| Revision as of 12:38, 29 February 2016 editTrappist the monk (talk | contribs)Administrators479,973 editsm →Duodecimal digits on computerized writing systems: crudely translate Internetquelle to cite web; using AWB← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:51, 11 January 2025 edit undoThelurkingeditor (talk | contribs)46 edits →In media: rewrote for clarity, corrected punctuation and grammarTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Base-12 numeral system}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Dewey Decimal Classification}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Dewey Decimal Classification|Duodecimo}} | |||

| {{Special characters}} | |||

| {{Numeral systems}} | {{Numeral systems}} | ||

| The '''duodecimal''' system |

The '''duodecimal''' system, also known as '''base twelve''' or '''dozenal''', is a ] ] using ] as its ]. In duodecimal, the number twelve is denoted "10", meaning 1 twelve and 0 ]; in the ] system, this number is instead written as "12" meaning 1 ten and 2 units, and the string "10" means ten. In duodecimal, "100" means twelve ], "1000" means twelve ], and "0.1" means a twelfth. | ||

| | url = http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U2150.pdf | |||

| | title = The Unicode Standard 8.0 | |||

| | accessdate = 2014-07-18 | |||

| }}</ref> Other notations use "A", "T", or "X" for ten and "B" or "E" for eleven. The number twelve (that is, the number written as "12" in the ] numerical system) is instead written as "10" in duodecimal (meaning "1 ] and 0 units", instead of "1 ten and 0 units"), whereas the digit string "12" means "1 dozen and 2 units" (i.e. the same number that in decimal is written as "14"). Similarly, in duodecimal "100" means "1 ]", "1000" means "1 ]", and "0.1" means "1 twelfth" (instead of their decimal meanings "1 hundred", "1 thousand", and "1 tenth"). | |||

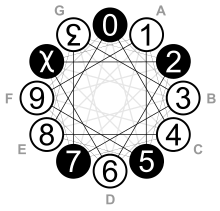

| Various symbols have been used to stand for ten and eleven in duodecimal notation; this page uses {{d2}} and {{d3}}, as in ], which make a duodecimal count from zero to twelve read 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, {{d2}}, {{d3}}, 10. The Dozenal Societies of America and Great Britain (organisations promoting the use of duodecimal) use turned digits in their published material: <span style="display: inline-block; transform: scale(-1);">2</span> (a turned 2) for ten and <span style="display: inline-block; transform: scale(-1);">3</span> (a turned 3) for eleven. | |||

| The number twelve, a ], is the smallest number with four non-trivial ] (2, 3, 4, 6), and the smallest to include as factors all four numbers (1 to 4) within the ] range. As a result of this increased factorability of the ] and its divisibility by a wide range of the most elemental numbers (whereas ten has only two non-trivial factors: 2 and 5, and not 3, 4, or 6), duodecimal representations fit more easily than decimal ones into many common patterns, as evidenced by the higher regularity observable in the duodecimal multiplication table. As a result, duodecimal has been described as the optimal number system.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://io9.com/5977095/why-we-should-switch-to-a-base+12-counting-system | |||

| The number twelve, a ], is the smallest number with four non-trivial ] (2, 3, 4, 6), and the smallest to include as factors all four numbers (1 to 4) within the ] range, and the smallest ]. All multiples of ] of ] numbers ({{math|{{sfrac|''a''|2<sup>''b''</sup>·3<sup>''c''</sup>}}}} where {{mvar|a,b,c}} are integers) have a ] representation in duodecimal. In particular, {{sfrac||1|4}} (0.3), {{sfrac||1|3}} (0.4), {{sfrac||1|2}} (0.6), {{sfrac||2|3}} (0.8), and {{sfrac||3|4}} (0.9) all have a short terminating representation in duodecimal. There is also higher regularity observable in the duodecimal multiplication table. As a result, duodecimal has been described as the optimal number system.<ref name="io9">{{cite web |author=Dvorsky |first=George |date=January 18, 2013 |title=Why We Should Switch To A Base-12 Counting System |url=http://io9.com/5977095/why-we-should-switch-to-a-base+12-counting-system |access-date=December 21, 2013 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| | title = Why We Should Switch To A Base-12 Counting System | |||

| | author = George Dvorsky | |||

| In these respects, duodecimal is considered superior to decimal, which has only 2 and 5 as factors, and other proposed bases like ] or ]. ] (base sixty) does even better in this respect (the reciprocals of all ] numbers terminate), but at the cost of unwieldy multiplication tables and a much larger number of symbols to memorize. | |||

| | date = 2013-01-18 | |||

| | accessdate = 2013-12-21 | |||

| }}</ref> Of its factors, 2 and 3 are ], which means the ] of all ] numbers (such as 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9...) have a ] representation in duodecimal. In particular, the five most elementary fractions ({{sfrac|1|2}}, {{sfrac|1|3}}, {{sfrac|2|3}}, {{sfrac|1|4}} and {{sfrac|3|4}}) all have a short terminating representation in duodecimal (0.6, 0.4, 0.8, 0.3 and 0.9, respectively), and twelve is the smallest radix with this feature (because it is the ] of 3 and 4). This all makes it a more convenient number system for computing fractions than most other number systems in common use, such as the ], ], ], ] and ] systems. Although the ] and ] systems (where the reciprocals of all ] numbers terminate) do even better in this respect, this is at the cost of unwieldy multiplication tables and a much larger number of symbols to memorize. | |||

| == Origin == | == Origin == | ||

| :''In this section, numerals are |

:''In this section, numerals are in ]. For example, "10" means 9+1, and "12" means 9+3.'' | ||

| ] speculatively traced the origin of the duodecimal system to a system of ] based on the knuckle bones of the four larger fingers. Using the thumb as a pointer, it is possible to count to 12 by touching each finger bone, starting with the farthest bone on the fifth finger, and counting on. In this system, one hand counts repeatedly to 12, while the other displays the number of iterations, until five dozens, i.e. the 60, are full. This system is still in use in many regions of Asia.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Pittman |first=Richard |date=1990 |title=Origin of Mesopotamian duodecimal and sexagesimal counting systems |journal=Philippine Journal of Linguistics |volume=21 |issue=1 |page=97}}</ref><ref name="Ifrah 2000">{{Cite book| last = Ifrah| first = Georges| author-link = Georges Ifrah| title = The Universal History of Numbers: From prehistory to the invention of the computer| publisher = Wiley | year=2000 |orig-year=1st French ed. 1981 | isbn = 0-471-39340-1}} Translated from the French by David Bellos, E. F. Harding, Sophie Wood and Ian Monk.</ref> | |||

| Languages using duodecimal number systems are uncommon. Languages in the ]n Middle Belt such as ], ] (Gure-Kahugu), ], and the Nimbia dialect of ];<ref>{{Cite |

Languages using duodecimal number systems are uncommon. Languages in the ]n Middle Belt such as ], ] (Gure-Kahugu), ], and the Nimbia dialect of ];<ref>{{Cite web |last=Matsushita |first=Shuji |date=October 1998 |title=Decimal vs. Duodecimal: An interaction between two systems of numeration |url=http://www3.aa.tufs.ac.jp/~P_aflang/TEXTS/oct98/decimal.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081005230737/http://www3.aa.tufs.ac.jp/~P_aflang/TEXTS/oct98/decimal.html |archive-date=October 5, 2008 |access-date=May 29, 2011 |website=www3.aa.tufs.ac.jp}}</ref> and the ] of ]<ref>{{Cite book | ||

| | title=Decimal vs. Duodecimal: An interaction between two systems of numeration | |||

| | last=Matsushita | |||

| | first=Shuji | |||

| | conference=2nd Meeting of the AFLANG, October 1998, Tokyo | |||

| | year=1998 | |||

| | url=http://www3.aa.tufs.ac.jp/~P_aflang/TEXTS/oct98/decimal.html | |||

| | archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20081005230737/http://www3.aa.tufs.ac.jp/~P_aflang/TEXTS/oct98/decimal.html | |||

| | archivedate=2008-10-05 | |||

| | accessdate=2011-05-29 | |||

| | postscript=<!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}} | |||

| }}</ref> the ] of ]<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| | contribution=Les principes de construction du nombre dans les langues tibéto-birmanes | | contribution=Les principes de construction du nombre dans les langues tibéto-birmanes | ||

