| Revision as of 20:51, 25 August 2006 editHanuman Das (talk | contribs)5,424 edits →Hermetic beliefs: remove info from Hall, who is not a reliable source← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:50, 17 December 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,407,324 edits Added pmid. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Hermeticism | #UCB_Category 36/50 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Philosophy based on the teachings of Hermes Trismegistus}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2023}} | |||

| {{About|the philosophy based on Hermetic writings|the writings themselves|Hermetica|other uses|Hermetic (disambiguation){{!}}Hermetic}} | |||

| {{Hermeticism|expand=Hermetic writings}} | |||

| '''Hermeticism''', or '''Hermetism''', is a philosophical and religious tradition rooted in the teachings attributed to ], a ] figure combining elements of the Greek god ] and the Egyptian god ].{{efn|A survey of the literary and archaeological evidence for the background of Hermes Trismegistus in the Greek Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth may be found in {{harvnb|Bull|2018|pp=33–96}}.}} This system encompasses a wide range of ] knowledge, including aspects of ], ], and ], and has significantly influenced various ] and ] traditions throughout history. The writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, often referred to as the '']'', were produced over a period spanning many centuries ({{circa|300 BCE – 1200 CE}}) and may be very different in content and scope.{{efn|The oldest texts attributed to Hermes are astrological texts (belonging to the ]) which may go back as far as to the second or third century BCE; see {{harvnb|Copenhaver|1992|p=xxxiii}}; {{harvnb|Bull|2018|pp=2–3}}. Garth Fowden is somewhat more cautious, noting that our earliest testimonies date to the first century BCE (see {{harvnb|Fowden|1986|p=3, note 11}}). On the other end of the chronological spectrum, the ''Kitāb fi zajr al-nafs'' ("The Book of the Rebuke of the Soul") is commonly thought to date from the twelfth century; see {{harvnb|Van Bladel|2009|p=226}}.}} | |||

| ] in a medieval rendering.]] | |||

| One particular form of Hermetic teaching is the religio-philosophical system found in a specific subgroup of Hermetic writings known as the ]. The most famous of these are the '']'', a collection of seventeen ] treatises written between approximately 100 and 300 CE, and the '']'', a treatise from the same period, mainly surviving in a ] translation.{{efn|On the dating of the 'philosophical' ''Hermetica'', see {{harvnb|Copenhaver|1992|p=xliv}}; {{harvnb|Bull|2018|p=32}}. The sole exception to the general dating of c. 100–300 CE is ], which may date to the first century CE (see {{harvnb|Bull|2018|p=9}}, referring to {{harvnb|Mahé|1978–1982|loc=vol. II, p. 278}}; cf. {{harvnb|Mahé|1999|p=101}}). Earlier dates have been suggested, most notably by ] (500–200 BCE) and Bruno H. Stricker (c. 300 BCE), but these suggestions have been rejected by most other scholars (see {{harvnb|Bull|2018|p=6, note 23}}). On the ''Asclepius'', see {{harvnb|Copenhaver|1992|loc=pp. xliii–xliv, xlvii}}.}} This specific historical form of Hermetic philosophy is sometimes more narrowly referred to as Hermetism,{{efn|This is a convention established by such scholars as {{harvnb|Van Bladel|2009|pp=17–22}}; {{harvnb|Hanegraaff|2015|pp=180–183}}; {{harvnb|Bull|2018|pp=27–30}}. Other authors (especially, though not exclusively, earlier authors) may use the terms 'Hermetism' and 'Hermeticism' synonymously, more loosely referring to any philosophical system drawing on Hermetic writings.}} to distinguish it from other philosophies inspired by Hermetic writings of different periods and natures. | |||

| '''Hermeticism''' is a set of ] and ] beliefs<ref>(Churton p. 5)</ref> based primarily upon the writings attributed to ]. These beliefs have had the impact of effecting ] and further, the impact of serving as a set of ] beliefs. Whatever the impact of the beliefs, they stem from teachings and books accredited to ], who is put forth as a wise sage and ] ], commonly seen as synonymous with the Egyptian god ].{{citation needed}} | |||

| The broader term, Hermeticism, may refer to a wide variety of philosophical systems drawing on Hermetic writings or other subject matter associated with Hermes. Notably, alchemy often went by the name of "the Hermetic art" or "the Hermetic philosophy".{{sfn|Ebeling|2007|pp=103–108}} The most famous use of the term in this broader sense is in the concept of ] Hermeticism, which refers to the ] philosophies inspired by the translations of the ''Corpus Hermeticum'' by ] (1433–1499) and ] (1447–1500), as well as by ]' (1494–1541) introduction of a new medical philosophy drawing upon the ], such as the '']''.{{sfn|Ebeling|2007|pp=59–90}} | |||

| In Islam, the Hermetic cult was accepted as being the ] mentioned in the Qu'ran in ] CE.<ref>(Churton pp. 26-7)</ref> | |||

| Throughout its history, Hermeticism was closely associated with the idea of a primeval, divine wisdom revealed only to the most ancient of sages, such as Hermes Trismegistus.{{efn|Among medieval Muslims, Hermes was regarded as a "prophet of science" (see {{harvnb|Van Bladel|2009}}). For Hermes' status as an ancient sage among medieval Latin philosophers like ] or ], see {{harvnb|Marenbon|2015|pp=74–76, 130–131}}. The ancient wisdom narrative as such goes back to the Hellenistic period; see {{harvnb|Droge|1989}}; {{harvnb|Pilhofer|1990}}; {{harvnb|Boys-Stones|2001}}; {{harvnb|Van Nuffelen|2011}}.}} During the Renaissance, this evolved into the concept of ''] ''or "ancient theology", which asserted that a single, true theology was given by God to the earliest humans and that traces of it could still be found in various ancient systems of thought.{{sfn|Walker|1972}} This idea, popular among Renaissance thinkers like ] (1463–1494), eventually developed into the notion that divine truth could be found across different religious and philosophical traditions, a concept that came to be known as the ].{{sfn|Hanegraaff|2012|pp=7–12}} In this context, the term 'Hermetic' gradually lost its specificity, eventually becoming synonymous with the divine knowledge of the ]ians, particularly as related to alchemy and ], a view that was later popularized by nineteenth- and twentieth-century occultists.{{sfnm|1a1=Prophet|1y=2018|2a1=Horowitz|2y=2019|2pp=193–198}} | |||

| == History == | |||

| ==Origins and early development== | |||

| === The Corpus Hermeticum === | |||

| ===Late Antiquity=== | |||

| After centuries of falling out of favor, as did all pagan religions, Hermeticism was reintroduced to the West when, in 1460 CE, a man named Leonardo brought the ] to ]. He was one of many agents sent out by Pistoia's ruler, ], to scour European monasteries for lost ancient writings. <ref>(''The Way of Hermes'', p. 9)<br></ref> | |||

| {{Further|Hellenistic religion|Decline of Hellenistic polytheism}} | |||

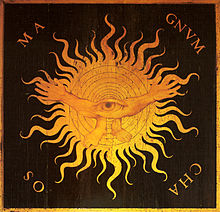

| ] is a symbol of Hermeticism.]] | |||

| In ], Hermetism{{efn|{{harvnb|Van den Broek|Hanegraaff|1998}} distinguish ''Hermetism'' in late antiquity from ''Hermeticism'' in the Renaissance revival.}} originated in the cultural and religious melting pot of ], a period marked by the fusion of Greek, Egyptian, and other Near Eastern religious and philosophical traditions. The central figure of ], who embodies both the Greek god ] and the Egyptian god ], emerged as a symbol of this ]. Hermes Trismegistus was revered as a divine sage and is credited with a vast corpus of writings known as the '']'', which expound on various aspects of theology, cosmology, and spiritual practice.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992}} | |||

| Believed originally to predate ] and ], much of the fascination with Hermeticism disappeared with the analysis in 1614 CE by ], a ] ]. Casaubon analyzed the Hermetic texts for linguistic style and concluded that they were written after the start of the Christian Era. <ref>(''The Way of Hermes'', p. 9)<br></ref> Other scholars analyzing the Greek texts for linguistics came to similar conclusions. Walter Scott places their date shortly after 200 ], while Sir W. Flinders Petrie places them between 200 and 500 BCE. <ref>(Abel and Hare p. 7)<br></ref> Plutarch's mention of Hermes Trismegistus dates back to the first century CE (1-100 CE) suggesting that Scott dated the work after its true date. <ref>(Hoeller)<br></ref> | |||

| Hermetism developed alongside other significant religious and philosophical movements such as early Christianity, Gnosticism, ], the ], and late ] and ] literature. These doctrines were "characterized by a resistance to the dominance of either pure rationality or doctrinal faith."{{sfn|Van den Broek|Hanegraaff|1998|p=vii}} ]'s mention of Hermes Trismegistus dates back to the first century CE, indicating the early recognition of this figure in Greek and Roman thought. Other significant figures of the time, such as ], ], and ], were also familiar with Hermetic writings, which influenced their own philosophical and religious ideas.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992|3a1=Hoeller|3y=1996}} | |||

