| Revision as of 21:31, 16 August 2006 edit146.145.70.200 (talk) →The Communist Party and the U.S. peace movement← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:53, 6 January 2025 edit undoVif12vf (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users80,622 edits Restored revision 1267141511 by Discospinster (talk)Tags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{redirect|American Communist Party|the current splinter group of that name|Jackson Hinkle}} | |||

| {{Infobox_American_Political_Party | | |||

| {{Short description|American political party}} | |||

| party_name = Communist Party USA | | |||

| {{Use American English|date=August 2020}} | |||

| party_articletitle = Communist Party USA | | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=May 2024}} | |||

| party_logo = ] | | |||

| {{Self-published|date=May 2023|talk=Self-Published on the Party's Website}} | |||

| chairman = ] | | |||

| {{Infobox political party | |||

| senateleader= ''N/A'' | | |||

| | name = Communist Party of the United States of America | |||

| houseleader= ''N/A'' | | |||

| | logo = CPUSA.svg | |||

| foundation = ] | | |||

| | slogan = "People and Planet Before Profits" | |||

| ideology = ]; ]| | |||

| | flag = ] | |||

| international = formerly ]; today, none | | |||

| | colorcode = {{party color|Communist Party USA}} | |||

| colours = ]| | |||

| | presidium = ]<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cpusa.org/cpusa-organizational-chart/|title=CPUSA Organizational Chart|work=Communist Party USA |date=March 26, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| headquarters = 235 W. 23rd Street<br> ], ] 10011| | |||

| | foundation = {{nowrap|{{start date and age|1919|9|1}}}} | |||

| website = }} | |||

| | founder = ]<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u-o5jqehzvcC&dq=communist+party+usa+founder+charles+ruthenberg&pg=PR24|isbn = 978-0300138009|title = The Soviet World of American Communism|date =2008|publisher = Yale University Press}}</ref><br/>] | |||

| {{Communism}} | |||

| | split = ] | |||

| The '''Communist Party of the United States of America''' ('''CPUSA''') is one of several ] groups in the ]. For approximately the first half of the ], it was the largest and most widely influential ] in the country, and ] in the U.S. labor movement in the interwar years, organizing and leading most major ]s and ] throughout that period. | |||

| | merger = Communist Party of America<br/>] | |||

| | headquarters = 235 W 23rd St, New York, New York 10011, ], ] | |||

| | newspaper = '']''<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://lccn.loc.gov/sn82016135|title=People's World|website=Library of Congress|oclc=09168021 |access-date=January 21, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| | youth_wing = ]<ref group="note">The party voted to dissolve its youth wing in 2015 and voted to re-establish it in 2019. . June 10, 2019.</ref> | |||

| | membership = {{increase}}15,000<ref name=AP2023>{{Cite news |title=Trump wants to keep 'communists' and 'Marxists' out of the US. Here's what the law says |newspaper=] |date=June 28, 2023 |first1=Rebecca |last1=Santana |first2=Ali |last2=Swenson |url=https://apnews.com/article/donald-trump-immigration-marxists-communists-ban-2024-d9a377149926457d1b8b182293d9c86e |quote=Communist Party USA has about 15,000 people on its membership list, said party co-chair Joe Sims. The list is “pruned regularly,” he said, but some of that group may not be active members.}}</ref> | |||

| | membership_year = 2024 | |||

| | ideology = {{ubl|]<ref name="CPUSA Party Constitution">{{cite web |url=http://www.cpusa.org/party_info/cpusa-constitution/ |title=CPUSA Constitution |work=CPUSA Online |date=September 20, 2001 |access-date=October 30, 2017}}</ref>|]<ref name="ReferenceA" />|]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cpusa.org/party_info/socialism-in-the-usa/ |title=Bill of Rights Socialism |work=CPUSA Online |date=May 1, 2016 |access-date=October 30, 2017}}</ref>}} | |||

| | position = ]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Pierard |first1=Richard |year=1998 |title=American Extremists: Militias, Supremacists, Klansmen, Communists, & Others. By John George and Laird Wilcox. Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Press, 1996. 443 pp. $18.95 |journal=Journal of Church and State |volume=40 |issue=4 |pages=912–913 |publisher=Oxford Journals |doi=10.1093/jcs/40.4.912 }}</ref> | |||

| | international = ] (since 1998)<br/>] (until 1943) | |||

| | colors = {{color box|{{party color|Communist Party USA}}}} ] | |||

| | website = {{URL|https://www.cpusa.org/|cpusa.org}} | |||

| | country = United States | |||

| | leader1_name = ]<br>Rossana Cambron | |||

| | leader1_title = Co-chairs | |||

| | seats1_title = ] | |||

| | seats1 = 0 | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Socialism US}}{{communist parties}} | |||

| <!-- Do not place a legislative control section here. Please see the talk page if you have comments. --> | |||

| The CPUSA survived the ], the first ], and many similar attempts at ] throughout the first part of its existence. However, by the ], the combined effects of the second Red Scare, ], the ], and the ] began to break apart the party's internal structure and confidence. Many members who did not wind up in long-term prison for party activity either quietly disappeared from its ranks or adopted more moderate political positions that were at odds with the CPUSA's basic program. All this meant that the CPUSA was, by the end of the decade, effectively eliminated as a force to be reckoned with. | |||

| The '''Communist Party USA''', officially the '''Communist Party of the United States of America''' ('''CPUSA'''),<ref>"The name of this organization shall be the Communist Party of the United States of America." Art. I of the .</ref> is a ] in the ] which was established in 1919 after a split in the ] following the ].<ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite book |url=http://www.cpusa.org/cpusa-constitution/ |title=Constitution of the Communist Party of the United States of America |publisher=Communist Party of the United States of America |year=2001 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140121151252/http://www.cpusa.org/cpusa-constitution/ |archive-date=January 21, 2014}}</ref><ref name="Goldfield-2009">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Goldfield |first=Michael |chapter=Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA) |date=2009 |encyclopedia=The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest |pages=1–9 |editor-last1=Ness |editor-first1=Immanuel |publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Ltd |language=en |doi=10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp0383 |isbn=978-1405198073}}</ref> | |||

| The history of the CPUSA is closely related to the history of the ] and the history of communist parties worldwide. Initially operating underground due to the ], which started during the ], the party was influential in ] in the first half of the 20th century. It also played a prominent role in the history of the labor movement from the 1920s through the 1940s, playing a key role in the founding of the ].<ref name="Goldfield-2009" /> The party was unique among labor activist groups of the time in being outspokenly ] and opposed to ] after sponsoring the defense for the ] in 1931. The party reached the apex of its influence in U.S. politics during the ], playing a prominent role in the political landscape as a militant grassroots network capable of effectively organizing and mobilizing workers and the unemployed in support of cornerstone ] programs, principally ], ], and the ].<ref> Shannon, David A. (1967). "The Rise of the Communist Party USA during the Great Depression". Journal of American History, 54(2), 351–365. </ref><ref> Kann, Kenneth (2014). "Comrades and Critics: The Communist Party's Role in the New Deal Era". American Communist History, 13(2–3), 123–142. </ref><ref> Ottanelli, Fraser M. (1991). "From the Margins to the Mainstream: The Transformation of the Communist Party USA in the 1930s". The Journal of American-East European Relations, 1(2), 185–209. </ref> | |||

| The party has never recovered from this negative turning-point, but it continues to exist as an organization under the leadership of ], who claims the number of registered members is 15,000. The CPUSA is based in ]; its newspaper is the '']'' and its monthly magazine is '']''. Although advocates of a ], the party calls for a ] and ] transition to a ] system in the United States and rejects the use of ] in a U.S. uprising. | |||

| The transformative changes of the New Deal era combined with the U.S. alliance with the ] during ] created an atmosphere in which the CPUSA wielded considerable influence with about 70,000 vetted party members.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Gregory |first1=James |title=Communist Party Membership by Districts 1922–1950 |url=https://depts.washington.edu/moves/CP_map-members.shtml |website=Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium |publisher=University of Washington}}</ref> Under the leadership of ], the party was critically supportive of President ] and branded communism as "20th Century Americanism".<ref>Browder, Earl. (1936). "Communism and 20th Century Americanism." Political Affairs. p.123. In this seminal work, Browder himself brands communism as '20th Century Americanism,' outlining his perspective on the relationship between communism and American national identity.</ref> Envisioning itself as becoming engrained within the established political structure in the post-war era, the party was dissolved in 1944 to become the 'Communist Political Association.'<ref>, Published in The Path to Peace, Progress and Prosperity: Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the Communist Political Association, New York, May 20–22, 1944.</ref> However, as ] hostility ensued, the party was restored but struggled to maintain its influence amidst the prevalence of ] (also known as the Second Red Scare). Its opposition to the ] and the ] failed to gain traction, and its endorsed candidate ] of the ] under-performed in the ]. The party itself imploded following the public ] by ] in 1956, with membership sinking to a few thousand who were increasingly alienated from the rest of the ] for their support of the Soviet Union.<ref name="Goldfield-2009" /> | |||

