| Revision as of 19:07, 24 September 2006 view sourceTherealmikelvee (talk | contribs)726 edits →Chronologies Synchronizing the Exodus with the Expulsion of the Hyksos← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:47, 5 December 2024 view source Ermenrich (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers22,392 edits →In Christianity: see https://www.wheaton.edu/academics/faculty/michael-graves/ | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Founding myth of the Jewish people}} | |||

| :''The article ] discusses the events related in the book of the ] and ] by the same name.'' | |||

| {{About|the events related in the Bible|the second book of the Bible|Book of Exodus|other uses|Exodus (disambiguation){{!}}Exodus}} | |||

| '''The Exodus''', more fully '''The Exodus of Israel out of Egypt''', was the departure of the ] ]s from ] under the leadership of ] and ] as described in the biblical Book of ]. It forms the basis of the Jewish holiday of ]. See also ]. | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

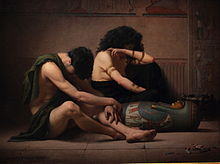

| ], 1829)]] | |||

| '''The Exodus''' (]: יציאת מצרים, ''Yəṣīʾat Mīṣrayīm'': {{Lit|Departure from Egypt}}{{efn|The name "exodus" is from ] ἔξοδος ''exodos'', "going out",}}) is the ]{{efn|{{Myth FAQ}}}} of the ] whose narrative is spread over four of the five books of the ] (specifically, ], ], ], and ]). The narrative of the Exodus describes a history of Egyptian bondage of the Israelites followed by their exodus from Egypt through a ], in pursuit of the ] under the leadership of ]. | |||

| The consensus of modern scholars is that the Pentateuch does not give an accurate account of the origins of the Israelites, who appear instead to have formed as an entity in the central highlands of ] in the late second millennium BCE (around the time of the ]) from the indigenous Canaanite culture.{{sfn|Grabbe|2017|p=36}}{{sfn|Meyers|2005|pp=6–7}}{{sfn|Moore|Kelle|2011|p=81}} Most modern scholars believe that some elements in the story of the Exodus might have some historical basis, but that any such basis has little resemblance to the story told in the Pentateuch.<ref name="Grabbe2017">Sources for 'most scholars' or 'consensus':{{Bulleted list|{{harvnb|Grabbe|2017|p=36|ps=: "The impression one has now is that the debate has settled down. Although they do not seem to admit it, the minimalists have triumphed in many ways. That is, most scholars reject the historicity of the 'patriarchal period', see the settlement as mostly made up of indigenous inhabitants of Canaan and are cautious about the early monarchy. The exodus is rejected or assumed to be based on an event much different from the biblical account. On the other hand, there is not the widespread rejection of the biblical text as a historical source that one finds among the main minimalists. There are few, if any, maximalists (defined as those who accept the biblical text unless it can be absolutely disproved) in mainstream scholarship, only on the more fundamentalist fringes."}}<!--|{{cite news | first=Ze'ev | last=Herzog | title=Deconstructing the walls of Jericho | newspaper=Ha'aretz | url=http://websites.umich.edu/~proflame/neh/arch.htm | access-date=13 January 2022 | date=29 October 1999|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20210811064225/http://websites.umich.edu/~proflame/neh/arch.htm|archivedate=11 August 2021}}-->|{{Cite web|url=http://lib1.library.cornell.edu/colldev/mideast/jerques.htm|title=Deconstructing the walls of Jericho|publisher=]|date=29 October 1999|accessdate=9 February 2019|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20011110114548/http://lib1.library.cornell.edu/colldev/mideast/jerques.htm|first1=Ze'ev|last1=Herzog|authorlink=Ze'ev Herzog|work=lib1.library.cornell.edu|archivedate=10 November 2001}}|{{cite book | editor-last1=Skolnik | editor-first1=Fred | editor-last2=Berenbaum | editor-first2=Michael | editor3=Thomson Gale (Firm) | title=Encyclopaedia Judaica | year=2007 | isbn=978-0-02-866097-4 | oclc=123527471 | url=http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/70174939.html | access-date=29 November 2019 | first1=Moshe | last1=Greenberg | first2=S. David | last2=Sperling | chapter=Exodus, Book of. | edition=2nd | quote=Current scholarly consensus based on archaeology holds the enslavement and exodus traditions to be unhistorical. | volume=6 | pages=612–623 | chapter-url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/philosophy-and-religion/bible/old-testament/exodus}}|{{cite journal |last1=Pfoh |first1=Emanuel |title=UNA DECONSTRUCCIÓN DEL PASADO DE ISRAEL EN EL ANTIGUO ORIENTE: HACIA UNA NUEVA HISTORIA DE LA ANTIGUA PALESTINA |journal=Estudios de Asia y África |date=September–December 2010 |volume=45 |issue=3 (143) |pages=669–697 |publisher=El Colegio De Mexico |location=Ciudad de México |doi=10.24201/eaa.v45i3.1995 |language=es |issn=0185-0164 |jstor=i25822397 |s2cid=161105175 |quote=Históricamente, no podemos hablar más de un periodo de los Patriarcas, del Éxodo de los israelitas de Egipto, de la conquista de Canaán, de un periodo de los Jueces en Palestina, ni de una Monarquía Unida dominando desde el Éufrates hasta el Arco de Egipto.<sup>31</sup> Incluso la historicidad del Exilio de los israelitas de Palestina hacia Babilonia como un evento único ha sido puesta en seria duda recientemente.<sup>32</sup><!--<br><br><sup>31</sup> Cf. Th. L. Thompson, ''Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written and Archaeological Sources,'' Studies in the History of the Ancient Near East, 4, Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1992, pp. 10-116, 146-158, 215-300, 401412; N. P. Lemche, "Early Israel Revisited", ''Currents in Research: Biblical Studies,'' vol. 4, 1996, pp. 9-34, y ''The Israelites in History and Tradition,'' Library of Ancient Israel, Louisville, wjk, 1998, pp. 35 85; I. Finkelstein y N. A. Silberman, ''The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision on Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts,'' Nueva York, Free Press, 2001, pp. 27-96, 123-145. Vease tambien Liverani, ''Oltre la Bibbia. Storia antica di Israele,'' Roma-Bari, Laterza, 2003, y ''Recenti tendenze nella ricostruzione della storia antica d'Israele,'' Roma, Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 2005.<br><br><sup>32</sup> L. L. Grabbe (ed.), ''Leading Captivity Captive: "The Exile" as History and Ideology,'' Journal for the Study of the Old Testament - Supplement Series, 278/European Seminar in Historical Methodology, 2, Sheffield, Sheffield Academic Press, 1998.-->}}}}</ref>{{sfn|Faust|2015|page=476}}{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=87}} While the majority of modern scholars date the composition of the Pentateuch to the period of the ] (5th century BCE), some of the elements of this narrative are older, since allusions to the story are made by 8th-century BCE ] such as ] and ].{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=87}}{{sfn|Lemche|1985|p=327}} | |||

| ==Biblical narrative== | |||

| The ] had moved from the land of ] into ] when ] was prime minister of Egypt. After the death of Joseph and a change in rulership, the Egyptians were now suspicious of the Israelites, particularly because they had begun to greatly increase in number. The Egyptians enslaved the Israelites for four hundred years. | |||

| The story of the Exodus is central in ]. It is recounted daily in ] and celebrated in festivals such as ]. Early Christians saw the Exodus as a ] prefiguration of ] and ] by ]. The Exodus is also recounted in the ] as part of the extensive referencing of the ], a major prophet in Islam. The narrative has also resonated with various groups in more recent centuries, such as among the early American settlers fleeing religious persecution in Europe, and among ] striving for freedom and ].{{sfn|Tigay|2004}}{{sfn|Baden|2019|p=xiv}} | |||

| This work, particularly the brickmaking, was extremely rigorous and the conditions oppressively harsh. ], in exile from Egypt at the time, was called or felt impelled to become a leader. Returning to Egypt he attempted to negotiate with the ], who was not receptive, saying he did not know Moses' God. Moses, under God's instruction, called forth a series of ten plagues. Eventually Pharaoh agreed to the Israelites' request for Moses to lead the Israelites out of Egypt. | |||

| ==In the Bible== | |||

| However the Pharaoh changed his mind soon after they left, and sent soldiers after the Israelites to bring them back. In a miraculous escape the Israelites crossed over a "sea" which had dried out, with the water standing up on both sides of them like a wall. Once the Israelites had crossed the sea, the water returned and caught the following Egyptians as they tried to turn back, as the Lord had caused their chariots to swerve. | |||

| The Exodus tells a story of the ] of the Israelites, the ], the departure of the Israelites from Egypt, the revelations at ], and the Israelite wanderings in the wilderness up to the borders of ].{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=59}} Its message is that the Israelites were delivered from slavery by ] their god, and therefore belong to him by ].{{sfn|Sparks|2010|p=73}} | |||

