| Revision as of 23:06, 22 October 2006 editArmadilloFromHell (talk | contribs)12,402 edits Revert to revision 83018583 dated 2006-10-22 15:59:29 by Stevewk using popups← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:00, 20 December 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,402,670 edits Altered url. URLs might have been anonymized. Add: authors 1-1. Removed parameters. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Jay8g | #UCB_toolbar | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Form of government}} | |||

| :''This article concentrates on the several ] of real states and countries that have been termed '''republic''', for all other uses see: ]'' | |||

| {{About|the form of government|the political ideology|Republicanism|other uses}} | |||

| {{ActiveDiscuss}} | |||

| {{pp-pc}} | |||

| {{Forms of government}} | |||

| {{Basic Forms of government}} | |||

| In a broad definition, a '''republic''' is a ] or ], the sovereignty of which is based on popular consent, and the governance of which is based on popular representation and control. Several definitions, including that of the '']'', stress the importance of ] and the rule of law as part of the requirements for a republic. Many general dictionaries indicate in their primary definitions, that a republic features "a chief of state who is not a monarch and who in modern times is usu. a president."<ref>"Republic," ''Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition'', (Springfield, Mass.: Merriam-Webster Inc., 2004), 1058. A republic contrasts with a dictatorship or other autocracy, but not necessarily with a monarchy, if the latter be of the ''constitutional'' variety, i.e., based on a body of fundamental law. In such a government, as England/Great Britain following its Revolution of 1688-89, we find a "monarchy" in name only, since the government then came under popular consent and control, and with executive authority strictly circumscribed. Such a monarchy may be considered a ''de facto'' republic.</ref> | |||

| Often ''republics'' and '']'' are described as mutually exclusive,<ref name=Machiavelli>In the opening chapter of '']'' ] describes ''republics'' and ''monarchies'' as mutually exclusive, with republics including both democracies and aristocracies. But even Machiavelli could not always adhere to this definition, not even in ''The Prince''. For example, when he tries to characterise the form of government of the ] in the 11th chapter of that book, he points out that usual methods and distinctions are not applicable for analysing such a state.</ref>but such a characterization is blurred by some borderline issues. For example while the distinction between ''monarchy'' and ''republic'' was not always made as it is in modern times, such a distinction depends very much on the concept of a ''monarch'', which itself has various definitions, thereby frustrating attempts to clarify the meaning of its apparent opposite, the ''republic''. | |||

| A '''republic''', based on the ] phrase '']'' ('public affair'), is a ] in which ] rests with the ] through their <!-- Do not change this to say that a republic is a form of government where _elected_ representatives of the people hold power. "Republic" in the classical sense means a country that isn't a monarchy.--> ]—in contrast to a ].<ref name="OED">{{Cite web|title=Republic {{!}} Definition of Republic by the Oxford English Dictionary|url=https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/163158|access-date=2022-05-10|website=Oxford English Dictionary|language=en|quote=A state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy. Also: a government, or system of government, of such a state; a period of government of this type. The term is often (especially in the 18th and 19th centuries) taken to imply a state with a democratic or representative constitution and without a hereditary nobility, but more recently it has also been used of autocratic or dictatorial states not ruled by a monarch. It is now chiefly used to denote any non-monarchical state headed by an elected or appointed president.}}</ref><ref name="M-W">{{Cite web|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/republic|title=Definition of Republic|website=Merriam-Webster Dictionary|language=en-US|access-date=2017-02-18|quote=a government having a chief of state who is not a monarch}}</ref> Although a republic is most often a single ], ] entities that have governments that are republican in nature may be referred to as republics. | |||

| In his 1787 book, "]," the American founder and second President of the United States, ] used the definition of "republic" in ]'s 1755 "]" ("A government of more than one person"), but in the same book, and in several other writings, Adams made it clear that he thought of the British state as a republic because the executive, though single and called "king," had to obey laws made with the concurrence of the legislature: | |||

| Representation in a republic may or may not be freely elected by the general citizenry. In many historical republics, representation has been based on personal status and the role of elections has been limited. This remains true today; among the ] states that use ''republic'' in their official names {{as of|2017|lc=y}}, and other states formally constituted as republics, are states that narrowly constrain both the right of representation and the process of election. | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| If Aristotle, Livy, and Harrington knew what a republic was, the British constitution is much more like a republic than an empire. They define a republic to be a government of laws, and not of men. If this definition is just, the British constitution is nothing more or less than a republic, in which the king is first magistrate. This office being hereditary, and being possessed of such ample and splendid prerogatives, is no objection to the government's being a republic, as long as it is bound by fixed laws, which the people have a voice in making, and a right to defend.<ref>John Adams, "Novanglus," ''Boston Gazette'', 6 March 1775; ''The Papers of John Adams'', vol. 7, p. 314.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| The term developed its modern meaning in reference to the constitution of the ancient ], lasting from the ] in 509 ] to the establishment of the ] in 27 BC. This ] was characterized by a ] composed of wealthy ] wielding significant influence; several popular ] of all free citizens, possessing the power to elect magistrates from the populace and pass laws; and a ] with varying types of civil and political authority. | |||

| The detailed organization of republics' governments can vary widely. The first section of this article gives an overview of the distinctions that characterise different ''types'' of non-fictional republics. The second section of the article gives short profiles of some of the most influential republics, by way of illustration. A more comprehensive ] appears in a separate article. The third section is about how republics are approached as state organisations in ]: in political theory and political science, the term "republic" is generally applied to a ] where the government's ] depends solely on the consent, however nominal, of the people governed. | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| ==Characteristics of republics== | |||

| {{See also|Res publica|Civitas}} | |||

| ===Heads of state=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In most modern republics the ] is termed ]. Other titles that have been used are ], ], ] and many others. In republics that are also ] the head of state is appointed as the result of an election. This election can be indirect, such as if a council of some sort is elected by the people, and this council then elects the head of state. In these kinds of republics the usual term for a president is in the range of four to six years. In some countries the ] limits the number of terms the same person can be elected as president. | |||

| The term originates from the Latin translation of ] word '']''. ], among other Latin writers, translated ''politeia'' into Latin as '']'', and it was in turn translated by Renaissance scholars as ''republic'' (or similar terms in various European languages).<ref>{{cite web |title=Republic |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/republic |website=Merriam Webster |publisher=Merrium-Webster Inc. |access-date=5 June 2019}}</ref> The term can literally be translated as 'public matter'.<ref name=Ideas2099>"Republic"j, ''New Dictionary of the History of Ideas''. Ed. ]. Vol. 5. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2005. p. 2099</ref> It was used by Roman writers to refer to the state and government, even during the period of the ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|last1=Lewis|first1=Charlton T.|first2=Charles |last2=Short |title=res, II.K|encyclopedia=]|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|year=1879|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0059%3Aentry%3Dres|access-date=August 14, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| If the head of state of a republic is at the same time the ], this is called a ] (example: ]). In ]s, where the head of state is not the same person as the ], the latter is usually termed ], ] or ]. Depending on what the president's specific duties are (for example, advisory role in the formation of a government after an election), and varying by convention, the president's role may range from the ceremonial and apolitical to influential and highly political. The Prime Minister is responsible for managing the policies and the central government. The rules for appointing the president and the leader of the government, in some republics permit the appointment of a president and a prime minister who have opposing political convictions: in ], when the members of the ruling ] and the president come from opposing political factions, this situation is called ]. In countries such as ] and ], however, the president needs to be strictly non-partisan. | |||

| The term ''politeia'' can be translated as ], ], or ], and it does not necessarily imply any specific type of regime as the modern word ''republic'' sometimes does. One of ]'s major works on political philosophy, usually known in English as '']'', was titled ''Politeia''. However, apart from the title, modern translations are generally used.<ref>]. ''The Republic''. Basic Books, 1991. pp. 439–40</ref> ] was apparently the first classical writer to state that the term ''politeia'' can be used to refer more specifically to one type of ''politeia'', asserting in Book III of his '']'': "When the citizens at large govern for the public good, it is called by the name common to all governments (''to koinon onoma pasōn tōn politeiōn''), government (''politeia'')". In later Latin works the term ''republic'' can also be used in a general way to refer to any regime, or to refer specifically to governments which work for the public good.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences-and-law/political-science-and-government/political-science-terms-and-concepts/republic|title=Republic {{!}} Encyclopedia.com|website=www.encyclopedia.com|language=en|access-date=2018-10-20}}</ref> | |||