| However, ], uses different reasoning. Budge, in discussing the Egyptian text, '']'', clearly stated that the earliest version of ''The Book of the Dead'' found was not necessarily the earliest version that existed. Budge argued that one cannot claim that an earlier version does not exist simply because it has not been found. <ref>(Budge p. xiii)<br></ref> Budge maintains that ''The Book of the Dead'' itself was drastically rewritten, reorganized, and amended several times in Egypt, creating four distinct versions which have been found. These versions stretch over a millennium, from the ] (2498 BCE - 2345 BCE) to the ] (1186 BCE - 1073 BCE). <ref>(Budge pp. ix-x)<br></ref> | |||

| The texts now known as the '']'' are generally dated by modern scholars to the beginning of the second century or earlier. These writings focus on the oneness and goodness of God, the purification of the soul, and the relationship between mind and spirit. Their predominant literary form is the ], where Hermes Trismegistus instructs a perplexed disciple on various teachings of hidden wisdom.{{sfnm|1a1=Copenhaver|1y=1992|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| In 1945 CE, Hermetic writings were among those found near ], in the form of one of the conversations between Hermes and ] from the Corpus Hermeticum, and a text about the Hermetic mystery schools, ''On the Ogdoad and Ennead'', written in the ], the last form of the Egyptian writing style. <ref>(''Way of Hermes'', pp. 9-10)<br></ref> | |||

| In fifth-century ], ] compiled an extensive ''Anthology'' of Greek poetical, rhetorical, historical, and philosophical literature. Among the preserved excerpts are significant numbers of discourses and dialogues attributed to Hermes Trismegistus.<ref>{{harvnb|Copenhaver|1992}}; English translation in {{harvnb|Litwa|2018|pp=27–159}}.</ref> | |||

| The concepts discussed within the Corpus Hermeticum, even if the Coptic book was from the earliest version, are distinctly ancient Egyptian. This includes the concept, "All is one, all is from the One". <ref>(''Way of Hermes'', p. 10)<br></ref> | |||

| ===Influence on Early Christianity and Gnosticism=== | |||

| == Hermeticism as a religion == | |||

| Hermeticism had a significant impact on ] thought, particularly in the development of ] and esoteric interpretations of scripture. Some early ], such as ], viewed Hermes Trismegistus as a wise pagan prophet whose teachings were compatible with ]. The Hermetic idea of a transcendent, ineffable God who created the cosmos through a process of emanation resonated with early Christian theologians, who sought to reconcile their faith with ].{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| Not all Hermeticists consider their beliefs a religion. Many alloy the beliefs of their own ], ], ], or ] with their mystical ideas. Others hold that all great religions have a few mystical truths at their core, and all religions point to the esoteric tenets of Hermeticism. | |||

| However, Hermeticism’s influence was most pronounced in ], which shared with Hermeticism an emphasis on esoteric knowledge as the key to ]. Both movements taught that the soul’s true home was in the divine realm and that the material world was a place of exile, albeit with a more positive view in Hermeticism. The Hermetic tradition of ascension through knowledge and purification paralleled Gnostic teachings about the soul’s journey back to the divine source, linking the two esoteric traditions.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992}} | |||

| Scholar of obscure religious movements, Tobias Churton, describes it stating: "The Hermetic tradition was both moderate and flexible, offering a tolerant philosophical religion, a religion of the (omnipresent) mind, a purified perception of God, the cosmos, and the self, and much positive enocuragement for the spiritual seeker, all of which the student could take anywhere."<ref>(Churton p. 5)</ref> | |||

| == |

==Core texts== | ||

| Though many more have been falsely attributed to the work of Hermes Trismegistus, Hermeticists commonly accept there to have been 42 books to his credit. However, most of these books are reported to have been destroyed in 391 CE when the ] burnt down the ]. | |||

| ===The ''Hermetica''=== | |||

| There are three major works which are widely known texts for Hermetic beliefs: | |||

| {{main|Hermetica}} | |||

| The ''Hermetica'' is a collection of texts attributed to ], and it forms the foundational literature of the Hermetic tradition. These writings were composed over several centuries, primarily during the Hellenistic, Roman, and early Christian periods, roughly between 200 BCE and 300 CE. The ''Hermetica'' is traditionally divided into two categories: the philosophical or theological Hermetica, and the technical Hermetica, which covers ], ], and other forms of ] science.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992}} | |||

| The most famous and influential of the philosophical Hermetica is the '']'', a collection of seventeen treatises that articulate the core doctrines of Hermeticism. These treatises are primarily dialogues in which Hermes Trismegistus imparts esoteric wisdom to a disciple, exploring themes such as the nature of the divine, the cosmos, the soul, and the path to spiritual enlightenment. Key texts within the ''Corpus Hermeticum'' include '']'', which presents a vision of the cosmos and the role of humanity within it, and '']'', which discusses ], ], and the divine spirit residing in all things.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992}} | |||

| '''The ]''' is the body of work most widely known and is the aforementioned Greek texts. These sixteen books are set up as dialogues between Hermes and a series of others. The first book involves a discussion between ] (also known as ''Nous'' and God) and Hermes, supposedly resulting from a meditative state, and is the first time that Hermes is in contact with God. Poimandres teaches the secrets of the Universe to Hermes, and later books are generally of Hermes teaching others such as ] and his son Tat. | |||

| Another significant text within the Hermetica is the '']'', a concise work that has become central to Western alchemical tradition. Although its exact origins are obscure, the ''Emerald Tablet'' encapsulates the Hermetic principle of "]", which suggests a correspondence between the ] (the universe) and the ] (the individual soul).{{sfnm|1a1=Copenhaver|1y=1992|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} The ''Emerald Tablet'' has been extensively commented upon and has significantly influenced medieval and ] alchemy. | |||

| '''The ] of Hermes Trismegistus''' is a short work which coins the well known term in ] circles "As above, so below." The actual text of that ], as translated by Dennis W. Hauck is "That which is Below corresponds to that which is Above, and that which is Above corresponds to that which is Below, to accomplish the miracle of the One Thing." <ref>(Scully p. 321)<br></ref> The tablet also references the three parts of the wisdom of the whole universe, to which Hermes claims his knowledge of these three parts is why he received the name Trismegistus (thrice great, or Ao-Ao-Ao meaning "greatest"). | |||

| The technical ''Hermetica'' includes works focused on astrology, alchemy, and theurgy—practices that were seen as methods to understand and manipulate the divine forces in the world. These texts were highly influential in the development of the ], contributing to the knowledge base of medieval alchemists and astrologers, as well as to the broader tradition of occultism.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| As the story is told, this tablet was found by ] at ] supposedly in the tomb of Hermes. <ref>(Abel & Hare p. 12)<br></ref> Such a story assumes a mortal Hermes, whether or not the name is correct. | |||

| Other important original Hermetic texts include '']'',{{sfn|Scott|1924}} which consists of a long dialogue between ] and ] on the fall of man and other matters; the '']'';{{sfn|''The Way of Hermes''|1999}} and many fragments, which are chiefly preserved in the anthology of ]. | |||

| ''']''': Hermetic Philosophy, is a book published in 1912 anonymously by three people calling themselves the "Three Initiates", and their identities are suspected to be now known. Claims are made to the book existing in verbal form, prior to publication, and passed around in various occult "circles", or groups. Many of the Hermetic principles are explained in the book. | |||

| ===Interpretation and transmission=== | |||

| ], the ]-headed god of Knowledge, closely related, if not equivalent, to Hermes Trismegistus.]] In addition, there is ''']''', written by Hermes Trismegistus, said to be the key to immortality. To those acquainted to its use, it is said to give them power over the spirits of the air and subterranean divinities. Within it lies the One spiritual path. {{citation needed}} | |||

| The transmission and interpretation of the ''Hermetica'' played a crucial role in its influence on Western thought. During the Renaissance, these texts were rediscovered and translated into Latin, leading to a revival of interest in Hermetic philosophy. The translations by ] and ] were particularly significant, as they introduced Hermetic ideas to Renaissance scholars and contributed to the development of early modern esotericism.{{sfnm|1a1=Copenhaver|1y=1992|2a1=Ebeling|2y=2007}} | |||

| Renaissance thinkers like ] and ] saw in Hermeticism a source of ancient wisdom that could be harmonized with Christian teachings and classical philosophy. The Hermetic emphasis on the divine nature of humanity and the potential for spiritual ascent resonated with the Renaissance ideal of human dignity and the pursuit of knowledge.{{sfnm|1a1=Ebeling|1y=2007|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| === The three parts of the wisdom of the whole universe === | |||

