| Revision as of 09:36, 7 September 2006 edit61.69.149.62 (talk) →Gods← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:08, 30 December 2024 edit undoAnnh07 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers44,016 edits Reverted good faith edits by HopeNHopes (talk): WP:SDNONETags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| '''Egyptian mythology''' or '''Egyptian religion''' is the succession of tentative beliefs held by the people of ] for over three thousand years, prior to the existence of and major exposure to ] and ]. | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Ancient Egyptian religion|expanded=all}} | |||

| {{Ancient Near East mythology}} | |||

| '''Ancient Egyptian religion''' was a complex system of ] beliefs and rituals that formed an integral part of ]ian culture. It centered on the Egyptians' interactions with ] believed to be present and in control of the world. About 1,500 deities are known.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Kaelin |first=Oskar |date=2016-11-22 |title=Gods in Ancient Egypt |url=https://oxfordre.com/religion/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.001.0001/acrefore-9780199340378-e-244 |access-date=2023-04-10 |website=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion |language=en |doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.244|isbn=978-0-19-934037-8 }}</ref> Rituals such as prayer and offerings were provided to the gods to gain their favor. Formal religious practice centered on the ]s, the rulers of Egypt, believed to possess divine powers by virtue of their positions. They acted as intermediaries between their people and the gods, and were obligated to sustain the gods through rituals and offerings so that they could maintain ], the order of the ], and repel ], which was chaos. The state dedicated enormous resources to religious rituals and to the construction of ]. | |||

| Individuals could interact with the gods for their own purposes, appealing for help through prayer or compelling the gods to act through ]. These practices were distinct from, but closely linked with, the formal rituals and institutions. The popular religious tradition grew more prominent over the course of ] as the status of the pharaoh declined. Egyptian belief in the ] and the importance of ] is evident in the great efforts made to ensure the survival of their ] after death – via the provision of tombs, grave goods and offerings to preserve the bodies and spirits of the deceased. | |||

| == Gods == | |||

| ], tomb painting, ca. 1360 BC.]] | |||

| The religion had its roots in ] and lasted for 3,500 years. The details of religious belief changed over time as the importance of particular gods rose and declined, and their intricate relationships shifted. At various times, certain gods became preeminent over the others, including the sun god ], the creator god ], and the mother goddess ]. For a brief period, in the ] promulgated by the pharaoh ], a single god, the ], replaced the traditional pantheon. Ancient Egyptian religion and ] left behind many writings and monuments, along with significant influences on ancient and modern cultures. The religion declined following the ] in 30 BC and Egyptians began converting to ]. In addition practices such as mummification halted. The Ancient Egyptian religion was considered to have fully died in the 530s. Following the Arab conquest of Egypt under ], Egyptians started to convert to ]. | |||

| '''Hello everyone I hope that you are all haveing a great time hope you find what your looking for enjoy!!! Early beliefs can be split into 5 distinct localized groups, | |||

| * the ] of ], whose chief god was ] | |||

| * the ] of ], where the chief god was ] | |||

| * the ]-]-] triad of ], where the chief god was ] | |||

| * the ]-]-] triad of ], where the chief god was ] | |||

| * the ]-]-] triad of ], unusual in that the gods were unconnected before the triad was formalized, where the chief god was ] | |||

| ==Beliefs== | |||

| Throughout the vast and complex history of Egypt, the dominant beliefs of the ancient Egyptians merged and mutated as leaders of different groups gained power. This process continued even after the end of the ]ian civilization as we know it today. As an example, during the New Kingdom Ra and Amun became ]. This "merging" into a single god is typically referred to as ]. Syncretism should be distinguished from mere groupings, also referred to as "families" such as Amun, Mut and Khonsu, where no "merging" takes place. Over time, deities took part in multiple syncretic relationships, for instance, the combination of Ra and ] into ]. However, even when taking part in such a syncretic relationship, the original deities did not become completely "absorbed" into the combined deity, although the individuality of the one was often greatly weakened. Also, these syncretic relationships sometimes involved more than just two deities, for instance, Ptah, Seker and ], becoming ''Ptah-Seker-Osiris''. The goddesses followed a similar pattern. Also important to keep in mind is that sometimes the attributes of one deity got closely associated with another, without any "formal" syncretism taking place. For instance, the loose association of ] with ]. | |||

| The beliefs and rituals now referred to as "ancient Egyptian religion" were integral within every aspect of Egyptian culture; thus the ] possessed no single term corresponding to the concept of religion. Ancient Egyptian religion consisted of a vast and varying set of beliefs and practices, linked by their common focus on the interaction between the world of humans and the world of the divine. The characteristics of the gods who populated the divine realm were inextricably linked to the Egyptians' understanding of the properties of the world in which they lived.{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | pp = 1–5, 80}} | |||

| ===Deities=== | |||

| An interesting aspect of ancient Egyptian religion is that deities sometimes played different conflicting roles. As an example, the lioness ] being sent out by Ra to devour the humans for having rebelled against him, but later on becoming a fierce protectress of the kingdom, life in general and the sick. Even more complex is the roles of ]. Judging the mythology of Set from a modern perspective, especially the mythology surrounding Set's relationship with Osiris, it is easy to cast Set as the arch villain and source of evil. This is wrong, however, as Set was earlier playing the role of destroyer of ], in the service of Ra on his barge, and thus serving to uphold Ma'at (Truth, Justice and Harmony). | |||

| {{Main|Ancient Egyptian deities|List of ancient Egyptian deities}} | |||

| ], ], and ] in the Tomb of Horemheb (]) in the Valley of the Kings]] | |||

| The Egyptians believed that the phenomena of nature were divine forces in and of themselves.{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | pp = 63–64, 82}} These deified forces included the elements, animal characteristics, or abstract forces. The Egyptians believed in a pantheon of gods, which were involved in all aspects of nature and human society. Their religious practices were efforts to sustain and placate these phenomena and turn them to human advantage.<ref name="Allen 43">{{Harvnb | Allen | 2000 | pp = 43–44}}.</ref> This ] system was very complex, as some deities were believed to exist in many different manifestations, and some had multiple mythological roles. Conversely, many natural forces, such as the sun, were associated with multiple deities. The diverse pantheon ranged from gods with vital roles in the universe to minor deities or "demons" with very limited or localized functions.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 30, 32, 89}} It could include gods adopted from foreign cultures, and sometimes humans: deceased pharaohs were believed to be divine, and occasionally, distinguished commoners such as ] also became deified.{{Sfn | Silverman | 1991 | pp = 55–58}} | |||

| The depictions of the gods in ] were not meant as literal representations of how the gods might appear if they were visible, as the gods' true natures were believed to be mysterious. Instead, these depictions gave recognizable forms to the abstract deities by using symbolic imagery to indicate each god's role in nature.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | p = 53}} This iconography was not fixed, and many of the gods could be depicted in more than one form.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 28}} | |||

| Given the diverse tapestry of religious history in ancient Egypt, it comes as no surprise that many different forms of theism evolved. Although mainly ] in nature, at some point even ], as introduced by ] thrived. What is important to realize is that it is very dangerous to try and cast the religion of the ancient Egyptians in any particular theistic form. Even more dangerous to claim is that, towards the end of the Egyptian civilization, a drive toward monotheism was taking place. The evidence of the time (Greaco-Roman period) seems counter to this belief: although syncretism was still taking place (sometimes and more frequently between Egyptian and non-Egyptian deities), many deities were still revered and served. As an example the following which ] enjoyed during these later periods. This is quite evident when one simply looks at the vast number of mummified Ibis birds offered to him. Also, the belief in Egyptian deities were spreading to countries other than Egypt. For instance the Roman belief in, and following of Isis.<b/> | |||

| Many gods were associated with particular regions in Egypt where their cults were most important. However, these associations changed over time, and they did not mean that the god associated with a place had originated there. For instance, the god ] was original patron of the city of ]. Over the course of the ], however, he was displaced in that role by ], who may have arisen elsewhere. The national popularity and importance of individual gods fluctuated in a similar way.{{Sfn | Teeter | 2001 | pp = 340–44}} | |||

| The Egyptians believed that in the beginning, the universe was filled with the dark waters of chaos. The first god, Re-Atum, appeared from the water as the land of Egypt appears every year out of the flood waters of the Nile. <b/>Re-Atum spat and out of the spittle came out the gods Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture). The world was created when Shu and Tefnut gave birth to two children: Nut (sky) & Geb (the Earth). Humans were created when Shu and Tefnut went wandering in the dark wastes and got lost. Re-Atum sent his eye to find them. On reuniting, his tears of joy turned into people. | |||

