| Revision as of 00:42, 19 April 2018 editCarbon Caryatid (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers40,718 edits →Solomon Islands: copy lead para from Malaita dolphin drive hunt← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:43, 1 October 2024 edit undoHorse Eye's Back (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users51,611 edits Add navbox | ||

| (70 intermediate revisions by 41 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Method of hunting dolphins}} | |||

| ⚫ | '''Dolphin drive hunting''', also called '''dolphin drive fishing''', is a method of ] ]s and occasionally other small ]s by driving them together with boats |

||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2021}} | |||

| ⚫ | '''Dolphin drive hunting''', also called '''dolphin drive fishing''', is a method of ] ]s and occasionally other small ]s by driving them together with boats, usually into a bay or onto a beach. Their escape is prevented by closing off the route to the open sea or ocean with boats and nets. Dolphins are hunted this way in several places around the world including the ], the ], ], and ], which is the most well-known practitioner of the method. In large numbers dolphins are mostly hunted for their ]; some end up in ]s. | ||

| Despite the controversial nature of the hunt resulting in international criticism, and the possible health risk that the often polluted meat causes, thousands of dolphins are caught in drive hunts each year. | Despite the controversial nature of the hunt resulting in international criticism, and the possible health risk that the often polluted meat causes, tens of thousands of dolphins are caught in drive hunts each year.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://awionline.org/press-releases/report-100000-dolphins-small-whales-and-porpoises-slaughtered-globally-each-year|title=Report: 100,000+ Dolphins, Small Whales and Porpoises Slaughtered Globally Each Year|date=7 August 2018 }}</ref> | ||

| ] caught in a drive hunt in ] on the ] being taken away with a forklift]] | ] caught in a drive hunt in ] on the ] being taken away with a forklift]] | ||

| Line 8: | Line 10: | ||

| === Faroe Islands === | === Faroe Islands === | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Whaling in the Faroe Islands}} | ||

| ] |

]s on the beach in the village ] on the southernmost Faroese island ], August 2002]] | ||

| On the Faroe Islands mainly ] are killed by drive hunts for their meat and blubber. Other species are also killed on rare occasion such as the Northern bottlenose whale and ]. The Northern bottlenose whale is mainly killed when it accidentally swims too close to the beach and cannot return to the water. When the locals find them stranded or nearly stranded on the beach, they kill them and share the meat to all the villagers.<ref name=autogenerated3>{{cite web|url=http://aktuelt.fo/grein/doglingar_deydir_i_sandvk|title=Tíðindi - Føroyski portalurin - portal.fo|work=portal.fo|accessdate=20 August 2015}}</ref> | |||

| Whaling in the ] takes the form of beaching and slaughtering ]s. It has been practiced since about the time of the first ] settlements on these ] islands, and thus can be considered ]. It is mentioned in the ], a Faroese law from 1298, a supplement to the ] ] law.<ref name="Disappearing Foods">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XR9YIaG0kIcC&q=sheep+letter+1298+grind&pg=PA86|title=Disappearing Foods: Studies in Foods and Dishes at Risk|last=Walker|first=Harlan|isbn=9780907325628|year=1995|publisher=Oxford Symposium }}</ref> | |||

| The stranding of the Northern bottlenose whale mainly happens in two villages in the northern part of Suðuroy: ] and ]. It is believed that it happens because of a navigation problem of the whale, because there are isthmuses on these places, where the distance between the east and west coasts are short, around one kilometer or so. And for some reason it seems like the bottlenose whale want to take a short cut through what it thinks is a sound, and too late it discovers, that is on shallow ground and is unable to turn around again. It happened on 30 August 2012, when two Northern bottlenose whales swam ashore to the gorge Sigmundsgjógv in ]. Two men who were working on the harbour noticed these whales, and some time later they had either died by themselves or were killed by the locals and then cut up for food for the people of Sandvík and Hvalba (Hvalba municipality).<ref name=autogenerated3 /> | |||