| Hermes Trismegistus is accredited with the name Trismegistus, meaning the "Thrice Great" or "Thrice Greatest" because, as he claims in ''The ]'', he knows the three parts of the wisdom of the whole universe. <ref>(Scully p. 322)<br></ref> The three parts of the wisdom are ], ], and ]. | |||

| Throughout history, the ''Hermetica'' has been subject to various interpretations, ranging from philosophical and mystical readings to more practical applications in alchemy and magic. The esoteric nature of these texts has allowed them to be adapted to different cultural and intellectual contexts, ensuring their enduring influence across centuries.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| ''']''' - The Operation of the ] - For Hermeticism, Alchemy is not the changing of physical ] into physical ]. <ref>(Hall ''The Hermetic Marriage'' p. 227)<br></ref> Rather, one attempts to turn themselves from a base person (symbolized by lead) into an adept master (symbolized by gold). The various stages of chemical ] and ], among them, are metaphorical for the Magnum Opus (Latin for Great Work) performed on the soul. (Scully p. 11) | |||

| ==Philosophical and theological concepts== | |||

| ''']''' - The Operation of the ] - Hermes claims that ] discovered this part of the wisdom of the whole universe, astrology, and taught it to man. <ref>(Powell pp. 19-20)<br></ref> In Hermetic thought, it is likely that the movements of the planets have meaning beyond the laws of physics and actually holding metaphorical value as symbols in the mind of ], or God. Astrology has influences upon the Earth, but does not dictate our actions, and wisdom is gained when we know what these influences are and how to deal with them. | |||

| {{anchor|Redirect target for the All/the all}}<!-- this anchor should always be placed on the line above the section heading that deals with the concept of 'the All' --> | |||

| {{redirect|The All|the album by Smif-N-Wessun|The All (album)}} | |||

| ===Cosmology and theology=== | |||

| ''']''' - The Operation of the ]s - There are two different types of magic, according to ]'s ''Apology'', completely opposite of one another. The first is γοητεια,], black magic reliant upon an alliance with evil spirits (i.e. demons). The second is Theurgy, ] reliant upon an alliance with divine spirits (i.e. angels, archangels, God).<ref>(Garstin p. v)<br></ref> | |||

| ====God as 'the All'==== | |||

| In the ], the ultimate reality is called by many names, such as God, Lord, Father, Mind ('']''), the Creator, the All, the One, etc.<ref>{{harvnb|Festugière|1944–1954|loc=vol. II, pp. 68–71}}; {{harvnb|Bull|2018|p=303}}.</ref> In the Hermetic view, God is both the all (]: ''to pan'') and the creator of the all: all created things pre-exist in God<ref name="Copenhaver 1992 216">{{harvnb|Copenhaver|1992|p=216}}.</ref> and God is the nature of the cosmos (being both the substance from which it proceeds and the governing principle which orders it),<ref>{{harvnb|Festugière|1944–1954|loc=vol. II, p. 68}}.</ref> yet the things themselves and the cosmos were all created by God. Thus, God ('the All') creates itself,<ref>{{harvnb|Bull|2018|p=303}}</ref> and is both ] (as the creator of the cosmos) and ] (as the created cosmos).<ref name="Copenhaver 1992 216"/> These ideas are closely related to the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Festugière|1944–1954|loc=vol. II, p. 70}}.</ref> | |||

| ====''Prima materia''==== | |||

| Theurgy translates to "The Science or art of Divine Works" and is the practical aspect of the Hermetic art of alchemy. <ref>(Garstin p. 6)<br></ref> Furthermore, alchemy is seen as the "key" to theurgy <ref>(Garstin p. vi)<br></ref>, the ultimate goal of which is to become united with higher counterparts, leading to the attainment of Divine Consciousness. <ref>(Garstin p. 6)<br></ref> | |||

| {{main|Prima materia}} | |||

| ] at the ] in ], based on a design by ].]] | |||

| In Hermeticism, ''prima materia'' is a key concept in the alchemical tradition, representing the raw, undifferentiated substance from which all things originate. It is often associated with ], the formless and potential-filled state that precedes creation. The idea of ''prima materia'' has roots in ], particularly in ] cosmogony, where it is linked to the ], and in the biblical concept of '']'' from Genesis, reflecting a synthesis of classical and Christian thought during the Renaissance.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992}} | |||

| === Hermetic beliefs === | |||

| Hermeticism is a ] belief system which teaches that there is ], or one "Cause", of which we are all a part. These beliefs are claimed to have come from ] and have strong philosophical ties to that land. Also it often subscribes to the notion that other beings such as ]s, ]s, ]s and ]s exist in the ]. | |||

| In alchemy, ''prima materia'' is the substance that undergoes transformation through processes such as '']'', the blackening stage associated with chaos, which ultimately leads to the creation of the ]. This transformation symbolizes the '']'' ('Great Work') of the alchemist, seeking to purify and elevate the material to its perfected state. Renaissance figures like ] expanded on this concept,{{efn|{{harvnb|Khunrath|1708|p=68}}: "he light of the soul, by the will of the Triune God, made all earthly things appear from the primal Chaos."}} connecting it to the elements and the broader Hermetic belief in the unity of matter and spirit.{{sfnm|1a1=Ebeling|1y=2007|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| ], 33rd degree ] and Hermetic scholar, however, claims that Hermeticism has foremost inspired three movements, the ], ], and the ]. <ref>(Hall ''The Hermetic Marriage'' p. 226)<br></ref> There has also been ] which has fallen into ruin.{{citation needed}} Outside of these three orders, at least, Hermeticism is a personal spiritual path which rewards open mindedness and personal logical deduction.{{citation needed}} | |||

| The significance of ''prima materia'' in Hermeticism lies in its representation of the potential for both material and spiritual transformation, embodying the Hermetic principle of "]", where the ] reflect each other in the alchemical process.{{sfnm|1a1=Copenhaver|1y=1992|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| ==== God and reality ==== | |||

| In the Hermetic view, all is in the mind of ], the Hermetic conception of ], as expressed in the '']'': "We have given you the Hermetic Teaching in regarding the Mental Nature of the Universe - the truth that 'the Universe is Mental - held in the Mind of THE ALL.'" <ref>(Three Initiates p. 96)<br></ref> | |||

| ===The nature of divinity=== | |||

| Everybody and Everything in the ] is part of this entity. As everything is mental, it is also a vibration <ref>(Three Initiates p. 137)<br></ref>. All vibrations vibrate from the densest of physical particles, through mental states, to the highest spiritual vibrations. In Hermeticism, the only difference between different states of physical matter, mentality, and spirituality is the frequency of their vibration. The higher the vibration, the further it is from base matter. <ref>(Three Initiates pp. 138-47)<br></ref> | |||

| ====''Prisca theologia''==== | |||

| ], from the ], is often thought to display the Hermetic concept of "as above, so below".]] | |||

| Hermeticists adhere to the doctrine of '']'', the belief that a single, true theology exists, which is present in all religions and was revealed by God to humanity in antiquity.{{sfnm|1a1=Yates|1y=1964|1p=14|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=1997|2p=360}} Early Christian theologians, including ] such as ] and ], referenced ], sometimes portraying him as a wise pagan prophet whose teachings could complement Christian doctrine.{{sfnm|1a1=Copenhaver|1y=1992|2a1=Ebeling|2y=2007}} | |||

| ==== Classical elements ==== | |||

| The four classical elements of ], ], ], and ] are used often in alchemy, and are alluded to several times in the Corpus Hermeticum. However, it should be noted that these elements represent ideas rather than physical elements. Fire is the ascending, active, masculine principle, which is kept from going too far with air, which represents rational thought. Water is the descending, reflective, emotional feminine principle, which is kept from going too far by earth, which represents a solid, practical foundation in the real world.{{fact}} | |||

| During the ], scholars such as ] and ] sought to integrate Hermetic teachings into ], viewing the Hermetic writings as remnants of an ancient wisdom that predated and influenced all religious traditions, including ]. It was during this period that the association of Hermes Trismegistus with biblical figures like ], or as part of a lineage including ] and ], was more explicitly developed by these scholars to harmonize Hermetic thought with biblical narratives.{{sfnm|1a1=Yates|1y=1964|1pp=27, 52, 293|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992|2p=xlviii}} This blending of traditions was part of a broader intellectual effort to reconcile pagan and Christian wisdom during this period.{{sfn|Hanegraaff|2012}} | |||

| ==== Mental gender, polarity, and duality ==== | |||

| Hermeticists take to heart one of the primary ideas of ], ].{{citation needed}} The implementation of this Taoist principle, which may or may not have been discovered independently, has been split across many teachings.{{citation needed}} | |||

| ====As above, so below==== | |||

| ], the shared concept between Hermeticism and ]]] | |||

| {{main|As above, so below}} | |||

| The primary place where it has had an impact is in the principle of ]. Duality states that everything has two sides, two opposing attributes which make up the same thing. This idea is incorporated into the concept of polarity: | |||