| Deities had complex interrelationships, which partly reflected the interaction of the forces they represented. The Egyptians often grouped gods together to reflect these relationships. One of the more common combinations was a family triad consisting of a father, mother, and child, who were worshipped together. Some groups had wide-ranging importance. One such group, the ], assembled nine deities into a theological system that was involved in the mythological areas of creation, kingship, and the afterlife.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 74–79}} | |||

| Geb and Nut copulated, and upon Shu's learning of his children's fornication, he separated the two, effectively becoming the air between the sky and ground. He also decreed that the pregnant Nut should not give birth any day of the year. Nut pleaded with Thoth, who on her behalf gambled with the moon-god Yah and won five more days to be added onto the then 360-day year. Nut had one child on each of these days: Osiris, Isis, Seth, Nephthys, and Horus-the-Elder. | |||

| The relationships between deities could also be expressed in the process of ], in which two or more different gods were linked to form a composite deity. This process was a recognition of the presence of one god "in" another when the second god took on a role belonging to the first. These links between deities were fluid, and did not represent the permanent merging of two gods into one; therefore, some gods could develop multiple syncretic connections.{{Sfn | Dunand | Zivie-Coche | 2005 | pp = 27–28}} Sometimes, syncretism combined deities with very similar characteristics. At other times, it joined gods with very different natures, as when Amun, the god of hidden power, was linked with ], the god of the sun. The resulting god, Amun-Ra, thus united the power that lay behind all things with the greatest and most visible force in nature.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 33–35}} | |||

| Osiris, by different accounts, was either the son of Re-Atum or Geb, and king of Egypt. His brother Seth represented evil in the universe. He murdered Osiris and himself became the king. After killing Osiris Seth tore his body into pieces, but Isis rescued most of the pieces for burial beneath the temple. Seth made himself king but was challenged by Osiris's son - Horus. Seth lost and was sent to the desert. He became the God of terrible storms. Osiris was mummified by Anubis and became God of the dead. Horus became the King and from him descended the pharaohs. | |||

| Many deities could be given ]s that seem to indicate that they were greater than any other god, suggesting some kind of unity beyond the multitude of natural forces. This is particularly true of a few gods who, at various points, rose to supreme importance in Egyptian religion. These included the royal patron Horus, the sun-god Ra, and the mother-goddess Isis.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 36, 67}} During the ] ({{circa|1550}}–{{circa|1070 BC}}), Amun held this position. The theology of the period described in particular detail Amun's presence in and rule over all things, so that he, more than any other deity, embodied the all-encompassing power of the divine.{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | pp = 189–92, 241–42}} | |||

| Another version is when Seth made a chest which only Osiris could fit into. He then invited Osiris to a feast. Seth made a bet that no one could fit into the chest. Osiris was the last one to step into the chest, but before he did Seth asked if he could hold Osiris's crown. Osiris agreed and stepped into the chest. As he lay down, Seth slammed the lid shut and put the crown on his head. He then set the chest afloat on the Nile. Isis did not know of her husband's death until the wind told her. She then placed her son in a safe place and cast a spell so no one could find him. When she searched for a husband, a child told her a chest had washed up on the bank and a tree had grown up. The tree was so straight the king had used it for the central pillar. Isis went and asked for her husband's body and it was given to her. The god of the underworld told her that Osiris would be a king, but only in the underworld. | |||

| == |

===Cosmology=== | ||

| ] around it]] | |||

| Egypt had a highly developed view of the afterlife with elaborate rituals for preparing the body and soul for a peaceful life after death. Beliefs about the ] and afterlife focused heavily on preservation of the body, or ba (The soul was known as the ka). This meant that ] and ] were practiced, in order to preserve the individual's identity in the afterlife. Originally the dead were buried in ] caskets in the searing hot ], which caused the remains to dry quickly, preventing decomposition, and were subsequently buried. Later, they started constructing wooden tombs, and the extensive process of ] was developed by the Egyptians around the 4th Dynasty. All soft tissues were removed, and the cavities washed and packed with ], then the exterior body was buried in natron as well. Since it was a stoneable offence to harm the body of the Pharaoh, even after death, the person who made the cut in the abdomen with a rock knife was ceremonially chased away and had rocks thrown at him. | |||

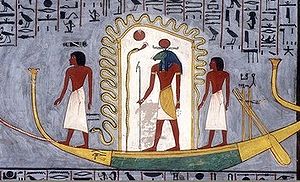

| ] with the new-born sun from the waters of creation.]] | |||

| The Egyptian conception of the universe centered on '']'', a word that encompasses several concepts in English, including "truth", "justice", and "order". It was the fixed, eternal order of the universe, both in the cosmos and in human society, and was often personified as a goddess. It had existed since the creation of the world, and without it the world would lose its cohesion. In Egyptian belief, ''Ma'at'' was constantly under threat from the forces of disorder, so all of society was required to maintain it. On the human level this meant that all members of society should cooperate and coexist; on the cosmic level it meant that all of the forces of nature—the gods—should continue to function in balance.<ref name="Allen 115">{{Harvnb | Allen | 2000 | pp = 115–17}}.</ref> This latter goal was central to Egyptian religion. The Egyptians sought to maintain ''Ma'at'' in the cosmos by sustaining the gods through offerings and by performing rituals which staved off disorder and perpetuated the cycles of nature.{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | pp = 4–5}}<ref name="Shafer 2">{{Harvnb | Shafer | 1997 | pp = 2–4}}.</ref> | |||

| The most important part of the Egyptian view of the cosmos was the conception of time, which was greatly concerned with the maintenance of ''Ma'at''. Throughout the linear passage of time, a cyclical pattern recurred, in which ''Ma'at'' was renewed by periodic events which echoed the original creation. Among these events were the annual ] and the succession from one king to another, but the most important was the daily journey of the sun god Ra.{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | pp = 68–79}}{{Sfn | Allen | 2000 | pp = 104, 127}} | |||

| After coming out of the natron, the bodies were coated inside and out with resin to preserve them, then wrapped with linen bandages, embedded with religious amulets and talismans. In the case of royalty, this was usually then placed inside a series of nested coffins the outermost of which was a stone ]. The ]s, ]s, ] and the ] were preserved separately and stored in ]s protected by the ]. Other creatures were also mummified, sometimes thought to be pets of Egyptian families, but more frequently or more likely they were the representations of the Gods. The ], ], ]s, ] and ] can be found in perfect mummified forms. | |||

| When thinking of the shape of the cosmos, the Egyptians saw the earth as a flat expanse of land, personified by the god ], over which arched the sky goddess ]. The two were separated by ], the god of air. Beneath the Earth lay a parallel ] and undersky, and beyond the skies lay the infinite expanse of ], the chaos and primordial watery ] that had existed before creation.{{Sfn | Lesko | 1991 | pp = 117–21}}{{Sfn | Dunand | Zivie-Coche | 2005 | pp = 45–46}} The Egyptians also believed in a place called the ], a mysterious region associated with death and rebirth, that may have lain in the underworld or in the sky. Each day, Ra traveled over the earth across the underside of the sky, and at night he passed through the Duat to be reborn at dawn.<ref>Allen, James P., "The Cosmology of the Pyramid Texts", in {{Harvnb | Simpson | 1989 | pp = 20–26}}.</ref> | |||

| The ] was a series of almost two hundred spells represented as sectional texts, songs and pictures written on papyrus, individually customized for the deceased, which were buried along with the dead in order to ease their passage into the underworld. In some tombs, the Book of the Dead has also been found painted on the walls, although the practice of painting on the tomb walls appears to predate the formalization of the Book of the Dead as a bound text. One of the best examples of the Book of the Dead is ''The ]'', created around ], which, in addition to the texts themselves, also contains many pictures of Ani and his wife on their journey through the land of the dead. | |||

| In Egyptian belief, this cosmos was inhabited by three types of sentient beings: one was the gods; another was the spirits of deceased humans, who existed in the divine realm and possessed many of the gods' abilities; living humans were the third category, and the most important among them was the pharaoh, who bridged the human and divine realms.{{Sfn | Allen | 2000 | p = 31}} | |||

| In later belief, the soul of the deceased is led into a hall of judgement in ] by ] (god of mummification) and the deceased's ], which was the record of the morality of the owner, is weighed against a single feather representing ]'s (the concept of truth, and order). If the outcome is favorable, the deceased is taken to ], god of the afterlife, in ], but the demon ] (''Eater of Hearts'') – part crocodile, part lion, and part hippopotamus – destroys those hearts whom the verdict is against, leaving the owner to remain in Duat. . A heart that weighed less than the feather was considered a pure heart, not weighed down by the guilt or sins of one's actions in life, resulting in a favorable verdict; a heart heavy with guilt and sin from one's life weighed more than the feather, and wound up eaten by Ammit. | |||

