| Revision as of 12:54, 5 August 2006 editNixer (talk | contribs)8,222 edits rv User:Roitr/sockpuppetry← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:52, 24 December 2024 edit undo2a00:23c7:9b87:b101:2c24:d705:7026:7f32 (talk)No edit summaryTags: Manual revert Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Empire in Eurasia (1721–1917)}} | |||

| {| border=1 align=right cellpadding=4 cellspacing=0 width=300 style="margin: 0 0 1em 1em; background: #f9f9f9; border: 1px #aaaaaa solid; border-collapse: collapse; font-size: 95%;" | |||

| {{For|other places with a similar name|Russia (disambiguation)}} | |||

| |+<big>'''Pоссийская Империя''' <br> '''Rossiyskaya Imperiya'''</big> | |||

| {{Pp-move}} | |||

| | align="center" colspan="2"| | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2022}} | |||

| {| border=0 cellpadding=2 cellspacing=0 style="background:#f9f9f9; text-align:center;" | |||

| {{Use American English|date=October 2023}} | |||

| | width="130px"|{{border|]}}<br>{{border|]}} || align=center width=130px| ]<!-- Yes, they are state seals: "Государственная печать" as was defined by law --> ] | |||

| {{Infobox country | |||

| | conventional_long_name = Russian Empire | |||

| | native_name = {{native name|ru|Россійская Имперія}}<br />{{transliteration|ru|Rossíyskaya Impériya}} | |||

| | common_name = Imperial Russia | |||

| | image_flag = Flag of Russia.svg | |||

| | image_flag2 = Flag of the Russian Empire (black-yellow-white).svg | |||

| | flag_type = ]<br/>] | |||

| | image_coat = Lesser coat of arms of the Russian Empire.svg | |||

| | symbol_type = {{Nowrap|]}}<br/>(1883–1917) | |||

| | national_motto = {{Lang|ru|С нами Бог!}}<br/>('God is with us!') | |||

| | national_anthem = {{Lang|ru|Боже, Царя храни!|nocat=y}}» (1833–1917)<br/>("]"){{Parabr}}{{Center|]}} | |||

| {{Lang|ru|Гром победы, раздавайся!|nocat=y}}» (1791–1816)<br/>("]") {{small|(unofficial)}} {{Parabr}}{{Center|]}}{{Parabr}} | |||

| {{Lang|ru|Коль славен наш Господь в Сионе|nocat=y}}» (1794–1816)<br/>("]") {{small|(unofficial)}}{{Parabr}}{{Center|]}}{{Parabr}} | |||

| {{Lang|ru|Молитва русских|nocat=y}}» (1816–1833)<br/>("]"){{Parabr}}{{Center| | |||

| ]|}}{{Parabr}} | |||

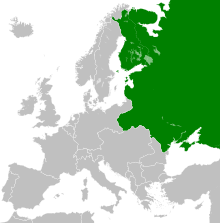

| | image_map = {{Switcher|]{{Parabr}}{{Legend0|#145a37|Russia in 1914}} {{Legend0|#148237|Lost in 1856–1914}}<br/>{{Legend0|#5faf5f|Spheres of influence}} {{Legend0|#00d321|Protectorates{{Efn|Principalities of ] and ] in 1829–1856.}}}}<br/>{{Parabr}}|Show globe|]|Show map of Europe|]|Show all controlled<br/>territories (1866)|default=1}} | |||

| | capital = ]{{Efn|In 1914, the city was renamed ] to reflect anti-German sentiments of Russia during ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=St. Petersburg through the Ages |url=https://forumspb.com/en/o-sankt-peterburge/history |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220806095844/https://forumspb.com/en/o-sankt-peterburge/history |archive-date=6 August 2022 |access-date=6 August 2022 |website=St. Petersburg International Economic Forum}}</ref>}}<br/>{{Nowrap|(1721–1728; 1730–1917)}}<br/>] <br/>(1728–1730)<ref>"", Rusmania. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220319083640/https://rusmania.com/history-of-russia/18th-century |date=19 March 2022}}.</ref> | |||

| | largest_city = ] | |||

| | official_languages = ] | |||

| | recognized_languages = ], ] (in ]), ], ], ] (in ]) | |||

| | religion = {{Ublist|item_style=white-space;|{{Tree list}} | |||

| * 84.2% ] | |||

| ** 69.3% ] (])<ref>{{Cite book |last=Coleman |first=Heather J. |title=Orthodox Christianity in Imperial Russia: A Source Book on Lived Religion |publisher=Indiana University Press |date=2014 |isbn=978-0-2530-1318-7 |page=4 |quote=After all, Orthodoxy was both the majority faith in the Russian Empire – approximately 70 percent subscribed to this faith in the 1897 census–and the state religion.}}</ref> | |||

| ** 9.2% ] | |||

| ** 5.7% Other ] | |||

| {{Tree list/end}}|11.1% ]|4.2% ]|0.3% ]|0.2% Others}} | |||

| | religion_year = ] | |||

| | government_type = Unitary ]<br/>(1721–1906)<br/>Unitary ] ]<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Williams |first=Beryl |date=1 December 1994 |title=The concept of the first Duma: Russia 1905–1906 |journal=Parliaments, Estates and Representation |volume=14 |issue=2 |pages=149–158 |doi=10.1080/02606755.1994.9525857}}</ref><br/>(1906–1917) | |||

| | title_leader = ] | |||

| | leader1 = ] | |||

| | year_leader1 = 1721–1725 (first) | |||

| | leader4 = ] | |||

| | year_leader4 = 1894–1917 (last) | |||

| | title_deputy = {{Longitem|]/]}} | |||

| | deputy1 = {{Nowrap|]{{Efn|As Chairman of the ].}}}} | |||

| | year_deputy1 = 1810–1812 (first) | |||

| | deputy2 = ]{{Efn|As Prime Minister.}} | |||

| | year_deputy2 = 1917 (last) | |||

| | legislature = ]<ref>"The Sovereign Emperor exercises legislative power in conjunction with the State Council and State Duma". ], {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190608203053/http://www.imperialhouse.ru/en/dynastyhistory/dinzak1/441.html|date=8 June 2019}}</ref> | |||

| | house1 = ]<br/>(1810–1917) | |||

| | house2 = ]<br/>(1905–1917) | |||

| | event_pre = ] | |||

| | date_pre = 10 September 1721 | |||

| | event_start = Proclaimed | |||

| | date_start = 2 November | |||

| | year_start = 1721 | |||

| | event1 = ] | |||

| | date_event1 = 4 February 1722 | |||

| | event2 = ] | |||

| | date_event2 = {{Nowrap|26 December 1825}} | |||

| | event3 = ] | |||

| | date_event3 = 3 March 1861 | |||

| | event4 = ] of ] | |||

| | date_event4 = 18 October 1867 | |||

| | event5 = ] | |||

| | date_event5 = Jan 1905 – Jul 1907 | |||

| | event6 = ] | |||

| | date_event6 = 30 October 1905 | |||

| | event7 = {{Nowrap|] adopted}} | |||

| | date_event7 = 6 May 1906 | |||

| | event8 = ] | |||

| | date_event8 = 8–16 March 1917 | |||

| | event_end = Proclamation of the ] | |||

| | date_end = 14 September | |||

| | year_end = 1917 | |||

| | stat_year1 = 1895 | |||

| | stat_area1 = 22800000 | |||

| | ref_area1 = <ref>{{Cite journal |first=Rein |last=Taagepera |author-link=Rein Taagepera |date=September 1997 |title=Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia |url=http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/3cn68807 |url-status=live |journal=] |volume=41 |issue=3 |pages=475–504 |doi=10.1111/0020-8833.00053 |jstor=2600793 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181119114740/https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3cn68807 |archive-date=19 November 2018 |access-date=28 June 2019}}; {{Cite journal |last1=Turchin |first1=Peter |last2=Adams |first2=Jonathan M. |last3=Hall |first3=Thomas D. |date=December 2006 |title=East-West Orientation of Historical Empires |url=http://jwsr.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/jwsr/article/view/369/381 |url-status=live |journal=Journal of World-Systems Research |volume=12 |issue=2 |page=223 |issn=1076-156X |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160917031715/http://jwsr.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/jwsr/article/view/369/381 |archive-date=17 September 2016 |access-date=11 September 2016}}</ref> | |||

| | stat_year2 = ] | |||

| | stat_pop2 = 125,640,021 | |||

| | stat_year3 = 1910<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Price of Expansion: The Nationality Problem in Russia of the Eighteenth-Early Twentieth Centuries |url=https://src-h.slav.hokudai.ac.jp/sympo/97summer/mironov.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230308110647/https://src-h.slav.hokudai.ac.jp/sympo/97summer/mironov.html |archive-date=8 March 2023 |access-date=20 July 2024 |website=Slavic Research Center}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Population of the Major European Countries in the 19th Century |url=https://dmorgan.web.wesleyan.edu/materials/population.htm |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240228222116/https://dmorgan.web.wesleyan.edu/materials/population.htm |archive-date=28 February 2024 |access-date=20 July 2024 |website=Wesleyan University}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Population of Russia and the USSR, 1913 to 1928 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/4812467 |access-date=20 July 2024 |website=Research Gate}}</ref> | |||