| "As above, so below" is a popular modern ] of the second verse of the ''Emerald Tablet'' (a compact and cryptic text attributed to Hermes Trismegistus and first attested in a late eight or early ninth century ] source),{{sfnm|1a1=Kraus|1y=1942–1943|2a1=Weisser|2y=1980|p=54}} as it appears in its most widely divulged medieval ] translation:{{sfn|''The Emerald Table''|1928}} | |||

| {{blockquote|text= | |||

| :"Everything is dual; everything has poles; everything has its pair of opposites; like and unlike are the same; opposites are identical in nature, but different in degree; extremes meet; all truths are but half-truths; all paradoxes may be reconciled." <ref>(Three Initiates p. 149)<br></ref> | |||

| {{lang|la|Quod est superius est sicut quod inferius, et quod inferius est sicut quod est superius.}} | |||

| That which is above is like to that which is below, and that which is below is like to that which is above. | |||

| |multiline=yes | |||

| |source='']'' | |||

| }} | |||

| ====The seven heavens==== | |||

| Polarity takes duality and moves a few steps further, saying that there are an infinite number of degrees between one side of a duality, and the other side. If you pick two things of different temperature, something else can be hotter than one of them, and colder than the other. <ref>(Three Initiates p. 151)<br></ref> Likewise you can turn one side of a duality into another, but not into a different thing. For example, hot and cold being opposites, you can turn hot into cold, and cold into hot, but you cannot turn hot into sharp, or sharp into cold; nor can hot be turned into courage or fear. <ref>(Three Initiates p. 154)<br></ref> | |||

| {{further|Body of light}} | |||

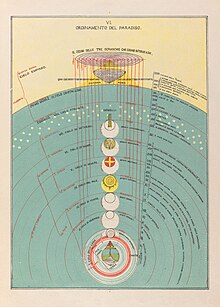

| ]'', Plate VI: "The Ordering of Paradise" by ] (1804–1882)]] | |||

| In addition to the principles of ''prisca theologia'' and "as above, so below," Hermeticism teaches that the soul's journey back to the divine involves ascending through the ]. These heavens correspond to the seven ] and represent stages of spiritual purification and enlightenment. As the soul transcends each heavenly sphere, it sheds the material influences and attachments associated with that level, progressively aligning itself with the divine order. This process symbolizes the soul's return to its divine origin, ultimately seeking unity with The One—the source of all existence. The concept of the seven heavens underscores the Hermetic belief in the potential for spiritual transformation through divine knowledge and practice, guiding the soul toward its ultimate goal of reunification with the divine.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992}} | |||

| ] is the part of yin and yang that polarity and duality do not deal with.{{citation needed}} Yin is feminine and yang is masculine, and these principles which are viewed as a special case of polarity, are put into the masculine (action) and feminine (thought) principles.{{citation needed}} | |||

| === |

===Creation, the human condition, and spiritual ascent=== | ||

| ====Cosmogony and the fall of man==== | |||

| ] displaying the Hermetic concept of "as above, so below." It is thought that the modern Tarot may be based on ''The Book of Thoth''.]] | |||

| {{Main|Fall of man}} | |||

| A ] is told by God to Hermes in the first book of the '']''. It begins when God, by an act of will, creates the primary matter that is to constitute the ]. From primary matter God separates the ] (earth, air, fire, and water). "]" then leaps forth from the materializing four elements, which were unintelligent. Nous then makes the seven heavens spin, and from them spring forth creatures without speech. Earth is then separated from water, and animals (other than man) are brought forth. Then God orders the elements into the ] (often held to be the spheres of ], ], ], ], ], the Sun, and the ], which travel in circles and govern ]). The God then created ] man, in God's own image, and handed over his creation.{{sfn|Segal|1986|pp=16–18}} | |||

| Man carefully observed the creation of nous and received from God man's authority over all creation. Man then rose up above the spheres' paths to better view creation. He then showed the form of the All to Nature. Nature fell in love with the All, and man, seeing his reflection in water, fell in love with Nature and wished to dwell in it. Immediately, man became one with Nature and became a slave to its limitations, such as sex and ]. In this way, man became speechless (having lost "the Word") and he became "]", being mortal in body yet immortal in ], and having authority over all creation yet subject to destiny.{{sfn|Westcott|2012}} | |||

| These words circulate throughout occult and magical circles, and they come from Hermetic texts. The concept was first laid out in ''The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus'', in the words "That which is Below corresponds to that which is Above, and that which is Above, corresponds to that which is Below, to accomplish the miracles of the One Thing." <ref>(Scully p. 321)<br></ref> | |||

| The alternative account of the fall of man, as preserved in '']'', describes a process in which God, after creating the universe and various deities, fashioned human souls from a mysterious substance and assigned them to dwell in the astral region. These souls were then tasked with creating life on Earth. However, the souls became prideful and sought equality with the highest gods, which displeased God. As a consequence, God instructed Hermes to create physical bodies to imprison the souls as a form of punishment. The souls were told that their time on Earth would be marked by suffering, but if they lived worthily of their divine origin, they would eventually return to the heavenly realm. If not, they would face repeated reincarnation on Earth.{{sfn|Scott|1924}} | |||

| In accordance with the various levels of reality: physical, mental, and spiritual, this relates that what happens on any level happens on every other. This is however more often used in the sense of the ]. The microcosm is oneself, and the macrocosm is the universe. The macrocosm is as the microcosm, and vice versa; within each lies the other, and through understanding one (usually the microcosm) you can understand the other. <ref>(Garstin p. 35)<br></ref> | |||

| ==== |

====Good and evil==== | ||

| Hermes explains in Book 9 of the '']'' that nous (reason and knowledge) brings forth either good or evil, depending upon whether one receives one's perceptions from God or from ]s. God brings forth good, but demons bring forth evil. Among the evils brought forth by demons are: "adultery, murder, violence to one's father, sacrilege, ungodliness, strangling, suicide from a cliff and all such other demonic actions".{{sfn|''The Way of Hermes''|1999|p=42}} | |||

| There are mentions in Hermeticism about ]. As Hermes states: | |||

| The word "good" is used very strictly. It is restricted to references to God.{{sfn|''The Way of Hermes''|1999|p=28}} It is only God (in the sense of the nous, not in the sense of the All) who is completely free of evil. Men are prevented from being good because man, having a body, is consumed by his physical nature, and is ignorant of the Supreme Good.{{sfn|''The Way of Hermes''|1999|p=47}} '']'' explains that evil is born from desire which itself is caused by ignorance, the intelligence bestowed by God is what allows some to rid themselves of desire.{{sfn|''Asclepius''|2001|p=31}} | |||

| :"O son, how many bodies we have to pass through, how many bands of demons, through how many series of repetitions and cycles of the stars, before we hasten to the One alone?" <ref>(''Way of Hermes'' p. 33)<br></ref> | |||

| A focus upon the ] is said to be the only thing that offends God: | |||

| ] also claims that there is a general acceptance among Hermeticists for constant reincarnation between both sexes, as in some way integral, but not absolutely vital, within Hermeticism. <ref>(Hall ''The Hermetic Marriage'' p. 234)<br></ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|As processions passing in the road cannot achieve anything themselves yet still obstruct others, so these men merely process through the universe, led by the pleasures of the body.{{sfn|''The Way of Hermes''|1999|pp=32–3}} | |||

| }} | |||

| One must create, one must do something positive in one's life, because God is a generative power. Not creating anything leaves a person "sterile" (i.e., unable to accomplish anything).{{sfn|''The Way of Hermes''|1999|p=29}} | |||

| ==== Causation ==== | |||

| One tenet of Hermeticism, which may be the sole work of '']'' is the tenet of causation. Causation is in a simplified form, simply cause and effect. Each cause has its effect and each effect has its cause. However, when brought up to ''Kybalion'' levels, this principle states that there is no such thing as ], but rather that chance is undiscovered law, organization in the chaos. <ref>(Three Initiates p. 171)<br></ref> (see ]) | |||

| ====Reincarnation and rebirth==== | |||

| The argument ''The Kybalion'' makes on this issue, is that The All is the Law, and as nothing can be outside of The All, nothing can be outside of the Law. The idea of something happening by chance would be, in their opinion, outside of the Law. <ref>(Three Initiates p. 173)<br></ref> | |||

| {{See also|Reincarnation|Transmigration of the soul}} | |||

| ] is mentioned in Hermetic texts. Hermes Trismegistus asked: | |||

| {{blockquote|O son, how many bodies have we to pass through, how many bands of demons, through how many series of repetitions and cycles of the stars, before we hasten to the One alone?{{sfn|''The Way of Hermes''|1999|p=33}} | |||

