| Revision as of 02:32, 15 October 2006 editKPalicz (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users839 edits broken english, biased scare quotes, and unnecessary, non-relevant information on Erne Kis← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:48, 26 December 2024 edit undoXTheBedrockX (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users77,831 edits new key for Category:Hungarian irredentism: " " using HotCat | ||

| (719 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Political ideas to reunite Historic Hungary}} | |||

| :''See also: ] (disambiguation page)'' | |||

| {{Other uses|Greater Hungary (disambiguation){{!}}Greater Hungary}} | |||

| ], the Hungarian territories in the ] consisting of the ] and the ]. Hungary also jointly governed the ] (blue) with ].]] | |||

| '''Hungarian irredentism''' or '''Greater Hungary''' ({{langx|hu|Nagy-Magyarország}}) are ] political ideas concerning redemption of territories of the historical ]. The objective is to at least to regain control over Hungarian-populated areas in Hungary's neighbouring countries. Hungarian historiography uses the term "'''Historic Hungary'''" ({{Langx|hu|link=no|történelmi Magyarország}}). "Whole Hungary" ({{Langx|hu|link=no|Egész-Magyarország}}) is also commonly used by supporters of this ideology. | |||

| The ] defined the current borders of Hungary and, compared against the claims of the pre-war Kingdom, post-Trianon Hungary had approximately 72% less land stake and about two-thirds fewer inhabitants, almost 5 million of these being of Hungarian ethnicity.<ref name="Fenyvesi">{{cite book |title=Hungarian language contact outside Hungary: studies on Hungarian as a minority language |first=Anna |last=Fenyvesi |year=2005 |publisher=John Benjamins Publishing Company |isbn=90-272-1858-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y3JYwHGYn7MC&q=hungarians+3+million&pg=PA2 |page=2 |access-date=2011-08-15}}</ref><ref>{{Cite encyclopedia | |||

| ]: the lighter green shows Hungary proper and the darker green shows autonomous Croatia-Slavonia within Hungary. The green areas comprise the borders of historical Hungary within Habsburg Monarchy, which is one of the more extreme revisionist proposals for the creation of Greater Hungary.]] | |||

| | title = Treaty of Trianon | |||

| | encyclopedia = ] | |||

| | date = 9 February 2024 | |||

| | url = http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9073332/Treaty-of-Trianon }}</ref> However, only 54% of the inhabitants of the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary were Hungarians before World War I.<ref>A magyar szent korona országainak 1910. évi népszámlálása. Első rész. A népesség főbb adatai. (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyar Kir. Központi Statisztikai Hivatal (KSH). 1912.</ref><ref>Anstalt G. Freytag & Berndt (1911). Geographischer Atlas zur Vaterlandskunde an der österreichischen Mittelschulen. Vienna: K. u. k. Hof-Kartographische. "Census December 31st 1910"</ref> Following the treaty's instatement, Hungarian leaders became inclined towards revoking some of its terms. This political aim gained greater attention and was a serious national concern up through the Second World War.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://hungaria.org/hal/hungary/index.php?halid=14&menuid=248#318 |title=HUNGARY |access-date=2011-02-13 |publisher=Hungarian Online Resources (Magyar Online Forrás) |archive-date=2010-11-24 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101124233524/http://hungaria.org/hal/hungary/index.php?halid=14&menuid=248#318 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| After ], despite the "] of peoples" idea of the Allied Powers, only one plebiscite was permitted (later known as the ]) to settle disputed borders on the former territory of the ],<ref>{{cite book|author=Richard C. Hall|title=War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia|publisher=]|year=2014|page=309|isbn=9781610690317|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wy3TBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA309}}</ref> settling a smaller territorial dispute between the ] and the ], because some months earlier, the ] launched a series of attacks to oust the Austrian forces that entered the area. During the plebiscite in late 1921, the polling stations were supervised by British, French, and Italian army officers of the Allied Powers.<ref>{{cite book|title=Irredentist and National Questions in Central Europe, 1913–1939: Hungary, 2v, Volume 5, Part 1 of Irredentist and National Questions in Central Europe, 1913–1939 Seeds of conflict|publisher=]|year=1973|page=69|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zQxWAAAAYAAJ&q=%22only+plebiscite%22+Sopron}}</ref> | |||

| '''Greater Hungary''' (]: ''Nagy-Magyarország'') is a political goal of Hungarian ], who want to restore the borders of historical Hungary as they were before ]. Historical ] is often used on by both proponents and opponents of Greater Hungary. | |||

| Irredentism in the 1930s led Hungary to form an alliance with ] ]. Eva S. Balogh states: "Hungary's participation in World War II resulted from a desire to revise the Treaty of Trianon so as to recover territories lost after World War I. This was the basis for Hungary's interwar foreign policy."<ref>Eva S. Balogh, "Peaceful Revision: The Diplomatic Road to War." ''Hungarian Studies Review'' 10.1 (1983): 43-51. </ref> | |||

| Although such outright ] remains a marginalized political position, adherents of this position often ally politically with proponents of milder forms of pan-] ideology in organizations such as the (relatively moderate) ] or those who wish to establish an autonomous ] within ], currently a region of ]. | |||

| Hungary, supported by the ], was successful temporarily in gaining some regions of the former Kingdom by the ] in 1938 (southern Czechoslovakia with mainly Hungarians) and the ] in 1940 (] with an ethnically mixed population), and through military campaign gained regions of ] in 1939 and (ethnically mixed) ], ], ], and ] in 1941 (]). Following the close of World War II, the borders of Hungary as defined by the Treaty of Trianon were restored, except for three Hungarian villages that were transferred to Czechoslovakia. These villages are today administratively a part of ]. | |||

| ==Historical survey== | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ] before 1918]] | |||

| An independent ] was established in approximately ] AD, and remained a power in central Europe until ] conquered it in ] at the ]. After the battle, territory of former Hungary was divided into three portions: in the West, ] was included in the ] of ] and retained its existence as Habsburg province; the Ottomans controlled south-central parts of former Hungary (including ] and ]); while, in the East, ] remained a semi-independent principality, successfully playing the Ottomans and Austrians against each other. Between ] and ], the Habsburg Monarchy conquered the Ottoman territories, which were part of Hungarian kingdom before 1526, and incorporated some of these areas into the ], which was still a Habsburg province. | |||

| ===Background=== | |||

| After a suppressed uprising in Hungary in 1848–1849 (one of the ]; see especially ]), the Kingdom of Hungary and its ] were dissolved, and Hungary was divided into a series of smaller districts, directly controlled from ]. This new centralized rule, however, failed to provide stability, and in the wake of military defeats the ] was transformed into ] in ], with Hungary becoming one of two autonomous parts of the new state (with self-rule in its internal affairs). | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The independent ] was established in 1000 AD, and remained a regional power in Central Europe until ] conquered its central part in 1526 following the ]. In 1541 the territory of the former Kingdom of Hungary was divided into three portions: in the west and north, ] retained its existence under ] rule; the Ottomans controlled the south-central parts of former Kingdom of Hungary; while in the east, the ] (later the ]) was formed as a semi-independent entity under Ottoman ]. After the Ottoman conquest in the Kingdom of Hungary, the ethnic structure of the kingdom started to become more multi-ethnic because of immigration to the sparsely populated areas. Between 1683 and 1717, the Habsburg monarchy conquered all the Ottoman territories that were part of the Kingdom of Hungary before 1526, and incorporated some of these areas into the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary. | |||

| This was followed by a policy of ] of non-Hungarian nationalities, most notably the aggressive promotion of the ] and supression of ]. The ] was greatly restricted so as to keep power in the hands of the Magyars. The new government of autonomous Hungary took the stance that Hungary should be a Magyar ], and that all other peoples living in Hungary—], ]s, ], ], ], ], and other ethnic minorities—should be assimilated (The ] were to some extent an exception to this, as they had a fair degree of self-government within the ], a dependent kingdom within Hungary). Census results show that this process of Magyarization was somewhat effective: according to the Austrian census of ], Hungarians were 36.5% of the population of the Kingdom of Hungary, but by the ] census, this percentage had risen to 48%. Most of the increase came at the expense of the Germans and Jews, who were scattered in small communities throughout the country and proved most willing to assimilate and become "Magyars". The Romanians and Slavic peoples of Hungary, on the other hand, who were largely ] peoples living in large areas where they were a majority, proved much more resistant to the government's efforts. | |||

| After a ], the Kingdom of Hungary and its ] were dissolved, and territory of the Kingdom of Hungary was divided into 5 districts, which were ] & ], ], ], ] and ], directly controlled from ] while Croatia, Slavonia, and the ] were separated from the Kingdom of Hungary between 1849 and 1860. This new centralized rule, however, failed to provide stability, and in the wake of ] the ] was transformed into ] with the ], by which Kingdom of Hungary became one of two constituent entities of the new ] with self-rule in its internal affairs. | |||