| | stat_pop3 = 161,000,000 | |||

| | currency = ] | |||

| | p1 = Tsardom of Russia{{!}}{{Nowrap|Tsardom of}}<br/>Russia | |||

| | flag_p1 = Flag of Oryol ship (variant).svg | |||

| | s1 = Russian Provisional Government{{!}}Provisional Government | |||

| | flag_s1 = Flag of Russia.svg | |||

| | s2 = Russian Republic | |||

| | flag_s2 = Flag of Russia.svg | |||

| | demonym = ] | |||

| }} | |||

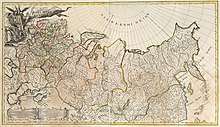

| The '''Russian Empire'''{{Efn|{{Lang-rus|Россійская Имперія|r=Rossíyskaya Impériya|p=rɐˈsʲijskəjə ɪmˈpʲerʲɪjə|a=Ru-Российская империя.ogg}}; {{Langx|ru|Российская Империя|label=none}} in ].}}{{Efn|Historiographically known as '''Imperial Russia''', '''Tsarist Russia''', '''pre-] Russia''', or simply '''Russia'''.}} was a vast ] that spanned most of northern ] from its proclamation in November 1721 until the proclamation of the ] in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about {{Convert|22,800,000|km2|sqmi|sp=us|abbr=on}}, roughly one-sixth of the world's landmass, making it the ], behind only the ] and ] empires. It also ] North America between 1799 and 1867. The empire's ] census, the only one it conducted, found a population of 125.6 million with considerable ethnic, linguistic, religious, and socioeconomic diversity. | |||

| The rise of the Russian Empire coincided with the decline of its rivals: the ], the ], ], the ], and ]. From the 10th to 17th centuries, the Russians had been ruled by a noble class known as the ]s, above whom was an absolute monarch titled the ]. The groundwork of the Russian Empire was laid by ] ({{Reign|1462|1505}}), who greatly expanded his domain, established a centralized Russian ], and secured independence against the ]. His grandson, ] ({{Reign|1533|1584}}), became in 1547 the first Russian monarch to be crowned "]". Between 1550 and 1700, the Russian state grew by an average of {{Convert|35,000|km2|sp=us|abbr=on}} per year. Major events during this period include the transition from the ] to the ] dynasties, the ], and the reign of ] ({{Reign|1682|1725}}).{{Sfn|Pipes|1974|p=83}} | |||

| ] transformed the tsardom into an empire, and fought numerous wars that turned a vast realm into a major European power. He moved the Russian capital from ] to the new model city of ], which marked the birth of the imperial era, and led a cultural revolution that introduced a modern, scientific, rationalist, and Western-oriented system. ] ({{Reign|1762|1796}}) presided over further expansion of the Russian state by conquest, ], and diplomacy, while continuing Peter's policy of modernization towards a Western model. ] ({{Reign|1801|1825}}) helped defeat the militaristic ambitions of ] and subsequently constituted the ], which aimed to restrain the rise of secularism and liberalism across Europe. Russia further expanded to the west, south, and east, strengthening its position as a European power. Its victories in the ] were later checked by defeat in the ] (1853–1856), leading to a period of reform and ].<ref name=":22">{{Cite web |title=The Great Game, 1856–1907: Russo-British Relations in Central and East Asia {{!}} Reviews in History |url=https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/1611 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220410163636/https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/1611 |archive-date=10 April 2022 |access-date=8 October 2021 |website=reviews.history.ac.uk |language=en}}</ref> ] ({{Reign|1855|1881}}) initiated ], most notably the ] of all 23 million serfs. | |||

| From 1721 until 1762, the Russian Empire was ruled by the ]; its matrilineal branch of patrilineal ] descent, the ], ruled from 1762 until 1917. By the start of the 19th century, Russian territory extended from the ] in the north to the ] in the south, and from the ] in the west to ] in the east. By the end of the 19th century, Russia had expanded its control over ], most of ] and parts of ]. Notwithstanding its extensive territorial gains and great power status, the empire entered the 20th century in a perilous state. A devastating ] killed hundreds of thousands and led to popular discontent. As the last remaining ] in Europe, the empire saw rapid political radicalization and the growing popularity of revolutionary ideas such as ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Russian Empire |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Russian-Empire/Russification-policy#ref340502 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221225190907/https://www.britannica.com/place/Russian-Empire/Russification-policy#ref340502 |archive-date=25 December 2022 |access-date=2022-08-14 |website=]}}</ref> After the ], ] authorized the creation of a national parliament, the ], although he still retained absolute political power. | |||

| When Russia entered the First World War on the side of the ], it suffered a series of defeats that further galvanized the population against the emperor. In 1917, mass unrest among the population and mutinies in the army culminated in the ], which led to the abdication of Nicholas II, the formation of the ], and the proclamation of the first ]. Political dysfunction, continued involvement in the widely unpopular war, and widespread food shortages resulted in ]. The republic was overthrown in the ] by the ], who proclaimed the ] and whose ] ended Russia's involvement in the war, but who nevertheless were opposed by various factions known collectively as the ].<ref name="geoffreyswain">{{Cite book |first=Geoffrey |last=Swain |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_a3pAgAAQBAJ |title=Trotsky and the Russian Revolution |publisher=Routledge |date=2014 |isbn=978-1-3178-1278-4 |page= |ol=37192398M |quote=The first government to be formed after the February Revolution of 1917 had, with one exception, been composed of liberals. |access-date=20 June 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150919081708/https://books.google.com/books?id=_a3pAgAAQBAJ&pg=PR15 |archive-date=19 September 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="alexanderrabinowitch">{{Cite book |first=Alexander |last=Rabinowitch |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BEoBCGJ4VqYC&pg=PA1 |title=The Bolsheviks in Power: The First Year of Soviet Rule in Petrograd |publisher=Indiana UP |date=2008 |isbn=978-0-2532-2042-4 |page=1 |access-date=20 June 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150910221609/https://books.google.com/books?id=BEoBCGJ4VqYC&pg=PA1 |archive-date=10 September 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> During the resulting ], the Bolsheviks conducted the ]. After emerging victorious, they established the ] across most of the Russian territory; it would be one of four continental empires to collapse ], along with ], ], and the ].<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vZokDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA331 |title=Decades of Reconstruction |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=2017 |isbn=978-1-1071-6574-8 |editor-last=Planert |editor-first=Ute |page=331 |access-date=5 January 2023 |editor-last2=Retallack |editor-first2=James |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230211110511/https://books.google.com/books?id=vZokDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA331 |archive-date=11 February 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Main|History of Russia}} | |||

| The foundations of a Russian national state were laid in the late 15th century during the reign of ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bushkovitch |first=Paul |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Le-n7ZYjGWkC |title=A Concise History of Russia |date=2012 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-5215-4323-1 |location=New York |page=48 |quote=Ivan III in his own time already had the reputation of the builder of the Russian state... The consolidation of Russia as a state was not just a territorial issue, for Ivan also began the development of a state apparatus... |access-date=30 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230423152841/https://books.google.com/books?id=Le-n7ZYjGWkC |archive-date=23 April 2023 |url-status=live}}; {{Cite book |last=Millar |first=James R. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R-KYwQEACAAJ |title=Encyclopedia of Russian History |date=2004 |publisher=Macmillan Reference USA |isbn=978-0-0286-5693-9 |location=New York |page=687 |quote=Under Ivan III's reign, the uniting of separate Russian principalities into a centralized state made great and rapid progress. |access-date=30 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231026094841/https://books.google.com/books?id=R-KYwQEACAAJ |archive-date=26 October 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> By the early 16th century, all of the semi-independent and petty princedoms in Russia had been unified with Moscow.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Moss |first=Walter G. |title=A History of Russia Volume 1: To 1917 |date=2003 |publisher=Anthem Press |isbn=978-0-8572-8752-6 |page=88 |language=en |quote=Ivan III (1462–1505) and his son, Vasili III (1505–1533), completed Moscow's quest to dominate Great Russia. Of the two rulers, Ivan III (the Great) accomplished the most, and Russian historians have called him 'the gatherer of the Russian lands'.}}</ref> During the reign of ], the khanates of ] and ] were conquered by Russia in the mid-16th century, leading to the development of an increasingly multinational state.{{Sfn|Moss|2003|page=131}} | |||

| ===Population=== | |||

| Much of Russia's expansion occurred in the 17th century, culminating in the ], the ] which led to the incorporation of ], and the ]. Poland was partitioned by its rivals in 1772–1815;most of its land and population being taken under Russian rule. Most of the empire's growth in the 19th century came from gaining territory in central and eastern Asia south of Siberia.<ref>{{Harvnb|Catchpole|1974|pp=8–31}}; Gilbert, Martin. ''Atlas of Russian history'' (1993) pp 33–74.</ref> By 1795, after the ], Russia became the most populous state in Europe, ahead of ]. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! width="60" | Year | |||

