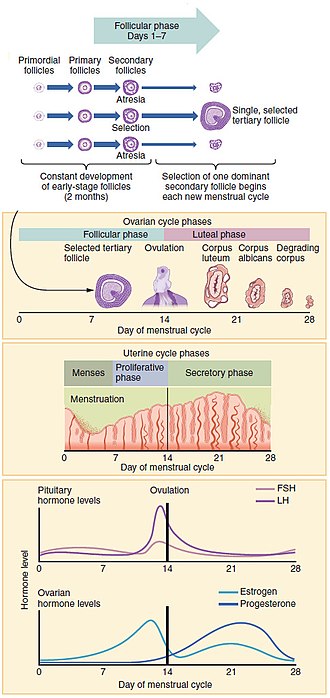

| The menstrual cycle encompasses the ovarian and uterine cycles. The ovarian cycle describes changes that occur in the ] of the ],<ref name="pmid29544627">{{cite journal|vauthors=Richards JS|date=2018|title=The ovarian cycle|journal=Vitamins and Hormones|volume=107|issue=|pages=1–25|doi=10.1016/bs.vh.2018.01.009|isbn=978-0-128-14359-9|pmid=29544627 |type= Review}}</ref> whereas the uterine cycle describes changes in the ] of the uterus. Both cycles can be divided into phases. The ovarian cycle consists of alternating ] and ]s, and the uterine cycle consists of the ], the proliferative phase, and the secretory phase.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=944}} The menstrual cycle is controlled by the ] in the brain, and the ] at the base of the brain. The hypothalamus releases ] (GnRH), which causes the nearby anterior pituitary to release ] (FSH) and ] (LH). Before ], GnRH is released in low steady quantities and at a steady rate. After puberty, GnRH is released in large pulses, and the frequency and magnitude of these determine how much FSH and LH are produced by the pituitary.{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=42}} | |||

| The average age of menarche is about 12.5 years in the ],<ref>{{cite journal | author = Anderson SE, Dallal GE, Must A | title = Relative weight and race influence average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of US girls studied 25 years apart | journal = Pediatrics | volume = 111 | issue = 4 Pt 1 | pages = 844–50 | date = April 2003 | pmid = 12671122 | doi = 10.1542/peds.111.4.844 }}</ref> 12.7 in ],<ref>{{cite journal | author = Al-Sahab B, Ardern CI, Hamadeh MJ, Tamim H | title = Age at menarche in Canada: results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children & Youth | journal = BMC Public Health | volume = 10 | issue = | pages = 736 | year = 2010 | pmid = 21110899 | pmc = 3001737 | doi = 10.1186/1471-2458-10-736 }}</ref> 12.9 in the ]<ref>{{cite book|author=Hamilton-Fairley, Diana|title=Lecture notes on obstetrics and gynaecology|edition=2nd|year=2004|origyear=1999|publisher=Blackwell|url=http://vstudentworld.yolasite.com/resources/final_yr/gynae_obs/Hamilton%20Fairley%20Obstetrics%20and%20Gynaecology%20Lecture%20Notes%202%20Ed.pdf|format=pdf|page=29|isbn=1-4051-2066-5}}</ref> and 13.1 years in ].<ref>{{cite journal | author = Macgússon TE | title = Age at menarche in Iceland | journal = Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. | volume = 48 | issue = 4 | pages = 511–4 | date = May 1978 | pmid = 655271 | doi = 10.1002/ajpa.1330480410 }}</ref> Factors such as genetics, diet and overall health can affect timing.<ref name=age>{{cite web | url = http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/menstruation.cfm#f | title = At what age does a girl get her first period? | publisher = National Women's Health Information Center | accessdate = 20 November 2011}}</ref> | |||

| Measured from the first day of one menstruation to the first day of the next, the length of a menstrual cycle varies but has a ] length of 28 days.<ref name="Reed2018" /> The cycle is often less regular at the beginning and end of a woman's reproductive life.<ref name="Reed2018" /> At puberty, a child's body begins to mature into an adult body capable of ]; the first period (called ]) occurs at around 12 years of age and continues for about 30–45 years.{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=40}}<ref name="pmid29261991">{{cite journal |vauthors=Lacroix AE, Gondal H, Langaker MD |title=Physiology, menarche |journal=StatPearls . Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing |year=2020 |pmid=29261991|type= Review }}</ref> Menstrual cycles end at ], which is usually between 45 and 55 years of age.{{sfn | Rodriguez-Landa | 2017 | p=8}}<ref name="pmid26703478" /> | |||

| The cessation of menstrual cycles at the end of a woman's reproductive period is termed ]. The average age of menopause in women is 52 years, with anywhere between 45 and 55 being common. Menopause before age 45 is considered ''premature'' in industrialised countries.<ref>{{cite web | title = Clinical topic - Menopause | work = NHS | url = http://www.cks.nhs.uk/menopause#-292420 | accessdate = 2 November 2009 }}</ref> Like the age of menarche, the age of menopause is largely a result of cultural and biological factors;<ref name=beyene>{{cite book | first=Yewoubdar | last=Beyene | year=1989 | title=From Menarche to Menopause: Reproductive Lives of Peasant Women in Two Cultures | publisher=State University of New York Press| location=Albany, NY | isbn=0-88706-866-9 }}</ref> however, illnesses, certain surgeries, or medical treatments may cause menopause to occur earlier than it might have otherwise.<ref>{{cite web | last = Shuman | first = Tracy | title = Your Guide to Menopause | work = WebMD |date=February 2006 | url = http://www.webmd.com/content/article/9/2953_504.htm | accessdate = 16 December 2006 }}</ref> | |||

| === Ovarian cycle === | |||

| The length of a woman's menstrual cycle typically varies somewhat, with some shorter cycles and some longer cycles. A woman who experiences variations of less than eight days between her longest cycles and shortest cycles is considered to have regular menstrual cycles. It is unusual for a woman to experience cycle length variations of less than four days. Length variation between eight and 20 days is considered as moderately ]. Variation of 21 days or more between a woman's shortest and longest cycle lengths is considered very irregular. <!--(see ])--><ref name=kippley>{{cite book |first=John |last=Kippley |first2=Sheila |last2=Kippley |year=1996 |title=The Art of Natural Family Planning |edition=4th |publisher=The Couple to Couple League |location=Cincinnati |isbn=978-0-926412-13-2 |page=92}}</ref> | |||

| Between menarche and menopause the ovaries regularly alternate between luteal and follicular phases during the monthly menstrual cycle.{{sfn | Sherwood | 2016 | p=741}} Stimulated by gradually increasing amounts of ] in the follicular phase, discharges of blood flow stop and the uterine lining thickens. Follicles in the ovary begin developing under the influence of a complex interplay of hormones, and after several days one, or occasionally two, become dominant, while non-dominant follicles shrink and die. About mid-cycle, some 10–12 hours after the increase in luteinizing hormone, known as the LH surge,<ref name= Reed2018>{{cite journal |vauthors= Reed BF, Carr BR, Feingold KR, et al |title= The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation |journal= Endotext |date= 2018 |pmid= 25905282 |url= https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/?report=classic |type= Review |access-date= 8 January 2021 |archive-date= 28 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210528022539/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/?report=classic |url-status= live }}</ref> the dominant follicle releases an ], in an event called ].{{sfn | Sherwood | 2016 | p=747}} | |||

| After ovulation, the oocyte lives for 24 hours or less without ],{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=957}} while the remains of the dominant follicle in the ovary become a ] – a body with the primary function of producing large amounts of the hormone ].{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=929}}{{efn|Progesterone levels exceed those of estrogen (estradiol) by a hundred-fold.{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=41}}}} Under the influence of progesterone, the uterine lining changes to prepare for potential ] of an ] to establish a pregnancy. The thickness of the endometrium continues to increase in response to mounting levels of estrogen, which is released by the ] (a mature ovarian follicle) into the blood circulation. Peak levels of estrogen are reached at around day thirteen of the cycle and coincide with ovulation. If implantation does not occur within about two weeks, the corpus luteum degenerates into the ], which does not produce hormones, causing a sharp drop in levels of both progesterone and estrogen. This drop causes the uterus to lose its lining in menstruation; it is around this time that the lowest levels of estrogen are reached.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|pp=942–946}} | |||