| ===Narrative=== | |||

| After their departure from Egypt, the Israelites traveled through an itinerary of perhaps 40 locations. The modern counterparts of many of the places at the beginning of the list are unknown or disputed. Significant events occurred at these early locations or 'stations', including the giving of the ] at ], along with the remainder of Mosaic law. The Israelites finally arrive at a site which may have been located, Kadesh-Barnea. Spies eyed ] as a prospect for invasion, but although ] and ] returned with optimistic reports, the other ten tribal leaders advised that an invasion not be attempted. All this seemed to happen in the first year, as the accounts says the Wandering took place when Moses was between the ages of 80 and 120: "Israel was thereupon sentenced to wander forty years in the wilderness" (Nu. 14:34). (Note that as manna had just been introduced, Ex. 16:35 does not imply the forty years to have happened previously, but is a forward-looking statement.) Moses then led the Israelites through the remainder of a series of encampments known to scholars as the ] for the afore-mentioned forty years. Only the descendants of the generation present at the start of the forty years, along with Joshua and Caleb, would be able to cross into Canaan proper; an action which ultimately culminated in the beginning of the Conquest of Canaan with the crossing of the ] from the East. | |||

| ], 1867)]] | |||

| The story of the Exodus is told in the first half of Exodus, with the remainder recounting the 1st year in the wilderness, and followed by a narrative of 39 more years in the books of Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, the last four of the first five books of the Bible (also called the Torah or Pentateuch).{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=59}} In the first book of the Pentateuch, the ], the Israelites had come to live in Egypt in the ] during a famine, under the protection of an Israelite, ], who had become a high official in the court of the Egyptian ]. Exodus begins with the death of Joseph and the ascension of a new pharaoh "who did not know Joseph" (Exodus 1:8).{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=59}} | |||

| The pharaoh becomes concerned by the number and strength of the Israelites in Egypt and enslaves them, commanding them to build at two "supply" or "store cities" called ] and ] (Exodus 1:11).{{efn|A "store city" or "supply city" was a city used to store provisions and garrison an important campaign route.{{sfn|Assmann|2018|p=94}} The ] version includes a reference to a third "supply city" built by the Hebrews: " On, which is ]" (LXX Exodus 1:11, trans. Larry J. Perkins{{sfn|Pietersma|Wright|2014}}{{sfn|Dozeman|Shectman|2016|p=139}}).}} The pharaoh also orders the slaughter at birth of all male Hebrew children. One Hebrew child, however, is rescued and abandoned in a floating basket on the ]. He is found and adopted by ], who names him ]. Grown to a young man, Moses kills an Egyptian he sees beating a Hebrew slave, and takes refuge in to the land of ], where he marries ], a daughter of the Midianite priest ]. The old pharaoh dies and a new one ascends the throne.{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=59}} | |||

| ==Route of the Exodus== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| There are a number of possible routes the Exodus might have taken. Many of the listed places are not identifiable with their modern day counterparts, and the information present in Exodus and related texts do not present a lot of unambiguous information regarding geographical landmarks. The itinerary that the Israelites followed after their departure from Egypt is given in both narrative form and in itinerary form. A few of the cities at the start of the itinerary, such as ], ] and ], are reasonably well identified, and the journey's second half consists of more well known places. ] is presumably found, but it was reported that its earliest occupation during the Ramesside era was centuries too late even for a Late Exodus. Although the biblical Mt. Sinai is most frequently depicted as Jebel Musa in the south of the Sinai Peninsula, no definitive evidence of the Exodus has as yet been found there, and even Sinai's location is not widely agreed upon by scholars. Dozens, if not hundreds of routes of the Exodus have been proposed; and where many of the stops in the Itinerary are located depends in no small part on where one wishes to locate Sinai and/or Horeb. | |||

| According to Ezekiel 20:8-9, the enslaved Israelites also practised "abominations" and worshiped the gods of Egypt. This provoked Yahweh to destroy them but he relented to avoid his name being "profaned".<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024 |title=Ezekiel 20 Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges |url=https://biblehub.com/commentaries/cambridge/ezekiel/20.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240201071610/https://biblehub.com/commentaries/cambridge/ezekiel/20.htm |archive-date=February 1, 2024 |website=Biblehub.com}}</ref> | |||

| The ] has been variously placed at the Pelusic branch of the Nile, anywhere along the network of Bitter Lakes and smaller canals that formed a barrier toward westward escape, or even the Gulf of Suez (SSE of Succoth) and the Gulf of Aqaba (S of Ezion-Geber). It is apparent from scriptural usage of the "Red Sea", lit. ''Yam Suf'', i.e. the "Sea of Reeds", that the term was used to refer to both the Gulf of Aqaba and the Gulf of Suez, but the meaning of the term can be easily read to refer to a papyrus marsh in Egypt as well. | |||

| Meanwhile, Moses goes to ], where Yahweh appears in a ] and commands him to go to Egypt to free the Hebrew slaves and bring them to the ] in Canaan. Yahweh also speaks to Moses's brother ], and the two assemble the Israelites and perform miraculous signs to rouse their belief in Yahweh's promise. Moses and Aaron then go to Pharaoh and ask him to let the Israelites go into the desert for a religious festival, but he refuses and increases their workload, commanding them to make ]. Moses and Aaron return to Pharaoh and ask him to free the Israelites and let them depart. Pharaoh demands Moses to perform a ], and Aaron throws down ], which turns into a {{lang|he|tannin|italics=yes}} (sea monster{{sfn|Dozeman|Shectman|2016|p=149}} or snake) (Exodus 7:8-13); however, Pharaoh's magicians{{efn|These magicians are referred to in the Hebrew text as {{lang|he|ḥartummîm|italics=yes}}, which derives from ] {{lang|egy|ḥrj-tp|italic=yes}} (] {{lang|egy|p-hritob|italics=yes}}, {{langx|akk|ḥar-tibi|italic=yes}}) a title meaning "chief" and shortened from "chief lector priest".{{sfn|Assmann|2018|p=139}} The Pharaoh's magicians are able to replicate Moses and Aaron's actions until the third plague (gnats), when they are the first to recognize that a divine power is at work (Exodus 8:19). In plague four (festering boils), they themselves are afflicted and no longer contest with Moses and Aaron.{{sfn|Assmann|2018|pp=139-142}}}} are also able to do this, though Moses' serpent devours the others. Pharaoh refuses to let the Israelites go. | |||

| Some of the more prominent routes for travelers through the region were the royal roads, the "king's highways" that had been in use for centuries, and would continue in use for centuries as well. The Bible specifically denies that the Israelites went the Way of the Philistines (Ex. 13:17), but even so, some scholars suggest a more northerly route along a land bridge adjoining the Mediterranean. As the warfare with the Philistines was a concern for the Israelites, however, and given the flat denial of the northern highway, an Exodus route that crosses this land bridge seems unlikely — especially considering the military situation that might present itself by being trapped between two hostile forces at either end. Beitak also describes a line of Egyptian forts along this King's Highway, known both from Egyptian texts and archaeology, which would most likely principally aide persuers. Pi-Hahiroth, (e.g. Ex. 14:2,7), is interpreted as the "mouth of the canal", but since Pi- may also be the Egyptian word for royal city, we might look for an Egyptian rather than a Semitic root for this name. Thus far, no satisfactory Egyptian root has been proposed, and so the Semitic translation may be correct. It should be pointed out, however, that canals connecting to a number of lakes may meet this description, so we should not press its localization too far until other nearby parts of the routes are more secure. This leaves the Way of Shur and the Way to Seir as probable routes, the former having the advantage of heading toward Kadesh-Barnea. Finally, various southern routes, all incorporating very similar suggestions for site locations, are notable due to their popularity, and the association of Jebal Musa with Mt. Sinai, an identification only known to go back to the Third Century CE. There also would have been some doubling back involved just beflre leaving Egypt, in addition to merely following the main highways. Three possible crossing routes at the Bitter Lakes are shown, and the Gulf of Aqaba is another popular candidate, but this crossing is not shown for the sake of clarity. | |||

| ] (1877)]] | |||

| On the map at the upper right, three of the important highways and the traditional southern route are shown. | |||

| After this, Yahweh inflicts a series of ] on the Egyptians each time Moses repeats his demand and Pharaoh refuses to release the Israelites. Pharaoh's magicians are able to match the first plagues, in which Yahweh turns the Nile to blood and produces a plague of frogs, but they cannot match any plagues starting with the third, the plague of ]s.{{sfn|Assmann|2018|pp=139-142}} After each plague, Pharaoh asks the Israelites to worship Yahweh to remove the plague, then still refuses to free them. | |||

| *The Way of Shur: (blue line) This route has the advantage of leading to Kadesh-Barnea, a stop on the Itinerary which has probably, but not necessarily been identified. (A turn back toward Kadesh-Barnea is also indicated with this line, which is not part of the Way of Shur.) | |||

| *The Way to Seir: (green line) This could be regarded as an Exodus route after crossing e.g. at the Bitter Lakes, or as part of a scenario placing the crossing at the Gulf of Aqaba. A number of theories, with some support from Deu. 1:2, place Mt. Sinai variously at ] or Jebel al-Lawz in ]. However, note that Nu. 21:4 is most comfortably read as having Mt. Hor and Sinai west of Ezion Geber. | |||