| ==Treaty of Trianon== | |||

| {{main|Treaty of Trianon}} | |||

| ] | |||

| A considerable number of the figures who are today considered important in Hungarian culture were born in what are today parts of ], ], ], ], and ] (''see ]''). Names of Hungarian dishes, common surnames, proverbs, sayings, folk songs etc. also refer to these rich cultural ties. After 1867, the non-Hungarian ethnic groups were subject to assimilation and ]. | |||

| The peace treaties signed after the First World War redefined the national borders in ]. The dissolution of ], after its defeat in the ], gave an opportunity for the subject nationalities of the old Monarchy to claim the rights to form their own national states. Hungary itself became an independent state in 1918. The ] of ] was the peace treaty signed between the allies and Hungary. The Treaty defined borders of a newly independent Hungary. In the north, the Slovak and Ruthene areas become part of the new state of ]. Transylvania and most of the ] united with ], while Croatia-Slavonia and the other southern areas became part of the new state of ]. The post-Trianon Hungary had less than half of the population than the former Kingdom. The population of the territories of the former Kingdom of Hungary that were not assigned to the post-Trianon Hungary was mainly non-Hungarian, although, it also included a sizable minority of ethnic Magyars. | |||

| Before ], only three European countries declared ethnic minority rights, and enacted minority-protecting laws: the first was Hungary (1849 and 1868), the second was Austria (1867), and the third was Belgium (1898). In contrast, the legal systems of other pre-WW1 era European countries did not allow the use of European minority languages in primary schools, in ], in offices of public administration and at the legal courts.<ref>Józsa Hévizi (2004): , The Regional and Ecclesiastic Autonomy of the Minorities and Nationality Groups></ref> | |||

| Trianon thus defined Hungary's new borders in a way that made ethnic Hungarians the absolute majority in the country. The winning powers created from one multiethnic kingdom (48% Hungarians in the Kingdom of Hungary and 54% in Hungary proper, excluding Croatia-Slavonia) three multiethnic states (Czechoslovakia with 45+12% "Czechoslovaks", Greater Romania with 65% Romanians, and Yugoslavia with 74% Serbs, Croats and Slovenes). About 3.3 million ethnic ] would not be included within the borders of post-Trianon Hungary, which became one of the reasons for disputes and hostilities between Hungary and its neighbours. A considerable number of non-Hungarian nationalities remained within the new borders of Hungary: Slovaks numbered 141,877 according to Hungarian sources and 450,000–550,000 according to ] sources, 550,062 (6.9%) ] as of ] and some 82,000 ] and ] as of ]. However the percentage of minorities decreased throughout the 20th century, as for example, there are only 17,000 Slovaks in Hungary today. Thus, Trianon recognized independence of Hungary, a goal for which Hungarians had fought for centuries, but which they hardly achieved in the way they had envisioned it. | |||

| Among the most notable policies was the promotion of the ] as the country's official language (replacing ] and ]); however, this was often at the expense of ] and the ]. The new government of autonomous Kingdom of Hungary took the stance that Kingdom of Hungary should be a Hungarian ], and that all other peoples living in the Kingdom of Hungary—], ]s, ], ], ], ] and other ethnicities—should be assimilated. (The ] were to some extent an exception to this, as they had a fair degree of self-government within Croatia-Slavonia, a dependent kingdom within the Kingdom of Hungary.) | |||

| ==After Trianon== | |||

| ===World War I=== | |||

| After the Treaty of Trianon, a political concept known as ] became popular in Hungary. Hungarian revisionism claims that the Treaty of Trianon was an injury for the Hungarian people. Hungarian revisionists have created a nationalistic conception based on the injustice of the Treaty of Trianon with the political goal of the "''restoration of borders of a thousand-year-old Hungary''". | |||

| {{Main article|Treaty of Trianon}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The peace treaties signed after the First World War redefined the national borders of Europe. The dissolution of ], after its defeat in the First World War, gave an opportunity for the subject nationalities of the old Monarchy to all form their own nation states (however, most of the resulting states nevertheless became multi-ethnic states comprising several nationalities). The ] of 1920 defined borders for the new Hungarian state: in the north, the Slovak and Ruthene areas, including Hungarian majority areas became part of the new state of ]. Transylvania and most of the ] became part of ], while Croatia-Slavonia and the other southern areas became part of the new state of ]. | |||

| The arguments of Hungarian irredentists for their goal were: the presence of ] areas in the neighboring countries, perceived historical traditions of the ], or the perceived geographical unity and economic symbiosis of the region within the ], although some Hungarian irredentists preferred to regain only ethnically Hungarian majority areas surrounding Hungary.{{citation needed|date=January 2013}} | |||

| The justification for this revisionist aim usually followed the rhetoric that "two-thirds of the country's area was taken by the neighbouring countries, recognised later by a forced peace treaty", despite the fact that separation from the Kingdom of Hungary was in many cases initiated by the local people. Revisionists often dismiss or ignore the fact that most of these territories had ethnic majorities of non-Hungarians and minimize the role that forced Magyarization played in stirring nationalist feelings among non-Hungarian groups. Thus, the majority of the local inhabitants of these areas (Croats, Romanians, Serbs, Slovaks, Ukrainians, Ruthenians, Slovenians, etc.) regarded separation from the Kingdom of Hungary as liberation. However, historians generally concede that one of the goals of Trianon was to punish ] and Austria-Hungary for starting World War I and fighting against the Entente during the war. Also, several municipalities that had purely ethnic Hungarian population were excluded from post-Trianon Hungary. Indeed, about one-third of the 3.3 million Hungarians in the new neighbouring states lived directly on the borders. | |||

| Post-Trianon Hungary had about half of the population of the former Kingdom. The population of the territories of the Kingdom of Hungary that were not assigned to the post-Trianon Hungary had, in total, non-Hungarian majority, although they included a sizable proportion of ethnic Hungarians and Hungarian majority areas. According to Károly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi, the ethnic composition (by their native language) in 1910 (note: three-quarters of the ] stated Hungarian as their mother tongue, and the rest, German, in the absence of ] as an option<ref> Silber, Michael K. 2010. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe</ref>): | |||

| For centuries, Hungarian rulers such as ] had maintained a relatively cosmopolitan kingdom; for example, Croatia joined the kingdom via a royal union. Because this cosmopolitan identity existed for centuries, modern Hungarian culture includes significant elements from places which belonged to Hungary in various parts of the history. Also, a considerable number of the figures who are today considered important in Hungarian culture were born in what are now parts of ], ], ], ] and ] (''see ]''). Names of Hungarian dishes, common surnames, proverbs, sayings, folk songs etc. also refer back to these rich cultural ties. After 1867, the cosmopolitan character of the Kingdom started to change into the national state of Hungarians, in which other ethnic groups were subject to assimilation and Magyarization. | |||

| ] | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| ! Region !! Hungarians !! Germans !! Romanians !! Serbs !! Croats !! Ruthenians !! Slovaks !! Note | |||

| |- | |||

| |]<ref>{{cite book |title=Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography |author=Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi |year=1995 |publisher=Matthias Corvinus Publishing |isbn=1-882785-04-5 |url=http://www.hungarianhistory.com/lib/hmcb/Tab14.htm |chapter=Table 14. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Transylvania (1880–1992) |access-date=2011-02-28}}</ref> || 31.7% || 10.5% || 54.0% || 0.9% || || || 0.6% || Hungarians are concentrated in ] (Hungarian majority), while as well significant in the border areas. | |||

| |- | |||

| |]<ref>{{cite book |title=Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography |author=Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi |year=1995 |publisher=Matthias Corvinus Publishing |isbn=1-882785-04-5 |url=http://www.hungarianhistory.com/lib/hmcb/Tab21.htm |chapter=Table 21. Ethnic structure of the population of the present territory of Vojvodina (1880–1991) |access-date=2011-02-28}}</ref> || 28.1% || 21.4% || 5.0% || 33.8% || 6.0% || 0.9% || 3.7% || | |||

| |- | |||

| |]<ref>{{cite book |title=Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography |author=Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi |year=1995 |publisher=Matthias Corvinus Publishing |isbn=1-882785-04-5 |url=http://www.hungarianhistory.com/lib/hmcb/Tab11.htm |chapter=Table 11. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Transcarpathia (1880..1989) |access-date=2011-02-28}}</ref> || 30.6% || 10.6% || 1.9% || || || 54.5% || 1.0% || 1.0% Slovaks and Czechs | |||

| |- | |||

| |]<ref>{{cite book |title=Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography |author=Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi |year=1995 |publisher=Matthias Corvinus Publishing |isbn=1-882785-04-5 |url=http://www.hungarianhistory.com/lib/hmcb/Tab07.htm |chapter=Table 7. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Slovakia (1880–1991) |access-date=2011-02-28}}</ref> || 30.2% || 6.8% || || || || 3.5% || 57.9% || with Hungarians concentrated in the south, which has a Hungarian majority today. | |||