| | first=Martine | | first=Martine | ||

| Line 37: | Line 22: | ||

| | editor-first=Jacques | | editor-first=Jacques | ||

| | editor-last=François | | editor-last=François | ||

| | |

| date=2002 | ||

| | pages=91–119 | | pages=91–119 | ||

| | publisher=Peeters | | publisher=Peeters | ||

| Line 43: | Line 28: | ||

| | isbn=90-429-1295-2 | | isbn=90-429-1295-2 | ||

| | url=http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/documents/publi/num_WEB.pdf | | url=http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/documents/publi/num_WEB.pdf | ||

| | access-date=2014-03-27 | |||

| | postscript=<!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}} | |||

| | archive-date=2016-03-28 | |||

| }}</ref> and the ] of ] in ] are known to use duodecimal numerals. In fiction, ]'s ] can express numbers either decimally (in ], ''maquanótië'' "hand-counting" or *''quaistanótië'' "tenth-counting") or duodecimally (presumably *''rastanótië'' "dozen-counting").<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Tolkien|first1=Christopher|last2=Tolkien|first2=John|editor1-last=Doughan|editor1-first=David|editor2-last=Julian|editor2-first=Bradfiend|title=The Writing Systems of Middle-earth|journal=Quetters|date=1987|volume=Special Publication|issue=1|url=http://tolklang.quettar.org/numbers.ps|postscript=<!--I can't upload image file "http://elvenesse.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/ElvishNoChart.jpg"-->}}</ref> | |||

| | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160328145817/http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/documents/publi/num_WEB.pdf | |||

| | url-status=dead | |||

| }}</ref> are known to use duodecimal numerals. | |||

| ] have special words for 11 and 12, such as ''eleven'' and ''twelve'' in ]. |

] have special words for 11 and 12, such as ''eleven'' and ''twelve'' in ]. They come from ] *''ainlif'' and *''twalif'' (meaning, respectively, ''one left'' and ''two left''), suggesting a decimal rather than duodecimal origin.<ref>{{cite book|last=von Mengden| first=Ferdinand| date=2006|chapter=The peculiarities of the Old English numeral system |title=Medieval English and its Heritage: Structure Meaning and Mechanisms of Change|editor1=Nikolaus Ritt |editor2=Herbert Schendl |editor3=Christiane Dalton-Puffer |editor4=Dieter Kastovsky|publisher=Peter Lang |series=Studies in English Medieval Language and Literature |volume=16 |location=Frankfurt |pages= 125–145}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=von Mengden |first=Ferdinand |date=2010| title=Cardinal Numerals: Old English from a Cross-Linguistic Perspective |series=Topics in English Linguistics | volume=67|location= Berlin; New York|publisher=De Gruyter Mouton| pages=159–161}}</ref> However, ] used a hybrid decimal–duodecimal counting system, with its words for "one hundred and eighty" meaning 200 and "two hundred" meaning 240.<ref>{{cite book|last=Gordon|first=E V|title=Introduction to Old Norse|year=1957|publisher=Clarendon Press|location=Oxford|pages=292–293}}</ref> In the British Isles, this style of counting survived well into the Middle Ages as the ]. | ||

| Historically, ] of |

Historically, ] in many ]s are duodecimal. There are twelve signs of the ], twelve months in a year, and the ] had twelve hours in a day (although at some point, this was changed to 24). Traditional ]s, clocks, and compasses are based on the twelve ] or 24 (12×2) ]s. There are 12 inches in an imperial foot, 12 ] ounces in a troy pound, 12 ] in a ], 24 (12×2) hours in a day; many other items are counted by the ], ] (], ] of 12), or ] (], ] of 12). The Romans used a fraction system based on 12, including the ], which became both the English words '']'' and ''inch''. Pre-], ] and the ] used a mixed duodecimal-] currency system (12 pence = 1 shilling, 20 shillings or 240 pence to the ] or ]), and ] established a monetary system that also had a mixed base of twelve and twenty, the remnants of which persist in many places. | ||

| {| class="wikitable" style=text-align:center | {| class="wikitable" style=text-align:center | ||

| |+ Duodecimally divided units | |||

| ! colspan="6"|<big>Table of units from a base of 12</big> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Relative<br>value | ! rowspan=2 | Relative<br>value | ||

| ! colspan=2 | Length | |||

| ! French unit<br>of length | |||

| ! colspan=2 | Weight | |||

| ! English unit<br>of length | |||

| |- | |||

| ! English unit<br>of weight | |||

| ! French | |||

| ! Roman unit<br>of weight | |||

| ! English |

! English | ||

| ! English (Troy) | |||

| ! Roman | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |12<sup>0</sup> | |12<sup>0</sup> | ||

| Line 66: | Line 55: | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |12<sup>−1</sup> | |12<sup>−1</sup> | ||

| Line 73: | Line 61: | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |12<sup>−2</sup> | |12<sup>−2</sup> | ||

| Line 79: | Line 66: | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| |2 ] | |2 ] | ||

| |2 ] | |2 ] | ||

| |] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |12<sup>−3</sup> | |12<sup>−3</sup> | ||

| Line 86: | Line 72: | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| |] | |] | ||

| |] |

|] | ||

| |} | |||

| == Notations and pronunciations == | |||

| In a positional numeral system of base ''n'' (twelve for duodecimal), each of the first ''n'' natural numbers is given a distinct numeral symbol, and then ''n'' is denoted "10", meaning 1 times ''n'' plus 0 units. For duodecimal, the standard numeral symbols for 0–9 are typically preserved for zero through nine, but there are numerous proposals for how to write the numerals representing "ten" and "eleven".<ref name="Symbology Overview">{{cite journal|last=De Vlieger|first=Michael|title=Symbology Overview|journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin|volume=4X |issue=2|date=2010|url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue4a2_0.pdf }}</ref> More radical proposals do not use any ] under the principle of "separate identity."<ref name="Symbology Overview" /> | |||

| Pronunciation of duodecimal numbers also has no standard, but various systems have been proposed. | |||

| === Transdecimal symbols === | |||

| {{infobox symbol | |||

| |mark={{mono|1=<span style="display: inline-block; transform: scale(-1);">2</span>{{NBSP}}<span style="display: inline-block; transform: scale(-1);">3</span>}} | |||

| |name = duodecimal {{angbr|1=ten, eleven}} | |||

| |unicode={{ubli | |||

| | {{unichar|1=218A|2=TURNED DIGIT TWO}} | |||

| | {{unichar|1=218B|2=TURNED DIGIT THREE}} | |||

| }} | |||

| |unicode note=Block ] | |||

| |note={{ubli | |||

| |Arabic digits with 180° rotation, by ] | |||

| |In ], using the TIPA package:<ref name="LATEX">{{cite web |url=https://www.ctan.org/pkg/comprehensive |title=The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List |year=2021 |edition=14.0 |orig-year=2007 |last=Pakin |first=Scott |website=Comprehensive TEX Archive Network }} {{pb}} {{cite web |url=https://www.ctan.org/pkg/tipa |title=tipa – Fonts and macros for IPA phonetics characters |last=Rei |first=Fukui |year=2004 |orig-year=2002 |website=Comprehensive TEX Archive Network |edition=1.3 }} {{pb}} The turned digits 2 and 3 employed in the TIPA package originated in ''The Principles of the International Phonetic Association'', University College London, 1949.</ref><br/>{{angbr|1={{code|\textturntwo}}, {{code|1=\textturnthree}}}}}} | |||

| }} | |||

| Several authors have proposed using letters of the alphabet for the transdecimal symbols. Latin letters such as {{angbr|{{mono|1=A, B}}}} (as in ]) or {{angbr|{{mono|1=T, E}}}} (initials of ''Ten'' and ''Eleven'') are convenient because they are widely accessible, and for instance can be typed on typewriters. However, when mixed with ordinary prose, they might be confused for letters. As an alternative, Greek letters such as {{angbr|{{mono|1=τ, ε}}}} could be used instead.<ref name="Symbology Overview"/> Frank Emerson Andrews, an early American advocate for duodecimal, suggested and used in his 1935 book ''New Numbers'' {{angbr|{{mono|''X'', ''Ɛ''}}}} (italic capital X from the ] for ten and a rounded ] capital E similar to ]), along with italic numerals {{mono|''0''}}–{{mono|''9''}}.<ref name="New Numbers 1935"/> | |||