| *The southern route: (black line) This is the traditional route, which is based on the identification of Jebel Musa as Sinai in the third century AD (prompting the construction of St. Catherine's monastery at the time), and on the various suggestions for otherwise unknown stops on the Itinerary. Two lines lead eastward and northward, to show possible continuations to the conquest of the Transjordan. | |||

| Moses is commanded to fix the ] of ] at the head of the ]. He instructs the Israelites to take a lamb on the 10th day, and on the 14th day to slaughter it and daub its blood on their ] and ]s, and to observe the Passover meal that night, the night of the ]. In the ], Yahweh sends an angel to each house to kill the firstborn son and firstborn cattle, but the houses of the Israelites are spared by the blood on their doorposts. Yahweh commands the Israelites to commemorate this event in "a perpetual ordinance" (Exodus 12:14).{{sfn|Redmount|2001|pp=59-60}} | |||

| A summary of some of the many Exodus routes as proposed by various scholars can be found at: | |||

| Pharaoh finally casts the Israelites out of Egypt after his firstborn son is killed. Yahweh leads the Israelites in the form of a ] in the day and a ] at night. However, once the Israelites have left, Yahweh "hardens" Pharaoh's heart to change his mind and pursue the Israelites to the shore of the ]. Moses uses his staff to ], and the Israelites cross on dry ground, but the sea closes on the pursuing Egyptians, drowning them all.{{sfn|Redmount|2001|pp=59-60}} | |||

| ==Numbers involved in the Exodus== | |||

| The Biblical account in ] 12:37 refers to 600,000 adult Hebrew men as leaving Egypt and travelling with Moses. According to many Jewish sources, the total number of ] (including women and children) numbered around three million. The exodus also included ''droves of livestock''. | |||

| ] | |||

| Estimates of population suggest that Egypt might have supported around 3-4 million people during that period, maybe even up to 6 million (Robert Feather, ''The Copper Scroll Decoded'' and , , and ). Up to comparatively recent times, the population has not been excessive. ] estimated a population of 3 million when he invaded in 1798. Similarly, a simple calculation shows that a group of 3 million walking 10 abreast with 6 ft between rows would extend for around 340 miles (3,000,000 / 10 * 6 = 1,800,000 ft. = 340 mi.). Driving animals, taking children and elderly would probably have increased this distance. On the other hand, 600,000 men is the size of ] which was not so strung out. Also remarkable, are the textual implications that almost none (all but two) of the original 600,000 men lived to cross the Jordan. | |||

| The Israelites begin to complain, and Yahweh miraculously provides them with water and food, eventually raining ] down for them to eat. The ]ites attack at ], but are defeated. Jethro, the father-in-law of Moses, convinces him to appoint judges for the tribes of Israel. The Israelites reach the ] and Yahweh calls Moses to ], where Yahweh reveals himself to his people and establishes the ] and ]: the Israelites are to keep his ''torah'' (law, instruction), and Yahweh promises them the land of Canaan.{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=60}} | |||

| Yahweh establishes the ] and detailed rules for ritual worship, among other laws. However, in Moses's absence the Israelites sin against Yahweh by creating the idol of a ]. As punishment Yahweh has the ] kill three thousand of the Israelites (Exodus 32:28), and Yahweh sends a plague on them. The Israelites now accept the covenant, which is reestablished; they build a ] for Yahweh, and receive their laws. Yahweh commands Moses to take a ] of the Israelites and establishes the duties of the Levites. Then the Israelites depart from Mount Sinai.{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=60}} | |||

| Recent ] research has not been able to confirm the biblical account. Archaeologists have found no evidence that the Sinai desert ever hosted millions of people, nor of a massive population increase in ] during this time period. At this time the land is estimated to have had a population of between 50,000 and 100,000. Archaeologists, however, disagree greatly among themselves on timing, such as the conquest of Jericho, based on carbon dating and pottery shards, so they can not affirmatively disprove the Exodus. | |||

| Yahweh commands Moses to send ] ahead to Canaan to scout the land. The spies discover that the Canaanites are formidable, and to dissuade the Israelites from invading, the spies falsely report that Canaan is full of giants (Numbers 13:30-33). The Israelites refuse to go to Canaan, and Yahweh declares that the generation that left Egypt will have to pass away before the Israelites can enter the promised land. The Israelites will have to remain in the wilderness for forty years,{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=60}} and Yahweh kills the spies through a plague except for the righteous ] and ], who will be allowed to enter the promised land (Numbers 13:36-38). A group of Israelites led by ], son of Izhar, rebels against Moses, but Yahweh opens the earth and sends them living to ] (Numbers 16:1-33).{{sfn|Douglas|1993|pp=210}} | |||

| Archaeologists and secular historians have worked in the ] for many years to make an educated guess of approximately how many people lived in a given area at a given time. They do this by analyzing the evidence: buildings, trash, human waste product, skeletons, traces of ancient farms and fields, clothing, documents, and, of course, historical records. | |||

| The Israelites come to the oasis of ], where ] dies and the Israelites remain for nineteen years.{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=60}} To provide water, Yahweh commands Moses to get water from a rock by speaking to it, but Moses instead strikes the rock with his staff, for which Yahweh forbids him from entering the ]. Moses sends a messenger to the king of ] requesting passage through his land to Canaan, but the king refuses. The Israelites then go to ], where Aaron dies. The Israelites try to go around Edom, but the Israelites complain about lack of bread and water, so Yahweh sends a plague of poisonous snakes to afflict them (Numbers 21:4-7). | |||

| ] professor Abraham Malamat points out that the Bible often refers to 600 and its multiples, as well as 1,000 and its multiples, typologically in order to convey the idea of a large military unit. "The issue of Exodus 12:37 is an interpretive one. The Hebrew word ''eleph'' can be translated 'thousand,' but it is also rendered in the Bible as 'clans' and 'military units.' There are thought to have been 20,000 in the entire Egyptian army at the height of Egypt's empire. And at the battle of Ai in '']'' 7, there was a severe military setback when 36 troops were killed." Therefore if one reads ''alaphim'' (plural of ''eleph'') as military units, the number of Hebrew fighting men lay between 5,000 and 6,000. In theory, his would give a total Hebrew population of less than 20,000, something within the range of historical possibility. | |||

| After Moses prays for deliverance, Yahweh has him create a ], and the Israelites who look at it are cured (Numbers 21:8-9). The Israelites are soon in conflict with various other kingdoms, and king ] of ] asks the seer ] to curse the Israelites, but Balaam blesses them instead. Some Israelites begin having sexual relations with Moabite women and ], so Yahweh orders Moses to ] the idolators and sends another plague. The full extent of Yahweh's wrath is averted when ] impales ] and a ] having intercourse (Numbers 25:7-9). Yahweh commands the Israelites to destroy the Midianites, and Moses and Phinehas take another census. Then they conquer the lands of ] and ] in ], settling the ], ], and half the ] there. | |||

| However, at the same time of The Exodus, the total Hebrew population could conceivably involve fourteen ] of descendants of ], and thus easily 600,000. Under the famine conditions during Joseph's generation, it is conceivable that the number of immigrants to Egypt would have been substantial. | |||

| Moses then addresses the Israelites for a final time on the banks of the ], reviewing their travels and giving them further laws. Yahweh tells Moses to summon Joshua to lead the ]. Yahweh tells Moses to ascend ], from where he sees the Promised Land, and dies.{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=60}} | |||

| Some hold that one cannot interpret the counts given for each tribe in Numbers 1-2 in this fashion. They appear in units of "thousands", "hundreds" and "tens" and in addition the total appears. Thus, no interpretation of ''eleph'' except "thousand" makes sense in that case. However, the Hebrew Bible does not always use words precisely or consistently, precluding definitive proof either way. | |||

| ===Covenant and law=== | |||

| This by no means renders some kind of Exodus impossible. Some scholars suggest that it might not necessarily have happened in the numbers claimed. In the ], the Sinai region was much more lush and verdent than it is today, and could thus support more life. However the amount of grazing land and food needed for a migration of millions for decades at least strains credulity. The failure to find clear indications of this migration does not demonstrate that it did not happen, but the absence of evidence can be taken to have ''some'' significance. Part of the problem of finding evidence for this migration also involves a larger issue: the date of the Exodus is not known, and so it is unclear which layers might most likely represent any remnants of their migration. It is unclear if this means that a smaller migration might have given rise to the Exodus, that the migration should be sought at an unexpected time or that it happened in the numbers claimed but the evidence eludes us. One cannot conclude that it did not happen at all based on the difficulty with the large migration numbers. | |||