| In some countries, like ] and ], the head of state is not a single person but a committee (council) of several persons holding that office. The ] had two ]s, appointed for a year by the ]. During the year of their consulship each consul would in turn be head of state for a month at a time, thus alternating the office of ] (the consul in power) and of ] (the subordinate consul who retained some independence, and held certain veto powers over the consul maior) for their joint term. | |||

| In medieval ], a number of city states had ] or ] based governments. In the late Middle Ages, writers such as ] described these states using terms such as ''libertas populi'', a free people. The terminology changed in the 15th century as the renewed interest in the writings of ] caused writers to prefer classical terminology. To describe non-monarchical states, writers (most importantly, ]) adopted the Latin phrase '']''.<ref>Rubinstein, Nicolai. "Machiavelli and Florentine Republican Experience" in ''Machiavelli and Republicanism'' Cambridge University Press, 1993.</ref> | |||

| Republics can be led by a head of state that has many of the characteristics of a monarch: not only do some republics install a president for life, and invest such president with powers beyond what is usual in a ], examples such as the post-1970 ] show that such a presidency can apparently be made hereditary. Historians disagree when the Roman Republic turned into ]: the reason is that the first ]s were given their head of state powers gradually in a government system that in appearance did not originally much differ from the Roman Republic<ref>], '']'' I,1-15.</ref>. | |||

| While Bruni and ] used the term to describe the states of Northern Italy, which were not monarchies, the term ''res publica'' has a set of interrelated meanings in the original Latin. In subsequent centuries, the English word '']'' came to be used as a translation of ''res publica'', and its use in English was comparable to how the Romans used the term ''res publica''.<ref name=Haakonssen>Haakonssen, Knud. "Republicanism." ''A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy''. Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit. eds. Cambridge: Blackwell, 1995.</ref> Notably, during ] of ] the word ''commonwealth'' was the most common term to call the new monarchless state, but the word ''republic'' was also in common use.<ref name=Kingsxxiii>{{Harvcoltxt|Everdell|2000}} p. xxiii.</ref> | |||

| Similarly, if taking the broad definition of republic above (see first paragraph), countries usually qualified as monarchies can have many traits of a republic in terms of form of government. The political power of monarchs can be non-existent, limited to a purely ceremonial function or the "control of the people" can be exerted to the extent that they appear to have the power to have their monarch replaced by another one<ref>Example: ] replaced by ] in ] under popular pressure.</ref>. | |||

| == History == | |||

| The often assumed "mutual exclusiveness" of monarchies and republics as forms of government<ref name=Machiavelli/> is thus not to be taken too literally, and largely depends on circumstances: | |||

| While the philosophical terminology developed in ] and ], as already noted by ] there was already a long history of city states with a wide variety of constitutions, not only in Greece but also in the ]. After the classical period, during the ], many free cities developed again, such as ]. | |||

| * ] might try to give themselves a democratic tenure by calling themselves president (or ] or ] in the case of ]), and the form of government of their country "republic", instead of using a monarchic based terminology<ref>For instance ] is generally considered such "autocrat" that tried to give an appearance of "republican democracy" to his style of government, for instance by allowing something that was generally regarded a sockpuppet opposition.</ref>. | |||

| * For full-fledged ] ultimately it generally does not make all that much difference whether the head of state is a monarch or a president, nor, in fact, whether these countries call themselves a monarchy or a republic. Other factors, for instance, religious matters (see next section) can often make a greater distinguishing mark when comparing the forms of government of actual countries. | |||

| Since the ] the term ''republic'' has described a system of government in which the source of authority for the government is a constitution<ref name="Munro"/> and the legitimacy of its officials derives from the consent of the people rather than ] or ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Paine |first1=Thomas |title=Common Sense |chapter=On the Origin and Design of Government in General, With Concise Remarks on the English Constitution |date=1776 |url=https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch4s4.html}}</ref> | |||

| For this reason, in ] the several definitions of "republic", which in such a context invariably indicate an "ideal" form of government, do not always exclude monarchy: the evolution of such definitions of "republic" in a context of ] is treated in ]. However, such theoretical approaches appear to have had no real influence on the everyday use (that is: apart from a scholar or "insider" context) of the terminology regarding republics and monarchies<ref>References where in everyday language countries with a king or emperor as head of state are termed ''republic'' have not been encountered.</ref>. | |||

| === Classical republics === | |||

| {{Main|Classical republic}} | |||

| ] in 45 BC]] | |||

| The modern type of republic itself is different from any type of state found in the classical world.<ref>Nippel, Wilfried. "Ancient and Modern Republicanism". ''The Invention of the Modern Republic'' ed. Biancamaria Fontana. Cambridge University Press, 1994 p. 6</ref><ref>Reno, Jeffrey. "republic". ''International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences'' p. 184</ref> Nevertheless, there are a number of states of the ] that are today still called republics. This includes ancient ] and the ]. While the structure and governance of these states was different from that of any modern republic, there is debate about the extent to which classical, medieval, and modern republics form a historical continuum. ] has argued that a distinct republican tradition stretches from the classical world to the present.<ref name="Ideas2099"/><ref name=Pocock>Pocock, J.G.A. ''The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition'' (1975; new ed. 2003)</ref> Other scholars disagree.<ref name="Ideas2099"/> Paul Rahe, for instance, argues that the classical republics had a form of government with few links to those in any modern country.<ref name=Rahe>Paul A. Rahe, ''Republics, Ancient and Modern'', three volumes, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1994.</ref> | |||

| The least that can be said is that ], the opposition to monarchy as such, did not always play a critical role in the creation and/or management of republics. For some republics, not choosing a monarch as head of state, could as well be a practical rather than an ideological consideration. Such "practical" considerations could be, for example, a situation where there was no monarchial candidate readily available<ref>For instance the ]: after the ] (]) the ] and later the ] were asked to rule the Netherlands. After these candidates had declined the office, the ] was only established in ].</ref>. However, for the states created during or shortly after ] the choice was always deliberate: ''republics'' created in that period inevitably had anti-monarchial characteristics. For the ] the opposition of some to the ] played a role, as did the overthrow of the French Monarchy in the creation of the ]. By the time of the creation of the ] in that country "anti-monarchist" tendencies were barely felt. The relations of that country to other countries made no distinctions whether these other countries were "monarchies" or not. | |||

| The political philosophy of the classical republics has influenced republican thought throughout the subsequent centuries. Philosophers and politicians advocating republics, such as ], ], ], and ], relied heavily on classical Greek and Roman sources which described various types of regimes. | |||

| ===Role of religion=== | |||

| <ref>This section draws from, among others, ''Geschiedenis der nieuwe tijden'' by J. Warichez and L. Brounts, 1946, Standaard Boekhandel (Antwerp/Brussels/Ghent/Louvain) and ''Cultuurgetijden'' (history books for secondary school in 6 volumes), Dr. J. A. Van Houtte et. al., several editions and reprints in 1960s through 1970s, Van In (Lier).</ref>Before several ] movements established themselves in Europe, changes in the religious landscape rarely had any relation to the form of government adopted by a country. For instance the transition from ] to ] in ] maybe had brought new rulers, but no change in the idea that monarchy was the obvious way to rule a country. Similarly, late ] republics, like ], emerged without questioning the religious standards set by the ] church.<ref>However, the Catholic Church itself briefly adopted a republican institution when it was offered by the Conciliarist movement as a solution to the Great Schism (rival papacies) during the late 14th century. The ecumenical Council of Constance in 1415 deposed three of the rival popes, elected a fourth, and extracted a promise from him that future such councils would continue to be called by future popes at regular intervals. (The Pope's concession to conciliarism did not last very long, but the English Parliament would not extract anything like it from its kings until the Puritan Revolution of the 1640s.)</ref> | |||