| The average menstrual cycle lasts 28 days. The variability of menstrual cycle lengths is highest for women under 25 years of age and is lowest, that is, most regular, for ages 35 to 39.<ref name=Chiazze1968>{{cite journal | author = Chiazze L, Brayer FT, Macisco JJ, Parker MP, Duffy BJ | title = The length and variability of the human menstrual cycle | journal = JAMA | volume = 203 | issue = 6 | pages = 377–80 | date = February 1968 | pmid = 5694118 | doi = 10.1001/jama.1968.03140060001001 }}</ref> Subsequently, the variability increases slightly for women aged 40 to 44.<ref name=Chiazze1968/> Usually, length variation between eight and 20 days in a woman is considered as moderately ].<ref name=kippley/> Variation of 21 days or more is considered very irregular.<ref name="kippley"/> | |||

| In an ovulatory menstrual cycle, the ovarian and uterine cycles are concurrent and coordinated and last between 21 and 35 days, with a population average of 27–29 days.{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=45}} Although the average length of the human menstrual cycle is similar to that of the ], there is ] between the two.{{sfn|Norris|Carr|2013|p= }} | |||

| The luteal phase of the menstrual cycle is about the same length in most individuals (mean 14/13 days, SD 1.41 days)<ref name=Lenton_luteal>{{cite journal | author = Lenton EA, Landgren BM, Sexton L | title = Normal variation in the length of the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle: identification of the short luteal phase | journal = Br J Obstet Gynaecol | volume = 91 | issue = 7 | pages = 685–9 | date = July 1984 | pmid = 6743610 | doi = 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb04831.x }}</ref> whereas the follicular phase tends to show much more variability (log-normally distributed with 95% of individuals having follicular phases between 10.3 and 16.3 days).<ref name=Lenton_follicular>{{cite journal | author = Lenton EA, Landgren BM, Sexton L, Harper R | title = Normal variation in the length of the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle: effect of chronological age | journal = Br J Obstet Gynaecol | volume = 91 | issue = 7 | pages = 681–4 | date = July 1984 | pmid = 6743609 | doi = 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1984.tb04830.x }}</ref> The follicular phase also seems to get significantly shorter with age (geometric mean 14.2 days in women aged 18–24 vs. 10.4 days in women aged 40–44).<ref name=Lenton_follicular /> | |||

| == Health effects == | |||

| Some women with ] experience increased activity of their conditions at about the same time during each menstrual cycle. For example, drops in estrogen levels have been known to trigger ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thedailyheadache.com/2006/04/linking_migrain.html |title=Migraine and Estrogen Officially Linked |publisher=The Daily Headache |accessdate=19 October 2012}}</ref> especially when the woman who suffers migraines is also taking the birth control pill. Many women with ] have more seizures in a pattern linked to the menstrual cycle; this is called "]".<ref name=pmid18164632>{{cite journal | author = Herzog AG | title = Catamenial epilepsy: definition, prevalence pathophysiology and treatment | journal = Seizure | volume = 17 | issue = 2 | pages = 151–9 | date = March 2008 | pmid = 18164632 | doi = 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.11.014 }}</ref> Different patterns seem to exist (such as seizures coinciding with the time of menstruation, or coinciding with the time of ovulation), and the frequency with which they occur has not been firmly established. Using one particular definition, one group of scientists found that around one-third of women with intractable partial epilepsy has catamenial epilepsy.<ref name=pmid18164632/><ref name=pmid15349872>{{cite journal | author = Herzog AG, Harden CL, Liporace J, Pennell P, Schomer DL, Sperling M, Fowler K, Nikolov B, Shuman S, Newman M | title = Frequency of catamenial seizure exacerbation in women with localization-related epilepsy | journal = Annals of Neurology | volume = 56 | issue = 3 | pages = 431–4 | date = September 2004 | pmid = 15349872 | doi = 10.1002/ana.20214 }}</ref><ref name=pmid9579954>{{cite journal | author = Herzog AG, Klein P, Ransil BJ | title = Three patterns of catamenial epilepsy | journal = Epilepsia | volume = 38 | issue = 10 | pages = 1082–8 | date = October 1997 | pmid = 9579954 | doi = 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01197.x }}</ref> An effect of hormones has been proposed, in which progesterone declines and estrogen increases would trigger seizures.<ref name=pmid16981857>{{cite journal | author = Scharfman HE, MacLusky NJ | title = The influence of gonadal hormones on neuronal excitability, seizures, and epilepsy in the female | journal = Epilepsia | volume = 47 | issue = 9 | pages = 1423–40 | date = September 2006 | pmid = 16981857 | pmc = 1924802 | doi = 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00672.x }}</ref> Recently, studies have shown that high doses of estrogen can cause or worsen seizures, whereas high doses of progesterone can act like an antiepileptic drug.<ref name="epilepsy">{{cite web|url=http://www.epilepsy.com/epilepsy/provoke_menstrual |title=Menstrual cycle |publisher=epilepsy.com |accessdate=19 October 2012}}</ref> Studies by medical journals have found that women experiencing menses are 1.68 times more likely to commit ].<ref name=SuicideRatesPsyMed>{{cite journal | author = Baca-García E, Diaz-Sastre C, Ceverino A, Saiz-Ruiz J, Diaz FJ, de Leon J | title = Association between the menses and suicide attempts: a replication study | journal = Psychosom Med | volume = 65 | issue = 2 | pages = 237–44 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12651991 | doi = 10.1097/01.PSY.0000058375.50240.F6 }}</ref> | |||

| Mice have been used as an experimental system to investigate possible mechanisms by which levels of ] hormones might regulate ] function. During the part of the mouse estrous cycle when progesterone is highest, the level of ] ] subtype delta was high. Since these GABA receptors are ], nerve cells with more delta receptors are less likely to fire than cells with lower numbers of delta receptors. During the part of the mouse estrous cycle when estrogen levels are higher than progesterone levels, the number of delta receptors decrease, increasing nerve cell activity, in turn increasing anxiety and seizure susceptibility.<ref name=Maguire>{{cite journal | author = Maguire JL, Stell BM, Rafizadeh M, Mody I | title = Ovarian cycle-linked changes in GABA(A) receptors mediating tonic inhibition alter seizure susceptibility and anxiety | journal = Nat. Neurosci. | volume = 8 | issue = 6 | pages = 797–804 | date = June 2005 | pmid = 15895085 | doi = 10.1038/nn1469 }}</ref> | |||

| Estrogen levels may affect ] behavior.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Doufas AG, Mastorakos G | title = The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis and the female reproductive system | journal = Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences | volume = 900 | issue = | pages = 65–76 | year = 2000 | pmid = 10818393 | doi = 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06217.x }}</ref> For example, during the luteal phase (when estrogen levels are lower), the velocity of blood flow in the thyroid is lower than during the follicular phase (when estrogen levels are higher).<ref>{{cite journal | author = Krejza J, Nowacka A, Szylak A, Bilello M, Melhem LY | title = Variability of thyroid blood flow Doppler parameters in healthy women | journal = Ultrasound Med Biol | volume = 30 | issue = 7 | pages = 867–76 | date = July 2004 | pmid = 15313319 | doi = 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.05.008 }}</ref> | |||

| Among women living closely together, it was once thought that the onsets of menstruation tend to ]. This effect was first described in 1971, and possibly explained by the action of ]s in 1998.<ref name=Mclintock>{{cite journal | author = Stern K, McClintock MK | title = Regulation of ovulation by human pheromones | journal = Nature | volume = 392 | issue = 6672 | pages = 177–9 | date = March 1998 | pmid = 9515961 | doi = 10.1038/32408 }}</ref> Subsequent research has called this hypothesis into question.<ref>{{cite web | last = Adams | first = Cecil | authorlink = Cecil Adams | title = Does menstrual synchrony really exist? | work = The Straight Dope | publisher = The Chicago Reader | date = 20 December 2002 | url = http://www.straightdope.com/columns/021220.html | accessdate = 10 January 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| Research indicates that women have a significantly higher likelihood of ] injuries in the pre-ovulatory stage, than post-ovulatory stage.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Renstrom P, Ljungqvist A, Arendt E, Beynnon B, Fukubayashi T, Garrett W, Georgoulis T, Hewett TE, Johnson R, Krosshaug T, Mandelbaum B, Micheli L, Myklebust G, Roos E, Roos H, Schamasch P, Shultz S, Werner S, Wojtys E, Engebretsen L | title = Non-contact ACL injuries in female athletes: an International Olympic Committee current concepts statement | journal = Br J Sports Med | volume = 42 | issue = 6 | pages = 394–412 | date = June 2008 | pmid = 18539658 | doi = 10.1136/bjsm.2008.048934 | pmc=3920910}}</ref> | |||