| The climax of the Exodus is the covenant (binding legal agreement) between God and the Israelites mediated by Moses at Sinai: Yahweh will protect the Israelites as his chosen people for all time, and the Israelites will keep Yahweh's laws and worship only him.{{sfn|Bandstra|2008|p=28-29}} The covenant is described in stages: at Exodus 24:3–8 the Israelites agree to abide by the "book of the covenant" that Moses has just read to them; shortly afterwards God writes the "words of the covenant" – the ] – on stone tablets; and finally, as the people gather in Moab to cross into the promised land of Canaan, Moses reveals Yahweh's new covenant "beside the covenant he made with them at Horeb" (Deuteronomy 29:1).{{sfn|McKenzie|2005|p=4–5}} The laws are set out in a number of codes:{{sfn|Bandstra|2008|p=146}} | |||

| * ] or Ten Commandments, Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5; | |||

| * The ], Exodus 20:22–23:3; | |||

| * ], Exodus 34; | |||

| * The ritual laws of ] 1–6 and ] 1–10; | |||

| * The ], Leviticus 17–26; | |||

| * Deuteronomic Code, ] 12–26. | |||

| == Origins and historicity == | |||

| Therefore, many scholars have questioned the Biblical numbers. In general, archaeologists hypothesize based on evidence available in locations. There are no other Exodus accounts in legend, inscriptions or steles currently available to dispute the numbers in the Hebrew Torah. | |||

| {{See also|Sources and parallels of the Exodus|Historicity of the Bible}} | |||

| There are two main positions on the historicity of the Exodus in modern scholarship.{{sfn|Grabbe|2017|p=36}} The majority position is that the biblical Exodus narrative has some historical basis, although there is little of historical fact in it.{{efn|"The biblical text has its own inner logic and consistency, largely divorced from the concerns of secular history. conversely, the Bible, never intended to function primarily as a historical document, cannot meet modern canons of historical accuracy and reliability. There is, in fact, remarkably little of proven or provable historical worth or reliability in the biblical Exodus narrative, and no reliable independent witnesses attest to the historicity or date of the Exodus events."{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=87}} }}{{sfn|Faust|2015|p=476}}{{sfn|Sparks|2010|p=73}} The other position, often associated with the school of ],{{sfn|Davies|2004|pp=23-24}}{{sfn|Moore|Kelle|2011|pp=86-87}} is that the biblical exodus traditions are the invention of the exilic and post-exilic Jewish community, with little to no historical basis.{{sfn|Russell|2009|p=11}} | |||

| The biblical Exodus narrative is best understood as a ] of the Jewish people, providing an ideological foundation for their culture and institutions, not an accurate depiction of the history of the Israelites.{{sfn|Collins|2005|p=46}}{{sfn|Sparks|2010|p=73}} The view that the biblical narrative is essentially correct unless it can explicitly be proved wrong (]) is today held by "few, if any in mainstream scholarship, only on the more fundamentalist fringes."{{sfn|Grabbe|2017|p=36}} There is no direct evidence for any of the people or events of Exodus in non-biblical ancient texts or in archaeological remains, and this has led most scholars to omit the Exodus events from comprehensive histories of Israel.{{sfn|Moore|Kelle|2011|p=88}} | |||

| == Dating the Exodus Overview == | |||

| In Exodus, ] is treated as a name rather than a title, and he is not otherwise named. Most prevailing theories fall into one of two categories: either was ] (1290-1223 or 1272-1213) that was the Pharaoh of the Oppression, or else the Exodus was earlier by centuries. ] (1490-1438 or 1479-1426 depending on the Egyptian dating scheme employed) is suggested by the date used by orthodox theologians, although nearby pharaohs are also used (e.g. ]; while other scholars in the modern era have taken up the idea to associate the Exodus expulsion of the ] again, making the pharaoh of the Oppression one of the Semitic Hyksos conquerors of Egypt. Note that the pharaoh of the Exodus need not necessarily be the same pharaoh the one for whom they built the Rameses and Pithom of Ex. 1:11, who need not necessarily be the same as the "pharaoh who knew not Joseph". | |||

| === Reliability of the biblical account === | |||

| There is little scholarly agreement as to even the century in which the Exodus should be placed. If one accepts the orthodox account, then from I Ki. 6:1, the conclusion is that the Exodus occurred 480 years before the founding of ]. Fortunately, only the Biblical Minimalist school of interpretation dissents significantly from the traditional date for Solomon's temple. The consensus of most experts places it in the range of 960-970 BCE. Using, for example, 966, we arrive at an Exodus date of 1446. This is unsatisfactory for three reasons: | |||

| Most mainstream scholars do not accept the biblical Exodus account as history for a number of reasons. Most agree that the Exodus stories were written centuries after the apparent setting of the stories.{{sfn|Moore|Kelle|2011|p=81}} Scholars argue that the ] itself attempts to ground the event firmly in history, reconstructing a date for the exodus as the 2666th year after creation (Exodus 12:40-41), the construction of the tabernacle to year 2667 (Exodus 40:1-2, 17), stating that the Israelites dwelled in Egypt for 430 years (Exodus 12:40-41), and specifying place names such as ] (Gen. 46:28), ], and ] (Exod. 1:11), as well as the count of 600,000 Israelite men (Exodus 12:37).{{sfn|Dozeman|Shectman|2016|pp=138-139}} | |||

| The ] further states that the number of Israelite males aged 20 years and older in the desert during the wandering was 603,550, which works out to a total population of 2.5-3 million including women and children—far more than could be supported by the ].{{sfn|Dever|2003|pp=18-19}} The geography is vague with regions such as Goshen unidentified,{{efn|It must be stated, however, that while there is no consensus on the identity of the ], some proposals for its original location have been advanced.{{sfn|Bietak|2022|p=153–154}}}} and there are internal problems with dating in the Pentateuch.{{sfn|Dozeman|Shectman|2016|p=139}} No modern attempt to identify a historical Egyptian as a prototype for Moses has found wide acceptance, and no period in Egyptian history matches the biblical accounts of the Exodus.{{sfn|Grabbe|2014|pp=63-64}} Some elements of the story are ] and defy rational explanation, such as the ] and the ].{{sfn|Dever|2003|pp=15-17}} The Bible does not mention the names of any of the pharaohs involved, further obscuring comparison of archaeologically recovered Egyptian history with the biblical narrative.{{sfn|Grabbe|2014|p=69}} | |||

| # The biblical chronology can readily be shown to be confused. The era of the Judges, when one adds their reigns, exceeds the time between the Exodus and Solomon's temple. The Apostle ], for his part, comes to a figure of 450 years for the Judges, the 40-year Wandering included (Acts 13:18.20), but still does not take into account the reign of the kings Saul and David. | |||

| # If one uses either the lower or the higher Egyptological dating schemes (although not so if a reductionist scheme is employed), 1446 falls in the reign of Thutmose III, who in archaeological records, is engaged in capturing Canaanite prisoners in battle and bringing them into Egypt, as opposed to the Pharaoh of the Exodus, who was concerned early on with the unbalanced proportion of Hebrew slaves, and | |||

| # The archaeology of the Conquest militates for a late Exodus. | |||

| While ]ian texts from the ] mention "Asiatics" living in Egypt as slaves and workers, these people cannot be securely connected to the Israelites, and no contemporary Egyptian text mentions a large-scale exodus of slaves like that described in the Bible.{{sfn|Barmash|2015b|pp=2-3}} The earliest surviving historical mention of the Israelites, the Egyptian ] ({{circa|1207 BCE}}), appears to place them in or around Canaan and gives no indication of any exodus.{{sfn|Grabbe|2014|pp=65-67}} Archaeologist ] argues from his analysis of the itinerary lists in the books of Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy that the biblical account represents a long-term cultural memory, spanning the 16th to 10th centuries BCE, rather than a specific event: "The beginning is vague and now untraceable."{{sfn|Finkelstein|2015|p=49}} Instead, modern archaeology suggests continuity between Canaanite and Israelite settlement, indicating a primarily Canaanite origin for Israel, with no suggestion that a group of foreigners from Egypt comprised early Israel.{{sfn|Barmash|2015b|p=4}}{{sfn|Shaw|2002|p=313}} | |||

| Currently, the destruction layer at ], at which a transition from Canaanite to proto-Israelite/] material culture is found, is dated from 1250-1150 BCE. (A Canaanite gate there is dated ca. 1155, but that city may have been razed subsequent to its completion.) A similar boundary at ] is dated to 1150, and at ], about 1145 BCE. Either these classic ] conquests happened at a much different time than the Bible suggests, or we must employ some exotic Egyptian chronology, even though it is relatively well understood, compared to Hebrew chronology and even Babylonian chronology. Other "Joshua" cities have transition layers around 1250 BCE. | |||