| |- | |||

| |]<ref>{{cite book |title=Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography |author=Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi |year=1995 |publisher=Matthias Corvinus Publishing |isbn=1-882785-04-5 |url=http://www.hungarianhistory.com/lib/hmcb/Tab25.htm |chapter=Table 25. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Burgenland (1880–1991) |access-date=2011-02-28}}</ref> || 9.0% || 74.4% || || || 15% || || || | |||

| |- | |||

| |]<ref name="seton-watson">Seton-Watson, Hugh (1945). '''' (3rd ed.). CUP Archive. p. 434. {{ISBN|1-00-128478-X}}.</ref> || 4.1% || 5.1% || || 24.6% || 62.5% || || || | |||

| |} | |||

| Trianon thus defined Hungary's new borders in a way that made ethnic Hungarians the overwhelmingly absolute majority in the country. Almost 3 million ethnic ] remained outside the borders of post-Trianon Hungary.<ref name="Fenyvesi"/> A considerable number of non-Hungarian nationalities remained within the new borders of Hungary, the largest of which were ] (]) with 550,062 people (6.9%). Also, the number of Hungarian Jews remained within the new borders was 473,310 (5.9% of the total population), compared with 911,227 (5.0%), in 1910.<ref></ref><ref></ref> | |||

| ==Near realisation of Greater Hungary== | |||

| ====Aftermath==== | |||

| ] and ]]] | |||

| ]'s border proposal presented to ] in 1934.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Eiler |first=Ferenc |title=Kisebbségvédelem és Revízió |year=2007 |isbn=9789636930318 |page=85 |chapter=A kisebbségi kérdés helye a magyar kormánypolitikában|publisher=MTA Kisebbségkutató Intézet }}</ref>]] | |||

| After the ], a political concept known as Hungarian Irredentism became popular in Hungary. The Treaty of Trianon was an injury for the Hungarian people and Hungarian nationalists have created an ideology with the political goal of the restoration of borders of historical pre-Trianon Kingdom of Hungary. | |||

| The justification for this aim usually followed the fact that two-thirds of the country's area was taken by the neighboring countries with approximately 3 million<ref name="Fenyvesi" /> Hungarians living in these territories. Several municipalities that had purely ethnic Hungarian population were excluded from post-Trianon Hungary, which had borders designed to cut most economic regions (Szeged, Pécs, Debrecen etc.) in half, and keep railways on the other side. Moreover, five of the pre-war kingdom's ten largest cities were drawn into other countries. | |||

| Hungary's government allied itself with ] during the ] in exchange for assurances that Greater Hungary's borders would be restored. This goal was partially achieved when Hungary expanded its borders into Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia at the outset of the war. These annexations were affirmed under the ] (]), two ] (] and ]), and aggression against Yugoslavia (]), the latter achieved, for formal reasons, one day after the German army had already invaded Yugoslavia. | |||

| All interwar governments of Hungary were obsessed with recovering at least the Magyar-populated territories outside Hungary.{{sfn|Ambrosio|2001|p=113}} In 1934, ], on the request of ], presented the territories which he wished to reannex peacefully.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| Ethnic Hungarians inhabited parts of the occupied areas, but other areas were mainly inhabited by non-Hungarians. For example, according to Romanian estimations, the population of ] was composed of 50.2% ] and 37.1% ] <ref>Dinu C. Giurescu, Romania in al doilea razboi mondial</ref>. The Hungarian census from 1941 counted 53.5% ] (with approximately 150,000 Hungarian Jews included) and 39.1% ] <ref>Hungarian census from ]</ref>. | |||

| ===Near realization=== | |||

| The Yugoslav territory occupied by Hungary had approximately one million inhabitants, including 543,000 Yugoslavs (Serbs, Croats and Slovenes), 301,000 Hungarians, 197,000 Germans, 40,000 Slovaks, 15,000 Rusyns, and 15,000 Jews.<ref>Peter Rokai - Zoltan Đere - Tibor Pal - Aleksandar Kasaš, Istorija Mađara, Beograd, 2002.</ref> The 1931 census put the percentage of the speakers of Hungarian in Bačka at 34.2%, while later Hungarian data from 1941 show 45.4%. This means that from the beginning of the occupation, the number of Hungarian speakers in Bačka increased by 48,550, while the number of Serbian speakers decreased by 75,166.<ref>Zvonimir Golubović, ''Racija u Južnoj Bačkoj, 1942. godine'', Novi Sad, 1991.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Hungary's government allied itself with ] during World War II in exchange for assurances that Greater Hungary's borders would be restored. This goal was partially achieved when Hungary reannexed territories from Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia at the outset of the war. These annexations were affirmed under the ] (1938), two Vienna Awards (] and ]), and aggression against Yugoslavia (1941), the latter achieved one week after the German army had already invaded Yugoslavia. | |||

| The percentage of Hungarian speakers was 84% in southern Slovakia and 15% in the ]. | |||

| The percentage of Hungarian speakers was 84% in southern Czechoslovakia and 15% in the ]. | |||

| The establishment of Hungarian rule was followed by brutal war crimes against the local non-Hungarian population in some areas, such as ], where Hungarian military between 1941 and 1944 killed 6,177 civilians, mainly ] and ], but also Hungarians who did not collaborate with the new authorities. The total number of people in Bačka who were victims of the Hungarian Axis regime (meaning that they were either killed, sent to concentration camps, or to forced labour) was 19,573 <ref>Slobodan Ćurčić, Broj stanovnika Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 1996.</ref> (This number does not count those who were expelled from Bačka, whose number was about 56,000 <ref>Zvonimir Golubović (see above)</ref>). | |||

| In ], the Romanian census from 1930 counted 38% ] and 49% ], while the Hungarian census from 1941 counted 53.5% ] and 39.1% ].<ref name="Hodosi, Kocsis">Károly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi, Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, Simon Publications LLC, 1998, p. 116-153 {{Dead link|date=February 2024|bot=InternetArchiveBot|fix-attempted=yes}}</ref> | |||

| In Northern Transylvania, close to 1,000 Romanian civilians fell victim to the Hungarian troops. The bloodshed was repaid in turn to Hungarian civilians, both in Yugoslavia by Yugoslav partisans (the exact number of ethnic Hungarians killed by Yugoslav partisans is not clearly established and estimates range from 4,000 to 40,000; 20,000 is often regarded as most probable <ref>Dimitrije Boarov, Politička istorija Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 2001.</ref>), and in Transylvania by Maniu guards (they killed several thousands of Magyars), towards the end of WWII. The Jewish population of Hungary and the areas it occupied were largely diminished as part of the ], as discussed by ] in his autobiography '']'', with the knowing support of the Hungarian authorities. Tens of thousands of Romanians fled from Hungarian-ruled Northern Transylvania, and vice versa. After the war the occupied areas were returned to neighbouring countries and Hungary's territory was slightly further reduced by ceding three villages South of Bratislava to Slovakia. | |||

| ], leader of Hungary from 16 October 1944 envisioned the creation a "Carpathian-Danubian" federation where nationalism is region based ("connationalism") and other peoples are willing to join independently. He excluded the Jews who were not "rooted in" the ], so they had to be relocated into a ], but not killed ("asemitism") according to him. Szálasi called his ideology ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sipos |first=Péter |title=Magyarország a második világháborúban |publisher=PETIT REAL Könyvkiadó |year=1997 |isbn=963-85411-5-6 |editor-last=Ravasz |editor-first=István |location=Budapest |trans-title=Hungary in the Second World War}}</ref> | |||

| The Yugoslav territory occupied by Hungary (including Bačka, Baranja, ] and Prekmurje) had approximately one million inhabitants, including 543,000 Yugoslavs (Serbs, Croats and Slovenes), 301,000 Hungarians, 197,000 Germans, 40,000 Slovaks, 15,000 Rusyns, and 15,000 Jews.<ref>Peter Rokai - Zoltan Đere - Tibor Pal - Aleksandar Kasaš, Istorija Mađara, Beograd, 2002.</ref> In Bačka region only, the 1931 census put the percentage of the speakers of Hungarian at 34.2%, while one of interpretations of later Hungarian census from 1941 states that, 45,4% or 47,2% declared themselves to be Hungarian native speakers or ethnic Hungarians<ref name="Hodosi, Kocsis" /> (this interpretation is provided by authors Károly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi. The 1941 census, however, did not recorded ethnicity of the people, but only mother/native tongue {{Dead link|date=February 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}). Population of entire Bačka numbered 789,705 inhabitants in 1941. This means that from the beginning of the occupation, the number of Hungarian speakers in Bačka increased by 48,550, while the number of Serbian speakers decreased by 75,166.<ref name="Zvonimir">Zvonimir Golubović, ''Racija u Južnoj Bačkoj, 1942. godine'', Novi Sad, 1991.</ref> | |||