| It is closely regulated by the Faroese authorities,<ref name="logir.fo"></ref> with around 800 long-finned pilot whales<ref name="hagstova.fo"></ref> and some ]s slaughtered annually;<ref>{{cite web|title=Grinds de 2000 à 2013 |url=http://www.whaling.fo/Default.aspx?ID=7125 |website=www.whaling.fo/ Catch figures |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141106012321/http://whaling.fo/Default.aspx?ID=7125 |archive-date=6 November 2014 }}</ref> mainly during the summer. The hunts, called ''grindadráp'' in ], are non-commercial and are organized on a community level. Anyone who has a special training certificate on slaughtering a pilot whale with the spinal-cord lance can participate.<ref name="Certificate2015">{{cite web|url=http://www.in.fo/news-detail/news/nu-eru-1380-foeroyingar-klarir-at-fara-i-grind/|title=Nú eru 1380 føroyingar klárir at fara í grind|last=Bertholdsen|first=Áki|date=5 March 2015|publisher=Sosialurin - in.fo|language=fo|access-date=2 August 2015|archive-date=5 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191205140146/https://www.in.fo/news-detail/news/nu-eru-1380-foeroyingar-klarir-at-fara-i-grind/|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="The Grind Law">{{cite web|url=http://www.logir.fo/Logtingslog/56-fra-19-05-2015-um-grind-og-annan-smahval|title=Løgtingslóg um grind og annan smáhval, sum seinast broytt við løgtingslóg nr. 93 frá 22. juni 2015|date=19 May 2015|publisher=Logir.fo|language=fo|access-date=2 August 2015}}</ref> The police and Grindaformenn are allowed to remove people from the grind area.<ref name="logir.fo"/> The hunters first surround the pilot whales with a wide semicircle of boats. The boats then drive the pilot whales into a ] or to the bottom of a ]. Not all bays are certified, and the slaughter will only take place on a certified beach. | |||

| The hunt of the pilot whale is known by the locals as the ]. There are no fixed hunting seasons. As soon as a pod close enough to land is spotted, the locals set out to begin the hunt, after approval from the sysselman. The animals are driven into a bay which is approved for whaling by the Faroese government, and then they try to make the whales to beach themselves. The only way out is being blocked off by some of the boats, which stay there until men who have been waiting on shore have slaughtered all the whales.<ref name=autogenerated4>Jústines Olsen (1999), , article retrieved on June 21, 2008. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080614224523/http://www.whaling.fo/nammco99whalingandanimal.htm |date=June 14, 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| Many Faroese consider the whale meat an important part of their food culture and history. Animal rights groups criticize the slaughter as being cruel and unnecessary.<ref></ref><ref name="The Knowledge 2014">{{cite web|url=http://theknowledgeplymouth.co.uk/whaling-in-the-faroe-islands-a-cruel-and-unnecessary-ritual-or-sustainable-food-practice/|title=Whaling in the Faroe Islands: a cruel and unnecessary ritual or sustainable food practice?|last=Barrat|first=Harry|date=3 February 2014|publisher=The Knowledge|access-date=2 August 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151222112614/http://theknowledgeplymouth.co.uk/whaling-in-the-faroe-islands-a-cruel-and-unnecessary-ritual-or-sustainable-food-practice/|archive-date=22 December 2015|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="Advocacy for Animals 2010">{{cite web|url=http://advocacy.britannica.com/blog/advocacy/2010/04/the-faroe-islands-whale-hunt/|title=The Faroe Islands Whale Hunt|last=Duignan|first=Brian|date=26 April 2010|publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica - Advocacy for Animals|access-date=2 August 2015}}</ref> In November 2008, Høgni Debes Joensen, chief medical officer of the Faroe Islands and Pál Weihe, scientist, have recommended in a letter to the Faroese government that pilot whales should no longer be considered fit for human consumption because of the high level of ], ] and ] derivatives.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.landslaeknin.fo/upload/tilmaeli_um_grind.pdf |title=landslaeknin.fo |access-date=19 April 2018 |archive-date=10 August 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140810025738/http://www.landslaeknin.fo/upload/tilmaeli_um_grind.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name="toxic-whale">{{cite news |first=Debora |last=MacKenzie |date=28 November 2008 |title=Faroe islanders told to stop eating 'toxic' whales. |url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn16159-faroe-islanders-told-to-stop-eating-toxic-whales.html |work=] |access-date=21 July 2009}}</ref> However, the Faroese government did not forbid whaling. On 1 July 2011 the Faroese Food and Veterinary Authority announced their recommendation regarding the safety of eating meat and blubber from the pilot whale, which was not as strict as the one of the chief medical officers. The new recommendation says only one dinner with whale meat and blubber per month, with a special recommendation for younger women, girls, pregnant women and breastfeeding women.<ref name="hfs.fo"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140810183632/http://www.hfs.fo/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/HFS/WWW_HFS_FO/UMSITING/KUNNANDITILFAR/KUNNANDITILFARFRABODANIR/KUNNTILFFRAMATVORUR/GRIND_0.PDF |date=10 August 2014 }}</ref> From 2002 to 2009 the PCB concentration in whale meat has fallen by 75%, DDT values in the same time period have fallen by 70% and mercury levels have also fallen.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://us.fo/Default.aspx?ID=10642|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150206224651/http://us.fo/Default.aspx?ID=10642|archive-date=6 February 2015|title=Kyksilvur í grind}}</ref> | |||