| ]'s '']'' discusses various forms of government. One form Aristotle named ''politeia'', which consisted of a mixture of the other forms, ] and ]. He argued that this was one of the ideal forms of government. ] expanded on many of these ideas, again focusing on the idea of ] and differentiated basic forms of government between "benign" ], ], and democracy, and the "malignant" ], oligarchy, and ]. The most important Roman work in this tradition is Cicero's '']''. | |||

| This would change, for instance, by the ] from the ] (]): this treaty, applicable in the ] and affecting the numerous (city-)states of ], ordained citizens to follow the religion of their ruler, whatever Christian religion that ruler chose - apart from ] (which remained forbidden by the same treaty). In France the king abolished the relative tolerance towards non-Catholic religions resulting from the ] (]), by the ] (]). In the ] and in ] the respective monarchs had each established their favourite brand of Christianity, so that by the time of ] in Europe (including the depending ]) there was not a single ]y that tolerated another religion than the official one of the state. | |||

| Over time, the classical republics became empires or were conquered by empires. Most of the Greek republics were annexed to the ] of ]. The Roman Republic expanded dramatically, conquering the other states of the Mediterranean that could be considered republics, such as ]. The Roman Republic itself then became the Roman Empire. | |||

| ====Republics reducing state religion impact==== | |||

| An important reason why people could choose their society to be organized as a ''republic'' is the prospect of staying free of ]: in this approach living under a monarch is seen as more easily inducing a uniform religion. All great monarchies had their state religion, in the case of ]s and some emperors this could even lead to a religion where the monarchs (or their dynasty) were endowed with a god-like status (see for example ]). On a different scale, kingdoms can be entangled in a specific flavour of religion: ] in ], ] in the ], ] in ]istic ] and many more examples. | |||

| === Other ancient republics === | |||

| In absence of a monarchy, there can be no monarch pushing towards a single religion. As this had been the general perception by the time of ], it is not so surprising that republics were seen by some Enlightenment thinkers as the preferable form of state organisation, if one wanted to avoid the downsides of living under a too influential state religion. ], an exception, envisioned a republic with a demanding state "civil religion": | |||

| The term ''republic'' is not commonly used to refer to pre-classical city-states, especially if outside Europe and the area which was under Graeco-Roman influence.<ref name="Ideas2099"/> However some early states outside Europe had governments that are sometimes today considered similar to republics. | |||

| * ]: the ], seeing that no single religion would do for all Americans, adopted the principle that the federal government would not support any established religion, as Massachusetts and Connecticut did.<ref>At first the states remained free to establish religions, but they had all disestablished their churches by 1836, and any residual option was eliminated in the 20th century by federal courts applying the First Amendment.</ref> | |||

| * Besides being anti-monarchial, the ], leading to the ], was at least as much anti-religious, and led to the confiscation, pillage and/or destruction of many ]s, ]s, ]es and other religious buildings and/or communities<ref>see also ]</ref>. Although the French revolutionaries tried to institute civil religions to replace "uncivic" Catholicism, nevertheless, up to the ], '']'' can be seen to have a much more profound meaning in republican ] than in neighbouring countries ruled as monarchies<ref>Example: ] - a similar law was tentatively debated in Belgium, but deemed incompatible with the less profoundly ''secularized'' Belgian state.</ref>. | |||

| In the ], a number of cities of the ] achieved collective rule. Republic city-states flourished in ] along the ]ine coast starting from the 11th century BC. In ancient Phoenicia, the concept of ] was very similar to a ]. Under ] (539–332 BC), Phoenician city-states such as ] abolished the king system and adopted "a system of the ] (judges), who remained in power for short mandates of 6 years".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Jidejian |first1=Nina |title=TYRE Through The Ages (3rd ed.) |date=2018 |publisher=Beirut: Librairie Orientale |isbn=9789953171050 |pages=57–99}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Medlej |first1=Youmna Jazzar |last2=Medlej |first2=Joumana |title=Tyre and its history |date=2010 |publisher=Beirut: Anis Commercial Printing Press s.a.l. |isbn=978-9953-0-1849-2 |pages=1–30}}</ref> ] has been cited as one of the earliest known examples of a republic, in which the people, rather than a monarch, are described as sovereign.<ref>{{cite book | last1=Bernal | first1=M. | last2=Moore | first2=D.C. | title=Black Athena Writes Back: Martin Bernal Responds to His Critics | publisher=Duke University Press | series=History / Classics | year=2001 | isbn=978-0-8223-2717-2 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BcZuf-piTMwC | pages=-}}</ref>{{Unreliable source?|date= February 2018}} The ] confederation of the era of the ]<ref> | |||

| Several states that called themselves republics have been fiercely anti-religious. This is particularly true for ] republics like the (former) ]s, ], ], and ]. | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last1 = Clarke | |||

| | first1 = Adam | |||

| | author-link1 = Adam Clarke | |||

| | chapter = PREFACE To The BOOK OF JUDGES | |||

| | title = The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments: The Text Printed from the Most Correct Copies of the Present Authorized Translation Including the Marginal Readings and Parallel Texts with a Commentary and Critical Notes Designed as a Help to a Better Understanding of the Sacred Writings | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=a-Q8AAAAYAAJ | |||

| | volume = 2 | |||

| | location = New-York | |||

| | publisher = N. Bangs and J. Emory | |||

| | date = 1825 | |||

| | page = 3 | |||

| | access-date = 10 June 2019 | |||

| | quote = The persons called Judges were the heads or chiefs of the Israelites who governed the Hebrew Republic from the days of Moses and Joshua, till the time of Saul. | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| before the ] has also been considered a type of republic.<ref name="Ideas2099"/><ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last1 = Everdell | |||

| | first1 = William Romeyn | |||

| | author-link1 = William Everdell | |||

| | year = 1983 | |||

| | chapter = Samuel and Solon: The Origins of the Republic in Tribalism | |||

| | title = The End of Kings: A History of Republics and Republicans | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/endofkingshistor00ever | |||

| | url-access = registration | |||

| | edition = 2 | |||

| | location = Chicago | |||

| | publisher = University of Chicago Press | |||

| | publication-date = 2000 | |||

| | page = | |||

| | isbn = 9780226224824 | |||

| | access-date = 10 June 2019 | |||

| | quote = Samuel has the distinction of being the first self-conscious republican in his society of whom we have nearly contemporary written record and of whose actual existence we can be reasonably sure. | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref><ref name="William R. Everdell 2000">{{Harvcoltxt|Everdell|2000}}</ref> The system of government of the ] in what is now ] has been described as "direct and participatory democracy".<ref>{{cite web |last1=Nwauwa |first1=Apollos O. |title=Concepts of Democracy and Democratization in Africa Revisited |url=http://upress.kent.edu/Nieman/Concepts_of_Democracy.htm |access-date=8 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120814023812/http://upress.kent.edu/Nieman/Concepts_of_Democracy.htm |archive-date=14 August 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ===Indian subcontinent=== | |||