| ! width="240pt" | Population of Russia (millions)<ref>{{Harvnb|Catchpole|1974|p=25}}; {{Cite web |title=Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. |trans-title=First general census of the population of the Russian Empire in 1897 |url=http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_lan_97.php |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120204034344/http://demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/rus_lan_97.php |archive-date=4 February 2012 |access-date=26 March 2021 |website=Demoscope Weekly |language=ru}}</ref> | |||

| ! width="300pt" | Notes | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1720 | |||

| | 15.5 | |||

| | includes new ] & ] territories | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1795 | |||

| | 37.6 | |||

| | includes part of Poland | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1812 | |||

| | 42.8 | |||

| | includes ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1816 | |||

| | 73.0 | |||

| | includes ], ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1897 | |||

| | 125.6 | |||

| | ],{{Efn|First and only census carried out in the Russian Empire.}} excludes Grand Duchy of Finland | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1914 | |||

| | 164.0 | |||

| | includes new Asian territories | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |} | |} | ||

| ===Background=== | |||

| {{Main|Government reform of Peter the Great}} | |||

| ] in the ]]] | |||

| ]'', painted by ] in 1862|thumb]] | |||

| The foundations of the Russian Empire were laid during ]'s ], which significantly altered Russia's political and social structure,<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |date=2017 |title=Peter I |encyclopedia=] |url=https://bigenc.ru/domestic_history/text/3826088 |access-date=20 November 2022 |last=Anisimov |first=Yevgeniya |language=ru |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220104103730/https://bigenc.ru/domestic_history/text/3826088 |archive-date=4 January 2022 |url-status=dead}}</ref> and as a result of the ] which strengthened Russia's standing on the world stage.<ref name=":0"/> Internal transformations and military victories contributed to the transformation of Russia into a great power, playing a major role in European politics.<ref name="Osipov">{{Cite encyclopedia |date=2015 |title=Romania to Saint-Jean-de-Luz |encyclopedia=] |url=https://bigenc.ru/military_science/text/3543492 |access-date=20 November 2022 |editor-last=Osipov |editor-first=Yuriy |series=2004–2017 |volume=29 |pages=617–20 |language=ru |isbn=978-5-8527-0366-8 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210417123305/https://bigenc.ru/military_science/text/3543492 |archive-date=17 April 2021 |chapter=The Great Northern War 1700–21 |url-status=dead}}</ref> On {{OldStyleDate|2 November|1721|22 October}}, the day of the announcement of the Treaty of Nystad, the ] and ] invested the tsar with the titles of Peter the Great,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Madariaga |first1=Isabel De |title=Politics and Culture in Eighteenth-Century Russia: Collected Essays by Isabel de Madariaga |date=17 June 2014 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-88190-2 |pages=15–16 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=omjXAwAAQBAJ |language=en}}</ref> '']'' (father of the fatherland),{{efn|{{Langx|ru|Отец отечества|Otets otechestva}}, {{IPA|ru|ɐˈtʲet͡s ɐˈtʲet͡ɕɪstvə|IPA}}}} and ].{{efn|{{Langx|ru|Император и Самодержец Всероссийский|Imperator i Samoderzhets Vserossiyskiy}}}}<ref>{{Cite web |title=Прошение сенаторов к царю Петру I о принятии им титула "Отца Отечества, императора Всероссийского, Петра Великого" |trans-title=Petition of the senators to Tsar Peter I for the adoption of the title of "Father of the Fatherland, Emperor of all the Russias, Peter the Great" |url=http://www.school.edu.ru/collections/collectionitem/11664 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180829070929/http://www.school.edu.ru/collections/collectionitem/11664 |archive-date=2018-08-29 |access-date=2018-07-09 |website=Russian educational portal {{!}} Historical documents}}</ref>{{sfn|Feldbrugge|2017|p=152}} The adoption of the title of ''imperator'' by Peter I is usually seen as the beginning of the "imperial" period of Russia.{{Efn|Originally there was no distinction between the titles '']'' and '']''. However, ''tsar'' was also used to refer to other monarchs below the rank of "]" (according to the Western European view), and thus Westerners began to translate ''tsar'' as '']'' ("king"). By adopting the title ''imperator'', Peter claimed equality to the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Madariaga |first=Isabel De |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=omjXAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA40 |title=Politics and Culture in Eighteenth-Century Russi |date=2014 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-88190-2 |pages=40–42|quote=This explains much of the difficulty encountered by Peter I when he adopted the title ''Imperator''. The etymological origin of the word ''tsar'' had been glossed over and the title had been devalued.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ageyeva, Olga |date=1999 |title=ТИТУЛ "ИМПЕРАТОР" И ПОНЯТИЕ "ИМПЕРИЯ" В РОССИИ В ПЕРВОЙ ЧЕТВЕРТИ XVIII ВЕКА |trans-title=The title "emperor" and the concept of "empire" in Russia in the first quarter of the 18th century |url=http://www.historia.ru/1999/05/ageyeva.htm |journal=World of History: Russian Electronic Journal |language=ru |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220316061503/http://www.historia.ru/1999/05/ageyeva.htm |archive-date=2022-03-16 |number=5}}</ref>}}<ref>{{Cite thesis |last=Solovyov |first=Yevgeny |title=Петр I в Отечественной Историографии: Конца XVIII – Начала XX ВВ |degree=Doctor of Historical Sciences |url=http://www.dissercat.com/content/petr-i-v-otechestvennoi-istoriografii-kontsa-xviii-nachala-xx-vv |place=Moscow |language=ru |trans-title=Peter I in Russian historiography of the late 18th – early 20th centuries |date=2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180707094918/http://www.dissercat.com/content/petr-i-v-otechestvennoi-istoriografii-kontsa-xviii-nachala-xx-vv |archive-date=7 July 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Following the reforms, the governance of Russia by an ] was enshrined. The Military Regulations made a note of the ] of the regime.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Drozdek |first=Adam |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9ygSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PR10 |title=Theological Reflection in Eighteenth-Century Russia |date=2021 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-1-7936-4184-7 |pages=x}}</ref> During the reign of Peter I, the last vestiges of the independence of the ]s were lost. He transformed them into the new ], who were obedient nobles that served the state for the rest of their lives. He also introduced the ] and equated the '']'' with an ]. Russia's ] was built by Peter the Great, along with an ] that was reformed in the manner of European style and educational institutions (the ]). Civil lettering was adopted during Peter I's reign, and the first Russian newspaper, '']'', was published. Peter I promoted the advancement of science, particularly ] and ], trade, and industry,<ref>{{Cite thesis |last=Dubakov |first=Maxim Valentinovich |title=Промышленно-торговая политика Петра 1 |access-date=4 April 2023 |degree=Dissertation abstract |url=https://economy-lib.com/promyshlenno-torgovaya-politika-petra-1 |language=ru |trans-title=Industrial and trade policy of Peter I |date=2004 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180414233833/http://economy-lib.com/promyshlenno-torgovaya-politika-petra-1 |archive-date=14 April 2018 |url-status=live |location=Moscow}}</ref> including shipbuilding, as well as the growth of the Russian educational system. Every tenth Russian acquired an education during Peter I's reign, when there were 15 million people in the country.<ref>{{Cite thesis |last=Yarysheva |first=Svetlana |title=Formation of the system of Russian education during the reforms of Peter I |access-date=20 November 2022 |degree=Abstract dissertion |url=http://www.dissercat.com/content/stanovlenie-sistemy-rossiiskogo-obrazovaniya-v-gody-reform-petra-i |place=Pyatigorsk |language=ru |date=2001 |archive-date=29 June 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180629211159/http://www.dissercat.com/content/stanovlenie-sistemy-rossiiskogo-obrazovaniya-v-gody-reform-petra-i |url-status=live}}</ref> The city of ], which was built in 1703 on territory along the ] that had been conquered during the Great Northern War, served as the state's capital. | |||

| This concept of the triune Russian people, composed of the ], the ], and the ], was introduced during the reign of Peter I, and it was associated with the name of Archimandrite ] (1621), the Archimandrite of the ] and expanded upon in the writings of an associate of Peter I, Archbishop Professor ]. Several of Peter I's associates are well-known, including ], ], ], ], ], ], and Alexey Kelin. During Peter's reign, the obligation of the nobility to serve was reinforced, and serf labor played a significant role in the growth of the industry, reinforcing traditional socioeconomic structures. The volume of the country's international trade turnover increased as a result of Peter I's industrial reforms. However, imports of goods overtook exports, strengthening the role of foreigners in Russian trade, particularly the ] domination.<ref>{{Cite thesis |last=Novosyolova |first=Nataliya Ivanovna |title=Внешняя торговля и финансово-экономическая политика Петра I |access-date=5 April 2023 |degree=Abstract dissertion |url=http://www.dissercat.com/content/vneshnyaya-torgovlya-i-finansovo-ekonomicheskaya-politika-petra-i |place=Saint Petersburg |language=ru |trans-title=Foreign trade and financial and economic policy of Peter I |date=1999 |archive-date=29 June 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180629211209/http://www.dissercat.com/content/vneshnyaya-torgovlya-i-finansovo-ekonomicheskaya-politika-petra-i |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===18th century=== | |||