| When on the beach, most of them get stuck. Those that have remained too far in the water are dragged onto the beach by putting a hook in their ]. When on land, they are killed by cutting down to the major arteries and ] at the neck. The time it takes for a whale to die varies from a few seconds Up to half a minute, depending on the cut.<ref name=autogenerated4 /> If the locals fail to beach the animals altogether, they are let free again. | |||

| The pilot whale stock in the eastern and central North Atlantic is estimated to number 778,000. | |||

| About a thousand pilot whales are killed this way each year on the Faroe Islands together with usually a few dozen up to a few hundred animals belonging to other small cetaceans species, but numbers vary greatly per year.<ref>Faroese museum of natural history, zoological department (year unknown), , data retrieved on June 21, 2008.</ref> The amount of Pilot Whales killed each year is not believed to be a threat to the sustainability of the population,<ref>Jóhann Sigurjónsson (year unknown), , article retrieved on June 21, 2008.</ref> but the brutal appearance of the hunt has resulted in international criticism especially from animal welfare organisations. | |||

| Due to pollution, consumption of the meat and blubber is considered unhealthy by some. Especially children and pregnant women are at risk, with ] exposure to ] and ]s primarily from the consumption of pilot whale meat has resulted in ] deficits amongst children.<ref>{{Cite web|author= ] / ] DTIE Chemicals Branch |year= 2008 |title= Guidance for identifying populations at risk from mercury exposure|page= 36 |url= http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/chem/mercuryexposure.pdf |quote= The Faroe Islands population was exposed to methylmercury largely from contaminated pilot whale meat, which contained very high levels of about 2 mg methylmercury/kg. However, the Faroe Islands populations also eat significant amounts of fish. The study of about 900 Faroese children showed that prenatal exposure to methylmercury resulted in neuropsychological deficits at 7 years of age. |accessdate= 29 August 2013}}</ref><ref>Nick Haslam for BBC news (2003), , article retrieved on June 21, 2008.</ref> | |||

| In November 2008, the ] reported in an article that research done in the Faroe Islands lead to the recommendation by Faroese government that the consumption of Pilot Whale meat in the Faroes should stop as it had been proved to be too toxic.<ref>Debora MacKenzie for the New Scientist, , article retrieved November 28, 2008.</ref> However, the Faroese government did not forbid people to eat Pilot Whale meat due to the contamination, but the advice from the Joensen and Weihe had an effect, it has resulted in reduced consumption, according to a senior Faroese health official.<ref>WDCS (2009), , article retrieved July 10, 2009.</ref> | |||

| In June 2011 the Faroese Food and Veterinary Authorities sent out an official recommendation regarding the consumption of meat and blubber from the pilot whale.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140810183632/http://www.hfs.fo/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/HFS/WWW_HFS_FO/UMSITING/KUNNANDITILFAR/KUNNANDITILFARFRABODANIR/KUNNTILFFRAMATVORUR/GRIND_0.PDF |date=2014-08-10 }}</ref> They recommend that because of the pollution of the whale: | |||

| * Adults should only eat one dinner with pilot whale meat and blubber per month. | |||

| * Special advice for women and girls: | |||

| ** Girls and women should not eat blubber at all until they have finished given birth to children. | |||

| ** Women who plan to get pregnant within 3 months, pregnant women and women who breastfeed should probably not eat whale meat at all. | |||

| * The kidneys and liver of the pilot whales should not be eaten.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140810183632/http://www.hfs.fo/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/HFS/WWW_HFS_FO/UMSITING/KUNNANDITILFAR/KUNNANDITILFARFRABODANIR/KUNNTILFFRAMATVORUR/GRIND_0.PDF |date=2014-08-10 }}</ref> | |||

| === Iceland=== | === Iceland=== | ||

| {{Main|Whaling in Iceland}} | {{Main|Whaling in Iceland}} | ||

| In mid-1950s, fishermen in Iceland requested assistance from the government to remove |