| In ] the CPUSA was largely eclipsed by the ]. The party did claim to support, and also claimed to have spearheaded, the ], and supported ] and other movement leaders. However, civil rights leaders themselves kept communists and former communists at arm's length for fear of also being branded communist. Meanwhile, both the ] and the ] rejected the CPUSA for what it saw as the party's ] rigidity and for its steadfastly close association with the Soviet Union. | |||

| The CPUSA received significant funding from the Soviet Union and crafted its public positions to match those of Moscow.<ref>Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes, and Kyrill M. Anderson, ''The Soviet World of American Communism'', Yale University Press (1998); {{ISBN|0300071507}}; p. 148.</ref> The CPUSA also used a covert apparatus to assist the Soviets with their ] and utilized a network of ] to shape public opinion.<ref>Harvey Klehr, John Earl Haynes and Kyrill M. Anderson, ''The Soviet World of American Communism'', Yale University Press (1998); {{ISBN|0300071507}}; p. 74.</ref> The CPUSA opposed '']'' and '']'' in the Soviet Union. As a result, major funding from the ] ended in 1991.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Klehr|first=Harvey|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hpsuDwAAQBAJ&dq=cpusa+glasnost&pg=PT200|title=The Communist Experience in America: A Political and Social History|date= 2017|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1351484749|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In the late ]s the party became estranged from the leadership of ] and criticized his policy of ], leading to the ] cutting off its support of the CPUSA in ]. The CPUSA's ] convention was consumed by a debate on the future orientation of the party following the collapse of the ]. One faction urged the leadership to reject ] and take the party in a ] direction, but the party majority reasserted its classic line. Unable to influence the CPUSA, the group soon left and established itself as the ]. | |||

| == Modern membership == | |||

| In in ], CPUSA correspondents Marilyn Bechtel and Debbie Bell said of their trip to the ]: "...e came away with a new respect for the thoughtfulness, thoroughness, energy and optimism with which the ] and the Chinese people are going about the complex, long-term process of building socialism in a vast developing country, which is of necessity part of an increasingly globalized economy." | |||

| In 2011, CPUSA claimed 2,000 members.<ref>{{Cite web |work=] |date=May 22, 2011 |title=Workers of the World, Please See Our Web Site |first1=Joseph |last1=Berger |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/23/nyregion/leftist-parties-in-new-york-have-new-appeal.html |quote=All three have greatly shrunk from their heydays. The Socialist Party has about 1,000 members nationally. The Communists claim 2,000. The Democratic Socialists, which for many years included luminaries like Michael Harrington and Irving Howe, have about 6,000.}}</ref> In 2017 and 2018, CPUSA claimed 5,000 members.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Gómez |first1=Sergio |title=Communist Party membership numbers climbing in the Trump era |date=April 19, 2017 |newspaper=] |publisher=Communist Party USA |url=https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/communist-party-membership-numbers-climbing-in-the-trump-era/ |quote=Of the country’s 300 million inhabitants, the organization currently has some 5,000 members nationwide.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |author=Lifang |title=Interview: U.S. Communist Party leader says Marxism "vibrant, philosophical" outlook |date=April 15, 2018 |publisher=] |url=http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-04/15/c_137112760.htm |quote=Founded in 1919, the CPUSA has some 5,000 members spread across the country. The party has been active in a range of political and social movements from the labor workers' rights to the environmental protection and peace issues, according to Bachtell.}}</ref> In 2019, former Party member Daniel Rosenberg claimed that "nearly half" of new joiners since 2000 had "paid no dues" and merely signed up for the mailing list.<ref>{{Cite journal |first=Daniel |last=Rosenberg |date=April 22, 2019 |title=From Crisis to Split: The Communist Party USA, 1989–1991 |journal=American Communist History |volume=18 |issue=1–2 |pages=1–55 |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14743892.2019.1599627 |doi=10.1080/14743892.2019.1599627 |quote=The CPUSA rented out most of the floors in its Manhattan headquarters to private companies, drawing valued income. Party clubs assumed increasingly virtual form. Facebook, Twitter, and website outreach seemingly bore fruit, producing online adherents. The Party carefully charted “likes” and “shares.” Nearly half the online joiners paid no dues. Most “likes” came from outside the United States.}}</ref>{{rp|54}} In 2023, CPUSA claimed 15,000 members.<ref name=AP2023>{{Cite news |title=Trump wants to keep 'communists' and 'Marxists' out of the US. Here's what the law says |newspaper=] |date=June 28, 2023 |first1=Rebecca |last1=Santana |first2=Ali |last2=Swenson |url=https://apnews.com/article/donald-trump-immigration-marxists-communists-ban-2024-d9a377149926457d1b8b182293d9c86e |quote=Communist Party USA has about 15,000 people on its membership list, said party co-chair Joe Sims. The list is “pruned regularly,” he said, but some of that group may not be active members.}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| ==The CPUSA Constitution and Program== | |||

| {{main|History of the Communist Party USA}} | |||

| According to its ] constitution , the party operates on the principle of ], and its highest authority is its quadrennial National Convention. Article VI, Section 3 of that constitution lays out certain positions as non-negotiable: "struggle for the unity of the working class, against all forms of national oppression, national chauvinism, discrimination and segregation, against all racist ideologies and practices… against all manifestations of male supremacy and discrimination against women… against homophobia and all manifestations of discrimination against ]s, ]s, ] and ] people…" | |||

| ] | |||

| Among the points in the party's "Immediate Program" are a $12/hour ]; ] programs such as universal ] for all workers, universal ], and opposition to ] of ]; economic measures such as increased taxes on "the rich and corporations," strong regulation" of the financial industry, "regulation and public ownership of utilities", and increased federal aid to cities and states; opposition to the ] and other military interventions; opposition to ] treaties such as ]; ] and a reduced military budget; various ] provisions; ] including public financing of campaigns; and ] reform, including ]. | |||

| During the first half of the 20th century, the Communist Party was influential in various struggles. Historian ] concludes that decades of recent scholarship<ref group="note">She mentions James Barrett, Maurice Isserman, Robin D. G. Kelley, Randi Storch and Kate Weigand.</ref> offer "a more nuanced portrayal of the party as both a ] sect tied to a vicious regime and the most dynamic organization within the ] during the 1930s and '40s."<ref>Ellen Schrecker, "Soviet Espionage in America: An Oft-Told tale", ''Reviews in American History'', Volume 38, Number 2, June 2010 p. 359. Schrecker goes on to explore why the Left dared to spy.</ref> It was also the first political party in the United States to be "fully"{{clarification needed|date=September 2023}} racially integrated.<ref>{{cite news |last=Rose |first=Steve |date=January 24, 2016 |title=Racial harmony in a Marxist utopia: how the Soviet Union capitalised on US discrimination |url=https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/shortcuts/2016/jan/24/racial-harmony-in-a-marxist-utopia-how-the-soviet-union-capitalised-on-us-discrimination-in-pictures |work=The Guardian |access-date=March 25, 2019 }}</ref> | |||

| By August 1919, only months after its founding, the Communist Party claimed to have 50,000 to 60,000 members. Its members also included ] and other ]. At the time, the older and more moderate ], suffering from criminal prosecutions for its antiwar stance during World War I, had declined to 40,000 members. The sections of the Communist Party's ] (IWO) organized for communism around linguistic and ethnic lines, providing ] and tailoring cultural activities to an IWO membership that peaked at 200,000 at its height.<ref name="heyday">{{cite book |last=Klehr |first=Harvey |author-link=Harvey Klehr |title=The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade |url=https://archive.org/details/heydayofamerican00kleh |url-access=registration |publisher=Basic Books |year=1984 |pages=–5 (number of members)|isbn=978-0465029457 }}</ref> | |||

