| Revision as of 21:22, 26 October 2006 view source72.22.138.12 (talk) →References← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:07, 20 December 2024 view source AnomieBOT (talk | contribs)Bots6,554,066 edits Rescuing orphaned refs ("gs.statcounter.com" from rev 1263519050; ":0" from rev 1263519050) | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Software that manages computer hardware resources}} | |||

| {{Cleanup-date|July 2006}}{{expert}} | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

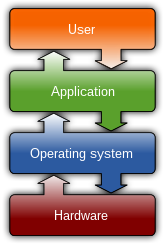

| An '''operating system''' ('''OS''') is a ] that manages the ] and ] resources of a ]. At the foundation of all system software, the OS performs basic tasks such as controlling and allocating ], prioritizing system requests, controlling input and output devices, facilitating ], and managing ]s. It also may provide a ] for higher level functions. | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2015}} | |||

| {{OS}} | |||

| An '''operating system''' ('''OS''') is ] that manages ] and ] resources, and provides common ] for ]s. | |||

| ] operating systems ] for efficient use of the system and may also include accounting software for cost allocation of ], ], peripherals, and other resources. | |||

| == Introduction == | |||

| ] as a series of ]s: ], ], ], ], ] and ] (see also Tanenbaum 79).]] | |||

| Modern ''general-purpose computers'', including ]s and ], have an operating system (a ''general purpose operating system'') to run other programs, such as ]. Examples of operating systems for personal computers include ], ], and ]. | |||

| For hardware functions such as ] and ], the operating system acts as an intermediary between programs and the computer hardware,<ref>{{cite book | last = Stallings | title = Operating Systems, Internals and Design Principles | publisher = Prentice Hall | year = 2005 | location = Pearson |page=6}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last = Dhotre| first = I.A.| title = Operating Systems. | publisher = Technical Publications | year = 2009 |page=1}}</ref> although the application code is usually executed directly by the hardware and frequently makes ]s to an OS function or is ]ed by it. Operating systems are found on many devices that contain a computer{{snd}}from cellular phones and video game consoles to ]s and ]s. | |||

| <!-- The main advantages of an operating system include: | |||

| #Allows multiple programs to run concurrently. | |||

| #Simplifies the programming of application software because the program does not have to manage the hardware. The operating systems manages all hardware and the interaction of software. It also gives the program a high level interface to the hardware and ways of interacting with other programs. | |||

| {{as of|2024|09|}}, ] is the most popular operating system with a 46% market share, followed by ] at 26%, ] and ] at 18%, ] at 5%, and ] at 1%. Android, iOS, and iPadOS are mobile operating systems, while Windows, macOS, and Linux are desktop operating systems.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Operating System Market Share Worldwide |url=https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share |access-date=2024-12-20 |website=StatCounter Global Stats |language=en}}</ref> ]s are dominant in the server and supercomputing sectors. Other specialized classes of operating systems (special-purpose operating systems),<ref name="auto">{{Cite web|url=https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/operating-system-concepts/9780471694663/pt07.html|title=VII. Special-Purpose Systems - Operating System Concepts, Seventh Edition |website=www.oreilly.com|access-date=8 February 2021|archive-date=13 June 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210613190049/https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/operating-system-concepts/9780471694663/pt07.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.acs.eonerc.rwth-aachen.de/cms/E-ON-ERC-ACS/Studium/Lehrveranstaltungen/~lrhs/Spezial-Betriebssysteme/?lidx=1|title=Special-Purpose Operating Systems - RWTH AACHEN UNIVERSITY Institute for Automation of Complex Power Systems - English|website=www.acs.eonerc.rwth-aachen.de|access-date=8 February 2021|archive-date=14 June 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210614034001/https://www.acs.eonerc.rwth-aachen.de/cms/E-ON-ERC-ACS/Studium/Lehrveranstaltungen/~lrhs/Spezial-Betriebssysteme/?lidx=1|url-status=live}}</ref> such as ] and real-time systems, exist for many applications. ]s also exist. Some operating systems have low system requirements (e.g. ]). Others may have higher system requirements. | |||

| This is completely off-base: while modern operating systems tend to run programs concurrently, older systems (such as MS-DOS, CP/M, etc.) were single-tasking; and it is pointless to have a list for only one item. Someone (or myself, if I have the time later to do so) will have to review and edit for accuracy. ~~~~ --> | |||

| <!-- need more reasons of the advantages of OSs--> | |||

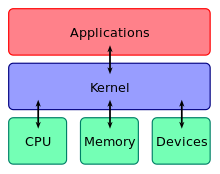

| The lowest level of any operating system is its ]. This is the first layer of software loaded into memory when a system ] or starts up. The kernel provides access to various common core services to all other system and application programs. These services include, but are not limited to: task scheduling, memory management, disk access, and access to ]. | |||

| Some operating systems require installation or may come pre-installed with purchased computers (]-installation), whereas others may run directly from media (i.e. ]) or flash memory (i.e. ] stick). | |||

| ] | |||

| Apart from the kernel, an operating system is often distributed with ] that manages a ] (although Windows and Macintosh have integrated these programs into the operating system), as well as ]s for tasks such as managing files and configuring the operating system. Oftentimes distributed with operating systems are application software that does not directly relate to the operating system's core function, but which the operating system distributor finds advantageous to supply with the operating system. | |||

| ==Definition and purpose== | |||

| Delineating between the operating system and application software is not a completely precise activity, and is occasionally subject to controversy. From commercial or legal points of view, the delineation can depend on the contexts of the interests involved. For example, one of the key questions in the ] ] trial was whether Microsoft's ] was part of its operating system, or whether it was a separable piece of application software. | |||

| An operating system is difficult to define,{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=4}} but has been called "the ] that manages a computer's resources for its users and their ]s".{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=6}} Operating systems include the software that is always running, called a ]—but can include other software as well.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=4}}{{sfn|Silberschatz et al.|2018|p=6}} The two other types of programs that can run on a computer are ]s—which are associated with the operating system, but may not be part of the kernel—and applications—all other software.{{sfn|Silberschatz et al.|2018|p=6}} | |||

| There are three main purposes that an operating system fulfills:{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=7}} | |||

| Like the term "operating system" itself, the question of what exactly the "kernel" should manage is subject to some controversy, with debates over whether things like ]s should be included in the kernel. Various camps advocate ]s, ], and so on. | |||

| *Operating systems allocate resources between different applications, deciding when they will receive ] (CPU) time or space in ].{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=7}} On modern personal computers, users often want to run several applications at once. In order to ensure that one program cannot monopolize the computer's limited hardware resources, the operating system gives each application a share of the resource, either in time (CPU) or space (memory).{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=9–10}}{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=6-7}} The operating system also must isolate applications from each other to protect them from errors and security vulnerabilities in another application's code, but enable communications between different applications.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=10}} | |||