| The establishment of Hungarian rule met with insurgency on part of the non-Hungarian population in some places and retaliation of the Hungarian forces was labelled war crimes such as ] and ]s in Northern Transylvania (directed against Romanians) or ], where Hungarian military between 1941 and 1944 deported or killed 19,573 civilians,<ref>Slobodan Ćurčić, Broj stanovnika Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 1996.</ref> mainly ] and Jews, but also Hungarians who did not collaborate with the new authorities. About 56,000 people were also expelled from Bačka.<ref name="Zvonimir"/> | |||

| The Jewish population of Hungary and the areas it occupied were partly diminished as part of the ].<ref>'']'' by ]</ref> Tens of thousands of Romanians fled from Hungarian-ruled Northern Transylvania, and vice versa. After the war the areas were returned to neighboring countries and Hungary's territory was slightly further reduced by ceding three villages south of Bratislava to Slovakia. Some Hungarians were killed both in Yugoslavia by Yugoslav partisans (the exact number of ethnic Hungarians killed by Yugoslav partisans is not clearly established and estimates range from 4,000 to 40,000; 20,000 is often regarded as most probable<ref>Dimitrije Boarov, Politička istorija Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 2001.</ref>{{page needed|date=May 2022}}), and in Transylvania by the ] towards the end of World War II.{{citation needed|date=May 2022}} | |||

| ==Modern era== | ==Modern era== | ||

| In 2010, ] changed its citizenship legislation, thus any subject who could certify ancestry on any territory ] may be as well granted Hungarian citizenship, if they are able to speak the Hungarian language (the ] may have an exception of the first criteria, as the area they live was not part of Hungary, regarding them also ecclesial documents may be accepted). | |||

| The following table lists areas with Hungarian population in neighboring countries today: | |||

| {| style="float: center;" class="wikitable" | |||

| |- bgcolor="#95B2C9" | |||

| | {{center|'''Country, region'''}} | |||

| | {{center|'''Hungarians'''}} | |||

| | {{center|'''Cultural, political center'''}} | |||

| | {{center|'''Proposed autonomy'''}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flag|Romania}}<br />parts of ] (mainly ], ] and part of ] counties, Central ]), see: ] | |||

| | 1,227,623 (6.5%)<ref>{{cite web|title=Final 2011 Census Result|url=http://www.recensamantromania.ro/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/REZULTATE-DEFINITIVE-RPL_2011.pdf|access-date=10 March 2014|archive-date=17 July 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130717125951/http://www.recensamantromania.ro/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/REZULTATE-DEFINITIVE-RPL_2011.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> in Romania<br>1,216,666 (17.9%) in Transylvania | |||

| | ]<br>] | |||

| | '']'' (which would have an area of 13,000 km<sup>2</sup><ref name=sznt>{{cite web|url=http://www.sznt.ro/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=210%3Athe-szeklers-and-their-struggle-for-autonomy&catid=4%3Aa-szekelyseg&Itemid=6&lang=en|title=The Szeklers and their struggle for autonomy|publisher=Szekler National Council|date=21 November 2009|access-date=28 November 2011|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111025094147/http://www.sznt.ro/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=210%3Athe-szeklers-and-their-struggle-for-autonomy&catid=4%3Aa-szekelyseg&Itemid=6&lang=en|archive-date=25 October 2011}}</ref> and a population of 809,000 people of which 75.65% Hungarians) | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flag|Serbia}}<br />parts of ] in northern ], see: ] | |||

| | 184,442 (2.77%) in Serbia<ref>https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2023/Pdf/G20234001.pdf</ref><br>182,321 (10.48%) in Vojvodina | |||

| | ] | |||

| | '']'' (which would have an area of 3,813 km<sup>2</sup> and a population of 253,977 people of which 44.4% Hungarians and 29% Serbs) | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flag|Slovakia}}<br />parts of southern ], see: ] | |||

| | 422,065 (7.7%)<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ethnic composition of Slovakia 2021 |url=http://pop-stat.mashke.org/slovakia-ethnic-loc2021.htm |access-date=5 July 2022}}</ref> | |||

| | ] | |||

| | {{center|—}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flag|Ukraine}} <br /> parts of ] in southwestern ], see: ] | |||

| | 156,566 (0.3%) in Ukraine<br>151,533 (12.09%) in Transcarpathia | |||

| | ] | |||

| | {{center|—}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090226163228/http://sebok1.adatbank.transindex.ro/legbelso.php3?nev=KozEu |date=2009-02-26 }}</ref>]] | |||

| During the Communist era, Marxist–Leninist ideology and Stalin's theory on nationalities considered nationalism to be a malady of a bourgeois capitalism. In Hungary, the minorities' question disappeared from the political agenda. Communist hegemony guaranteed a facade of inter-ethnic peace while failing to secure a lasting accommodation of minority interests in unitary states. | |||

| The fall of Communism aroused the expectations of Hungarian minorities in neighboring countries and left Hungary unprepared to deal with the issue. Hungarian politicians campaigned to formalize the rights of Hungarian minorities in neighboring countries, thus causing anxiety in the region. They secured agreements on the necessity for guaranteeing collective rights and formed new Hungarian minority organizations to promote cultural rights and political participation. In Romania, Slovakia, and Yugoslavia (now Serbia), former Communists secured popular legitimacy by accommodating nationalist tendencies that were hostile to minority rights. | |||

| The latest controversy caused by the government of ] is when Hungary took the presidency over the ] in 2011<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.eu2011.hu/ |title=(Home page) |access-date=2011-02-13 |publisher=Hungarian Presidency of The Council Of The European Union |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110202084151/http://www.eu2011.hu/ |archive-date=2011-02-02 }}</ref> when the "historical timeline" features was presented – among other cultural, historical and scientific symbols or images of Hungary – an 1848 map of ], when Budapest ruled over large swathes of its neighbors.<ref>{{cite news |title=Hungary in EU presidency 'history' carpet row |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-12194899 |publisher=] |date=2011-01-14 |access-date=2011-02-13}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Hungary in EU presidency 'history' carpet row |url=http://www.bucharestherald.ro/worldnews/43-worldnews/18952-hungary-in-eu-presidency-history-carpet-row |publisher=Bucharest Herald |date=2011-01-15 |access-date=2011-02-13 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110117173628/http://www.bucharestherald.ro/worldnews/43-worldnews/18952-hungary-in-eu-presidency-history-carpet-row |archive-date=2011-01-17 }}</ref> | |||

| In May 2020, Prime Minister ] created some waves in neighbouring nations with a historical map of the ], which he posted on ], before the annual mature exam for secondary school students.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://balkaninsight.com/2020/05/07/orbans-greater-hungary-map-creates-waves-in-neighbourhood/|title = Orban's 'Greater Hungary' Map Creates Waves in Neighbourhood|date = 7 May 2020}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.euronews.com/2020/05/08/viktor-orban-provokes-neighbours-with-historical-map-of-hungary-thecube|title = Viktor Orban provokes neighbours with historical map of Hungary|date = 8 May 2020}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2020/06/03/viktor-orbans-masterplan-to-make-hungary-greater-again/|title=Viktor Orbán's Masterplan to Make Hungary Greater Again|date=3 June 2020 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Hungary=== | |||

| The campaign materials of ] during the early 2010s contained maps of the pre-1920 Greater Hungary.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7I_pDb1O2EQC&q=%22pre-First+World+War+Greater+Hungary%22&pg=PT184|title=Europe for the Europeans: The Foreign and Security Policy of the Populist Radical Right|isbn=9781409498254|last1=Liang|first1=Christina Schori|date=28 March 2013|publisher=Ashgate Publishing }}</ref> | |||

| ===Slovakia=== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=August 2024}} | |||

| {{main article|Hungarians in Slovakia}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Under great pressure from the EU and NATO, Hungary signed a bilateral state treaty with Slovakia on ] in March 1995, aimed at resolving disputes concerning borders and minority rights. Its vague language, though, allows rival interpretations. One cause of conflict was the COE's Recommendation 1201 which stipulates the creation of autonomous self-government based on ethnic principles in areas where ethnic minorities represent a majority of the population. | |||

| The Hungarian Prime Minister insisted that the treaty protected the Hungarian minority as a "community". Slovakia accepted the 1201 Recommendation in the treaty, but denounced the concept of collective rights of minorities and political autonomy as "unacceptable and destabilizing". Slovakia finally ratified the treaty in March 1996 after the government attached a unilateral declaration that the accord would not provide for collective autonomy for Hungarians. The Hungarian government therefore refused to recognize the validity of the declaration. | |||