| ====Republics highlighting state religion impact==== | |||

| {{main|Gaṇasaṅgha}} | |||

| Some countries or states prefer or preferred to organise themselves as a republic, ''precisely'' because it allows them to inscribe a more or less obligatory state religion in their constitution: ]s generally take this approach, but the same is also true (in varying degrees) for example in the ] state of ], in the ] republic that originated in the ] during the ]<ref>After the Duke of Anjou and the Earl of Leicester had declined the offer to become ruler of the Seven Provinces (see note above), ] had been the obvious choice for king: the volume ''Nieuwe tijden'' from the ''Cultuurgetijden'' series as mentioned in a previous note, elaborates on p. 63-65 (supported by a quote of the contemporary ]) that William of Orange was perceived as too lenient towards Catholicism to be acceptable as king for the Protestants.</ref>, and in the ] ], among others. In this case the advantage that is sought is that no ''broad-thinking'' monarch could push his citizens towards a less strict application of religious prescriptions (like for instance the ] system had done in the ]<ref>Although in Turkey the ensuing ''republic'' would become relatively tolerant towards other religions, the straight ] approach of the Millet system, that had allowed Christians and Jews to form state-in-state like communities, would remain unparallelled.</ref>) or change to another religion altogether (like the swapping of religions under the ]/]/]/] succession of ''monarchs'' in England). Such approach of an ideal republic based on a consolidated religious foundation played an important role for example in the ] of the ] in ], to be replaced by a ''republic'' with influential ]s (which is the term for religious leaders in that country), the most influential of which is called "]". | |||

| Early republican institutions come from the independent ]s{{Mdash}}] means 'tribe' and ] means 'assembly'{{Mdash}}which may have existed as early as the 6th century BC and persisted in some areas until the 4th century AD in India. The evidence for this is scattered, however, and no pure historical source exists for that period. ], a Greek historian who wrote two centuries after the time of ]'s invasion of India (now Pakistan and northwest India) mentions, without offering any detail, that independent and democratic states existed in India.<ref>Diodorus 2.39{{full citation|date=December 2024}}</ref> Modern scholars note the word ''democracy'' at the time of the 3rd century BC and later suffered from degradation and could mean any autonomous state, no matter how aristocratic in nature.<ref>Larsen, 1973, pp. 45–46{{full citation|date=December 2024}}</ref><ref>de Sainte, 2006, pp. 321–3{{full citation|date=December 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ] were the sixteen most powerful and vast kingdoms and republics of the era; there were also a number of smaller kingdoms stretching the length and breadth of ]. Among the mahajanapadas and smaller states, the ]s, ]s, ]s, and ]s followed republican government.]] | |||

| ===Concepts of democracy=== | |||

| Key characteristics of the {{transliteration|sa|gaṇa}} seem to include a ''gaṇa mukhya'' (chief), and a deliberative assembly. The assembly met regularly. It discussed all major state decisions. At least in some states, attendance was open to all free men. This body also had full financial, administrative, and judicial authority. Other officers, who rarely receive any mention, obeyed the decisions of the assembly. Elected by the {{transliteration|sa|gaṇa}}, the chief apparently always belonged to a family of the noble class of ''] ]''. The chief coordinated his activities with the assembly; in some states, he did so with a council of other nobles.<ref>Robinson, 1997, p. 22{{full citation|date=December 2024}}</ref> The ] had a primary governing body of 7,077 ''gaṇa mukhyas'', the heads of the most important families. On the other hand, the ]s, ]s, ]s, and ]s,{{Clarify|reason=There seems to be an apparent nonsequitur with the previous sentence regarding the Licchavis.|date=August 2023}} during the period around ], had the assembly open to all men, rich and poor.<ref>Robinson, 1997, p. 23{{full citation|date=December 2024}}</ref> Early republics or ],<ref name=Thapar>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-5irrXX0apQC&pg=PA147 |title=Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300|last=Thapar|first=Romila|author-link=Romila Thapar|year=2002|publisher=University of California|pages=146–150|access-date=28 October 2013|isbn=9780520242258}}</ref> such as Mallakas, centered in the city of ], and the ] (or Vṛjika) League, centered in the city of ], existed as early as the 6th century BC and persisted in some areas until the 4th century AD.<ref>Raychaudhuri Hemchandra (1972), ''Political History of Ancient India'', Calcutta: University of Calcutta, p.107</ref> The most famous clan amongst the ruling confederate clans of the Vajji ] were the Licchavis.<ref>{{cite book|title=Republics in ancient India|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zcoUAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA93|publisher=Brill Archive|pages=93–|id=GGKEY:HYY6LT5CFT0}}</ref> The ] included republican communities such as the community of Rajakumara. Villages had their own assemblies under their local chiefs called ''gramakas''. Their administrations were divided into executive, judicial, and military functions. | |||

| Republics are often associated with ], which seems natural if one acknowledges the meaning of the expression from which the word "republic" derives (see: ]). This association between "republic" and "democracy" is however far from a general understanding, even if acknowledging that there are ]<ref>See for example '']'' by ] - An original framer of the U.S. Constitution advocates a ''republic'' over a "democracy," or rather, an aristocratic republic over a democratic one. See ] for the ]s of the terms "democracy" and "republic" in the ] context when this article was written. Further clarification of this "democracy" vs "republic" idea in the US can be found in ]</ref>. This section tries to give an outline of which concepts of democracy are associated with which types of republics. | |||

| Scholars differ over how best to describe these governments, and the vague, sporadic quality of the evidence allows for wide disagreements. Some emphasize the central role of the assemblies and thus tout them as democracies; other scholars focus on the upper-class domination of the leadership and possible control of the assembly and see an ].<ref name="Bongard">Bongard-Levin, 1996, pp. 61–106</ref><ref name="Sharma">Sharma 1968, pp. 109–22</ref> Despite the assembly's obvious power, it has not yet been established whether the composition and participation were truly popular. This is reflected in the '']'', an ancient handbook for monarchs on how to rule efficiently. It contains a chapter on how to deal with the {{transliteration|sa|saṅgha}}''s'', which includes injunctions on manipulating the noble leaders, yet it does not mention how to influence the mass of the citizens, indicating that the {{transliteration|sa|gaṇasaṅgha}} are more of an aristocratic republic, than democracy.<ref>Trautmann T. R., ''Kautilya and the Arthashastra'', Leiden 1971</ref> | |||

| As a preliminary remark, the concept of "one equal vote per adult" did not become a generically-accepted principle in democracies until around the middle of the ]: before that in all democracies the ] depended on one's financial situation, ], ], or a combination of these and other factors. Many forms of government in previous times termed "democracy", including for instance the ], would, when transplanted to the early ] be classified as ] or a broad ], because of the rules on how votes were counted. | |||

| === Icelandic Commonwealth === | |||

| In a ''Western'' approach, warned by the possible dangers and impracticality of ] described since antiquity<ref>Some of the earliest warnings in this sense came from ]' pupils ] and ] around 400 BC: indeed their friend Socrates had been condemned to death in an entirely "democratic" system at ], hence they preferred the ''less democratic'' ]n system of government. See also ] - ].</ref>, there was a convergence towards ], for republics as well as monarchies, from ] on. A direct democracy instrument like ]s is still basically mistrusted in many of the countries that adopted representative democracy. Nonetheless, some republics like ] have a great deal of direct democracy in their state organisation, with usually several issues put before the people by referendum every year. | |||

| The Icelandic Commonwealth was established in 930 AD by refugees from ] who had fled the unification of that country under King ]. The Commonwealth consisted of a number of clans run by chieftains, and the ] was a combination of parliament and supreme court where disputes appealed from lower courts were settled, laws were decided, and decisions of national importance were taken. One such example was the ] in 1000, where the Althing decreed that all Icelanders must be baptized into Christianity, and forbade celebration of pagan rituals. Contrary to most states, the Icelandic Commonwealth had no official leader. | |||

| In the early 13th century, the ], the Commonwealth began to suffer from long conflicts between warring clans. This, combined with pressure from the Norwegian king ] for the Icelanders to rejoin the Norwegian "family", led the Icelandic chieftains to accept Haakon IV as king by the signing of the ''Gamli sáttmáli'' ("]") in 1262. This effectively brought the Commonwealth to an end. The Althing, however, is still Iceland's parliament, almost 800 years later.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/world/la-fg-iceland-free-speech-20110403,0,5332545.story | work=Los Angeles Times | first=Henry | last=Chu | title=Iceland seeks to become sanctuary for free speech | date=April 2, 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ] inspired state organisations that, at the height of the ], had barely more than a few external appearances in common with Western types of democracies. That is, not withstanding that on an ideological level Marxism and ] sought to empower ]s. A Communist republic like ] ] has many "popular committees" to allow participation from citizens on a very basic level, without much of a far-reaching political power resulting from that. This approach to democracy is sometimes termed ], but the term is contentious: the intended result is often something in between direct democracy and ], but connotations may vary<ref>For instance in ] the expression "basic democracy" is tied to the epoch of the military dictature.</ref>. | |||