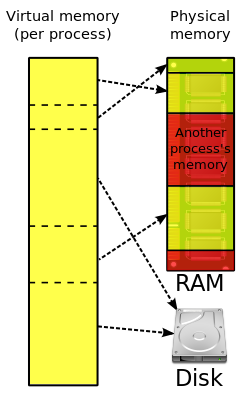

| *Operating systems provide an interface that abstracts the details of accessing ] details (such as physical memory) to make things easier for programmers.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=7}}{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=5}} ] also enables the operating system to mask limited hardware resources; for example, ] can provide a program with the illusion of nearly unlimited memory that exceeds the computer's actual memory.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=11}} | |||

| *Operating systems provide common services, such as an interface for accessing network and disk devices. This enables an application to be run on different hardware without needing to be rewritten.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=7, 9, 13}} Which services to include in an operating system varies greatly, and this functionality makes up the great majority of code for most operating systems.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=12–13}} | |||

| ==Types of operating systems== | |||

| Operating systems are used on most, but not all, computer systems. The simplest computers, including the smallest ]s and many of the first computers did not have operating systems. Instead, they relied on the application programs to manage the minimal hardware themselves, perhaps with the aid of ] developed for the purpose. Commercially-supplied operating systems are present on virtually all modern devices described as computers, from ]s to ]s, as well as mobile computers such as ]s and ]s. | |||

| ===Multicomputer operating systems=== | |||

| With ]s multiple CPUs share memory. A ] or ] has multiple CPUs, each of which ]. Multicomputers were developed because large multiprocessors are difficult to engineer and prohibitively expensive;{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=557}} they are universal in ] because of the size of the machine needed.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=558}} The different CPUs often need to send and receive messages to each other;{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=565}} to ensure good performance, the operating systems for these machines need to minimize this copying of ]s.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=562}} Newer systems are often ]—separating groups of users into separate ]s—to reduce the need for packet copying and support more concurrent users.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=563}} Another technique is ], which enables each CPU to access memory belonging to other CPUs.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=565}} Multicomputer operating systems often support ]s where a CPU can call a ] on another CPU,{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=569}} or ], in which the operating system uses ] to generate shared memory that does not physically exist.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=571}} | |||

| ===Distributed systems=== | |||

| ==Services== | |||

| A ] is a group of distinct, ] computers—each of which might have their own operating system and file system. Unlike multicomputers, they may be dispersed anywhere in the world.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=579}} ], an additional software layer between the operating system and applications, is often used to improve consistency. Although it functions similarly to an operating system, it is not a true operating system.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=581}} | |||

| ===Process management=== | |||

| Every action on a computer, be it background services or applications, is run inside a process. | |||

| As long as a ] is used to build computers, only one process per CPU can be run at a time. Older OS such as MS-DOS did not attempt any artifacts to bypass this limit and in fact only one process could be run under them (although DOS itself featured ] as a very partial and not too easy to use solution). Modern operating systems are able to simulate execution of many processes at once (multi-tasking) even under a single CPU. | |||

| Process management is an operating system's way of dealing with running multiple processes. Since most computers contain one processor with one core, multi-tasking is accomplished by simply switching processes quickly. As a user runs more processes, all timeshares become smaller. On many systems, this can eventually lead to problems such as skipping of audio or jittery mouse movement (this is called ''thrashing'', a state in which OS related activity becomes the only thing a computer does). Process management involves the computation and distribution of "timeshares". Most operating systems allow a process to be assigned a process priority which impacts its timeshare. Interactive operating systems also employ some level of feedback in which the task with which the user is working receives a priority boost. | |||

| === |

===Embedded=== | ||

| ]s are designed to be used in ], whether they are ] objects or not connected to a network. Embedded systems include many household appliances. The distinguishing factor is that they do not load user-installed software. Consequently, they do not need protection between different applications, enabling simpler designs. Very small operating systems might run in less than 10 ],{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=37-38}} and the smallest are for ].{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=39}} Examples include ], ], ], and the extra-small systems ] and ].{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=38}} | |||

| According to '''Parkinson''''s law "'''Programs expand to fill the memory available to hold them'''". Thus the programmers like a memory of '''infinite size''' and '''infinite speed'''. Nowadays most of the computer's memory is arranged in a hierarchical manner, starting from fastest registers, cache, RAM and disk storage. The '''memory manager''' in an OS coordinates the memories by tracking which one is available, which is to be allocated or deallocated and how to swap between the main memory and secondary memories. This activity which is usually referred to as ''virtual memory management'' greatly increases the amount of memory available for a process (typically 4GB, even if the physical RAM available is less). This however comes at a speed penalty which is usually low, but can become very high in extreme cases and, again, lead to ]. | |||

| ===Real-time=== | |||

| Another important part of memory management activity is managing virtual addresses, with help from the CPU. If multiple processes are in memory at once, they must be prevented from interfering with each other's memory (unless there is an explicit request to share for a limited amount of memory and in controlled ways). This is achieved by having separate address spaces. Each process in fact sees the whole virtual address space (typically, from address 0 up to the maximum size of virtual memory) as uniquely assigned to it (ignoring the fact that some areas are OS reserved). What actually happens is that the CPU stores some tables to match virtual addresses to physical addresses. | |||

| A ] is an operating system that guarantees to process ] or data by or at a specific moment in time. Hard real-time systems require exact timing and are common in ], ], military, and other similar uses.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=38}} With soft real-time systems, the occasional missed event is acceptable; this category often includes audio or multimedia systems, as well as smartphones.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=38}} In order for hard real-time systems be sufficiently exact in their timing, often they are just a library with no protection between applications, such as ].{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=38}} | |||

| ===Hypervisor=== | |||

| By creating a separate address space for each process, it is also simple for the operating system to free all of the memory that was used by a particular process. If a process does not free memory, this is unimportant once the process ends and the memory is all released. | |||

| A ] is an operating system that runs a ]. The virtual machine is unaware that it is an application and operates as if it had its own hardware.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=11}}{{sfn|Silberschatz et al.|2018|pp=701}} Virtual machines can be paused, saved, and resumed, making them useful for operating systems research, development,{{sfn|Silberschatz et al.|2018|pp=705}} and debugging.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=12}} They also enhance portability by enabling applications to be run on a computer even if they are not compatible with the base operating system.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=11}} | |||

| === |

===Library=== | ||

| A ''library operating system'' (libOS) is one in which the services that a typical operating system provides, such as networking, are provided in the form of ] and composed with a single application and configuration code to construct a ]: | |||

| Operating systems have a variety of native file systems. Linux has a greater range of native file systems, those being: ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. Linux also has full support for ] and ], along with the ] file systems, and ]. Windows on the other hand has limited file system support which only includes: FAT12, FAT16, FAT32, and NTFS. The NTFS file system is the most efficient and reliable of the four Windows systems. All the FAT systems are older than NTFS and have limitations on the partition and file size that can cause a variety of problems. | |||

| <ref name="Unikernels">{{cite magazine | |||

| |last1=Madhavapeddy |first1=Anil | |||

| |last2=Scott |first2=David J | |||

| |date=November 2013 | |||

| |title=Unikernels: Rise of the Virtual Library Operating System: What if all the software layers in a virtual appliance were compiled within the same safe, high-level language framework? | |||

| |magazine=Queue |volume=11 |issue=11 | |||

| |pages=30–44 | |||

| |location=New York, NY, USA | |||

| |publisher=ACM | |||

| |issn=1542-7730 | |||

| |url=https://doi.org/10.1145/2557963.2566628 | |||

| |doi=10.1145/2557963.2566628 | |||

| |access-date=2024-08-07 | |||

| }}</ref> a specialized (only the absolute necessary pieces of code are extracted from libraries and bound together | |||

| <ref name="Unikraft-Build-Process">{{cite web | |||

| |url=https://unikraft.org/docs/concepts/build-process | |||

| |access-date=2024-08-08 | |||

| |title=Build Process - Unikraft | |||

| |archive-date=2024-04-22 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240422183734/https://unikraft.org/docs/concepts/build-process | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref>), ], machine image that can be deployed to cloud or embedded environments. | |||

| The operating system code and application code are not executed in separated ] (there is only a single application running, at least conceptually, so there is no need to prevent interference between applications) and OS services are accessed via simple library calls (potentially ] them based on compiler thresholds), without the usual overhead of ]es, | |||

| For most of the above file systems there are two ways it can be allocated. Each system can be ] or non-journaled. Journaled being the safer alternative under the circumstances of a system recovery. If a system comes to an abrupt stop, in a system crash scenario, the non-journaled system will need to undergo an examination from the system check utilities where as the journaled file systems recovery is automatic. Microsoft's NTFS is journaled along with most Linux file systems, except ext2, but including ext3, reiserfs and JFS. | |||