| {{Main|History of Russia (1721–1796)}} | |||

| ====Peter the Great (1682–1725)==== | |||

| Peter I ({{Reign|1682|1725}}), also known as Peter the Great, played a major role in introducing the European state system into Russia. While the empire's vast lands had a population of 14 million, grain yields trailed behind those in the West.{{Sfn|Pipes|1974|pp= |loc=Chapter 1: The Environment and its Consequences}} Nearly the entire population was devoted to agriculture, with only a small percentage living in towns. The class of '']s'', whose status was close to that of ], remained a major institution in Russia until 1723, when Peter converted household kholops into house ], thus counting them for poll taxation. Russian agricultural kholops had been formally converted into serfs earlier in 1679. They were largely tied to the land, in a feudal sense, until the late 19th century. | |||

| ] | |||

| Peter's first military efforts were directed against the ]. His attention then turned to the north. Russia lacked a secure northern seaport, except at ] on the ], where the harbor was frozen for nine months a year. Access to the ] was blocked by Sweden, whose territory enclosed it on three sides. Peter's ambitions for a "window to the sea" led him, in 1699, to make a secret alliance with ], the ], and ] against ]; they conducted the ], which ended in 1721 when an exhausted Sweden asked for peace with Russia. | |||

| ] officially proclaimed the Russian Empire in 1721 and became its first emperor. He instituted ] and oversaw the transformation of Russia into a major European power. Painting by ], 1717.]] | |||

| As a result, Peter acquired four provinces situated south and east of the ], securing access to the sea. There he built Russia's new capital, ], on the ] river, to replace Moscow, which had long been Russia's cultural center. This relocation expressed his intent to adopt European elements for his empire. Many of the government and other major buildings were designed under ] influence. In 1722, he turned his aspirations toward increasing Russian influence in the ] and the ] at the expense of the weakened ]. He made ] the base of military efforts against Persia, and waged the first full-scale war ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Cracraft |first=James |title=The Revolution of Peter the Great |date=2003 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-6740-1196-0}}</ref> Peter the Great ] several areas of Iran to Russia, which after the death of Peter were returned in the 1732 ] and 1735 ] as a deal to oppose the Ottomans.<ref>{{Cite web |title=BOUNDARIES ii. With Russia |url=https://iranicaonline.org/articles/boundaries-ii |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210905134755/https://iranicaonline.org/articles/boundaries-ii |archive-date=5 September 2021 |access-date=15 October 2021 |website=iranicaonline.org |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| Peter ] based on the latest political models of the time, molding Russia into an ] state. He replaced the old ] (council of nobles) with a nine-member ], in effect a supreme council of state. The countryside was divided into new ]. Peter told the Senate that its mission was to collect taxes, and tax revenues tripled over the course of his reign. Meanwhile, all vestiges of local self-government were removed. Peter continued and intensified his predecessors' requirement of state service from all nobles, in the ]. | |||

| As part of Peter's reorganization, he also enacted a ]. The ] was partially incorporated into the country's administrative structure, in effect making it a tool of the state. Peter abolished the ] and replaced it with a collective body, the ], which was led by a ].{{Sfn|Hughes|1998}} | |||

| Peter died in 1725, leaving an unsettled succession. After a short reign by his widow, ], the crown passed to Empress ]. She slowed the reforms and led a successful ]. This resulted in a significant weakening of the ], an Ottoman vassal and long-term Russian adversary. | |||

| The discontent over the dominant positions of ] in Russian politics resulted in Peter I's daughter ] being put on the Russian throne. Elizabeth supported the arts, architecture, and the sciences (for example, the founding of ]). But she did not carry out significant structural reforms. Her reign, which lasted nearly 20 years, is also known for Russia's involvement in the ], where it was successful militarily, but gained little politically.<ref>Philip Longworth and John Charlton, ''The Three Empresses: Catherine I, Anne and Elizabeth of Russia'' (1972).</ref> | |||

| ====Catherine the Great (1762–1796)==== | |||

| {{See also|Russia and the American Revolution#Russian Diplomacy during the War}} | |||

| ], who reigned from 1762 to 1796, continued the empire's expansion and modernization. Considering herself an ], she played a key role in the ] (painted in the 1780s).]] | |||

| ] | |||

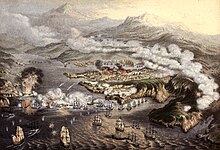

| ] on December 22, 1790'', by Russian troops under the command of ]. Suvorov's victory was immortalized with the empire's newfound national anthem: "]".]] | |||

| ] was a German princess who married ], the German heir to the Russian crown. After the death of Empress Elizabeth, Catherine came to power after she effected a coup d'état against her very unpopular husband. She contributed to the resurgence of the ] that began after the death of Peter the Great, abolishing State service and granting them control of most state functions in the provinces. She also removed the ] instituted by Peter the Great.<ref>Isabel De Madariaga, ''Russia in the Age of Catherine the Great'' (Yale University Press, 1981)</ref> | |||

| Catherine extended Russian political control over the lands of the ], supporting the ]. However, the cost of these campaigns further burdened the already oppressive social system, under which serfs were required to spend almost all of their time laboring on their owners' land. A major peasant uprising took place in 1773, after Catherine legalized the selling of serfs separate from land. Inspired by a ] named ] and proclaiming "Hang all the landlords!", the rebels threatened to take Moscow before they were ruthlessly suppressed. Instead of imposing the traditional punishment of drawing and quartering, Catherine issued secret instructions that the executioners should execute death sentences quickly and with minimal suffering, as part of her effort to introduce compassion into the law.<ref>John T. Alexander, ''Autocratic politics in a national crisis: the Imperial Russian government and Pugachev's revolt, 1773–1775'' (1969).</ref> | |||

| She furthered these efforts by ordering the public trial of ], a high-ranking noblewoman, on charges of torturing and murdering serfs. Whilst these gestures garnered Catherine much positive attention from Europe during the ], the specter of revolution and disorder continued to haunt her and her successors. Indeed, her son ] ] in his short reign aimed directly against the spread of French culture in response to ]. | |||

| In order to ensure the continued support of the nobility, which was essential to her reign, Catherine was obliged to strengthen their authority and power at the expense of the serfs and other lower classes. Nevertheless, Catherine realized that serfdom must eventually be ended, going so far in her '']'' ("Instruction") to say that serfs were "just as good as we are" – a comment received with disgust by the nobility. Catherine advanced Russia's southern and western frontiers, ] against the Ottoman Empire for territory near the ], and incorporating territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during the ], alongside ] and ]. As part of the ], signed with the Georgian ], and her own political aspirations, Catherine waged a new war ] in 1796 after they had invaded ]. Upon achieving victory, she established Russian rule over it and expelled the newly established Persian garrisons in the Caucasus. | |||

| Catherine's expansionist policy caused Russia to develop into a major European power,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Massie |first=Robert K. |title=Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman |date=2011 |publisher=Random House |isbn=978-1-5883-6044-1}}</ref> as did the ] and the Golden age in Russia. But after Catherine died in 1796, she was succeeded by her son, ]. He brought Russia into a ] against the new-revolutionary ] in 1798. Russian commander Field Marshal ] led the ],—he inflicted a series of defeats on the French; in particular, the ] in 1799. | |||

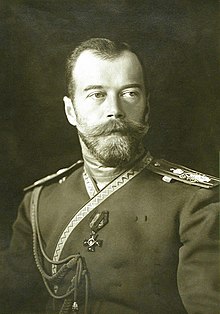

| '''Nicholas II''' | |||

| Nicholas II, also known as Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov, was the final Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland, and ] of Finland. His reign started on 1 November 1894 and ended with his abdication on 15 March 1917. Born on 18 May 1868 at ], Tsarskoye Selo, Russian Empire, he was the eldest son and successor of Aleksandr Aleksandrovich<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Nikitin |first=Aleksandr Aleksandrovich |date=2021-10-29 |title=Legal Basis of Control and Prevention of Crimes by Subaltern Officers in Russian Empire |journal=Law, Economics and Management |pages=176–178 |publisher=Publishing house Sreda |doi= 10.31483/r-99727|doi-access=free |isbn=978-5-907411-75-3}}</ref> (later known as ]) and his wife Maria Fyodorovna (formerly Dagmar of ]). | |||

| ] | |||

| During his rule, Nicholas II supported the economic and political reforms proposed by his prime ministers, Sergei Witte and ]. He favored modernization through foreign loans and strong ties with France, but was reluctant to give significant roles to the new parliament (the Duma).<ref>{{Citation |last=Semyonov |first=Alexander |title= The Real and Live Ethnographic Map of Russia: The Russian Empire in The Mirror of The State Duma |date=2010-01-01 |work=Empire Speaks Out |pages= 191–228 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004175716.i-280.35 |access-date=2024-05-22 |publisher=BRILL |doi= 10.1163/ej.9789004175716.i-280.35 |isbn=978-9-0474-2915-9}}</ref> He signed the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 to counter Germany's influence in the Middle East, ending the ] between Russia and the ]. | |||