| ===Kingship=== | |||

| == The monotheistic period == | |||

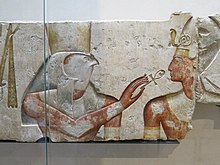

| {{see also|Pharaoh}}], an ] pharaoh, embraced by ]]] | |||

| ] to the pharaoh, ]. Painted limestone. {{Circa|1275 BC}}. 19th dynasty. From the small temple built by Ramses II in ].], ], France.]] | |||

| ] have long debated the degree to which the pharaoh was considered a god. It seems most likely that the Egyptians viewed royal authority itself as a divine force. Therefore, although the Egyptians recognized that the pharaoh was human and subject to human weakness, they simultaneously viewed him as a god, because the divine power of kingship was incarnated in him. He therefore acted as intermediary between Egypt's people and the gods.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 54–56}} He was key to upholding ''Ma'at'', both by maintaining justice and harmony in human society and by sustaining the gods with temples and offerings. For these reasons, he oversaw all state religious activity.{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | pp = 5–6}} However, the pharaoh's real-life influence and prestige could differ from his portrayal in official writings and depictions, and beginning in the late New Kingdom his religious importance declined drastically.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | p = 55}}<ref>Van Dijk, Jacobus, "The Amarna Period and the Later New Kingdom", in {{Harvnb | Shaw | 2000 | pp = 311–12}}.</ref> | |||

| The king was also associated with many specific deities. He was identified directly with ], who represented kingship itself, and he was seen as the son of Ra, who ruled and regulated nature as the pharaoh ruled and regulated society. By the New Kingdom he was also associated with Amun, the supreme force in the cosmos.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 69, 95, 184}} Upon his death, the king became fully deified. In this state, he was directly identified with Ra, and was also associated with ], god of death and rebirth and the mythological father of Horus.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 60–63}} Many mortuary temples were dedicated to the worship of deceased pharaohs as gods.<ref name="Shafer 2"/> | |||

| ] and his family praying to ].]]A short interval of ] (]) occurred under the reign of ], focused on the Egyptian sun deity ]. Akhenaten outlawed the worship of any other god and built a new capital (]) with temples for Aten. The religious change survived only until the death of Akhenaten, and the old religion was quickly restored during the reign of ], most likely Akhenaten's son by a minor wife. Interestingly, Tutankhamun and several other post-restoration pharaohs were excluded from future king lists, as well as the heretics ] and ]. | |||

| ===Afterlife<!--linked from 'Ancient Egyptian burial customs'-->=== | |||

| While most historians regard this period as monotheistic, some researchers do not regard ] as such. They state that people did not worship ], but worshipped the royal family as a pantheon of gods who received their divine power from the Aten. That point of view is largely dismissed by the historical community. Some researchers go as far as to suggest that Akhenaten or some of his viziers were the Biblical ] or Joseph; the ] community dismisses these claims as unscholarly, since none of the theories are based on proper research, and the well-documented worship of ] has nothing in common with the religion of Moses. | |||

| {{Main|Ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs}} | |||

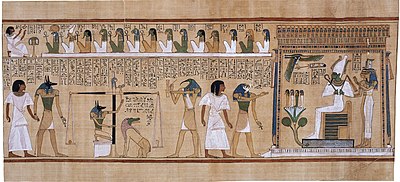

| ] as depicted in the ] (19th Dynasty, c. 1300 BCE)]] | |||

| The elaborate beliefs about death and the afterlife reinforced the Egyptians theology in humans possessions a '']'', or life-force, which left the body at the point of death. In life, the ''ka'' received its sustenance from food and drink, so it was believed that, to endure after death, the ''ka'' must continue to receive offerings of food, whose spiritual essence it could still consume. Each person also had a '']'', the set of spiritual characteristics unique to each individual.{{Sfn | Allen | 2000 | pp = 79–80}} Unlike the ''ka'', the ''ba'' remained attached to the body after death. Egyptian funeral rituals were intended to release the ''ba'' from the body so that it could move freely, and to rejoin it with the ''ka'' so that it could live on as an '']''. However, it was also important that the body of the deceased be preserved by mummification, as the Egyptians believed that the ''ba'' returned to its body each night to receive new life, before emerging in the morning as an ''akh''.{{Sfn | Allen | 2000 | pp = 94–95}} | |||

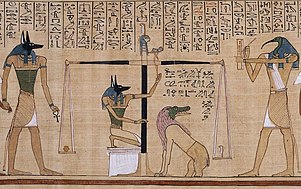

| ] wearing the feather of truth]] | |||

| According to John Tuthill, a professor at the University of Guam, Akhenaten's reasons for his religious reform were political. By the time of Akhenaten's reign, the god Amen had risen to such a high status that the priests of Amen had become even more wealthy and powerful than the pharaohs. However, it may be that Akhenaten was influenced by his family members, particularly his wife or mother (Dunham, 1963, p. 4; Mertz, 1966, p. 269). There was a certain trend in Akhenaten's family towards sun-worship. Towards the end of the reign of Akhenaten's father, Amenhotep III, the Aten was depicted increasingly often. Some historians have suggested that the same religious revolution would have happened even if Akhenaten had never become pharaoh at all. However, considering the violent reaction that followed shortly after Akhenaten's untimely death, this seems improbable. The reasons for Akhenaten's revolution still remain a mystery. Until further evidence can be uncovered, it will be impossible to know just what motivated his unusual behavior. | |||

| In early times the deceased pharaoh was believed to ].{{Sfn | Taylor | 2001 | p = 25}} Over the course of the ] ({{circa|2686}}–2181 BC), however, he came to be more closely associated with the daily rebirth of the sun god ] and with the underworld ruler Osiris as those deities grew more important.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 90, 94–95}} | |||

| In the fully developed afterlife beliefs of the New Kingdom, the soul had to avoid a variety of supernatural dangers in the Duat, before undergoing a final judgement, known as the "Weighing of the Heart", carried out by Osiris and by the ]. In this judgement, the gods compared the actions of the deceased while alive (symbolized by the heart) to the feather of Ma'at, to determine whether he or she had behaved in accordance with Ma'at. If the deceased was judged worthy, his or her ''ka'' and ''ba'' were united into an ''akh''.{{Sfn | Fleming | Lothian | 1997 | p = 104}} Several beliefs coexisted about the ''akh''{{'s}} destination. Often the dead were said to dwell in the realm of Osiris, a lush and pleasant land in the underworld.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 160–61}} The solar vision of the afterlife, in which the deceased soul traveled with Ra on his daily journey, was still primarily associated with royalty, but could extend to other people as well. Over the course of the Middle and New Kingdoms, the notion that the ''akh'' could also travel in the world of the living, and to some degree magically affect events there, became increasingly prevalent.{{Sfn | Assmann | 2005 | pp = 209–10, 398–402}} | |||

| After the fall of the Amarna dynasty, the original Egyptian ] survived more or less as the dominant faith, until the establishment of ] and later ], even though the Egyptians continued to have relations with the other monotheistic cultures (e.g. ]s). Egyptian mythology put up surprisingly little resistance to the spread of Christianity, sometimes explained by claiming that ] was originally a ] based predominantly on ], with ] and her worship becoming ] and ] (see ]). | |||

| == |

===Atenism=== | ||

| {{main |Atenism}} | |||

| Many temples are still standing today. Others are in ruins from wear and tear, while others have been lost entirely. Pharaoh ] was a particularly prolific builder of temples. | |||

| ] | |||

| During the New Kingdom the pharaoh ] abolished the official worship of other gods in favor of the sun-disk ]. This is often seen as the first instance of true monotheism in history, although the details of Atenist theology are still unclear and the suggestion that it was monotheistic is disputed. The exclusion of all but one god from worship was a radical departure from Egyptian tradition and some see Akhenaten as a practitioner of ] or ] rather than monotheism,<ref>{{Citation | first = Dominic | last = Montserrat | author-link = Dominic Montserrat | title = Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt | publisher = Routledge | year = 2000 | isbn = 0-415-18549-1 | pages = 36ff}}.</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Najovits|first=Simson|title= Egypt, trunk of the tree | volume = 2 |year=2003|publisher=Algora|isbn=978-0-87586-256-9|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UrR848g3gp8C&pg=PA88 |pages=131–44}}</ref> as he did not actively deny the existence of other gods; he simply refrained from worshipping any but the Aten. Under Akhenaten's successors Egypt reverted to its traditional religion, and Akhenaten himself came to be reviled as a heretic.{{Sfn | Dunand | Zivie-Coche | 2005 | p = 35}}{{Sfn | Allen | 2000 | p = 198}} | |||