| <ref name="rise-of-libOS">{{cite web | |||

| |url=https://www.sigarch.org/leave-your-os-at-home-the-rise-of-library-operating-systems/ | |||

| |access-date=2024-08-07 | |||

| |title=Leave your OS at home: the rise of library operating systems | |||

| |date=2017-09-14 | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |archive-date=2024-03-01 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240301072916/https://www.sigarch.org/leave-your-os-at-home-the-rise-of-library-operating-systems/ | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> in a way similarly to embedded and real-time OSes. Note that this overhead is not negligible: to the direct cost of mode switching it's necessary to add the indirect pollution of important processor structures (like ]s, the ], and so on) which affects both user-mode and kernel-mode performance. | |||

| <ref name="FlexSC">{{cite conference | |||

| |url=https://www.usenix.org/conference/osdi10/flexsc-flexible-system-call-scheduling-exception-less-system-calls | |||

| |title=FlexSC: Flexible System Call Scheduling with Exception-Less System Calls | |||

| |last1=Soares |first1=Livio Baldini <!-- https://liviosoares.github.io/ --> | |||

| |last2=Stumm |first2=Michael <!-- https://www.eecg.toronto.edu/~stumm/index.html --> | |||

| |date=2010-10-04 | |||

| |conference=OSDI '10, 9th USENIX Symposium on Operating System Design and Implementation | |||

| |conference-url=https://www.usenix.org/legacy/events/osdi10/ | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |access-date=2024-08-09 | |||

| |quote=Synchronous implementation of system calls negatively impacts the performance of system intensive workloads, both in terms of the ''direct'' costs of mode switching and, more interestingly, in terms of the ''indirect'' pollution of important processor structures which affects both user-mode and kernel-mode performance. A motivating example that quantifies the impact of system call pollution on application performance can be seen in Figure 1. It depicts the user-mode instructions per cycles (kernel cycles and instructions are ignored) of one of the SPEC CPU 2006 benchmarks (Xalan) immediately before and after a <code>pwrite</code> system call. There is a significant drop in instructions per cycle (IPC) due to the system call, and it takes up to 14,000 cycles of execution before the IPC of this application returns to its previous level. As we will show, this performance degradation is mainly due to interference caused by the kernel on key processor structures. | |||

| |quote-page=2 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Every file system is made up of similar directories and subdirectories. Along with the operating systems file system similarities there are the subtle differences. Microsoft separates its directories with a back slash and its file names aren't case sensitive whereas Unix-derived operating systems (including Linux) use the forward slash and their file names generally are case sensitive. | |||

| {{Main|History of operating systems}} | |||

| ] used by the operating system to communicate with the operator.]] | |||

| The first computers in the late 1940s and 1950s were directly programmed either with ]s or with ] inputted on media such as ]s, without ]s or operating systems.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=8}} After the introduction of the ] in the mid-1950s, ]s began to be built. These still needed professional operators{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=8}} who manually do what a modern operating system would do, such as scheduling programs to run,<ref name="OSTEP book">{{cite book |last1=Arpaci-Dusseau |first1=Remzi |last2=Arpaci-Dusseau |first2=Andrea |year=2015 |url=http://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~remzi/OSTEP/ |title=Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces |access-date=25 July 2016 |archive-date=25 July 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160725012948/http://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~remzi/OSTEP/ |url-status=live }}</ref> but mainframes still had rudimentary operating systems such as ] (FMS) and ].{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=10}} In the 1960s, ] introduced the first series of intercompatible computers (]). All of them ran the same operating system—]—which consisted of millions of lines of ] that had thousands of ]s. The OS/360 also was the first popular operating system to support ], such that the CPU could be put to use on one job while another was waiting on ] (I/O). Holding multiple jobs in ] necessitated memory partitioning and safeguards against one job accessing the memory allocated to a different one.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=11–12}} | |||

| ===Networking=== | |||

| Most current operating systems are capable of using the now-universal TCP/IP networking protocols. This means that one system can appear on a network of the other and share resources such as files, printers, and scanners. | |||

| Around the same time, ]s began to be used as ]s so multiple users could access the computer simultaneously. The operating system ] was intended to allow hundreds of users to access a large computer. Despite its limited adoption, it can be considered the precursor to ]. The ] operating system originated as a development of MULTICS for a single user.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=13–14}} Because UNIX's ] was available, it became the basis of other, incompatible operating systems, of which the most successful were ]'s ] and the ]'s ] (BSD).{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=14–15}} To increase compatibility, the ] released the ] standard for operating system ]s (APIs), which is supported by most UNIX systems. ] was a stripped-down version of UNIX, developed in 1987 for educational uses, that inspired the commercially available, ] ]. Since 2008, MINIX is used in controllers of most ] ], while Linux is widespread in ]s and ] smartphones.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=15}} | |||

| Many operating systems also support one or more vendor-specific legacy networking protocols as well, for example, ] on ] systems, ] on systems from ], and Microsoft-specific protocols on Windows. Specific protocols for specific tasks may also be supported such as ] for file access. | |||

| === |

===Microcomputers=== | ||

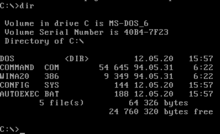

| ] of the ] operating system]] | |||

| Many operating systems include some level of security. Security is based on the two ideas that: | |||

| ] of a ]]] | |||

| * The operating system provides access to a number of resources, directly or indirectly, such as files on a local disk, privileged system calls, personal information about users, and the services offered by the programs running on the system; | |||

| The invention of ] enabled the production of ]s (initially called ]s) from around 1980.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=15–16}} For around five years, the ] (Control Program for Microcomputers) was the most popular operating system for microcomputers.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=16}} Later, IBM bought the ] (Disk Operating System) from ]. After modifications requested by IBM, the resulting system was called ] ({{not a typo|Micro|Soft}} Disk Operating System) and was widely used on IBM microcomputers. Later versions increased their sophistication, in part by borrowing features from UNIX.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=16}} | |||

| * The operating system is capable of distinguishing between some requestors of these resources who are authorized (allowed) to access the resource, and others who are not authorized (forbidden). While some systems may simply distinguish between "privileged" and "non-privileged", systems commonly have a form of requestor ''identity'', such as a user name. Requestors in turn divide into two categories: | |||

| :*Internal security: an already running program. On some systems, a program once it has running has no limitations, but commonly the program has an identity which it keeps and is used to check all of its requests for resources. | |||

| :*External security: a new request from outside the computer, such as a login at a connected console or some kind of network connection. To establish identity there may be a process of ''authentication''. Often a username must be quoted, and each username may have a password. Other methods of authentication such as magnetic cards or biometric data might be used instead. In some cases, especially connections from the network, resources may be accessed with no authentication at all. | |||

| ]'s ] was the first popular computer to use a ] (GUI). The GUI proved much more ] than the text-only ] earlier operating systems had used. Following the success of Macintosh, MS-DOS was updated with a GUI overlay called ]. Windows later was rewritten as a stand-alone operating system, borrowing so many features from another (]) that a large ] was paid.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=17}} In the twenty-first century, Windows continues to be popular on personal computers but has less ] of servers. UNIX operating systems, especially Linux, are the most popular on ]s and servers but are also used on mobile devices and many other computer systems.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=18}} | |||

| In addition to the allow/disallow model of security, a system with a high level of security will also offer auditing options. These would allow tracking of requests for access to resources (such as "who has been reading this file"?) | |||

| On mobile devices, ] was dominant at first, being usurped by ] (introduced 2002) and ] for ]s (from 2007). Later on, the open-source ] operating system (introduced 2008), with a Linux kernel and a C library (]) partially based on BSD code, became most popular.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=19–20}} | |||