| === Fertility === | |||

| {{main|Fertility testing}} | |||

| The most fertile period (the time with the highest likelihood of pregnancy resulting from ]) covers the time from some 5 days before until 1 to 2 days after ovulation.<ref>Weschler (2002), pp.242,374</ref> In a 28‑day cycle with a 14‑day luteal phase, this corresponds to the second and the beginning of the third week. A variety of methods have been developed to help individual women estimate the relatively fertile and the relatively infertile days in the cycle; these systems are called ]. | |||

| Fertility awareness methods that rely on cycle length records alone are called ].<ref name=who>{{cite journal |title=Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use:Fertility awareness-based methods | version = Third edition |publisher=World Health Organization |year=2004 |url=http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/mec/fab.html |accessdate=29 April 2008 }}</ref> Methods that require observation of one or more of the three primary fertility signs (], ], and cervical position)<ref>Weschler (2002), p.52</ref> are known as symptoms-based methods.<ref name=who/> ] kits are available that detect the LH surge that occurs 24 to 36 hours before ovulation; these are known as ovulation predictor kits (OPKs).<ref>{{MedlinePlusEncyclopedia|007062|LH urine test (home test)}}</ref> Computerized devices that interpret basal body temperatures, urinary test results, or changes in saliva are called ]. | |||

| A ] is also affected by her age.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Leridon H | title = Can assisted reproduction technology compensate for the natural decline in fertility with age? A model assessment | journal = Hum. Reprod. | volume = 19 | issue = 7 | pages = 1548–53 | date = July 2004 | pmid = 15205397 | doi = 10.1093/humrep/deh304 }}</ref> As a woman's total egg supply is formed in fetal life,<!-- | |||

| --><ref>{{cite web | last = Krock | first = Lexi | title = Fertility Throughout Life | work = 18 Ways to Make a Baby | publisher = NOVA Online |date=October 2001 | url = http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/baby/fert_text.html | accessdate = 24 December 2006 }} | |||

| {{cite web | last = Haines | first = Cynthiac | title = Your Guide to the Female Reproductive System | work = The Cleveland Clinic Women's Health Center | publisher = WebMD |date=January 2006 | url = http://www.webmd.com/content/article/51/40619.htm | accessdate = 24 December 2006 }}</ref> to be ovulated decades later, it has been suggested that this long lifetime may make the ] of eggs more vulnerable to division problems, breakage, and mutation than the chromatin of sperm, which are produced continuously during a man's reproductive life. However, despite this hypothesis, a similar ] has also been observed. | |||

| As measured on women undergoing ], a longer menstrual cycle length is associated with higher pregnancy and delivery rates, even after age adjustment.<ref name="Brodin2008">{{cite journal | author = Brodin T, Bergh T, Berglund L, Hadziosmanovic N, Holte J | title = Menstrual cycle length is an age-independent marker of female fertility: Results from 6271 treatment cycles of in vitro fertilization | journal = Fertility and Sterility | volume = 90 | issue = 5 | pages = 1656–1661 | year = 2008 | pmid = 18155201 | pmc = | doi = 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.036 }}</ref> ]s after IVF have been estimated to be almost doubled for women with a menstrual cycle length of more than 34 days compared with women with a menstrual cycle length shorter than 26 days.<ref name="Brodin2008"/> A longer menstrual cycle length is also significantly associated with better ovarian response to ] stimulation and ].<ref name="Brodin2008"/> | |||

| === Mood and behavior === | |||

| The different phases of the menstrual cycle correlate with women’s ]. In some cases, hormones released during the menstrual cycle can cause behavioral changes in females; mild to severe mood changes can occur.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Danaceau MA, Adams LF, Rubinow DR | title = Differential behavioral effects of gonadal steroids in women with and in those without premenstrual syndrome | journal = N. Engl. J. Med. | volume = 338 | issue = 4 | pages = 209–16 | date = January 1998 | pmid = 9435325 | doi = 10.1056/NEJM199801223380401 }}</ref> The menstrual cycle phase and ovarian ] may contribute to increased ] in women. The natural shift of hormone levels during the different phases of the menstrual cycle has been studied in conjunction with test scores. When completing empathy exercises, women in the ] of their menstrual cycle performed better than women in their ]. A significant correlation between ] levels and the ability to accurately recognize emotion was found. Performances on emotion recognition tasks were better when women had lower progesterone levels. Women in the follicular stage showed higher emotion recognition accuracy than their midluteal phase counterparts. Women were found to react more to negative stimuli when in midluteal stage over the women in the follicular stage, perhaps indicating more reactivity to social stress during that menstrual cycle phase.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Derntl B, Hack RL, Kryspin-Exner I, Habel U | title = Association of menstrual cycle phase with the core components of empathy | journal = Horm Behav | volume = 63 | issue = 1 | pages = 97–104 | date = January 2013 | pmid = 23098806 | pmc = 3549494 | doi = 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.10.009 }}</ref> Overall, it has been found that women in the follicular phase demonstrated better performance in tasks that contain empathetic traits. | |||

| ] in women during two different points in the menstrual cycle has been examined. When ] is highest in the ], women are significantly better at identifying expressions of fear than women who were menstruating, which is when oestrogen levels are lowest. The women were equally able to identify happy faces, demonstrating that the fear response was a more powerful response. To summarize, menstrual cycle phase and the oestrogen levels correlates with women’s fear processing.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Schwartz DH, Romans SE, Meiyappan S, De Souza MJ, Einstein G | title = The role of ovarian steroid hormones in mood | journal = Horm Behav | volume = 62 | issue = 4 | pages = 448–54 | date = September 2012 | pmid = 22902271 | doi = 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.08.001 }}</ref> | |||

| However, the examination of daily moods in women with measuring ovarian hormones may indicate a less powerful connection. In comparison to levels of ] or physical health, the ovarian hormones had less of an impact on overall mood.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Pearson R, Lewis MB | title = Fear recognition across the menstrual cycle | journal = Horm Behav | volume = 47 | issue = 3 | pages = 267–71 | date = March 2005 | pmid = 15708754 | doi = 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.003 }}</ref> This indicates that while changes of ovarian hormones may influence mood, on a day-to-day level it does not influence mood more than other stressors do. | |||

| ===Menstural disorders=== <!-- ] refers to here --> | |||

| {{main|Menstrual disorder}} | |||

| Infrequent or irregular ovulation is called ''oligoovulation''.<ref>{{cite web | last = Galan | first = Nicole | title = Oligoovulation | publisher = about.com | date = 16 April 2008 | url = http://pcos.about.com/od/glossary/g/oligoovulation.htm | accessdate = 12 October 2008}}</ref> The absence of ovulation is called '']''. Normal menstrual flow can occur without ovulation preceding it: an ]. In some cycles, follicular development may start but not be completed; nevertheless, estrogens will be formed and stimulate the uterine lining. Anovulatory flow resulting from a very thick endometrium caused by prolonged, continued high estrogen levels is called ''estrogen breakthrough bleeding''. Anovulatory bleeding triggered by a sudden drop in estrogen levels is called changes.<ref name=tcoyf3>Weschler (2002), p.107</ref> Anovulatory cycles commonly occur before ] (perimenopause) and in women with ].<ref name=emed2>{{EMedicine|med|146|Anovulation}}</ref> | |||

| Very little flow (less than 10 ml) is called '']''. Regular cycles with intervals of 21 days or fewer are '']''; frequent but irregular menstruation is known as '']''. Sudden heavy flows or amounts greater than 80 ml are termed '']''.<ref name=emed1>{{EMedicine|ped|2781|Menstruation Disorders}}</ref> Heavy menstruation that occurs frequently and irregularly is '']''. The term for cycles with intervals exceeding 35 days is '']''.<ref name=afp>{{cite journal | author = Oriel KA, Schrager S | title = Abnormal uterine bleeding | journal = Am Fam Physician | volume = 60 | issue = 5 | pages = 1371–80; discussion 1381–2 | date = October 1999 | pmid = 10524483 | url = http://www.aafp.org/link_out?pmid=10524483 }}</ref> ] refers to more than three<ref name=emed1/> to six<ref name=afp/> months without menses (while not being pregnant) during a woman's reproductive years. | |||