| Edna Kramer in her 1951 book ''The Main Stream of Mathematics'' used a {{angbr|{{mono|1=*, <nowiki>#</nowiki>}}}} (] or six-pointed asterisk, ] or octothorpe).<ref name="Symbology Overview"/> The symbols were chosen because they were available on some typewriters; they are also on ]s.<ref name="Symbology Overview"/> This notation was used in publications of the Dozenal Society of America (DSA) from 1974 to 2008.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Annual Meeting of 1973 and Meeting of the Board|journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin|volume=25 |issue=1|date=1974|url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue251-web_0.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=De Vlieger|first=Michael|title=Going Classic|journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin|volume=49 |issue=2|date=2008|url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue492_0.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| From 2008 to 2015, the DSA used {{angbr|1={{NNBSP}}], ]{{NNBSP}}}}, the symbols devised by ].<ref name="Symbology Overview"/><ref name="DB01">{{cite journal|title=Mo for Megro|journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin|volume=1|issue=1|date=1945|url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue011-web.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| The Dozenal Society of Great Britain (DSGB) proposed symbols {{angbr|1={{NNBSP}}<span style="display: inline-block; transform: scale(-1);">{{math|2}}</span>, <span style="display: inline-block; transform: scale(-1);">{{math|3}}</span>{{NNBSP}}}}.<ref name="Symbology Overview"/> This notation, derived from Arabic digits by 180° rotation, was introduced by ] in 1857.<ref name="Symbology Overview"/><ref name="Pitman1857">{{cite news |last=Pitman |first=Isaac |author-link=Isaac Pitman |title=A Reckoning Reform |newspaper=Bedfordshire Independent |date=24 November 1857 }} Reprinted as {{cite journal |last=Pitman |first=Isaac |display-authors=0 |title=Sir Isaac Pitman on the Dozen System: A Reckoning Reform |journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin |volume=3 |issue=2 |pages=1–5 |year=1947 |url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue032-web_0.pdf }}</ref> In March 2013, a proposal was submitted to include the digit forms for ten and eleven propagated by the Dozenal Societies in the ].<ref name="N4399">{{cite web |author=Pentzlin |first=Karl |date=March 30, 2013 |title=Proposal to encode Duodecimal Digit Forms in the UCS |url=https://www.unicode.org/wg2/docs/n4399.pdf |publisher=ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 |access-date=2024-06-25}}</ref> Of these, the British/Pitman forms were accepted for encoding as characters at code points {{unichar|218A|TURNED DIGIT TWO}} and {{unichar|218B|TURNED DIGIT THREE}}. They were included in ] (2015).<ref name="Unicode8">{{cite web|url=https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-8.0/U80-2150.pdf|title=The Unicode Standard, Version 8.0: Number Forms|publisher=Unicode Consortium|access-date=2016-05-30}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U2150.pdf | |||

| | title = The Unicode Standard 8.0 | |||

| | access-date = 2014-07-18 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| After the Pitman digits were added to Unicode, the DSA took a vote and then began publishing PDF content using the Pitman digits instead, but continues to use the letters X and E on its webpage.<ref>{{Cite web |last=The Dozenal Society of America |date=n.d. |title=What should the DSA do about transdecimal characters? |url=https://dozenal.org/drupal/content/what-should-dsa-do-about-transdecimal-characters.html |access-date=January 1, 2018 |website=Dozenal Society of America |publisher=The Dozenal Society of America}}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" id="transdecimal-symbols-table" style="font-size:90%; max-width:50em;" | |||

| ! colspan=2 | Symbols | |||

| ! style="width:20em" | Background | |||

| ! Note | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big>A</big> | |||

| | <big>B</big> | |||

| | As in ] | |||

| | Allows entry on typewriters. | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big>T</big> | |||

| | <big>E</big> | |||

| | Initials of ''Ten'' and ''Eleven'' | |||

| | Used (in lower case) in ]<ref>], ''The Cambridge Introduction to Serialism'' (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008): 276. {{ISBN|978-0-521-68200-8}} (pbk).</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big>X</big> | |||

| | <big>E</big> | |||

| | X from the ]; <br> E from ''Eleven''. | |||

| | | | | ||

| |- | |||

| | <big>X</big> | |||

| | <big>Z</big> | |||

| | Origin of Z unknown | |||

| | Attributed to ] & ] by the DSA.<ref name="Symbology Overview" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big>δ</big> | |||

| | <big>ε</big> | |||

| | Greek ] from {{lang|grc|δέκα}} "ten"; <br> ] from {{lang|grc|ένδεκα}} "eleven"<ref name="Symbology Overview"/> | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big>τ</big> | |||

| | <big>ε</big> | |||

| | Greek ], ]<ref name="Symbology Overview"/> | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big>W</big> | |||

| | <big>∂</big> | |||

| | W from doubling the Roman numeral V; <br> ∂ based on a pendulum | |||

| | Silvio Ferrari in ''Calcolo Decidozzinale'' (1854).<ref name="Ferrari 1854">{{cite book|first=Silvio |last=Ferrari|title=Calcolo Decidozzinale|date=1854|page=2}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big>''X''</big> | |||

| | <big>''Ɛ''</big> | |||

| | italic ''X'' pronounced "dec"; <br> rounded ] ''Ɛ'', pronounced "elf" | |||

| | Frank Andrews in ''New Numbers'' (1935), with italic ''0''–''9'' for other duodecimal numerals.<ref name="New Numbers 1935">{{cite book|first=Frank Emerson |last=Andrews |title=New Numbers: How Acceptance of a Duodecimal (12) Base Would Simplify Mathematics |date=1935 |page=52 |publisher=Harcourt, Brace and company |url=https://archive.org/details/newnumbershowacc0000fran/page/52/mode/1up?q=%22quantity+eleven%22 |url-access=limited}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big>{{mono|1=*}}</big> | |||

| | <big>{{mono|1=<nowiki>#</nowiki>}}</big> | |||

| | ] or six-pointed asterisk,<br/>] or octothorpe | |||

| | On ]s; used by Edna Kramer in ''The Main Stream of Mathematics'' (1951); used by the DSA {{nobr|1974–2008}}<ref name="bellchange">{{cite journal|title=Annual Meeting of 1973 and Meeting of the Board|journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin|volume=25 |issue=1|date=1974|url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue251-web_0.pdf}}</ref><ref name="classic">{{cite journal|last=De Vlieger|first=Michael|title=Going Classic|journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin|volume=49 |issue=2|date=2008|url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue492_0.pdf}}</ref><ref name="Symbology Overview"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big><span style="display: inline-block; transform: scale(-1);">2</span></big> | |||

| | <big><span style="display: inline-block; transform: scale(-1);">3</span></big> | |||

| | {{ubli | |||

| | Digits 2 and 3 rotated 180° | |||

| }} | |||

| | ] (1857);<ref name="Pitman1857"/> used by the DSGB; used by the DSA since 2015; included in ] (2015)<ref name="Unicode8">{{cite web|url=https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-8.0/U80-2150.pdf|title=The Unicode Standard, Version 8.0: Number Forms|publisher=Unicode Consortium|access-date=2016-05-30}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U2150.pdf | |||

| | title = The Unicode Standard 8.0 | |||

| | access-date = 2014-07-18 }}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | <big>]</big> | |||

| | <big>]</big> | |||

| | Pronounced "dek", "el" | |||

| | {{ubl | |||

| |] (1945/1932?).<ref name="Symbology Overview"/><ref name="DB01">{{cite journal|title=Mo for Megro|journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin|volume=1|issue=1|date=1945|url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue011-web.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| |Used by the DSA 1945–1974 and 2008–2015<ref name="bellchange"/><ref name="classic" />}} | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ==={{anchor|Humphrey point}}Base notation=== | |||