| ===Romania=== | |||

| {{see also|Székely autonomy initiatives}} | |||

| ] | |||

| After World War II, a ] was created in Transylvania, which encompassed most of the land inhabited by the ]. This region lasted until 1964 when the administrative reform divided Romania into the current counties. From 1947 until the 1989 ] and the death of ], a systematic ] of Hungarians took place, with several discriminatory provisions, denying them their cultural identity. This tendency started to abate after 1989, the question of ] remains a sensitive issue. | |||

| On 16 September 1996, after five years of negotiations, Hungary and Romania also signed a bilateral treaty, which had been stalled over the nature and extent of minority protection that Bucharest should grant to Hungarian citizens. Hungary dropped its demands for autonomy for ethnic minorities; in exchange, Romania accepted a reference to Recommendation 1201 in the treaty, but with a joint interpretive declaration that guarantees individual rights, but excludes collective rights and territorial autonomy based on ethnic criteria. These concessions were made in large measure because both countries recognized the need to improve good neighborly relations as a prerequisite for NATO membership. | |||

| ===Serbia=== | |||

| {{see also|Hungarian Regional Autonomy|Hungarians in Serbia}} | |||

| ] | |||

| There are five main ethnic Hungarian political parties in Serbia: | |||

| *], led by ] | |||

| *], led by ] | |||

| *], led by ] | |||

| *], led by ] | |||

| *], led by Bálint László | |||

| These parties are advocating the establishment of the territorial autonomy for Hungarians in the northern part of Vojvodina, which would include the municipalities with Hungarian majority (See ] for details). | |||

| ===Ukraine=== | |||

| {{main article|Hungarians in Ukraine}} | |||

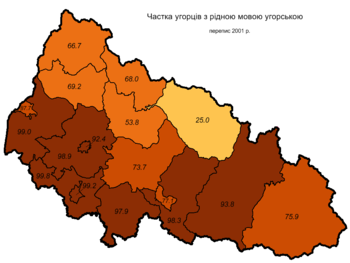

| ] by the 2001 census]] | |||

| By 2015, the Hungarian authorities announced that they had granted citizenship to around 100,000 ethnic ] in ]. Despite Ukraine's constitution stating that there is only one form of citizenship in the country, the Kyiv government generally overlooked the issuance of Hungarian passports in Zakarpattia for several years, as many of them also held dual citizenship. Since 2021, the only individuals legally barred from acquiring dual citizenship in Ukraine are civil servants. | |||

| In 2018, the Hungarian Cultural Federation in Transcarpathia (KMKSZ) requested to establish a separate Hungarian constituency by referring to Article 18 of the current Law "On Elections of People's Deputies", which states that electoral districts must be formed, including taking into account the residence of national minorities. Such a constituency, which is often called Pritysyansky (from the name of the Tisza River, along which the Hungarian minority lives along the Transcarpathia), already existed in the parliamentary elections in Ukraine in 1998 and virtually retained its limits in the 2002 elections, granting presence for the representants of the Hungarian minority in the Verkhovna Rada.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://zak.depo.ua/ukr/zak/ugorci-zakarpattya-prosyat-cvk-stvoriti-ugorskiy-viborchiy-okrug-20180719808299 |title=Угорці Закарпаття просять ЦВК створити угорський виборчий округ |date=2018-07-19 |website=zak.depo.ua |publisher=] |access-date=2019-05-21}}</ref> | |||

| The issue restarted during the election campaign of the presidential elections in Ukraine in the spring of 2019. László Brenzovics, the head of KMKSZ filed a lawsuit against the Central Election Commission of Ukraine for refusing to create the so-called Pritysyansky constituency – a separate constituency on the territory of 4 districts of Transcarpathia along the Tisza River, where the ethnic Hungarians are compact, allegedly for the purpose of electing their representative in the Verkhovna Rada. Preparing for the fact that the court is likely to support the legitimate refusal of the CEC, the Hungarians began to act at the level of the local councils of Transcarpathia.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mukachevo.net/ua/news/view/482568 |title=Брензович подав до суду на ЦВК через небажання створити угорський виборчий округ на Закарпатті |date=2019-03-22 |website=www.mukachevo.net |publisher=Mukachevo.net |access-date=2019-05-21}}</ref> | |||

| On 17 May, at a regular session of the Beregovo City Council, chairman of the largest pro-Hungarian faction of the Hungarian Democratic Federation in Ukraine (UDMSZ), Karolina Darcsi, – accused for anti-Ukrainian stance – planned to read the appeal of deputies to the CEC to create the Pritysyansky Hungarian constituency in Transcarpathia. However, in the absence of a quorum, the session of the city council never took place.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-polytics/2704913-ugorskij-viborcij-okrug-na-zakarpatti-golovni-nebezpeki.html |title=Угорський виборчий округ на Закарпатті: головні небезпеки |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190521181051/https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-polytics/2704913-ugorskij-viborcij-okrug-na-zakarpatti-golovni-nebezpeki.html |archive-date=2019-05-21 |date=2019-05-21 |website=www.ukrinform.ua |publisher=] |access-date=2019-05-21}}</ref> | |||

| The ] revived interest among Hungarian nationalists for annexing parts of Ukraine.<ref>{{cite news |title=Ukraine War Feeds Dreams of Hungarian Far-Right Reclaiming Lost Land |url=https://balkaninsight.com/2022/05/04/ukraine-war-feeds-dreams-of-hungarian-far-right-reclaiming-lost-land/ |access-date=4 May 2022 |work=Balkan Insight |date=4 May 2022}}</ref> | |||

| Most people in present-day Hungary reject annexation of lands in which people of other nations view the Treaty of Trianon as their liberation, though there is consensus in Hungary that the Trianon was not the right solution for the nationalities living in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy— especially for Hungarians. Nationalist organizations want to change borders and to create Greater Hungary, some by any means necessary. However, even among these groups there are differences: some want to include only areas with Hungarian ethnic majority, others propose the independence of ] as a multi ethinc-linguistic state similar to ], while the more extreme—a tiny minority within Hungary itself, but a larger minority among Hungarian minorities in neighbouring countries—want to restore Hungary's maximum historic borders regardless of ethnic compostion or the soverignty of neighboring countires. | |||

| On 27 January 2024 ] said at a conference that his party ] would lay claim to a ] in western Ukraine if the war led to Ukraine losing its statehood.<ref>{{Cite news |agency=Reuters |title=Hungary's Far Right Would Lay Claim To Neighboring Region If Ukraine Loses War |url=https://www.rferl.org/a/hungary-far-right-ukraine-region/32795184.html |access-date=2024-01-28 |work=RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| A similar, but usually less ambitious, Hungarian nationalism is often expressed through ethnic Hungarian political parties in neighboring countries and through movements such as that among some ] in Romania for an autonomous region within Transylvania named ], or among some Hungarians in Serbia for an autonomous region in northern part of Vojvodina (see: ]). | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| After World War II, a Hungarian Autonomous Region was created in Transylvania, which encompassed most of the land inhabited by the Székelys. This region lasted until 1964 when the administrative reform divided Romania into the current counties. According to some claims, from ] until the ] ] and the death of ], a systematic ] of Hungarians took place, with several discriminatory provisions, denying them their minority identity. This tendency started to abate after 1989, and has abated further with the granting of significant minority cultural rights as ] to join Hungary as a member of the ]. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == Sources == | |||

| Both during the Communist era and today, the Hungarian government has advocated for the rights of ethnic Hungarians living in surrounding countries to retain their Hungarian language and culture. In general, in this respect, relations—and treatment of Hungarian minorities—are better now than they were in Communist times. | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Taylor |first=A.J.P. |title=The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918 – A History of the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary |publisher=Hamish Hamilton |year=1948 |location=London}} | |||

| Recently, '']'', a Hungarian film based on revisionist ideas, was forbidden from being shown on Hungarian television, (although it was screened in a cinema and showed on a Romanian TV station), because of concern about how neighbouring countries would receive the revisionist perspective shown in this movie. | |||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| #Dr. Fedor Nikić, ''Mađarski imperijalizam'', Novi Sad - Srbinje, 2004. | |||

| *{{Cite book |last=Ambrosio|first=Thomas |year=2001 |title=Irredentism: Ethnic Conflict and International Politics |publisher=Praeger |isbn=978-0275972608}} | |||

| #Danilo Urošević, ''Srbi u logorima Mađarske'', Novi Sad, 1955. | |||

| == |

==Further reading== | ||

| * Badescu, Ilie. "Peacebuilding in an Era of State-Nations: The Europe of Trianon." ''Romanian Journal Of Sociological Studies'' 2 (2018): 87-100. | |||

| <references/> | |||

| * Balogh, Eva S. "Peaceful Revision: The Diplomatic Road to War." ''Hungarian Studies Review'' 10.1 (1983): 43- 51. | |||