| === Potential historical origins === | |||

| One idea that has enjoyed occasional support among scholars ignores point three, and suggests that the Exodus should be associated with the expulsion of the ]. Indeed, this seems to have been the conclusion of classical writers such as ] and ]. The Hyksos were a Semitic people who ruled Egypt for roughly two centuries before the Eighteenth Dynasty. One cannot deny the possibility that the Hyksos might have been associated with the ] stock which seems to have given rise to the Hebrews of the Bible (although this link is not universally admitted), and indeed, the statement of Ex. 12:40 suggests that 400 years separated the arrival of Israelites in Egypt and the Exodus, thus tempting us to synchronize the arrival of ] in Egypt with the Hyksos. This, however, disregards the impossibility of synchronizing the end of the Hyksos era with the emergence of proto-Israelite material culture in Canaan, the earliest phases of which in the central highlands date to ca. 1400 BCE, but was not complete in the Judaite territories until at least 1250. Furthermore, the Hyksos left Egypt as defeated kings, not as escaping slaves. If we suppose the Israelites to have fled before then, we do not encounter any notice that their captors were soon overwhelmed, nor any notice that the Pharaoh they were slaves under was not actually an Egyptian, but Semitic like their selves. Placing the Exodus before the expulsion of the Hyksos only increases the difficulty of synchronizing the evidence with the arrival of proto-Israelite material culture in Canaan. Placing it shortly afterward does not allow for a very long Oppression, and also fails to explain why the Bible does not say that Pharaoh was not Egyptian for much of this time, or that the Egyptians had come back to power. | |||

| ], one of several ]]] | |||

| Despite the absence of any archaeological evidence, most scholars nonetheless hold that the Exodus probably has some sort of historical basis,{{sfn|Faust|2015|p=476}}{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=87}} with biblical scholar Kenton Sparks referring to it as "mythologized history".{{sfn|Sparks|2010|p=73}} Scholars posit that a small group of Egyptian origin may have joined the early Israelites, and contributed their own Egyptian Exodus story to all of Israel.{{efn|"While there is a consensus among scholars that the Exodus did not take place in the manner described in the Bible, surprisingly most scholars agree that the narrative has a historical core, and that some of the highland settlers came, one way or another, from Egypt..." "Archaeology does not really contribute to the debate over the historicity or even historical background of the Exodus itself, but if there was indeed such a group, it contributed the Exodus story to that of all Israel. While I agree that it is most likely that there was such a group, I must stress that this is based on an overall understanding of the development of collective memory and of the authorship of the texts (and their editorial process). Archaeology, unfortunately, cannot directly contribute (yet?) to the study of this specific group of Israel's ancestors."{{sfn|Faust|2015|p=476}}}} ] cautiously identifies this group with the ], while ] identifies it with the ].{{sfn|Dever|2003|p=231}}<ref>{{Cite book|last=Friedman|first=Richard Elliott|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_sbADQAAQBAJ|title=The Exodus|date=2017-09-12|publisher=HarperCollins|isbn=978-0-06-256526-6|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Most scholars who accept a historical core of the exodus date this possible exodus group to the thirteenth century BCE at the time of ] (]), with some instead dating it to the twelfth century BCE under ] (]).{{sfn|Faust|2015|p=476}} Evidence in favor of historical traditions forming a background to the Exodus myth include the documented movements of small groups of ] into and out of Egypt during the ] and 19th dynasties, some elements of Egyptian ] and culture mentioned in the Exodus narrative,{{sfn|Meyers|2005|pp=8-10}} and the names Moses, Aaron and Phinehas, which seem to have an Egyptian origin.{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=65}} Scholarly estimates for how many could have been involved in such an exodus range from a few hundred to a few thousand people.{{sfn|Faust|2015|p=476}} | |||

| Thus it is that there are two main categories that most Exodus theories fall into: Early and Late Exodus theories. Those requiring the veracity of I Ki. 6:1, or otherwise having an Exodus at or before ca. 1446 BCE (which include the many works by Bimson, who is not a fundamentalist, and more recently Redford and Herzog), are generally known as Early Exodus Theory supporters. Those maintaining that the building of the city of Rameses in Ex. 1:11 should be associated with Rameses II or later (Rameses I ruled for only a year or so), are termed supporters of a Late Exodus theory. ] began his reign ca. 1290-1272 (the Encyclopedias ''Americana'' and ''Britannia'' differ on Egyptological dating, and Bietak places them later yet), as opposed to the ca. 1446 BCE I Ki. 6:1 would require. Most archaeologists, for their part, if they believe the Exodus to be a historical event at all, support a late conquest of the "Joshua" cities, thus suggesting Rameses II as the Pharaoh of the Oppression. This fits well with the equation of the city of Rameses of Ex. 1:11 with the ] of archaeology; and Pithom with pi-Atum; both of which Egyptian documents from the time of Rameses II report construction on. Although Bietak reports finding remains from nearby Tell el-Dab'a from the time of the Hyksos (see below) until well after that of Thutmose III, he associates Pi-Rameses with Qantir instead of Tell el-Dab'a, but shows a hiatus at Qantir during the time of the traditional Exodus. It is widely held that this supports a Hyksos era or a Late Exodus better than a traditional Exodus date. Remains from Pithom are less helpful in narrowing the Exodus date down. | |||

| Joel S. Baden<ref>{{cite web |title=Joel S. Baden {{!}} Yale Divinity School |url=https://divinity.yale.edu/faculty-and-research/yds-faculty/joel-s-baden |website=divinity.yale.edu |access-date=30 March 2021 |language=en}}</ref> noted the presence of Semitic-speaking slaves in Egypt who sometimes escaped in small numbers as potential inspirations for the Exodus.{{sfn|Baden|2019|pp=6-7}} It is also possible that oppressive Egyptian rule of Canaan during the late second millennium BCE, during the 19th and especially the 20th dynasty, may have disposed some native Canaanites to adopt into their own mythology the exodus story of a small group of Egyptian refugees.{{sfn|Faust|2015|p=477}} Nadav Na'aman argues that oppressive Egyptian rule of Canaan may have inspired the Exodus narrative, forming a "]" of Egyptian oppression that was transferred from Canaan to Egypt itself in the popular consciousness.{{sfn|Na'aman|2011|pp=62-69}} The ] expulsion of the ], a group of Semitic invaders, is also frequently discussed as a potential historical parallel or origin for the story.{{sfn|Faust|2015|p=477}}{{sfn|Redmount|2001|p=78}}{{sfn|Redford|1992|pp=412–413}} | |||

| Alternate hypotheses concerning synchronizing the Exodus with volcanic eruptions are at least possible, but we are under no compulsion to require synchronization with any such eruption until we have at least isolated the correct century to search for the Exodus in. Some arguments try to demonstrate a date for the Exodus using astronomical or calendrical back-projections, so that the day the sun was claimed to have stood still over Gibeon might coincide with an eclipse, or the Exodus might coincide with a Jubilee. Sometimes these methods are used to try to prove something about when the Exodus was, but they cannot tell us what century the Exodus happened in. Rabbinical tradition typically tells a different version of events than that of the Bible. Typically, they speak of the Red Sea being divided up into twelve pieces; some in a miraculous context, but sometimes with no miraculous trappings at all. As the channels between the Bitter Lakes may have been silting up like the channel linking the Gulf of Suez to the Mediterannean had in the time of Rameses II, all we need do is imagine a brief drought which resulted in a silted up channel to have become dried up in one or more places in order to explain the received traditions. Although many theories are possible, while archaeology has demonstrated no evidence for any miracles, as details from Exodus evidently preserve memories from the Second Millennium BCE, Exodus theories most often fall into either a Traditional or Late Exodus theory category, while a minority of scholars either support a Hyksos Exodus, or else may be biblical Minimalists, who either deny the historicity of the traditions altogether, or else place them so late as to do require wholesale revisions to mainstream Egyptian and Israelite chronologies. | |||

| Many other scholars reject this view, and instead see the biblical exodus traditions as the invention of the ] and post-exilic Jewish community, with little to no historical basis.{{sfn|Russell|2009|p=11}} ], for instance, argues that "here is no compelling reason that the exodus has to be rooted in history",{{sfn|Grabbe|2014|p=84}} and that the details of the story more closely fit the seventh through the fifth centuries BCE than the traditional dating to the second millennium BCE.{{sfn|Grabbe|2014|p=85}} ] suggests that the story may have been inspired by the return to Israel of Israelites and Judaeans who were placed in Egypt as garrison troops by the ]ns in the fifth and sixth centuries BCE, during the exile.{{sfn|Davies|2015|p=105}} | |||

| ===Traditional Exodus Chronologies=== | |||

| The most natural point to begin seeking the date of the Exodus, in keeping with I Ki. 6:1, is some time within the decade surrounding ca. 1446 BCE. Thus, the Pharaoh of the Exodus would be a pharaoh such as ] (1490-1438 or 1479-1426, if using the chronology of the Encyclopedia Britannica or the Americana) or ] (1412-1428 or 1426-1400). Many attempts have been made to reconcile the biblical record with the archaeology of this time. Any Exodus date earlier than the time of Rameses II but later than the time of the Hyksos can be considered as part of this section. The vast majority of scholars who would place the Exodus in this range do so in the earlier part, and arguments both for and against are often similar. | |||

| ==Development and final composition== | |||

| What follows are some sites with scholars supporting such a traditional Exodus date. If you wish to add a site supporting an early Exodus, and you don't see it here, please make sure it does not belong in the ''Chronologies Synchronizing the Exodus with the Expulsion of the Hyksos'' section, below. | |||