| Security of operating systems has long been a concern because of highly sensitive data held on computers, both of a commercial and military nature. The ] ] ] (DoD) created the '']'' (TCSEC), which is a standard that sets basic requirements for assessing the effectiveness of security. This became of vital important to operating system makers, because the TCSEC was used to evaluate, classify and select computer systems being considered for the processing, storage and retrieval of sensitive or ]. | |||

| ==Components== | |||

| ====Internal security==== | |||

| The components of an operating system are designed to ensure that various parts of a computer function cohesively. With the de facto obsoletion of ], all user ] must interact with the operating system to access hardware. | |||

| ===Kernel=== | |||

| Internal security can be thought of as protecting the computer's resources from the programs already running on the computer. Most operating systems set programs running natively on the computer's processor, so the problem arises of how to stop these programs doing the same task, and having the same privileges, as the operating system, which is after all just a program too? Processors used for general purpose operating systems generally have a hardware concept of privilege. Generally less privileged programs are automatically blocked from using certain hardware instructions, such as those to read or write from external devices like disks. Instead, they have to ask the privileged program (operating system) to read or write. The operating system therefore gets the chance to check the program's identity and allow or refuse the request. | |||

| {{Main|Kernel (operating system)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The kernel is the part of the operating system that provides ] between different applications and users. This protection is key to improving reliability by keeping errors isolated to one program, as well as security by limiting the power of ] and protecting private data, and ensuring that one program cannot monopolize the computer's resources.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=39–40}} Most operating systems have two modes of operation:{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=2}} in ], the hardware checks that the software is only executing legal instructions, whereas the kernel has ] and is not subject to these checks.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=41, 45}} The kernel also manages ] for other processes and controls access to ] devices.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=52-53}} | |||

| An alternative strategy, and the only strategy available where the operating system and user programs have the same hardware privilege, is that the the operating system does not run user programs as native code, but instead either ] a processor or provides a host for a ] based system such as Java. | |||

| ====Program execution==== | |||

| Internal security is especially relevant for multi-user systems; it allows each user of the system to have private files that the other users cannot tamper with or read. Internal security is also vital if auditing is to be of any use, since if a program can bypass the operating system it can also bypass auditing. | |||

| The operating system provides an interface between an application program and the computer hardware, so that an application program can interact with the hardware only by obeying rules and procedures programmed into the operating system. The operating system is also a set of services which simplify development and execution of application programs. Executing an application program typically involves the creation of a ] by the operating system ], which assigns memory space and other resources, establishes a priority for the process in multi-tasking systems, loads program binary code into memory, and initiates execution of the application program, which then interacts with the user and with hardware devices. However, in some systems an application can request that the operating system execute another application within the same process, either as a subroutine or in a separate thread, e.g., the '''LINK''' and '''ATTACH''' facilities of ]. | |||

| ==== |

====Interrupts==== | ||

| {{Main|Interrupt}} | |||

| An ] (also known as an ], ], ''fault'', ],<ref name="lpi-ch20-p388_quote1">{{cite book | |||

| <!-- Major rewrite pending on the following --> | |||

| | last = Kerrisk | |||

| Typically an operating system offers (hosts) various services to other network computers and users. These services are usually provided through ports or numbered access points beyond the operating systems network address. Typically services include offerings such as file sharing, print services, email, web sites, and file transfer protocols. | |||

| | first = Michael | |||

| At the front line of security are hardware devices known as ]. At the operating system level there are various software firewalls. A software firewall is configured to allow or deny traffic to a service running on top of the operating system. Therefore one can install and be running an insecure service, such as Telnet or FTP, and not have to be threatened by a security breach because the firewall would deny all traffic trying to connect to the service on that port. | |||

| | title = The Linux Programming Interface | |||

| | publisher = No Starch Press | |||

| | year = 2010 | |||

| | page = 388 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-59327-220-3 | |||

| | quote = A signal is a notification to a process that an event has occurred. Signals are sometimes described as software interrupts. | |||

| }}</ref> or ''trap'')<ref name="Hyde_1996">{{cite book | |||

| |last1 = Hyde | |||

| |first1 = Randall | |||

| |chapter-url = https://www.plantation-productions.com/Webster/www.artofasm.com/DOS/ch17/CH17-1.html#HEADING1-0 | |||

| |access-date = 22 December 2021 | |||

| |date = 1996 | |||

| |title = The Art Of Assembly Language Programming | |||

| |chapter = Chapter Seventeen: Interrupts, Traps and Exceptions (Part 1) | |||

| |publisher = No Starch Press | |||

| |quote = The concept of an interrupt is something that has expanded in scope over the years. The 80x86 family has only added to the confusion surrounding interrupts by introducing the int (software interrupt) instruction. Indeed, different manufacturers have used terms like exceptions, faults, aborts, traps and interrupts to describe the phenomena this chapter discusses. Unfortunately there is no clear consensus as to the exact meaning of these terms. Different authors adopt different terms to their own use. | |||

| |archive-date = 22 December 2021 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20211222205623/https://www.plantation-productions.com/Webster/www.artofasm.com/DOS/ch17/CH17-1.html#HEADING1-0 | |||

| |url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> provides an efficient way for most operating systems to react to the environment. Interrupts cause the ] (CPU) to have a ] change away from the currently running program to an ], also known as an interrupt service routine (ISR).<ref name="sco-ch5-p308_a">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Tanenbaum | |||

| | first = Andrew S. | |||

| | title = Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition | |||

| | publisher = Prentice Hall | |||

| | year = 1990 | |||

| | page = | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-13-854662-5 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/structuredcomput00tane/page/308 | |||

| | quote = Like the trap, the interrupt stops the running program and transfers control to an interrupt handler, which performs some appropriate action. When finished, the interrupt handler returns control to the interrupted program. | |||

| }}</ref><ref name="osc-ch2-p32_a">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Silberschatz | |||

| | first = Abraham | |||

| | title = Operating System Concepts, Fourth Edition | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | page = 32 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-201-50480-4 | |||

| | quote = When an interrupt (or trap) occurs, the hardware transfers control to the operating system. First, the operating system preserves the state of the CPU by storing registers and the program counter. Then, it determines which type of interrupt has occurred. For each type of interrupt, separate segments of code in the operating system determine what action should be taken.}}</ref> An interrupt service routine may cause the ] (CPU) to have a ].<ref name="osc-ch4-p105">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Silberschatz | |||

| | first = Abraham | |||

| | title = Operating System Concepts, Fourth Edition | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | page = 105 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-201-50480-4 | |||

| | quote = Switching the CPU to another process requires saving the state of the old process and loading the saved state for the new process. This task is known as a context switch.}}</ref>{{efn|Modern CPUs provide instructions (e.g. SYSENTER) to invoke selected kernel services without an interrupts. Visit https://wiki.osdev.org/SYSENTER for more information.}} The details of how a computer processes an interrupt vary from architecture to architecture, and the details of how interrupt service routines behave vary from operating system to operating system.<ref name="osc-ch2-p31">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Silberschatz | |||

| | first = Abraham | |||

| | title = Operating System Concepts, Fourth Edition | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | page = 31 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-201-50480-4 | |||

| }}</ref> However, several interrupt functions are common.<ref name="osc-ch2-p31"/> The architecture and operating system must:<ref name="osc-ch2-p31"/> | |||

| # transfer control to an interrupt service routine. | |||

| # save the state of the currently running process. | |||

| # restore the state after the interrupt is serviced. | |||

| === |

=====Software interrupt===== | ||

| A software interrupt is a message to a ] that an event has occurred.<ref name="lpi-ch20-p388_quote1"/> This contrasts with a ''hardware interrupt'' — which is a message to the ] (CPU) that an event has occurred.<ref name="osc-ch2-p30">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Silberschatz | |||