| === Mercantile republics === | |||

| Some of the hardline ] lived on in the East, even after the ] fell. Sometimes the full name of such republics can be deceptive: having "people's" or "democratic" in the name of a country can, in some cases bear no relation with the concepts of democracy (neither "representative" nor "direct") that grew in the West. In fact, the phrase "People's Democratic Republic" was often synonymous with Marxist dictatorships during the Cold War. It also should be clear that many of these "Eastern" type of republics fall outside a definition of a republic that supposes control over who is in power by the people at large – unless it is accepted that the preference the people displays for their leader is in all cases authentic. | |||

| ], ''] offers the wealth of the sea to Venice'', 1748–1750. This painting is an allegory of the power of the ].]] | |||

| In Europe new republics appeared in the late Middle Ages when a number of small states embraced republican systems of government. These were generally small, but wealthy, trading states, like the Mediterranean ] and the ], in which the merchant class had risen to prominence. Knud Haakonssen has noted that, by the ], Europe was divided with those states controlled by a landed elite being monarchies and those controlled by a commercial elite being republics.<ref name=Haakonssen /> | |||

| ===Influence of republicanism=== | |||

| {{main|Republicanism}} | |||

| Like ''Anti-monarchism'' and ''religious differences'', ] played no equal role in the emergence of the many actual republics. Up to the republics that originated in the late middle ages, even if, from what we know about them, they also can be qualified "republics" in a modern understanding of the word, establishing the kind and amount of "republicanism" that led to their emergence is often limited to educated guesswork, based on sources that are generally recognised to be partly fictitious reconstruction<ref>For example, what is known about the origins of the Roman Republic is based on works by ], ], ], and others, all of which wrote at least some centuries after the emergence of that Republic — without exception all these authors have historical exactitude issues, including relative uncertainty over the year when the Roman Republic would have emerged.</ref>. | |||

| Italy was the most densely populated area of Europe, and also one with the weakest central government. Many of the towns thus gained considerable independence and adopted commune forms of government. Completely free of feudal control, the Italian city-states expanded, gaining control of the rural hinterland.{{sfn|Finer|1999|pp=950-955}} The two most powerful were the ] and its rival the ]. Each were large trading ports, and further expanded by using naval power to control large parts of the Mediterranean. It was in Italy that an ideology advocating for republics first developed. Writers such as ], ], ], and Leonardo Bruni saw the medieval city-states as heirs to the legacy of Greece and Rome. | |||

| Over time there were various mixtures of republicanism along with democratic theories of the rights of individuals, which (for instance in the ]) would find expression in the formation of liberal and socialist parties. What both ] and ] shared was the belief in the self-determination of peoples, and in individual human dignity. But they disagreed and continue to disagree on whether this required a republic, what is the ''exact'' use of the term "republic", and how economic life should be organized. This latter conflict is often described in terms of socialism (as an economic system) versus ] (the economic system promoted by liberals). The compromise between democracy and having an hereditary head of state is called ]. | |||

| Across Europe a wealthy merchant class developed in the important trading cities. Despite their wealth they had little power in the ] dominated by the rural land owners, and across Europe began to advocate for their own privileges and powers. The more centralized states, such as France and England, granted limited city charters. | |||

| There is however, for instance, no doubt that republicanism was a founding ideology of the ] and remains at the core of American political values. See ] | |||

| ]. Election of the first Head-Alderman'' in 1289, by Auguste Migette. ] was then a ] of the ].]] | |||

| ====In antiquity==== | |||

| In ], a number of ] were established as republics by the ].<ref> by Steve Muhlberger, Associate Professor of History, Nipissing University.</ref> In the ], a number of cities of the ] achieved collective rule. ] has been cited as one of the earliest known examples of a republic, in which the people, rather than a monarch, are described as sovereign.<ref>Martin Bernal, ''Black Athena Writes Back'' (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001), 359.</ref> | |||

| In the more loosely governed ], 51 of the largest towns became ]. While still under the dominion of the ] most power was held locally and many adopted republican forms of government.{{sfn|Finer|1999|pp=950-955}} The same rights to imperial immediacy were secured by the major trading cities of Switzerland. The towns and villages of alpine ] had, courtesy of geography, also been largely excluded from central control. Unlike Italy and Germany, much of the rural area was thus not controlled by feudal barons, but by independent farmers who also used communal forms of government. When the ] tried to reassert control over the region both rural farmers and town merchants joined the rebellion. The ] were victorious, and the ] was proclaimed, and Switzerland has retained a republican form of government to the present.<ref name="William R. Everdell 2000"/> | |||

| The important politico-philosophical writings of antiquity that survived the middle ages rarely had any influence on the emergence or strengthening of republics in the time they were written. When ] wrote the ] that later, in English speaking countries, became known as '']'' (a faulty translation from several points of view), Athenian democracy had already been established, and was not influenced by the treatise (if it had, it would have become ''less'' republican in a modern understanding). Plato's own experiments with his political principles in ] were a failure. ]'s '']'', far from being able to redirect the Roman state to reinforce its republican form of government, rather reads as a prelude to the ] that indeed emerged soon after Cicero's death. | |||

| Two Russian cities with a powerful merchant class—] and ]—also adopted republican forms of government in 12th and 13th centuries, respectively, which ended when the republics were conquered by ]/] at the end of 15th – beginning of 16th century.<ref>Ferdinand Joseph Maria Feldbrugge. ''Law in Medieval Russia'', IDC Publishers, 2009</ref> | |||

| ====In the renaissance==== | |||

| The emergence of the ], on the other hand, was marked by the adoption of many of these writings from Antiquity, which led to a more or less coherent view, retroactively termed "]". Differences however remained regarding which kind of "mix" in a ] type of ideal state would be the most inherently ''republican''. For those republics that emerged after the publication of the Renaissance philosophies regarding republics, like the ''']''', it is not always all that clear what role exactly was played by republicanism - among a host of other reasons - that led to the choice for "republic" as form of state ("other reasons" indicated elsewhere in this article: e.g., not finding a suitable candidate as monarch; anti-Catholicism; a middle class striving for political influence). | |||

| Following the collapse of the ] and establishment of the ] ], the ] merchant fraternities established a state centered on ] that is sometimes compared to the Italian mercantile republics. | |||

| ====Enlightenment republicanism==== | |||

| ] | |||

| The Enlightenment had brought a new generation of political thinkers, showing that, among other things, political ''philosophy'' was in the process of refocusing to political ''science''. This time the influence of the political ''thinkers'', like ], on the emergence of republics in America and France soon thereafter was unmistakable: ], ], etc were introduced with a certain degree of success in the new republics, along the lines of the major political thinkers of the day. | |||

| The dominant form of government for these early republics was control by a limited council of elite ]. In those areas that held elections, property qualifications or guild membership limited both who could vote and who could run. In many states no direct elections were held and council members were hereditary or appointed by the existing council. This left the great majority of the population without political power, and riots and revolts by the lower classes were common. The late Middle Ages saw more than 200 such risings in the towns of the Holy Roman Empire.{{sfn|Finer|1999|pp=955-956}} Similar revolts occurred in Italy, notably the ] in Florence. | |||

| In fact, the Enlightenment had set the standard for republics, as well as in many cases for monarchies, in the next century. The most important principles established by the close of the Enlightenment were ], the requirement that governments reflect the ] of the people that were subject to that law, that governments act in the ], in ways which are understandable to the public at large, and that there be some means of ]. | |||

| === Calvinist republics === | |||

| ====Proletarian republicanism==== | |||

| {{see also|European wars of religion}} | |||

| The next major branch in political thinking was pushed forward by ], who argued that classes, rather than nationalities, had interests. He argued that governments represented the interests of the dominant class, and that, eventually, the states of his era would be overthrown by those dominated by the rising class of the ]<ref>See for instance ], ].</ref>. | |||