| ==Cycles and phases== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The menstrual cycle can be described by the ovarian or uterine cycle. The ovarian cycle describes changes that occur in the ] of the ovary whereas the uterine cycle describes changes in the ] of the uterus. Both cycles can be divided into three phases. The ovarian cycle consists of the follicular phase, ovulation, and the luteal phase whereas the uterine cycle consists of menstruation, proliferative phase, and secretory phase.<ref name=Silverthorn /> | |||

| === Ovarian cycle === | |||

| ==== Follicular phase ==== | ==== Follicular phase ==== | ||

| {{main|Follicular phase}} | {{main|Follicular phase}} | ||

| The ovaries contain a finite number of ], ] and ], which together form primordial follicles.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=929}} At around 20 weeks into ] some 7 million immature eggs have already formed in an ovary. This decreases to around 2 million by the time a girl is born, and 300,000 by the time she has her first period. On average, one egg matures and is released during ovulation each month after menarche.{{sfn | Ugwumadu | 2014 | p=115}} Beginning at puberty, these mature to primary follicles independently of the menstrual cycle.{{sfn | Watchman | 2020 | p=8}} The development of the egg is called ] and only one cell survives the ] to await fertilization. The other cells are discarded as ], which cannot be fertilized.<ref name="pmid21268179">{{cite journal |vauthors=Schmerler S, Wessel GM |title=Polar bodies – more a lack of understanding than a lack of respect |journal=Molecular Reproduction and Development |volume=78 |issue=1 |pages=3–8 |date=January 2011 |pmid=21268179 |pmc=3164815 |doi=10.1002/mrd.21266 |type= Review}}</ref> The follicular phase is the first part of the ovarian cycle and it ends with the completion of the ].{{sfn | Sherwood | 2016 | p=741}} ] (cell division) remains incomplete in the egg cells until the antral follicle is formed. During this phase usually only one ovarian follicle fully matures and gets ready to release an egg.{{sfn | Tortora | 2017 | p=945}} The follicular phase shortens significantly with age, lasting around 14 days in women aged 18–24 compared with 10 days in women aged 40–44.{{sfn | Tortora | 2017 | pp=942–946}} | |||

| The follicular phase is the first part of the ovarian cycle. During this phase, the ovarian follicles mature and get ready to release an egg.<ref name=Silverthorn /> The latter part of this phase overlaps with the proliferative phase of the uterine cycle. | |||

| Through the influence of a rise in ] (FSH) during the first days of the cycle, a few |

Through the influence of a rise in ] (FSH) during the first days of the cycle, a few ovarian follicles are stimulated. These follicles, which have been developing for the better part of a year in a process known as ], compete with each other for dominance. All but one of these follicles will stop growing, while one dominant follicle – the one that has the most FSH receptors – will continue to maturity. The remaining follicles die in a process called ].{{sfn|Johnson|2007|page=86}} ] (LH) stimulates further development of the ovarian follicle. The follicle that reaches maturity is called an antral follicle, and it contains the ] (egg cell).{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=942}} | ||

| The theca cells develop receptors that bind LH, and in response secrete large amounts of ]. At the same time the granulosa cells surrounding the maturing follicle develop receptors that bind FSH, and in response start secreting androstenedione, which is converted to estrogen by the enzyme ]. The estrogen inhibits further production of FSH and LH by the pituitary gland. This ] regulates levels of FSH and LH. The dominant follicle continues to secrete estrogen, and the rising estrogen levels make the pituitary more responsive to GnRH from the hypothalamus. As estrogen increases this becomes a ] signal, which makes the pituitary secrete more FSH and LH. This surge of FSH and LH usually occurs one to two days before ovulation and is responsible for stimulating the rupture of the antral follicle and release of the oocyte.{{sfn | Watchman | 2020 | p=8}}{{sfn | Sherwood | 2016 | p=745}} | |||

| ==== Ovulation ==== | ==== Ovulation ==== | ||

| {{main|Ovulation}} | {{main|Ovulation}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Around day fourteen, the egg is released from the ovary.{{sfn | Tortora | 2017 | p=943}} Called ], this occurs when a mature egg is released from the ovarian follicles into the pelvic cavity and enters the ], about 10–12 hours after the peak in LH surge.<ref name= Reed2018/> Typically only one of the 15–20 stimulated follicles reaches full maturity, and just one egg is released.{{sfn | Sadler | 2019 | p=48}} Ovulation only occurs in around 10% of cycles during the first two years following menarche, and by the age of 40–50, the number of ovarian follicles is depleted.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=953}} LH initiates ovulation at around day 14 and stimulates the formation of the corpus luteum.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=944}} Following further stimulation by LH, the corpus luteum produces and releases estrogen, progesterone, ] (which relaxes the uterus by inhibiting contractions of the ]), and ] (which inhibits further secretion of FSH).{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=920}} | |||

| The release of LH matures the egg and weakens the follicle wall in the ovary, causing the fully developed follicle to release its oocyte.{{sfn | Sherwood | 2016 | p=746}} If it is fertilized by a sperm, the oocyte promptly matures into an ], which blocks the other ] and becomes a mature egg. If it is not fertilized by a sperm, the oocyte degenerates. The mature egg has a diameter of about {{cvt|0.1|mm}},<ref>{{Cite book| vauthors = Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P |date=2002|chapter=Eggs|title=Molecular Biology of the Cell|edition=4th|isbn=0-8153-3218-1|chapter-url= https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26842/ |location=New York|publisher=Garland Science |access-date=25 February 2021 |archive-date=16 December 2019 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20191216042524/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26842/ |url-status=live}}</ref> and is the largest human cell.<ref name="pmid30739329">{{cite journal | vauthors = Iussig B, Maggiulli R, Fabozzi G, Bertelle S, Vaiarelli A, Cimadomo D, Ubaldi FM, Rienzi L | title = A brief history of oocyte cryopreservation: Arguments and facts | journal = Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica | volume = 98 | issue = 5 | pages = 550–558 | date = May 2019 | pmid = 30739329 | doi = 10.1111/aogs.13569 | type = Review | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| Ovulation is the second phase of the ovarian cycle in which a mature egg is released from the ovarian follicles into the oviduct.<ref> at Duke Fertility Center. Retrieved 2 July 2011</ref> During the follicular phase, ] suppresses production of ] (LH) from the ]. When the egg has nearly matured, levels of ] reach a threshold above which this effect is reversed and estrogen stimulates the production of a large amount of LH. This process, known as the LH surge, starts around day 12 of the average cycle and may last 48 hours.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pregnology.com/ovulate/16/2/10/1/15/2013|title=Ovulation Calendar|publisher=Pregnology}}</ref> | |||

| Which of the two ovaries – left or right – ovulates appears random;{{sfn | Parker | 2019 | p=283}} no left and right coordinating process is known.{{sfn|Johnson|2007|pp=192–193}} Occasionally both ovaries release an egg; if both eggs are fertilized, the result is ]s.{{sfn|Johnson|2007|p=192}} After release from the ovary into the pelvic cavity, the egg is swept into the fallopian tube by the ] – a fringe of tissue at the end of each fallopian tube. After about a day, an unfertilized egg disintegrates or dissolves in the fallopian tube, and a fertilized egg reaches the uterus in three to five days.{{sfn | Sadler | 2019 | p=36}} | |||

| The exact mechanism of these opposite responses of LH levels to estradiol is not well understood.<ref name=Lentz>{{cite book|authors=Lentz, Gretchen M; Lobo, Rogerio A.; Gershenson, David M; Katz, Vern L.|title=Comprehensive gynecology.|year=2013|publisher=Elsevier Mosby|location=St. Louis|isbn=978-0-323-06986-1|url=http://www.mdconsult.com/books/page.do?eid=4-u1.0-B978-0-323-06986-1..00004-4--s0195&isbn=978-0-323-06986-1&sid=1291988935&uniqId=327920693-3#4-u1.0-B978-0-323-06986-1..00004-4--s0195|accessdate=5 April 2012}}</ref><sup>:86</sup> In animals, a ] (GnRH) surge has been shown to precede the LH surge, suggesting that estrogen's main effect is on the hypothalamus, which controls GnRH secretion.<ref name=Lentz /><sup>:86</sup> This may be enabled by the presence of two different estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus: ], which is responsible for the negative feedback estradiol-LH loop, and ], which is responsible for the positive estradiol-LH relationship.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Hu L, Gustofson RL, Feng H, Leung PK, Mores N, Krsmanovic LZ, Catt KJ | title = Converse regulatory functions of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta subtypes expressed in hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons | journal = Mol. Endocrinol. | volume = 22 | issue = 10 | pages = 2250–9 | date = October 2008 | pmid = 18701637 | pmc = 2582533 | doi = 10.1210/me.2008-0192 }}</ref> However, in humans it has been shown that high levels of estradiol can provoke abrupt increases in LH, even when GnRH levels and pulse frequencies are held constant,<ref name=Lentz /><sup>:86</sup> suggesting that estrogen acts directly on the pituitary to provoke the LH surge. | |||