| | first = Abraham | |||

| | title = Operating System Concepts, Fourth Edition | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | page = 30 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-201-50480-4 | |||

| | quote = Hardware may trigger an interrupt at any time by sending a signal to the CPU, usually by way of the system bus. | |||

| }}</ref> Software interrupts are similar to hardware interrupts — there is a change away from the currently running process.<ref name="lpi-ch20-p388_quote2">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Kerrisk | |||

| | first = Michael | |||

| | title = The Linux Programming Interface | |||

| | publisher = No Starch Press | |||

| | year = 2010 | |||

| | page = 388 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-59327-220-3 | |||

| | quote = Signals are analogous to hardware interrupts in that they interrupt the normal flow of execution of a program; in most cases, it is not possible to predict exactly when a signal will arrive. | |||

| }}</ref> Similarly, both hardware and software interrupts execute an ]. | |||

| Software interrupts may be normally occurring events. It is expected that a ] will occur, so the kernel will have to perform a ].<ref name="lpi-ch20-p388_quote3">{{cite book | |||

| Today, most modern operating systems contain ] (GUIs, pronounced ''gooeys''). A few older operating systems tightly integrated the GUI to the ]—for example, the original implementations of Windows and Mac OS. More modern operating systems are ], separating the graphics subsystem from the kernel (as is now done in Linux, and Mac OS X, and to a limited extent Windows). | |||

| | last = Kerrisk | |||

| | first = Michael | |||

| | title = The Linux Programming Interface | |||

| | publisher = No Starch Press | |||

| | year = 2010 | |||

| | page = 388 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-59327-220-3 | |||

| | quote = Among the types of events that cause the kernel to generate a signal for a process are the following: A software event occurred. For example, ... the process's CPU time limit was exceeded | |||

| }}</ref> A ] may set a timer to go off after a few seconds in case too much data causes an algorithm to take too long.<ref name="lpi-ch20-p388">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Kerrisk | |||

| | first = Michael | |||

| | title = The Linux Programming Interface | |||

| | publisher = No Starch Press | |||

| | year = 2010 | |||

| | page = 388 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-59327-220-3 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Software interrupts may be error conditions, such as a malformed ].<ref name="lpi-ch20-p388"/> However, the most common error conditions are ] and ].<ref name="lpi-ch20-p388"/> | |||

| Many operating systems allow the user to install or create any user interface they desire. The ] in conjunction with ] or ] is a commonly found setup on most Unix and Unix derivative (BSD, Linux, ]) systems. | |||

| ] can send messages to the kernel to modify the behavior of a currently running process.<ref name="lpi-ch20-p388"/> For example, in the ], pressing the ''interrupt character'' (usually ]) might terminate the currently running process.<ref name="lpi-ch20-p388"/> | |||

| GUIs tend to change with time. For example, Windows has modified its GUI every time a new major version of Windows is released and the Mac OS GUI changed dramatically with the introduction of Mac OS X. | |||

| To generate ''software interrupts'' for ] CPUs, the ] ] instruction is available.<ref name="intel-developer">{{cite web | |||

| ===Device drivers=== | |||

| |url=https://www.intel.com/content/dam/www/public/us/en/documents/manuals/64-ia-32-architectures-software-developer-instruction-set-reference-manual-325383.pdf | |||

| A ] is a specific type of computer software developed to allow interaction with hardware devices. Typically this constitutes an interface for communicating with the device, through the specific computer bus or communications subsystem that the hardware is connected to, providing commands to and/or receiving data from the device, and on the other end, the requisite interfaces to the operating system and software applications. It is a specialized hardware dependent computer program which is also operating system specific that enables another program, typically an operating system or applications software package or computer program running under the operating system kernel, to interact transparently with a hardware device, and usually provides the requisite interrupt handling necessary for any necessary asynchronous time-dependent hardware interfacing needs. | |||

| |access-date=2022-05-05 | |||

| |title=Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual | |||

| |volume=2 | |||

| |date=September 2016 | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |page=610 | |||

| |archive-date=23 March 2022 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220323231921/https://www.intel.com/content/dam/www/public/us/en/documents/manuals/64-ia-32-architectures-software-developer-instruction-set-reference-manual-325383.pdf | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> The syntax is <code>INT X</code>, where <code>X</code> is the offset number (in ] format) to the ]. | |||

| =====Signal===== | |||

| The key design goal of device drivers is abstraction. Every model of hardware (even within the same class of device) is different. Newer models also are released by manufacturers that provide more reliable or better performance and these newer models are often controlled differently. Computers and their operating systems cannot be expected to know how to control every device, both now and in the future. To solve this problem, OSes essentially dictate how every type of device should be controlled. The function of the device driver is then to translate these OS mandated function calls into device specific calls. In theory a new device, which is controlled in a new manner, should function correctly if a suitable driver is available. This new driver will ensure that the device appears to operate as usual from the operating systems' point of view. | |||

| To generate ''software interrupts'' in ] operating systems, the <code>kill(pid,signum)</code> ] will send a ] to another process.<ref name="duos-p200">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Bach | |||

| | first = Maurice J. | |||

| | title = The Design of the UNIX Operating System | |||

| | publisher = Prentice-Hall | |||

| | year = 1986 | |||

| | page = 200 | |||

| | isbn = 0-13-201799-7 | |||

| }}</ref> <code>pid</code> is the ] of the receiving process. <code>signum</code> is the signal number (in ] format){{efn|Examples include ], ], and ].}} to be sent. (The abrasive name of <code>kill</code> was chosen because early implementations only terminated the process.)<ref name="lpi-ch20-p400">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Kerrisk | |||

| | first = Michael | |||

| | title = The Linux Programming Interface | |||

| | publisher = No Starch Press | |||

| | year = 2010 | |||

| | page = 400 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1-59327-220-3 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| In Unix-like operating systems, ''signals'' inform processes of the occurrence of asynchronous events.<ref name="duos-p200"/> To communicate asynchronously, interrupts are required.<ref name="sco-ch5-p308_b">{{cite book | |||

| ==History== | |||

| | last = Tanenbaum | |||

| {{main|History of operating systems}} | |||

| | first = Andrew S. | |||

| | title = Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition | |||

| | publisher = Prentice Hall | |||

| | year = 1990 | |||

| | page = | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-13-854662-5 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/structuredcomput00tane/page/308 | |||

| }}</ref> One reason a process needs to asynchronously communicate to another process solves a variation of the classic ].<ref name="osc-p182">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Silberschatz | |||

| | first = Abraham | |||

| | title = Operating System Concepts, Fourth Edition | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | page = 182 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-201-50480-4 | |||

| }}</ref> The writer receives a pipe from the ] for its output to be sent to the reader's input stream.<ref name="usp-ch6-p153">{{cite book | |||

| | last1 = Haviland | |||

| | first1 = Keith | |||

| | last2 = Salama | |||

| | first2 = Ben | |||

| | title = UNIX System Programming | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley Publishing Company | |||

| | year = 1987 | |||

| | page = 153 | |||

| | isbn = 0-201-12919-1 | |||

| }}</ref> The ] syntax is <code>alpha | bravo</code>. <code>alpha</code> will write to the pipe when its computation is ready and then sleep in the wait queue.<ref name="usp-ch6-p148">{{cite book | |||

| | last1 = Haviland | |||

| | first1 = Keith | |||

| | last2 = Salama | |||

| | first2 = Ben | |||

| | title = UNIX System Programming | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley Publishing Company | |||

| | year = 1987 | |||

| | page = 148 | |||

| | isbn = 0-201-12919-1 | |||

| }}</ref> <code>bravo</code> will then be moved to the ] and soon will read from its input stream.<ref name="usp-ch6-p149">{{cite book | |||