| The importance of 12 has been attributed to the number of lunar cycles in a year, and also to the fact that humans have 12 finger bones (]) on one hand (three on each of four fingers).<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| There are also varying proposals of how to distinguish a duodecimal number from a decimal one. The most common method used in mainstream mathematics sources comparing various number bases uses a subscript "10" or "12", e.g. "54<sub>12</sub> = 64<sub>10</sub>". To avoid ambiguity about the meaning of the subscript 10, the subscripts might be spelled out, "54<sub>twelve</sub> = 64<sub>ten</sub>". In 2015 the Dozenal Society of America adopted the more compact single-letter abbreviation "z" for "do'''z'''enal" and "d" for "'''d'''ecimal", "54<sub>z</sub> = 64<sub>d</sub>".<ref name="Volan 2015">{{Cite journal |last=Volan |first=John |date=July 2015 |title=Base Annotation Schemes |url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue521.pdf |journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin |volume=62}}</ref> | |||

| | title=ヒマラヤの満月と十二進法 (The Full Moon in the Himalayas and the Duodecimal System) | |||

| | last=Nishikawa | |||

| | first=Yoshiaki | |||

| | year=2002 | |||

| | url=http://www.kankyok.co.jp/nue/nue11/nue11_01.html | |||

| | accessdate=2008-03-24 | |||

| | postscript=<!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}} | |||

| }}{{dead link|date=January 2014}}</ref> It is possible to count to 12 with the thumb acting as a pointer, touching each finger bone in turn. A traditional ] system still in use in many regions of Asia works in this way, and could help to explain the occurrence of numeral systems based on 12 and 60 besides those based on 10, 20 and 5. In this system, the one (usually right) hand counts repeatedly to 12, displaying the number of iterations on the other (usually left), until five dozens, i. e. the 60, are full.<ref name=Ifrah>{{Cite book | |||

| | last = Ifrah | |||

| | first = Georges | |||

| | author-link = Georges Ifrah | |||

| | title = The Universal History of Numbers: From prehistory to the invention of the computer | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | year= 2000 | |||

| | page = | |||

| | isbn = 0-471-39340-1 | |||

| | postscript = <!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}} | |||

| }}. Translated from the French by David Bellos, E.F. Harding, Sophie Wood and Ian Monk.</ref><ref name=Macey>{{Cite book|last=Macey|first=Samuel L.|title=The Dynamics of Progress: Time, Method, and Measure|year=1989|publisher=University of Georgia Press|location=Atlanta, Georgia|isbn=978-0-8203-3796-8|page=92|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=xlzCWmXguwsC&pg=PA92&lpg=PA92|postscript=<!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}}}}</ref> | |||

| Other proposed methods include italicizing duodecimal numbers "''54'' = 64", adding a "Humphrey point" (a ] instead of a ]) to duodecimal numbers "54;6 = 64.5", prefixing duodecimal numbers by an asterisk "*54 = 64", or some combination of these. The Dozenal Society of Great Britain uses an asterisk prefix for duodecimal whole numbers, and a Humphrey point for other duodecimal numbers.<ref name="Volan 2015" /> | |||

| == Places == | |||

| In a duodecimal place system, ] can be written as <span style="display:inline-block;top:0.5em;transform:matrix(-1, 0, 0, -1, 0, 0);-moz-transform: matrix(-1, 0, 0, -1, 0, 0);-webkit-transform: matrix(-1, 0, 0, -1, 0, 0);-o-transform:matrix(-1, 0, 0, -1, 0, 0);">2</span>, ᘔ, or {{unicode|↊}} (a rotated digit two); ] can be written as <span style="display:inline-block;top:0.5em;transform:matrix(-1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0);-moz-transform: matrix(-1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0);-webkit-transform: matrix(-1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0);-o-transform:matrix(-1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0);">3</span>, Ɛ, or {{unicode|↋}} (a reversed digit three); and twelve is written as 10. For alternative symbols, see ]. | |||

| === Pronunciation === | |||

| According to this notation, duodecimal 50 expresses the same quantity as decimal ] (= five times twelve), duodecimal 60 is equivalent to decimal ] (= six times twelve = half a gross), duodecimal 100 has the same value as decimal ] (= twelve times twelve = one gross), etc. | |||

| The Dozenal Society of America suggested the pronunciation of ten and eleven as "dek" and "el". For the names of powers of twelve, there are two prominent systems. In spite of the efficiency of these newer systems, terms for powers of twelve either already exist or remain easily reconstructed in English using words and affixes. | |||

| ==== Base-12 nomenclature in English ==== | |||

| == Comparison to other numeral systems == | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=November 2024}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Another nominal for ] (12<sub>]</sub>) is a '']'' (10<sub>12</sub> ''or'' 1•10<sup>1</sup><sub>12</sub>). | |||

| The number 12 has six factors, which are ], ], ], ], ], and ], of which 2 and 3 are ]. The decimal system has only four factors, which are ], ], ], and ]; of which 2 and 5 are prime. ] adds two factors to those of ten, namely ] and ], but no additional prime factor. Although twenty has 6 factors, 2 of them prime, similarly to twelve, it is also a much larger base (i.e. the digit set and the multiplication table are much larger). Binary has only two factors, 1 and 2, the latter being prime. Hexadecimal has five factors, adding 4, ] and ] to those of 2, but no additional prime. Trigesimal is the smallest system that has three different prime factors (all of the three smallest primes: 2, 3 and 5) and it has eight factors in total (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 15, and 30). ]—which the ancient ] and ]ns among others actually used—adds the four convenient factors 4, 12, 20, and 60 to this but no new prime factors. The smallest system that has four different prime factors is base 210 and the pattern follows the ]s. In all base systems, there are similarities to the representation of multiples of numbers which are one less than the base.{{Clear}}<!-- the {{-}} template keeps the multiplication table from squeezing the heading for the next section--> | |||

| ] (144<sub>10</sub>) is also known as a ] (100<sub>12</sub> ''or'' 1•10<sup>2</sup><sub>12</sub>). | |||

| ] is (1728<sub>10</sub>) also known as a ''great-gross'' (1,000<sub>12</sub> or 1•10<sup>3</sup><sub>12</sub>). | |||

| For the next ] of twelve that follow those aforementioned, the affixes (dozen-, gross-, great-) are used to produce names for these powers of twelve that have a greater ] value. ]<sub>10</sub> or 10,000<sub>12</sub> may be rendered a ''dozen-great-gross''; so ]<sub>10</sub> or 100,000<sub>12</sub> is a ''gross-great-gross'', with ]<sub>10</sub> or 1,000,000<sub>12</sub> being known as a ''great-great-gross''. | |||

| It should be made plain that the indice's being a multiple of three, e.g. 10<sup>3</sup><sub>12</sub> , 10<sup>6</sup><sub>12</sub> , 10<sup>9</sup><sub>12</sub> results, in these examples, in a ''great gross'', a ''great-great-gross'', and a ''great-great-great-gross'', respectively. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ! Scientific notation||Positional notation||Name||Decimal | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:center"|1•10<sup>0</sup> | |||

| |1 | |||

| |style="text-align:center"|One | |||

| |1 | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:center" |A•10<sup>0</sup> | |||

| |A | |||

| |Ten | |||

| |10 | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:center" |B•10<sup>0</sup> | |||

| |B | |||

| |Eleven | |||

| |11 | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |1•10<sup>1</sup> | |||

| |10 | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |Twelve | |||

| |12 | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |5•10<sup>1</sup> | |||

| |50 | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |Five dozen | |||

| |60 | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |1•10<sup>2</sup> | |||

| |100 | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |One gross | |||

| |144 | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |2;6•10<sup>2</sup> | |||

| |260 | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |Two gross, six dozen | |||

| |360 | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |1•10<sup>3</sup> | |||

| |1,000 | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |One great-gross | |||

| |1,728 | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |1•10<sup>4</sup> | |||

| |10,000 | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |One dozen-great-gross | |||

| |20,736 | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |1•10<sup>5</sup> | |||

| |100,000 | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |One gross-great-gross | |||

| |248,832 | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |1•10<sup>6</sup> | |||