| While the classical writers had been the primary ideological source for the republics of Italy, in Northern Europe, the ] would be used as justification for establishing new republics.{{sfn|Finer|1999|p=1020}} Most important was ] theology, which developed in the Swiss Confederacy, one of the largest and most powerful of the medieval republics. ] did not call for the abolition of monarchy, but he advanced the doctrine that the faithful had the duty to overthrow irreligious monarchs.<ref>"Republicanism". ''Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment'' p. 435</ref> Advocacy for republics appeared in the writings of the ] during the ].<ref>"Introduction". ''Republicanism: a Shared European Heritage''. By Martin van Gelderen and Quentin Skinner. Cambridge University Press, 2002 p. 1</ref> | |||

| Calvinism played an important role in the republican revolts in England and the Netherlands. Like the city-states of Italy and the Hanseatic League, both were important trading centres, with a large merchant class prospering from the trade with the New World. Large parts of the population of both areas also embraced Calvinism. During the ] (beginning in 1566), the ] emerged from rejection of ] rule. However, the country did not adopt the republican form of government immediately: in the formal declaration of independence (], 1581), the throne of ] was only declared vacant, and the Dutch magistrates asked the ], queen ] and prince ], one after another, to replace Philip. It took until 1588 before the ] (the ''Staten'', the representative assembly at the time) decided to vest the sovereignty of the country in themselves. | |||

| Here again the formation of republics along the line of the new political philosophies followed quickly after the emergence of the philosophies: from the early 20th century on ''communist'' type of republics were set up (communist ''monarchies'' were at least ''by name'' excluded), many of them standing for about a century - but in increasing tension with the states that were more direct heirs of the ideas of the Enlightenment. | |||

| In 1641 the ] began. Spearheaded by the ] and funded by the merchants of London, the revolt was a success, and ] was executed. In England ], ], and ] became some of the first writers to argue for rejecting monarchy and embracing a republican form of government. The ] was short-lived, and the monarchy was soon restored. The Dutch Republic continued in name until 1795, but by the mid-18th century the ] had become a ''de facto'' monarch. Calvinists were also some of the earliest settlers of the British and Dutch colonies of North America. | |||

| ====Islamic Republicanism==== | |||

| Following decolonialization in the second half of 20th century, the ''political'' dimension of the Islam<ref>That ] would have a more ''intrinsic'' political dimension than most other religions is argued, among others, by ] () in his book ''Brieven van een Pers'' (Meulenhoff - ISBN 90-290-7522-8)</ref> knew a new impulse, leading to several ]s. As far as "Enlightenment" and "communist" principles were sometimes up to a limited level incorporated in these republics, such principles were always subject to principles laid down in the ]. While, however, there is no apparent reason why ] and related concepts of Islamic political thought should emerge in a ''republican'' form of government, the strife for Islamic republics is generally not qualified as a form of "republicanism". | |||

| === Liberal republics === | |||

| ===Economical factors=== | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| The ancient concept of ], when applied to politics, had always implied that citizens on one level or another ''took part'' in governing the state: at least citizens were not indifferent to decisions taken by those in charge, and could engage in political debate. A line of thought followed often by historians<ref>For instance, ''Historia'' series of history books, chief editor prof. dr. M. Dierickx sj, published by De Nederlandse Boekhandel (Antwerpen/Amsterdam) in several editions from 1955 to the late 1970s studies these links between the presence of a wealthy middle class and the republics that emerged throughout history.</ref> is that citizens, under normal circumstances, would only become politically active if they had spare time above and beyond the daily effort for mere survival. In other words, enough of a wealthy middle class (that did not get its political influence from a monarch as nobility did) is often seen as one of the preconditions to establish a republican form of government. In this reasoning neither the cities of the ], nor late 19th century ], nor the Netherlands during their ] emerging in the form of a republic comes as a surprise, all of them at the top of their wealth through commerce and societies with an influential and rich middle class. | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 200 | |||

| | header = Liberal republics in early modern Europe | |||

| | image1 = Place de la République - Marianne.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = An allegory of the French Republic in Paris | |||

| | image2 = Flag of the Septinsular Republic.svg | |||

| | caption2 = ] flag from the early 1800s | |||

| | image3 = Upprop för republik 1848.jpg | |||

| | caption3 = A revolutionary Republican hand-written bill from the Stockholm riots during the ], reading: "Dethrone ] he is not fit to be a king: Long live the Republic! The Reform! down with the Royal house, long live {{lang|sv|]|italic=no}}! death to the king / Republic Republic the People. Brunkeberg this evening". The writer's identity is unknown. | |||

| }} | |||

| Along with these initial republican revolts, ] also saw a great increase in monarchical power. The era of ] replaced the limited and decentralized monarchies that had existed in most of the Middle Ages. It also saw a reaction against the total control of the monarch as a series of writers created the ideology known as ]. | |||

| Most of these ] thinkers were far more interested in ideas of ] than in republics. The ] had discredited republicanism, and most thinkers felt that republics ended in either ] or ].<ref>"Republicanism". ''Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment'' p. 431</ref> Thus philosophers like ] opposed absolutism while at the same time being strongly pro-monarchy. | |||

| Here also the different nature of republics inspired by Marxism becomes apparent: Karl Marx theorised that the government of a state should be based on the proletarians, that is on those whose political opinions never had been asked before, even less had been considered to really matter when designing a state organisation. There was a problem Marxist/Communist types of republics had to solve: most proletarians were lacking interest and/or experience in designing a state organisation, even if acquainted with '']'' or ]' writings. While the ''practical'' political involvement of proletarians on the level of an entire country hardly ever materialised, these communist republics were more often than not organised in a very top-down structure. | |||

| ] and ] praised republics, and looked on the city-states of Greece as a model. However, both also felt that a state like France, with 20 million people, would be impossible to govern as a republic. Rousseau admired the ] (1755–1769) and described his ideal political structure of small, self-governing communes. Montesquieu felt that a city-state should ideally be a republic, but maintained that a limited monarchy was better suited to a state with a larger territory. | |||

| ===Aggregations of states=== | |||

| When a country or state is organised on several levels (that is: several states that are "associated" in a "superstructure", or a country is split in sub-states with a relative form of independency) several models exist: | |||

| * Both over-arching structure and sub-states take the form of a republic (Example: ]) | |||

| * The over-arching structure is a republic, while the sub-states are not necessarily (Example: ]); | |||

| * The over-arching structure is not a republic, while the sub-states can be (Example: ], after the emergence of republics, like those of the ], within its realm). | |||

| The ] began as a rejection only of the authority of the ] over the colonies, not of the monarchy. The failure of the British monarch to protect the colonies from what they considered the infringement of ], the monarch's branding of those requesting redress as traitors, and his support for sending combat troops to demonstrate authority resulted in widespread perception of the British monarchy as ]. | |||

| ====Sub-national republics==== | |||

| In general being a republic also implies ] as for the state to be ruled by the people it cannot be controlled by a foreign power. There are important exceptions to this, for example, Republics in the ] were member states which had to meet three criteria to be named republics, | |||

| :1) Be on the periphery of the Soviet Union so as to be able to take advantage of their theoretical right to secede, | |||

| :2) Be economically strong enough to be self sufficient upon secession, And | |||

| :3) Be named after at least one million people of the ethnic group which should make up the majority population of said republic. | |||

| Republics were originally created by Stalin and continue to be created even today in Russia. Russia itself is not a republic but a federation. | |||

| It is sometimes argued that the former ] was also a supra-national republic, based on the claim that the member states were different ]. | |||