| The CPUSA recognizes the right of independence-seeking groups, many of whom have been led by Communist and communist-oriented partisans, to defend themselves from ], but rejects the use of violence in any ] uprising. The CPUSA argues that most violence throughout modern history is the result of capitalist ]es violently trying to stop social change. ] | |||

| During the ], some Americans were attracted by the visible activism of Communists on behalf of a wide range of social and economic causes, including the rights of African Americans, ].<ref>] and ], '']'', (New York:], 1978), {{ISBN|0394726979}}, </ref> The Communist Party played a significant role in the resurgence of organized labor in the 1930s.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hedges |first=Chris |year=2018 |title=America: The Farewell Tour |publisher=] |page=109 |isbn=978-1501152672 |author-link=Chris Hedges|quote=The breakdown of capitalism saw a short-lived revival of organized labor during the 1930s, often led by the Communist Party.}}</ref> Others, alarmed by the rise of the ] in Spain and the ] in Germany, admired the Soviet Union's early and staunch opposition to ]. Party membership swelled from 7,500 at the start of the decade to 55,000 by its end.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/fifties/essays/anti-communism-1950s |title=Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |website=gilderlehrman.org|date=August 15, 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|While some governments run by people calling themselves Communists have been responsible for horrible acts of violence and repression, notably the ] regime in ], much if not most of the violence often blamed on revolutionary governments and parties is actually the responsibility of the conservative, reactionary, capitalist governments and parties. ... Many revolutions have been relatively peaceful, including the ] and the ] of ]. The bloodshed comes when those formerly in power initiate a civil war, or foreign armies invade, trying to reestablish capitalist, feudal, or colonial power. …While we think that an objective, detailed analysis of most situations over the last century would conclude that capitalist and reactionary governments and parties are responsible for most of the violence, it is true that Communists have engaged in armed struggle, are not ], and that some who called themselves Communists have engaged in repressive tactics.}} | |||

| Party members also rallied to the defense of the ] during this period after a nationalist military uprising moved to overthrow it, resulting in the ] (1936–1939).<ref name="Crain-2016">{{cite news |url=https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/04/18/the-americans-soldiers-of-the-spanish-civil-war |title=The American Soldiers of the Spanish Civil War |last=Crain |first=Caleb |magazine=The New Yorker |date=April 11, 2016 |access-date=November 27, 2019 |language=en |issn=0028-792X}}</ref> The ], along with ] throughout the world, raised funds for medical relief while many of its members made their way to Spain with the aid of the party to join the ], one of the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://spartacus-educational.com/SPrussia.htm |title=Soviet Union and the Spanish Civil War |website=Spartacus Educational |access-date=November 27, 2019}}</ref><ref name="Crain-2016" /> | |||

| ==History of the Communist Party USA== | |||

| ===Formation and early history (1919-1921)=== | |||

| In January, ], ] invited the left wing of the ] to join the ] (Comintern). During the spring of 1919 the Left Wing Caucus of the Socialist Party, buoyed by a large influx of new members from countries involved in the ], prepared to wrest control from the smaller controlling faction of moderate socialists. A referendum to join the Comintern passed with 90% support but the incumbent leadership suppressed the results. Elections for the party's National Executive Committee resulted in 12 leftists being elected out of a total of 15. Calls were made to expel moderates from the party. The moderate incumbents struck back by expelling several state organizations, half a dozen ], and many locals, in all two thirds of the membership. | |||

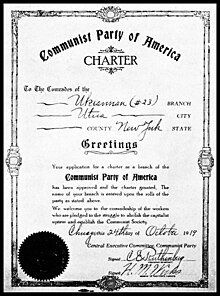

| ] (original scan)]] | |||

| The Socialist Party then called an emergency convention to be held in ] on ], ]. The party's Left Wing Caucus made plans at a June conference of its own to regain control of the party by sending delegations from the sections of the party that had been expelled to the convention to demand that they be seated. However, the language federations, eventually joined by ] and ], turned away from that effort and formed their own party, the Communist Party of America, at a separate convention in ] on ], ]. | |||

| The Communist Party was adamantly opposed to fascism during the ] period. Although membership in the party rose to about 66,000 by 1939,<ref> in , Library of Congress, January 4, 1996. Retrieved August 29, 2006.</ref><ref name="Crain-2016" /> nearly 20,000 members left the party by 1943.<ref name="Crain-2016" /> While general secretary ] at first attacked Germany for its September 1, 1939 ], on September 11 the Communist Party received a communique from Moscow denouncing the Polish government.<ref name="ryan162">{{cite book | vauthors=Ryan JG | date= 1997 | title=Earl Browder: the failure of American communism | publisher=University of Alabama Press | url=http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/39933 | isbn=978-0-585-28017-2 |page =162}}</ref> Between September 14–16, party leaders bickered about the direction to take.<ref name="ryan162"/> | |||

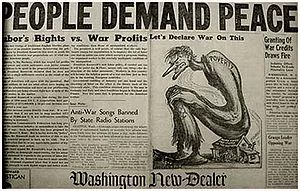

| On September 17, the ] by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, followed by coordination with German forces in Poland.<ref name="stalinswars43">{{cite book |last=Roberts |first=Geoffrey |title=Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953 |publisher=Yale University Press |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-300-11204-7 |page=44}}</ref><ref name="sanford">{{cite book|authorlink=George Sanford (scholar)|last=Sanford|first=George|year=2005|title=Katyn and the Soviet Massacre of 1940: Truth, Justice And Memory|location=London, New York|publisher=]|isbn=0-415-33873-5}}</ref> The Communist Party then turned the focus of its public activities from anti-fascism to advocating peace, opposing military preparations. The party criticized British Prime Minister ] and French leader ], but it did not at first attack President Roosevelt, reasoning that this could devastate American Communism, blaming instead Roosevelt's advisors.<ref name="ryan164">{{cite book | vauthors=Ryan JG | date= 1997 | title=Earl Browder: the failure of American communism | publisher=University of Alabama Press | url=http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/39933 | isbn=978-0-585-28017-2 |pages = 164–165}}</ref> The party spread the slogans "]" and "Hands Off," set up a "perpetual peace vigil" across the street from the ], and announced that Roosevelt was the head of the "war party of the American bourgeoisie."<ref name="ryan168">{{cite book |url=http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/39933 |title=Earl Browder: the failure of American communism |vauthors=Ryan JG |date=1997 |publisher=University of Alabama Press |isbn=978-0-585-28017-2 |page=168}}</ref> The party was active in the ] ].<ref>Selig Adler (1957). ''The isolationist impulse: its twentieth-century reaction''. pp. 269–270, 274.{{ISBN|9780837178226}}</ref> In October and November, after the ] and ], the Communist Party considered Russian security sufficient justification to support the actions.<ref name="ryan166">{{cite book |url=http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/39933 |title=Earl Browder: the failure of American communism |vauthors=Ryan JG |date=1997 |publisher=University of Alabama Press |isbn=978-0-585-28017-2 |page=166}}</ref> The ] and its leader ] demanded that Browder change the party's support for Roosevelt.<ref name="ryan166" /> On October 23, the party began attacking Roosevelt.<ref name="ryan168" /> The party changed this policy again after Hitler broke the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact by ] on June 22, 1941. | |||

| Meanwhile plans led by ] and ] to crash the Socialist Party convention went ahead. Tipped off, the incumbents called the police, who obligingly expelled the leftists from the hall. The remaining leftist delegates walked out and, meeting with the expelled delegates, formed the ] on ], ]. | |||

| In August 1940, after NKVD agent ] killed Trotsky with an ], Browder perpetuated Moscow's line that the killer, who had been dating one of Trotsky's secretaries, was a disillusioned follower.<ref name="ryan189">{{cite book |url=http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/39933 |title=Earl Browder: the failure of American communism |vauthors=Ryan JG |date=1997 |publisher=University of Alabama Press |isbn=978-0-585-28017-2 |page=189}}</ref> | |||

| The Comintern was not happy with two Communist Parties and in January, 1920 dispatched an order that the two parties, which consisted of about 12,000 members, merge under the name ] and to follow the party line established in Moscow. Part of the Communist Party of America under the leadership of Charles Ruthenberg and ] did this but a ] under the leadership of ] and ] continued to operate independently as the Communist Party of America. A more strongly worded directive from the Comintern eventually did the trick and the parties were merged in May, 1921. Only ten percent of the members of the newly formed party were native ]. Many of the members came from the ranks of the ]. | |||

| The Communist Party's early labor and organizing successes did not last long. As the decades progressed, the combined effects of ] (also known as the Second Red Scare) and ]'s 1956 "]" in which he denounced the previous decades of ]'s rule and the adversities of the continuing ] mentality, steadily weakened the party's internal structure and confidence. Party membership in the ] and its close adherence to the political positions of the Soviet Union gave most Americans the impression that the party was not only a threatening, subversive domestic entity, but that it was also a foreign agent that espoused an ideology which was fundamentally alien and threatening to the American way of life. Internal and external crises swirled together, to the point when members who did not end up in prison for party activities either tended to disappear quietly from its ranks, or they tended to adopt more moderate political positions which were at odds with the ]. By 1957, membership had dwindled to less than 10,000, of whom some 1,500 were informants for the ].<ref>Gentry, Kurt, ''J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets''. W. W. Norton & Company 1991. P. 442. {{ISBN|0393024040}}.</ref> The party was also banned by the ], although it was never really enforced and Congress later repealed most provisions of the act, also with some declared unconstitutional via the court system.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1071/communist-control-act-of-1954 |title=Communist Control Act of 1954 |last=Click |first=Kane Madison |website=www.mtsu.edu |language=en |access-date=November 27, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| ===The Red Scare and the underground party (1919-1923)=== | |||

| From its inception, the Communist Party USA came under attack from state and federal governments and later the ]. In late 1919 Attorney General ], acting under the ], began arresting thousands of party members, particularly the foreign-born, whom the government deported. The Communist Party was forced underground and went through various name changes to evade the authorities. | |||

| The party attempted to recover with its opposition to the ] during the ] in the 1960s, but its continued uncritical support for an increasingly stultified and militaristic Soviet Union further alienated it from the rest of the left-wing in the United States, which saw this supportive role as outdated and even dangerous. At the same time, the party's aging membership demographics distanced it from the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.lexisnexis.com/documents/academic/upa_cis/10834_CPUSAFBIDDELib.pdf |title=The Communist Party USA and Radical Organizations, 1953–1960 |last=Naison |first=Mark }}</ref> | |||

| The party apparatus was to a great extent underground. It reemerged in 1923 with a small legal above ground element, the ] of America. As the ] and deportations of the early 1920s ebbed, the party became bolder and more open. An element of the party, however, remained permanently underground. It was through this underground party, often commanded by a Soviet official operating as an illegal in the ], that Soviet intelligence was able to co-opt CPUSA members. | |||

| With the rise of ] and his effort to radically alter the Soviet economic and political system from the mid-1980s, the Communist Party finally became estranged from the leadership of the Soviet Union itself. In 1989, the Soviet Communist Party cut off major funding to the Communist Party USA due to its opposition to '']'' and '']''. With the ] in 1991, the party held its convention and attempted to resolve the issue of whether the party should reject ]. The majority reasserted the party's now purely ] outlook, prompting ] which urged ] to exit the now reduced party. The party has since adopted Marxism–Leninism within its program.<ref name="ReferenceA" /> In 2014, the new draft of the party constitution declared: "We apply the ] developed by Marx, Engels, Lenin and others in the context of our American history, culture, and traditions."<ref>."</ref> | |||

| During this time Jews whose backgrounds derived from Eastern Europe played a very prominent and disproportionate role in the CPUSA.<ref name="(Klehr 1978, p. 37ff).">Klehr, Harvey. ''<sup></sup> Communist cadre: The social background of the American Communist party elite. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.</ref> A majority of the members of the Socialist Party were immigrants and that an 'overwhelming' percentage of the CPUSA consisted of recent immigrants, a substantial percentage of whom were Jews. <ref name="(Glazer 1961, p. 38 p. 40).">Glazer, Nathan ''<sup></sup>The Social Basis of American Communism.</ref> Fear of communist subversion and renewed isolationism in the United States arouse the immigration debates of the 1920s, which led to the restrictive ]. ] and ] literature become widespread (e.g., ]'s ]) in the same period. | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Early factional struggles (1923-1929)=== | |||

| The Communist Party is based in New York City. From 1922 to 1988, it published '']'', a daily newspaper written in ].<ref>{{cite news |title=Two Worlds of a Soviet Spy – The Astonishing Life Story of Joseph Katz |url=https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/the-two-worlds-of-a-soviet-spy/ |access-date=June 4, 2017 |work=Commentary Magazine |publisher=Commentary, Inc. |date=February 15, 2017 |first1=Harvey |last1=Klehr |first2=John Earl |last2=Haynes |first3=David |last3=Gurvitz}}</ref><ref name="Henry02">Henry Felix Srebrnik, ''Dreams of Nationhood: American Jewish Communists and the Soviet Birobidzhan Project, 1924–1951.'' Brighton, MA: Academic Studies Press, 2010; p. 2.</ref> For decades, its West Coast newspaper was the '']'' and its East Coast newspaper was '']''.<ref>, 354 U.S. 298 (1957)</ref> The two newspapers merged in 1986 into the ''People's Weekly World''. The ''People's Weekly World'' has since become an online only publication called ''People's World''. It has since ceased being an official Communist Party publication as the party does not fund its publication.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://peoplesworld.org/about-the-peoples-world/|title=About People's World|newspaper=People's World |date=August 25, 2009}}</ref> The party's former theoretical journal '']'' is now also published exclusively online, but the party still maintains ] as its publishing house. In June 2014, the party held its ] in Chicago.<ref>{{cite web |title=Opening of the Communist Party's 30th national convention |url=http://peoplesworld.org/opening-of-the-communist-party-s-30th-national-convention/ |website=People's World |date=June 13, 2014 |access-date=June 16, 2014}}</ref> The party's celebrated the party's 100th year since its founding. | |||

| Now that the aboveground element, or "open party" as it was known, was legal the communists decided that their central task was to develop roots within the working class. This move away from hopes of revolution in the near future to a more nuanced approach was accelerated by the decisions of the Fifth World Congress of the Comintern held in ], which decided that the period between 1917 and 1924 had been one of revolutionary upsurge, but that the new period was marked by the stabilization of capitalism and that revolutionary attempts in the near future were to be spurned. The American communists embarked then on the arduous work of locating and winning allies. | |||

| The party announced on April 7, 2021, that it intended to run candidates in elections again, after a hiatus of over thirty years.<ref>{{cite web |title=It's time to run candidates: A call for discussion and action |date=April 9, 2021|url=https://www.cpusa.org/article/its-time-to-run-candidates-a-call-for-discussion-and-action/}}</ref> Steven Estrada, who ran for city council in ], was one of the first candidates to run as an open member of the CPUSA again (although Long Beach local elections are officially non-partisan).<ref>{{Cite web|title=Steven Estrada for District One|url=https://www.stevenestrada.org/|access-date=April 26, 2021|website=Steven Estrada for District One|language=en-US|archive-date=April 26, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210426133315/https://www.stevenestrada.org/|url-status=dead}}</ref> Estrada received 8.5% of the vote.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Steven Estrada – Ballotpedia|url= https://ballotpedia.org/Steven_Estrada |access-date=October 21, 2023|language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| That work was, however, complicated by factional struggles within the CPUSA. The party quickly developed a number of more or less fixed factional groupings within its leadership: a faction around the party's Chairman Charles Ruthenberg, which was largely organized by his supporter ], and the Foster-Cannon caucus, headed by ], who headed the Party's ], and ], who led the ] organization. The first faction drew many of its members from the party's foreign language federations while the latter found more support among 'native' workers. | |||

| == Beliefs == | |||

| Foster, who had been deeply involved in the steel strike of 1919 and had been a long-time ] and a ], had strong bonds with the progressive leaders of the Chicago Federation of Labor and, through them, with the Progressive Party and nascent farmer-labor parties. Under pressure from the Comintern, however, the party broke off relations with both groups in ]. | |||

| === Constitution program === | |||

| According to the constitution of the party adopted at the 30th National Convention in 2014, the Communist Party operates on the principle of ],<ref name="2014constitution" /> its highest authority being the quadrennial National Convention. Article VI, Section 3 of the 2001 Constitution laid out certain positions as non-negotiable:<ref name="2001constitution">{{Cite web|url=http://www.cpusa.org/cpusa-constitution/|title=CPUSA Constitution|date=September 20, 2001|website=Communist Party USA|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111117135345/http://www.cpusa.org/cpusa-constitution/|archive-date=November 17, 2011|access-date=February 8, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>truggle for the unity of the working class, against all forms of national oppression, national chauvinism, discrimination and segregation, against all racist ideologies and practices,{{nbsp}}... against all manifestations of male supremacy and discrimination against women,{{nbsp}}... against homophobia and all manifestations of discrimination against gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people.</blockquote> | |||

| In ] Comintern representative ] ordered the majority Foster faction to surrender control to Ruthenberg's faction; Foster complied. The factional infighting within the CPUSA did not end, however; the communist leadership of the New York locals of the ] lost the ] strike of cloakmakers in ] in large part because of intra-party factional rivalries. | |||

| Among the points in the party's "Immediate Program" are a $15/hour ] for all workers, national universal health care, and opposition to ] of ]. Economic measures such as increased taxes on "the rich and corporations, strong regulation of the financial industry, regulation and public ownership of utilities," and increased federal aid to cities and states are also included in the Immediate Program, as are opposition to the ] and other military interventions; opposition to ] treaties such as the ] (NAFTA); ] and a reduced military budget; various ] provisions; ] including public financing of campaigns; and ] reform, including ].<ref name="Immediate Program" /> | |||

| Ruthenberg died in 1927 and his ally, ], succeeded him as party secretary. Cannon attended the ] in ], hoping to use his connections with leading circles within it to regain the advantage against the Lovestone faction. However he and ] of the ] were accidentally given a copy of ]'s "Critique of the Draft Program of the Comintern" that they were instructed to read and return. Persuaded by its contents, they came to an agreement to return to America and campaign for the document's positions. A copy of the document was then smuggled out of the country in a child's toy. | |||

| === Bill of rights socialism === | |||

| Back in America, ] and his close associates in the ILD such as ] and ], dubbed the "three generals without an army", began to organize support for Trotsky's theses. However, as this attempt to develop a ] came to light, they and their supporters were expelled. Cannon and his followers organized the ] as a section of Trotsky's ]. | |||

| {{main|Bill of Rights socialism}} | |||

| The Communist Party emphasizes a vision of socialism as an extension of American democracy. Seeking to "build socialism in the United States based on the revolutionary traditions and struggles" of American history, the party promotes a conception of "Bill of Rights Socialism" that will "guarantee all the freedoms we have won over centuries of struggle and also extend the ] to include freedom from unemployment" as well as freedom "from poverty, from illiteracy, and from discrimination and oppression."<ref name="28th Party Program">.</ref> | |||

| Reiterating the idea of property rights in socialist society as it is outlined in ] and ]'s '']'' (1848),<ref>See Karl Marx, ''The Communist Manifesto'', Chapter 2.</ref> the Communist Party emphasizes: | |||

| At the same Congress, Lovestone had impressed the leadership of the ] as a strong supporter of ] the general secretary of the Comintern. This was to have devastating consequences for Lovestone when, in 1929, Bukharin was on the losing end of a struggle with Stalin and was purged from his position on the ] and removed as head of the Comintern. | |||

| <blockquote>Many myths have been propagated about socialism. Contrary to right-wing claims, socialism would not take away the personal private property of workers, only the private ownership of major industries, financial institutions, and other large corporations, and the excessive luxuries of the super-rich.<ref name="28th Party Program" /></blockquote> | |||

| In a reversal of the events of 1925, a Comintern delegation sent to the United States demanded that Lovestone resign as party secretary in favor of his archrival Foster, despite the fact that Lovestone enjoyed the support of the vast majority of the American party's membership. Lovestone traveled to the Soviet Union and appealed directly to the Comintern. Stalin informed Lovestone that he "had a majority because the American Communist Party until now regarded you as the determined supporters of the Communist International. And it was only because the Party regarded you as friends of the Comintern that you had a majority in the ranks of the American Communist Party". | |||

| Rather than making all wages entirely equal, the Communist Party holds that building socialism would entail "eliminating private wealth from stock speculation, from private ownership of large corporations, from the export of capital and jobs, and from the exploitation of large numbers of workers."<ref name="28th Party Program" /> | |||

| When Lovestone returned to the United States, he and his ally ] were purged despite holding the leadership of the party. Ostensibly, this was not due to Lovestone's insubordination in challenging a decision by Stalin but for his support for ], the thesis that socialism could be achieved peacefully in the USA.''' | |||

| Lovestone and Gitlow formed their own group called the ''Communist Party (Opposition)'', a section of the pro-Bukharin ], which was initially larger than the ]s but failed to survive past ]. Lovestone had initially called his faction the ''Communist Party (Majority Group)'' in the expectation that the majority of the CPUSA's members would join him, but only a few hundred people joined his new organization. | |||

| === Living standards === | |||

| ''See also External link to .'' and ] | |||

| Among the primary concerns of the Communist Party are the problems of ], ] and ], which the party considers the natural result of the profit-driven incentives of the capitalist economy: | |||

| <blockquote>Millions of workers are unemployed, underemployed, or insecure in their jobs, even during economic upswings and periods of 'recovery' from recessions. Most workers experience long years of stagnant and declining real wages, while health and education costs soar. Many workers are forced to work second and third jobs to make ends meet. Most workers now average four different occupations during their lifetime, many involuntarily moved from job to job and career to career. Often, retirement-age workers are forced to continue working just to provide health care for themselves and their families. Millions of people continuously live below the poverty level; many suffer homelessness and hunger. Public and private programs to alleviate poverty and hunger do not reach everyone, and are inadequate even for those they do reach. With capitalist globalization, jobs move from place to place as capitalists export factories and even entire industries to other countries in a relentless search for the lowest wages.<ref name="28th Party Program" /></blockquote> | |||

| ===The Third Period (1928-1935)=== | |||

| The upheavals within the CPUSA in 1928 were an echo of a much more significant change: Stalin's decision to break off any form of collaboration with western socialist parties, which were now condemned as "social fascists", had particularly severe consequences in ], where the ] not only refused to work in alliance with the ], but attacked it and its members. In 1928 there were about twenty-four thousand members. By 1932 the total had fallen to six thousand members. | |||

| The Communist Party believes that "class struggle starts with the fight for wages, hours, benefits, working conditions, job security, and jobs. But it also includes an endless variety of other forms for fighting specific battles: resisting speed-up, picketing, contract negotiations, strikes, demonstrations, lobbying for pro-labor legislation, elections, and even general strikes".<ref name="28th Party Program" /> The Communist Party's national programs considers workers who struggle "against the capitalist class or any part of it on any issue with the aim of improving or defending their lives" part of the class struggle.<ref name="28th Party Program" /> | |||

| Opposing Stalin's Third Period policies in the Communist Party USA was ]. This resulted in his expulsion. He then founded the ] with ] and ], and started publishing '']''. It declared itself to be an external faction of the Communist Party until, as the Trotskyists saw it, Stalin's policies in Germany helped Hitler take power. At that point they started working towards the founding of a new international, the ]. | |||

| === Imperialism and war === | |||

| In the United States the principal impact of the Third Period was to end the CPUSA's efforts to organize within the AFL through the TUEL and to turn its efforts into organizing ] through the ]. Foster went along with this change, even though it contradicted the policies he had fought for previously. He did not, however, remain head of the CPUSA: in ] one of his subordinates, ], replaced him. | |||

| The Communist Party maintains that developments within the ]—as reflected in the rise of ] and other groups associated with ]—have developed in tandem with the interests of large-scale capital such as the ]s. The state thereby becomes thrust into a proxy role that is essentially inclined to help facilitate "control by one section of the capitalist class over all others and over the whole of society".<ref name="28th Party Program" /> | |||

| Accordingly, the Communist Party holds that right-wing policymakers such as the neoconservatives, steering the state away from working-class interests on behalf of a disproportionately powerful capitalist class, have "demonized foreign opponents of the U.S., covertly funded the ], and gave weapons to the ] dictatorship in Iraq. They picked small countries to invade, including ] and ], testing new military equipment and strategy, and breaking down resistance at home and abroad to U.S. military invasion as a policy option".<ref name="28th Party Program" /> | |||

| By 1930 the party adopted the title of Communist Party of the USA, with the slogan of "the united front from below". The Party devoted much of its energy in the ] to organizing the unemployed, attempting to found "red" unions, championing the rights of African Americans and fighting evictions of farmers and the working poor. At the same time, the Party attempted to weave its sectarian revolutionary politics into its day-to-day defense of workers, usually with only limited success. They recruited more disaffected members of the Socialist Party and an organization of ] socialists called the ], some of whose members, particularly ], would later play important roles in communist work among blacks. | |||

| From its ideological framework, the Communist Party understands ]: the state, working on behalf of the few who wield disproportionate power, assumes the role of proffering "phony rationalizations" for economically driven imperial ambition as a means to promote the sectional economic interests of big business.<ref name="28th Party Program" /> | |||

| In 1932 ], then head of the CPUSA published a book entitled '']'', which laid out the Communist Party's plans for revolution and the building of a new socialist society based on the model of Soviet Russia. | |||

| In opposition to what it considers the ultimate agenda of the conservative wing of American politics, the Communist Party rejects foreign policy proposals such as the ], rejecting the right of the American government to attack "any country it wants, to conduct war without end until it succeeds everywhere, and even to use 'tactical' nuclear weapons and militarize space. Whoever does not support the U.S. policy is condemned as an opponent. Whenever international organizations, such as the United Nations, do not support U.S. government policies, they are reluctantly tolerated until the U.S. government is able to subordinate or ignore them".<ref name="28th Party Program" /> | |||

| ===The Popular Front (1935-1939)=== | |||

| The ideological rigidity of the third period began to crack, however, with two events: the election of ] in ] and ]'s rise to power in ]. Roosevelt's election and the passage of the ] in ] sparked a tremendous upsurge in union organizing in 1933 and 1934. While the party line still favored creation of autonomous revolutionary unions, party activists chose to fold up those organizations and follow the mass of workers into the AFL unions they had been attacking. | |||

| Juxtaposing the support from the ] and the right-wing of the ] for the ]-led ] with the many millions of Americans who opposed the invasion of Iraq from its beginning, the Communist Party notes the spirit of opposition towards the war coming from the American public: | |||

| The ] made the change in line official in ], when it declared the need for a "popular front" of all groups opposed to fascism. The CPUSA abandoned its opposition to the New Deal and provided many of the organizers for the ]. | |||

| {{blockquote|Thousands of grassroots peace committees organized by ordinary Americans{{nbsp}}... neighborhoods, small towns and universities expressing opposition in countless creative ways. Thousands of actions, vigils, teach-ins and newspaper advertisements were organized. The largest demonstrations were held since the Vietnam War. 500,000 marched in New York after the war started. Students at over 500 universities conducted a Day of Action for "]." | |||

| The party also sought unity with forces to its right. Earl Browder offered to run as ]' ] on a joint Socialist Party-Communist Party ticket in the ] but Thomas rejected this overture. | |||

| Over 150 anti-war resolutions were passed by city councils. Resolutions were passed by thousands of local unions and community organizations. Local and national actions were organized on the Internet, including the "Virtual March on Washington DC"{{nbsp}}.... Elected officials were flooded with millions of calls, emails and letters. | |||

| The gesture did not mean that much in practical terms, since the CPUSA was, by ], effectively supporting Roosevelt in much of its trade union work. While continuing to run its own candidates for office the CPUSA pursued a policy of representing the ] as the lesser evil in elections. | |||

| In an unprecedented development, large sections of the US labor movement officially opposed the war. In contrast, it took years to build labor opposition to the Vietnam War.{{nbsp}}... For example in Chicago, labor leaders formed Labor United for Peace, Justice and Prosperity. They concluded that mass education of their members was essential to counter false propaganda, and that the fight for the peace, economic security and democratic rights was interrelated.<ref>Bachtell, John. "The Movements Against War and Capitalist Globalization". ''CPUSA Online''. July 17, 2003. Retrieved April 15, 2009. {{cite web |url=http://www.cpusa.org/article/articleview/565/0/ |title=CPUSA Online – the movements against war and capitalist globalization |access-date=April 15, 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20031107092022/http://www.cpusa.org/article/articleview/565/0/ |archive-date=November 7, 2003}}</ref>}} | |||

| Party members also rallied to the defense of the ] during this period after a ] military uprising moved to overthrow it, resulting in the ] (] to ]). The CPUSA, along with leftists throughout the world, raised funds for medical relief while many of its members made their way to Spain with the aid of the party to join the ], one of the ]. Among its other achievements, the Lincoln Brigade was the first American military force to include blacks and whites integrated on an equal basis. | |||

| The party has consistently opposed American involvement in the ], the ], the ] and the post-] conflicts in both ] and ]. | |||

| Intellectually, the Popular Front period saw the development of a strong communist influence in intellectual and artistic life. This was often through various organizations influenced or controlled by the Party or, as they were pejoratively known, "]." | |||

| The Communist Party does not believe that the threat of terrorism can be resolved through war.<ref>. ''CPUSA Online''. October 8, 2001. Retrieved April 6, 2009.</ref> | |||

| ===The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and World War II (1939-1945)=== | |||

| ])]] | |||

| The CPUSA was adamantly opposed to fascism during the Popular Front period. Although membership in the CPUSA rose to about 75,000 by 1938, many members left the party after the signing of the ] ] of 1939. Signing of a pact with ] meant that the CPUSA turned the focus of its public activities from anti-fascism to an advocate of peace. The CPUSA accused ] and Roosevelt of provoking aggression against Hitler and denouncing the ] government as fascist after the German and Soviet invasion. In allegiance to the Soviet Union, the party changed this policy again after Hitler attacked the Soviet Union on ], ]. So sudden was this change that CPUSA members of the UAW negotiating on behalf of the union reportedly changed their position from favoring strike action to opposing it in the same negotiating session. | |||

| === Women and minorities === | |||

| Throughout the rest of ], the CPUSA continued a policy of militant, if sometimes bureaucratic trade unionism to opposing strike actions at all costs. The leadership of the CPUSA was among the most vocal pro war voices in the United States, advocating unity against fascism, not opposing the prosecution of leaders of the ] under the newly enacted ], and opposing ]'s efforts to organize a march on Washington to dramatize black workers' demands for equal treatment on the job. Prominent CPUSA members, such as ] and ], recalled anti-war material they had previously released. | |||

| ] and ] leaving the courthouse during the ] in 1949–1958]] | |||

| The Communist Party Constitution defines the U.S. working class as "multiracial and multinational. It unites men and women, young and old, gay and straight, native-born and immigrant, urban and rural." The party further expands its interpretation to include the employed and unemployed, organized and unorganized, and of all occupations.<ref name="2014constitution">. Amended July 8, 2001, at the 27th National Convention, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Retrieved November 11, 2011.</ref> | |||

| The Communist Party seeks equal rights for women, equal pay for equal work and the protection of reproductive rights, together with putting an end to sexism.<ref>Myles, Dee. . Speech given at the 27th National Convention of the CPUSA. ''Communist Party USA''. ''CPUSA Online''. July 7, 2001. Retrieved April 7, 2009.</ref> They support the right of abortion and social services to provide access to it, arguing that unplanned pregnancy is prejudiced against poor women.<ref>{{cite web |last=Kern |first=Michelle |date=June 27, 2016 |title=What is the CPUSA's position on abortion rights? |url=http://www.cpusa.org/interact_cpusa/what-is-the-cpusas-position-on-abortion/ |access-date=August 22, 2018 |website=Cpusa.org}}</ref> The party's ranks include a Women's Equality Commission, which recognizes the role of women as an asset in moving towards building socialism.<ref>Trowbdrige, Carolyn. . ''CPUSA Online''. March 8, 2009. Retrieved April 7, 2009.</ref> | |||

| ===The Onset of the Cold War=== | |||

| Earl Browder expected the wartime coalition between the Soviet Union and the west to bring about a prolonged period of social harmony after the war. In order to better integrate the communist movement into American life the party was officially dissolved in ] and replaced by a Communist Political Association. | |||

| Historically significant in American history as an early fighter for African Americans' rights and playing a leading role in protesting the lynchings of African Americans in the South, the Communist Party in its national program today calls racism the "classic divide-and-conquer tactic".<ref group="note">See also ] and the article on the ] for the Communist Party's work in promoting minority rights and involvement in the historically significant case of the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s.</ref><ref>Section 3d: . ''CPUSA Online''. May 19, 2006. Retrieved April 7, 2009.</ref> From its New York City base, the Communist Party's Ben Davis Club and other Communist Party organizations have been involved in local activism in ] and other African American and minority communities.<ref>"CPUSA Members Mark 5th Anniversary of the War: Ben Davis Club Remembers Those Lost". ''CPUSA Online''. March 20, 2008. Retrieved April 7, 2009. {{cite web |url=http://www.cpusa.org/article/view/906/ |title=CPUSA Online – CPUSA members mark 5th anniversary of the war |access-date=April 7, 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090719194315/http://www.cpusa.org/article/view/906/ |archive-date=July 19, 2009}}</ref> The Communist Party was instrumental in the founding of the ] ] in 1998, as well as the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.columbia.edu/~lnp3/mydocs/race/solomon.htm |title=Blacks and the CPUSA (by L. Proyect) |website=www.columbia.edu |access-date=November 27, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| That harmony proved elusive, however, and the international communist movement swung to the left after the war ended. Browder found himself isolated when a critical letter from the leader of the ] received wide circulation. As a result of this, he was retired and replaced by ], who would remain the senior leader of the party until his own retirement in ]. | |||

| Historically significant in ] working class history as a successful organizer of the Mexican American working class in the Southwestern United States in the 1930s, the Communist Party regards working-class Latino people as another oppressed group targeted by overt racism as well as systemic discrimination in areas such as education and sees the participation of Latino voters in a general mass movement in both party-based and nonpartisan work as an essential goal for major left-wing progress.<ref>García, Mario T. ''Mexican Americans: Leadership, Ideology, and Identity, 1930–1960''. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1991. {{ISBN|978-0300049848}}.</ref> | |||

| In line with other communist parties worldwide, the CPUSA also swung to the left and, as a result, experienced a brief period in which a number of internal critics argued for a more leftist stance than the leadership was willing to countenance. The result was the expulsion of a handful of "premature anti-revisionists". | |||

| The Communist Party holds that racial and ethnic discrimination not only harms minorities, but is pernicious to working-class people of all backgrounds as any discriminatory practices between demographic sections of the working class constitute an inherently divisive practice responsible for "obstructing the development of working-class consciousness, driving wedges in class unity to divert attention from ], and creating extra profits for the capitalist class".<ref>. Amended July 8, 2001, at the 27th National Convention, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Retrieved August 29, 2006.</ref><ref group="note">See also Executive Vice Chair ]'s ideological essay . ''CPUSA Online''. August 1, 2003. Retrieved April 7, 2009.</ref> | |||

| More important for the party was the renewal of state persecution of the CPUSA. The ] administration's loyalty oath program, introduced in ], drove some leftists out of federal employment and, more importantly, legitimized the notion of communists as subversives, to be exposed and expelled from public and private employment. The ], whose hearings were perceived as forums where current and former Communists and those sympathetic to Communism were compelled under the duress of the ruin of their careers to confess and name other Communists, made even brief affiliation with the CPUSA or any related groups grounds for public exposure and attack, inspiring local governments to adopt loyalty oaths and investigative commissions of their own. Private parties, such as the motion picture industry and self-appointed watchdog groups, extended the policy still further. This included the still controversial ] of actors, writers and directors in Hollywood who had been Communists or who had fallen in with Communist-controlled or influenced organizations in the pre-war and wartime years. | |||

| The Communist Party supports an end to ].<ref name="Immediate Program">. {{webarchive |url=http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20090708121226/http://www.cpusa.org/article/static/511/ |date=July 8, 2009}}. Retrieved August 29, 2006.</ref> The party supports continued enforcement of ] laws as well as ].<ref name="Immediate Program" /> | |||

| The union movement purged party members as well. The CIO formally expelled a number of left-led unions in ] after internal disputes triggered by the party's support for ]'s candidacy for ] and its opposition to the ], while other labor leaders sympathetic to the CPUSA either were driven out of their unions or dropped their alliances with the party. | |||

| == Geography == | |||

| The widespread fear of communism became even more acute after the Soviets' explosion of an ] in ] and discovery of Soviet espionage . Ambitious politicians, including ] and ], made names for themselves by exposing or threatening to expose Communists within the Truman administration or later, in McCarthy's case, within the ]. Liberal groups, such as the ], not only distanced themselves from communists and communist causes, but defined themselves as anti-communist. | |||

| <!-- Deleted image removed: project at the University of Washington]] --> | |||

| The Communist Party garnered support in particular communities, developing a unique geography. Instead of a broad nationwide support, support for the party was concentrated in different communities at different times, depending on the organizing strategy at that moment. | |||

| Before ], the Communist Party had relatively stable support in ], ] and ]. However, at times the party also had strongholds in more rural counties such as ] (22% in ]), ] (4% in ]), or ] (5% in ]).<ref name="Communist Party votes by county">{{cite web |url=https://depts.washington.edu/moves/CP_map-votes.shtml |title=Communist Party votes by county |website=depts.washington.edu |access-date=July 20, 2017}}</ref> Even in the ] at the height of ], the Communist Party had a significant presence in ]. Despite the ] of ], the party gained 8% of the votes in rural ]. This was mostly due to the successful biracial organizing of ] through the ].<ref name="Communist Party votes by county" /><ref name="Kelley-1990" /> | |||

| One of America's most prominent sexual radicals, ], developed his political views as an active member of the CPUSA, but his founding in the early ] of the ]—America's first gay rights group was not seen as something Communists, who feared even further political prosecution, should associate with organizationally, despite their personal support. In 2004, the editors of '']'' published articles detailing and praised Hay's work. | |||

| Unlike open mass organizations like the ] or the ], the Communist Party was a disciplined organization that demanded strenuous commitments and frequently expelled members. Membership levels remained below 20,000 until 1933 and then surged upward in the late 1930s, reaching 66,000 in 1939 and reaching its peak membership of over 75,000 in 1947.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Communist Party membership by Districts 1922–1950 – Mapping American Social Movements |url=https://depts.washington.edu/moves/CP_map-members.shtml |access-date=December 9, 2022 |website=depts.washington.edu}}</ref> | |||

| ===1950s and 1960s=== | |||

| {{seealso|New Communist Movement|Progressive Labor Party}} | |||

| The ] and the ] of ] to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union criticizing Stalin had a cataclysmic effect on the CPUSA . Membership plummeted and the leadership briefly faced a challenge from a loose grouping led by '']'' editor ], which wished to democratize the party. Perhaps the greatest single blow dealt to the party in this period was the loss of the ''Daily Worker'', published since ], which was suspended in ] due to falling circulation. | |||

| The party fielded candidates in presidential and many state and local elections not expecting to win, but expecting loyalists to vote the party ticket. The party mounted symbolic yet energetic campaigns during each presidential election from 1924 through 1940 and many gubernatorial and congressional races from 1922 to 1944. | |||

| Most of the critics would depart from the party demoralized, but others would remain active in progressive causes and would often end up working harmoniously with party members. This ] rapidly came to provide the audience for publications like the ''National Guardian'' and ''Monthly Review'', which were to be important in the development of the ] in the ]. | |||

| The Communist Party organized the country into districts that did not coincide with state lines, initially dividing it into 15 districts identified with a headquarters city with an additional "Agricultural District". Several reorganizations in the 1930s expanded the number of districts.<ref>.</ref> | |||

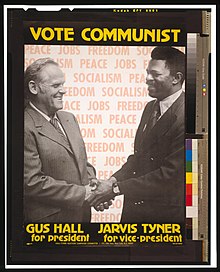

| The post-1956 upheavals in the CPUSA also saw the advent of a new leadership around former steel worker ]. Hall's views were very much those of his mentor Foster, but the younger man was to be more rigorous in ensuring the party was completely orthodox than the older man in his last years. Therefore, while remaining critics who wished to liberalize the party were expelled, so too were ] critics who took an anti-] stance. | |||

| == Relations with other groups == | |||

| Many of these critics were elements on both U.S. coasts who would come together to form the ] in 1961. Progressive Labor would come to play a role in many of the numerous ] organizations of the mid-] and early ]. ], Foster's secretary, also played a role in these organizations; he was not expelled from the CP, but resigned. In the ], the CPUSA managed to grow in membership to about 25,000 members, despite the exodus of numerous ] and ] groups from its ranks. | |||

| === United States labor movement === | |||

| {{main|Communists in the United States Labor Movement (1919–37)|Communists in the United States Labor Movement (1937–50)|l1=Communists in the United States labor movement (1919–1937)|l2=Communists in the United States labor movement (1937–1950)}} | |||

| ] parade with banners and flags, New York]] | |||

| The Communist Party has sought to play an active role in the labor movement since its origins as part of its effort to build a mass movement of American workers to bring about their own liberation through socialist revolution. | |||

| === Soviet funding and espionage === | |||

| ===Current Era=== | |||

| From 1959 until 1989, when ] condemned the initiatives taken by ] in the Soviet Union, the Communist Party received a substantial subsidy from the Soviets. There is at least one receipt signed by Gus Hall in the KGB archives.<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Klehr|first1=Harvey|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u-o5jqehzvcC&pg=PA155|title=The Soviet World of American Communism|last2=Haynes|first2=John Earl|last3=Anderson|first3=Kyrill M.|date= 2008|publisher=Yale University Press|isbn=978-0300138009|page=155|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|last=Dobbs|first=Michael|date=February 8, 1992|title=U.S. Party Said Funded by Kremlin|language=en-US|newspaper=Washington Post|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1992/02/08/us-party-said-funded-by-kremlin/421119eb-6953-413d-baf0-3558cbeb7e48/|access-date=November 10, 2021|issn=0190-8286}}</ref> Starting with $75,000 in 1959, this was increased gradually to $3 million in 1987. This substantial amount reflected the party's loyalty to the Moscow ], in contrast to the ] and later ] and ] Communist parties, whose ] deviated from the orthodox line in the late 1970s. Releases from the Soviet archives show that all national Communist parties that conformed to the Soviet line were funded in the same fashion. From the Communist point of view, this international funding arose from the internationalist nature of communism itself as fraternal assistance was considered the duty of communists in any one country to give aid to their allies in other countries. From the anti-Communist point of view, this funding represented an unwarranted interference by one country in the affairs of another. The cutoff of funds in 1989 resulted in a financial crisis, which forced the party to cut back publication in 1990 of the party newspaper, the ''People's Daily World'', to weekly publication, the '']'' (]). | |||

| Somewhat more controversial than mere funding is the alleged involvement of Communist members in espionage for the Soviet Union. ] alleged that Sandor Goldberger—also known as Josef Peters, who commonly wrote under the name ]—headed the Communist Party's underground secret apparatus from 1932 to 1938 and pioneered its role as an auxiliary to Soviet intelligence activities.<ref name="Witness">{{cite book |last1=Chambers |first1=Whittaker |title=Witness |publisher=Random House|orig-year=1952 |year=1987 |location=New York |page=799 |isbn=978-0895267894 |lccn=52005149}}</ref> Bernard Schuster, Organizational Secretary of the New York District of the Communist Party, is claimed to have been the operational recruiter and conduit for members of the party into the ranks of the secret apparatus, or "Group A line". | |||

| In ], due to the popularity of ]'s anti-Communist administration and decreased CPUSA membership, Gus Hall chose to end the CPUSA's nation-wide electoral campaigns. But in the decade ending in 1989, the membership in the CPUSA grew from 10,000 to 50,000, making it the fastest growing major party on the Left in the US. | |||

| Stalin publicly disbanded the ] in 1943. A Moscow NKVD message to all stations on September 12, 1943, detailed instructions for handling intelligence sources within the Communist Party after the disestablishment of the Comintern. | |||

| Terri Albano, a high-ranking party member, stated in 1998 that membership was still around 50,000.{{fact}} During the 1990's, the party recruited heavily in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in the US, particularly in Black neighborhoods. As a result, there are many young Black and Hispanic members of the CPUSA. The CPUSA still runs candidates for local office. In recent years, the party has strongly opposed the Republican Party in the US, who they term "ultra-right" and, at times, "fascist". As part of a pragmatic stance, the CPUSA strongly supports the Democratic Party against the Republicans, as they see the Republican Party as a menace to be defeated. The Communist Party still maintains that both parties are capitalist in nature, and only support the Democrats as a means to topple conservative domination in America. | |||

| There are a number of decrypted World War II Soviet messages between NKVD offices in the United States and Moscow, also known as the ]. The Venona cables and other published sources appear to confirm that ] was responsible for espionage. ], a Harvard-trained ] who did not join the party until 1952, began passing information on the atomic bomb to the Soviets soon after he was hired at ] at age 19. Hall, who was known as Mlad by his KGB handlers, escaped prosecution. Hall's wife, aware of his espionage, claims that their NKVD handler had advised them to plead innocent, as the Rosenbergs did, if formally charged.<ref>{{Cite web|title=NOVA Online {{!}} Secrets, Lies, and Atomic Spies {{!}} Read Venona Intercepts|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/venona/intercepts.html|access-date=August 14, 2021|website=www.pbs.org}}</ref> | |||

| Ideologically, much appears to be up for grabs. A recent CPUSA theoretical journal voiced support for the Chinese Communist Party, including their heavy reliance on capitalism. The article stated, "The transition to capitalism may be more on order of decades than years, as Lenin had thought." The same article said, "Democracy is an essential element of any socialist system." | |||

| It was the belief of opponents of the Communist Party such as ], longtime director of the FBI; and ], for whom ] is named; and other ] that the Communist Party constituted an active ], was secretive, loyal to a foreign power and whose members assisted Soviet intelligence in the clandestine ] of American government. This is the traditionalist view of some in the field of ] such as ] and ], since supported by several memoirs of ex-Soviet KGB officers and information obtained from the ] and Soviet archives.<ref name="Haynes, John Earl 2000">Haynes, John Earl, and Klehr, Harvey, ''Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America'', Yale University Press (2000).</ref><ref>Schecter, Jerrold and Leona, ''Sacred Secrets: How Soviet Intelligence Operations Changed American History'', Potomac Books (2002).</ref><ref>Sudoplatov, Pavel Anatoli, Schecter, Jerrold L., and Schecter, Leona P., ''Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness – A Soviet Spymaster'', Little Brown, Boston (1994).</ref> | |||

| ==Soviet funding of the Party and espionage== | |||

| From ] until ], when Gus Hall attacked the initiatives taken by ] in the ], the CPUSA received a substantial subsidy from the Soviet Union. There is at least one receipt signed by Gus Hall in the KGB archives. Starting with $75,000 in 1959 this was increased gradually to $3,000,000 in ]. This substantial amount reflected the Party's subservience to the Moscow ], in contrast to the ] and later ] Communist parties, whose ] deviated from the orthodox line in the late 1970s. Releases from the Soviet archives show that all national Communist parties that conformed to the Soviet line were funded in the same fashion. From the Communist point of view this international funding arose from the internationalist nature of Communism itself; fraternal assistance was considered the duty of Communists in any one country to give aid to their comrades in other countries. From the anti-communist point of view, this funding represented an unwarranted interference by one country in the affairs of another. | |||

| At one time, this view was shared by the majority of the ]. In the "Findings and declarations of fact" section of the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950 (50 U.S.C. Chap. 23 Sub. IV Sec. 841), it stated: | |||

| The cutoff of funds in 1989 resulted in a financial crisis, which forced the CPUSA to cut back publication in ] of the Party newspaper, the ''People's Daily World'', to weekly publication, the '']''. (references for this section are provided ]) | |||

| <blockquote>he Communist Party, although purportedly a political party, is in fact an instrumentality of a conspiracy to overthrow the Government of the United States. It constitutes an authoritarian dictatorship within a republic{{nbsp}}... the policies and programs of the Communist Party are secretly prescribed for it by the foreign leaders{{nbsp}}... to carry into action slavishly the assignments given{{nbsp}}.... he Communist Party acknowledges no constitutional or statutory limitations{{nbsp}}.... The peril inherent in its operation arises its dedication to the proposition that the present constitutional Government of the United States ultimately must be brought to ruin by any available means, including resort to force and violence{{nbsp}}... its role as the agency of a hostile foreign power renders its existence a clear present and continuing danger.<ref>. U.S. Code collection on the site of ]. Retrieved August 30, 2006.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Much more controversial than mere funding, however, is the alleged involvement of CPUSA members in espionage for the Soviet Union. ] has alleged that Sandor Goldberger—also known as "Josef Peters": he commonly wrote under the name ]—headed the CPUSA’s underground secret apparatus from 1932 to 1938 and pioneered its role as an auxiliary to Soviet intelligence activities. ], Organizational Secretary of the New York District of the CPUSA, is claimed to have been the operational recruiter and conduit for members of the CPUSA into the ranks of the secret apparatus, or "Group A line". | |||