| Fertilization usually takes place in the ], the widest section of the fallopian tubes. A ] immediately starts the process of ]. The developing embryo takes about three days to reach the uterus, and another three days to implant into the endometrium. It has reached the ] stage at the time of implantation: this is when pregnancy begins.{{sfn | Tortora | 2017 | p=959}} The loss of the corpus luteum is prevented by fertilization of the egg. The ] (the outer layer of the resulting embryo-containing blastocyst that later becomes the outer layer of the placenta) produces ] (hCG), which is very similar to LH and preserves the corpus luteum. During the first few months of pregnancy, the corpus luteum continues to secrete progesterone and estrogens at slightly higher levels than those at ovulation. After this and for the rest of the pregnancy, the ] secretes high levels of these hormones – along with human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which stimulates the corpus luteum to secrete more progesterone and estrogens, blocking the menstrual cycle.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|page=976}} These hormones also prepare the mammary glands for milk{{efn|] women can experience complete suppression of follicular development, follicular development but no ovulation, or resumption of normal menstrual cycles.<ref name="pmid25869631">{{cite journal |vauthors=Carr SL, Gaffield ME, Dragoman MV, Phillips S |title=Safety of the progesterone-releasing vaginal ring (PVR) among lactating women: A systematic review |journal=Contraception |volume=94 |issue=3 |pages=253–261 |date=September 2016 |pmid=25869631 |doi=10.1016/j.contraception.2015.04.001 |doi-access=free |type= Review}}</ref>}} production.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|page=976}} | |||

| The release of LH matures the egg and weakens the wall of the follicle in the ovary, causing the fully developed follicle to release its ].<ref name="isbn0-07-303120-8"/> The secondary oocyte promptly matures into an ] and then becomes a mature ]. The mature ovum has a diameter of about 0.2 mm.<ref>{{cite book |author=Gray, Henry David |title=Anatomy of the human body |chapter=The Ovum |publisher=Bartleby.com |location=Philadelphia |year=2000 |chapterurl=http://education.yahoo.com/reference/gray/subjects/subject/3 |isbn=1-58734-102-6 |accessdate=5 October 2008}}</ref> | |||

| Which of the two ovaries—left or right—ovulates appears essentially random; no known left and right co-ordination exists.<ref name=ov>{{cite journal | author = Ecochard R, Gougeon A | title = Side of ovulation and cycle characteristics in normally fertile women | journal = Hum. Reprod. | volume = 15 | issue = 4 | pages = 752–5 | date = April 2000 | pmid = 10739814 | doi = 10.1093/humrep/15.4.752 }}</ref> Occasionally, both ovaries will release an egg;<ref name=ov/> if both eggs are fertilized, the result is ]s.<ref name=twins>{{cite web | title = Multiple Pregnancy: Twins or More - Topic Overview | work = WebMD Medical Reference from Healthwise | date = 24 July 2007 | url = http://www.webmd.com/baby/tc/multiple-pregnancy-twins-or-more-topic-overview | accessdate = 5 October 2008}}</ref> | |||

| After being released from the ovary, the egg is swept into the ] by the ], which is a fringe of tissue at the end of each fallopian tube. After about a day, an unfertilized egg will disintegrate or dissolve in the fallopian tube.<ref name="isbn0-07-303120-8"/> | |||

| Fertilization by a ], when it occurs, usually takes place in the ], the widest section of the fallopian tubes. A fertilized egg immediately begins the process of ], or development. The developing embryo takes about three days to reach the uterus and another three days to implant into the endometrium.<ref name="isbn0-07-303120-8"/> It has usually reached the ] stage at the time of implantation. | |||

| In some women, ovulation features a characteristic pain called '']'' (German term meaning ''middle pain'').<ref name=allmenses/> The sudden change in hormones at the time of ovulation sometimes also causes light mid-cycle blood flow.<ref>Weschler (2002), p.65</ref> | |||

| ==== Luteal phase ==== | ==== Luteal phase ==== | ||

| {{main|Luteal phase}} | {{main|Luteal phase}} | ||

| Lasting about 14 days,<ref name="Reed2018" /> the luteal phase is the final phase of the ovarian cycle and it corresponds to the secretory phase of the uterine cycle. During the luteal phase, the pituitary hormones FSH and LH cause the remaining parts of the dominant follicle to transform into the corpus luteum, which produces progesterone.{{sfn|Johnson|2007|page=91}}{{efn|In the corpus luteum, ] converts ] to ], which is converted to progesterone.<ref name="pmid22201776">{{cite journal |vauthors=King SR, LaVoie HA |title=Gonadal transactivation of STARD1, CYP11A1 and HSD3B |journal=Frontiers in Bioscience (Landmark Edition) |volume=17 |issue= 3|pages=824–846 |date=January 2012 |pmid=22201776 |doi=10.2741/3959 |doi-access=free }}</ref>}} The increased progesterone starts to induce the production of estrogen. The hormones produced by the corpus luteum also suppress production of the FSH and LH that the corpus luteum needs to maintain itself. The level of FSH and LH fall quickly, and the corpus luteum atrophies.{{sfn | Ugwumadu | 2014 | p=117}} Falling levels of progesterone trigger menstruation and the beginning of the next cycle. From the time of ovulation until progesterone withdrawal has caused menstruation to begin, the process typically takes about two weeks. For an individual woman, the follicular phase often varies in length from cycle to cycle; by contrast, the length of her luteal phase will be fairly consistent from cycle to cycle at 10 to 16 days (average 14 days).{{sfn | Tortora | 2017 | pp=942–946}} | |||

| The loss of the corpus luteum is prevented by fertilization of the egg. The ], which is the outer layer of the resulting embryo-containing structure (the ]) and later also becomes the outer layer of the placenta, produces ] (hCG), which is very similar to LH and which preserves the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum can then continue to secrete progesterone to maintain the new pregnancy. Most ]s look for the presence of hCG.<ref name="isbn0-07-303120-8"/> | |||

| ===Uterine cycle=== | === Uterine cycle === | ||

| ] | |||

| The uterine cycle has three phases: menses, proliferative and secretory.<ref name="pmid30521482">{{cite journal |vauthors=Salamonsen LA |title=Women in reproductive science: Understanding human endometrial function |journal=Reproduction |volume=158 |issue=6 |pages=F55–F67 |date=December 2019 |pmid=30521482 |doi=10.1530/REP-18-0518 |doi-access=free |type= Review}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Menstruation ==== | ==== Menstruation ==== | ||