| ==Writings== | |||

| Some known temples include: | |||

| {{see also|Ancient Egyptian literature}} | |||

| While the Egyptians had no unified religious scripture, they produced many religious writings of various types. Together the disparate texts provide an extensive, but still incomplete, understanding of Egyptian religious practices and beliefs.{{Sfn | Traunecker | 2001 | pp = 1–5}} | |||

| ===Mythology===<!--This section is linked from ]--> | |||

| * ] – Complex of two massive rock temples in southern Egypt on the western bank of the Nile. | |||

| {{main |Egyptian mythology}} | |||

| * ] (Great Temple of Abydos) – Adoration of the early kings, whose cemetery, to which it forms a great funerary chapel, lies behind it. | |||

| ] (at center) travels through the underworld in his barque, accompanied by other gods{{Sfn |Wilkinson |2003 | pp = 222–223}}]] | |||

| * ] (]) – Could have served as the city center of El Qasr. It was probably built around the 26th Dynasty. | |||

| Egyptian myths were stories intended to illustrate and explain the gods' actions and roles in nature. The details of the events they recounted could change to convey different symbolic perspectives on the mysterious divine events they described, so many myths exist in different and conflicting versions.{{Sfn | Tobin | 2001 | pp = 464–68}} Mythical narratives were rarely written in full, and more often texts only contain episodes from or allusions to a larger myth.{{Sfn | Pinch | 1995 | p = 18}} Knowledge of Egyptian mythology, therefore, is derived mostly from hymns that detail the roles of specific deities, from ritual and magical texts which describe actions related to mythic events, and from funerary texts which mention the roles of many deities in the afterlife. Some information is also provided by allusions in secular texts.{{Sfn | Traunecker | 2001 | pp = 1–5}} Finally, Greeks and Romans such as ] recorded some of the extant myths late in Egyptian history.{{Sfn | Fleming | Lothian | 1997 | p = 26}} | |||

| * ] – Once part of the ancient capital of Egypt, ]. | |||

| * ] – Located in Middle Egypt near to Al-Minya and survived the reconstruction of the New Kingdom. | |||

| * ] – ] temple that is located between Aswan and Luxor. | |||

| * ] – Controlled the trade routes from Nubia to the Nile Valley. | |||

| * ] – Built largely by Amenhotep III and Ramesses II, it was the centre of the ]. | |||

| * ] (Memorial Temple of Ramesses III)– Temple and a complex of temples dating from the New Kingdom. | |||

| * ] – Mortuary temple complex at Deir el-Bahri with a colonnaded structure of perfect harmony, built nearly one thousand years before the Parthenon. | |||

| * ] – Island of Philae with Temple of Aset which was constructed in the 30th Dynasty. | |||

| * ] (Memorial Temple of Ramesses II) – The main building, dedicated to the funerary cult, comprised two stone pylons (gateways, some 60 m wide), one after the other, each leading into a courtyard. Beyond the second courtyard, at the centre of the complex, was a covered 48-column hypostyle hall, surrounding the inner sanctuary. | |||

| * ] – Several temples but the all overshadowing building in the complex is the main temple, the ]. | |||

| Among the significant Egyptian myths were the ]. According to these stories, the world emerged as a dry space in the ] of chaos. Because the sun is essential to life on earth, the first rising of Ra marked the moment of this emergence. Different forms of the myth describe the process of creation in various ways: a transformation of the primordial god ] into the elements that form the world, as the creative speech of the intellectual god ], and as an act of the hidden power of Amun.{{Sfn | Allen | 2000 | pp = 143–45, 171–73, 182}} Regardless of these variations, the act of creation represented the initial establishment of Ma'at and the pattern for the subsequent cycles of time.<ref name="Shafer 2"/>]. Isis, in the form of a bird, copulates with the deceased Osiris. At either side are Horus, although he is as yet unborn, and Isis in human form.{{sfn|Meeks|Favard-Meeks|1996|p=37}}]]The most important of all Egyptian myths was the ].{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | p = 124}} It tells of the divine ruler Osiris, who was murdered by his jealous brother ], a god often associated with chaos.{{Sfn | Fleming | Lothian | 1997 | pp = 76, 78}} Osiris' sister and wife ] resurrected him so that he could conceive an heir, Horus. Osiris then entered the underworld and became the ruler of the dead. Once grown, Horus fought and defeated Set to become king himself.{{Sfn | Quirke | Spencer | 1992 | p = 67}} Set's association with chaos, and the identification of Osiris and Horus as the rightful rulers, provided a rationale for pharaonic succession and portrayed the pharaohs as the upholders of order. At the same time, Osiris' death and rebirth were related to the Egyptian agricultural cycle, in which crops grew in the wake of the Nile inundation, and provided a template for the resurrection of human souls after death.{{Sfn | Fleming | Lothian | 1997 | pp = 84, 107–108}} | |||

| == External influences == | |||

| Egypt exchanged ideas with ] during its early unsettled period. Egypt was also influenced by the Greek ], which ruled Egypt for 300 years. ] was the only Ptolemaic queen to rule on her own. Egypt was incorporated into the Roman Empire, and was ruled first from Rome and then from Constantinople (until the Arab conquest). | |||

| Another important mythic motif was the journey of Ra through the Duat each night. In the course of this journey, Ra met with Osiris, who again acted as an agent of regeneration, so that his life was renewed. He also fought each night with ], a serpentine god representing chaos. The defeat of Apep and the meeting with Osiris ensured the rising of the sun the next morning, an event that represented rebirth and the victory of order over chaos.{{Sfn | Fleming | Lothian | 1997 | pp = 33, 38–39}} | |||

| ;Libyan period | |||

| ''Main article'': ]<br /> | |||

| ''22nd - 25th Dynasty'' | |||

| ===Ritual and magical texts=== | |||

| Egypt has long had ties with Libya. After the death of ], the priesthood in the person of ] wrest control of Egypt away from the Pharaohs until they were superseded (without any apparent struggle) by the Libyan kings of the ]. The first king of the new Dynasty, ], served as a general under the last ruler of the 21st Dynasty. It is known that he appointed his own son to be the High Priest of Amun, a post that was previously a hereditary appointment. The scant and patchy nature of the written records from this period suggest that it was unsettled. There appear to have been many subversive groups which eventually led to the creation of the ] which ran concurrent with the ]. | |||

| The procedures for religious rituals were frequently written on ], which were used as instructions for those performing the ritual. These ritual texts were kept mainly in the temple libraries. Temples themselves are also inscribed with such texts, often accompanied by illustrations. Unlike the ritual papyri, these inscriptions were not intended as instructions, but were meant to symbolically perpetuate the rituals even if, in reality, people ceased to perform them.{{Sfn | Dunand | Zivie-Coche | 2005 | pp = 93–99}} Magical texts likewise describe rituals, although these rituals were part of the spells used for specific goals in everyday life. Despite their mundane purpose, many of these texts also originated in temple libraries and later became disseminated among the general populace.{{Sfn | Pinch | 1995 | p = 63}} | |||

| ===Hymns and prayers=== | |||

| ;Ptolemaic period | |||

| The Egyptians produced numerous prayers and hymns, written in the form of poetry. Hymns and prayers follow a similar structure and are distinguished mainly by the purposes they serve. Hymns were written to praise particular deities.<ref name="Foster">{{Harvnb | Foster | 2001 | loc = vol. II, pp. 312–17}}.</ref> Like ritual texts, they were written on papyri and on temple walls, and they were probably recited as part of the rituals they accompany in temple inscriptions.{{Sfn | Dunand | Zivie-Coche | 2005 | p = 94}} Most are structured according to a set literary formula, designed to expound on the nature, aspects, and mythological functions of a given deity.<ref name="Foster"/> They tend to speak more explicitly about fundamental theology than other Egyptian religious writings, and became particularly important in the New Kingdom, a period of particularly active theological discourse.{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | p = 166}} Prayers follow the same general pattern as hymns, but address the relevant god in a more personal way, asking for blessings, help, or forgiveness for wrongdoing. Such prayers are rare before the New Kingdom, indicating that in earlier periods such direct personal interaction with a deity was not believed possible, or at least was less likely to be expressed in writing. They are known mainly from inscriptions on statues and ] left in sacred sites as ]s.<ref name="Ockinga">Ockinga, Boyo, "Piety", in {{Harvnb | Redford | 2001 | loc = vol. III, pp. 44–46}}.</ref> | |||

| ''Main article'': ]<br /> | |||

| ''304 BC - 30 BC'' | |||

| ===Funerary texts=== | |||

| Started with ] and ended with ]. As ] ("Saviour"), he founded the ], which was to rule Egypt for 300 years. All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name "Ptolemy". Because the Ptolemaic kings adopted the Egyptian custom of marrying their sisters, many of the kings ruled jointly with their spouses, who were also of the royal house. This custom made Ptolemaic politics confusingly incestuous, and the later Ptolemies were increasingly feeble. The last of the Ptolemies, the famous ], was the only Ptolemaic queen to rule on her own, after the death of her brother/husband, ]. | |||