| | last1 = Haviland | |||

| | first1 = Keith | |||

| | last2 = Salama | |||

| | first2 = Ben | |||

| | title = UNIX System Programming | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley Publishing Company | |||

| | year = 1987 | |||

| | page = 149 | |||

| | isbn = 0-201-12919-1 | |||

| }}</ref> The kernel will generate ''software interrupts'' to coordinate the piping.<ref name="usp-ch6-p149"/> | |||

| ''Signals'' may be classified into 7 categories.<ref name="duos-p200"/> The categories are: | |||

| # when a process finishes normally. | |||

| # when a process has an error exception. | |||

| # when a process runs out of a system resource. | |||

| # when a process executes an illegal instruction. | |||

| # when a process sets an alarm event. | |||

| # when a process is aborted from the keyboard. | |||

| # when a process has a tracing alert for debugging. | |||

| =====Hardware interrupt===== | |||

| ] (I/O) ] are slower than the CPU. Therefore, it would slow down the computer if the CPU had to ] for each I/O to finish. Instead, a computer may implement interrupts for I/O completion, avoiding the need for ] or busy waiting.<ref name="sco-ch5-p292">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Tanenbaum | |||

| | first = Andrew S. | |||

| | title = Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition | |||

| | publisher = Prentice Hall | |||

| | year = 1990 | |||

| | page = | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-13-854662-5 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/structuredcomput00tane/page/292 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Some computers require an interrupt for each character or word, costing a significant amount of CPU time. ] (DMA) is an architecture feature to allow devices to bypass the CPU and access ] directly.<ref name=A22-6821-7-storage>{{cite book | |||

| |author = IBM | |||

| |title = IBM System/360 Principles of Operation | |||

| |date = September 1968 | |||

| |version = Eighth Edition | |||

| |url = http://bitsavers.org/pdf/ibm/360/princOps/A22-6821-7_360PrincOpsDec67.pdf | |||

| |section = Main Storage | |||

| |section-url = http://bitsavers.org/pdf/ibm/360/princOps/A22-6821-7_360PrincOpsDec67.pdf#page=8 | |||

| |mode = cs2 | |||

| |page = 7 | |||

| |access-date = 13 April 2022 | |||

| |archive-date = 19 March 2022 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220319083255/http://bitsavers.org/pdf/ibm/360/princOps/A22-6821-7_360PrincOpsDec67.pdf | |||

| |url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> (Separate from the architecture, a device may perform direct memory access{{efn|often in the form of a DMA chip for smaller systems and I/O channels for larger systems}} to and from main memory either directly or via a bus.)<ref name="sco-ch5-p294"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Tanenbaum | |||

| | first = Andrew S. | |||

| | title = Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition | |||

| | publisher = Prentice Hall | |||

| | year = 1990 | |||

| | page = | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-13-854662-5 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/structuredcomput00tane/page/294 | |||

| }}</ref>{{efn|Modern ]s have a DMA controller. Additionally, a device may also have one. Visit ].}} | |||

| ====Input/output==== | |||

| =====Interrupt-driven I/O===== | |||

| {{Expand section|date=April 2022}} | |||

| When a ] types a key on the keyboard, typically the character appears immediately on the screen. Likewise, when a user moves a ], the ] immediately moves across the screen. Each keystroke and mouse movement generates an ''interrupt'' called ''Interrupt-driven I/O''. An interrupt-driven I/O occurs when a process causes an interrupt for every character<ref name="sco-ch5-p294"/> or word<ref>{{cite book | |||

| |title = Users Handbook - PDP-7 | |||

| |id = F-75 | |||

| |year = 1965 | |||

| |url = http://bitsavers.org/pdf/dec/pdp7/F-75_PDP-7userHbk_Jun65.pdf | |||

| |section = Program Interrupt Controller (PIC) | |||

| |section-url = http://bitsavers.org/pdf/dec/pdp7/F-75_PDP-7userHbk_Jun65.pdf#page=62 | |||

| |pages = | |||

| |publisher = ] | |||

| |access-date = April 20, 2022 | |||

| |archive-date = 10 May 2022 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220510164742/http://bitsavers.org/pdf/dec/pdp7/F-75_PDP-7userHbk_Jun65.pdf | |||

| |url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> transmitted. | |||

| =====Direct memory access===== | |||

| Devices such as ]s, ]s, and ] drives can transfer data at a rate high enough that interrupting the CPU for every byte or word transferred, and having the CPU transfer the byte or word between the device and memory, would require too much CPU time. Data is, instead, transferred between the device and memory independently of the CPU by hardware such as a ] or a ] controller; an interrupt is delivered only when all the data is transferred.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://bitsavers.org/pdf/dec/pdp1/F25_PDP1_IO.pdf|title=PDP-1 Input-Output Systems Manual|publisher=]|pages=19–20|access-date=16 August 2022|archive-date=25 January 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190125050839/http://bitsavers.org/pdf/dec/pdp1/F25_PDP1_IO.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| If a ] executes a ] to perform a block I/O ''write'' operation, then the system call might execute the following instructions: | |||

| * Set the contents of the CPU's ] (including the ]) into the ].<ref name="osc-ch2-p32_b">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Silberschatz | |||

| | first = Abraham | |||

| | title = Operating System Concepts, Fourth Edition | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | page = 32 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-201-50480-4 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| * Create an entry in the device-status table.<ref name="osc-ch2-p34">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Silberschatz | |||

| | first = Abraham | |||

| | title = Operating System Concepts, Fourth Edition | |||

| | publisher = Addison-Wesley | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | page = 34 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-201-50480-4 | |||

| }}</ref> The operating system maintains this table to keep track of which processes are waiting for which devices. One field in the table is the ] of the process control block. | |||

| * Place all the characters to be sent to the device into a ].<ref name="sco-ch5-p308_b"/> | |||

| * Set the memory address of the memory buffer to a predetermined device register.<ref name="sco-ch5-p295">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Tanenbaum | |||

| | first = Andrew S. | |||

| | title = Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition | |||

| | publisher = Prentice Hall | |||

| | year = 1990 | |||

| | page = | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-13-854662-5 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/structuredcomput00tane/page/295 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| * Set the buffer size (an integer) to another predetermined register.<ref name="sco-ch5-p295"/> | |||

| * Execute the ] to begin the writing. | |||

| * Perform a ] to the next process in the ]. | |||

| While the writing takes place, the operating system will context switch to other processes as normal. When the device finishes writing, the device will ''interrupt'' the currently running process by ''asserting'' an ]. The device will also place an integer onto the data bus.<ref name="sco-ch5-p309">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Tanenbaum | |||

| | first = Andrew S. | |||

| | title = Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition | |||

| | publisher = Prentice Hall | |||

| | year = 1990 | |||

| | page = | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-13-854662-5 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/structuredcomput00tane/page/309 | |||

| }}</ref> Upon accepting the interrupt request, the operating system will: | |||

| * Push the contents of the ] (a register) followed by the ] onto the ].<ref name="osc-ch2-p31"/> | |||

| * Push the contents of the other registers onto the call stack. (Alternatively, the contents of the registers may be placed in a system table.)<ref name="sco-ch5-p309"/> | |||

| * Read the integer from the data bus. The integer is an offset to the ]. The vector table's instructions will then: | |||

| :* Access the device-status table. | |||

| :* Extract the process control block. | |||

| :* Perform a context switch back to the writing process. | |||

| When the writing process has its ] expired, the operating system will:<ref name="sco-ch5-p310">{{cite book | |||