| ===Early traditions=== | |||

| * | |||

| ], 1866)]] | |||

| * | |||

| The earliest traces of the traditions behind the exodus appear in the northern prophets ]<ref>{{Bibleverse|Amos|9:7}}</ref> and ],<ref>{{Bibleverse|Hosea|12:9}}</ref> both active in the 8th century BCE in northern ], but their southern contemporary ] shows no knowledge of an exodus.{{sfn|Lemche|1985|p=327}} ], who was active in the south around the same time, references the exodus once ({{Bibleverse|Micah|6:4-5}}), but it is debated whether the passage is an addition by a later editor.{{efn|Micah 6:4–5 ("I brought you up out of Egypt and redeemed you from the land of slavery; I sent Moses to lead you, also Aaron and Miriam. My people, remember what Balak king of Moab plotted and what Balaam son of Beor answered. Remember your journey from Shittim to Gilgal, that you may know the righteous acts of the Lord") is a late addition to the original book. See {{sfn|Lemche|1985|p=315}} {{cite book|first=Robert D.|last=Miller II|title=Illuminating Moses: A History of Reception from Exodus to the Renaissance|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bXZfAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA19|date=25 November 2013|publisher=BRILL|isbn=978-90-04-25854-9|page=19}}, {{cite book|first=John J.|last=McDermott|title=Reading the Pentateuch: A Historical Introduction|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Dkr7rVd3hAQC&pg=PA90|year=2002|publisher=Paulist Press|isbn=978-0-8091-4082-4|page=90}}, {{cite book|first=Steven L.|last=McKenzie|title=How to Read the Bible: History, Prophecy, Literature - Why Modern Readers Need to Know the Difference and What It Means for Faith Today|url=https://archive.org/details/howtoreadbiblehi00mcke_0|url-access=registration|date=2005|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-803655-5|page=}}, {{cite book|first=John J.|last=Collins|title=Introduction to the Hebrew Bible: Third Edition|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ju49DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA354|date=15 April 2018|publisher=Augsburg Fortress, Publishers|isbn=978-1-5064-4605-9|page=354|quote=Many scholars assume that the appeal to the exodus here is the work of a Deuteronomistic editor, but that is not necessarily so.}} and {{cite book|first=Hans Walter|last=Wolff|title=Micah: A Commentary|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=m-nlsvSZomcC|year=1990|publisher=Augsburg|isbn=978-0-8066-2449-5|page=23}} apud {{cite book|first=Graham R.|last=Hamborg|title=Still Selling the Righteous: A Redaction-critical Investigation of Reasons for Judgment in Amos 2.6-16|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=86OoAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA156|date=24 May 2012|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|isbn=978-0-567-04860-8|pages=156–157}}}} ], active in the 7th century, mentions both Moses<ref>{{Bibleverse|Jeremiah|15:1}}</ref> and the Exodus.<ref>{{Bibleref2|Jeremiah|16:14}}</ref> | |||

| *Here is a site that discusses various sociological models of the Conquest in light of archaeology, some of which may or may not by used in the context of an Early Exodus: . | |||

| *Some relatively recent archeological findings are said to suggest the Pharaoh of the Exodus was ] (around 1500 BCE): . | |||

| *A show on the Discovery and History Channels called ''The Exodus Decoded'' also supports this idea: . | |||

| The story may, therefore, have originated a few centuries earlier, perhaps in the 10th or 9th century BCE, and there are signs that it took different forms in Israel, in the ], and in the southern ] before being unified in the Persian era.{{sfn|Russell|2009|p=1}} The Exodus narrative was most likely further altered and expanded under the influence of the return from the ] in the sixth century BCE.{{sfn|Na'aman|2011|p=40}} | |||

| ''The Exodus Decoded'' has a number of intriguing ideas. More scholarly work needs to be done on parallels between the ] and the ], although it should be remembered that the ] can also make such a claim for parallels which are probably better, and it is thought to date from a far earlier era. We also cannot rule out that these might have served as literary models for the biblical plagues centuries after the fact. The steles the researchers claim depict the Exodus and Egyptians drowning in the sea are also interesting, even though it is not an open and shut case. Other points in this documentary may vanish on closer inspection. The figures on the top of the Ark of the covenant were not birds, as in the documentary, but ''cherebim'', i.e. in all probability winged figures with the body of a lion and the head of a human. Unlike the gold figurine they showed from Troy, the wings should also have been touching. The calcified deposits on top of the mountain are not necessarily of Ahmose I vintage, but until they are tested, might just as easily be from a spring running hundreds of thousands of years ago, before the mountain was a mountain. It would require radiocarbon dating to substantiate the claim that this calcium carbonate was of Ahmose I vintage, but access to the site is an issue also. Geologically, it is not unusual to find fossils from sea beds on the tops of mountains - a circumstance interpreted by evolutionists as the earth being billions of years old, while believers have it that these are remains from Noah's flood. | |||

| Evidence from the Bible suggests that the Exodus from Egypt formed a "foundational mythology" or "state ideology" for the ].{{sfn|Assmann|2018|p=50}} The northern psalms ] and ] state that God "brought a vine out of Egypt" (Psalm 80:8) and record ritual observances of Israel's deliverance from Egypt as well as a version of part of the ] (Psalm 81:10-11).{{sfn|Barmash|2015b|pp=10-12}} The ] records the dedication of two ] in ] and ] by the Israelite king ], who uses the words "Here are your gods, O Israel, which brought you up out of the land of Egypt" (1 Kings 12:28). Scholars relate Jeroboam's calves to the golden calf made by Aaron of Exodus 32. Both include a nearly identical dedication formula ("These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt", Exodus 32:8). This episode in Exodus is "widely regarded as a tendentious narrative against the Bethel calves".{{sfn|Russell|2009|p=41}} Egyptologist ] suggests that event, which would have taken place {{circa|931 BCE}}, may be partially historical due to its association with the historical pharaoh ] (the biblical ]).{{sfn|Assmann|2018|p=50}} Stephen Russell dates this tradition to "the eighth century BCE or earlier", and argued that it preserves a genuine Exodus tradition from the Northern Kingdom, but in a ] recension.{{sfn|Russell|2009|p=55}} Russell and Frank Moore Cross argue that the Israelites of the Northern Kingdom may have believed that the calves at Bethel and Dan were made by Aaron. Russell suggests that the connection to Jeroboam may have been later, possibly coming from a Judahite redactor.{{sfn|Russell|2009|pp=41-43, 46-47}} Pauline Viviano, however, concludes that neither the references to Jeroboam's calves in Hosea (Hosea 8:6 and 10:5) nor the frequent prohibitions of idol worship in the seventh-century southern prophet ] show any knowledge of a tradition of a golden calf having been created in Sinai.{{sfn|Viviano|2019|pp=46-47}} | |||

| The difficulties chronologies with Exodus dates near the traditional one face are considerable. Many archaeologists maintain that the Rameses and Pithom of Ex. 1:11 have been probably been identified, but the former was for the most part unoccupied during this period. During the reign of Horemheb, he had built the cities of Pi-Rameses and Pi-Tum under the supervision of ] (later Ramesses I), though a rather large addition was made to Pi-Ramesses and a small to Pi-Tum; most archaeologists make the equation between these and Rameses and Pithom. Originally, Pi-Rameses was thought to be at Tanis/Zoan, but then archaeologists noticed that some of the statuary had been relocated from Qantir to Tanis. Most archaeologists now place the ancient location of Pi-Rameses at Qantir. Some have also suggested Tell el-Dab'a, but Bietak places the core of Pi-Rameses at Qantir, which is just to its north; whereas he identifies Tell el-Daba with Avaris, the ancient capitol of the Hyksos. Although he has unearthed remains from the Eighteenth Dynasty at Tell el-Dab'a, these occur only a citadel at Ez-Helmi, within the area of Tell el-Daba. This citadel shows occupation from the time of the expulsion of the Hyksos to as late as Amenhotep II, while agricultural leveling has removed later traces. By contrast, he shows Qantir as being having an archaeological hiatus during the expected biblical Exodus date. | |||

| Some of the earliest evidence for Judahite traditions of the exodus is found in ], which portrays the Exodus as beginning a history culminating in the building of the temple at Jerusalem. Pamela Barmash argues that the psalm is a polemic against the Northern Kingdom; as it fails to mention that kingdom's destruction in 722 BCE, she concludes that it must have been written before then.{{sfn|Barmash|2015b|p=8-9}} The psalm's version of the Exodus contains some important differences from what is found in the Pentateuch: there is no mention of Moses, and the ] is described as "food of the mighty" rather than as bread in the wilderness.{{sfn|Barmash|2015b|p=9}} Nadav Na'aman argues for other signs that the Exodus was a tradition in Judah before the destruction of the northern kingdom, including the ] and ], as well as the great political importance that the narrative came to assume there.{{sfn|Na'aman|2011|p=40}}{{efn| However, the date of composition of the Song of the Sea - ostensibly celebrating the victory at the ] - ranges from an early mid-12th century BCE period through ], down to as late as 350 BCE.{{sfn |Russell|2007|p=96}}{{sfn|Cross|1997|p=124}}{{sfn|Brenner|2012|pp=1-20,15,19}}}} | |||