| {{main|Ancient Egyptian funerary texts}} | |||

| ], depicting the Weighing of the Heart.]] | |||

| Among the most significant and extensively preserved Egyptian writings are ] designed to ensure that deceased souls reached a pleasant afterlife.{{Sfn | Allen | 2000 | p = 315}} The earliest of these are the ]. They are a loose collection of hundreds of spells inscribed on the walls of royal pyramids during the Old Kingdom, intended to magically provide pharaohs with the means to join the company of the gods in the afterlife.{{Sfn | Hornung | 1999 | pp = 1–5}} The spells appear in differing arrangements and combinations, and few of them appear in all of the pyramids.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | p = 93}} | |||

| At the end of the Old Kingdom a new body of funerary spells, which included material from the Pyramid Texts, began appearing in tombs, inscribed primarily on coffins. This collection of writings is known as the ], and was not reserved for royalty, but appeared in the tombs of non-royal officials.{{Sfn | Taylor | 2001 | pp = 194–95}} In the New Kingdom, several new funerary texts emerged, of which the best-known is the ]. Unlike the earlier books, it often contains extensive illustrations, or vignettes.{{Sfn | Hornung | 1999 | pp = xvii, 14}} The book was copied on papyrus and sold to commoners to be placed in their tombs.{{Sfn | Quirke | Spencer | 1992 | p = 98}} | |||

| ;Roman period | |||

| ''Main article'': ]<br /> | |||

| ''30 BC - 639 AD'' | |||

| The Coffin Texts included sections with detailed descriptions of the underworld and instructions on how to overcome its hazards. In the New Kingdom, this material gave rise to several "books of the netherworld", including the ], the ], and the ].{{Sfn | Allen | 2000 | pp = 316–17}} Unlike the loose collections of spells, these netherworld books are structured depictions of Ra's passage through the Duat, and by analogy, the journey of the deceased person's soul through the realm of the dead. They were originally restricted to pharaonic tombs, but in the Third Intermediate Period they came to be used more widely.{{Sfn | Hornung | 1999 | pp = 26–27, 30}} | |||

| Egypt was incorporated into the ] and was ruled first from ] and then from ] (until the Arab conquest). The most revolutionary event in the history of Roman Egypt was the introduction of ] in the 2nd century. It was at first vigorously persecuted by the Roman authorities, who feared religious discord more than anything else in a country where religion had always been paramount. But it soon gained adherents among the Jews of Alexandria. From them it rapidly passed to the Greeks, and then to the native Egyptians, who found its promise of personal salvation and its teachings of social equality appealing. | |||

| ==Practices== | |||

| ==Notes on pronunciation== | |||

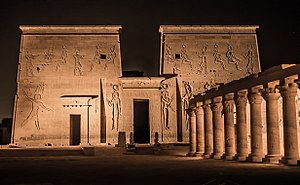

| ] and colonnade of the Temple of ] at ]]] | |||

| A "received pronunciation" of the names of ancient Egyptian deities has formed. By and large, this pronunciation is acceptable for most consonants and utterly wrong for the vowels. Egyptologists developed a set of conventions to make it easier to talk about the terms they used. Two distinct different glottal consonants were both replaced with "a". A consonant similar to the "y" in the English word "yet" was replaced with "i". A consonant similar to the "w" in the English word "well" was replaced with "u". Then, "e" was inserted between other consonants. Thus, for example, the Egyptian king whose name is most accurately transcribed as ''Rˁ-ms-sw'' is known as "Rameses", meaning "] has Fashioned (lit. "Borne") Him". | |||

| ===Temples=== | |||

| {{main|Egyptian temple}} | |||

| Temples existed from the beginning of Egyptian history, and at the height of the civilization they were present in most of its towns. They included both ]s to serve the spirits of deceased pharaohs and temples dedicated to patron gods, although the distinction was blurred because divinity and kingship were so closely intertwined.<ref name= "Shafer 2"/> The temples were not primarily intended as places for worship by the general populace, and the common people had a complex set of religious practices of their own. Instead, the state-run temples served as houses for the gods, in which physical images which served as their intermediaries were cared for and provided with offerings. This service was believed to be necessary to sustain the gods, so that they could in turn maintain the universe itself.<ref name="Wilkinson 42">{{Harvnb | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 42–44}}.</ref> Thus, temples were central to Egyptian society, and vast resources were devoted to their upkeep, including both donations from the monarchy and large estates of their own. Pharaohs often expanded them as part of their obligation to honor the gods, so that many temples grew to enormous size.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2000 | pp = 8–9, 50}} However, not all gods had temples dedicated to them, as many gods who were important in official theology received only minimal worship, and many household gods were the focus of popular veneration rather than temple ritual.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2000 | p = 82}} | |||

| The earliest Egyptian temples were small, impermanent structures, but through the Old and Middle Kingdoms their designs grew more elaborate, and they were increasingly built out of stone. In the New Kingdom, a basic temple layout emerged, which had evolved from common elements in Old and Middle Kingdom temples. With variations, this plan was used for most of the temples built from then on, and most of those that survive today adhere to it. In this standard plan, the temple was built along a central processional way that led through a series of courts and halls to the sanctuary, which held a statue of the temple's god. Access to this most sacred part of the temple was restricted to the pharaoh and the highest-ranking priests. The journey from the temple entrance to the sanctuary was seen as a journey from the human world to the divine realm, a point emphasized by the complex mythological symbolism present in temple architecture.{{Sfn | Dunand | Zivie-Coche | 2005 | pp = 72–82, 86–89}} Well beyond the temple building proper was the outermost wall. Between the two lay many subsidiary buildings, including workshops and storage areas to supply the temple's needs, and the library where the temple's sacred writings and mundane records were kept, and which also served as a center of learning on a multitude of subjects.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2000 | pp = 72–75}} | |||

| Theoretically it was the duty of the pharaoh to carry out temple rituals, as he was Egypt's official representative to the gods. In reality, ritual duties were almost always carried out by priests. During the Old and Middle Kingdoms, there was no separate class of priests; instead, many government officials served in this capacity for several months out of the year before returning to their secular duties. Only in the New Kingdom did professional priesthood become widespread, although most lower-ranking priests were still part-time. All were still employed by the state, and the pharaoh had final say in their appointments.{{sfn|Shafer|1997|p=9}} However, as the wealth of the temples grew, the influence of their priesthoods increased, until it rivaled that of the pharaoh. In the political fragmentation of the ] ({{circa|1070}}–664 BC), the high priests of Amun at ] even became the effective rulers of ].{{sfn|Wilkinson|2000|pp= 9, 25–26}} The temple staff also included many people other than priests, such as musicians and chanters in temple ceremonies. Outside the temple were artisans and other laborers who helped supply the temple's needs, as well as farmers who worked on temple estates. All were paid with portions of the temple's income. Large temples were therefore very important centers of economic activity, sometimes employing thousands of people.{{sfn|Wilkinson | 2000 | pp = 92–93}} | |||

| ===Official rituals and festivals=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| State religious practice included both temple rituals involved in the cult of a deity, and ceremonies related to divine kingship. Among the latter were ] and the ], a ritual renewal of the pharaoh's strength that took place periodically during his reign.<ref name="Thompson">Thompson, Stephen E., "Cults: Overview", in Redford 2001, vol. I, 326–332</ref> There were numerous temple rituals, including rites that took place across the country and rites limited to single temples or to the temples of a single god. Some were performed daily, while others took place annually or on rare occasions.<ref name="Wilkinson 95">{{harvnb|Wilkinson | 2000|p= 95}}</ref> The most common temple ritual was the morning offering ceremony, performed daily in temples across Egypt. In it, a high-ranking priest, or occasionally the pharaoh, washed, anointed, and elaborately dressed the god's statue before presenting it with offerings. Afterward, when the god had consumed the spiritual essence of the offerings, the items themselves were taken to be distributed among the priests.<ref name="Thompson" /> | |||

| The less frequent temple rituals, or festivals, were still numerous, with dozens occurring every year. These festivals often entailed actions beyond simple offerings to the gods, such as reenactments of particular myths or the symbolic destruction of the forces of disorder.<ref>{{harvnb|Dunand|Zivie-Coche|2005|pp= 93–95}}; {{harvnb|Shafer| 1997| p= 25}}</ref> Most of these events were probably celebrated only by the priests and took place only inside the temple.<ref name="Wilkinson 95"/> However, the most important temple festivals, like the ] celebrated at Karnak, usually involved a procession carrying the god's image out of the sanctuary in a model barque to visit other significant sites, such as the temple of a related deity. Commoners gathered to watch the procession and sometimes received portions of the unusually large offerings given to the gods on these occasions.{{sfn|Shafer| 1997| pp= 27–28}} | |||