| | last = Tanenbaum | |||

| | first = Andrew S. | |||

| | title = Structured Computer Organization, Third Edition | |||

| | publisher = Prentice Hall | |||

| | year = 1990 | |||

| | page = | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-13-854662-5 | |||

| | url = https://archive.org/details/structuredcomput00tane/page/310 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| * Pop from the call stack the registers other than the status register and program counter. | |||

| * Pop from the call stack the status register. | |||

| * Pop from the call stack the address of the next instruction, and set it back into the program counter. | |||

| With the program counter now reset, the interrupted process will resume its time slice.<ref name="osc-ch2-p31"/> | |||

| ====Memory management==== | |||

| {{Main|Memory management}} | |||

| Among other things, a multiprogramming operating system ] must be responsible for managing all system memory which is currently in use by the programs. This ensures that a program does not interfere with memory already in use by another program. Since programs time share, each program must have independent access to memory. | |||

| Cooperative memory management, used by many early operating systems, assumes that all programs make voluntary use of the ]'s memory manager, and do not exceed their allocated memory. This system of memory management is almost never seen any more, since programs often contain bugs which can cause them to exceed their allocated memory. If a program fails, it may cause memory used by one or more other programs to be affected or overwritten. Malicious programs or viruses may purposefully alter another program's memory, or may affect the operation of the operating system itself. With cooperative memory management, it takes only one misbehaved program to crash the system. | |||

| ] enables the ] to limit a process' access to the computer's memory. Various methods of memory protection exist, including ] and ]. All methods require some level of hardware support (such as the ] MMU), which does not exist in all computers. | |||

| In both segmentation and paging, certain ] registers specify to the CPU what memory address it should allow a running program to access. Attempts to access other addresses trigger an interrupt, which causes the CPU to re-enter ], placing the ] in charge. This is called a ] or Seg-V for short, and since it is both difficult to assign a meaningful result to such an operation, and because it is usually a sign of a misbehaving program, the ] generally resorts to terminating the offending program, and reports the error. | |||

| Windows versions 3.1 through ME had some level of memory protection, but programs could easily circumvent the need to use it. A ] would be produced, indicating a segmentation violation had occurred; however, the system would often crash anyway. | |||

| ====Virtual memory==== | |||

| {{Main|Virtual memory}} | |||

| {{Further|Page fault}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The use of virtual memory addressing (such as paging or segmentation) means that the kernel can choose what memory each program may use at any given time, allowing the operating system to use the same memory locations for multiple tasks. | |||

| If a program tries to access memory that is not accessible{{efn|There are several reasons that the memory might be inaccessible | |||

| * The address might be out of range | |||

| * The address might refer to a page or segment that has been moved to a backing store | |||

| * The address might refer to memory that has restricted access due to, e.g., ], ].}} memory, but nonetheless has been allocated to it, the kernel is interrupted {{See above|{{Section link||Memory management}}}}. This kind of interrupt is typically a ]. | |||

| When the kernel detects a page fault it generally adjusts the virtual memory range of the program which triggered it, granting it access to the memory requested. This gives the kernel discretionary power over where a particular application's memory is stored, or even whether or not it has been allocated yet. | |||

| In modern operating systems, memory which is accessed less frequently can be temporarily stored on a disk or other media to make that space available for use by other programs. This is called ], as an area of memory can be used by multiple programs, and what that memory area contains can be swapped or exchanged on demand. | |||

| Virtual memory provides the programmer or the user with the perception that there is a much larger amount of RAM in the computer than is really there.<ref name="Operating System">{{cite book|last=Stallings|first=William|title=Computer Organization & Architecture|year=2008|publisher=Prentice-Hall of India Private Limited|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-81-203-2962-1|page=267}}</ref> | |||

| ===Concurrency=== | |||

| {{see also|Computer multitasking|Process management (computing)}} | |||

| ] refers to the operating system's ability to carry out multiple tasks simultaneously.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=129}} Virtually all modern operating systems support concurrency.{{sfn|Silberschatz et al.|2018|p=159}} | |||

| ]s enable splitting a process' work into multiple parts that can run simultaneously.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=130}} The number of threads is not limited by the number of processors available. If there are more threads than processors, the operating system ] schedules, suspends, and resumes threads, controlling when each thread runs and how much CPU time it receives.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=131}} During a ] a running thread is suspended, its state is saved into the ] and stack, and the state of the new thread is loaded in.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=157, 159}} Historically, on many systems a thread could run until it relinquished control (]). Because this model can allow a single thread to monopolize the processor, most operating systems now can ] a thread (]).{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=139}} | |||

| Threads have their own thread ID, ] (PC), a ] set, and a ], but share code, ] data, and other resources with other threads of the same process.{{sfn|Silberschatz et al.|2018|p=160}}{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=183}} Thus, there is less overhead to create a thread than a new process.{{sfn|Silberschatz et al.|2018|p=162}} On single-CPU systems, concurrency is switching between processes. Many computers have multiple CPUs.{{sfn|Silberschatz et al.|2018|pp=162–163}} ] with multiple threads running on different CPUs can speed up a program, depending on how much of it can be executed concurrently.{{sfn|Silberschatz et al.|2018|p=164}} | |||

| ===File system=== | |||

| {{Main|File system}} | |||

| {{see also|Virtual file system}} | |||

| ]s allow users and programs to organize and sort files on a computer, often through the use of ] (or folders).]] | |||

| Permanent storage devices used in twenty-first century computers, unlike ] ] (DRAM), are still accessible after a ] or ]. Permanent (]) storage is much cheaper per byte, but takes several orders of magnitude longer to access, read, and write.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=492, 517}}{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=259–260}} The two main technologies are a ] consisting of ]s, and ] (a ] that stores data in electrical circuits). The latter is more expensive but faster and more durable.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=517, 530}}{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=260}} | |||

| ]s are an ] used by the operating system to simplify access to permanent storage. They provide human-readable ] and other ], increase performance via ] of accesses, prevent multiple threads from accessing the same section of memory, and include ] to identify ].{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=492–493}} File systems are composed of files (named collections of data, of an arbitrary size) and ] (also called folders) that list human-readable filenames and other directories.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=496}} An absolute ] begins at the ] and lists ] divided by punctuation, while a relative path defines the location of a file from a directory.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=496–497}}{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=274–275}} | |||

| ]s (which are sometimes ] by libraries) enable applications to create, delete, open, and close files, as well as link, read, and write to them. All these operations are carried out by the operating system on behalf of the application.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=502–504}} The operating system's efforts to reduce latency include storing recently requested blocks of memory in a ] and ] data that the application has not asked for, but might need next.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=507}} ]s are software specific to each ] (I/O) device that enables the operating system to work without modification over different hardware.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=508}}{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=359}} | |||

| Another component of file systems is a ] that maps a file's name and metadata to the ] where its contents are stored.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=545}} Most file systems use directories to convert file names to file numbers. To find the block number, the operating system uses an ] (often implemented as a ]).{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=546}} Separately, there is a free space ] to track free blocks, commonly implemented as a ].{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=546}} Although any free block can be used to store a new file, many operating systems try to group together files in the same directory to maximize performance, or periodically reorganize files to reduce ].{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=547}} | |||

| Maintaining data reliability in the face of a computer crash or hardware failure is another concern.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=589, 591}} File writing protocols are designed with atomic operations so as not to leave permanent storage in a partially written, inconsistent state in the event of a crash at any point during writing.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|pp=591–592}} Data corruption is addressed by redundant storage (for example, RAID—]){{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=385–386}}{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=592}} and ] to detect when data has been corrupted. With multiple layers of checksums and backups of a file, a system can recover from multiple hardware failures. Background processes are often used to detect and recover from data corruption.{{sfn|Anderson|Dahlin|2014|p=592}} | |||