| {{main|Menstruation}} | {{main|Menstruation}} | ||

| Menstruation (also called menstrual bleeding, menses or a period) is the first and most evident phase of the uterine cycle and first occurs at puberty. Called menarche, the first period occurs at the age of around twelve or thirteen years.<ref name="pmid26703478">{{cite journal |vauthors=Papadimitriou A |title=The evolution of the age at menarche from prehistorical to modern times |journal=Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology |volume=29 |issue=6 |pages=527–530 |date=December 2016 |pmid=26703478 |doi=10.1016/j.jpag.2015.12.002 |type= Review}}</ref> The average age is generally later in the ] and earlier in the ].<ref name="pmid29778270">{{cite journal |vauthors=Alvergne A, Högqvist Tabor V |title=Is female health cyclical? Evolutionary perspectives on menstruation |journal=Trends in Ecology & Evolution |volume=33 |issue=6 |pages=399–414 |date=June 2018 |pmid=29778270 |doi=10.1016/j.tree.2018.03.006 |arxiv=1704.08590 |bibcode=2018TEcoE..33..399A |s2cid=4581833 |type= Review}}</ref> In ], it can occur as early as age eight years,<ref name="pmid28591132">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ibitoye M, Choi C, Tai H, Lee G, Sommer M |title=Early menarche: A systematic review of its effect on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=12 |issue=6 |pages=e0178884 |date=2017 |pmid=28591132 |pmc=5462398 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0178884 |bibcode=2017PLoSO..1278884I |type= Review|doi-access=free }}</ref> and this can still be normal.<ref name=Women2014Men>{{cite web|title=Menstruation and the menstrual cycle fact sheet|url=http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/menstruation.html|website=Office of Women's Health |publisher= US Department of Health and Human Services |access-date=25 June 2015|date=23 December 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150626134338/http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/menstruation.html|archive-date=26 June 2015}}</ref><ref name="pmid29422239">{{cite journal |vauthors=Sultan C, Gaspari L, Maimoun L, Kalfa N, Paris F |title=Disorders of puberty |journal=Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology |volume=48 |issue= |pages=62–89 |date=April 2018 |pmid=29422239 |doi=10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.11.004 |url=https://hal.umontpellier.fr/hal-01797379/file/2018%20Sultan%20et%20al.%2C%20Disorders%20of%20puberty.pdf |type=Review |access-date=27 February 2021 |archive-date=1 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200701081342/https://hal.umontpellier.fr/hal-01797379/file/2018%20Sultan%20et%20al.,%20Disorders%20of%20puberty.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Menstruation (also called menstrual bleeding, menses, catamenia or a period) is the first phase of the uterine cycle. The flow of menses normally serves as a sign that a woman has not become ]. (However, this cannot be taken as certainty, as a number of factors can cause ]; some factors are specific to ], and some can cause ].)<ref>{{cite web | last = Greenfield | first = Marjorie | title = Subchorionic Hematoma in Early Pregnancy | work = Ask Our Experts | publisher = DrSpock.com | date = 17 September 2001 | url = http://www.drspock.com/faq/0,1511,8334,00.html | accessdate = 21 September 2008 | archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080915192741/http://www.drspock.com/faq/0,1511,8334,00.html <!--Added by H3llBot--> | archivedate = 15 September 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last = Anderson-Berry | first = Ann L |author2=Terence Zach | title = Vanishing Twin Syndrome | journal = Emedicine.com | publisher = WebMD | date = 10 December 2007 | url = http://www.emedicine.com/med/TOPIC3411.HTM | accessdate = 21 September 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last = Ko | first = Patrick |author2=Young Yoon | title = Placenta Previa | journal = Emedicine.com | publisher = WebMD | date = 23 August 2007 | url = http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic427.htm | accessdate = 21 September 2008}}</ref> | |||

| Menstruation is initiated each month by falling levels of estrogen and progesterone and the release of ]s,{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=945}} which constrict the ]. This causes them to ], contract and break up.{{sfn|Johnson|2007|p=152}} The blood supply to the endometrium is cut off and the cells of the top layer of the endometrium (the stratum functionalis) become deprived of oxygen and die. Later the whole layer is lost and only the bottom layer, the stratum basalis, is left in place.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|page=945}} An ] called ] breaks up the ] in the menstrual fluid, which eases the flow of blood and broken down lining from the uterus.{{sfn | Tortora | 2017 | p=600}} The flow of blood continues for 2–6 days and around 30–60 ] of blood is lost,{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=45}} and is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred.{{sfn|Johnson|2007|p=99}} | |||

| ] (the main estrogen), ], luteinizing hormone, and ] during the menstrual cycle, taking inter-cycle and inter-woman variability into account.]] | |||

| The flow of blood normally serves as a sign that a woman has not become pregnant, but this cannot be taken as certainty, as several factors can cause ].<ref name="pmid27166462">{{cite journal |vauthors=Breeze C |title=Early pregnancy bleeding |journal=Australian Family Physician |volume=45 |issue=5 |pages=283–286 |date=May 2016 |pmid=27166462 |type= Review}}</ref> Menstruation occurs on average once a month from menarche to menopause, which corresponds with a woman's fertile years. The average age of menopause in women is 52 years, and it typically occurs between 45 and 55 years of age.<ref name="pmid27022074">{{cite journal |vauthors=Towner MC, Nenko I, Walton SE |title=Why do women stop reproducing before menopause? A life-history approach to age at last birth |journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences |volume=371 |issue=1692 |page=20150147 |date=April 2016 |pmid=27022074 |pmc=4822427 |doi=10.1098/rstb.2015.0147 |type= Review}}</ref> Menopause is preceded by a stage of hormonal changes called ].{{sfn | Rodriguez-Landa | 2017 | p=8}} | |||

| ''Eumenorrhea'' denotes normal, regular menstruation that lasts for a few days (usually 3 to 5 days, but anywhere from 2 to 7 days is considered normal).<ref name=allmenses>{{cite web | author=John M Goldenring | title=All About Menstruation |url=http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/all-about-menstruation | date=1 February 2007 | publisher=WebMD | accessdate=5 October 2008}}</ref><ref name="US-typical">{{cite web|title=Menstruation and the Menstrual Cycle|url=http://www.4woman.gov/faq/menstru.htm#4|publisher=Womenshealth.gov|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20081024163538/http://www.4woman.gov//faq/menstru.htm|archivedate=24 October 2008|date=April 2007}}</ref> The average ] during menstruation is 35 milliliters with 10–80 ml considered normal.<ref name=bloodloss>{{cite web | author=David L Healy | title=Menorrhagia Heavy Periods - Current Issues | date=24 November 2004 | publisher=Monash University | id=ABN 12 377 614 012 | url=http://www.med.monash.edu.au/ob-gyn/research/menorr.html}}</ref> Women who experience ] are more susceptible to ] than the average person.<ref name=iron>{{cite journal | author = Harvey LJ, Armah CN, Dainty JR, Foxall RJ, John Lewis D, Langford NJ, Fairweather-Tait SJ | title = Impact of menstrual blood loss and diet on iron deficiency among women in the UK | journal = Br. J. Nutr. | volume = 94 | issue = 4 | pages = 557–64 | date = October 2005 | pmid = 16197581 | doi = 10.1079/BJN20051493 }}</ref> An ] called ] inhibits ] in the menstrual fluid.<ref name=plasmin>{{cite journal | author = Shiraishi M | title = Studies on identification of menstrual blood stain by fibrin-plate method. I. A study on the incoagulability of menstrual blood | journal = Acta Med Okayama | volume = 16 | issue = | pages = 192–200 | date = August 1962 | pmid = 13977381 | url = http://escholarship.lib.okayama-u.ac.jp/amo/vol16/iss4/2 }}</ref> | |||

| ''Eumenorrhea'' denotes normal, regular menstruation that lasts for around the first 5 days of the cycle.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=943}} Women who experience ] (heavy menstrual bleeding) are more susceptible to ] than the average person.<ref name=iron>{{cite journal | vauthors = Harvey LJ, Armah CN, Dainty JR, Foxall RJ, John Lewis D, Langford NJ, Fairweather-Tait SJ | title = Impact of menstrual blood loss and diet on iron deficiency among women in the UK | journal = The British Journal of Nutrition | volume = 94 | issue = 4 | pages = 557–564 | date = October 2005 | pmid = 16197581 | doi = 10.1079/BJN20051493 | doi-access = free| type= Comparative study}}</ref> | |||

| Painful cramping in the abdomen, back, or upper thighs is common during the first few days of menstruation. Severe uterine pain during menstruation is known as ], and it is most common among adolescents and younger women (affecting about 67.2% of adolescent females).<ref>{{cite journal | author = Sharma P, Malhotra C, Taneja DK, Saha R | title = Problems related to menstruation amongst adolescent girls | journal = Indian J Pediatr | volume = 75 | issue = 2 | pages = 125–9 | date = February 2008 | pmid = 18334791 | doi = 10.1007/s12098-008-0018-5 }}</ref> When menstruation begins, symptoms of ] (PMS) such as ] and irritability generally decrease.<ref name=allmenses/> Many ] are marketed to women for use during their menstruation. | |||

| ==== Proliferative phase ==== | ==== Proliferative phase ==== | ||

| ] | |||

| The proliferative phase is the second phase of the uterine cycle when estrogen causes the lining of the uterus to grow |