| ===Animal cults=== | |||

| ] | |||

| At many sacred sites, the Egyptians worshipped individual animals which they believed to be manifestations of particular deities. These animals were selected based on specific sacred markings which were believed to indicate their fitness for the role. Some of these cult animals retained their positions for the rest of their lives, as with the ] worshipped in Memphis as a manifestation of Ptah. Other animals were selected for much shorter periods. These cults grew more popular in later times, and many temples began raising stocks of such animals from which to choose a new divine manifestation.{{sfn|Dunand|Zivie-Coche |2005| pp = 21, 83}} A separate practice developed in the ], when people began mummifying any member of a particular animal species as an offering to the god whom the species represented. Millions of mummified ]s, birds, and other creatures were buried at temples honoring Egyptian deities.{{sfn|Quirke | Spencer| 1992| pp = 78, 92–94}}<ref name=Owen2004>{{Cite journal| title = Egyptian Animals Were Mummified Same Way as Humans| url = https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/09/0915_040915_petmummies.html| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20040917002041/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/09/0915_040915_petmummies.html| url-status = dead| archive-date = September 17, 2004| year = 2004| author = Owen, James| journal = National Geographic News| access-date = 2010-08-06}}</ref> Worshippers paid the priests of a particular deity to obtain and mummify an animal associated with that deity, and the mummy was placed in a cemetery near the god's cult center. | |||

| ===Oracles=== | |||

| The Egyptians used ]s to ask the gods for knowledge or guidance. Egyptian oracles are known mainly from the New Kingdom and afterward, though they probably appeared much earlier. People of all classes, including the king, asked questions of oracles.<ref>Kruchten, Jean-Marie, "Oracles", in {{harvnb|Redford| 2001| pp= 609–611}}</ref> The most common means of consulting an oracle was to pose a question to the divine image while it was being carried in a festival procession, and interpret an answer from the barque's movements. Other methods included interpreting the behavior of cult animals, drawing lots, or consulting statues through which a priest apparently spoke. The means of discerning the god's will gave great influence to the priests who spoke and interpreted the god's message.{{sfn|Frankfurter| 1998| pp= 145–152}} | |||

| ===Popular religion=== | |||

| While the state cults were meant to preserve the stability of the Egyptian world, lay individuals had their own religious practices that related more directly to daily life.{{sfn|Sadek| 1988| pp= 1–2}} This popular religion left less evidence than the official cults, and because this evidence was mostly produced by the wealthiest portion of the Egyptian population, it is uncertain to what degree it reflects the practices of the populace as a whole.<ref name="Wilkinson 46">{{harvnb|Wilkinson| 2003| pp= 46}}</ref> | |||

| Popular religious practice included ceremonies marking important transitions in life. These included birth, because of the danger involved in the process, and ], because the name was held to be a crucial part of a person's identity. The most important of these ceremonies were those surrounding death, because they ensured the soul's survival beyond it.{{sfn|Dunand | Zivie-Coche| 2005| pp= 128–131}} Other religious practices sought to discern the gods' will or seek their knowledge. These included the interpretation of dreams, which could be seen as messages from the divine realm, and the consultation of oracles. People also sought to affect the gods' behavior to their own benefit through magical rituals.<ref>Baines, in {{harvnb|Shafer| 1991| pp= 164–171}}</ref> | |||

| Individual Egyptians also prayed to gods and gave them private offerings. Evidence of this type of personal piety is sparse before the New Kingdom. This is probably due to cultural restrictions on depiction of nonroyal religious activity, which relaxed during the Middle and New Kingdoms. Personal piety became still more prominent in the late New Kingdom, when it was believed that the gods intervened directly in individual lives, punishing wrongdoers and saving the pious from disaster.<ref name="Ockinga"/> Official temples were important venues for private prayer and offering, even though their central activities were closed to laypeople. Egyptians frequently donated goods to be offered to the temple deity and objects inscribed with prayers to be placed in temple courts. Often they prayed in person before temple statues or in shrines set aside for their use.<ref name="Wilkinson 46"/> Yet in addition to temples, the populace also used separate local chapels, smaller but more accessible than the formal temples. These chapels were very numerous and probably staffed by members of the community.<ref>Lesko, Barbara S. "Cults: Private Cults", in Redford 2001, vol. I, pp. 336–339</ref> Households, too, often had their own small shrines for offering to gods or deceased relatives.{{sfn|Sadek |1988| pp= 76–78}} | |||

| The deities invoked in these situations differed somewhat from those at the center of state cults. Many of the important popular deities, such as the fertility goddess ] and the household protector ], had no temples of their own. However, many other gods, including Amun and Osiris, were very important in both popular and official religion.{{sfn|David| 2002| pp= 273, 276–277}} Some individuals might be particularly devoted to a single god. Often they favored deities affiliated with their own region, or with their role in life. The god ], for instance, was particularly important in his cult center of ], but as the patron of craftsmen he received the nationwide veneration of many in that occupation.{{sfn|Traunecker| 2001| p= 98}} | |||

| ===Magic=== | |||

| {{main|Heka_(god)|l1=Heka}} | |||

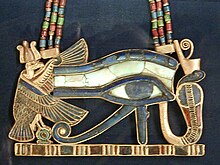

| ], a common magical symbol]] | |||

| The word "''magic''" is normally used to translate the Egyptian term ''heka'', which meant, as ] puts it, "the ability to make things happen by indirect means".{{sfn|Allen| 2000| pp= 156–157}} | |||

| ''Heka'' was believed to be a natural phenomenon, the force which was used to create the universe and which the gods employed to work their will. Humans could also use it, and magical practices were closely intertwined with religion. In fact, even the regular rituals performed in temples were counted as magical.{{Sfn | Pinch | 1995 | pp = 9–17}} Individuals also frequently employed magical techniques for personal purposes. Although these ends could be harmful to other people, no form of magic was considered inimical in itself. Instead, magic was seen primarily as a way for humans to prevent or overcome negative events.<ref>Baines, in {{Harvnb | Shafer | 1991 | p = 165}}.</ref> | |||

| Magic was closely associated with the priesthood. Because temple libraries contained numerous magical texts, great magical knowledge was ascribed to the ]s, who studied these texts. These priests often worked outside their temples, hiring out their magical services to laymen. Other professions also commonly employed magic as part of their work, including doctors, scorpion-charmers, and makers of magical amulets. It is also possible that the peasantry used simple magic for their own purposes, but because this magical knowledge would have been passed down orally, there is limited evidence of it.{{Sfn | Pinch | 1995 | pp = 51–63}} | |||

| Language was closely linked with ''heka'', to such a degree that ], the god of writing, was sometimes said to be the inventor of ''heka''.{{Sfn | Pinch | 1995 | pp = 16, 28}} Therefore, magic frequently involved written or spoken incantations, although these were usually accompanied by ritual actions. Often these rituals invoked an appropriate deity to perform the desired action, using the power of ''heka'' to compel the deity to act. Sometimes this entailed casting the practitioner or subject of a ritual in the role of a character in mythology, thus inducing the god to act toward that person as it had in the myth. | |||

| Rituals also employed ], using objects believed to have a magically significant resemblance to the subject of the rite. The Egyptians also commonly used objects believed to be imbued with ''heka'' of their own, such as the magically protective ]s worn in great numbers by ordinary Egyptians.{{Sfn | Pinch | 1995 | pp = 73–78}} | |||

| ===Funerary practices=== | |||

| {{main |Ancient Egyptian funerary practices}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Because it was considered necessary for the survival of the soul, preservation of the body was a central part of Egyptian funerary practices. Originally the Egyptians buried their dead in the desert, where the arid conditions ] the body naturally. In the Early Dynastic Period, however, they began using tombs for greater protection, and the body was insulated from the ] effect of the sand and was subject to natural decay. Thus, the Egyptians developed their elaborate ] practices, in which the corpse was artificially desiccated and wrapped to be placed in its coffin.{{Sfn | Quirke | Spencer | 1992 | pp = 86–90}} The quality of the process varied according to cost, however, and those who could not afford it were still buried in desert graves.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 300–1}} | |||

| Once the mummification process was complete, the mummy was carried from the deceased person's house to the tomb in a funeral procession that included his or her relatives and friends, along with a variety of priests. Before the burial, these priests performed several rituals, including the ] intended to restore the dead person's senses and give him or her the ability to receive offerings. Then the mummy was buried and the tomb sealed.{{Sfn | Taylor | 2001 | pp = 187–93}} Afterwards, relatives or hired priests gave food offerings to the deceased in a nearby mortuary chapel at regular intervals. Over time, families inevitably neglected offerings to long-dead relatives, so most mortuary cults only lasted one or two generations.{{Sfn | Taylor | 2001 | p = 95}} However, while the cult lasted, the living sometimes wrote letters asking deceased relatives for help, in the belief that the dead could affect the world of the living as the gods did.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | p = 282}} | |||