| With the ] the leaders of the revolt firmly rejected the monarchy and embraced republicanism. The leaders of the revolution were well-versed in the writings of the French liberal thinkers, and also in the history of the classical republics. ] had notably written a book on republics throughout history. In addition, the widely distributed and popularly read-aloud tract '']'', by ], succinctly and eloquently laid out the case for republican ideals and independence to the larger public. The ], which went into effect in 1789, created a relatively strong ] to replace the relatively weak ] under the first attempt at a national government with the ] ratified in 1781. The first ten amendments to the Constitution called the ], guaranteed certain ] fundamental to republican ideals that justified the Revolution. | |||

| States of the ] are required, like the federal government, to be republican in form, with final authority resting with the people. This was required because the states were intended to create and enforce most domestic laws, with the exception of areas delegated to the federal government and prohibited to the states. The founding fathers of the country intended most domestic laws to be handled by the states, although, over time, the federal government has gained more and more influence over domestic law. Requiring the states to be a republic in form was seen as protecting the citizens' rights and preventing a state from becoming a dictatorship or monarchy, and reflected unwillingness on the part of the original 13 states (all independent republics) to unite with other states that were not republics. Additionally, this requirement ensured that only other republics could join the union. | |||

| The ] was also not republican at its outset. Only after the ] removed most of the remaining sympathy for the king was a republic declared and ] sent to the guillotine. The stunning success of France in the ] saw republics spread by force of arms across much of Europe as a series of ] were set up across the continent. The rise of ] saw the end of the ] and her ]s, each replaced by "]". Throughout the Napoleonic period, the victors extinguished many of the oldest republics on the continent, including the ], the ], and the ]. They were eventually transformed into monarchies or absorbed into neighboring monarchies. | |||

| In the example of the ], the original 13 British ] became ] ]s after the ], each having a republican form of ]. These independent states initially formed a loose ] called the United States and then later formed the current United States by ratifying the current ], creating a ] of ] with the union or ] government also being a republic. States joining the union later were also required to be a republic. The United States could be argued to be a supra-national republic on the grounds that the original states were independent countries and was formed of several nations, most notably the original 13 colonies/states, the Republic of ], and the Kingdom of ], all of which would be considered "]" under a strict definition of the word. | |||

| Outside Europe, another group of republics was created as the ] allowed the states of Latin America to gain their independence. Liberal ideology had only a limited impact on these new republics. The main impetus was the local European-descended ] population in conflict with the ]—governors sent from overseas. The majority of the population in most of Latin America was of either African or ] descent, and the Creole elite had little interest in giving these groups power and broad-based ]. ], both the main instigator of the revolts and one of its most important theorists, was sympathetic to liberal ideals but felt that Latin America lacked the social cohesion for such a system to function and advocated ] as necessary. | |||

| ====Supra-national republics==== | |||

| Sovereign countries can decide to hand in a limited part of their sovereignty to a supra-national organisation. The most famous example of this, since the second half of the 20th century, is the emergence of the ], which models its organisation as a republic. That it would be a republic in a strict sense can be debated while the European Union is not a "country" in a strict sense. Being a republic is not part of the admission criteria for the member states<ref>see for example and in the text for </ref>. Although the largest political family of EU parlementaries has a Christian denomination, the ] would establish its form of government as ]<ref>After some fierce debate it was decided that the ] version of the Constitution proposal would not make any reference to the "Christian" roots (among other communal values) of Europe, see .</ref>. | |||

| In Mexico, this autocracy briefly took the form of a monarchy in the ]. Due to the ], the Portuguese court was relocated to Brazil in 1808. Brazil gained ] as a monarchy on September 7, 1822, and the ] lasted until 1889. In many other Latin American states various forms of autocratic republic existed until most were liberalized at the end of the 20th century.<ref>"Latin American Republicanism" New Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Ed. Maryanne Cline Horowitz. Vol. 5. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2005.</ref> | |||

| The ], like the United States, is also formed by independent states creating a union, except that the member states of the European Union are not required to be a republic. The European Union currently is not classified as a country, however it is starting to exhibit behaviors similar to a ]. Regardless, the European Union could still be classified as a supra-national republic even if it were to exhibit powers similar to a state because it is made of many ]. | |||

| {|style="float:center; clear:left; margin: 10px; border: 1px #CCCCCC solid; background:#F9F9F9" | |||

| |- | |||

| | align="center" |] | |||

| | align="center" |] | |||

| | align="center" |] | |||

| | align="center" |] | |||

| | align="center" |] | |||

| |- | |||

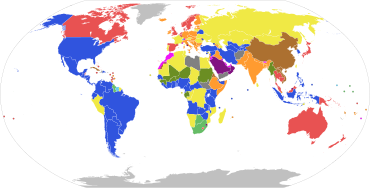

| |align=left|<small>]<ref>The ] and ] are counted amongst ]. Counted as republics are the ], the ], ], ] and ], the ], the ], the ] and the ]; however, member states of the German Confederation are also separately counted (35 monarchies).</ref><br /> | |||

| {{Legend|#FF0000|Monarchies (55)}} | |||

| {{Legend|#0000FF|Republics (9)}}</small> | |||

| |align=left|<small>]<ref>The ] and ] are counted amongst Europe.</ref><br /> | |||

| {{Legend|#FF0000|Monarchies (22)}} | |||

| {{Legend|#0000FF|Republics (4)}}</small> | |||

| |align=left|<small>]<ref>The Republic of Turkey is counted amongst Europe, the ] as a single republic, the ] as an independent monarchy (see also ]), Vatican City as an ], the ] as a nominal monarchy.</ref><br /> | |||

| {{Legend|#FF0000|Monarchies (20)}} | |||

| {{Legend|#0000FF|Republics (15)}}</small> | |||

| |align=left|<small>]<ref>The ] is counted amongst ], the ] as a single republic, the ] as an independent republic, ] as an ], the ] as a nominal monarchy.</ref><br /> | |||

| {{Legend|#FF0000|Monarchies (13)}} | |||

| {{Legend|#0000FF|Republics (21)}}</small> | |||

| |align=left|<small>]<ref>The ] is counted amongst ], the ] as a single republic, the ] (recognised by most other European states) as an independent republic, ] as an ]. ] is not shown on this map and is excluded from the count. The ] (recognised only by Turkey) and all other unrecognised states are excluded from the count.</ref><br /> | |||

| {{Legend|#FF0000|Monarchies (12)}} | |||

| {{Legend|#0000FF|Republics (35)}}</small> | |||

| |} | |||

| ]'']'' (1848), a symbolic representation of the ]. Oil on canvas, 73 x 60 cm., The Louvre, Paris]] | |||

| The ] was created in 1848 but abolished by ] who proclaimed himself Emperor in 1852. The ] was established in 1870 when a civil revolutionary committee refused to accept Napoleon III's surrender during the ]. Spain briefly became the ] in 1873–74, but the monarchy was soon restored. By the start of the 20th century France, Switzerland and San Marino remained the only republics in Europe. This changed when, after the 1908 ], the ] established the ]. | |||

| ] ] and the provisional President of the Republic ]]] | |||

| ==Examples of republics== | |||

| In East Asia, China had seen considerable ] during the 19th century, and a number of protest movements developed calling for constitutional monarchy. The most important leader of these efforts was ], whose ] combined American, European, and Chinese ideas. Under his leadership, the ] was proclaimed on January 1, 1912. | |||

| {{main|List of republics}} | |||

| In the early 21st century, most states that are not monarchies label themselves as republics either in their official names or their constitutions. There are a few exceptions: the ]n Arab ], the State of ], the ] and the ]n ]. Israel and Russia, and even Myanmar and Libya, would meet many definitions of the term ''republic'', however. | |||

| Republican ideas were spreading, especially in Asia. The United States began to have considerable influence in East Asia in the later part of the 19th century, with ] missionaries playing a central role. The liberal and republican writers of the West also exerted influence. These combined with native ] inspired political philosophy that had long argued that the populace had the right to reject unjust governments that had lost the ]. | |||

| Since the term ''republic'' is so vague by itself, many states felt it necessary to add additional qualifiers in order to clarify what kind of republics they claim to be. Here is a list of such qualifiers and variations on the term "republic": | |||

| * ''Without'' other qualifier than the term ''Republic'' - for example ]. | |||

| * ], ] or ] - a federal union of states with a republican form of government. Examples include ], ], ], ], the ], ] and ]. | |||

| * ] - Countries like ], ], ] are republics governed in accordance with Islamic law. (Note: ] is a distinct exception and is ''not'' included in this list; while the population is predominantly Muslim, the state is a staunchly secular republic.) | |||

| * ] - for example, ] its name reflecting its theoretically pan-Arab ] government. | |||

| * ] - Countries like ], ] are meant to be governed for and by the people, but generally without direct elections. Thus, they use the term ''People's Republic'', which was shared by many past ]s. | |||

| * ] - Tends to be used by countries who have a particular desire to emphasize their claim to be democratic; these are typically Communist states and/or ex-]. Examples include the ] (no longer in existence) and the ]. | |||

| * ] ('']'') - Both words (English and Polish) are derived from the Latin word ''res publica'' (literally "common affairs"). Used in Poland for the current ], and historical Nobles' Rzeczpospolita. | |||

| * ] - Sometimes used as a label to indicate implementation of, or transition from a ] to, a republican form of government. Used for the ] under an ] government, while still remaining part of the ]. | |||

| * ] has adopted since the adoption of the ] constitution the title of ] Republic of Venezuela. | |||

| * Other modifiers are rooted in tradition and history and usually have no real political meaning. ], for instance, is the "Most Serene Republic" while ] is the "Eastern Republic". | |||

| During this period, two short-lived republics were proclaimed in East Asia; the ] and the ]. | |||

| ==Republics in political theory== | |||

| {{main|Republics in political theory}} | |||

| In ] and political science, the term "republic" is generally applied to a ] where the government's ] depends solely on the consent, however nominal, of the people governed. This usage leads to two sets of problematic classification. The first are states which are oligarchical in nature, but are not nominally hereditary, such as many ]s, the second are states where all, or almost all, real political power is held by democratic institutions, but which have a monarch as nominal head of state, generally known as ]. The first case causes many outside the state to deny that the state should, in fact, be seen as a Republic. In many states of the second kind there are active "republican" movements that promote the ending of even the nominal monarchy, and the semantic problem is often resolved by calling the state a ]. | |||

| Republicanism expanded significantly in the aftermath of ] when several of the largest European empires collapsed: the ] (1917), ] (1918), ] (1918), and ] (1922) were all replaced by republics. New states gained independence during this turmoil, and many of these, such as ], ], ] and ], chose republican forms of government. Following Greece's defeat in the ], the monarchy was briefly replaced by the ] (1924–35). In 1931, the proclamation of the ] (1931–39) resulted in the ] leading to the establishment of a ]. | |||

| Generally, political scientists try to analyse underlying realities, not the ''names'' by which they go: whether a political leader calls himself "king" or "president", and the state he governs a "monarchy" or a "republic" is not the essential characteristic, whether he exerces power as an autocrat is. In this sense political analysts may say that the ] was, in many respects, the death knell for monarchy, and the establishment of republicanism, whether de facto and/or de jure, as being essential for a modern state. The ] and the ] were both abolished by the terms of the peace treaty after the war, the Russian Empire overthrown by the ]. Even within the victorious states, monarchs were gradually being stripped of their powers and prerogatives, and more and more the government was in the hands of elected bodies whose majority party headed the executive. Nonetheless post-WWI Germany, a ''de jure'' republic, would develop into a ''de facto'' autocracy by the mid ]: the new peace treaty, after the ], took more precaution in making the terms thus that also ''de facto'' (the Western part of) Germany would remain a republic. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The aftermath of ] left ] with a destroyed economy, a divided society, and anger against the monarchy for its endorsement of the ]. These frustrations contributed to a revival of the Italian republican movement.<ref>{{Citation|year=1970|title=Italia|encyclopedia=Dizionario enciclopedico italiano|volume=VI|page=456|publisher=]|language=it}}</ref> King ] was pressured to call the ] to decide whether Italy should remain a monarchy or become a republic.<ref>{{cite book|language=fr|first=Paul|last=Guichonnet|title=Histoire de l'Italie|publisher=Presses universitaires de France|year=1975|page=121}} {{No ISBN}}</ref> The supporters of the republic chose the effigy of the '']'', the ] of Italy, as their unitary symbol to be used in the electoral campaign and on the referendum ballot on the institutional form of the State, in contrast to the ], which represented the monarchy.<ref>{{cite book|last=Bazzano|first=Nicoletta |title=Donna Italia. L'allegoria della Penisola dall'antichità ai giorni nostri|url = https://www.academia.edu/15080772 |year=2011 |publisher=Angelo Colla Editore|language=it|isbn=978-88-96817-06-3|page=72}}</ref> On June 2, 1946 the republican side won 54.3% of the vote and Italy officially became a republic,<ref>{{cite book|language=it|first=Giorgio|last=Bocca|author-link=Giorgio Bocca|title=Storia della Repubblica italiana|publisher=Rizzoli|year=1981|pages=14–16}} {{No ISBN}}</ref> a day celebrated since as '']''. Italy has a written democratic ], resulting from the work of a ] formed by the representatives of all the ] forces that contributed to the defeat of Nazi and Fascist forces during the ].<ref>Smyth, Howard McGaw Italy: From Fascism to the Republic (1943–1946) ''The Western Political Quarterly'' vol. 1 no. 3 (pp. 205–222), September 1948.{{JSTOR|442274}}</ref> | |||

| ==Notes and references== | |||

| <references/> | |||

| === Decolonization === | |||

| ] | |||

| In the years following ], most of the remaining European colonies gained their independence, and most became republics. The two largest colonial powers were France and the United Kingdom. Republican France encouraged the establishment of republics in its former colonies. The United Kingdom attempted to follow the model it had for its earlier settler colonies of creating independent ]s still linked under the same monarch. While most of the settler colonies and the smaller states in the ] and the ] retained this system, it was rejected by the newly independent countries in ] and ], which revised their constitutions and became ]s instead. | |||

| Britain followed a different model in the Middle East; it installed local monarchies in several colonies and mandates including ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. In subsequent decades revolutions and ]s overthrew a number of monarchs and installed republics. Several monarchies remain, and the Middle East is the only part of the world where several large states are ruled by monarchs with almost complete political control.<ref>Anderson, Lisa. "Absolutism and the Resilience of Monarchy in the Middle East." ''Political Science Quarterly'', Vol. 106, No. 1 (Spring, 1991), pp. 1–15</ref> | |||

| === Socialist republics === | |||

| {{See also|People's Republic|Socialist state}} | |||

| In the wake of the First World War, the Russian monarchy fell during the ]. The ] was established in its place on the lines of a liberal republic, but this was overthrown by the ] who went on to establish the ] (USSR). This was the first republic established under ] ideology. Communism was wholly opposed to monarchy and became an important element of many republican movements during the 20th century. The Russian Revolution spread into ] and overthrew its theocratic monarchy in 1924. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the communists gradually gained control of ], ], ], ] and ], ensuring that the states were reestablished as socialist republics rather than monarchies. | |||

| Communism also intermingled with other ideologies. It was embraced by many national liberation movements during ]. In Vietnam, communist republicans pushed aside the ], and monarchies in neighbouring ] and ] were overthrown by communist movements in the 1970s. ] contributed to a series of revolts and coups that saw the monarchies of ], Iraq, Libya, and Yemen ousted. In Africa, Marxism–Leninism and ] led to the end of monarchy and the proclamation of republics in states such as ] and ]. | |||

| ==Constitution== | |||

| A republic does not necessarily have a ] but is often constitutional in the sense of ], meaning that it is constituted by a set of institutions which provide a ]. The term '''constitutional republic''' is a way to highlight an emphasis on the separation of powers in a given republic, as with ] or ] highlighting the absolute ] character of a ]. | |||

| == Head of state == | |||

| === Structure === | |||

| {{Systems of government}} | |||