The proliferative phase is the second phase of the uterine cycle when estrogen causes the lining of the uterus to grow and proliferate.{{sfn | Ugwumadu | 2014 | p= 117}} The latter part of the follicular phase overlaps with the proliferative phase of the uterine cycle.{{sfn|Parker|2019|p=283}} As they mature, the ovarian follicles secrete increasing amounts of ], an estrogen. The estrogens initiate the formation of a new layer of endometrium in the uterus with the spiral arterioles.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=944}} | ||

| As estrogen levels increase, cells in the cervix produce a type of ]<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Simmons RG, Jennings V |title=Fertility awareness-based methods of family planning |journal=Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology |volume=66 |pages=68–82 |date=July 2020 |pmid=32169418 |doi=10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.12.003 |doi-access=free |type= Review}}</ref> that has a higher ] and is less ] than usual, rendering it more friendly to sperm.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|pp=936–937}} This increases the chances of fertilization, which occurs around day 11 to day 14.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p=957}} This cervical mucus can be detected as a vaginal discharge that is copious and resembles raw egg whites.<ref name= Su2017 /> For women who are practicing ], it is a sign that ovulation may be about to take place,<ref name= Su2017>{{cite journal |vauthors=Su HW, Yi YC, Wei TY, Chang TC, Cheng CM |title=Detection of ovulation, a review of currently available methods |journal=Bioeng Transl Med |volume=2 |issue=3 |pages=238–246 |date=September 2017 |pmid=29313033 |pmc=5689497 |doi=10.1002/btm2.10058 |type= Review}}</ref> but it does not mean ovulation will definitely occur.{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=45}} | |||

| ====Secretory phase==== | |||

| ==== Secretory phase ==== | |||

| The secretory phase is the final phase of the uterine cycle and it corresponds to the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle. During the secretory phase, the corpus luteum produces progesterone, which plays a vital role in making the ] receptive to ] of the ] and supportive of the early pregnancy, by increasing blood flow and uterine secretions and reducing the contractility of the ] in the uterus;<ref>{{cite book|author=Lombardi, Julian|title=Comparative Vertebrate Reproduction|publisher=Springer|year=1998|isbn=9780792383369|page=184|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=cqQX9RMPAegC&pg=PA184}}</ref> it also has the side effect of raising the woman's ].<ref name=tcoyf>Weschler (2002), pp.361-2</ref> | |||

| The secretory phase is the final phase of the uterine cycle and it corresponds to the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle. During the secretory phase, the corpus luteum produces progesterone, which plays a vital role in making the endometrium ] to the ] of a ] (a fertilized egg, which has begun to grow).<ref name="pmid30929718">{{cite journal |vauthors=Lessey BA, Young SL |title=What exactly is endometrial receptivity? |journal=Fertility and Sterility |volume=111 |issue=4 |pages=611–617|date=April 2019 |pmid=30929718 |doi=10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.02.009 |type= Review|doi-access=free }}</ref> ], ]s, and ]s are secreted into the uterus<ref name="pmid26661899">{{cite journal |vauthors=Salamonsen LA, Evans J, Nguyen HP, Edgell TA |title=The microenvironment of human implantation: determinant of reproductive success |journal=American Journal of Reproductive Immunology |volume=75 |issue=3 |pages=218–225 |date=March 2016 |pmid=26661899 |doi=10.1111/aji.12450 |type= Review|doi-access=free }}</ref> and the cervical mucus thickens.<ref name="pmid28801053">{{cite journal |vauthors=Han L, Taub R, Jensen JT |title=Cervical mucus and contraception: what we know and what we don't |journal=Contraception |volume=96 |issue=5 |pages=310–321 |date=November 2017 |pmid=28801053 |doi=10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.168 |type= Review}}</ref> In early pregnancy, progesterone also increases blood flow and reduces the ] of the ] in the uterus{{sfn|Tortora|2017|p= 942}} and raises ].<ref name="pmid28488202">{{cite journal |vauthors=Charkoudian N, Hart EC, Barnes JN, Joyner MJ |title=Autonomic control of body temperature and blood pressure: influences of female sex hormones |journal=Clinical Autonomic Research |volume=27 |issue=3 |pages=149–155 |date=June 2017 |pmid=28488202 |doi=10.1007/s10286-017-0420-z |s2cid=3773043 |url=https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/ws/files/152610705/Charkoudian_CAR_review_final.pdf |type=Review |access-date=27 February 2021 |archive-date=10 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200510013255/https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/ws/files/152610705/Charkoudian_CAR_review_final.pdf |url-status=live |hdl=1983/c0c1058c-553b-4563-8dd1-b047d9b672c1 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| If pregnancy does not occur the ovarian and uterine cycles start over again.{{sfn|Tortora|2017|page=600}} | |||

| == Ovulation suppression == | |||

| ==Anovulatory cycles and short luteal phases== | |||

| === Birth control === | |||

| {{Main|Anovulation}} | |||

| {{main|Hormonal contraception}} | |||

| Only two-thirds of overtly normal menstrual cycles are ovulatory, that is, cycles in which ovulation occurs.{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=45}} The other third lack ovulation or have a short luteal phase (less than ten days<ref name = Liu>{{cite book |vauthors= Liu AY, Petit MA, Prior JC|chapter= Exercise and the Hypothalamus: Ovulatory Adaptations|date=2020|doi=10.1007/978-3-030-33376-8_8|title=Endocrinology of Physical Activity and Sport|pages=124–147|veditors=Hackney AC, Constantini NW|series= Contemporary Endocrinology|publisher=Springer International Publishing|isbn=978-3-030-33376-8|s2cid= 243129220}}</ref>) in which progesterone production is insufficient for normal physiology and fertility.{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=46}} Cycles in which ovulation does not occur (]) are common in girls who have just begun menstruating and in women around menopause. During the first two years following menarche, ovulation is absent in around half of cycles. Five years after menarche, ovulation occurs in around 75% of cycles and this reaches 80% in the following years.<ref name="pmid29537383">{{cite journal |vauthors=Elmaoğulları S, Aycan Z |title=Abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents |journal=Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology |volume=10 |issue=3 |pages=191–197 |date=July 2018 |pmid=29537383 |pmc=6083466 |doi=10.4274/jcrpe.0014 }}</ref> Anovulatory cycles are often overtly identical to normally ovulatory cycles.{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=44}} Any alteration to balance of hormones can lead to anovulation. Stress, anxiety and ]s can cause a fall in GnRH, and a disruption of the menstrual cycle. Chronic anovulation occurs in 6–15% of women during their reproductive years. Around menopause, hormone feedback dysregulation leads to anovulatory cycles. Although anovulation is not considered a disease, it can be a sign of an underlying condition such as ].<ref>{{cite web | |||

| ], mainly for the purpose of reminding the woman to continue taking the pills.]] | |||

| |url=https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/253190-overview | |||

| While some forms of ] do not affect the menstrual cycle, hormonal contraceptives work by disrupting it. Progestogen ] decreases the pulse frequency of ] (GnRH) release by the ], which decreases the release of ] (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) by the ]. Decreased levels of FSH inhibit follicular development, preventing an increase in ] levels. Progestogen negative feedback and the lack of estrogen ] on LH release prevent a mid-cycle LH surge. Inhibition of follicular development and the absence of a LH surge prevent ovulation.<ref name=hatcher>{{cite book |author=Trussell, James |year=2007 |chapter=Contraceptive Efficacy |editor=Hatcher, Robert A. |display-editors=etal |title=Contraceptive Technology |edition=19th rev. |pages= |location=New York |publisher=Ardent Media |isbn=0-9664902-0-7 |chapterurl=http://www.contraceptivetechnology.com/table.html}}</ref><ref name=speroff>{{cite book |author=Speroff, Leon; Darney, Philip D. |year=2005 |chapter=Oral Contraception |title=A Clinical Guide for Contraception |edition=4th |pages=21–138 |location=Philadelphia |publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |isbn=0-7817-6488-2}}</ref><ref name=loose>{{cite book |editor1-first=Laurence L. |editor1-last=Brunton |editor2-first=John S. |editor2-last=Lazo |editor3-first=Keith |editor3-last=Parker |title=] |edition=11th |pages=1541–71| publisher=McGraw-Hill |location=New York |year=2005 | isbn=0-07-142280-3}}</ref> | |||

| |title=Anovulation | |||

| |vauthors=Hernandez-Rey, AE | |||

| |date=August 2, 2018 | |||

| |website=Medscape | |||

| |publisher=Medscape LLC | |||

| |access-date=March 30, 2021 | |||

| |archive-date=20 March 2021 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210320153521/https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/253190-overview | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> Anovulatory cycles or short luteal phases are normal when women are under stress or athletes increasing the intensity of training. These changes are reversible as the stressors decrease or, in the case of the athlete, as she adapts to the training.<ref name = Liu/> | |||