| However, his reign was marked by criticism for the government's suppression of political dissent and perceived failures or inaction during events like the ], anti-Jewish pogroms, ], and the violent suppression of the 1905 Russian Revolution. The ], which resulted in the destruction of the Russian Baltic Fleet at the ], further eroded his popularity. By March 1917, public support for Nicholas II had dwindled, leading to his forced abdication and the end of the 304-year rule of the ] in Russia (1613–1917).<ref name="geoffreyswain" /> | |||

| Nicholas II was deeply devoted to his wife, Alexandra, whom he married on 26 November 1894. They had five children: Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Tsesarevich Alexei. The Russian Imperial Romanov family was executed by who were believed to be drunken ] revolutionaries under Yakov Yurovsky, as ordered by the Ural Regional Soviet in Yekaterinburg on the night of 16–17 July 1918. This marked the end of the Russian Empire and Imperial Russia.{{Sfn |Waldron|1997|p={{Page needed|date=May 2024}}}} | |||

| ====State budget==== | |||

| ] | |||

| Russia was in a continuous state of financial crisis. While revenue rose from 9 million rubles in 1724 to 40 million in 1794, expenses grew more rapidly, reaching 49 million in 1794. The budget allocated 46 percent to the military, 20 percent to government economic activities, 12 percent to administration, and nine percent for the Imperial Court in St. Petersburg. The deficit required borrowing, primarily from bankers in ]; five percent of the budget was allocated to debt payments. Paper money was issued to pay for expensive wars, thus causing inflation. As a result of its spending, Russia developed a large and well-equipped army, a very large and complex bureaucracy, and a court that rivaled those of ] and ]. But the government was living far beyond its means, and 18th-century Russia remained "a poor, backward, overwhelmingly agricultural, and illiterate country".<ref>Nicholas Riasanovsky, ''A History of Russia'' (4th ed. 1984), p 284</ref> | |||

| ===First half of the 19th century=== | |||

| ], giving orders during the ] (1812) while wounded]] | |||

| {{Main|History of Russia (1796–1855)}} | |||

| In 1801, over four years after Paul became the emperor of Russia, he was killed in ] in a coup. Paul was succeeded by his 23-year-old son, ]. Russia was in a ] with the French Republic under the leadership of the ]-born ] ]. After he became the ], Napoleon defeated Russia at ] in 1805, ] and ] in 1807. After Alexander was defeated in Friedland, he agreed to negotiate and sued for peace with France; the ] led to the Franco-Russian alliance against the ] and joined the ].{{Sfn|Dowling|2014|p=24}} By 1812, Russia had occupied many territories in Eastern Europe, holding some of ] from ] and ] from the ];{{Sfn|Dowling|2014|p=801}} from Northern Europe, it had gained ] from the ] against a weakened ]; it also gained some territory in the Caucasus. | |||

| Following a dispute with Emperor Alexander I, in 1812, Napoleon launched an ]. It was catastrophic for France, whose army was decimated during the ]. Although Napoleon's ] reached Moscow, the Russians' ] strategy prevented the invaders from living off the country. In the harsh and bitter winter, thousands of French troops were ambushed and killed by peasant ] fighters.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Palmer |first=Alan |author-link=Alan Palmer |title=Napoleon in Russia |date=1967 |publisher=Simon and Schuster}}</ref> Russian troops then pursued Napoleon's troops to the gates of Paris, presiding over the redrawing of the map of Europe at the ] (1815), which ultimately made Alexander the monarch of ].<ref>{{Cite book |first=Leonid Ivan |last=Strakhovsky |title=Alexander I of Russia: the man who defeated Napoleon |date=1970}}</ref> The "]" was proclaimed, linking the monarchist great powers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia. | |||

| ], Russia had burned the city just before Napoleon could reach and occupy it.]] | |||

| Although the Russian Empire played a leading political role in the next century, thanks to its role in defeating Napoleonic France, its retention of serfdom precluded economic progress to any significant degree. As Western European economic growth accelerated during the ], Russia began to lag ever farther behind, creating new weaknesses for the empire seeking to play a role as a great power. Russia's status as a great power concealed the inefficiency of its government, the isolation of its people, and its economic and social backwardness. Following the defeat of Napoleon, Alexander I had been ready to discuss constitutional reforms, but though ], no major changes were attempted.<ref>Baykov, Alexander. "The economic development of Russia." '']'' 7.2 (1954): 137–149.</ref> | |||

| ], which occurred contemporaneously with the ].]] | |||

| The liberal Alexander I was replaced by his younger brother ] (1825–1855), who at the beginning of his reign was confronted with an uprising. The background of this revolt lay in the ], when a number of well-educated Russian officers travelled in Europe in the course of military campaigns, where their exposure to the ] of Western Europe encouraged them to seek change on their return to ]. The result was the ] (December 1825), which was the work of a small circle of liberal nobles and army officers who wanted to install Nicholas' brother ] as a constitutional monarch. The revolt was easily crushed, but it caused Nicholas to turn away from the modernization program begun by Peter the Great and champion the doctrine of ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lincoln |first=W. Bruce |author-link=W. Bruce Lincoln |title=Nicholas I, Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias |date=1978}}</ref> | |||

| In order to repress further revolts, censorship was intensified, including the constant surveillance of schools and universities. Textbooks were strictly regulated by the government. Police spies were planted everywhere. Under Nicholas I, would-be revolutionaries were sent off to Siberia, with hundreds of thousands sent to ] camps.<ref>{{Cite book |first=Anatole Gregory |last=Mazour |title=The first Russian revolution, 1825: the Decembrist movement, its origins, development, and significance |date=1961}}</ref> The retaliation for the revolt made "December Fourteenth" a day long remembered by later revolutionary movements.{{Citation needed|date=May 2024}} | |||

| The question of Russia's direction had been gaining attention ever since Peter the Great's program of modernization. Some favored imitating Western Europe while others were against this and called for a return to the traditions of the past. The latter path was advocated by ], who held the "decadent" West in contempt. The Slavophiles were opponents of bureaucracy, who preferred the ] of the medieval Russian '']'' or ''mir'' over the ] of the West.{{Sfn|Stein|1976}} More extreme social doctrines were elaborated by such Russian radicals on the left, such as ], ], and ]. | |||

| ====Foreign policy (1800–1864)==== | |||

| {{Main|Foreign policy of the Russian Empire}} | |||

| ]'s 1893 painting of the ] ] by the Russian forces under leadership of ] during the ]]] | |||

| ] ] in a scene from the ], by ]]] | |||

| After Russian armies liberated the ] (allied since the 1783 ]) from the ]'s occupation of 1802,{{Citation needed|date=April 2017}} during the ], they clashed with Persia over control and consolidation of Georgia, and also became involved in the ] against the ]. At the conclusion of the war, Persia irrevocably ceded what is now ], eastern Georgia, and most of ] to Russia, under the ].{{Sfn|Dowling|2014|p=728}} Russia attempted to expand to the southwest, at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, using recently acquired Georgia at its base for its Caucasus and Anatolian front. The late 1820s were successful years militarily. Despite losing almost all recently consolidated territories in the first year of the ], Russia managed to favorably bring an end to the war with the ], including the formal acquisition of what are now ], Azerbaijan, and ].{{Sfn|Dowling|2014|p=729}} In the ], Russia invaded northeastern ] and occupied the strategic Ottoman towns of ] and ] (Argiroupoli) and, posing as protector of the ], received extensive support from the region's ]. Following a brief occupation, the Russian imperial army withdrew back into Georgia.<ref>{{Cite book |first=David Marshall |last=Lang |author-link=David Marshall Lang |title=The last years of the Georgian monarchy, 1658–1832 |date=1957}}</ref> | |||

| Russian emperors quelled two uprisings in their newly acquired Polish territories: the ] in 1830 and the ] in 1863. In 1863, the Russian autocracy had given the Polish artisans and ] reason to rebel, by assailing national core values of language, religion, and culture.<ref>{{Cite journal |first=Stephen R. |last=Burant |title=The January Uprising of 1863 in Poland: Sources of Disaffection and the Arenas of Revolt |journal=European History Quarterly |volume=15 |issue=2 |date=1985 |pages=131–156|doi=10.1177/026569148501500201 }}</ref> ], ], and Austria tried to intervene in the crisis but were unable to do so. The Russian press and state ] used the Polish uprising to justify the need for unity in the empire.<ref name="Haynes">{{Cite book |last=Haynes |first=Margaret |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zs7KDwAAQBAJ&dq=russification+failed+finland+poland&pg=PA23 |title=Tsarist and Communist Russia 1855–1964. |date=2017 |publisher=University Press |isbn=978-0-1984-2144-3 |location=Oxford |page=23 |access-date=11 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240227152931/https://books.google.com/books?id=zs7KDwAAQBAJ&dq=russification+failed+finland+poland&pg=PA23 |archive-date=27 February 2024 |url-status=live}}</ref> The semi-autonomous ] of Congress Poland subsequently lost its distinctive political and judicial rights, with ] being imposed on its schools and courts.<ref>{{Cite book |first=Norman |last=Davies |author-link=Norman Davies |title=] |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1981 |volume=2 |pages=315–333, 352-63}}</ref> However, Russification policies in Poland, Finland and among the Germans in the Baltics largely failed and only strengthened political opposition.<ref name="Haynes"/> | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| {{Panorama | |||