| |1,000,000 | |||

| | style="text-align:center" |One great-great-gross | |||

| |2,985,984 | |||

| |} | |||

| ==== Duodecimal numbers ==== | |||

| In this system, the prefix ''e''- is added for fractions.<ref name="DB01"/><ref name="Zirkel2010">{{cite journal|last=Zirkel|first=Gene|title=How Do You Pronounce Dozenals? | |||

| |journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin|volume=4E |issue=2|date=2010|url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue4b2_0.pdf }}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ! Duodecimal <br> number||Number <br> name||Decimal <br> number||Duodecimal <br> fraction||Fraction <br> name | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1; | |||

| |one | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1 | |||

| |colspan="2"| | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:right" |10; | |||

| |{{abbr|do|pronounced 'doʊ'}} | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|12 | |||

| |0;1||edo | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:right" |100; | |||

| |{{abbr|gro|pronounced 'ɡroʊ'}} | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|144 | |||

| |0;01 | |||

| |egro | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:right" |1,000; | |||

| |{{abbr|mo|pronounced 'moʊ'}} | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1,728 | |||

| |0;001 | |||

| |emo | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:right" |10,000; | |||

| |do-mo | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|20,736 | |||

| |0;000,1 | |||

| |edo-mo | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:right" |100,000; | |||

| |gro-mo | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|248,832 | |||

| |0;000,01 | |||

| |egro-mo | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:right" |1,000,000; | |||

| |bi-mo | |||

| |style="text-align:right" |2,985,984 | |||

| |0;000,001 | |||

| |ebi-mo | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:right" |10,000,000; | |||

| |do-bi-mo | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|35,831,808 | |||

| |0;000,000,1 | |||

| |edo-bi-mo | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:right" |100,000,000; | |||

| |gro-bi-mo | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|429,981,696 | |||

| |0;000,000,01 | |||

| |egro-bi-mo | |||

| |} | |||

| As numbers get larger (or fractions smaller), the last two morphemes are successively replaced with tri-mo, quad-mo, penta-mo, and so on. | |||

| Multiple digits in this series are pronounced differently: 12 is "do two"; 30 is "three do"; 100 is "gro"; {{d3}}{{d2}}9 is "el gro dek do nine"; {{d3}}86 is "el gro eight do six"; 8{{d3}}{{d3}},15{{d2}} is "eight gro el do el, one gro five do dek"; ABA is "dek gro el do dek"; BBB is "el gro el do el"; 0.06 is "six egro"; and so on.<ref name="Zirkel2010"/> | |||

| ==== Systematic Dozenal Nomenclature (SDN) ==== | |||

| This system uses "-qua" ending for the positive powers of 12 and "-cia" ending for the negative powers of 12, and an extension of the IUPAC ]s (with syllables '''dec''' and '''lev''' for the two extra digits needed for duodecimal) to express which power is meant.<ref name="DBX1">{{cite journal |url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue511a_0.pdf |title=Systematic Dozenal Nomenclature and other nomenclature system. |journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin |volume=61 |number=1 }}</ref><ref name="DSAGoodman2016"/> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ! Duodecimal <br> number||Number <br> name||Decimal <br> number||Duodecimal <br> fraction||Fraction <br> name | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1; | |||

| |one | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1 | |||

| |colspan="2"| | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|10; | |||

| |unqua | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|12 | |||

| |0;1 | |||

| |uncia | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|100; | |||

| |biqua | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|144 | |||

| |0;01 | |||

| |bicia | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1,000; | |||

| |triqua | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1,728 | |||

| |0;001 | |||

| |tricia | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|10,000; | |||

| |quadqua | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|20,736 | |||

| |0;000,1 | |||

| |quadcia | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|100,000; | |||

| |pentqua | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|248,832 | |||

| |0;000,01 | |||

| |pentcia | |||

| |- | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|1,000,000; | |||

| |hexqua | |||

| |style="text-align:right"|2,985,984 | |||

| |0;000,001 | |||

| |hexcia | |||

| |} | |||

| After hex-, further prefixes continue sept-, oct-, enn-, dec-, lev-, unnil-, unun-. | |||

| == Advocacy and "dozenalism" == | |||

| ] used 12 as the base for his constructed language ] in 1906, noting it being the smallest number with four factors and its prevalence in commerce.<ref>The Prodigy (Biography of WJS) pg </ref> | |||

| The case for the duodecimal system was put forth at length in ]' 1935 book ''New Numbers: How Acceptance of a Duodecimal Base Would Simplify Mathematics''. Emerson noted that, due to the prevalence of factors of twelve in many traditional units of weight and measure, many of the computational advantages claimed for the metric system could be realized ''either'' by the adoption of ten-based weights and measure ''or'' by the adoption of the duodecimal number system.<ref name="New Numbers 1935"/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Both the Dozenal Society of America and the Dozenal Society of Great Britain promote widespread adoption of the duodecimal system. They use the word "dozenal" instead of "duodecimal" to avoid the more overtly decimal terminology. However, the etymology of "dozenal" itself is also an expression based on decimal terminology since "dozen" is a direct derivation of the French word ''douzaine'', which is a derivative of the French word for twelve, '']'', descended from Latin ''duodecim''. | |||

| Mathematician and mental calculator ] was an outspoken advocate of duodecimal: | |||

| {{blockquote|text=The duodecimal tables are easy to master, easier than the decimal ones; and in elementary teaching they would be so much more interesting, since young children would find more fascinating things to do with twelve rods or blocks than with ten. Anyone having these tables at command will do these calculations more than one-and-a-half times as fast in the duodecimal scale as in the decimal. This is my experience; I am certain that even more so it would be the experience of others.|author=A. C. Aitken|source="Twelves and Tens" in ''The Listener'' (January 25, 1962)<ref>A. C. Aitken (January 25, 1962) ''The Listener''.</ref>}} | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=But the final quantitative advantage, in my own experience, is this: in varied and extensive calculations of an ordinary and not unduly complicated kind, carried out over many years, I come to the conclusion that the efficiency of the decimal system might be rated at about 65 or less, if we assign 100 to the duodecimal.|author=A. C. Aitken|source=''The Case Against Decimalisation'' (1962)<ref>A. C. Aitken (1962) . Edinburgh / London: Oliver & Boyd.</ref>}} | |||

| === In media === | |||

| In "Little Twelvetoes," an episode of the American educational television series '']'', a farmer encounters an alien being with twelve fingers on each hand and twelve toes on each foot who uses duodecimal arithmetic. The alien uses "dek" and "el" as names for ten and eleven, and Andrews' script-X and script-E for the digit symbols.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.schoolhouserock.tv/Little.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100206052053/http://www.schoolhouserock.tv/Little.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=6 February 2010|title=SchoolhouseRock - Little Twelvetoes|date=6 February 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Bellos|first=Alex|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FA_HwoEzSQUC|title=Alex's Adventures in Numberland|date=2011-04-04|publisher=A&C Black|isbn=978-1-4088-0959-4|pages=50|language=en|author-link=Alex Bellos}}</ref> | |||

| === Duodecimal systems of measurements === | |||

| ] proposed by dozenalists include: | |||

| * Tom Pendlebury's TGM system<ref>{{cite web|last1=Pendlebury|first1=Tom|last2=Goodman|first2=Donald|title=TGM: A Coherent Dozenal Metrology|url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/tgm_0.pdf |date=2012|publisher=The Dozenal Society of Great Britain}}</ref><ref name="DSAGoodman2016">{{cite web |last=Goodman |first=Donald |title=Manual of the Dozenal System |date=2016 |url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DSA_mods_rev.pdf |publisher=Dozenal Society of America|access-date=27 April 2018}}</ref> | |||

| * Takashi Suga's Universal Unit System<ref>{{cite web|last=Suga|first=Takashi|title=Proposal for the Universal Unit System|url=http://www.asahi-net.or.jp/~dd6t-sg/univunit-e/revised.pdf |date=22 May 2019}}</ref><ref name="DSAGoodman2016" /> | |||

| * John Volan's Primel system<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Volan |first1=John |date= |title=The Primel Metrology |url=http://www.dozenal.org/drupal/sites_bck/default/files/DuodecimalBulletinIssue531.pdf |journal=The Duodecimal Bulletin |volume=63 |issue=1 |pages=38–60<!--be careful; the Duodecimal Bulletin, as one might expect, numbers its pages in duodecimal--> }}</ref> | |||