| == Menstrual health == | |||

| The degree of ovulation suppression in progestogen-only contraceptives depends on the ] activity and dose. Low dose progestogen-only contraceptives—traditional ]s, ]s ] and Jadelle, and ] Mirena—inhibit ovulation in about 50% of cycles and rely mainly on other effects, such as thickening of cervical mucus, for their contraceptive effectiveness.<ref name=glasier>{{cite book |last=] |first=Anna |editor=DeGroot, Leslie J.; Jameson, J. Larry (eds.) |title=Endocrinology |edition=5th |year=2006 |publisher=Elsevier Saunders |location=Philadelphia |isbn=0-7216-0376-9 |pages=3000–1 |chapter=Contraception}}</ref> Intermediate dose progestogen-only contraceptives—the progestogen-only pill Cerazette and the subdermal implant ]—allow some follicular development but more consistently inhibit ovulation in 97–99% of cycles. The same cervical mucus changes occur as with very low-dose progestogens. High-dose, progestogen-only contraceptives—the injectables ] and Noristerat—completely inhibit follicular development and ovulation.<ref name=glasier/> | |||

| ] viewed by ]. The round ] stained red in the center is surrounded by a layer of ]s, which are enveloped by the basement membrane and ]s. The magnification is around 1000 times. (])]] | |||

| Combined hormonal contraceptives include both an estrogen and a progestogen. Estrogen negative feedback on the anterior pituitary greatly decreases the release of FSH, which makes combined hormonal contraceptives more effective at inhibiting follicular development and preventing ovulation. Estrogen also reduces the incidence of irregular ].<ref name=hatcher/><ref name=speroff/><ref name=loose/> Several combined hormonal contraceptives—], ], and the ]—are usually used in a way that causes regular ]. In a normal cycle, ] occurs when estrogen and progesterone levels drop rapidly.<ref name=tcoyf/> Temporarily discontinuing use of combined hormonal contraceptives (a placebo week, not using patch or ring for a week) has a similar effect of causing the uterine lining to shed. If withdrawal bleeding is not desired, combined hormonal contraceptives may be ], although this increases the risk of breakthrough bleeding. | |||

| Although a normal and natural process,{{sfn|Prior|2020|p=50}} some women experience ] with symptoms that may include ], ], and ].<ref name="pmid32809533">{{cite book |last1=Gudipally |first1=Pratyusha R. |last2=Sharma |first2=Gyanendra K. |chapter=Premenstrual Syndrome |title=StatPearls |date=2022 |publisher=StatPearls Publishing |id={{NCBIBook2|NBK560698}} |pmid=32809533 }}</ref> More severe symptoms that affect daily living are classed as ] and are experienced by 3 to 8% of women.<ref name="Reed2018" /><ref name="pmid29298169">{{cite journal |vauthors=Appleton SM |title=Premenstrual syndrome: evidence-based evaluation and treatment |journal=Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology |volume=61 |issue=1 |pages=52–61 |date=March 2018 |pmid=29298169 |doi=10.1097/GRF.0000000000000339 |s2cid=28184066 |type= Review}}</ref><ref name="pmid32809533"/><ref name="pmid33030880">{{cite journal |vauthors=Ferries-Rowe E, Corey E, Archer JS |title=Primary Dysmenorrhea: Diagnosis and Therapy |journal=Obstetrics and Gynecology |volume=136 |issue=5 |pages=1047–1058 |date=November 2020 |pmid=33030880 |doi=10.1097/AOG.0000000000004096|doi-access=free }}</ref> ] (menstrual cramps or period pain) is felt as painful cramps in the abdomen that can spread to the back and upper thighs during the first few days of menstruation.<ref name="nhs1">{{cite web |title=Period pain |url=https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/period-pain/ |website=nhs.uk |access-date=12 November 2022 |language=en |date=19 October 2017}}</ref><ref name=Dysmenorrheastat>{{cite book |last1=Nagy |first1=Hassan |last2=Khan |first2=Moien AB |chapter=Dysmenorrhea |title=StatPearls |date=2022 |publisher=StatPearls Publishing |id={{NCBIBook2|NBK560834}} |pmid=32809669 }}</ref><ref name="pmid30098748">{{cite journal |vauthors=Baker FC, Lee KA |title=Menstrual cycle effects on sleep |journal=Sleep Medicine Clinics |volume=13 |issue=3 |pages=283–294 |date=September 2018 |pmid=30098748 |doi=10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.04.002 |s2cid=51968811 |type= Review}}</ref> Debilitating period pain is not normal and can be a sign of something severe such as ].<ref name="pmid33132854">{{cite journal |vauthors=Maddern J, Grundy L, Castro J, Brierley SM |title=Pain in endometriosis |journal=Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience |volume=14 |issue= |pages=590823 |date=2020 |pmid=33132854 |pmc=7573391 |doi=10.3389/fncel.2020.590823 |doi-access=free }}</ref> These issues can significantly affect a ] and quality of life and timely interventions can improve the lives of these women.<ref name="pmid31378287">{{cite journal |vauthors=Matteson KA, Zaluski KM |title=Menstrual health as a part of preventive health care |journal=Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America |volume=46 |issue=3 |pages=441–453 |date=September 2019 |pmid=31378287 |doi=10.1016/j.ogc.2019.04.004 |s2cid=199437314 |type= Review}}</ref> | |||

| There are common culturally communicated misbeliefs that the menstrual cycle affects women's moods, causes depression or irritability, or that menstruation is a painful, shameful or unclean experience. Often a woman's normal mood variation is falsely attributed to the menstrual cycle. Much of the research is weak, but there appears to be a very small increase in mood fluctuations during the luteal and menstrual phases, and a corresponding decrease during the rest of the cycle.{{sfn|Else-Quest|Hyde|2021|pp= 258–261}} Changing levels of estrogen and progesterone across the menstrual cycle exert systemic effects on aspects of physiology including the brain, metabolism, and musculoskeletal system. The result can be subtle physiological and observable changes to women's athletic performance including strength, aerobic, and anaerobic performance.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Carmichael MA, Thomson RL, Moran LJ, Wycherley TP |title=The impact of menstrual cycle phase on athletes' performance: a narrative review |journal=Int J Environ Res Public Health |volume=18 |issue=4 |date=February 2021 |page=1667 |pmid=33572406 |pmc=7916245 |doi=10.3390/ijerph18041667 |type=Review|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| === Breastfeeding === | |||

| {{main|Lactational amenorrhea method}} | |||

| ] causes negative feedback to occur on pulse secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). Depending on the strength of the negative feedback, breastfeeding women may experience complete suppression of follicular development, follicular development but no ovulation, or normal menstrual cycles may resume.<ref name=mcneilly>{{cite journal | author = McNeilly AS | title = Lactational control of reproduction | journal = Reprod. Fertil. Dev. | volume = 13 | issue = 7–8 | pages = 583–90 | year = 2001 | pmid = 11999309 | doi = 10.1071/RD01056 | url = http://www.publish.csiro.au/journals/abstractHTML.cfm?J=RD&V=13&I=8&F=RD01056abs.XML }}</ref> Suppression of ovulation is more likely when suckling occurs more frequently.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite book | first=John | last=Kippley |author2=Sheila Kippley | year=1996 | title=The Art of Natural Family Planning | edition=4th | publisher=The Couple to Couple League | location=Cincinnati, OH | isbn=0-926412-13-2 | page=347}}</ref> The production of ] in response to suckling is important to maintaining lactational amenorrhea.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Stallings JF, Worthman CM, Panter-Brick C, Coates RJ | title = Prolactin response to suckling and maintenance of postpartum amenorrhea among intensively breastfeeding Nepali women | journal = Endocr. Res. | volume = 22 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–28 | date = February 1996 | pmid = 8690004 | doi = 10.3109/07435809609030495 }}</ref> On average, women who are fully breastfeeding whose infants suckle frequently experience a return of menstruation at fourteen and a half months postpartum. There is a wide range of response among individual breastfeeding women, however, with some experiencing return of menstruation at two months and others remaining amenorrheic for up to 42 months postpartum.<ref>{{cite web | title = Breastfeeding: Does It Really Space Babies? | work = The Couple to Couple League International | publisher = Internet Archive | date = 17 January 2008 | url = http://www.ccli.org/nfp/ebf/spacebabies.php | accessdate = 21 September 2008 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20080117232155/http://www.ccli.org/nfp/ebf/spacebabies.php |archivedate = 17 January 2008}}, which cites: | |||

| :{{cite journal | author = Kippley SK, Kippley JF | title = The relation between breastfeeding and amenorrhea | journal = Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing | volume = 1 | issue = 4 | pages = 15–21 | date = November–December 1972 | pmid = 4485271 | doi = 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1972.tb00558.x }} | |||