| ==== Morality, good and evil ==== | |||

| }} | |||

| Hermes explains in Book 9 of the ''Corpus Hermeticum'' that '']'' brings forth both good and evil, depending on if he receives input from God or from the ]s. God brings good, while the demons bring evil. Among those things brought by demons are: | |||

| Rebirth appears central to the practice of hermetic philosophy. The process would begin with a candidate separating themselves from the world before they rid themselves of material vices; they are then reborn as someone completely different from who they were before.{{sfn|Bull|2015}} | |||

| :"adultery, murder, violence to one's father, sacrilege, ungodliness, strangling, suicide from a cliff and all such other demonic actions." <ref>(''Way of Hermes'' p. 42)<br></ref> | |||

| ==Historical development== | |||

| This provides a clearcut view that Hermeticism does indeed include a sense of morality. However, the word good is used very strictly, to be restricted to use to the ''Supreme Good'', God. <ref>(''Way of Hermes'' p. 28)<br></ref> It is only God (in the sense of the Supreme Good, not The All) who is completely free of evil to be considered good. Men are exempt of having the chance of being good, for they have a body, consumed in the physical nature, ignorant of the ''Supreme Good''. <ref>(''Way of Hermes'' p. 47)<br></ref> | |||

| ===Middle Ages=== | |||

| A few primarily Hermetic occult orders were founded in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. In England, it grew interwoven with the Lollard-Familist traditions.{{sfn|Hill|2020|p=}} | |||

| ====Etymology==== | |||

| Among those things which are considered extremely sinful, is the focus on the material life, said to be the only thing that offends God: | |||

| The term 'Hermetic' derives from ''hermeticus'', a ] adjective that first emerged in the ], derived from the name of the Greek god ], to describe the ] writings and practices associated with ]. This term became widely used in reference to the '']'', a body of texts considered to contain secret wisdom on the nature of the divine, the cosmos, and the human soul. | |||

| In English, the word 'Hermetic' appeared in the 17th century. One of the earliest instances in English literature is found in ]'s translation of ''The Pymander of Hermes'', published in 1650.{{sfn|Westcott|2012}} The term was used in reference to "Hermetic writers" such as ]. The synonymous term 'Hermetical' is found in Sir Thomas Browne’s '']'' (1643), where "Hermetical Philosophers" are mentioned, referring to scholars and alchemists who engaged in the study of the natural world through the lens of Hermetic wisdom.{{sfn|Browne|2012|loc=part 1, section 2}} | |||

| :"As processions passing in the road cannot achieve anything themesleves yet still obstruct others, so these men merely process through the universe, led by the pleasures of the body." <ref>(''Way of Hermes'' pp. 32-3)<br></ref> | |||

| The phrase "hermetically sealed" originates from ] practices and refers to an airtight sealing method used in laboratories. This term became a metaphor for the safeguarding of esoteric knowledge, representing the idea that such wisdom should be kept hidden from the uninitiated.{{sfn|Copenhaver|1992}} | |||

| It is troublesome to oneself to have no "children". This is a symbolic description, not to mean physical, biological children, but rather creations. Immediately before this claim, it is explained that God is "the Father" because it has authored all things, it creates. Whether father or mother, one must create, do something positive in their life, as the Supreme Good is a "generative power". The curse for not having "children" is to be imprisoned to a body , neither male (active) nor female (thoughtful), leaving that person with a type of sterility, that of being unable to accomplish anything. <ref>(''Way of Hermes'' p. 29)<br></ref> | |||

| Over time, the word 'Hermetic' evolved to encompass a broader range of meanings, often signifying something mysterious, ], or impenetrable. This evolution reflects the central theme of secrecy within the Hermetic tradition, which emphasizes the importance of protecting sacred knowledge from those who are not prepared to receive it.{{sfn|Ebeling|2007}} | |||

| ==== Creation legend ==== | |||

| In ], the origin belief is not taken literally, but an attempt is made to understand it metaphorically. <ref>(Hall ''The Hermetic Marriage'' p. 228)<br></ref> The tale is given in the first book of the ] by ] ] to ] after much meditation. | |||

| ===Renaissance revival=== | |||

| It begins as God creates the elements after seeing the ] and creating one just like it (our Cosmos) from its own constituent elements and souls. From there, God, being both ] and ], holding the Word, gave birth to a second Nous, creator of the world. This second Nous created seven powers (often seen as ], ], ], ], ], the ] and the ]) to travel in circles and govern destiny. | |||

| {{further|Renaissance magic}} | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| The ] has been greatly influenced by Hermeticism. After centuries of falling out of favor, Hermeticism was reintroduced to the West when, in 1460, a man named Leonardo di Pistoia{{efn|This Leonardo di Pistoia was a monk {{cite web |url=http://www.ritmanlibrary.nl/c/p/lib/coll.html |title=J.R. Ritman Library – Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica |access-date=2007-01-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070101222307/http://www.ritmanlibrary.nl/c/p/lib/coll.html |archive-date=2007-01-01 }}, not to be confused with the artist ] who was not born until c. 1483 CE.}} brought the '']'' to ]. He was one of many agents sent out by Pistoia's ruler, ], to scour European monasteries for lost ancient writings.{{sfn|''The Way of Hermes''|1999|p=9}} The work of such writers as ], who attempted to reconcile ] and ], brought Hermeticism into a context more easily understood by Europeans during the time of the Renaissance. | |||

| The Word then leaps forth from the materializing elements, which made them unintelligent. Nous then made the governors spin, and from their matter sprang forth creatures without speech. Earth then was separated from Water and the animals (other than Man) were brought forth from the Earth. | |||

| In 1614, ], a Swiss ], analyzed the Greek Hermetic texts for linguistic style. He concluded that the writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus were not the work of an ancient Egyptian priest but in fact dated to the second and third centuries CE.{{sfnm|1a1=Tambiah|1y=1990|1p=27–28|2a1=''The Way of Hermes''|2y=1999|2p=9}} | |||

| The Supreme Nous then created Man, ], in his own image and handed over his creation. Man carefully observed the creation of his brother, the lesser Nous, and received his and his Father's authority over it all. Man then rose up above the spheres' paths to better view the creation, and then showed the form of God to Nature. Nature fell in love with it, and Man, seeing a similar form to his own reflecting in the water fell in love with Nature and wished to dwell in it. Immediately Man became one with Nature and became a slave to its limitations such as ] and sleep. Man thus became speechless (for it lost the Word) and became double, being mortal in body but immortal in ], having authority of all but subject to ]. | |||

| Even in light of Casaubon's linguistic discovery (and typical of many adherents of Hermetic philosophy in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries), ] in his '']'' (1643) confidently stated: "The severe schools shall never laugh me out of the philosophy of Hermes, that this visible world is but a portrait of the invisible."{{sfn|Browne|2012|loc=part 1, section 12}} | |||

| The tale does not specifically contradict the theory of ], other than for Man, but most Hermeticists fully accept evolutionary theory as a solid grounding for the creation of everything from base matter to Man. <ref>(''Way of Hermes'' pp. 18-20)<br></ref> | |||

| In 1678, flaws in Casaubon's dating were discerned by ], who argued that Casaubon's allegation of forgery could only be applied to three of the seventeen treatises contained within the ''Corpus Hermeticum''. Moreover, Cudworth noted Casaubon's failure to acknowledge the codification of these treatises as a late formulation of a pre-existing oral tradition. According to Cudworth, the texts must be viewed as a ] and not a ]. Lost Greek texts, and many of the surviving vulgate books, contained discussions of alchemy clothed in philosophical metaphor.{{sfn|Genest|2002}} | |||

| ==Hermetic brotherhoods== | |||

| Hermeticism, being opposed by the Church, became a part of the occult underworld, intermingling with other occult movements and practices. The infusion of Hermeticism into occultism has given it great influence in Western magical traditions. Hermeticism's spiritual practices were found very useful in magical work, especially in Theurgic (divine) practices as opposed to Goëtic (profane) practices, due to the religious context from which Hermeticism sprang forth. | |||

| In 1964, ] advanced the thesis that Renaissance Hermeticism, or what she called "the Hermetic tradition", had been a crucial factor in the development of modern science.<ref>{{harvnb|Yates|1964}}; {{harvnb|Yates|1967}}; {{harvnb|Westman|McGuire|1977}}</ref> While Yates's thesis has since been largely rejected,<ref>{{harvnb|Ebeling|2007|pp=101–102}}; {{harvnb|Hanegraaff|2012|pp=322–334}}</ref> the important role played by the 'Hermetic' science of alchemy in the thought of such figures as ] (1580–1644), ] (1627–1691) or ] (1642–1727) has been amply demonstrated.<ref>{{harvnb|Principe|1998}}; {{harvnb|Newman|Principe|2002}}; {{harvnb|Newman|2019}}.</ref> | |||

| Using the teachings and imagery of the Jewish Kabbalah and Christian Mysticism, Hermetic Theurgy was used effectively and in a context more easily understood by Europeans in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. | |||

| ===Modern period=== | |||

| A few primarily Hermetic occult orders were founded in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Hermetic magic underwent a ] revival in Western Europe (Regardie p. 17), where it was practiced by people such as the ], Aurum Solis, Ragon, Kenneth M. Mackenzie, ], Frederick Hockley, ], and ]. <ref>(Regardie pp. 15-6)</ref> | |||

| ] is a movement which incorporates the Hermetic philosophy. It dates back to the 17th century. The sources dating the existence of the Rosicrucians to the 17th century are three German pamphlets: the '']'', the '']'', and '']''.{{sfn|Yates|1972}} Some scholars believe these to be hoaxes of the time and say that later Rosicrucian organizations are the first actual appearance of a Rosicrucian society.{{sfn|Lindgren|n.d.}} | |||

| Hermetic magic underwent a 19th-century revival in Western Europe,{{sfn|Regardie|1940|p=17}} where it was practiced by groups such as the ]. It was also practiced by individual persons, such as ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Regardie|1940|pp=15–6}} The '']'' is a book anonymously published in 1908 by three people who called themselves the "Three Initiates", and which expounds upon essential Hermetic principles.{{cn|date=August 2024}} | |||

| === Rosicrucianism === | |||

| ] was a Hermetic/] movement dating back to the ]. It has officially fallen out of existence in the ], though some claim it merely fell into complete secrecy. It consisted of a secretive inner body, and a more public outer body under the direction of the inner body. | |||

| In 1924, ] placed the date of the Hermetic texts shortly after 200 CE, but ] placed their origin between 200 and 500 BCE.{{sfn|Abel|Hare|1997|p=7}} | |||

| This movement was symbolized by the rose (feminine) and the cross (masculine) which came together to symbolize God or rebirth. This is very similar to the Egyptian use of the ]. However, these also led to false accusation that the order practiced grotesque orgy rituals. | |||

| In 1945, Hermetic texts were found near the Egyptian town ]. One of these texts had the form of a conversation between Hermes and ]. A second text (titled ''On the Ogdoad and Ennead'') told of the ]. It was written in the ], the latest and final form in which the ] was written.{{sfn|''The Way of Hermes''|1999|pp=9–10}} | |||

| The Rosicrucian Order consisted of a graded system (similar to ]) in which members moved up in rank and gained access to more knowledge, for which there was no fee. Once a member was deemed able to understand the knowledge, they moved on to the next grade. | |||

| ] says "It is now completely certain that there existed before and after the beginning of the Christian era in Alexandria a secret society, akin to a Masonic lodge. The members of this group called themselves 'brethren,' were initiated through a baptism of the Spirit, greeted each other with a sacred kiss, celebrated a sacred meal and read the Hermetic writings as edifying treatises for their spiritual progress."{{sfn|Quispel|2004}} On the other hand, Christian Bull argues that "there is no reason to identify as the birthplace of a Hermetic lodge as several scholars have done. There is neither internal nor external evidence for such an Alexandrian lodge, a designation that is alien to the ancient world and carries Masonic connotations."{{sfn|Bull|2018|p=454}} | |||

| There were three steps to their spiritual path: ], ], and ]. In turn, there were three goals to the order: 1) the abolition of ] and the institution of rule by a philosophical elect, 2) reformation of science, philosophy, and ethics, and 3) discovery of the ]. | |||

| According to ], Hermeticism was a Hellenistic mysticism contemporaneous with the Fourth Gospel, and Hermes Tresmegistos was "the Hellenized reincarnation of the Egyptian deity ], the source of wisdom, who was believed to deify man through knowledge (''gnosis'')."{{sfn|Vermes|2012|p=128}} | |||

| The order claimed that secrecy was needed because "powerful people" opposed, and hindered, them. They promised that the time was coming when all their knowledge would, by mandate of God, be revealed to all. They already accepted any person who was seeking their enlightenment. They also claimed that the ] wielded great power, but misused it, and thus were doomed to destruction. Furthermore, they condemned what they deemed "pseudo-alchemists and philosophers" whom strayed from God's path. | |||

| ====Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn==== | |||

| Amazing claims were made of these men, including that they worked miracles, could shapeshift, and teleport where they wished, among them. <ref>(Hall ''The Secret Teachings of All Ages'' pp. 455-66)</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn}} | |||

| {{Golden Dawn}} | |||

| The ] was a specifically Hermetic society that taught alchemy, ], and the magic of Hermes, along with the principles of occult science. The Order was open to both sexes and treated them as equals.{{sfn|Greer|1994}} | |||

| The only source dating the existence of the Rosicrucians as far back as the 17th century are a pair of German pamphlets: the '']'' and the '']''. Many scholars believe these to be hoaxes, and that antedating Rosicrucian orginisations are the first appearance of any real Rosicrucian fraternity. Modern R.C. orginisations such as the ] claim to possess documents dating their existence as far back as classical Greece and Egypt, but these sources are not available to non-members. | |||

| ], a member and later the head of the Golden Dawn, wrote ''The Hermetic Museum'' and ''The Hermetic Museum Restored and Enlarged''. He edited ''The Hermetic and Alchemical Writings of Paracelsus'', which was published as a two-volume set. He considered himself to be a Hermeticist and was instrumental in adding the word "Hermetic" to the official title of the Golden Dawn.{{sfn|Gilbert|1987}} | |||

| === Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn === | |||

| {{main|Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn}} | |||

| The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn claims descent from the Rosicrucians, officially instituted in 1887 CE. Unlike the ], the Golden Dawn was open to both sexes, and treated both as equal. The order was a specifically Hermetic society, teaching the arts of alchemy, qabbalah, and the magic of Hermes along with the principles of occult science. ] claims that there are many, many orders who know what they do of magic from what has been leaked out of the Golden Dawn by what he deems "renegade members." | |||

| The |

The Golden Dawn maintained the tightest of secrecy, which was enforced by severe penalties for those who disclosed its secrets. Overall, the general public was left oblivious of the actions, and even of the existence, of the Order, so few if any secrets were disclosed.{{sfn|Regardie|1940|pp=15–7}} | ||

| Its secrecy was broken first by ] in 1905 and later by ] in 1937. Regardie gave a detailed account of the Order's teachings to the general public.{{sfn|Regardie|1940|p=ix}} | |||

| ====Scholarship on the ''Hermetica''==== | |||

| {{See also|Hermetica#History_of_scholarship_on_the_Hermetica|label 1=History of scholarship on the Hermetica}} | |||

| After the ] and even within the 20th century, scholars did not study Hermeticism nearly as much as other topics; however, the 1990s saw a renewed interest in Hermetic scholarly works and discussion.{{sfn|Carrasco|1999|p=425}} | |||

| == |

==Hermetic practices== | ||

| "The three parts of the wisdom of the whole universe" is a phrase derived from the ] referring to three disciplines of Hermeticism. Hermetic practices are diverse and deeply rooted in the esoteric traditions of ], ], ], and other ] disciplines. These practices are not merely ritualistic but are aimed at achieving spiritual transformation, aligning the practitioner with the divine order, and unlocking hidden knowledge about the self and the cosmos. | |||

| * ] | |||

| === |

===Alchemy=== | ||

| <!--] redirects here--> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ], or the operation of the ], is perhaps the most well-known of the Hermetic practices, often misunderstood as merely a ] attempt to turn ]s into gold. In Hermeticism, however, alchemy is primarily a spiritual discipline, where the physical transformation of materials is a metaphor for the spiritual purification and perfection of the soul. The ultimate goal of alchemical work is the creation of the ], which symbolizes the attainment of spiritual enlightenment and immortality. Alchemy is not merely the changing of lead into gold, which is called ].{{sfn|Principe|2013|pp=13, 170}} It is an investigation into the spiritual constitution, or life, of matter and material existence through an application of the mysteries of birth, death, and resurrection.{{sfn|Eliade|1978|pp=149, 155–157}} | |||

| ===Famous Hermeticists=== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| The alchemical process is divided into stages, such as '']'' (blackening), '']'' (whitening), and '']'' (reddening), each representing different phases of spiritual purification and enlightenment. '']'', or the original chaotic substance from which all things are formed, is central to alchemy. The various stages of chemical ] and ], among other processes, are aspects of these mysteries that, when applied, quicken nature's processes to bring a natural body to perfection.{{sfn|Geber|1991}} By transmuting prima materia into the philosopher's stone, the alchemist seeks to achieve unity with the divine and realize their true nature as a divine being.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992|3a1=Hanegraaff|3y=2012}} This perfection is the accomplishment of the ] ({{langx|la|]}}). | |||

| ===Hermetic organizations=== | |||

| ===Astrology=== | |||

| * ] | |||

| <!--] redirects here--> | |||

| * ] | |||

| ] in Hermeticism is not merely the study of celestial bodies' influence on human affairs but a means of understanding the divine order of the cosmos. The positions and movements of the ] and ] are seen as reflections of divine will and the structure of the universe, holding metaphorical value as symbols in the mind of ]. Hermetic astrology seeks to decode these celestial messages to align the practitioner’s life with the divine plan. It also plays a role in determining the timing of rituals and alchemical operations, as certain astrological conditions are believed to be more conducive to spiritual work.{{sfnm|1a1=Copenhaver|1y=1992|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} The discovery of astrology is attributed to ], who is said to have discovered this part of the wisdom of the whole universe and taught it to man.<ref>{{harvnb|Powell|1991|pp=19–20}}.</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| == |

===Theurgy=== | ||

| {{further|Renaissance magic}} | |||

| ] is a practice focused on ] the presence of gods or divine powers to purify the soul and facilitate its ascent through the heavenly spheres. Unlike purely magical operations aimed at influencing the physical world, theurgical practices are intended to bring the practitioner into direct contact with the divine. By engaging in theurgy, the Hermetic practitioner seeks to align their soul with higher spiritual realities, ultimately leading to union with The One. This practice often involves the ] or the use of sacred names and symbols to draw down divine energy.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Ebeling|2y=2007}} In ] influenced by ], this divine magic is reliant upon a ] of ]s, ]s, and the ].{{sfn|Garstin|2004|p=v}} | |||

| "Theurgy" translates to the "science or art of divine works" and is the practical aspect of the Hermetic art of alchemy.{{sfn|Garstin|2004|p=6}} Furthermore, alchemy is seen as the "key" to theurgy,{{sfn|Garstin|2004|p=vi}} the ultimate goal of which is to become united with higher counterparts, leading to the attainment of divine consciousness.{{sfn|Garstin|2004|p=6}} | |||

| <references /> | |||

| ===Hermetic Qabalah=== | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{main|Hermetic Qabalah}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Abel, Christopher R. and Hare, William O. | title=Hermes Trismegistus: An Investigation of the Origin of the Hermetic Writings | location=Sequim | publisher=Holmes Publishing Group | year=1997 | id= }} | |||

| Hermetic Qabalah is an adaptation and expansion of Jewish ] thought within the context of ]. It plays a significant role in Hermetic practices by providing a framework for understanding the relationship between the divine, the cosmos, and the self. The central symbol in Hermetic Qabalah is the ], which represents the structure of creation and the path of spiritual ascent. Each of the ten spheres (]) on the Tree corresponds to different aspects of divinity and stages of spiritual development. | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Budge, E.A. Wallis | title=The Egyptian Book of the Dead: (The Papyrus of Ani) Egyptian Text Transliteration and Translation | location=New York | publisher=Dover Publications | year=1895 | id= }} | |||

| *Churton, Tobias. ''The Golden Builders: Alchemists, Rosicrucians, and the First Freemasons''. New York: Barnes and Noble, 2002. | |||

| Hermetic Qabalah integrates alchemical, astrological, and theurgical elements, allowing practitioners to work with these disciplines in a unified system. Through the study and application of Qabalistic principles, Hermetic practitioners seek to achieve self-knowledge, spiritual enlightenment, and ultimately, unity with the divine.{{sfnm|1a1=Copenhaver|1y=1992|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Garstin, E.J. Langford | title=Theurgy ''or'' The Hermetic Practice | location=Berwick | publisher=Ibis Press | year=2004 | id= }} ''Published Posthumously'' | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Hall, Manly P. | title=The Hermetic Marriage | publisher=Kessinger Publishing | year=date unknown | id= }} | |||

| ==Hermeticism and other religions== | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Hall, Manly P. | title=The Secret Teachings of All Ages | location=San Francisco | publisher=H.S. Crocker Company | year=1928 (copyright not renewed) | id= }} | |||

| {{main|Hermetism and other religions}} | |||

| *Hoeller, Stephan A. ''On the Trail of the Winged God: Hermes and Hermeticism Throughout the Ages''. 1996. | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Powell, Robert A. | title=Christian Hermetic Astrology: The Star of the Magi and the Life of Christ | location=Hudson | publisher=Anthroposohic Press | year=1991 | id= }} | |||

| Hermeticism has influenced and been influenced by major religious traditions, particularly Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. During the Renaissance, Christian scholars like ] integrated Hermetic teachings into Christian theology, viewing them as ancient wisdom compatible with Christian doctrine. This led to the development of a Christianized Hermeticism that saw ] as a figure of proto-Christian knowledge.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Regardie, Israel | title=The Golden Dawn | location=St. Paul | publisher=Llewellyn Publications | year=1940 | id= }} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Salaman, Clement and Van Oyen, Dorine and Wharton, William D. and Mahé, Jean-Pierre | title=The Way of Hermes: New Translations of The Corpus Heremticum and The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius | location=Rochester | publisher=Inner Traditions | year=2000 | id= }} | |||

| In Judaism, Hermetic ideas merged with ] thought, leading to the development of ]. This syncretic system combined Hermetic principles with ], significantly influencing Western esotericism.{{sfnm|1a1=Ebeling|1y=2007|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Scully, Nicki | title=Alchemical Healing: A Guide to Spiritual, Physical, and Transformational Medicine | location=Rochester | publisher=Bear & Company | year=2003 | id= }} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Three Initiates | title=The Kybalion | location=Chicago | publisher=The Yogi Publication Society/Masonic Temple | year=1912 | id= }} | |||

| ], particularly ], and ] were also influenced by Hermeticism. Islamic scholars preserved and transmitted Hermetic texts, integrating them into ] and spiritual practices.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Ebeling|2y=2007}} | |||

| ==Criticism and controversies== | |||

| Hermeticism, like many esoteric traditions, has faced criticism and sparked controversy over the centuries, particularly in relation to its origins, authenticity, and role in modern spiritual and occult movements. | |||

| ===Scholarly debates=== | |||

| The authenticity and historical origins of Hermetic texts have been a major point of debate among scholars. Some researchers argue that the '']'' and other Hermetic writings are not the remnants of ancient wisdom but rather ] works composed during the Hellenistic period, blending Greek, Egyptian, and other influences. The dating of these texts has been particularly contentious, with some scholars placing their origins in the early centuries CE, while others suggest even earlier roots.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992}} | |||

| Another scholarly debate revolves around the figure of Hermes Trismegistus himself. While traditionally considered an ancient sage or a syncretic combination of the Greek god ] and the Egyptian god ], modern scholars often view Hermes Trismegistus as a symbolic representation of a certain type of wisdom rather than a historical figure. This has led to discussions about the extent to which Hermeticism can be considered a coherent tradition versus a loose collection of related ideas and texts.{{sfnm|1a1=Ebeling|1y=2007|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| ===Reception and criticism in modern times=== | |||

| In modern times, Hermeticism has been both embraced and criticized by various spiritual and occult movements. Organizations like the ] have drawn heavily on Hermetic principles, integrating them into their rituals and teachings. However, some critics argue that the modern use of Hermeticism often distorts its original meaning, blending it with other esoteric traditions in ways that obscure its true nature.{{sfnm|1a1=Ebeling|1y=2007|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| Furthermore, Hermeticism's emphasis on personal spiritual knowledge and its sometimes ambiguous relationship with orthodox religious teachings have led to criticism from more conservative religious groups. These critics often view Hermeticism as a form of ]ism that promotes a dangerous or misleading path away from traditional religious values.{{sfn|Fowden|1986}} | |||

| ==Legacy and influence== | |||

| Hermeticism has left a profound legacy on Western thought, influencing a wide range of esoteric traditions, philosophical movements, and cultural expressions. Its impact can be traced from the Renaissance revival of Hermetic texts to modern esotericism and popular culture. | |||

| ===Influence on Western esotericism=== | |||

| Hermeticism is one of the cornerstones of Western esotericism, with its ideas deeply embedded in various occult and mystical traditions. The Renaissance saw a revival of Hermeticism, particularly through the works of scholars like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, who integrated Hermetic teachings into Christian theology and philosophy. This revival laid the groundwork for the development of Western esoteric traditions, including ], ], and the ].{{sfnm|1a1=Copenhaver|1y=1992|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| The Hermetic principle of "as above, so below" and the concept of ]—the idea that all true knowledge and religion stem from a single ancient source—became central tenets in these esoteric movements. Hermeticism's emphasis on personal spiritual transformation and the pursuit of esoteric knowledge has continued to resonate with various occult groups, influencing modern spiritual movements such as ], founded by ], and contemporary practices of alchemy, astrology, and ].{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Ebeling|2y=2007}} | |||

| ===Influence on literature and culture=== | |||

| Beyond its esoteric influence, Hermeticism has also permeated literature, art, and popular culture. The symbolism and themes found in Hermetic texts have inspired numerous writers, artists, and thinkers. For example, the works of ], ], and ] contain elements of Hermetic philosophy, particularly its themes of spiritual ascent, divine knowledge, and the unity of all things.{{sfnm|1a1=Ebeling|1y=2007|2a1=Hanegraaff|2y=2012}} | |||

| In modern literature, Hermetic motifs can be seen in the works of authors like ], ], and ], who explore themes of hidden knowledge, ], and the mystical connections between the microcosm and macrocosm. Hermetic symbols, such as the caduceus of Hermes and the philosopher’s stone, have also found their way into popular culture, appearing in films, television shows, and video games as symbols of mystery, power, and transformation.{{sfnm|1a1=Fowden|1y=1986|2a1=Copenhaver|2y=1992}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * {{anli|Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica}} | |||

| * {{anli|Hermeneutics}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| {{reflist|30em}} | |||

| ===Works cited=== | |||

| {{refbegin|30em|indent=yes}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Abel |first1=Christopher R. |last2=Hare |first2=William O. | title=Hermes Trismegistus: An Investigation of the Origin of the Hermetic Writings | location=Sequim | publisher=Holmes Publishing Group | year=1997 }} | |||

| <!-- B --> | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Boys-Stones |first=George |title=Post-Hellenistic Philosophy: A Study in Its Development from the Stoics to Origen |year=2001 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-815264-4}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Browne |first=Thomas |author-link=Thomas Browne |editor1-last=Greenblatt |editor1-first=Stephen |editor2-last=Targoff |editor2-first=Ramie |title=Religio Medici and Urne-Buriall |publisher=New York Review Books |year=2012 |isbn=978-1-59017-488-3 |url=https://archive.org/details/religiomedicihyd0000brow |url-access=registration}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Bull |first=Christian H. |date=1 January 2015 |title=Ancient Hermetism and Esotericism |url=https://brill.com/abstract/journals/arie/15/1/article-p109_7.xml |journal=Aries |language=en |volume=15 |issue=1 |pages=109–135 |doi=10.1163/15700593-01501008 |issn=1567-9896}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Bull |first=Christian H. |date=2018 |title=The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom |url= |location=Leiden |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-37084-5 |doi=10.1163/9789004370845 |s2cid=165266222 }} | |||

| <!-- C --> | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Carrasco |first1=David |display-authors=etal |title=Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions |publisher=] |editor=] |year=1999 |isbn=978-0-87779-044-0 |page=425}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Copenhaver |first=Brian P. |author-link=Brian Copenhaver |title=Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction |year=1992 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=0-521-42543-3}} | |||

| <!-- D --> | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Droge |first=Arthur J. |title=Homer or Moses? Early Christian Interpretations of the History of Culture |year=1989 |publisher=J. C. B. Mohr |location=Tübingen |isbn=978-3-16-145354-0}} | |||

| <!-- E --> | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Ebeling |first=Florian |title=The Secret History of Hermes Trismegistus: Hermeticism from Ancient to Modern Times |others=Translated by David Lorton |year=2007 |orig-date=2005 |publisher=Cornell University Press |location=Ithaca |isbn=978-0-8014-4546-0}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last = Eliade|first = Mircea|author-link=Mircea Eliade|title = The Forge and the Crucible: The Origins and Structure of Alchemy|publisher = University of Chicago Press|date= 1978|isbn = 978-0-226-20390-4}} | |||

| <!-- F --> | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Festugière |first=André-Jean |author-link=André-Jean Festugière |year=1944–1954 |title=La Révélation d'Hermès Trismégiste |volume=I-IV |location=Paris |publisher=Gabalda |isbn=978-2-251-32674-0 |lang=fr}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Fowden |first=Garth |author-link=Garth Fowden |title=The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind |year=1986 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-521-32583-7}} | |||

| <!-- G --> | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Garstin |first=E. J. Langford | title=Theurgy ''or'' The Hermetic Practice | location=Berwick | publisher=Ibis Press | year=2004 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |author=Geber |editor-last=Newman |editor-first=W. R. |year=1991 |title=The Summa Perfectionis of Pseudo-Geber: A Critical Edition, Translation and Study |place=Germany |publisher=E. J. Brill |isbn=978-90-04-09464-2}} | |||

| * {{cite web |first=Jeremiah |last=Genest |year=2002 |title=Secretum secretorum: An Overview of Magic in the Greco-Roman World: The Corpus Hermetica |website=Background for Ars Magica sagas |url=http://www.granta.demon.co.uk/arsm/jg/corpus.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170713113339/http://www.granta.demon.co.uk/arsm/jg/corpus.html |archive-date=2017-07-13}} | |||

| * {{cite book |editor-last=Gilbert |editor-first=R. A. |year=1987 |title=Hermetic Papers of A.E. Waite: The Unknown Writings of a Modern Mystic |publisher=Aquarian Press |isbn=978-0-85030-437-4}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Greer |first=Mary K. |year=1994 |title=Women of the Golden Dawn |publisher=Park Street |isbn=0-89281-516-7}} | |||

| <!-- H --> | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Hanegraaff |first=Wouter J. |author-link=Wouter Hanegraaff |year=1997 |title=New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought |publisher=State University of New York Press |isbn=978-0-7914-3854-1}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Hanegraaff |first=Wouter J. |title=Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture |year=2012 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-521-19621-5}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last=Hanegraaff |first=Wouter J. |date=2015 |title=How Hermetic was Renaissance Hermetism? |journal=Aries |volume=15 |issue=2 |pages=179–209 |doi=10.1163/15700593-01502001 |s2cid=170231117 |url=https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/2591988/169836_How_Hermetic_was_Renaissance_Hermetism_.pdf }} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Hill | first=C. | title=Milton and the English Revolution | publisher=Verso Books | year=2020 | isbn=978-1-78873-683-1}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last=Hoeller |first=Stephan A. |author-link=Stephan A. Hoeller |title=On the Trail of the Winged God: Hermes and Hermeticism Throughout the Ages |journal=Gnosis: A Journal of Western Inner Traditions |volume=40 |date=Summer 1996 |url=http://www.gnosis.org/hermes.htm |via=Gnosis.org |access-date=2009-11-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091126020349/http://www.gnosis.org/hermes.htm |archive-date=2009-11-26 }} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last=Horowitz |first=Mitch |author-link=Mitch Horowitz |date=2019 |title=The New Age and Gnosticism: Terms of Commonality |journal=Gnosis: Journal of Gnostic Studies |volume=4 |issue=2 |pages=191–215 |doi=10.1163/2451859X-12340073 |s2cid=214533789 }} | |||

| <!-- K --> | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Khunrath |first=Heinrich |author-link=Heinrich Khunrath |title=Vom Hylealischen, das ist Pri-materialischen Catholischen oder Allgemeinen Natürlichen Chaos der naturgemässen Alchymiae und Alchymisten: Confessio |lang=la |year=1708}} | |||

| * {{cite book |author-link=Paul Kraus (Arabist) |last=Kraus |first=Paul |date=1942–1943 |title=Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque |place=Cairo |publisher=Institut français d'archéologie orientale |volume=II |pages=274–275}} | |||

| <!-- L --> | |||

| * {{cite web|url=http://users.panola.com/lindgren/rosecross.html|first=Carl Edwin |last=Lindgren |date=n.d.|title=The Rose Cross, A Historical and Philosophical View|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121108052032/http://users.panola.com/lindgren/rosecross.html|archive-date=2012-11-08}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|editor-last=Litwa|editor-first=M. David|url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/hermetica-ii/F5187119F7B83D0E2B61A0DEBC56B59F|title=Hermetica II: The Excerpts of Stobaeus, Papyrus Fragments, and Ancient Testimonies in an English Translation with Notes and Introductions|publisher=]|year=2018|location=Cambridge|pages=|doi=10.1017/9781316856567|isbn=<!--9781316856567-->978-1-107-18253-0|s2cid=217372464}} | |||

| <!-- M --> | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Mahé |first=Jean-Pierre |author-link=Jean-Pierre Mahé |title=Hermès en Haute-Egypte |volume=I–II |year=1978–1982 |publisher=Presses de l'Université Laval |location=Quebec |isbn=978-0-7746-6817-0}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Mahé |first=Jean-Pierre |editor1-last=Salaman |editor1-first=Clement |editor2-last=Van Oyen |editor2-first=Dorine |editor3-last=Wharton |editor3-first=William D. |editor4-last=Mahé |editor4-first=Jean-Pierre |title=The Way of Hermes: New Translations of The Corpus Hermeticum and The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius |publisher=Duckworth |location=London |year=1999 |pages=99–122 |chapter=The Definitions of Hermes Trismegistus to Asclepius |isbn=978-0-7156-2939-0}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Marenbon |first=John |author-link=John Marenbon |title=] |year=2015 |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton |isbn=978-0-691-14255-5}} | |||

| <!-- N --> | |||