In mid-1950s, fishermen in Iceland requested assistance from the government to remove ]s from Icelandic waters as they damaged fishing equipment. With fisheries accounting for 20% of Iceland's employment at the time, the perceived economic impact was significant. The Icelandic government asked the United States for assistance. As a ] ally with an air base in Iceland, the ] deployed Patrol Squadrons VP-18 and VP-7 to achieve this task. According to the US Navy, hundreds of animals were killed with ]s, ]s and ]s.<ref>United States Navy Archive / Naval Aviation News (1956) {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140309231158/http://www.history.navy.mil/nan/backissues/1950s/1956/dec56.pdf |date=9 March 2014 }}</ref> | ||

| In the late 1970s, after the ] and the ban on hunting |

In the late 1970s, after the ] and the ban on hunting killer whales in ] in 1976 as discussed later in this article, the hunting of killer whales in Iceland resumed, this time aiming to capture live animals for the entertainment industry. The first two killer whales captured went to ] in the ]. One of these animals was soon after transferred to ]. These captures continued until 1989 with the additional animals going to SeaWorld, ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>PBS - Frontline - , article retrieved 9 March 2014.</ref> | ||

| Although commercial whaling does still take place in Icelandic waters today, dolphins are no longer hunted and ] is popular amongst tourists. | Although commercial whaling does still take place in Icelandic waters today, dolphins are no longer hunted and ] is popular amongst tourists. | ||

| === Japan === | === Japan === | ||

| {{Main|Taiji dolphin drive hunt}} | {{Main|Taiji dolphin drive hunt|History of dolphin fishing and utilization in Japan}} | ||

| {{See also|Fishing industry in Japan|Whaling in Japan}} | {{See also|Fishing industry in Japan|Whaling in Japan}} | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| The |

The Taiji dolphin drive hunt captures small cetaceans for ] and for sale to ]s. ] has a long connection to ]. The 2009 documentary film '']'' drew international attention to the hunt. Taiji is the only town in Japan where drive hunting still takes place on a large scale. Concern is majority through the methodology of the hunt, as actions are viewed as inhumane. An article by '']'' refers to The ]' decision to no longer support the Taiji hunt. In 2015, it was announced that there would be a ban in the buying and selling of dolphins through the means of this hunt.{{Citation needed|date=March 2021}} | ||

| === Kiribati === | === Kiribati === | ||

| Similar drive hunting existed in ] at least until the mid |

Similar drive hunting existed in ] at least until the mid-20th century.<ref>British diplomat Arthur Grimble's memoir, ''A Pattern of Islands'' (1952)</ref> | ||

| === Peru === | === Peru === | ||

| ] being skinned on a boat in Peru |

] being skinned on a boat in Peru]] | ||

| ⚫ | Though it is forbidden under Peruvian law to hunt dolphins or eat their meat (sold as ''chancho marino'', or ''sea pork'' in English), a large number of dolphins are still killed illegally by fishermen each year.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Hall |first=Kevin G. |title=Dolphin meat widely available in Peruvian stores: Despite protected status, 'sea pork' is popular fare |newspaper=The Seattle Times |year=2003 |url=http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Dolphin+meat+widely+available+in+Peruvian+stores+Despite+protected...-a0102897976 |access-date=7 December 2010 }}{{dead link|date=June 2016|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> To catch the dolphins, they are driven together with boats and encircled with nets, then ]ed, dragged on to the boat, and clubbed to death if still alive. Various species are hunted, such as the ] and ].<ref>Stefan Austermühle (2003), , article retrieved on 21 June 2008. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070928061242/http://www.awionline.org/pubs/Quarterly/sp03/0603p9.htm |date=28 September 2007 }}</ref> | ||

| Though it is forbidden under Peruvian law to hunt dolphins or eat their meat (sold as ''chancho marino'', or ''sea pork'' in English), | |||

| ⚫ | a large number of dolphins are still killed illegally by fishermen each year.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Hall |first=Kevin G. |title=Dolphin meat widely available in Peruvian stores: Despite protected status, 'sea pork' is popular fare |newspaper=The Seattle Times |

||

| According to estimates from local animal welfare organisation Mundo Azul released in October 2013, between 1,000 and 2,000 dolphins are killed annually for consumption, with a further 5,000 to 15,000 being killed for use as shark bait. Sharks are captured both for their meat and for use of their fins in ].<ref>Hispanic Business (2013), {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131030011252/http://www.hispanicbusiness.com/2013/10/25/peruvian_officials_to_take_action_to.htm |date=October |

According to estimates from local animal welfare organisation Mundo Azul released in October 2013, between 1,000 and 2,000 dolphins are killed annually for consumption, with a further 5,000 to 15,000 being killed for use as shark bait. Sharks are captured both for their meat and for use of their fins in ].<ref>Hispanic Business (2013), {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131030011252/http://www.hispanicbusiness.com/2013/10/25/peruvian_officials_to_take_action_to.htm |date=30 October 2013 }}, article retrieved 30 October 2013.</ref><ref>All Voices (2013), {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131102065833/http://www.allvoices.com/contributed-news/15814517-fishermen-butchering-dolphins-for-shark-bait-sparks-global-outrage |date=2013-11-02 }}, article retrieved 30 October 2013.</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Rodriguez|first1=Cindy|last2=Romo|first2=Rafael|title=Dolphins killed for shark bait in Peru|url=http://www.cnn.com/2013/10/22/world/americas/dolphins-killed-peru/|access-date=8 October 2016|work=CNN|date=23 October 2013}}</ref> | ||