| ===Security=== | |||

| {{Main|Computer security}} | |||

| Security means protecting users from other users of the same computer, as well as from those who seeking remote access to it over a network.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=605-606}} <!-- A ] is when a bug can be exploited to compromise the system or its data; an ] is the signal needed to trigger the bug causing the vulnerability.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=606}} Often the goal of the attacker is to install ], whether in the form of a ], ], or ].{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=607}} --> Operating systems security rests on achieving the ]: confidentiality (unauthorized users cannot access data), integrity (unauthorized users cannot modify data), and availability (ensuring that the system remains available to authorized users, even in the event of a ]).{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=608}} As with other computer systems, isolating ]s—in the case of operating systems, the kernel, processes, and ]s—is key to achieving security.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=609}} Other ways to increase security include simplicity to minimize the ], locking access to resources by default, checking all requests for authorization, ] (granting the minimum privilege essential for performing a task), ], and reducing shared data.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=609–610}} | |||

| Some operating system designs are more secure than others. Those with no isolation between the kernel and applications are least secure, while those with a ] like most general-purpose operating systems are still vulnerable if any part of the kernel is compromised. A more secure design features ]s that separate the kernel's privileges into many separate security domains and reduce the consequences of a single kernel breach.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=612}} ]s are another approach that improves security by minimizing the kernel and separating out other operating systems functionality by application.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=612}} | |||

| Most operating systems are written in ] or ], which create potential vulnerabilities for exploitation. Despite attempts to protect against them, vulnerabilities are caused by ] attacks, which are enabled by the lack of ].{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=648, 657}} <!-- Other types of vulnerability in operating systems written in C and C++ include ]s, which exploit lack of ] to ],{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=658, 661}} ]s that rely on ],{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=661}} and ]s that an attacker can exploit to crash a computer.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=664}} --> Hardware vulnerabilities, some of them ], can also be used to compromise the operating system.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=668–669, 674}} There are known instances of operating system programmers deliberately implanting vulnerabilities, such as ]s.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=679–680}} | |||

| Operating systems security is hampered by their increasing complexity and the resulting inevitability of bugs.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=605, 617–618}} Because ] of operating systems may not be feasible, developers use operating system ] to reduce vulnerabilities,{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=681–682}} e.g. ], ],{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=683}} ]s,{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=685}} and other techniques.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=689}} There are no restrictions on who can contribute code to open source operating systems; such operating systems have transparent change histories and distributed governance structures.{{sfn|Richet|Bouaynaya|2023|p=92}} Open source developers strive to work collaboratively to find and eliminate security vulnerabilities, using ] and ] to expunge malicious code.{{sfn|Richet|Bouaynaya|2023|pp=92–93}}{{sfn|Berntsso|Strandén|Warg|2017|pp=130–131}} ] advises releasing the ] of all operating systems, arguing that it prevents developers from placing trust in secrecy and thus relying on the unreliable practice of ].{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=611}} | |||

| ===User interface=== | |||

| {{Main|Shell (computing){{!}}Operating system user interface}} | |||

| A ] (UI) is essential to support human interaction with a computer. The two most common user interface types for any computer are | |||

| *], where computer commands are typed, line-by-line, | |||

| *] (GUI) using a visual environment, most commonly a combination of the window, icon, menu, and pointer elements, also known as ]. | |||

| For personal computers, including ]s and ]s, and for ]s, user input is typically from a combination of ], ], and ] or ], all of which are connected to the operating system with specialized software.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=396, 402}} Personal computer users who are not software developers or coders often prefer GUIs for both input and output; GUIs are supported by most personal computers.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|pp=395, 408}} The software to support GUIs is more complex than a command line for input and plain text output. Plain text output is often preferred by programmers, and is easy to support.{{sfn|Tanenbaum|Bos|2023|p=402}} | |||

| The first computers did not have operating systems. However, software tools for managing the system and simplifying the use of hardware appeared very quickly afterwards, and gradually expanded in scope. By the early 1960s, commercial computer vendors were supplying quite extensive tools for streamlining the development, scheduling, and execution of jobs on ] systems. Examples were produced by ] and ], amongst others. | |||

| ==Operating system development as a hobby== | |||

| Through the 1960s, several major concepts were developed, driving the development of operating systems. The development of the ] ] produced a family of ]s available in widely differing capacities and price points, for which a single operating system ] was planned (rather than developing ad-hoc programs for every individual model). This concept of a single OS spanning an entire product line was crucial for the success of System/360 and, in fact, IBM's current mainframe operating systems are distant descendants of this original system; applications written for the OS/360 can still be run on modern machines. OS/360 also contained another important advance: the development of the ] permanent storage device (which IBM called ]). Another key development was the concept of ]: the idea of sharing the resources of expensive computers amongst multiple computer users interacting in real time with the system. Time sharing allowed all of the users to have the illusion of having exclusive access to the machine; the ] timesharing system was the most famous of a number of new operating systems developed to take advantage of the concept. | |||

| {{Main|Hobbyist operating system}} | |||

| A hobby operating system may be classified as one whose code has not been directly derived from an existing operating system, and has few users and active developers.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Holwerda |first1=Thom |title=My OS Is Less Hobby than Yours |url=https://www.osnews.com/story/22638/my-os-is-less-hobby-than-yours/ |website=OS News |access-date=4 June 2024 |date=20 December 2009}}</ref> | |||

| In some cases, hobby development is in support of a "]" computing device, for example, a simple ] powered by a ]. Or, development may be for an architecture already in widespread use. Operating system development may come from entirely new concepts, or may commence by modeling an existing operating system. In either case, the hobbyist is her/his own developer, or may interact with a small and sometimes unstructured group of individuals who have like interests. | |||

| Multics, particularly, was an inspiration to a number of operating systems developed in the 1970s, notably ]. Another commercially-popular ] operating system was ]. | |||

| Examples of hobby operating systems include ] and ]. | |||

| The first ]s did not have the capacity or need for the elaborate operating systems that had been developed for mainframes and minis; minimalistic operating systems were developed, often loaded from ] and known as ''Monitors''. One notable early disk-based operating system was ], which was supported on many early microcomputers and was largely cloned in creating ], which became wildly popular as the operating system chosen for the ] (IBM's version of it was called IBM-DOS or ]), its successors making ] one of the world's most profitable companies. The major alternative throughout the 1980s in the microcomputer market was ], tied intimately to the ] computer. | |||

| ==Diversity of operating systems and portability== | |||

| By the 1990s, the microcomputer had evolved to the point where, as well as extensive ] facilities, the robustness and flexibility of operating systems of larger computers became increasingly desirable. Microsoft's response to this change was the development of ], which served as the basis for Microsoft's entire operating system line starting in 1999. Apple rebuilt their operating system on top of a ] core as ], released in 2001. Hobbyist-developed reimplementations of Unix, assembled with the tools from the ], also became popular; versions based on the ] kernel are by far the most popular, with the ] derived UNIXes holding a small portion of the server market. | |||

| If an application is written for use on a specific operating system, and is ] to another OS, the functionality required by that application may be implemented differently by that OS (the names of functions, meaning of arguments, etc.) requiring the application to be adapted, changed, or otherwise ].<!--There really ought to be a discussion of ''software modules'' somewhere, such as those that are neither API's nor Plug-Ins (not sure what those are), but which are either hard (on cartridge), soft (on diskette), or otherwise installable by downloading). --> | |||

| This cost in supporting operating systems diversity can be avoided by instead writing applications against ]s such as ] or ]. These abstractions have already borne the cost of adaptation to specific operating systems and their ]. | |||

| The growing complexity of embedded devices has led to increasing use of ]. | |||

| Another approach is for operating system vendors to adopt standards. For example, ] and ] provide commonalities that reduce porting costs. | |||

| ==Today== | |||

| ] | |||