| |image=File:Круговая панорама Москвы со Спасской башни Кремля.jpg | |||

| |fullwidth=12569 | |||

| |fullheight=600 | |||

| |caption={{Center|A ] view of ] from the ] in 1819 (hand-drawn lithograph)}} | |||

| |alt=Panorama of Moscow in 1819 (hand-drawn lithograph) | |||

| |height=175 | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Second half of the 19th century=== | |||

| {{Main|History of Russia (1855–1892)}} | |||

| {{Further|Government reforms of Alexander II of Russia|Russia–United Kingdom relations}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] of a Russian naval base at ] during the ]]] | |||

| ] (8 June 1868)]] | |||

| ] in 1873]] | |||

| ] (1877)]] | |||

| In 1854–1855, Russia fought ], ] and the ] in the ], which Russia lost. The war was fought primarily in the ], and to a lesser extent in the Baltic during the related ]. Since playing a major role in the defeat of Napoleon, Russia had been regarded as militarily invincible, but against a coalition of the great powers of Europe, the reverses it suffered on land and sea exposed the weakness of Emperor Nicholas I's regime. | |||

| When Emperor ] ascended the throne in 1855, the desire for reform was widespread. A growing humanitarian movement attacked ] as inefficient. In 1859, there were more than 23 million serfs in usually poor living conditions. Alexander II decided to abolish ] from above, with ample provision for the landowners, rather than wait for it to be abolished from below by revolution.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Radzinsky |first=Edvard |title=Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar |date=2006 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-0-7432-8426-4}}</ref> | |||

| The ], which freed the serfs, was the single most important event in 19th-century Russian history, and the beginning of the end of the landed aristocracy's monopoly on power. The 1860s saw further socioeconomic reforms to clarify the position of the Russian government with regard to property rights.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Baten, Jörg |title=A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. |date=2016 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-1075-0718-0 |page=81}}</ref> Emancipation brought a supply of free labor to the cities, stimulating industry, while the middle class grew in number and influence. However, instead of receiving their lands as a gift, the freed peasants had to pay a special lifetime tax to the government, which in turn paid the landlords a generous price for the land that they had lost. In numerous cases the peasants ended up with relatively small amounts of the least productive land. All the property turned over to the peasants was owned collectively by the ''mir'', the village community, which divided the land among the peasants and supervised the various holdings. Although serfdom was abolished, its abolition was achieved on terms unfavorable to peasants; thus, revolutionary tensions remained. Revolutionaries believed that the newly freed serfs were merely being sold into ] in the onset of the industrial revolution, and that the urban ] had effectively replaced the landowners.<ref>David Moon, ''The abolition of serfdom in Russia 1762–1907'' (Longman, 2001)</ref> | |||

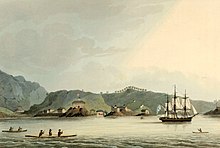

| Seeking more territories, Russia ] Priamurye (]) from the weakened ], which had been occupied fighting against the ]. In 1858, the ] ceded much of the Manchu homeland to the Russian Empire, and in 1860, the ] also ceded the modern ], which provided the land for the establishment of the outpost of the future ].<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Polunov |first1=Alexander Y. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q2qmBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA164 |title=Russia in the Nineteenth Century: Autocracy, Reform, and Social Change, 1814–1914 |last2=Owen |first2=Thomas C. |last3=Zakharova |first3=Larisa G. |publisher=Routledge |date=2015 |isbn=978-1-3174-6049-7 |page=164 |access-date=21 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230121184735/https://books.google.com/books?id=q2qmBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA164 |archive-date=21 January 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> Meanwhile, Russia under ] decided to sell what it saw as the indefensible ] to the ] for 11 million rubles (7.2 million dollars) in 1867 to the American ] government in the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |date=1943-04-01 |title=Russian Opinion on the Cession of Alaska |url=https://doi.org/10.2307/1839639 |journal=The American Historical Review |volume=48 |issue=3 |pages=521 |doi=10.2307/1839639 |issn=0002-8762}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Akinsha |first1=Konstantin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=S8akKpxJqoMC&pg=PA74 |title=The Holy Place: Architecture, Ideology, and History in Russia |last2=Kozlov |first2=Georgi |last3=Hochfleid |first3=Sylvya |publisher=Yale University Press |date=2008 |isbn=978-0-3001-4497-0 |page=74 |access-date=21 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230117183005/https://books.google.com/books?id=S8akKpxJqoMC&pg=PA74 |archive-date=17 January 2023 |url-status=live}}; {{Cite book |last=Borrero |first=Mauricio |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dhm0cGdrTOIC&pg=PA54 |title=Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present |publisher=Infobase Publishing |date=2009 |isbn=978-0-8160-7475-4 |page=54 |access-date=21 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230120173820/https://books.google.com/books?id=dhm0cGdrTOIC&pg=PA54 |archive-date=20 January 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> Initially, many Americans considered this newly gained territory to be a wasteland and useless, and saw the government wasting money, whereupon the transaction was sometimes called "Seward's Folly" through the eponymous ] ] who brokered the deal,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bailey |first=Thomas A. |date=1934-03-01 |title=Why the United States Purchased Alaska |url=https://doi.org/10.2307/3633456 |journal=Pacific Historical Review |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=39–49 |doi=10.2307/3633456 |issn=0030-8684}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Jones |first=Preston |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=W5sXAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA21 |title=The Fires of Patriotism: Alaskans in the Days of the First World War 1910–1920 |publisher=University of Alaska Press |date=2017 |isbn=978-1-6022-3206-8 |pages=21}}</ref> but later, much gold and petroleum were discovered.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Grinev |first=Andrei V. |date=2010-02-18 |title=The Plans for Russian Expansion in the New World and the North Pacific in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries |url=https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/7805 |url-status=live |journal=European Journal of American Studies |language=en |volume=5 |issue=2 |doi=10.4000/ejas.7805 |issn=1991-9336 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220202064920/https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/7805 |archive-date=2 February 2022 |access-date=2 February 2022 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| In the late 1870s, Russia and the Ottoman Empire again clashed in the Balkans. From 1875 to 1877, the Balkan crisis intensified, with rebellions against Ottoman rule by various Slavic nationalities,{{Sfn|Chapman|2002|p=113}} which the Ottoman Turks had dominated since the 15th century. This was seen as a political risk in Russia, which similarly suppressed its Muslims in Central Asia and Caucasia. Russian nationalist opinion became a major domestic factor with its support for liberating Balkan Christians from Ottoman rule and making Bulgaria and ] independent. In early 1877, Russia intervened on behalf of Serbian and Russian volunteer forces,{{Sfn|Chapman|2002|p=114}} leading to the ].{{Sfn|Geoffrey|2011|p=315}} Within one year, Russian troops were nearing ] and the Ottomans surrendered. Russia's nationalist diplomats and generals persuaded Alexander II to force the Ottomans to sign the ] in March 1878, creating an enlarged, independent Bulgaria that stretched into the southwestern Balkans.{{Sfn|Chapman|2002|p=114}} When Britain threatened to declare war over the terms of the treaty, an exhausted Russia backed down. At the ] in July 1878, Russia agreed to the creation of a smaller ] and ], as a vassal state and an autonomous principality inside the Ottoman Empire, respectively.{{Sfn|Geoffrey|2011|p=316}}{{Sfn|Waldron|1997|p=121}} As a result, ] were left with a legacy of bitterness against ] and ] for failing to back Russia. Disappointment at the results of the war stimulated revolutionary tensions, and helped Serbia, ], and ] gain independence from, and strengthen themselves against, the Ottomans.{{Sfn|Seton-Watson|1967|pp=445–460}} | |||

| ] (1877)]] | |||

| Another significant result of the war was the acquisition from the Ottomans of the provinces of ], ], and ] in ], which were transformed into the militarily administered regions of ] and ]. To replace Muslim refugees who had fled across the new frontier into Ottoman territory, the Russian authorities settled large numbers of Christians from ethnically diverse communities in Kars Oblast, particularly ], ], and ], each of whom hoped to achieve protection and advance their own regional ambitions. | |||