| * Bihari, Peter. "Images of defeat: Hungary after the lost war, the revolutions and the Peace Treaty of Trianon." ''Crossroads of European histories: multiple outlooks on five key moments in the history of Europe'' (2006) pp: 165–171. | |||

| * Deák, Francis. ''Hungary at the Paris Peace Conference: The Diplomatic History of the Treaty of Trianon'' (Howard Fertig, 1942). | |||

| * Feischmidt, Margit. "Memory-Politics and Neonationalism: Trianon as Mythomoteur." Nationalities Papers 48.1 (2020): 130–143. Emphasizes current "Trianon Cult" and its impact on pushing Hungary to the far right. | |||

| * Jeszenszky, Géza. "The Afterlife of the Treaty of Trianon." ''The Hungarian Quarterly'' 184 (2006): 101–111. | |||

| * Király, Béla K. and László Veszprémy, eds. ''Trianon and East Central Europe: Antecedents and Repercussions'' (Columbia University Press, 1995). | |||

| * ] ''Hungary and Her Successors: The Treaty of Trianon and Its Consequences 1919-1937'' (1937) | |||

| * Menyhért, Anna. "The Image of the 'Maimed Hungary' in 20th Century Cultural Memory and the 21st Century Consequences of an Unresolved Collective Trauma: The Impact of the Treaty of Trianon." Environment, Space, Place 8.2 (2016): 69–97. {{dead link|date=July 2022|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}} | |||

| * Pastor, Peter. "Major trends in Hungarian foreign policy from the collapse of the monarchy to the peace treaty of Trianon." ''Hungarian Studies. A Journal of the International Association for Hungarian Studies and Balassi Institute'' 17.1 (2003): 3-12. | |||

| * Aliaksandr Piahanau, ''Hungary's Policy Towards Czechoslovakia, 1918-36''. PhD dissertation. Toulouse University, 2018 | |||

| * Putz, Orsolya. ''Metaphor and National Identity: Alternative conceptualization of the Treaty of Trianon'' (John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2019). | |||

| * Romsics, Ignác. ''The Dismantling of Historic Hungary: The Peace Treaty of Trianon, 1920'' (Boulder, CO: Social Science Monographs, 2002). | |||

| * Romsics, Ignác. "The Trianon Peace Treaty in Hungarian Historiography and Political Thinking." ''East European Monographs'' (2000): 89-105. | |||

| * Várdy, Steven Béla. "The Impact of Trianon upon Hungary and the Hungarian Mind: The Nature of Interwar Hungarian Irredentism." ''Hungarian Studies Review'' 10.1 (1983): 21+. | |||

| * Wojatsek, Charles. ''From Trianon to the First Vienna Arbitral Award: The Hungarian Minority in the First Czechoslovak Republic, 1918-1938'' (Montreal: Institute of Comparative Civilizations, 1980). | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Dupcsik|first=Csaba|title=Történelem IV. XX. század|year=2001|publisher=Műszaki Könyvkiadó|location=Budapest|isbn=978-9631628142|author2=Repárszky, Ildikó|language=hu}} | |||

| {{Hungary articles}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Irredentism}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Europe topic|Irredentism of}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Pan-nationalist concepts}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:48, 26 December 2024

Political ideas to reunite Historic Hungary For other uses, see Greater Hungary.

Hungarian irredentism or Greater Hungary (Hungarian: Nagy-Magyarország) are irredentist political ideas concerning redemption of territories of the historical Kingdom of Hungary. The objective is to at least to regain control over Hungarian-populated areas in Hungary's neighbouring countries. Hungarian historiography uses the term "Historic Hungary" (Hungarian: történelmi Magyarország). "Whole Hungary" (Hungarian: Egész-Magyarország) is also commonly used by supporters of this ideology.

The Treaty of Trianon defined the current borders of Hungary and, compared against the claims of the pre-war Kingdom, post-Trianon Hungary had approximately 72% less land stake and about two-thirds fewer inhabitants, almost 5 million of these being of Hungarian ethnicity. However, only 54% of the inhabitants of the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary were Hungarians before World War I. Following the treaty's instatement, Hungarian leaders became inclined towards revoking some of its terms. This political aim gained greater attention and was a serious national concern up through the Second World War.

After World War I, despite the "self-determination of peoples" idea of the Allied Powers, only one plebiscite was permitted (later known as the Sopron plebiscite) to settle disputed borders on the former territory of the Kingdom of Hungary, settling a smaller territorial dispute between the First Austrian Republic and the Kingdom of Hungary, because some months earlier, the Rongyos Gárda launched a series of attacks to oust the Austrian forces that entered the area. During the plebiscite in late 1921, the polling stations were supervised by British, French, and Italian army officers of the Allied Powers.

Irredentism in the 1930s led Hungary to form an alliance with Hitler's Nazi Germany. Eva S. Balogh states: "Hungary's participation in World War II resulted from a desire to revise the Treaty of Trianon so as to recover territories lost after World War I. This was the basis for Hungary's interwar foreign policy."

Hungary, supported by the Axis Powers, was successful temporarily in gaining some regions of the former Kingdom by the First Vienna Award in 1938 (southern Czechoslovakia with mainly Hungarians) and the Second Vienna Award in 1940 (Northern Transylvania with an ethnically mixed population), and through military campaign gained regions of Carpathian Ruthenia in 1939 and (ethnically mixed) Bačka, Baranja, Međimurje, and Prekmurje in 1941 (Hungarian occupation of Yugoslav territories). Following the close of World War II, the borders of Hungary as defined by the Treaty of Trianon were restored, except for three Hungarian villages that were transferred to Czechoslovakia. These villages are today administratively a part of Bratislava.

History

Background

The independent Kingdom of Hungary was established in 1000 AD, and remained a regional power in Central Europe until Ottoman Empire conquered its central part in 1526 following the Battle of Mohács. In 1541 the territory of the former Kingdom of Hungary was divided into three portions: in the west and north, Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary retained its existence under Habsburg rule; the Ottomans controlled the south-central parts of former Kingdom of Hungary; while in the east, the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom (later the Principality of Transylvania) was formed as a semi-independent entity under Ottoman suzerainty. After the Ottoman conquest in the Kingdom of Hungary, the ethnic structure of the kingdom started to become more multi-ethnic because of immigration to the sparsely populated areas. Between 1683 and 1717, the Habsburg monarchy conquered all the Ottoman territories that were part of the Kingdom of Hungary before 1526, and incorporated some of these areas into the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary.

After a suppressed uprising in 1848–1849, the Kingdom of Hungary and its diet were dissolved, and territory of the Kingdom of Hungary was divided into 5 districts, which were Pest & Ofen, Ödenburg, Preßburg, Kaschau and Großwardein, directly controlled from Vienna while Croatia, Slavonia, and the Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar were separated from the Kingdom of Hungary between 1849 and 1860. This new centralized rule, however, failed to provide stability, and in the wake of military defeats the Austrian Empire was transformed into Austria-Hungary with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, by which Kingdom of Hungary became one of two constituent entities of the new dual monarchy with self-rule in its internal affairs.

A considerable number of the figures who are today considered important in Hungarian culture were born in what are today parts of Romania, Slovakia, Poland, Ukraine, and Austria (see List of Hungarians who were born outside present-day Hungary). Names of Hungarian dishes, common surnames, proverbs, sayings, folk songs etc. also refer to these rich cultural ties. After 1867, the non-Hungarian ethnic groups were subject to assimilation and Magyarization.

Before World War I, only three European countries declared ethnic minority rights, and enacted minority-protecting laws: the first was Hungary (1849 and 1868), the second was Austria (1867), and the third was Belgium (1898). In contrast, the legal systems of other pre-WW1 era European countries did not allow the use of European minority languages in primary schools, in cultural institutions, in offices of public administration and at the legal courts.

Among the most notable policies was the promotion of the Hungarian language as the country's official language (replacing Latin and German); however, this was often at the expense of West Slavic languages and the Romanian language. The new government of autonomous Kingdom of Hungary took the stance that Kingdom of Hungary should be a Hungarian nation state, and that all other peoples living in the Kingdom of Hungary—Germans, Jews, Romanians, Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenes and other ethnicities—should be assimilated. (The Croats were to some extent an exception to this, as they had a fair degree of self-government within Croatia-Slavonia, a dependent kingdom within the Kingdom of Hungary.)

World War I

Main article: Treaty of Trianon

The peace treaties signed after the First World War redefined the national borders of Europe. The dissolution of Austria-Hungary, after its defeat in the First World War, gave an opportunity for the subject nationalities of the old Monarchy to all form their own nation states (however, most of the resulting states nevertheless became multi-ethnic states comprising several nationalities). The Treaty of Trianon of 1920 defined borders for the new Hungarian state: in the north, the Slovak and Ruthene areas, including Hungarian majority areas became part of the new state of Czechoslovakia. Transylvania and most of the Banat became part of Romania, while Croatia-Slavonia and the other southern areas became part of the new state of Yugoslavia.