| The first Egyptian tombs were ]s, rectangular brick structures where kings and nobles were entombed. Each of them contained a subterranean burial chamber and a separate, above ground chapel for mortuary rituals. In the Old Kingdom the mastaba developed into the ], which symbolized the primeval mound of Egyptian myth. Pyramids were reserved for royalty, and were accompanied by large mortuary temples sitting at their base. Middle Kingdom pharaohs continued to build pyramids, but the popularity of mastabas waned. Increasingly, commoners with sufficient means were buried in ]s with separate mortuary chapels nearby, an approach which was less vulnerable to tomb robbery. By the beginning of the New Kingdom even the pharaohs were buried in such tombs, and they continued to be used until the decline of the religion itself.{{Sfn | Taylor | 2001 | pp = 141–55}} | |||

| Tombs could contain a great variety of other items, including statues of the deceased to serve as substitutes for the body in case it was damaged.{{Sfn | Fleming | Lothian | 1997 | pp = 100–1}} Because it was believed that the deceased would have to do work in the afterlife, just as in life, burials often included ] to do work in place of the deceased.{{Sfn | Taylor | 2001 | pp = 99–103}} ]s found in early royal tombs were probably meant to serve the pharaoh in his afterlife.<ref>Sergio Donadoni, ''The Egyptians'', (Chicago: ], 1997) p. 262</ref> | |||

| The tombs of wealthier individuals could also contain furniture, clothing, and other everyday objects intended for use in the afterlife, along with amulets and other items intended to provide magical protection against the hazards of the spirit world.{{Sfn | Taylor | 2001 | pp = 107–10, 200–13}} Further protection was provided by funerary texts included in the burial. The tomb walls also bore artwork, such as images of the deceased eating food that were believed to allow him or her to magically receive sustenance even after the mortuary offerings had ceased.{{Sfn | Quirke | Spencer | 1992 | pp = 97–98, 112}} | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ===Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods=== | |||

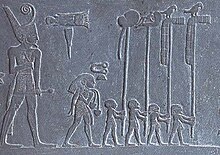

| ], a Predynastic ruler, accompanied by men carrying the standards of various local gods]] | |||

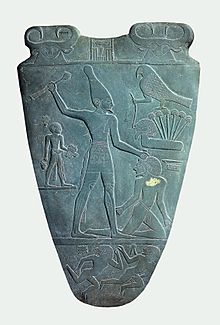

| ]. The face of a woman with the horns and ears of a cow, representing ] or Hathor, appears twice at the top of the palette, and a falcon representing Horus appears to the right of the palette.]] | |||

| The beginnings of Egyptian religion extend into prehistory, though evidence for them comes only from the sparse and ambiguous archaeological record. Careful burials during the ] imply that the people of this time believed in some form of an afterlife.<ref>{{citation needed|date=December 2023}}</ref> At the same time, animals were ritually buried, a practice which may reflect the development of ] deities like those found in the later religion.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 12–15}} The evidence is less clear for gods in human form, and this type of deity may have emerged more slowly than those in animal shape. Each region of Egypt originally had its own patron deity, but it is likely that as these small communities conquered or absorbed each other, the god of the defeated area was either incorporated into the other god's mythology or entirely subsumed by it. This resulted in a complex pantheon in which some deities remained only locally important while others developed more universal significance.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | p = 31}}{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 50–52}} | |||

| Archaeological data has suggested that the Egyptian religious system had close, cultural affinities with Eastern African populations and arose from an African substratum rather than deriving from the Mesopotamian or Mediterranean regions.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Smith |first1=Stuart Tyson |title=Gift of the Nile? Climate Change, the Origins of Egyptian Civilization and Its Interactions within Northeast Africa |journal=Across the Mediterranean – Along the Nile: Studies in Egyptology, Nubiology and Late Antiquity Dedicated to László Török. Budapest |date=1 January 2018 |url=https://www.academia.edu/43275151}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title="Egyptian Religion" in Macropedia, Vol. 6 Encyclopedia Britannica |pages=506–508 |edition=1984}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Frankfort |first1=Henri |title=Kingship and the gods : a study of ancient Near Eastern religion as the integration of society & nature |date=1978 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |location=Chicago |isbn=0226260119 |pages=161–223 |edition=Phoenix}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Manzo |first1=Andrea |title=Ancient Egypt in its African context : economic networks, social and cultural interactions |date=2022 |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-1009074544 |pages=1–50}}</ref> | |||

| The ] began with the unification of Egypt around 3000 BC. This event transformed Egyptian religion, as some deities rose to national importance and the cult of the divine pharaoh became the central focus of religious activity.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | p = 15}} Horus was identified with the king, and his cult center in the Upper Egyptian city of ] was among the most important religious sites of the period. Another important center was ], where the early rulers built large funerary complexes.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2000 | pp = 17–19}} | |||

| ===Old and Middle Kingdoms=== | |||

| During the ], the priesthoods of the major deities attempted to organize the complicated national pantheon into groups linked by their mythology and worshipped in a single cult center, such as the ] of ], which linked important deities such as ], Ra, Osiris, and ] in a single creation myth.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 51, 81–85}} Meanwhile, pyramids, accompanied by large mortuary temple complexes, replaced ]s as the tombs of pharaohs. In contrast with the great size of the pyramid complexes, temples to gods remained comparatively small, suggesting that official religion in this period emphasized the cult of the divine king more than the direct worship of deities. The funerary rituals and architecture of this time greatly influenced the more elaborate temples and rituals used in worshipping the gods in later periods.{{Sfn | Dunand | Zivie-Coche | 2005 | pp = 78–79}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The Ancient Egyptians regarded the sun as a powerful life force. The sun god Ra had been worshipped from the Early Dynastic period (3100–2686 BCE), but it was not until the Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BCE), when Ra became the dominant figure in the Egyptian pantheon, that the Sun Cult took power.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Strudwick|first=Helen|title=The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt|publisher=Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.|year=2006|isbn=978-1-4351-4654-9|location=New York|pages=108–111}}</ref> Early in the Old Kingdom, Ra grew in influence, and his cult center at Heliopolis became the nation's most important religious site.<ref>{{Harvnb | Malek | 2000 | pp = 92–93, 108–9}}.</ref> By the ], Ra was the most prominent god in Egypt and had developed the close links with kingship and the afterlife that he retained for the rest of Egyptian history.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 90–91, 112}} Around the same time, ] became an important afterlife deity. The ], first written at this time, reflect the prominence of the solar and Osirian concepts of the afterlife, although they also contain remnants of much older traditions.<ref>{{Harvnb | Malek | 2000 | p = 113}}.</ref> The texts are an extremely important source for understanding early Egyptian theology.{{sfn|David| 2002| p= 92}} | |||

| Symbols such as the 'winged disc' took on new features. Originally, the solar disk with the wings of a hawk was originally the symbol of Horus and associated with his cult in the Delta town of Behdet. The sacred cobras were added on either side of the disc during the Old Kingdom. The winged disc had protective significance and was found on temple ceilings and ceremonial entrances. | |||

| In the 22nd century BC, the Old Kingdom collapsed into the disorder of the ]. Eventually, rulers from ] reunified the Egyptian nation in the ] ({{circa|2055}}–1650 BC). These Theban pharaohs initially promoted their patron god ] to national importance, but during the Middle Kingdom, he was eclipsed by the rising popularity of ].{{Sfn | David | 2002 | p = 154}} In this new Egyptian state, personal piety grew more important and was expressed more freely in writing, a trend that continued in the New Kingdom.<ref name = "Shaw 180">Callender, Gae, "The Middle Kingdom", in {{Harvnb | Shaw | 2000 | pp = 180–81}}.</ref> | |||

| ===New Kingdom=== | |||

| The Middle Kingdom crumbled in the ] ({{circa|1650}}–1550 BC), but the country was again reunited by Theban rulers, who became the first pharaohs of the ]. Under the new regime, ] became the supreme state god. He was syncretized with Ra, the long-established patron of kingship and his ] in Thebes became Egypt's most important religious center. Amun's elevation was partly due to the great importance of Thebes, but it was also due to the increasingly professional priesthood. Their sophisticated theological discussion produced detailed descriptions of Amun's universal power.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 181–84, 186}}{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | pp = 166, 191–92}} | |||