| == Comparison to other number systems == | |||

| :''In this section, numerals are in decimal. For example, "10" means 9+1, and "12" means 9+3.'' | |||

| The Dozenal Society of America argues that if a base is too small, significantly longer expansions are needed for numbers; if a base is too large, one must memorise a large multiplication table to perform arithmetic. Thus, it presumes that "a number base will need to be between about 7 or 8 through about 16, possibly including 18 and 20".<ref name="dsafaq" /> | |||

| The number 12 has six factors, which are ], ], ], ], ], and ], of which 2 and 3 are ]. It is the smallest number to have six factors, the largest number to have at least half of the numbers below it as divisors, and is only slightly larger than 10. (The numbers 18 and 20 also have six factors but are much larger.) Ten, in contrast, only has four factors, which are ], ], ], and ], of which 2 and 5 are prime.<ref name="dsafaq" /> Six shares the prime factors 2 and 3 with twelve; however, like ten, six only has four factors (1, 2, 3, and 6) instead of six. Its corresponding base, ], is below the DSA's stated threshold. | |||

| ] and ] only have 2 as a prime factor. Therefore, in ] and ], the only ] are those whose ] is a ]. | |||

| ] is the smallest number that has three different prime factors (2, 3, and 5, the first three primes), and it has eight factors in total (1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 15, and 30). ] was actually used by the ancient ]ians and ]ns, among others; its base, ], adds the four convenient factors 4, 12, 20, and 60 to 30 but no new prime factors. The smallest number that has four different prime factors is ]; the pattern follows the ]s. However, these numbers are quite large to use as bases, and are far beyond the DSA's stated threshold. | |||

| In all base systems, there are similarities to the representation of multiples of numbers that are one less than or one more than the base.{{Clear}}''In the following multiplication table, numerals are written in duodecimal. For example, "10" means twelve, and "12" means fourteen.''<!-- the {{-}} template keeps the multiplication table from squeezing the heading for the next section--> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: right;" | |||

| |+ Duodecimal multiplication table | |||

| !style="width:7.69%"|× | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|1 | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|2 | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|3 | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|4 | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|5 | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|6 | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|7 | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|8 | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|9 | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|{{d2}} | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|{{d3}} | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|10 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right; width:7.69%"|1 | |||

| |1||2||3||4||5||6||7||8||9||{{d2}}||{{d3}}||10 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|2 | |||

| |2||4||6||8||{{d2}}||10||12||14||16||18||1{{d2}}||20 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;|3 | |||

| |3||6||9||10||13||16||19||20||23||26||29||30 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|4 | |||

| |4||8||10||14||18||20||24||28||30||34||38||40 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|5 | |||

| |5||{{d2}}||13||18||21||26||2{{d3}}||34||39||42||47||50 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|6 | |||

| |6||10||16||20||26||30||36||40||46||50||56||60 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|7 | |||

| |7||12||19||24||2{{d3}}||36||41||48||53||5{{d2}}||65||70 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|8 | |||

| |8||14||20||28||34||40||48||54||60||68||74||80 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|9 | |||

| |9||16||23||30||39||46||53||60||69||76||83||90 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|{{d2}} | |||

| |{{d2}}||18||26||34||42||50||5{{d2}}||68||76||84||92||A0 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|{{d3}} | |||

| |{{d3}}||1{{d2}}||29||38||47||56||65||74||83||92||{{d2}}1||B0 | |||

| |- | |||

| !style="text-align: right;"|10 | |||

| |10||20||30||40||50||60||70||80||90||A0||B0||100 | |||

| |} | |||

| == Conversion tables to and from decimal == | == Conversion tables to and from decimal == | ||

| To convert numbers between bases, one can use the general conversion algorithm (see the relevant section under ]). Alternatively, one can use digit-conversion tables. The ones provided below can be used to convert any duodecimal number between 0 |

To convert numbers between bases, one can use the general conversion algorithm (see the relevant section under ]). Alternatively, one can use digit-conversion tables. The ones provided below can be used to convert any duodecimal number between 0;1 and {{d3}}{{d3}},{{d3}}{{d3}}{{d3}};{{d3}} to decimal, or any decimal number between 0.1 and 99,999.9 to duodecimal. To use them, the given number must first be decomposed into a sum of numbers with only one significant digit each. For example: | ||

| :12,345.6 = 10,000 + 2,000 + 300 + 40 + 5 + 0.6 | |||

| This decomposition works the same no matter what base the number is expressed in. Just isolate each non-zero digit, padding them with as many zeros as necessary to preserve their respective place values. If the digits in the given number include zeroes (for example, |

This decomposition works the same no matter what base the number is expressed in. Just isolate each non-zero digit, padding them with as many zeros as necessary to preserve their respective place values. If the digits in the given number include zeroes (for example, 7,080.9), these are left out in the digit decomposition (7,080.9 = 7,000 + 80 + 0.9). Then, the digit conversion tables can be used to obtain the equivalent value in the target base for each digit. If the given number is in duodecimal and the target base is decimal, we get: | ||

| <small>(duodecimal)</small> |

:<small>(duodecimal)</small> 10,000 + 2,000 + 300 + 40 + 5 + 0;6 <br> = <small>(decimal)</small> 20,736 + 3,456 + 432 + 48 + 5 + 0.5 | ||

| Because the summands are already converted to decimal, the usual decimal arithmetic is used to perform the addition and recompose the number, arriving at the conversion result: | |||

| Duodecimal |

Duodecimal ---> Decimal | ||

| |

10,000 = 20,736 | ||

| |

2,000 = 3,456 | ||

| |

300 = 432 | ||

| |

40 = 48 | ||

| |

5 = 5 | ||

| + |

+ 0;6 = + 0.5 | ||

| ----------------------------- | |||

| 0.7 = 0.58{{overline|3}}333333333... | |||

| 12,345;6 = 24,677.5 | |||

| 0.08 = 0.0{{overline|5}}5555555555... | |||

| -------------------------------------------- | |||

| 123,456.78 = 296,130.63{{overline|8}}888888888... | |||

| That is, <small>(duodecimal)</small> |

That is, <small>(duodecimal)</small> 12,345;6 equals <small>(decimal)</small> 24,677.5 | ||

| If the given number is in decimal and the target base is duodecimal, the method is |

If the given number is in decimal and the target base is duodecimal, the method is same. Using the digit conversion tables: | ||

| <small>(decimal)</small> |

<small>(decimal)</small> 10,000 + 2,000 + 300 + 40 + 5 + 0.6 <br> = <small>(duodecimal)</small> 5,954 + 1,1{{d2}}8 + 210 + 34 + 5 + 0;{{overline|7249}} | ||

| To sum these partial products and recompose the number, the addition must be done with duodecimal rather than decimal arithmetic: | |||

| However, in order to do this sum and recompose the number, now the addition tables for the duodecimal system have to be used, instead of the addition tables for decimal most people are already familiar with, because the summands are now in base twelve and so the arithmetic with them has to be in duodecimal as well. In decimal, 6 + 6 equals 12, but in duodecimal it equals 10; so, if using decimal arithmetic with duodecimal numbers one would arrive at an incorrect result. Doing the arithmetic properly in duodecimal, one gets the result: | |||

| Decimal |

Decimal --> Duodecimal | ||

| |

10,000 = 5,954 | ||

| |

2,000 = 1,1{{d2}}8 | ||

| |

300 = 210 | ||

| |

40 = 34 | ||

| |

5 = 5 | ||

| + |

+ 0.6 = + 0;{{overline|7249}} | ||

| ------------------------------- | |||

| 0.7 = 0.8{{overline|4972}}4972497249724972497... | |||

| |

12,345.6 = 7,189;{{overline|7249}} | ||

| -------------------------------------------------------- | |||

| 123,456.78 = 5Ɛ,540.9{{overline|43ᘔ0Ɛ62ᘔ68781Ɛ059153}}43ᘔ... | |||

| That is, <small>(decimal)</small> |

That is, <small>(decimal)</small> 12,345.6 equals <small>(duodecimal)</small> 7,189;{{overline|7249}} | ||