The arguments of Hungarian irredentists for their goal were: the presence of Hungarian majority areas in the neighboring countries, perceived historical traditions of the Kingdom of Hungary, or the perceived geographical unity and economic symbiosis of the region within the Carpathian Basin, although some Hungarian irredentists preferred to regain only ethnically Hungarian majority areas surrounding Hungary.

Post-Trianon Hungary had about half of the population of the former Kingdom. The population of the territories of the Kingdom of Hungary that were not assigned to the post-Trianon Hungary had, in total, non-Hungarian majority, although they included a sizable proportion of ethnic Hungarians and Hungarian majority areas. According to Károly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi, the ethnic composition (by their native language) in 1910 (note: three-quarters of the Jewish population stated Hungarian as their mother tongue, and the rest, German, in the absence of Yiddish as an option):

| Region | Hungarians | Germans | Romanians | Serbs | Croats | Ruthenians | Slovaks | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transylvania | 31.7% | 10.5% | 54.0% | 0.9% | 0.6% | Hungarians are concentrated in Székely Land (Hungarian majority), while as well significant in the border areas. | ||

| Vojvodina | 28.1% | 21.4% | 5.0% | 33.8% | 6.0% | 0.9% | 3.7% | |

| Transcarpathia | 30.6% | 10.6% | 1.9% | 54.5% | 1.0% | 1.0% Slovaks and Czechs | ||

| Slovakia | 30.2% | 6.8% | 3.5% | 57.9% | with Hungarians concentrated in the south, which has a Hungarian majority today. | |||

| Burgenland | 9.0% | 74.4% | 15% | |||||

| Croatia-Slavonia | 4.1% | 5.1% | 24.6% | 62.5% |

Trianon thus defined Hungary's new borders in a way that made ethnic Hungarians the overwhelmingly absolute majority in the country. Almost 3 million ethnic Hungarians remained outside the borders of post-Trianon Hungary. A considerable number of non-Hungarian nationalities remained within the new borders of Hungary, the largest of which were Germans (Schwabs) with 550,062 people (6.9%). Also, the number of Hungarian Jews remained within the new borders was 473,310 (5.9% of the total population), compared with 911,227 (5.0%), in 1910.

Aftermath

After the Treaty of Trianon, a political concept known as Hungarian Irredentism became popular in Hungary. The Treaty of Trianon was an injury for the Hungarian people and Hungarian nationalists have created an ideology with the political goal of the restoration of borders of historical pre-Trianon Kingdom of Hungary.

The justification for this aim usually followed the fact that two-thirds of the country's area was taken by the neighboring countries with approximately 3 million Hungarians living in these territories. Several municipalities that had purely ethnic Hungarian population were excluded from post-Trianon Hungary, which had borders designed to cut most economic regions (Szeged, Pécs, Debrecen etc.) in half, and keep railways on the other side. Moreover, five of the pre-war kingdom's ten largest cities were drawn into other countries.

All interwar governments of Hungary were obsessed with recovering at least the Magyar-populated territories outside Hungary. In 1934, Gyula Gömbös, on the request of Benito Mussolini, presented the territories which he wished to reannex peacefully.

Near realization

Hungary's government allied itself with Nazi Germany during World War II in exchange for assurances that Greater Hungary's borders would be restored. This goal was partially achieved when Hungary reannexed territories from Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia at the outset of the war. These annexations were affirmed under the Munich Agreement (1938), two Vienna Awards (1938 and 1940), and aggression against Yugoslavia (1941), the latter achieved one week after the German army had already invaded Yugoslavia.

The percentage of Hungarian speakers was 84% in southern Czechoslovakia and 15% in the Sub-Carpathian Rus.

In Northern Transylvania, the Romanian census from 1930 counted 38% Hungarians and 49% Romanians, while the Hungarian census from 1941 counted 53.5% Hungarians and 39.1% Romanians.

Ferenc Szálasi, leader of Hungary from 16 October 1944 envisioned the creation a "Carpathian-Danubian" federation where nationalism is region based ("connationalism") and other peoples are willing to join independently. He excluded the Jews who were not "rooted in" the Carpathian Basin, so they had to be relocated into a Jewish state, but not killed ("asemitism") according to him. Szálasi called his ideology Hungarism.

The Yugoslav territory occupied by Hungary (including Bačka, Baranja, Međimurje and Prekmurje) had approximately one million inhabitants, including 543,000 Yugoslavs (Serbs, Croats and Slovenes), 301,000 Hungarians, 197,000 Germans, 40,000 Slovaks, 15,000 Rusyns, and 15,000 Jews. In Bačka region only, the 1931 census put the percentage of the speakers of Hungarian at 34.2%, while one of interpretations of later Hungarian census from 1941 states that, 45,4% or 47,2% declared themselves to be Hungarian native speakers or ethnic Hungarians (this interpretation is provided by authors Károly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi. The 1941 census, however, did not recorded ethnicity of the people, but only mother/native tongue ). Population of entire Bačka numbered 789,705 inhabitants in 1941. This means that from the beginning of the occupation, the number of Hungarian speakers in Bačka increased by 48,550, while the number of Serbian speakers decreased by 75,166.

The establishment of Hungarian rule met with insurgency on part of the non-Hungarian population in some places and retaliation of the Hungarian forces was labelled war crimes such as Ip and Treznea massacres in Northern Transylvania (directed against Romanians) or Bačka, where Hungarian military between 1941 and 1944 deported or killed 19,573 civilians, mainly Serbs and Jews, but also Hungarians who did not collaborate with the new authorities. About 56,000 people were also expelled from Bačka.

The Jewish population of Hungary and the areas it occupied were partly diminished as part of the Holocaust. Tens of thousands of Romanians fled from Hungarian-ruled Northern Transylvania, and vice versa. After the war the areas were returned to neighboring countries and Hungary's territory was slightly further reduced by ceding three villages south of Bratislava to Slovakia. Some Hungarians were killed both in Yugoslavia by Yugoslav partisans (the exact number of ethnic Hungarians killed by Yugoslav partisans is not clearly established and estimates range from 4,000 to 40,000; 20,000 is often regarded as most probable), and in Transylvania by the Maniu Guard towards the end of World War II.

Modern era

In 2010, Hungary changed its citizenship legislation, thus any subject who could certify ancestry on any territory historically belonged to Hungary may be as well granted Hungarian citizenship, if they are able to speak the Hungarian language (the Csangos may have an exception of the first criteria, as the area they live was not part of Hungary, regarding them also ecclesial documents may be accepted).

The following table lists areas with Hungarian population in neighboring countries today:

| Country, region | Hungarians | Cultural, political center | Proposed autonomy |

parts of Transylvania (mainly Harghita, Covasna and part of Mureș counties, Central Romania), see: Hungarians in Romania |

1,227,623 (6.5%) in Romania 1,216,666 (17.9%) in Transylvania |

Târgu Mureș Cluj-Napoca |

Székely Land (which would have an area of 13,000 km and a population of 809,000 people of which 75.65% Hungarians) |

parts of Vojvodina in northern Serbia, see: Hungarians in Serbia |

184,442 (2.77%) in Serbia 182,321 (10.48%) in Vojvodina |

Subotica | Hungarian Regional Autonomy (which would have an area of 3,813 km and a population of 253,977 people of which 44.4% Hungarians and 29% Serbs) |

parts of southern Slovakia, see: Hungarians in Slovakia |

422,065 (7.7%) | Komárno | — |

parts of Zakarpattia Oblast in southwestern Ukraine, see: Hungarians in Ukraine |

156,566 (0.3%) in Ukraine 151,533 (12.09%) in Transcarpathia |

Berehove | — |

During the Communist era, Marxist–Leninist ideology and Stalin's theory on nationalities considered nationalism to be a malady of a bourgeois capitalism. In Hungary, the minorities' question disappeared from the political agenda. Communist hegemony guaranteed a facade of inter-ethnic peace while failing to secure a lasting accommodation of minority interests in unitary states.

The fall of Communism aroused the expectations of Hungarian minorities in neighboring countries and left Hungary unprepared to deal with the issue. Hungarian politicians campaigned to formalize the rights of Hungarian minorities in neighboring countries, thus causing anxiety in the region. They secured agreements on the necessity for guaranteeing collective rights and formed new Hungarian minority organizations to promote cultural rights and political participation. In Romania, Slovakia, and Yugoslavia (now Serbia), former Communists secured popular legitimacy by accommodating nationalist tendencies that were hostile to minority rights.

The latest controversy caused by the government of Viktor Orbán is when Hungary took the presidency over the EU in 2011 when the "historical timeline" features was presented – among other cultural, historical and scientific symbols or images of Hungary – an 1848 map of Greater Hungary, when Budapest ruled over large swathes of its neighbors.