| Increased contact with outside peoples in this period led to the adoption of many Near Eastern deities into the pantheon. At the same time, the subjugated ]ns absorbed Egyptian religious beliefs, and in particular, adopted Amun as their own.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 276, 304}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The New Kingdom religious order was disrupted when ] acceded, and replaced Amun with the ] as the state god. Eventually, he eliminated the official worship of most other gods and moved Egypt's capital to a new city at ]. This part of Egyptian history, the ], is named after this. In doing so, Akhenaten claimed unprecedented status: only he could worship the Aten, and the populace directed their worship toward him. The Atenist system lacked well-developed mythology and afterlife beliefs, and the Aten seemed distant and impersonal, so the new order did not appeal to ordinary Egyptians.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 215–18, 238}} Thus, many probably continued to worship the traditional gods in private. Nevertheless, the withdrawal of state support for the other deities severely disrupted Egyptian society.{{Sfn | Van Dijk | 2000 | pp = 287, 311}} Akhenaten's successors restored the traditional religious system, and eventually, they dismantled all Atenist monuments.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 238–39}} | |||

| Before the Amarna Period, popular religion had trended toward more personal relationships between worshippers and their gods. Akhenaten's changes had reversed this trend, but once the traditional religion was restored, there was a backlash. The populace began to believe that the gods were much more directly involved in daily life. Amun, the supreme god, was increasingly seen as the final arbiter of human destiny, the true ruler of Egypt. The pharaoh was correspondingly more human and less divine. The importance of oracles as a means of decision-making grew, as did the wealth and influence of the oracles' interpreters, the priesthood. These trends undermined the traditional structure of society and contributed to the breakdown of the New Kingdom.{{Sfn | Van Dijk | 2000 | pp = 289, 310–12}}<ref>{{Citation | last = Assmann | title = State and Religion in the New Kingdom}}, in {{Harvnb | Simpson | 1989 | pp = 72–79}}.</ref> | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| ===Later periods=== | |||

| {{further|Decline of ancient Egyptian religion}} | |||

| {{further|Roman Egypt}} | |||

| ]'' stances (])]] | |||

| ] statue of Isis holding a sistrum and a situla]] | |||

| In the 1st millennium BC, Egypt was significantly weaker than in earlier times, and in several periods foreigners seized the country and assumed the position of pharaoh. The importance of the pharaoh continued to decline, and the emphasis on popular piety continued to increase. Animal cults, a characteristically Egyptian form of worship, became increasingly popular in this period, possibly as a response to the uncertainty and foreign influence of the time.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 312–17}} Isis grew more popular as a goddess of protection, magic, and personal salvation, and became the most important goddess in Egypt.{{Sfn | Wilkinson | 2003 | pp = 51, 146–49}} | |||

| In the 4th century BC, Egypt became a ] kingdom under the ] (305–30 BC), which assumed the pharaonic role, maintaining the traditional religion and building or rebuilding many temples. The kingdom's Greek ruling class identified the Egyptian deities with their own.{{Sfn | Peacock | 2000 | pp = 437–38}} From this cross-cultural syncretism emerged ], a god who combined Osiris and Apis with characteristics of Greek deities, and who became very popular among the Greek population. Nevertheless, for the most part the two belief systems remained separate, and the Egyptian deities remained Egyptian.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | pp = 325–28}} | |||

| Ptolemaic-era beliefs changed little after Egypt became a ] of the ] in 30 BC, with the Ptolemaic kings replaced by distant emperors.{{Sfn | Peacock | 2000 | pp = 437–38}} The cult of Isis appealed even to Greeks and Romans outside Egypt, and in Hellenized form it spread across the empire.{{Sfn | David | 2002 | p = 326}} In Egypt itself, as the empire weakened, official temples fell into decay, and without their centralizing influence religious practice became fragmented and localized. Meanwhile, ] spread across Egypt, and in the third and fourth centuries AD, edicts by Christian emperors and the missionary activity of Christians eroded traditional beliefs. | |||

| Nevertheless, the traditional Egyptian religion persisted for a long time. The traditional worship in the temples of the city of ] apparently survived at least until the 5th century, despite the active Christianization of Egypt. In fact, the fifth-century historian ] mentions a treaty between the Roman commander Maximinus and the Blemmyes and Nobades in 452, which among other things ensured access to the ] of Isis.<ref name=UCLA>{{Cite encyclopedia|last=Holger|first=Kockelmann|date=2012-04-24|title=Philae|url=http://escholarship.org/uc/item/1456t8bn#page-2|editor-last=Wendrich|editor-first=Willeke|display-editors=etal|encyclopedia=UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology|language=en|volume=1|issue=1}}</ref><ref name=OxfordEncyclopedia>{{cite encyclopedia|last=Lloyd|first=Alan B.|title=Philae|editor-last=Redford|editor-first=Donald|encyclopedia=The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt|volume=3|pages=40–44|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|year=2001|isbn=0-19-513823-6}}</ref><ref name=monasticism>{{cite book|last=Moawad|first=Samuel|section=Christianity on Philae| editor1-last=Gabra|editor1-first=Gawdat|editor1-link=Gawdat Gabra|editor2-last=Takla|editor2-first=Hany N.|title=Christianity and Monasticism in Aswan and Nubia|series=Christianity and Monasticism in Egypt|publisher=American University in Cairo Press|location=Cairo|year=2013|pages=27–38|isbn=978-977-416-561-0}}</ref> | |||

| According to the 6th-century historian ], the temples in Philae was closed down officially in AD 537 by the local commander ] the Persarmenian in accordance with an order of ] ].<ref>] ''Bell. Pers.'' 1.19.37</ref> This event is conventionally considered to mark the end of ancient Egyptian religion.<ref name="Fletcher_2015_History_Weekend">{{cite AV media | |||

| | people=Joann Fletcher | |||

| | year=2016 | |||

| | title=The amazing history of Egypt | |||

| | medium=podcast | |||

| | url=http://www.historyextra.com/podcast/history-Egypt-Joann-Fletcher | |||

| | access-date=17 Jan 2016 | |||

| | format=MP3 | |||

| | time=53:46 | |||

| | publisher=BBC History Magazine | |||

| }}</ref> However, its importance has recently come into question, following a major study by Jitse Dijkstra who argues that organized paganism at Philae ended in the fifth century, based on the fact that the last inscriptional evidence of an active pagan priesthood there dates to the 450s.<ref name=UCLA/><ref name=monasticism/> Nevertheless, some adherence to traditional religion seems to have survived into the sixth century, based on a petition from ] to the governor of the ] dated to 567.<ref name=Justinian>{{cite journal| last=Dijkstra|first=Jitse H.F.|title=A Cult of Isis at Philae after Justinian? Reconsidering 'P. Cair. Masp.' I 67004|journal=Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik|year=2004|volume=146|pages=137–154|jstor=20191757}}</ref><ref name=monasticism/> The letter warns of an unnamed man (the text calls him "eater of raw meat") who, in addition to plundering houses and stealing tax revenue, is alleged to have restored paganism at "the sanctuaries", possibly referring to the temples at Philae.<ref name=Justinian/><ref name=monasticism/> | |||

| While it persisted among the populace for some time, Egyptian religion slowly faded away.{{Sfn | Frankfurter | 1998 | pp = 23–30}}<gallery widths="170" heights="170"> | |||

| File:Sousse mosaic calendar November.JPG|] in the November panel of a Roman mosaic calendar from Sousse, Tunisia | |||

| File:Pompeii - Temple of Isis - Io and Isis - MAN.jpg|Isis (seated right) welcoming the Greek ] into Egypt, depicted on the southern wall of the Ekklesiasterion | |||

| File:Casa degli Amorini Dorati. Fresco. 09.JPG|Anubis, ], ] and ], antique fresco in ], ] | |||

| File:Statue of the god Anubis.jpg|Statue of Hermanubis from Rome | |||

| File:Wien KHM Isis I 158.jpg|Roman black and white marble statue of Isis | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Legacy=== | |||

| Egyptian religion produced the temples and tombs which are ancient Egypt's most enduring monuments, but it also influenced other cultures. In pharaonic times many of its symbols, such as the ] and ], were adopted by other cultures across the Mediterranean and Near East, as were some of its deities, such as ]. Some of these connections are difficult to trace. The Greek concept of ] may have derived from the Egyptian vision of the afterlife.{{Sfn | Assmann | 2001 | p = 392}} In late antiquity, the Christian conception of ] was most likely influenced by some of the imagery of the Duat. Egyptian beliefs also influenced or gave rise to several ] belief systems developed by Greeks and Romans, who considered Egypt as a source of mystic wisdom. ], for instance, derived from the tradition of secret magical knowledge associated with ].{{Sfn | Hornung | 2001 | pp = 1, 9–11, 73–75}} | |||