| === Solomon Islands === | === Solomon Islands === | ||

| {{Main|Malaita dolphin drive hunt}} | {{Main|Malaita dolphin drive hunt}} | ||

| <!-- FAIR USE of Dolphinhuntsolomon.jpg: see image description page at http://en.wikipedia.org/Image:Dolphinhuntsolomon.jpg for rationale --> | <!-- FAIR USE of Dolphinhuntsolomon.jpg: see image description page at http://en.wikipedia.org/Image:Dolphinhuntsolomon.jpg for rationale --> | ||

| ] |

]]] | ||

| Dolphin are hunted in Malaita, in the ] in the ], mainly for ] and teeth, and also sometimes for live capture for ]s. The hunt on ] is smaller in scale than Tajai. |

Dolphin are hunted in Malaita, in the ] in the ], mainly for ] and teeth, and also sometimes for live capture for ]s. The hunt on ] is smaller in scale than Tajai.<ref name="TAK1">{{cite book|last1=Takekawa|first1=Daisuke|title=Hunting method and the ecological knowledge of dolphins among the Fanalei villagers of Malaita, Solomon Islands|url=http://westernsolomons.uib.no/docs/Hviding,%20Edvard/Johannes%20&%20Hviding%202000%20SPC%20Traditional%2012.pdf|year=2000|publisher=SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin No. 12|page=4|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304093949/http://westernsolomons.uib.no/docs/Hviding%2C%20Edvard/Johannes%20%26%20Hviding%202000%20SPC%20Traditional%2012.pdf|archive-date=4 March 2016|url-status=dead}}</ref> After capture, the meat is shared equally between households. Dolphin teeth are also used in jewelry and as currency on the island.<ref>Takekawa Daisuke & Ethel Falu (1995, 2006), {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070928064137/http://www.apa-apa.net/kirio/kirio-e.htm |date=2007-09-28 }}, article retrieved on 21 June 2008.</ref> | ||

| === Taiwan === | === Taiwan === | ||

| On the ] in ], drive fishing of |

On the ] in ], drive fishing of bottlenose dolphins was practiced until 1990, when the practice was outlawed by the government. Mainly ]s but also common bottlenose dolphins were captured in these hunts.<ref>R. R. Reeves, W. F. Perrin, B. L. Taylor, C. S. Baker and S. L. Mesnick (2004), ''Report of the Workshop on Shortcomings of Cetacean Taxonomy in Relation to Needs of Conservation and Management'', page 27, section ''Management of cetacean exploitation''. Article retrieved on 21 October 2006.</ref> | ||

| === United States === | === United States === | ||

| {{See also|Whaling in the United States}} | |||

| ====New England==== | |||

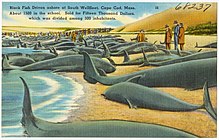

| ] in 1885, and sold for a considerable sum for their oil]] | |||

| From 1644 at ], on ], the colonists established an organised whale fishery, chasing ]s ("blackfish") onto the shelving beaches for slaughter. They also processed ]s they found on shore. They observed the Native Americans hunting techniques, improved on their weapons and boats, and then went out to ocean hunting.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Federal Writers' Project|title=Whaling Masters|publisher=Works Progress Administration}}</ref>{{update inline|date=July 2019}}<!-- no longer practiced; when did it stop? --> | |||

| ==== Hawaii ==== | ==== Hawaii ==== | ||

| In ancient ], fishermen occasionally hunted dolphins for their meat by driving them onto the beach and killing them. In their ancient legal system, dolphin meat was considered to be '']'' (forbidden) for women together with several other kinds of food. |

In ancient ], fishermen occasionally hunted dolphins for their meat by driving them onto the beach and killing them. In their ancient legal system, dolphin meat was considered to be '']'' (forbidden) for women together with several other kinds of food. As of 2008, dolphin drive hunting no longer takes place in Hawaii.<ref>Earthtrust (year unknown), , article retrieved on 21 June 2008.</ref> | ||