In May 2020, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán created some waves in neighbouring nations with a historical map of the Kingdom of Hungary, which he posted on Facebook, before the annual mature exam for secondary school students.

Hungary

The campaign materials of Jobbik during the early 2010s contained maps of the pre-1920 Greater Hungary.

Slovakia

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Under great pressure from the EU and NATO, Hungary signed a bilateral state treaty with Slovakia on Good Neighborly Relations and Friendly Cooperation in March 1995, aimed at resolving disputes concerning borders and minority rights. Its vague language, though, allows rival interpretations. One cause of conflict was the COE's Recommendation 1201 which stipulates the creation of autonomous self-government based on ethnic principles in areas where ethnic minorities represent a majority of the population.

The Hungarian Prime Minister insisted that the treaty protected the Hungarian minority as a "community". Slovakia accepted the 1201 Recommendation in the treaty, but denounced the concept of collective rights of minorities and political autonomy as "unacceptable and destabilizing". Slovakia finally ratified the treaty in March 1996 after the government attached a unilateral declaration that the accord would not provide for collective autonomy for Hungarians. The Hungarian government therefore refused to recognize the validity of the declaration.

Romania

See also: Székely autonomy initiatives

After World War II, a Hungarian Autonomous Region was created in Transylvania, which encompassed most of the land inhabited by the Székelys. This region lasted until 1964 when the administrative reform divided Romania into the current counties. From 1947 until the 1989 Romanian Revolution and the death of Nicolae Ceaușescu, a systematic Romanianization of Hungarians took place, with several discriminatory provisions, denying them their cultural identity. This tendency started to abate after 1989, the question of Székely autonomy remains a sensitive issue.

On 16 September 1996, after five years of negotiations, Hungary and Romania also signed a bilateral treaty, which had been stalled over the nature and extent of minority protection that Bucharest should grant to Hungarian citizens. Hungary dropped its demands for autonomy for ethnic minorities; in exchange, Romania accepted a reference to Recommendation 1201 in the treaty, but with a joint interpretive declaration that guarantees individual rights, but excludes collective rights and territorial autonomy based on ethnic criteria. These concessions were made in large measure because both countries recognized the need to improve good neighborly relations as a prerequisite for NATO membership.

Serbia

See also: Hungarian Regional Autonomy and Hungarians in Serbia

There are five main ethnic Hungarian political parties in Serbia:

- Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians, led by István Pásztor

- Democratic Fellowship of Vojvodina Hungarians, led by Áron Csonka

- Democratic Party of Vojvodina Hungarians, led by András Ágoston

- Civic Alliance of Hungarians, led by László Rác Szabó

- Movement of Hungarian Hope, led by Bálint László

These parties are advocating the establishment of the territorial autonomy for Hungarians in the northern part of Vojvodina, which would include the municipalities with Hungarian majority (See Hungarian Regional Autonomy for details).

Ukraine

Main article: Hungarians in Ukraine

By 2015, the Hungarian authorities announced that they had granted citizenship to around 100,000 ethnic Hungarians in Transcarpathia. Despite Ukraine's constitution stating that there is only one form of citizenship in the country, the Kyiv government generally overlooked the issuance of Hungarian passports in Zakarpattia for several years, as many of them also held dual citizenship. Since 2021, the only individuals legally barred from acquiring dual citizenship in Ukraine are civil servants.

In 2018, the Hungarian Cultural Federation in Transcarpathia (KMKSZ) requested to establish a separate Hungarian constituency by referring to Article 18 of the current Law "On Elections of People's Deputies", which states that electoral districts must be formed, including taking into account the residence of national minorities. Such a constituency, which is often called Pritysyansky (from the name of the Tisza River, along which the Hungarian minority lives along the Transcarpathia), already existed in the parliamentary elections in Ukraine in 1998 and virtually retained its limits in the 2002 elections, granting presence for the representants of the Hungarian minority in the Verkhovna Rada.

The issue restarted during the election campaign of the presidential elections in Ukraine in the spring of 2019. László Brenzovics, the head of KMKSZ filed a lawsuit against the Central Election Commission of Ukraine for refusing to create the so-called Pritysyansky constituency – a separate constituency on the territory of 4 districts of Transcarpathia along the Tisza River, where the ethnic Hungarians are compact, allegedly for the purpose of electing their representative in the Verkhovna Rada. Preparing for the fact that the court is likely to support the legitimate refusal of the CEC, the Hungarians began to act at the level of the local councils of Transcarpathia.

On 17 May, at a regular session of the Beregovo City Council, chairman of the largest pro-Hungarian faction of the Hungarian Democratic Federation in Ukraine (UDMSZ), Karolina Darcsi, – accused for anti-Ukrainian stance – planned to read the appeal of deputies to the CEC to create the Pritysyansky Hungarian constituency in Transcarpathia. However, in the absence of a quorum, the session of the city council never took place.

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine revived interest among Hungarian nationalists for annexing parts of Ukraine.

On 27 January 2024 László Toroczkai said at a conference that his party Mi Hazánk Mozgalom would lay claim to a Hungarian-populated region in western Ukraine if the war led to Ukraine losing its statehood.

See also

- Trianon Syndrome

- Little Entente

- Croatian–Romanian–Slovak friendship proclamation

- Međimurje under Hungarian rule

Sources

- Taylor, A.J.P. (1948). The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918 – A History of the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary. London: Hamish Hamilton.

References

- ^ Fenyvesi, Anna (2005). Hungarian language contact outside Hungary: studies on Hungarian as a minority language. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 2. ISBN 90-272-1858-7. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- "Treaty of Trianon". Encyclopædia Britannica. 9 February 2024.

- A magyar szent korona országainak 1910. évi népszámlálása. Első rész. A népesség főbb adatai. (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyar Kir. Központi Statisztikai Hivatal (KSH). 1912.

- Anstalt G. Freytag & Berndt (1911). Geographischer Atlas zur Vaterlandskunde an der österreichischen Mittelschulen. Vienna: K. u. k. Hof-Kartographische. "Census December 31st 1910"

- "HUNGARY". Hungarian Online Resources (Magyar Online Forrás). Archived from the original on 2010-11-24. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- Richard C. Hall (2014). War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia. ABC-CLIO. p. 309. ISBN 9781610690317.

- Irredentist and National Questions in Central Europe, 1913–1939: Hungary, 2v, Volume 5, Part 1 of Irredentist and National Questions in Central Europe, 1913–1939 Seeds of conflict. Kraus Reprint. 1973. p. 69.

- Eva S. Balogh, "Peaceful Revision: The Diplomatic Road to War." Hungarian Studies Review 10.1 (1983): 43-51. online

- Józsa Hévizi (2004): Autonomies in Hungary and Europe, A COMPARATIVE STUDY, The Regional and Ecclesiastic Autonomy of the Minorities and Nationality Groups>

- Hungary before 1918 Silber, Michael K. 2010. YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe

- ^ Kocsis, Károly (1996–2000). "V. Népesség és társadalom – Demográfiai jellemzők és folyamatok – Magyarország népessége – Anyanyelv, nemzetiség alakulása" [V. Population and Society – Demographic Characteristics and Processes – Hungary's Population – Development of Mother Tongue and Nationality]. In István, Kollega Tarsoly (ed.). Magyarország a XX. században – II. Kötet: Természeti környezet, népesség és társadalom, egyházak és felekezetek, gazdaság [Hungary in the 20th century – II. Volume: Natural Environment, Population and Society, Churches and Denominations, Economy] (in Hungarian). Szekszárd: Babits Kiadó. ISBN 963-9015-08-3.

- Kocsis, Károly. "Series of Ethnic Maps of the Carpatho-Pannonian Area".

- Árpád, Varga E. (1999). Népszámlálások Erdély területén 1850 és 1910 között [Censuses in Transylvania between 1850 and 1910] (PDF). Bucharest.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "1910. ÉVI NÉPSZÁMLÁLÁS 1. A népesség főbb adatai községek és népesebb puszták, telepek szerint (1912) | Könyvtár | Hungaricana".

- Taylor 1948, p. 268.

- Kocsis, Károly; Bottlik, Zsolt. The Changing Ethnic Patterns on the Present-Day Territory Of Hungary (PDF).

- Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi (1995). "Table 14. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Transylvania (1880–1992)". Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-04-5. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi (1995). "Table 21. Ethnic structure of the population of the present territory of Vojvodina (1880–1991)". Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-04-5. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- Karoly Kocsis and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi (1995). "Table 11. Ethnic structure of the population on the present territory of Transcarpathia (1880..1989)". Hungarian minorities in the Carpathian Basin: A study in ethnic geography. Matthias Corvinus Publishing. ISBN 1-882785-04-5. Retrieved 2011-02-28.