| ====Alexander III==== | |||

| In 1881, Alexander II was assassinated by the ], a ] ]. The throne passed to ] (1881–1894), a reactionary who revived the maxim of "Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality" of Nicholas I. A committed Slavophile, Alexander III believed that Russia could be saved from turmoil only by shutting itself off from the subversive influences of Western Europe. During his reign, Russia formed the ], to contain the growing power of Germany; completed the ]; and demanded important territorial and commercial concessions from China. The emperor's most influential adviser was ], tutor to Alexander III and his son Nicholas, and procurator of the Holy Synod from 1880 to 1895. Pobedonostsev taught his imperial pupils to fear freedom of speech and the press, as well as dislike democracy, constitutions, and the parliamentary system. Under Pobedonostsev, revolutionaries were persecuted—by the ], with thousands being exiled to ]—and a policy of ] was carried out throughout the empire.<ref>Charles Lowe, ''Alexander III of Russia'' (1895) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170118111426/https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=n9hBAAAAYAAJ |date=18 January 2017}}; {{Cite book |last=Byrnes |first=Robert F. |title=Pobedonostsev: His Life and Thought |date=1968 |publisher=Indiana University Press}}</ref> | |||

| ====Foreign policy (1864–1907)==== | |||

| Russia had little difficulty expanding to the south, including conquering ],<ref>{{Cite book |first=David |last=Schimmelpenninck Van Der Oye |title=Russian foreign policy, 1815–1917 |pages=554–574}} in {{Harvnb|Lieven|2006}}</ref> until Britain became alarmed when Russia threatened ], with the implicit threat to ]; and decades of diplomatic maneuvering resulted, called the ].{{Sfn|Seton-Watson|1967|pp=441–444, 679–682}} That rivalry between the two empires has been considered to have included far-flung territories such as ] and ]. The maneuvering largely ended with the ] of 1907.<ref name=":42">{{Cite book |last=Andreev |first=A. I. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MqXnOBX4dREC |title=Soviet Russia and Tibet: the debacle of secret diplomacy, 1918-1930s |date=2003 |publisher=Brill |isbn=9-0041-2952-9 |location=Leiden |pages=13–15, 37, 67, 96 |oclc=51330174 |quote=In the days of the Great Game, Mongolia was an object of imperialist encroachment by Russia, as Tibet was for the British. |access-date=22 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230124202721/https://books.google.com/books?id=MqXnOBX4dREC |archive-date=24 January 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Expansion into the vast stretches of Siberia was slow and expensive, but finally became possible with the building of the ], 1890 to 1904. This opened up ]; and Russian interests focused on Mongolia, ], and ]. China was too weak to resist, and was pulled increasingly into the Russian sphere. Russia obtained treaty ports such as ]/]. In 1900, the Russian Empire ] as part of the ]'s intervention against the ]. ] strongly opposed Russian expansion, and defeated Russia in the ] of 1904–1905. Japan took over Korea, and Manchuria remained a contested area.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Port Arthur Revisited |url=https://www.historytoday.com/archive/port-arthur-revisited |volume=52 |issue=1 |date=January 2002 |author-link=Richard Connaughton |first=Richard |last=Connaughton |website=HistoryToday.com}}</ref> | |||

| Meanwhile, ], looking for allies against Germany after 1871, formed a ] in 1894, with large-scale loans to Russia, sales of arms, and warships, as well as diplomatic support. Once Afghanistan was informally partitioned by the ] in 1907, Britain, France, and Russia came increasingly close together in opposition to Germany and Austria-Hungary. The three would later comprise the ] alliance in the ].<ref>{{Cite book |first=Barbara |last=Jelavich |title=St. Petersburg and Moscow: Tsarist and Soviet Foreign Policy, 1814–1974 |date=1974 |oclc=299007 |ol=5911156M |pages=161–279}}</ref> | |||

| ===Early 20th century=== | |||

| {{Main|History of Russia (1892–1917)}} | |||

| ], by ]<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ascher |first=Abraham |title=The Revolution of 1905: A Short History |date=2004 |publisher=Stanford University Press |isbn=978-0-8047-5028-8 |pages=187–210 |chapter=Coup d'État |access-date=19 March 2023 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rNRqfGWR4pIC&pg=PA187 |ol=3681754M}}; {{Cite book |last=Harcave |first=Sidney |title=First blood: the Russian Revolution of 1905 |date=1964 |publisher=Macmillan |chapter=The "Two Russias" |oclc=405923 |ol=5918954M}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] from the Kremlin, 1908]] | |||

| In 1894, Alexander III was succeeded by his son, ], who was committed to retaining the autocracy that his father had left him. Nicholas II proved as an ineffective ruler, and in the end his dynasty was overthrown by the ].<ref>{{Cite book |first=Robert D. |last=Warth |title=Nicholas II: the life and reign of Russia's last monarch |date=1997}}</ref> The ] began to show significant influence in Russia, but the country remained rural and poor. | |||

| Economic conditions steadily improved after 1890, thanks to new crops such as sugar beets, and new access to railway transportation. Total grain production increased, as well as exports, even with rising domestic demand from population growth. As a result, there was a slow improvement in the living standards of Russian peasants in the empire's last two decades before 1914. Recent research into the physical stature of Army recruits shows they were bigger and stronger. There were regional variations, with more poverty in the heavily populated ]; and there were temporary downturns in 1891–93 and 1905–1908.{{Sfn|Lieven|2006|p=391}} | |||

| By the end of the 19th century, the Russian Empire dominated its territorial extent, covering a surface area of 22,800,000 km<sup>2</sup>, making it become the world's third-largest empire. | |||

| On the political right, the reactionary elements of the aristocracy strongly favored the large landholders, who, however, were slowly selling their land to the peasants through the ]. The ] party was a conservative force, with a base of landowners and businessmen. They accepted land reform but insisted that property owners be fully paid. They favored far-reaching reforms, and hoped the landlord class would fade away, while agreeing they should be paid for their land. Liberal elements among industrial capitalists and nobility, who believed in peaceful social reform and a constitutional monarchy, formed the ] or ''Kadets''.{{Sfn|Freeze|2002|pp=234–268}} | |||

| On the left, the ] (SRs) and the Marxist ] wanted to expropriate the land, without payment, but debated whether to distribute the land among the peasants (the ] solution), or to put it into collective local ownership.<ref>{{Cite book |first=Hugh |last=Seton-Watson |title=The Decline of Imperial Russia, 1855–1914 |date=1952 |pages=277–280}}</ref> The Socialist Revolutionaries also differed from the Social Democrats in that the SRs believed a revolution must rely on urban workers, not the peasantry.<ref>{{Cite journal |first=Oliver H. |last=Radkey |title=An Alternative to Bolshevism: The Program of Russian Social Revolutionism |journal=Journal of Modern History |volume=25 |issue=1 |date=1953 |pages=25–39|doi=10.1086/237562 }}</ref> | |||

| In 1903, at the ], in London, the party split into two wings: the gradualist ] and the more radical ]. The Mensheviks believed that the Russian working class was insufficiently developed and that socialism could be achieved only after a period of bourgeois democratic rule. They thus tended to ally themselves with the forces of bourgeois liberalism. The Bolsheviks, under ], supported the idea of forming a small elite of professional revolutionists, subject to strong party discipline, to act as the vanguard of the proletariat, in order to seize power by force.<ref>{{Cite journal |first=Richard |last=Cavendish |title=The Bolshevik-Menshevik split November 16th, 1903 |journal=History Today |volume=53 |issue=11 |date=2003 |pages=64ff}}</ref> | |||

| ] (inside China), during the ] (1904–1905)]] | |||

| Defeat in the ] (1904–1905) was a major blow to the tsarist regime and further increased the potential for unrest. In January 1905, an incident known as "]" occurred when Father ] led an enormous crowd to the ] in ] to present a petition to the emperor. When the procession reached the palace, soldiers opened fire on the crowd, killing hundreds. The Russian masses were so furious over the massacre that a general strike was declared, which demanded a democratic republic. This marked the beginning of the ]. ] (councils of workers) appeared in most cities to direct revolutionary activity. Russia was paralyzed, and the government was desperate.{{Sfn|Ascher|2004|pp=160–186}} | |||

| In October 1905, Nicholas reluctantly issued the ], which conceded the creation of a national ] (legislature) to be called without delay. The right to vote was extended and no law was to become final without confirmation by the Duma. The moderate groups were satisfied, but the socialists rejected the concessions as insufficient and tried to organise new strikes. By the end of 1905, there was disunity among the reformers, and the emperor's position was strengthened, allowing him to roll back some of the concessions with the new ]. | |||