| ==== Texas ==== | ==== Texas ==== | ||

| Line 77: | Line 67: | ||

| ====Washington==== | ====Washington==== | ||

| Drive hunting methods were used to capture |

Drive hunting methods were used to capture orcas in ] in the 1960s and 1970s. These hunts were led by aquarium owner and entrepreneur ] and his partner Don Goldsberry. After Griffin purchased an orca that was caught by accident by fishermen in ], ], in 1965, Griffin and Goldsberry used drive hunting techniques in the Puget Sound area to capture orcas for the entertainment industry.<ref>] - , article retrieved 19 December 2013.</ref> They implemented their new methods for orca capture in their ] in 1967.<ref name=Colby103>{{cite book |last=Colby |first=Jason M. |title=Orca: how we came to know and love the ocean's greatest predator |year=2018 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=Oxford |isbn=9780190673116 |page=103 }}</ref> Others followed and despite the ] the practice continued until 1976 when the state of Washington ordered the release of a number of orcas that were being held in ] and subsequently banned the practice.<ref>Timothy Egan, The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest, page 141.</ref> | ||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| Line 84: | Line 74: | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| {{ |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| Line 93: | Line 83: | ||

| * : Up to date reports and info | * : Up to date reports and info | ||

| * (German only) | * (German only) | ||

| * | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110906063821/http://www.takepart.com/thecove/ |date=6 September 2011 }} | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| Line 107: | Line 97: | ||

| {{Whaling}} | {{Whaling}} | ||

| {{Hunting topics}} | |||

| {{good article}} | {{good article}} | ||

| Line 113: | Line 104: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 22:43, 1 October 2024

Method of hunting dolphinsDolphin drive hunting, also called dolphin drive fishing, is a method of hunting dolphins and occasionally other small cetaceans by driving them together with boats, usually into a bay or onto a beach. Their escape is prevented by closing off the route to the open sea or ocean with boats and nets. Dolphins are hunted this way in several places around the world including the Solomon Islands, the Faroe Islands, Peru, and Japan, which is the most well-known practitioner of the method. In large numbers dolphins are mostly hunted for their meat; some end up in dolphinariums.

Despite the controversial nature of the hunt resulting in international criticism, and the possible health risk that the often polluted meat causes, tens of thousands of dolphins are caught in drive hunts each year.

By country

Faroe Islands

Main article: Whaling in the Faroe Islands

Whaling in the Faroe Islands takes the form of beaching and slaughtering long-finned pilot whales. It has been practiced since about the time of the first Norse settlements on these North Atlantic islands, and thus can be considered aboriginal whaling. It is mentioned in the Sheep Letter, a Faroese law from 1298, a supplement to the Norwegian Gulating law.

It is closely regulated by the Faroese authorities, with around 800 long-finned pilot whales and some Atlantic white-sided dolphins slaughtered annually; mainly during the summer. The hunts, called grindadráp in Faroese, are non-commercial and are organized on a community level. Anyone who has a special training certificate on slaughtering a pilot whale with the spinal-cord lance can participate. The police and Grindaformenn are allowed to remove people from the grind area. The hunters first surround the pilot whales with a wide semicircle of boats. The boats then drive the pilot whales into a bay or to the bottom of a fjord. Not all bays are certified, and the slaughter will only take place on a certified beach.

Many Faroese consider the whale meat an important part of their food culture and history. Animal rights groups criticize the slaughter as being cruel and unnecessary. In November 2008, Høgni Debes Joensen, chief medical officer of the Faroe Islands and Pál Weihe, scientist, have recommended in a letter to the Faroese government that pilot whales should no longer be considered fit for human consumption because of the high level of mercury, PCB and DDT derivatives. However, the Faroese government did not forbid whaling. On 1 July 2011 the Faroese Food and Veterinary Authority announced their recommendation regarding the safety of eating meat and blubber from the pilot whale, which was not as strict as the one of the chief medical officers. The new recommendation says only one dinner with whale meat and blubber per month, with a special recommendation for younger women, girls, pregnant women and breastfeeding women. From 2002 to 2009 the PCB concentration in whale meat has fallen by 75%, DDT values in the same time period have fallen by 70% and mercury levels have also fallen.

Iceland

Main article: Whaling in IcelandIn mid-1950s, fishermen in Iceland requested assistance from the government to remove killer whales from Icelandic waters as they damaged fishing equipment. With fisheries accounting for 20% of Iceland's employment at the time, the perceived economic impact was significant. The Icelandic government asked the United States for assistance. As a NATO ally with an air base in Iceland, the US Navy deployed Patrol Squadrons VP-18 and VP-7 to achieve this task. According to the US Navy, hundreds of animals were killed with machineguns, rockets and depth charges.

In the late 1970s, after the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 and the ban on hunting killer whales in Washington in 1976 as discussed later in this article, the hunting of killer whales in Iceland resumed, this time aiming to capture live animals for the entertainment industry. The first two killer whales captured went to Dolfinarium Harderwijk in the Netherlands. One of these animals was soon after transferred to SeaWorld. These captures continued until 1989 with the additional animals going to SeaWorld, Marineland Antibes, Marineland of Canada, Kamogawa Sea World, Ocean Park Hong Kong, and Conny-Land.