| While Pi-Atum is mentioned in writings of the time of Rameses II, its location may have been at either Tell el-Maskhuta or Tell el-Retabeh. Tell el-Maskhuta was at first thought to have been Pithom, owing to Ramesside era finds there, but as with Tanis, statues from the time of Rameses II seem to have been moved there at a later date. Based on a Roman mile marker which has been found, which says "9 miles on the road from Ero to Clysma ", a distance which supports Tell Retabeh but not Tell el-Maskhuta, the former is usually identified with Pi-Atum today. Tell el-Maskhuta seems to have been largely unoccupied from the time of the Hyksos until the Seventh Century BCE, as per Holladay, but Tell el-Retabeh shows occupation from a wide variety of eras, and so does not help us much in narrowing down the date of the Exodus. | |||

| A Judahite cultic object associated with the exodus was the brazen serpent or ]: according to 2 Kings 18:4, the brazen serpent had been made by Moses and was worshiped in the ] in Jerusalem until the time of king ] of Judah, who destroyed it as part of a religious reform, possibly {{circa|727 BCE}}.{{sfn|Bartusch|2003|p=41}}{{efn|" broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until those days the people of Israel had made offerings to it; it was called Nehushtan" (2 Kings 18:4).}} In the Pentateuch, Moses creates the brazen serpent in Numbers 21:4-9. Meindert Dijkstra writes that while the historicity of the Mosaic origin of the Nehushtan is unlikely, its association with Moses appears genuine rather than the work of a later redactor.{{sfn|Dijkstra|2006|p=28}} Mark Walter Bartusch notes that the nehushtan is not mentioned at any prior point in Kings, and suggests that the brazen serpent was brought to Jerusalem from the Northern Kingdom after its destruction in 722 BCE.{{sfn|Bartusch|2003|p=41}} | |||

| ===Composition of the Torah narrative=== | |||

| Some writers have tried to discount the occurrence of Rameses as a city name in Ex. 1:11. Traditionalists point out that just because the term Rameses is used in the Bible for the site the Israelites built, it does not mean that Rameses could not simply have been a later name for a site built just before the traditional Exodus date. One would probably have to locate Rameses at some site other than Qantir, where the Egyptian Pi-Rameses almost certainly was, to maintain this argument. The archaeology of Qantir more readily lends itself to a Hyksos era Exodus or a late Exodus. Alternately, some suggest that the name Rameses had been used as a name element by pharaohs before Rameses I, perhaps allowing a biblical Exodus date. While this is true, evidence for another city by this name in such an era is lacking. Redford claimed that Rameses was a name for Tanis, which did not have significant occupation during the time of Rameses II, but evidence for this conjecture is also lacking. The name Rameses more likely refers to the Egyptian of pi-Rameses at Qantir rather than Tanis which is not known to have been referred to by that name in other times, although statuary formerly at Pi-Rameses does occur there. When the Bible uses the term Rameses as a city name, it is mirroring a situation that occurred only in Dynasty XIX, an era from which a very early strata of text probably came, whether or not it has been significantly revised since. | |||

| The revelation of God on Sinai appears to have originally been a tradition unrelated to the Exodus.{{sfn|Baden|2019|p=9}} Joel S. Baden notes that "he seams still show: in the narrative of Israel's rescue from Egypt there is little hint that they will be brought anywhere other than Canaan{{snd}}yet they find themselves heading first, unexpectedly, and in no obvious geographical order, to an obscure mountain."{{sfn|Baden|2019|p=10}} In addition, there is widespread agreement that the revelation of the law in Deuteronomy was originally separate from the Exodus:{{sfn|Assmann|2018|p=204}} the original version of Deuteronomy is generally dated to the 7th century BCE.{{sfn|Grabbe|2017|p=49}} The contents of the books of ] and ] are late additions to the narrative by priestly sources.{{sfn|Dever|2001|p=99}} | |||

| Scholars broadly agree that the publication of the Torah (or of a proto-Pentateuch) took place in the mid-Persian period (the 5th century BCE), echoing a traditional Jewish view which gives ], the leader of the Jewish community on its return from Babylon, a pivotal role in its promulgation.{{sfn|Romer|2008|p=2 and fn.3}} Many theories have been advanced to explain the composition of the first five books of the Bible, but two have been especially influential.{{sfn|Ska|2006|p=217}} The first of these, Persian Imperial authorisation, advanced by Peter Frei in 1985, is that the Persian authorities required the Jews of Jerusalem to present a single body of law as the price of local autonomy.{{sfn|Ska|2006|p=218}} Frei's theory was demolished at an interdisciplinary symposium held in 2000, but the relationship between the Persian authorities and Jerusalem remains a crucial question.{{sfn|Eskenazi|2009|p=86}} The second theory, associated with Joel P. Weinberg and called the "Citizen-Temple Community", is that the Exodus story was composed to serve the needs of a post-exilic Jewish community organized around the Temple, which acted in effect as a bank for those who belonged to it.{{sfn|Ska|2006|pp=226–227}} The books containing the Exodus story served as an "identity card" defining who belonged to this community (i.e., to Israel), thus reinforcing Israel's unity through its new institutions.{{sfn|Ska|2006|p=225}} | |||

| While one reasonably argue, with some justification, that Dynasty XVIII finds might yet be unearthed at Qantir, so that the Israelites could have built a city 'Rameses' at the traditional Exodus date, it has not been found yet, and this is not the only site to show such an occupation pattern. It had long been thought that Edom had been for the most part unoccupied until at least the Ninth Century BCE, but recent excavations there by Levy and Najjar have turned up evidence of copper mining activity from the Twelfth Century. It seemed that previous investigations only examined highland sites, whereas an older lowland mining facility had already been reported by Glueck. When this mining facility was examined, remains radiocarbon dated to the mid-Ninth to Twelfth Centuries BCE were found, but these earliest mining strata rested on bedrock, so in this case, the finds support a Late Exodus, but do not, at least as yet, have finds attributed to the traditional Exodus date. Likewise, although Seir had been mentioned in Egyptian records at earlier times, recalling Edom's Mt. Seir of the Bible, the first mention of it by the name Edom is in the Papyrus Anastasi from the time of Merenptah, (1223-1211 BCE). Since Edom had to be substantial enough to make Israel detour around the Kings Highway through it during the Wandering after the Exodus, again the archaeology works better with a Late Exodus of some sort rather than either a traditional or a Hyksos era Exodus. | |||

| ==Hellenistic Egyptian parallel narratives== | |||

| The archaeology of the Conquest of Canaan also appears to be late. A stele found commemorating raids that took place late in the reign of Thutmose III describes sacking cities in Palestine from which he brought back thousands of hostages, including some from cities with rather familiar sounding names; i.e. Joseph-el and Jacob-el. This seems an unlikely action for a pharaoh so worried about Israelite overpopulation that he directs the midwives to kill the male Israelite babies and enslaves them with hard labor. Iron, which the Philistines were able to work in the early Judges era, did not come to the region archaeologically until ca. 1190 BCE; i.e. the Iron Age. Egyptian control and raiding of Canaan also would have taken place throughout the time when this chronology would place the Judges era; and yet what should have been significant Egyptian incursions worthy of mention during the Judges era are not recorded in the Bible, although a later such incursion is recorded. Finally, and most significantly, the Conquest/Settlement of Canaan by proto-Israelites appears to have taken place centuries later, to judge from archaeology. A few cuneiform writings in these earlier layers have survived, and the predecessors of these layers that predate the proto-Israelite ones do not seem to have spoken Hebrew, but languages referred to by archaeologists as Canaanite, or even perhaps Mycenaean in the case of the ]. Additionally, the archaeology of the cities Josephs was said to have conquered, at sites such as Hazor, Lachish, Megiddo, and Bethel, show transitions from Canaanite to proto-Israelite material culture in the range 1250-1140 BCE, but primarily only in the north and the central highlands at 1400 - a time when the traditional chronology would have the Conquest beginning. | |||

| Writers in Greek and Latin during the ] (late 4th century BCE–late 1st century BCE) record several Egyptian tales of the expulsion of a group of foreigners connected to the Exodus.{{sfn|Droge|1996|p=134}} These tales often include elements of the ] ("Hyksos period") and most are extremely ].{{sfn|Assmann|2009|pp=29, 34-35}} | |||

| The earliest non-biblical account is that of ] ({{circa|320 BCE}}) as preserved in the first century CE Jewish historian ] in '']'' and in a variant version by the first-century BCE Greek historian ].{{sfn|Droge|1996|p=131}} Hecataeus tells how the Egyptians blamed a plague on foreigners and expelled them from the country, whereupon Moses, their leader, took them to Canaan.{{sfn|Assmann|2009|p=34}} In this version, Moses is portrayed extremely positively.{{sfn|Droge|1996|p=134}} | |||