| ===War, revolution, and collapse=== | |||

| {{Main|Dissolution of the Russian Empire}} | |||

| {{Further|Eastern Front (World War I)}} | |||

| {{See also|Eastern Orthodoxy by country}} | |||

| ====Origins of causes==== | |||

| {{Main|Causes of World War I}} | |||

| Russia, along with ] and ], was a member of the ] in antecedent to ]; these three powers were formed up in response to ]'s rival<ref>{{Cite book |last=Garver |first=John W. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xvuuCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA764 |title=China's Quest: The History of the Foreign Relations of the People's Republic of China |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=2015 |isbn=978-0-1908-8435-2 |page=764 |access-date=10 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221228171639/https://books.google.com/books?id=xvuuCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA764 |archive-date=28 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> ], comprising itself, ] and ]. Previously, Saint Petersburg and Paris, along with London, were belligerents in the ]. The relations with Britain were in disquietude from the ] in Central Asia until the 1907 ], when both agreed to settle their differences and joined to oppose the new rising power of Germany.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fromkin |first=David |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OV0i1mJdNSwC&pg=PA208 |title=A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East |publisher=Henry Holt and Company |date=2010 |isbn=978-1-4299-8852-0 |page=208 |access-date=10 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221229193129/https://books.google.com/books?id=OV0i1mJdNSwC&pg=PA208 |archive-date=29 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> Russia and France's relations remained isolated before the 1890s when both sides agreed to ] when peace was threatened.{{Sfn|Lieven|2015|p=82}} France also granted loans for building infrastructure, especially ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fortescue |first=William |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4CMxDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA109 |title=The Third Republic in France, 1870–1940: Conflicts and Continuities |publisher=Routledge |date=2017 |isbn=978-1-3515-4000-1 |page=109 |access-date=10 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221229193135/https://books.google.com/books?id=4CMxDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA109 |archive-date=29 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The relations between Russia and the Triple Alliance, especially Germany and Austria, were like those of the ]. ] were deteriorating,{{Sfn|Waldron|1997|p=132}} and tensions over the ] had reached a breaking point with ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Yorulmaz |first=Naci |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2-eKDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA40 |title=Arming the Sultan: German Arms Trade and Personal Diplomacy in the Ottoman Empire Before World War I |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |date=2014 |isbn=978-0-8577-2518-9 |page=40 |access-date=10 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221229183449/https://books.google.com/books?id=2-eKDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA40 |archive-date=29 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> The 1908 ] had nearly led to war and in 1912–13 relations between Saint Petersburg and Vienna were tense during the ].{{Sfn|Lieven|2015|p=241}} | |||

| The ] of the Austro-Hungarian heir, ], raised Europe's tensions, which led to the confrontation between Austria and Russia.{{Sfn|Lieven|2015|p=2}} ] rejected an ] that demanded an obligation for the heir's death, and Austria-Hungary cut all diplomatic ties and declared war on 28 July 1914. Russia supported Serbia because it was a fellow Slavic state, and two days later, Emperor ] ordered a mobilization to attempt to force Austria-Hungary to back down.{{Sfn|McMeekin|2011|p=88}} | |||

| ====Declaration of War==== | |||

| {{Main|Russian entry into World War I}} | |||

| ], on the balcony of the ], on 2 August 1914.]] | |||

| As a result of ]'s declaration of war on Serbia, Nicholas II ordered the mobilization of 4.9 million men. ], Austria-Hungary's ally, saw the call to arms as a threat; when Russia mustered its troops, Germany affirmed the state of "imminent danger of War",<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2EyJY8uE4WYC&pg=PA180 |title=The Origins of World War I |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=2003 |isbn=978-0-5218-1735-6 |editor-last=Hamilton |editor-first=Richard F. |page=180 |access-date=30 December 2022 |editor-last2=Herwig |editor-first2=Holger |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221227194005/https://books.google.com/books?id=2EyJY8uE4WYC&pg=PA180 |archive-date=27 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> followed by the declaration of war on 1 August 1914.{{Sfn|Lieven|2015|p=338}} The Russians were imbued with patriotic earnestness and ], including the name of the capital, ], which sounded too ] for the sake of words ] and ]; and was renamed Petrograd.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ruthchild |first=Rochelle |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ymzJHyguvigC&pg=PA255 |title=Equality and Revolution |publisher=University of Pittsburgh Press |date=2010 |isbn=978-0-8229-7375-1 |page=255 |access-date=30 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221227194008/https://books.google.com/books?id=ymzJHyguvigC&pg=PA255 |archive-date=27 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The Russian entry into the First World War was followed by ], which both had been allied with Russia since 1892, fearing the rise of Germany as the new power.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Goldman |first=Emily |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AbtHRsAAPIkC&pg=PA40 |title=Power in Uncertain Times: Strategy in the Fog of Peace |publisher=Stanford University Press |date=2011 |isbn=978-0-8047-7433-8 |page=40 |access-date=30 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221227194007/https://books.google.com/books?id=AbtHRsAAPIkC&pg=PA40 |archive-date=27 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> The ] had therefore devised the ], which first eliminated France via nonaligned ] before moving east to attack Russia, whose massive army was much slower to mobilise.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Zabecki |first=David T. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rCWMBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA371 |title=Germany at War: 400 Years of Military History |publisher=ABC-CLIO |date=2014 |isbn=978-1-5988-4981-3 |page=371 |access-date=5 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230104160047/https://books.google.com/books?id=rCWMBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA371 |archive-date=4 January 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ====Theaters of operations==== | |||

| =====German front===== | |||

| {{Main|Russian invasion of East Prussia|Great Retreat (Russian){{!}}Great Retreat|Vistula–Bug offensive}} | |||

| ], a major disaster for Russia]] | |||

| By August 1914, Russia had ] with unexpected speed the German province of ], ending with a humiliating defeat at ], owing to a message sent without wiring and ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=McNally |first=Michael |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YpeEEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA61 |title=Tannenberg 1914: Destruction of the Russian Second Army |publisher=Bloomsbury |date=2022 |isbn=978-1-4728-5020-1 |page=61 |access-date=30 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221226194512/https://books.google.com/books?id=YpeEEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA61 |archive-date=26 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> causing the destruction of the entire ]. Russia suffered a massive defeat at the Masurian Lakes twice, the ] ending with a hundred thousand casualties;{{Sfn|Tucker|2014|p=1048}} and the ] suffering 200,000.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2YqjfHLyyj8C&pg=PA380 |title=World War I: Encyclopedia |publisher=ABC-CLIO |date=2005 |isbn=978-1-8510-9420-2 |editor-last=Tucker |editor-first=Spencer C. |volume=1 |page=380 |access-date=30 December 2022 |editor-last2=Roberts |editor-first2=Priscilla M. |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221226194508/https://books.google.com/books?id=2YqjfHLyyj8C&pg=PA380 |archive-date=26 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> By October, the ] was near ], and the newly-formed ] had retreated from the frontier in East Prussia. ], the Russian commander-in-chief, now had the order to invade ] with his ], ], and ].{{Sfn|Tucker|2019|p=468}} The Ninth Army, led by ], retreated from the frontline in ] and concentrated between the cities of ] and ]. The advance ] on 11 November against the main army's right flank and rear; the ] and Second armies were severely mauled, and the Second army was nearly surrounded in ] on 17 November. | |||

| Exhausted Russian troops began to ] from ], allowing the Germans to capture many cities, including the kingdom's capital ] on 5 August 1915.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sondhaus |first=Lawrence |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9in-DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA114 |title=World War One |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=2020 |isbn=978-1-1084-9619-3 |page=114 |access-date=30 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221227173555/https://books.google.com/books?id=9in-DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA114 |archive-date=27 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> In the same month, the emperor dismissed Grand Duke Nicholas and took personal command;<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Kalic |first1=Sean N. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0YI2DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA180 |title=Russian Revolution of 1917: The Essential Reference Guide |last2=Brown |first2=Gates M. |publisher=ABC-CLIO |date=2017 |isbn=978-1-4408-5093-6 |page=180 |access-date=30 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221228162636/https://books.google.com/books?id=0YI2DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA180 |archive-date=28 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> this was a turning point for the Russian army and the beginning of the worst disaster.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SZHgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA556 |title=500 Great Military Leaders |publisher=ABC-CLIO |date=2014a |isbn=978-1-5988-4758-1 |editor-last=Tucker |editor-first=Spencer C. |page=556 |access-date=30 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221228162637/https://books.google.com/books?id=SZHgBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA556 |archive-date=28 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> The Germans continued ] the front until they were halted in the line from ] to ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Jahn |first=Hubertus |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9Xx499_1GDoC&pg=PA9 |title=Patriotic Culture in Russia During World War I |publisher=Cornell University Press |date=1998 |isbn=978-0-8014-8571-8 |page=9 |access-date=30 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221227194005/https://books.google.com/books?id=9Xx499_1GDoC&pg=PA9 |archive-date=27 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> Russia lost the entire territory of Poland and Lithuania,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Horne |first=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EjZHLXRKjtEC&pg=PA449 |title=A Companion to World War I |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |date=2012 |isbn=978-1-1199-6870-2 |page=449 |access-date=30 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221227173552/https://books.google.com/books?id=EjZHLXRKjtEC&pg=PA449 |archive-date=27 December 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> part of the ] and ], and partly of ] and ] in Ukraine; thereafter the front with Germany was stable until 1917. | |||

| =====Austrian front===== | |||

| {{Main|Battle of Galicia|Gorlice–Tarnów offensive|Brusilov offensive}} | |||

| Austria-Hungary went to war with Russia on 6 August. The Russians started to invade ], held by Austrian ] on 20 August, and annihilated the ] at ], leading to the occupation of ].{{Sfn|Sanborn|2014|p=30}} While the ] was ], the first attempt to capture the fortress failed, but the second attempt seized the redoubt in March 1915.{{Sfn|Sanborn|2014|p=66}} On 2 May, the Russian army was ] by joint Austro-German forces, retreating from the ] to ] line and losing ]. | |||