Although commercial whaling does still take place in Icelandic waters today, dolphins are no longer hunted and whale watching is popular amongst tourists.

Japan

Main articles: Taiji dolphin drive hunt and History of dolphin fishing and utilization in Japan See also: Fishing industry in Japan and Whaling in Japan

The Taiji dolphin drive hunt captures small cetaceans for their meat and for sale to dolphinariums. Taiji has a long connection to Japanese whaling. The 2009 documentary film The Cove drew international attention to the hunt. Taiji is the only town in Japan where drive hunting still takes place on a large scale. Concern is majority through the methodology of the hunt, as actions are viewed as inhumane. An article by National Geographic refers to The Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums' decision to no longer support the Taiji hunt. In 2015, it was announced that there would be a ban in the buying and selling of dolphins through the means of this hunt.

Kiribati

Similar drive hunting existed in Kiribati at least until the mid-20th century.

Peru

Though it is forbidden under Peruvian law to hunt dolphins or eat their meat (sold as chancho marino, or sea pork in English), a large number of dolphins are still killed illegally by fishermen each year. To catch the dolphins, they are driven together with boats and encircled with nets, then harpooned, dragged on to the boat, and clubbed to death if still alive. Various species are hunted, such as the bottlenose and dusky dolphin.

According to estimates from local animal welfare organisation Mundo Azul released in October 2013, between 1,000 and 2,000 dolphins are killed annually for consumption, with a further 5,000 to 15,000 being killed for use as shark bait. Sharks are captured both for their meat and for use of their fins in shark fin soup.

Solomon Islands

Main article: Malaita dolphin drive hunt

Dolphin are hunted in Malaita, in the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific, mainly for their meat and teeth, and also sometimes for live capture for dolphinariums. The hunt on South Malaita Island is smaller in scale than Tajai. After capture, the meat is shared equally between households. Dolphin teeth are also used in jewelry and as currency on the island.

Taiwan

On the Penghu Islands in Taiwan, drive fishing of bottlenose dolphins was practiced until 1990, when the practice was outlawed by the government. Mainly Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphins but also common bottlenose dolphins were captured in these hunts.

United States

See also: Whaling in the United StatesNew England

From 1644 at Southampton, New York, on Long Island, the colonists established an organised whale fishery, chasing pilot whales ("blackfish") onto the shelving beaches for slaughter. They also processed drift whales they found on shore. They observed the Native Americans hunting techniques, improved on their weapons and boats, and then went out to ocean hunting.

Hawaii

In ancient Hawaii, fishermen occasionally hunted dolphins for their meat by driving them onto the beach and killing them. In their ancient legal system, dolphin meat was considered to be kapu (forbidden) for women together with several other kinds of food. As of 2008, dolphin drive hunting no longer takes place in Hawaii.

Texas

Hunting dolphins (at the time still often incorrectly referred to as fish or porpoises), primarily using harpoons and firearms, was considered a form of recreational hunting along the shores of the Gulf of Mexico in Texas in the late 19th and early 20th century. Pleasure dolphin hunting cruises could be booked in Corpus Christi in the 1920s, with a promise to tourists that if no successful dolphin kill was made, the excursion would be free of charge. The brutality of the practice started to spark animal welfare concerns and there is no reference of this practice still occurring in Texas after the Second World War.

Washington

Drive hunting methods were used to capture orcas in Puget Sound in the 1960s and 1970s. These hunts were led by aquarium owner and entrepreneur Edward "Ted" Griffin and his partner Don Goldsberry. After Griffin purchased an orca that was caught by accident by fishermen in Namu, British Columbia, in 1965, Griffin and Goldsberry used drive hunting techniques in the Puget Sound area to capture orcas for the entertainment industry. They implemented their new methods for orca capture in their Yukon Harbor operation in 1967. Others followed and despite the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 the practice continued until 1976 when the state of Washington ordered the release of a number of orcas that were being held in Budd Inlet and subsequently banned the practice.

See also

References

- "Report: 100,000+ Dolphins, Small Whales and Porpoises Slaughtered Globally Each Year". 7 August 2018.

- Walker, Harlan (1995). Disappearing Foods: Studies in Foods and Dishes at Risk. Oxford Symposium. ISBN 9780907325628.

- ^ logir.fo

- Grind | Hagstova Føroya

- "Grinds de 2000 à 2013". www.whaling.fo/ Catch figures. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014.