| In any event, the ] is a ''terminus ad quem'' for Israel to have come into existence. Contra expectations derived from the traditional Exodus date, this first archaeological mention of Israel, it is widely agreed, documents events in the reign of the pharaoh ]. Merenptah's reign was over by 1211 BCE (or a little thereafter if proposed date corrections are used), and so we are compelled to conclude that Israel existed by then, so long as mainstream Egyptian chronologies are employed. Contra popular opinion about the Stele, it does not require the Exodus to already have happened; only that some Israelites were already in Canaan. Had the Exodus happened in e.g. 1446 BCE, Israel should have been settled in Canaan and long established. Yet, the Stele uses a determinative symbol which signifies a tribe in referring to Israel, instead of a city determinative, as with other peoples mentioned; allowing the possibility that the Israelites were not yet settled. Furthermore, it claims that they are "without seed", implying that all adult males had been killed - yet there is no such decimation of Israel by Egypt recorded in the Judges era, even though the Bible does not hesitate to list the defeats of the Israelites. | |||

| ], also preserved in Josephus's ''Against Apion'', tells how 80,000 lepers and other "impure people", led by a priest named ], join forces with the former Hyksos, now living in ], to take over Egypt. They wreak havoc until the Pharaoh and his son chase them out to the borders of ], where Osarseph gives the lepers a law code and changes his name to Moses. The identification of Osarseph with Moses in Manetho's account may be an interpolation or may come from Manetho.{{sfn|Droge|1996|pp=134–35}}{{sfn|Feldman|1998|p=342}}{{sfn|Assmann|2009|p=34}} | |||

| === Chronologies Synchronizing the Exodus with the Expulsion of the Hyksos === | |||

| Other versions of the story are recorded by the first-century BCE Egyptian grammarian ], who set the story in the time of Pharaoh ] (Bocchoris), the first-century CE Egyptian historian ], and the first-century BCE Gallo-Roman historian ].{{sfn|Assmann|2009|p=35}} The first-century CE Roman historian ] included a version of the story that claims that the Hebrews worshipped a ] as their god to ridicule Egyptian religion, whereas the Roman biographer ] claimed that the Egyptian god ] was expelled from Egypt and had two sons named Juda and Hierosolyma.{{sfn|Assmann|2009|p=37}} | |||

| The next most natural time to try to place the Exodus is during a time when a group of Semitic kings ruled Egypt for generations before being expelled: a people known as the ]. There is also an intriguing reason based on ancient traditions to associate these peoples with the Israelites. The great Jewish historian ], writing a little after the time of Jesus, records the Egyptian historian Manetho's assertion that the Israelites were among some of the diseased expelled in the time of the Hyksos. In the modern era, Bimson had until recent years been the most influential scholar to re-embrace this view, by making charts of when various proposed sites in ancient Palestine were settled, and comparing them to the biblical narrative, while rejecting the usual interpretations by archaeologists of which layers were Canaanite and which were Israelite. More recently, scholars such as Redford and Herzog have supported this idea as well. | |||

| The stories may represent a polemical Egyptian response to the Exodus narrative.{{sfn|Gmirkin|2006|p=170}} Egyptologist ] proposed that the story comes from oral sources that "must predate the first possible acquaintance of an Egyptian writer with the ]."{{sfn|Assmann|2009|p=34}} Assmann suggested that the story has no single origin but rather combines numerous historical experiences, notably the ] and Hyksos periods, into a folk memory.{{sfn|Assmann|2003|page=227}} | |||

| This idea is also attractive because one of the Hyksos leaders was even named Yakub-her (similar to ], or Jacob). | |||

| There is general agreement that the stories originally had nothing to do with the Jews.{{sfn|Droge|1996|p=134}} ] suggested that it may have been the Jews themselves that inserted themselves into Manetho's narrative, in which various negative actions from the point of view of the Egyptians, such as desecrating temples, are interpreted positively.{{sfn|Gruen|2016|pp=218-220}} | |||

| This is not to say that this sort of chronology is not without its problems as well. The first mention of Israel thus far found in the archaeological record is encountered until centuries later, when numerous Egyptian records of these centuries have survived. The archaeology of the sites usually associated with Joshua's conquests shows transitions to Semitic material culture only centuries later, according to most archaeologists. The Philistines knew how to work iron early in the Judges era, and yet if we put the conquest 40 years after the Hyksos expulsion, given 40 years of wandering, the Iron age was not to arrive for centuries. This also leaves new questions to be answered: If the Hyksos were kings and they were the Israelites, why does the Bible describe the Israelites as slaves? True, Joseph is described in regal terms, but they had long been in practical slavery before the Exodus. The Hyksos had been kings right up until their defeat. This seems an unlikely editorial gloss: slaves for kings. If we on the other hand suppose the Israelites to have been a minority under the Hyksos, why is it not mentioned that Pharaoh is not Egyptian, but more closely related to the Israelites than the wider population? Why does it not tell us that all the line of the kings of Egypt were expelled upon the Exodus? Bimson has tried to argue that the date of the Hyksos layers in Egypt should be lowered to coincide with the traditional Exodus date, but Bietak, a prominent Egyptian archaeologist, rejects this idea; and attempting to do so only compounds the problem that the transition from Canaanite to proto-Israelite material culture at many Joshua-associated sites happens only centuries later. Also, "]" and "]" are thought with a large amount of evidence to support to date from the era between ] to ]. | |||

| ==Religious and cultural significance== | |||

| ===Two part invasion=== | |||

| ===In Judaism=== | |||

| A Canadian scholar, ], suggested a two part conquest of Canaan: the first wave corresponding to the observed settlement of proto-Israelite lime covered cistern digging material culture in the central highlands beginning about 1400 BCE, and the second wave corresponding with the later destruction of Hazor, then understood based on the work of Yilgal Yadin, to have occurred ca. 1250. Yet, 1250 is an awkward destruction date for Hazor. It is too late to be synchronized with a 1446 Exodus after 40 years of wandering, and it is uncomfortably early to allow Rameses II to be the pharaoh of the Oppression, followed by 40 years of Wandering. | |||

| {{See also|Passover|Passover Seder}} | |||

| Commemoration of the Exodus is central to Judaism, and ]. In the Bible, the Exodus is frequently mentioned as the event that created the Israelite people and forged their bond with God, being described as such by the prophets Hosea, Jeremiah, and ].{{sfn|Baden|2019|pp=35-36}} The Exodus is invoked daily in ] and celebrated each year during the Jewish holidays of ], ], and ].{{sfn|Tigay|2004|p=106}} The fringes worn at the corners of traditional Jewish prayer shawls are described as a physical reminder of the obligation to observe the laws given at the climax of Exodus: "Look at it and recall all the commandments of the Lord" (Numbers).{{sfn|Sarason|2015|p=53}} The festivals associated with the Exodus began as agricultural and seasonal feasts but became completely subsumed into the Exodus narrative of Israel's deliverance from oppression at the hands of God.{{sfn|Tigay|2004|p=106}}{{sfn|Nelson|2015|p=43}} | |||

| ] table setting, commemorating the Passover and Exodus]] | |||

| For Jews, the Passover celebrates the freedom of the Israelites from captivity in Egypt, the settling of Canaan by the Israelites, and the "passing over" of the angel of death during the ].{{sfn|Black|2018|p=10}}{{sfn|Black|2018|p=26}} Passover involves a ritual meal called a ] during which parts of the exodus narrative are retold.{{sfn|Black|2018|p=19}} In the ] of the Seder it is written that every generation is obliged to remind and identify itself in terms of the Exodus. Thus the following words from the ] are recited: "In every generation a person is duty-bound to regard himself as if he personally has gone forth from Egypt."{{sfn|Klein|1979|p=105}}{{efn|"In every generation a person is duty-bound to regard himself as if he personally has gone forth from Egypt, since it is said 'And you shall tell your son in that day saying, it is because of that which the Lord did for me when I came forth out of Egypt." —Exodus 13:8{{sfn|Neusner|2005|p=75}}}} Because the Israelites fled Egypt in haste without time for bread to rise, the unleavened bread ] is eaten on Passover, and homes must be cleansed of any items containing leavening agents, known as ].{{sfn|Black|2018|pp=22-23}} | |||

| Shavuot celebrates the granting of the Law to Moses on Mount Sinai; Jews are called to rededicate themselves to the covenant on this day.{{sfn|Black|2018|p=19}} Some denominations follow Shavuot with ], during which the "two most heinous sins committed by the Jews in their relationship to God" are mourned: the ] and the doubting of God's promise by ].{{sfn|Black|2018|pp=19-20}} A third Jewish festival, ], the Festival of Booths, is associated with the Israelites living in booths after they left their previous homes in Egypt.{{sfn|Tigay|2004|p=106}} It celebrates how God provided for the Israelites while they wandered in the desert without food or shelter.{{sfn|Black|2018|p=20}} It is celebrated by building a ], a temporary shelter also called a booth or tabernacle, in which the rituals of Sukkot are performed, recalling the impermanence of the Israelites' homes during the desert wanderings.{{sfn|Black|2018|pp=60-61}} | |||