| === Duodecimal to decimal digit conversion === | === Duodecimal to decimal digit conversion === | ||

| {|class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| ! Duod. | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Duod.''''' | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | ''Dec.'' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Duod.''''' | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | ''Dec.'' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Duod.''''' | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | ''Dec.'' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Duod.''''' | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | ''Dec.'' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Duod.''''' | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | ''Dec.'' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Duod.''''' | |||

| |- style="text-align:right" | |||

| | ''Dec.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Duod.''''' | |||

| | ''Dec.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Duod.''''' | |||

| | ''Dec.'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''100,000''' | |||

| | 248,832 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''10,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''10,000''' | ||

| | 20,736 | | 20,736 | ||

| Line 198: | Line 525: | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''1''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''1''' | ||

| | 1 | | 1 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;1''' | ||

| | 0.08{{overline|3}} | | style="text-align:left" | 0.08{{overline|3}} | ||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | 0.0069{{overline|4}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''200,000''' | |||

| | 497,664 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''20,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''20,000''' | ||

| | 41,472 | | 41,472 | ||

| Line 215: | Line 538: | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''2''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''2''' | ||

| | 2 | | 2 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;2''' | ||

| | 0.1{{overline|6}} | | style="text-align:left" | 0.1{{overline|6}} | ||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | 0.013{{overline|8}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''300,000''' | |||

| | 746,496 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''30,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''30,000''' | ||

| | 62,208 | | 62,208 | ||

| Line 232: | Line 551: | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''3''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''3''' | ||

| | 3 | | 3 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;3''' | ||

| | style="text-align:left" | 0.25 | |||

| | 0.25 | |||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | 0.0208{{overline|3}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''400,000''' | |||

| | 995,328 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''40,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''40,000''' | ||

| | 82,944 | | 82,944 | ||

| Line 249: | Line 564: | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''4''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''4''' | ||

| | 4 | | 4 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;4''' | ||

| | 0.{{overline|3}} | | style="text-align:left" | 0.{{overline|3}} | ||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | 0.02{{overline|7}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''500,000''' | |||

| | 1,244,160 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''50,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''50,000''' | ||

| | 103,680 | | 103,680 | ||

| Line 266: | Line 577: | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''5''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''5''' | ||

| | 5 | | 5 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;5''' | ||

| | 0.41{{overline|6}} | | style="text-align:left" | 0.41{{overline|6}} | ||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | 0.0347{{overline|2}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''600,000''' | |||

| | 1,492,992 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''60,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''60,000''' | ||

| | 124,416 | | 124,416 | ||

| Line 283: | Line 590: | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''6''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''6''' | ||

| | 6 | | 6 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;6''' | ||

| | style="text-align:left" | 0.5 | |||

| | 0.5 | |||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | 0.041{{overline|6}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''700,000''' | |||

| | 1,741,824 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''70,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''70,000''' | ||

| | 145,152 | | 145,152 | ||

| Line 295: | Line 598: | ||

| | 12,096 | | 12,096 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''700''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''700''' | ||

| | |

| 1,008 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''70''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''70''' | ||

| | 84 | | 84 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''7''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''7''' | ||

| | 7 | | 7 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;7''' | ||

| | 0.58{{overline|3}} | | style="text-align:left" | 0.58{{overline|3}} | ||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | 0.0486{{overline|1}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''800,000''' | |||

| | 1,990,656 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''80,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''80,000''' | ||

| | 165,888 | | 165,888 | ||

| Line 312: | Line 611: | ||

| | 13,824 | | 13,824 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''800''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''800''' | ||

| | |

| 1,152 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''80''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''80''' | ||

| | 96 | | 96 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''8''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''8''' | ||

| | 8 | | 8 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;8''' | ||

| | 0.{{overline|6}} | | style="text-align:left" | 0.{{overline|6}} | ||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | 0.0{{overline|5}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''900,000''' | |||

| | 2,239,488 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''90,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''90,000''' | ||

| | 186,624 | | 186,624 | ||

| Line 334: | Line 629: | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''9''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''9''' | ||

| | 9 | | 9 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;9''' | ||

| | style="text-align:left" | 0.75 | |||

| | 0.75 | |||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''{{nowrap|{{d2}}0,000}}''' | |||

| | 0.0625 | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''ᘔ00,000''' | |||

| | 2,488,320 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''ᘔ0,000''' | |||

| | 207,360 | | 207,360 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| ''' |

| style="background:silver;"| '''{{d2}},000''' | ||

| | 17,280 | | 17,280 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| ''' |

| style="background:silver;"| '''{{d2}}00''' | ||

| | 1,440 | | 1,440 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| ''' |

| style="background:silver;"| '''{{d2}}0''' | ||

| | 120 | | 120 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| ''' |

| style="background:silver;"| '''{{d2}}''' | ||

| | 10 | | 10 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;{{d2}}''' | ||

| | 0.8{{overline|3}} | | style="text-align:left" | 0.8{{overline|3}} | ||

| | style=" |

|- style="text-align:right" | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''{{d3}}0,000''' | |||

| | 0.069{{overline|4}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''Ɛ00,000''' | |||

| | 2,737,152 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''Ɛ0,000''' | |||

| | 228,096 | | 228,096 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| ''' |

| style="background:silver;"| '''{{d3}},000''' | ||

| | 19,008 | | 19,008 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| ''' |

| style="background:silver;"| '''{{d3}}00''' | ||

| | 1,584 | | 1,584 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| ''' |

| style="background:silver;"| '''{{d3}}0''' | ||

| | 132 | | 132 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| ''' |

| style="background:silver;"| '''{{d3}}''' | ||

| | 11 | | 11 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0 |

| style="background:silver;"| '''0;{{d3}}''' | ||

| | 0.91{{overline|6}} | | style="text-align:left" | 0.91{{overline|6}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.0Ɛ''' | |||

| | 0.0763{{overline|8}} | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| === Decimal to duodecimal digit conversion === | === Decimal to duodecimal digit conversion === | ||

| {|class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| ! Dec. | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| ! Duod. | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| ! Dec. | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| ! Duodecimal | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''100,000''' | |||

| | 49,ᘔ54 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''10,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''10,000''' | ||

| | 5,954 | | 5,954 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''1,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''1,000''' | ||

| | 6{{d3}}4 | |||

| | 6Ɛ4 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''100''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''100''' | ||

| | 84 | | 84 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''10''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''10''' | ||

| | |

| {{d2}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''1''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''1''' | ||

| | 1 | | 1 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.1''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''0.1''' | ||

| | 0 |

| 0;1{{overline|2497}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.01''' | |||

| | 0.0{{overline|15343ᘔ0Ɛ62ᘔ68781Ɛ059}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''200,000''' | |||

| | 97,8ᘔ8 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''20,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''20,000''' | ||

| | {{d3}},6{{d2}}8 | |||

| | Ɛ,6ᘔ8 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''2,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''2,000''' | ||

| | 1, |

| 1,1{{d2}}8 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''200''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''200''' | ||

| | 148 | | 148 | ||

| Line 424: | Line 698: | ||

| | 2 | | 2 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.2''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''0.2''' | ||

| | 0 |

| 0;{{overline|2497}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.02''' | |||

| | 0.0{{overline|2ᘔ68781Ɛ05915343ᘔ0Ɛ6}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''300,000''' | |||

| | 125,740 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''30,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''30,000''' | ||

| | 15,440 | | 15,440 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''3,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''3,000''' | ||

| | 1, |

| 1,8{{d2}}0 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''300''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''300''' | ||

| | 210 | | 210 | ||

| Line 441: | Line 711: | ||

| | 3 | | 3 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.3''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''0.3''' | ||

| | 0 |

| 0;3{{overline|7249}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.03''' | |||

| | 0.0{{overline|43ᘔ0Ɛ62ᘔ68781Ɛ059153}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''400,000''' | |||

| | 173,594 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''40,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''40,000''' | ||

| | |

| 1{{d3}},194 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''4,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''4,000''' | ||

| | 2,394 | | 2,394 | ||

| Line 458: | Line 724: | ||

| | 4 | | 4 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.4''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''0.4''' | ||

| | 0 |

| 0;{{overline|4972}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.04''' | |||

| | 0.{{overline|05915343ᘔ0Ɛ62ᘔ68781Ɛ}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''500,000''' | |||

| | 201,428 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''50,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''50,000''' | ||

| | 24, |

| 24,{{d3}}28 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''5,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''5,000''' | ||

| | 2, |

| 2,{{d2}}88 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''500''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''500''' | ||

| | 358 | | 358 | ||

| Line 475: | Line 737: | ||

| | 5 | | 5 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.5''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''0.5''' | ||

| | 0 |

| 0;6 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.05''' | |||

| | 0.0{{overline|7249}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''600,000''' | |||

| | 24Ɛ,280 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''60,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''60,000''' | ||

| | |

| 2{{d2}},880 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''6,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''6,000''' | ||

| | 3,580 | | 3,580 | ||

| Line 492: | Line 750: | ||

| | 6 | | 6 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.6''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''0.6''' | ||

| | 0 |

| 0;{{overline|7249}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.06''' | |||

| | 0.0{{overline|8781Ɛ05915343ᘔ0Ɛ62ᘔ6}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''700,000''' | |||

| | 299,114 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''70,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''70,000''' | ||

| | 34,614 | | 34,614 | ||

| Line 503: | Line 757: | ||

| | 4,074 | | 4,074 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''700''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''700''' | ||

| | 4{{d2}}4 | |||

| | 4ᘔ4 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''70''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''70''' | ||

| | |

| 5{{d2}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''7''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''7''' | ||

| | 7 | | 7 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.7''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''0.7''' | ||

| | 0 |

| 0;8{{overline|4972}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.07''' | |||

| | 0.0{{overline|ᘔ0Ɛ62ᘔ68781Ɛ05915343}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''800,000''' | |||

| | 326,Ɛ68 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''80,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''80,000''' | ||

| | |

| 3{{d2}},368 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''8,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''8,000''' | ||

| | 4,768 | | 4,768 | ||

| Line 526: | Line 776: | ||

| | 8 | | 8 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.8''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''0.8''' | ||

| | 0 |

| 0;{{overline|9724}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.08''' | |||

| | 0.{{overline|0Ɛ62ᘔ68781Ɛ05915343ᘔ}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''900,000''' | |||

| | 374,ᘔ00 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''90,000''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''90,000''' | ||

| | 44,100 | | 44,100 | ||

| Line 543: | Line 789: | ||

| | 9 | | 9 | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.9''' | | style="background:silver;"| '''0.9''' | ||

| | 0 |

| 0;{{d2}}{{overline|9724}} | ||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.09''' | |||

| | 0.1{{overline|0Ɛ62ᘔ68781Ɛ05915343ᘔ}} | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| == Fractions and irrational numbers == | |||

| === Conversion of powers === | |||

| === Fractions === | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| Duodecimal ] for rational numbers with ] denominators terminate: | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{sfrac|2}} = 0;6 | |||

| | rowspan="2" | ''Exponent'' | |||

| * {{sfrac|3}} = 0;4 | |||

| | colspan="2" | b=2 | |||

| * {{sfrac|4}} = 0;3 | |||

| | colspan="2" | b=3 | |||

| * {{sfrac|6}} = 0;2 | |||

| | colspan="2" | b=4 | |||

| * {{sfrac|8}} = 0;16 | |||

| | colspan="2" | b=5 | |||

| * {{sfrac|9}} = 0;14 | |||

| | colspan="2" | b=6 | |||

| * {{sfrac|10}} = 0;1 (this is one twelfth, {{sfrac|{{d2}}}} is one tenth) | |||

| | colspan="2" | b=7 | |||

| * {{sfrac|14}} = 0;09 (this is one sixteenth, {{sfrac|12}} is one fourteenth) | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>6</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''64''' | |||

| | 54 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''729''' | |||

| | 509 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''4,096''' | |||

| | 2454 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''15,625''' | |||

| | 9,061 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''46,656''' | |||

| | 23,000 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''117,649''' | |||

| | 58,101 | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>5</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''32''' | |||

| | 28 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''243''' | |||

| | 183 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''1,024''' | |||

| | 714 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''3,125''' | |||

| | 1,985 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''7,776''' | |||

| | 4,600 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''16,807''' | |||

| | 9,887 | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>4</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''16''' | |||

| | 14 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''81''' | |||

| | 69 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''256''' | |||

| | 194 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''625''' | |||

| | 441 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''1,296''' | |||

| | 900 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''2,401''' | |||

| | 1,481 | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>3</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''8''' | |||

| | 8 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''27''' | |||

| | 23 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''64''' | |||

| | 54 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''125''' | |||

| | ᘔ5 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''216''' | |||

| | 160 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''343''' | |||

| | 247 | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>2</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''4''' | |||

| | 4 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''9''' | |||

| | 9 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''16''' | |||

| | 14 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''25''' | |||

| | 21 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''36''' | |||

| | 30 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''49''' | |||

| | 41 | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>1</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''2''' | |||

| | 2 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''3''' | |||

| | 3 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''4''' | |||

| | 4 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''5''' | |||

| | 5 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''6''' | |||

| | 6 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''7''' | |||

| | 7 | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>−1</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.5''' | |||

| | 0.6 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.{{overline|3}}''' | |||

| | 0.4 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.25''' | |||

| | 0.3 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.2''' | |||

| | 0.{{overline|2497}} | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.1{{overline|6}}''' | |||

| | 0.2 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.{{overline|142857}}''' | |||

| | 0.{{overline|186ᘔ35}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>−2</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.25''' | |||

| | 0.3 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.{{overline|1}}''' | |||

| | 0.14 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.0625''' | |||

| | 0.09 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.04''' | |||

| | 0.{{overline|05915343ᘔ0<br>Ɛ62ᘔ68781Ɛ}} | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.02{{overline|7}}''' | |||

| | 0.04 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''0.{{overline|0204081632653<br>06122448979591<br>836734693877551}}''' | |||

| | 0.{{overline|02Ɛ322547ᘔ05ᘔ<br>644ᘔ9380Ɛ908996<br>741Ɛ615771283Ɛ}} | |||

| |} | |||

| while other rational numbers have ] duodecimal fractions: | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| * {{sfrac|5}} = 0;{{Overline|2497}} | |||

| |- | |||

| * {{sfrac|7}} = 0;{{Overline|186{{D2}}35}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" | ''Exponent'' | |||

| * {{sfrac|{{d2}}}} = 0;1{{Overline|2497}} (one tenth) | |||

| | colspan="2" | b=8 | |||

| * {{sfrac|{{d3}}}} = 0;{{Overline|1}} (one eleventh) | |||

| | colspan="2" | b=9 | |||

| * {{sfrac|11}} = 0;{{Overline|0{{D3}}}} (one thirteenth) | |||

| | colspan="2" | '''b=10''' | |||

| * {{sfrac|12}} = 0;0{{Overline|{{D2}}35186}} (one fourteenth) | |||

| | colspan="2" | b=11 | |||

| * {{sfrac|13}} = 0;0{{Overline|9724}} (one fifteenth) | |||

| | colspan="2" | '''b=12''' | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''''Dec.''''' | |||

| | ''Duod.'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>6</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''262,144''' | |||

| | 107,854 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''531,441''' | |||

| | 217,669 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''1,000,000''' | |||

| | 402,854 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''1,771,561''' | |||

| | 715,261 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''2,985,984''' | |||

| | 1,000,000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>5</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''32,768''' | |||

| | 16,Ɛ68 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''59,049''' | |||

| | 2ᘔ,209 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''100,000''' | |||

| | 49,ᘔ54 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''161,051''' | |||

| | 79,24Ɛ | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''248,832''' | |||

| | 100,000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>4</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''4,096''' | |||

| | 2,454 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''6,561''' | |||

| | 3,969 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''10,000''' | |||

| | 5,954 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''14,641''' | |||

| | 8,581 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''20,736''' | |||

| | 10,000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | b<sup>3</sup> | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''512''' | |||

| | 368 | |||

| | style="background:silver;"| '''729''' | |||

| | 509 | |||