- Bertholdsen, Áki (5 March 2015). "Nú eru 1380 føroyingar klárir at fara í grind" (in Faroese). Sosialurin - in.fo. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "Løgtingslóg um grind og annan smáhval, sum seinast broytt við løgtingslóg nr. 93 frá 22. juni 2015" (in Faroese). Logir.fo. 19 May 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- theecologist.org

- Barrat, Harry (3 February 2014). "Whaling in the Faroe Islands: a cruel and unnecessary ritual or sustainable food practice?". The Knowledge. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Duignan, Brian (26 April 2010). "The Faroe Islands Whale Hunt". Encyclopædia Britannica - Advocacy for Animals. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- "landslaeknin.fo" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- MacKenzie, Debora (28 November 2008). "Faroe islanders told to stop eating 'toxic' whales". New Scientist. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- hsf.fo – the Faroese Food- and veterinary authority Archived 10 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kyksilvur í grind". Archived from the original on 6 February 2015.

- United States Navy Archive / Naval Aviation News (1956) Killer Whales Destroyed - VP-7 accomplishes special task Archived 9 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- PBS - Frontline - A whale of a business - historical chronology, article retrieved 9 March 2014.

- British diplomat Arthur Grimble's memoir, A Pattern of Islands (1952)

- Hall, Kevin G. (2003). "Dolphin meat widely available in Peruvian stores: Despite protected status, 'sea pork' is popular fare". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- Stefan Austermühle (2003), Peru's Illegal Dolphin Hunting Kills 1,000 Dolphins or More, article retrieved on 21 June 2008. Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Hispanic Business (2013), Peruvian Officials to Take Action to Deal with Dolphin Slaughter Archived 30 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, article retrieved 30 October 2013.

- All Voices (2013), Fishermen butchering dolphins for shark bait sparks global outrage Archived 2013-11-02 at the Wayback Machine, article retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Rodriguez, Cindy; Romo, Rafael (23 October 2013). "Dolphins killed for shark bait in Peru". CNN. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- Takekawa, Daisuke (2000). Hunting method and the ecological knowledge of dolphins among the Fanalei villagers of Malaita, Solomon Islands (PDF). SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin No. 12. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Takekawa Daisuke & Ethel Falu (1995, 2006), Dolphin hunting in the Solomon Islands Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, article retrieved on 21 June 2008.

- R. R. Reeves, W. F. Perrin, B. L. Taylor, C. S. Baker and S. L. Mesnick (2004), Report of the Workshop on Shortcomings of Cetacean Taxonomy in Relation to Needs of Conservation and Management, page 27, section Management of cetacean exploitation. Article retrieved on 21 October 2006.

- Federal Writers' Project. Whaling Masters. Works Progress Administration.

- Earthtrust (year unknown), - Hunting/Subsistence Use, article retrieved on 21 June 2008.

- ^ Allison Ehrlich, David Sikes for the Corpus Christi Caller (2011), Bottlenose dolphins make journey from harpoon target to darling of the sea, article retrieved 9 March 2014.

- The Galveston Daily News (1936) / Newspaper Archive Man who had porpoise on line tells of companion's loyalty and pitiful moans.

- PBS - Edward "Ted" Griffin - The Life and Adventures of a man who caught Killer Whales, article retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Colby, Jason M. (2018). Orca: how we came to know and love the ocean's greatest predator. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780190673116.

- Timothy Egan, The Good Rain: Across Time & Terrain in the Pacific Northwest, page 141.

External links

- atlanticblue - The inhumane dolphin slaughter in Taiji, Japan 2011

- BBC news - dining with the dolphin hunters in Japan

- Faroe Islands official whaling website

- EIA reports: Up to date info.

- EIA in the USA - reports on drive hunts: Up to date reports and info

- Atlanticblue e.V. website, with current information about the Taiji dolphin hunt in Japan (German only)

- Create worldwide awareness of dolphin slaughter and high level of toxic mercury in dolphin meat Archived 6 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- 3D animation of how a drive works, including links to two videos

- Video at Glumbert.com - well known footage of a drive hunt in Futo in 1999

- Matt Damon Narrated Film via EducatedEarth

- Video report produced by BlueVoice.org

- Video about the Taiji drive hunts from November 2007 produced by atlanticblue.de

- CNN report on the Taiji drive hunts, 11 February 2008.

- Mercury poisoning

- http://www.theage.com.au/national/mercury-poisoning-linked-to-dolphin-deaths-20080605-2mbw.html

- http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20090923f2.html

- http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/20/world/asia/20iht-dolphin.1.10223011.html

| Whaling | |

|---|---|

| History of whaling | |

| By country | |

| Harpoons | |

| Hunting type | |

| Implements | |

| Products | |

| Regulations | |

| Sanctuaries | |

Categories: